Abstract

In a country where almost the totality of the native population is baptized and raised in the Catholic Church, recent surveys have shown several inconsistencies, especially among the young who claim that they do not believe. This study is a follow-up of another one that showed marked differences between the younger generation and older ones regarding the importance of religion in their life. Other surveys gave a similar picture. This study seeks to acquire a deeper understanding of the religiosity of these adolescents and young adults, this time with the use of two validated instruments. The first, the Meaning and Purpose Scales (MAPS), was meant to capture the essence of religion as a meaning-making mode. For the second, since the majority of the participants came from an organized religion, it was worth investigating the reasons why these adolescents were abandoning their religion and where they were going. This was attempted through the administration of the Adolescent Deconversion Scale (ADS). In addition, to detect deconversion-related changes, the participants were asked to undertake the Retrospective Analysis of Religiosity, a graphical method representing their religious development over the years by the plotting of a “religiosity line”. Following a number of contrasts between the test variables and others from the demographic information, a more defined and detailed picture of the religiosity of this segment of the population emerged. The absolute majority of the participants continue to profess their religion, and faith continues to be a major source of meaning in their life. In addition, there is a strong correlation between their personal sense of security and religion and the family, particularly for two-parent families. This study exposed a particular critical point in their religious journey, marking the beginning of a decline in their religion. This also coincides with the major developmental changes that take place during puberty. For the rest, perseverance in the faith journey was very strongly related to having participated for a number of years in a faith group. The family of origin and, later, belonging to a faith group seem to be decisive factors in the transmission and preservation of religiosity. As for those who left religion, the main reasons differed, including existential quests, peer influence, or simply indifference. Most, however, do not seem to have migrated to another religion or sect, and there are signs that many of them might have retained their own personal spirituality privately. Finally, it could be argued that, for some, their religious journey might not be over yet.

1. Introduction

In a previous study conducted during the partial lockdown of 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was hypothesized that such an extraordinary event could have had an impact on the religiosity and faith of the people, as well as on their sense of existence. For this reason, it was deemed worth investigating whether or not faith had really helped them to cope with this dramatic situation. The study was conducted in the island state of Malta, where the majority of people are baptized and raised in the Roman Catholic Church, and which hosts one of the most religiously observant populations in Europe (Galea et al. 2023). In the course of that survey, 88% of respondents declared themselves to be Roman Catholic. However, the picture was quite different for those under the age of 30. While 72% of the young declared themselves to be Catholic, only 36% considered themselves to be religious. The number of those claiming to have no religion increased as the ages went down.

As to the central question of whether or not faith had helped as they went through the stress caused by the pandemic, only 28% of the younger group said that it had, which is much lower than the average of the rest (62%). These findings show a trend of detachment from the religion in which they were born and raised. The results also showed that age, more than the other variables, was the most significant factor. Other studies conducted among youths from the same population gave a similar picture.

One indicator that is often used when studying religion is that of church attendance. While this could be a strong and tangible sign of belief, the opposite is not always the case. However, this was particularly problematic during the COVID-19 lockdown, when worship in presence was put on hold and many went through a forced break. While the shift to online worshipping compensated for this, it posed a serious question as to whether church attendance would be resumed once the pandemic was over.

In order to understand the significance of church attendance in a global perspective, one could refer to the World Values Survey (WVS), which has data for 36 countries with large Catholic populations (Centre for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) 2024). Weekly or more frequent mass attendance is highest among adult self-identified Catholics. Although Malta was not included in this survey, relying on local data, the rate stands at 68%. This places it in fourth place compared with other countries. For the youngest group (16–30), however, the rate drops to 49%. Since religious attendance in Malta is evidently still high, measuring religiousness through these practices might still be a significant gauge, despite the limitations.

The rapid secularization trend, especially among the young, is a widespread phenomenon. A Pew Research Center study (released 10 September 2020) reported data related to American teens that seem to resonate with data from other Western countries (Pew Research Centre 2020). Though most American teens share religious identities and faith practices with their parents, they are much less likely to say that religion is very important to them than their parents. While most of these teens identify with a religion, the researchers found that they are more likely than their parents to identify as “nones” or unaffiliated. Similar results can be found in Europe. A recent study in Germany highlighted a profound change characterized by the constant diminution of the importance of faith in God among Christian young people, especially among Catholics (Meisner Hertz 2024).

One important question is whether this secularization trend among the youngest generation is irreversible. Despite the signs in the results, the Pew study is not categorical about this. Is it possible that these adolescents will ultimately be equally or more religious than current young adults? This survey neither supports nor contradicts such a hypothesis. In fact, previous research had suggested that much of the movement away from religion among young adults occurs after they come of age, move out of their childhood homes, or otherwise gain a measure of independence from their parents (Melissa et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2017; Bengston et al. 2015). This pattern seems to fit a psychological model of religious and spiritual development that points to a post-adolescence trend toward autonomy (Rydz 2014; Arnett Jensen and Arnett Jensen 2002). Of equal importance are developmental changes, such as the relationships among self- and moral cognition, emotion, and behavior as they are gradually integrated during adolescence (Lapsley and Narvez 2013).

As people enter early adulthood, a large decline—particularly in the public aspects of religion, such as religious service participation—takes place, whereas more private aspects of religion, such as prayer and the personal importance of religion, decline more moderately (Uecker et al. 2007). In short, religion seems to vary across the life course, often declining in late adolescence and early adulthood, and then increasing as people age, form new relationships, start their own families, and mature into later adulthood. This seems to have been the case with the baby boomers. Reasons for this could include a shift away from worldly concerns, coping with loss and health problems, and intergenerational continuity (Silverstein and Bengston 2018). An updated summary on the religious and spiritual development in adolescence, young adulthood, and beyond can be found in the study of Hardy and Taylor (2024).

2. Charting the Territory: Belief, Religion and Spirituality

“What do we understand by belief?”, “How is one to define the term religion?”, and “How to define the term spirituality?” According to Paloutzian and Park (2013, p. 72), the process of believing can be understood within a meaning systems framework. Believing is a process by which our perceptual–cognitive–emotive systems construct an idea from bits and pieces of information such that the whole is sufficient to convince ourselves of its validity. A “belief” is what exists in the human mind once meaning-making processes have produced something that is relatively stable. Beliefs are meanings made (Paloutzian 2017, p. 72), but they are neither fixed nor static. Hence, the focus is more on the processes of believing than on “belief” itself. In this sense, it is of secondary importance whether belief is labeled as religious, spiritual, or secular (Seitz and Angel 2015). Likewise, there is no contradiction between a scientific explanation of someone’s belief and a religious explanation, despite the fact that they are very different. Finally, believing is ultimately personal and subjective.

Religions are complex, diverse, and are found in every culture. For this reason, it is very difficult to find a consensus on a definition of religion. In order to be as inclusive as possible, religion should be understood as a generalized, abstract orientation through which people see the world, and which defines their reality, provides meaning, and claims a degree of allegiance and commitment. An example of an integrating concept in the understanding of religiousness is that proposed by Saroglou (2011). A person who is religious in the complete sense is involved in the processes of believing, bonding, behaving, and belonging. All of these processes have their own cultural variations.

Most of the research in the area of religiousness takes a static and contrasting approach, such as between belief and unbelief, or between religiosity and atheism/agnosticism. In reality, these positions tend to be more dynamic and with possible overlaps. In other words, atheism and agnosticism can be seen more as processes than as fixed positions. People who leave their faith can be in the process of a developmental change—a migration in the religious field that may eventually lead to their exiting the religious domain altogether and moving towards atheism. This highlights the importance of knowing the motivations and the predictors of their stance toward religion, along with the effects of these decisions. This was the work undertaken by H. Streib and his colleagues at the University of Bielefeld in Germany, in a project called Deconversion. This was further extended to the USA with the collaboration of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, and with the contribution of scholars like R. Hood (Streib et al. 2009).

2.1. Deconversion Trajectories as Migrations in the Religious Field

Religious deconversion can be defined as any movement away from religion (Hardy and Longo 2021). In many ways, it is the opposite of religious conversion (Paloutzian and Park 2013). Religious deconversion is a general term capturing religious disaffiliation and religious de-identification. In recent years, several models have emerged, illustrating an increased interest in this area in different parts of the world (Hardy and Taylor 2014).

