1. Introduction

Background of the Study

Pakistan’s independence in 1947 was based primarily on religion, with Islam serving as the key ideological foundation for the country’s formation (

Khan and Laoutides 2024;

Jalal 2014). The All-India Muslim League argued that Muslims constituted a distinct nation, with Islam unifying them and justifying the demand for a separate homeland (

Jalal 2014). However, scholars argue that nationhood requires more than religion, emphasizing elements such as culture, language, history, and shared values (

Smith 1991;

Anderson 1983;

Gellner 1983). The Two-Nation Theory focused on religion, neglecting Pakistan’s cultural, linguistic, and historical diversity (

Kukreja 2020).

The creation of Pakistan was not driven by genuine religious unity but by Islam as a strategic political tool to obtain freedom from British India’s Hindu majority. Both Ayesha Jalal and Faisal Devji argue that Islam was used to assert Muslim distinctiveness and political autonomy, not to promote religious unity. Jalal focuses on Islam’s role in forming a separate identity, while Devji sees the movement as a response to political marginalization rather than religious ideology. Despite independence based on this ideology, Pakistan struggled to build a unified national identity amidst its diverse ethnic groups. Unlike nations with shared culture and history, Pakistan lacked a unifying mythos beyond Islam. Religion became a forcefully imposed tool to create unity, often sidelining ethnic plurality (

Jalal 2014;

Devji 2020;

Jaffrelot 2004).

In provinces such as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Balochistan, ethnic nationalism challenged state authority. To address this, Pakistan introduced the Objective Resolution (1949), declaring Islam as the state’s guiding principle (

Khoso and Rovidad 2023). This move aimed to make religion the central unifying force. Both civilian and military leaders used religion to counter ethnic dissent and legitimize their rule. In KP, strategically near Afghanistan, religious mobilization intensified during the Cold War, especially under the Zia-ul-Haq regime, which Islamized the region to serve geopolitical interests, such as the Afghan War (

Fazil et al. 2022). Madrassas proliferated, and Islamist political parties gained influence. In contrast, Balochistan’s secular nationalist tendencies resisted religious assimilation, with less success in integrating Islam politically. Despite this, the state used religion to suppress Baloch nationalist movements, framing them as anti-Islam and anti-state (

Rafiq 2022).

The background above lays the foundation for this study’s research. The study explores and critically compares the Pakistani state’s assimilationist strategies via religion as a strategic tool in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province and Balochistan province of Pakistan. The analysis focuses on key political eras and the role of religion in shaping state policies regarding different ethnic groups in KP and Balochistan. By combining historical analysis with theoretical perspectives, the framework offers a robust lens to explore the complexities of religion as a political instrument in Pakistan.

The research gap in this study lies in the limited exploration of comparative analysis of how religion has been employed as a strategic tool for national identity construction in two ethnically distinct and politically significant provinces of Pakistan: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) and Balochistan. Even though there is considerable work on religion in general and on nationalism and national identity in Pakistan in particular (

Jalal 2014;

Arsalan Khan 2025;

N. Khan 2012), limited studies are focusing on the specifics of these two regions and comparing their dynamics. These provinces are quite different in terms of their historical, cultural, and political backgrounds, but for quite different reasons, they are important for the Pakistani state. Due to its geostrategic significance, including accommodating programs such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), Balochistan has attracted international attention (

Khan et al. 2019). Simultaneously, it has had to deal with a growing secessionist crisis, which is expressed in ethnic and nationalist conflicts aggravated with violence. Because KP is close to Afghanistan, the province has always played a critical role in shaping Pakistan’s religious-political landscape as the headquarters for Islamist organizations and state-supported religious parties (

Shah 2015). Nevertheless, both regions have a similar experience of opposition to state policies that enforced religious, rather than ethnic and cultural, standards.

Inadequate information has been devoted to these provinces, and the relationship of religion to national identity is usually described as more standardized than it is, in fact. Most of the studies do not pay sufficient attention to the differential consequences of state policies of religious integration in Balochistan and KP. Moreover, contemporary scholarship remains insufficient in addressing the evolving dynamics of institutionalized and systemic injustices. These include the instrumentalization of religion and national development narratives, the legitimization of military operations under the guise of safeguarding national interests and security, and the persistent economic marginalization and political disenfranchisement of specific communities within these regions. Furthermore, the strategic stigmatization of particular groups (especially in Balochistan and KP) as anti-state or anti-Islam has significantly undermined inclusive nation-building efforts, contributing to the persistent failure of state-led integration policies. To this end, this study investigates the divergent trajectories and lived experiences of Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in the aftermath of Pakistan’s top-down assimilationist policies, shedding light on the socio-political consequences of state-led integration efforts. By critically examining Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan—two ethnically distinct and geostrategically significant provinces of Pakistan—this study seeks to analyze the implementation of Islamization policies, the patterns of resistance they provoked, and the divergent trajectories of their relative success or failure within each provincial context. The research is guided by several key questions, including:

How has the Pakistani state used religion as a tool for assimilation in Balochistan and KP?

What are the key differences in the intensity and effectiveness of these strategies in KP and Balochistan?

How have these assimilation tools contributed to the rise of religious nationalism in KP and Balochistan?

These questions frame the investigation into how religious policies were implemented and resisted across these provinces.

2. Review of Relevant Literature

2.1. Religion in Nation-Building and Identity Formation

Religion plays a significant role as a political instrument in nation-building and the formation of a unified national identity. This relationship is evident across various contexts, where religious narratives and institutions are intertwined with nationalistic ideologies, shaping collective identities and political landscapes. Previous studies have examined this dynamic in different settings.

Magalhães and Branco’s (

2024) study indicated that nationalism has been identified with roots in the religious tenets in Russia, with the Orthodox Church playing a critical role. Another study by

Guglielmi and Piacentini (

2024) indicated that in central and eastern Europe, religion has been established as a hallmark of nationhood. In countries such as Hungary and Poland, ethnopolitical entrepreneurs have politicized religious identity to foster national unity (

Guglielmi and Piacentini 2024). As well, there is the critical clergy role in the nation-building, as suggested by

McBride (

2014). They argue that clergymen significantly influenced the formation of American national identity by intertwining religious rhetoric with political events. These findings suggest that, similar to the case of Pakistan, clergymen have always played a critical role in fostering religious nationalism and facilitating state-led nation-building processes.

2.2. Religious Nationalism and State-Controlled Identity

Susumu and Murphy (

2009) examine Japan’s late Meiji period (1868–1912), where State Shinto was institutionalized to unify the nation and strengthen loyalty to the emperor. By elevating the emperor to divine status, State Shinto embedded nationalism through rituals and shrines, integrating local traditions into state-controlled practices. This fostered a unified national identity while suppressing dissent and other religions. State Shinto exemplifies the use of religion as a political tool for national assimilation and social cohesion, demonstrating how governments can leverage religion to create collective loyalty and justify expansion, often at the expense of pluralism and local customs.

Juergensmeyer (

1996) explores the fusion of religion and nationalism in modern politics, viewing religious nationalism as a response to globalization, secularism, and cultural anxieties. By merging religious ideologies with national identity, movements gain moral and divine justifications for political goals, promoting exclusivist agendas. He discusses Islamic revivalism, Hindu nationalism, and Christian political movements, highlighting their opposition to secular governance. While these movements aim to protect sacred traditions, they often reject pluralism, leading to conflict and intolerance. These findings highlight that religious states may use religious nationalism to unify populations under a singular framework, marginalizing minority groups and undermining pluralism.

2.3. Religion and Political Assimilation in Nation-Building

Fox (

2019) examines how states use religion for political assimilation by legitimizing authority and fostering national unity, particularly in diverse societies. Religion portrays leaders as divinely sanctioned and discourages opposition by labeling dissent as irreligious. Embedding religious values in laws and institutions establishes cultural hegemony, often sidelining minority beliefs. States adapt their religious use to social contexts, such as invoking religious rhetoric during crises. Examples include Saudi Arabia, where Wahhabism legitimizes the monarchy, and India, where Hindutva merges Hindu identity with nationalism. These strategies allow religion to consolidate state power, unify populations, and maintain cultural dominance.

The literature from international scholars offers valuable insights into the role of religion in nation-building, with significant implications for Pakistan’s case study. Globally, religion has been central to the nation-building process, often uniting diverse groups under a shared identity. However, this unifying force has frequently overshadowed ethnic diversity, promoting a reductionist view of integrating ethnic identities. This often led to the marginalization of distinct ethnic communities. Building on global examples as a backdrop, the following section explores how religion has shaped Pakistan’s nation-building efforts, particularly in the political assimilation of its ethnically diverse communities. It also highlights the challenges and limitations inherent in this approach.

