Abstract

This article investigates the phenomenon of missionary landscape photography with an eye to contributing to the field of environmental history. It uses photos made by Dutch missionaries in newly independent Nigeria between about 1960 and 1968. The missionaries were focused on economic development, agricultural innovation, medical aid, and strengthening local churches. Most photos reflect these preoccupations. Even so, many of the photos also portray trees, animals, agricultural fields, and especially landscapes. We argue that missionaries, through their landscape photography, were instrumental in developing a Western gaze of tropical nature, even if their photography cannot be defined as environmental. By comparing the photos to journals of the missionaries, we can distinguish distinct visual and textual narratives that are obviously connected but also have different accents. Whereas both portray tropical wilderness as exotic or as a challenge for missionary efforts, the photos are less optimistic about opportunities for mission by emphasizing desolate, uncultivated landscape. Overall, we argue that missionary photography offers a rich resource for the study of environmental history.

1. Introduction

This article studies photos made by Dutch missionaries in Nigeria in the 1960s to investigate their “environmental” gaze. Photographs by missionaries, made for an audience in the country of origin, are usually referred to as “missionary photography.” However, this term usually refers to photographs that portray the core business of mission, such as evangelization, education, developmental, and medical aid. Missionary photo collections thus usually feature photos of villages, classrooms, and hospitals to underscore the successes and challenges of missionaries.

This human-centered focus explains why the many missionary photos of the natural environment have been overlooked. In this article, we argue that missionary photography also reveals an “environmental gaze.” Missionaries photographed forests, deserts, gardens, animals, dried-up rivers, agricultural fields, and landscapes. How do these photos reflect their attitude toward the natural environment in which they found themselves? Was it simply a backdrop to their educational and medical work, an exotic background scenery, or did they engage more intensely with the landscapes they encountered?

The interest of missionaries in the natural environment has a rich history that begs to be written (Robert 2011). This article aims to contribute to this. Missionaries were primarily concerned with people, and research has logically focused almost exclusively on the political, social, cultural, and economic dimensions of mission: its contentious connection with imperialism, gender, and racism, as well as its impact on economic development, medical aid, and education (For instance, Stanley 1990; Hall 2002; Etherington 2008; Woodberry 2012; Maxwell and Harries 2012). Even so, missionaries were also engaged in botany and agriculture; they studied fauna, flora, and climates of the places they encountered; held opinions about the agriculture and subsistence they witnessed; and recorded these in travel journals. There is no systematic research on how missionaries were concerned with ecology, although a number of case studies on missionary environmentalism attest to the viability of this line of inquiry (Grove 1989; Endfield and Nash 2002; Mulwafu 2004; Stanley 2015). There are also a number of studies on missionary photography, but these do not so much engage with the natural environment (Jenkins 2001; Maxwell 2011; Waldroup 2017; Thompson 2012). As a result, there is no systematic study on environmental missionary photography.

Such a study would not only uncover the story of missionary environmentalism but have broader repercussions. The current climate crisis has refocused attention on attitudes in Western countries toward the natural environment since the nineteenth century. Many photographic collections, such as landscape surveys ordered by colonial authorities or large corporations, are reinterpreted in light of the economic and other exploitation that followed.1 Many clues regarding attitudes toward the natural environment can be found in photographic collections that do not have nature and landscape as their central subject and that were commissioned by non-state and non-corporate actors. The photographic collections of missionaries are one example. They provide insight into contemporary attitudes of Europeans toward the natural environment in the colonial era and in the first years of independence of postcolonial states.

In this article, a collection of photos made by representatives of the Dutch Missionary Council in Nigeria will form the basis for a case study. Around 1960, the Council decided to explore possibilities for a mission in Western Africa, following the exodus of missionaries from the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) after they gained independence. The Council’s secretaries, Count Steven van Randwijck and Dr. Frederik van der Horst, were dispatched to Western Africa in the winter of 1960/1961 to investigate. Their report provides a unique insight into the purpose of their journey and helps to identify the contours of their environmental gaze.2 This forms the basis for the core of this article, an analysis of a selection of photos made by van Randwijck and other missionaries between 1960 (marking the independence of Nigeria) and 1967 (marking the beginning of the civil war in Nigeria, which disrupted missionary activity). What were the narratives of these photos, the stories they wittingly or unwittingly conveyed? Analysing these photos allows us to understand the environmental narratives they conveyed and enables us to reconstruct the environmental gaze of Dutch missionaries in Nigeria in the 1960s.

Point of departure for the analysis is six ecological themes in missionary history identified by Dana Robert. Firstly, the urge to civilize the wilderness was infused by the Genesis command as well as the belief that “heathen” nature religion was opposed to civilized Christianity. Secondly, missionaries scientifically observed nature and were engaged, for instance, in the study of botany. Thirdly, by the nineteenth century, some missionaries became engaged in protecting forests and combatting soil erosion. Fourthly, missionaries were dependent on the land for food and were instrumental in cultivating agricultural grounds. Fifthly, missionaries played an ambivalent role in indigenous claims for land. Sixthly, after decolonization, some missionaries became involved in “earth protection” programs. With the exception of the last theme, none can be described explicitly as “environmental,” but together, these six themes represent the wide spectrum of missionary attitudes toward nature. Robert’s classification of missionary environmental themes is a solid foundation for studying missionary themes. At the same time, this article tries to nuance and possibly extend the list (Robert 2011).

This article falls into three sections. Section 2 sketches the historical background and context of the photos that will be analysed by studying the exploratory trip of van Randwijck and van der Horst to Nigeria in 1960 and 1961. Their journal reveals explicit and articulated views on the landscapes they encountered. Section 3 introduces the study of colonial and postcolonial missionary photography, develops a methodology for revealing environmental themes, and introduces the corpus. Section 4 analyses a selection of photos taken by several missionaries in Nigeria and reconstructs the missionary gaze of Nigerian landscapes.

2. Analysis of the Diary of van Randwijck and van Der Horst (1960/1961)

With the loss of the colony of the Dutch East Indies in 1949 and New Guinea in 1962, Dutch missionary organisations were pressed to leave the newly independent state of Indonesia (Jongeneel 2018). In May 1957, the International Missionary Council advised the Dutch Missionary Council about “new missionary opportunities,” which focused on “the task of church and mission vis-à-vis Islam in sub-Sharan Africa.”3 The purpose was to make African Christians “spiritually resilient” in their contact with Islam and to build “a Christian society in these young independent states.”4 Dutch missionaries, with much experience with Islam in Indonesia, were seen as valuable partners, although they regarded themselves as “beginners” in West Africa.5

In the winter of 1960, the Dutch Missionary Council dispatched its two secretaries, Count Steven Cornelis van Randwijck (1901–1997) and Dr. Frederik Carel van der Horst (1903–1977), to Western Africa for a fact-finding mission. van Randwijck had been missionary consul in Batavia between 1929 and 1946 and chair of the Committee on Missionary Studies and the World Council of Churches, during which he critically self-reflected on the limits of mission and developmental aid in the age of decolonization (Stiemer et al. 2020). van der Horst was the Council’s medical secretary with a track record of practicing medicine on Sumatra in the Dutch East Indies. They left for Africa on 10 December 1960 and travelled to Algeria, Ghana, Senegal, Togo, Nigeria, and Cameroon, returning to the Netherlands in February 1961.6

Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa. Nowadays, it boasts about 230 million inhabitants (45 million in 1960), comprised of 250 ethnic groups speaking over 500 distinct languages. A British colony, it gained full independence in 1960 within the British Commonwealth and issued general elections. Independent Nigeria was politically unstable, witnessing two military coups in 1966. A civil war broke out in 1967 when Biafra, the southeastern part of Nigeria, unsuccessfully tried to secede. The culturally diverse country is divided by religion, dominated by Islam in the north and Christianity in the south, allowing for a precarious political equilibrium. Nigeria is a large country of almost one million square kilometers, wedged between the Sahel in the north and the Gulf of Guinee in the south. It has four climate zones, ranging from desert in the far north along the border with Chad to hot, arid climate with steppes in the north, tropical savannah climate in most of central Nigeria, and tropical monsoon climate with tropical rainforest in the south around the extensive Niger Delta system. Several large, high plateau mountain regions see moderate temperatures.

