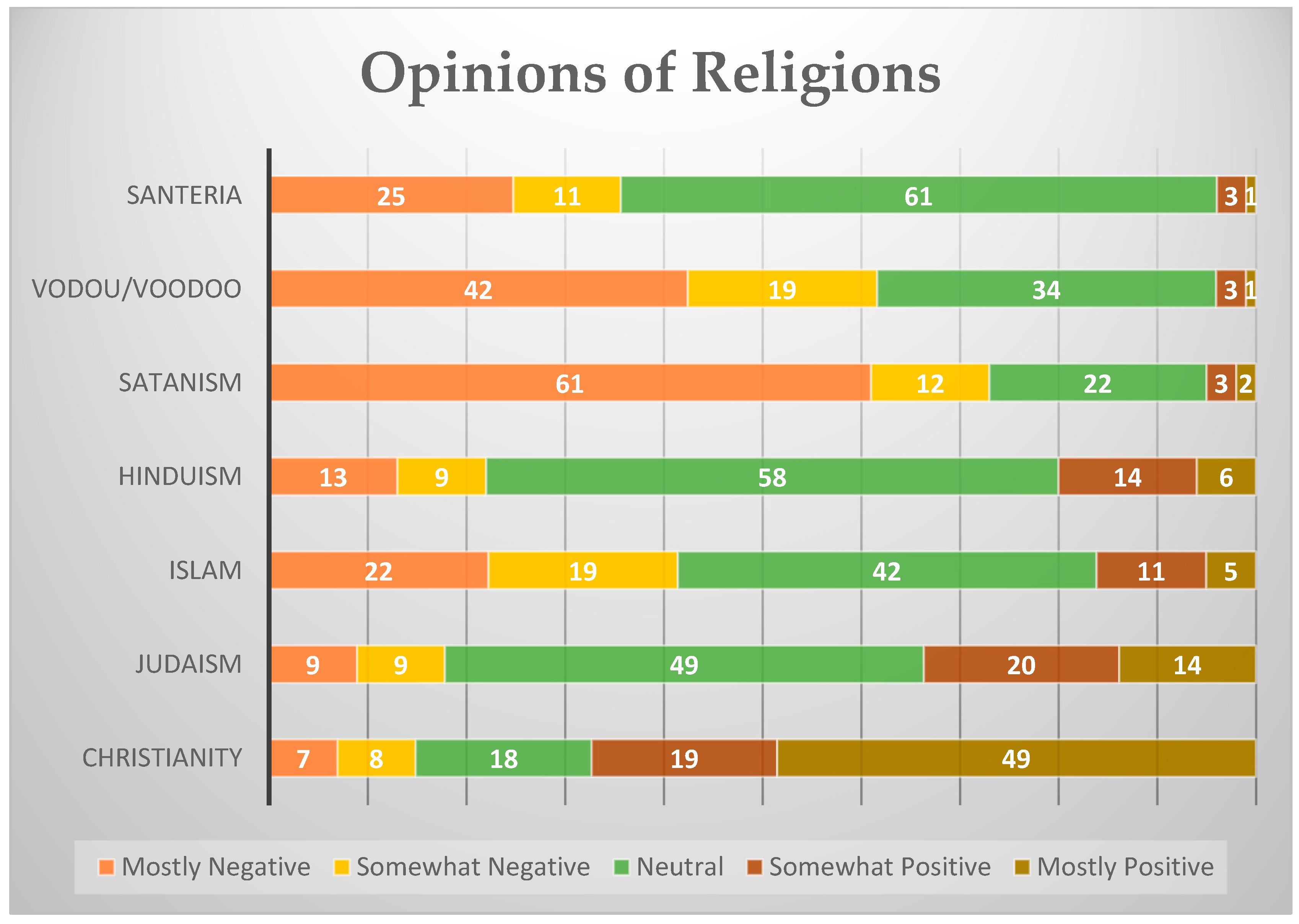

Only 4% of respondents described their opinion of Santeria or Vodou/Voodoo as somewhat positive or mostly positive. This was fewer than any other religion, including Satanism, which 5% viewed in a somewhat or mostly positive light. Far more people reported positive views of Islam (16%), Hinduism (20%), and Judaism (34%). The highest number of respondents (68%) viewed Christianity in a somewhat or mostly positive way.

Not only did remarkably few respondents report positive views of Santeria or Vodou/Voodoo, but significant percentages described negative views of these religions. More than one-third (36%) described their opinion of Santeria as somewhat or mostly negative. Additionally, an astonishing 61% of respondents reported that their opinions of Vodou/Voodoo were somewhat or mostly negative. The only religion with higher percentages in these categories was Satanism, with 73% reporting negative opinions about it.

It is also important to note that a large percentage of respondents reported neutral opinions about Vodou/Voodoo (34%) and Santeria (61%). In fact, more respondents had a neutral opinion about Santeria than any other religion included in the survey. As I will explore in the analysis of other survey questions, these neutral opinions may relate to respondents’ self-described lack of knowledge about these faiths.

In the sections that follow, I will examine some of the other survey findings that provide some nuance to these overall negative, neutral, and positive opinions. I will begin by discussing the questions that make the most important interventions in the scholarly research about African diaspora religions. Then, I will explore some of the other survey responses that might help explain public opinions of African diaspora religions.

4.1. Categorizing Religions

African diaspora religions like Santeria, Vodou, and Voodoo have a long history of persecution in the Americas. For instance, in New Orleans, news reports from the mid-nineteenth century indicated that practitioners of “voodoo” were arrested on at least several occasions for “unlawful assembly” (

Boaz 2023). Later, in the early 20th century, “voodoo” practitioners were arrested for fraud for selling ritual objects through the mail (

Roberts 2015).

Vodou was persecuted during multiple periods in the history of Haiti. For example, during the colonial period, enslaved people were prohibited from engaging in certain ritual practices because those practices were used in acts of rebellion against slavery (

Hebblethwaite 2021;

Paton 2012;

Ramsey 2011). Additionally, during the U.S. occupation (1915–1934), marines used antiquated criminal laws to disrupt Vodou ceremonies and arrest practitioners (

Ramsey 2011).

Particularly in the 20th century, persecutions of African diaspora religions were typically based on a notion that these religions were barbaric and threatened to morally corrupt American societies. Efforts to suppress these faiths were rooted in the racist assumptions that people of African descent did not have “religions” and that their “inferior” culture should be reined in by customs and cultural practices of European origin. Most of the official policies and laws that restricted African diaspora religions have been repealed; however, in some cases, this persecution lasted for more than a century. This section seeks to explore whether public opinions in the 21st century remain marked by this long history of considering African diaspora religions as less than religions.

4.1.1. Considered a Religion

One of the survey questions that explored these issues stated the following: “I consider ___ to be a religion.” (

Figure 2). In all three surveys, 16–19% of respondents considered Santeria to be a religion. Slightly more (17–23%) considered Vodou/Voodoo to be a religion. Vodou/Voodoo and Santeria were less likely to be considered a religion than any of the other belief systems included in the answer bank. Perhaps most strikingly, in the April 2024 and December 2024 surveys, Satanism was added to the possible answer choices. Slightly more respondents (21–23%) considered Satanism to be a religion than Vodou/Voodoo (17–21%) or Santeria (16–19%) on these surveys. By contrast, in each survey, 48–65% considered Islam, Judaism, and Hinduism to be religions. More than 80% of respondents considered Christianity to be a religion.

As stand-alone responses, this data is difficult to interpret. It may indicate negative views about African diaspora religions—that they are perceived as too primitive or barbaric to be religions. This would be consistent with the longstanding views of African diaspora religions. However, the responses could also indicate that respondents regard Santeria and Vodou/Voodoo as something other than, but not necessarily less than, religions.

Many people have debated whether African diaspora religions are more properly categorized as “cultural practices” than “religions”. Even some devotees balk at the use of the word “religion” to describe their faith (

Ramsey 2013). Some of them view religion as a restrictive term that implies a certain kind of bureaucracy that does not reflect the role that their faith plays in every aspect of their daily lives. They might prefer terms like “spirituality”, “faith”, or “way of life”.

