1. Introduction

Shamanic traditions have historically centered on the dynamic interaction between human agents and the spiritual realm. In Northeast China, ethnic groups such as the Manchu, Oroqen, Evenki, and Daur cultivated rich shamanic systems where shamans acted not merely as passive intermediaries but as active negotiators capable of influencing, commanding, and navigating spiritual forces. Through ceremonial performances, healing practices, and communal rituals, shamans exercised conscious will to secure blessings, avert disasters, and mediate between natural and supernatural domains. However, in the wake of modernization and socio-economic change throughout the twentieth century, traditional shamanic practices underwent substantial erosion, fragmentation, and ritual adaptation. These shifts have prompted critical questions about the resilience of indigenous religious expressions and the transformations of human agency under new historical conditions. The advent of digital technologies has introduced unprecedented spaces where cultural practices—including Shamanic traditions—are rearticulated, adapted, and performed. Platforms such as social media, video-sharing applications, and livestreaming sites have enabled the reappearance of discourses about Shamanism in highly mediated forms, reaching new audiences far beyond local communities. In this new environment, the exercise of human will—the intentional and assertive agency historically represented in Shamanic culture—is no longer confined to physical rituals but increasingly mediated through symbolic, visual, and narrative strategies online.

This study proposes that the concept of human will provides a critical perspective for understanding contemporary digital discursive practices. Human will has been extensively discussed across philosophy, theology, and psychology, where it is generally conceptualized as the faculty enabling intentional action, rational deliberation, and reflective agency.

Mele and González-Cantón (

2014), for instance, define human will as the capacity of individuals to actively select among possible actions rather than reacting passively to external stimuli. They distinguish between external freedom—the absence of coercion—and internal freedom—the autonomy of the will itself—arguing that genuine agency arises when individuals make deliberative choices despite constraints. From a historical-theological perspective,

Edelheit (

2008) explores Giorgio Benigno Salviati’s fifteenth-century analysis of will, emphasizing that human dignity is not merely grounded in intellect but in the capacity to direct one’s will toward moral and spiritual fulfillment. Across these dominant frameworks, human will consistently functions as a mediator between internal desires and external realities, enabling purposive engagement with the world. However, in traditional Shamanic belief systems in Northeast China, the conception of human will is different from these individualistic paradigms. The Shaman’s will is actualized through ritual acts that are not merely expressions of personal volition, but gestures of alignment with spiritual and communal responsibilities. In this cosmology, the will is dialogic and negotiated—it operates within a sacred framework in which individual intentionality is meaningful only insofar as it is harmonized with non-human agencies and ancestral obligations. This understanding positions human will not as a tool of self-determination, but as a ritualized faculty of interconnected agency—a medium through which spiritual, social, and ecological relationships are enacted and sustained.

Building upon this theoretical foundation, this study focuses on the discursive practices of digital participants engaging with Shamanic cultural representations on Douyin (Chinese TikTok). The primary analytic lens is the manifestation of human will in users’ linguistic choices, narrative framings, and symbolic appropriations. However, these contemporary discursive practices do not emerge in isolation. Digital participants’ ways of interpreting, affirming, parodying, or transforming Shamanic culture are informed by historical discursive representations that have constructed particular visions of human will associated with Shamanic traditions. Although the empirical focus remains on digital users, it must be acknowledged that earlier ethnographic records, mythological narratives, and historical accounts have established a discursive background wherein human will was a prominent theme within Shamanic cultural representations. These historical constructions are recontextualized and reconstructed within digital spaces. Thus, this study emphasizes the continuity of the discursive constructions of human will associated with Shamanic culture across different media—from oral ritual narratives, to written ethnographies, to digital platforms. This continuity does not imply the migration of Shamanic practitioners’ personal will, but rather concerns how representations of human will, historically embedded in discourses about Shamanism, are reinterpreted, adapted, and recontextualized in new media environments. Understanding this dynamic process is crucial for analyzing how contemporary digital participants engage with, modify, and contest inherited images of human agency within Shamanic cultural expressions.

Drawing on a corpus of approximately 293,284 tokens collected from Douyin between January 2020 and December 2024, this study investigates how human will manifests, evolves, and is contested within digital discourses about Shamanism. The corpus provides a robust empirical basis for tracing the symbolic and performative reconstruction of human agency across a wide array of digital practices and interactions. To address these dynamics, this research employs a mixed-method approach combining the Discourse-Historical Approach (DHA), virtual ethnography, and Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic modeling. The DHA provides a framework for analyzing the interrelations between historical contexts, discursive strategies, and power structures embedded in discourses about Shamanism. Virtual ethnography enables an in-depth exploration of community interactions within online platforms, capturing how cultural symbols are lived and negotiated digitally. Meanwhile, LDA topic modeling is utilized to uncover thematic structures across the corpus, revealing the underlying patterns and semantic fields through which human will and agency are articulated. These methods enable a comprehensive investigation into how traditional Shamanic concepts are transformed and persist in the digital era, offering new insights into the evolving articulation of human will in mediated cultural expressions.

2. Shamanic Conceptions of Human Will

In dominant philosophical and theological traditions, human will is typically conceptualized as an individual’s capacity for autonomous decision-making, rational deliberation, and purposive action. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), for instance, emphasizes moral autonomy, where the will functions independently of external influence and is governed by internal reason. Sun Zhengyu states that religion has supernatural properties and stems from human’s dependence on and comprehension of the natural world as a cultural phenomenon. Cosmological events can be personified into expressions of emotion or will (

Sun 2021, p. 99). Christian theological frameworks, in contrast, often frame the will as either aligned or misaligned with divine intention, embedding it within a teleological structure oriented toward obedience, salvation, or spiritual fulfillment.

Shamanic frameworks—particularly those rooted in the Northeastern traditions of China—advance a fundamentally ontological understanding of human will. Rather than construing will as an autonomous, internal faculty, these traditions conceptualize it as relational, cosmological, and intersubjective. Among ethnic communities such as the Manchu, Oroqen, Evenki, and Daur, the Shaman’s will is not an expression of individualized volition, but a spiritual commitment enacted through ritual in alignment with ancestral spirits, ecological forces, and communal responsibilities. Agency, in this context, is both deliberate and deferential; the will is not exercised against external constraints but negotiated within a sacred relational order.

This relational conception disrupts the modern dualism of internal versus external control. As stated above, while

Mele and González-Cantón (

2014) differentiate between external freedom (freedom from coercion) and internal freedom (autonomy of will), Shamanic cosmologies integrate both dimensions into a model of ritual will—a form of agency that is consciously exercised through symbolic action, yet inherently bounded by sacred obligations. In contrast to psychoanalytic models that treat desire as an unconscious force to be mastered, Shamanic traditions embed desire within broader ecological and cosmological systems, positioning the will not as repressed, but as ritually expressive and spiritually accountable.

While the views of Mele, González-Cantón, and Edelheit are useful for situating dominant Western understandings of will, they are not presented as interpretive lenses for the Shamanic context. Rather, they serve as a conceptual foil, against which the relational, communal, and cosmological conception of will in Northeast Chinese Shamanism can be more clearly articulated. In doing so, we underscore the importance of approaching Shamanic worldviews on their own terms, rooted in cosmologies rather than through externally imposed categories.

While the term human will is not an indigenous expression within Northeastern Shamanic traditions, we employ it here as a theoretical construct to capture a culturally embedded mode of agency—one that is ritually enacted, cosmologically ordered, and socially recognized. Rather than referring to an internal faculty of autonomous decision-making, human will in this context describes the way intentionality is generated through spiritual obligation, ancestral mediation, and ritual performance. This conceptualization does not emerge from abstract theorization but is grounded in ethnographic records that document how individuals are compelled—rather than voluntarily choose—to become shamans. For example,

Fu and Meng (

1991, p. 102) describe cases of ancestral spirit attachment, wherein the spirit of a deceased shaman possesses a living descendant, often manifesting as illness, trance, or mental disturbance. This condition is interpreted not as pathology but as the spiritual activation of lineage responsibility, obligating the individual to inherit sacred instruments and assume the ritual role. Similarly,

Tana (

1988) explains that shamanic rituals among the Daur arise as collective responses to ecological instability and communal affliction. The shaman, as a medium between human and spiritual realms, acts not through self-generated volition but through culturally assigned responsibility. In both accounts, human will is not an expression of internal autonomy, but a relational configuration of obligation shaped by ancestral expectations, ritual protocols, and cosmological structure. By using human will as an analytic category, this study redefines agency in Shamanic contexts as an enactment of sacred compulsion and ecological interdependence—moving beyond Western binaries of internal versus external freedom, and toward a culturally grounded ontology of will.

