Abstract

Contemporary Congregational Songs (CCS) are used for gathered musical worship in churches of diverse traditions and denominations all over the world. Christian Copyright Licensing International (CCLI) has measured the use of CCS in licensed churches in various global regions for over 30 years. This article examines the trajectory of songs as they enter and exit the biannual CCLI top songs lists over a 10 year period from 2014–2023. Hillsong has been one of the most prominent producers of CCS, with dominant appearances in the CCLI top song lists for the last three decades. However, they have not released any new CCS since 2021. This article explores what has happened over the past few years to the void left by such a dominant producer of CCS, and what that might mean for the genre and its future.

1. Introduction

Much has been written about Hillsong Church and its music, mostly in the popular press, but increasingly in academic contexts as well (Riches and Wagner 2018; Wagner 2013; Martí 2018; Cowan 2017; Evans 2006). Indeed, it has been under my scholarly scrutiny in relation to its prominence within the contemporary congregational song (CCS) genre (Thornton 2017, 2021b, 2023). However, much of the broader scholarship on Hillsong is from at least six years ago, and significant changes have occurred in the Hillsong movement in more recent times. Rocha’s Cool Christianity: Hillsong and the Fashioning of Cosmopolitan Identities (Rocha 2023) would be the exception and does address more recent Hillsong issues and media attention in her conclusion, however, its focus is on the implication of these changes to the Brazilian context. This article seeks to examine Hillsong as a historically dominant producer of CCS and explore the way in which recent scandals and changes within the organization have indelibly marked a new era for the genre. Additionally, this article seeks to identify trends in the CCS genre that affect the introduction and tenure of new songs to local church worship contexts.

With those goals in mind, I begin by outlining the parameters of the study, including the methods employed to analyse the data. I then provide some contextual information about Hillsong church, its history, its music, and recent events. From there, we move into the findings, analysis, and synthesis, which leads to the conclusion that Hillsong’s place within the CCS industry has been irrevocably altered, as newer CCS producers have filled the gaps left by Hillsong’s changing priorities.

2. Literature and Methodology

The literature relating to Hillsong church will be addressed in the following section, as it connects with their story and their history in the production of contemporary congregational songs. However, some additional background in the field of congregational music-making is helpful in establishing the methodological approach for this study.

Congregational music-making has received growing scholarly interest in recent decades. A Routledge series emerged from the biennial congregational music-making conference held in Oxford, UK, and as of the date of this article, has 10 published volumes ranging in topics from the disciplines involved in congregational music studies (Mall et al. 2021) to music as performance (Steuernagel 2021), ethics (Myrick 2022), mediation (Nekola and Wagner 2015), and race-based perspectives (McKenzie et al. 2024). While there are many disciplines represented in exploring congregational music-making, including history, theology, musicology, and liturgical studies, the most common approach has been ethnomusicological. The result is that there are many accounts of specific worship contexts that are rich, detailed, and nuanced. However, ethnography is not designed to create generalizations. It is precisely its contextual nuance that makes ethnomusicology valuable as a discipline by highlighting individual and context-specific features, phenomena, and meaning-making. However, to understand a genre (be it musical or otherwise), specific contexts must be subservient to more global features, forms, and functions.

There are scholars who have attempted a wider lens on contemporary congregational songs. Ingalls has bridged the gap with Singing the Congregation: How Contemporary Worship Music Forms Evangelical Community (Ingalls 2018), despite the fact that it still centres on several specific contexts. However, most volumes that have attempted to address the genre have engaged with data from Christian Copyright Licensing International (CCLI). Examples include Woods and Walrath’s edited volume The Message In the Music (Walrath and Woods 2010), Open Up The Doors (Evans 2006), and Meaning-Making in the Contemporary Congregational Song Genre (Thornton 2021b). There are certainly limitations to CCLI data. First, it does not provide any context to the most-sung songs, where in practice, churches sing songs in a particular order (a set) with specific transitions between those songs. CCLI is not able to capture such data. When churches report songs, they do not report the order, or the set in which they appeared. Second, CCLI has always been a lag indicator. Up until recently, it has been measured in six-monthly increments after the event; thus, it is always dealing with historical, rather than current, data.1 Third, it is an opaque process of weighting from the company. Although historically, sample rates were quite good, larger churches paying higher license fees had an undisclosed higher weighting to their reports (Thornton 2021b, pp. 35–36). As such, the degree to which megachurches like Hillsong influenced CCLI charts is unknown. This is all the more conspicuous in the Australian CCLI charts, where Hillsong accounted for almost 40% of the Top Songs until recently. Finally, CCLI only measures what local churches (who are licensed with them) sing in their services. It does not account for individual Christian engagement with songs. The reality is that a very small group of people (sometimes just the worship leader) make decisions about what songs the congregation is going to sing on a given Sunday. A song’s appearance in a worship service is not an indication of how it does or does not connect with the congregation as a whole or as individual believers. It is one of the reasons why I have often used YouTube as a counter-set of data, because views of YouTube CCS videos ostensibly show a much more individual level of engagement (Thornton 2021b, pp. 20–23).