2.4. History and Religion in National Building

The creation of Pakistan was envisioned as a movement for uniting Muslims under a shared religious identity, distinct from the Hindu-majority population. This vision was rooted in the belief that Muslims required a separate state to uphold Islamic principles and religious law (

Jalal 2014). However, the idea of Islam that underpinned the movement was abstract, lacking a concrete political framework for governance. The state’s formation rested more on religious identity than on coherent geographical, ethnic, or linguistic foundations (

Haqqani 2010;

N. Khan 2012).

To date, successive governments have considered, adopted, and used religion as a tool of assimilation, promoting Islam as the common denominator to unify the nation. The Objective Resolution of 1949 was spearheaded by Prime Minister Liaqat Ali Khan (

Ejaz and Rehman 2022). The resolution laid the ideological underpinnings of Pakistan’s reliance on religion for nation-building. It was a declaration of Islam as the guiding principle of governance, setting the country’s legislative and social order. This declaration set the state’s assimilationist agenda, with an agenda to unify Pakistan’s ethnically diverse populace under a shared religious identity (

Haqqani 2010).

Following independence, Pakistan faced significant challenges from ethnic nationalism, particularly in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. These provinces, marked by strong ethnic identities, witnessed rising nationalist sentiments that underscored the failure of religion to unify a multi-ethnic population. Despite Islam’s symbolic centrality, it could not bridge the deep-rooted ethnic divides (

Jalal 2014).

In this context, Islam became a strategic instrument rather than a guiding principle. Both civilian and military elites invoked religious rhetoric to legitimize authority and suppress dissent. This allowed them to maintain political dominance, not through inclusive governance, but by leveraging Islam’s symbolic power (

Zaman 2018). The lack of alternative unifying frameworks further entrenched this approach. The military, in particular, utilized Islamic narratives to justify its political role, aligning with civilian elites in manipulating religious identity for institutional power. This convergence of interests fostered a political environment where Islam served as a means of consolidation rather than unity (

Siddiqui 2012).

After independence, Islam became a central instrument in shaping Pakistan’s national identity and served as a means for legitimizing the authority of both civilian and military rulers (

Jalal 2014;

Fuchs and Fuchs 2020). However, the interpretation and role of Islam in Pakistan have never been uniform or fixed. Instead, it has continuously evolved in response to shifting political agendas, military strategies, ethnic tensions, and global geopolitical alignments (

Haqqani 2010;

Zubair et al. 2022). This fluidity in Islamic discourse has made it a highly adaptable and manipulable tool (

N. Khan 2012). Each successive regime—civilian or military—has instrumentalized Islam differently, employing it as a mechanism of assimilation at the expense of ethnic plurality and legitimacy to consolidate power (

Jalal 2014;

The Middle East Institute 2009;

Adeel Khan 2005).

During General Ayub Khan’s era (1958–1969), he initially sought to modernize the state and downplay religious politics. His regime focused on promoting a secular-modernist interpretation of Islam, aiming to create a modern Muslim nation-state. This was reflected in policies such as the controversial Family Laws Ordinance, designed to centralize power and unify the country under a progressive Islamic banner. Islam was portrayed as a unifying force to bridge ethnic divisions, especially between East and West Pakistan. However, as pressure from religious parties mounted, Ayub Khan reversed some of his secularizing policies. This shift, particularly regarding the Family Laws Ordinance, marked the reemergence of religious influence in politics. The growing opposition from religious factions ultimately contributed to Ayub Khan’s resignation (

Fuchs and Fuchs 2020;

Haqqani 2010;

Zubair et al. 2022;

Adeel Khan 2005).

During the period of Yahya Khan and Bhutto’s governments (1969–1977), General Yahya Khan inherited a divided country with ethnic tensions between Bengalis, Punjabis, Baloch, and Pashtuns. Due to this inheritance, Yahya Khan’s rule saw religion being used as a tool to suppress demands for regional autonomy, particularly in Bangladesh (East Pakistan), Balochistan, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where ethnic tensions were at their peak (

Akhtar and Jan 2022).

Subsequently, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, though a secular leader, increasingly leveraged Islamic rhetoric and symbolism to consolidate power. He blended Islam with socialism. Bhutto’s Islamization largely reflected Sunni Islam, given that the majority of Pakistan’s population follows Sunni Islam. Bhutto’s government pushed for Islamic principles to be incorporated into the legal framework. The 1973 Constitution of Pakistan declared the country an Islamic Republic. Bhutto’s Islamization policies aimed to integrate ethnic minorities such as Pashtuns and Baloch, who had strong regional identities and aspirations (

Hameed 2020).

Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamization ruled from 1977 to 1988. Zia took Islamization to a whole new level, using it as a central state doctrine to replace ethnic nationalism with an overarching Sunni-Islamic identity, transforming it into a hard-coded legal and ideological system. Zia implemented policies to Islamize the judiciary, education, and economy, using religion to legitimize his dictatorship. His regime coincided with the Soviet-Afghan war, during which KP became a focal point for Islamist militancy. Funded by the United States and Saudi Arabia, Zia facilitated the growth of madrassas in KP to recruit and train Mujahideen (fighters).

Islam was used to suppress ethnic movements in KP and Balochistan, portraying them as anti-Islamic and foreign-influenced. Their distinct cultural, linguistic, and religious practices were labeled heretical or backward. These regions were marginalized under the state’s Sunni-majoritarian interpretation of Islam (

Haqqani 2010;

N. Khan 2012). This not only deeply entrenched Islamic ideology in the region but also contributed to the long-term destabilization of Pakistan’s tribal areas (

Jaffrelot 2004;

Arsalan Khan 2025). Following Zia-ul-Haq’s regime, successive civilian and military governments—particularly under Nawaz Sharif, Pervez Musharraf, and later the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI)—continued to deploy religion strategically for political legitimacy, consolidation of power, and national integration (

Haqqani 2010;

Zubair et al. 2022;

Adeel Khan 2005;

Hameed 2020).

2.5. Comparative Analysis of Assimilationist Strategies

To analyze the assimilationist strategies in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Balochistan within the context of Pakistan’s state-building efforts, it is essential to examine the historical developments across various eras.

Table 1 illustrates the evolution of Islam across civil and military regimes, highlighting different forms of Islam strategically employed and the impact of Islamization policies on ethnic identity in both Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

The Pakistani state, particularly under the influence of the military-bureaucratic elite, has systematically employed Islam as a central element of national identity, aiming to suppress ethnic and linguistic pluralism. Scholars such as

Haqqani (

2010) and

Jalal (

2014) contend that Pakistan has never embraced a singular or unified interpretation of Islam. Instead, religious narratives have been strategically manipulated to serve political survival, foreign policy objectives, and the consolidation of internal power. Following independence in 1947, successive political leaders selectively used Islam as a tool to foster national unity and reinforce their authority. In some instances, Islam was wielded to consolidate political power, while in others it served as a mechanism to suppress ethnic tensions. Furthermore, Islam was invoked to address geopolitical concerns, such as the global “War on Terror” and rising Islamophobia, prompting General Pervez Musharraf to promote the concept of “Moderate Islam” while simultaneously supporting certain Islamist groups for internal strategic purposes. Additionally, the state’s use of religion to assimilate various groups is closely tied to military and security objectives, such as protecting the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) routes and managing post-9/11 dynamics (

Shaikh 2017;

Ullah et al. 2021). Therefore, it is evident that Pakistan has not relied on a singular interpretation of Islam but has instead used varying interpretations of Islam for different political, ethnic, and strategic objectives.

The Islamization policies were most aggressively implemented in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Balochistan, both regions characterized by distinct ethnic identities, separatist sentiments, and strategic geopolitical significance. However, the impact of these policies differed markedly between the two provinces. KP, predominantly inhabited by the Pashtun ethnic group, is marked by considerable internal diversity. Secular-nationalist sentiments are particularly strong in areas such as the Peshawar Valley, Charsadda, and Mardan, while the former Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) tend to be more conservative and deeply rooted in Islamic traditions. In contrast, Balochistan is home to a mix of ethnic groups, including Baloch and Pashtun populations in the north and the Hazara Shia community in Quetta, the latter of which has been subjected to sectarian violence (

Shah 2015;

Yasmin et al. 2023). It is important to recognize that Pashtun populations in KP are not homogenous; there exist significant ideological divides between the more secular Peshawar Valley and the more conservative regions of former FATA. While Islamization policies proved more effective in mobilizing the Pashtun tribal areas of KP, they encountered limited success in Balochistan, where the region’s diverse religious and ethnic communities resisted efforts at religious homogenization. For example, the Hazara Shia community in Quetta has faced sectarian violence that reflects broader patterns of national exclusion (

Imran et al. 2022).