This is where van Randwijck and van der Horst arrived in the winter of 1960. The two secretaries kept an extensive journal of their trip, which gives an insight into their considerations and observations. In their writings, they seldom refer to photography, which suggests it was incidental rather than part of a preconceived activity. On one occasion, van Randwijck explains that he is taking photos of a baptism in Fobur in central Nigeria.7 Even so, the explicit stated aim of this trip as a fact-finding mission supports our premise that van Randwijck and van der Horst’s photographs show us their missionary “gaze.”

The journal is littered with reflections on Nigerian landscapes, flora, fauna, agriculture, and climate. This is surprising, as the main purpose of the trip was to investigate possibilities to establish mission stations, hospitals, and ways to strengthen Christian communities vis-à-vis Islam. In a sense, however, the journey must also be regarded as a personal experience, an encounter with the African tropics that made a lasting impression on the secretaries. The journal gives an insight into the missionary “environmental” themes that were important to them. Although these themes were never explicitly articulated, the journals are saturated with observations and reflections on Nigerian landscapes. van Randwijck’s road trip observations, for instance, provide several clues as to his views on Nigerian nature. On 19 January 1961, van Randwijck took a DC3 flight from Ibadan in the southwest to Jos in central-north Nigeria. His journal entry provides a flavour of his observations on Nigerian nature.

When we come a little further north, the landscape below us again has the savannah-like appearance that we know so well from Ghana and Togo. We fly over the Niger and many of its tributaries, which in this dry season contain little water, but still often form a delta-like landscape, wide strips, marshes intersected by creeks on both sides of the main bed, strikingly green in the arid landscape. I even see sawahs! But that is only a very small part of this large, sparsely populated and little forested, unattractive country. After Kaduna, more and more rocks become visible: we arrive at the plateau, in the middle of which Jos lies at an altitude of about 700 meters. The climate here is completely different from that in Lagos and Ibadan: dry, although not as bad as in Northern Ghana (we are a little less far north here) and cool due to the noticeable influence of the difference in altitude. The landscape is much more attractive than anything I have seen in Africa so far: the irregularly shaped rocks provide variety and in the rainy season it must be quite beautiful here.8

The diary of the two secretaries displays several recurring tropes. The first one is the tension between familiarity and alienation. Having had many years of experience in Indonesia, van Randwijck recognizes rice fields from the air. Although African tropical landscapes are new to him, he underscores his familiarity with the savannah landscape after his journeys through Ghana and Togo: “The landscape is ordinary savannah.”9 Understandably, van Randwijk also compares tropical landscape to the temperate landscapes of Western Europe, favouring the latter. In Nigeria, he juxtaposes arid sceneries, which he finds unattractive, with cool green landscapes. The mountainous rock formations around Jos, on a highland plateau, he finds particularly appealing. Travelling by car in the Jos environment, he comments that a “picturesque place with rocks like the setting of an opera is very romantic.”10 Romantic and impressive, those are some of the impressions of the missionaries. Travelling on the high-range plateau to Fobur, he remarks that it is a “beautiful landscape.”11 van Randwijck likes the high plains. “the way there and back takes us through other landscapes on the plateau: wild rocks again and again, which gradually form an unbroken mountain range at the edge. There is more greenery to be seen here in the area than elsewhere, which increases the attractiveness of the landscape, which is always predominantly arid at this time of year.”12

The second trope is a fascination with the exotic. It is noteworthy there are plenty of reflections on the general landscape: savannah, rivers, plains, and shrubland, but there is no single mention of any specific plants (with the exception of rice) or trees. The exception is what would seem like exotic animals to a European. Animals are seldom mentioned in the diaries unless they are wild and exotic, such as leopards, lions, and elephants. Especially the massive leopards in the Gavva area near the Cameroon border, which van Randwijck does not personally see, are a source of fear and wonder. On the way to Gombi, “the road leads us through a very lonely land and we hardly see people along the road. Except for a wild baboon we do not see wild animals, although the rocks could easily be those from the lions’ cage of Artis” [a famous zoo in Amsterdam].13

A third trope is that the landscape is often regarded through the lens of infrastructure. van Randwijck and van der Horst frequently complain about the great distances within Nigeria and the quality of the transportation network. They write about “bad connections” and “warm journeys” by car that take multiple hours.14 When van der Horst travels from Central to Eastern Nigeria and from there to the north, he is exasperated about the obstacles he encounters. He can rent cars, but these are expensive for single trips and not comfortable for the 1 one thousand miles he needs to travel. Trains are scarce and slow, and connections by air are problematic. This is, he concludes, “an impossible country to travel in from place to place to meet people.”15 van Randwijck concludes the same. He has some experience in Indonesia, but “it has become clear to me, that however long the distances are and how bad the roads, the car is the only solution for the nerve wrecking connection problems.”16

The fourth connected trope is the description of African landscapes as “woest” and “wild” to describe the landscape. Whereas “wild” is the equivalent of the same word in English, “woest” has no equivalent; it might mean wild, desolate, or fierce and undeveloped. It is also associated with emptiness: the road from Jos to Bauchi ‘leads through a very lonely and wild [woest] landscape; on the southside of the road is a region where there are elephants.”17 Words like “loneliness” often occur in the diary. The land they travel through is usually seen as a desolate and hostile space with badly maintained roads that make travel problematic.

These kinds of places lack any civilization. Rimboe, occasionally used in the diary, was Malaysian in origin, first used in 1841 to refer to the woods on Sumatra (Sijs and Beelen 2019). It came to symbolize uncultivated and desolate places (Sijs and Beelen 2019). For instance, the people living in the Madara mountains in the Gavva region were described by Basel missionaries Wilhelm Scheytt and Rene Gardi as Steinleute [stone people], a people without tribal name (Gardi and Scheytt 1965, p. 5). van Randwijck similarly refers to them as “incredibly primitive,” people that wear few clothes and carry swords, spears, or bows and arrows.18One might think that the village of Gombi, where we arrive after a three hour drive, is very much in the rimboe [wilderness], but it could be worse: after Gombi we turn into a small bypass, which takes us 23 miles further into desolation. Now and then we can hardly navigate the road with our car; it is mainly “jeepable” […] we are very close to the end of the world, the loneliest place I have ever visited.

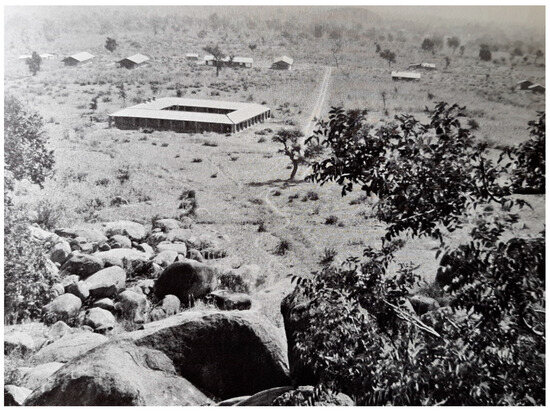

The fifth and related trope is the struggle between civilization and wilderness. Dutch missionary scholar, W.A. Bijlefeld and van Randwijck travel to the far northeast of Nigeria, visiting the hamlet of Gavva, close to Gwoza, and wedged between the Mandara mountain range and the Cameroon border, about five kilometres to the east. Nowadays, the location is an area called Basle, very close to the small village of Ngoshi near the Cameroon border and in the general Gavva area. Gavva was the terrain of the Basel Mission, an orderly compound established in 1959. It consisted of a policlinic, a missionary’s house, and several appartments (“wohnhütte”).19 There had been no missionaries before in the area (Andrawus 2010, p. 116). van Randwijck describes the shed of the Swiss Schoni family as beautiful. He adds that the village of Gavva “cannot be found on any map.” In this rough terrain, the Basel Mission established an orderly compound. The building plan [Basel Missionary Archives KARVAR-31.140] from 1959 shows the geometric logic of the new village, without any reference to surrounding landscape, underscoring the way in which missionaries believed they could control and mould the landscape. The photograph (Figure 1) of the compound and the hospital sharply juxtaposes the ordered compound and the rugged mountainside. It visually presents the Basel compound as a triumph of missionary civilization of the remote and inhospitable desert.

