Abstract

This paper investigates religious encounters between Chinese and Senegalese Muslims in the relatively new Chinatown of Dakar. Chinese Muslims from Kaifeng City, Henan Province first arrived in Senegal in the 1990s following the Henan provincial state-owned construction company. They started a wholesale business mainly of clothing and shoes and brought their relatives and family members to Dakar. However, scholars studying the Chinese community in Dakar have largely ignored their Muslim identity and its significance. Moving beyond the conventional focus on tensions between Muslim and Chinese identities in the study of overseas Chinese Muslims, this paper turns to religious encounters in everyday life. Based on field research and interviews both in Dakar and Henan, this paper argues that for these Chinese Muslim businesspersons in Dakar, Islam as a shared religious identity sometimes provides opportunities to connect with their fellow Muslims in a foreign country. However, differences in religious practices can also lead to misconceptions between them and other Senegalese Muslims. This paper thus contributes to Islamic studies and the study of global China, particularly in relation to overseas Chinese Muslims, China–Africa encounters, and global Chinatowns.

1. Introduction

In the last decade, with more Chinese people living in African countries where religions are widely practiced, scholars started to notice the religious dimension of China’s engagement in Africa. Mahayana Buddhism, one of the most important religions in China, has attracted much attention. Shi and Li (2023) discussed several Buddhist temples/organizations in South Africa, Tanzania, Botswana and Malawi, and investigated their entanglement with politics and transnational connections. Shi (2024) also studied the Guandi temple built by early Chinese migration in Mauritius as well as contested discourses on it in contemporary Mauritius and China. Based on her ethnographic work in the Tanhua Temple recently built in Dar es Salam, Qiu (2024) argued that resident Buddhist monks tried to cultivate Buddhist spirituality among Tanzanian locals through everyday practice and allegorical stories.

However, little attention has been paid to the growing number of Chinese Muslims in Africa, apart from a few words in the footnote of a paper on Chinese communities in Nigeria (Xiao and Liu 2021, p. 390). On Kuaishou, a popular Chinese short-video platform, a Chinese Muslim who has been sharing his life in Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire since 2019, explained to his co-religionists in China on his way to a Jumuʿa mosque (congregational mosque) in Côte d’Ivoire, “there is a rather large Muslim population in Africa, and for anyone who wants to come here, it’s easy to eat halal (Arabic, lit. permissible) food.” (Kuaishou 2022) Indeed, sub-Saharan Africa is recorded to have about 241 million Muslims in 2009 (Pew Research Center 2009) and continues to grow. In the foreseeable future, more Chinese Muslims might set foot on Africa for business opportunities and encounter their African Muslim brothers and sisters. This paper focuses on one of the earliest Chinese Muslim communities in Africa, that is, the Hui Muslims from Henan Province living in the so-called “Chinatown” of Dakar, Senegal, thus contributing to the study of China–Africa relations from the perspective of religion.

In so doing, this paper also contributes to the interdisciplinary field of Chinatown studies. Sociologist Zhou Min focused on New York’s Chinatown and argued that this ethnic enclave helped Chinese immigrants integrate into American society by providing opportunities for upward social mobility (Zhou 1992). One scholar of religion has examined Chinese popular religion in Toronto’s Chinatown, where shrines to various deities can be found in some Chinese restaurants and shops (Woo 2010). In New York, migrants who arrived from Fuzhou since the 1980s have established numerous religious communities, including Buddhist, Daoist, and Chinese popular religions as well as Protestant and Roman Catholic Christian communities (Guest 2003). Shifting the focus away from historical Chinatowns in North America, sociolinguists studied the linguistic landscape of emerging Chinatowns in a global South context, such as the theme-park style “Chinatown” (shopping and dining area) inside Dubai Mall (Gu and Song 2024), and the Thamel “Chinatown” in Kathamandu, which caters to growing Chinese tourists (Gu 2024). However, studies on Dakar’s Chinatown, as well as on Islam in Chinatown, are lacking.

This paper, therefore, also helps to fill a gap in the emerging research field of overseas Chinese Muslims, which heavily focuses on cases from Southeast Asia and the Middle East. In this field, scholars appear to be particularly interested in the identities of Chinese and/or Muslims. For example, in Dubai, Chinese-speaking Hui Muslims who arrived since the 1990s are mostly traders in the wholesale and retail business, embraced their dual identity as “Chinese” and “Muslim” (Wang 2016), and some worked as “cultural ambassadors” to promote mutual understanding and economic cooperation between China and the United Arab Emirates (Wang 2020, pp. 152–79). Similarly, in Dubai, some Hui Muslims who are familiar with Arabic and Islamic culture helped to facilitate the transcultural communication between Chinese businesspeople/teachers and Gulf locals (Armijo and Chai 2020). In Malaysia, Ngeow and Ma (2016) argued that many Hui Muslims from China maintained their Muslim and Chinese identity in a Muslim-dominant country. In Indonesia, Chinese who converted to Islam forged a translocal identity through their links with Hui Muslims in China, therefore, to reconfigure their social position in a Muslim-majority society (Hew 2014). While in North America, these Muslims often are a “double minority,” preserving both Chinese and Muslim identities (Wang 2018). These scholars also called for comparing the experiences of overseas Chinese Muslims in different countries (Wang 2016, p. 70; Ngeow and Ma 2016, p. 2126).

Such a binary identity paradigm tends to reify static, essentialized notions of ethnicity or religion, while the internal differences within Muslim communities (Whyte and Yucel 2023), as well as other factors that might influence migratory experience, such as racialization (Baldeh 2025), and economic status (Ning 2024) are downplayed. Therefore, this paper turns to the concept of “religious encounter” to examine the experiences of Chinese Muslims in Dakar. This term refers to complex and dynamic interactions between religious groups whose boundaries are unfixed. However, religion is not the only factor that plays a role in people’s relations with others, even in a religious setting. As Schielke argued that Islam alone cannot explain “the ambivalence, the inconsistencies and the openness of people’s lives that never fit into the framework of a single tradition,” and called to consider “the existential and pragmatic sensibilities of living a life in a complex and often troubling world” (Schielke 2010, p. 2). Following this trend, this paper puts the “religious encounters” into ordinary lives with “attention not only to intra-Muslim differences but also [to] how religiosity is formed and experienced through engagement and encounters with Others, whether religious, ethnic or political, both locally and globally” (Osella and Soares 2020, p. 466).

Based on field research in Dakar, Senegal (December 2022, June 2025) and Henan, China (April 2025) as well as interviews via social media (mostly WeChat), this paper explores the religious encounters between Hui Muslims from Henan and Senegalese Muslims in Dakar’s Chinatown. This paper is divided into four sections. The first section discusses the religious differences between Muslims in Kaifeng and Dakar; the second section traces the migratory trajectory of Chinese Muslims from Kaifeng, Henan to Dakar, Senegal; following that, the third section presents the setting, i.e., Dakar’s Chinatown where these religious encounters happen every day; the last section delves into the religious encounters between these two Muslim groups and tries to answer how Chinese Muslims understand the differences between themselves and Senegalese Muslims, and how these (mis)understandings translate into their everyday lives.

2. Islam in Henan and Dakar

Before discussing the religious encounters in Dakar’s Chinatown, this section introduces the Muslim communities in Henan and Dakar, with an emphasis on the differences in their religious practices. This is by no means intended to deny the unity of Islam or the spirit of Muslim brotherhood in the global ummah (Arabic, lit. community), but rather to remind people of the dynamics and diversity within the Muslim world (Manger 1999), which are often overlooked in the literature on contemporary overseas Chinese Muslims.

Muslims have been present in China since the seventh century, and today, approximately 20 million Muslims of various ethnic and linguistic backgrounds live in the country. However, Muslims throughout China have never been a monolithic community because of various geographic, economic, linguistic, and religious differences. Under the policies of the People’s Republic of China, Chinese-speaking Muslims with different dialects and ancestral origins across the country were officially identified and categorized as Hui, the largest among the ten Muslim ethnic groups in China (Gladney 1996). Henan Province has China’s third-largest Hui population, only after Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and Gansu Province. According to the latest Henan Population Census conducted in 2020, the ethnic Hui minority is the second largest ethnic group in Henan province. The Hui people, with a population of 948,553, constitute 0.95% of the total population of Henan province (Henan Provincial Bureau of Statistics Office of the Leading Group of Henan Province for the Seventh National Population Census 2022, p. 885). According to the latest account, there are about 82,300 ethnic Hui in Kaifeng, which has a population of 5.5 million (Kaifeng Government 2022), while most of the Hui people live in the Shunhe Hui District of Kaifeng. Zhuxian Town is located in Xiangfu District, a suburb of Kaifeng, and has a population of about 30,000 people. However, the number of the Hui population in Zhuxian Town is not available, but most of them live in Xi Jie (lit. West Street), next to the Zhuxian Town Mosque.