According to Streib, there are five criteria to identify deconversion: (1) loss of religious experience, (2) intellectual doubt, (3) moral criticism, (4) emotional suffering, and (5) disaffiliation from the community (Streib et al. 2009, p. 22). In the Deconversion project, specific trajectories were considered to follow the following options: (1) secularizing exit: termination of (concern with) religious belief and praxis; termination of membership in organized religion; (2) oppositional exit: adopting a different belief system of, or engaging in different ritual praxis in or affiliation with, a higher-tension, more oppositional religious organization, which could mean conversion into a fundamentalist or new religious group; (3) integrating exit: adopting a different belief system of, or engaging in different ritual praxis in or affiliation with, an integrated or more accommodated religious organization; (4) privatizing exit: termination of membership, but continuity of private religious belief and private religious praxis; this is what is meant by “invisible religion” (Luckmann 2022); (5) heretical exit: individual heretical appropriation of new belief system(s) or engagement in different religious praxis (syncretistic, invisible religion, spiritual quest) without new organizational affiliation (Streib et al. 2009, pp. 26–28).

The first four of these deconversion trajectories can be understood within the framework of the (traditional) religious field, with church and sect as the most powerful actors in competition for the affiliation of lay people. Secular exiters could be expected to leave the religious field, oppositional and integrating exiters migrate between churches and sects, and religious switchers move between churches with a similar degree of integration.

Worthy of consideration is the role of the family as a predictor of religious deconversion. There is plenty of evidence to show the family as the most salient and proximal context for religious development (Hardy et al. 2019). Furthermore, the links among lower parent worship service attendance, lower parent religious importance, and fewer religious conversations in adolescence are so strong that they can be taken as predictors of later religious de-identification (Hardy et al. 2022). The link between parent or family religiosity and religious deconversion also seems to hold across European cultures, and particularly in Catholic countries such as Poland (Łysiak et al. 2020).

2.2. The Psychological Perspective: Conceptualization of Meaning and Purpose

Meaning in life is multidimensional. It encompasses different qualities of meaning, such as meaningfulness, crisis of meaning, or existential indifference, as well as the sources from which people draw meaning or purpose. For both research and practice, it is of high value to know not only the extent of meaningfulness, or its absence, but also its sources. This is precisely what is captured by the Meaning and Purpose Scales (MAPS) (Schnell and Danbolt 2023). The development of the MAPS items was guided by the qualitative basis that preceded it, the Sources of Meaning and Meaning in Life Questionnaire (the SoMe) (Schnell 2009), and by the literature on facets of meaningfulness.

Meaningfulness is a basic sense that life is worth living. This is very relevant in studying religion as a meaning-making mode. Current psychological research suggests that it is represented by the following facets: significance/mattering, coherence/comprehension, direction/orientation, and belonging, the latter understood in a philosophical sense.

According to this instrument, the existential concept of belonging refers to the sense of having a place in this world, or “dwelling”, as Heidegger would call it. “Where one dwells, is where one is at home, where one has a place… (By dwelling, our being) is located within a set of sense-making practices and structures with which one is familiar.” This is perhaps best rendered by the German word Heimat.

3. Research Questions

- The central focus of this study was to explore how this group of adolescents and young adults position themselves on the MAPS questionnaire regarding religious belief, understood as a meaning-making mode, and how it correlates with the construct of meaningfulness and with the other subscales.

- Secondly, through a series of contrasts between the MAPS questionnaire and other demographic variables, we aimed to explore any significant connections that could shed more light on the nature of religious belief specific to this population.

- Thirdly, presuming that there are people who exit from religion, we sought to investigate them by applying the categories and parameters of the deconversion theory through the use of the ADS.

- Fourthly, through a series of contrasts between the ADS and other variables, we aimed to explore the category of exiters in depth, to understand their reasons for leaving their religion, and to establish their current standing with regards to existential issues.

4. Methodology

To collect this information, and to be in conformity with the provisions of the GDPR, it was decided to employ an anonymous online questionnaire open to all persons between 16 and 30 years of age. This questionnaire was intended to gather data about the religious affiliation of the participants, together with a self-assessment of how they consider themselves with regards to religion and religiosity. In addition to the questions related to demography, it included two validated instruments, the MAPS and the ADS. At a second stage, the participants were asked to trace their religiosity over time according to their age using another instrument, the RAR. Furthermore, in the event of having exited from religion, they were asked to trace their routes.

The participants were chosen randomly through mailshots sent to students and to the technical, administrative, and academic staff of the University of Malta and the Junior College. The questionnaire was sent online by email and was posted openly on social media. The questionnaire was made available for 15 days between 9 October 2024 and 24 October 2024. During this period, 276 (97.5%) valid replies were recorded. These data were then transposed onto the IBM SPSS v. 29 program for further analysis and contrasts.1 While speed and anonymity are two major advantages of online questionnaires, one must acknowledge the drawback that only those who have access to the internet can be reached.

4.1. The Questionnaire

The questionnaire was made up of 95 items divided into different sections. The demographic part contained 18 questions. This was followed by a section where the participants had to rate their religious experience within their family.2

The next part consisted of The Meaning and Purpose Scales, with 23 questions (Schnell and Danbolt 2023), and the Retrospective Analysis of Religiosity (Płużek 2002). In this short exercise, the participants were asked to rate their religiosity for every year, starting from when they were 7 to date, with the maximum age being 30. This was followed by the Adolescent Deconversion Scale (Nowosielski and Bartczuk 2019), which consisted of 27 questions. The final section had 15 items with questions inspired by the literature on the subject, and which sought to investigate the exit routes taken in more detail. The questions included elements specific to the local culture.

4.2. The Instruments

4.2.1. The Meaning and Purpose Scales (MAPS)

The MAPS provide a valid assessment of two qualities of meaning—meaningfulness, and crisis of meaning—and five sources of purpose: (1) sustainability, (2) faith, (3) security, (4) community, and (5) personal growth. The Meaning and Purpose Scales (MAPS) use a six-point Likert scale from 0 (do not agree at all) to 5 (agree completely) for the following constructs:

Meaningfulness—The basic sense that life is worth living, based on the evaluation of one’s life as directed, coherent, belonging, and significant (5 items; Cronbach’s α = 0.89; sample items: “My life is meaningful”; “I feel connected to this world”).

Crisis of meaning—A judgement on one’s life as frustratingly empty, pointless, and lacking meaning (3 items; Cronbach’s α = 0.89; sample items: “I am missing meaning in my life”; “My life seems empty to me”).

Sustainability—A sense of connectedness with all forms of life and concern for a future worth living (3 items; Cronbach’s α = 0.79; sample items: “I base my actions on leaving a world worth living in for the next generations”; “I experience a strong connection with all living beings on earth”).

Faith—A sense of connectedness with transcendence and concern for a spiritual life (3 items; Cronbach’s α = 0.96; sample items: “I find strength through faith in God/a higher power”; “My everyday actions are guided by faith in God/s higher power”).

Security—A sense of connectedness with shared norms and concern for a secure life (3 items; Cronbach’s α = 0.74; sample items: “I always follow rules and regulations”; “When making decisions, I always go for the safe option”).

Community—A sense of connectedness with a familiar group and concern for each other (3 items; Cronbach’s α = 0.76; sample items: “I find it important to care for the well-being of the people around me”; “I enjoy spending time in community with other people”).

Personal growth—A sense of connectedness with oneself and concern for continuous learning (3 items; Cronbach’s α = 0.80; sample items: “I am constantly working to grow and develop personally”; “I set myself goals that encourage me to continue learning”).

4.2.2. The Adolescent Deconversion Scale (ADS)

The revised 27-item Adolescent Deconversion Scale (ADS) was used to measure the deconversion processes (Nowosielski and Bartczuk 2019). This inventory consists of five subscales: (1) withdrawal from the community, (2) abandoning faith, (3) moral criticism, (4) experiencing transcendental emptiness, and (5) deconversion behavior. The period that the participants considered when assessing the changes in their religiosity was set at the last 12 months. The ADS uses a four-point Likert scale from 0 (completely untrue about me) to 3 (very true about me) for the following constructs:

Withdrawal from the community —Indicates losing the bond with the current group of fellow believers (5 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.91; sample item: “The religious community (Church) is becoming less and less important to me”).

