Abstract

From an outside perspective, it is not clear whether the Catholic Church is an active digital entity, or at least, it is not perceived as such. This paper analyses this issue. The methodology involved the monitoring of ecclesiastical Internet activity, SWOT analysis and in-depth interviews (seven) with clergy and technological suppliers of the Church in both Spain and Latin America. Results: Catholic Church digitalisation is spontaneous, as a reflection of society at large, and is heterogeneous due to its decentralised management. There is more inner acceptance of digital mediatisation for proclamation or support in faith (i.e., apps for praying) and less acceptance for the digitalised practice of rites (digital mediation in the celebration of sacraments is an open debate); however, the presence of ICTs in sacred places is increasing (i.e., liturgical books on screen). The evangelisation of the digital continent is an objective of the Church, whereby clergy influencers are the most striking but less solid case. There is almost full digital implementation at the functional level (i.e., digitised accounting and archives). Only charitable action with vulnerable groups remains analogue. Polarisation is also present, as ultra-Catholic groups are over-represented on the Internet. Conclusion: The Catholic Church is integrated in the Information and Digital Age but is also concerned with spiritual impoverishment, as online fragmentation does not feed real humanitarian communities.

1. Introduction and Literature Review

Digital implementation is becoming more homogeneous regionally speaking that in its implementation by sector; i.e., citizens across the world use their digital devices or surf the Internet in similar ways, while the media sector presents much greater digital transformation than, for example, the healthcare sector.

For the last 7 years, at the start of my course on digital society, I have asked students about their perception of the degree of digital implementation in various sectors, and the Church invariably comes last. The informal replication of this longitudinal survey in other population groups yields similar results. Does this perception of the social imaginary correspond to the level of digitalisation that religion is experiencing today? More specifically, how is the activity and presence of the Catholic Church on the Internet characterised today? Given the breadth of the phenomenon to be addressed, the aim is to present a general snapshot of the variety of digital resources and practices in the field of the Catholic Church in Spain today, with some reference to Latin America as well, and to analyse their impacts at different levels with the help of expert opinions: parish management, support for believer communities, announcements and celebrations of the faith.

A review of the scientific literature on the subject shows that this paradigm shift towards digitalisation has led religions and their institutions to renew their way of existing and expressing themselves in today’s world. Sbardelotto (2012) explains that the religious phenomenon is becoming more complex through new temporalities, new spatialities, new materialities, new discursivities and new ritualities, which globally pluralise the notion of religiosity (Sbardelotto 2016). The same author sees both positive and negative aspects in this complexity; it is due to this ambiguity that most researchers define the role of religion in a digital society as a challenge (Berzosa Martínez 2016; Tridente and Mastroianni 2016; Stępniak 2023). Among the negative aspects, it is indicated that hypermediatisation can lead to the incorrect framing of religious content in the media (Pérez-Latre 2012; Korpics et al. 2023); however, Pérez-Latre (2012) himself also indicated that networked communication provides an opportunity for any Catholic individual or community to express themselves in the public sphere, thereby breaking the monopoly on news and content production, which, in pre-Internet times, rested solely with political or media elites (Mattoni and Ceccobelli 2018). Korpics et al. (2023) highlighted that an existing offline community can strengthen its ties if it also has online relationships (e.g., a Facebook group account), which can strengthen its spiritual practices (Korpics et al. 2023).

Some authors highlight the new pastoral methodologies provided by digital tools (Arboleda Mota 2017), and others conclude that social media platforms are underused; for example, Fandos Igado et al. (2020) explained that when Spanish clergy use social media platforms in their ministerial work, they are active on social media platforms that are less frequently used by young people, which means that their use of social media for pastoral actions is limited and insufficient. This may explain Díez Bosch et al.’s (2017) results, which confirmed the low use of digital religion tools by younger users, together with new ways of envisaging religion by young people nowadays (Micó-Sanz et al. 2021).

The changing environment has driven digital change within the Church, but additionally, the Church itself proposes the Internet as a space for and means of evangelisation (Tridente and Mastroianni 2016; Arboleda Mota 2017; Fandos Igado et al. 2020), with the following advantage: by showing the Church as a socially engaged institution through new media, the Church can improve its weakened reputation (Stępniak 2023). Alongside this, questions continue to be raised, for example, about the meaning and effectiveness of pastoral authority on the Internet (Arboleda Mota 2017).

When reading scientific literature on digitalisation in the Church, one may come to think that religion today is only experienced on the virtual plane. It seems that the digital effervescence of this century is unconsciously transferred to the research of the topic itself. That is why we find so necessary Evolvi’s claim for the integration of material and spatial approaches to aid in a better understanding of the study of digital religion (Evolvi 2022). In our analysis, we do not forget that religiosity still exists offline.

We have not found studies that present an overview of the state of digitalisation of the Catholic Church in Spanish-speaking countries at different levels (celebration of sacraments, proclamation of the faith, support for believers, administrative management, etc.) and that also relate it to the Church’s position with respect to technology. This research attempts to address this gap.

1.1. The Church’s Position on Technological Change

In his encyclical Redemptor Hominis, John Paul II (1979) welcomed technological progress but indicated that its growth had to be accompanied by a proportional development in Christian morals and ethics.

Benedict XVI, as Pérez-Latre (2012) explains, created the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of the New Evangelisation in 2010, with the challenge of finding new means of evangelisation in the face of the progressive secularisation of society.

Pope Francis (2015), in his encyclical Laudatio Si’, stated that “Humanity has entered a new era in which technological power places us at a crossroads. We are the heirs of two centuries of enormous waves of change (…) information technology and, more recently, the digital revolution, robotics” (Pope Francis 2015, p. 79); at this intersection, he expresses both the joy and gratitude that these advances bring but also warns of the danger they pose. The text denounces the fact that current digital technological development gives great power to those who have the knowledge and money to use it and highlights the risk of it being concentrated in a few hands. Regarding these divides, Berzosa Martínez’s (2016) classification is illustrative; the author differentiates between the unconnected and the connected populations and, among the latter, distinguishes between the cyber-rich and the cyber-poor, with the cyber-poor being those who “only participate in the technological crumbs of the former” (Berzosa Martínez 2016, p. 34).

Furthermore, Pope Francis’ encyclical letter points out that human beings do not always know how to use their power/progress correctly and, above all, do not know how to set limits on it. The Pope emphasised the fact that the objects produced by technology are not neutral because they condition lifestyles and are so dominant that “it is very difficult to use them without being dominated by their logic” (Pope Francis 2015, p. 85). Within the framework of this logic, the fragmentation that invites a reductionist view and the transience that hinders the depth of life and coexistence are also denounced. With regard to artificial intelligence, the Vatican document Antiqua et nova (Pope Francis 2025) recognises that AI can boost key sectors, but above all it stresses that this progress must not deepen social inequalities. It also warns that AI is not a moral agent and therefore should not replace humans in decision-making, as this would lead us away from ethics.

The Spanish Episcopal Conference (CEE 2021) also discussed digital transformation at three intertwined levels, namely technological, economic and cultural, and indicated that “The new technological revolution, based on the data provided by digital users and artificial intelligence, is giving rise to what some call a moralistic capitalism that not only regulates production and consumption, but also imposes values and lifestyles” (CEE 2021, p. 17). The text adopts the concept of the digital swarm (Han 2016) to explain that the digital ecosystem is only a sum of isolated individualities that can communicate on the network but do not become a true community. In summary, the Spanish Episcopal Conference (CEE 2021) argues that the new digital empire causes spiritual impoverishment (CEE 2021, p. 18).