The exact origin of the Hui in Henan province is still debated. During the Mongol Yuan rule, many Muslim communities had already settled down in important transportation centers and the outskirts of cities in Henan because many of them were businesspeople traveling across the country (Hu 2005, p. 48). In Kaifeng, several Muslim enclaves were established by migrations from other parts of the country during the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1912) (Hu 2005, pp. 53–54). They started to write religious texts in Chinese, and most of the existing Chinese-style mosques were initially built at this time. During this time, religious schools exclusively for females developed in Henan and evolved into female-only mosques (Jaschok and Shui 2000). In the early twentieth century, about ten mosque-centered communities existed in downtown Kaifeng (Hu 2005, p. 128). In Zhuxian Town, Muslims first arrived from the northwest of the country in the early Ming Dynasty (1450–1457CE) and formed a considerable Muslim community in Xi Jie by the late Qing period (1862–1875CE).

Two major Islamic traditions in Kaifeng are gedimu (a term derived from Arabic, meaning “ancient”) and yihewani (a Chinese word derived from Arabic, meaning “brotherhood”). The old gedimu tradition had been the dominant or the only one in Henan before the 20th century and is also followed by most Hui Muslims in Dakar. Muslims of this tradition followed the Sunni Hanafi Islam of their ancestors and were against unorthodox innovations. During the Republic era (1912–1949), the yihewani tradition, originally inspired by the salafi movement, gradually gained popularity. This tradition was based on the Ikhwan Muslim Brotherhood in the Arab World and was first introduced into northwest China by Muslims who went abroad for hajj and study (e.g., Ma Wanfu (1849–1934) in Linxia, Gansu). These Muslim reformers were concerned with religious scripture and attacked Sufi traditions that were popular in northwest China (Gladney 1996, p. 134). Ma Guangqing returned to Kaifeng in 1917 after studying with Ma Wanfu in Qinghai and started to spread the yihewani tradition secretly. After decades of debates and conflicts with the gedimu Muslims, yihewani Muslims accounted for 20% of the Muslim population in Kaifeng around 1937 (Hu 2005, p. 134). Until today, all the 13 mosques in downtown Kaifeng belong to either of these two traditions, and Muslims of the two traditions have peacefully co-existed in spite of many differences and sometimes religious arguments over rituals and life-cycle events (Dai 2011). However, today, someone registered as a Hui by the government does not mean they are a practicing Muslim. In Kaifeng, very few young people attend the Jumuʿa prayer in the mosques on Fridays due to the high work pressure and lack of religious education (Chang 2012). Some ethnic Hui even converted to Christianity as a result of the Christian missionaries targeting Chinese Muslims (Shui 2006).

Unlike China, Senegal is a Muslim-majority country, with 97% of its population identifying as Muslim. As early as the eighth or ninth century, Muslims were present in West Africa through the trans-Saharan trade routes. By the thirteenth century, Islam had become the religion of the state of the Mali empire, but its influence was limited to religious scholars, political elites, and merchant communities. Massive conversion to Islam occurred during the colonial period when an “Islamic sphere” in French colonial West Africa emerged as a transethnic, semi-autonomous religious space facilitated by colonial economic changes, urbanization, and increased mobility (Launay and Soares 1999). This sphere allowed Africans to convert to Islam as individuals, regardless of their hereditary social roles (Launay and Soares 1999), and enabled certain Muslim leaders and heads of Sufi orders in particular to promote Islam relying on their rapport with the French colonial government (Seesemann and Soares 2009). Sufi communities in Senegal have also engaged in economic activities and gained a monopoly in certain sectors, which encouraged conversion to Islam among those seeking to participate in these sectors. For example, the Mouride tariqa (Arabic, lit. path, method) led by Amadou Bamba (1853–1927) developed their social organization to put resources into the peanut plantation economy and later became influential in the national economy (Villalón 1995). Nowadays, Sufism, the mystical Islamic tradition, including Tijaniyya, the Muridiyya tariqas, and a few smaller ones, is the dominant Islamic tradition in Senegal.

Leaders of these Sufi tariqas have left an enduring legacy in Senegal. The founder of the Muridiyya Sufi tariqa, Sheikh Amadou Bamba, known to his followers as Serigne Touba, is so important that his pictures can be found in many public spaces (Roberts et al. 2003, also see Figure 1). Sheikh Ibrahim Niasse (1900–1975), a Senegalese Muslim and the founder of the Fayḍa branch of the Tijaniyya order, today remains popular among his followers not only in Senegal but throughout the entire West African region and in the diaspora. In the Sufi order he founded, Niasse appointed and taught notable women who became religious leaders. Since 2000, women religious leaders emerged in Dakar, leading mixed-gender Muslim communities (Hill 2018), playing an even more prominent role than in Henan, which has a tradition of female mosques and schools.

Figure 1.

A Chinese-owned shop in the “Chinatown” selling pictures of leaders of Sufi orders in Senegal [It seems that these are mostly Mourides, except for the lithograph and photo of Babacar Sy to the left and the lithograph of Ahmad al-Tijani on the right]. Author. 12 December 2022.

3. From Kaifeng to Dakar: Chinese Muslims’ Migration Trajectories

The diplomatic relations between the People’s Republic of China and Senegal began in 1971. In 1983, the newly established China Henan International Cooperation Group (CHICO, or Henan Guoji), a Henan provincial state-owned civil engineering company, undertook the construction of the Stade de l’Amitié (later renamed Léopold Sédar Senghor Stadium), an aid project from the Chinese government. CHICO registered its Senegal branch in Dakar the following year and finished the stadium aid project in 1985. According to an employee of CHICO, in the next decade, the high quality of this stadium project helped the company to win various construction projects, including water wells, roads, and buildings, in Francophone West Africa (Xin 1999, pp. 176–77). These infrastructure projects brought many Chinese workers, engineers, managers, and translators to Senegal.

In 1996, the Senegal government cut its diplomatic ties with the People’s Republic of China and turned to the Republic of China based in Taiwan (ROC). But the economic connections between Senegal and China did not abruptly stop during this political interruption. CHICO and the Chinese National Fishing Company were the only two Chinese companies that remained active in Senegal. There were no projects going on in the field of development aid and official cooperation (Stamm 2006, p. 7), while imports from China increased. Between 1996 and 2005, Senegal’s total importation value from China increased from 2% to 4% (Hazard et al. 2009, p. 1565), and the quantities of tennis and basketball shoes imported from China doubled during the same period (Scheld 2007, p. 250). Senegal’s importation value from China increased dramatically after 2001, when China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) and was further embedded in the global economy (Stamm 2006, p. 6). During this period, many CHICO-related Chinese stepped into the business field in Senegal. In 1996, Yan Jun (pseudonym), who claimed to be the seventh Chinese person to settle down in Dakar, opened the Dongjing Restaurant and named it after his hometown Kaifeng, which once was the east capital (dongjing in Chinese) of Northern Song Dynasty (around CE960–1127) in Chinese history (He 2017). Li Ning, a Hui Muslim from downtown Kaifeng, arrived in Dakar in 1999 as an entrepreneur and has invested in restaurants, Chinese medicine clinics, and trade (Wu 2022).

The reason that these Chinese people came to Senegal has particular social and economic contexts. In 1992, Deng Xiaoping toured southern China, during which the former leader reconfirmed the support for the market economy and “reform and opening-up” policies in China. Also, in the face of increasing pressure as a result of ongoing bureaucratic reform, many civil servants, employees of state-owned enterprises, and teachers resigned from their government-paid jobs to become “cadre entrepreneurs” (xiahai in Chinese, literally means jumping into the sea) (Gong 1996). Some employees at CHICO in Dakar were influenced by this trend and decided to explore the business opportunities in Senegal, especially when they saw that competitive made-in-China consumer goods were imported and sold on the market by Senegalese traders in the 1990s (Cissé 2017, p. 47). Some of them chose to remain in Senegal after their temporary contract with CHICO (Kernen and Vulliet 2008, p. 73) and used their stronger connections and language skills in China to compete with Senegalese merchants on the market (Cissé 2017, p. 47). CHICO also invited “cadre entrepreneurs” back in Kaifeng to explore business opportunities in Dakar (Interview, 22 April 2025). Roman Dittgen even suggested that CHICO was a “Trojan Horse” in Senegal because it provided work permits to help migrants arriving in Senegal from Henan between 1996 and 2005 (Dittgen 2010, p. 6).

In these migration trajectories, family ties and kin connections played an important role. In 2001, the Chinese government lifted the restrictions on passport applications for most citizens (G. Liu 2009), which means that more people can follow their relatives and friends to earn a living abroad. In a documentary film streamed on Al Jazeera English in 2010, one lady running a Chinese restaurant in Dakar said that “my family members had been doing business here for years, and they told me the weather was nice, so I came here. 17 members of my large family are all here now,” and she continued that “there is less competition in Africa than in China, which means it is easier to make money here…when a Chinese person becomes successful, he helps family members move over.” (Huffman and Zhou 2010). Another man also emphasized the benefits of having his relatives around, “during the first couple of weeks (after my arrival), I was afraid to go outside. All I saw was black skin, and I was a little scared. [laughing] Now, with all my relatives here, I don’t feel so lonely. We get together, like back home. You don’t feel hard and bored, and we take care of each other.” (Huffman and Zhou 2010). The success story of friends also encouraged people who had no prior experience in the trade to explore the opportunity in Senegal (Cissé 2017, p. 47). Family trust also helps in running a business in Dakar. For example, a Chinese lady from Kaifeng owns seven shops in Chinatown, all run by her family members (Cissé 2017, p. 48).