This alternative ontology of human will gains particular relevance in the context of digital media. On platforms such as Douyin, representations of Shamanic practice circulate widely, often blurring the boundaries between entertainment, reverence, and commodification. These mediated performances prompt debates over authenticity, agency, and cultural ownership. In such settings, human will is not simply manifested through individual expression or performative gestures, but through acts of cultural stewardship, ethical memory, and ritual adaptation. The will, once embedded in ritual space, is now partially reconstituted in digital discourse—no longer bound to the body of the Shaman alone, but diffused across networks of commentary, critique, and symbolic engagement.

Thus, Shamanic conceptions of will challenge prevailing paradigms of individual autonomy and instrumental agency. They invite a broader, more nuanced understanding of human will as relationally enacted, cosmologically grounded, and spiritually attuned. In tracing how these conceptions are preserved, transformed, and negotiated in digital environments, this study contributes to a more culturally sensitive and epistemologically plural account of agency in the digital age.

3. Northeast China’s Shamanic Traditions by Ethnic Context

Northeast China is home to several ethnic groups with rich shamanic traditions. This section reviews key findings for the major groups—Manchu, Oroqen, Evenki, and Daur—highlighting how each tradition has been characterized in prior studies.

The Manchu people, descended from the Jurchens, possess perhaps the most historically documented shamanic tradition in the region. This prominence is largely due to the legacy of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, which both preserved and institutionalized shamanic practices within its political and ritual frameworks. Since Qing dynasty, Manchu shamanism has developed into two distinct ritual systems: the commoners’ tradition (

jia folk rituals) and the imperial tradition (

tangse rituals) (

Fu 2021a, p. 99).

Fu (

2021a) outlines Manchu shamanism as comprising two distinct ritual systems: the commoners’ shamanic tradition practiced at the village or clan level, and the imperial shamanic tradition institutionalized within the Qing court. The folk rituals were conducted by clan-based shamans to address communal needs such as healing, childbirth, weather-related concerns, and ancestral or nature spirit worship. In contrast, imperial tradition was centralized in the Qing capital, with court shamans or the emperor himself officiating formalized tangse rituals at the Shamanic Temple, dedicated to the spirits of heaven and earth, natural deities, and the ancestors of the Aisin Gioro clan. Despite the Qing Empire’s transformation into a feudal dynasty,

Fu and Meng (

1991) emphasize that the emperors—from Nurhaci onward—continued to perform shamanic ceremonies, indicating the enduring significance of shamanic legitimacy to Manchu identity and rule.

Fu (

2021b) identifies several core features of Manchu shamanism, including a pantheon of ancestral, animal, and celestial spirits, the ceremonial use of drums and ritual songs, and the clan-based hereditary system for transmitting shamanic roles. One of the most emblematic representations of the Manchu shamanic worldview is

the Tale of the Nisan Shaman, which has been preserved in both Manchu and Chinese versions. This narrative recounts the story of a female shaman’s journey to the underworld to rescue a soul.

Meng (

1987) examined the historical dimensions of this epic, suggesting that it preserves ancient Jurchen shamanic beliefs. By 1940s, although some Manchu communities in remote areas of Heilongjiang and Jilin provinces in Northeast China still practiced shamanism to varying degrees, the belief in shamanism among the Manchu people as a whole had already entered a stage of decline (

Zhang 2005, p. 172). Only fragments of clan shamanic practice survived clandestinely in some rural areas, but researchers observed revival efforts. Manchu rituals have been increasingly reconstructed and staged for cultural festivals and tourism at sites such as the Shamanic Joy Park in Changchun and the Nayin Tribe Resort at Changbai Mountain. These events, though visually elaborate, often involve compensated indigenous actors and are primarily designed for external audiences rather than internal spiritual communities, indicating limited continuity with traditional religious functions (

Qu 2024). Although Manchu shamanism coexisted with Buddhism and Daoism, adopting elements from each, yet it retained a distinct identity centered on ancestral worship and the human will of the shaman to command spirits for the community’s benefit.

The Oroqen have a similarly rich shamanic heritage, deeply influenced by their history as forest hunters. Oroqen shamanism is characterized by a variety of rites honoring nature spirits (sun, moon, stars, mountains, rivers, etc.) and by the prominent role of female shamans. In traditional Oroqen belief, every shaman is a spirit-medium who can communicate with gods to heal, avert disaster, and guide the community. Notably, all early Oroqen shamans were women, a fact reflecting the tribe’s matrilineal origins (

Editorial Team of A Brief History of the Oroqen Nationality 2008). Throughout the 20th century, Oroqen shamanism has seen dramatic change, especially after modern education. According to the field study of

Guan and Wang (

1998), until the 1950s, Oroqen life was still largely at the end of primitive society, with hunting as the main livelihood. At that time Oroqen shamanism “flourished and remained quite primitive” in form. Many of the shamanic deeds that are still remembered by people today are legends from that period. Oroqen traditional shamanism is characterized by its venerable history and ceremonial richness, a domain where female shamans formerly held sway over the tribe’s collective spiritual sphere. With the advent of modernity and the consequent transformations in modes of dwelling and living, the majority of these traditional rites have progressively diminished. What was once a shamanic faith deeply intertwined with the natural world of forests and mountains now persists primarily in the form of fragmented customs and symbolic representations.

As the only ethnic group in China traditionally reliant upon reindeer husbandry for their livelihood, the Evenk’s economic base, combining hunting and pastoral activities, fostered the development of their unique shamanic culture (

Man 2010). In Evenki cosmology, everything has a spirit: they worship nature and animals as totems, and shamanism forms the core of their religious life. A typical Evenki shaman serves as the essential mediator between humans and the spirit world. Although the bear was the totem animal worshipped by the ancient Evenk, their reverence was primarily expressed through specific naming conventions, taboos, and air burial ceremonies. According to Man’s field research, hunting bears held special ritual significance: the Evenki practiced elaborate sky-burial ceremonies for hunted bears, treating the bear as a sacred totem. All members of the Ulileng (an Evenk family commune composed of blood relatives) participated, pretending to cry bitterly during the ritual to show respect and sorrow for the bear’s spirit. Even today some Evenki maintain portions of the traditional bear burial rite and its associated taboos (

Man 2010, p. 69). Since modern times, Evenk shamanic traditions have undergone changes through contact with external religions, yet they have not been entirely supplanted. Eastern Siberian influence is evident: some Evenki communities adopted elements of Orthodox Christianity (e.g., celebrating Easter and using icons and crosses at weddings and burials), and others were affected by Tibetan Buddhism (for instance, using Buddhist priests for funeral rites) (

Wu 1988). However, these external elements often modified only rituals and did not replace core beliefs. Evenki themselves insist that shamanism is still the most important religion in their culture. Village elders warn that those who “lose their roots” by abandoning shamanism are doomed (

Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Editorial Group 2009). Overall, the contemporary religious landscape of the Evenk people is characterized by pluralism and coexistence. Within their daily spiritual lives, shamanic practices continue to exert a dominant influence (

Wu 1988, p. 60). Although villages no longer feature full-time shamans for each clan as was customary in the past, and many younger individuals seek shamanic consultation only occasionally—primarily during ritual festivals or times of illness—the Evenk still regard shamans as a crucial bridge for maintaining tradition and their relationship with the natural world.

