1. Introduction

Mehmet Barut was a cleric—a Muslim legal expert empowered to give rulings on religious matters—who served as a mufti in the Republic of Türkiye. He began to work as a mufti in the Turhal district of the city of Tokat in 1964 and was appointed as the mufti of Kaman in Kirşehir in 1970, Sivaslı in Uşak in 1981, and Anamur in Mersin in 1985. Barut, who also served as a mufti in various cities in Anatolia throughout his life, retired in 1987. He wrote articles in local newspapers and magazines in the districts where he served. His only published work during his lifetime was

Hikmetin Mantığa Seslenişi [Wisdom’s Address to Logic]. Additionally, he had other works awaiting to be published as books:

Gerçek Hayat [Real Life],

Ihya al-Kulub Çevirisi [Translation of Ihya al-Qulub],

Şifâ Şerhi [Commentary on Şifâ], Aliyyü’l-Kârî Çevirisi [Translation of Aliyyü’l-Kârî], and

Ölüm İçin Hediyeler [Gifts for Death] (

Barut 2022, pp. 2–9).

While serving as a mufti in Turhal, Barut went on the hajj pilgrimage in 1967 as a religious guide. His hajj memoirs were published, which lasted a total of thirty-eight days, in 177 serials under the title “Hicaz Yolları [Hejaz Roads]” in the newspaper

Demokrat Turhal in 1967 (

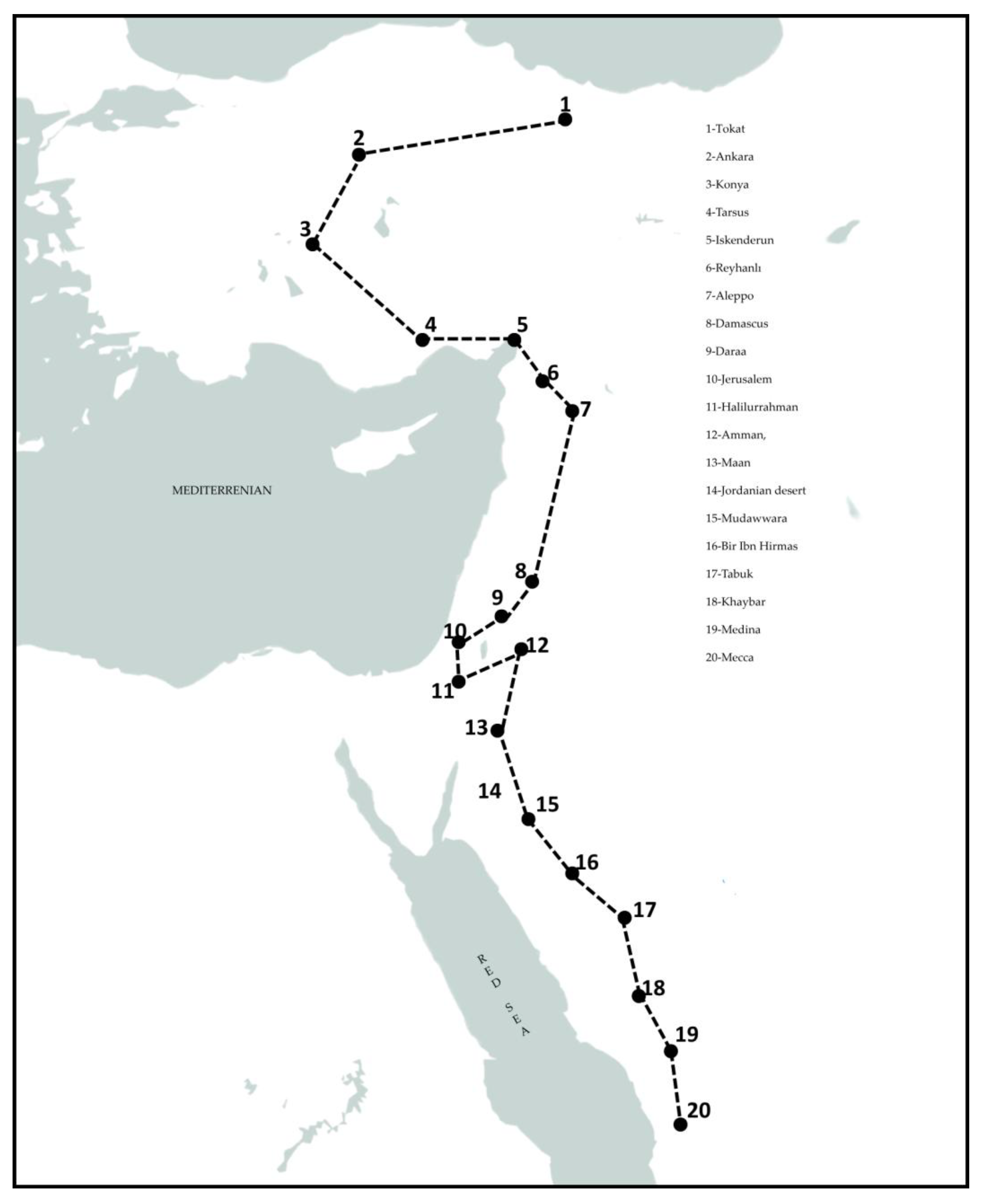

Barut 2022, p. 7). The series of newspaper articles were later published as a book by Kamil Büyüker after Barut’s death. Barut went to Mecca by bus from the Anatolian city of Tokat to perform the hajj. Barut set out from Tokat and followed the route of Ankara, Konya, Tarsus, Iskenderun, and Reyhanlı within the borders of Türkiye. After passing through the Syrian borders, he moved on through Aleppo, Damascus, Jerusalem, Amman, and Maan, stopped by the cities of Tabuk and Khaybar, and reached the cities of Medina and Mecca.

The most significant part of Mehmet Barut’s hajj pilgrimage was that he decided to set off a long and arduous road trip in a period when air travel was largely used. When we look at the history of hajj pilgrimages and travel journal texts in the Republic of Türkiye, it is apparently revealed that Barut’s pilgrim’s journey was different and special. From the year 1923, Türkiye officially became a republic, and until 1947, hajj pilgrimages were not allowed due to the political conditions, economic reasons, and epidemic diseases such as cholera (

Güran 1996, p. 408;

Kırmıt 2025, p. 129). The years in question correspond to the single-party rule of the Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, CHP) in Türkiye. Following the transition to a multi-party democratic system in 1946, the CHP was subjected to substantial criticism, particularly for its perceived conflation of secularism with irreligion and for its policies that were seen as constraining the public’s freedom of religious expression. The Democratic Party (Demokrat Parti, DP) victory in the Turkish general elections on 14 May 1950, marked the beginning of a period characterised by significantly expanded freedoms in matters of religious belief and practice (

Güran 1996, p. 408). However, the DP was overthrown by the military coup carried out on 27 May 1960, and was subsequently dissolved on 29 September 1960. The Justice Party (Adalet Partisi, AP), established in 1961 under the leadership of Süleyman Demirel, continued the political mission of the DP. The AP, regarded as the successor to the DP—which had been dissolved as a result of the military coup—remained in power as the sole ruling party in Türkiye between 1965 and 1971 (

Bora 2017). Accordingly, in 1967—the year Mehmet Barut performed the hajj—there was a climate of freedom concerning religious beliefs and practices. Beginning in the 1950s, Mehmet Barut utilised the newspapers and magazines of the period as instruments of religious guidance. In doing so, he preferred publications issued by figures affiliated with the Democratic Party, particularly those bearing the title ‘Democrat’. This preference stemmed from the fact that these newspapers, which were aligned with the ideological stance of the DP, also gave voice to the spiritual sentiments of the public (

Barut 2022, p. 6).