Abandoning faith —Indicates an intensification of doubts and thoughts of abandoning faith for agnosticism or atheism; (5 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.87; sample item: “I have begun to doubt that God exists”).

Moral criticism—Indicates a rejection of the moral principles taught by religion; (5 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.86; sample item: “I cease to understand why—according to religion—I cannot live the way I want to”).

Experiencing transcendental emptiness—Indicates an intensification of unpleasant emotional states, such as emptiness, a sense of rejection, and sorrow, as well as existential difficulties connected with religion; (5 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.78; sample item: “I have begun to experience emptiness in my religious life”).

Deconversion behavior—Indicates a gradual neglect or abandonment of religious activity.

(5 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.90; sample item: “I rarely attend religious/spiritual services”).

Total score for Deconversion, Cronbach’s α = 0.94.

According to the authors, deconversion processes of a social nature are more prevalent in adolescents during this particular period (Nowosielski and Bartczuk 2019, p. 351). This justified the addition of deconversion behavior as a sensitive indication of deconversion.

In addition to the ADS, other items related to the deconversion process were included in the questionnaire. These were derived mainly from the literature on the subject and were intended to explore which exit routes could have been taken by those who left religion. The different sets of statements also had a 4-point Likert scale from 0 to 3, ranging from “completely untrue about me” (0) to “very true about me” (3). These items addressed issues that were grouped and labeled as institutional dissatisfaction, personal quest, and socio-cultural expressions of religion.

The constructs personal quest and institutional dissatisfaction were inspired by the study of Van Tongeren (2024) on those who left religion. For these, the faith, practices, and institutions that once provided comfort and guidance no longer fit their beliefs and values. This shift, however, also comes with a price. While it can bring freedom, it also engenders a profound loss of meaning and purpose, as well as of community and identity.

4.2.3. Retrospective Analysis of Religiosity (RAR)

To detect deconversion-related changes, a graphical method based on the methodology proposed by Płużek (2002) was adopted. This took the form of a system of coordinates, in which the vertical axis corresponds to categories of religious commitment (“atheist”, “agnostic”, “nonreligious”, “indifferent”, “weakly religious”, “religious”, “very religious”) and the horizontal axis corresponds to chronological age. The participant draws a line on the chart to indicate the evolution of their religious commitment in the course of their life so far. A decline in the “religiosity line” indicates changes that involve a weakening of the experience and expression of religiosity. This method serves as an indicator of the presence of deconversion and can identify the critical moments in time when such changes take place.