Figure 1.

René Gardi, Gavva, Basel mission station, hospital, and compound seen from mountain, 1965. Reproduced in (Gardi and Scheytt 1965, p. 49).

The sixth trope is remarkable for its virtual absence. Agriculture is a relatively minor theme in the diaries, which is surprising as their first impression of Ghana, which the secretaries visited before Nigeria, is that it is a land whose agriculture is in need of technical improvement to boost food production. “It is a hard and raw country, hunger and sickness threaten lives. Our medical care ensures that more children and adults stay alive. This creates new difficulties. These people should not die from hunger.” van Randwijck discusses this matter with Rev. Lennington in Yendi in Ghana. “Would the need caused by hunger incite them to apply better agricultural techniques?” He also discusses the matter in Ghana with two British Methodist preachers, whether an “agricultural missionary” could “teach the people to grow what the nurse teaches them to eat.” The word “agricultural missionary” is untranslated in the manuscript, suggesting there is no Dutch equivalent.20

The seventh and final trope is the landscape as the theatre of personal challenge and faith. The diaries are littered with comments on the heat and the hardship that is part of the journey of the secretaries. Although they represent the Mission Council, they are also two Christian men travelling in a vast wilderness. This cannot be detached from their spiritual framework, which is rooted in the history and geography of biblical Israel. When van Randwijck attends a baptismal service that takes place along the riverbank, he writes, “This is what it must have been like during the time of John the Baptist.”21 Neither van der Horst nor van Randwijck reflects explicitly on their personal faith journey, but travelling through desert-like and arid areas apparently sparked van Randwijck’s imagination and reminded him of biblical settings and heroes, travelling through wilderness that tested their faith. His reflection brings to mind Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the chronotope, which signified a conflation of time and space. The riverine baptism and the journeys through the desert remind—or perhaps more accurate—transport van Randwijck mentally to the time and land of the Bible and possibly to the lives and challenges of biblical characters.

Thus, from the correspondence, several environmental tropes emerge. The first one is the comparison between tropical and temperate landscapes, in which the latter is favoured. The second trope is a fascination with the exotic. Both are typical for Europeans traveling in Africa and represent a familiar juxtaposition between familiarity and alienation (Driver and Martins 2010, introduction). A third trope is that landscape is regarded as a space for travel and infrastructure, which is understandable in the light of the journeys that the missionaries have. The fourth trope emphasizes the seemingly unredeemable hostile and desolate landscape of some parts of Nigeria. The fifth trope is the struggle between civilization and wilderness. The sixth trope is a moderate interest in the possibilities of agriculture. The seventh, speculative trope is that the landscape was also a theatre for testing one’s faith. Comparing these tropes in the diary to the themes identified by Dana Robert, there is some interest in “living off the land,” very little in “observing nature” but mostly emphasis on the wilderness, its remoteness, and obstacles to transportation. The diary elaborates on Robert’s themes but emphasizes the unredeemable qualities of the wilderness rather than the possibility of civilizing it.

3. (Post)Colonial and Missionary Photography

Missionary photography took off fairly quickly after the invention of the photo camera in 1839. It became a hallmark of both missionaries to report on their work and missionary societies to garner support from their constituencies. Photography was used to document exploration, impress indigenous peoples with the wonders of modernity, and report on missionary successes. Before long, missionary societies realized the potential of photography for propagandic purposes. Missionary festivals and church meetings benefited from magic lantern slides to show photographs to a wider public (Simpson 1997). Missionary periodicals that took off in the early nineteenth century published engravings of photos to embellish stories from the mission field. By the late nineteenth century, new techniques, such as half-tone photomechanical printing, allowed periodicals to publish reproductions of photos (Edwards 2005).

Missionary photography is part of the history of colonial photography. “Most missionary photographers, and most of their home supporters, accepted both the premise that the camera provided an accurate—one can almost say “scientific”—picture of the African, and the idea that the European was superior to the African, not simply technologically, but also culturally, morally, and religiously,” T. Jack Thompson writes (Thompson 2012, p. 2). Its visual style was not qualitatively different from other colonial-era photography in Africa. Colonial photographs sometimes documented atrocities, such as the infamous photos of severed hands in the Belgian colony of Congo (see, for example, Graham 2016). Many more were the diametric opposite: romanticized foreign lands that appeared empty and waiting for cultivation (Nelson 2011). And others documented the proceeds and accomplishments of colonial administration, including anthropological and scientific images that objectified Africans. Photography is therefore sometimes regarded as part of the many technologies that were employed as “tools of empire” (Landau 2002, p. 142).

After the independence of Nigeria and other African countries, photography remained a tool that could be employed to suggest a qualitative distance between Western countries and Africa. A close reading of the photographic style of the standard-setting magazine National Geographic in its coverage of Africa, post-independence, demonstrated the continued existence of familiar gazes and tropes, such as the Westerner as an adventurer in an exciting, wild continent and a racial system with certain visual taboos, such as black men looking at white women (Lutz and Collins 1991). Post-independence missionary photography in Africa should be critically examined and its pre-history taken into account.

Nigeria in the 1960s was a young country. Europeans who took photos were part of structures that, until recently, were formally not part of colonial rule but certainly tightly intertwined with it. After independence in 1960, some of these missionary organizations would endure or be succeeded by the non-governmental organizations we know today, but this change did not happen overnight, and mental structures adapted at a different time scale than a change in legal status. African photographers used the new medium of photography to document their continent soon after the photographic process was developed (see, for example, Hayes and Minkley 2019, pp. 1–10). But most photographs in the century before the independence of Nigeria and most other African countries were made by Europeans. This implied they were taken within the structure of colonialism and therefore tied to the expression of ideas on race, science, and power.

A visual analysis of the photographic album that the missionaries made provides a contrast point to the textual analysis of their travel diaries and other writings. As we will see, many of the seven-point conclusions that are drawn above can be extended to these missionaries’ photography. But one crucial difference remains: while the writings of these missionaries suggest perspective and possibility, they suggest that the wildness of the landscape can be overcome with development (as viewed by these missionaries). Their photography suggests something different: the natural environment of Nigeria regularly appears as something inherently remote and inhospitable, both in a material and in an emotional sense. This differs from the “travelling gaze” of Western visitors that David Arnold identified, which looks upon “wild and tropical” landscapes as tableaus for “improvement” and which contributed to imperial policy (Arnold 2006, p. 6). The wildness that the Dutch missionaries see is more imposing, and the theme of possibility and improvement is not as present in the visual documentation of the missionaries’ travels as in their texts.

To analyse such underlying themes, we will use a three-step method. In the last three decades, since the “pictorial turn” was announced, methods for visual analysis have been proposed, refined, repurposed, and refined again. Out of this steadily growing amount of theory and praxis, no consensus or widely accepted method has arisen for the analysis of photographs (see, for example, Rose 2022). This will not change soon, Gillian Rose observes, as most scholars do not explicitly describe what methods they used for their visual analysis. In practice, however, there has been a convergence of sorts in the methods scholars use for visual analysis. “A slippage between semiology and discourse analysis” has occurred, according to Rose, “so that an amalgam of both in fact seems to be the dominant method” (Rose 2022, p. 74).

In our analysis, we will apply just such an amalgam. Our prime research interest is in attitudes toward the natural environment, in photographs taken by Dutch missionaries in Nigeria in its first years of independence. We will gear our method toward that purpose and anchor it in methods that have been employed in recent scholarship on (post)colonial and landscape photography. We will divide our visual analysis into three steps: description, function, and narrative analysis. In the first step, we will describe the photograph’s composition and visual content in general terms and the subjective impression the photograph makes on us. Then we will reflect on its likely function, using our knowledge of how the photographs were made and their primary audience and clues we find in their captions. For our analysis, we have included all photographs in the album in which Nigeria’s landscape can be seen. These include photographs in which landscape is the only subject of the photograph, but also photographs in which they form a discernible backdrop to the apparent subject in the foreground.