In Türkiye, after 1947, with the advancements in transportation, air travel became the preferred method for pilgrims journeying to Mecca for hajj. Among the authors of published books—Mehmet Hulusi Efendi (

Kara 2020); Mustafa Necati Ak (

Özalp 2011);

Necip Fazıl Kısakürek (

1973);

Mustafa Yazgan (

1978);

Ahmet Sırrı Arvas (

2004);

Serap Şirin (

2006);

Emel Esin (

1960)—only one author travelled by sea while the others chose air travel for their hajj pilgrimages. In the modern age, air travel is not only the preference for the hajj pilgrimages in Türkiye; studies show that air travel has become prominent in hajj journeys to Mecca from all countries of the world, and the number of pilgrims abroad has reached millions with the use of air travel (

Bianchi 2016, pp. 131–51;

Wolfe and Aslan 2015). According to the data of the Saudi Arabian Statistical Council, 79% of the pilgrims who went to Mecca in 1994 preferred air travel, 12% preferred land travel, and 9% preferred sea travel (

Benjamin Claude 2016, p. 88). This statistic continues to increase with an increase in the preference for air travel from year to year. In 2019, 94% of the pilgrims who went to Mecca preferred air travel. Although air travel is more expensive, it is preferred because it shortens the travel time and provides comfort, especially given the difficulties with alternative means of transportation (

Yumuşak and Bilgin 2021, pp. 6–7).

Nimrud Luz (

2020, pp. 1–2) defines all journeys undertaken by Muslims for spiritual purposes, including hajj journeys, as religious tourism. When land routes were predominantly used by hajj pilgrims, religious tourism became an integral part of the journey, as the pilgrimage could take months and required extended stays along the route for rest and accommodation. Pilgrims not only met their daily needs at these service areas, but also visited historical cities, religious sites, and tombs of Islamic figures. However, the convenience of air travel has significantly reduced the time and opportunity for extended worship and visitation. As a result, the spiritual engagement that once began with the journey itself is now largely confined to the sacred rituals performed within the pilgrimage areas. Another drawback of the shortened pilgrimage journey is its negative impact on the economies of countries and cities that once benefited from the flow of pilgrims before air travel became widespread. About a century ago,

Cenap Şahabettin (

2022, p. 247), one of the pioneers of Western symbolic poetry in Turkish literature, wrote a travel book called

Hac Yolları [On the Way to Hajj], in which he mentioned the railway built between Jeddah and Mecca. According to him, the railway had a negative impact on the people’s income and caused economic hardship because, in Hijaz, the people’s primary source of income came from pilgrims. The more money the pilgrims spent, the more the quality of life of Hijaz people increased. This applied not only to the road between Jeddah and Mecca, but also for the entire Istanbul–Damascus–Mecca route.

In modern times, as the hajj pilgrimage has become more accessible with faster modes of transportation, travel narratives have almost come to an end and reflect shorter experiences. Mehmet Barut’s pilgrimage is reminiscent of the pilgrimages made by land during the Ottoman Empire. In the Ottoman Empire period, there were two important pilgrimage caravans that followed the Damascus and Cairo routes to reach Medina and Mecca every year, called the Haremeyn-i Serifeyn

1 (

Faroqhi 2024, p. 58). According to studies on hajj pilgrimages during the Ottoman period, the Damascus pilgrimage caravan set out from Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, following the Anatolian right-hand route, passing through the holy lands of Eskişehir, Konya, Adana, and Antakya and finally reaching Damascus (

Faroqhi 2024, p. 69;

Armağan 2000, p. 76;

Eroğlu Memiş 2020, pp. 287–93;

Şahin 2021, pp. 193–98;

Kaplan 2020, p. 151). The Istanbul–Damascus–Mecca route was also the route used by trade caravans travelling to Hijaz for centuries. There is no doubt that Mehmet Barut’s land route to Mecca was not exactly the same as those used during the Ottoman period because, in the past, people used animals for transportation, while Barut’s journey was made by bus. Moreover, motor vehicles allowed for fewer stops compared to mounted animals due to their speed and efficiency. However, Barut’s hajj pilgrimage route and the Ottoman’s hajj caravan routes have something in common at certain points. The cities of Konya, Antakya, Damascus, Maan, and Tabuk are locations where Barut’s hajj pilgrimage route crossed with that of the Ottoman’s. At those destinations, there are historical buildings, places of worship such as historical mosques, and the graveyards of Muslim scholars where Barut visited in the same way the Ottoman’s pilgrims visited in the past.

Studies show that when we look at the Turkish literature, hajj travel journals are apparently limited during the Ottoman Empire. In fact, studies reveal that hajj travel journals were written from the 13th century to the middle of the 20th century (

Coşkun 2002;

Kolbaş 2021, pp. 13–26;

Kiraz and Tiryaki 2023, pp. 112–18;

Çavuşoğlu 2019, pp. 63–76;

Kaplan 2020, pp. 154–56). In Ottoman literature, among the known works related to hajj pilgrimage are those in the genres of menazil-i hajj and menasik-i hajj that stand out today. Menazil-i hajj texts provide a guide for the cities and sites along the pilgrimage routes, outlining the various stops and settlements. Menasik-i hajj texts are texts that explain the procedures and principles of pilgrimage. His travelogue, inspired by these classical Ottoman texts, warrants comparison with post-1940 hajj narratives and should be analysed as a literary genre. This is particularly important given that contemporary authors tend to publish their hajj accounts under headings such as journey, travelogue, memoir, diary, or even blog rather than using traditional terms like menazil-i hajj or menasik-i hajj.

This study analyses Mehmet Barut’s Hicaz Yolları [Hijaz Roads], a hajj travelogue written during the Republican period, in terms of both route and literary genre. It seeks to provide a comprehensive perspective on hajj travelogues in Turkish literature, tracing their evolution from the Ottoman era to the present day. A close reading method will be employed to examine Barut’s work, including the route taken, accommodation, and locations visited. In addition, a comparative analysis method will be used to assess Hicaz Yolları alongside Ottoman- and Republican-era hajj narratives, both in terms of geographical route and literary form. This study is structured into four main sections following the introduction. The second section outlines the pilgrimage routes utilised during the Ottoman Empire. The third section discusses Mehmet Barut’s life, his hajj pilgrimage, and key places he visited. The fourth section compares Barut’s chosen route with those of Ottoman-era pilgrims, aiming to highlight both continuities and departures, and to explore how Barut’s journey bridges historical tradition and modern experience. The fifth section focuses on the literary analysis of Hicaz Yolları, evaluating its significance within the corpus of hajj literature. The goal of this analysis is to trace the transformation of hajj narratives over time and to demonstrate how Barut’s work reflects both a continuation and reinterpretation of earlier literary conventions.