Despite the limitations of CCLI, they are still the best source scholars have for knowing what songs in the CCS genre are most connected with local church worship. Over the past decade, newer organizations have begun to emerge including MultiTracks.com, PraiseCharts, and Planning Center, and limited data from these sources is increasingly accessible to researchers; however, for now, CCLI is still the largest and longest-running available data source. It is also a complex data source. CCLI operates in multiple regions around the world. They also provide an array of licenses, such as the (original) Church Copyright License (CCL), SongSelect, and the Music Reproduction License (MRL).

For this study, I have chosen to focus on CCLI’s CCL USA biannual reports, and even then, only on the Top 25 songs for each report. The USA is the largest region by far (and the first serviced by CCLI), and although Hillsong originated in Australia and has shown particular dominance in the Australian charts, in order to reflect a global perspective on Hillsong’s influence, the USA charts are better situated to accomplish this. As for the choice of utilizing the CCL report, it is CCLI’s most popular license, and although I have previously argued that the SongSelect data was more current (Thornton 2016, pp. 69–71), in recent years, the changing landscape of song-sourcing and music chart-sourcing has progressively made that argument less convincing. The justification for only looking at the Top 25 songs is partially historical. When CCLI first started publishing its Top Songs lists for public interest, it was a list of the Top 25. I, and other scholars, have used this as a benchmark, even though now CCLI regularly publicly releases the Top 100 songs in each reporting period. One hundred songs over 10 years would be too large a sample size for a journal article such as this. As such, the Top 25 still provide both a representative and manageable dataset.

The methods employed for this analysis are predominantly quantitative, with specific musical and lyrical features of the CCS being measured, both as individual songs and as a group of songs from this producer within the wider corpus. Some quantitative analysis is also required when it relates to the poetic or theological nature of lyrics. These are the same methods employed in a larger project analysing the CCS genre (Thornton 2021b).

3. The Hillsong Story

The story of the Hillsong movement has been well documented, as referenced above. However, a brief overview of its history will help contextualize this study. Hills Christian Life Centre (as it was originally named) was planted in 1983 by Brian and Bobbie Houston in the midst of the dynamic church-planting culture of the Assemblies of God Australia (now Australian Christian Churches) at that time (Austin 2018, p. 28). From its humble beginnings in a school gym in the north-western suburbs of Sydney, by 2017, Hillsong had become its own church movement (breaking away from its original ties with the Assemblies of God Australia/Australian Christian Churches) encompassing “over 100,000 adherents in 15 countries on five continents”, with its original CCS being “sung weekly by an estimated 50 million people in 60 languages” (Riches and Wagner 2018, p. 2).

Along the journey, the American profile of Hillsong Church entered a new era in 2010 with the planting of Hillsong Church NYC by Brian Houston’s eldest son, Joel Houston, and American-born, but Hillsong-trained pastor Carl Lenz (Reagan 2018, p. 154). Reagan notes that, unlike Hillsong Church’s critically appraised profile in Australia, “[i]n America, Hillsong explicitly emerged as a musical act, yet also implicitly [sic] as a liturgy” (Reagan 2018, p. 155); as such, it was widely admired and embraced for its contribution to modernizing church worship practices. In Reagan’s aptly titled chapter, “The Music That Just About Everyone Sings”, he states, “Over the last 20 years, ‘Hillsong’ became a popular name known by American evangelicals because–and pretty much only because–of its captivating music” (Reagan 2018, p. 158).

Unlike in the USA, Hillsong Church had long been under the scrutiny of Australian media, with almost yearly ‘exposés’ by investigative journalists. However, in 2020, the global Hillsong movement began to show cracks. Hillsong Church fired its high-profile NYC pastor, Carl Lenz, for his affair with Ranin Karim. Shortly after, Hillsong’s founder, Brian Houston stepped down from his position while being investigated for ‘inappropriate behaviour’ with a female staff member, and a drink-driving charge. Other lawsuits appeared on the horizon relating to Brian’s father’s historical child sex abuse, sexual abuse and ‘slave labour’ in Hillsong College, and other purported financial mismanagement. Media swarmed to capitalize on the scandals, including Discovery Plus’ three-part documentary Hillsong: A Megachurch Exposed and FX documentary series The Secrets of Hillsong. Within two years, Hillsong had lost much of its former glory. Churches left the movement, significant numbers left local Hillsong churches, Hillsong College drastically reduced in numbers (which was a result of Australia’s COVID-19 international student restrictions as much as any other factor), and under the new senior pastor’s direction (Phil Dooley), Hillsong stopped actively recording new CCS (Hillsong Steps into a Mission-Focused Future 2023). Shortly thereafter, key musical voices from Hillsong either went silent (for example, Joel Houston), moved to other churches (for example, Aodhan King), or continued to produce new CCS independently of Hillsong (for example, Brooke Ligertwood). With this backdrop, I now turn to the data analysis.