Three key factors explain the disparity in the success of Islamization between KP and Balochistan:

Geography and Tribal Dynamics: The Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of KP, located on the border with Afghanistan, became a logistical and ideological base for jihadist movements. Here, Islam was aligned with tribal codes, making it a more potent force. In contrast, Balochistan’s geographical isolation hampered similar mobilization efforts (

Haqqani 2010).

State Investment: The Pakistani state invested heavily in KP’s religious infrastructure and forged strategic political alliances to support the Islamization agenda. In contrast, Balochistan remained underfunded and neglected in these efforts (

Jalal 2014).

Ethnic Identity: In KP, Islam often reinforced Pashtun ethnic identity, which helped consolidate state narratives. However, Baloch nationalism, with its deep-rooted ethnic cohesion and historical grievances, resisted religious homogenization, making Islam a less effective tool for unification (

Adeel Khan 2005).

2.6. State-Promoted Assimilation Tools

The state of Pakistan has historically employed various tools and strategies to promote political and social assimilation, particularly in the provinces of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Balochistan. These tools are comprehensively discussed in the following sections:

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), two Islamist political parties—especially Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI) and Jumat-e-Islami—have enjoyed consistent state support to counter ethnic nationalism and promote a unified religious identity. This backing enabled the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA), led by JUI-F and allies, to win 68 out of 124 seats in KP’s 2002 provincial elections. In contrast, Islamist influence in Balochistan remains marginal, with parties such as Jamaat-e-Islami gaining limited traction, often securing only 5–10% of the provincial vote (

Hamdani 2022). The state’s attempts to replicate KP’s model in Balochistan have faltered due to resilient nationalist resistance. Consequently, state-backed Islamist groups in Balochistan function more as instruments to suppress nationalist movements than as legitimate political forces, reflecting a stark contrast in their regional acceptance and impact (

Amin et al. 2018;

Imran et al. 2022).

The Blasphemy Act and related laws, such as the Tahafuz-e-Namoos-e-Risalat Act, have been wielded as instruments of political control. These laws often target minority groups (non-Muslims and Ahmadi groups) and dissenters, suppressing ethnic and religious pluralism. For instance, Sections 295–298 of the Pakistan Penal Code and the Tahafuz-e-Namoos-e-Risalat Act have not only criminalized dissent but also reinforced a singular Islamic identity as central to Pakistani nationalism. The Pakistan Penal Code introduced the death penalty for insulting the Prophet Muhammad. Over the years, numerous ordinances have been passed to solidify Pakistan’s identity as an Islamic state, particularly under Zia-ul-Haq’s regime, which institutionalized Islamic education and enacted strict blasphemy laws (

Azim 2019). The various statutes passed and adopted and the enforcement mechanisms used show the critical role played by religion as an assimilation tool (

Imran et al. 2022).

State media has played a pivotal role in othering non-Muslims and portraying ethnic identities as anti-state. From the early years of Pakistan, social media have been modified to glorify Islamic conquests and marginalize pre-Islamic history. For example, historical social content and propaganda have often begun with the Arab conquest of Sindh as the beginning of “Islamic enlightenment”, sidelining local cultural heritage (

Shah 2015). Celebration of figures such as Muhammad bin Qasim as national heroes is another example. Presently, state-sponsored YouTube channels, X/Twitter accounts, and Facebook pages propagate similar narratives. The social media platforms are used because of their capacity to reach and influence a large audience (

Shaikh 2017).

Ethnic nationalist movements in KPK and Balochistan have faced severe repression. Nationalist parties such as the Awami National Party (ANP) and Pashtun Protection Movement (PTM) in KP and Baloch nationalist groups in Balochistan have been labeled as foreign agents or terrorists. For instance, senior party leader Bashir Bilour was assassinated in 2012 (

Ahmad et al. 2023). State-sponsored violence, including target killings, has been a common tactic. For example, numerous PTM members have been assassinated in KP, while Baloch activists and freedom fighters have faced similar fates (

Khan and Chawla 2020;

Khan and Sial 2020;

Jafri 2021).

At independence, Pakistan had only about 200 madrassas, inherited from the regions of India. By conservative estimates, this number has now increased to over 17,000, though some reports suggest 25,000–40,000 madrassas, and most of them are in KP. These institutions serve 2.5 to 3 million students and employ thousands of mullahs as teachers and mentors (

Candland 2005). The expansion of madrassas has played a key role in Pakistan’s ideological Islamization, particularly under Zia-ul-Haq, with rapid growth in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s southern, rural, and tribal areas due to their proximity to Afghanistan. Saudi Arabia has funded Ahl-e-Hadith, Deobandi, and Wahhabi madrassas, promoting a stricter form of Islam to counter Iran’s influence and assert Sunni dominance in Pakistan. However, madrassa growth has been slower in Balochistan, signaling regional resistance to religious assimilation (

Adeel Khan 2005;

Haqqani 2010;

Vestenskov et al. 2018).

The Tablighi Jamaat (TJ), a significant Islamic missionary movement, is indirectly supported by the Pakistani state due to its alignment with the state’s Islamization policies and the goal of fostering a unified Islamic identity. The movement’s emphasis on pan-Islamic brotherhood, asceticism, and avoiding ethnic or sectarian distinctions complements the state’s narrative. By promoting disengagement from ethnic nationalism and politics, TJ suppresses ethnic assertions and promotes a homogenized religious culture. The state facilitates TJ’s activities, offering logistical support for gatherings such as the annual Ijtema, reinforcing religious unity and the state’s Islamization and national cohesion objectives (

Ejaz and Rehman 2022;

Adeel Khan 2005;

Arsalan Khan 2025).

Adeel Khan critically analyzes the role of education reforms in Pakistan as tools for both Islamization and political assimilation. Under General Zia-ul-Haq’s regime (1977–1988), education reforms were used to promote a unified Islamic identity, sidelining ethnic and religious minorities, including Baloch and Sindhi communities. These reforms marginalized regional cultures and languages by emphasizing Islamic values and history in curricula, reinforcing the state’s control (

Adeel Khan 2005). Zia’s initiatives, including the incorporation of Islamic teachings, Islamic Studies, and Pakistan Studies as compulsory subjects and the revision of history textbooks, aimed to align the population with the state’s Islamic vision and reduce ethnic divisions (

Jalal 2014). The Islamization of education not only served to strengthen Pakistan’s Islamic identity but also politically assimilated the nation, fostering unity through shared religious values. However, these reforms also deepened sectarian divisions and promoted a narrow interpretation of Islam, which led to ideological polarization within the country (

Haqqani 2010).

3. Methodology

This study is based on long-term fieldwork conducted across various sites in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, carried out in five phases: A 90-day visit in 2016, an 80-day visit in 2018, an 8-month visit in 2018, a 120-day visit in 2021, and a 60-day visit in 2024.

The researchers purposefully selected regions such as District Dir, Bajawar, Swat, Malakand, Waziristan, Bannu, Gwadar, Pasni, Turbat, and Quetta. These areas were chosen due to their significance in relation to state policies of Islamization, including the proliferation of madrassas, promotion of jihadist ideologies, the spread of Deobandi/Wahhabi ideologies, and the active role of the Tablighi Jamaat. Furthermore, these areas have been central to educational reforms aimed at influencing religious and cultural practices. The selection of these regions is also informed by the state’s strategic attempts to suppress ethnic nationalist movements in these regions by framing them as anti-Islam and anti-state. Additionally, the presence of Islamic political parties in these regions introduces an important layer of complexity to the interaction between state policies and local political dynamics. Moreover, the cultural distinctiveness of these regions, marked by norms and traditions that often contrast with the top-down implementation of Islamization policies. The interplay between state-driven religious initiatives, local cultural practices, and the political realities of these areas provides a unique and rich context for this study, making these regions particularly valuable for exploring the connection between Islamization policies and assimilation in these regions. We conducted extended field visits to both urban and rural areas within these districts, which were essential for gathering diverse perspectives on the issue of assimilation and the tools employed in these regions.

Given the study’s nature and the sensitive political and religious context, it was crucial to account for these factors during fieldwork. Strict control and tense political conditions necessitated relying on participant observation and informal discussions instead of formal interviews. This approach facilitated a deeper, contextual understanding, achieved through immersion rather than direct questioning. Informants included a diverse group, such as religious clerics, madrassa teachers, tribal elders, youth activists, students, and local politicians, offering a variety of perspectives. The researcher aimed to include both male and female participants in the study; however, religious and cultural norms in the regions, which restrict interactions between unrelated men and women, presented a significant barrier to accessing female participants. As a result, the study focused on female activists, students, political leaders, and party members, alongside male participants from similar backgrounds. Additionally, field visits were conducted to observe the conditions of religious minorities, including the Hazara community in Quetta and the Zikri communities in Gwadar, Balochistan. Efforts were made to ensure a diverse age range of participants, spanning from 20 to 68 years old, to capture a broad spectrum of perspectives. Fieldwork involved participation in mosques, madrassas, community gatherings, and political and official events. Long-term fieldwork and participant observation allowed the researcher to integrate into the daily lives of local people, gaining invaluable insights into the state’s long-term assimilationist policies and their reactions toward such policies. The researcher’s native background and community ties facilitated access to local communities, including religious leaders, politicians, and youth activists, reducing barriers to participant recruitment. In some instances, intermediaries with prior local connections played a key role in connecting informants.