The Daur people have long-standing shamanic traditions that historically played a central role in their spiritual life. In traditional Daur belief, shamans were regarded as authoritative mediators between humans and the spirit world (

Morigendi 1988). The Daur term for a shaman is Yadegen for males or females and Otoshi for females (

Wulisi 1988). According to Morigendi’s field research, Daur shamans were entrusted with powerful soul-capturing abilities: they could intercede with spirits to avert disasters and bring blessings to the community. Because of this role, shamans were especially revered in Daur society. The Daur recognized two categories of shamans: those possessed by deities (the Yadegen and Otoshi) and those not possessed (serving more as assistants). A Yadegen was a clan-member chosen as a spirit-medium for clan ancestral or guardian deities, and would be invited to preside over major rituals. In Daur culture, every clan possesses its own ancestral spirit, and each of these spirits is associated with a legend explaining its origin (

Tana 1988, p. 157). A Otoshi (“divine lady” shaman) represented a goddess and did not need to belong to a specific clan, though her ritual rank was slightly lower than the Yadegen. Male assistants called Bagqi supported the Yadegen in smaller ceremonies, and Barixi served as lay healers (e.g., treating injuries), but did not have deities of their own (

Morigendi 1988, p. 141). Daur shamanism was structurally rich: shamans were the community’s spiritual leaders, mediating with a pantheon of spirits on behalf of the people. Over time, Daur shamanic practice has undergone significant change. With socio-economic development and modernization, traditional Daur shamanism has weakened substantially. According to

Yi et al. (

2007), improved healthcare and education led many Daur to turn to hospitals and modern remedies instead of shamanic rites for illness. As a result, the once-extensive pantheon of Daur deities has shrunk: many spirits once regularly worshiped are no longer venerated, and household altars have disappeared from numerous homes. The field research of Yi et al. reports that in today’s settled Daur villages, few families even maintain images or statues of shamanic gods, and many younger families no longer perform ancestral rituals for them. Correspondingly, the number of practicing shamans has plummeted. Whereas older villages used to have resident Yadegen and their helpers, modern surveys find that many villages now have none at all. The Daur’s traditional shamanic influence in daily life has been greatly eroded: its scope has narrowed, and its social role has been greatly diminished. Nonetheless, even with these changes, Yi et al. note that a vestigial respect for the old shamanic worldview persists in some form, though it is no longer the dominant force it once was. The Daur originally possessed a rich shamanic culture with specialized spirit-mediums mediating with nature and ancestor spirits for the community’s welfare. Over the modern period, however, these traditions have markedly transformed: many rituals fell into disuse, the shamanic pantheon contracted, and shamans themselves all but disappeared as scientific medicine and new cultural norms took hold.

While existing studies on Manchu, Oroqen, Evenki, and Daur shamanic traditions have made significant contributions, several limitations are apparent. First, most research has emphasized the decline of traditional practices under the forces of modernization, often overlooking how these traditions adapt and transform in contemporary contexts. Second, the majority of studies are grounded in fieldwork conducted within physical communities, with limited attention to the emergence of shamanic expressions in digital environments. Third, although previous research acknowledges the shaman’s role as an intermediary between the human and spirit worlds, it has not systematically theorized the notion of human will as a central element of human will. These limitations suggest the need for a new analytical perspective that considers how digital media afford spaces for the reconstruction and articulation of human will and human intentionality.

4. Virtual Ethnography

Virtual ethnography, as initially theorized by

Hine (

2000), emerged as an adaptive methodology to address the challenges posed by online interactions. Rather than treating the Internet merely as a technological tool, Hine argues that it constitutes both a cultural artifact and a cultural space, requiring ethnographers to engage with it as a site of meaning-making. The field site in virtual ethnography is not pre-given but is instead constructed through the researcher’s following of connections, interactions, and narratives across online contexts. Building upon Hine’s foundation,

Miller and Slater (

2000) further challenged the then-dominant idea of a detached “cyberspace”. In their ethnographic study of Internet use in Trinidad, they emphasized that online activities are embedded within and continuous with offline social realities. They demonstrated that the Internet is localized, culturally specific, and deeply entangled with everyday practices, thereby rejecting any simplistic dichotomy between the virtual and the real.

Subsequent studies have expanded and operationalized virtual ethnography across various platforms and communities.

Steinmetz (

2012), for instance, focused on online message boards, identifying three major methodological challenges: negotiating space and time, constructing identity and authenticity, and addressing ethical dilemmas. He notes that because the Internet collapses traditional notions of time and space, researchers must reconsider the boundaries of their field sites and their relationships to participants.

Darwin (

2017) applied virtual ethnography to investigate nonbinary gender identities within a Reddit community. Through discourse and content analysis, she revealed how participants engaged in the “doing”, “redoing”, and “undoing” of gender, navigating a binary-dominated cultural system. Darwin’s research illustrates that virtual ethnography can provide access to marginalized voices and emergent social practices that may be difficult to capture through traditional offline ethnographic methods. Similarly,

Gillen (

2009) introduced the concept of “virtual literacy ethnography” in her study of Schome Park within Teen Second Life. She synthesized ethnographic methods to examine literacy practices across multiple domains, including chat logs, wikis, and forums. Gillen’s work emphasizes that online ethnographic research must attend to multimodal communication and the hybridization of old and new literacy forms, particularly when studying youth engagements in virtual worlds.

In light of the foregoing discussions, virtual ethnography offers a particularly appropriate methodological framework for this study, which examines discourse about Shamanism rather than discourse produced from within Shamanic communities themselves. This distinction is crucial: the dataset comprises user-generated commentary responding to representations of Shamanic elements on Douyin, reflecting public interpretations, appropriations, and contestations of Shamanic culture, rather than authentic ritual discourse or the perspectives of practicing shamans. Consequently, the analysis focuses on mediated discursive practices—how human will, as a culturally and spiritually charged concept, is constructed and negotiated in digital interactions by lay users engaging with Shamanic imagery.

Given the dynamic, multimodal, and translocal nature of contemporary online platforms such as Douyin, conventional fieldwork methods are inadequate for capturing the dispersed, performative, and interdiscursive nature of this kind of cultural reconfiguration. Virtual ethnography enables sustained engagement with symbolic performances, narrative framings, and community interactions that unfold in real-time, albeit asynchronously, within algorithmically shaped digital ecosystems. Rather than accessing emic perspectives through participant observation among ritual communities, this study uses virtual ethnography to examine how representations of Shamanism are received, reinterpreted, and resignified by online publics. In this context, human will—traditionally embodied through ritual—is digitally reconfigured, becoming a contested site of cultural memory, identity, and affective investment.

However, a methodological limitation must be acknowledged: the identities of the Chinese TikTok users who contribute to these discourses remain fundamentally indeterminate. Due to the nature of the platform—where usernames are pseudonymous and personal backgrounds are rarely disclosed—it is not possible to distinguish whether a commentator is a trained Shamanic practitioner, an untrained believer, a cultural participant, or a casual observer. This ambiguity makes demographic classification impractical and potentially misleading. Accordingly, this study adopts a discourse-centered approach that treats all comments as discursive artifacts rather than as direct reflections of biographical identity. Our analytic focus remains on the cultural logics, symbolic framings, and rhetorical strategies that circulate within these comments. While this limits our ability to assign intention or authority to individual voices, it allows for a broader understanding of how discourses about Shamanism—and the concept of human will—are socially constructed and contested in the digital public sphere.

5. Research Methods

This study draws on user-generated textual content from Douyin, a widely used short-video platform in China characterized by high user engagement and algorithmically curated content distribution. Douyin’s recommendation system—shaped by user behavior indicators such as viewing time, likes, comments, and shares—impacts the prominence and visibility of particular videos and comment threads. While acknowledging this algorithmic mediation, the present study treats it as a contextual background rather than a direct object of analysis. To mitigate selection bias, data collection spanned a wide temporal range (1 January 2020, to 6 December 2024) and drew from 210 videos tagged with “Northeastern tourism” and “Northeastern Shamanic culture.” These videos primarily include staged performances, festival rituals, and cultural documentaries that frame Shamanism as a feature of local heritage. Importantly, the analyzed comments are authored not by shamans or ritual insiders, but by general users reflecting on these mediated representations. As such, the data constitute a form of public discourse about Shamanism, offering insight into how non-specialist audiences interpret, valorize, parody, or critique Shamanic symbols and practices.