All of the above connect within the concept of a liquid society (Bauman 2003), which is characterised by the replacement of solidity (of relationships, principles, etc.) with liquidity (inconsistency), which leads to precarious human bonds and an individualistic society. However, warning people of these dangers does not mean giving up on technology—“No one wants to return to the cave age, but it is essential to slow down and look at reality in a different way”—but rather acting: “What is happening makes it urgent for us to move forward in a courageous cultural revolution” (Pope Francis 2015, p. 90).

2. Methodology

As a starting point, we asked ourselves whether the Church is an active digital entity or not, and we wanted to clarify this because it is not perceived as such by the collective imaginary. The topic is empirically approached (García Ferrando et al. [1986] 2003): from a qualitative perspective, we follow a logical inductive process and take the facts to draw our conclusions, and with this in mind, we carry out a descriptive analysis of uses and practices, as well as an explanatory analysis supported by interviews.

Catholics surf the web in search of useful information and answers to questions surrounding their faith. There are hundreds of Catholic websites all over the internet, if not thousands of them. To choose the most representative websites, multimedia platforms and social media accounts, we asked our sample of experts as well as an internet search engine itself. Monitoring took place from November 2024 to March 2025, paying particular attention to the purpose of the published content, i.e., celebration of the faith, support for spirituality active communities or first announcement for non-believers. We present an overview of this in Section 3, in which we detail and categorise the digital tools used by Catholic communities and the Church in Spain with some reference to Latin America.

This research is not just about monitoring and presenting online religious resources and practices but also about analysing if this whole digital shift is positive or negative for spirituality. To achieve this objective, this research included seven in-depth interviews with the following people: three parish priests from different autonomous communities in Spain (two cities and one village), one of whom is also the director of a primary and secondary school; one parish priest in Mexico who is the co-founder of a pioneer Catholic news agency on the Internet; one priest secretary to a bishop who is also a pastoral subdelegate of the diocese of Madrid; and the president (layperson) of a parish brotherhood. Some of them declare to be daily active tech users, some of them moderate users and one of them very low-level tech user. The CEO and founder (layperson) of a specialised parish management software of Spanish origin and implemented in more than 25 countries, most of which are Spanish speaking, was also interviewed. Therefore, we compared the perspective of an external professional, a digital services supplier who introduced a technological tool to the Church, vs. the perspectives of the tool’s users and members of the Church.

The approximate age range of the lay informants was 40–75, and that of the clergy was 40–65. Part of the sample was identified in the public sphere, and the other was recruited using the snowball sampling technique. Therefore, we used a convenience sample (Igartua Perosanz 2006) that gathers heterogeneous profiles, and as we used so-called heterogeneity variables for the sampling process, the data collected were considered valid because the set of interviews achieved sufficient redundancy. However, as always when working with qualitative samples, we must be careful not to overstep our bounds when drawing conclusions.

Opinions on faith and technology represent such a complex and deep subject that no technique other than in-depth interviews could have been used to obtain relevant information. The interviews lasted on average 1 h; some were conducted face-to-face and some were technologically mediated, but all of them properly registered. The transcription of the answers was analysed with the SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) tool, considered to be the most appropriate method to analyse how positively or negatively online religious practices and virtual religious communities’ activities affect spirituality.

In addition, a comparative exploration of the number of followers of the social media accounts of different of bishops’ conferences in Latin America was carried out (Section 3.3).

Regarding the methodological weaknesses of this study, a gender bias is noted: the entire interview sample was male, which is partly logical because in the Catholic religion, only men may impart sacraments and only men can be the head of parishes and dioceses, and it is they who decide what technological tools to implement for the functioning of the Church. Another weakness to highlight is the “good subject effect” detected in one participant in the sample.

As a guide for conducting the research, the following hypotheses were defined:

H1.

Digital technology does not have a transformative impact on the Catholic faith or spiritual beliefs as it has had in other areas in society (media, citizen participation); however, it does leave a recognisable mark as a set of facilitatory tools for the most everyday and instrumental aspects of Church life (i.e., management).

H2.

The institutions and subjects that lead and sustain the Catholic religious world in today’s Western societies find in digital tools support to connect with their communities in a place and time where faith and beliefs have developed from a social obligation to a personal choice.

H3.

The degree of permeability to digitalisation in the religious and spiritual world is related to some personal and/or cultural characteristics, which is why we find more reluctance to implement technologisation at the institutional level than at the personal level.

3. Descriptive Analysis of Digital Practices in the Church

This section identifies the main types and uses of digital tools in the Church today. Given the breadth of existing practices, it is not intended to be an exhaustive census, but it does provide a broad outline of the intersection of the Church and the Internet.

3.1. Presence of the Church on the Internet: Catholic Media and Websites

The digital practices presented in this section offer content (information and resources) and mediatised liturgical events from an unidirectionally communicative perspective; therefore, users are only audiences. We distinguished two types: online news media outlets and overall content websites.

Catholic digital media outlets are characterised by offering general news from a Catholic perspective and/or religious news, and each media outlet provides information and doctrine in different proportions. As a typical hybridisation with new media, these Catholic digital media also combine formats (written news, podcasts and audiovisual broadcasts); examples would be the Vatican News multiformat platform (vaticannews.va) and the well-consolidated Spanish religiondigital.org. There are also long-running online television and online radio channels, both Spanish and Latin American, such as vidanuevadigital.com, ewtn.com/es/tv and ewtn.com/es/radio, which attract global audiences and broadcast a variety of genres, including live news programmes, documentaries, magazine programmes, broadcasts of liturgical events (i.e., mass masses), etc., with all content being faithful to the Church’s teachings. These multimedia platforms coexist with single-format online media, for instance Catholic digital presses, some of them as old as the Internet itself, e.g., hispanidad.com, revistaecclesia.es and alfayomega.es. Sometimes, traditional broadcast media, such as Radio María, commit to technological renewal, so radiomaria.es remains accessible via FM/DAB and DTT but now also via mobile apps, YouTube and smart speakers. Within these digital media outlets, we also include virtual Catholic news agencies. A pioneering example of this is zenit.org, which has been active since 1996, as well as aciprensa.com, which provides extensive coverage specialised by region; both examples are offered in a variety of languages. Another variant of the new media is Catholic cinema streaming platforms, examples of which include boscofilms.es or formed.lat; both are VOD (video on demand) platforms with audiovisual entertainment content that aims to promote a lifestyle and values aligned with the Catholic faith.

The aforementioned media outlets, following the digital logic of hyperconnectivity, also entail social media profiles and give users the chance to the received personalised newsletters by previous subscription. The Internet gives the media the possibility of scaling their audiences, as reported by one of the co-founders of the ZENIT news agency, an informant in this research sample: “The first day we sent 400 emails [using the list of the Vatican press office for disseminating its press releases], and in three years we already had four million users” (Informant 5).

As characteristic features of these Catholic media outlets, we find that (1) in addition to up-to-date information, they also offer documentary repositories—speeches by the Pope, homilies, sacred books, texts from Synods, prayers, etc.—forming a whole battery of reading resources that can be used to strengthen spiritual life; (2) they offer special content based on the Catholic liturgical calendar (e.g., lent prayers); and (3) the offering of 37 languages and a dozen alphabets available on vaticannews.va is not the norm, but varied language availability is frequent.

