1. Introduction

The process of grieving the loss of a loved one is generally a personal journey as the bereaved deals with all the emotions involved and reestablishes a new relationship with the deceased. Grief is not a primary emotion but is associated with a wide array of emotion-experiences, including sadness, anger, depression, relief, disappointment, and feelings of abandonment, among others (

Ben-Ze’ev 2022). The emotions associated with grief can be felt intensely in the body, even as physical pain. There is also a cognitive dimension to grief that can hijack attention and consciousness as the bereaved ruminates obsessively on the details of the relationship, on self-blame, or fantasies of happier outcomes (

Cholbi 2022). Thus, in addition to emotion regulation, new structures for meaning-making and more helpful and healthy thought patterns are important to the process of grief. These cognitions help to accommodate a new relationship with the deceased outside of the person’s physical presence—the continuing bonds (

Cholbi 2022). There is evidence that continuing bonds facilitate the cultivation of a new and ongoing relationship and facilitate the grieving process (

Neimeyer et al. 2006). The griever may also isolate from others as a self-protective measure, and the subsequent loneliness can pull them away from potential support from others (

Koster 2022).

While grief is an expected and normal response to the loss of a loved one, for some, grief is characterized by prolonged distress and significant impairment. The

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (

DSM-5, TR; American Psychiatric Association,

2022) characterizes this as prolonged grief disorder (PGD) and is associated with overall disruptions in daily functioning. Factors that predict the occurrence of PGD include attachment style, previous experience of loss and trauma, and minimal preparation for death (

Lobb et al. 2010).

Though grief is frequently considered a personal journey, there are important communal dimensions to grieving influenced by cultural and religious messages about what is acceptable grief. Research is demonstrating that healthy adaptation to grief can enhance personal growth and resilience (

Hurst and Kannangara 2022;

Neimeyer et al. 2018). New patterns of coping and growth that follow upon the grieving process can potentially enhance resilience, with the final outcome that the bereaved is more adaptive. One of those growth-oriented characteristics is spirituality and a greater capacity for transcendence (

Hatala 2011). Thus, for some, grieving may not only be an intrapersonal and interpersonal journey of resilience, but a transpersonal journey that opens a range of opportunities that fall under the domain of transcendence. The emotions classified as self-transcendent are a central focus of this research study.

1.1. Self-Transcendent Emotions

Self-transcendent emotions (STE) are distinguished from

positive emotions by virtue of being associated with a weakening of self-other boundaries and feelings of connection. Self-transcendent experiences have been defined as “transient mental states of decreased self-salience and increased feelings of connectedness” (

Yaden et al. 2017, p. 143). The most recognized and researched self-transcendent emotions are gratitude, compassion, and awe.

Abatista and Cova (

2023) have classified self-transcendent emotions as either social or epistemic. The social category refers to emotions based on meaningful connections, such as compassion and gratitude. Epistemic emotions alter perception and expand awareness, and include emotions such as wonder, awe, and fascination. The more relational self-transcendent emotions of gratitude and compassion are the focus of this study for their relational orientation and ability to enhance prosociality (

Stellar et al. 2017;

Van Cappellen 2013). The primary and secondary appraisals associated with self-transcendent emotions have been associated with motivations for behaviors that are other-focused, such as attachment, cooperation, and increased social bonding (

Stellar et al. 2017). They are also associated with an expanded sense of self that goes beyond the egoic to be more inclusive of others (

Hlava et al. 2024). Self-transcendent emotion-experiences have also been shown to be highly embodied, with scores on interoception correlating positively with awe, compassion, and transpersonal gratitude (

Hlava et al. 2024). STEs have been linked with enhanced life satisfaction (

Lynch and Troy 2021;

Tornstam 2011), stress reduction and happiness (

Church et al. 2022), and spirituality (

Saroglou et al. 2008). Because of the complex phenomenological profile of gratitude and compassion, and the varied appraisals and cognitions associated with them, we have chosen to label them as self-transcendent emotion-experiences (STEs). This study explored the relationship of STEs with grief when enhanced by after-death communication.

1.2. Grief and Gratitude

Gratitude is an emotion experience that arises as appreciation in response to a benefit. Gratitude is traditionally characterized as having three essential elements. The first is a perceived benefit. The second is a beneficiary that is the source of the benefit or gift. The third is the benefactor, who is in receipt of the benefit and feels a measure of gratitude in response (

McCullough et al. 2002;

Roberts 2004). Rather than a single categorical emotion, gratitude is a complex profile of cognitive appraisals and emotions, making gratitude also an emotion-experience. The cognitions associated with gratitude include a determination of the intention of the gift-giver, the level of sacrifice involved, and the value of the gift. Feelings associated with gratitude might include appreciation, admiration, indebtedness, comfort, security, joy, love, and being blessed (

Hlava and Elfers 2014). Because of its complex profile, gratitude has been characterized as a positive emotion, an empathic emotion (

Fredrickson 2004), and a self-transcendent emotion (

Stellar et al. 2017).