Through such connections, Hui Muslim from Kaifeng arrived at Dakar. Li Ning and his family were among the earliest arrivals from downtown Kaifeng. In 2002, a Hui Muslim from Zhuxian Town followed his brother-in-law from downtown to do business in Dakar. Since then, more Muslims from Zhuxian Town have arrived in Dakar, initially working in relatives’ or friends’ shops for two to three years before establishing their own businesses. Zhuxian Town, located approximately 30 minutes’ drive south of downtown Kaifeng, was historically one of China’s four most renowned commercial towns (in addition to Hankou, Foshan, and Jingdezhen) during the Ming and Qing dynasties thanks to its strategic location connecting water and land transportation. During this time, a large group of Muslim merchants from the northwest of the country involved in horse, fur and other forms of trade settled in Zhuxian Town (Li 2004). In some ways, Hui Muslims in Dakar are continuing and reviving their ancestors’ centuries-old tradition of migrating for business.

This group of Hui Muslims from Zhuxian Town gradually replaced the Hui Muslims from downtown Kaifeng and came to dominate the small commodity trade in Dakar, particularly in clothing and accessories. Those from downtown Kaifeng who remained in Dakar focused primarily on selling shoes. This shift was interpreted in different ways. For the Muslims from downtown, who considered themselves better educated, the move away from low-end trade was seen as a natural progression toward more profitable business ventures. In contrast, for many Muslims from Zhuxian Town, it was a story of hard-earned success by outcompeting their urban counterparts and capturing the market through collective and individual efforts (Interview, 22 April 2025).

Most Hui Muslims from Henan came to Dakar to do business and earn money. After more than 20 years, some of these Hui Muslims have returned to China for retirement, leaving their shops to their descendants. Some also have begun exploring opportunities in neighboring countries, including but not limited to Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire (Interview, 14 June 2025). Currently, some Chinese have raised their children in Dakar, where I have seen Chinese and Senegalese children playing together on the street (Fieldnotes, 11 December 2022).

4. The Formation of Dakar’s Chinatown or “Henan Street”

In comparison with Chinatowns elsewhere, this section examines three dimensions of Dakar’s Chinatown: (1) the transformation of the urban landscape, (2) the contested discourses surrounding “Chinatown” within Chinese communities, and (3) its often-overlooked Muslim background revealed through linguistic and semiotic landscapes.

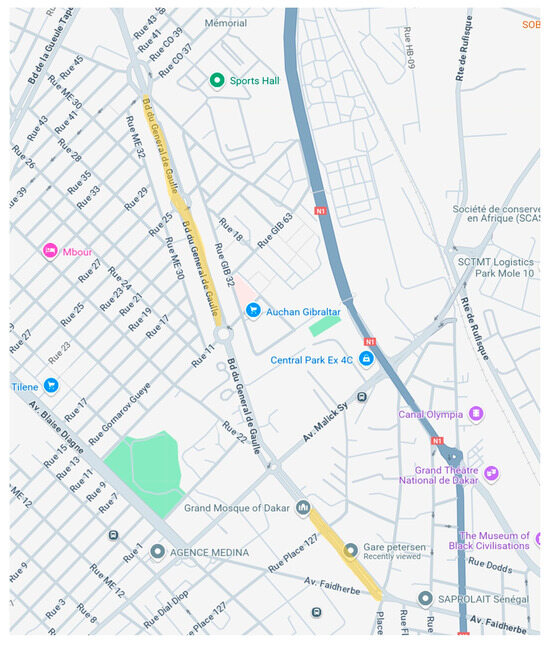

Chinese-owned shops in Dakar initially were concentrated around the Gare Petersen (see Figure 2). Chinese owned more than 90% of the shops in this small commercial center designed for Senegalese vendors (Scheld 2010, p. 153, see Figure 3). They later expanded to the nearby area of Centenaire (Boulevard Général Charles de Gaulle, commonly known as “Allées du Centenaire”, see Figure 4), which earned its name of Chinatown or “Henan Street”. The emergence of Dakar’s Chinatown is embedded in the political economy of the host country and is the result of organically growing Chinese shops, rather than a deliberately designed space as seen in the Dubai Mall (Gu and Song 2024), Costa Rica (Monica 2015), and Lagos (S. Liu 2019).

Figure 2.

A map of Dakar highlighting Gare Petersen (lower) and Boulevard Général Charles de Gaulle/Allées du Centenaire (upper). Google Maps. 26 June 2025.

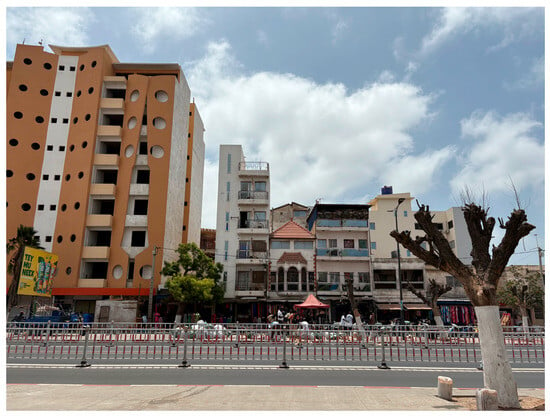

Figure 3.

A street view of Gare Petersen, with Chinese shops concentrated on the left side. Author. 11 June 2025.

Figure 4.

A street view of Boulevard Général Charles de Gaulle/Allées du Centenaire, with Chinese shops on both sides. Some Chinese also live on the second floors of these shops. Author. 14 June 2025.

This Centenaire area was designed as a residential zone for Senegalese civil servants in the newly independent country. However, in the 1990s, many of its original residents either passed away or retired, leaving financial issues with their descendants who were struck by the devaluation of CFA in 1994 (Dittgen 2010, p. 5). Therefore, renting out parts of their houses to the incoming Chinese traders became a viable way to increase their income. One local resident interviewed said, “My father never wanted to rent the garage to the Chinese traders. After his death, our family had a lot of social issues; therefore, we were obliged to rent our garage to have incomes to support ourselves.” (Cissé 2013a). Chinese traders turned garages annexed to the houses into shops and warehouses and attracted clients from other regions in Senegal and neighboring countries, including Mali and Guinea. Chinese businesspeople not only ran nearly 300 wholesale shops but also opened hotels, hair salons, restaurants, supermarkets, logistics companies, and travel agencies along the boulevard to serve the growing Chinese community in the city.

The total number of Chinese in Senegal is hard to calculate, and the estimations vary significantly between 2000 and 10,000 (Marfaing and Thiel 2014, pp. 407–8). In Centenaire, scholars counted 223 Chinese-owned shops in 2013 (Marfaing and Thiel 2014, p. 408). Within this Chinese community, 50–60% are originally from Henan Province, as estimated in 2007 (Kernen and Vulliet 2008, p. 73). Most Chinese traders interviewed by Cissé in 2012 were from Henan Province, and more than 60% of the total Chinese community in Dakar is from Henan (Cissé 2013b). Cissé also noted that the majority of Chinese traders in Centenaire came from Kaifeng (Cissé 2013a). Following those Chinese shops, many Senegalese youths from rural areas set up table stalls occupying the pavement of the boulevard, which further transformed the Centenaire from a bourgeois residential community into a bustling commercial district (Diop 2009).

Unlike many other Chinatowns around the world, Dakar’s Chinatown features no iconic Chinese-style decorations and architecture (Stevens and Thai 2024; Lai 1997). Instead, it looks like an ordinary commercial street lined with shops selling clothing, accessories, and groceries. Most of these shops—except for a handful of Chinese restaurants and supermarkets—display no signage, let alone signs in Chinese. This is likely because the wholesale business in Dakar’s Chinatown caters exclusively to African customers who are familiar with the area rather than to Chinese tourists or residents, as is the case in Paris (Zhao 2021), Dubai’s Dragon Mall (Gu 2023), or Bangkok (Pan 2025). Another possible reason for the limited use of Chinese-language signs is that it helps maintain a low profile in order to avoid provoking negative sentiments that have led to protests against Chinese wholesale businesses in Senegal in 2004 (Dittgen 2010).

Despite its lack of recognizable visual characteristics, Dakar’s Chinatown has caught the attention of journalists (Fitzsimmons 2008), filmmakers (Huffman and Zhou 2010), artists (Raw Material Company 2012), and even tourist visitors from the United States (Makmuri 2012), earning the label “Chinatown” among a broad audience. However, the Chinese community does not refer to this area as tangren jie, zhongguo cheng, or huaren jie, which are commonly used Chinese translations for Chinatown. Instead, many Chinese I met during fieldwork referred to Allées du Centenaire as Henan jie (Henan Street), reflecting the dominant presence of Henan people in that area. For some of my interlocutors from Henan, this name Henan jie originally had a negative connotation in the early 2000s (Interview, 22 April 2025) when there was a boom of stigmatization or regional discrimination against Henan people in China (Yue 2012). Today, the “Henan Street” appears to be a neutral term among my Chinese interlocutors, but it still challenges the broader discourse, usually from non-Chinese, of representing Allées du Centenaire as a Chinatown.