The final dataset, the Northeast Shaman Corpus (NES), comprises 293,284 tokens and 25,973 unique types. Standard text preprocessing procedures—including word segmentation, stop-word removal, and noise filtering—were implemented to enhance data quality. This dataset forms the empirical foundation for exploring how human will is symbolically invoked and debated within digital commentary.

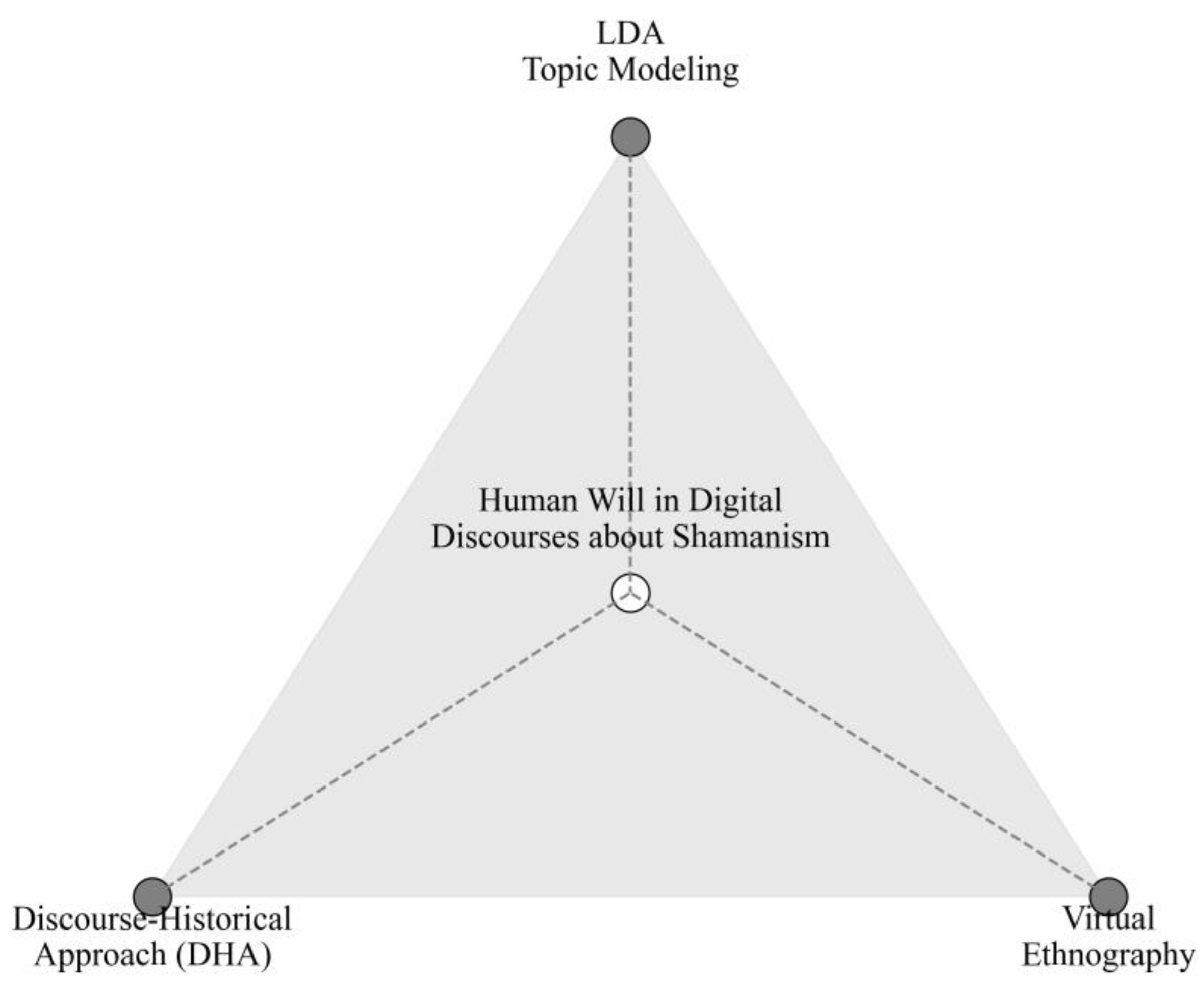

To address these questions, a triangulated methodological approach was employed, integrating Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic modeling, the Discourse-Historical Approach (DHA), and virtual ethnography (

Figure 1). First, LDA topic modeling was used to extract the dominant thematic structures within the NES corpus, identifying clusters of discourse topics embedded in user comments. Coherence and perplexity metrics informed the optimal number of topics for interpretability. Importantly, the LDA results served primarily as a scaffold for deeper qualitative analysis, not as an end in themselves.

Second, the Discourse-Historical Approach (DHA) was applied to explore how Shamanic traditions are discursively constructed, framed, and evaluated by users. DHA’s emphasis on intertextuality and socio-political context enables a critical analysis of how users mobilize historical references, topoi, and identity constructions when engaging with discourses about Shamanism. KH Coder was used to support this analysis, enabling the detection of co-occurrence networks, lexical patterns, and semantic clusters that illuminate key discursive strategies.

Third, virtual ethnography provides the overarching methodological orientation. Following

Hine’s (

2000) framework, this study treats online user comments not simply as data points, but as cultural artifacts embedded in specific social contexts. Ethnographic immersion was achieved through sustained engagement with comment sections, thematic trends, and interactional norms over time. While this study does not include interviews or direct participant observation, it treats user discourse as performative cultural practice—where beliefs, affect, and evaluations concerning Shamanic culture and human will are continuously enacted and negotiated in real time.

By foregrounding digital representations and user commentary as its empirical focus, this research avoids essentializing Shamanic belief and instead emphasizes the mediated, discursive processes through which Shamanism is reimagined in contemporary Chinese digital culture. The triangulated methods offer a comprehensive lens for understanding how human will—historically embedded in ritual—is now rearticulated through commentary, critique, and cultural participation in online spaces.

The integration of LDA topic modeling, discourse-historical analysis, and virtual ethnography constitutes a methodological triangulation strategy that enhances both the credibility and depth of the study. LDA modeling provides a quantitative overview of the thematic landscape; DHA offers critical, context-sensitive interpretations; and virtual ethnography situates these discursive patterns within the lived practices of digital communities. This triangulated approach enables a comprehensive exploration of how human will is maintained, transformed, and rearticulated within digitally mediated shamanic discourse.

