Abstract

The subject of this article is the centuries-old religious heritage of Vilnius. The aim of the article is to analyse this heritage and its reflection in the gaze of tourists. In particular, it focuses on selected Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, Jewish, and Karaite sites. The methods used in the empirical study include the analysis of reviews posted on the Tripadvisor website by tourists from different countries who visited five selected sites: (1) St. Anne’s Church, (2) Holy Spirit Orthodox Church, (3) Evangelical Lutheran Church, (4) Vilnius Choral Synagogue, and (5) Kenesa. The authors employed the method of desk research, which involves the analysis of existing data. The selection of objects was made by indicating the most commented sites of a given religious tradition for which the most comments were received. In the light of the pervasive influence of social media, it is noteworthy to observe the contemporary representation of multi-religious Vilnius that is disseminated through this medium. Urban sacred spaces are not only places of worship of interest to religious people, including local and foreign pilgrims. Furthermore, they constitute an attractive urban heritage for a significant number of cultural tourists. Committed tourists, including cultural tourists, meticulously document their impressions in various forms of narrative, offering either endorsement or criticism of a particular object. In this manner, they also interpret elements of the heritage in the local urban space.

1. Introduction

Contemporary travel has undergone significant transformations in comparison with the manner of travel undertaken for commercial or spiritual purposes in the past (Pencarelli et al. 2020). The diversity and multiplicity of individual motivations of modern man, the ease of travel associated with the development of low-cost airlines, the popularity of certain destinations, the promotion of certain regions, cities or sites, and finally, the travel narratives and micro-narratives of tourists, with the particular role of influencers in social media, form a synergy that shapes phenomena of global scale and impact. Consequently, the academic literature employs the terms cultural tourism or religious tourism. These terms are understood to denote mobility of a leisure, business nature, in which there are elements of contact of a cognitive nature with local heritage (Mikos von Rohrscheidt 2016a). The subject of analysis in this article is the contemporary city of Vilnius and its religious heritage as interpreted by tourists and, at the same time, users of the Tripadvisor portal. Modern social media platforms empower tourists to articulate their perspectives and experiences through the medium of micro-narratives and visual content. This phenomenon is regarded as a virtual tool that shapes and perpetuates the tourist gaze (Urry 2002), including that relating to religious heritage sites.

In the domain of cultural and religious tourism, Vilnius has been increasingly prominent for many years as a city with significant tourism potential (Vanagas and Jagminas 2011). The capital of Lithuania has been recognised for its potential, as evidenced by its selection as the European Green Capital 2025. This prestigious title is a testament to the city’s commitment to sustainability, characterized by its pragmatic and grounded approach to environmental issues. Vilnius’s motto for its European Green Capital title year is: «Vilnius—the greenest city in the making» (European Commission 2025). The Lithuanian capital of Vilnius has been selected as the European Christmas Capital for 2025. Furthermore, it has also been recognised by the Christmas Cities Network for its blend of “history, culture, and community engagement” (European Capital of Christmas 2025). As is evident, the city’s attributes are discernible during specific seasons. However, numerous arguments substantiate an autonomous, enduring heritage that has been shaped by representatives of diverse cultural groups over a period exceeding seven centuries in its history.

The panorama of the Old Town (Figure 1), which was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994, is characterised by a profusion of towers and domes that adorn religious buildings. These structures serve as tangible evidence of the historical presence of diverse religious, national, linguistic, and cultural groups within the urban landscape (Briedis 2009). The architecture and decoration of numerous religious edifices evince the pre-eminence of the Baroque style. Nevertheless, the site comprises a complex of Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, and Classical buildings, as well as its medieval layout and natural environment. Christian churches are predominant, including Catholicism (Kviklys 1985), yet Orthodox churches and places of worship are also in evidence, suggesting the presence and influence of Protestantism, including German craftsmen (Vaišvilaitė 2022). The modern Lithuanian capital, known as the ‘Jerusalem of the North’ (Lithuanian: Šiaurės Jeruzalė), has been an important centre of Jewish diaspora life for centuries. In this respect, the continuity of the city’s centuries-long presence and co-creation, which had lasted centuries, was interrupted by the Second World War and the Shoah (Zalkin 2025). It is estimated that more than 100 synagogues that operated in the city prior to the war were destroyed, with a mere one remaining (Woolfson 2013). The influence of the Karaite group is also worthy of note, as it brought to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania a significant body of knowledge This small group, which was predominantly located in Trakai, also exerted its influence in Vilnius (Harviainen 2003; Kobeckaitė 1993). The unique edifice, designated as the ‘keneisa, kenas, kineza, kanza’ or Karaite prayer house—serves to emphasize the city’s multi-religious and multicultural heritage (Kizilov 2015).

Figure 1.

Panoramic view of the Old Town of Vilnius from the Gediminas Hill. Source: Private archive: 24 May 2023.

Pilgrimages to the Gates of Dawn in Vilnius have been in existence for centuries. The city’s status as an important European sanctuary and pilgrimage centre is attributed to the long-standing tradition and the development of the Marian cult (Mroczek 2019; Jarkiewicz 2012; Vaičiūnas 2005). The cult of the Divine Mercy is equally dynamic in the field, having developed since the 1930s. As with many cults it has encountered doctrinal and international problems (cf. Stefanowicz 2017). The concept od Divine Mercy was further developed through the efforts of Sister Faustina Kowalska (1905–1938), who was canonised in 2000, and her mystical Diary: Divine Mercy in My Soul, translated into many languages, this cult is known all over the world, especially—but not only—among Catholics. Blessed Michał Sopoćko (1888–1975), known as the ‘Apostle of Mercy’, and John Paul II (1920–2005) are also significant figures in the promotion of this cult beyond the borders of modern Lithuania (Liutikas 2016). Vilnius, which is often referred to as the ‘City/Capital of Divine Mercy’ (Račiūnaitė-Paužuolienė 2022), also stands to benefit from this recognition.

2. Materials and Methods

In light of the seminal contributions within the domain of urban studies (Sayın 2024) and tourism studies (Zhang and Szabó 2024; Pencarelli 2020; Gajdošík and Orelová 2020; Gelter 2017; Kotler et al. 2017), this paper presents the findings of an analytical investigation of comments posted on the Tripadvisor platform pertaining to specific venues in Vilnius.

The opinion aggregator was launched in 2000, and, as its name suggests, it provides advice from individuals sharing their experiences of all types of travel, including leisure and business trip. The platform offers an interactive forum for the purposes of sharing reviews and ratings, to which both tourist and guides as well as other individuals employed within the travel industry, are permitted to contribute. It is evident that the subject in question has the capacity to encourage, discourage, or even issue a warning with regard to specific experiences. It is available in 28 languages. The website states that it “helps 463 million people every month make the most of every trip”. The Tripadvisor website and mobile application facilitate the browsing of a substantial volume of reviews and opinions on a wide range of establishments and attractions, including, but not limited to, accommodations, restaurants, attractions, airlines, and cruises. The database encompasses over 859 million reviews and opinions from users across the globe. Travellers use Tripadvisor for a variety of purposes, including the planning of trip and planning of trips and the comparison of prices for hotels, flights, and cruises; the purchase of tickets for popular tours and attractions; and the booking of tables at the best restaurants (Tripadvisor 2025). Users submit reviews of tourist attractions, specific destinations, and heritage sites.

A special ‘Travelers’ Choice’ award is given to accommodations, attractions, and restaurants that “consistently receive great reviews from travellers and are in the top 10% of Tripadvisor sites” (Tripadvisor 2025). All these facts mean that the comments are also followed very closely by those in the travel industry (Tereszkiewicz 2018).

