Representations of Divinity Among Romanian Senior Students in Orthodox Theology Vocational High School

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Some Theoretical Considerations

2.1. Secularization Is Neither Irreversible nor Universal

2.2. Canonical Representations of God in Orthodoxy

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

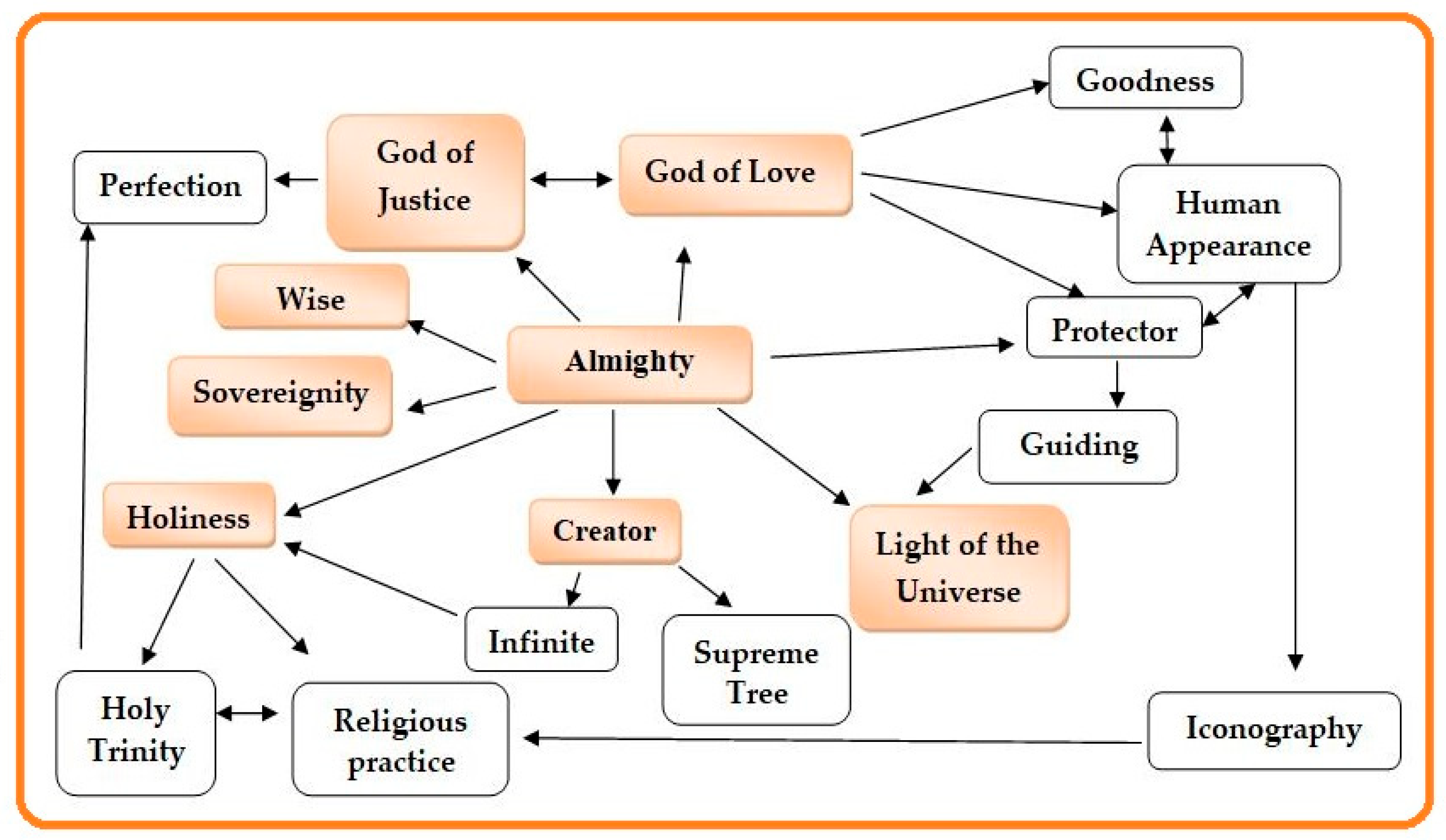

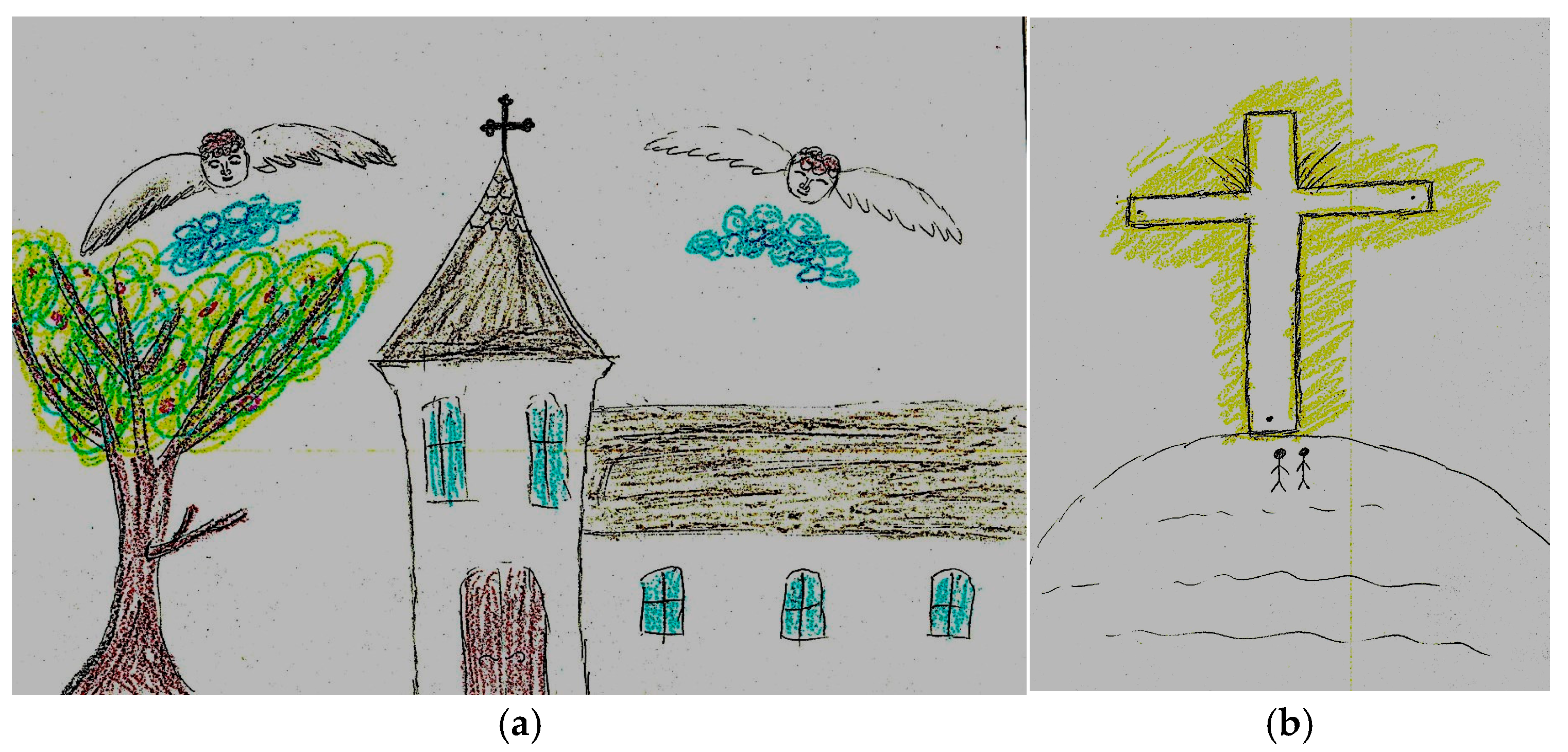

4.1. Divine Attributes Highlighted by Theology Students

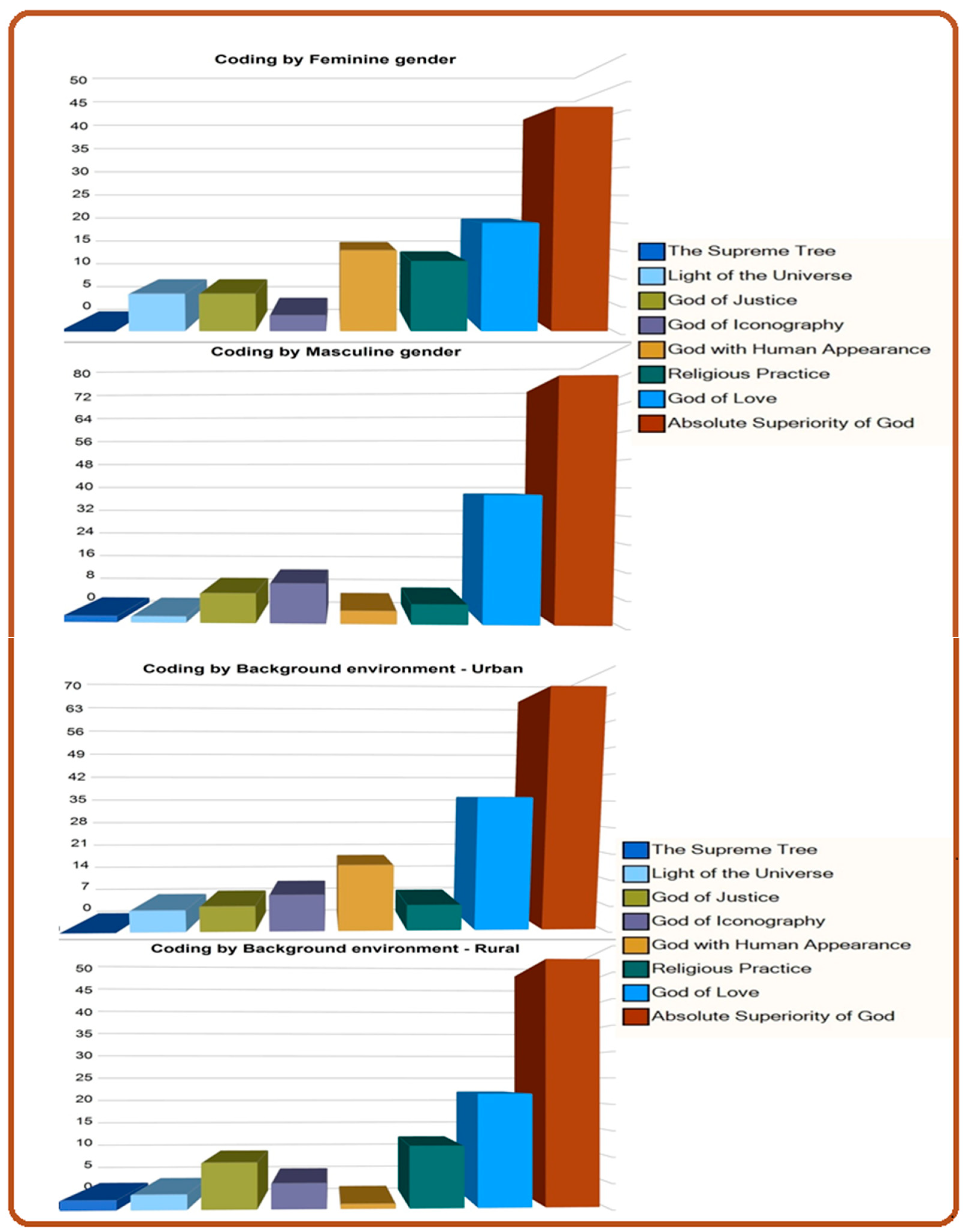

4.2. Gender and Background Differences in the Representation of God

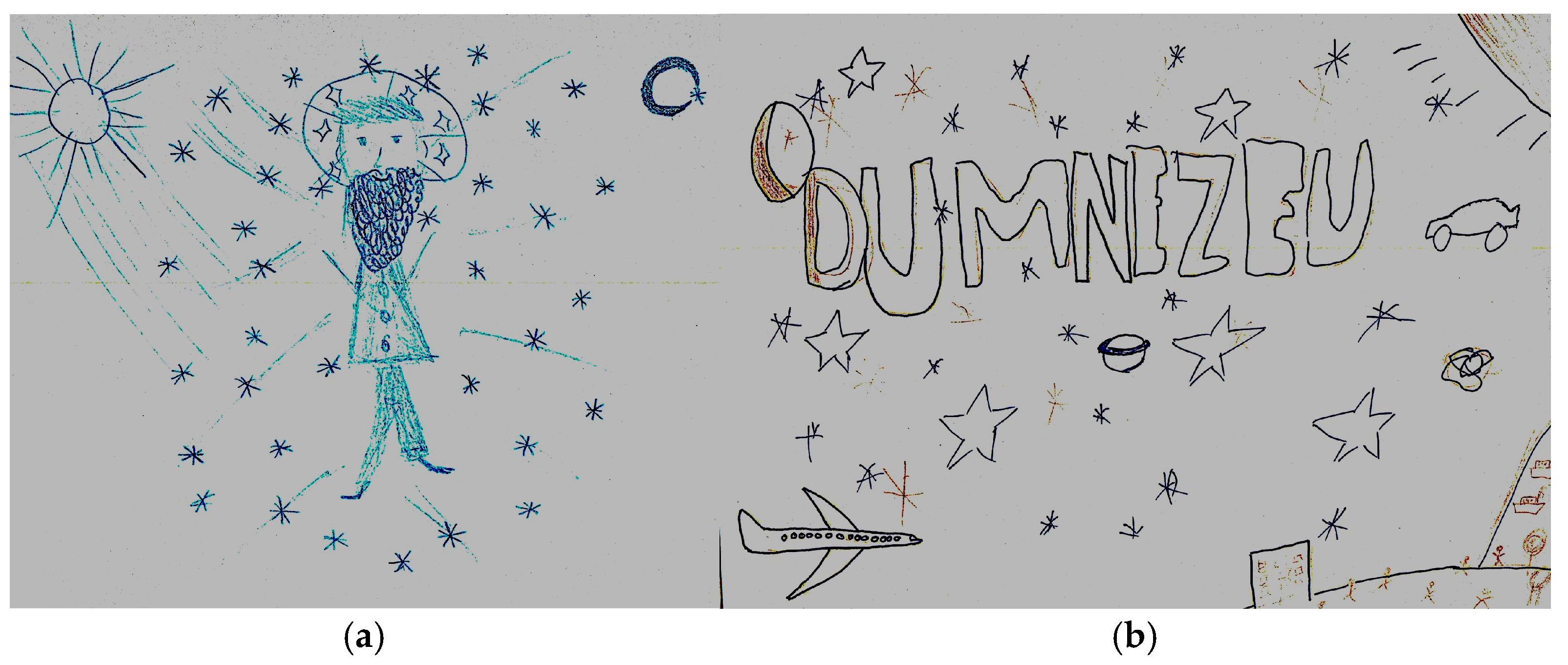

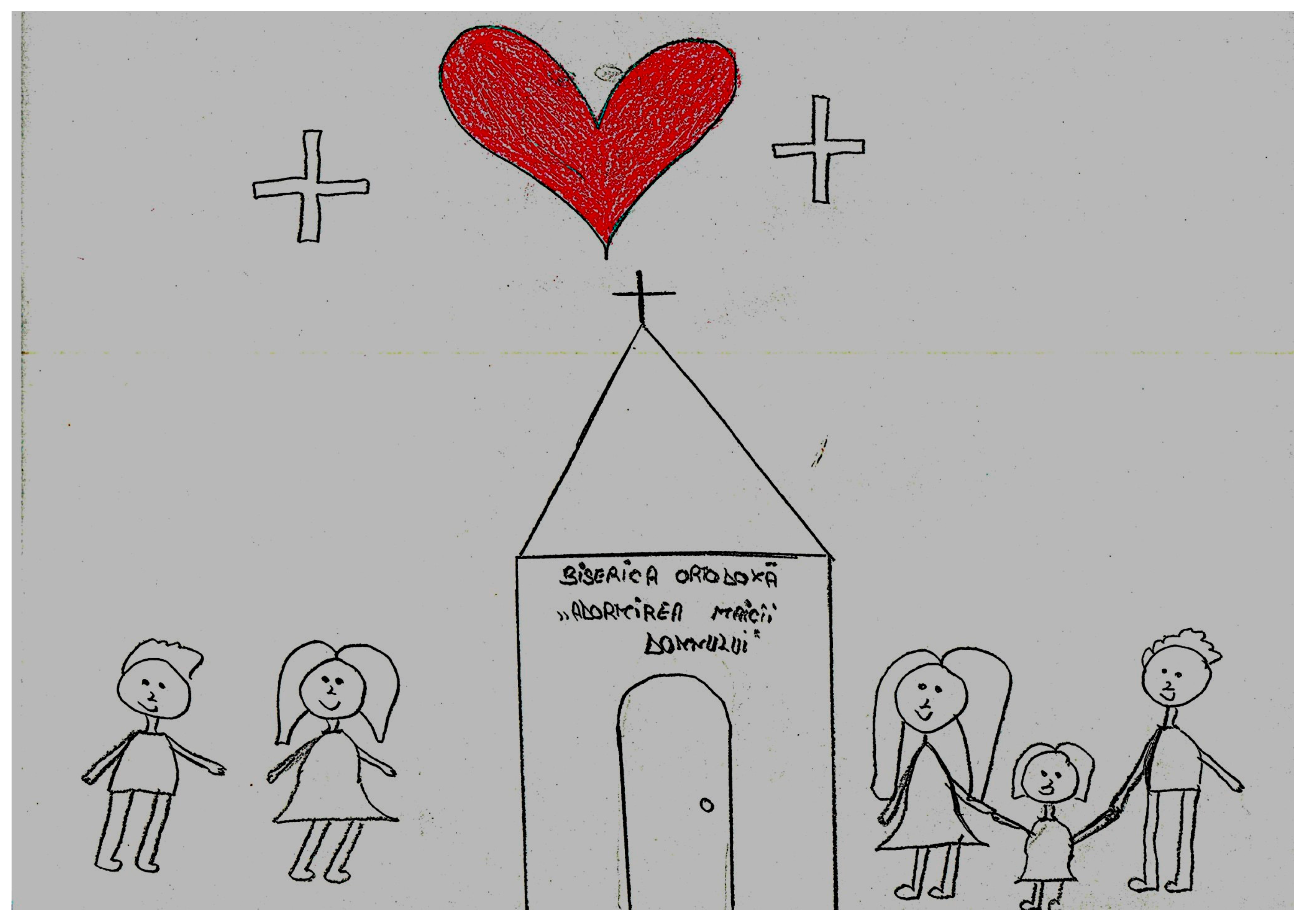

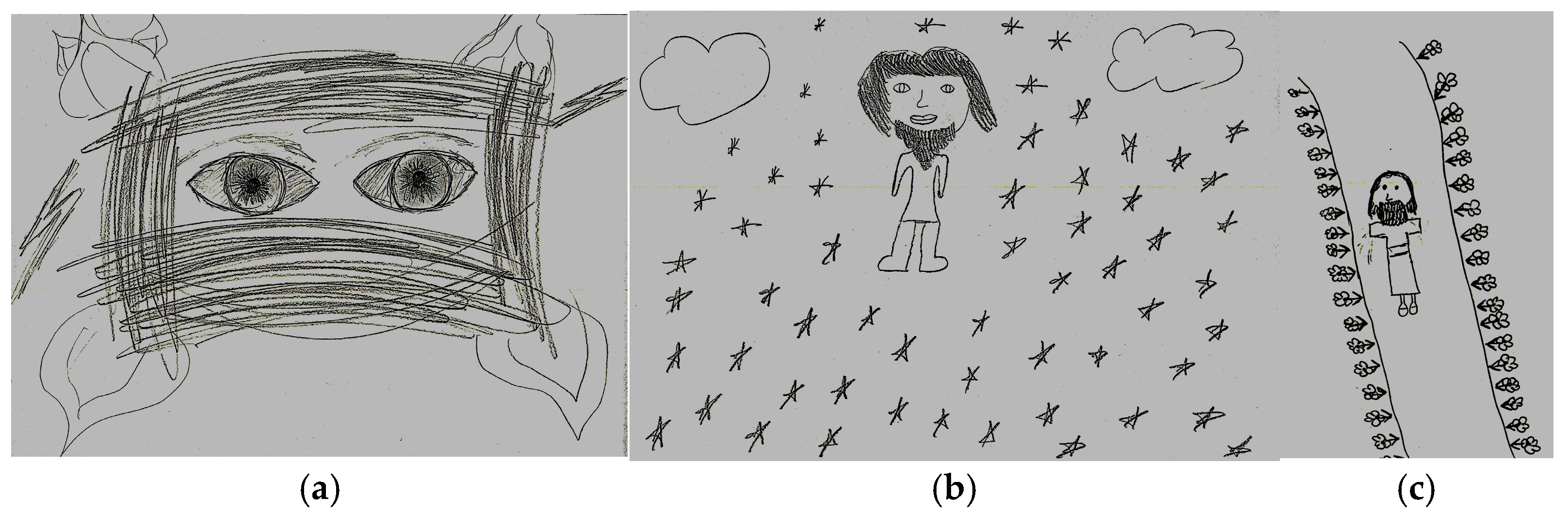

4.3. Observation Results

5. Discussion

5.1. The Canonical Dimension of Students’ Representation of God