5. Findings

5.1. Demographic Information

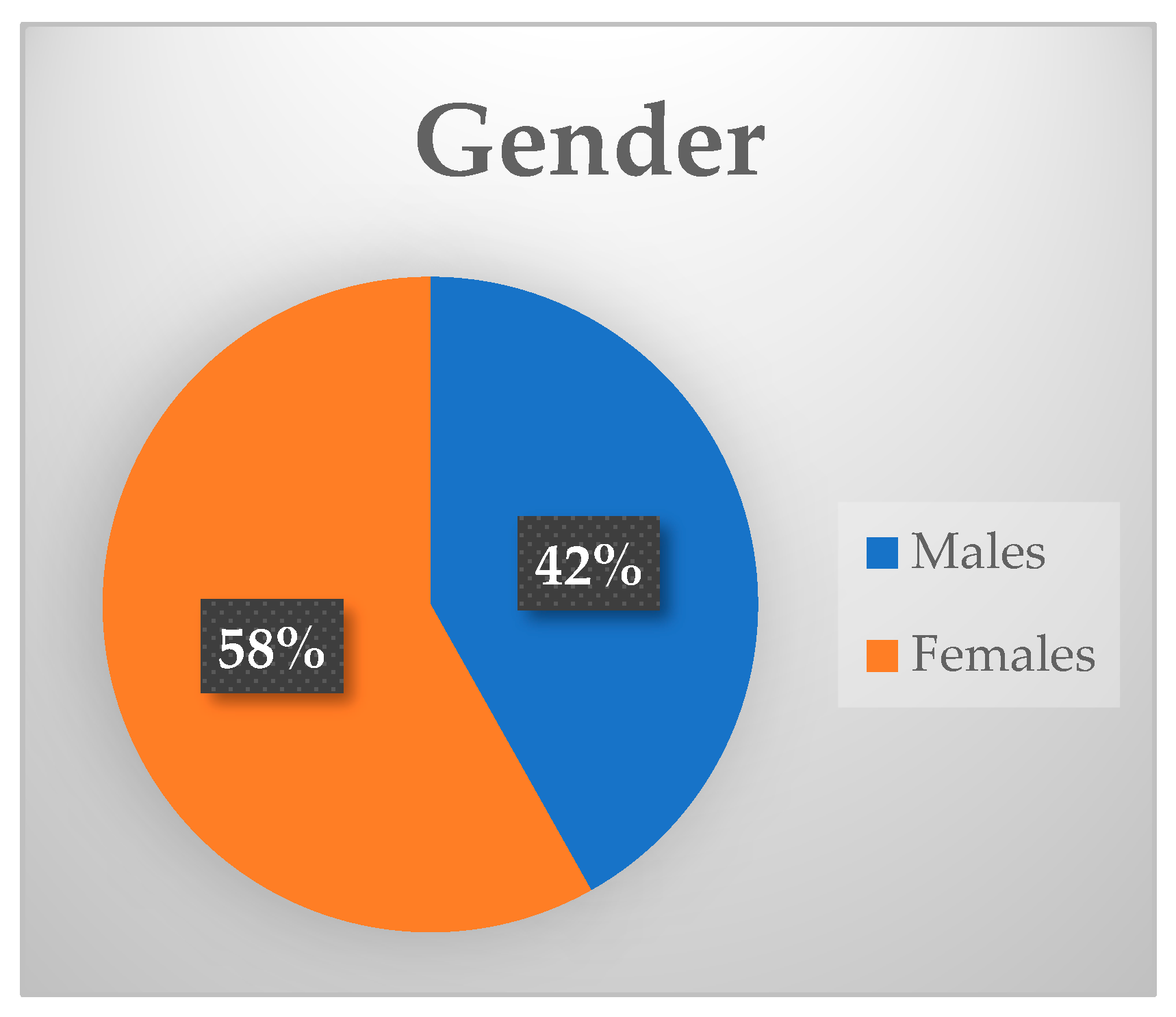

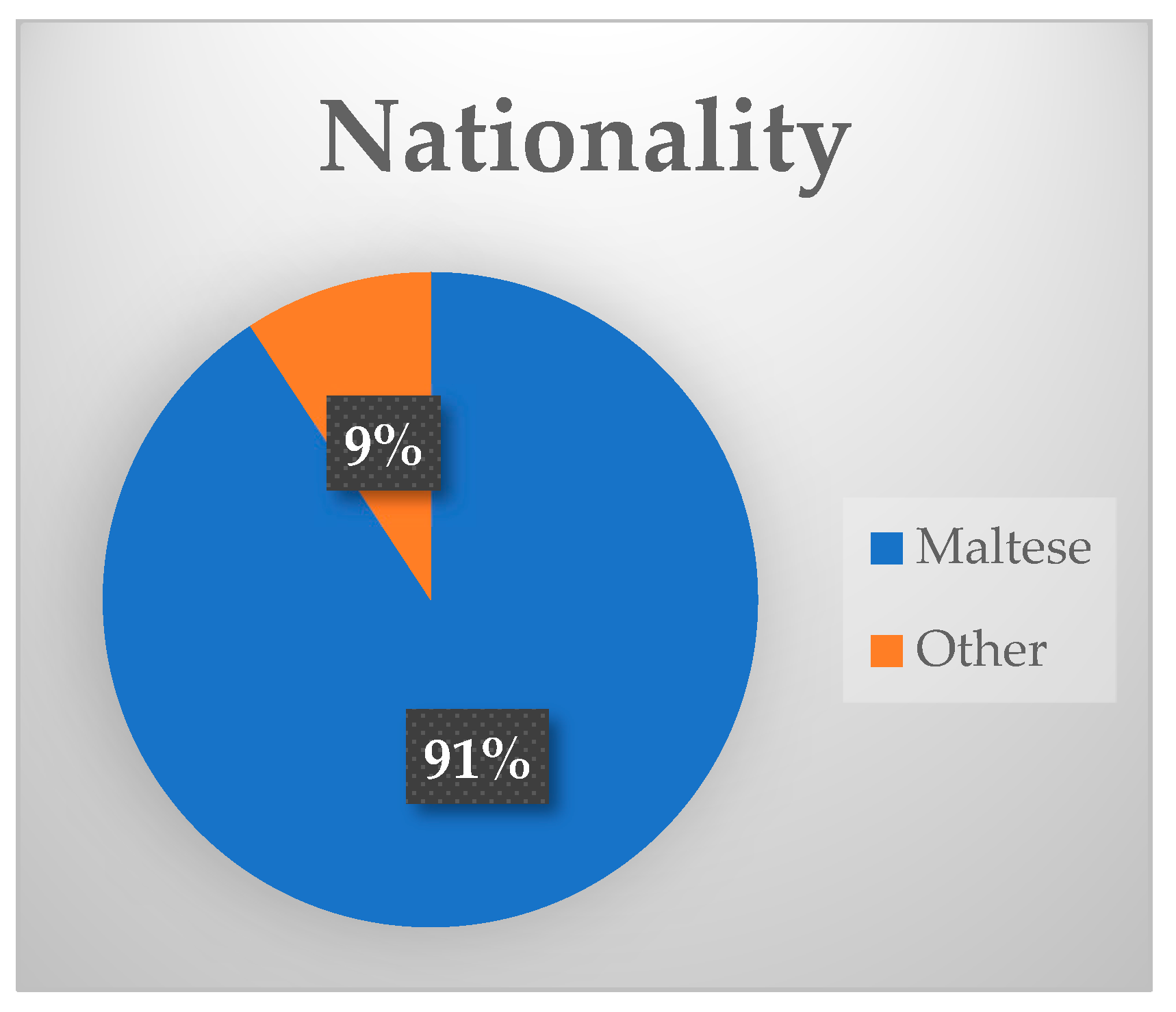

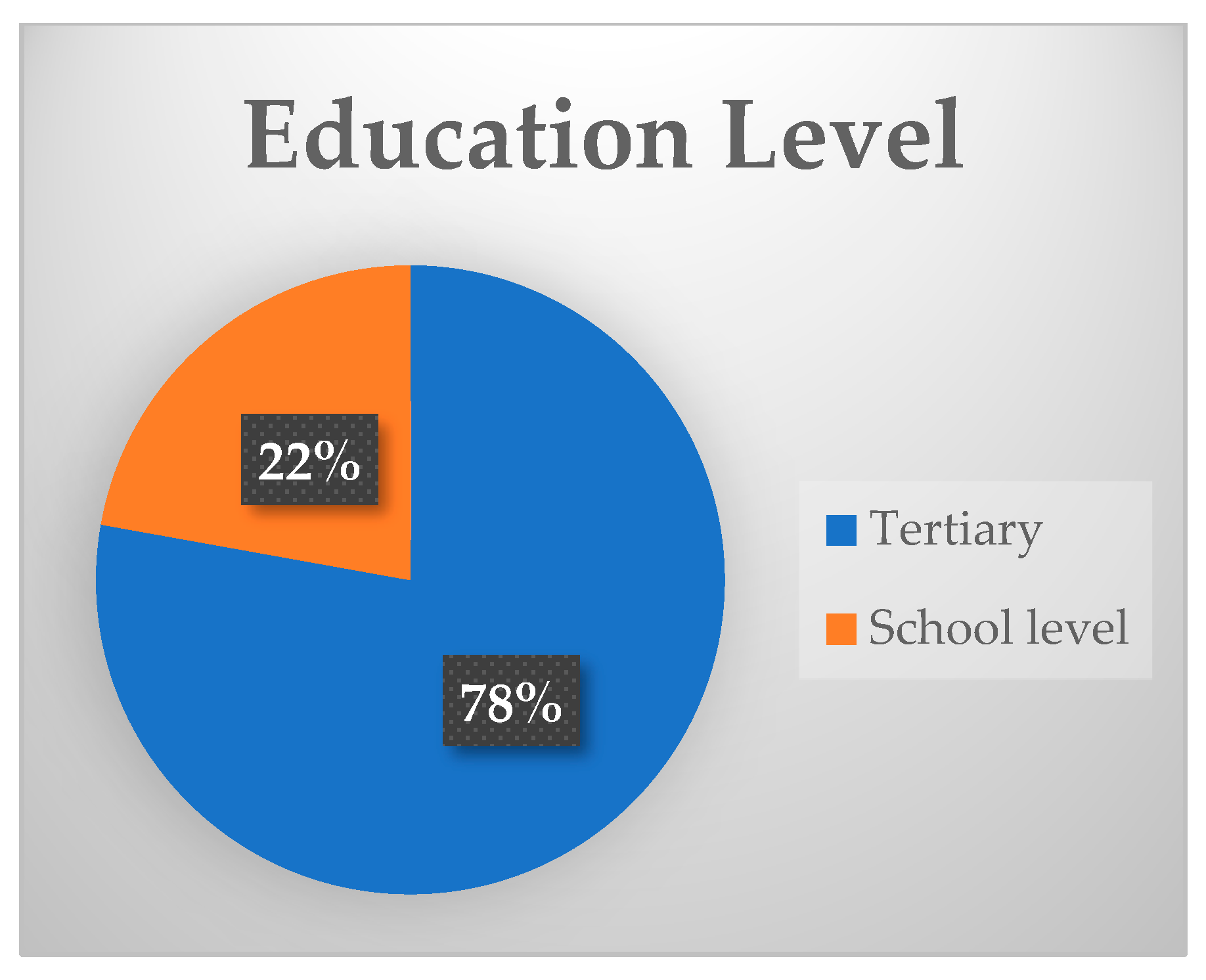

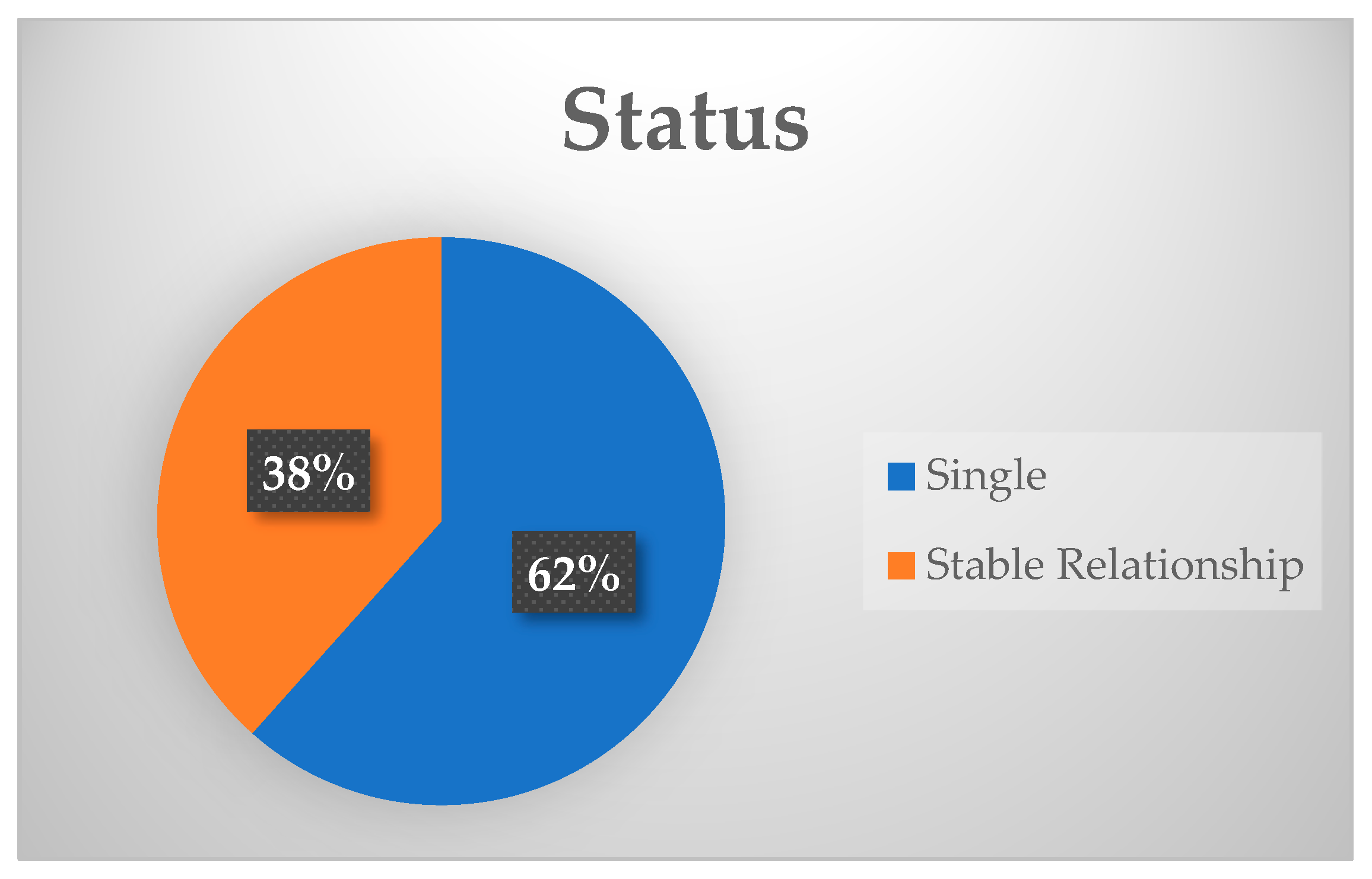

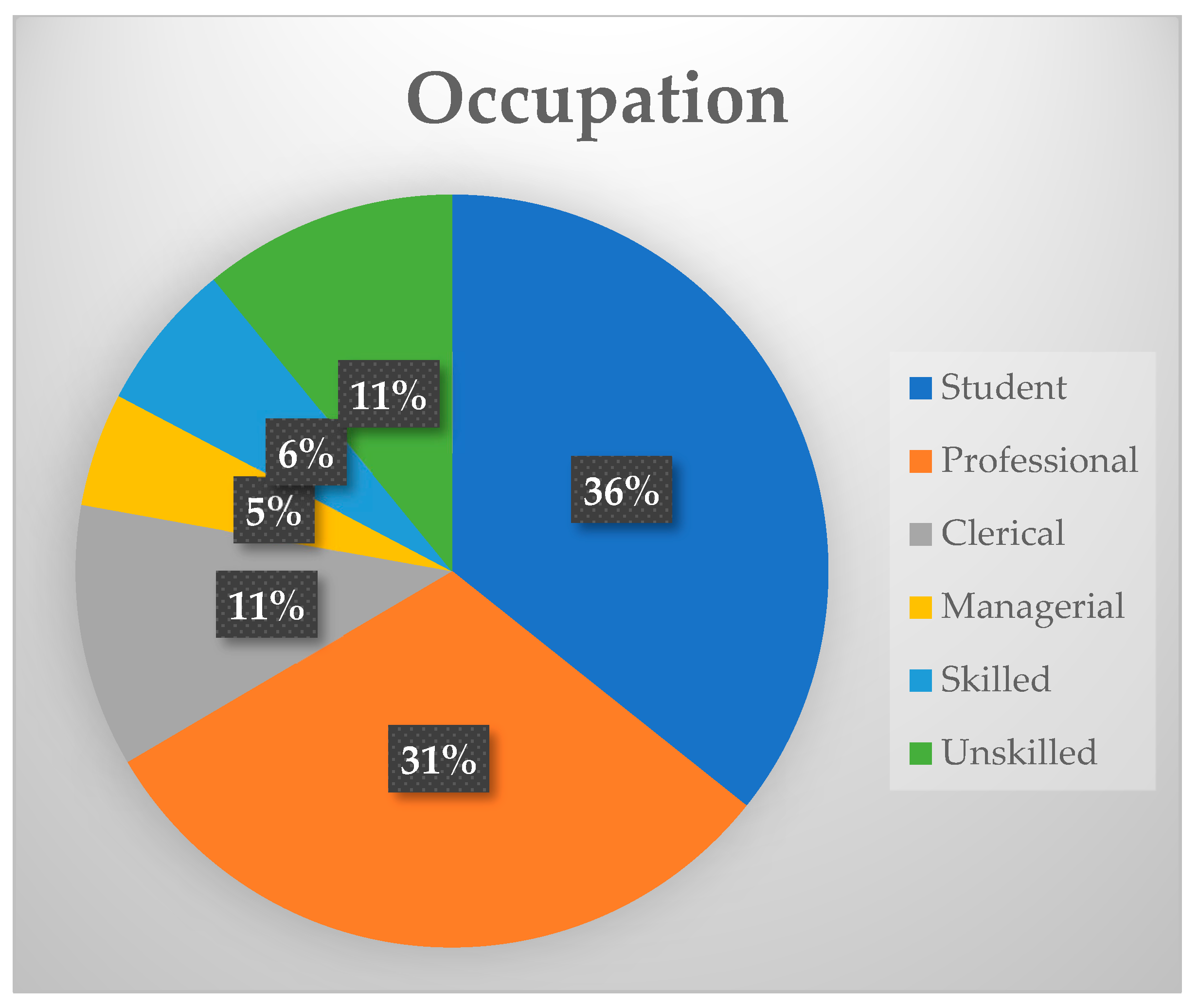

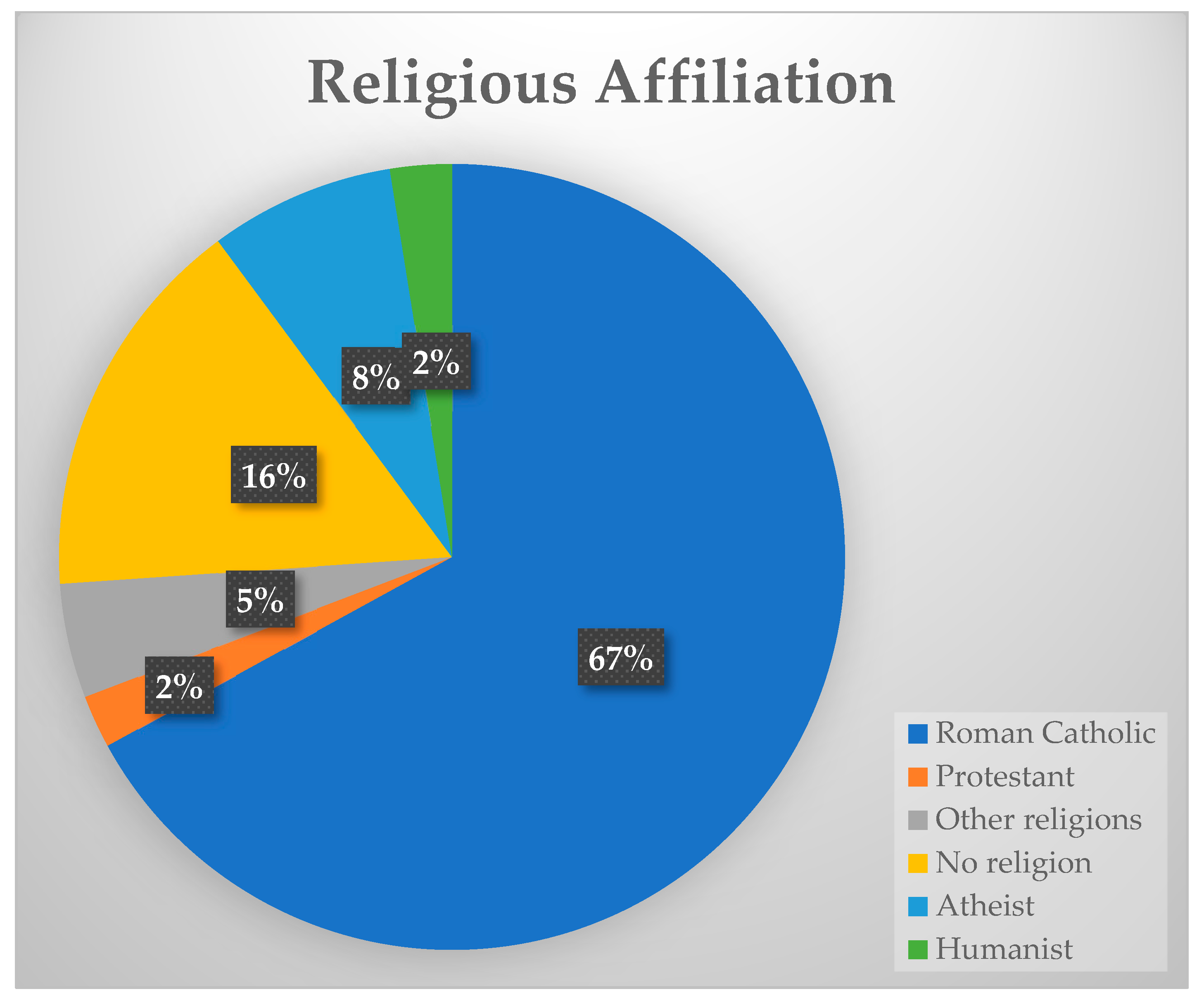

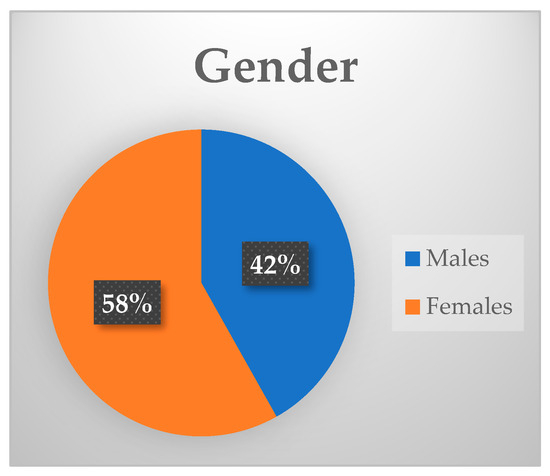

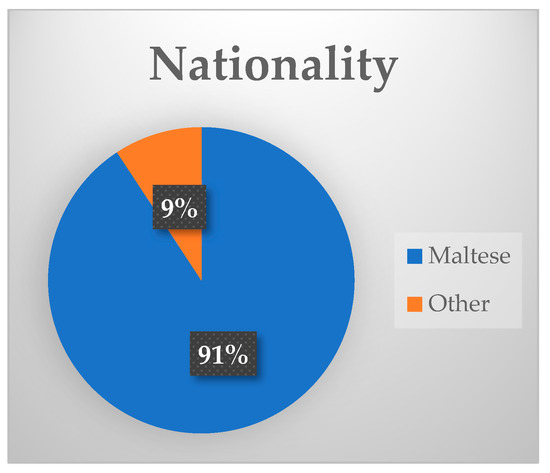

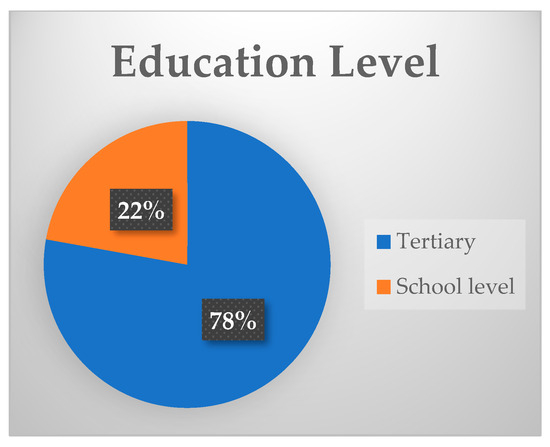

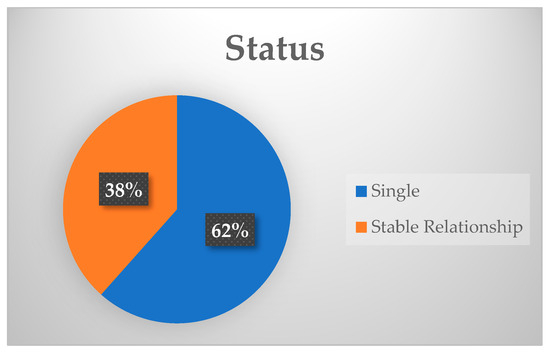

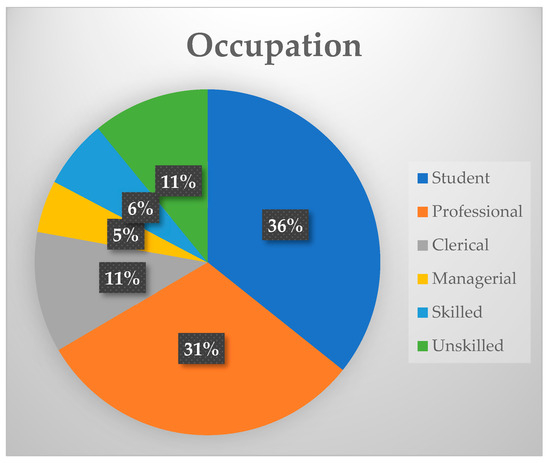

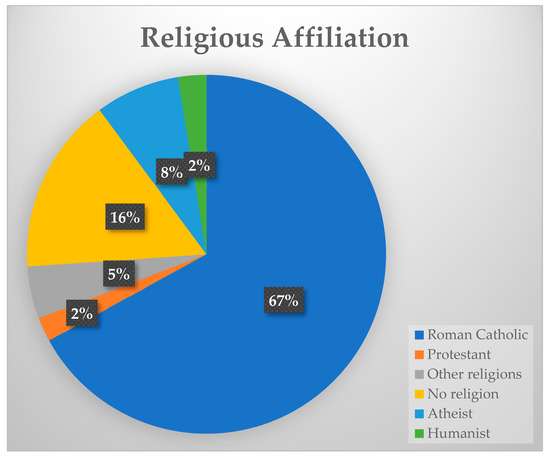

The response to this online survey was quite encouraging, as it drew 270 valid entries. Of these, 113 (42%) were males, and 157 (58%) were females (Chart 1). The majority of the participants were Maltese (245, 91%) (Chart 2). For the remaining participants belonging to other