This discursive contestation does not arise from nowhere. In fact, many Chinese in Dakar neither live nor work on Allées du Centenaire. The Chinese embassy, along with most Chinese state-owned enterprises, has opted to settle in the more affluent Almadies area. One of the most popular Chinese restaurants, Restaurant chinois La mer ouest (West Sea Chinese Restaurant), is also located in this neighborhood. Furthermore, individuals from Henan Province are notably underrepresented in Chinatowns globally. Compared to certain coastal provinces such as Guangdong, Fujian, and Zhejiang, Henan Province, located in central China, does not have a well-established tradition or network for overseas migration or international business. Nor is the province known for producing consumer goods sold in the Senegalese market. In fact, most of the businesspeople imported their goods from Yiwu, a city in Zhejiang specialized in the trade of small commodities (Interview, 21 April 2025).

This contestation highlights the internal diversity of the overseas Chinese community. A similar dynamic has been observed in the construction of Chinatown in Costa Rica, where Chinese communities from different backgrounds held opposing views on the project (Monica 2015). In the Nigerian context, Xiao and Liu (2021) proposed a non-essentialist concept of “discursive ethnicities” to understand the overseas Chinese, emphasizing roles of interactional subethnicity, self-ethnicity, and other-ethnicity. In this paper, the contesting discourses surrounding Chinatown/Henan Jie illustrate the diversity and instability of the “Chinese” ethnic category, as many non-Henan individuals challenge the labeling of Allées du Centenaire as Dakar’s Chinatown. For the Henan people—most of whom are from Kaifeng—their shared place of origin, migration trajectory, as well as family and business networks, contribute to a collective subethnicity. However, competition between people from downtown Kaifeng and Zhuxian Town, sometimes further fragments their subethnicity.

Islam also helped to shape this Henan community’s subethnicity. However, none of the existing literature on Chinese business persons along the Centenaire has mentioned their Hui Muslim background. Some of my interviewees estimated a few hundred Hui Muslims in Dakar. One interviewee counted 200–300 people from Zhuxian Town currently living in Dakar (Interview, 21 May 2025). Hui Muslims from other regions are also arriving in Dakar through their connections with Hui Muslims from Kaifeng. For example, I met a young male employee—a Hui from Luoyang (another major city in Henan)—working in a shop owned by a Kaifeng Hui Muslim (Fieldnotes, 12 December 2022).

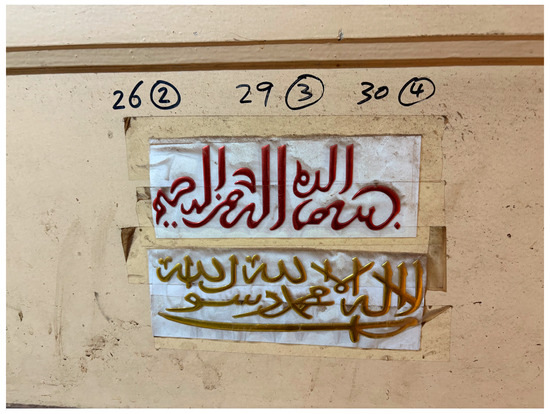

A closer examination of the linguistic and semiotic landscape of Dakar’s Chinatown helps to revel its Muslim background. Many of these shops sell modest clothing or hijabs for Muslim women on the east side of the road. In the picture below, the shop is branded as “Mohamed Pan,” a Muslim first name and Chinese family name indicating his Chinese Muslim background (Figure 5). On Google Maps, a Chinese hair salon was named after “Ayisha,” which clearly is a Muslim female name. One family who originally came to Dakar as businesspeople opened a halal restaurant serving Henan food in 2021 (Fieldnotes, 11 December 2022), and their menu below has a green label in the upper right-hand corner reading qingzhen (lit. pure and true) in Chinese and taʿām almuslimīn (lit. food of the Muslims) in Arabic, which advertises the restaurant as a halal one (Figure 6). Another Henan restaurant, “Yuyuan,” opened in 2024 in an alley off Centenaire Street, has attracted many customers from Zhuxian Town. In this small restaurant, two plaques featuring the Arabic basmala (“In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful”) are placed above the door frame of the halal Henan restaurant. Inside the restaurant, alongside Chinese painting decorations, a larger plaque displaying the shahada (“There is no god but God, Muhammad is the Messenger of God”) and Quranic verse (2:255)1 is mounted on the wall (Figure 7). Similarly, inside a Chinese shop, a small plaque with the Arabic basmala and shahada is affixed to the door of the garage room (Figure 8).

Figure 5.

A clothing shop owned by a Chinese Muslim. Author. 12 December 2022.

Figure 6.

The Chinese menu of the halal Henan Restaurant in Dakar. Author. 11 December 2022.

Figure 7.

Yuyuan Restaurant. Author. 11 June 2025.

Figure 8.

Plaques with Arabic baslama and shahada inside a Chinese shop. The upper one has a distinctive Chinese style (Sini) Arabic calligraphy. Author. 11 June 2025.

It is important to note that Dakar’s so-called Chinatown is not an ethnic enclave reserved for Chinese people, but rather a space of encounter where mostly Hui Muslims from Henan interact with Senegalese Muslims. For these Henan people doing business with Senegalese every day, they have acquired fluent colloquial Wolof (the lingua franca) and French (the official language), at least in the business context. During my stay at some Chinese-owned shops, Wolof was the major commercial language between local customers and Chinese businesspeople (Fieldnotes, 14 June 2025). Most Hui Muslims from Zhuxian Town do not have university-level education and initially had to rely on Chinese characters to mark the pronunciations of French and Wolof words so as to learn Wolof and French for communicating with their local clients in everyday life (Interview, 21 April 2025). On an interior wall of a Chinese shop on the Centenaire, Fiona McLaughlin recorded a handwritten list of Chinese words with their translation into French or Wolof, written phonetically in Chinese characters (McLaughlin 2023, pp. 434–35), which is believed to help Chinese businesspeople to communicate with their customers. Nowadays, some of the younger ones have even grown up in Dakar, acquiring near-native proficiency in Wolof and French through their schooling there (Fieldnotes, 14 June 2025).

Henan people’s language skills helped to facilitate their encounters with locals who are their business partners, clients, landlords, as well as young migrant workers from neighboring countries such as Guinea (Seck 2014, p. 138). Sometimes, the relationship between Senegalese street vendors and Chinese shopkeepers can be intensive (Interview, 21 April 2025). But I also witnessed a Senegalese street vendor sitting in the shop and chatting casually with the Chinese shopkeeper (Fieldnotes, 11 December 2022), a scene that supports the friendly relationships observed by other scholars (Scheld and Siu 2014, p. 173). Scheld and Siu (2014, p. 160) also pointed out the presence of “veiled racism” in Dakar’s Chinatown, noting that under “smiles and superficial acts of kindness,” the Chinese often held racist attitudes toward Senegalese, while Senegalese expressed xenophobic sentiments. It is in this setting that religious connections and misunderstandings have played an important role in shaping Chinese Hui Muslims’ perceptions of local Muslims.

5. Religious Encounters Between Chinese and Senegalese Muslims

Chinese Muslims came to Dakar for business purposes rather than religion. Most of them, therefore, focused much more on their business prosperity than on religious practice. But this does not mean that Chinese Hui Muslims have refrained from any religious practices and activities. This section presents several cases of religious affinity and contestations between Chinese and Senegalese Muslims.

5.1. Religious Affinity with Limited Knowledge

At first glance, many Senegalese Muslims usually do not recognize these Chinese as Muslims. However, Islamic greetings and Muslim names have helped some Chinese Hui Muslims to be recognized by their Senegalese counterparts as fellow Muslims. Some interviewees prefer to use their Quranic name (“jingming”, usually an Arabic name from the Quran) in everyday life, which is much easier to remember and pronounce than most Chinese names. According to my interlocutors, many Senegalese were surprised to realize that there are Muslims in China as well.

Once such a religious identity is confirmed, religious activities, especially Eid al-Adha (Arabic, lit. Feast of Sacrifice), become an important occasion for strengthening mutual relationships. One Chinese interviewee told me that their acquaintances were surprised to learn that they have a Muslim name and were born into a Muslim family, and subsequently adopted a more positive attitude toward them. The interviewee added that their landlord was happy to share a big lamb leg with his Chinese Muslim brother and sister during Eid al-Adha (Fieldnotes, 12 December 2022). Similarly, one interviewee was invited to their employee’s house in suburban Dakar almost every year to observe Eid al-Adha together (Fieldnotes, 15 June 2025). Such generosity also came from Chinese Muslims. Another interviewee, who had attained some wealth in Dakar, actively shared meat with friends and neighbors during each Eid al-Adha because they believed that this practice could foster a sense of affinity, leading Senegalese Muslims to perceive Hui Muslims as “zijiren” (people of shared blood), which might alleviate potential hostility towards Chinese business owners (Interview, 22 March 2025).