In the narrative analysis, we will analyze the connotation of the natural environment in the photographs (to use the distinction proposed by Roland Barthes): whether it appears to have a suggestive meaning.22 In some photographs, for example, the landscape appears to fulfill the role of “dense wilderness,” or is even ascribed such a role in captions. In our narrative analysis, we will also analyze whether we recognize (neo)colonial or ecological tropes, for example, regarding landscapes that are visualized as neglected resources, waiting to be cultivated, or as natural environments that are romanticized or suffer from “pastoral mismanagement.”23 Following these three steps, we hope to touch on the aesthetics, uses, and meaning of the images in the collections of study.

4. The Nigeria Album: An Analysis

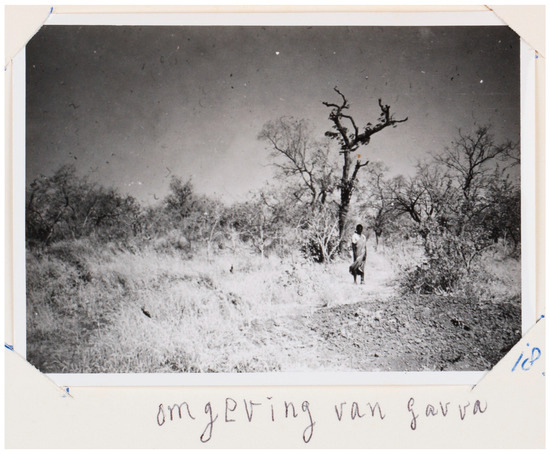

“Surroundings of Gavva” is the simple caption of a photographic print (Figure 2), held in place on a carton page by four cuts, where the photographs’ corners are slid through. The photo was taken in northeastern Nigeria in 1964 by A.H van Soest, a medical doctor with experience in Sumatra and in Ghana. It does not jump out at the first viewing and is perhaps not one that the missionaries who made these photographs might have considered particularly interesting. But it is a photograph that becomes more intriguing at second glance, especially when enlarged. In the picture, a girl or young woman is standing still and looking directly at the photographer. Or at least, the figure appears to be a girl, dressed in a robe that is caught by a gust of wind. And it appears to be looking at the camera, but there is no way to tell for sure: the tones in the photograph are stark, high contrast blacks and whites, and the head of the figure is a monotone shape in which nothing can be discerned.

Figure 2.

A. van Soest, “Surroundings of Gavva” (“Omgeving van Gavva”, 1964), photo no. 18.

The figure is perfectly placed, according to the theory of the Golden Ratio. But the figure does not seem to be the true subject of the photograph. That is the natural surroundings in which the small figure stands: a thickly forested area with a path through it that the figure seems to just have walked down into a clearing of tall grasses and rocks. The trees appear gnarled, especially a striking, tall tree that stands tall over the figure. And the natural landscape seems to literally stick to the photograph: all over the image are light and dark specks, presumably of dust that has stuck to the negative when it was hung out to dry, possibly even in the area in which the photograph was made.

It is photo nr. 18 in a neatly ordered photo album. Our analysis is based on a series of 65 photos, taken by missionaries in Nigeria between about 1960 and 1967. The selection is non-selective; that is, we did not focus on “environmental photos,” but on an album produced by the Missionary Council and kept in Het Utrechts Archief.24 A list and description of these photos are added to this article as Appendix A. The photographs in the album were made by at least five photographers, going by the captions and archival information: Dr. K. Reynierse, Dr. N. Bakker, J.C. van Randwijck, Rev. J. Hoekstra, and Dr. A. van Soest.

The fact that several photographers collaborated on one collection makes this album a valuable source in a search for a “missionary environmental gaze,” as its visual style and interest transcends that of a single photographer, while the photographs were made under similar circumstances. Several authors collaborated on making the physical album: at least three different handwritings can be identified in the captions. These facts combined suggest that this album is a selection, made by the photographers themselves, from the photographs with which they returned. It is part of the extensive photo collection of the Missionary Council that was probably established sometime between 1900 and 1940 in its Oegstgeest headquarters and was transferred by the Dutch Protestant Church to Het Utrechts Archief in 2016. Since the album was made and used by the Dutch Reformed Mission Council, it is likely that the photographers selected photographs that they perceived to be in line with that of the Council, namely, to show its sponsors what their contributions financed and illustrate to people within the Council the challenges and opportunities of relocating its missionary activities to Nigeria. It is, in other words, most likely a curated album, with a specific audience in mind. This makes it all the more suitable to reveal unstated and implicit attitudes toward the natural environment.

In this collection, photo 18 is just one of many photographs that hint that the photographers were sensitive to the natural landscape in which they operated. Many photographs are framed in a way that allows the surrounding landscape of a depicted scene to be included in the photograph. In others, the photographic angles that the photographers choose suggest that they wished to include the landscape in their picture. In others, such as this photograph 18, the landscape appears to be the subject itself.

If we follow the methodology we set out above, we would first describe the photograph as done above. Its function seems straightforward because the byline simply announces the photograph as depicting the “Surroundings of Gavva.” This caption was added later, in a handwriting and pen different from the person who presumably made the photo album and numbered it.25

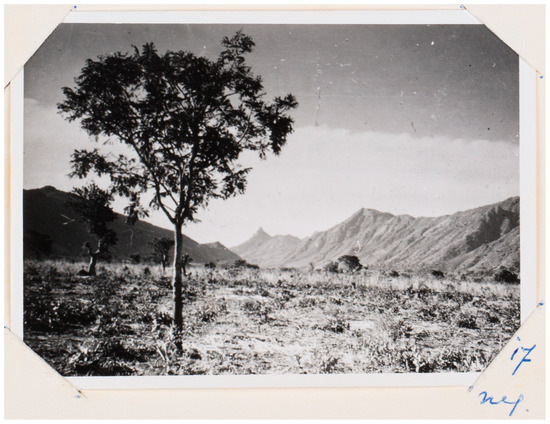

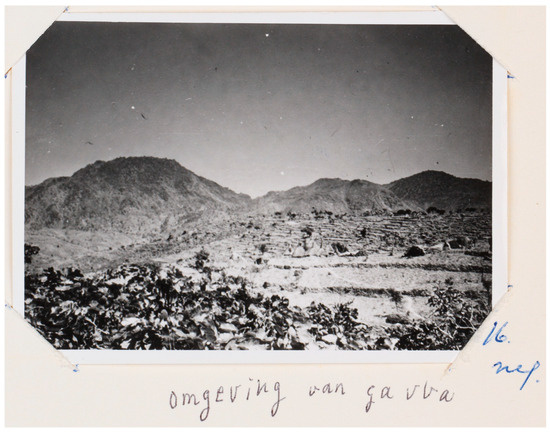

Similar in feel are the two photographs that precede it, also taken by van Soest in the Gavva area. In these photographs, we see high hills that rise sharply from a valley floor. In both photographs, the sky takes up the upper half of the photographs, with vegetation in the foreground: a tree in one of the photos (Figure 3) and shrubs in the other (Figure 4). In this latter one, the valley appears to contain crop fields; in the other, vague shapes of people and houses can be made out. But they certainly do not appear to be the central subject of the photo, that is, the natural setting. “Surroundings of Gavva” is also the sparse captioning for these photos.

Figure 3.

A.H. van Soest, Surroundings of Gavva (1964), photo no. 17.

Figure 4.

A.H. van Soest, “Surroundings of Gavva” (“Omgeving van Gavva”, 1964), photo no. 1.

In these three photographs, the landscape appears to be the central subject: people are small, hardly visible, or even absent. The emptiness and vastness of this region, which van Randwijck and the other authors describe in their letters, is made visible here. The land seems mysterious, unforgiving, and vast, not necessarily hostile but indifferent and imposing. It seems a visual metaphor for how daunting the missionaries regard the task of relocating their activities here. If this could be connected to a well-known trope, it would be that of the imposing wilderness, presenting a tough but worthy challenge to the foreigners who come here on a mission.