The softening of self-other boundaries inherent to an exchange of benefits is part of the subjective experience of gratitude and is part of relationship building (

Algoe et al. 2008) and relationship maintenance (

Hlava 2010;

Kubacka et al. 2011). The diminishment of self-other boundaries is also a feature of self-transcendent emotions. When the appraisal of a benefit goes beyond relational benefits to include an appreciation for nature, life, or a higher power, gratitude has the potential to become a transcendent experience (

Elfers and Hlava 2016;

Steindl-Rast 2004). The subjective experience of gratitude can rise to the level of a peak experience of oneness or unity, which accounts for the presence of gratitude as a spiritual practice or discipline (

Prem 2020). As

Emmons (

2008) noted, “Gratitude’s other nature is ethereal, spiritual, and transcendent” (p. 122).

There is increasing evidence that a positive grief experience is associated with resilience (

Beckley 2022).

Elfers et al. (

2023) explored the relationship among grief, gratitude, and nondual awareness. A regression model showed that higher scores on measures of transpersonal gratitude and nondual awareness predicted resilience in coping with grief.

Lau and Cheng (

2011) showed that a brief gratitude experience could reduce anxiety around death in older adults.

Greene and McGovern (

2017) studied adults who had experienced early parental death. Findings revealed that dispositional gratitude was associated with posttraumatic growth and overall well-being as well as a reduction in depression. Participants reported a belief that life is precious and a greater appreciation for loved ones as contributing to their enhanced gratitude.

Frias et al. (

2011) also determined that an intensification of awareness in personal mortality was associated with enhanced gratitude for life.

1.3. Grief and Compassion

The term compassion is composed of the two Latin words

com and

passio, meaning to suffer with, or suffer together. In psychological terms, compassion is defined as “an affective response to another’s suffering and a catalyst of prosocial behavior” (

Stellar et al. 2017, p. 572). However, the “other” who is suffering can be plants, animals, or any sentient being. The two components of the definition make compassion not only a reaction, but a motivator to reduce the suffering of the other, making it a dynamic experience. Compassion is thereby intimately tied to altruistic behaviors (

DeSteno 2015). A study by

Saslow et al. (

2013) showed that individuals identifying as spiritual showed higher levels of compassion and behaved more altruistically, in contrast with those identifying as religious.

It is important to distinguish compassion from empathy. Empathy is also an attunement to the suffering of an “other”, but responds with an attempt to understand the suffering. It is primarily a cognitive response. As already noted, compassion responds with a genuine desire to reduce the suffering. This distinction separates compassion from sympathy and pity, in which sorrow is felt for the sufferer. Compassion also requires an appraisal of the nature and degree of suffering. Furthermore, compassion is distinct from self-compassion, a construct that has received a lot of attention in research. Compassion is interpersonal and transpersonal. It is entirely other-focused and relational. Self-compassion, on the other hand, is intrapersonal and self-referential. It is a turn toward the suffering of the self with love and kindness.

Compassion has been shown to be a highly prosocial emotion and is associated with increased parasympathetic activity (

Stellar et al. 2017). In exploring the neuroscience of empathy and compassion,

Chierchia and Singer (

2017) noted that empathy may not be associated with prosociality to the same degree as compassion. They found that empathy for another’s pain engages areas in the brain associated with negative affect, whereas compassion engages areas associated with positive affect, warmth, and concern. The researchers also show evidence that compassion is a skill that can be trained.

As an attunement to the suffering of others, compassion is difficult to classify as a strictly positive emotion; rather, the subjective experience is a complex profile of feelings, emotions, and somatic sensations. To feel or “take on” the suffering of another takes both courage and tenderness (

Harris 2021) and may be a poignant experience, putting it in a category beyond the duality of the positive or negative valence of emotion. Sheffer et al. 2022 stressed that if compassion were always a warm and positive experience, people would seek it out. In fact, their research shows that in many cases, people avoid compassion because it is psychologically costly and can lead to burnout. As with too much suffering, too much compassion can demand a psychological toll. They determined that people are more likely to show compassion to those in closer relationships than in more distant relationships.