The study of social media dedicated to tourism is well-established in the literature (Leung et al. 2013). It has been demonstrated by numerous authors (Pollock 2014) that the global scale and power of its impact as a form of marketing, including the practice of whisper marketing (Uğurlu 2022; Gretzel 2018) has been thoroughly researched.

The utilization of quantitative analyses in the context of extensive databases facilitates the conceptualization of marketing and management solutions (Barbera et al. 2023; Minkwitz 2018; Lee 2016). The quality of services in the tourism sector is determined by the recommendations made by experts in the field. These recommendations are then used to maintain or improve the quality of services (Tereszkiewicz 2018; Ganzaroli et al. 2017; Neuhofer et al. 2015). In relation to Vilnius, this particular dimension of the utilization of technology for purposes specific to the tourism industry was emphasized by Ilona Beliatskaya (2017). In the contemporary era, technological facilities, including social media, have emerged as a valuable source of information, facilitating qualitative research initiatives that are centered on the shaping of the image of cultural heritage and the heritage itself, including religion (Piechocka 2021; Niezgoda 2017; Ganzaroli et al. 2017; Nowacki 2017).

The following research questions were proposed: (1) What kind of tourist experiences do tourists share in their comments about religious heritage in Vilnius? (2) What recommendations can be made with regard to religious heritage sites in Vilnius?

A total of 44 religious heritage sites in Vilnius that are of interest to tourists and recommended by users of the Tripadvisor platform have been identified. The websites have been categorized according to denomination in an Excel spreadsheet. The religious affiliations of the subjects are as follows: 32 were of the Catholic faith, 3 were of the Jewish faith, 6 were of the Orthodox faith, 2 were of the Protestant faith, and 1 was of the Karaite faith.

For the purposes of this analysis, five objects belonging to different religious traditions that have been present in Vilnius for centuries were selected (Figure 2). In the case of denominations with a greater number of historical objects, those with the highest number of comments were selected for further analysis. The verbal opinions are treated in the article as micro-narratives, formulated on the basis of personal, biographical travel experiences (cf. Pataca and de Oliveira 2016). The aforementioned platform facilitates the refinement of search criteria by allowing users to select travel categories, including solo, couple, friends, and business, as well as specifying the dates of stay, and the moment of expression. The filtering of comments by language provides insight into the multilingual and multinational composition of the user and tourist base of a given destination (in most cases, information on the country of residence is available alongside the authors’ nicknames). When expressed in terms of points ranging from 1 to 5, the average ratings are not a significant criterion for differentiating the sites in such a small group. The mean value of these measurements is approximately 5.0.

Figure 2.

Map of Vilnius with the analysed religious objects marked in yellow. Source: Own research based on https://www.google.com/maps (accessed on 10 May 2025).

Following the selection of five objects, we entered the data obtained from the Tripadvisor platform was entered into a bespoke Excel spreadsheet. The following information was obtained and included in the spreadsheet: the name of the heritage object; the language of the review; the date of the experience; the date the review was written; the author’s nickname; the author’s country of origin or residence; the purpose of the trip to Vilnius; the title of the review; the review text; and the opinion in points. The content of the comments was analysed using the following four categories: (1) religious value, (2) aesthetic admiration, (3) historical details, and (4) practical tourist information. These correspond to the four functions of religious heritage: cultic (sacred), aesthetic, cognitive, and consumer. The present assignment seeks to explore the multifarious reasons underlying the phenomenon of people visiting religious heritage sites. Armin Mikos von Rohrscheidt proposed a classification of tourists, distinguishing between those motivated by faith, those seeking experiences or a cognitive approach, and those engaging in various forms of cultural tourism, such as city tourism (Mikos von Rohrscheidt 2016b).

3. Religious Urban Heritage of Vilnius

The history of a city at the crossroads of civilisations, cultures and religions (see Kempa 2024; Pawluczuk 2015) is marked by wars, rivalries and external influences on the one hand, and by decisions that affect the identity of the city and its inhabitants on the other. The cultural heritage of Lithuania has been recognised as unique not only to the Lithuanian population and to minorities residing in the country and Vilnius, but also to the heritage of humanity. This is evidenced by more than seven hundred years of history. The following section will explore the symbolic meanings of the entries on the World Heritage List, on which the Old Town of Vilnius (Vilniaus senamiestis) has been listed since 1994. The urban area in question is the largest on the list, with an area of 352.09 ha and a buffer zone of 1912.24 ha. The formal recognition of the city’s uniqueness was determined by two criteria: “Criterion (II): Vilnius is an outstanding example of a medieval foundation which exercised a profound influence on architectural and cultural developments in a wide area of Eastern Europe over several centuries. Criterion (IV): In the townscape and the rich diversity of buildings that it preserves, Vilnius is an exceptional illustration of a Central European town which evolved organically over a period of five centuries” (UNESCO 2025).

The diversity of buildings is also related to religious objects that form sacred spaces (Liutikas 2023). This heritage attests to the multiculturalism and multi-religiousness of visitors and residents who came from diverse geographical regions, spoke numerous languages, and practised different religions (Pawluczuk 2015; Briedis 2009). As illustrated by the image of Vilnius, the concept of local hospitality and tolerance was of significant importance. This notion was shared by both the governors, that is to say the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, and the inhabitants, albeit with the caveat that this was not without controversy and conflict (see Kempa 2016).

3.1. St. Anne’s Church

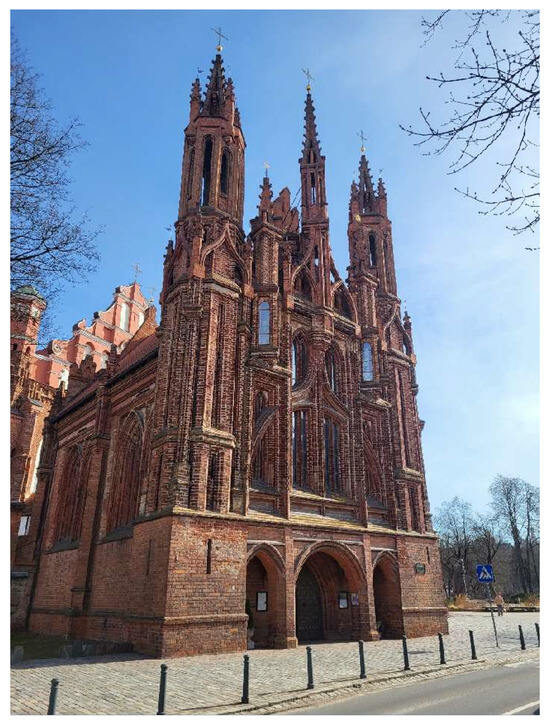

St. Anne’s Roman Catholic Church (Lithuanian: Vilniaus Šv. Onos bažnyčia), was constructed at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, and is situated at 8 Maironio Street near the Vileyka River1 (Figure 3). According to an urban legend, the church attracted Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821), who saw it while passing through Vilnius with his army on an expedition to Moscow. It is said that the emperor was so enchanted by the small temple, that he expressed his wish to have it transferred to France in his hand. The story was employed by the author of a publication on the subject of the church in the context of literary works, who placed it as an illustration on the title page (Mickiewicz 2011).

Figure 3.

St. Anne’s Church in Vilnius. Source: Private archive: 18 March 2023.

The church was founded by Aleksander Jagiellończyk (1461–1506), Grand Duke of Lithuania, and later King of Poland. Its architect was most likely Benedykt Rejt (c. 1454–1543), a native of Bohemia, with construction carried out by Michał Enkinger, who was Polish-German origin (Maroszek 1996). The church was rebuilt after a fire and consecrated in 1581. Subsequent alterations were undertaken in connection with the construction of three new altars in 1747 (Drema 1991). In 1812, the church was utilized as a military store for a period of several years. The bell tower, constructed in 1873 according to a design by the Russian architect Nikołaj Czagin (1823–1909), exemplifies an unsuccessful endeavor to align with the Gothic style of the building. The Gothic lace façade is decorated with 33 types of moulded brick. The church has a single nave and three neo-Gothic altars. The main altar is home to the miraculous image of St. Anne of Samothrace.