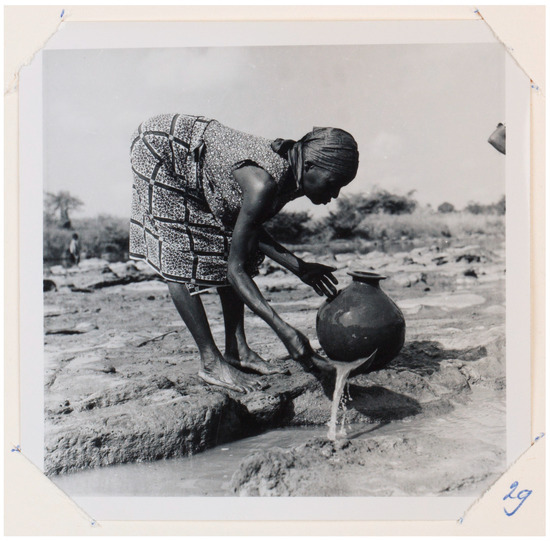

More often, however, northern Nigeria’s natural landscape appears in the photographs as an added layer of information to the people that the missionaries photograph. In a number of photographs, the local people are captured during a particular task, but the framing of the picture is expanded so the natural surroundings can be included. Over three pages, for example, the task of winning salt is photographed by K. Reynierse in 1967. In all but one of the eight photographs (28 through 34), the frame is visibly expanded beyond the salt-winning activity to include the backdrop of trees, shallow lakes, and the horizon. In one photograph, nr. 29 (Figure 5), the photographer has taken the photograph while kneeling, apparently so the backdrop of a salt lake and a tree line could be included in the frame.26

Figure 5.

K.K. Reynierse, Salt lake and preparation of salt in Uburu (year unknown), photo nr. 29.

In these photographs, local people (apparently all women) can be seen in various stages of winning salt—or just the clay pots used in the process—with the natural landscape in the background. That landscape appears neither imposing nor empty, but rather as the supplier of the valued resource. In photograph nr. 4—also about winning salt—this is likewise.

In a number of photographs in the album, the photographers turn their camera on a different corner of Nigeria and a completely different landscape: on the broad rivers and lush vegetation of Nigeria’s southeast. These photographs are presented together with those taken in Nigeria’s northeast. Although a location is usually given (often by a second captioner, adding to more general information in a first caption), the photographs in Nigeria’s different regions are not treated as distinct from each other and presented alongside each other.

But of course, the landscape in these photographs is very different. In the photographs taken in Nigeria’s southeast, many are taken of rivers. The first river appears on a page that is apparently devoted to children: a first photograph (nr. 21) depicts the “two Middelkoop children” playing with a local boy and a second (no. 22, Figure 6), seven local children who play in a river.27 They are shown in a relaxed mood, and the river is shown in its entire width: the tree line on the opposite bank is included, as well as a small boat. Both photos were taken by van Randwijck in 1965 along the Cross River, in the far south of Nigeria.

Figure 6.

J.C. van Randwijck, “Children from the settlement of Itigidi/at the Cross River” (“Kinderen v.d. gemeente Itigidi. bij de Cross River”, 1965), photo nr. 22.

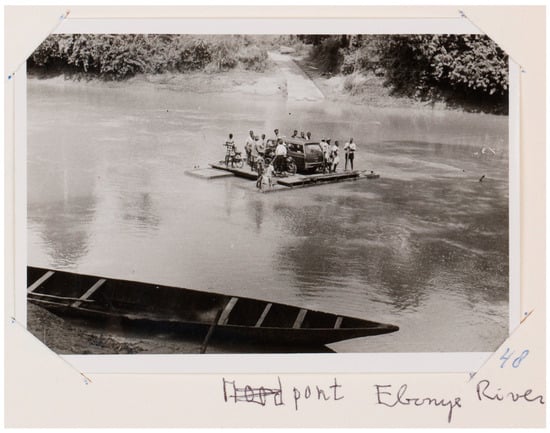

That same river, the Cross River, is the subject of two pages of photos further on, taken by K. Reynierse in 1965. Photo 47 shows a raft midstream, with a white truck on it, and about eight men who are pushing the ferry across. Below it (48) is a raft with about eight men and a station wagon crossing a river, then two photos (49 and 50) of a larger ferry, and one (51) of local people on its deck.28

Interestingly, there has apparently been disagreement between at least three people who have provided captions in this album. One caption is simply crossed out. It said, “Flooding bridge broken.” Apparently someone else disagreed. Below, the same author called a raft an “emergency ferry,” but the “emergency” part was crossed out (Figure 7). It is unclear whether the last to hold the pen was simply attached to truthful reporting or whether it was an attempt to downplay certain exaggerations and, with them, a tale of wild nature, forcing people to improvise to survive its whims, a possible rejection of overdrawn dramaticism about Nigeria’s nature.

Figure 7.

K. Reynierse, “Emergency ferry Ebonye River” (“Nood pont Ebonye River”, strikethrough in original title, ca. 1965?), photo nr. 48.

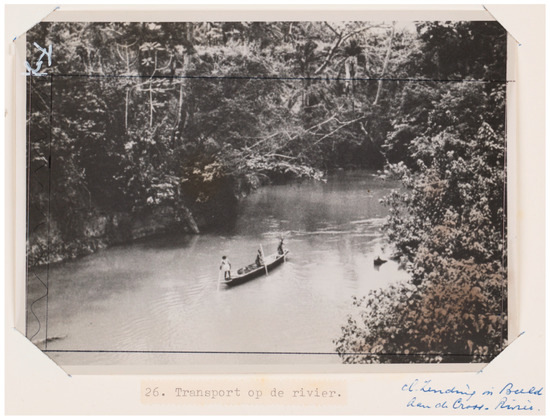

Such a dramatic setting seems to be the true subject of one photo of a river (nr. 26, photographer and year unknown), with a seemingly small boat with three people on it—all with poles to guide or push the boat—in the middle of an imposing jungle.29 The seemingly first description of this photograph, typed and then glued into the album, captions the photograph as “Transport on the river.” The second, handwritten comment, next to the typed caption, describes the scene as “Chr. Mission on Display At the Cross River” (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Photographer unknown, “Transport on the river. Chr. mission on display. At the Cross River” (“Transport op de rivier. Ch. Zending in Beeld. Aan de Cross River.”, year unknown), photo nr. 26.

For the narrative function of this photograph, these two readings make a big difference. In the first, we are simply looking at local commerce; in the second reading, the photo is a visual statement on the perseverance of the missionaries in the face of great challenges. It is impossible to assert which of these descriptions is correct, but the reading given in the second caption does connect to the theme of wildness and the challenge of mission in this demanding land. This chimes well with the seventh trope identified in the diary, in which the “biblical” landscape can be regarded as a theatre for a personal challenge of faith.

In the photographs and themes that are singled out above, the natural environment is strikingly present as subject or symbolic layer of the images. But throughout the entire collection, landscape is an ever-returning theme. The missionaries’ prime subject appears to be the local people they meet, and landscape is often used to add information about them—where they produce their crops or salt, how they navigate waterways, etc.—or which environment (physical or symbolic) awaits the missionaries who should decide to work among them.

Using the landscape as the central subject of a photograph, or as location of local production and transport, is just one way in which the natural environment features in these photographs. Another way in which landscape plays a visual role is when a certain scene is depicted, but the photographic frame is widened to encompass (more of) the natural surroundings in which this scene is set. Examples are photographs of local people who are gathered in small groups or when villages or particular buildings (such as a hospital) are photographed. (This is the case, for example, in the photographs numbered 4, 14, 22, 30, and 33.)30

If we regard the above paragraphs as the first two steps in our visual analysis—those of description and the analysis of function—we will now turn to narrative analysis or the connotation of the natural environment in these photographs. Perhaps a good starting point is the photograph (Figure 1) that was taken in the same Gavva area, but by Swiss missionaries, a photo that is not in “our” photobook. In the photograph of the Basel mission station, the rough natural environment around the station is broken by the perfect, rational rectangle of the station, behind which we can see other buildings in a neat line. This photograph suggests that the wildness of the landscape is overcome by the modern answer to it, the development model as embodied by the new, Western-built structures and that which their occupants bring. This photograph can serve as a fitting contrast point to those in the photobook because such photographs—which suggest the ultimate triumph of Western mission and aid over the challenges, symbolized by the landscape—are not there.