Garrido-Macías et al.’s (

2023) research on compassion-related appraisals found that compassion was higher when there was a feeling of similarity with the person in need, and when the person was more victimized and less personally responsible for their suffering.

The role of compassion in managing feelings of grief has received less attention in the literature than the role of self-compassion. Addressing adversity and life challenges in a positive and healthy way is now being recognized as a potential catalyst for enhanced empathy-mediated compassion, resulting in behaviors that lead to the reduction of suffering in others (

Lim and DeSteno 2016). What has yet to be established are the conditions and risk factors that predict positive outcomes to adversity, one of which is grieving a significant loss.

1.4. After-Death Communication

The experience of communicating with a loved one after death is not an uncommon phenomenon. Known as

after-death communication (ADC), the experience can take the form of hearing the loved one’s voice, visual or auditory phenomena, sensing their presence, a synchronicity, or a vivid dream, among others. ADC experiences may occur spontaneously or may be deliberately facilitated during the grief process (

Pait et al. 2023;

Wassie 2022). They are deeply personal experiences and often go unreported for fear of ridicule or being considered mentally unstable (

Beischel 2019).

Penberthy et al. (

2023) summarized a variety of studies, noting that estimates of the frequency of ADCs range from 25 to 50% of the population. Also unclear are the factors that predict whether someone will experience ADC.

The experience of ADC has been studied as an exceptional human experience as well as in its relationship to grief. ADCs are sometimes categorized under the construct of continuing bonds, a phenomenon describing an ongoing attachment to the deceased (

Neimeyer et al. 2006). Relationship maintenance can take many forms as the person accommodates to the reality of the absence of physical presence. Grief responses to violent death are associated with hallucinations and illusions of the deceased, referred to as externalized continuing bonds, as opposed to more internalized representations of the deceased that accept the reality of physical absence (

Field and Filanosky 2009). Nonviolent death has been associated with more internalized representations of the deceased. Continuing bonds are associated with higher levels of meaning-making around the death of a loved one, which is predictive of lower levels of trauma and stress during the grieving process (

Neimeyer et al. 2006).

Wassie (

2022) found support for the use of meditation-induced ADCs in meaning-making that supported the strength of ongoing continuing bonds with a loved one.

Beischel et al. (

2014) found that ADCs, using psychic mediums, had a positive impact on bereaved individuals by strengthening bonds with the deceased.

Botkin and Hogan (

2014) pioneered a therapeutic strategy for processing core sadness through the induction of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) developed by Francine Shapiro in 1987. This technique allows the client to process the distressing nature of the loss of a loved one while bypassing emotions of anger and guilt, often co-morbid with grief.

ADCs are generally, but not always, a positive life experience in those who experience them. Having direct communication with a deceased loved one has been associated with a reduction in death anxiety, enhanced belief in an afterlife, and increased spiritual orientation (

Kwilecki 2011;

Penberthy et al. 2023). The experience has been shown to be moderated by strong emotional reactions to the ADC and a desire for physical contact.

Tatarsky (

2016) found ADCs to be associated with spiritual transformation. Survivors of suicide loss who have experienced positive ADCs, such as dreams or feeling the presence of the deceased, report more continuing bonds with the deceased (

Jahn and Spencer-Thomas 2014).

1.5. Study Rationale

What remains unclear in scholarly literature is the potential for ADCs to be a support and catalyst for enhanced transcendence, specifically the development of STEs as part of the grieving process. Are ADCs related to enhanced feelings of gratitude and compassion? Furthermore, do these facilitate continuing bonds with the deceased, meaning-making, and resilience in grief? As a caveat, this research does not aim to determine the concrete reality of after-death communication or models of existence beyond death. Rather, ADCs will be treated as a psychological reality that influences the process of grief.

In an unpublished study with 94 participants,

Elfers et al. (

2023) found strong correlations among grief resilience, continuing bonds, compassion, and transpersonal gratitude. Those participants identifying as having experienced an ADC showed higher scores on all measures, suggesting that a duplication of this study with a wider population warrants further investigation. This research predicts that ADCs will be at least moderately correlated with resilience through the grief process as well as the development of the self-transcendent emotions of compassion and gratitude.

1.6. Research Question

For the purposes of this study, after-death communication is defined as perceived, clear, and direct communication from the deceased. These may include visions, hearing voices, dreams, synchronicities, or sensing a person’s presence. The communication may either be spontaneous or deliberately facilitated through a medium, a psychic, or a therapist. The research question guiding this study was: In what way do experiences of after-death communication inform the cultivation of self-transcendent emotion experiences (gratitude and compassion) as part of the grieving process?