4. Data Analysis

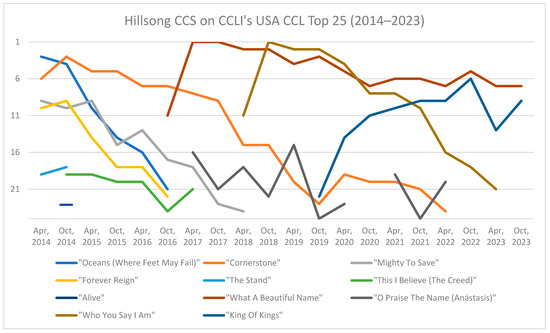

Eleven songs from the Hillsong stable have appeared in the 10-year period (20 CCLI CCL reports) between 2014 and 2023. The songs were written from 2005 (“The Stand”) to 2019 (“King Of Kings”). The median copyright date of Hillsong CCS throughout this period was 2012, which is consistent with previous studies (Thornton 2021b, p. 208). The graph (Figure 1) below provides a quick summary of Hillsong’s prominence across this period (listed in order of chronological appearance on the charts).

Figure 1.

Hillsong CCS on CCLI’s USA CCL Top 25 (2014–2023).

Hillsong has held the #1 position twice in this period; once for two consecutive reports, April 2017 and October 2017, with “What A Beautiful Name”, and then once again in the October 2018 report with “Who You Say I Am”. This is not the first time Hillsong has held the top rank. From 2009–2010, Hillsong’s “Mighty To Save” topped the CCLI CCL charts in the USA, and while “Shout To The Lord”2 never made it to #1, it held at #2 for four years, and besides “Lord I Lift Your Name On High”,3 still has the second longest tenure in the CCLI Top Songs charts alongside “Give Thanks”,4 appearing for 17 consecutive years (approximately 34 reports). In fact, had I started the dataset for this study just one year earlier (2013), it would have included “Shout To The Lord”, written and released 20 years earlier, in 1993.

Of the eleven Hillsong CCS in this dataset, “Cornerstone” had the most appearances (17). Released in 2012, its presence on the charts precedes this dataset, making its longevity in the CCS corpus even more noteworthy. “What A Beautiful Name” was second with 15 appearances. However, given the timeline for this study, “What A Beautiful Name” was only released in 2016, and continues to show signs of popularity (#7 in the final chart), so it may well pass “Cornerstone’s” record. Additionally, where “Cornerstone” only ever reached as high as #3, “What A Beautiful Name”, as mentioned, achieved #1 for two consecutive reporting periods.

All of that being said, Cornerstone, the album (Hillsong Worship 2012), represented a moment of significant shift for Hillsong. Darlene Zschech, as the long-standing worship pastor, iconic worship leader, and songwriter, left Hillsong Church in 2011, as she and her husband Mark went to take on the senior leadership of their own church (Hope UC) on the Central Coast of New South Wales, Australia. Additionally, Hillsong had only recently shifted its distribution agreement from Integrity Music to Capital CMG in 2010 (Baker et al. 2024), and as mentioned, Hillsong NYC had just launched, creating a new level of Hillsong’s presence in the USA. In the midst of such significant changes, “Cornerstone” was released. One of the obvious reasons for its success over other Hillsong CCS was its origins as a re-write of the c.1834 hymn, “My Hope Is Built On Nothing Less” by Edward Mote. Chris Tomlin’s “Amazing Grace (My Chains Are Gone)”5 had already demonstrated the potential gains from re-writing—and thus, freshly copyrighting—a well-known and well-loved hymn into the CCS style. Unlike that example, “Cornerstone” utilized new melody and harmony for the verses, of which only the first, second, and fourth were employed, while the writers completely re-wrote the iconic refrain of the original (“On Christ the solid rock I stand, all other ground is sinking sand…”) (Thornton 2021b, p. 173).

“Who You Say I Am” was the Hillsong CCS with the third highest longevity, appearing on 11 reports. It was Hillsong’s second most recent song (“King of Kings” being the most recent), from the 2018 album There Is More (Hillsong Worship 2018), which might lead one to expect it has a future beyond the parameters of this study. However, despite its currency, it had already fallen out of the Top 25 by the final report in this dataset. It is possible that this is related to the larger issues plaguing Hillsong towards the end of this period, as I will explore below.

From the April 2014 report through to April 2022 (8 years), Hillsong had an average of five songs in every report, with a maximum of seven (October 2014) and a minimum of four (October 2017, October 2018, April 2019, October 2020). In other words, Hillsong consistently accounted for 20% of the CCLI Top 25 charts, not just for those eight years, but for at least a decade before this study period as well. However, in the final report for this study (October 2023), only two Hillsong CCS remained, “What A Beautiful Name” and “King Of Kings”. “What A Beautiful Name” was released on Hillsong’s 2016 album Let There Be Light (Hillsong Worship 2016), and “King Of Kings” was released on Hillsong’s Awake album (Hillsong Worship 2019). While Hillsong released several albums after this, they were predominantly covers of previous releases, and any original songs were not widely picked up by churches for use in corporate musical worship. It seems the momentum of Hillsong Worship had already stagnated at the latest by 2019, just before the events I outlined earlier in this article. As such, not only were new Hillsong songs not being introduced post-2019, but some earlier songs, such as “Who You Say I Am”, also suffered during the general decreasing momentum of Hillsong from 2020 onwards.