For some Hui Muslims, especially newcomers, their religious identity can occasionally help them avoid certain troubles. One interviewee who arrived in Dakar just a few years ago recounted that, on one occasion, a traffic police officer stopped him on the road. He asked the officer for leniency, emphasizing that they were both Muslims. The officer did not believe he was Muslim, so he recited Surah al-Fatiha (Arabic, lit. The Opening Chapter) from the Quran to prove his religious identity. Eventually, the officer was happily surprised and let him leave without a ticket (Fieldnotes, 10 June 2025). Another interviewee shared a similar story from many years ago, but added that today, the police no longer care and they will issue the ticket regardless (Fieldnotes, 14 June 2025).

However, Islamic ethics and networks do not play an important role in Hui Muslims’ business practices in Dakar. Unlike African Muslim small-business traders in Guangzhou, who have created informal social welfare systems by engaging in Islamic charity (Jiang 2022) and applying faith-based business ethics to navigate daily challenges (Jiang 2023), Hui Muslims in Dakar tend to separate religion from commerce. They do not rely on religious ethics or networks to facilitate their business activities. Sometimes Chinese businesspeople take advantage of specific religious holidays, such as Eid al-Fitr (lit. Festival of Breaking the Fast), Eid al-Adha, and the Magal of Touba (a Mouride religious event) to promote their products and boost sales (Dittgen 2010, p. 8). But even this practice has been declining as more Senegalese consumers can now afford to buy new clothes year-around, rather than only during special holidays.

Moreover, Chinese Hui Muslims’ knowledge of Islam in Senegal is limited. One interviewee praised the peacefulness of Senegalese society and attributed it to their “good religious standing” (in Chinese, xinyang hao), yet had never heard of Amadou Bamba or the Sufi traditions central to Islam in Senegal (Fieldnotes, 10 June 2025). Those who have lived in Senegal for longer periods have gradually learned more about Sufi Islam from their employees and clients. In one shop I visited, a sticker of Ibrahim Niasse had been placed on the wall by local staff.

Still, Chinese Hui Muslims tend to interpret these Sufi leaders through their own religious lens, referring to them as ahong—a term derived from the Persian word Akhund, commonly used in Chinese to denote contemporary Muslim religious teachers or scholars (Fieldnotes, 14 June 2025). However, their understanding of the lives and significance of these Sufi leaders remains rather superficial. When mentioning the Chinese-owned shop selling portraits of Senegalese Muslim leaders, one Hui Muslim shopkeeper from Kaifeng questioned Senegalese Muslims for “praying toward” pictures and said that, as a Muslim, he would never do that (Fieldnotes, 12 December 2022). He understood that idol worshipping is forbidden in Islam. However, he missed the point that the pictures and visual artistic expressions of Amadou Bamba and other Sufi religious leaders are not worshipped by Muslims in Senegal. They represent these spiritual leaders’ blessings and are like a visual form of zikr (lit. remembrance, in the Sufi tradition, it means phrases or prayers are repeatedly recited for remembering God) that provides spiritual help for their disciples (Roberts and Roberts 2007).

5.2. Eating Halal/Qingzhen

Eating halal, or qingzhen (清真), especially avoid consuming any pork and pork products, is a significant marker of religious identity for Chinese Hui Muslims, who live among pork-consuming Han Chinese. The access to halal food is a common concern in Hui Muslims’ everyday lives. In China, they typically only purchase meat or eat out in halal or qingzhen shops and restaurants, which are usually certified and regulated by the government authorities (Sai and Fischer 2015). Chinese Hui Muslims have carried this tradition with them to Senegal. One Muslim interviewee, though not from Henan province, told me that they rejected a Senegalese chef who had previously cooked pork and washed dishes for other Chinese companies (Fieldnotes, 10 June 2025). Most Hui Muslims from Henan province did not adhere to such strict rules, but the foodway in Senegal nonetheless challenged their qingzhen lifestyle as one interviewee told me, “Senegalese Muslims don’t care as much about eating halal (as we do)” (Interview, 21 April 2025).

Most Chinese Hui Muslims I interviewed in Dakar prefer to cook at home to ensure their food is religiously acceptable and economically affordable. However, the first challenge many Hui Muslims face is finding halal meat. Unlike in China where qingzhen-certificated butcher shops are often located near mosques, most shops and restaurants in Dakar do not display halal markers, possibly because all meat is assumed to be halal in this Muslim majority country and due to the absence of an official authority issuing halal certifications. Many interlocutors expressed dissatisfaction with meat sold in middle-class supermarkets such as Auchan, for various reasons. One interviewee explained that at Auchan (a French supermarket chain), pork is sold right next to beef and lamb, and is handled by the same salesperson, which in his opinion is not qingzhen. (In fact, many Senegalese Muslims would not purchase meat at Auchan for similar reasons.) He also noted that the meat sold at Auchan and other similar supermarkets is not fresh and is too expensive (Fieldnotes, 13 June 2025). Instead, he and many other Hui Muslims from Kaifeng prefer to buy fresh meat either from the informal sheep market on Rue Cinq in the Medina area or from a slaughterhouse in suburban Dakar (Fieldnotes, 14 June 2025). As one interviewee assured me, “Most people here are Muslims, and they know how to slaughter in a halal way” (Fieldnotes, 14 June 2025).

Dining out posed another challenge for Chinese Hui Muslims. Among the many Chinese restaurants in Dakar, only the two Henan restaurants mentioned earlier refrained from serving pork dishes. However, Henan Fandian (Henan Restaurant), which opened several years ago, did not earn the trust of Hui Muslims from Henan. According to my interlocutors, the restaurant’s owner and chef are not Hui Muslims, even though they promised to prepare their food in a qingzhen style. As a result, the majority of Hui Muslims from Henan chose not to eat at this restaurant at all (Fieldnotes, 13 and 14 June 2025). In contrast, Yuyuan Restaurant, which opened last year, is widely regarded as a proper qingzhen Henan restaurant, featuring the culinary style of Zhuxian Town. Several interlocutors invited me to dine there and try what they described as truly qingzhen Henan cuisine (Fieldnotes, 11 and 13 June 2025).

For Chinese Hui Muslims in Dakar, local Senegalese food is generally a less favorable option. One interviewee, when choosing to eat out, preferred Lebanese, Moroccan, or European “high-end” restaurants, believing that local food was not clean or hygienic (Fieldnotes, 10 June 2025). Another Hui Muslim shopkeeper expressed a similar opinion (Fieldnotes, 14 June 2025). However, such an attitude did not stem from religious concerns. Rather, for these shopkeepers who sit all day in their street-side shops, they have observed how local vendors prepare and sell dishes, such as Thieboudienne (rice and fish), on the street, which they perceived as unclean and unsanitary (Fieldnotes, 14 June 2025). This food preference may also be linked to the economic and social status of Chinese businesspeople, who seek to distinguish themselves from street food consumers, typically street retailers and manual laborers involved in transporting goods.

Local Muslims’ abstinence from alcohol and cigarettes caught the attention of Chinese Hui Muslims and may have a transformative potential. For many Hui Muslims, such habits of drinking and smoking are part of their social life towards success. One interviewee explained to me that due to peer pressure at social events, they felt compelled to drink alcohol in order to build relationships and secure business opportunities with non-Muslim Chinese (Fieldnotes, 10 June 2025). One interviewee observed that, for Senegalese and Arab Muslims, abstaining from alcohol is the most important religious taboo. This individual even argued with fellow Hui Muslims from Henan, who described themselves to be “good in religion” (jiaomen hao, meaning devout and observant of Islamic norms), and urged them to stop drinking (Interviews, 22 April 2025).

5.3. The Quality and Quantity of Prayers

As mentioned earlier, Hui Muslims from Henan came to Dakar primarily for business rather than religious purposes. As a result, many do not regularly participate in daily or even Friday prayers. One interviewee told me that business takes priority (Fieldnotes, 11 December 2022), while another explained that he plans to devote more time to religion after retirement, but for now remains focused on work (Interview, 21 April 2025). A younger interviewee said they do not fast during Ramadan because it is the busiest time of the year, and they must work all day (WeChat Message, 21 April 2023).

In contrast, Senegalese Muslims devote considerable time to religious practice. On workdays, many perform their daily prayers on a prayer mat laid out on the street or in a room. On Fridays, they often leave the Chinese-owned shops where they work to attend Friday prayers at the mosque. During Eid celebrations, many take several days or even one to two weeks off to travel long distances and reunite with their families.

