This section of the study initially defines the concept of political grief and two related notions: the assumptive world and shattered assumptions. It serves as the theoretical basis for explaining anti-communism within the South Korean church. Additionally, this study investigates significant aspects that impact anti-communism within the South Korean church. It is crucial to define the meaning of the “South Korean church” as employed in this study for a comprehensive discussion. The South Korean church in this study is the Protestant church in South Korea. The latest statistics indicate that the overall population of Protestant churches is almost 20% (

KOSIS 2015). The South Korean church comprises 374 Protestant denominations and 286 denominations under the umbrella of the “Presbyterian Church of Korea” (

MCST 2018). Due to time constraints and physical limitations, it is difficult to compare and analyze the perceptions of all denominations. This study focuses on two organizations in the South Korean church: the National Council of Churches in Korea (NCCK, 1924–), which challenges anti-communism, and the Christian Council of Korea (CCK, 1989–), which reinforces it. The establishment of the CCK was in strong opposition to the NCCK’s 88 Declaration (1988), which included a confession of guilt for division and anti-communism. However, the history of the CCK does not encompass the entire development of anti-communism in South Korea (1948–), and within a particular denomination or religion, individuals exhibit diverse tendencies: they are joined and organized based on their stances of opposition to or support for anti-communism. Thus, this study classifies two contrasting perspectives on anti-communism: the conservative church, which reinforces anti-communism, and the progressive church, which challenges it.

2.1. Definition of Political Grief and the South Korean Church’s Political Grief

Grief is closely associated with “the personal response to loss” (

Harris 2022). Generally, grief is defined as the emotional reaction to the personal loss of a loved one. Recent research suggests there can be a political form of grief. Harries identifies two distinct dimensions of political grief (“ibid.”): 1. A poignant sense of assault to the assumptive world of those who struggle with the ideology and practices of their governing bodies and those who hold political power. 2. Direct losses that are experienced by individuals as a result of political policies, ideologies, and oppression enacted and/or empowered at the socio-political levels. According to these perspectives, political grief refers to losses due to political reasons (“ibid.”).

A further study suggests that the contexts in which political grief arises and is experienced have become increasingly varied at “micro, mezzo, and macro levels” (

Winokuer and Harris 2012, p. 225). These levels precisely refer to layers of human experience (

Harris 2022). The micro level is the personal level; the mezzo level is the larger social community; and the macro level is the structural and political level of experience. Political grief might be characterized as collective grief on a macro level. Collective grief occurs when significant societal events cause emotional distress for a significant number of people (

Ken 2024). Political grief cannot be confined to a singular domain. This phenomenon, while observed at the collective macro level, directly affects individual lives; both individuals and collectives experience grief.

This research also examines two concepts relevant to political grief. The first is the assumptive world. This is the inherent cognitive framework that understands and interprets the self and the world around us.

Bowlby (

1969) defines the cognitive framework as “working models of the self and of the world”, while

Parkes (

1975) expands the internal working model to encompass the assumptive world.

Harris (

2022) delineates three core concepts that comprise the assumptive world: 1. How we find safety in the world. 2. How we believe things work and why events happen. 3. Our view of ourselves and how we fit into our social spheres. When these three concepts are fulfilled, our assumptive world remains complete and unbroken. However,

Janoff-Bulman (

1992) argues that our assumptive world might be challenged and shattered by life events that contradict our self-perception and understanding of the world around us; consequently, we reconstruct a new assumptive world.