5.2. Between Orthodox Theological Education and the Popular Religiosity of Romanians

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andrei, Petre. 1945. Filosofia Valorii. București: Fundația Regele Mihai I. [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge, William Sims. 2011. Atheism. In The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Edited by Peter Bernard Clarke. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 319–35. [Google Scholar]

- Basilica. 2024. Canonizarea Sf. Dumitru Stăniloae, o Bucurie Pentru Lumea Teologică: Se Reia Tradiția Primelor Secole. Available online: https://basilica.ro/canonizarea-sf-dumitru-staniloae-o-bucurie-pentru-lumea-teologica-se-reia-traditia-primelor-secole/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter Ludwig. 1999. The Desecularization of the World. A global overview. In The Desecularization of the World. Resurgent Religion and World Politics. Edited by Peter Ludwig Berger. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter Ludwig. 2005. Orthodoxy and Global Pluralism. Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 13: 437–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter Ludwig. 2012. Further Thoughts on Religion and Modernity. Society 49: 313–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chițescu, Nicolae, Todoran Isidor, and Petreuță Ioan. 2008. Teologia Dogmatică și Simbolică. Manual Pentru Facultățile Teologice. Cluj-Napoca: Editura Renașterea, vol. 1, p. 289. [Google Scholar]

- Churchpop. 2014. 10 Revealing Maps of Religion in Europe. Available online: https://www.churchpop.com/10-maps-religion-europe/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Ciobotea, Daniel. 