One non-Muslim merchant I met at the Henan Restaurant told me that he had traveled extensively across Francophone West Africa and found that many Muslims in Africa are “fake pious.” He explained that although they pray regularly and with apparent devotion, they do not work hard in their daily life (Fieldnotes, 12 December 2022). Unfortunately, this derogatory perception of Africans as being lazy is common among Chinese communities in Africa (Scheld and Siu 2014, pp. 173–75; Sautman and Yan 2016). Ironically, the Mouridiyya tariqa in Senegal particularly emphasizes hard work as an essential religious value (O’Brien 1971).

However, Chinese Hui Muslims tend to interpret Senegalese Muslims’ religiosity in a more nuanced way: the quality vs. the quantity of prayers. More than one interlocutor compared the prayer practice of Chinese and Senegalese Muslims. While they acknowledged that Senegalese Muslims pray more regularly, they felt the practice was less serious (Interview, 21 April 2025; Fieldnotes, 14 June 2025). A Chinese businessperson who had received religious education in Henan explained that many Senegalese Muslims often did their wuduʾ (partial ablutions) using a small plastic water sachet sold on the street and finished their prayers hastily, and that many of them do not wear a cap during prayers. According to this interlocutor, Hui Muslims emphasize the quality of prayers, always wearing proper attire, and taking more time (Fieldnotes, 14 June 2025). Indeed, cap-wearing is an important identity marker. Most Hui Muslims wear white caps, while the Jews in Kaifeng traditionally wear blue caps. As a result, Hui Muslims became known as baimao huihui (white-cap Muslim), while Kaifeng Jews were mistakenly called lanmao huihui (blue-cap Muslim) (Leslie 1972).

For Hui Muslims, observing fellow Muslims heading to the mosque can also influence their own religiosity. One interviewee shared that he sometimes felt the social pressure to attend Friday prayers alongside local Muslims and believed that doing so would bring blessings from God in both this life and the afterlife (Fieldnotes, 10 June 2025). Another interviewee, who self-identified as Hui but was not a devout practicing Muslim, shared that seeing Senegalese children walking to the mosque for religious education evoked childhood memories of studying in a mosque. However, the interviewee expressed regret at no longer remembering much Arabic or the Qur’an. Motivated by this, the interviewee once visited a mosque in Dakar to explore whether any suitable courses were available to relearn Qur’anic Arabic, but were unsuccessful in finding one (Fieldnotes, 12 December 2022).

5.4. Discussion

This religious encounter between Chinese and Senegalese Muslims involved intra-religious differences with intersecting factors such as socio-economic status and racial dynamics. Unlike religious scholars or missionaries, most Chinese Hui Muslims arrived in Dakar primarily for business, with little interest in religious activities. Yet, in everyday spaces, particularly along the Centenaire Street (Dakar’s Chinatown), they found themselves interacting with Senegalese Muslims in multiple ways: as customers, business partners, neighbors, and more. These unplanned, everyday interactions were facilitated by a sense of religious affinity rooted in the shared Muslim identity. However, at the same time, they also encountered significant religious differences, which sometimes were amplified by different socio-economic and racial positionings. These encounters also prompted reflections among some Hui Muslims, who, for example, began to question their own community’s habitual consumption of alcohol (Interview, 22 April 2025). In this way, the encounters have the potential to transform Hui Muslims’ religious lives.

Such religious encounters are unlikely to lead to religious conversions, as most Chinese Hui Muslims maintain a strong attachment to their Chinese roots. For example, some distance themselves from local Muslims by following the Islamic calendar used in China (see Figure 9). For Muslims, when to celebrate Eid al-Fitr at the end of Ramadan depends on sighting the moon. In 2023, one Chinese Muslim I chatted with online followed the Eid date in China, which was one day later than the date in Senegal (WeChat Message, 21 April 2023), which shows that they still have a stronger connection with families and the Muslim community in China than in Senegal.

Figure 9.

A Chinese Islamic calendar used by a Hui Muslim family in Dakar. Author. 10 June 2025.

In his approach to “Islam as discursive tradition,” Talal Asad (1986) argues that Islam is a discursive tradition, grounded in foundational texts such as the Quran and hadith. In any specific context, different discourses compete to instruct Muslims’ practices by relating to the founding texts. Drawing on Foucault’s concept of knowledge-power dynamics, Asad further notes that the discourse closest to power is most likely to become the orthodox one. In the context of the religious encounters explored in this paper, certain religious practices, particularly the consumption of halal/qingzhen food, are not only linked to scriptural sources but also shaped by personal tastes and embodied experiences of ordinary Muslims (e.g., Schielke 2010; Reinhart 2020).

Moreover, the power dynamics in this contest are especially complex. While the Chinese businesspeople often occupy higher social and economic positions than their Senegalese counterparts, they remain vulnerable as migrants, subject to the laws and regulations of Senegalese authorities. Within the Chinese Hui Muslim community itself, factors such as place of origin, family ties, and business competition further complicate their social relationships. In the religious field, both affinity and contestation coexist; however, these discursive contestations are unlikely to result in the establishment of an orthodoxy regulating the Chinese Hui Muslim community in Dakar. The absence of authoritative religious institutions or figures on site further amplifies the role of individual interpretation and embodied experience in shaping religious encounters.

Apart from engaging with the anthropology of Islam, this paper also contributes to the emerging field of “global Islam” (Green 2016). Historian Nile Green defines “global Islam” as “the multiple versions of Islam propagated across geographical, political, and ethno-linguistic boundaries by religious activists, organizations, and states in the age of modern globalization” (Green 2020, p. 6). However, the religious encounters between Chinese and Senegalese Muslims examined in this paper—though clearly global and Islamic—do not fully align with Green’s relatively narrow definition, as they lack identifiable religious agents actively promoting specific doctrines or practices. This paper therefore calls for a broader conceptualization of “global Islam,” one that includes spontaneous, unstructured encounters between Muslims from diverse backgrounds.

6. Conclusions

This paper has focused on the religious encounters between Chinese and Senegalese Muslims in Dakar’s so-called Chinatown. Hui Muslims from Kaifeng, Henan Province, have arrived in Dakar since the late 1990s and have transformed the urban landscape in Dakar through their business activities. However, their religious life and encounters have escaped scholarly attention. This paper argues that for these Chinese Muslim businesspeople in Dakar, Islam, the common religion shared by them and Senegalese Muslims, brought opportunities to cultivate a sense of affinity with their Muslim brothers and sisters in a foreign country. But the differences in religious beliefs and practices also have the potential to generate misconceptions and rifts between them and other Senegalese Muslims. These encounters carry the potential to reshape the religiosity of Chinese Muslims themselves.

This paper contributes to Islamic studies in two key ways. First, within the anthropology of Islam, it engages with Talal Asad’s concept of “Islam as a discursive tradition,” while also responding to calls by other scholars to pay greater attention to the role of embodied experience in shaping Muslim religiosity. Second, it challenges Nile Green’s relatively narrow definition of “global Islam” by advocating for the inclusion of spontaneous and unstructured encounters between Muslims from different backgrounds.

In the field of global China studies, this paper offers a unique and often overlooked case of a Chinatown, foregrounding the discursive contestations surrounding its Chineseness and highlighting its Muslim dimensions through linguistic and semiotic landscapes. Based on preliminary research, this study provides only a glimpse into the lives of the Hui Muslims in Dakar and calls for further research into this intra-religious encounter from the perspective of Senegalese Muslims. More broadly, this paper calls for more attention to the religious dimension in China–African relations and to the intra-religious encounters in the study of overseas Chinese Muslims:

First, in the field of China–Africa relations, China’s engagement in Africa involves not only infrastructure and trade but also people-to-people communication and interaction, within which religion plays an important yet underexplored role. As Chinese communities grow across various African countries, individuals from diverse religious backgrounds—including but not limited to Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, and folk religions—are likely to transform the religious landscape in Africa, while simultaneously undergoing self-transformation through everyday religious encounters.

Second, in a globalized world where Muslims travel around the world more frequently, the diversity and internal dynamics within the so-called “Muslim world” have become more visible and important in cultivating mutual understandings. However, variations in Islamic practice and their potential implications have received limited attention from scholars studying overseas Chinese Muslims. Acknowledging internal diversity and dynamics is the first step toward achieving mutual understandings, which, importantly, requires efforts, curiosity, and open-mindedness from those involved in everyday religious encounters.