2. The Hajj Pilgrimage Route by Road in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire ruled over a vast area for six centuries. During this period, it established a regularly operating road system, which helped facilitate either their commercial, economic, and military activities or transportation and communication services. This operating system consisted of main roads starting from the capital city of the empire, Constantinople (subsequently Istanbul), reaching Anatolia and Rumelia, and secondary roads connected to these main roads. The main roads in the Ottoman Empire had three main routes: right-hand, middle, and left-hand routes (

Faroqhi 2024, pp. 68–69). The right-hand route connecting Istanbul to Anatolia started from Uskudar and reached Aleppo via Eskişehir, Akşehir, Konya, Adana, and Antakya. Moreover, a road branching off from Antakya went all the way to Damascus, and from Damascus led to Mecca. In the Ottoman Empire, the

Sürre Regiment

2 and the hajj pilgrims were sent from Istanbul to Mecca regularly every year with the encouragement and support of Sultans, using the Istanbul–Damascus–Mecca route (

Armağan 2000, pp. 73–75).

The first

Sürre Regiment was sent by Sultan Yıldırım Beyazıt in the Ottoman Empire, and the hajj pilgrimage journeys began during his sultanate. The deployment of the

Sürre Regiment continued during the sultanates of the Ottoman sultans Çelebi Sultan Mehmet, Murad II, Fatih Sultan Mehmet, and Beyazid II. Yavuz Sultan Selim conquered Syria and Palestine in the Battle of Marj Dabiq in 1516, and Egypt in the Battle of Ridaniya in 1517; thus, the Memluk State surrendered. Finally, the regions around Mecca and Medina came under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, and the Ottoman sultans received the title of Hadimu’l-Harameyn

3 (

Petersen 2008, p. 20;

Armağan 2000, p. 76;

Kahraman 2017, p. 43). Holding this title required certain responsibilities, one of which being to ensure the security of the hajj pilgrimage routes (

Benjamin Claude 2016, p. 102). The military units in the Ottoman Empire were charged with the security of the hajj pilgrimage route, accompanying the pilgrims who used the Syrian and Egyptian routes. Land travel was difficult for hajj pilgrims who used horses, mules, and donkeys on the way to Damascus as modes of transport. However, there were also other pilgrims who went to Mecca on foot. From Damascus, the hajj pilgrims continued their journey on camels due to the geographical conditions (

Şahin 2021, pp. 195–96).

When we examine the history of the Ottoman Empire, the hajj pilgrimage journeys were arranged and proceeded by sea and railway after land travel lost its popularity. In the nineteenth century, the widespread adoption of steamships, coupled with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869—which linked the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea—significantly enhanced maritime transportation. Pilgrims travelling by sea typically first arrived in Beirut, then proceeded to Jeddah via the Suez Canal, before continuing to Mecca to fulfil their pilgrimage obligations (

Şahin 2021;

Benjamin Claude 2016). Following the completion of the Hijaz Railway line in 1908, the railroad was utilised for facilitating pilgrimage travel. Departing from Istanbul’s Haydarpaşa Station, the train’s initial stop is Konya. The railway extends from Konya to Aleppo, then from Aleppo to Damascus, and subsequently from Damascus to Mecca. However, these expeditions were interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, as the weakening of the Ottoman Empire and the threats to the pilgrimage route rendered such journeys increasingly perilous. Consequently, the last

Sürre Regiment managed to reach Mecca in 1915 (

Kahraman 2017, p. 45). Between 1916 and 1923, no state-sponsored pilgrimage organisations were established, with pilgrimage activities occurring solely through individual initiatives (

Kırmıt 2025, p. 129).