On the topic of albums (rather than individual songs), Hillsong has been one of the most prolific and consistent producers for over 30 years. From 1992–2022, Hillsong released annual ‘live’ worship albums. In addition to this, Hillsong United produced almost yearly albums from 1999–2023. Hillsong Young & Free also produced regular releases from 2013–2022, and this is apart from other Hillsong releases, such as Hillsong Chapel and Hillsong Kids. Given such an impressive output (no other single church-based producer comes close to this), and the prominence of the church, it might be unsurprising that at least some of their songs would end up in CCLI’s Top 25. What is interesting to note, however, is that no more than one song from a given Hillsong live worship album within the study period ever made it into the Top 25 (see Table 1). In other words, out of the 14 or so songs on any given album, which represents only just over half of the new songs taught to Hillsong Church in a given year, which itself represents only a small portion of the songs submitted to Hillsong Music for consideration, only one song captured the church-at-large. Through that lens, Hillsong, once established, was playing a numbers game, and even then, not every album is represented. The profound success of “Mighty To Save”, from the album of the same name, was not followed up in any of the next three albums, Saviour King (Hillsong Worship 2007), This Is Our God (Hillsong Worship 2008), or Faith + Hope + Love (Hillsong Worship 2009). Additionally, God is Able (Hillsong Worship 2011) and Glorious Ruins (Hillsong Worship 2013) are not represented in the table below. Songs from these albums reached the Top 25 of the Australian charts and some other countries, but not the USA. The 2017 album The Peace Project is also missing (Hillsong Worship 2017), but is a unique case because it was a Christmas album. One of the things that CCLI data does not capture well is the seasonal nature of certain songs, because although, for example, Christmas songs may dominate for a few weeks in December, the reported use of those songs still does not equate to the reported use of the songs in the other five months of the reporting period.

Table 1.

Hillsong CCS in the dataset, Album, and Release Year.

As for Hillsong United, despite their considerable output, only two songs attained a Top 25 status; “The Stand” and “Oceans (Where Feet May Fail)”. Hillsong Young & Free faired even poorer with just one song, “Alive”, from their first album, We Are Young & Free (Hillsong Young & Free 2013). However, this is not particularly surprising given the younger demographic targeted by Young & Free. EDM-oriented CCS have a limited scope of use across the breadth of churches with CCLI licenses. First, they are harder to reproduce without tracks or expertise and resources for the subgenre, and second, they are stylistically more polarizing than the dominant musical landscape of CCS.

Hillsong’s studio album Awake, rather than the traditional live worship album, was followed by a covers album Take Heart (Again) in 2020 (Hillsong Worship 2020). These Same Skies (Hillsong Worship 2021) and Team Night (Hillsong Worship 2022) were the last live albums from Hillsong Worship. None of their respective songs were picked up by enough churches for them to appear in the Top 25 CCL lists of the next couple of years. Numerous factors likely contributed to this. First, as mentioned above, Hillsong’s ‘scandals’ were gaining media attention, which some churches wanted to distance themselves from, and their only tie was predominantly through music. Ironically, such a move would have made little impact for many non-music-oriented congregants, given they would be unaware of who wrote/produced most of the songs they sing in services anyway. Second, this album was the first to be recorded entirely in the USA. Because of this, the typical buzz around the live worship recording events in Australia and the anticipated release from those outside Hillsong church was lost to some degree. Third was the significant effect of COVID-19. The lockdowns associated with this period substantially limited the promotional opportunities normally applied to Hillsong releases.

Critical acclaim took a while to come to Hillsong Music, but when it finally did in the last half of the 2010s, it was both impressive and short-lived. Hillsong’s albums had been nominated at the Gospel Music Association’s Dove Awards for the “Worship Album of the Year” as early as 2000 with Shout to the Lord 2000. However, it took until 2015 for them to win the title with the album No Other Name (Hillsong Worship 2014) (from which “This I Believe (The Creed)” is in the dataset). Hillsong United won it the following year with Empires (Hillsong United 2015), although none of the songs on that album reached CCLI’s Top 25. Three years later (2019), Hillsong United did it again with People (Live) (Hillsong United 2019), but like Empires, none of the songs reached the Top 25. Finally, in 2020, Hillsong Worship had its second and last win in this category with the album Awake (Hillsong Worship 2020), which, as mentioned, also contained the last Hillsong song to appear in the USA CCL charts, “King of Kings”.