2001. Confessing the Truth in Love: Orthodox Perception of Life. Mission and Unity. Iași: Trinitas. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, John. 2013. Secularizarea: Este ea Inevitabilă? Timișoara: Excelsior Art. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, Robert. 1990. The Spiritual Life of Children. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Trade and Reference. [Google Scholar]

- Conovici, Iuliana. 2009. Ortodoxia în România postcomunistă. Reconstrucţia Unei Identităţi Publice. Cluj-Napoca: Eikon, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cosmovici, Andrei. 1996. Psihologie Generală. Iași: Polirom. [Google Scholar]

- Culianu, Ioan Petru. 1994. Eros şi Magie în Renaştere. 1484. Bucureşti: Nemira. [Google Scholar]

- Curelaru, Mihai. 2006. Reprezentări Sociale. Iași: Polirom. [Google Scholar]

- Diel, Paul. 2002. Divinitatea Simbolul și Semnificația ei. Iași: Insitutul European. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbelaere, Karel. 2011. The Meaning and Scope of Secularization. In The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Edited by Peter Bernard Clarke. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 599–615. [Google Scholar]

- Dorondel, Ștefan. 2004. Moartea și Apa: Ritualuri Funerare, Simbolism Acvatic și Structura Lumii de Dincolo în Imaginarul Țărănesc. București: Paidea. [Google Scholar]

- Dueck, Al, Jeffrey Ansloos, Austin Johnson, and Christin Fort. 2017. Western Cultural Psychology of Religion: Alternatives to Ideology. Pastoral Psychology 66: 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliade, Mircea. 1991. Istoria Credinţelor şi Ideilor Religioase. Bucureşti: Editura Ştiinţifică. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, René, and Gianni Vattimo. 2009. Adevăr sau Credinţă Slabă? Convorbiri Despre Creştinism şi Relativism. București: Curtea Veche. [Google Scholar]

- Hamberg, Eva M. 2011. Unchurched Spirituality. In The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Edited by Peter Bernard Clarke. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 742–57. [Google Scholar]

- Harms, Ernest. 1944. The Development of Religious Experience in Children. American Journal of Sociology 50: 112–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herseni, Traian. 1977. Forme Străvechi de Cultură Poporană Românească: Studiu de Paleoetnografie a Cetelor de Feciori din Țara Oltului. Cluj-Napoca: Dacia. [Google Scholar]