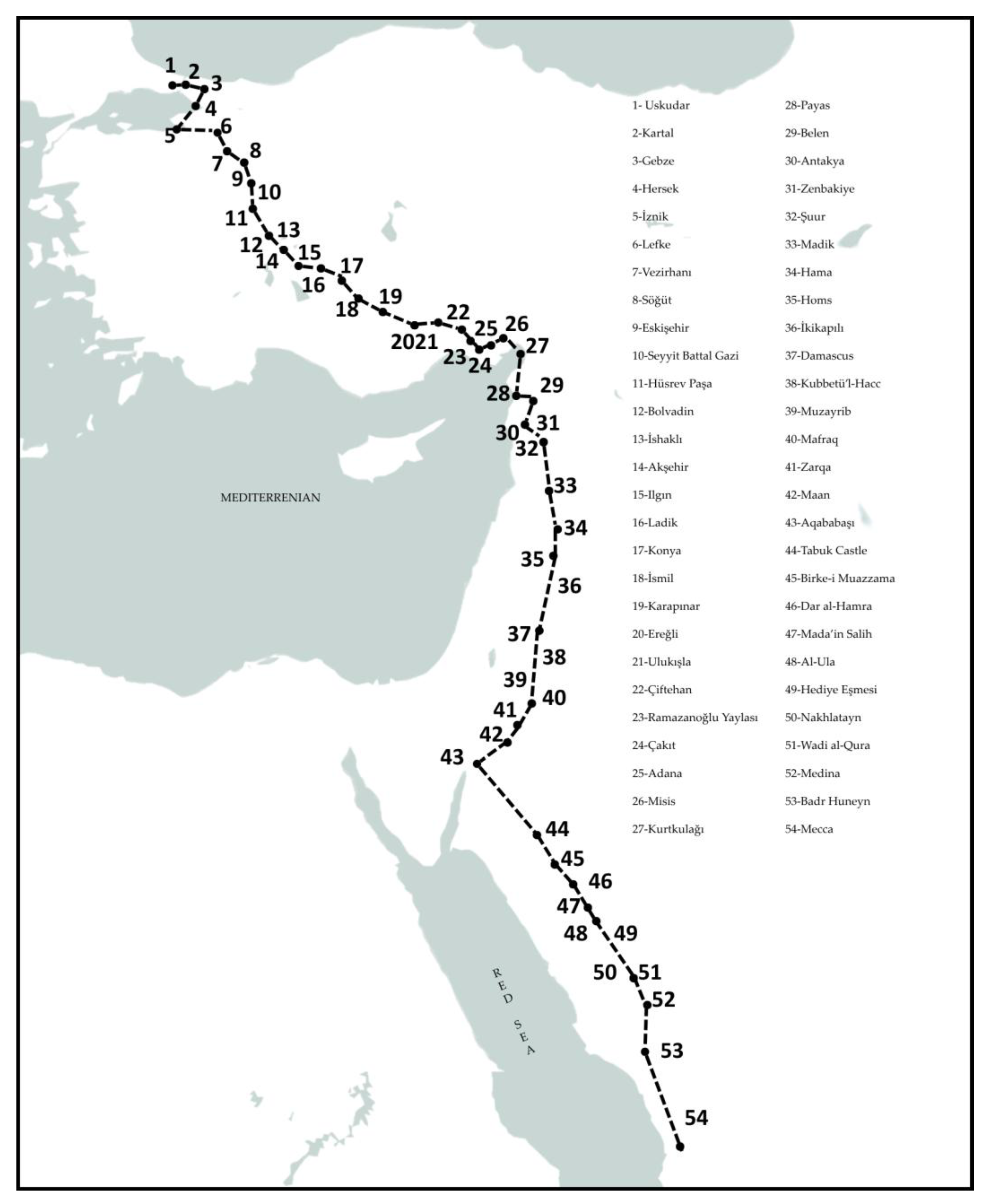

The hajj pilgrimage that we will examine within the study involves the highways following the Istanbul–Damascus–Mecca route seen on the map in

Figure 1. The accommodations on this highway have still preserved their existence with exceptions due to road, weather, and security reasons. According to Latif Armagan’s determination (

Armağan 2000, pp. 82–98), the hajj pilgrimage caravan that sets out from Uskudar passes through Kartal, Gebze, Hersek, İznik, Lefke, Vezirhanı, Söğüt, Eskişehir, Seyyit Battal Gazi, Hüsrev Paşa, Bolvadin, İshaklı, Akşehir, Ilgın, Ladik, Konya, İsmil, Karapınar, Ereğli, Ulukışla, Çiftehan, Ramazanoğlu Yaylası, Çakıt, Adana, Misis, Kurtkulağı, Payas, Belen, Antakya, Zenbakiye, Şuur, Madik, Hama, Homs, İkikapılı, and reaches Damascus. From Damascus, it leads through Kubbetü’l-Hacc, Muzayrib, Mafraq, Zarqa, Maan, Aqababaşı, Tabuk Castle, Birke-i Muazzama, Dar al-Hamra, Mada’in Salih, Al-Ula, Hediye Eşmesi, Nakhlatayn, Wadi al-Qura, Medina and Badr Huneyn and then reaches Mecca. The number of stops between Üsküdar and Damascus is thirty-five, and the number of stops between Damascus and Mecca is sixteen.

The pilgrimage route described by Latif Armağan closely corresponds to the routes documented in both verse and prose pilgrimage travelogues composed during the Ottoman period. For example, pilgrimage accounts from the Ottoman period, including

Tuhfetü’l-Hüccâc [The Gift for the Pilgrims] by the 17th-century Ottoman official Hacı Ali Efendi,

Menâzilü’t-Tarîk ilâ Beytullâhi’l-Atîk [Stops Along the Route to the Kaaba] authored by Abdülkadir Çelebi (known by the pseudonym Kadrî), and the

Manzum Hac Seyahatnamesi [A Poetic Travelogue of the Hajj] by the poet using the pseudonym Servet, consistently document the Istanbul–Sham–Mecca route. During the 18th century, the historical pilgrimage route was documented in works such as

Menzilname [Itinerary Book] by the poet known as Bahrî and

Menâzilü’l-Harameyn [Stages to the Two Sacred Precincts] by Seyyid İbrahim Hanif, while in the 19th century, it was similarly reflected in Mehmet Edip’s

Behcetü’l-Menazil [The Beauty of the Stops] (

Kiraz and Tiryaki 2023, pp. 112–18).

During the Ottoman period, the stopovers, service areas, and facilities on the land route for the hajj pilgrimage remained the same from Istanbul to Damascus. However, from Damascus onwards, the service areas and stops changed due to geographical conditions and security concerns. Nevertheless, these places were preferred because they were safe and provided accommodation and shopping opportunities (

Şahin 2021, p. 196). In fact, the Ottoman Empire established various types of infrastructure in Istanbul to meet the needs of the hajj pilgrims, including mosques, masjids, caravanserais, baths, soup kitchens, and bridges; moreover, wells and water pools called

birke were built to support the hajj travellers (

Shafir 2020, p. 15;

Armağan 2000, p. 99).

3. Mehmet Barut’s Hajj Pilgrimage

Mehmet Barut undertook his hajj pilgrimage journey by bus, travelling as part of a group rather than individually. Despite the group context, this study will centre specifically on Barut’s personal experiences and reflections. He departed from the Turhal district of Tokat on 24 February 1967, and returned on 2 April 1967, completing a thirty-eight-day journey (

Figure 2). Barut began composing his memoirs shortly after his return, on 27 April 1967, and completed them on 28 November 1967.

Barut set out from Tokat and reached Ankara via Amasya-Çorum-Elmadağ. Here, he visited the tomb of Hacı Bayram Veli, founder of the Bayramiye order and a mystic-poet, located in the Hacı Bayram Mosque in Ankara. Barut’s next stop after Ankara was Konya. Here, he first visited the tomb of Mevlana Celaleddin-i Rumi, the founder of the Mevlevi order and a renowned mystic-poet, and then went to see other spiritual sites of the city (

Barut 2022, pp. 16–17).

The next stopover after Konya was Tarsus, a city in the southern part of Türkiye. The graves of Prophet Danial, Lokman Hekim, Caliph Me’mun, and Bilal-i Habeshi are places he visited at the earliest opportunity. The first place Barut visited in Tarsus was the Cave of the Seven Sleepers mentioned in the Qur’an, also known as Ashab al-Kahf. It is believed that seven people hid in the cave and fell asleep, waking up many years later.

Barut (

2022, pp. 17–23) shared insights on the location of Ashab al-Kahf in Tarsus and the cave’s significance in different parts of the world, as the story is mentioned in the Qur’an as well as in Christian narratives. Barut shared extensive and comprehensive insights on the Cave of the Seven Sleepers, presenting not only his personal observations but also encyclopaedic knowledge on the subject. In his memoirs, he offered clear and well-informed explanations, aiming to convey accurate and accessible information to his readers.

Barut’s group, which departed from Tarsus, passed through the borders of Adana and Osmaniye and finally reached Iskenderun, which is located in the border of Hatay

4 province. He chose this city for its accommodation facilities. Barut, who spent the night of 27 February in Iskenderun, stayed in the Kırıkhan district of Hatay the following day. Here, he visited the tomb of Bayezid-i Bistami, considered one of the leading figures of Islamic thought and Sufism. During his visit, he wrote about the location and appearance of the tomb of Bayezid-i Bistami and relayed anecdotes about him (

Barut 2022, pp. 24–27). Thus, during his visit, Barut either introduced the sacred site of this city to the reader or shared his reflections on the prominent Islamic figure, Bayezid-i Bistami.

Barut’s next stop was the Reyhanlı district of Hatay. It was a tradition among the people of Reyhanlı to host pilgrims passing through their district. On the day that the pilgrims stopped by Reyhanlı, all houses were full of pilgrims. They were warmly welcomed and given food and shelter by their hosts (

Barut 2022, pp. 27–28).