The GMA Dove Awards “Song of the Year” also reflects Hillsong’s prominence in the CCS genre in that period, despite the category not being limited to songs for the purpose of musical worship. “Oceans (Where Feet May Fail)” won the accolade in 2014, and “What A Beautiful Name” won in 2017. The more specific category of “Worship (Recorded) Song of the Year” has also come to Hillsong multiple times; in 2009 with “Mighty To Save”, 2014 “Oceans (Where Feet May Fail)”, 2017 “What A Beautiful Name”, 2018 “So Will I (100 Billion X)”6, and 2019 “Who You Say I Am”. “What A Beautiful Name” also won the Grammy for “Best Contemporary Christian Music Performance/Song” in 2018. There is some conjecture over the degree to which such awards impact the success of individual songs in CCLI charts. However, if causation was clear, “So Will I (100 Billion X)” should have reached the Top 25 list, which it did not. Whether correlation or causation, the accolades mostly confirm that these songs/albums had already deeply connected with a diverse array of local congregations across the USA, and indeed around the world.

There are both commonalities and exceptions in these eleven songs, which is as one would expect where a song needs to both feel immediately comfortable for the worship team and congregation, but must also stand out in some way, setting itself apart from the mass of CCS vying for a local church’s attention. These songs already have the possibility of standing out simply due to the prominence of their producer. As discussed, twenty years before the start of this dataset, Hillsong were writing, recording, and releasing CCS that consistently resonated with local churches and individual Christians. Their track record automatically means that many Christians/local churches are already positively pre-disposed towards future releases from Hillsong (Baker et al. 2023). However, why these specific songs? There were at least 12 other songs on each of the eleven albums represented that might have connected more with local churches.

Lyrically, for songs to register in the Top 25, they must resonate with a diverse range of Christian denominations and expressions. Songs in the Top 25 about the Holy Spirit are exceptionally rare, which is reflective of the differing views of the Holy Spirit’s nature and function in the life of the 21st-century believer. I had wondered whether songs that replicate or incorporate some of the strophic elements of traditional hymns (for example, multiple verbose verses) are more easily adopted by churches with historically traditional forms of worship. Indeed, “O Praise The Name (Anástasis)”, “King Of Kings”, and “Alive” each have four verses. However, five of the songs only have two verses. CCS have progressively become wordier over the past few decades (Thornton 2021b, p. 146), but even then, the second most recent song, “Who You Say I Am”, had the fourth lowest word count (124), after “The Stand” (114), “Mighty To Save” (103), and “Cornerstone” (100). Whether as a whole, songs were wordy or simple, without fail, the chorus sections of all of these songs are simple and singable, often utilizing a relatively small vocal range for the melody with a simple, repetitive rhythm. There is a clear distinction between these and, for example, “So Will I (100 Billion X)”, which not only has wordy verses, but three different wordy choruses.

As for other lyrical qualities, six of the songs utilize both singular (I, me, my) and plural (we, us, our) points of view (POV), while five songs use only singular personal pronouns. Cowan found a decreasing use of plural personal pronouns in his study of Hillsong in 2017 (Cowan 2017), and asked the question as to whether the decrease was “intentional or happenstance” (Cowan 2017, p. 94). I am unable to answer that question, however, the songs churches chose to appropriate from Hillsong utilize both singular and plural pronouns and, to a slightly lesser degree, just singular personal pronouns.

Four songs only address God with second-person pronouns (You, Your), six use both second- and third-person (He, Him, His) pronouns, and one song (“Cornerstone”) uses only third-person pronouns. Neither of these metrics give us any indication as to why these particular songs would stand out from the rest. In terms of the balance of focus between the worshiper and the One worshiped, songs span a range from “What A Beautiful name’s” 0.162 (six worshiper references to 37 Godhead references) to “Who You Say I Am’s” 1.5 (24 worshiper references to 16 Godhead references). In the wider corpus, these represent extreme positions of the most sung CCS (Thornton 2021b, p. 165). Six songs have a primary category of Praise/Thanksgiving, while three are primarily Worship, and two are Prophetic/Declarative. Once again, these qualities are fairly consistent with the genre as a whole (Thornton 2021b, pp. 161–62). There are two songs that contain no first person of the Godhead title (“Cornerstone” and “Oceans (Where Feet May Fail)”). There are four songs that reference the third person of the Godhead (“King of Kings”, “This I Believe (The Creed)”, “Oceans (Where Feet May Fail)”, and “The Stand”), and all songs reference Jesus (second person of the Godhead) in some way.

Given that none of the lyrical qualities above appear to distinguish these songs from the genre at large, it is worth considering the specific poetic qualities employed in each song’s lyrics. Metaphors and analogies abound in these songs, and many of them are central to the song’s identity. Some examples include:

“Spirit lead me where my trust is without borders, let me walk upon the waters, wherever You would call me”(“Oceans (Where Feet May Fail”))

“Death could not hold You, the veil tore before You, You silence the boast of sin and grave”(“What A Beautiful Name”)

“In the darkness we were waiting, without hope, without light, till from heaven You came running, there was mercy in Your eyes”(“King of Kings”)

“I’m running to Your arms”(“Forever Reign”)

“O trampled death, where is your sting? The angels roar for Christ the King”(“O Praise The Name(Anástasis)”)

It is not that other CCS lack poetic language; in fact, it is one of the qualities that helps distinguish songs when so many other elements—for example, harmony, melody, and instrumentation—are often quite banal (Thornton 2021b, p. 130). The immediate example of “Reckless Love”7 springs to mind in terms of poetic language that, while polarizing to worshippers, also provided a fresh way to express what was in the hearts of (some) worshippers (Thornton 2021a). However, Hillsong writers have consistently managed to capture words/phrases people want to sing, poetic language that resonates with individual believers at both a theological and personal level.