A second large category of Church presence on the Internet is overall religious content websites, the most popular of which is the Vatican website vatican.va, which is offered in several languages, hosts millions of daily visits, and is an important source of documents (major and minor papal documents, curial documents, papal speeches, etc.) and overall Vatican information (not to be confused with the Vatican news website, the multimedia platform with daily updates). There are dozens of Catholic portals, almost all of which offer resources (such as those already mentioned for the media outlets) and consultation on topics of interest (bible, family, pope, etc.), formation, community faith practice options (meeting and prayer groups), professional advice from a religious perspective (Catholic psychologists or jurists) and personalised online guidance on spiritual, moral and doctrinal matters. As it is impossible to mention them all, we primarily cite catholic.net due to its longevity and being one of the most complete. We also highlight websites specialising in digitalisation, such as the portal riial.org, a network of digital pastoral agents that, since the 1990s, has pioneered guiding religious congregations and Catholic institutions in the computerisation and use of new technologies in the mission of the Latin American Church. The equivalent website in Spain with the same mission is planalfa.es, the ICT (information and communication technology) portal for Catholic institutions in Spain. We have not forgotten about blogs, of which there are many with religious themes, but we will not focus on these, as they tend to contain markedly personal visions.

The common goal of all these virtual spaces related to the Church is to occupy their own space on the Internet, a key factor in our increasingly secularised world where a believer does not easily find content aligned with a Catholic way of thinking, where the convinced believer can find what they are looking for and where a person with doubts can perhaps find an answer to their concerns.

Regardless of ownership, some Internet sources emanate from ecclesiastical institutions, while others are independent. Many of the named resources in this subsection are free to use, but a donation option is always available.

3.2. Digital Tools for Work in Church Institutions

This group of resources refers to digital tools used by the clergy to attend “office” occupations. Generally, they contain the following functions: accounting and reception of donations (regular donations from offertories, special collections, collection of offering baskets and payments for events); the organisation of events, e.g., spiritual retreats (announcement, registration and attendance tracking); informative communication by means of newsletters and mass or selective online messaging (reminders of celebrations, etc., e.g., Week of Prayer for Christian Unity); organisational communication (sacramental order forms, coordination with lay people to share online calendars and working documents, e.g., catechetical materials); service planning (synchronised sharing of scriptures and songs); and reporting (accounting report for the government’s Ministry of Finance or activity reports for the diocese). Among these resources, ecclesiared.es, an ecclesiastical management software of Spanish origin that is used in 25 countries, stands out for its high level of international implementation. The specialisation of a Church management software is relevant due to the financial peculiarities of the Church (donations, taxes) and its events. In contrast to the free resources described in the previous section, gratuity is now less widespread; not all but the majority of resources are from privately owned companies, so they need to market their products. By monitoring different companies that offer religious technological services, it has been observed that in those of Anglo-Saxon origin, more commercial language is used when advertising their software, e.g., empowerment, personalisation, revitalisation, or strategies (tilmaplatform.com). Even those created within the Church institution (e.g., AlfaIglesia; ecclesiastical office) ask for contributions through donations because the technical assistance they require is expensive.

The digitalisation and preservation of parish and diocesan archives deserves special attention. The wealth of ecclesiastical documentation cultural heritage is only imaginable in its full dimension to those who are familiar with the role of the Church throughout history. Virtualising these archives would guarantee preservation in the face of the passage of time, which deteriorates ink and paper, and in the face of natural disasters or other incidents. In addition, virtualisation makes it possible to efficiently locate personal records of sacraments, to issue individual certificates and even to send them to another parish, as some tools include digital verification systems, e.g., to send a sacramental act of baptism from a Spanish parish to a parish in Mexico if a parishioner is going to be married there.

In short, specialised software for parishes and dioceses supports the administrative tasks that every human organisation needs to carry out today and enables churches to offer 21st-century services to their communities.

In everyday parish life, not only specialised ecclesiastical software but also general digital tools are used. To illustrate this, we present in Table 1 a real case: the digital diet of one of the informants in the sample, a priest from a parish in a medium-sized village in the community of Madrid, aged around 40, which includes examples of content referred to in the previous and the following sections.

Table 1.

Middle-aged parish priest’s digital diet (Informant 3).

According to the sample discourse, the example shown in Table 1 is not considered illustrative of the parish priest community, as the same informant describes himself as a digital user above the average technological competency of his peers; however, this is not an isolated case and points out a growing reality.

3.3. Community Content and Interconnectivity

In Section 3.1 and Section 3.2, we assessed how the virtual space brought new features to old processes; now, in Section 3.3 and Section 3.4, we will explore more genuinely digital processes, for example, a priest preaching to an unknown audience who in return can interact with him.

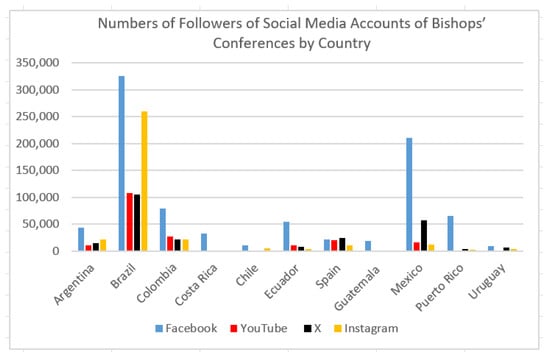

The Church’s presence on social media is common through corporate accounts of ecclesiastical units: the Holy See, episcopal conferences, congregations, religious colleges, dioceses, archbishoprics, missions, parishes, etc., have active profiles with a strong focus on their own local communities. To identify the most common social networks, a comparative analysis of the social media accounts of different episcopal conferences in Latin America was carried out. As Figure 1 shows, Facebook is the most popular in all countries, except in Spain, where it is slightly less popular than X.

Figure 1.

Follower numbers for bishops’ conferences’ social media accounts. Source: own elaboration.

The contents of the social media profiles of all these organisational units have a common denominator: they deal with social or liturgical events celebrated in the community and contain messages from local ecclesiastical personalities. The whole community participates in creating the community story.

It is common for ecclesiastical units to also have a website that brings together their dispersed presence on varied social media platforms (where they present the narrative of what they have done, their spiritual life experienced together); the websites also centralise practical information about what can be done (mass and confession timetables, social activities and liturgical events), about the members (priests, catechesis groups, choir, brotherhoods, etc.), about what is on offer (services and procedures) and about materials, along with the usual “donations” button. In short, the websites combine the management and communication of a specific religious community; they are the digital melting pot of a parish’s public life.

As indicated by one of the informants (Informant 3), a particularity is the so-called popular religiosity, that is to say, traditions and religious festivities, in this case social media contents, are not exclusively centred on the spiritual and also include cultural aspects experienced at a communitarian level, an example of which could be an Instagram reel of a brotherhood showing how they train for Easter processions.

To summarise, virtual technology can be spiritually empowering because digital ubiquity provides a flexible time and space; for example, members of the same community can pray together via videoconference even if each member is in a different place. This is nowadays possible because Internet “exits in our pockets”; unlike the first stage of digitalisation, when the Internet was only accessible on desktop computers, the current anywhere–anytime connection is expanding the spaces and circumstances for religious practice.

3.4. Evangelisation of the Digital Continent

The combination of online tools and practices described in the previous sections are meant to accomplish the so-called evangelisation of the digital continent, which has naturalised terms such as digital missionaries or Internet apostolate. The aforementioned RIIAL, a pioneering church computer network in Latin America that has been active since 1992, indicates that digital technology is not an instrument but a culture, which means that digital space must be considered a mission field.

Pope Francis’ call to be an “out going Church” means that it is no longer enough for the Church to open its doors; the Church must go out from its own walls to listen to the people (Pope Francis 2021). The Synod of synodality is inspired by this call; synodality has changed the communicative method of the church into a participatory method, and with the adoption of digital communication, synodal listening is an opportunity to understand the dynamics of digital communities and to incorporate them into the life and mission of the Church (Sbardelotto 2024).