4.1.2. Should Be Protected

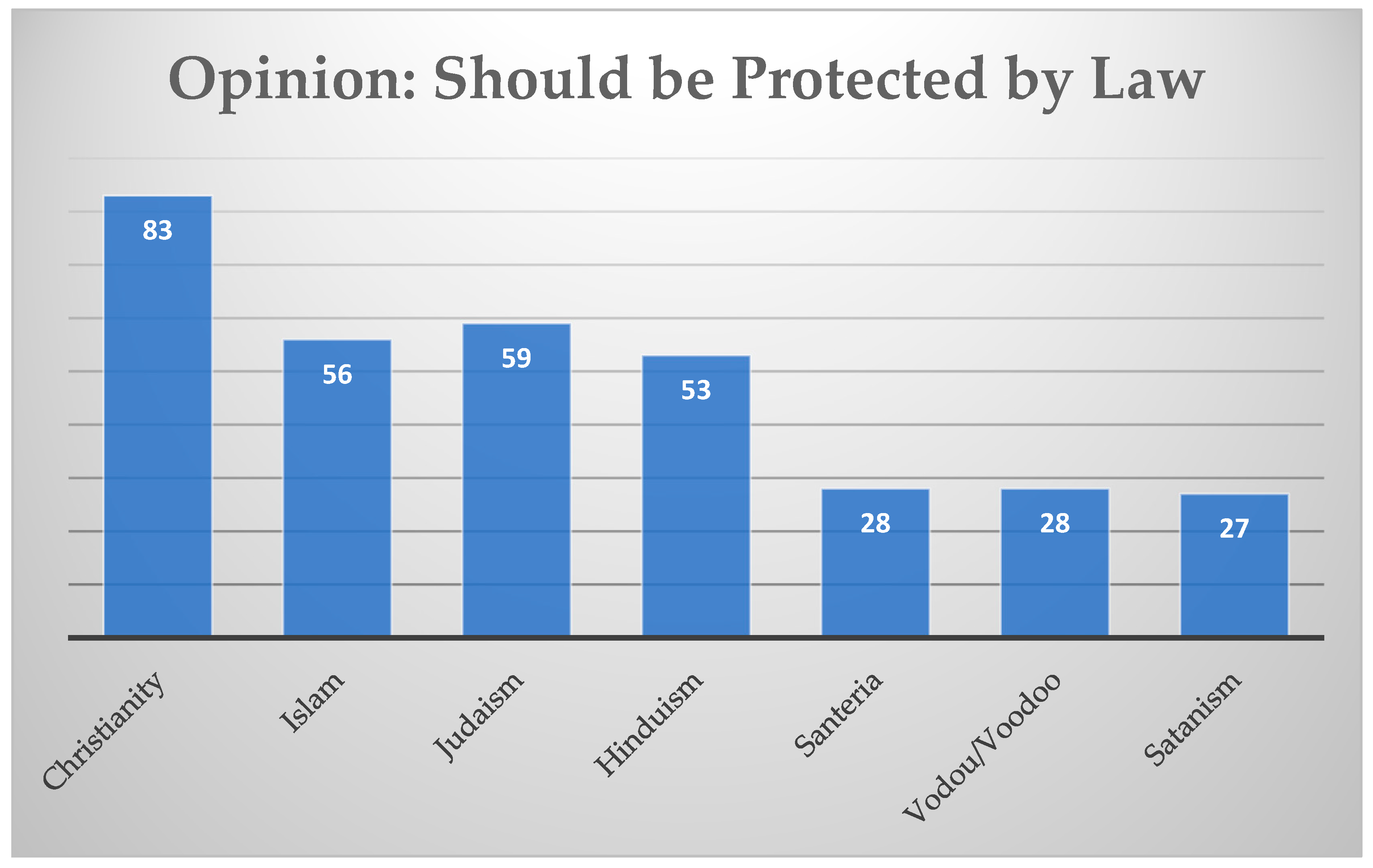

The next question in the December 2024 survey further complicates these responses. It stated, “I believe that ____ should be protected by policies or laws guaranteeing freedom of religion and belief.” (

Figure 3). Once again, respondents were instructed to select religions from the answer bank that they felt were applicable. Although only around one-fifth of respondents believed that Santeria and Vodou/Voodoo were religions, more than one-fourth believed that these faiths should be protected by law. Paradoxically, for most of the other listed faiths, one can see the opposite trend. More respondents viewed Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Hinduism as religions than believed that they should be protected by law.

These responses show a clearer trend if we filter out the 6% of respondents who listed “none of the above” when asked which of listed faiths they considered to be a religion and the 13% who answered “none of the above” when asked which of the listed faiths should be protected by law. Omitting these responses is helpful because these respondents may be expressing discomfort with the category “religion” or with laws and policies related to religious freedom rather than specific views about the listed religions.

Without these respondents, the percentages of people who believed that Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, and Christianity should be protected by laws and policies closely mirrored, but were slightly less than, those who considered these faiths to be religions (

Figure 4). This supports the idea that some respondents were uncomfortable with laws and policies related to religious freedom even though they would categorize these faiths as “religions”. However, without the “none of the above” responses, we see an even more marked increase from the one-fifth of respondents who believed that Santeria and Vodou/Voodoo were religions to the nearly one-third who thought that they should be protected. The same trend can be observed with Satanism, albeit a less drastic increase. This seems to suggest that most respondents see the category of “religion” somewhat narrowly, in a way that excludes African diaspora religions. Nevertheless, some of these respondents believe that even African diaspora religions deserve to be protected by law.

4.1.3. Conclusions About Categorizing Religions

I will revisit these responses in relationship to other survey questions in later sections. However, as stand-alone data, these survey responses suggest important things about public perceptions of African diaspora religions. Following many decades of the denigration of Vodou, Voodoo, and Santeria as less than religions, public opinion seems to mirror these longstanding stereotypes. While a higher percentage of respondents believed that African diaspora religions should protected by laws and policies guaranteeing freedom of religion and belief, these figures were still low—a little more than one-fourth of all respondents. Views of Santeria and Vodou/Voodoo in this category are similar to one another, roughly analogous to perceptions of Satanism, and far less favorable than the other religions included in the survey.

4.2. Family and Children

The surveys also contained several questions that explored respondents’ views of the listed religions in relationship to families and children. These questions were motivated by several factors. First, research has shown that arguments about perceived harm to children have often been used to try to justify discrimination against African diaspora religions in the Americas. For instance, when the City of Hialeah court case about Santeria was heard by the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida, proponents of the animal sacrifice bans argued that children would be harmed if they witnessed a ritual involving the death of an animal (

Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye, Inc., v. City of Hialeah. 723 F. Supp. 1467 1989). The District Court ruled in favor of the animal sacrifice bans, observing, in part, that the ordinances would help protect children.

The second motivation for these questions is that Brazil has seen a recent surge in legal cases where family members have tried to remove a child from a parent’s custody based solely on the fact that the parent practices an Afro-Brazilian religion. They have argued that these religions have a negative impact on a child—sometimes asserting that the religions are generally harmful and sometimes alleging that particular practices, like shaving the child’s head for initiation, are damaging (

Boaz 2021;

Cruz and Tatsch 2021). I am only familiar with a couple of court cases like this in the United States (i.e.,

New Jersey Division of Youth and Family Services v. Y.C. 2011). However, several devotees of African diaspora religions in the U.S. have reported more cases to me during informal conversations. Therefore, these survey questions are designed to provide some insights as to whether it is common for adults in the United States to believe that affiliation with an African diaspora religion should impact a person’s relationship with their family or their interactions with children.

4.2.1. Family Members

One of the first questions in this area was featured only on the December 2024 survey. It stated, “I would be comfortable with a member of my immediate family practicing _______.” The vast majority of respondents, 84%, were comfortable with a family member practicing Christianity. Less than half were comfortable with Judaism (44%), and around one-third with Islam (33%) and Hinduism (35%). By contrast, only 13% were comfortable with an immediate family member being a follower of Santeria and 14% with one being a devotee of Vodou/Voodoo. Respondents were slightly less comfortable with a family member being a follower of Satanism (11%).

These responses are informative when compared to answers to other survey questions. For instance, one will recall that around 30% of respondents believed that Santeria and Vodou/Voodoo should be protected by law. Nevertheless, fewer than 15% would be comfortable with followers of these religions in their immediate household. This implies a willingness to protect the rights of devotees of these religions in theory but a desire to avoid familial connections with them.