3.1. Literature Review and Theoretical Underpinnings

We have nested this study in a historical analysis of systematic literature review, using Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) to search sources in English, Urdu, Pashto, and Balochi, ensuring inclusivity. Key databases such as JSTOR, Google Scholar, and ProQuest were searched with keywords such as “religion and national identity in Pakistan,” “state policies in KP and Balochistan,” and “assimilation and ethnic nationalism.” The review followed PRISMA methodology, involving screening, thematic coding, and cross-checking themes with field observations for theoretical triangulation. In qualitative research, particularly in ethnography, a widely used approach involves the integration of historical data with contemporary trends gathered through ethnographic methods. For instance, Sara Lowes effectively combines field data—such as contemporary surveys, interviews, and observations—with historical data. This methodological fusion enables Lowes to examine the evolution of economic systems, institutions, and behaviors over time, while also analyzing how past economic contexts shape current decision-making processes (

Lowes 2020). Similarly, Arunabh Ghosh, in Making It Count: Statistics and Statecraft in the Early People’s Republic of China, adopts a comprehensive approach that blends archival research, qualitative interviews, and transnational analysis to trace the development of statistical practices in China. Through this integrative methodology, Ghosh offers a thorough narrative on how statistical practices were crucial to the state’s efforts in social and economic transformation during the early years of the People’s Republic of China (

Ghosh 2020).

3.2. Data Collection Process

Data collection for this study relied on participant observation and informal discussions during five years of fieldwork. Due to the extensive duration and volume of data, risks of complications, mismanagement, and bias were present. To mitigate these, the research team followed specific data management protocols, organizing data by location, year, and research phase. A clear folder structure and descriptive file names, such as “Turbat_Madrassa_Dastarbandi_FieldNotes_2017,” were used to minimize confusion and ensure easy retrieval. For data safety, all data was stored in external hard drives and soft copies, accessible only to the research team with proper permissions. To reduce bias, multiple observers collected data to capture diverse perspectives, and informal conversations provided contrasting viewpoints. Additionally, researchers practiced reflexivity, regularly reflecting on their backgrounds, beliefs, assumptions, and their influence on data collection. We also triangulated our participant observation data with the data collected from informal discussions. Long-term immersion and repeated visits allowed for a deeper understanding of the context, enabling researchers to observe more dynamics. However, limitations include reliance on informal discussions and participant observation, which may have affected the depth and consistency of the data.

3.3. Data Analysis

Braun and Clarke’s six-step approach guided the thematic analysis using ATLAS.ti for a systematic, rigorous process. The first step, familiarization with the data, involved decoding interviews to gain a comprehensive understanding. Next, initial coding identified recurring patterns, themes, and concepts. The third step, searching for themes, focused on recognizing potential themes related to assimilation tools in the selected study areas. Themes were then reviewed and refined to ensure consistency and coherence. In the next step, themes were defined and named, ensuring clarity. Finally, a detailed report was written, presenting a clear, organized account of religion as a tool of assimilation in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. A similar strategy was adapted for the systematic literature review and its thematic analysis.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

Ethical compliance was central to this research. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Henan Normal University reviewed and approved this research with approval number HN-FIS-074. The study complies with ethical standards as outlined by university policies and international research ethics guidelines. Various ethical considerations were made. First, anonymity was considered critical, as all participants and observed communities were anonymized to protect their identities. Informed verbal consent was obtained from the participants before inviting them to an informal discussion. While participant observation does not involve direct interviews, implicit consent was obtained through respectful engagement and participation in community activities. Additionally, cultural sensitivity was considered, with the researcher ensuring that their presence and activities did not disrupt the local cultural and social fabric.

4. Results

4.1. Assimilating Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) via Religious Tools

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), located at the border with Afghanistan, has witnessed nationalist resistance movements since Pakistan’s independence. Its geostrategic location and the prominence of Pashtun identity have made it a focal point of Pakistan’s assimilation policies. The Pakistani state, seeking to minimize ethnic diversity, promoted a unifying national identity based on Islam (

Bhattacharya 2014). This section explores how religious tools have been utilized throughout different eras to integrate KP into Pakistan’s national framework, drawing on historical literature and the researcher’s extensive fieldwork data and observations.

4.1.1. Islamic Education and Identity Formation

Islamic education played a central role in the state’s project of ideological Islamization and identity formation in the early post-independence era (1947–1970s). Key tools for this effort included curriculum design and the recruitment and expansion of madrassas. These tools had a significant and lasting impact on Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), particularly in tribal areas, due to the region’s receptiveness to religious indoctrination. Pashtun society, especially in KP tribal areas, has historically been more religiously conservative, with strong cultural norms and a deep affiliation with Islamic traditions, fostering acceptance of madrassas and religious leaders. In contrast to Balochistan’s strong secular ethno-nationalist movements, KP’s secular Pashtun nationalism (ANP) was undermined by the state, empowering religious parties (JUI, JI) instead (

Adeel Khan 2005;

Haqqani 2010;

Jalal 2014).

Curriculum Design: Ater independence, schools in KP adopted curricula emphasizing Islamic history, values, and the Urdu language as a medium of instruction. This sidelined Pashto, which is deeply connected to Pashtun identity (

Yasmin et al. 2023;

Jan et al. 2023).

Madrassa Expansion: The rapid expansion of madrassas in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) during the 1980s was central to Pakistan’s Islamization policy. These schools, mainly Deobandi and Wahhabi, played a key role in shaping a unified Islamic identity, which was crucial for fostering national cohesion. In KP, they helped integrate Pashtuns into Pakistan’s broader Islamic framework, bridging regional and ethnic divides. As a result, these madrassas contributed significantly to the region’s Islamization and the political unification of KP with the national state (

Adeel Khan 2005;

Haqqani 2010;

Middle East Institute 2009;

Jaffrelot 2004).

Fieldwork in Dir, Bajaur, Swat, and Waziristan reveals how Pashtun identity is interwoven with Islamic discourse and state-building narratives. Friday sermons and madrassas education frame Pashtuns as both devout Muslims and guardians of Pakistan, reinforcing loyalty through religious-nationalist rhetoric. “During every Friday prayer, the researcher observed a collective supplication led by the mullah, in which the congregation prayed fervently: “O God, protect Pakistan from both external and internal threats. This is our beloved homeland, the place where we can practice Islam freely. O God, please safeguard us from those who harm Muslims and Pakistan, and bring justice to those who threaten our peace and security.” These portrayals position Pakistan as the “Qilla of Islam-fortress of Islam,” with Pashtuns as its frontline defenders. This strategic linkage of faith and nationalism fosters unity under the state’s ideological umbrella. However, such narratives are contested, especially as we observed in Swat, where some view these clerics as “Darbari mullahs-Politicized religious leaders” promoting state agendas rather than pure religious values, highlighting the internal discursive tensions. As one informant stated, “Islam and Pakistan will be good without these Darbari Mullahs”.

Our fieldwork in Malakand, Swat, Bannu, and Waziristan revealed the pervasive Islamization of education, extending beyond madrassas to include school curricula. Subjects such as science and history were infused with Islamic narratives; for instance, Qur’anic verses were incorporated into science textbooks, while historical accounts often highlighted Islamic figures, such as Muhammad Bin Qasim, and his conquest of the region. Local ethnic histories and indigenous heroes were largely absent. As one Pashtun activist remarked, “Our younger generation does not recognize our true heroes; they are only familiar with the Arabs—the looters—and believe they are the true heroes of Islam.” Similarly, textbooks in Urdu and English also glorified jihad, portrayed India as an adversary, and emphasized the supremacy of Islam. Such content significantly shaped Pashtun identity through the process of socialization in educational institutions.

“At a school speech competition attended by the researcher, a 9th-grade student passionately spoke about Kashmir, describing it as a vital part of Pakistan currently under Indian occupation. He urged the audience not to forget the suffering of Kashmiris, who look to Pakistan for support, and called for continued efforts to free them from oppression.” History texts for 9th and 10th grades, for example, depicted Hindus as deceptive and scheming, contrasting them with Muslims, who were portrayed as virtuous and tolerant. History texts for 9th and 10th grades, for example, portrayed Hindus as deceptive and scheming, in contrast to Muslims, who were depicted as virtuous and tolerant. When the researcher inquired with teachers about the authenticity of these historical accounts, the majority of them supported the portrayal. However, a few teachers expressed concerns, suggesting that these narratives contained significant exaggerations and misinformation.