1.7. Research Design and Method

There are currently no psychometric assessments of ADC, given that the form of communication is so varied. Consequently, this study asked participants whether they had had some form of ADC and compared means scores on measures of grief, continuing bonds, compassion, and gratitude between those responding as yes and no. This research study employed a convergent mixed-methods design comprising two sources of data collection: (a) a correlational study consisting of four validated measures, and (b) a grounded theory study to explain the correlational data and generate a theory (

Creswell and Plano Clark 2017). Two distinct samples were recruited that were implemented simultaneously, one for interviews (

N = 44) and one survey sample for the assessments (

N = 329). Both interview and survey participants signed an informed consent approved by the researchers’ university IRB.

3. Study 2

The second study used informed grounded theory as described by

Thornberg (

2012) to explore a possible theory to explain the correlation among the experience of an ADC, compassion, and gratitude. A theory-driven approach to the qualitative data was chosen to capture the relationships among the research variables. Informed grounded theory allows the researcher to compare the data with preexisting theories and current findings to create a theoretical model that builds upon existing data (

Themelis et al. 2022).

A total of 44 participants were recruited and interviewed to explore their lived experience of after-death communication and its relationship to grief resilience and self-transcendent emotion-experience. Given that lived experience was the focus, a history of some form of ADC was the primary inclusion criterion. The recruitment for this study was more heavily weighted toward female participants, meaning that the findings may be biased along gender lines. This sample was distinct from the sample recruited for Study 1. Participant demographics are listed in

Table 1. Each interviewee was led through a brief centering exercise to focus attention inward. This was followed by a scripted meditation in which they recalled the details of a significant ADC experience in order to elicit stronger memories and recall somatic impressions. Afterward, a semi-structured interview ranging from 45 to 75 min was conducted with each participant. An identical script was used for each interview to guarantee fidelity and consistency in the instructions for eliciting memory recall.

Participants were recruited through personal contacts and referrals from friends and colleagues. Respondents were screened through a brief interview to determine their appropriateness for the study. Inclusion criteria included English-speaking adults in the US over the age of 18, competent to speak articulately about their phenomenological experience of after-death communication. All participants experienced the loss of a significant loved one, were at least 1 year post-loss, and had attained a level of resilience in their grieving process. Exclusion criteria included those with less than 1 year post-loss and currently dealing with trauma responses of PGD. Eligible participants signed an informed consent prior to the interview. Interviews were conducted either in person or via Zoom and were audio recorded (see

https://zoom.us/legal for details of Zoom’s privacy policy, accessed on 3 March 2025). The interviews were transcribed by the researchers as well as online HIPAA-compliant transcription services. Data from interviews were analyzed using thematic content analysis through DeDoose (version 9.2.22), an online qualitative data analysis program.

3.1. Data Analysis

After the first eight interviews, the textual data were analyzed to determine emergent themes. An iterative process of conducting further interviews and analyzing the data continued throughout data collection to determine the saturation of themes. An abductive approach was used in the derivation of themes to be consistent with informed grounded theory, beginning with an inductive comparison and alternating with a deductive analysis. To confirm the accuracy of interpretation, the researchers repeatedly returned to descriptions of participants’ lived experiences.

The final steps involved comparing the emerging themes from the grounded theory with the results of the correlational data. Various models of grief resilience were also considered to be data from the interviews were compared with existing theories. The two data sets—thematic content and correlational data—were triangulated to derive a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship among ADCs and self-transcendent emotion experience. The primary goal of the analysis was to create an overall theory that best explains relationships among the data and existing theories.

3.2. Findings for Study 2

After several iterations of coding and categorizing the data from participant interviews, three clear themes emerged. Consistent with narrative and social constructivist perspectives of grief (

Neimeyer et al. 2009,

2014), the narratives offered by participants described an unfolding process of meaning-making inherent in the grief process. This process of meaning-making often included a process of reconciliation with the experiences of ADC, facilitating shifts in worldview, and choices in how participants supported their pathway through grief. Participant descriptions of the role of ADC in facilitating the grieving process included descriptions of STEs, such as gratitude and compassion. This was exemplified by Joselyn, who asserted, “

I can’t even imagine my grieving process without it. I feel so fortunate to have this as part of it.”