Two elements of theology stand out in these songs. First, all eleven songs include descriptions of the atoning work of Jesus on the Cross. Sometimes it is a whole verse, sometimes just a line, but the Saviour, salvation, and its implications to the believer are central to these songs. This finding is consistent with Cowan’s study (Cowan 2017, p. 97). Second, with only one exception (“Who You Say I Am”), some aspect of the resurrection features in every song, which is also consistent with Cowan’s findings (Cowan 2017, p. 93). Even then, “Who You Say I Am” features lyrics about Christians’ eternal home, which is linked to Christ’s resurrection and second coming. Given that these are central tenets of almost all Christian traditions, it is perhaps unsurprising that these songs should feature in the CCLI charts.

As mentioned, musical elements constitute little distinction between these songs and the corpus (whether Hillsong’s or the wider genre). As such, it seems that some combination of musical, lyrical, and extra-musical elements all contributed to bringing these particular songs to prominence. One final thought: CCS are utilized for musical worship in local church congregations. As such, one should not underestimate the spiritual component (as difficult to measure as it might be) that contributes to these songs succeeding as they have. Some sense of the emotional and spiritual impact of these songs can be gleaned in the comments left by individuals in the YouTube mediations of these songs, which I have written of elsewhere (Thornton and Evans 2015).

5. Synthesis and Conclusions

The ramifications of Hillsong’s decreasing presence in the contemporary worship sphere have been the opportunity for other CCS writers, artists, and producers to come to the fore. In particular, Elevation Worship (based out of Elevation Church, Charlotte, North Carolina) has had the greatest increase in prominence. Before 2020, they had had some initial success with songs such as “O Come To The Altar” (from their fifth live worship album Here As In Heaven (Elevation Worship 2016)), and “Do It Again” (from their sixth live worship album, There Is A Cloud (Elevation Worship 2017)). In March 2020, at the time when many countries began implementing Covid-19 lockdown measures, Elevation released “The Blessing” on YouTube.8 The timing of this release, the absence of Hillsong, and the existing prominence of Kari Job provided a nexus that propelled this song to become a global anthem during the pandemic, with notable national ‘lockdown’ covers being done in the UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and many others, including a version done by over 10,000 singers across 154 countries in 257 different languages.9 “The Blessing” featured almost immediately on CCLI Top Songs charts, debuting at #11 (April 2020), then falling to #19 in the October 2020 chart, and not appearing after that. For such an enormously popular song at the time, its longevity has not reflected its prominence. A likely explanation for this is the fact that this song, in particular, came to be associated with Covid-19 lockdowns; thus, when restrictions were finally lifted, the song had been overdone in online/streamed services and the post-COVID-19 environment sought new songs to help define the broader changes affecting both the local church and individual congregants.

A week after “The Blessing” was released on YouTube, Elevation released another CCS, this time featuring Brandon Lake, “Graves Into Gardens”, all from the same Graves Into Gardens album (Elevation Worship 2020). This song demonstrated longevity that “The Blessing” could not, continuing in the Top 25 all the way through to the last dataset in this study (October, 2023). This also provided prominence to Brandon Lake that he had not had before. Building upon this, Brandon’s “Gratitude” from his 2020 album House of Miracles (Lake 2020), which was also released as a single in 2022, quickly gained momentum on the CCLI charts, finishing in this dataset at #2. By the final report, Elevation had four songs on the list, whilst also arguably playing an important role in promoting other artists through their collaborations. One such group, which had already begun getting attention on their YouTube channel “TRIBL”, was Maverick City Music. From early on, Maverick City fostered collaborative worship recordings with artists such as Steffany Gretzinger, Brandon Lake, and Bri Babineaux. In 2021, Elevation Worship and Maverick City collaborated on The Old Church Basement album, and although none of those songs made it into CCLI’s Top 25, such collaborations propelled Maverick City into the congregational worship spaces already held by their collaborators. Finally, in 2022, a collaboration between Maverick City and Cody Carnes brought their first CCS to the Top 25, “Firm Foundation (He Won’t)”. It appeared at #19 on the October 2022 CCL report and rose to #4 by the end of this dataset. By that stage, Maverick City had another song reach the Top 25. “I Thank God” is a collaboration with UPPERROOM debuting at #20 in the April 2023 report, rising to #14 in the October 2023 report.