4.1.2. The Institutionalization of Religion

The other religious assimilation tool employed was the institutionalization of religion, which mainly took place in the Zia-ul-Haq era (1977–1988). During this era, it marked a turning point in the use of religion for political assimilation in KP (

Aijaz et al. 2022). The tools used in the institutionalization of religion included Sharia laws and religious propaganda.

Sharia Laws: In this era, there was a great effort where Islamic legal codes were implemented nationwide. This was geared towards aligning state governance with religious doctrine. In KP, this reinforced the narrative that Pakistan was the defender of Islam (

Aijaz et al. 2022). An example of these laws was the Hudood Ordinances, which imposed strict penalties for crimes, reflecting a blend of religious and state authority (

Younas 2024).

Religious Propaganda: There was also a significant rise in the state-sponsored campaigns that highlighted slogans such as “Pakistan ka Matlab kya? La Ilaha Illallah” (What does Pakistan mean? There is no God but Allah), which linked national identity directly to Islamic faith (

Khan et al. 2024). As

Figure 1 shows, the installation of billboards in various places in Pakistan with the Pakistani national flag depicts the state’s ideology and nationalism.

From the researcher’s fieldwork and observation, it was observed that in 2013, the researcher observed a continued legacy of Zia’s policies. For example, shopkeepers were compelled to display national flags and Islamic slogans as part of military-led assimilation efforts. While effective in symbolically aligning the region with Pakistan, these measures often alienated those who felt their ethnic identity was being suppressed. For instance, during fieldwork in Swat, the researcher observed remnants of the Taliban’s influence, which aligned with state narratives promoting Sharia law. During fieldwork in Dir and Bajawar, informal conversations with Jirga members revealed nostalgic reflections on Pashtunwali customary code of justice, emphasizing honor, community justice, and tribal solidarity. The introduction of Hudood ordinances and similar laws heightened tensions between traditional tribal practices and state legal frameworks, influencing political mobilization and identity formation. Our field findings reveal that these laws have more influence in the tribal region of KP than in urban areas.

4.1.3. Counterterrorism for Assimilation

Interestingly, counterterrorism was also considered an aspect of assimilation, specifically during the post-9/11 era. The post-9/11 period introduced a dual challenge; combating extremism while promoting national unity. Some aspects adopted in this era include moderated Islamic campaigns and military operations.

Moderate Islam: General Pervez Musharraf’s policy of “Enlightened Moderation” was a key aspect of his political and ideological approach to moderating Islam and fostering national unity in Pakistan. This vision of moderate Islam was also intended to promote unity within Pakistan, which is a diverse country with various ethnic, religious, and regional divisions (

Aziz and Khalid 2017).

Military Operations: Anti-insurgency campaigns in tribal areas were framed as efforts to preserve Islamic unity and Pakistani sovereignty (

Musarrat and Khan 2014). These operations were named

Rah-e-Haq, Rah-e-Rast, Zarb-e-Azb, Radd-ul-Fasaad, Rah-e-Nijat, and Zarb-e-Azb, reflecting the connection of Islam with peace and development in Pakistan.

Our long-term observation reveals the state’s imposition of “moderate Islam” through centralized Sharia and modern courts has largely replaced traditional justice practices in KP, especially in tribal areas. During field visits to Bannu, Waziristan, and Malakand, the researcher observed Pashtun tribal jirgas in action and compared them to the state legal system. Many locals, frustrated with the corruption and inefficiency of the state courts, emphasized that tribal jirgas—grounded in Nang (honor), Badal (justice), and Nanawatai (forgiveness)—offered a more transparent, equitable, and culturally relevant method of dispute resolution. One informant recalled, “The Jirga has always been, and continues to be, a more effective means of delivering justice to the people than any government court.”

Our ethnographic research, informed by personal experiences in KP’s tribal areas from 2000 to 2024, reveals how military operations during this period served as tools for assimilation, targeting Pashtun communities, displacing families, and intensifying local conflicts. This created a paradox; while some segments of society (especially Islamic political parties) aligned more closely with the state, others grew increasingly resentful. For instance, the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) emerged in KP in 2018, criticizing military operations in Pashtun areas in the name of Islam and Pakistan. The researcher observed a significant increase in the number of military checkpoints. Military personnel routinely stop vehicles, demanding that passengers present their national identity cards and asking questions such as, “Who are you?” and “Where are you going?” One activist vehemently expressed, “I am Pashtun for over five thousand years, Muslim for more than seven hundred years, and Pakistani only for the last seventy years. This region is my home, yet Punjabi military personnel, stationed here as outsiders, are asking me who I am and where I am going. It is absurd to have my identity questioned in front of my own home.” The researcher participated in their political gatherings and observed their narratives against state assimilationist policies. They raised slogans such as “Lar aw Bar yaw Afghan”, emphasizing one shared identity of KP Pashtuns with Afghanistan.

4.1.4. Challenges to Religious Assimilation

Despite these efforts to base religion as an assimilation strategy in KP, our fieldwork findings indicate that such assimilation strategies have faced growing resistance in recent years. For instance, the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) is a grassroots movement that has challenged the state’s narratives, calling for recognition of Pashtun grievances. The PTM challenges state narratives by advocating for Pashtun rights and addressing grievances related to socioeconomic underdevelopment and the demilitarization of Pashtun regions, which undermines state legitimacy. Additionally, the generational shifts have weakened assimilation efforts. Younger generations are questioning the historical narratives of assimilation through Islam and seeking a balance between ethnic and religious identities. For instance, the young generation is more inclined toward progressive values. This resistance is expressed through cultural and poetic discourse to challenge the state’s oppressions.

In the field, two key aspects were observed that facilitated the assimilation resistance: the cultural resistance and symbolic actions. Regarding cultural resistance, many Pashtuns, particularly in rural areas, maintain a dual identity incorporating Islamic and ethnic elements. They hold anti-Islamic beliefs of resisting state-imposed Islamic narratives. As for the symbolic actions, poems, cultural artifacts, and ethnic symbols, such as flags and slogans, are employed.