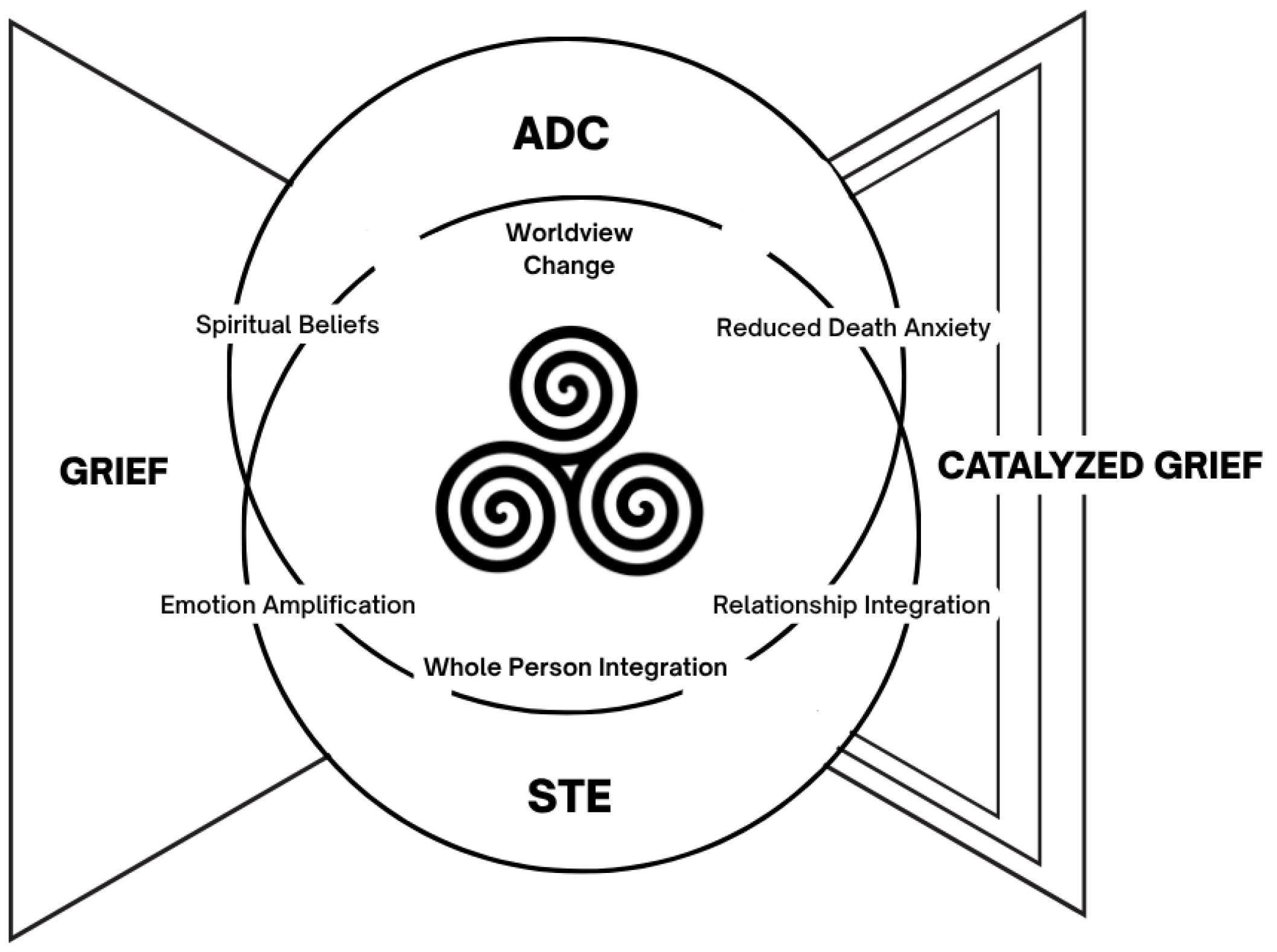

Participant testimony revealed that ADCs can initiate healing, growth, and spiritual connection, leading to the opening of the heart and mind and the expansion of emotions in the grieving process. Through the exploration of the narratives, three core themes emerged that illustrated the dynamic interplay between ADC and STE in the grieving process, each with distinct subthemes that further detail the nuances of these experiences: (a) Catalyst of Grief, (b) Perspective Shift, and (c) Whole-Person Integration.

3.3. Grief Catalyst

ADCs appear to offer a direct pathway to emotion-experiences associated with grief, increasing the intensity of these emotions and generating an opening in the grieving process itself. While grief can often be an internal, and at times isolating, process that draws us inward into the self, ADCs served as a catalyst. This created a container that expanded beyond the self into the subtle space of a continued bond with the deceased, moving through intra, inter, and transpersonal domains of experience. All participants spoke directly about the experience of grief changing through the experience of the ADC, which was expressly captured in Chase’s statement: “it’s in that communication that the grieving process happens.” Amily noted, “in the grieving process, it (ADC) makes you want to be in a space where you are tuning in rather than tuning out.” These descriptions were exemplified in the following subthemes: Relationship Integration and Amplification of Emotion-Experiences.

