Buddhist Priests’ Traditional Activity as a De Facto Community Outreach for Older People with Various Challenges: A Mixed Methods Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Qualitative Approach

At that time, there was a problem with a group of juvenile motorcycle gangs. They were gathering at a house I visited. When I was arguing with them about stopping the dangerous group of motorcycle runaways, the parents there told me that they had given up on them. So, I said to them, “You gave birth to them; so, you are responsible for them, and as parents, you should stand together against them.” Then, I told the gang “I will not even give you a funeral, if you die,” and they were surprised. After a while, the bad boys stopped doing bad things. After a long time, I went to an old lady’s funeral, and two young men in business suits came and thanked me for what I had done (i.e., stopped them, that had made them return to the right way). I was happy.(Z)

I, myself, listen to an old lady for a long time because her stories are interesting, but some priests try to leave (the house) at 5 pm.(K)

Many priests are unaware about the monthly visits having a function of grief care. However, I think it is amazing that they are doing it naturally, without recognizing that it is grief care. It means there is a treasure in that custom that no one knows about.(N)

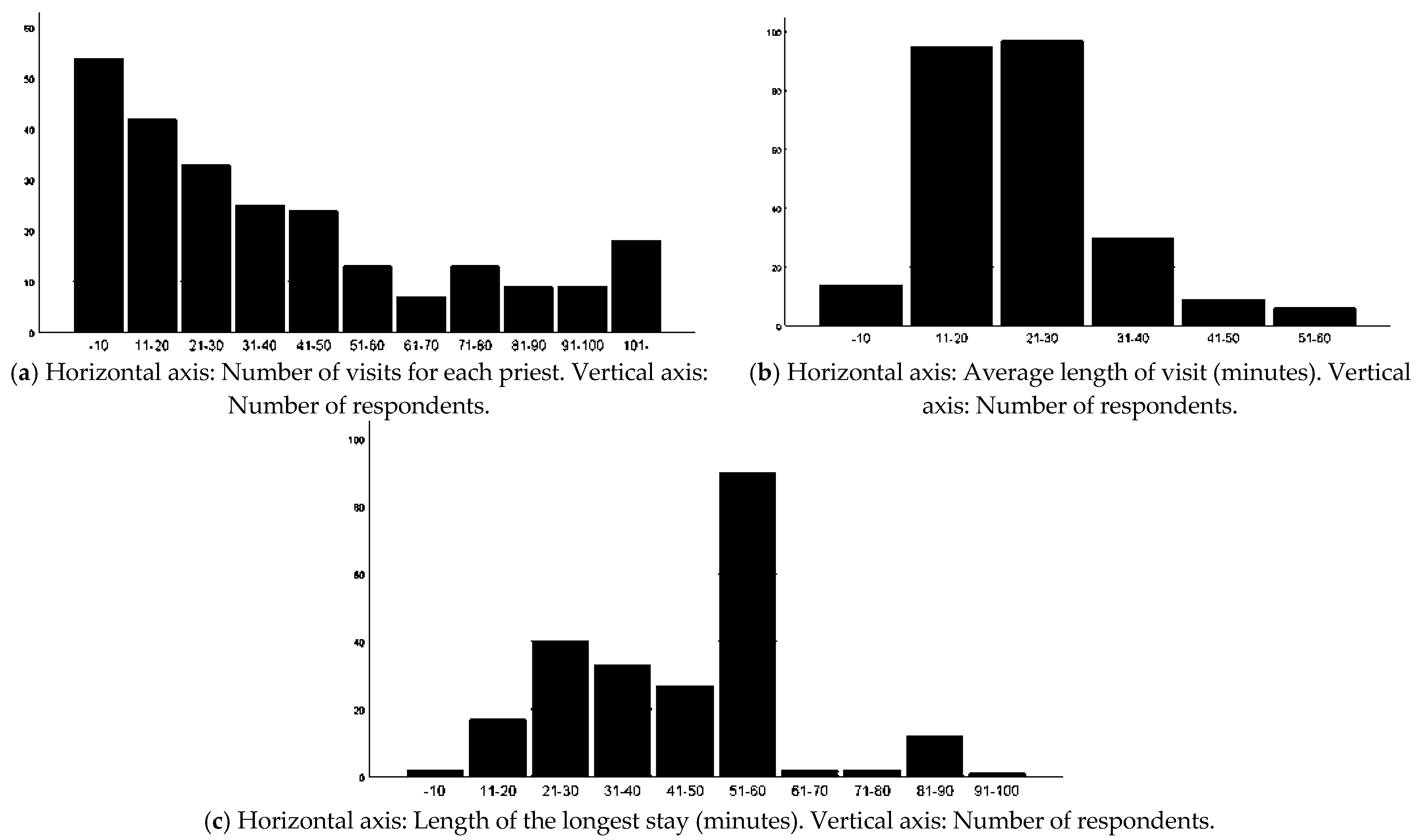

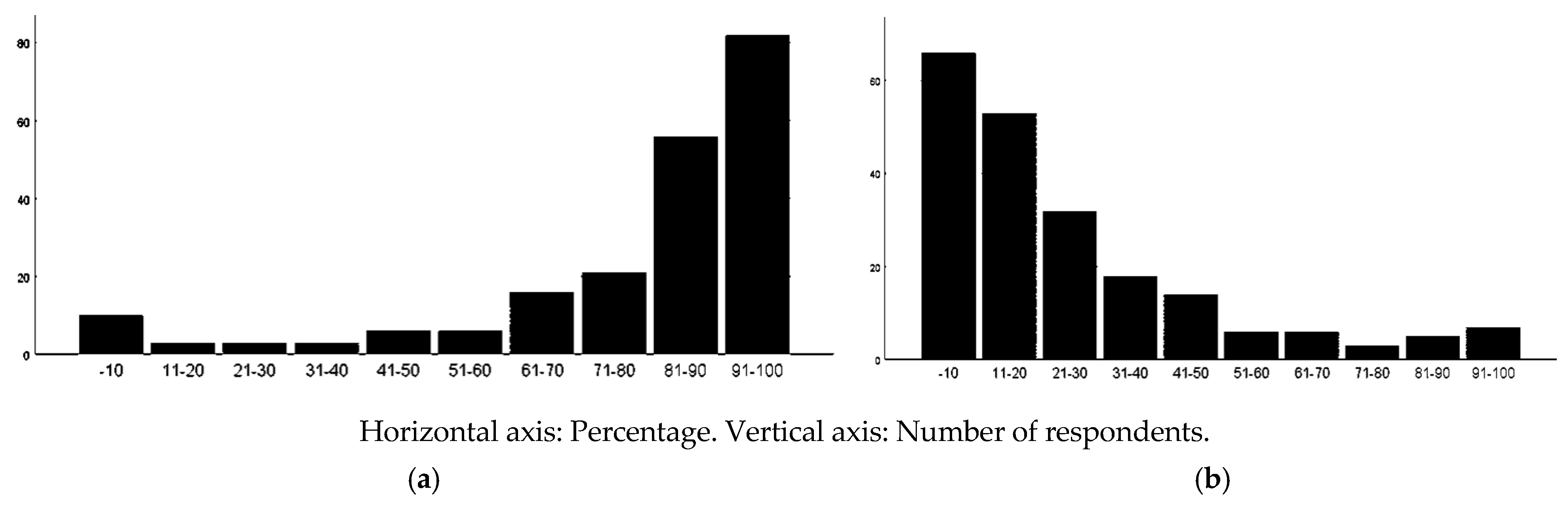

2.2. Quantitative Approach

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

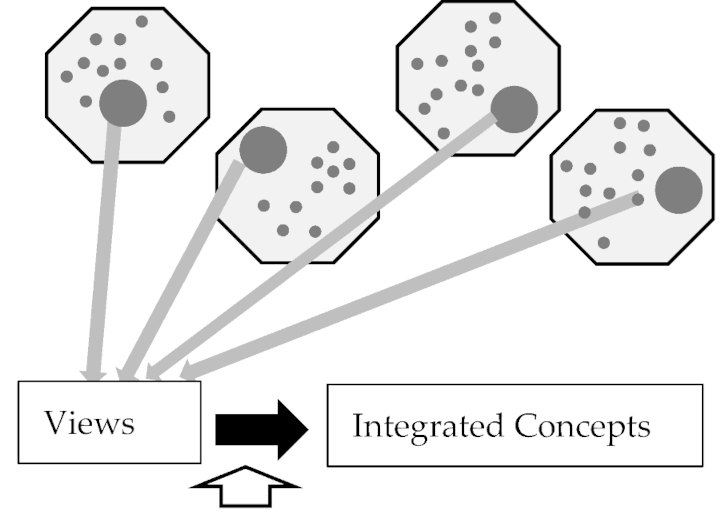

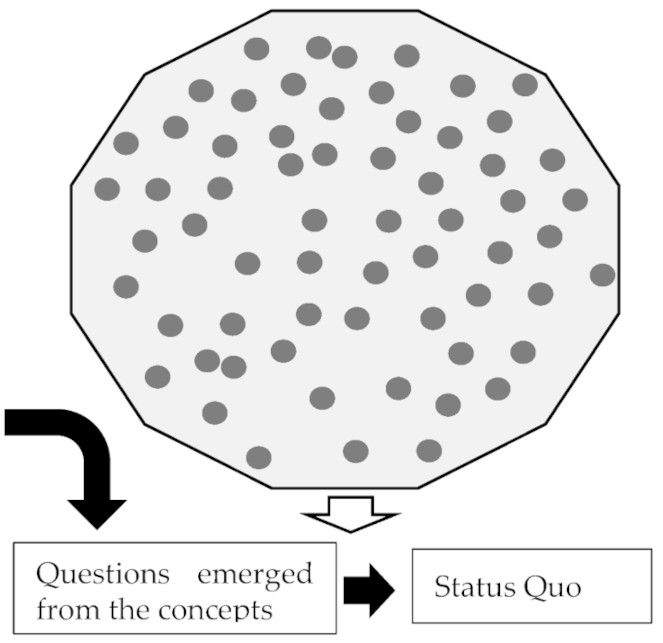

4.1. Methodology

4.2. Qualitative Approach

4.2.1. Participants

4.2.2. Methods

4.2.3. Data

4.2.4. Analysis

4.3. Quantitative Approach

4.3.1. Participants

4.3.2. Methods

4.3.3. Data

4.3.4. Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | According to Ogawa et al. (2022a), in Japan, the monthly home visit is universally implemented in a wide range of denominations including older and more conservative Buddhism. Considering that, as far as we searched, there is no previous research on a similar practice, the community outreach practice of Buddhist priests might be a phenomenon worth mentioning that represents one of the possibilities of Buddhist practice. On the other hand, in areas with more ancient Buddhist traditions and more followers than in Japan, people tend to visit temples more often, so the need for community outreach might be small. This was beyond the scope of our current research, and is the topic of further research. |