There are, in fact, several comparable photographs in which we can see buildings or cultivated fields, but where the visual frame contains so much of the natural setting that it appears to be as much the intended subject of the photograph as the depicted activity or location (for example, in photographs nr. 9, 10, 11, 62, and 63).31 In these photographs, the natural setting appears as harsh and imposing. Photograph nr. 10 is titled “Settlement near Gavva,” and indeed, if one looks well, some buildings can be discerned. But they are barely visible behind a web of thick, spikey branches, which cover the foreground, that seem to overgrow the village. If we follow John Fiske’s definition that “denotation is what is photographed, connotation is how it is photographed,” it is clear that there is a remarkable difference here between the two (Fiske 1989, pp. 312–16). It is a fitting illustration of a landscape that seems to loom over the people, hospitals, and missions in these photographs: an intimidating and overbearing presence.

Photograph nr. 9 is comparable in function to the photograph of the Basel mission station. It is captioned “The hospital in Guoza” and shows various buildings. However, half of the photograph consists of a barren field leading to the hospital and the shade from where the photographer escaped the heat. The buildings themselves seem to be on the verge of being overgrown by vegetation; in the background, high hills or mountains loom over the hospital. These features of the image could, of course, be just by chance or due to the limited photographic abilities of the photographer. But it was selected to feature in an edited volume, and the narrative function of the natural environment is similar to that in other photos: to relate the wild and challenging environment of the missionaries’ work, but with no visual suggestion that these challenges will ultimately overcome—or indeed are very suitable for the mission itself.

Notable is also what is not there in the photographs of these missionaries. There are almost no photos of individual plants or trees, animals, mountains, or rivers when there is no human presence or human industry to accompany the wider frame.32 The “environmental gaze” of these missionaries is, in fact, more an ecological one: a view of nature that is always connected to humans and not autonomous.

Taken together, the photographs in the album therefore reveal a visual approach toward nature that is different in a subtle but important way from that in our visual contrast point, of the Basel mission station. And an important connotative difference can also be read within the photo collection itself. Because the way human subjects are depicted in the photographs is different than how the natural environment is depicted, or, put differently, their narrative function appears to be different. The humans in the photographs (locals the missionaries meet or work with) are often smiling, usually relaxed, and portrayed in a casual manner. Friendly and hospitable, one could say.

Therefore, if this was indeed an “orientation” to map the opportunities and obstacles to missionary work, then the underlying visual motif of human encounters in these photographs would suggest a “go,” a population ready to work with the missionaries and open and hospitable to them. The natural environment has a different narrative function in this “orientation”: it portrays the landscape as closed and alien, not necessarily hostile or dangerous, but too barren and vast for a proper interaction, too strange and inhospitable to really relate to. With some exaggeration, one could say that the depiction of nature would rather suggest a “no-go” to the question of whether missionary activity in this region is a good idea. In that capacity, these photographs could illustrate the greatness of the call to overcome such obstacles, as the captioner alluded to in the photograph on the Cross River. But they did not suggest a natural environment in any way inclined to yield what the missionaries had in mind—and neither the suggestion of that ultimately, these obstacles would surely be overcome.

A second general conclusion can be that the dominant “environmental gaze” in these photographs does not look upon Nigeria’s nature as an inviting or underdeveloped resource or as a romantic vista, but rather as wild and inhospitable surroundings for the people that live or choose to be here. This gaze connects both to the first ecological theme proposed by Dana Robert, of the biblical calling to penetrate and civilize wilderness, as well as the fourth ecological theme in the Dutch missionaries’ texts: that of the wildness, loneliness, and “woest” nature of Nigeria’s landscape.

As in the missionaries’ travelogue, there are no hints in this “gaze” that call upon the viewer to help subjugate and develop this landscape or that present it as one of promise and untapped value. Rather, the wildness of the land surrounding local people and missionaries is presented as an autonomous feature of the land. It is visually connected to humans as an inescapable and unchangeable dimension of their lives and as much an obstacle and challenge to their well-being as to Christian mission. Rather than romantic, this gaze is its opposite: a stark gaze, underlining the persistence needed to live and prosetelyze here. This gaze acknowledges a formidableness and indifference in Nigeria’s landscape but does not necessarily see beauty in it.

5. Conclusions

The photos of the Nigeria album thus convey multi-layered narratives of Western missionaries about the land. On a superficial level, the album is an eclectic collection of various kinds of photos of people, buildings, trees, landscapes, and exotic animals, a snapshot interpretation of missionaries travelling a land they are unfamiliar with. Whereas their mission was to focus on mission-funded activities such as hospitals and schools, the photos show a far wider range of topics that caught their interest and reveal attitudes toward things intentionally or unintentionally caught in the frame.

On a deeper, symbolic level, the sum of the individual photographs in this collection appears to contribute to a classic anthropocentric narrative about the natural environment of Nigeria as places of wildness, mystery, allure, remoteness, barrenness, physical, and mental challenges and (“primitive”) subsistence agriculture (see, for example, Ulman 2015). The parallels with the objections and mental construct of Christian mission are clear: as a demanding, unpredictable, exposed, but noble and rewarding activity. It mythologizes the hardness of the land, offering insight into Nigeria of the 1960s as much as the worldview and attitudes of the album’s creators.

In a number of ways, the photos complement the diaries of the missionaries, in which the exotic wild and desolate remoteness of Nigerian landscapes is often referred to, as well as the rugged beauty and barren ugliness of landscapes. But when reading these photographs “against the grain” and interpreting their narrative function, they differ in a subtle but important way from the travel diaries in the sense that although there are textual traces that juxtapose the wildness of the terrain against the challenges of mission (for example, in a caption that describes “Christian mission on display” against an imposing jungle setting), there are few visual traces in the narrative of the photobook that suggest that the remoteness, wildness, and barrenness of the landscape will undoubtedly yield to the energies of missionaries.

Judging by its visual narrative, therefore, the “orientation” of Count van Randwijck, Dr. Reynierse, and others does not align neatly to contemporary missionary photography; it is not an upbeat vision of a landscape “before,” which will soon be transformed into a landscape “after” (after changes in the direction of missionary development ideals), but an awed view of a wild and daunting place. The “environmental gaze” one can find in this vision is one that presents wildness as an autonomous and unchangeable feature of Nigeria’s landscape. If we regard the “travelling gaze” of European travellers in the nineteenth century as a romantic one, this gaze is certainly. It envisions European endeavors here not in dreamy but rather in stark and unsentimental terms.

This article has shown how an analysis of missionary landscape photography can provide insight into the historical Western environmental gaze of the tropics. As such, it proposes a new line of inquiry that investigates cultural and religious layers of this Western gaze, in particular, at the inflection point between the colonial and postcolonial age.

The overlap and spillover between colonial, missionary, scientific, and environmental photography, as practiced by Western officials, missionaries, scientists, and others in non-Western countries, has been demonstrated in several studies. With a close investigation of the explicit, implicit, and symbolic layers of meaning in the visual sources and captioning in a photo collection made by Dutch missionaries during an orientational journey in Nigeria and the various textual sources connected to this journey, we were able to paint a more precise picture of their attitudes toward the natural environment they traversed. We found traces of various visual tropes in the photography of landscapes and nature and demonstrated that the stated function of these photographs and their symbolic message did not always align. Put differently, the (post)colonial and missionary tropes in the visual messaging of this photobook differed from the “environmental gaze” that can be read in them.