The next stop after Reyhanlı was the Cilvegözü Border Gate, between Türkiye and Syria. Water scarcity occurred here; people waited restlessly for long periods of time for water and in queues for toilets. The mosque at the border gate did not have enough space to accommodate the worshippers (

Barut 2022, pp. 29–30). After completing the mandatory stop at the border gate, Barut’s first stop in Syria was Aleppo. This city left a hugely significant impact on him with its beautiful roads, lighting, road verges, and apartment buildings resembling mountain ranges. Barut stayed across from a mosque in Aleppo where the tomb of the prophet Zechariah (Hebrew Prophet) was located. During his stay, he continued writing and shared his reflections about the location and surrounding environment of the mosque, hotels, markets, and houses of Aleppo (

Barut 2022, pp. 33–35).

Barut’s next stop after Aleppo was Damascus. The first place he visited in this city was the Ahl al-Bayt cemetery. Barut listed the important names of Islamic figures buried in this cemetery one by one and wrote his reflections on them. He also visited other places, including the graves of Bilal-i Habeshi, Pamuk Baba, Muhyiddin Ibn-i Arabi, and three Turkish soldiers (

Barut 2022, p. 37).

Another stop on Barut’s journey through Syria was the town of Daraa. Similar to the experience at the Cilvegözü Border Gate between Türkiye and Syria, Daraa posed significant challenges due to prolonged waiting times. After crossing Daraa, Barut’s first major destination on the Jordanian border was the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem. In Jerusalem, he offered detailed insights into the locations he visited, introducing them to the reader and emphasising their importance in Islamic history. Following his time in Jerusalem, Barut proceeded to Halilurrahman, where he visited the mosque housing the tomb of Prophet Abraham and his family (

Barut 2022, pp. 42–45).

Barut’s next stop was Amman. Here, he stopped at a place called Rasulayn, which was allocated to pilgrims. Barut conveyed his views about the population and geographical features of Amman, and then shared his observations about the city. According to his writing, there was a notable mosque in Amman named after Hazrat Hussein; however, while this mosque was significant in name, it lacked other features. Because pilgrims used this mosque as a hotel, Turkish clerics also preached there (

Barut 2022, p. 49).

Amman became overfilled with pilgrims. Because entry visas to Saudi Arabia were stamped here, there was a huge crowd in front of the Saudi Arabian embassy and a long queue of people waiting for their visas to be stamped. It was also very difficult to find a toilet, to perform ablutions, and to pray. The police in Amman did not hesitate to take control of pilgrims who had lost their patience while waiting for their visa applications to be granted. Barut mentioned that the pilgrims suffered considerably every day of their stay in Amman. In that city, the only people who were happy were the street vendors (

Barut 2022, pp. 50–55).

Barut’s next stop was the town of Maan. Upon entering this small town, he observed that it resembled a site of ruins. The influx of hajj pilgrims into Maan significantly increased the town’s population and altered its atmosphere. Although the central mosque in Maan was relatively new and well maintained, Barut visited it during the evening prayer and found it overcrowded. He noted that the mosque was being used more as a shelter than a place of worship, with gas cookers lit and meals being prepared inside. In such a chaotic environment, Barut observed that little attention was given to prayer, ablution, or the general hygiene of the mosque. Men and women shared the same space, and the overcrowding made personal cleanliness and maintaining even a modest degree of personal space nearly impossible. He also described the mosque’s toilets as extremely unhygienic, making ritual purification and privacy difficult to uphold (

Barut 2022, pp. 56–58).

After leaving Maan, Barut and his group encountered a particularly challenging part of their journey: the crossing of the Jordanian desert. This part of the route, extending from Tokat, was among the most difficult due to the lack of paved roads. Instead, the travellers navigated by following vehicle tracks across the desert terrain. However, these tracks were often obscured or completely erased by sandstorms. To guide drivers, white canisters filled with stones were placed at intervals of approximately one hundred metres along the route, serving as rudimentary signposts. During the journey, Barut observed several buses stranded in the sand, others riding towards sand dunes, and people using shovels to dig out vehicles or pulling cars with ropes in efforts to free them from the terrain (

Barut 2022, pp. 58–62).

After a two-day desert journey, Mehmet Barut reached the last major stop in Jordan, Mudawwara, and then the first major stop in Saudi Arabia, Bir Ibn Hirmas. After short stays in these two cities, he arrived in the city of Tabuk. Here, Barut visited the mosque where the Prophet Muhammed prayed during the Tabuk Expedition (

Barut 2022, pp. 64–71).

Setting out from Tabuk, Barut stopped in the city of Khaybar on the route before finally reaching Medina. In this city, he visited the Masjid an-Nabawi, Jannat al-Baqi Cemetery, Uhud Martyrdom, Quba Mosque, and the Seven Mosques (

Barut 2022, pp. 82–93). After visiting Medina, Barut entered the state of ihram in the region of Dhul-Hulayfa, a few kilometres away from Medina, and continued on his way to perform the hajj.

Upon reaching Mecca, Mehmet Barut performed the hajj ritual, a section thoroughly detailed in his book. This section is notable not only for conveying the author’s personal reflections and emotional responses, but also for serving as a practical guide for prospective pilgrims. Barut provided explanations of the methods and principles involved in performing the hajj, and included direct quotations of surahs and prayers to be recited during the rites of worship (

Barut 2022, pp. 106–64). Thus,

Hicaz Yolları [Hijaz Roads] transcends a simple narrative of hajj experiences and functions simultaneously as a spiritual and instructional manual for pilgrims. This study, however, focuses specifically on Barut’s pilgrimage journey. The information he provides regarding the Hajj is of an instructive nature and serves an educational purpose. Comparable content can also be found in guidebooks intended to assist pilgrims.

4. Historical Hajj Pilgrimage Route and Mehmet Barut’s Pilgrimage

Following the analysis of the historical pilgrimage route during the Ottoman period and Mehmet Barut’s hajj route, this section focuses on the similarities and differences between the two. A key similarity lies in the use of land travel, which, despite being the most challenging mode of transportation, was necessitated by the extended duration of the journey and the physical needs of the pilgrims. Given the length of the journey, pilgrims must stop at service points to meet basic needs such as accommodation, food, water, and shopping. In addition to fulfilling these practical requirements, the pilgrimage route traditionally includes visits to sites of historical and religious significance, including the tombs of prominent Islamic figures (

Armağan 2000, p. 99). Barut’s journey reflects this same pattern: he not only paused to rest and meet his physical needs, but also visited historical and religious sites along the way. Due to the impracticality of sleeping on the bus during such a prolonged journey, longer stops were essential. These were often made in locations of religious importance, allowing Barut to combine rest with worship and cultural engagement. Thus, his travelogue illustrates how the route served both functional and spiritual purposes, consistent with traditional hajj journeys.