- isjbrasov. 2024. Orientare în Carieră. Available online: https://www.isjbrasov.ro/orientare/index.php/liceal-vocational/specializare/teologic-45/teologie-ortodoxa-102 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Jung, Carl Gustav, and Jean Chiriac. 1998. Psihanaliza Fenomenelor Religioase. Bucureşti: Aropa. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl Gustav, and Jean Chiriac. 1999. Simboluri Ale Transformării. Bucureşti: Teora. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Yves. 2003. New Christianity, Indifference and Diffused Spirituality. In The Decline of Christendom in Western Europe 1750–2000. Edited by Hugh Mcleod and Werner Ustorf. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Linquist, Galina. 1997. Shamanic Performances on the Urban Scene: Neo-Shamanism in Contemporary Sweden. Stockholm: Stockolm University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lossky, Vladimir. 2010. Teologia Mistică a Bisericii de Răsărit. București: Humanitas. [Google Scholar]

- Meslin, Michel. 1993. Știința Religiilor. București: Humanitas. [Google Scholar]

- Mihu, Achim. 2000. Antropologie Culturală. Cluj-Napoca: Napoca Star. [Google Scholar]

- Mladin, Nicolae, Orest Bucevschi, Constantin Pavel, and Ioan Zăgrean. 2003. Teologia Morală Ortodoxă. Alba Iulia: Reîntregirea, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan, Gheorghe. 2022. Pedeapsa lui Dumnezeu între lege, dreptate și iubire. Altarul Reîntregirii XXVII: 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Moscovici, Serge. 1961. La psychanalyse, Son Image et Son Public. Paris: PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforova, Basia. 2017. Cultural and religious dimensions of the sacred and profane ambivalence: The Vilnius case. Studies in East European Thought 69: 153–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2012. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oişteanu, Andrei. 1989. Motive şi Semnificaţii Mito-Simbolice în Cultura Tradiţională Românească. Bucureşti: Minerva. [Google Scholar]

- Patriarhia. 2020. Lista unităților de învățământ teologic preuniversitar din Patriarhia română. Available online: https://patriarhia.ro/images/Educational2020/Lista_Seminariilor_si_Liceelor_Teologice_Ortodoxe_din_Patriarhia_Romana.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Pfister, Lauren Frederick. 2017. Ubication: A phenomenological study about making spaces sacred. International Communication of Chinese Culture 4: 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, Dumitru. 1996. Ortodoxie și Contemporaneitate. București: Diogene. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, Ioan Mihail. 1996. Istoria și Sociologia Religiilor. Creștinismul. București: Editura Fundației “România de Mâine”. [Google Scholar]

- Radosav, Doru. 1997. Sentimentul Religios la Români. Cluj-Napoca: Ed. Dacia. [Google Scholar]

- Recensământ România. 2021. Available online: https://www.recensamantromania.ro/rezultate-rpl-2021/rezultate-definitive/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Rorty, Richard, and Gianni Vattimo. 2008. Viitorul Religiei. Solidaritate, Caritate, Ironie. Pitești: Paralela 45. [Google Scholar]

- Roșculet, Gheorghe, and Daniel Sorea. 2021. Commons as Traditional Means of Sustainably Managing Forests and Pastures in Olt Land (Romania). Sustainability 13: 8012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotariu, Traian, and Petru Iluț. 2001. Ancheta Sociologica si Sondajul de Opinie: Teorie si Practica. Iași: Polirom. [Google Scholar]