Following a fire in 1900–1904, the church underwent extensive renovations at the hands of Józef Pius Dziekoński (1844–1927) and Sławomir Odrzywolski (1846–1933). St. Anne’s was one of the few Catholic churches in the city that was not closed for worship during the Soviet era.

3.2. Holy Spirit Orthodox Church

The Orthodox Church of the Holy Spirit (Lithuanian: Vilniaus Šv. Dvasios cerkvė) is situated at 10 Aušros Vartų Street within the complex of buildings that constitute the Holy Spirit Monastery (Figure 4). The sisters Teodora and Anna Wołowicz are recognized as the founders of the first wooden church built on this site in 1597. The property was initially under the care of the Confraternity of the Holy Trinity2, which subsequently became known as the Confraternity of the Holy Spirit. In 1609, it was incorporated into the established monastery. In 1634, with the authorization of King Władysław IV Waza (1595–1648), a brick building was constructed. The reconstruction of the church, which was destroyed during the Swedish invasion at the beginning of the 18th century, was made possible thanks to the support of Tsar Peter I of Russia (1672–1725). Following the fires of the early 1750s, a reconstruction project was initiated under the direction of Jan Krzysztof Glaubitz (c. 1700–1767), a Vilnius-based architect of German origin and Lutheran faith. In 1812, during the course of Napoleon’s military campaign, his army looted the interior of the church as it passed through Vilnius. Several years later, the edifice was reconstructed, with one of the most significant augmentations being the installation of a gate at the entrance to the complex from Aušros Vartų Street. In 1870, the Russian governor of the city, General Michaił Murawjow (1796–1866), who was known by the sobriquet ‘Wieszatiel’, ordered another reconstruction of the church. The removal of Baroque elements, which bore a resemblance to the Catholic elements found in religious buildings, was a significant step in the process of transformation. The church underwent a program of restoration and renovation at the beginning of the 20th century, with works commencing in 1908.

Figure 4.

The Holy Spirit Orthodox Church in Vilnius. Source: Private archive: 9 May 2025.

The relics of the three Vilnius martyrs, Orthodox Saints Anthony, John, and Eustace, are enshrined in the church, which was established as their sanctuary in 1850 (Chomik 2011). The Orthodox feast day of the patron saints of Lithuania is celebrated on 27 April. In 1915, the relics of the martyrs were taken to Moscow with the evacuated Russian population, from where they returned in 1946 (Rusnak 2015). Subsequent to the restoration of the church, which was undertaken following the ravages of war, the relics have been enshrined beneath the canopy positioned before the iconostas (Szlewis 2006).

3.3. Evangelical Lutheran Church

The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Vilnius (Lithuanian: Vilniaus evangelikų liuteronų bažnyčia) is located in a rather unusual position at the rear of the site, due to alterations having been made to the original edifice and thoroughfare (18/20 Vokiečių Street). The edifice in question was constructed in 1555, and its provenance can be traced back to the Lithuanian Protestants. It is understood that the structure was originally established as a site for congregational meetings in Vilnius. The wooden church was founded by the Voivode of Vilnius, Mikołaj Radziwiłł (1515–1565). In 1655, edifice was consumed by fire during the Moscow invasion. The brick church was constructed in 1662. Damaged by several minor conflagrations, the structure was reconstructed between 1739 and 1744 by the aforementioned architect Jan Krzysztof Glaubitz in the Vilnius Baroque style. The architectural composition of the church comprises a single-nave church with a prominent four-storey tower, and is further distinguished by the presence of a rococo altar (Figure 5). In 1872, the church was further enhanced with the addition of a bell tower, complete with a spire and a weather vane. The furnishings have not survived; this is because, following the Second World War, the Soviet authorities converted the church into a sports hall for ball games. The building’s decoration and religious functions were restored only in the 1990s (Laukaitytė 2012; Petkūnas 2011). In the contemporary era, one of the Sunday services is of an ecumenical nature and is conducted in English.

Figure 5.

The interior of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Vilnius. Source: Private archive: 23 April 2022.

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in the modern city is a symbol of the time of the Reformation when confessional disputes were also a feature of life in Vilnius (Kempa 2016).

3.4. The Choral Synagogue of Vilnius

As evidenced by Pažėraitė (2013), the rich centuries-old Jewish heritage in Vilnius was demonstrated by the presence of more than a hundred synagogues operating in the city at the turn of the 20th century. The dynamic activities of numerous prominent representatives of religious and intellectual movements, including Elijah ben Salomon Zalman (1720–1797) (Stern 2013), led to the city being designated the ‘Jerusalem of the North’. Such an association is still in evidence in literary texts (Lenart 2014) and cultural and social initiatives (Litvak World 2025).

Today, the only authentic building remaining is the Choral Synagogue (Lithuanian: Vilniaus choralinė sinagoga; 9 Pylimo Street), built in 1903 in the Moorish style (Figure 6). The Targarot-Ha-kodash (Purification of the Temple), as it was known (Kłos 1923; Krajewski 2013), was associated with a group of Haskalah followers who had been active since 1846 and lacked a place of their own. In 1899, the Progressives procured a plot of land and constructed a building, the design of which was conceived by the architect David Rozenhaus (1875–1941). Tragically, Rozenhaus was murdered in Ponary. In 1941, the Germans closed the site and utilized it for the storage of narcotics. The Shoah in the Lithuanian lands and in Vilnius itself had catastrophic consequences. The extermination of the Lithuanian Jewish population also entailed the decimation of the millennia-old cultural and religious heritage of this minority group in Vilnius and other regions (Sandri 2013; Woolfson 2013).

Figure 6.

The Choral Synagogue of Vilnius. Source: Private archive: 27 May 2019.

During the Soviet era, the edifice was appropriated by the authorities and converted into a metal factory. In 1989, the building was converted to a modest local Jewish community. The synagogue was renovated with foreign funds at the beginning of the 20th century (WMF 2025).

Inside the building, there are galleries for women and the choir. The dome of the synagogue is a prominent feature of the skyline. The pediment is decorated with rosettes and crowned with a representation of the Tables of the Law of Moses.

3.5. Kenesa in Vilnius

The building of a small Karaite group, the kenesa (Lithuanian: Vilniaus kenesa), is the only one of the analysed buildings located outside the Old Town, at 9 Liubarto Street in the Žvėrynas district (Figure 7). The brick Kenesa was constructed between 1913 and 1922 for the religious needs of the Karaite community (Gąsiorowski 2018; Wróblewska 2015). Its designer was the Russian architect Michaił Prozorow (1860– after 1914). Construction was interrupted during the First World War. It was consecrated on 9 September 1923 by the head of the Hazzan community, Feliks Malecki (1854–1928). Closed by the authorities for half a century (1949–1989), the building remained unused. The small Karaite community, having regained a place of worship in the capital, inaugurated services on 9 March 1989 under the leadership of its leader, Michał Firkowicz (1924–2000).

Figure 7.

The Vilnius Kenesa. Source: Private archive: 18 March 2023.

The architectural design of kenesa is characterized by a rectangular plan, executed in the Moorish style, with a dome adorning the façade. Internally, the structure it is divided into three distinct sections: the primary, substantial prayer chamber reserved for men congregants, a balcony designated for female worshippers, and an antechamber. The echal, a cabinet used for the storage of the Torah scrolls, is located on the south wall.