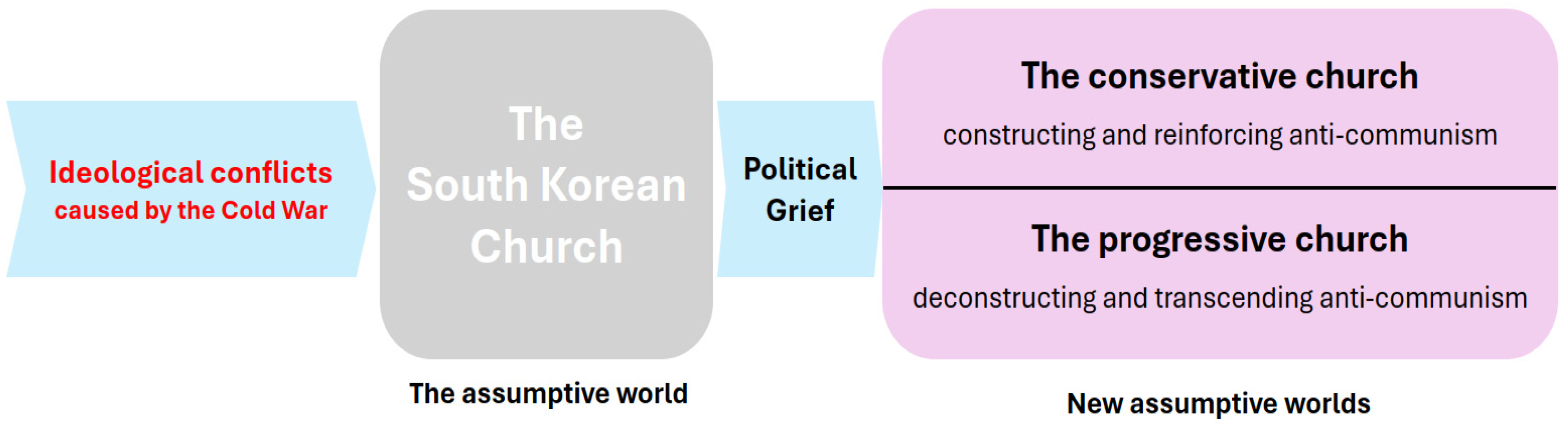

The political grief of the South Korean church can be understood through these theoretical frameworks.

The South Korean church lost its political/ideological world (“the assumptive world”) due to ideological conflicts caused by the Cold War, including the Korean War (1950–1953) (

Figure 1). These conflicts shattered the assumptive worldview and generated “political grief” within the South Korean church. The grief constituted a traumatic experience. The two churches rebuilt their new assumptive worlds. This study asserts that the conservative church’s new assumptive world aims to construct and reinforce anti-communism, and it is perceived that the trauma remains unresolved and has been exacerbated negatively. In contrast, the progressive church’s new assumptive world seeks to deconstruct and transcend the ideology. This study assumes that their traumatic experience has been resolved and constructed positively. This study analyzes the implications of the two assumptions by comparing the perspectives of the two churches on anti-communism. However, this process did not happen all at once but rather through a historical process. Thus, it is crucial to recognize the historical, theological, and socio-political aspects that have influenced the emergence of anti-communism in the South Korean church.

2.2. The Two Churches’ Views on Anti-Communism

Political grief resulting from traumatic experiences has influenced the conservative and progressive churches’ perceptions of anti-communism. The perception shapes the view of North Korea as either an enemy or a friend. To examine the new assumptive worlds of the two churches concerning anti-communism, it is essential to investigate the meaning of anti-communism that they uphold. This study examines three aspects: historical, theological, and socio-political aspects. This study explores these three aspects because anti-communism has changed over time and continues in both churches (“historical aspect”). The two churches have responded to these changes (“theological aspect”). For the socio-political aspect, the South Korean church’s anti-communist perspective is influenced by the political orientation of the government, predominantly conservative and progressive governments. However, this study cannot encompass all elements at the same time; therefore, it focuses on the significant anti-communist features of both conservative and progressive churches in each aspect.

Conservative and progressive churches in South Korea hold divergent stances on anti-communism. However, the two churches did not initially have opposing views on it; they had the same stance on anti-communism and North Korea. Their identification of North Korea as the enemy stems from their own experiences of loss. The conservative church has maintained and reinforced this viewpoint since independence from Japan in 1945, but the progressive church has altered and deconstructed it since the 1970s.