Informant 6, in addition to following the digital diet that he described (Table 1), manages a Telegram channel and a blog for the dissemination of his own homilies, which the president of the Brotherhood of the Blessed Sacrament (Informant 2, 75 years old) of the same parish describes and values in the following way: “After the Gospel, the parish priest sets up his mobile phone to record the homily, which he then loads up, as this is how many of the believers who are not present at Mass, sometimes there is just four of us, listen the homily”. This response illustrates the problem of the loss of face-to-face practising believers and how the Church tries to reach out those who do not physically visit the Church.

In short, with synodal listening, that is, a community–Church bottom-up dialogue that involves praying together and actively listening to each other’s perspectives and insights, it has become evident that many people do not go to Church, but they are reachable through digital instruments, and the Church has taken up this challenge. Examples of the collective realities of digital evangelisation are JDN (Juan Diego Network), Ilumina Mas and Catholic Link.

At the tip of the iceberg of this phenomenon, we find priests or nuns with popularity on social media for their pedagogical (or even musical) ability to explain the Gospel: “There are examples of priests and bishops who develop a lot of pastoral work through digital media such as X, Spotify or Youtube, but the percentage is not large” (Informant 6). Sometimes, the excess performativity or personalism of these clergy influencers has precipitated the forced end of these digital forays, or even the end of the priestly ministry; this is the case of the known smdani, as Informant 6 reports. Rather that these eye-catching cases, clergy use their personal social media accounts to express their opinion in the public sphere while maintaining their status as a representative of the Church. If an individual social media account of a priest is used to project a more personal profile (e.g., publications about his hobbies), it is usual to restrict access to known contacts, as Informant 4 explains. This raises an interesting question: How do clerics manage their public and private space in the Digital Age?

3.4.1. Specialised Training for Digital Evangelisation

The new style of evangelisation demands specialised training; while out of this study’s scope, we find the long-running Catholic Social Media Summit (CSMS), youthpinoy.com/initiatives, to be worthy of mention, as, in November 2024, it celebrated its 13th edition. It is defined as an annual meeting of Catholic communicators, educators and digital missionaries to share strategies and knowledge for effective online ministry. On the same dates and with the same objectives, the second meeting of Catholic influencers took place, organised by the ACdP (Catholic association of propagandists) shorturl.at/ezyWi. The virtual diploma course “Challenges for an Outgoing Digital Mission”, organised by the Centre for Biblical, Theological and Pastoral Formation of the Latin American and Caribbean Episcopal Council (CELAM) celam.org/cebitepal, was also held on the same dates with similar objectives, namely “training and accompanying all those who feel the vocation to preach in digital environments”. Another example is the iMission Association, imision.org, which offers specialised evangelisation courses for each social media, e.g., “The 5 keys to the success of a Christian Tiktoker”. In these meetings and training programmes, it is common to emphasise that digital presence should not be used to gain personal fame but to connect with others using a common language. Social media is considered the best way for young people to evangelise their peers; in 2020, there was an evangelising initiative for millennials and generation Z, catolicovirtual.com.

3.4.2. Other Digital Means

A remarkable group of tools comprises religious applications, the most significant being apps for praying. Hallow is internationally popular, and other well-known apps include Rezando Voy, Diez minutos con Jesús and Tabella. There are even officially endorsed apps, such as the applications of the Spanish Episcopal Conference for liturgical books or the liturgy of the hour. There are also accompanying apps that offer spiritual, professional or human support. Another group of applications comprises apps for sacred texts; these include versions of the Bible for different audiences or even those that use artificial intelligence to offer interpretations of readings. The common feature of spiritual applications is that they provide personal utility, which, as will be seen in the discussion section (Section 5), has positive and negative sides.

Finally, a series of digital resources targeted towards Catholic clients is mentioned; the depth of their spiritual meaning is unknown, but it is clear that there is a market niche at the crossroads of religion and digitalisation. Examples include digital religious marketing services, i.e., catolicos.red; digital graves connected to real graves with QR codes to preserve memories, i.e., micementeriodigital.com; and interactive games for catechesis, i.e., discipletoys.es.

To complete this section, the latest upcoming digital technologies adopted within the Catholic world are mentioned, such as the use of AI for the retrieval of Gregorian chants and the creation of a digital twin of the Vatican; these examples show that the digitalisation of religion is a growing process. A summary of Section 3 is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of Section 3: digital tools and practices for ecclesiastical digitalisation.

4. The Impact of Digitalisation on the Church: Analysis of Interviews Guided by the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) Tool

In Section 3, we describe the Catholic Church’s response to the digital transformation, but this does not allow us to analyse what is missing or to know the consequences of this process, which is why the methodology collected the opinions of experts. A SWOT analysis was applied to these interviews, which was considered appropriate because it differentiates between variables with a positive and negative impact, as well as those with external (threats and opportunities) and internal (strengths and weaknesses) origins.

4.1. Weaknesses

4.1.1. Fear of Change and Substitution

The discourses in the sample point to barriers in the process of digitalisation in the Church, including a fear of change, which is expressed, for example, in the form of resistance to changing the traditional way of doing things (Informants 5 and 6). This is considered a weakness because, in some online procedures, there are possible conflicts between Canon law and the current organic law on data protection. For example, if a baptismal certificate is digitised, it becomes a file and must therefore be subject to the current law: “You can be denounced if you have digitised the files and have not registered them. It is not forbidden to do it [digitise sacramental acts], but then you have to register them with the data protection agency” (Informant 7). For this reason, some parish management software companies advertise that they comply with GDPRs (general data protection regulations) and that they are certified within the EU Data Privacy Framework. This has led to incorrect beliefs among the clergy, such as that sacramental books cannot be digitised. The sample demonstrates that this kind of misinformation is no longer widespread, except in the case of Informant 1 (the CEO of an ecclesiastical software company), who attaches much more weight to this barrier than the other informants, probably because it makes it difficult for his business as a Church technology supplier. Most of the sample also agreed that the virtualisation of archives should never replace physical copies; this denotes a point of psychological resistance or nostalgia, especially when compared to other emblematic changes from previous paper formats (e.g., newspapers and photography), where today there is no coexistence but instead total substitution. It seems that there is an attempt to balance adaptation and the preservation of one’s own identity: “How far is tradition and how far is obsolescence?” (Informant 3).

The idea of replacement connects with another fear: that the digital will replace personal action. In the lay world, this fear is widespread in the labour market (“robots are going to take my job”), but it is not present in the ecclesiastical sphere, where to be dissmised is not a real fear. Only one subject (Informant 5) reports this fear, but he was referring precisely to the lay staff’s fear of being dismissed when accounting software was installed in the parish. A priest cannot fear that a robot will replace him in giving the homily, but a journalist can fear that AI will write the news for him (Fieiras-Ceide et al. 2024); however, it cannot be ruled out that some young seminarians have sought support from generative AI to prepare their homiletics classes, for instance. What is important here is to differentiate the level of identity representation of what is substituted (whether subjects or objects) and the nature of the tasks: it is not the same if the account books are substituted as if the sacred books are substituted, and it is even more controversial to substitute physical presence for virtual presence in pastoral and/or accompaniment tasks, given the crucial nature of digital mediatisation in these cases. This will be discussed in more depth later.

In none of the interviews, not even in Informant 1’s (the businessman), was an economic variable mentioned; thus, it seems that money is not a barrier or weak point to digital implementation for the Church.