Funding

The research was made possible by funding for the trip to Dakar in 2022 from the Center for Global Islamic Studies at University of Florida and Professor Benjamin Soares’ grant “Islam and Africa in Global Context” from the Henry Luce Foundation’s Initiative on Religion in International Affairs. The trips to Henan and Dakar in 2025 was supported by Shanghai Normal University. Additional support was provided by the Hong Kong Research Council CRF Project “Infrastructures of Faith: Religious Mobilities on the Belt and Road [BRINFAITH]” (RGC CRF HKU C7052-18G).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was determined to be exempt from formal Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval under the provisions of 45 CFR §46.104(d)(2). The research involved only interactions through survey procedures, interview procedures, or the observation of public behavior, and met the criteria for exemption as defined by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Specifically, the information obtained was recorded in such a manner that the identity of the human subjects could not readily be ascertained, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects; and any disclosure of responses outside the research would not reasonably place subjects at risk of criminal or civil liability, or cause damage to their financial standing, employability, educational advancement, or reputation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author on request.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all my interlocutors who welcomed me and generously shared their lives and views with me. I am especially grateful to Yifan Mia Yang for bringing this community to my attention in 2018. The writing of this essay benefited greatly from Macodou Fall, who patiently answered my endless questions about Islam in Senegal, and from Benjamin Soares, whose constructive feedback was invaluable. An earlier version of this paper was presented at Global China in a Religious World: BRINFAITH International Conference (HKU, Hong Kong SAR, 2023) and at Africa-Asia: A New Axis of Knowledge 3, a Conference-Festival (Dakar, Senegal, 2025). I am thankful to Shobana Shankar for inviting me to the panel at Dakar and to all those who offered insightful questions and suggestions during the conferences. I also appreciate the thoughtful comments from two anonymous reviewers. Responsibility for any remaining errors is mine alone.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | This is Ayat al-Kursi, one of the most famous verses of the Quran, also known as the Throne Verse. Reciting this verse is believed to affirm the greatness of God and to offer protection against the evil eyes. |

References

- Armijo, Jacqueline, and Shaojin Chai. 2020. Chinese Muslim Diaspora Communities and the Role of International Islamic Education Networks: A Case Study of Dubai. In Chinese Religions Going Global. Edited by Nanlai Cao, Giuseppe Giordan and Fenggang Yang. Leiden: Brill, pp. 255–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, Talal. 1986. The Idea of an Anthropology of Islam. Washington: Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, Georgetown University. [Google Scholar]

- Baldeh, Latiffah Salima. 2025. ‘You Are My Brother, You Are My Sister… You Should Know Better…’: Racialised Experiences of Afro-Dutch Muslim Women: Navigating Intra-Muslim Anti-Blackness. Religions 16: 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Zhenhua 常振华. 2012. Sanzaju diqu Huizu qingnian libai bujiji xianxiang qiantan —jiyu dui Henansheng Kaifengshi de diaoyan 散杂居地区回族青年礼拜不积极现象浅谈——基于对河南省开封市的调研 (A Brief Discussion on the Phenomenon of Inactive Prayer of Hui Youths in Scattered Areas—Based on the Investigation of Kaifeng City, Henan Province). Hebei Minzu Shifan Xueyuan Xuebao 河北民族师范学院学报 (Journal of Hebei Normal University for Nationalities) 32: 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cissé, Daouda. 2013a. A Portrait of Chinese Traders in Dakar, Senegal. Migration Policy Institute. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/portrait-chinese-traders-dakar-senegal (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Cissé, Daouda. 2013b. South-South Migration and Trade: Chinese Traders in Senegal. Policy Briefing. Stellenbosch: Centre for Chinese Studies, Stellenbosch University. Available online: https://scholar.sun.ac.za:443/handle/10019.1/85283 (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Cissé, Daouda. 2017. Chinese Traders in Senegal: Trade Networks and Business Organisation. In Immigrants and the Labour Markets: Experiences from Abroad and Finland. Edited by Elli Heikkilä. Turku: Migration Institute of Finland, pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Gaofeng 代高峰. 2011. Kaifeng shiqu Yisilanjiao jiaopai duibi yanjiu——jiyu dui Kaifeng shiqu Yisilanjiao jiaopai de tianye diaocha 开封市区伊斯兰教教派对比研究——基于对开封市区伊斯兰教教派的田野调查 (A Comparative Study on the Islamic sects in downtown Kaifeng—Based on Field Research on Islamic Sects in Kaifeng City). Chengde Minzu Shizhuan Xuebao 承德民族师专学报 (Journal of Chengde Teachers’ College for Nationalities) 31: 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Diop, Amadou. 2009. Le commerce chinois à Dakar. Expressions spatiales de la mondialisation. Belgeo. Revue Belge de Géographie, 405–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittgen, Romain. 2010. From Isolation to Integration? A Study of Chinese Retailers in Dakar. Occasional Paper 57. China in Africa Project. Johannesburg: The South African Institute of International Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimmons, Caitlin. 2008. A Troubled Frontier. South China Morning Post, January 17. [Google Scholar]

- Gladney, Dru. 1996. Muslim Chinese: Ethnic Nationalism in the People’s Republic. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Ting. 1996. Jumping into the Sea: Cadre Entrepreneurs in China. Problems of Post-Communism 43: 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Nile. 2016. Qu’est-ce que ‘l’islam global’? Définitions pour un domaine d’étude. Diogène 256: 165–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Nile. 2020. Global Islam: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Chonglong. 2023. Enacting Chinese-Ness on Arab Land: A Case Study of the Linguistic Landscape of an (Emerging) Chinatown in Multilingual and Multicultural Dubai. Sociolinguistica 37: 201–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Chonglong. 2024. Linguistic Landscaping in Kathmandu’s Thamel ‘Chinatown’: Language as Commodity in the Construction of a Cosmopolitan Transnational Space. Contemporary South Asia 32: 360–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Chonglong, and Ge Song. 2024. ‘Al-Hay As-Sini’ Explored: The Linguistic and Semiotic Landscape of Dubai Mall ‘Chinatown’ as a Translated Space and Transnational Contact Zone. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, Kenneth J. 2003. God in Chinatown: Religion and Survival in New York’s Evolving Immigrant Community. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hazard, Eric, Lotje De Vries, Mamadou Alimou Barry, Alexis Aka Anouan, and Nicolas Pinaud. 2009. The Developmental Impact of the Asian Drivers on Senegal. World Economy 32: 1563–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Xinjie 何欣潔. 2017. Zai Seneijia’er de “Dongjing Jiujia”, kan “Liang ge Zhongguo” de Feizhou Jingzheng Shi 在塞內加爾的「東京酒家」,看「兩個中國」的非洲競爭史 (‘Dongjing Restaurant’ in Senegal, Witnessing the Competition Between ‘Two Chinas’ in Africa). Duan Chuanmei 端传媒 (Initium Media). August 23. Available online: https://theinitium.com/article/20170824-senegal-chinese-restaurant/ (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Henan Provincial Bureau of Statistics Office of the Leading Group of Henan Province for the Seventh National Population Census 河南省统计局河南省第七次全国人口普查领导小组办公室, ed. 2022. Henan sheng renkou pucha nianjian (2020) zhongce 河南省人口普查年鉴(2020)中册 (Henan Population Census Yearbook 2020, Book 2). Beijing: 中国统计出版社 (China Statistics Press). [Google Scholar]