As such, this study proposes a new way of investigating (post)colonial and missionary photographic collections. Not only the cultural and political layers of meaning of such collections can be investigated, but their environmental layers of meaning as well. A close reading of this collection of visual sources and their associated textual sources reveals an “environmental gaze” at Nigeria’s landscape that can be used as a contrast point to political and cultural analysis or be studied in its own right. We hope that this approach will be used to study other photographic and visual collections in missionary archives and elsewhere to reveal additional layers of information in sources that document our world, its people, and its natural environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition: R.V.d.H., D.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Het Utrechts Archief, 1567—424: Photo’s Missionary Council, Nigeria 1962–1988 |

| 1. “Mosque in Kano, Nigeria” (photo Basler Mission Deutscher zweig Stuttgart) |

| 2. “The entrance of the emir’s palace in Zaria, in Haussa style” (photo J.C. Van Randwijck) October 1962, januari 1967 |

| 3. “Woman of the Jarawa-stam,” July/August 1963 (with inset photo) (photo J.C. van Randwijck) |

| 4. “Fetching water from the salt lake at Uburu” (photo dr. (k.) K. Reynierse, September 1963, south-east Nigeria |

| 5. “Village cabins in Uburu” (photo K. Reynierse) |

| 6. “A beautiful large Haussa house in a village” (northern Nigeria) (photo J.C. van Randwijck) |

| 7. “Dr. Bijlefeld’s car in the dense wilderness” (photo J.C. van Randwijck, 1962?) |

| 8. “Small settlement in the mountains at Garva” (photo Ds J.M. Hoekstra, June 1964) |

| 9. “The hospital in Guroza” (photo J.M. Hoekstra, June 1964) |

| 10. “Settlement near Gavva” (photo J.M. Hoekstra, June 1964) |

| 11. “Circular guest cabin in Gavva” (photo J.M. Hoekstra, June 1964) |

| 12. “Inhabitants of Gavva” (A. van Soest, October 1967) |

| 13. “A guest cabin for patients of the policlinic”/“women returning from the fields with baskets with products on their heads” (photo A. van Soest, October 1967) |

| 14. “Women at the water well, Gavva” (A. van Soest, October 1964) |

| 15. “Women working the field at Gavva” (photo A. van Soest, 1964) |

| 16. “Environment of Gavva” (photo A. van Soest, 1964) |

| 17. “Landscape with mountains” (photo A. van Soest, 1964) |

| 18. “Environment of Gavva” (photo A. van Soest, 1964) |

| 19. “African woodcuts in the Presidential hotel in Enugu” (eastern NIgerai, Igbo territory) (photo J.C. van Randwijck, 1965). |

| 20. “An African city seen from the air” (photo J.C. van Randwijck, 1965) |

| 21. “The two Middelkoop children playing with a boy from Itigidi”/“Peter and Afke” (photo J.C. van Randwijck, 1965) |

| 22. “Children from the village of Itigidi”/“at the Cross River” (photo J.C. van Randwijck, 1965) |

| 23. “Yoruba women in Sunday clothing” (photo J.C. van Randwijck, 1965) |

| 24. “In Africa crocodiles still exist” (photo J.C. van Randwijck, 1965) |

| 25. “Christian village chief in a village near Zaria”/“northern Nigeria” (photo J.C. van Randwijck, 1965) |

| 25. “In rainy season people work hard in Gavva” (photo not there) |

| 26. “Transport on the river, mission in view. At the Cross River” (photographer and year unknown) |

| 27. “Lagos” (Annual report Missionary Council 1964) |

| 28–34. “Salt lake and preparation of salt” (photos K. K. Reynierse, Uburu, Eastern Nigeria) |

| 35. “Village cabins, Uburu” (photo K. K. Reynierse) |

| 36. “Village cabins in Uburu, Eastern Nigeria” (photo K. K. Reynierse, January 1967) |

| 37. “Old market in Uburu” (photo K. Reynierse) |

| 38–40. “The witch doctor in Uburu” (photos K. Reynierse) |

| 41. “Fulani”/“man travelling” (inset photo) (1967?) |

| 42. “Signboard”/“from one of the shops” (1967?) |

| 43. “Group of young people, Port Haremut?” |

| 44. “Leprosy village Uburu” (photo K. Reynierse, ca. 1965?) |

| 45. “Market of Uburu” (photo K. Reynierse, ca. 1965?) |

| 46. “Sagged bridge after a landrover passed, leprosy service with Okocha, Head of leprosy service” (photo K. Reynierse, ca. 1965?) |

| 47. “Eboinije River between Itigidi and Uburu” (photo K. Reynierse, ca. 1965?) |

| 48. “Ferry Ebonye River” (photo K. Reynierse, ca. 1965?) |

| 49. “Ferry Cross River Itigide” (photo K. Reynierse, ca. 1965?) |

| 50. “Ferry Obuba Cross river” (photo K. Reynierse, ca. 1965?) |

| 51. “On the ferry” (photo K. Reynierse, ca. 1965?) |

| 52. “Uburu village” (photo K. Reynierse, ca. 1965?) |

| 53. “Cabin of a native doctor, with eggs on the roof, amulets in front of the cabin” (photo K. Reynierse, ca. 1965?) |

| 54. “Haussa trader” (photo K. Reynierse, ca. 1965?) |

| 55. “Haussa trader” (photo K. Reynierse ca. 1965?) |

| 56. “Boy in Gavva” (photo N.J.A. Bakker, Gavva Ngoshie 1966–1967) |

| 57. “Mrs. Bakker with several girls in the garden, sewing lessons” (photo N.J.A. Bakker, Gavva Ngoshie 1966–1967) |

| 58. “Water is difficult to find” (photo N.J.A. Bakker, Gavva Ngoshie 1966–1967) |

| 59. “Meeting with lady selling eggs”/“has the Bakker daughter” (photo N.J.A. Bakker, Gavva Ngoshie 1966–1967) |

| 60–62. “threshing and stomping of millet” (photo N.J.A. Bakker, Gavva Ngoshie 1966–1967) |

| 63. “Hamlet just above the hospital” (photo N.J.A. Bakker, Gavva Ngoshie 1966–1967) |

| 64. “Girls weaving baskets” (photo N.J.A. Bakker, Gavva Ngoshie 1966–1967) |

| 65. “Market in Nigeria”/“East” |

Notes

| 1 | For example, the photographs of New Zealand, commissioned by the British Colonial Office, or those of California by Carleton Watkins, commissioned by several mining companies, or the photographs of the embedded photographers in the French colony of Algeria in the nineteenth century. |

| 2 | Het Utrechts Archief, 1567: Photos of the Mission Council, Raad voor de Zending; 424 Nigeria 1962–1968. |

| 3 | Raad voor de Zending van de Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk, Jaarverslag over 1960 (Oegstgeest, 1961), 10–12. |

| 4 | Trouw, 5 April 1961. |

| 5 | Raad voor de Zending, Jaarverslag over 1961, 5. |

| 6 | Trouw, 19 November 1960. |

| 7 | Diary of van Randwijck and van der Horst, f. 70: 28 January 1961. |

| 8 | Het Utrechts Archief, 1102-2 (reports of business trips of secretaries and other members of the Mission Council 1960–1998), inv. 4866 (letters and reports of van Randwijck and van der Horst), Diary of van Randwijck and van der Horst, ff. 53–54. All quotes in this article have been translated from Dutch by the authors. |

| 9 | Diary of van Randwijck and van der Horst, entry van Randwijck, f. 67: 25 January 1961. |

| 10 | Diary of van Randwijck and van der Horst, entry van Randwijck, f. 55: 19 January 1961. |

| 11 | Diary of van Randwijck and van der Horst, entry van Randwijck, f. 70: 28 January 1961. |

| 12 | Diary of van Randwijck and van der Horst, entry van Randwijck, f. 71: 28 January 1961. |

| 13 | Diary of van Randwijck and van der Horst, entry van Randwijck, f. 73: 1 February 1961. |

| 14 | Diary of van Randwijck and van der Horst, entry van Randwijck, f. 52: 17 January 1961. |

| 15 | Diary of van Randwijck and van der Horst, entry van Randwijck, f. 65: 24 January 1961. |

| 16 | See note 15 above. |

| 17 | Diary of van Randwijck and van der Horst, entry van Randwijck, f. 72: 30 January 1961. |

| 18 | Diary of van Randwijck and van der Horst, entry van Randwijck, f. 75. 1 February 1961. |

| 19 | Plan of Gavva missionary station, Basel Missionary Archives, KARVAR-31.140 (1959). |

| 20 | Diary of van Randwijck and van der Horst, entry van Randwijck, f. 52: 18 January 1961. One agriculture and mission, see (Mauritz 1996). |

| 21 | See note 12 above. |

| 22 | Barthes distinguished between the denotation of an image (what is visually presented) and its connotation (what is suggested). This distinction is, for example, successfully used in (Benjaminsen 2021). |

| 23 | Recent scholarship in which these tropes are analyzed include (Benjaminsen 2021; Waldroup 2024; Hore 2022; Wells 2022; Protschky 2011). |