After Korea’s liberation from Japan in 1945, the US–Soviet Joint Committee established a trusteeship over the Korean Peninsula from 1945 to 1948, leading to a political and ideological division: the United States governed the South, while the Soviet Union administered the North. The committee drew the 38th parallel as a physical demarcation to define the limits of each side’s jurisdiction. Following the trusteeship, the two Koreas established their own leadership in 1948: the Rhee Syng-man government in the South was founded on American capitalism, whereas the Kim Il-sung regime in the North was initially built on Soviet communism. In this context, the physical and ideological division, along with the painful experience of the Korean War (1950–1953), strengthened anti-communism, which in turn solidified a negative attitude toward North Korea. In addition, Christians who fled North Korea significantly contributed to this. A considerable number of Christians from the North relocated to the South to escape communism (

Kang 2008). They exhibited a vehemently antagonistic attitude toward communism and North Korea. Their relocation exacerbated ideological disputes throughout South Korean society and the church.

Despite these experiences of loss, however, since the 1970s, the progressive church has offered a different perspective on North Korea and anti-communism. The progressives regard North Korea as a friend and have exerted significant efforts to transcend the prevailing ideology. The experience of the May 18 Democratic Uprising (1980) inspired the progressives to overcome the division of the Korean Peninsula. Before the tragedy, the progressive church mainly focused on the democratization and human rights movements in the 1970s. However, the prospect of democratization following Park’s authoritarian regime (1963–1979) was curtailed by the resurgence of Chun’s military dictatorship. According to Lee Sam-yeol, with the May 18 Democratic Uprising, the progressive “became acutely aware that overcoming national divisions and achieving reunification is essential for true democracy.” (

S.-y. Lee 1988). Consequently, the emphasis on democratization shifted to resolving the division of the Korean Peninsula. This movement compelled the South Korean progressive church to confront the division and reunification of the Korean Peninsula, and they invested significant effort to achieve this objective.

The National Council of Churches in Korea (NCCK), presented as the progressive ecumenical organization in South Korea, conducted multiple international consultations supported by the World Council of Churches (WCC) and international churches: the Tozanso Consultation (1984), the Glion Conferences (1986, 1988, 1990, and 1995), and the WCC’s World Convocation on Justice, Peace, and the Integrity of Creation (JPIC, 1990). The main aim of the consultations was to establish an environment for church leaders from North Korea and South Korea to discuss peace and reunification on the Korean Peninsula and to develop guiding principles on this matter. During these solidarity endeavors, leaders from South and North Korean churches convened for historic talks, promoting continuous interaction between the two congregations. Ultimately, the NCCK promulgated the 88 Declaration regarding the division and reunification of the Korean Peninsula, which incorporated a unique theological perspective on structural sin and a confession of the peninsula’s division and anti-communism.

However, while the NCCK’s 88 Declaration introduced a new alternative theology for the division of the Korean Peninsula, it also fueled the conservative churches’ sense of crisis. The Christian Council of Korea (CCK) was established in staunch opposition to the declaration. Since then, the two church organizations have been the representative positions of the South Korean church in relation to anti-communism.

- B.

Theological aspect

Both churches expressed their theological positions on anti-communism. The conservative church developed a theological justification that unequivocally designated communism and North Korea as enemies, based on their historical experiences of loss; in contrast, the progressive church dismantled the conservative church’s framework and presented an alternative theological perspective on the division of the Korean Peninsula like the 88 Declaration.