References

- Awata, Shuichi, Per Bech, Sumiko Yoshida, Masashi Hirai, Susumu Suzuki, Motoyasu Yamashita, Arihisa Ohara, Yoshinori Hinokio, Hiroo Matsuoka, Yoshitomo Oka, and et al. 2007. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the World Health Organization-Five Well-Being Index in the context of detecting depression in diabetic patients. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 61: 112–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, Timothy O. 2018. Practicing Spiritual Care in the Japanese Hospice. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 45: 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniol, Mathieu, Michelle McIsaac, Lihui Xu, Tana Wuliji, Khassoum Diallo, and Jim Campbell. 2019. Gender Equity in the Health Workforce: Analysis of 104 Countries. Working Paper 1. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office. 2017. Annual Report on the Aging Society: 2017. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/english/annualreport/2017/pdf/c1-2-1.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Creswell, John W., and Vickil Plano Clark. 2007. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 1st ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrant, Gaëlle, Luca Maria Pesando, and Keiko Nowacka. 2014. Unpaid Care Work: The Missing Link in the Analysis of Gender Gaps in Labour Outcomes. OECD Development Centre. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2014/12/unpaid-care-work-the-missing-link-in-the-analysis-of-gender-gaps-in-labour-outcomes_d26d4043/1f3fd03f-en.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Ilmi, Ani Auli, Lisa McKenna, Maria Murphy, and Kusrini S. Kadar. 2024. Spiritual care for older people living in the community: A scoping review. Contemporary Nurse 9: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). 2022. Community-Based Integrated Care in Japan—Suggestions for Developing Countries from Cases in Japan. Available online: https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/1000048192.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Jodo Shu. 2018. Jodo Shu Dictionary. Tsuki-Mairi. Available online: http://jodoshuzensho.jp/daijiten/index.php/%E6%9C%88%E5%8F%82%E3%82%8A (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. 2016. Agency for Cultural Affairs. Religious Yearbook 2016. Available at s-STAT (Statistics Bureau of Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications). Available online: http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/NewList.do?tid=000001018471 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- National Police Agency. 2021. Police of Japan 2021. Human Resources. Available online: https://www.npa.go.jp/english/Police_of_Japan/2020/poj2020_p8-10.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Neergaard, Mette Asbjoern, Frede Olesen, Rikke Sand Andersen, and Jens Sondergaard. 2009. Qualitative description—The poor cousin of health research? BMC Medical Research Methodology 9: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, Yukan, Akinori Takase, Masaya Shimmei, Chiaki Ura, Machiko Nakagawa, and Tsuyoshi Okamura. 2022a. Geography over doctrine? Factors affecting the role of Buddhist priests in a community-based integrated care system. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 37: 5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, Yukan, Akinori Takase, Masaya Shimmei, Shiho Toishiba, Chiaki Ura, Mari Yamashita, and Tsuyoshi Okamura. 2022b. Meaning of death among care workers of geriatric institutions in a death-avoidant culture: Qualitative descriptive analyses of in-depth interviews by Buddhist priests. PLoS ONE 17: e0276275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, Tsuyoshi, Chiaki Ura, Mika Sugiyama, Hiroki Inagaki, Fumiko Miyamae, Ayako Edahiro, Tsutomu Taga, Shuji Tsuda, Riko Nakayama, Kae Ito, and et al. 2022. Factors associated with inability to attend a follow-up assessment, mortality, and institutionalization among community-dwelling older people with cognitive impairment during a 5-year period: Evidence from community-based participatory research. Psychogeriatrics 22: 332–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamura, Tsuyoshi, Masaya Shimmei, Akinori Takase, Shiho Toishiba, Kojun Hayashida, Tatsuya Yumiyama, and Yukan Ogawa. 2018. A positive attitude towards provision of end-of-life care may protect against burnout: Burnout and religion in a super-aging society. PLoS ONE 13: e0202277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothenstein, Mikael. 2004. Science and Religion in the New Religions. In The Oxford Handbook of New Religions Movement. Edited by James R. Lewis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Sano, Junko, Yuzuki Hirazawa, Kohei Komamura, and Shohei Okamoto. 2023. An overview of systems for providing integrated and comprehensive care for older people in Japan. Archives of Public Health 81: 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrimpf, Monika. 2018. Medical Discourses and Practices in Contemporary Japanese Religions. In Medicine—Religion—Spirituality. Edited by Dorothea Lüddeckens and Monika Schrimpf. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 57–89. [Google Scholar]

- Shorten, Allison, and Joanna Smith. 2017. Mixed methods research: Expanding the evidence base. Evidence-Based Nursing 20: 74–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Robert John. 1974. Ancestor Worship in Contemporary Japan. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Society for Interfaith Chaplaincy in Japan. n.d. Certified Interfaith Chaplaincy List. Available online: http://sicj.or.jp/uploads/2017/11/e223ec6887ddd317f4515a8167b7a33c.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Takahashi, Hara. 2022. Buddhist Spiritual Caregivers in Japan. In The Routledge Handbook of Religion, Medicine, and Health. Edited by Dorothea Lüddeckens, Philipp Hetmanczyk, Pamela E. Klassen and Justin B. Stein. Oxford: Taylor and Francis, pp. 171–85. [Google Scholar]

- Taniyama, Rev Yozo, and Carl B. Becker. 2014. Religious Care by Zen Buddhist Monks: A Response to Criticism of “Funeral Buddhism”. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought 33: 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori, Abbas, and John W. Creswell. 2007. Exploring the Nature of Research Questions in Mixed Methods Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1: 207–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Area | Sex | Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Nagoya | M | 30s |

| S | Osaka | M | 40s |

| T | Osaka | M | 40s |

| I | Osaka | M | 40s |

| F | Osaka | M | 40s |

| K | Osaka | M | 40s |

| E | Akita | M | 40s |

| A | Akita | M | 60s |

| Y | Akita | M | 50s |

| H | Akita | M | 30s |

| D | Akita | M | 30s |

| X | Akita | M | 30s |

| M | Kanagawa | M | 60s |

| Z | Kanagawa | M | 70s |

| Categories | Sub Categories | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Finding incidents | The function of finding hikikomoris, and being able to help them at any time. | Sometimes I meet a son who never goes out of the house (F). |