3.4. Relationship Integration

Participants (n = 39) described how ADC played a significant role in reconfiguring complex relationships and facilitating the integration of complex emotions and cultivation of meaning within the context of the relationship with the deceased. Vallarta22 noted, “I didn’t give my mom enough credit for who she was. And she was brilliant…and she loved everybody. And that’s probably part of my personality.” For many (n = 30), ADC fostered compassion for the deceased, leading to healing, forgiveness, and resolution of tensions, conflict, or resentments previously held in the relationship with the deceased. Beautiful MPA expressed, “in the end is the compassion, and the love, and the letting go, and the not holding on to, and releasing any kind of resentment”, underscoring this transformative effect. Some participants (n = 12) described developing a new relationship with their memory of the deceased, as illustrated by RFF, who shared that the ADC “definitely softens my memory”, and Joselyn, who affirmed, “it’s improved my memories. It’s helped me integrate some of the things that weren’t so great about our relationship.”

The experience of grief was further catalyzed for many (n = 33) who experienced continuous relationships with their loved ones through ongoing ADC. D explained, “the relationship hasn’t ended. It’s just changed”, supporting a shift in how the relationship is experienced. These engagements with the ADC process seemed to foster continual shifts in the internal conceptualization and felt sense of the relationship with the deceased, supporting movement through the flow of grief. This was exemplified by JT, who stated, “the grief has grown and blossomed.…It’s no longer grief and sadness, but it’s moved into something that is transcendent.”

3.5. Amplification of Emotion-Experiences

ADCs consistently generated strong emotion-experiences, including STE. Participants (n = 35) shared articulations of intense emotions such as awe at synchronicities or spiritual presence, compassion for the deceased, and gratitude for continued connection, expanding the emotional terrain of the grieving process. Through the experience of ADC, pleasant and painful emotions were described as carrying a degree of intensity and amplification. Emotions such as gratitude, awe, love, wonder, as well as resentment, anger, sadness, and fear, among others, were often experienced concurrently and were not incidental but described as core affective responses during or after ADCs. Participants exemplified this varietal range in emotion-experience with descriptions such as “feeling peaceful and truly loved and fulfilled” to “feeling a fear of opening up to darkness.”

Participant descriptions suggested that as this full range of emotions was heightened and brought to the surface, they could be processed more readily, supporting the catalyzation of not only the emotion, but of the perception of the self and others through the unfolding process of grief. Amily described this unfolding process as, “I feel the pause, I feel the emotions coming through all through my chest, my heart getting expanded.” For some individuals (n = 28), ADC connections and the associated emotions generated a sense of protection, guidance, and “finding meaning from the loss.” Others (n = 19) shared experiences of curiosity, facilitating a shift from isolation in grief toward movement to “discover something bigger than ourselves.” The presence of ADC and STE with grief, in this context, seemed to foster an openness to experiencing emotional depth as well as spiritual expansion, creating a path from personal suffering to transpersonal insight.

3.6. Perspective Shift

The lived experience of ADC consistently facilitated a shift or amplification of belief structures that influenced grief processing, and in some cases, a reconstruction of personal identity. Participants (n = 35) described an expansion of perception beyond what had been previously held as an absolute, facilitating changes in both beliefs and actions. Participants described shifts in perspective that occurred across intra, inter, and transpersonal domains of experience. Buffalo Jay asserted, “It’s really opened up a different way to view the past”, Klara described having “…a direct call to be of help while I’m incarnated in this life to…help others through their suffering”, and RFF noted, “my definitions have shifted in terms of cosmology and theology.” Perspective shifts were exemplified in the following subthemes: Spiritual Beliefs and Reduction of Death Anxiety.

3.7. Spiritual Beliefs

Perspective shifts in spiritual beliefs seemed to further amplify experiences of STE, creating space for forgiveness, shifts in life priorities, and clarity in life purpose. Participants (n = 41) described ADC as a catalyst for deep spiritual transformation, reshaping their understanding of life, death, and human connection. These experiences reaffirmed or expanded spiritual worldviews, offering renewed meaning and continuity. Chase shared, “It’s affected my outlook on life because I believe that the spirit and the life of that spirit goes on.” This continuity reframed grief not as a final separation, but as a transition into a different kind of relationship with the deceased. Many participants (n = 28) reported an increased openness to spiritual practices and a growing trust in unseen dimensions of existence that offered both comfort and guidance. Thalia mentioned “honoring life as more than what we can see or experience with our senses.” The shifts in spiritual belief appeared to foster intentional engagement in supportive practices (e.g., journaling, meditation, rituals, memorial service, etc.) that contributed not only to the support of the transformation of grief but also to a sense of identity reconstruction, offering hope and optimism for the future.