The most impressive aspect of the similarity between the hajj journey made by land during the Ottoman period and Mehmet Barut’s hajj journey is the following of almost the same route. This shows that Barut’s hajj pilgrimage route is parallel to the historical hajj pilgrimage route followed by groups of merchants as caravans. Although the hajj journeys start from different points, both routes pass through Anatolia. One journey starts from Uskudar, Istanbul, in the Bosphorus region (

Armağan 2000, p. 82), while the other starts from Turhal, Tokat, in the Black Sea region (

Barut 2022, p. 14). Although their starting points are different, both journeys merge at Konya in the Central Anatolian region of Türkiye.

During the historical hajj pilgrimage in the Ottoman period, Konya was a city where pilgrims stayed and met all their needs. In the meantime, they visited the tomb of Mevlana Celaleddin-i Rumi (

Armağan 2000, p. 86;

Bektaşoğlu 1992, p. 32). Mehmet Barut’s next stop after Ankara was Konya (

Barut 2022, p. 17). He also continued his pilgrimage by visiting Mevlana’s tomb in this city.

The hajj pilgrim caravan, which set out of Konya to the southeastern Anatolia region during the historical pilgrimage, reached Antakya via Adana. Antakya was a very important location for hosting the caravans travelling from Istanbul to Damascus, so it was the best serving point for all hajj pilgrims. During the historical pilgrimage, the Habib-i Neccar Mosque, located in Antakya, was also visited by pilgrims. It was named after Habib-i Neccar, whose tomb was located in the mosque (

Armağan 2000, p. 90). Mehmet Barut first visited the Ashab al-Kahf in Tarsus during his pilgrimage and then headed towards the Antakya region. His visit here was to the tomb of the Bayezid-ı Bistami (

Barut 2022, p. 24). Although Barut did not visit the Habib-i Neccar Mosque and its tomb, he followed the route by passing through the same places and regions where the historical hajj pilgrims had passed.

The most important stop for the historical pilgrimage from Istanbul to Mecca was the city of Damascus. In the words of

Nir Shafir (

2020, p. 1), “Damascus was the key to the creation of an Ottoman holy land between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, because Damascus was the gateway to the hajj”. During the Ottoman period, the tombs of companions and saints such as Muawiyah, Bilal-i Habeshi, Atike, Zeynep, Rukiye, Muhyiddin-i Arabi, and Abdulgani Nablusi were visited (

Armağan 2000, pp. 91–92). Mehmet Barut first stayed in Aleppo and then in Damascus during his hajj pilgrimage. He also visited the tombs of the Muslim leaders and figures in this city (

Barut 2022, pp. 36–37).

During the historical pilgrimage, there were four stopovers following Damascus before reaching Maan. This was a well-equipped rest area where hajj pilgrims could sleep and recover during the Ottoman period. Maan, which provided the opportunity to meet all needs due to its proximity to Halilurrahman, attracted the attention of pilgrims with its meat and fruit markets (

Armağan 2000, p. 94). Mehmet Barut stayed in Jerusalem after passing through Damascus (

Barut 2022, pp. 42–45). Although this city was not part of the official pilgrimage route during the Ottoman period, it is known that hajj pilgrims stopped here, as noted in the book menazil-i hajj. Sufi poet Ahmet Fakih, who authored the oldest pilgrimage hajj travel journal known in Turkish literature, visited Jerusalem, following the Damascus route and then reached Mecca for hajj in the 13th century (

Eroğlu Memiş 2020, p. 271). Additionally, a female poet with the pseudonym Servet in the 16th century (

Donuk 2017, p. 21); an author with the pseudonym Kadri in the 17th century (

Kiraz and Tiryaki 2023, p. 118); Evliya Çelebi (

Gemici 2021, p. 158), one of the famous divan poets known as Nabi in the 18th century (

Coşkun 2002); and one of the Anatolian Sufis Abdullah Mekkî Erzincanî (

Doğan Turay 2019, p. 123) in the 19th century visited Jerusalem, passing through Damascus and continuing their journey to perform hajj in Mecca. Mehmet Barut also visited Jerusalem before reaching Maan in the 20th century. After passing through Maan, he followed the direction of Tabuk, finally reaching Medina. Barut’s journey followed the same route as the historical hajj pilgrimage. Therefore, as in the historical pilgrimage, Barut first reached the city of Medina and then Mecca for performing hajj.

However, it was noted that there were differences between the historical pilgrimage route during the Ottoman Empire period and Mehmet Barut’s hajj pilgrimage route. Historical hajj pilgrims during the Ottoman period used animals such as horses, mules, donkeys, and camels for transportation. Mehmet Barut, on the other hand, made his hajj journey by bus as a modern means of transportation. In this case, the original route—designed for animal-drawn transport—was not suitable for modern vehicles, resulting in differences between the historical route and that of Barut. In historical hajj pilgrimages, the roads were made according to the needs of caravans and animals, so the routes were determined accordingly. Although the routes remained closely coordinated, the roads used by modern vehicles differ due to engineering reasons. Thus, the roads used by Barut were not exactly the same as those of the historical hajj pilgrimage route.

Journeys on mounted animals took significantly longer than those made by bus, resulting in a much greater need for rest during hajj journeys. Therefore, while there were many stops during historical hajj pilgrimages in the Ottoman period, there were fewer stopovers in on Barut’s hajj journey.

Another factor contributing to the changes in stopover locations was the emergence of international border gates. During the historical hajj pilgrimage, all territories from Istanbul to Mecca were under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, eliminating the need for border-specific accommodations. However, In Barut’s hajj pilgrimage, the border gates between the countries meant that stopovers and accommodations became mandatory due to visa procedures. Departing from Tokat, Barut entered Syrian territory through the Cilvegözü Border Gate in the Reyhanlı district of Hatay. Because of mandatory border stops, he was required to travel through Syria, enter Jordan via its border control, and continue onward to Saudi Arabia. These visa procedures and border checks significantly delayed the journey; Barut himself described border controls as the most challenging aspect of the pilgrimage. Consequently, border gates led to the development of service areas and accommodation for hajj pilgrims. For instance, following visits to Jerusalem and Hebron (Halilurrahman), Barut’s bus remained in Amman and later in the capital of Lebanon for several days, awaiting visa stamps and border clearance.

During the Ottoman period, the hajj pilgrims travelled on land out of necessity, since there were no modern means of transportation. After the mid-1800s, the Suez Canal was built, and the hajj pilgrims in the Ottoman Empire started their journey from Istanbul, travelling by steamships and passing through the canal to reach the holy lands of Mecca and Medina. After the Hijaz Railway was built in 1908, train journeys became widespread among the hajj pilgrims who used the railway from Istanbul to Medina (

Şahin 2021, pp. 193–207;

Kahraman 2017, p. 45). There was no need for Barut to travel by bus, as modern means of transport were available in 1967. Moreover, due to safety concerns, the government advised against travelling by bus (

Kırmıt 2025, p. 135). After 1947, hajj journeys from Türkiye were mainly made by air. However, Mehmet Barut chose to travel by bus, motivated by a desire to preserve the culture of the historical pilgrimage and to experience the nostalgia associated with the hajj journeys of the Ottoman era. Additionally, it is believed that the challenges faced by the hajj pilgrims during the journey and visiting the graves of those companions and saints are rewards and acts of worship.