nationalities, the numbers were too scattered to make any comparisons. With regard to their education level, 214 (78%) had completed tertiary education. The remaining 61 participants (22%) had received a school-level education (Chart 3). Regarding their relationship status, 170 (562%) were single and 106 (38%) were in a stable relationship (Chart 4). As to their occupation, 95 (36%) were students, 82 (31%) worked at a professional level, 30 (11%) at a clerical level, 13 (5%) at a managerial level, 17 (6%) were skilled workers, and 29 (11%) were unskilled workers (Chart 5).

Chart 1.

Gender.

Chart 2.

Nationality.

Chart 3.

Education Level.

Chart 4.

Status.

Chart 5.

Occupation.

Looking at those who identified themselves as Roman Catholic (Chart 6), the numbers contrast sharply with those who reported having been baptized as Catholics (262, 91%), These latter figures are very similar to those who have gone through the customary rites of passage, such as First Communion (260, 90%) and Confirmation (253, 88%). When comparing the responses of those who identified themselves as Roman Catholic with the baptism figures, there is a discrepancy of 77 (27%). This could be a first indicator of the rate of disengagement from their religion of origin at the time of taking the survey.

Chart 6.

Religious Affiliation.

A similar picture can be seen with regards to those who had been educated in a church school (58%), those who had received further religious education after Confirmation (58%), and those who later became members of a religious group (57%). For half of these (49%), the average stay in such groups was between 2 and 8 years.