ADC often cultivated a sense of sacred interconnectedness. Diana described being able to “connect on a deeper, more spiritual level—to God, to myself, and also to sacred land,” illustrating how the experience expanded her spiritual awareness beyond personal loss to include communion with nature and the divine. RFF echoed this by stating, “I definitely believe that we’re all absolutely very much connected in some way…and it’s definitely taken me a lot closer to…the idea that we’re all one.” This perceived unity fostered compassion, gratitude, and an expanded sense of identity. Spiritual beliefs became more experiential than dogmatic, grounded in direct encounters that helped participants reconstruct meaning, navigate grief, and deepen their sense of purpose and connection with both the living and the deceased.

3.8. Reduction of Death Anxiety

A notable subtheme that emerged from the findings was the reduction of death anxiety experienced by participants. For many (n = 25), ADC triggered or confirmed a shift in their understanding of death not as a final loss, but as a transition into another state of existence. This shift in perspective helped to relieve the existential dread that often comes with mourning. One participant stated unequivocally, “I am not afraid of death”, while another reflected, “So I do believe that there is more to life than this physical world. And that gives me a great deal of comfort.” These thoughts demonstrated how spiritual connection through ADC can aid emotional development and alleviate concerns about death.

Furthermore, participants frequently linked this transition to a renewed sense of thankfulness and respect for life. Rather than surrendering to fear or the weight of grief, they reported experiencing a stronger quality of presence and sense of purpose. One participant said, “I guess I just have more of a positive outlook on life now.” This adjustment in mindset and perspective suggests that ADC encounters not only help people cope with death, but also guide them toward a more purposeful life. When viewed through this lens, death turns from a conclusion to a spiritual invitation to value the life that remains.

3.9. Whole-Person Integration

Participants (n = 41) consistently described unique experiences of integration, wherein their relationship with the deceased, thoughts, beliefs, emotion-experiences, and perceptions of the self came together, fostering a sense of wholeness. The shift from experiencing the loss of a loved one as a loss of a part of the self, transformed through the embodied experiences of the ADC and a felt sense of the continuing bond. The somatic nature of the ADC seemed to facilitate an expanded and integrated experience of the self. Participant descriptions of ADC frequently included strong embodied experiences of sensation (n = 33) and emotion that included a felt sense of temperature changes (internal and external), as well as auditory (n = 21) and olfactory (n = 11) experiences related to the deceased. Consistent with somatic experiences of STE, these embodied experiences fostered deepened felt senses of connection and, at times, an expanded sense of self. The expansion of connectivity supported the grief process through providing an experience of comfort, support, guidance, and peace. In some cases, symbolic observations (n = 27; animals, lights, songs) or synchronicities (n = 28) served as somatic anchors, providing a visceral sense of connection with the deceased experienced through the sensory pathways of the body. The embodied nature of the somatic interplay of the ADC experience with the STE seemed to serve as a bridge that supports the integration of the loss with the transformation of self-perception. Joselyn shared that due to her experience, she has become “…even more expanded as somebody who can hold multiple truths at once.” This experience of integration and expansion was echoed in Michelle’s description of carrying an appreciation for “that expanded experience of what it means to be alive.” Significant aspects of whole-person integration were exemplified in the subthemes of Ancestral Connection and Expanded Felt Sense of Relationship.

3.10. Ancestral Connection

Participants (n = 37) described that their experiences of ADC included outreach from past family members of generations they had previously met, as well as ancestors beyond their direct knowing. These experiences of ADC not only served as a bridge to a new path forward through grief, but also served to expand the individual’s perception to include a relationship to the past. The ADC experience generated a sense of connection to ancestry beyond the deceased, noting awareness of part of a larger lineage. Michelle shared that ancestors she discovered through genealogy study alongside her father revealed themselves to her through ADC, and she was able to heal generational wounds “literally from every configuration possible.” Larry suggested that “those moments of unexplained phenomena are explainable and you just have to be open to the possibility that your ancestors are hoping you get to where you’re supposed to go.” Swan also recognized the influence of their ancestors’ communication in their ADC, stating, “I feel more connected to my family now.”