5. Mehmet Barut’s Hajj Journey as a Travelogue

Travelogues are pieces of writing about travelling to or in particular places for specific purposes in which a person describes the places he/she visits. In this section, Mehmet Barut’s book, Hicaz Yolları [Hijaz Roads], will be analysed by making connections to the hajj travelogues in Turkish literature. The reason for analysing Hicaz Yolları lies in its distinctive content and context compared to other hajj texts. Barut’s work uniquely combines a detailed account of the hajj journey with comprehensive explanations on how the pilgrimage is performed. Furthermore, the text incorporates his personal reflections, emotions, and spiritual experiences throughout the journey. This integration of travel narrative, religious guidance, and personal devotion sets Hicaz Yolları apart from other hajj writings and contributes to its significance.

In order to better analyse Mehmet Barut’s book in terms of literary genre, it is important to examine the hajj travel books in Turkish literature.

Menderes Coşkun (

2009, p. 14) classified the Ottoman period travel books under seven subheadings, one of which was hajj travel books. In another article,

Coşkun (

2002, p. 6) further grouped hajj travel books according to their content and purpose of writing into the following four groups: hajj handbooks, hajj travel books with a professional guide, professional hajj travel books with memoirs and reports, and literary hajj travel books.

The first group of hajj handbooks are known as menazil-i hajj and menasik-i hajj. In Turkish literature, these are the only types of handwritten hajj travel journals and diaries. Menazil-i hajj are texts that cover the routes of the hajj journey and introduce the places and stopovers, and share the experiences of pilgrims’ hajj journey. Menasik-i hajj are texts containing written instructions and procedures relating to the hajj ritual. These types of texts were written with the purpose of guiding the hajj pilgrims and are based on written sources rather than personal experiences. The second group, the guide hajj travelogues, are texts in which personal adventure stands out compared to the texts in the first group. The most significant difference between the first group and the second group is that authors in the second group personally experienced the hajj pilgrimage. Moreover, even the titles of the guide-style hajj travelogues were chosen by the authors themselves, further confirming their authorship. The third group, memoir and report-type hajj travelogues, are texts written by the author with the purpose of making a report for an institution. The texts in this group are different from the first two groups in terms of their titles and the purpose of their writing. The fourth group, the hajj travelogue as a literary genre, are texts that are not written to guide pilgrims but instead stand out for their literary context. Such texts are generally written in poetic ways. Poems are written in prose and other types of poetry are added to maintain the poetic quality (

Coşkun 2002, pp. 6–51).

Mehmet Barut’s Hicaz Yolları [Hijaz Roads] recalls menazil-i hac texts in that it provides detailed information about the stops and pilgrimage sites encountered during the journey. In addition to narrating his journey to Mecca, Barut also draws upon the menasik-i hajj tradition by providing guidance on how to perform the hajj rituals. However, Barut’s travelogue entitled Hicaz Yolları is not a conventional example of menazil-i hac or menasik-i hajj literature. This is because such texts are written with the purpose of informing readers about the stations and the proper performance of the pilgrimage rituals. Moreover, in these types of texts, it is often unclear whether the author wrote the book based on an actual pilgrimage journey. The group of pilgrimage travelogues most closely related to Mehmet Barut’s Hicaz Yolları are guide-style hajj travelogues. This is because Barut wrote Hicaz Yolları by incorporating his real-life experiences from his hajj journey into the narrative, and his personal experiences, feelings, thoughts, reflections, and evaluations during the journey and the hajj ritual were projected. Although Barut aimed to guide Muslims who would go on the hajj after him, he narrated his personal memoir during his hajj journey and the hajj ritual. According to the classification of pilgrimage travelogues, Mehmet Barut’s Hicaz Yolları cannot be included in the third category, as it was not written with the aim of reporting to an official or institution. The fourth group of pilgrimage travelogues is related to Barut’s Hicaz Yolları, because the author personalises the text by incorporating his own observations and evaluations, indicating that Hicaz Yolları is not entirely detached from the fourth category, which consists of travelogues written with a literary purpose.

It is evident that Barut’s travelogue cannot be categorised within the framework of the traditional classification. Barut’s travelogue should be evaluated separately among the travel books within Turkish literature during the Republican period, taking into account the period in which it was written. This is because the categorisation of hajj travel books in Turkish literature has traditionally been based on travel writings from the Ottoman period and divan literature. However, in modern Turkish literature, the form and content in hajj travel books have changed significantly. There are several reasons for this change. The first is the transition from land to air travel in Türkiye, beginning in the 1940s. Since the development of modern means of transportation, very few, if any, menazil-i hajj writings have been published (

Coşkun 2001, p. 190).

Published hajj travelogues provide clear examples of how these writings evolved during the Republican period. Mehmet Hulusi Efendi, a cleric like Mehmet Barut, travelled from Istanbul to Jeddah by plane in 1949. However, Hulusi Efendi’s hajj memories began with a plane journey (

Kara 2020, pp. 49–52). Cultural and art historian

Emel Esin (

1960, p. 6) wrote her hajj memories in a literary-style in her book

Lebbeyk-Hacc Hâtıraları [Lebbeyk-Hacc Memories]. Her hajj memories also began with a plane journey.

Necip Fazıl Kısakürek (

1973, pp. 5–13), one of the most well-known poets of Turkish literature during the Republican period, narrated his hajj memories in his book,

Hac’dan Çizgiler, Renkliler ve Sesler ve Nur Mahyaları [Lines, Colors and Sounds from Hajj]. Kısakürek’s hajj memories began with the visa procedures—he went to the embassy for visa stamps in Ankara, and he continued with his observations and impressions at Yesilkoy airport. Poet and author

Mustafa Yazgan (

1978, pp. 12–17) recounted his memories of the hajj pilgrimage in his book titled

Ömrümün Devr-i Saadeti Hac Hatıraları [Hajj Memories of the Age of My Life]. Yazgan, who flew from Ankara, the capital of Türkiye, to Jeddah, began writing his memories of the hajj pilgrimage on the plane. Journalist and writer

Ahmet Sırrı Arvas (

2004, pp. 17–18) recounted his memories of the hajj pilgrimage in his book titled

Hikâyeci Gözüyle Hayatı Değiştiren Yolculuk [A Journey That Changed His Life Through the Eyes of a Storyteller]. At the beginning of his book, Arvas included a flashback to his childhood, recounting his early pilgrimage journeys, which he undertook by bus and ferry. However, he also later made his hajj pilgrimage by plane. Another author from recent times,

Serap Şirin (

2006, pp. 15–18), recounted her memories of the hajj pilgrimage by plane, taking off from Ankara Esenboga airport and landing at Jeddah airport.