A couple of other artists have also broken into the charts in Hillsong’s absence. One is Charity Gayle with “I Speak Jesus” from her Endless Praise album (Gayle 2021). Another is David Brymer, with his (and co-writer Ryan Hall’s) song “Worthy Of It All”, which was originally released in 2012, but gained prominence through Bethel’s cover in 2018, and then CeCe Winans’ cover in 2021 on her “live worship experience” album Believe For It. Phil Wickham also increased his prominence in the CCL charts with the release of his album Hymn of Heaven in 2021 (Wickham 2021). “Battle Belongs” and “House of the Lord” both reached the Top 25, while his much earlier song “Living Hope” continued to stay in the Top 25 for the eleventh consecutive report.

What is clear from this analysis is that Hillsong’s prominence in the contemporary congregational song genre has waned, and in its place, new producers are emerging. In particular, Elevation Worship has filled a significant part of that gap, with Maverick City also gaining momentum, although neither to the degree that Hillsong once dominated the charts. Will Hillsong ever reclaim the musical territory they have lost in recent years? While ultimately no one can say for sure, it does seem that even if Hillsong re-entered the CCS market (and there have been recent indications that they will), the competition has now increased, people have shifted their musical attention, and Hillsong’s momentum, which helped perpetuate their historical prominence, has all but disappeared. It reminds us that no matter how large or influential one producer/artist becomes, they still only have that prominence for a season. New generations emerge, which bring new sounds, new language, and new mediums to a genre. Ongoing study is required, and a larger dataset may confirm these findings or challenge them in some way. Nevertheless, while the CCS genre has been indelibly impacted by Hillsong, it will continue to evolve and renew itself as the church continues to exist and seek new ways to musically express their relationship with God and their worship of God.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in https://songselect.ccli.com/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Since mid-year 2024, CCLI collects data and pays royalties accordingly based on quarterly reports. |

| 2 | Words and music by Darlene Zschech ©1993 Wondrous Worship. |

| 3 | Words and music by Rick Founds ©1989 Universal Music–Brentwood Bensen Publishing. |

| 4 | Words and music by Henry Smith ©1978 Integrity’s Hosanna! Music. |

| 5 | Words and music by Chris Tomlin, John Newton, and Louie Giglio ©2006 Rising Springs Music|Vamos Publishing|worshiptogether.com songs. |

| 6 | Words and music by Joel Houston, Benjamin Hastings, and Michael fatkin ©2017 Hillsong Music Publishing Australia. |

| 7 | Words and music by Cory Asbury, Caleb Culver and Ran Jackson ©2017 Richmond Park Publishing|Bethel Music Publishing|Cory Asbury Publishing|Watershet Worship Publishing. |

| 8 | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zp6aygmvzM4 (accessed on 1 November 2024). |

| 9 | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d48-qbcovVY (accessed on 1 November 2024). |

References

- Austin, Denise A. 2018. ‘Flowing Together’: The Origins and Early Development of Hillsong Church within Assemblies of God in Australia. In The Hillsong Movement Examined: You Call Me Out Upon the Waters. softcover reprint of the original 1st ed. 2017 edition. Edited by Tanya Riches and Tom Wagner. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 20–38. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Shannan, Elias Dummer, Marc Jolicoeur, Adam Perez, and Mike Tapper. 2023. Raising The Invisible Hand-How Brands and Social Proof Shape Our Sunday Setlists. Worship Leader Research (blog). October 6. Available online: https://worshipleaderresearch.com/raising-the-invisible-hand/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Baker, Shannan, Elias Dummer, Marc Jolicoeur, Adam Perez, and Mike Tapper. 2024. Following The Worship Money. Worship Leader Research (blog). November 7. Available online: https://worshipleaderresearch.com/following-the-worship-money/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Cowan, Nelson. 2017. ‘Heaven and Earth Collide’: Hillsong Music’s Evolving Theological Emphases. Pneuma 39: 78–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elevation Worship. 2016. Here As In Heaven, Essential Records, CD.

- Elevation Worship. 2017. There Is A Cloud, Essential Records, CD.