4.1.2. Age or Rhythm?

When the technological adaptation of users is addressed, the age variable arises almost automatically, and this is not unwise, unless it is considered the only influencing factor. As Prensky (2009) rightly pointed out when he coined the term “digital natives”, people born into a digital environment have an easier time adapting to it; however, in order not to fall into the prejudice of ageism and to globally understand the degree of technophilia or technophobia of each individual, we must also consider aptitude and, above all, one’s personal attitude towards technology, in addition to belonging to a certain generation.

The Catholic Church in Spain comprises a population with a high average age—65.5 years old (Europa Press 2018)—also, its leadership is notoriously older than its base, with an average age of 77 years old (Pérez Dasilva and Santos Díez 2014). According to these facts and following simplistic reasoning, the Church should reject the digital world, but the reality is not so because, as some informants point out (namely Informants 3 and 7), the variety of mentalities existing within the Church is explained by more than age.

Even so, in the interviews of the sample, age is repeatedly pointed out as a negative conditioning factor.

More than the age itself, it is probably a question of rhythm, as most of the informants also express the idea that openness to digitalisation has improved over time within the Church, but that more time is still needed, as demonstrated in the following response:

“There are parish priests who are 24 years old, but not bishops who are 24 years old, they are around 50 years old, which is logical because of their experience. So of course, it is a factor that is going to require more time to get into that mentality”.(Informant 3)

The reality is that the transition from an industrial society to an information society has taken place over just a few years, which means that the same person can live fully in two paradigms over the course of their life; therefore, this is a change that entails a high demand for adaptation, which can be detrimental to institutions with an ageing population. In short, just because the average age of the Church is high does not mean that technology has less of a place than in other institutions, but it does add barriers.

4.1.3. Skills (Training) and Attitude: Decentralised Implementation

Specialised digital training was discussed in Section 3.4.1, but those examples are aimed at both religious and lay people and are meant for the digital apostolate. A different issue is the learning of digital skills and culture by the Church’s “staff” (bishops, priests, nuns, monks, seminarists), which the sample’s opinions indicate is an unfinished task at the organisational level:

“The longer we take to get it into our heads that the new generations of priests need to have digital competence (…) the more forgotten we will be”.(Informant 4)

According to the sample, the level of digital skills among the priesthood varies from subject to subject:

“Among the clergy there is a bit of everything. I think that in general terms they are quite used to use common means of communication. Any priest can manage well with whatsapp or similars or email. Beyond that, there is not so much. I find, for example, few companions who use digital diaries or share calendars with collaborators in order to coordinate better. What is very common is to have the accounts and the archives digitalised”.(Informant 6)

Another member of the sample confirms and explains that parishes and dioceses are digitalised at the management level because “You have to do the accounts, donations and all that you have to present them digitally to the Finance and Taxes Ministry, there is no other way” (Informant 7).

The heterogeneity described above about the level of use as well as of technological training is explained by some informants as follows:

“The church is not the army, in the church there is a lot of freedom (…) in the civilian world it is understood in this way, that the parish is the delegation of the diocese and then the headquarters of the multinational are in Rome, that is not so (…) There are different positions among the bishops, each one decides”.(Informant 7)

Also:

“There is no diocesan project to implement certain tools in all parishes. In these parishes, it depends a lot on each parish priest and not so much on the institutional force”.(Informant 6)

These opinions are categorically confirmed by Informant 1, who deals with dioceses at a national level as an ecclesiastical software supplier for the Church. He explains that the work in Spain is conducted in individual parishes, which contrasts with other countries, where his company provides services jointly to the churches of the same bishopric, as is the case in more than 20 Latin American countries. The same informant also points out, as an institutional weakness for digitalisation, that the Church is reluctant to engage in external professionalisation. One of the participants explains the different way things work in Spain and Latin America as follows:

“Because of our culture here in Spain (…) which has its advantages and disadvantages. The parish priest is at the head of the parish and who shapes the parish together with his community (…) in Latin America they have another mentality, a more overall mentality and when they speak, they speak more on a national level, the one who comes from Nicaragua says ‘the Nicaraguan Church is like this’ and in Spain nobody would say, ‘The Church in Spain is like this’”.(Informant 3)

The irregular digital implementation, besides the organisational transfer of power among institutional units, is also associated with different positioning among hierarchical positions, which stands as an internal weakness:

“What is clear to me is that sometimes there are guidelines that favour digitalization and sometimes there are guidelines that hinder it. I think I have expressed myself very clearly. There are reactionary bishops (…)”.(Informant 4)

At the end, it seems that digital skill training is a rather personal concern: “You have to deal with this new reality and that also means dedication, time and training”. (Informant 4).

But not all digitalisation is decentralisation, there are also some digitalisation initiatives at the organic level:

“Now in Madrid they have done something called “Proyecto comunica” (…) a kind of network of their own, their own software to have communication between dioceses. We’ll see what happens”.(Informant 7)

In short, except for the digitised archives and accounts, digital implementation as a whole (communication plans, pastoral activity, evangelisation, etc.) is perceived as a heterogeneous process. In Spain, it varies from parish to parish, from diocese to diocese, from convent to convent and from archbishopric to archbishopric, and the sample explanations mainly correlate it with the Church’s decentralised functioning. The Church does have a position on what the digital paradigm means for present society (see Section 1.1), but no institutional plan for digital technology implementation and training in the Church was detected during this research. According to the sample opinions, it is more an individual process, where each priest or bishop decides to what extent technology is used in his own department.

4.2. Threats

Does digitalisation harm spiritual life? The Spanish Episcopal Conference speaks of spiritual impoverishment (Section 1.1) as a result of the characteristics of the current paradigm: detachment, fragmentation and transience. The digital network is a sum of individualities without a true sense of community (CEE 2021). Both the Conference (CEE 2021) and the Pope (Pope Francis 2015) affirm that the current digital paradigm affects lifestyle, and both connect technological developments with the concentration of power and economic rationality, both of which are elements far removed from spiritual life. In his encyclical Laudatio Si’ (Pope Francis 2015), the Pope expressed the following: “the dynamics of the media of the digital world which, when they become omnipresent, are not conducive to the development of a capacity to live wisely, to think deeply, to love generously” (Pope Francis 2015, p. 36). More recently, the Pope also pointed to the threat posed by manipulative uses of AI in opinions, voting and consumption (Pope Francis 2025).

Despite all these technological threats to the growth of the faith, the Church institutionally does not indicate that renouncing the digital world is the solution but rather proposes a proactive reaction: cultural revolution (Section 1.1), which actually means to impregnate the digital space with a kind, humanitarian, community-based perspective. We see a practical application of this in the specialised trainings and courses for digital evangelisation (Section 3.4.1), where the traps of the online world, such as addiction, frustration and short-lived success, are pointed out, and trainees are warned to avoid them using Christian values.

The sample reports on social networks and spiritual impoverishment as follows:

“For me, three of the greatest dangers would be dispersion, superficiality and lack of authenticity (…) because you are constantly receiving inputs from outside that make it difficult to pay attention (…) because it builds a kind of parallel world based on the image you project outwards”.(Informant 6)

The sample also perceives the threat of omnipresence, in the sense that the digital revolution is more and more present and seems to be unstoppable. In the face of this pressure, most of the informants share the opinion of embracing adaptation in order to not lag behind, as follows:

“The church must gradually take steps to modernise, I don’t know if that’s the right word, I like the word update better. The church has to be in today’s world”.(Informant 4)

“With any drastic change there are obviously many people who are left behind, but I don’t think that the church is being left out (…) it is true that I think that they are not taking enough advantage (…)”.(Informant 3)

Also, on a personal level, change is seen as mandatory, as shown below:

“This strains you, pushes you, you to have to catch up because if you don’t, you miss out”.(Informant 4)

This is because digital transformation is taking hold and producing a domino effect, as one informant expresses:

“In the same way that I go to the Town Hall (…) everything nowadays is already computerised (…) we must make communications in the church more fluid”.(Informant 3)

Toxicity and polarisation also arise here; one of the informants explained cases in which if a religious person expresses more progressive opinions than those of the traditional position of the Church, he suffers the aggression of other more conservative Catholic factions: “In the networks, the ultra-traditionalist groups have much more presence” (Informant 7). This extremist over-representation is detrimental to the overall image of the Church.