The conservative church’s theological view of anti-communism defines communism as atheism. North Korea, which is based on anti-communism, is an atheist state. In contrast, Christianity becomes theism. This difference soon forms a tense relationship between atheism and theism. From their standpoint, all those who do not believe in God become “God’s enemies”. Subsequently, the church characterizes this atheistic state as an enemy of God. This tension is strengthened by their eschatological interpretation. They interpret the apocalypse as the end of the world, and they interpret this world as a spiritual war between good and evil, like the war of Armageddon in the Book of Revelation. Therefore, this eschatological interpretation is that North and South Korea will become atheistic and theistic countries, and this will be a battle between evil and good in terms of a spiritual war. The employment of violence and curses against them is hence theologically legitimized. Many pastors have had this perception, and sermons based on this viewpoint can be used to promote persistent hostility and demonization of North Korea within the South Korean church.

The progressive church, however, considers North Korea as a friend. The church provides alternate perspectives on North Korea and the North–South divide. In 1988, the NCCK issued the 88 Declaration. The declaration refers to the division of the Korean Peninsula as “the result of the structural sins of the Cold War system, and the cause of structural sins within North and South Korean society” (

NCCK 2000, p. 104). Lee Sam-yeol, one of the authors of the 88 Declaration, explains why the NCCK needs to see structural evil as such: “When we fail to see the division itself as an evil and try to see the cause of the tragedy in the consequences of the division, we will not be able to understand the problems of the divided system, nor will we be able to grasp the way to overcome the division” (

S.-y. Lee 2019, pp. 21–22). His remarks provide insights into the perception of structural evil in the 88 Declaration. At the same time, it demonstrates the perspective of the South Korean progressive church on the underlying causes and solutions to the Korean peninsula’s division and the problems that result from it.

- C.

Socio-political aspect

The social dimension is inherently political, as the Peninsula’s divide is intricately connected to governmental policies. In particular, the discussion of unification of the divided Korean Peninsula has been strongly driven by the government. The government’s policies influenced the church in this context. Given this political context, starting with the Kim Dae-jung government (1998–2003), there have been changes in the church in relation to politics. The Kim administration was the first progressive government in South Korea’s modern history to successfully implement a regime change. This administration’s perspective on North Korea and its actions markedly diverged from those of preceding administrations. This change has brought about unprecedented transformations in relations with North Korea and anti-communism. Therefore, this study analyzes the role of the church and the governments prior to (1948–1998) and since (1998–present) Kim’s government.

Successive governments propagated anti-communism for an extended period prior to Kim’s government. The conservative church strongly supported the policies of these previous governments because of their strong anti-communist stance. In particular, the first South Korean government, led by Rhee Syng-man (1948–1960), envisioned building a Christian nation based on staunch anti-communism. In this regard, the church became a strong supporter. Despite the fact that Park Chung-hee’s regime (1963–1979) was a military dictatorship, he was in favor of the ideology, given its relationship with North Korea. After Park’s regime, the governments of Chun Doo-hwan (1980–1988), Roh Tae-woo (1988–1993), and Kim Young-sam (1993–1998) also maintained anti-communism.

Since Kim’s administration, progressive and conservative governments have alternated in power, and churches have aligned themselves with these governments’ political tendencies. The political stances of the regime, primarily based on conservative and progressive views, have profoundly influenced North Korea’s cooperative initiatives, as per the policies of the governments. The progressive governments, led by Kim Dae-jung (1998–2003), Roh Moo-hyun (2003–2008), and Moon Jae-in (2017–2022), stressed the improvement of relations with North Korea and engaged in various political initiatives for better relations. However, the conservative governments, led by Lee Myung-bak (2008–2013), Park Geun-hye (2013–2017), and Yoon Suk-yeol (2022–2025), employed a passive strategy toward mending relations, prioritizing South Korea’s national security. The absence of trust between the conservative administrations and the North Korean leadership hindered any possible transition between North and South Korea. As a result, the progressive church has supported progressive governments and criticized conservative ones. Conversely, the conservative church has been strongly supportive of the conservative governments and strongly critical of the progressive ones. This environment intensified deep divisions and political polarization between advocates of anti-communism and those aiming to overcome them (“ibid.”,

Harris 2022, p. 586).