During the Soviet period, there was widespread destruction and theft of furnishings and equipment. This included the gilded cypress altar, Persian carpets, antimony, altar curtains, altar candlesticks, chandeliers, and wooden benches. The existing furnishings have undergone a process of restoration. A case in point is the candlesticks, which were donated by the Karaite community in Halych.

4. Results

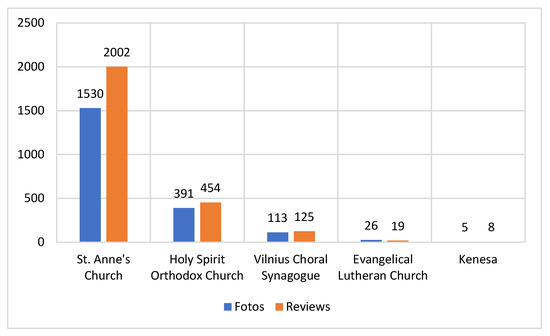

The data analysed comprised comments on the Tripadvisor platform concerning selected religious heritage sites, which were published by users of this platform between 2011 and 2024. The most recent commentary was published on 15 April 2024, whereas the earliest available commentary was dated 9 December 2011. The opinions expressed by Tripadvisor users on the selected religious heritage sites demonstrate considerable variation in both quantity and quality. As demonstrated in Figure 8, quantity is shown to vary from brief to extensive statements, with regard to quality. Nevertheless, the comments indicate a considerable degree of interest in Vilnius’ religious heritage among tourists from a variety of countries. It is noteworthy that a number of authors recommend a religious site without reference to their own religious affiliation. The potential for drawing conclusions on this matter is contingent upon the disclosure of religious beliefs by the authors of the opinions. It is recommended that future research be directed towards the analysis of comments in relation to the authors’ religious affiliation, as this would prove to be a fruitful avenue for further study. Nevertheless, the execution of the aforementioned study is rendered unfeasible due to the absence of pertinent data within the user profiles.

Figure 8.

The number of photos and reviews provided by Tripadvisor users. Source: Own research based on Tripadvisor.com.

It has been observed that users of the Tripadvisor platform frequently accompany their opinions with photographs of the objects in question, which are taken by the authors of the opinions themselves (Figure 8). The tourist gaze directed towards religious heritage is addressed in a separate article. However, the relatively elevated ranking of photographic images in comparison to the commentary text merits attention when considering selected sites: St. Anne’s Church 1.31; Holy Spirit Orthodox Church 1.16; Vilnius Choral Synagogue 1.11; Evangelical Lutheran Church 0.73; Kenesa 1.60.

In a limited number of instances, the authors provide a description of more than two of the analysed objects in a few cases. However, it is noteworthy that there are instances in which they return to a specific location to corroborate experiences in the context of transformation, such as the renovation of a building (see: Leena R—her/his opinions on TripAdvisor in 2018 and 2023).

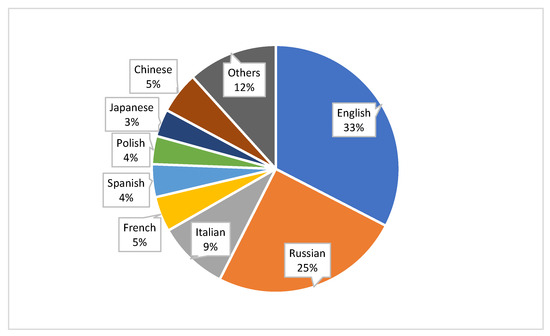

It is interesting to note the languages in which users expressed their opinions (Figure 9). Despite English being the most prevalent language (895 opinions), Russian is the second most common language (683 opinions). This phenomenon can be attributed to the geographical proximity of Russia and its familiarity with tourists from other countries, particularly those formerly under the influence of the Soviet Union. To a lesser extent, but still noticeable, are languages such as Italian (254), Chinese (1493), French (126), Spanish (118), Polish (101), and Japanese (98). The group of opinions in other languages (322) represents 12% of all opinions. The following languages are included in order of the number of opinions they have received. The following languages are represented: German (64), Portuguese (64), Dutch (58), Swedish (38), Norwegian (30), Danish (13), Korean (11), Finnish (11), Greek (10), Turkish (7), Czech (5), Hebrew (4), Serbian (3), Thai (2), Slovak (1), Hungarian (1), and Arabic (1). The linguistic diversity exhibited by the users of Vilnius is indicative of the city’s status as a popular tourist destination for visitors from diverse geographical backgrounds. The purpose of their visit to the city is to experience its cultural heritage, which includes a variety of religious artefacts.

Figure 9.

Quantitative distribution of the languages used to express opinions on the sites analysed. Source: Own research based on Tripadvisor.com.

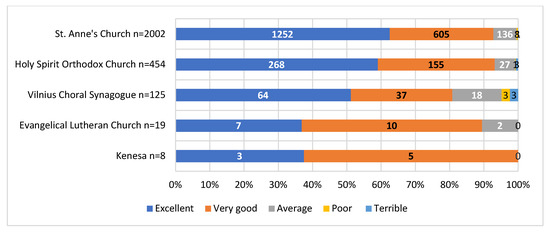

As outlined above, the utilization of a points based rating system facilitates the identification of establishments on the platform that have been distinguished with a ‘Travelers’ Choice’ award. The quantitative distribution of opinions on the objects selected for analysis is presented in points in the figure below. The scale ranges from 5 indicating “excellent”, to 1, indicating “terrible” (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Quantitative distribution of opinions on the religious objects chosen for analysis, expressed in points (from 5 to 1). Source: Own research based on Tripadvisor.com.

The opinions expressed byTripadvisor users regarding the selected religious heritage sites demonstrate significant variations in both quantity and quality. Nevertheless, it is evident that these monuments serve to illustrate the religious heritage of the city and the interest therein from tourists from a variety of international backgrounds. It is noteworthy that certain authors advocate for the analysis of these locations irrespective of their own religious or spiritual inclinations.

4.1. St. Anne’s Church in the Gaze of Tourists

In comparison to other ecclesiastical edifices and artefacts, St. Anne’s Church is regarded as a remarkable exemplar of its kind (gem, charming, the most beautiful) in Vilnius. It is held in high esteem for its aesthetic appeal and allure. It is noteworthy that the aforementioned individuals concur with the opinion and admiration expressed by the French emperor with regard to the legend of Napoleon. Furthermore, a visit to the interior of the Gothic church is recommended. It was evident that a number of individuals had been unable to visit the interior due to a variety of factors, including winter opening hours and group tours. These individuals subsequently expressed their discontent regarding this circumstance and expressed a desire to make a return visit. Given that the church is one of the few extant examples of Gothic architecture, many tourists compare it to the Baroque buildings that dominate the city. Additionally, they also make brief references to the surroundings and the proximity of other significant buildings, including the monument to the poet Adam Mickiewicz (1798–1855), who is identified with the city.

The most substantial number of comments, amounting to a total of 2002, pertained to this distinctive church in the Baroque city of Vilnius.

4.2. Holy Spirit Orthodox Church in the Gaze of Tourists

Expressions of a similarly, positive nature can also be found in the opinions of the Holy Spirit Orthodox Church. Nevertheless, the recollection of this locale is concomitant with observations pertaining to faculties other than sight. The olfactory experience of incense, the melodious singing of the choir, and the cantors during the liturgy are qualities that accompany a visit to this church. It is recommended that the church be entered at the conclusion of the service, at which point a candle may be purchased for lighting. The green iconostasis has attracted the attention of tourists, who often mention it when recommending a visit to the Shrine of the Vilnius Martyrs. Another distinctive characteristic of this church that is remembered by tourists is its towers, which deviate from the conventional Orthodox architectural style.

A total of 454 comments rating the Orthodox building were submitted by users of the platform.