4.3. Strengths

In the face of the dangers outlined in the previous Section, the sample takes a firm stance, as expressed below:

“We should be able to overcome certain criticisms and the fear of failing in the digitalization of the church (…) digitalization obviously carries a risk, but we cannot put our heads under our wings as if we were ostriches”.(Informant 4)

The Catholic Church is made up of free people who simply decide how/when to use the tools available, as follows:

“For example, I prefer to pray with a book rather than in a mobile phone because it distracts me less, but, if I go on a trip, I don’t take the books with me [pointing to the four volumes of the liturgy of the hours]. I don’t have a problem praying on the screen either”.(Informant 7)

Institutional freedom has favoured the natural implementation of personal devices in the ecclesiastical community. The use of smartphones and digital devices among the clergy is fully extended (to even monks): “You go to the meetings of the priests, and nobody takes out the book to pray, the one who takes it out is the geek” (Informant 7).

The awareness of making good use of technology, as expressed among the sample, can also be considered as a strength. All the interviews coincide in separating the tool and the use that is made of it. For this discernment to be clear, it is necessary to have a defined framework for action; the Church’s greatest strength in the face of the maelstrom of the virtual world and its ephemeral narrative is that Church’s message and mission are clearly defined beforehand. This is why Pope Francis proposes a cultural revolution as an antidote to the digital threat (Section 1.1). This refers to a kind of Internet re-appropriation from a Christian viewpoint, an idea that is also exposed in the following responses:

“Digitalization is a means; it is not the end (…). What will have to be done is to try to ensure that the use of technology is respectful of others (…) what has always been done [by the Church] is to evangelise culture (…) Why shouldn’t the Internet be evangelised? (…) We also need to give meaning to technology”.(Informant 7)

“Everything has to serve the purpose, goals and values that are part of your culture, in this case, the culture of the Church. Digital tools can play a very important role (…) We need material means that express, signify and nourish what we carry inside. In that sense, new media are indispensable in today’s culture”.(Informant 6)

Informants 2 and 5 talk about the experiences of several religious congregations in formal education. We consider them key strengths to mitigate the threats of the technocratic model because their presence in educational contexts allows them to detect emerging risks and propose solutions, such as the Salesian congregation text on the use of AI in education, which warns that “AI could lead to a loss of emotional connection in education (…) the focus of AI on efficiency and performance could overshadow the importance of moral and spiritual education” (Rosario et al. 2024), in response to which the authors propose the creation of a new figure, that of the philosopher–computer–educator.

4.4. Opportunities

Sometimes opportunities arise from difficulties or, better said, from how they are overcome. For example, all those interviewed indicate that the pandemic was a catalyst for new usages of technology and ICT learning:

“A clear example was COVID, we had to take steps that we should have taken 10 years ago, technology gave us the opportunity to accompany the communities, I remember older ladies who said: ‘We have opened a Facebook page to be able to listen to mass, put something on it for us, we are used to attend daily mass (…). We are desperate’”.(Informant 3)

Moreover, the pandemic was a turning point that normalised certain online behaviours, as the following informants express:

“If I sent any Christmas greetings or special news through the WhatsApp broadcast channel (…) the impression I had was that older people saw it as a bit out of place (…). When COVID happened, the presence of the church in all communications, Facebook, social media, became absolutely normalised”.(Informant 3)

“And COVID meant a change of mentality, many people in the parishes realised that tools such as Teams or Meet or all these digital tools had to be present in the daily life of the parish”.(Informant 1)

In the face of natural disasters, virtual space can also be an opportunity. This was illustrated after the floods suffered in the region of Valencia (Spain) on 29 October 2024, an area where the informant who is a provider of digital services to the Church happens to be from, and that is why he was able to offer such a relevant testimony:

“One of the most affected municipalities by the floods is the municipality of Picanya, this parish is at the gateway to the river (…) we were in the parish helping with humanitarian work (…). I accompanied him [the parish priest] to a room where he had all the parish books, all the history of the municipality, all the history of all the baptisms, marriages, confirmations, all the sacramental books, all the books were swimming in water and mud (…) he [the parish priest] said to me: ‘we are going to lose all this information (…) we have the computers also broken down, but as (…) they are upload on your servers, we have the peace of mind that we can take back the information (…) and I wanted to thank you’”.(Informant 1)

Another informant also reported on the benefits of the virtualisation of the archives against accidents:

“We don’t have to wait for floods. You can have an accidental fire and lose the archive (…) I was renovating (…) one of the boxes containing parish books got wet and I had to restore three parish books because otherwise I would have lost those baptismal and death records”.(Informant 4)

Therefore, the virtualisation of sacramental acts is a relevant opportunity to protect the history of the Church and its communities from deterioration due to catastrophes or the mere passage of time.

All the described utilities of parish management software (Section 3.2) are another outstanding opportunity, which can be summarised as efficiency in administrative and organisational tasks:

“A baptism in my parishes is requested through WhatsApp (…) the person already sends all the data in a form and (…) ask for an appointment and when the person comes to the office they come only once with all the documentation (…) the only thing left is to schedule a day and time for the baptism. (…) I have gone from having the parish office open 5 days a week for two and a half hours each day, to having it open only one day per week and previous appointment request”.(Informant 3)

The ubiquity of the virtual space provides pragmatism: “You have the parish in your pocket” (Informant 3), or “you go to a meeting and you don’t have to carry [liturgical] books” (Informant 7).

Digital opportunities for communication purposes are very relevant; for instance, online communication breaks down physical boundaries for evangelisation:

“Having the ability to send a message to almost literally the whole world is also very powerful”.(Informant 6)

Additionally, not only unidirectional but also bidirectional communication allows for interactions with and care for the community:

“The moment you make yourself present, apart from the fact that you are found, you also find (…) to be present to reach the people of the 21st century (…) we need contact (…) to be in the middle of what is of public interest and that a priest cannot miss from his parish, his village or his neighbourhood”.(Informant 4)

4.5. Neither Threats nor Opportunities: Open Debates

The previous analysis has shown how some issues can pivot between being threats and being strengths, depending on how they are addressed; the truth is that digitalisation advances inexorably and is constantly testing all of us.