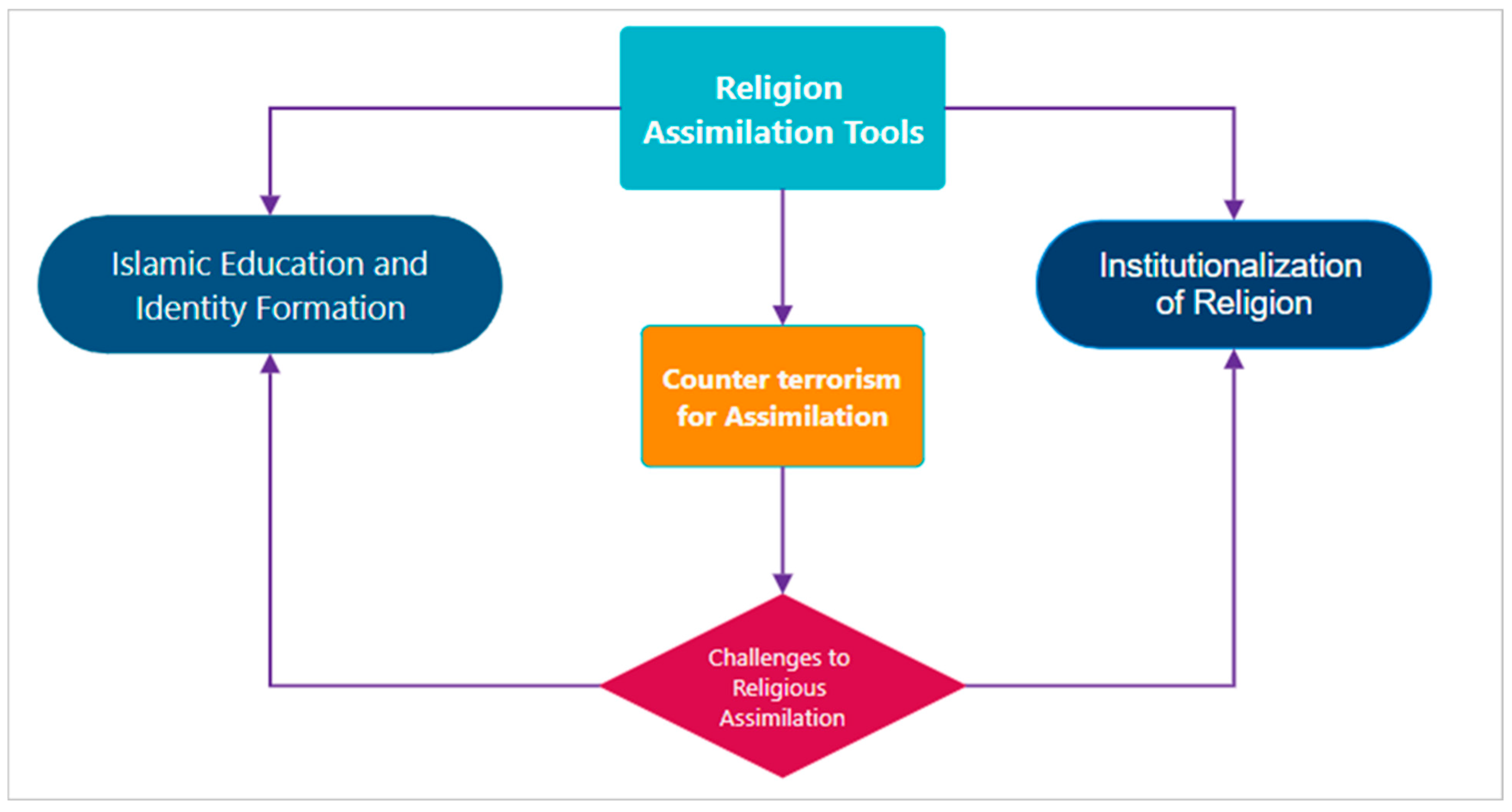

It is conclusive that, as far as effectiveness is concerned, religious assimilation strategies in KP have had mixed success. While in urban as well as more settled districts of KP some Pashtuns identify strongly with Pakistan’s Islamic identity, in significant segments of the population, they feel alienated due to socioeconomic inequalities and the suppression of ethnic identity. In the tribal Pashtun belt, strategies such as madrassa networks, curriculum design, and Sharia Law, especially the Pakistan Penal Code, have been successful; however, counterterrorism and military operations face huge criticisms. The adopted tools are summarized and illustrated in

Figure 2.

4.2. Promoting National Identity in Balochistan via Religion as a Tool

Balochistan, Pakistan’s largest and most resource-rich province, has faced challenges with the state’s assimilation policies. The Baloch people, with their strong tribal identity and cultural distinctiveness, have resisted efforts to integrate into Pakistan’s national framework (

Khattak et al. 2022). Since independence, the state has used religion as a tool to promote national identity, positioning Balochistan as part of the broader Muslim Ummah (

Ejaz and Rehman 2022). However, the socio-political dynamics in Balochistan have frequently countered these strategies. Based on historical literature and the researcher’s extensive fieldwork data and observations, the following sections explore these tools and their impacts on the region’s identity.

4.2.1. Religious Rhetoric and Initial Resistance

The efforts toward assimilation started in the early days of the post-independence period (1947–1970s). In the initial years, the state emphasized Pakistan’s creation as a homeland for Muslims (

Dar 2018). Religious rhetoric aimed to counteract tribal loyalties, positioning Islam as the common ground for unity.

However, tribal leaders in Balochistan resisted state efforts to impose an Islamic identity, seeing it as a threat to their authority and traditions.

4.2.2. Institutionalizing Religion in Balochistan

Under the Zia-ul-Haq era (1977–1988), the state increased efforts and doubled down on religious tools to assimilate Balochistan into the Pakistani state. Various tools were used in this era, including madrassa networks, Islamic propaganda, and military and religious nexus.

Madrassa Networks: Efforts were made to establish and expand madrassas across Balochistan, many of which aligned with Deobandi ideology (

Malik 1989). These institutions aimed at promoting religious unity over ethnic identity. The promotion of Sunni madrassas in Balochistan has had a significant impact on minority groups, including Shia and Sufi Baloch communities, undermining their ethnic and religious identities (

Siddiqui 2012).

Islamic Propaganda: Zia’s government introduced the widespread use of slogans and ideological campaigns. These slogans aimed to instill a sense of belonging among the Baloch to the broader Islamic nation of Pakistan (

Shah 2012).

Military and Religious Nexus: The Pakistani military formed strong alliances with religious groups such as Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, even incorporating local Baloch people into these organizations to strengthen its control over Balochistan. This partnership was used to counter and suppress separatist movements, often characterizing such dissent as antithetical to Islamic principles. Additionally, the alliance facilitated the rise of Islamic extremism and sectarianism (

Shah 2012).

Fieldwork in Gwadar, Turbat, and Quetta revealed the complex role of madrassas in shaping local identities across Balochistan. Particularly, Deobandi and Wahhabi madrassas are prevalent in Pashtun-majority regions, where they have notably undermined the influence of Sufi Islam. This sectarian shift has had a pronounced effect on the Gichki, Barelvi, and Yarahmadzai tribes, historically known for their Sufi traditions. One elderly tribal leader stated, “Our ancestors followed the peaceful teachings of Sufi Islam, which connected us to our land and people. However, now, with the rise of Wahhabi madrassas, our people in Balochistan are drifting away from these traditions, embracing rigid doctrines that divide us rather than unite us.” Over time, the growth of Sunni/Wahhabi madrassas has exacerbated sectarian tensions, leading to significant violence and displacement among Hazara and Ismaili communities, while Baloch nationalist movements remain largely unaffected by these ideological shifts.

During our fieldwork in rural Balochistan, we observed state-backed religious gatherings, notably the Tablighi Jamaat Ijtima held in 2024. The gathering was heavily secured by the state, despite the region’s notorious insecurity, where daily occurrences of targeted killings and bomb blasts affect ordinary people. This stark contrast in security arrangements led to significant reactions from local nationalist activists. One activist remarked, “Balochistan is the most insecure place for ordinary people; every day there are killings and bomb blasts, yet the state does not provide security. However, the Tablighi Jamaat receives full protection. This signals something deeper. Protecting the public is not a priority, but the Tablighi Jamaat is.” We also observed several other interesting events, including the madrassa graduation ceremonies, with the presence of government officials. During the fieldwork, it was observed that Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) and Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI) madrassas promote political assimilation in Balochistan by blending religious education with activism. JUI and JI focus on Sharia law and socio-political Islam, encouraging democratic participation to establish an Islamic state. They also emphasize Deobandi teachings, serving as platforms for campaigns and mobilization. Both align regional concerns with national Islamic movements, fostering shared identity. By integrating education, social welfare, and activism, these madrassas shape regional politics in line with their broader Islamic goals. However, the attendance of local Baloch tribes was minimal, reflecting their skepticism toward these efforts.

4.2.3. Counterterrorism as Assimilation:

Through our fieldwork, we observed how the state’s counterterrorism strategies in Balochistan are deeply intertwined with efforts of cultural assimilation. The Pakistani government labels Baloch nationalist movements as “terrorist” and “anti-Islamic”, aiming to delegitimize their calls for autonomy and cultural preservation. The military establishment has transformed Balochistan into a vast iron cage, embedding thousands of checkpoints in key locations such as Gwadar, Turbat, and Quetta. These checkpoints, similar to the relentless bars, disrupt the daily lives of ordinary citizens, tightening the grip on movement and freedom. The once open expanse of Balochistan now feels stifled, with its people navigating a maze of barriers that infringe upon their basic rights and routines. Operations such as Zarb-e-Azb and Azm-e-Istehkam, named with Islamic connotations, were officially framed as defensive measures to combat terrorism and stabilize the country. During political events, members of state-controlled political parties openly declared that militants in Balochistan were not Muslims, suggesting they must be eliminated to protect Muslims from fitna (rebellion). Moreover, in the wake of the August 2024 Balochistan attacks, where the BLA executed 23 Punjabi civilians in Musakhail, Balochistan, the state’s use of religious rhetoric—calling insurgent actions haram and anti-Islamic—aims to delegitimize the Baloch insurgency. This framing portrays the militants not just as political opponents, but as violators of religious principles, thereby rallying public support against them. We found that counterterrorism in post-9/11 has adopted a new tool of forceful assimilation in KP and Balochistan, which in most of the cases, is quite effective.

4.2.4. Declining Efficacy of Religious Tools

During our fieldwork in Balochistan, it became clear that Pakistan’s use of religion as a tool to integrate Balochistan into the national framework has largely failed. Through interactions with tribal elders, civil activists, and young participants in nationalist movements, including our direct participation in the 2024 Baloch Nationalist March toward Islamabad, we observed that the Baloch sense of distinct ethnic identity remains deeply entrenched. The idea of Islam as a unifying force was widely rejected, with many referencing Mir Ghous Bakhsh Bizenjo’s historical argument, as one activist stated, “Religious unity does not mean political unity. We may all be Muslims, but our problems, our traditions, our cultures, and our aspirations are different. Political unity must be based on the recognition of these differences and the respect for the rights of each people to determine their own future.”.