4.3. Evangelical Lutheran Church in the Gaze of Tourists

The Evangelical Lutheran Church is recommended by users as a church to visit because of its relative simplicity when compared to the Baroque churches, which are renowned for their opulence. It is acknowledged by tourists that locating the site can be challenging, a difficulty that is regarded as “almost a real miracle”, given its presence on one of the primary thoroughfares in the historic district. It is noteworthy that a number of respondents expressed their delight at English-language liturgy and the w welcoming atmosphere created by members of the International Church of Vilnius community towards tourists. As posited by the authors, the allusion to the proximate Town Hall is intended to facilitate the location of the “hidden” object by the audience. Furthermore, they are able to recall details from the church’s surroundings, including the statue of Martin Luther, which is a non-obvious heritage feature in a city with a pre-dominantly Catholic denomination.

The previous objects of Christian heritage in Vilnius attracted a greater number of commentaries than the Lutheran church, which received only 19.

4.4. The Choral Synagogue of Vilnius

Tourists who have visited the Choral Synagogue recall the profound impression it has on them. The majority of commentators strongly advocate not only viewing the eexterior of the building but also entering the interior. Furthermore, many of them also express regret that, for various reasons, they have not been able to see the interior of the building. In addition to the synagogue, other Jewish sites in the ‘Jerusalem of the North’ are also mentioned, including museums (e.g., Vilna Gaon Museum of Jewish History; Lithuanian: Vilniaus Gaono žydų istorijos muziejus), the site of the former ghetto, the Holocaust, and Jewish heritage. To a certain extent, the authors of the commentaries can be regarded as ‘guardians of memory’, since they include references to the scale of the Shoah—the extermination of the Jews organised by the Germans and made possible by the participation of some members of local communities in the occupied territories of Lithuania. They also include references to the significant number of synagogues and the dynamism of the intellectual and cultural life of the Diaspora in the pre-war ‘City of Synagogues’.

A total of 125 comments have been made about the Choral Synagogue of Vilnius.

4.5. Kenesa in Vilnius in the Gaze of Tourists

A select group of Tripadvisor users, numbering only eight, advocate traversing the river, via the Liubarto Bridge, to encounter this ‘little gem’. The Karaite Kenesa is regarded as one of the select few distinctive prayer houses. A significant proportion of the details quoted by the authors of the commentaries demonstrate that they are privy to a considerable amount of interesting information regarding the history of the Karaite minority in Lithuania. For a considerable number of years, it has been impossible to enter the interior, most recently due to ongoing renovations, a fact that has not escaped the attention of tourists.

A cursory examination of the discourse surrounding the Karaite building in Vilnius reveals a paucity of commentary, with a mere eight comments having been posted thus far. This observation suggests that the subject has not garnered significant attention. The most probable reason for this is that the Kenesa is located outside the Old Town.

5. Conclusions

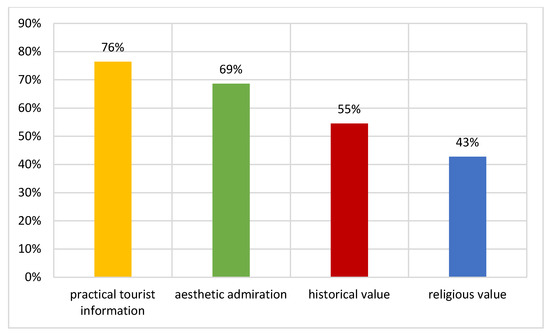

Notwithstanding the religious affiliation, of the participants, a content analysis of the tourist gaze on heritage sites revealed the emergence of four themes. The following four categories are to be considered: (1) religious value, (2) aesthetic admiration, (3) historical details, and (4) practical tourist information. In addition to their evident sacred function, the other functions of the described places are emphasised: aesthetic, cognitive, and consumer. As illustrated in Figure 11, the remarks were classified into these four analytical categories.

Figure 11.

Percentage distribution of mentions in reviews across four analytical categories. Source: Own research based on Tripadvisor.com.

5.1. Religious Value

The present category is applicable to comments that refer to specific religious functions of objects. For instance, the statement “It’s again functioning as a place of worship”4 [crosswycke], is a case in point, as is the statements as well as participation in services or rituals: “The choir that supported the Mass was incredible. Looking at the icons and listening to the choir was a truly stunning experience.” [anka_r11], “We were lucky enough to attend the Saturday service.” [Kaknastornet], “It is worth praying ecumenically and lighting a candle in front of one of the many altars. This invariably fosters a spirit of prayer” [131964].

This context also describes negative experiences: “When we arrived on Friday night, a few minutes before we were told to come, the woman at the gate actually shut the gate in our faces and said, ‘No tourists!’ We explained that we were Jewish and wanted to come to Shabbat services, but she didn’t speak English. She refused to open the gate. After several minutes of explaining—and with me finally pulling out the siddur5 that I had brought—she reluctantly let us in and opened the women’s section (on the balcony) for us. […] It is disappointing that a synagogue would be so unwelcoming to fellow Jews from around the world.” [djorangutan].

Information and opinions on religious worship and practices can also be found here. “There is a possibility of obtaining an indulgence after kissing the cross and saying a prayer.” [Krzysztof K], “if you are looking for minyan6—it is the only place, but check the times. The litaim7 community is really small there, but some others also join for minyan.” [Polina T].

Some religious sites are seen by tourists as symbols of community: “This renovated «Choral» synagogue is perhaps the most and best-preserved symbol around which the city’s Jewish life still unfolds.” [Paolo M], as well as a symbol of the city, “it is one of the city’s showpieces” [Magdalena D], “Vilnius is famous for its beautiful churches. This one is a must-see!” [asiula J].

The authors of the comments draw on their own observations and experiences to emphasise the particular behaviour and clothing norms that are associated with religious places: “Note that there are separate entrances for men and women. Men should wear a hat, cap, or similar. Just be respectful, don’t take any pictures inside if there is a service going on, and people will treat you nicely and with great hospitality.” [Tobias T]. It is sometimes hypothesised that a lack of knowledge or a lack of preparation may act as an obstacle to entering the sacred place, as is illustrated here: “I did not dare to visit the Kenesa, not knowing the traditions and customs of the Karaites, although there was a great desire. I had to be content only with contemplation from the outside.” [sms911]. Details regarding the religious denomination of the readers are also included in the recommendations, e.g., “worth visiting not only for Jews but for non-Jews as well.” [Hannah J]; “I recommend it to everyone in Vilnius, whether they are believers or non-believers because it is exceptionally beautiful”. [Filip P]; “You don’t have to be an Orthodox Christian to enter the gate and admire this beautiful object.” [tadeusz r].

5.2. Aesthetic Admiration

The tourist’s gaze is characterised by a critical approach, in which admiration is an authentic experience (see MacCannell 1973). Consequently, any statements expressing amazement at the heritage objects viewed are evidence of their genuine admiration. The temple has been described as “an unusual oriental-style temple” [sms911]. It has also been lauded as “impressive” and “something amazing” with the commentator further noting that they “have never seen a building like it before.” [Piotr B] employed a plethora of superlatives to express his admiration for the sites in question, such as “beautiful”, “very impressive”, “rare remnant”, and “breathtaking”. These expressions of awe and admiration are applicable to all locations, irrespective of their religious affiliation. It emphasises the significant aesthetic value of objects in urban spaces.