One of the dimensions that the new paradigm has most transformed is the notion of space. Among the first unknowns emerged when we started to access virtual space a few years ago, included defining what was acceptable to do there. Initially, digital space had a second-class connotation; for example, meeting a partner online was suspicious, and it was considered a plan B for those who were not able to do it in person. Less than a dozen years later, we can find that a priest expresses the following:

“I’ve already married at least a dozen people who met online, two people who meet online and have deep conversations for two years, maybe they know each other better than two people who met in a bar and went out five times and fall in love”.(Informant 5)

In other words, the perception of virtual space has evolved. The Section 3.4, Evangelisation of the Digital Continent shows that an important part of the Church, including Pope Francis, who encourages Christian communities to use all the tools that technology makes available to announce the Gospel (Bonilla 2019), values the presence of the Church in the virtual space positively, as described below:

“It is necessary to use the new media, that is to say, all the means that exist for the community, for communication, to reduce distances”.(Informant 5)

The basic argument for this is adaptation to the context, as the following responses reflect:

“The message of the Gospel, we can say, has been incarnated in each culture. The culture of 2000 years ago has little to do with today’s culture, so while maintaining the essential, the form is secondary, why not go into the digital world”.(Informant 7)

“You reach a lot more people, so I see a current situation in which you have to get involved, otherwise you are disconnected from the world (…) if you are not there, other people will be there”.(Informant 4)

So, the question for the Church is not whether to be or not to be on the Internet. The question is how to be in the virtual space; regarding this, there is no unanimous position:

“There are differences of criteria in terms of evangelisation via Internet, that is to say, if the technology only has to be for us to have our web page, web communication model, or if we have to be fully active in the social media. This is not clear, and I think that the majority position is rather no”.(Informant 7)

The same informant explained that one’s view on digitalisation has nothing to do with having a traditional or a progressive mentality, i.e., a conservative-minded bishop may be very active in social media.

This discussion links to the issue of technological mediatisation. The first consideration is how the presence of technological devices in sacred places has become normalised. Informant 2 described how he used to consider it “profane”, but, with the passage of time, he became accustomed to it until it became irrelevant. Another informant stated, “It is true that before you saw someone in the pew with a mobile phone and you said: ‘what is he doing?’” (Informant 5). Now, it is the temples themselves that invite interactive participation, for example, by means of digital offering baskets, QR codes attached to the pews to follow the lyrics of the chants or by using the necessary equipment to stream liturgical acts. This change is the result of evolution, as the following informant explains:

“For example, with the issue of liturgical books (…) the missal, there have been problems. Now we have an official app from the bishops’ conference, but before it was like «no, no, you have to use the book». And you think, well, does the book have to be used? This is like when the printing press appeared, probably they said: «no, it cannot be printed books, at Mass you have to use handwritten books», nobody would think about forbidden printed liturgical books now. What is the difference reading from a book or form a screen?”.(Informant 7)

This brings us to the mediatisation, both for the sending of messages and for the celebration of sacraments, which is an even more complex issue. The same disruption must have been experienced in 1949, when Pius XII addressed an Easter greeting to the audience, constituting the first TV broadcasted message from a Pope (Bonilla 2019), and in 2020, when confessions via digital means were conducted due to the pandemic and lockdowns. Technological mediatisation issues were raised in the interviews, as follows:

“What happens when the Pope gives masses so large that some of the parishioners only see him on the screen? What about the Urbi et Orbi blessing the Pope gives on Christmas Day in which he literally says that all those in the square and all those who follow him through the media receive a plenary indulgence?”.(Informant 7)

“If I have been accompanying a person for 10 years and he has a problem and he is in the United States. He calls you and says he’s in a bad way and you listen to him, but what do you tell him, that he has to go down to the parish downstairs and get absolution from the priest there?”.(Informant 5)

What is the limit of technological mediatisation in the celebration of faith? The type of device? Who delivers it? The type of liturgical act? Why is confession via iPad valid for a person with a hearing impairment but not valid for those who are far away? The above responses show that reality is taking over the question about the validity of mediatised sacraments, but it still needs time to be generally accepted. Even so, there are elements of consensus on these issues, for example, that the relationships at some point, pre- or post-Internet, should be consistent on a physical level, and that the virtual ones should not fully replace the personal ones, as explained below:

“Digitalization is a medium that supports, but does not replace face-to-face, at least not on a regular basis. And we should reflect on that. Meeting online, for example, is practical and useful, but direct contact generates much friendlier and more appropriate relationships in the teams”.(Informant 6)

To conclude this section, a summary of the SWOT analysis is presented in Table 3:

Table 3.

Summary of SWOT analysis of interviews on digitalisation in the Church.

5. Main Results and Discussion

The technological religious practices presented in Section 3 and expert opinions on digital impact analysed in Section 4 indicate that religion has become spontaneously digitalised; at this point of the 21st century, digitalisation is simply happening in people’s lives, and practising Catholics check the mass timetable on the Internet just as they check the bus timetable. It is also accepted to listen to a recorded homily if parishioners have not been able to attend church, just as it is accepted for a student to watch to an online recorded class. The omnipresence of media and technology as an imperative for religions to assume new forms of being in our present society has been previously reported (Sbardelotto 2016; Arboleda Mota 2017; Stępniak 2023). Conversely, spirituality enters areas previously distant from transcendental values, creating new post-materialist discourses (Gil-Soldevilla et al. 2019).

However, although it is a similar process to those in other areas in society, digital mediatisation in the Church has its own peculiarities. As the Church’s base in Spain has a high average age (of both clergy and parishioners) and deep-rooted traditions, the pace of implementation has possibly been slower than in other sectors under the market pressure. This time-consuming rhythm for change was reported by some members of the sample (Section 4), and a similar idea was pointed out by Pérez-Latre: “religions are still learning how to be content producers, and they are a little behind than other organisations” (Pérez-Latre 2012, p. 181). The analysis of followers of different Latin American episcopal conferences accounts (Section 3) showed that all of them have had active profiles on the main social media platforms for the last dozen years. The most popular social network by far is Facebook; activity on Instagram is low, and their presence on TikTok is almost non-existent. These data represent the institutional virtual presence of the Church: active and stable but not at the forefront of trends. Fandos Igado et al. (2020) also found that Facebook is the preferred social media platform for both ecclesiastical institutions and for the Spanish clergy’s individual profiles, and they noted that clergy accounts are not characterised by effective communicative use. Similarly, Pérez Dasilva and Santos Díez (2014) reported that cardinals tend to use Twitter in a “top down” way rather than in an interactive communicative model. Thus, our research and that of other authors shows that the Church is going digital, but at its own speed and without leading trends.

Regarding economic variables, no informant pointed them out as a barrier to digital implementation, despite the fact that the technological instruments and technical maintenance entail high costs. Other research studies also found no economic barrier and indicated that the clergy possess sufficient digital means (Fandos Igado et al. 2020).

The set of interviews conducted shows how contextual difficulties place value on the presence of the Church in the digital world, for example, during the pandemic, to allow for religious accompaniment at a distance. Other authors also highlighted values for the user when pandemic restrictions forced religious organisations to move most activities online (Hall and Kołodziejska 2021).

In addition, in the face of natural disasters, in order to preserve the valuable documentary archive of the Church, the cloud provides many benefits. The responses obtained from the creator of the ecclesiastical software was very revealing; as an informant of this research and neighbour living near one of the parishes most affected by the floods of 29 October 2024, namely Picanya (Valencia, Spain), he explains as an eyewitness to the catastrophe:

“(…) the [sacramental] books were swimming in water and mud (…) but since (…) they are on your [company] servers, (…) we can recover the information”.(Informant 1)

The Church has a position on what digitalisation means for present society (see Section 1.1), but no institutional plan for digital technology implementation and training in the Church has been detected. This is related to the functional decentralisation of the Church, which several informants of the sample mentioned; it is each religious person who decides to what extent technology may enter their organic unit (parish, diocese, etc.). Generally speaking, administrative tasks (accounting, archives) are digitised, but organisational tasks (events and activities) and communicative tasks show different levels of digitalisation. Personal devices among religious people are fully standardised for personal use and partly also for spiritual use, e.g., apps for prayer.