One of the most prominent signs of resistance was the widespread cultural pushback against state-imposed national identity. Locals frequently refused to participate in state-sponsored events such as Pakistan’s Independence Day, opting instead to celebrate traditional Baloch festivals. While religious faith is respected at the individual level, religion as a political tool is viewed with suspicion, seen not as a means of integration but as an attack on their cultural autonomy.

We also observed the contradictory nature of state policies. In Gwadar, we visited an Allama Iqbal Open University campus funded by the state, yet a local NGO promoting Balochi language and culture was denied funding. This duality, supporting religious institutions while suppressing ethnic identity, created deep disillusionment. One activist said, “They promote Urdu but demolish our poetry and language.”

The socioeconomic issues were equally stark. Many Baloch expressed frustration over basic life facilities and ongoing discrimination. As one local put it, “religious unity does little to address empty stomachs and unmet needs.” Furthermore, the militarization of the region intensified resentment. Multiple families shared stories of relatives who had been forcibly disappeared. The military presence in rural areas bred fear and distrust rather than loyalty, and instead of fostering unity, it radicalized the youth, shifting the nationalist movement from tribal elites to the educated masses.

Our findings reveal that Baloch nationalism is deeply rooted in a sense of distinct civilization, with historical memories of autonomy such as the Khanate of Kalat inspiring resistance. Islam, while important, could not overcome the stronger loyalties to Baloch ethnic, cultural, and territorial identity. Religious assimilation failed because it lacked the foundation of justice and respect for Baloch identity, fueling resentment, cultural resistance, and broad-based civil struggle.

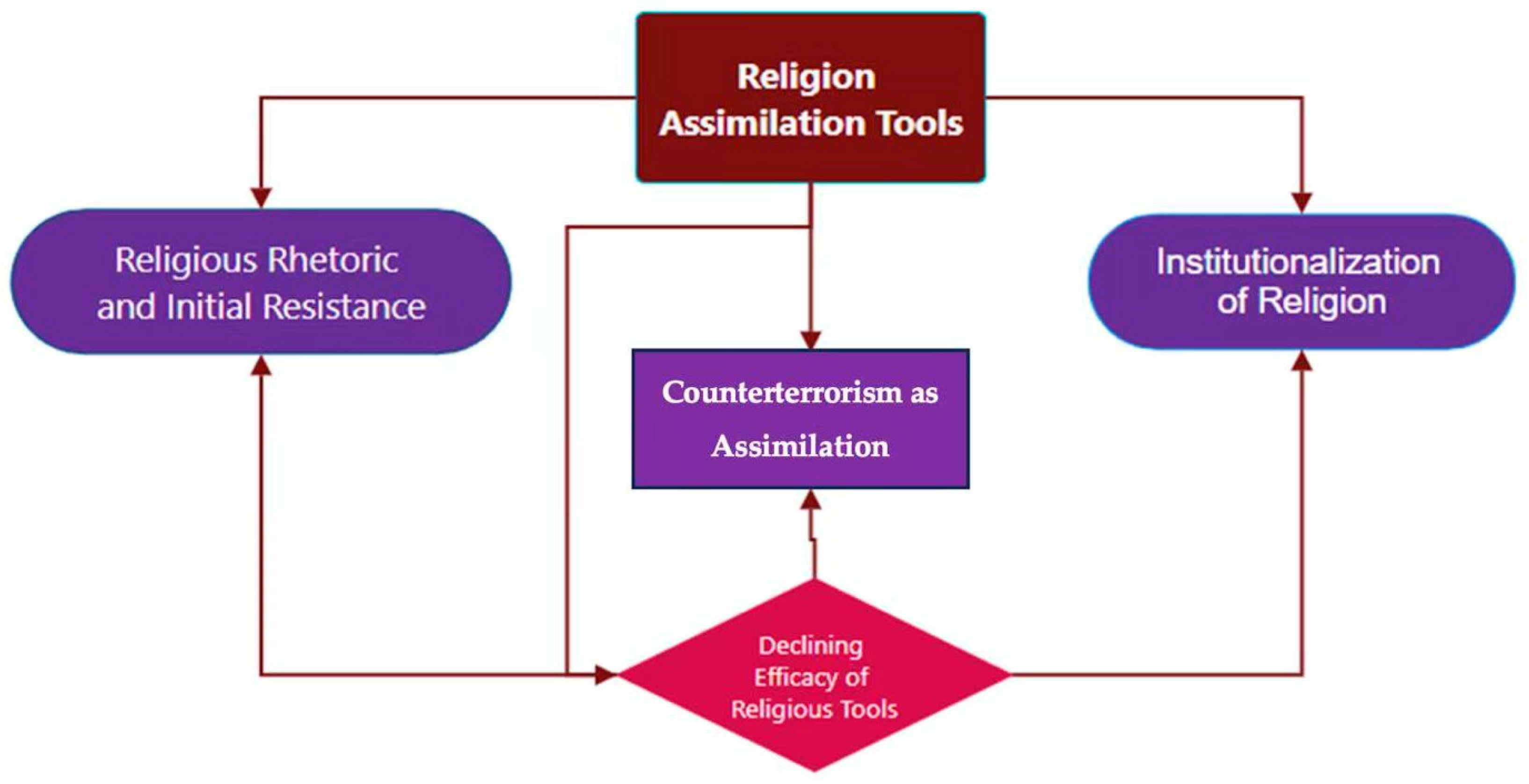

Thus, religious nationalism not only failed to integrate Balochistan but also contributed to the expansion of the nationalist movement. The analysis of these religious tools is summarized in

Figure 3.

4.3. Comparison of Religion as an Assimilation Tool in KP and Balochistan

This section compares how religion has been used as an assimilation tool in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Balochistan, highlighting their distinct responses. The historical analysis and our fieldwork findings reveal that the effectiveness of religious assimilation varies significantly between the two provinces. In KP’s tribal Pashtun belt, strategies such as madrassa networks, curriculum reforms, and the implementation of Sharia law, particularly the Pakistan Penal Code and Hudood Ordinance, largely fostered a Pakistani identity centered around Islam. This perceived success can be attributed to several factors, including the presence of major Islamic groups in KP, political parties’ influence in the region, the Afghan-Soviet War, KP’s proximity to Afghanistan, and deeply embedded Islamic traditions in Pashtunwali (

Haqqani 2010;

Jalal 2014;

Adeel Khan 2005). However, the process of assimilation in KP remains ongoing and deserves critical reevaluation. The recent emergence of the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) in 2018 challenged the state’s narrative by foregrounding grievances related to enforced disappearances, militarization, and ethnic marginalization (

Yousaf 2019). The PTM’s popularity among youth in KP and former FATA underscores ongoing tensions between the local population and the central state, revealing deep fractures beneath the apparent religious unity.

In contrast, Balochistan has experienced significant resistance to state assimilation efforts, largely due to the region’s distinct historical, cultural, and socio-political context. The expansion of madrassas in Balochistan has been constrained, with their primary focus being the suppression of nationalist movements rather than the promotion of widespread religious education. Consequently, this approach has exacerbated sectarian tensions rather than fostering religious cohesion. Nationalist leaders in Balochistan have portrayed the state’s Islamic rhetoric as a means of oppression, further distancing the local population and intensifying opposition to state-imposed religious narratives.

5. Discussions

This study explores the use of religious tools in Pakistan’s assimilation strategies in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Balochistan, shedding light on the diverse responses to these efforts. The findings from our historical analysis and the fieldwork reveal significant differences in the success and impact of these strategies, shaped by the regions’ distinct cultural, ethnic, and socio-political contexts. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the assimilation of Pashtun identity through legal regulations and religious education, particularly madrassas, played a crucial role in the state’s Islamization agenda. The rapid expansion of madrassas during the 1980s, particularly in the tribal areas of KP, was central to Pakistan’s religious-nationalist narrative. These institutions, heavily supported by both the state and foreign (particularly Saudi and Gulf) funding, not only promoted religious identity but also became hubs for militant Islamic ideologies.

Adeel Khan (

2005) and

Haqqani (

2010) also noted the use of madrassas as instruments for political unification and religious alignment with the state.

Our extensive fieldwork reveals that the curriculum design in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) schools reinforced a broader narrative of assimilation. The state’s emphasis on promoting Islamic history, values, and Urdu as the primary medium of instruction effectively marginalized Pashto, thereby diminishing the region’s linguistic and cultural identity. Unlike in Balochistan, where resistance to such assimilation efforts was more pronounced, KP’s more profound religious conservatism facilitated a more effective integration with the national identity, which is heavily centered around Islam.