Another reason for the change in the hajj travelogues is that poetry has been replaced by prose in modern Turkish literature. Old Turkish literature, or divan literature, is a form of poetry primarily associated with Ottoman traditions. Therefore, all travelogues were written in the literary style, often lyrical in nature and including a rich collection of verse. However, in modern Turkish literature, which was influenced by Western European styles, prose gained more popularity and surpassed the old version of literary-style divan literature. From the 1870s onwards, leading writers of Turkish literature such as Şemsettin Sami, Namık Kemal, Samipaşazade Sezai, and Recaizade Mahmut Ekrem wrote stories and novels (

Kudret 1998). Within the realm of travel literature, the prose works of Ubeydullah Efendi’s

Amerika Hatıraları [Memories of America], Cenap Şahabettin’s

Avrupa Mektupları [European Letters], Ahmet Haşim’s

Frankfurt Seyahatnamesi [Frankfurt Travelogue], Ahmet Rasim’s

Romanya Mektupları [Letters from Romania], Reşat Nuri Güntekin’s

Anadolu Notları [Anatolian Notes], and Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar’s

Beş Şehir [Five Cities] constitute significant examples (

Maden 2008, pp. 152–54). When we examine hajj travelogues specifically, Cenap Şahabettin, despite being a poet, wrote his book

Hac Yolunda in prose as an example of a literary hajj travelogue. The poet, who sought ways to achieve artistic prose in his work, produced a hajj travelogue that demonstrates the power of his art rather than his memories (

Cenap Şahabettin 2022, pp. 17–18).

Another significant point about hajj travelogues in modern Turkish literature is that, particularly during the Republican period, the genres of memoirs, travelogues, and diaries were more defined in terms of structure and boundaries, and numerous examples were produced. This also influenced the titles and content of the hajj memoirs in literary genres. Thus, during the Republican period, old version of titles such as menazil-i hajj and menasik-i hajj, commonly used in classical Turkish literature, were no longer available. Instead, writers began to title their travel writings with modern expressions such as hajj memories, hajj journey, hajj travelogue, and hajj diary.

6. Conclusions

Before the use of modern means of transportation, travelling by land was a part of the hajj pilgrimage for Muslims. There are two key reasons underlying the connection between pilgrimage and worship. The first is that pilgrims endure challenges such as inadequate accommodation, security concerns, physical exhaustion, and as harsh travel conditions in their devotion to fulfilling the hajj pilgrimage. The second reason is the religious significance of visiting historical sites and the tombs of Islamic leaders along the hajj pilgrimage route. Therefore, hajj pilgrims often begin acts of worship during the journey and endure the hardships they encounter along the way.

During the Ottoman period, Muslims made pilgrimages on the Istanbul–Damascus–Mecca route by road. After this, they travelled by sea and then by rail, which made their journey easier and shorter. Twenty-four years after the foundation of the Republic of Türkiye, hajj pilgrimages began to be mainly made by air. Thus, the hajj pilgrimages that took months by bus were no longer preferred, since travelling by air only took a few hours. Data from the Saudi Arabian General Authority for Statistics, cited in the introduction, indicate that changes in transportation preferences are not only applicable to Türkiye but are also observed across the broader Muslim world. While travelling by air has made hajj pilgrimages easier and shorter, the traditions and habits of visiting historical and spiritual places en route have disappeared over time. As a result, modern life—particularly the use of air travel—has limited the opportunity for continuous worship throughout the pilgrimage journey, confining most acts of worship to the designated hajj ritual sites. However, those who oppose the individualism of modern life will continue to preserve the tradition of continuous worship throughout the pilgrimage journey. Mehmet Barut, a cleric, is just one example of such people.

Literature has always reflected the rhythms of life, and for Muslims, hajj pilgrimages lasting for days were an integral part of life. However, the decline in interest in long hajj journeys has led to changes in the content of hajj travelogues. Authors of hajj pilgrimage travelogues during the Ottoman Empire described both hajj rituals and experiences of hajj journeys. The Ottoman-era pilgrimage route discussed in the second section has been determined based on these travelogues. After the 1940s in Türkiye, authors of pilgrimage travelogues have generally confined their narratives to the Mecca and Medina regions. Mehmet Barut’s hajj travelogue Hicaz Yolları [Hijaz Roads], published in 1967, was considered valuable because it was a reminder of hajj pilgrimages made during the Ottoman period. Within this framework, the findings presented in the first and second sections indicate that Mehmet Barut, most of the time, remained attached to the Ottoman hajj pilgrimage route when performing his pilgrimage. Although one route began in Istanbul and the other in Tokat, both converged in Konya and continued toward Damascus. Out of Konya, the cities of Antakya, Damascus, Maan, and Tabuk are locations where Barut’s hajj pilgrimage route crossed with that of the Ottoman’s. At those destinations, there are historical buildings, places of worship such as historical mosques, and the graveyards of Muslim scholars where Barut visited in the same way the Ottoman’s pilgrims visited in the past. Unlike the historical pilgrimage route, Barut travelled to the cities of Jerusalem and Halilurrahman. The travelogue examples cited in the third section demonstrate that pilgrimage journeys including a stopover in Jerusalem were undertaken. The factors distinguishing Barut’s journey from the historical pilgrimage route are the use of motorised vehicles instead of pack animals and the presence of border checkpoints between countries. These factors have altered the number of stops made during the journey. Despite the differences that have emerged, Barut’s journey serves as a clear example of collective memory. Despite the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the establishment of the Republic of Türkiye, the passage of a century, and the adoption of modern transport, the collective memory of Anatolian Muslims has been preserved. Mehmet Barut, as a cleric, followed the footsteps of his ancestors to keep this collective memory alive.

Mehmet Barut’s desire during his hajj pilgrimage was to evoke nostalgia for the past and to keep traditional practices alive. Although modern transportation had become widespread, Barut chose to travel by bus. While a challenging journey for him, it nonetheless offered a unique perspective in terms of modern hajj pilgrimage travelogues. The exemplars presented in the fifth section illustrate that pilgrimage travelogues composed during the Republican period predominantly commence and conclude at the airport, this reveals that hajj pilgrimage travelogues, spanning from the 13th century to the early 20th century during the Ottoman period, underwent significant changes over time. One of the consequences of this change is that, as a result of the loss of interest in and need for pilgrimage mansions, texts in the menazil-i hajj genre were no longer written. Moreover, the increasing focus on prose writing and the influence of Western European literature on Turkish literature led to changes in content, with the genres of memoirs and travelogues playing a significant role in this transformation over time. However, Mehmet Barut’s Hicaz Yolları [Hijaz Roads] was inspired by and built upon tradition. Although written during the Republican period, it was handwritten and reflected characteristics of both menazil-i hajj and menasik-i hajj, while also aligning with the prose style of modern Turkish literature. Hicaz Yolları stands out from other hajj pilgrimage travel books written during the Republican period; while it is a modern work, its content and style closely resemble the hajj travelogues of the Ottoman Empire, presenting them in a contemporary form.