5.3. Historical Details

The religious heritage of Vilnius is inextricably intertwined with its historical development and the composition of its population. These objects artefacts serve as symbols of the city’s past, contributing to its unique character as a multi-religious and tolerant metropolis, as evidenced by the prevalence of Baroque architecture. Micro-narratives in which tourists recall the city’s former inhabitants, including Jews and Karaites, also serve as a form of commemoration (Smith and Campbell 2017). In the case of victims of the Shoah and the communist regime, they represent a form of post-memory (Jones and Osborne 2020). It is therefore recommended that recommendations of specific objects, be made, in order to provide an opportunity for the very emotional interpretation of heritage: “Come visit this holy synagogue, the only synagogue of over 100 synagogues that existed in Vilnius before the Nazis8 ravaged the Jewish population and their holy sites; the synagogue of my ancestor, the holy Gaon of Vilna9; and feel the pain of Vilnius’ once glorious past, a city once considered to be the «Jerusalem of Eastern Europe»! Feel the pain of what it means to be a Jew in exile, and internalise the lesson to be learned from this pain: Time to come home! [YitzchakM].

5.4. Practical Tourist Information

Opinions that contained useful information for planning a stay in Vilnius were coded as ‘practical tourist information’. One of the many experiences that tourists have in urban areas is encountering randomness. This was also mentioned by users of the Tripadvisor platform: “By chance, we passed the synagogue and asked a guard if we could look inside.” [Ray]. Micro-narratives on social media can empower tourists by providing useful information, such as directions to interesting places, and making them feel more in control of their experiences: “Finding a church in the city centre is almost a real miracle” [Владимир Я]; “Needless to say, it was hard to find.” [Nikita B].

This category also contains information on how to explore the city. For example: “I was exploring the Old Town of Vilnius on foot […]” [sumantra_travel], “worth a trip on the 1 or 7 trolleybus to admire from the outside” [Perry Grinate].

This category includes the opening hours provided by the authors: “Visiting hours are quite limited (10 am–2 pm) and I believe it is closed to the public on weekends.” [Standpoint]. Visiting the objects is allowed, but only when the religious services are not taking place: It’s worth it, but be careful to avoid the mass times. You can’t just turn up at any time to experience the Eastern rites and their rich decorations, colours and smells”. [marian s].

There is no information about ticket prices in the comments because admission is free. The Choral Synagogue is the exception in this regard: “There is an employee at the entrance who demands two euros for entry” [SHTERA]. A few years ago, however, one of the visitors wrote: “don’t forget to make a donation” [RegardsVal].

Tripadvisor users pay attention to other financial considerations, such as parking prices. This is an important factor for many modern travellers: “Unfortunately, parking prices in the centre of Vilnius are excessive!” [Xyz A].

It is important to note that tourists value the opportunity to interact with the local people who manage the facilities. When positive experiences are encountered, meetings and conversations are frequently cited. For example: “The woman caretaker told us everything she knew, and she knows a lot and is clearly «sick» about her work. This mini-excursion, or rather even a conversation, turned out to be very interesting, warm, as if I was walking and talking with a friend, and not with a complete stranger.” [Антoн С]; “Upon entering, we started talking to a lady who was working at the synagogue. She took all the time for us and explained a few things to us, and showed us the synagogue. Top lady and very, very friendly.” [Ray]. Furthermore, such experiences influence tourists’ overall perception of the city and encourage them to come back: “I was received by a very kind and sweet woman, who showed me the building and we were talking for one hour or so. I really wish I had more time to spend there. A lovely memory from Vilnius.” [rota63]. If staff behave inappropriately, tourists will not hesitate to express their embarrassment and discomfort, particularly—if not especially—if the facility in question is also their place of worship: “She doesn’t ask, but demands, and looks at her as enemies of the people, although we greeted her in Hebrew. The place is beautiful […]. The impression was very spoiled by the aunt at the entrance.” [SHTERA]. Interestingly, although the quoted statements concern the same object, they were made several years apart: the positive ones are from 2015, while the negative ones are from 2018.

The issue of communication is also related to language. It is imperative to acknowledge that Vilnius has historically been a multilingual city. In addition to Lithuanian, the residents use Polish, Russian, and Belarusian languages in their daily lives. Many comments emphasise the possibility of participating in meetings and prayers conducted in a modern lingua franca is a possibility: “The church also hosts the English-speaking International Church of Vilnius, which meets for worship at 9.30 every Sunday morning—a good time to visit to see both the church building and its members.” [WWWorker].

Management staff can improve the quality and attractiveness of tourist destinations by taking into account situations suggested by tourists: “There are some information boards, but unfortunately, the information was only in Lithuanian.” [LucyFelthouse]. “The woman at reception didn’t speak English and there was no one inside to welcome us, so a little disappointed even though I can now say that I visited a synagogue” [Geoffrey Lalloué].

Short phrases, e.g., “is worth a visit” [Schwertner; susannorby], “Really something that should not be missed.” [Kim B] are usually concise summaries of opinions designed to encourage people to visit the places they mention.

First-person micro-narratives, as very short forms, are certainly not intended to replace book guides or the narratives of city guides who accompany individuals and groups. Nevertheless, they fulfil an important and inspiring function in contemporary tourist practice, especially in the pre-travel phase. The fragmented nature of information, if indeed it is true, has been shown to be memorable due to its repeated nature. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that this fragmented information draws attention to the uniqueness and attractiveness of a particular place. In both cases, the influence of these factors is such that a stay in a particular place, in this case, Vilnius, can be classified as falling into the categories of cultural and/or religious tourism.

In the context of religious heritage sites, visitors are expected to adhere to specific behavioral norms and dress code. These practices, from the perspective of the tourist experience, are mentioned by some opinion writers on the Tripadvisor platform, instructing readers on how to behave in a particular place.

The provision of practical information is of paramount importance. This encompasses days and hours of operation of the facility, the policy on entry fees, the anticipated costs of tickets, directions to the location, and the sequence of visits to the urban space.

The inherent weakness of short statements derived from memorised data is that they are often imprecise or even misleading. This can be evidenced, for instance, in the identification or equation of the Orthodox Church of the Holy Spirit with the Greek Catholic Church of the Holy Trinity. The contamination of the two holy places is hypothesized to have resulted from an insufficiently remembered story about the history and development of the Orthodox Shrine of the Lithuanian Martyrs.

As previously outlined, tourists utilise descriptive comments to signal problems or inconveniences in the provision of sites. This issue could be remedied by ensuring that site managers are aware of such comments. In the course of their evaluation of the selected religious sites, tourists made mention of a number of issues. These included the shortness of the opening hours, the manner in which the sites were made accessible to visitors, the poor forms of communication, and the behaviour of staff.

The temporal progression of tourist experiences can be analyzed by following the entries on social media in chronological order. This approach enables the study of the relationship between tourist experience and the changes occurring at the specific sites, such as renovations and refurbishments, and the introduction of new technologies. From the perspective of an attentive tourist reader, it is imperative to ascertain whether negative reviews have influenced the anticipated changes. The capacity for interaction inherent in social media platforms facilitates the process of verification, primarily through the establishment of connections between users and the potential for delving into the intricacies of micro-narratives.

The analysis concludes with a discussion of the usefulness of social media, including an aggregator such as Tripadvisor, for tourists and tourism industry representatives, as well as for researchers of contemporary cultural and religious tourism. The advent of these novel instruments facilitates the diagnosis and access of Vilnius’ multi-religious urban heritage to be diagnosed and accessed by tourists from diverse cultural, linguistic and national backgrounds. The opinions expressed provide substantial arguments and considerable amount of data that serve to reinforce the image of the city, which demonstrates significant potential for the development of the aforementioned forms of cultural and religious tourism among diverse visitor groups to Vilnius.