| Sometimes it is difficult to ask clearly, but in the houses we visit, there may be an unmarried son, who is not working, who we think is a hikikomori (I). | ||

| There are many single people in their 40s and 50s, and some who are hikikomoris (E). | ||

| The function of finding people with dementia | I noticed that the person was getting the dates and timings of temple-related events wrong (S). | |

| I was visiting and reading sutra, when I noticed the person urinating in a washbowl behind me (T). | ||

| I noticed (dementia symptoms) because I kept getting calls from the person in the middle of the night (F). | ||

| I noticed (dementia symptoms) because things in the room were getting more and more confusing (K). | ||

| Family members do not notice (older people’s dementia) because they only meet at night. I notice when non-family members enter the house on a regular basis (A). | ||

| Once I noticed that the apples in the offering were upside down (Y). | ||

| The function of finding people with poor physical conditions. | A woman who lives alone does not use the air conditioner no matter how hot it gets, and I watch her with concern (T). | |

| Noticing that the stove was unsafe because of poor maintenance, I contacted the family (A). | ||

| I visited an old woman and found her unconscious in bed. She had wrongly taken sleeping pills (S). | ||

| Preventing suicides | I believe that the monthly visit is a factor that prevents suicide (N). | |

| I feel that monthly suicides are few among the people whom I visit (S). | ||

| Caring for older people | The function of physical care | The topics were mostly diseases of the elderly, about which, I became more and more familiar. The most common was knee pain (I). |

| The function of dementia care (cognitive stimulation) | People with dementia put on makeup and improve their activities when they have guests. Some people with dementia have lost contact with their families even at home, but (talking with a priest) is their only contact with society (K). | |

| Talking with priests is a good stimulus (I). | ||

| The function of mental health care | I kept visiting the home of a woman who could not get her room cleaned up (F). | |

| I notice people with “nursing depression” right away because they lose about 10 kg of weight (A). | ||

| Grief care | When I learned about grief care, I realized that it was the monthly visits that suppressed the anniversary reaction. This is because having others come and talk with them helps them to regain their daily vitality. I explain to the believers how the monthly visit was created to suppress the anniversary reaction. I do not do this for an offering (N). | |

| During my monthly visiting, I was asked by a person to go to Sandakan, Indonesia, to visit a friend of his, who was buried there, during World War II. Thinking that this was a chance encounter, I went there for his sake, at my own expense (S). | ||

| The monthly visit clearly has a grief care function (K). | ||

| When I go to a support group for the bereaved families of those who have died by suicide, I cannot talk to them one-on-one, but at the monthly visit, I can talk to them one-on-one (F). | ||

| I started a new monthly home visit to the home of an old woman who lost her son to suicide. At first, she was depressed, so I invited her to come to the temple because people of her age would be there, and when she started coming, she recovered (D). | ||

| Supporting a peaceful passing | The older people in the houses I visit are familiar with me because they have known me since I was a little boy. (When I was visiting one house), the old lady crawled out and said, “I do not think I will see you again next time, thank you for your care”, to which I replied, “What are you talking about? I shall see you next month”, but soon she passed away. She gave me a final goodbye (Z). | |

| An old man I was visiting suddenly asked, “Priest, do you think there is really a paradise?” I told him, “We continue to live in people’s hearts, and the Pure Land is the same”. The next day, I heard that the man had passed away (K). | ||

| Connecting people | Preventing loneliness | The monthly visit gives people a sense of connection (N). |

| The monthly visit gives people an opportunity to talk to someone (T). | ||

| I think it is the same as providing aftercare to those who have obtained housing through homeless assistance. Some people are lonely even if they have families. We are there to create a safe place in the hearts of the residents (K). | ||

| For the elderly who are isolated from the rest of the family, the monthly visit is the only contact they have (K). | ||

| The monthly visit gives people an opportunity to talk to someone about something they cannot talk about with their family (A). | ||

| Building deep relationships between people and Buddhist priests | We meet in person every month so we can build relationships and trust (T). | |

| What social welfare and artificial intelligence cannot do, and what remains for Buddhist priests to do, is to listen to spiritual matters (K). | ||

| It deepens connections with the residents. Buddhist priests who do not make monthly visits tell me that our position is special, that they (are not familiar with the believers, and that they) do not go out for a beer with them (M). By going to the house, we actually know who lives there (M). | ||