- Elevation Worship. 2020. Graves Into Gardens. Essential Records, Spotify. Available online: https://open.spotify.com/album/3obyvHd0Ja2gZaPQMerTU6?si=EoJWJS4WTgCrTgM86NOafw (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Evans, Mark. 2006. Open Up the Doors: Music in the Modern Church. London: Equinox Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Gayle, Charity. 2021. Endless Praise (Live). The Fuel Music, Spotify. Available online: https://open.spotify.com/album/0ZY2I6RVGv7a75Fus8Y447?si=Kq5rUDBfSgefz3wB2OpKPA (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Hillsong Steps into a Mission-Focused Future. 2023. Available online: https://hillsong.com/newsroom/blog/2023/02/hillsong-steps-into-a-mission-focused-future/ (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Hillsong United. 2006. United We Stand, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong United. 2013. Zion, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong United. 2015. Empires, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong United. 2019. People (Live). Hillsong Music, Spotify. Available online: https://open.spotify.com/album/3bMPLTN3fYcLAO2DJwPoBK?si=0f54b525b9064455 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Hillsong Worship. 2006. Mighty To Save, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong Worship. 2007. Saviour King, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong Worship. 2008. This Is Our God, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong Worship. 2009. Faith + Hope + Love, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong Worship. 2010. A Beautiful Exchange, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong Worship. 2011. God Is Able, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong Worship. 2012. Cornerstone, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong Worship. 2013. Glorious Ruins, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong Worship. 2014. No Other Name, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong Worship. 2015. Open HeavenRiver Wild, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong Worship. 2016. Let There Be Light, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong Worship. 2017. The Peace Project, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong Worship. 2018. There Is More, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Hillsong Worship. 2019. Awake. Hillsong Music, Spotify. Available online: https://open.spotify.com/album/19yNOXDt9RzLmAU2j9YnML?si=Bt3ueso8RfW0A-nCYSMIBw (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Hillsong Worship. 2020. Take Heart (Again). Hillsong Music, Spotify. Available online: https://open.spotify.com/album/4cIDrAPIwTqFLPcdMT16L4?si=Mnpv3n1HTEiyf2cbpDxCtg (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Hillsong Worship. 2021. These Same Skies. Hillsong Music, Spotify. Available online: https://open.spotify.com/album/162JpkoDVC2fowwp1pQ912?si=srcQXeUiTV6NNf3wcevKRA (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Hillsong Worship. 2022. Team Night. Hillsong Music, Spotify. Available online: https://open.spotify.com/album/0osCfQyLu2q9i47DBlzEKl?si=ed7t5o14TU2338MLapqFMA (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Hillsong Young & Free. 2013. We Are Young & Free, Hillsong Music, CD.

- Ingalls, Monique. 2018. Singing the Congregation: How Contemporary Worship Music Forms Evangelical Community. New York: Oxford University Press. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Singing-Congregation-Contemporary-Evangelical-Community-ebook/dp/B07HB4YW38/ref=sr_1_13?keywords=ethnomusicology+religion&qid=1560749325&s=books&sr=1-13 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Lake, Brandon. 2020. House of Miracles. Bethel Music, Spotify. Available online: https://open.spotify.com/album/4rPYrJInxyCcYiUHC8P0qD?si=n35FU8yFR8eOFq1famcd-Q (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Mall, Andrew, Jeffers Engelhardt, and Monique M. Ingalls, eds. 2021. Studying Congregational Music: Key Issues, Methods, and Theoretical Perspectives, 1st ed. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Martí, Gerardo. 2018. The Global Phenomenon of Hillsong Church: An Initial Assessment1. Sociology of Religion 78: 377–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, Dulcie A. Dixon, Pauline E. Muir, and Monique M. Ingalls, eds. 2024. Black British Gospel Music: From the Windrush Generation to Black Lives Matter, 1st ed. Abingdon and Oxon New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Myrick, Nathan. 2022. Ethics and Christian Musicking. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nekola, Anna, and Tom Wagner, eds. 2015. Congregational Music-Making and Community in a Mediated Age. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Reagan, Wen. 2018. ‘The Music That Just About Everyone Sings’: Hillsong in American Evangelical Media. In The Hillsong Movement Examined: You Call Me Out Upon the Waters. softcover reprint of the original 1st ed. 2017 edition. Edited by Tanya Riches and Tom Wagner. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 144–61. [Google Scholar]

- Riches, Tanya, and Tom Wagner, eds. 2018. The Hillsong Movement Examined: You Call Me Out Upon the Waters. softcover reprint of the original 1st ed. 2017 edition. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, Cristina. 2023. Cool Christianity: Hillsong and the Fashioning of Cosmopolitan Identities. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steuernagel, Marcell Silva. 2021. Church Music Through the Lens of Performance. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, Daniel. 2016. Exploring the Contemporary Congregational Song Genre: Texts, Practice, and Industry. Doctoral dissertation, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, Daniel. 2017. On Hillsong’s Continued Reign over the Australian Contemporary Congregational Song Genre. Perfect Beat 17: 164–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, Daniel. 2021a. A ‘Sloppy Wet Kiss’? Intralingual Translation and Meaning-Making in Contemporary Congregational Songs. Religions 12: 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, Daniel. 2021b. Meaning-Making in the Contemporary Congregational Song Genre. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, Daniel. 2023. ‘This Is No Performance’: Exploring the Complicated Relationship between the Church and Contemporary Congregational Songs. Religions 14: 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, Daniel, and Mark Evans. 2015. YouTube: A New Mediator of Christian Community. In Congregational Music-Making and Community in a Mediated Age. Edited by Tom Wagner and Anna Nekola. London: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., pp. 141–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Thomas J. 2013. Hearing The Hillsong Sound: Music, Marketing, Meaning and Branded Spiritual Experience at a Transnational Megachurch. Doctoral dissertation, Royal Holloway University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Walrath, Brian, and Robert Woods, eds. 2010. The Message in the Music: Studying Contemporary Praise and Worship. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, Phil. 2021. Hymn of Heaven. Fair Trade Services, Spotify. Available online: https://open.spotify.com/album/1dTtexFzU6mWBjAi391OO1?si=9_ThDvi7Q1GtcStkQX5zsg (accessed on 1 November 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).