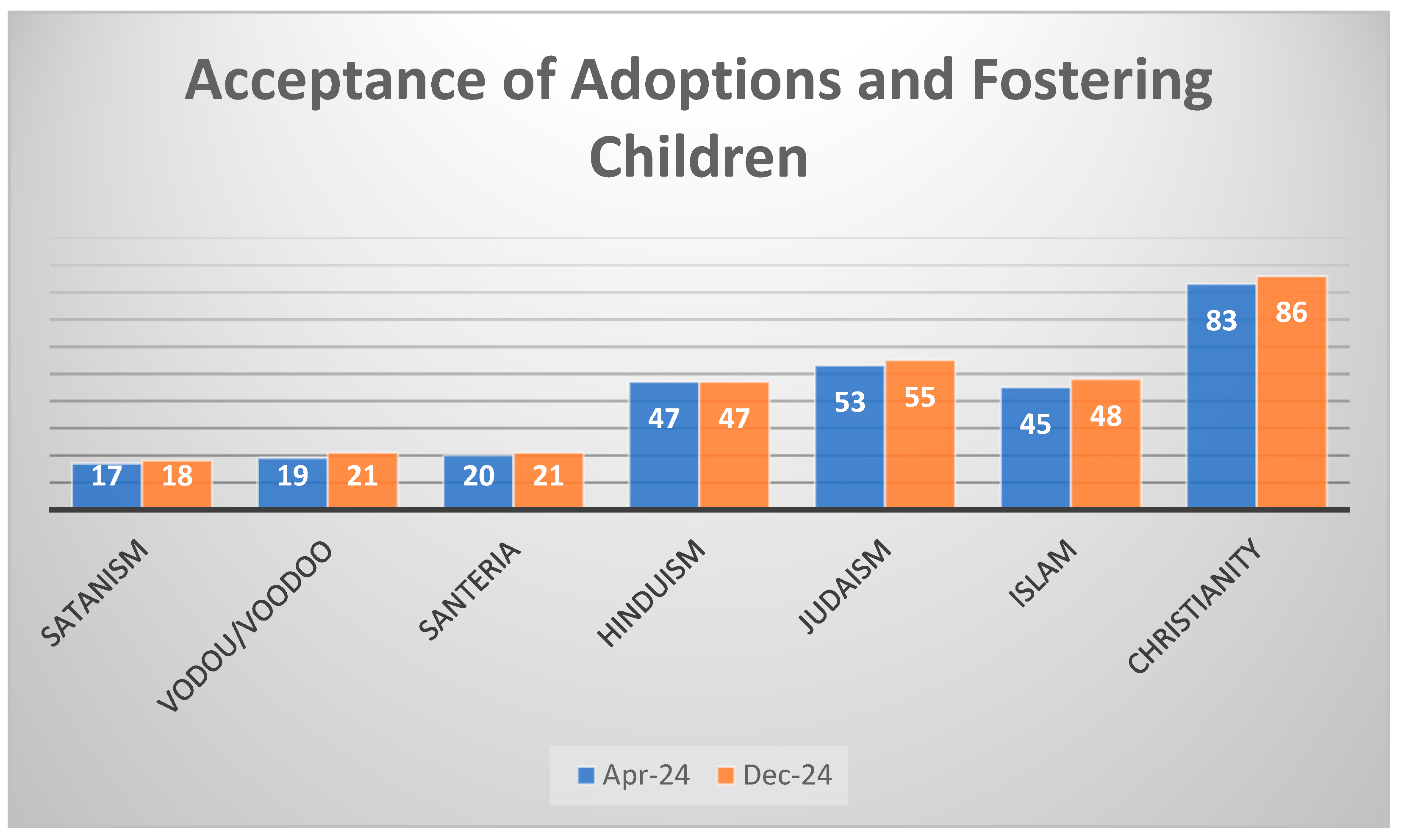

On the April 2024 and December 2024 surveys, a related question asked if respondents believe that followers of the listed religions (Santeria, Vodou/Voodoo, Hinduism, Judaism, Islam, Christianity, and Satanism) should be permitted to foster and/or adopt children (

Figure 5). Only approximately one in five respondents believed that devotees of Santeria or Vodou/Voodoo should be permitted to foster or adopt children. Around half were comfortable with followers of Islam (45–48%), Judaism (53–55%), and Hinduism (47%) adopting or fostering. The vast majority, 83–86%, were comfortable with Christians doing so.

The responses to this question likewise suggest broader comfort with the rights of devotees in theory but discomfort with these faiths in the respondents’ immediate vicinity. For instance, 81% of those who were accepting of Vodou/Voodoo followers adopting or fostering children also believed that devotees should be protected by laws or policies guaranteeing freedom of religion and belief. Similarly, 79% of respondents who agreed that Santeria devotees should be able to adopt or foster children believed that Santeria should be protected by law. By contrast, only 53% of respondents who agreed that devotees of Vodou/Voodoo should be able to adopt or foster children indicated that they would be comfortable with an immediate family member practicing Vodou/Voodoo. Likewise, only 50% of the respondents who were accepting of followers of Santeria adopting or fostering children were comfortable with having a devotee of Santeria in their immediate family.

4.2.2. Child Education

All three surveys asked respondents if they would feel comfortable with their child being educated about any of the listed religions (

Figure 6). On average, around one-fifth of respondents said that they would feel comfortable with their child being educated about Santeria (14–22%), Vodou/Voodoo (15–24%), and Satanism (15–22%). Respondents were around twice as likely to feel comfortable with their children being educated about Islam (34–41%), Judaism (40–47%), or Hinduism (34–39%). The majority felt comfortable with their child being educated about Christianity (76–84%).

Perhaps not surprisingly, responses to this question varied dramatically among those who regarded Santeria and Vodou/Voodoo as religions. Of those who did not consider Santeria to be a religion, only 7–14% felt comfortable with their children being educated about it. However, 57–62% of respondents who viewed it as a religion found it to be an acceptable educational topic. The data on Vodou/Voodoo was very similar; only 7–14% of those who did not consider it a religion felt comfortable with their children being educated about it. By contrast, 55–62% of those that viewed it as a religion were okay with their children learning about Vodou/Voodoo.

The relationship between views about child education and other survey questions were somewhat less intuitive. For example, fewer than half of the respondents who were comfortable with their child being educated about African diaspora religions were also comfortable with an immediate family member practicing it (46% Santeria; 47% Vodou). This, once again, suggests that while some respondents are broadly accepting of the recognition of African diaspora religions and supportive of the rights of devotees, they remain uncomfortable with direct interactions or relationships with adherents.