6. Findings and Discussion

6.1. Framing of Shamanic Traditions Through LDA Topic Analysis

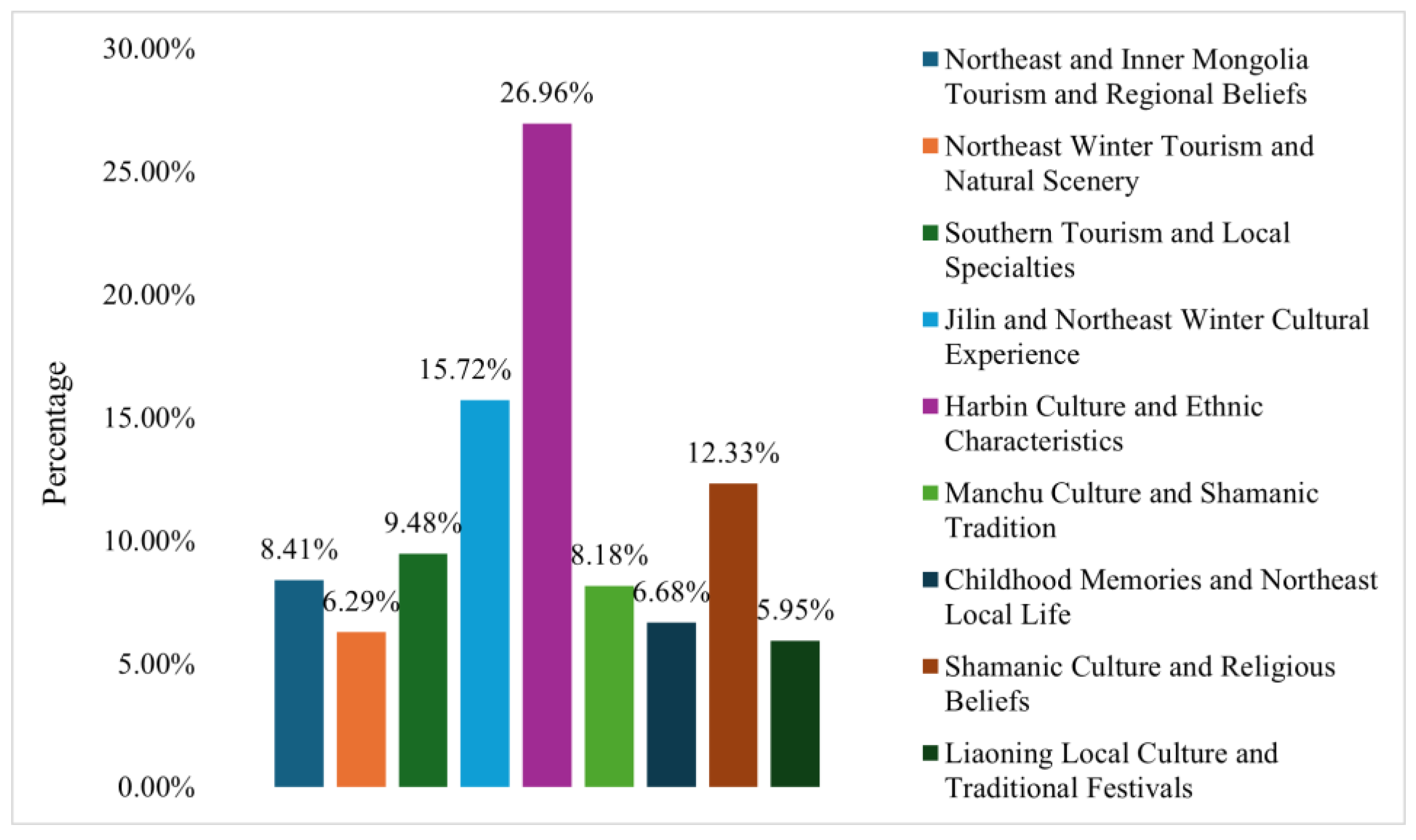

After analyzing coherence scores, perplexity, and visual results, the optimal number of topics for machine training was determined to be nine (

Figure 2). Based on the keywords output-ted by the visualization results, the nine main themes of the NES corpus were summarized (

Figure 3).

To clarify the multitude of themes emerging from the LDA model, this study reorganizes the nine original topics into three broader categories: (1) intentional preservation of cultural-spiritual heritage, (2) affirmation of communal identity and belonging, and (3) strategic adaptation and negotiation of traditions in modern contexts. This restructured categorization emphasizes how individuals and communities relationally, cosmologically, and ritually articulate, assert, and negotiate human will in the digital representations of Northeast China’s Shamanic culture.

(1) Intentional Preservation of Cultural–Spiritual Heritage: Two topics—Manchu Culture and Shamanic Tradition (8.18%) and Shamanic Culture and Religious Beliefs (12.33%)—together reflect a relational and cosmological commitment to upholding sacred traditions. These discussions center on ancestral rituals, spiritual cosmologies, and enduring indigenous beliefs about human will. In these traditions, the will is a sacred relational force enacted through ritual practices aligned with ancestral spirits and ecological systems. Commenters frequently invoke ritual mediation and ancestral worship, expressing an intentional commitment to maintaining the sacred foundations of Shamanic practice. This discourse suggests that community members see themselves as custodians of Shamanic heritage, exercising their human will to preserve and continue these practices in contemporary life. Although these explicitly spiritual topics constitute a modest portion of the overall corpus, they are pivotal in illustrating deliberate preservation efforts. They demonstrate that even amid rapid change, many participants actively assert the importance of Shamanic ritual willpower and guidance in fostering communal well-being. In the digital space, this translates to a conscious continuity of sacred relationality—a clear indication that the core spiritual dimension of human will in Shamanic culture remains vibrant and influential through the intentional actions of its adherents.

(2) Affirmation of Communal Identity and Belonging: The second category reflects the relational will to affirm and celebrate a regional cultural community. Harbin Culture and Ethnic Characteristics (26.96%) emerges as the most dominant single theme, underscoring the centrality of regional identity in the discourse. Commenters celebrate Harbin’s diverse cultural landscape, winter festivals, and historical legacy, effectively asserting a proud communal identity. Similarly, Liaoning Local Culture and Traditional Festivals (5.95%) highlights local fairs, rituals, and communal events that, even when not explicitly labeled as Shamanic, create a cultural atmosphere where spiritual traditions can quietly persist. Additionally, Childhood Memories and Northeast Local Life (6.68%) reveals an emotional dimension of human will to connect with heritage: users recount folk customs and childhood experiences, often implicitly referencing Shamanic or folk-religious elements interwoven into everyday life. Collectively, these topics illustrate the intentional integration of Shamanic elements into a broader regional narrative. The community’s relational will to belong is evident in how people invoke shared memories and symbols to reinforce regional pride and social bonds. In this way, digital discourse becomes a space for actively constructing identity—individuals exercise their human will by affiliating with a cultural heritage, ensuring that Shamanic motifs and values remain integral to communal belonging and a source of collective meaning in Northeast China.

(3) Strategic Adaptation and Negotiation in Modern Contexts: The third category highlights how Shamanic culture is relationally and cosmologically adapted and negotiated within the realm of tourism and commercialization. Several topics fall under this dimension: Jilin and Northeast Winter Cultural Experience (15.72%) points to popular winter festivals and cultural activities where Shamanic customs are staged or referenced as attractions. Northeast and Inner Mongolia Tourism and Regional Beliefs (8.41%) and Northeast Winter Tourism and Natural Scenery (6.29%) reflect how local beliefs, practices, and even landscapes are deliberately packaged for visitor consumption. Another theme, Southern Tourism and Local Specialties (9.48%), indicates that audiences compare Northeast China’s cultural offerings with those of other regions, suggesting a conscious positioning of Shamanic heritage within a broader national tourism market. Across these topics, we see commenters decision-making at work: there is a collective human will to reinterpret and showcase traditional culture in ways that appeal to tourists. This adaptation, however, is not without tension. Comments often hint at negotiations between maintaining authenticity and pursuing commercial appeal. For instance, users discuss the balance between preserving the integrity of Shamanic rituals and modifying them as performances for festivals or scenic exhibitions. Such discourse reveals an acute awareness that cultural heritage is being reshaped by modern economic forces, and participants are actively weighing what is gained or lost in the process. The prominence of tourism-related themes shows that adapting heritage for economic and entertainment value is a significant concern and endeavor. Yet, the very act of discussing these adaptations is itself an assertion of relational human will: local communities and viewers critically engage with how their traditions are used, thereby exercising a form of collective will over the narrative and value of Shamanic culture in contemporary society.

By recasting the LDA results into these dimensions of relational, cosmological, and ritual human will, this study clarifies the discursive construction of intentionality in Northeast China’s digital discourses about Shamanism. Rather than viewing the online commentary as a disparate set of themes, we now see a coherent picture of relational human will at work in a context shaped by cultural heritage, regional representation, and tourism dynamics. The intentional preservation of sacred traditions, the affirmation of communal belonging, and the strategic adaptation of cultural practices to new realities each emerge as key threads in the tapestry of discussion. Together, they demonstrate that participants in this discourse are not passive observers but active decision-makers—constantly negotiating what Shamanic heritage means and how it should be carried forward. This structured analysis illuminates how, in the interplay between maintaining heritage authenticity, celebrating regional identity, and embracing or resisting commercial forces, the concept of Shamanic human will is both the driving force and the product of these conversations. In sum, digital representations of Shamanic culture in Northeast China serve as a dynamic forum where individuals and communities articulate their human will: they preserve what they deem sacred, assert who they are, and strategize how to face the future. This nuanced understanding underscores the powerful role of relational human will in sustaining and reimagining cultural traditions amid changing social and economic currents.