Nevertheless, regarding the technological heterogeneity at the functioning level within different ecclesiastical units, it seems that the Church is aware of the need for a new evangelisation and of the possibilities of the Internet as a mission field, given the increasing desecularisation and postsecularisation processes in our societies, as well as the presence of many other religions, new forms of spirituality and new belief systems in the spiritual space (Pérez Dasilva and Santos Díez 2014; Díez Bosch et al. 2017; Stępniak 2023). The evangelisation of the digital continent is a mission defined by the Church, as indicated by our sample and other authors (Tridente and Mastroianni 2016; Fandos Igado et al. 2020). A strong Catholic presence on the Internet is detected through the following means: news agencies, multimedia platforms, portals, organic social media accounts, community websites and individual profiles. All of these are driven by Catholic groups that offer content from a Christian perspective (news, events, prayer texts, lives of saints, papal activity, etc.) to accompany and train those already practising but also to approach non-believers or those who have spiritual doubts:

“When you have a concern and you want to look for God, what do you do, do you look for a priest? No, you look on the internet, in the 21st century you look on the internet”.(Informant 4)

The most striking section of the virtual apostolate is religious influencers. These missionary Instagrammers are only the tip of the iceberg; they do not represent the entirety of ecclesiastical digital actions, but they show that the Church, based on what we have been able to monitor so far, has a presence in all digital expressions. It is expected that these digital expressions, now anecdotal, will grow and become normalised.

There are also digital options for practising spirituality and celebrating sacraments, for example, apps for prayer or streaming masses; however, these are not abundant, as the sample reports, because digital mediatisation of the celebration (rites, practices) of faith generates a greater division of opinion than its use for announcement, support or faith training. However, the presence of digital devices is increasing in sacred spaces: digital offering baskets, QR codes in the pews to follow chants and liturgical books on screen comprise some examples. Digital mediatisation in the celebration of faith is more accepted in so-called popular religiosity; for example, confraternities’ social media accounts report not only from a spiritual point of view but about a whole cultural experience.

The debate on the limits of mediatisation, i.e., to what extent the screen does not detract a liturgical act from its validity, is open; still, informants reported some consensus such as the fact that a relationship between clergy and parishioner (accompaniment) cannot exclusively exist online. The reflection on corporeality (Arboleda Mota 2017) and online and offline complementarity is highlighted by several authors (Díez Bosch et al. 2017; Evolvi 2022; Korpics et al. 2023).

In any case, whether they are more or less accepted, digital tools broaden the possibilities of practising religion and experiencing spirituality (Stępniak 2023), whether it is a geographically dispersed brotherhood praying “together” via videoconference or a person who is not near to his Church and needs its protection, listening to the homilies of his own parish priest that he himself posts on the web. Some authors point out that it is precisely in the rupture of the spatial–temporal scale that technologisation has most influenced digital religion; this is what Sbardelotto calls news temporalities and new spatialities within the religious phenomenon (Sbardelotto 2016).

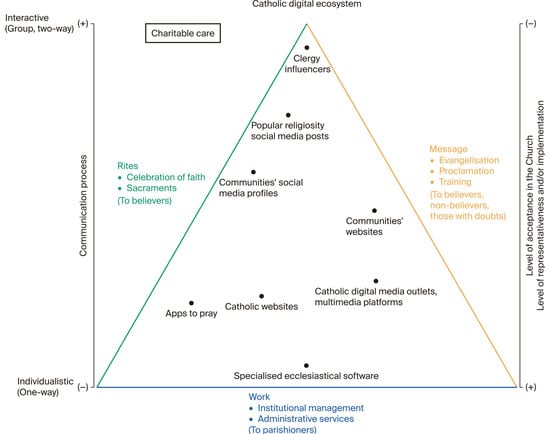

Our analysis of practices did not reveal, nor did the sample report on, cases of technologisation at the care level, i.e., accompaniment in situations of vulnerability or charitable work, which leads to the conclusion that the area of charitable care is an analogic redoubt. It is worth asking whether this is only due to the importance of physical presence in these types of matters or whether the cyber-rich/cyber-poor categorisation of Berzosa Martínez (2016) plays a role here.

There seems to be a larger Church presence in the virtual space than a digital presence in ecclesiastical spaces, with an even smaller digital presence in sacramental rites, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Types of ecclesiastical duties and level of digitalisation acceptance.

Some inherent characteristics of the technocratic paradigm can lead to spiritual impoverishment, as stated by the Church (Pope Francis 2015; CEE 2021); the Internet, in its fragmentation, disengagement and transience, can bring individuals together but does not create true human communities. Reflecting on communitarian vs. individual practice, Díez Bosch et al. (2017) noted that apps could help and increase personal religious practice, but on the negative side, apps do not allow users to establish relationships. According to our sample’s interviews, the Christian presence on the Internet does not avoid the endemic polarisation and toxicity of digital conversation either; e.g., there is an over-representation of ultra-Catholic factions on the web that internally attack those who promote more tolerant positions within the Church.

6. Conclusions

The social imaginary does not establish a strong connection between digitalisation and the Church, but the Church is indeed a digitally active entity. The Church is close to the digital society, but our society is not close to the Church, which is why society is unaware of the Church’s presence on the Internet.

Although the Catholic Church in Spain is integrated into the new paradigm, it is not at the forefront of the trends, nor has it been fully transformed, as has already happened within the media sector for instance, but does the Church need this? It has been revealing to research the digital side of the Church through the Internet itself and to contrast this with the opinions of Church representatives who are not so active on the Internet. To rebalance the “online effervescence”, it has also been interesting to analyse the Church’s position on the impact of the digital revolution on spiritual quality by reading the papal encyclicals (Section 1.1 ‘The Church’s Position on Technological Change’), rather than only reading the scientific literature analysing digitised religious practices.

An ecclesiastical structural plan for digitalisation has not been found, but digitalisation is allowed to enter the Church. There are internal debates about virtual mediatisation, and there is broad agreement on digital uses for the proclamation of the faith (evangelisation, pastoral care) or in the support and training of believers, but there is less agreement on the use of the technology for the celebration of the sacraments or rites, although current anywhere–anytime connection is expanding the spaces and circumstances for religious practice assisted by digital means. There is full agreement on the use of technological tools that improve administrative efficiency (specialised ecclesiastical software for accounting, management and archive preservation).

The logic of the technocratic paradigm weakens spirituality (disengagement is a real threat), but religion needs digital tools to remain relevant; after all, information networks have made and unmade our world from prehistory (Harari 2024), and the Church also needs them in order to occupy digital space from a Christian viewpoint and evangelise the present culture. Today, a person can “find God” not on the Internet but through the Internet, and a practising Catholic can be spiritually nourished by following a homily both physically in the church and while travelling by bus via Spotify; therefore, ubiquity is the greatest opportunity that digitalisation brings to the growth of faith. The Internet brings religion closer because it breaks down physical barriers, and this is more powerful than the possible detriment of the mediatisation of a screen in the administration of a sacrament. In a case of anguish at a distance, what has more spiritual significance, a parish priest listening through a device and supporting his parishioner, or absolution, which theoretically cannot be given because it is mediated?

In short, the Church’s warning about spiritual impoverishment in the Digital Age, which has been also confirmed by some informants of the sample, partially supports Hypothesis 1 about the Church being digitally affected but not fully transformed. Digital evangelisation and the vast catalogue of ecclesiastical digital tools and practises reported in Section 3 support Hypothesis 2 about digital means being helpful to support existing communities and to reach non-believers. The informants responses about diverse ICT use cases and their divided opinions on mediatised sacrament celebration partially support Hypothesis 3 about personal mentalities affecting different levels of digital implementation.