Our historical analysis reveals that the institutionalization of religion during Zia-ul-Haq’s era (1977–1988) marked a critical phase in Pakistan’s religious assimilation strategy. The introduction of Sharia laws and widespread religious propaganda, including slogans such as “

Pakistan ka Matlab kia, La Ilaha Illallah,” served to reinforce the narrative that Pakistan was an Islamic state. As

Aijaz et al. (

2022) observe, this period saw a significant blending of religious and state authority, particularly in KP, where the legal framework and political mobilization were more receptive to Islamic ideologies. However, the state’s efforts to institutionalize religion also faced resistance from nationalist segments and criticism from the general population. Fieldwork in Swat and other KP areas revealed growing discontent with the politicization of religion, particularly by religious leaders who were perceived as “Darbari mullahs” (state-backed clerics). This underscores the tensions between religious-nationalist rhetoric and local interpretations of Islam, a point also highlighted by

Adeel Khan (

2005) and

Haqqani (

2010), who caution against the state’s over-reliance on religious symbolism to foster national unity.

The findings from Balochistan present a notable contrast to the situation in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). In Balochistan, the state’s use of religious tools, such as the expansion of madrassas and the promotion of Islamic slogans, has encountered considerable opposition. Unlike KP, where religious identity was intertwined with Pashtun culture, Balochistan’s strong tribal identity and historical autonomy have fueled opposition to these efforts. Islam as a unifying force, was viewed by many Baloch nationalists as an infringement on their ethnic identity. The resistance is further exacerbated by the state’s manipulation of Islamic narratives to suppress Baloch nationalist movements. Madrassas in Balochistan, often aligned with Deobandi and Wahhabi ideologies, have contributed to sectarian tensions, particularly against Shia, Hazara, and Sufi Baloch communities. The state’s backing of these madrassas and their association with extremist ideologies has made the religious assimilation process in Balochistan even more contentious.

This long-term fieldwork highlights a generational shift in both Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Balochistan, with younger populations increasingly questioning the state’s religious narratives. In KP, the rise of progressive values, particularly under the leadership of the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM), reflects a desire to strike a balance between Pashtun identity and the state’s religious-nationalist rhetoric. Similarly, in Balochistan, younger nationalist leaders such as Mahrang Baloch are rejecting the state’s imposition of an Islamic identity in favor of emphasizing ethnic Baloch identity and regional autonomy. This shift demonstrates a growing preference among the youth for democracy, cultural accommodation, and regional autonomy as key pillars of nationhood, rather than reinforcing religion as a tool of state control.

The generational shifts in these regions are crucial to understanding the declining effectiveness of the state’s religious assimilation strategies. The younger generation in both provinces advocates for local governance, resource utilization, and the protection of cultural and ethnic identities as alternatives to state-imposed religious nationalism. This preference for decentralized governance, multiculturalism, and autonomy challenges the state’s use of religion as a unifying force.

Moreover, the state’s post-9/11 counterterrorism strategies, particularly framed as “Islamic” efforts to safeguard Pakistan’s sovereignty and national unity, have deepened the alienation of local populations. In Balochistan, these operations, which have been presented as measures to maintain unity, have been perceived as oppressive by the Baloch and Pashtun nationalist movements. This perception has contributed to the radicalization of youth and the rise of movements such as the PTM. In contrast, the region’s resistance to religious assimilation reflects a desire for greater political autonomy and a rejection of militarized state-building models.

The findings suggest that the state’s religious assimilation strategies have met with varying success. In KP, where religion has been closely tied to national identity, the state’s Islamization policies garnered significant support. However, in Balochistan, the state’s efforts faced substantial resistance, as ethnic identity, cultural autonomy, and regional self-determination played more significant roles in shaping local responses. This growing resistance among the youth, combined with skepticism toward the state’s religious narratives, indicates that the imposition of a singular religious-nationalist identity may be unsustainable.

In this context, alternative state-building models, such as multiculturalism, decentralized governance, and regional autonomy, offer more promising paths forward. By embracing the diversity of identities within Pakistan and promoting political decentralization, the state can address the aspirations of marginalized groups and foster greater national cohesion without relying solely on religion as a unifying force. Moreover, the demilitarization of state policies and a move toward peaceful dialogue and cooperation can create a more inclusive, democratic framework that respects ethnic and cultural autonomy. These models not only align with the desires of younger generations but also hold the potential to create a more stable and resilient state that respects its diverse population.

6. Policy Recommendations

Based on the findings of this research, several key recommendations are proposed. First, promoting inclusive governance is essential. The state should transition from assimilationist policies to strategies focused on accommodation and inclusivity. Establishing platforms for dialogue with local leaders and representatives from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Balochistan will help address political grievances and ensure ethnic identities are integrated into national frameworks. Second, addressing economic justice and development is crucial. Fair resource distribution and economic opportunities should be prioritized, particularly in Balochistan, where infrastructure projects such as CPEC should benefit local communities. Both provinces need clear, region-specific policies to combat unemployment, poverty, and economic marginalization. Third, educational reforms are necessary. The current religious approach should be replaced with a more inclusive, multicultural, and regionally relevant curriculum. Incorporating Pashtun and Baloch cultures into textbooks will help foster a sense of belonging among students from these ethnic groups, preventing feelings of exclusion. Lastly, for successful integration, the state must respond to nationalist demands by distinguishing between political grievances and militancy. Nationalist movements should not be labeled as anti-state or foreign agents but instead addressed through democratic engagement and genuine political dialogue.

7. Conclusions

The use of religion as a tool for political assimilation in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Balochistan has been evaluated in this study, revealing varying degrees of success across the two regions. In KP, the state’s religious strategies were more effective due to historical and cultural factors, including the province’s involvement in the Afghan conflict, alignment with Islamist movements, the establishment of Islamist political parties, and the state-supported madrassa network. Religious slogans, curriculum reforms, and political parties further facilitated the integration of Pashtun identity into a broader Pakistani-Islamic framework.

In contrast, in Balochistan, state-driven religious assimilation strategies have largely failed. Strong ethnic nationalism, historical grievances, economic exclusion, and political marginalization have fueled resistance to religious narratives. Efforts such as madrassa expansion, state-backed religious movements, and delegitimizing nationalist groups as “anti-Islamic” have had limited success. The militarized suppression of Baloch nationalist voices has further exacerbated the province’s sense of alienation.

The study underscores that religion alone cannot unify a diverse nation, particularly in regions with entrenched ethnic identities and systemic inequalities. The failure in Balochistan highlights the limitations of coercive, top-down strategies that overlook the importance of economic development, political inclusion, and cultural accommodation. For sustainable nation-building, policymakers must address the root causes of alienation through inclusive approaches that go beyond religious and political assimilation.

Inclusive approaches entail strategies that promote equity and mutual respect across different social and ethnic groups. Practical examples include equitable resource distribution, where resources such as financial, educational, and healthcare are fairly distributed across different regions and communities, particularly those historically marginalized. In Balochistan, for instance, equitable distribution of resources could help address the region’s economic exclusion. Another example is the demilitarization of civilian zones, which, in regions such as Balochistan, where militarization has increased alienation, can help restore trust and foster peaceful dialogue. Legal protection for ethnic groups is also vital, where safeguarding the rights and cultural identities of ethnic minorities through legal frameworks can address concerns about cultural preservation and political autonomy, such as in Balochistan. Lastly, curricular reform is important in removing extremist ideologies and teaching students about the value of diversity and tolerance. In both KP and Balochistan, introducing curricula that celebrate regional identities and promote inclusive, pluralistic views can contribute to peaceful development and integration.

The study highlights that the imposition of a singular identity in regions with strong and resilient cultural identities, such as Balochistan, is unlikely to succeed in achieving national unity. By adopting inclusive nation-building approaches focused on economic equity, political representation, and multiculturalism, Pakistan can foster genuine national cohesion.

8. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the generalizability of the findings is limited as the research focused on two provinces, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, each with unique historical, cultural, and political contexts. Thus, the results may not be applicable to other regions of Pakistan or countries with different socio-political dynamics. Additionally, the study did not cover all areas within these provinces; however, long-term fieldwork was conducted in the most relevant regions where the issue is most prominent. Another limitation is the reliance on and use of qualitative data and the lack of structured interviews. Qualitative data provides quite a comprehensive and deep analysis; however, it is also prone to subjectivity.

Furthermore, access to data that could have been useful to the study was difficult due to the sensitive nature of the topic. Future researchers could consider investigating how religious assimilation strategies vary among other ethnic minorities in Pakistan. Future studies could consider quantitative exploration by incorporating statistical analyses, such as surveys or demographic studies, which could provide a more robust validation of the qualitative findings.