6.2. Discursive Strategies in Shaping the Representation of Shamanism

Using the Discourse–Historical Approach (DHA), the study reveals how specific discursive strategies shape the representation of Shamanism, positioning it within broader backgrounds about tradition, modernity, and cultural identity. The DHA (Discourse–Historical Approach) focuses on five major discursive strategies: nomination, predication, argumentation, perspectivization, framing or discourse representation and intensification/mitigation strategies (

Reisigl and Wodak 2014). Due to space limitations, this section will only analyze the linguistic expressions of the nomination, predication, and argumentation that illustrate how traditional ecological and sacred narratives are rearticulated in contemporary discourse.

6.2.1. Nomination Strategy

The nomination strategy focuses on identity construction, which is expressed in language through nouns and verbs that modify participants, events, or actions. This study uses “Shaman” as the search term and collected 885 concordance lines. The corpus was then filtered for nouns that modify “Shaman”, resulting in a total of 274 lines. These lines were further categorized to summarize the constructed image of the Shaman, as shown in

Table 1.

By calling shaman a primitive or earliest faith, digital discourses root shamanic identity in deep history. This naming pattern reveals a collective will to establish legitimacy: it frames contemporary shamans as inheritors of a venerable lineage and positions human will as linked to that history. In invoking epochal time—“nearly 10,000 years” of tradition—the discourse constructs human will as both continuous and predestined. This framing emphasizes that human will is not simply individual autonomy, but a relational force that connects practitioners to ancestral traditions and sacred cosmologies. It evokes human intentions to honor ancestors, even as it constrains modern practitioners within a narrative of ancient inevitability. Other nomination choices highlight the content of faith: words like “the most primitive beliefs of nomadic peoples”, “reverence and fear of nature, living beings, and death”, and simply “deities”. These terms frame shamans as embodiment of elemental belief, emphasizing how human willfulness is directed toward unknown powers, suggesting that human will is directed toward negotiating with unknown powers rather than asserting dominance over them. Naming shaman in terms of “reverence” or “fear” reflects the humility and ritual obligation central to human will, which is embedded within a cosmological order larger than the self.

Many labels cast the Shaman in active, often institutional roles. Terms like “magician”, “high priest”, “mediator between the underworld and gods”, “wizard”, and “sacrificial profession” dominate this category. These nominations ascribe strong agency: a shaman is someone who deliberately intercedes with spirits (“mediator”) or wields supernatural skill (“magician”, “wizard”). However, these roles also highlight the structured and duty-bound nature of human will. The term “sacrificial profession”, for instance, suggests that human will is not purely self-determined but is enacted through ritualized obligations to the community and sacred forces. Simultaneously, the translation of local concepts into globally recognized archetypes (e.g., calling a shaman a “wizard”) negotiates identity for diverse audiences. This cross-cultural naming reflects an intention to universalize human will while simultaneously constraining it within socially prescribed roles. By emphasizing the shaman’s function in mediating between spiritual and communal realms, these terms underscore that human will is relational and shaped by collective expectations.

Another pattern emphasizes actions over personhood. Labels such as “witchcraft” and “shamanic ritual dance” focus on what shamans do. These terms signal that will is performed through ritual: the human will is enacted in ceremonies and magic. For instance, invoking “shamanic dance” highlights deliberate practices that realize supernatural interaction, positioning human will as an embodied and performative force that negotiates with sacred powers. However, the use of “witchcraft” reflects outsider perspectives that exoticize or marginalize these acts, framing them as deviant or irrational. Such naming reduces human will to spectacle, erasing its relational and cosmological dimensions.

The largest category of terms connects Shamanism to collective identity. Words like “culture”, “our folklore”, “cultural heritage”, and even “our Northeast” appear frequently. These names tie human will to communal and regional belonging. By framing shamans as “our folklore” or part of “cultural heritage”, these labels construct human will as an expression of collective identity rather than individual will. It also reflects negotiation with state and tourism discourses: by labeling Shamanism as cultural heritage, digital texts often align it with official narratives about ethnic and regional culture. While this alignment can empower shamans by granting them cultural significance, it simultaneously subsumes their personal agency under a broader narrative of communal pride and cultural preservation. The possessive “our” in “our Northeast” emphasizes that shamans are claimed by the community, suggesting that human will is seen as an expression of regional pride. Thus, human will is portrayed as relationally enacted, serving the collective will of the community and reinforcing cultural identity.

In contrast, some naming patterns reflect opposition. Labels like “feudal superstition” and “mass hysteria” are negative. These terms reveal the intentions of detractors who seek to discredit shamanism. By calling shamanism “superstition”, critics exercise a intention to delegitimize it. This naming severs human will from its sacred and relational contexts, reducing it to irrationality or backwardness. Such naming constrains the shaman’s identity by painting it as backward or extreme. While other categories ascribe sacred power to shamans, this one strips it away. The presence of this discourse shows that naming is contested—the same identity can be framed either as heritage or as superstition depending on who wields the label. Furthermore, gendered naming is notable. Phrases such as “Female”, “Grandmother”, and “Elderly women” repeatedly appear. This indicates that in digital discourse shamans are often seen as elder women. These labels highlight the intersection of gender, age, and agency in shamanic practice. On one hand, they recognize the spiritual authority of elder women, suggesting a community’s will to empower matriarchal figures. On the other hand, they constrain human will by implying that only certain women—those who fit specific age and gender norms—are legitimate bearers of this sacred role. This reflects how human will is shaped by cultural expectations and relational hierarchies.

In summary, the naming practices in digital discourses about Shamanism reveal that human will is deeply relational, cosmological, and ritualized. Each category of noun phrases embeds the shaman’s identity within networks of meaning and power. Whether framing shamans as inheritors of sacred traditions, active mediators, or cultural symbols, these labels construct narratives that shape public perceptions of human will. By emphasizing relationships with community, sacred forces, and cultural identity, these naming practices highlight the interconnected and non-autonomous nature of shamanic will.