4.2.3. After-School Programs

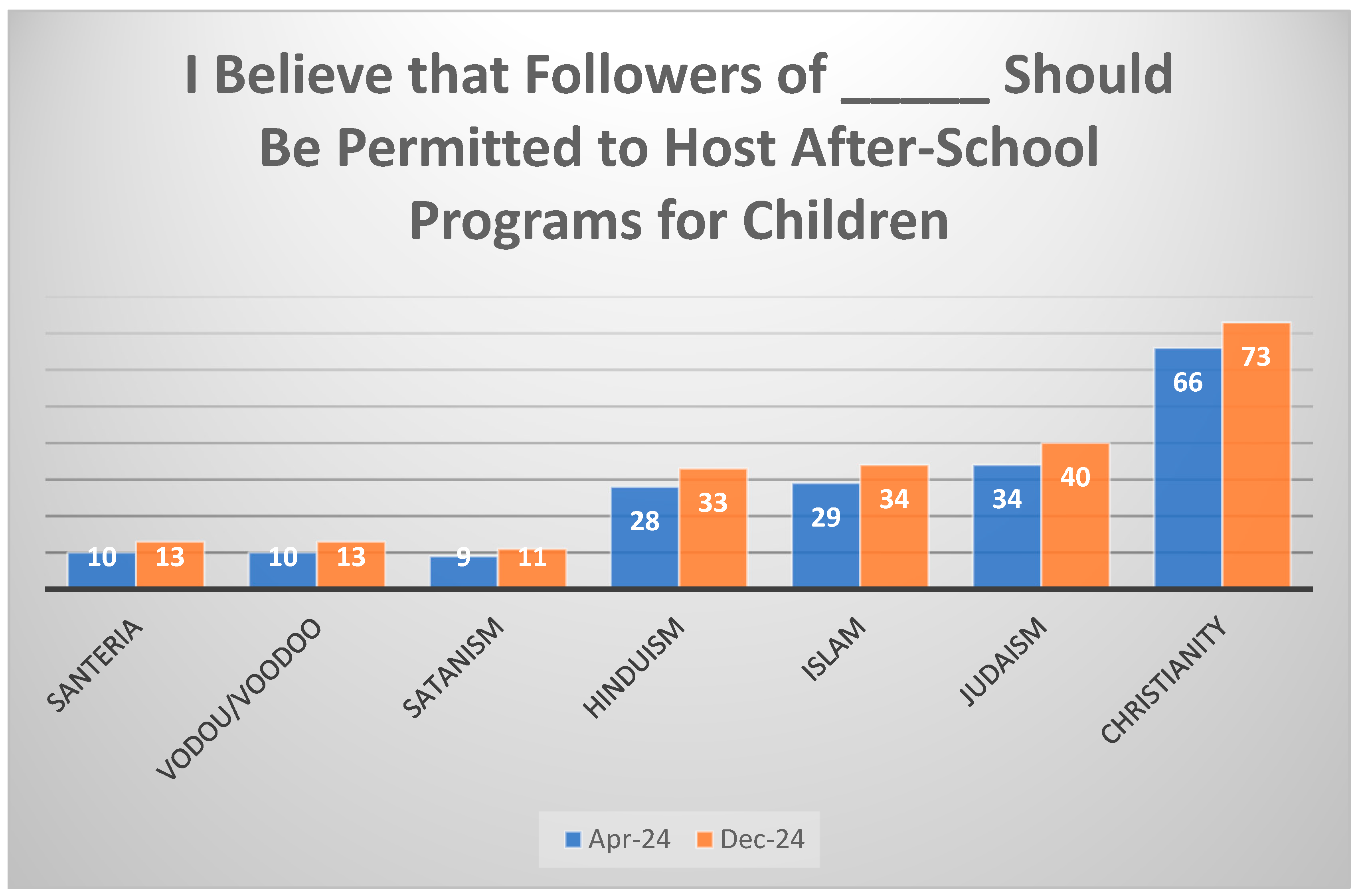

Another survey question explored respondents’ attitudes toward children being exposed to different religions in an educational setting. This question was motivated by recent reports that the Satanic Temple has founded after-school programs for children in the United States. According to journalists, there has been a significant public outcry about such programs (

Stewart 2016). This survey question was designed to investigate public opinions about religious groups hosting such programs and compare views of African diaspora religious groups versus Satanists.

As with other survey questions, views about followers of Santeria, Vodou/Voodoo, and Satanism hosting after-school programs for children were very similar (

Figure 7). Only 9–13% of respondents were comfortable with these religious groups hosting such programs. By contrast, 28–40% were okay with Jewish, Muslim, or Hindu programs. More than two-thirds were okay with Christian after-school programs.

4.2.4. Conclusions About Family and Children

The responses to the questions discussed in this section show some significant biases against African diaspora religions regarding their relationship with children and families. On average, one-fifth of respondents or fewer were comfortable with children being exposed to these religions through after-school programs, education, or custodial processes like fostering or adopting. Even those who were accepting of devotees of African diaspora religions having such interactions with children were often reluctant to have devotees within their own families.

4.3. Exploring Common Stereotypes

The surveys included several questions that were designed to explore what are viewed as common stereotypes about African diaspora religions. These questions centered on three stereotypes: that devotees practice black magic or witchcraft, that adherents worship the devil or demons, and that these religions are frequently linked to crime, especially drug trafficking.

4.3.1. Black Magic, Witchcraft, and Devil Worship

There is a rich body of research that explores the history of devotees of African diaspora religions being accused of black magic, sorcery, or witchcraft (i.e.,

Murphy 1990;

Ramsey 2011;

Parés and Sansi 2011;

Paton 2012). These stereotypes date back hundreds of years and were common throughout much of the Americas. As mentioned in the introduction, starting around the late nineteenth century, devotees were accused of committing atrocities like human sacrifice and cannibalism in their religious rituals (

Helg 2000;

Roman 2007). U.S. newspapers recounted these sensational tales, particularly when referring to places like Cuba and Haiti where the U.S. had imperial interests (

Boaz 2023). Popular culture references to these religions have often reinforced this sinister imagery, linking African diaspora religions with Satanism (

McGee 2012).

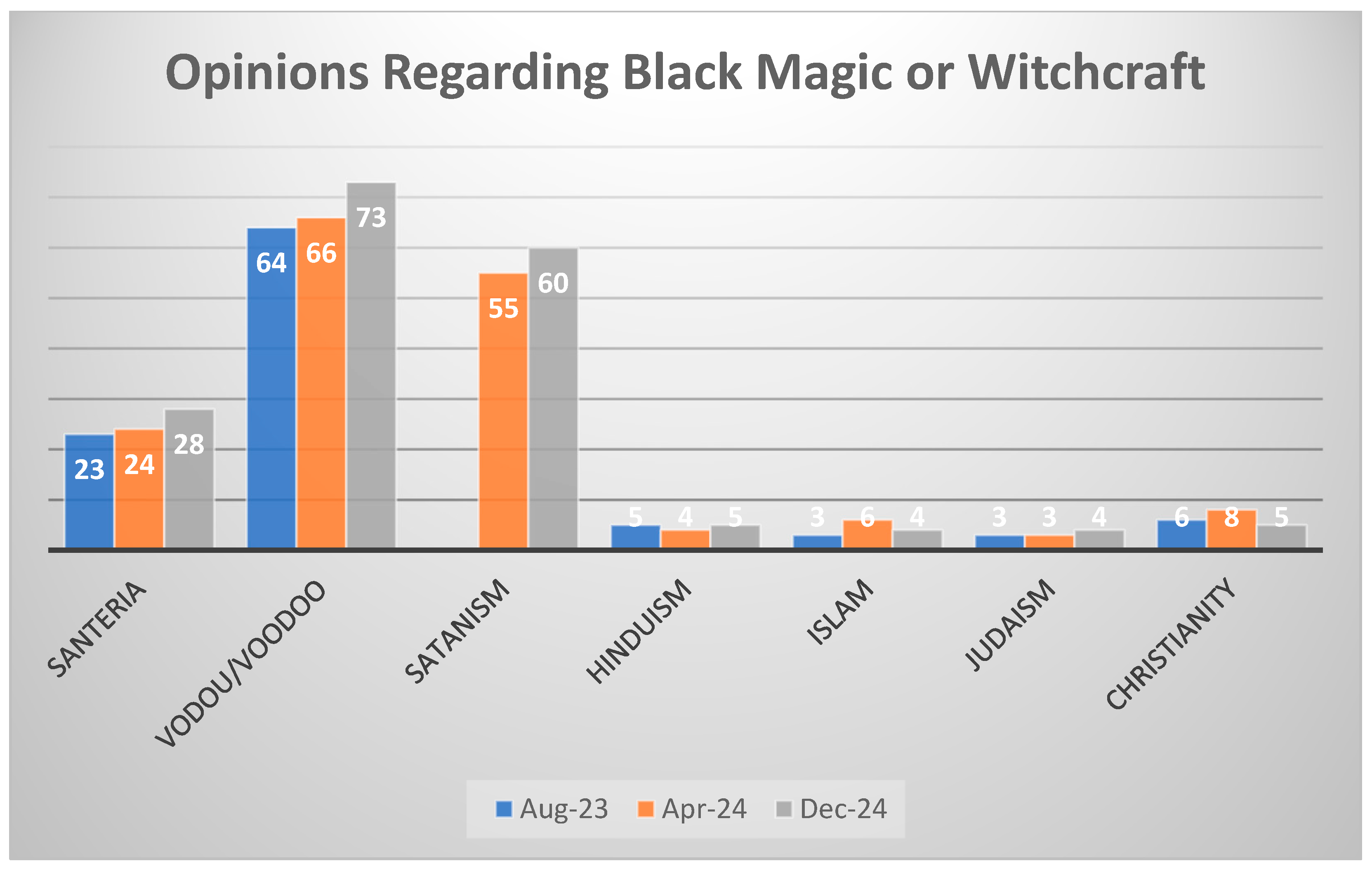

Because of this history, all three surveys asked respondents whether they believed that followers of any of the listed religions were more likely to practice black magic or witchcraft than the average person. The survey responses suggest that these longstanding stereotypes about African diaspora religions continue to be pervasive (

Figure 8). Approximately one-fourth of respondents believed that followers of Santeria were more likely to practice black magic or witchcraft than the average person. An astonishing two-thirds of respondents (64–73%) believed that followers of Vodou/Voodoo were more likely to practice black magic or witchcraft than the average person. This was higher than even Satanism, which 55–60% of respondents selected. By contrast, fewer than 10% of respondents believed that followers of Christianity (5–8%), Islam (3–6%), Judaism (3–4%), or Hinduism (4–5%) were more likely to practice witchcraft or black magic than the average person.

In the December 2024 survey, I added the following statement: “I believe that followers of ____ worship the devil and/or demons” (

Figure 9). A mere 5% or fewer selected Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, or Christianity. However, 15% of respondents selected Santeria and 36% Vodou/Voodoo. Perhaps not surprisingly, most respondents (77%) selected Satanism.