An important source of demographic information is that related to church attendance. There were 156 (54%) who attended regularly, albeit not with the same frequency. Some of these (135, 48%) attended regularly every week, or several times during the week. To these, one ought to add another 21 (7%) who attended every other week. The remaining 120 (42%) can be considered to be defaulters or disinterested, as they never attend (54, 19%) or do so very rarely (66, 23%).

Another important piece of information is that of the family background and the parents’ attitude towards religion. Most of the participants came from two-parent families (245, 85%). The majority also felt that home was a secure environment (230, 80%), with only 46 (16%) holding the opposite view. As to whether their parents cared about them, the results were similar, with 230 (80%) being in agreement.

The majority of the participants had Catholic parents, with 81% having a Catholic father, and 87% a Catholic mother. The remaining entries were scattered among different religions. Concerning their fathers’ attitudes towards religion, 34 (12%) rated him as very religious, 154 (54%) as weakly religious, and 36 (13%) as non-practicing. Regarding the mothers, 62 (22%) were rated as very religious, 118 (41%) as religious, and 35 (12%) as weakly religious. The remaining 31 (12%) were non-practicing. Adding the very religious to the religious—180 (63%) of the mothers and 34 (12%) of the fathers—the mothers were more religious than the fathers.

When the participants were asked whether their parents showed an interest in or talked about religion at home, 124 (43%) answered that this was very much the case, 67 (23%) said that it was true, and 73 (25%) said that it was somewhat true. This means that for 91% of the participants, religion was a topic of discussion at home, even though this did not necessarily result in a transmission of religious practice. The next section deals with the elaboration and interpretation of the results of the MAPS questionnaire.

5.2. The Results of the Meaning and Purpose Scales (MAPS)

The first step in the analysis of the MAPS questionnaire was to measure the Cronbach’s alphas for internal consistency between the related statements describing each subscale to check the reliability of the test, and to compare the scores with the original. Since all of the Cronbach’s alphas exceeded or were close to the 0.7 threshold, the results confirm its validity and compare well with the original.

Reliability Statistics for MAPS

Since all seven scales had skewed distributions, the Friedman test, a non-parametric test, was the best suited to compare the mean scores of the seven scales. The results of the analysis of variance showed a p-value of less than 0.05 (X2(6) = 507.952, p < 0.001). For this reason, it was assumed that the mean scores provided for the statements differed significantly. In fact, the mean scores for personal growth (4.12), community (3.99), meaningfulness (3.67), sustainability (3.51), and security (3.39) were significantly higher than the mean scores for crisis of meaning (1.21) and faith (2.81). In the first case, the interpretation is quite evident, in that meaningfulness and crisis of meaning are mutually contradictory. In the second case, faith came out as weakly related to the other factors, suggesting that it is somewhat independent of them. The next step was to explore these relationships through a correlation matrix, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Spearman correlation matrix for MAPS.

Crisis of meaning, as expected, was negatively related with all six of the other scales. Meaningfulness, sustainability, community, and personal growth were all positively related. Most of these relationships were significant, since their p-values were smaller than the 0.05 level and their r values were higher than 0.3. The highest correlation was a negative one, that between meaningfulness and crisis of meaning (r = −0.70 p < 0.001), confirming consistency in the results.

Regarding faith and security, although correlations with the other subscales were positive, these were rather weak. The correlation between the two was also moderate (r = 0.22 p < 0.001). The other correlations were stronger, such as those between meaningfulness and personal growth (r = 0.48 p < 0.001), between meaningfulness and sustainability (r = 0.31 p < 0.001), between meaningfulness and community (r = 0.31 p < 0.001), between sustainability and community (r = 0.30 p < 0.001), between sustainability and personal growth (r = 0.33 p < 0.001), and between personal growth and community (r = 0.34 p < 0.001).

In addition to measuring meaningfulness, the instrument taps into its sources. According to these results, most of the participants seemed to have a basic sense that life is worth living, and that meaning is related mostly to three sources: sustainability, community, and personal growth. As to the other subscales, faith is positively but very weakly correlated with meaningfulness (r = 0.19 p < 0.001). With regard to security, it seems to have no connection at all with meaningfulness. Once again, faith came out as somewhat independent.

The next step consisted of drawing comparisons between groups, clustered by demographic data and variables with a religious content, along with the mean scores provided to each scale. Since all of the p-values exceeded the 0.05 level of significance, the results of the Kruskal–Wallis test showed no significant discrepancy regarding gender, nationality, education level, and marital status.

Regarding occupation, unskilled workers scored significantly lower than their counterparts on faith (p < 0.04). No significant differences were noted for the remaining scales. Since the discriminating factor was neither education level nor having attended a church school, other contrasts were needed to answer this question. For this purpose, specific variables with a religious content were employed to make these contrasts.

Starting from religious belief, Christians scored significantly higher on faith (p < 0.001) and security (p < 0.007) than their counterparts. Individuals who had received Confirmation also scored significantly higher than their counterparts on the same variables (p < 0.01). Individuals practicing other religions, on the other hand, scored significantly higher on sustainability (p < 0.01). Atheists/humanists and individuals with no religion scored significantly lower on faith (p < 0.001) and community (p < 0.04). The remaining scales showed no significant differences between religious beliefs. These results suggest a stronger connection between Christians on the one hand and the faith, security, and community variables on the other.

Although, in the preceding set of contrasts, education level did not prove to be particularly significant, upon deeper analysis it emerged that those who had received further religious education after Confirmation, those who belonged to a religious group or movement, and those who attended church services regularly have fared quite differently. While those who received Confirmation scored high on faith and security, those who had received further religious education after Confirmation scored even higher on faith (p < 0.001). For the remaining scales, there were no significant differences between those who had received further religious education after Confirmation and those who had not. Similarly, individuals who were members of a religious group/movement scored significantly higher on faith (p < 0.001). Of significant importance here is church attendance. Individuals who attended church services regularly scored significantly higher on faith (p < 0.001), security (p < 0.015), and community (p < 0.044). In other words, furthering one’s religious education after Confirmation, belonging to a faith group/movement, and attending church regularly seem to make a difference when it comes to scoring on the faith construct of this instrument. However, since many of these religious factors are bidirectional, it is equally plausible that those with higher faith choose to engage more in religious education, seek Confirmation, and prioritize regular church attendance.

The other set of contrasts sought to explore whether there was a correlation between family background and faith. The results show that certain types of families seem to make a difference. Individuals who were brought up in a two-parent family scored significantly higher on faith than their counterparts (p < 0.026). For the remaining scales, there were no significant differences between those who were brought up in a one-parent or a two-parent family. Individuals whose father was Christian and whose attitude towards religion was positive scored significantly higher on faith (p < 0.001) and security (p < 0.008) than their counterparts. For the remaining scales, there were no significant differences between those whose father was Christian and those whose father practiced another religion. Similarly, individuals whose mother was Christian and who showed a positive attitude towards religion scored significantly higher on faith than their counterparts (p < 0.003). For the remaining scales, there were no significant differences. In other words, having stable two-parent families and having parents with a positive attitude towards religion were very closely related to faith and security.

By way of conclusion, it appears that faith and security are connected more with the family type than with meaningfulness or with any other construct in the MAPS. Faith and security are much more related to having a two-parent family and having parents who show a positive outlook towards religion. Similarly, a strong connection exists between faith and having received further religious education and with practicing religion, such as by attending church services. In other words, according to this study, meaningfulness, faith, and security are independent of each other. A more elaborate interpretation of these findings will be provided in the Discussion section.

5.3. The Results of the Adolescent Deconversion Scale (ADS)

The next stage was the analysis of the Adolescent Deconversion Scale (ADS) to study the other group of participants, who had fallen out of religion. The first step consisted of measuring the Cronbach’s alphas. Since all of these obtained a 0.9 score, exceeding the 0.7 threshold, a satisfactory internal consistency between the items was reached. These scores compare well with the original.