6.2.2. Predication Strategy

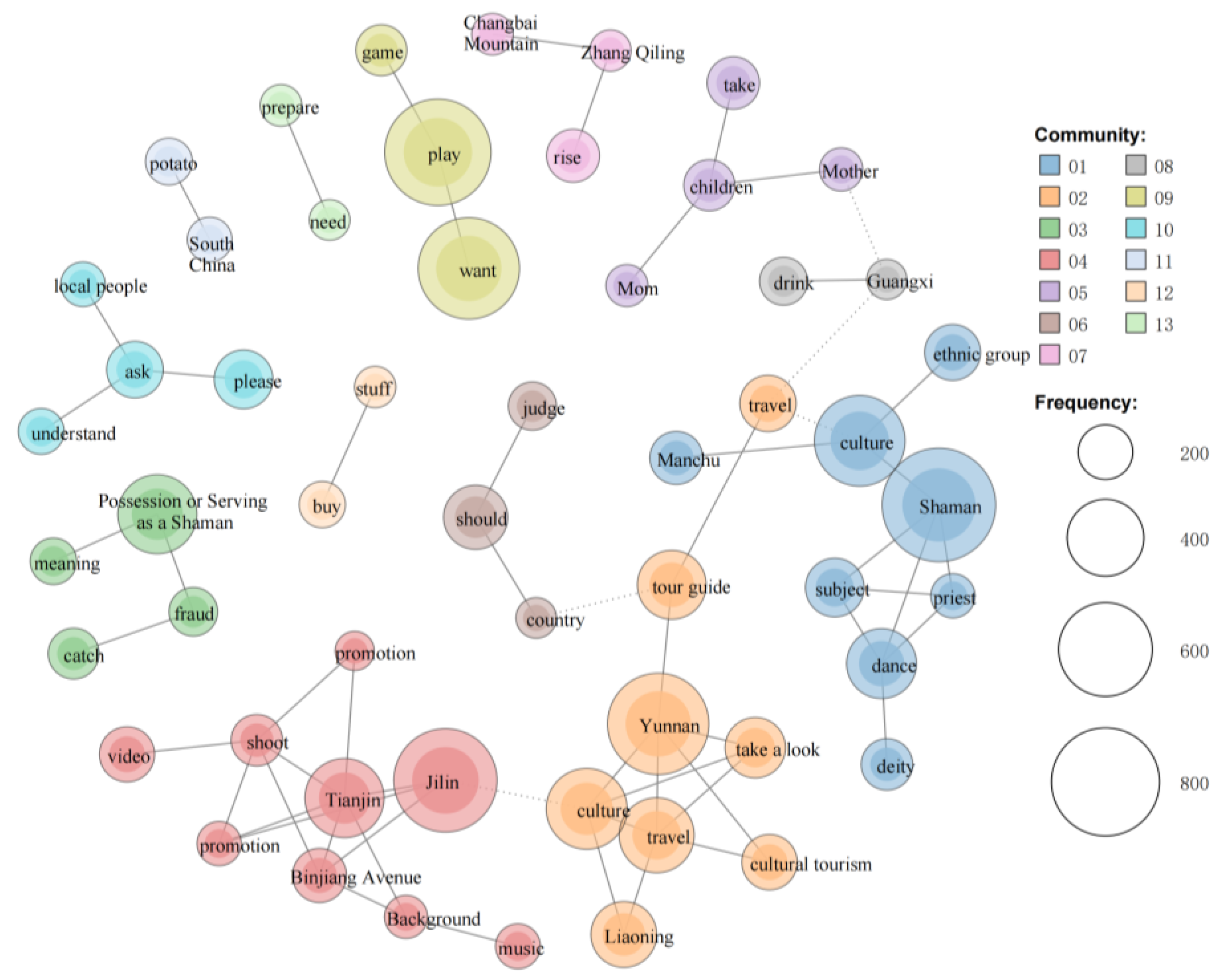

Predication strategy refers to the use of positive or negative evaluative language, implicit or explicit predicates, to construct positive or negative images of participants. After removing adverbs and other function words, and retaining adjectives and verbs, a random walk network diagram generated by KH Coder shows that the node “subject” occupies an important position in the network and is closely associated with “Shaman” (

Figure 4). This suggests that the corpus related to “subject” has a certain centrality and high-frequency interaction in the text network, possibly forming a specific semantic link with “Shaman”. In contrast, although nodes such as “culture” and “priest” also carry significant weight in the semantic network, their meanings are more conventional and widely distributed across different contexts, making it difficult to reveal unique thematic features. The prominence of the “subject” node may reflect a more specific textual theme, potentially involving unique narrative logic, symbolic systems, or social practices, thus providing an opportunity to explore the deeper structure within the corpus. Therefore, by combining community detection in the network, this section focuses on the analysis of comments related to the “subject” node, examining its co-occurrence pattern with “Shaman” and its con-textual meanings to uncover how users discuss human will in Shamanic performance.

The search term for the “subject” node yielded 232 hits. From the concordance lines, it is clear that the “subject” node refers to “Subject 3”, a popular dance phenomenon in Chinese social media, originating from a wedding dance in Guangxi, in-volving ankle inversion, waist twisting, hip swaying, and hand waving, characterized by strong entertainment value. However, the combination of this viral dance with Shamanic culture has sparked significant controversy. Semantic tones can generally be divided into positive, neutral, and negative categories (

Stubbs 1996). A detailed examination of the concordance lines, considering the context, reveals that positive constructions of “Subject 3” appear 10 times (4.3%), neutral tones occur 64 times (27.6%), and negative constructions of “Subject 3” appear 158 times (68.1%) (

Table 2). Although the majority of evaluations are negative—suggesting that many netizens view the conflation of a commercial dance with sacred Shamanic practices as offensive to faith or as vulgar entertainment—the small portion of positive remarks reveals an alternative perspective. Some positive comments highlight the aesthetic and cultural value of the Shamanic performance, praising the creativity and skill involved. These appreciative evaluations suggest that, when executed with respect for tradition, the incorporation of Shamanic elements into popular performance can serve as an adaptive expression of ancient ritualistic practices, revealing alternative perspectives that acknowledge creativity.

The dominant tone in digital discourse is critical. Negative comments frequently condemn the performers who blend shamanic rituals with commercial dance, viewing them as disrespectful to sacred traditions. For instance, one user rebukes: “Don’t try to imitate the priests of Jilin and make a fool of yourself with ‘Subject 3’”. In such criticism, the performers are seen as violating the sacred relational order that defines human will, which in shamanic traditions is not autonomous expression but a cosmological negotiation between ancestral spirits, ecological forces, and communal obligations. Similar straightforward reproaches appear in other comments: “I really hate ‘Subject 3’”, “Forcing them to perform ‘Subject 3’ is both tacky and absurd”, “Watching them perform ‘Subject 3’ feels very uncomfortable”, and “Shamans performing ‘Subject 3’ is ironic”. These comments frame the performers as disrupting the delicate balance of human will that, in the shamanic cosmology, maintains harmony between human, spiritual, and ecological realms through ritual. Terms like “tacky”, “absurd”, “ridiculous”, and “ironic” condemn the behavior as vulgar, disrespectful, or absurd. Crucially, these adjectives do not merely describe objective characteristics; they are judgments about the performers. When netizens say it is “ironic” for shamans themselves to dance this way, or that using “Subject 3” is “crossing a line”, the underlying assertion is that the performers betray their sacred responsibility to align with ancestral and community cosmology. This discourse thus frames the performers for entertainment or modernization as injurious to the sacred relational order.

In these negative evaluations, commenters implicitly draw boundaries between the will to modernize and the will to protect the cosmological integrity of shamanic practices. The critical tone reflects the human will as fundamentally intersubjective, where judgments of individual actions depend on their alignment with the community’s shared collective spiritual and ecological responsibilities. The language used—“make a fool of yourself”, “hate,” “uncomfortable”, “tacky and absurd”—conveys moral disidentification with what the commenters perceive as trivialization of sacredness. These judgments emphasize the deeply cosmological nature of human will, where actions are not isolated but embedded in networks of sacred obligations and relationships. In effect, these discourses assert that certain expressions of will—such as the will to profit through spectacle or attract attention—are inferior to others, like the will to maintain reverence and preserve sacred relational order. Users frequently invoke the collective will of threatened communities or ancestors—the will to protect the sacred integrity of human will.

In contrast to the mainstream of negative evaluations, a minority of comments praise aspects of fusion performances. These positive evaluations emphasize the cosmologically aligned dimensions of will. For example, one netizen unexpectedly observes: “Shamans performing ‘Subject 3’ actually looks quite good”. Here, the commenter acknowledges innovative forms of cosmological will when the performer’s will remains aligned with sacred relational order. The word “actually” emphasizes surprise at the authenticity or success of the attempt; it suggests a potential skepticism that has been overturned. Positive framing indicates recognition of will that adapts while maintaining cosmological alignment. In these cases, the performers are interpreted not as departing from tradition but as a deliberate effort to extend its cosmological principles into new forms, fostering respectful dialogue between tradition and modernity. These commenters read such actions as conscious, tradition-respecting expressions of will rather than manifestations of commercial impulses. Attributing skill and aesthetic value to the performances portrays the performers’ will as constructive—a will to revive or respect tradition in new forms.

However, even positive evaluations sometimes express appreciation in conditional terms. Analysis notes that when positive comments appear, they often qualify that fusion “can be acceptable when it respects tradition”. This conditional praise reflects the shamanic understanding of will as spiritually accountable, requiring that any modernization remains embedded in sacred relational order. Thus, the will that receives praise is one that carefully balances innovation with respect. These appreciative evaluations suggest that purposeful, respectful modernization can serve as an adaptive expression of shamanic ritual will, reaffirming traditional meaning in a changing world. The positive discourse thus aligns with the shamanic cosmological understanding of will, where innovation and respect coexist within a sacred relational framework.