As mentioned in the introduction, the assumption that devotees of African diaspora religions worship the devil or demons is ironic, to say the least, because this argument is based on Protestant Christian worldviews, not those of African diaspora religions (

Lowe 2023). As Benjamin Hebblethwaite explains in his study of the claims that Vodou caused the 2010 earthquake by being “satanic” and “progress-resistant”, “figures of ’Satan’ or ‘demons’ are not anchored as the diametrical foes of God in the religion’s mythology in the way they are in Christianity” (

Hebblethwaite 2015, p. 5).

4.3.2. Crime

I previously noted that African diaspora religions have been stereotyped as deeply connected to drug trafficking gangs. This was particularly true in the 1980s, when the state of Florida experienced a surge in drug trafficking cases and related violence. Immigrants were frequently blamed for the rise in drug use, trafficking, and crime.

Stereotypes about a close relationship between African diaspora religions and drug trafficking surged in 1989, following the highly publicized murder of a college student from the University of Texas, Mark Kilroy, while he was on spring break in Matamoros, Mexico. Authorities discovered Kilroy’s body at a gruesome site among numerous dismembered corpses and a cauldron with blood, organs, and a human brain (

Gomez 2005). The victims had been killed by members of a drug trafficking gang, the Cartel de Golfo. Some of the cartel members who were arrested for the murders claimed that other members who were Santeria priests had offered Kilroy and the other victims as human sacrifices to bring the cartel “good luck and protection in their drug trade” (

Gomez 2005, p. 12). Around a month after the bodies were found, an anthropologist was called to the scene, and he opined that the cartel members were practicing a different Afro-Cuban religion: Palo Mayombe. Later, it was discovered that the perpetrators had been imitating a horror movie,

The Believers, and they had little-to-no real connections to Afro-Cuban religious communities (

Bartkowski 1998). Nevertheless, these stereotypes persisted (

Cros Sandoval 2006).

Since the murders, numerous articles and books about the Matamoros killings have continued to link them to Afro-Cuban religions (i.e.,

Schutze 1989). Furthermore, in the 21st century, criminologists and forensic anthropologists have taught seminars to police departments and have written books claiming that devotees of African diaspora religions are likely to be linked to organized criminal networks, especially drug trafficking (i.e.,

Holmes and Holmes 2009;

Kail 2015). They assert that these religions are immoral or amoral and are used frequently to protect adherents from arrest. It seems highly likely that such stereotypes were widely held among the U.S. public in the 1980s and 1990s. Therefore, through these surveys, I sought to explore if such misconceptions continue to be common.

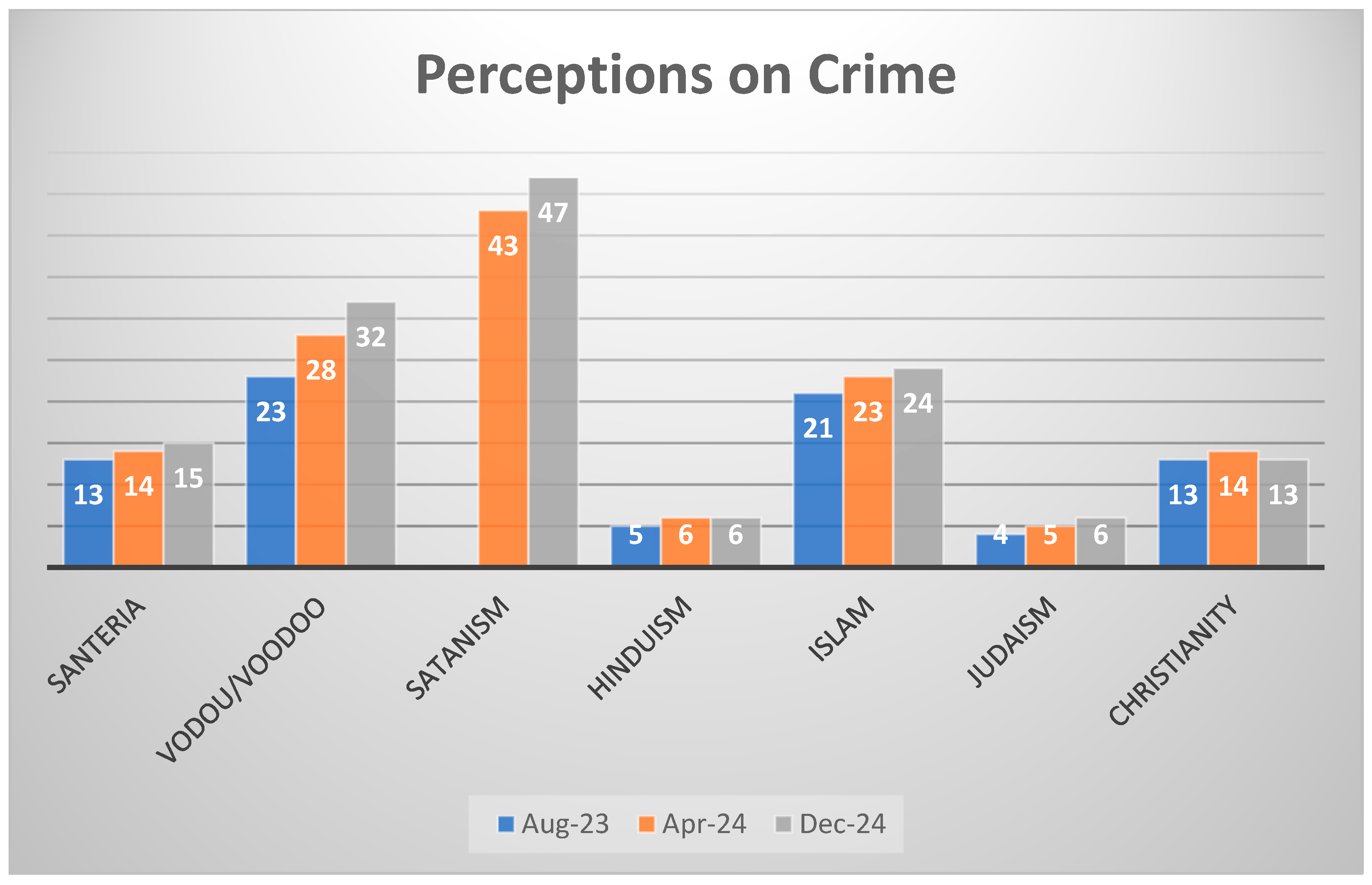

All three surveys contained the following statement: “I believe that followers of _______ are more likely to be involved in crime/criminal activity than the average person.” As with the previous questions, respondents were given an answer bank with six religions in 2023 and seven in April and December 2024 and were instructed to “select all that apply” (

Figure 10). Hinduism and Judaism were selected by only 4–6% of respondents. Respondents viewed Santeria similarly to Christianity, with 13–15% selecting the former and 13–14% selecting the latter. In the first survey, the responses for Islam (21%) and Vodou/Voodoo (23%) were similar. However, in the 2024 surveys, the percentage of respondents who selected Islam only slightly increased while those who selected Vodou/Voodoo grew to 28% (April) and 32% (December). Satanism was the most common answer choice, with 43–47% selecting this religion.