| 24 | See note 2 above. |

| 25 | According to Thom van der End (personal message), who catalogued the photos as from 2017, a set of descriptions was added to the photos in the 1990s by the secretary of the Mission Council. |

| 26 | Salt lake and preparation of salt (photo’s K. K. Reynierse, Uburu, Eastern Nigeria). |

| 27 | “The two Middelkoop children playing with a boy from Itigidi”/“Peter and Afke” “Children from the village of Itigidi”/“at the Cross River” (photo J.C. van Randwijck, 1965). |

| 28 | The Ebonye and Cross Rivers, by K. Reynierse, ca. 1965. |

| 29 | “Transport on the river, mission in view. At the Cross River” (photographer and year unknown). |

| 30 | 4: “Fetching water from the salt lake at Uburu” (photo dr. (k.) K. Reynierse, September 1963, southeast Nigeria); 14. “Women at the water well, Gavva” (A. van Soest, October 1964); 22. “Children from the village of Itigidi”/“at the Cross River” (photo J.C. van Randwijck, 1965); 30 and 33. Salt lake and preparation of salt (photo’s K. K. Reynierse, Uburu, Eastern Nigeria). |

| 31 | 9. “The hospital in Guroza, 10. Settlement near Gavva, 11. Circular guest cabin in Gavva”: all three by J.M. Hoekstra, June 1964; threshing and stomping of millet; “Hamlet just above the hospital” (photo N.J.A. Bakker, Gavva Ngoshie 1966–1967). |

| 32 | An exception is, for instance, photo 24, a close-up of crocodiles. |

References

Primary Sources

Basel Missionary Archives, Plan of Gavva missionary station, KARVAR-31.140 (1959).HUA 1102: Het Utrechts Archief (HUA), 1102-2 (reports of business trips of secretaries and other members of the Mission Council 1960–1998), inv. 4866 (letters and reports of Van Randwijck and Van der Horst).HUA 1567: Het Utrechts Archief (HUA), 1567: Photos of the Mission Council, Raad voor de Zending; 424 Nigeria 1962–1968, Nigeria 1962–1968, no. 7 (photo J.C. van Randwijck, 1962).Kappelhof, A.C.M. et al. Repertorium van Nederlandse zendings- en missie-archieven 1800–1960 (The Hague, 2011): Lijst van zendingswerkers (mannen en vrouwen) uitgezonden tussen 1800 en 2011.Raad voor de Zending van de Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk, Jaarverslag over 1960 (Oegstgeest, 1961).Raad voor de Zending van de Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk, Jaarverslag over 1961 (Oegstgeest, 1962).Raad voor de Zending van de Nederlandse Hervormede Kerk, Jaarverslag over 1966 (Oegstgeest, 1967).Raad voor de Zending van de Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk, Jaarverslag over 1967 (Oegstgeest 1968).Dagblad van het Noorden.Deventer Dagblad.Leeuwarder Courant.Parool.Trouw.Tubantia.Secondary Sources

- Andrawus, Dauda Gava. 2010. A Critique of Discrimination on the Basis of Poverty in the Epistle of James: A Case Study of the Church of the Brethren Gavva Area. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, David. 2006. The Tropics and the Travelling Gaze: India, Landscapes and Science, 1800–1856. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benjaminsen, Tor A. 2021. Depicting decline: Images and myths in environmental discourse analysis. Landscape Research 46: 211–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, F., and L. Martins, eds. 2010. Tropical Vision in an Age of Empire. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Elizabeth. 2005. Missionaries and photography. In The Oxford Companion to the Photograph. Edited by Robin Lenman and Angela Nicholson. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Endfield, Georgina H., and David J. Nash. 2002. Drought, Desiccation and Discourse: Missionary Correspondence and Nineteenth-Century Climate Change in Central Southern Africa. The Geographical Journal 168: 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etherington, Norman, ed. 2008. Missions and Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, John. 1989. Codes. In International Encyclopedia of Communications. New York: Oxford University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gardi, René, and Wilhelm Scheytt. 1965. Gavva. Basel: Basileus Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Aubrey. 2016. One hundred years of suffering? “Humanitarian crisis photography” and self-representation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In Photography in and out of Africa. Edited by Kylie Thomas and Louise Green. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Grove, Richard. 1989. Scottish Missionaries, Evangelical Discourses and the Origins of Conservation Thinking in Southern Africa 1820–1900. Journal of Southern African Studies 15: 163–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Catherine. 2002. Civilising Subjects: Metropole and Colony in the English Imagination 1830–1867. Oxford: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Patricia, and Gary Minkley, eds. 2019. Ambivalent: Photography and Visibility in African History. Athens OH: Ohio University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hore, Jarrod. 2022. Visions of Nature. How Landscape Photography Shaped Settler Colonialism. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Paul. 2001. On using historical missionary photographs in modern discussion. Le Fait Missionaire 10: 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongeneel, Jan Arie Bastiaan. 2018. Nederlandse zendingsgeschiedenis. Ontmoeting van protestantse christenen met andere godsdiensten en geloven (1601–1917). part 2. Zoetermeer: Boekencentrum. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, Paul. 2002. Empires of the Visual: Photography and Colonial Administration in Africa. In Images & Empires. Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa. Edited by Paul Landau and Deborah Kaspin. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, Catherine, and Jane Collins. 1991. The Photograph as an Intersection of Gazes: The Example of National Geographic. Visual Anthropology Review 7: 134–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauritz, Rutger Frans. 1996. Landbouw als zending: De agrarische zending van Edinburgh (1910) tot Accra (1957/58). Unpublished Master’s thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, David. 2011. Photography and the Religious Encounter: Ambiguity and Aesthetics in Missionary Representations of the Luba of South East Belgian Congo. Comparative Studies in Society and History 53: 38–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, David, and Patrick Harries, eds. 2012. The Spiritual in the Secular. Missionaries and Knowledge About Africa. Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Mulwafu, Wapulumuka O. 2004. The Interface of Christianity and Conservation in Colonial Malawi, c. 1850–1930. Journal of Religion in Africa 34: 298–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Robert L. 2011. Emptiness in the Colonial Gaze: Labor, Property, and Nature. International Labor and Working-Class History 79: 161–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protschky, Susie. 2011. Images of the Tropics: Environment and Visual Culture in Colonial Indonesia. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, Dana L. 2011. Historical Trends in Missions and Earth Care. International Mission Research Bulletin 35: 223–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Gillian. 2022. Visual Methodologies. An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. Oxford: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sijs, N. van der, and Hans Beelen. 2019. Jungle, rimboe, oerwoud. Onze Taal 5: 29. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Donald. 1997. Missions and the magic lantern. International Bulletin of Missionary Research 21: 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, Brian. 1990. The Bible and the Flag: Protestant Missions and British Imperialism in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Leicester: Apollos. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, Brian. 2015. Gardening for the gospel: Horticulture and mission in the life of Robert Moffat of Kuruman. In Pathways and Patterns in History: Essays on Baptists, Evangelicals, and the Modern World. Edited by Peter Morden, Anthony Cross and Ian Randall. London: Wipf and Stock, pp. 354–68. [Google Scholar]

- Stiemer, Ruud, Rob van Essen, and Anton Wessels. 2020. De eeuw van Verkuyl, van Randwijck en Blauw. Tussenruimte. August 21. Available online: https://www.theologie.nl/de-eeuw-van-verkuyl-van-randwijck-en-blauw/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Thompson, Jack. 2012. Light on darkness? Missionary Photography of Africa in the 19th Early 20th Centuries. Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Ulman, Lewis. 2015. Beyond nature photography. The possibilities and responsibilities of seeing. In Ecomedia: Key Issues. Edited by Stephen Rust, Salma Monani and Sean Cubitt. London: Earthscan/Routledge, pp. 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Waldroup, Heather. 2017. Indigenous Modernities: Missionary Photography and Photographic Gaps in Nauru. The Journal of Pacific History 52: 459–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldroup, Heather. 2024. Photographs as layered objects in Oceania. Journal of New Zealand & Pacific Studies 12: 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, Liz. 2022. Land Matters. Landscape Photography, Culture and Identity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Woodberry, Robert D. 2012. The Missionary Roots of Liberal Democracy. American Political Science Review 106: 244–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).