Approximately one-quarter of comments are neutral. These comments neither explicitly condemn nor praise the practice, often simply recording the event or expressing mild surprise. For instance, one user simply reports: “I woke up to find even the high priests performing ‘Subject 3’”. This statement, while neutral, acknowledges the performers as part of the ongoing negotiation of human will in modern contexts, reflecting an openness to observing how sacred relational obligations are reinterpreted in contemporary settings. The statement is primarily factual and reflective, rather than evaluative. It highlights that the will of tradition holders may lead them to engage with this popular dance. The neutrality here may indicate an open curiosity—an implicit understanding or simply an observational stance toward expressions of will. In other contexts, neutral tones often accompany descriptions or questions, as when commenters discuss the phenomenon without judgment or treat it as a matter of fact. These neutral discourses subtly acknowledge the relational and cosmological dimensions of human will, leaving space for interpretation and negotiation in digital discourse.

The differences between negative, positive, and neutral discourses highlight the contested nature of human will in shamanic performances. Negative evaluations harshly judge the will to modernize or entertain, implying that such will betrays the will of the community or ancestors. In contrast, positive evaluations encourage will that adapts within cosmological boundaries, viewing creative expressions of will as a form of respect. Neutral stances occupy middle ground, affirming the existence of these expressions of will without labeling them. This tripartite structure reflects the relational, cosmological, and intersubjective dimensions of human will, challenging dominant paradigms of individual autonomy. This tripartite structure of evaluation—predominantly critical but punctuated with moments of praise and fairness—reflects broader tensions in digital discourse about shamanic authenticity and modern identity. Evaluative language frames debates about modernization and identity: Is the human will to change seen as an intrusion on tradition or a valid reinterpretation? The analysis above illuminates these judgments, showing how digital participants actively interpret and critique human will while negotiating cultural change. In conclusion, discourse analysis reveals user discourse strictly regulating the will behind performances. These descriptions capture dialogical judgments about how human will should relate to heritage. These discourses highlight the contested nature of relational and cosmological will in digital discourses about Shamanism, emphasizing the need to address these debates through the ontological framework of shamanic traditions.

6.2.3. Argumentation Strategy

The argumentation strategy in DHA (Discourse-Historical Approach) involves the use of relevant argumentative topos (such as usefulness/advantage, uselessness/disadvantage, danger, threat, numbers, law, responsibility, history, culture, and abuse, etc.) to substantiate positive or negative descriptions (

Reisigl and Wodak 2014). Through careful examination of the “Shaman” concordance lines, it be-comes evident that the historical and cultural topics are primarily employed, underscoring the continuity of Northeast China’s Shamanic heritage. Shamanic culture is a worldwide religious culture that has deep roots in China and has never been interrupted and is still active among northern ethnic minorities (

Liu 2023). Such continuity is emphasized in digital discourse through explicit references to long histories, situating contemporary practices as the inheritors of a venerable lineage. By foregrounding history and culture, these topoi frame human will as legitimate when it aligns with ancestral tradition: human will is portrayed not as purely personal or novel, but as embedded in a collective narrative that spans generations.

Expressions like “the oldest origin” or “millennia-old tradition” are common in tourism and social media descriptions. These formulations serve to establish historical legitimacy; by stressing antiquity, they imply that modern practitioners’ conscious decisions and intentional actions reflect a human will that is valid because it stems from an ancient source. Invoking the “religious culture of the Tungusic people”, for example, anchors Shamanism in a specific ethnic heritage and community identity. This cultural topos highlights shared customs and values. It presents Shamanic rituals as embodiments of communal memory and collective identity. In this way, protecting these traditions is portrayed as essential for preserving cultural continuity and social cohesion. Safeguarding Shamanic heritage thus ensures that the knowledge and values inherited from ancestors continue to guide both communal life and individual purpose. Digital narratives and tourism discourse repeatedly integrate these historical and cultural appeals. On online platforms, Shamanism is framed as a cultural treasure that embodies the region’s heritage. Comments and descriptions often link personal experiences or local initiatives to this shared past, suggesting that individual actions gain meaning only in relation to the collective heritage. By positioning Shamanism as a source of ethnic pride and cultural richness, these digital representations underscore the urgency of preserving traditions amid modernization.

The argumentation strategy constructs a model of human will that is both adaptive and resilient. Will is not depicted as radical individualism but as conscious decision-making that has been “accrued” through history. In the heritage discourse of digital tourism, collective and personal will are intertwined: individual conscious choices are seen as extensions of communal intentions, and communal values are enacted through personal practice. It implicitly defines legitimate will as that which reinforces the continuity of Shamanic culture through deliberate decisions. By doing so, historical and cultural topoi serve to preserve Shamanic identity in the digital age and to contest any portrayal that would detach human will from its heritage roots.

7. Conclusions

This study has examined how human will is articulated, negotiated, and reimagined within digital discourses about Shamanism on Chinese TikTok (Douyin), focusing specifically on representations of Northeastern Shamanic culture. Drawing on a corpus of 293,284 tokens collected from user comments between January 2020 and December 2024, and employing a triangulated methodology that integrates LDA topic modeling, the Discourse-Historical Approach (DHA), and virtual ethnography, this research has provided a multi-dimensional understanding of how human will persists, adapts, and transforms in contemporary digital environments.

The research reveals that in the digital discourse of Northeast Shamanism, human will is manifested in complex ways, deeply reflecting the relational, cosmological, and ritualistic notions of will unique to Shamanic culture. On the one hand, users actively express their will by intentionally preserving cultural and spiritual heritage, affirming community identity and a sense of belonging, and highlighting the profound connections between this will and history, faith, and cultural traditions through the multiple discursive constructions of the “Shaman” identity. On the other hand, the discourse clearly reflects the processes of commercialization, popularization, and playful reappropriation, revealing how sacred traditions are reshaped under the pressures of digital entertainment and tourism-driven narratives. Within these dynamics, people engage in intense debates over which expressions of will align with or deviate from the core values and cosmology of Shamanic traditions. In this context, the expression of human will is far from passive consumption; it often involves active emotional investment and critical negotiation to uphold or challenge the legitimacy and cultural continuity of specific expressions of will, as well as to creatively reinterpret the contemporary significance of Shamanic heritage. By treating TikTok comments as legitimate ethnographic material and contextualizing discursive patterns through historical and social perspectives, this study extends existing work in digital ethnography and critical discourse analysis. It demonstrates that digital platforms like TikTok are not merely spaces for cultural consumption but also stages for indigenous agency—an agency rooted in specific cultural notions, continuously negotiated through multiple discursive practices, and strategically adapted to modern contexts—to be dynamically and multifacetedly asserted, contested, and reshaped.

This study underscores that Shamanic constructions of human will provide a meaningful counterpoint to dominant secular and rationalist frameworks. Rather than emphasizing autonomy in isolation, these traditions conceptualize the will as emergent from ancestral duty, cosmological orientation, and collective memory. Such a model of agency resists the reductive dichotomies of modern thought—reason versus faith, autonomy versus tradition, individual versus community—and instead posits an integrative understanding of the human will as both intentional and interdependent. In doing so, discourses about Shamanism reveal not only how agency is exercised within indigenous cosmologies, but also how it can be reimagined in the face of modernization, commodification, and digital transformation. These insights invite a rethinking of agency in global philosophical discourse, foregrounding indigenous epistemologies as vital to the ethical and spiritual questions of the present.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the exclusive reliance on online data, without conducting field-based ethnographic investigations, limits the study’s ability to capture embodied ritual practices, lived religious experiences, and the material dimensions of shamanic culture in Northeastern China. Second, the focus on textual user comments means that multimodal aspects of digital discourses about Shamanism—such as video performances, visual symbolism, and soundscapes—have not been systematically analyzed. Future research could address these gaps by integrating traditional fieldwork with virtual ethnography and adopting multimodal discourse analysis frameworks to better understand how human will materializes across diverse semiotic modes both online and offline. In conclusion, this research highlights that human will remains a vital, resilient, and adaptive force in the digital negotiation of Northeastern Shamanic culture, illustrating how indigenous traditions continue to find new life, meanings, and tensions within the rapidly changing landscapes of digital communication.