Author Contributions

The contribution of all authors to the various stages of the article creation is equal. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research has been supported by a grant from the Faculty of International and Political Studies under the Strategic Programme Excellence Initiative at Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland. The publication has been supported by a grant from the Priority Research Area Heritage under the Strategic Programme Excellence Initiative at Jagiellonian University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | It is worth mentioning that St. Anne, together with St. Barbara, was to be the patron saint of another unpreserved Renaissance church in the Lower Castle of Vilnius. It was built on the initiative of King Zygmunt II August (1520–1572) as a mausoleum for his two wives. Some authors confuse the two buildings. See (Guttmejer 2023; Śledziewski 1933–1934). |

| 2 | The Church and Monastery of the Holy Trinity (Lithuanian: Vienuolynas ir Šv. Trejybės cerkvė) is located on the other side of 7b Aušros Vartų Street. It has belonged to the Greek Catholics since 1609 and now belongs to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. |

| 3 | Jointly: Chinese—78 and Chinese (Taiwan)—71. |

| 4 | Only minor changes to punctuation and corrections of typographical errors have been made to the original spelling in English quotations. |

| 5 | A Jewish prayer book for use in synagogues and homes, containing prayers for weekdays and regular Sabbaths. |

| 6 | This is the smallest quorum required for public Jewish worship. It consists of ten men. |

| 7 | Lita’im (Hebrew לִיטָאִים) name refers to Jews who historically lived in the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. |

| 8 | A Nazi is a member of the National Socialist Party (NSDAP), which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1945. The term ‘Nazi’ is also used colloquially to Germans who invaded other countries and committed crimes against the populations of occupied territories during World War II, which lasted from 1 September 1939 to 1945. |

| 9 | Elijah ben Solomon Zalman (1720–1797) was a Lithuanian Jewish mathematician, grammarian, rabbi, Talmudist, and Kabbalist. He was one of the most important figures in the formation of the Misnagdim movement and Orthodox Judaism. Known as ha-Gaon mi-Vilna, the genius from Vilnius. On the occasion of the 300th anniversary of his birth, the Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania declared 2020 the year of the Gaon of Vilnius and the history of Lithuanian Jews. |

References

- Barbera, Giuseppe, Luis Araujo, and Salomé Fernandes. 2023. The Value of Web Data Scraping: An Application to TripAdvisor. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 7: 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beliatskaya, Ina. 2017. Understanding enhanced tourist experiences through technology: A brief approach to the Vilnius case. Ara: Journal of Tourism Research 7: 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Briedis, Laimonas. 2009. Vilnius: City of Strangers. Vilnius: Central European University Press, Baltos Iankos. [Google Scholar]

- Chomik, Piotr. 2011. Trzej wileńscy męczennicy i początki monasteru św. Trójcy w Wilnie. Studia Podlaskie 19: 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drema, Vladas. 1991. Vilniaus Šv. Onos Bažnyčia: Vilniaus Katedros Rekonstrukcija 1782–1801 Metais. Vilnius: Mokslas. [Google Scholar]

- European Capital of Christmas. 2025. Vilnius, Celje, and Noja: Europe’s Festive Capitals for Christmas 2025. Available online: https://europeancapitalofchristmas.org/vilnius-celje-and-noja-europes-festive-capitals-for-christmas-2025/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- European Commission. 2025. Vilnius—European Green Capital 2025. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/urban-environment/european-green-capital-award/winning-cities/vilnius-2025_en (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Gajdošík, Tomáš, and Anna Orelová. 2020. Smart Technologies for Smart Tourism Development. In Artificial Intelligence and Bioinspired Computational Methods. CSOC 2020. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Edited by Radek Silhavy. Cham: Springer, vol. 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzaroli, Andrea, Ivan de Noni, and Peter van Baalen. 2017. Vicious advice: Analyzing the impact of TripAdvisor on the quality of restaurants as part of the cultural heritage of Venice. Tourism Management 61: 501–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gąsiorowski, Szymon. 2018. Karaimi w Wilnie do wybuchu I wojny światowej. Rekonesans badawczy. Almanach Karaimski 7: 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelter, Hans. 2017. Digital tourism—An analysis of digital trends in tourism and customer digital mobile behaviour. International Journal of Heritage Tourism and Hospitality 14: 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, Ulrike. 2018. Influencer marketing in travel and tourism. In Advances in Social Media for Travel, Tourism and Hospitality: New Perspectives, Practice and Cases. Edited by Marianna Sigala and Ulrike Gretzel. London: Routledge, pp. 147–56. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmejer, Krzysztof. 2023. Kościół pw. św. Anny i św. Barbary na zamku wileńskim. Architektura 7: 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harviainen, Tapani. 2003. The Karaites in contemporary Lithuania and the former USSR. In Karaite Judaism. A Guide to Its History and Literary Sources. Edited by Meira Polliack. Leiden: Brill, pp. 827–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarkiewicz, Katarzyna. 2012. The Importance of the Cult of Our Lady of Ostra Brama/Aušros Vartai to the Polish and Lithuanian Religiosity. In Stanisław Wyspiański-Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis: The Neighbouring of Cultures, the Borderlines of Arts. Edited by Wanda Mond-Kozłowska. Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM, pp. 103–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Phil Ian, and Tess Osborne. 2020. Analysing virtual landscapes using postmemory. Social and Cultural Geography 2: 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempa, Tomasz. 2016. Konflikty Wyznaniowe w Wilnie od Początku Reformacji do Końca XVII Wieku. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu. [Google Scholar]

- Kempa, Tomasz. 2024. Na styku, światów ruskiego i łacińskiego. Związki wschodnich chrześcijan i protestantów w Wilnie w XVI i XVII wieku. Wschodni Rocznik Humanistyczny XXI: 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizilov, Mikhail. 2015. The Sons of Scripture: The Karaites in Poland and Lithuania in the Twentieth Century. Edited by Katarzyna Tempczyk and William Smith. Warsaw and Berlin: De Gruyter Open. [Google Scholar]

- Kłos, Juliusz. 1923. Wilno. Przewodnik krajoznawczy. Wilno: Wydawnictwo Wileńskiego Oddziału Polskiego Towarzystwa Turystyczno-Krajoznawczego. [Google Scholar]

- Kobeckaitė, Halina. 1993. Karaimi w Wilnie i Trokach. Konteksty. Polska Sztuka Ludowa 47: 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, Philip, Hermawan Kartajaya, and Iwan Setiawan. 2017. Marketing 4.0: Moving from Traditional to Digital. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Krajewski, Jarosław. 2013. Wilno i Okolice. Przewodnik. Pruszków: Oficyna Wydawnicza Rewasz. [Google Scholar]

- Kviklys, Bronius. 1985. Lietuvos bažnyčios. In Vol. 5: Vilniaus Arkivyskupija, 1 d., Istoriniai Bruožai, Vilniaus Miesto Bažnyčios. Chicago: Amerikos Lietuvių Bibliotekos leidykla, p. 296. [Google Scholar]

- Laukaitytė, Regina. 2012. Evangelikų Liuteronų Bažnyčios likimas Lietuvoje. Lietuvių Katalikų Mokslo Akademijos Metraštis. Serija B, Bažnyčios Istorijos Studijos 5: 393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Kevin. 2016. 5 Ttravel Brands Crushing Their Influencer Marketing Game Right Now. Available online: https://medium.com/bloglovin-influence/5-travel-brands-crushing-their-influencer-marketing-game-right-now-554857a2d047 (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Lenart, Agnieszka. 2014. Jeruszalaim de Lite. Obraz Wilna w opowiadaniu Grigorija Kanowicza Sen o Jeruzalem, którego już nie ma. Acta Polono-Ruthenica 19: 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, Daniel, Rob Law, Hubert van Hoof, and Dimitrios Buhalis. 2013. Social Media in Tourism and Hospitality: A Literature Review. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 30: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvak World. 2025. Cherishing Memory—Reviving Ties. Available online: https://www.litvakworld.com/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Liutikas, Darius. 2016. Religious Geography: Cult of Saints in Lithuania. Logos–Vilnius 88: 159–67. [Google Scholar]