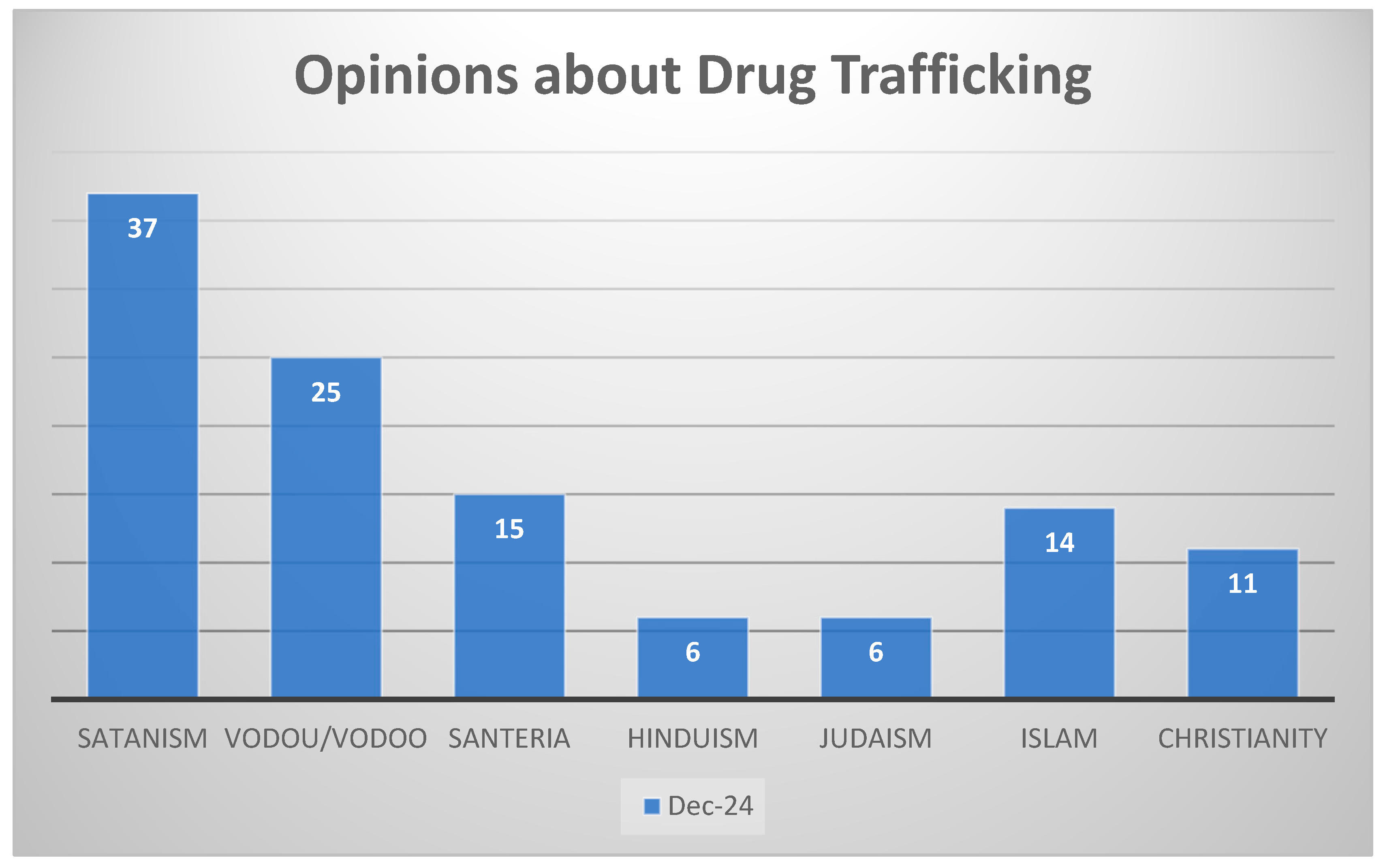

The December 2024 survey delved deeper into this topic, asking if respondents believed that followers of any of the listed religions were more likely to be involved in drug trafficking than the average person (

Figure 11). Given the history just described, the responses were surprising. Nearly half of respondents, 46%, selected none of the above. Once again, among those who did believe that religion was linked to drug trafficking, views of Santeria were remarkably similar to those of other religions. Between 11–15% believed that followers of Christianity, Islam, and Santeria were more likely than average to be involved in drug trafficking. A much larger portion, 25%, viewed followers of Vodou/Voodoo as more likely to be linked to drug trafficking. Only Satanists were thought to have a closer relationship to drug traffickers than Vodou/Voodoo practitioners; more than one-third of respondents selected Satanism.

Given the prevalence of negative representations of Vodou/Voodoo in TV shows and movies (mentioned in the introduction), the idea that it might be linked to crime is expected. However, it is somewhat surprising that respondents associated drug trafficking with Vodou/Voodoo more frequently than Santeria. After all, Afro-Cuban religions were blamed for both the Matamoros incident and the rise in drug trafficking and related violence in South Florida in the late 20th century. Nevertheless, based on these responses, stereotypes of Santeria as linked to drug trafficking and other crime may have diminished in the general population even though it remains a popular assertion in police training manuals and criminology publications. It is possible that these responses are associated with an overall lack of knowledge about Santeria, which I will discuss further in the next section. However, this disparity is worth exploring in future surveys and examining through other research.

It is also important to reflect further on the fact that one-fourth of respondents linked Vodou/Voodoo to drug trafficking and to understand the negative impact of these stereotypes. It should be no surprise that respondents who viewed devotees as likely to be involved in drug trafficking expressed discomfort with adherents engaging with members of their family or being involved with children. Among these respondents, the percentage who felt comfortable with a member of their immediate family practicing Vodou/Voodoo fell from 14% to 3%. The percentage who believed that followers of Vodou/Voodoo should be able to host after-school programs for children declined from 13% to 4%. Those who believed that Vodou/Voodoo devotees should be permitted to foster or adopt children decreased from 21% to 7%.

4.3.3. Conclusions About Common Stereotypes

These surveys indicate that some of the stereotypes that have been common about African diaspora religions persist to varying degrees in the 2020s. Assumptions that devotees are involved in crime remain common for Vodou/Voodoo, while the specific links drawn between Santeria and crime, including drug trafficking, appear to have waned since the late 20th century. Respondents were more likely to associate both Santeria and Vodou/Voodoo with devil worship, black magic, and witchcraft than most other religions; however, such stereotypes about Vodou/Voodoo were far more pervasive than with Santeria.

It is important to note the relationship between the responses to these four questions. For example, 97% of those who believed that followers of Vodou/Voodoo were more likely to be involved in drug trafficking also believed that devotees were more likely to practice witchcraft or black magic, and 71% of these respondents thought that devotees worship the devil/demons. These are increases from 73% of all respondents who believed that devotees of Vodou/Voodoo were more likely to practice witchcraft or black magic and 36% of all respondents who thought that devotees worship the devil/demons.

Similarly, among respondents who believed that followers of Santeria were more likely than average to be involved in drug trafficking, the percentage who also believed that devotees were more likely than average to practice witchcraft or black magic increased drastically from 28% to 72%, and the percentage who thought that devotees worship the devil/demons more than tripled from 15% to 53%. These figures suggest that people who believe one stereotype about African diaspora religions are significantly more likely to also accept other misconceptions.

4.4. Knowledge About African Diaspora Religions

In addition to exploring what stereotypes about African diaspora religions might continue to be pervasive and interrogating whether overall views of these religions are positive or negative, one of the goals of these surveys was to determine how knowledgeable people are about African diaspora religions and where the respondents obtained their information. The December 2024 survey contained three questions that explored these topics.

Respondents were asked “On a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 representing no knowledge and 10 representing very knowledgeable, how knowledgeable are you about the following?” They reported the least knowledge about Santeria out of the seven religions in the answer bank. Around two-thirds of respondents ranked their knowledge of Santeria as “1” out of 10. Respondents were more familiar with Vodou/Voodoo than Santeria; however, 42% of respondents still rated their knowledge of Vodou/Voodoo as “1”, signifying “no knowledge”. This was similar to Satanism; 40% described themselves as having no knowledge of this religion. Around one-fourth reported no knowledge of Islam and Judaism. A mere 3% of respondents indicated that they had no knowledge of Christianity—a figure that is not surprising given the prevalence of Christianity in the United States.

If we break down the numbers into groupings of “little knowledge” (1–3), “moderate knowledge” (4–6), and “very knowledgeable” (7–10), the responses suggest an even more striking lack of familiarity with African diaspora religions. Based on these categories, a whopping 86% of respondents reported little knowledge of Santeria. Respondents were slightly more familiar with Vodou/Voodoo; however, roughly three-fourths of respondents reported little knowledge of this religion. By comparison, 69% reported little knowledge of Satanism and Hinduism; around half reported little knowledge of Judaism and Islam. Only 7% considered themselves to possess little knowledge of Christianity.

Along similar lines, only 5% of respondents considered themselves to be very knowledgeable about Santeria. The percentage of respondents who considered themselves to be very knowledgeable about Vodou/Voodoo (8%) was similar to Hinduism (8%) and Satanism (9%). Twice as many considered themselves very knowledgeable about Islam (16%), and even more reported being very knowledgeable about Judaism (22%). Unsurprisingly, 75% ranked themselves as very knowledgeable about Christianity.

While this information is important, a cross-data analysis of the December 2024 survey responses suggests something even more intriguing—that knowledge of Santeria and Vodou/Voodoo did not always greatly improve views of them. For example, among the few respondents who considered themselves very knowledgeable about Santeria, only 15% were comfortable with a member of their immediate family being a follower of Santeria. This is marginally more than the 13% of all respondents who were comfortable with it. There was a slightly larger difference with Vodou/Voodoo. One will recall that 14% of all respondents felt comfortable with an immediate family member practicing Vodou/Voodoo. Among people who ranked themselves as very knowledgeable about Vodou/Voodoo, this percentage rose to 19%. Similarly, the percentage of respondents who were comfortable with their child being educated about Santeria and Vodou/Voodoo rose from 22% to 28% and 24% to 29%, respectively, among those who considered themselves very familiar with these religions. The number of people who were comfortable with devotees of Santeria and Vodou/Voodoo hosting after-school programs for children only increased from 13% to 17% among those who considered themselves very knowledgeable about Santeria. It did not increase at all among those very knowledgeable about Vodou/Voodoo.