Several participants shared the importance of their healing journey, which involved learning lessons from their family’s past. Buffalo Jay shared, “knowing the history of my ancestors and my parents, I’ve made conscious choices not to repeat.” Lily shared her studies on this subject, explaining that “we carry the history of our ancestors in our bodies and from trauma response, and that those trauma responses can be addressed through ancestral connection.” This healing dimension was further emphasized as Drew shared that our ancestors desire “to be engaged with us and by us as a resource.” These narratives collectively suggested that ancestral connections through ADC experiences serve not only as a means of communication but also as pathways for intergenerational healing, guidance, and supporting movement toward wholeness.

3.11. Expanded Felt Sense of Relationship

Participants (n = 40) described experiencing an embodied understanding of connection and relationship that expands beyond the physical form. Participants were also clear in that the felt sense of the relationship at times included waves of sadness, tearfulness, and an awareness of the loss of the physicality of the relationship, which was described by Amily as “a very intriguing experience of being happy and grateful, but at the same time sad.” Throughout the participant narratives, there was a thread of feeling the ongoing connection with the deceased. Lize stated, “that connection doesn’t go away”, which was echoed by Swan, who shared that “the feeling of connection is still very alive with me today.”

Participants described their experiences of connection through the articulations of subtle sensations or qualities that supported experiences of experiential and emotional integration. For example, Lily described that she experiences the felt sense of the relationship “within my entire body…not just in my heart.” Diana noted that “the peace I carried when this person was around is the peace that comes over me”, and Buffalo Jay shared that communications from her father are experienced as “a warm hug, like a support”, through which she feels “fullness, validated, and love.” Joselyn noted she experiences “a residual experience of connection in waking life that’s just always sort of there”, and continued to share that through this experience she has “less need for things” and has “become more comfortable with the way things are and how they exist, and [she is] finding joy in that.” These subtle, felt qualities of connection expanded beyond intrapersonal and interpersonal domains to include the transpersonal through the continued bond. For example, Sharmin noted feeling “more supported by the divine, maybe through her”, in which the continuing bond facilitated a felt sense of an expanded relationship beyond the physical domain of experience.

5. Discussion

This study explored the relationship among ADC, grief resilience, and STEs. Data were drawn from two studies: a survey of four measures of grief and STEs in the general population (N = 329), and a collection of interviews (N = 44) with participants having previous experience with ADC.

Results from Study 1 confirmed that in a diverse population, higher scores in grief resilience were associated with higher scores in continuing bonds with the loved ones and self-transcendent emotion experiences, specifically compassion and transpersonal gratitude. Additionally, those claiming to have had experiences with ADC showed significantly higher scores on measures of grief resilience, continuing bonds, compassion, and transpersonal gratitude. The findings also uncovered a relationship between having a spiritual practice and after-death communication, with spiritual practice being a predictor of higher scores in grief resilience, ongoing relational bonds with the deceased, and STEs. The two phenomena of ADC and spirituality may be important collaborators in the healthy movement through grief toward a more integrated and fulfilling relationship with the deceased.

Study 2 explored the phenomenological, subjective experience of after-death communication and its relationship to moving through the grief process and association with compassion and gratitude. Findings from this study expanded the understanding of ADC as a catalyst and facilitator of grief. The ongoing bond and relationship implicit in the experience of after-death communication helped participants move through the grief process in a manner that attenuated the feelings of loss and isolation. Individuals experiencing ADC also derived personal benefits outside of the relational domain in the form of an expanded or transformed worldview that bridged the manifest world with the unseen world in a manner that was life-enhancing and integrative. Transformed spiritual beliefs and reduced death anxiety were outcomes shared by interview participants, and these are supported by the correlation between spiritual practice and higher scores on compassion and gratitude. Overall, the model of catalyzed grief reinforced the survey data and surfaced a more nuanced understanding of emotional amplification of STEs, specifically compassion and gratitude.

It may be tempting to think of after-death communication as an exceptional, or even aberrant, phenomenon that occurs under the highly emotional conditions of the loss of a loved one. This research found ADC to be a more regular and common occurrence than expected, and one that enhanced the relationship with a deceased loved one in a way that allowed grief to transform the relationship. This appeared to be true regardless of the particular form of the after-death communication, implying that it was the relational bond enhanced by the communication rather than a particular medium of communication. The benefits of using ADC to nurture grief resilience generalize into a more integrated sense of self, suggesting that resilience in grief may have additional mental health benefits. These additional mental health benefits will, of course, require further investigation.