- Liutikas, Darius. 2023. Sacred Space in Geography: Religious Buildings and Monuments. In Geography of World Pilgrimages. Social, Cultural and Territorial Perspectives. Edited by Luis Lopez. Cham: Springer, pp. 77–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, Dean. 1973. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. American Journal of Sociology 79: 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroszek, Józef. 1996. Kościół św. Anny w Wilnie—Zagadka historii i architektury. In Europa Orientalis. Polska i jej wschodni sąsiedzi od średniowiecza po współczesność. Studia i materiały ofiarowane Profesorowi Stanisławowi Alexandrowiczowi w 65. rocznicę urodzin. Edited by Zbigniew Karpus, Tomasz Kempa and Dariusz Michaluk. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu, pp. 103–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mickiewicz, Henryk. 2011. Dzieje kościoła św. Anny w Wilnie w świetle literatury. Toruń: Wydawnictwo MADO. [Google Scholar]

- Mikos von Rohrscheidt, Armin. 2016a. Turystyka kulturowa. Fenomen, potencjał, perspektywy, 3rd ed. Poznań: KulTour.pl. [Google Scholar]

- Mikos von Rohrscheidt, Armin. 2016b. Analiza programów imprez turystycznych jako podstawa typologii uczestników turystyki religijnej. Folia Turistica 39: 65–99. [Google Scholar]

- Minkwitz, Anna. 2018. Możliwości wykorzystania serwisu Tripadvisor jako źródła danych na etapie ich gromadzenia w planowaniu rozwoju turystyki w skali lokalnej. Turyzm 2: 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroczek, Anna. 2019. Kult Matki Boskiej istotnym elementem tożsamości krain. In Między Śląskiem a Wileńszczyzną. Edited by Krystyna Heska-Kwaśniewicz, Jolanta Januszewska-Jurkiewicz and Ewa Żurawska. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, pp. 190–97. [Google Scholar]

- Neuhofer, Barbara, Dimitrios Buhalis, and Adele Ladkin. 2015. Smart technologies for personalized experiences: A case study in the hospitality domain. Electron Markets 25: 243–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niezgoda, Agnieszka. 2017. Rola doświadczeń i relacji z podróży w kształtowaniu wizerunku miejsca. Marketing i Zarządzanie 1: 221–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, Marek. 2017. Atrakcje turystyczne światowych metropolii w opinii użytkowników TripAdvisora. Studia Periegetica 19: 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pataca, Ermelinda Moutinho, and Cristina Borges de Oliveira. 2016. Writing of biographical micro-narratives of LusoBrazilian travelers: Conections between the History of Science in Brazil and teaching. Educação e Pesquisa 42: 165–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawluczuk, Urszula A. 2015. Osiemnastowieczne Wilno. Miasto Wielu Religii i Narodów. Białystok: Libra s.c. Wydawnictwo i Drukarnia PPHU. [Google Scholar]

- Pažėraitė, Aldona. 2013. Jewish Prayer Halls and Synagogues in Vilna, 1914–1920. In Jews in the Former Grand Duchy of Lithuania Since 1772. Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencarelli, Tonino. 2020. The digital revolution in the travel and tourism industry. Information Technology & Tourism 22: 455–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencarelli, Tonino, Luciano Gabbianelli, and Enrico Savelli. 2020. The tourist experience in the digital era: The case of Italian millennials. Sinergie Italian Journal of Management 38: 165–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkūnas, Darius. 2011. The Repression of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Lithuania during the Stalinist Era. Klaipėda: Klaipėdos Universiteto Leidykla. [Google Scholar]

- Piechocka, Anna. 2021. Zarządzanie reputacją hotelu na portalu TripAdvisor—Analiza strategii stosowanych przez polskie hotele. Studia Periegetica 33: 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Adam. 2014. The power of TripAdvisor. Available online: https://medium.com/@socialpolly/the-power-of-tripadvisor-aa271d9f6e5 (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Račiūnaitė-Paužuolienė, Rasa. 2022. The Identity of Vilnius: City of Mercy and Pilgrimage. Logos 113: 181–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rusnak, Dariusz. 2015. Losy prawosławnych monasterów Wilna podczas bieżeństwa i po wojnie. Latopisy Akademii Supraskiej 6: 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Sandri, Olivier. 2013. City Heritage Tourism without Heirs. Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayın, Ömer. 2024. Understanding Digital Turn in Urban Research: A Bibliometric Analysis of Contemporary Global Urban Literature. Kent Akademisi 17: 701–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Laurajane, and Gary Campbell. 2017. ‘Nostalgia for the Future’: Memory, Nostalgia and the Politics of Class. International Journal of Heritage Studies 23: 612–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowicz, Małgorzata. 2017. Pan Jezus był Polakiem, a Matka Boska Litwinką—Implikacje konfliktu polsko-litewskiego i uwarunkowań politycznych na rozwój kultu Bożego Miłosierdzia w Wilnie. Turystyka Kulturowa 3: 135–47. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Eliyahu. 2013. The Genius: Elijah of Vilna and the Making of Modern Judaism. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Szlewis, Grigorij. 2006. Правoславные храмы Литвы. Vilnius: Святo-Духoв Мoнастыр (Prawosławnyje chramy Litwy, Swiato-Duchow Monastyr), pp. 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Śledziewski, Piotr. 1933–1934. Kościół św. Anny—Św. Barbary intra muros castris vilnensis. Ateneum Wileńskie 9: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tereszkiewicz, Anna. 2018. Każde Pana słowo w komentarzu jest niczym poezja. Odpowiedzi właścicieli hoteli na recenzje klientów publikowane na portalu TripAdvisor. Media—Culture—Social Communication 2: 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripadvisor. 2025. Centrum Multimedialne. Available online: https://tripadvisor.mediaroom.com/PL-about-us (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Uğurlu, Kaan. 2022. Technology in tourism marketing. In Handbook of Technology Application in Tourism in Asia. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, pp. 69–113. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2025. World Heritage Convention: Vilnius Historic Centre. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/541/ (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Urry, John. 2002. The Tourist Gaze. London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi: SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Vaičiūnas, Vytautas S. 2005. Promieniowanie Ostrej Bramy na Europę. In Polska i Litwa-Duchowe Dziedzictwo w Europie. Edited by Marek Chmielewski. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL, pp. 171–80. [Google Scholar]

- Vaišvilaitė, Irena. 2022. Walks in Christian Vilnius. Translated by Jayde Will. Vilnius: Baltos Lankos. [Google Scholar]

- Vanagas, Nerijus, and Jonas Jagminas. 2011. The potential of community-based tourism development in vilnius district municipality. Management Theory and Studies for Rural Business and Infrastructure Development 28: 157–63. [Google Scholar]

- WMF (World Monuments Fund). 2025. Vilnius Choral Synagogue. Available online: https://www.wmf.org/monuments/vilnius-choral-synagogue (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Woolfson, Shivaun. 2013. History Everything Speaks: The Jewish Lithuanian Experience Through People, Places and Objects. Ph.D. thesis, University of Sussex, Sussex, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewska, Urszula. 2015. Karaimi Wileńscy w Okresie Międzywojennym. Protokoły z Posiedzeń Organizacji Karaimskich, Edycja Źródeł. Białystok: Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. [Google Scholar]

- Zalkin, Mordechai. 2025. Vilnius. Translated by Barnett Walfish. In The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Edited by Gershon David Hundert. New York: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Available online: https://encyclopedia.yivo.org/article/982 (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Zhang, Yuhan, and Zoltán Szabó. 2024. Digital Transformation in the Tourism Industry: A Comparative Literature Review. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences 72: 178–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).