The survey also suggests that having little-to-no knowledge of African diaspora religions did not prevent a significant portion of the respondents from forming biases against them. In fact, of the 1732 people who reported that they had no knowledge of Santeria (ranked their knowledge level as 1 out of 10), 24% still described their opinion of it as “mostly negative”. Similarly, of the 1028 people who reported that they had no knowledge of Vodou/Voodoo, more than half (53%) described their opinion as mostly negative. One can contrast this with Hinduism. Of the 872 people who described having little knowledge of Hinduism, only 18% viewed the religion as “mostly negative”.

4.4.1. Sources of Information

In addition to exploring how knowledgeable respondents were about African diaspora religions, the December 2024 survey also sought to determine where respondents obtained their information about these faiths. Therefore, the survey also included the following statement: “My views about Santeria are based on what I learned from:” (

Figure 12). Respondents were given an answer bank of six sources of information. They were instructed to “select all that apply”. Alternatively, they had the option to select “I know nothing”.

Similar to the earlier question that asked respondents to rank their knowledge of twelve religions, 64% of respondents indicated “I know nothing”. Of those who reported sources of information, TV/movies was the most common answer (18%), followed closely by the Internet/social media (17%). Eight percent reported that their views were based on news reports. Only 5% of respondents reported that they learned of Santeria from school/university or from practitioners. Five percent also reported that they learned of Santeria from other sources. These sources varied; however, the most common were family members, friends, books, and a Sublime song.

Because so many people responded “I know nothing”, removing these answers can help us gain a better understanding of where respondents who have some knowledge of Santeria are learning about it. Among these remaining respondents, around half indicated that they learned about Santeria from TV/movies (50%) and/or the Internet/social media (46%), while 21% listed news reports. Between 14 and 15% listed school/university, practitioners, and/or “other”.

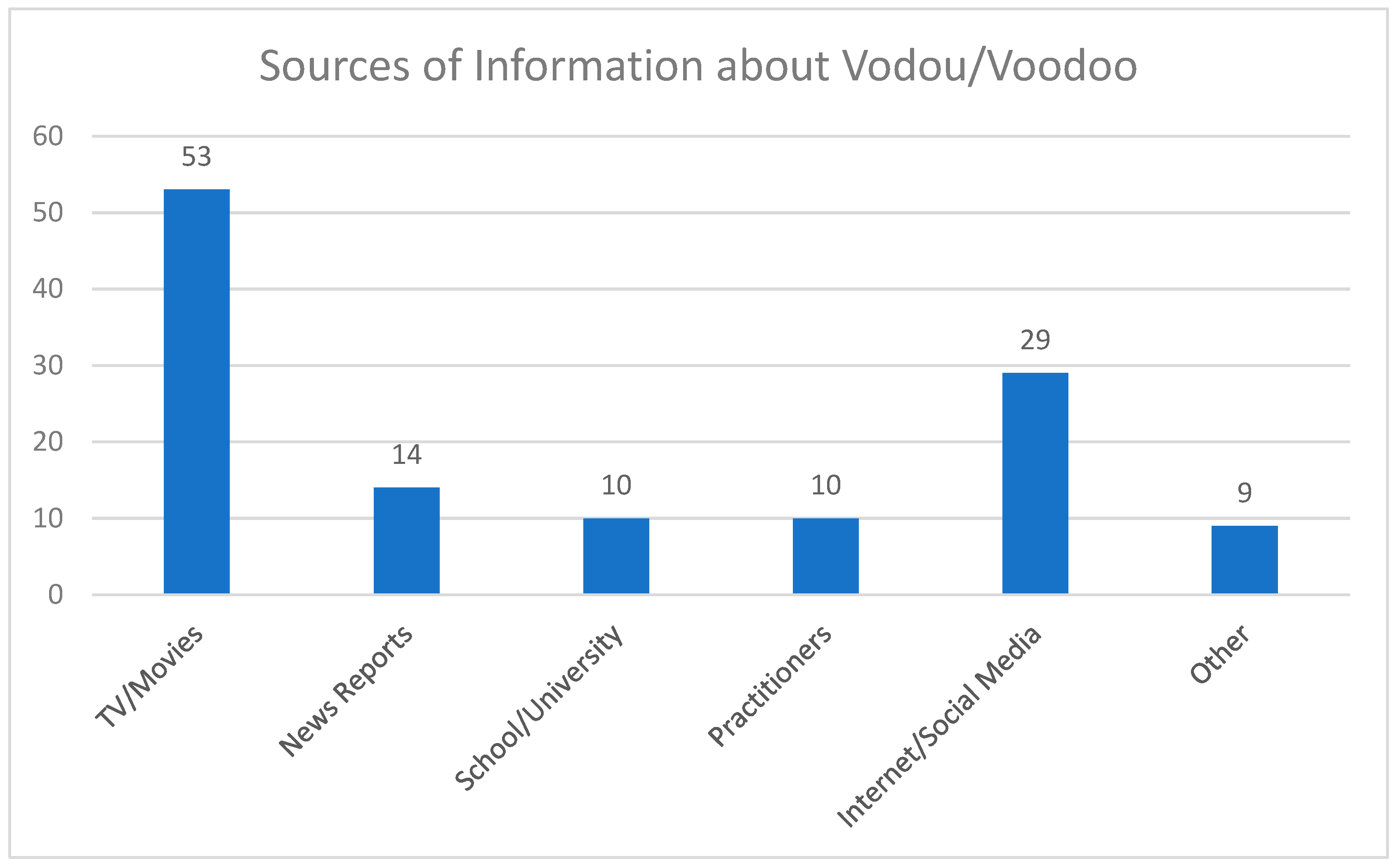

An identical question about Vodou/Voodoo was included in the December 2024 survey (

Figure 13). One significant difference between the responses to these questions is that much fewer respondents indicated that they know nothing about Vodou/Voodoo (25%) compared to Santeria (64%). However, other aspects of the responses were similar. As with Santeria, TV/movies was the primary source of information. Substantially more respondents (53%) selected this answer for Vodou/Voodoo than Santeria. However, one must recall that when the “I know nothing” responses were removed from the Santeria question, 50% of respondents listed TV/movies.

The Internet/social media was, once again, the second-most popular response. Nearly one-third (29%) of respondents selected this as a source of information. School/university and practitioners were again the least common responses; 10% of respondents selected each of these as a source of information. Slightly more, 14%, selected news reports. Nine percent of respondents reported that they learned of Vodou/Voodoo from other sources. The common descriptions of these other sources were similar to those about Santeria: books, family members, and friends. Several people mentioned trips to Haiti or to Louisiana, especially New Orleans. A few also cited their pastor or the Bible as sources.

4.4.2. Comparing Knowledge and Sources

When I compare the relationship between the responses to the questions about knowledge of Santeria and Vodou/Voodoo to those about sources of information, there are some interesting results. One will recall that in the beginning of the survey, respondents were asked to rank their knowledge on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 representing no knowledge. Then, in this question about sources of information, they had the option to select “I know nothing”. Overall, similar percentages of respondents, around two-thirds, indicated that they had no information about Santeria in these questions. Indeed, more than 80% of those who ranked their knowledge of Santeria as 1 out of 10 responded “I know nothing” to the sources question.

Regarding Vodou/Voodoo, on the other hand, the responses to these questions differed significantly. One will recall that 42% ranked their knowledge as 1 out of 10, which they were told represented “no knowledge”. By contrast, only 25% of respondents selected “I know nothing” in response to this question. When we explore the relationship between these responses, we find that only 44% of those who had previously ranked their knowledge of Vodou/Voodoo as 1 out of 10 responded “I know nothing” to the question asking where they learned about it.

To better understand this disparity, I filtered the responses to view what persons who indicated that they had “no knowledge” of Vodou/Voodoo listed as their sources of information. Of the 584 respondents who listed their knowledge of Vodou/Voodoo as 1 out of 10 but did not respond “I know nothing” on this answer, 74% learned from TV/movies, 30% from the Internet/social media, 17% from news reports, 7% from practitioners, 8% from school/university, and 7% from “other” sources.