- Rountree, Kathryn. 2014. Neo-Paganism, Native Faith and indigenous religion: A case study of Malta within the European context. Social Anthropology 22: 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2013. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore and Washington DC: Sage. First published 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Scârneci-Domnișoru, Forentina. 2016. Datele Vizuale în Cercetarea Socială. Cluj-Napoca: Presa Universitară Clujeană. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, Georg. 1969. The Metropolis and mental life. In Essays on the Culture of Cities. Edited by Richard Sennett. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice. Hall Inc., pp. 46–60. First published 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Sorea, Daniela. 2013. Two Particular Expressions of Neo-Paganism. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov, Series VII 6: 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sorea, Daniela. 2020. God, as the Children of Romania Draw It. In Visual Techniques Applied in Social Research. Edited by Florentina Scârneci-Domnișoru. Berlin: Peter Lang, pp. 229–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sorea, Daniela, and Codrina Csesznek. 2020. The Groups of Caroling Lads from Făgăraș Land (Romania) as Niche Tourism Resource. Sustainability 12: 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorea, Daniela, and Florentina Scârneci-Domnișoru. 2019. Unorthodox depictions of divinity. Romanian children’s drawings of Him, Her or It. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 23: 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorea, Daniela, and Ionuț Mihai Popescu. 2022. Glass Icons in Transylvania (Romania) and the Craft of Painting Them as Cultural Heritage Resources. Heritage 5: 4006–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorea, Daniela, Gheorghe Roșculeț, and Gabriela Georgeta Rățulea. 2022. The Compossessorates in the Olt Land (Romania) as Sustainable Commons. Land 11: 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stăniloae, Dumitru. 1991. De ce suntem ortodocşi. Teologie şi viaţă 67: 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Stăniloae, Dumitru. 1993. Iubirea Creștină. Galați: Porto-Franco. [Google Scholar]

- Stăniloae, Dumitru. 1996. Teologia Dogmatică Ortodoxă. București: Editura Institutului Biblic și de Misiune al Bisericii Ortodoxe Române, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, James. 1985. Without God, Without Creed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Roman R., and Kyle Whitehouse. 2015. Photo Elicitation and the Visual Sociology of Religion. Review of Religious Research 57: 303–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Bryan. 2000. Religia Din Perspectivă Sociologică. Bucureşti: Trei. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, Phil. 2014. Living the Secular Life: New Answers to Old Questions. New York: Penguin Press. [Google Scholar]

| Categories/ Subcategories | M | F | T | G | Total Codes | Categories/ Subcategories | M | F | T | G | Total Codes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Absolute Superiority of God | 68 | 37 | 94 | 11 | 105 | 4. God with Human Appearance | 4 | 13 | 15 | 2 | 17 |

| Almighty (of which) Miracles | 14 3 | 12 3 | 25 6 | 1 0 | 26 6 | Long beard | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Creator | 18 | 6 | 21 | 3 | 24 | Long hair | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Holiness | 4 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 8 | Powerful eyes | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Guide | 3 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 7 | Smiler | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Sovereignty | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 7 | Male | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Wise | 4 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 6 | Traces of wounds | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Infinite | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 6 | Elegantly dressed | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Perfection | 4 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 6 | Thin | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Holy Trinity | 6 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5. God of Iconography | 14 | 3 | 8 | 9 | 17 |

| Eternity | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | Cross | 9 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| Inconceivable | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | Angel | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Omnipresent | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | Aura | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| All-sustaining | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Trinity | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Invisible | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6. God of Justice | 9 | 7 | 14 | 2 | 16 |

| 2. God of Love | 44 | 26 | 67 | 3 | 70 | Law | 4 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Love | 17 | 6 | 20 | 3 | 23 | Testing people | 1 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Protection | 9 | 12 | 21 | 0 | 21 | Free will | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Goodness | 8 | 5 | 13 | 0 | 13 | 7. Light of the World | 2 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Gentleness | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 4 | The sun | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Mercy | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 4 | The yearning | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Forgiveness | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | Presence of God | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Patience | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 8. Supreme Tree | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 3. Religious Practice | 6 | 13 | 12 | 7 | 19 | ||||||

| Church | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 12 | ||||||

| Prayer | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||||||

| Cult of the dead | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Defta, M.; Sorea, D. Representations of Divinity Among Romanian Senior Students in Orthodox Theology Vocational High School. Religions 2025, 16, 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070839

Defta M, Sorea D. Representations of Divinity Among Romanian Senior Students in Orthodox Theology Vocational High School. Religions. 2025; 16(7):839. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070839

Chicago/Turabian StyleDefta, Monica, and Daniela Sorea. 2025. "Representations of Divinity Among Romanian Senior Students in Orthodox Theology Vocational High School" Religions 16, no. 7: 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070839

APA StyleDefta, M., & Sorea, D. (2025). Representations of Divinity Among Romanian Senior Students in Orthodox Theology Vocational High School. Religions, 16(7), 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070839