- Hew, Wai Weng. 2014. Beyond ‘Chinese Diaspora’ and ‘Islamic Ummah’ Various Transnational Connections and Local Negotiations of Chinese Muslim Identities in Indonesia. Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 29: 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Joseph. 2018. Wrapping Authority: Women Islamic Leaders in a Sufi Movement in Dakar, Senegal. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Yunsheng 胡云生. 2005. Henan Huizu Shehui Lishi Bianqian Yanjiu 河南回族社会历史变迁研究 (A Study on the Social and Historical Changes of Hui People in Henan). Ph.D. thesis, Fudan University, Shanghai, China. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, Brent, and Xiaoli Zhou, dirs. 2010. The Colony: Chinese Commerce Sparks Tension in Senegal l Witness. Al Jazeera English. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bz0bhb5m3pQ (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Jaschok, Maria, and Shui Jingjun Shui. 2000. The History of Women’s Mosques in Chinese Islam, 1st ed. Richmond and Surrey: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Qiuyu. 2022. Giving and Belonging: Religious Networks of Sub-Saharan African Muslims in Guangzhou, China. Ethnography 24: 371–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Qiuyu. 2023. Religion-Based Business Ethics among African Muslim Small-Scale Businessowners in Guangzhou, China. African Human Mobility Review 9: 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaifeng Government 开封市人民政府. 2022. Kaifeng Gailan 开封概览 (An Overview of Kaifeng). Kaifeng Shi Renmin Zhengfu Menhu Wangzhan 开封市人民政府门户网站. June 9. Available online: https://www.kaifeng.gov.cn/sitegroup/root/html/8a28897b41c065e20141c3e9c9e7051f/85931bdd80f74370b38550da36f9c016.html (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Kernen, Antoine, and Benoît Vulliet. 2008. Chinese Small-Business Owners and Traders in Mali and Senegal. Afrique Contemporaine 228: 69–94. Available online: https://www.cairn-int.info/journal-afrique-contemporaine1-2008-4-page-69.htm (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Kuaishou. 2022. Zheng nengliang zhuan di, guanzhu wo dai nimen liaojie Feizhou fengtu renqing 正能量专递,关注我带你们了解非洲风土人情 (Spreading positive energy, follow me to discover the customs and culture of Africa) November 25. Available online: https://v.kuaishou.com/2DA8tdz (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Lai, David Chuenyan. 1997. The Visual Character of Chinatowns. In Understanding Ordinary Landscapes. Edited by Paul Groth and Todd W. Bressi. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Launay, Robert, and Benjamin Soares. 1999. The Formation of an ‘Islamic Sphere’ in French Colonial West Africa. Economy and Society 28: 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, Donald. 1972. The Survival of the Chinese Jews: The Jewish Community of Kaifeng. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xinghua 李兴华. 2004. Zhuxianzhen Yisilanjiao yanjiu 朱仙镇伊斯兰教研究 (Studies on the Islam of Zhuxianzhen City). Huizu Yanjiu 回族研究 (Jounal of Hui Muslim Minority Studies) 4: 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Guofu. 2009. Changing Chinese Migration Law: From Restriction to Relaxation. Journal of International Migration and Integration/Revue de l’integration et de La Migration Internationale 10: 311–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Shaonan. 2019. China Town in Lagos: Chinese Migration and the Nigerian State Since the 1990s. Journal of Asian and African Studies 54: 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makmuri, Katarina. 2012. Being an Asian American in Dakar & Dakar’s Chinatown. Albatrossic (Blog), September 6. Available online: https://albatrossic.wordpress.com/2012/09/06/being-an-asian-american-in-dakar-dakars-chinatown/ (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Manger, Leif O. 1999. Muslim Diversity: Local Islam in Global Contexts. East Sussex: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marfaing, Laurence, and Alena Thiel. 2014. Demystifying Chinese Business Strength in Urban Senegal and Ghana: Structural Change and the Performativity of Rumours. Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines 48: 405–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, Fiona. 2023. Text as City: Dakar’s Linguistic Landscape. In Africa and Urban Anthropology, 1st ed. Edited by Deborah Pellow and Suzanne Scheld. London: Routledge, pp. 427–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monica, Dehart. 2015. Costa Rica’s Chinatown: The Art of Being Global in the Age of China. City & Society 27: 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngeow, Chow Bing, and Hailong Ma. 2016. More Islamic, No Less Chinese: Explorations into Overseas Chinese Muslim Identities in Malaysia. Ethnic and Racial Studies 39: 2108–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Rundong. 2024. Project Assemblages: Identity Realignment in China-Africa Encounters in the Construction Industry in Congo-Brazzaville. African Studies Review 67: 632–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Donal Brian Cruise. 1971. The Mourides of Senegal: The Political and Economic Organization of an Islamic Brotherhood. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Osella, Filippo, and Benjamin F. Soares. 2020. Religiosity and Its Others: Lived Islam in West Africa and South India. Social Anthropology 28: 466–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Zhaoyi. 2025. Semiotic Landscapes in Bangkok’s Chinatown as a Tourist Destination. Cogent Arts & Humanities 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2009. Mapping the Global Muslim Population. Washington: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2009/10/07/mapping-the-global-muslim-population/ (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Qiu, Yu. 2024. The Art of Jieyuan: Ethical Affinity and the Cultivation of Chinese Buddhist Spirituality in Tanzania. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 30: 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raw Material Company. 2012. Boulevard Du Centenaire Made in China: Photographs by Kan Si. E-flux. Available online: https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/33288/boulevard-du-centenaire-made-in-china-photographs-by-kan-si/ (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Reinhart, A. Kevin. 2020. Lived Islam: Colloquial Religion in a Cosmopolitan Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Allen F., and Mary Nooter Roberts. 2007. Mystical Graffiti and the Refabulation of Dakar. Africa Today 54: 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Allen F., Mary Nooter Roberts, Gassia Armenian, and Ousmane Gueye. 2003. A Saint in the City: Sufi Arts of Urban Senegal. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. [Google Scholar]

- Sai, Yukari, and Johan Fischer. 2015. Muslim Food Consumption in China: Between Qingzhen and Halal. In Halal Matters: Islam, Politics and Markets in Global Perspective. Edited by Florence Bergeaud-Blackler, Johan Fischer and John Lever. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 160–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sautman, Barry, and Hairong Yan. 2016. The Discourse of Racialization of Labour and Chinese Enterprises in Africa. Ethnic and Racial Studies 39: 2149–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheld, Suzanne. 2007. Youth Cosmopolitanism: Clothing, the City and Globalization in Dakar, Senegal. City & Society 19: 232–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheld, Suzanne. 2010. The ‘China Challenge’: The Global Dimensions of Activism and the Informal Economy in Dakar. In Africa’s Informal Workers: Collective Agency, Alliances and Transnational Organizing in Urban Africa. Edited by Ilda Lindell. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 153–68. [Google Scholar]

- Scheld, Suzanne, and Lydia Siu. 2014. Veiled Racism in the Street Economy of Dakar’s Chinatown in Senegal. In Street Economies in the Urban Global South. Edited by B. Lynne Milgram, Karen Tranberg Hansen and Walter E. Little. Santa Fe: SAR Press, pp. 157–77. [Google Scholar]

- Schielke, Samuli. 2010. Second Thoughts about the Anthropology of Islam, or How to Make Sense of Grand Schemes in Everyday Life. ZMO Working Papers. Berlin: Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO). [Google Scholar]

- Seck, Abdourahmane. 2014. Les migrations au Sénégal, essai d’histoire par le bas à travers l’exemple de deux quartiers mythiques de la capitale: Medina et Allées du Centenaire. In La Migration prise aux mots: Mise en récits et en images des migrations transafricaines. Edited by Cécile Canut and Catherine Mazauric. Paris: Le Cavalier Bleu, pp. 129–44. [Google Scholar]

- Seesemann, Rüdiger, and Benjamin F. Soares. 2009. ‘Being as Good Muslims as Frenchmen’: On Islam and Colonial Modernity in West Africa. Journal of Religion in Africa 39: 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Xuefei. 2024. Maritime China, Sea Temples, and Contested Heritage in the Indian Ocean. International Journal of Heritage Studies 30: 653–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Xuefei, and Hangwei Li. 2023. Chinese Buddhism in Africa: The Entanglement of Religion, Politics and Diaspora. Contemporary Buddhism 23: 108–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, Jingjun 水镜君. 2006. Duihua, rentong yu shenfen xieshang——yige Huihui Jidutu jiating yinfade taolun he sikao 对话、认同与身份协商——一个回回基督徒家庭引发的讨论和思考 (Dialgoue, Self-Identity and Identity Negotiating: Discussions and Reflections Ignited by a Hui Christian Family). In Di er ci Huizuxue guoji xueshu yantaohui lunwen huibian 第二次回族学国际学术研讨会论文汇编 (The Collection of Articles of the Second International Academic Symposium on the Huizu Studies). Ningxia. pp. 245–52. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=AA8hwJ51-CQ6Q1ActDQ6exTFrwqu4yu-r_qE-j4RkxGokwN4H3W_avgmmnnhFF-KLK8A_u7fFJkhd-8X6wfuktggaCFc0fk8k_H0arrMznyNho2xNlePEm1MzXvXo2mmIPfBiCdFZsrLLQ1Bs--UapcnGo3FpkFS5l50LBc4FHvY=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Stamm, Eilert. 2006. L’engagement de la Chine au Sénégal: Bilan et perspectives, un an après la reprise des relations diplomatiques. Dakar: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, Quentin, and Ha Minh Hai Thai. 2024. Mapping the Character of Urban Districts: The Morphology, Land Use and Visual Character of Chinatowns. Cities 148: 104853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalón, Leonardo A. 1995. Islamic Society and State Power in Senegal: Disciples and Citizens in Fatick. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yuting. 2016. Chinese or Muslim or Both? Modes of Adaptation among Chinese Muslims in the United Arab Emirates. In Connecting China and the Muslim World. Edited by Haiyun Ma, Shaojin Chai and Chow Bing Ngeow. Kuala Lumpur: Institute of China Studies, University of Malaya, pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yuting. 2018. The Construction of Chinese Muslim Identities in Transnational Spaces. Review of Religion and Chinese Society 5: 156–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yuting. 2020. Chinese Muslims in Dubai: From Middleman Minority to Cultural Ambassador. In Chinese in Dubai: Money, Pride, and Soul-Searching. Leiden: Brill. Available online: https://brill.com/display/title/58458 (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Whyte, Shaheen, and Salih Yucel. 2023. Australian Muslim Identities and the Question of Intra-Muslim Dialogue. Religions 14: 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Terry Tak-Ling. 2010. Chinese Popular Religion in Diaspora: A Case Study of Shrines in Toronto’s Chinatowns. Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses 39: 151–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Kan 吴侃. 2022. Huayi Qingnian Li Ning: Yi Qiao Jiaqiao Jiang Zhong-Sai Youhao de Jielibang Chuan Xiaqu 华裔青年李宁:以侨架桥 将中塞友好的接力棒传下去 (Chinese Youth Li Ning: Build a Bridge as an Overseas Chinese and Pass on the Baton of China-Senegal Friendship). Zhongxin Wang 中新网 (China News Service). January 5. Available online: https://www.chinanews.com.cn/hr/2022/01-05/9644895.shtml (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Xiao, Allen Hai, and Shaonan Liu. 2021. ‘The Chinese’ in Nigeria: Discursive Ethnicities and (Dis)Embedded Experiences. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 50: 368–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]