4.4.3. Negative Views

A comparison of the responses to the questions about sources of information against those asking about opinions and stereotypes of African diaspora religions can help explore the origins of negative views. For example, one will recall that the respondents were asked to describe their views of the listed religions as mostly positive, somewhat positive, neutral, somewhat negative, or mostly negative. Interestingly, nearly half (49%) of those whose opinion of Santeria was somewhat or mostly negative selected “I know nothing” when asked about the source for their knowledge. Those who expressed somewhat or mostly negative opinions about Vodou/Voodoo were less likely to respond “I know nothing” when asked about their source of information about it than when asked about Santeria. However, more than one-fifth (22%) still selected this response.

If one eliminates the respondents who answered “I know nothing” about Vodou/Voodoo and Santeria, three sources of information emerge as the most common among those who expressed negative opinions. The majority of these respondents reported learning about these African diaspora religions from TV/movies (53% Santeria; 75% Vodou/Voodoo) and around two-fifths (42% Santeria; 38% Vodou/Voodoo) listed the Internet/social media. News reports remained a significant source of information, with 25% using this source as a basis for their views about Santeria and 20% for Vodou/Voodoo.

As I mentioned in the introduction to African diaspora religions, there have been a plethora of movies and TV shows that have depicted these religions in a very discriminatory light. Scholars have opined that these depictions have had a strong negative impact on public opinions about African diaspora religions. After referring to “voodoo” as “principally an invention of Hollywood—and of travel writers long before that”, Adam

McGee (

2012, pp. 232–33) goes so far as to say that “in the popular arena,” the depiction of “voodoo continues, unabated and mostly under the radar, to disseminate and reinforce centuries-old racist tropes about blacks and black religiosity.”

Additionally, in previous work, I have lamented that news reports often circulate false or misleading tales about African diaspora religions. For instance, from at least 2001 to 2015, there was a plethora of news articles alleging that “voodoo” was being used to intimidate female victims of human trafficking and prevent them from leaving their captors (

Boaz 2023). I argued that such widely circulated stories, which were about practices completely unrelated to Vodou, have a negative impact on the religious freedom of devotees of African diaspora religions.

Although I am unaware of any studies examining the impact of the Internet/social media on views of African diaspora religions, the survey included this as the modern-day equivalent of the travelogs, news articles, television shows, and movies that have so often “informed” the public about these faiths. Since so many people use social media and the Internet to obtain information today, it is important to understand whether these sources are providing the public with positive, neutral, or negative depictions of these religions.

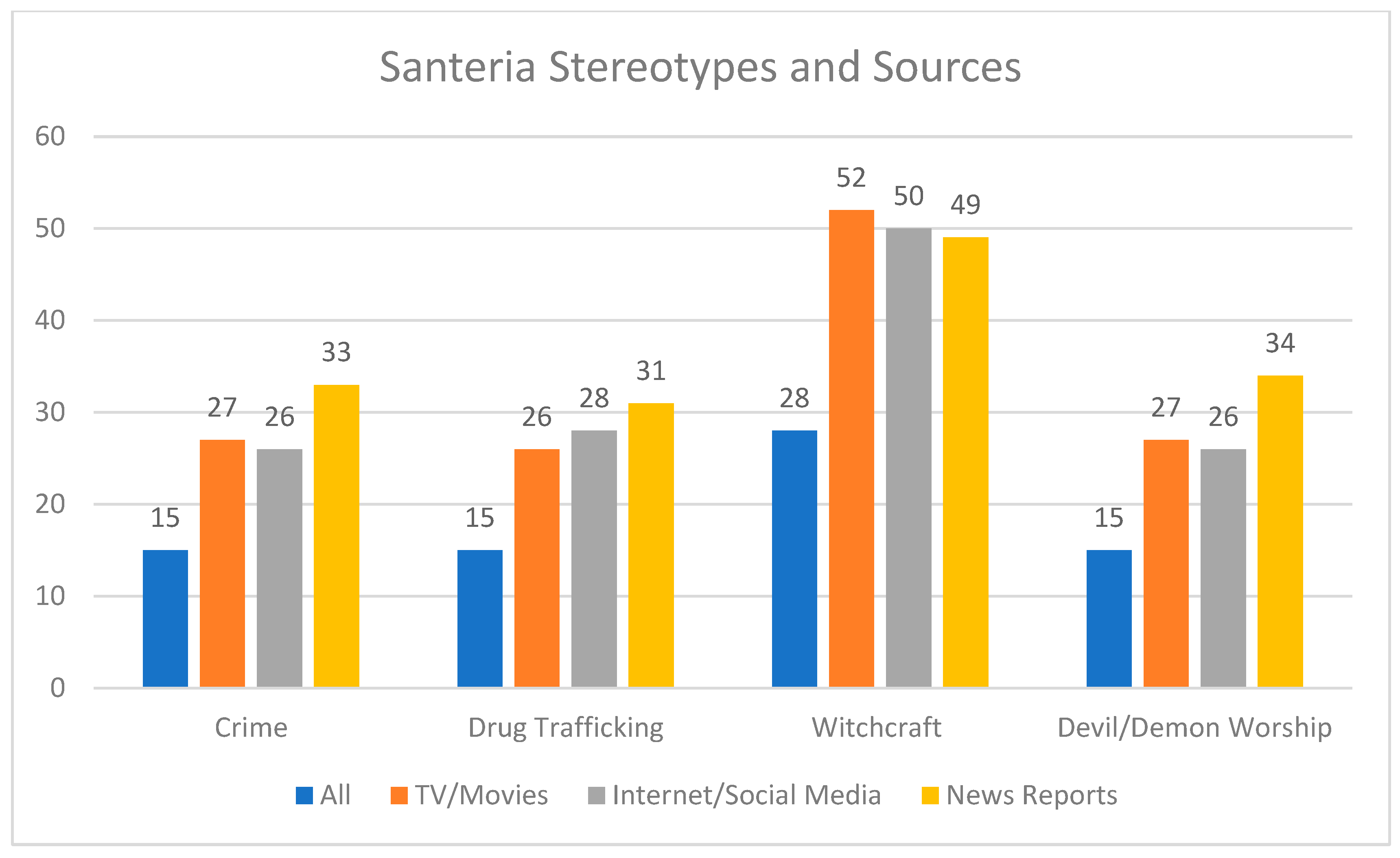

The responses to the survey suggest that all three sources have some negative impacts on public perceptions of African diaspora religions. For example, among respondents who reported that they learned about Vodou/Voodoo from TV/movies or the Internet/social media, the percentage who believed that Vodou/Voodoo devotees were more likely to practice witchcraft or black magic jumped from 73% overall to 83% or 82%, respectively (

Figure 14).

Interestingly, news reports seemed to have the most impact on respondents’ views of Vodou/Voodoo. Respondents who linked it with crime jumped from 32% overall to 49% among people who used news reports as a source of information. Those who believed followers were more likely to traffic drugs leaped from 25% overall to 39%, and those who associated followers with devil or demon worship increased from 36% overall to 51%. News reports had a similar impact to TV/movies and the Internet/social media regarding views of witchcraft or black magic. The percentage who selected Vodou/Voodoo increased from 73% overall to 82%.

The data on Santeria is insufficient to analyze the impact of these sources. Because so many respondents reported no knowledge of Santeria and selected “I know nothing” on the question about sources of information, there are not enough respondents who selected these sources to conclusively determine their impact. However, we can confidently observe that most respondents report little exposure to Santeria from any source. Those who have were most likely to learn about it from one or more of these three sources (TV/movies, Internet/social media, news reports) (

Figure 15). Additionally, it appears that those who have at least some information about Santeria from these sources are likely to have been exposed to negative stereotypes about it. The respondents who selected one or more of these sources were twice as likely to associate Santeria with crime, drug trafficking, witchcraft, and devil or demon worship.

4.4.4. Conclusions About Knowledge of African Diaspora Religions

The responses to these questions suggest that the average person in the United States has very little knowledge of Santeria. Respondents felt a little more knowledgeable about Vodou/Voodoo, which was only slightly less familiar than other nonmainstream religions in the U.S. such as Hinduism and Satanism. Respondents feel most knowledgeable about Abrahamic religions, especially Christianity. Despite reporting little knowledge about African diaspora religions, some respondents formed negative opinions about them. They especially tended to agree with stereotypes about devotees worshiping the devil or practicing witchcraft.

Where respondents did have knowledge about or familiarity with African diaspora religions, they most often obtained their information from television shows, movies, the Internet, social media and/or news reports. Few people are learning about these faiths from practitioners or in universities. These sources, especially news reports, may be directly connected to the prevalence of some negative stereotypes.