| Support in daily life | If the gas is shut off by a safety device after an earthquake, the older people will not be able to restore it. I will help them when I am called (S). | |

| Several times a year, I am asked to come because they do not know how to adjust the settings on their air conditioners (S). | ||

| Community building | They are moving from their previous home to another, but they do not know how to get along with their neighbors, and they depend on us (S). | |

| We are in a neutral position to round out the community’s troubles. Everyone accepts when priests suggest a solution (A). | ||

| Monthly Home Visits | ||||

| Did (n = 271) | Did Not (n = 27) | p-Value | ||

| Sex | Male | 254 | 25 | 0.648 |

| (95%) | (93%) | |||

| Female | 14 | 2 | ||

| (5%) | (7%) | |||

| Age (years) | Below 60 | 124 | 11 | 0.686 |

| (47%) | (42%) | |||

| Over 60 | 141 | 15 | ||

| (53%) | (58%) | |||

| Collaboration with public sectors | Present | 98 | 17 | 0.012 * |

| (37%) | (63%) | |||

| Absent | 169 | 8 | ||

| (63%) | (37%) | |||

| Other qualifications | Absent | 107 | 7 | 0.628 |

| (46%) | (39%) | |||

| Present | 124 | 11 | ||

| (54%) | (61%) | |||

| Edo Period (Tokugawa Shogunate) (1603–1848) | 21 | 9% |

| Pre-World War II of Modern Japan (1868–1945) | 70 | 29% |

| Post-World War II of Modern Japan (1945–) | 29 | 12% |

| Did not know | 118 | 50% |

| All | Usual (–59) | High (60–) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 246 | N = 184 | N = 62 | p Value | |

| Items concerning priests’ recognition | ||||

| An opportunity to deepen trust with parishioners. | 234 (86%) | 172 (94%) | 57 (92%) | 0.772 |

| An opportunity for older persons living alone to talk with a Buddhist priest. | 209 (77%) | 153 (83%) | 52 (84%) | 1.000 |

| An opportunity for Buddhist priests to watch over older persons and notice any unusual changes in them. | 144 (53%) | 103 (56%) | 37 (60%) | 0.658 |

| An opportunity for believers to consult with Buddhist priests about problems in their daily lives. | 108 (40%) | 73 (40%) | 31 (50%) | 0.181 |

| An opportunity for grief care. | 92 (34%) | 65 (35%) | 24 (39%) | 0.649 |

| An opportunity for congregation members to consult with Buddhist priests about mental and physical issues. | 90 (33%) | 61 (33%) | 28 (45%) | 0.095 |

| Items concerning suicide prevention | ||||

| Being involved in activities related to suicide prevention. | 3 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 0.157 |

| Items concerning priests’ practice | ||||

| Experienced listening to people’s recent situation. | 213 (79%) | 154 (84%) | 56 (92%) | 0.141 |

| Experienced consultations regarding Buddhist matters. | 201 (74%) | 145 (79%) | 54 (89%) | 0.129 |

| Experienced noticing dementia or physical deterioration. | 182 (67%) | 127 (69%) | 54 (87%) | 0.005 ** |

| Experienced listening to people with physical ailments. | 177 (66%) | 129 (70%) | 45 (74%) | 0.629 |

| Experienced listening to memories of the deceased. | 117 (43%) | 83 (45%) | 31 (51%) | 0.462 |

| Experienced being asked for advice about a serious issue. | 115 (42%) | 72 (39%) | 41 (66%) | >0.001 *** |

| Experienced listening to the problems of family relationships. | 95 (35%) | 65 (35%) | 29 (48%) | 0.097 † |

| Experienced being asked to support daily life. | 80 (30%) | 53 (29%) | 27 (44%) | 0.041 * |

| Experienced listening to people with mental health problems. | 69 (26%) | 48 (26%) | 20 (33%) | 0.325 |

| Experienced dealing with the grief of bereavement. | 66 (24%) | 42 (23%) | 23 (38%) | 0.029 * |

| Experienced finding someone whom they were concerned about, but being unsure to what extent to get involved. | 58 (21%) | 28 (15%) | 29 (47%) | >0.001 *** |

| Experienced listening to financial problems | 35 (13%) | 22 (12%) | 13 (21%) | 0.090 † |

| Experienced finding someone they were concerned about, and contacting public authorities, etc. | 24 (9%) | 13 (7%) | 11 (18%) | 0.024 * |

| Experienced finding someone in cardiopulmonary arrest or unconsciousness. | 15 (6%) | 7 (4%) | 8 (13%) | 0.026 * |

| Experienced finding someone whom they were concerned about, but not knowing where to ask for help. | 13 (5%) | 4 (2%) | 9 (15%) | >0.001 *** |

| Items concerning psycho-social characteristics | ||||

| Having good mental well-being. | 187 (73%) | 127 (73%) | 44 (75%) | 1.00 |

| Having general trust. | 236 (90%) | 159 (90%) | 58 (97%) | 0.114 |

| Having general trust in this community. | 201 (79%) | 136 (79%) | 48 (80%) | 1.00 |

| Having attachment to the community. | 239 (92%) | 160 (91%) | 60 (98%) | 0.080 † |

| Basic items | ||||

| Age (>60) | 141 (53%) | 96 (53%) | 30 (51%) | 0.881 |

| Sex (male) | 254 (95%) | 11 (6%) | 2 (3%) | 0.527 |

| Interacting with public sectors | 98 (37%) | 115 (63%) | 37 (61%) | 0.763 |

| Having other qualifications | 124 (54%) | 85 (54%) | 28 (54%) | 1.00 |

| Approach | Qualitative Approach | Quantitative Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Methods | Interview survey | Questionnaire survey |

| Questions | What are monthly home visits? | How they affect the Buddhist priests and our community. |

| Schema | Diverse areas Critical assessments by the interdisciplinary team. including healthcare professionals | One area |

| Questions to Ask about Recognition: “Do You Think Monthly Home Visits Are...?” | Questions to Ask about Practice: “During the Monthly Home Visits, Have You Experienced...?” | |

|---|---|---|

| Finding incidents | ...is an opportunity for Buddhist priests to watch over older persons, and notice any unusual changes in them. | …experienced noticing dementia or physical deterioration. |

| …experienced finding someone they were concerned about, and contacting public authorities, etc. | ||

| …experienced finding someone in cardiopulmonary arrest or unconsciousness. | ||

| Caring for older people | ...is an opportunity for congregation members to consult with Buddhist priests about mental and physical issues. | …experienced listening to people with physical ailments. |

| …experienced listening to people with mental health problems. | ||

| Grief care | …is an opportunity for grief care. | …experienced talking about the deceased. |

| …experienced dealing with the grief of bereavement. | ||

| Preventing loneliness | …is an opportunity for older persons living alone to talk with a Buddhist priest. | …experienced listening to people’s recent situation. |

| …experienced being asked for advice about a serious issue. | ||

| Daily life support | …is an opportunity for believers to consult Buddhist priests about problems in their daily lives. | …experienced being asked for support in daily life. |

| Others | Are you involved in activities related to suicide prevention? | …experienced consultations regarding Buddhist matters. |

| …experienced listening to family relationship problems. | ||

| …experienced listening to financial problems. | ||

| …experienced finding someone whom they were concerned about, but being unsure to what extent to get involved. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ogawa, Y.; Takase, A.; Ura, C.; Nakagawa, M.; Okamura, T. Buddhist Priests’ Traditional Activity as a De Facto Community Outreach for Older People with Various Challenges: A Mixed Methods Approach. Religions 2025, 16, 698. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060698

Ogawa Y, Takase A, Ura C, Nakagawa M, Okamura T. Buddhist Priests’ Traditional Activity as a De Facto Community Outreach for Older People with Various Challenges: A Mixed Methods Approach. Religions. 2025; 16(6):698. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060698

Chicago/Turabian StyleOgawa, Yukan, Akinori Takase, Chiaki Ura, Machiko Nakagawa, and Tsuyoshi Okamura. 2025. "Buddhist Priests’ Traditional Activity as a De Facto Community Outreach for Older People with Various Challenges: A Mixed Methods Approach" Religions 16, no. 6: 698. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060698

APA StyleOgawa, Y., Takase, A., Ura, C., Nakagawa, M., & Okamura, T. (2025). Buddhist Priests’ Traditional Activity as a De Facto Community Outreach for Older People with Various Challenges: A Mixed Methods Approach. Religions, 16(6), 698. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060698