Reliability Statistics for ADS

The first step consisted of performing a set of comparisons between the mean scores on the five scales. The mean scores ranged from 0 to 3, where 0 corresponded to “completely untrue about me” and 3 corresponded to “very similar to me”. The mean scores of the five subscales ranged from 0.61 to 0.9, indicating that the majority of the participants considered these five negative aspects to be untrue about themselves. Since the p-value of the analysis of variance was smaller than the 0.05 level of significance (X2(4) = 50.83, p < 0.001), it was taken that, for the majority of the participants, experiencing transcendental emptiness, withdrawal from the community, and deconversion behavior were more likely to be untrue about them, as they did not identify with any of these positions. The Spearman correlation matrix furthermore showed that all five subscales were positively and significantly correlated with each other (Table 2).

Table 2.

Spearman correlation matrix for the ADS subscales.

The next stage was to compare the mean scores provided to each scale between groups of participants clustered by demographically related variables and other religion-related variables. The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test showed no significant differences among the five subscales and the other variables, except for the category of unskilled workers, who scored significantly higher than their counterparts on withdrawal from the community. Another significant result was that regarding individuals who spent no time, or less time, in a religious group or organization, and their performance on these scales. These individuals also scored significantly higher on withdrawal from the community and on transcendental emptiness experience than their counterparts who had spent 5 years or more in such groups or organizations. No significant discrepancy was found for the remaining four subscales. These results highlight the relevance of having spent a certain amount of time in a religious community or group during adolescence to experiencing a sense of community and transcendence. However, since these correlations are bidirectional, it could be the case that a lack of interest in joining in a community and a certain transcendental emptiness could have kept these people away.

Likewise, individuals who attend religious services regularly scored significantly lower on withdrawal from the community, abandoning faith, moral criticism, and deconversion behaviors than their counterparts who rarely attend or never do so. This highlights the strong and positive connection between practicing religion and the other factors associated with religion. No significant difference was found in transcendental emptiness experience between those who attend religious services regularly and those who do not, suggesting that people who do not attend religious practices do not necessarily experience transcendental emptiness.

5.4. Exit Routes

Cronbach’s alpha for the first set of three items dealing with the institutional dissatisfaction construct obtained a score of 0.88, showing good internal consistency. This construct tackles issues related to experiencing problems with the religious institution. A sample item would be “I left my religion because of the scandals by its leaders”. While there were 173 (60%) who disagreed with these statements, there were 103 (36%) who agreed. These figures will be revisited later, in that equal percentages related to exiters tend to come up repeatedly in the other contrasts.

The other construct, labeled personal quest, consisted of six items and was meant to gauge issues related to existential and faith problems. This yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.6, which is acceptable. A sample item would be “I left my religious organization and its religious services because I found other religious groups to be more radical”. However, only 30 (10%) individuals agreed with these statements, which means that only a small number of those who left their religion did so in order to join another religion. At the same time, there were 46 (16%) who left their religion under the influence of their friends and peers.

The other items sought to inquire about the respondents’ personal evaluation of their decision to leave. Many of these (95, 33%) confirmed that they were at peace with their decision to leave their religion. However, there were 77 (27%) who left their religion because it brought them no relief in their suffering. The last question addressed specifically to the exiters sought to inquire about the possibility of whether some day they might go back. To this, there were 93 (32%) who said that they did not exclude this possibility.

From these figures, it is possible to draw a rough estimate of those who have left their religion. This can be computed by averaging the numbers related to specific questions, and from demographic data. Table 3 shows in detail how the global average was reached.

Table 3.

Estimated numbers and percentages of exiters.

The number of youths who qualify as exiters or deconverts, as represented in this study, is in the range of 29%, or about one-third of the sample. This is comparable with what can be found in the literature, particularly that of the Pew Research Centre (2020), where about one-third, (32%) of the teens interviewed did not identify with the religious faith of their parents.

The final set of questions sought to acquire information about the participants’ appreciation of the local socio-cultural expressions of religion and how they personally relate to them. To the first statement, “Irrespective of my religious beliefs, I enjoy the socio-cultural expressions of religion through feasts and traditions”, the majority (198, 69%) answered positively. However, with reference to the other statement as to whether the ways feasts are being celebrated do more harm than good to religion, there was an almost equal number of persons (190, 66%) who agreed. When contrasting these two responses, one gets the impression that most of these young people tend to adopt a positive outlook on these socio-cultural expressions but may have some reservations as to their relevance to religion.

As in the previous sections, a Spearman correlation matrix was created to explore any significant connections. The results showed that institutional dissatisfaction and personal quest are positively and significantly related to each other (r = 0.64 p < 0.001). This means that individuals who experience institutional dissatisfaction tend also to grapple with issues of personal quest. These persons also enjoy the socio-cultural expressions of religion through feasts, and they support these traditions, even though the correlation between the two is somewhat weak (r = 0.20 p < 0.01). This raises the question of how much of these expressions is actually related to faith. To answer this question, another procedure was needed. This consisted of the comparison of the mean scores of the groups of participants clustered by demographic and religion-related variables. Because the distribution was not normal, a non-parametric test, the Kruskal–Wallis test, was used.

The results showed that Christians scored significantly higher on institutional dissatisfaction and personal quest than those belonging to other religions or those who identified themselves as atheists or humanists. This suggests that those who disengaged from a formal religious institution could still be contending with problems related to the institution—obviously more so than those who did not form part of it. At the same time, they also seem to be grappling with personal religious issues. This interpretation is very much in line with the rationale behind the deconversion theory, in that this term applies exclusively to those who have left an organized religion and not to those who are disengaged. This also resonates with the conclusions of Van Tongeren (2024) related to those who left their religion, in that leaving can bring freedom, but it can also engender a sense of loss.

On the other hand, individuals who attend religious services regularly scored significantly lower on institutional dissatisfaction, personal quest, and positive socio-cultural expressions than their counterparts who rarely or never do so. Church attendance has once again proved to be a very important discriminant factor. However, since the correlations are bidirectional, it is also possible that people who have no problems with these issues would favor church attendance.

Another variable used in the previous sections was also seen to be relevant in the following contrasts: membership in a religious organization. Individuals who spent no time or only a short time in a religious group or organization scored significantly higher on institutional dissatisfaction, personal quest, and socio-cultural expressions than their counterparts who spent more than ten years, or who were still members, in such organizations. Such was the case with individuals who continued to receive further religious education after Confirmation, who also scored significantly lower on institutional dissatisfaction than their counterparts. This once again highlights the relevance of belonging to a religious group or community during adolescence, as well as that of pursuing further religious education for the strengthening of one’s religion and sense of belonging.

Family background again emerged as a very important factor with regards to religion. Individuals whose father or mother did not practice any religion scored significantly higher on institutional dissatisfaction and personal quest than their counterparts. Likewise, individuals coming from a single-parent family scored significantly higher on personal quest and socio-cultural expressions than those from a two-parent family. Similarly, persons with a lower level of education tended to have a more positive attitude towards socio-cultural expressions than those with a higher level of education.

5.5. The Results of the Retrospective Analysis of Religiosity (RAR)

To rate deconversion related changes, a graphical method was used based on the methodology proposed by Płużek (2002). This took the form of a system of coordinates, in which the vertical axis corresponds to categories of religious commitment (“atheist”, “agnostic”, “nonreligious”, “indifferent”, “weakly religious”, “religious”, “very religious”) and the horizontal axis corresponds to age. The participant draws a line on the chart to indicate the evolution of their religious commitment in the course of their life, up to the time of taking the test. The following examples were chosen from the most significant contrasts: church attendance, family typology, belonging to a church group, and mother’s attitude to religion. A decline in the “religiosity line” indicates changes that involve a weakening of the experience and expression of religiosity.

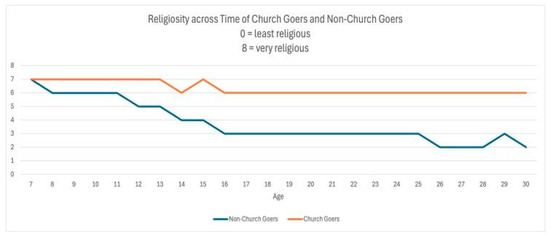

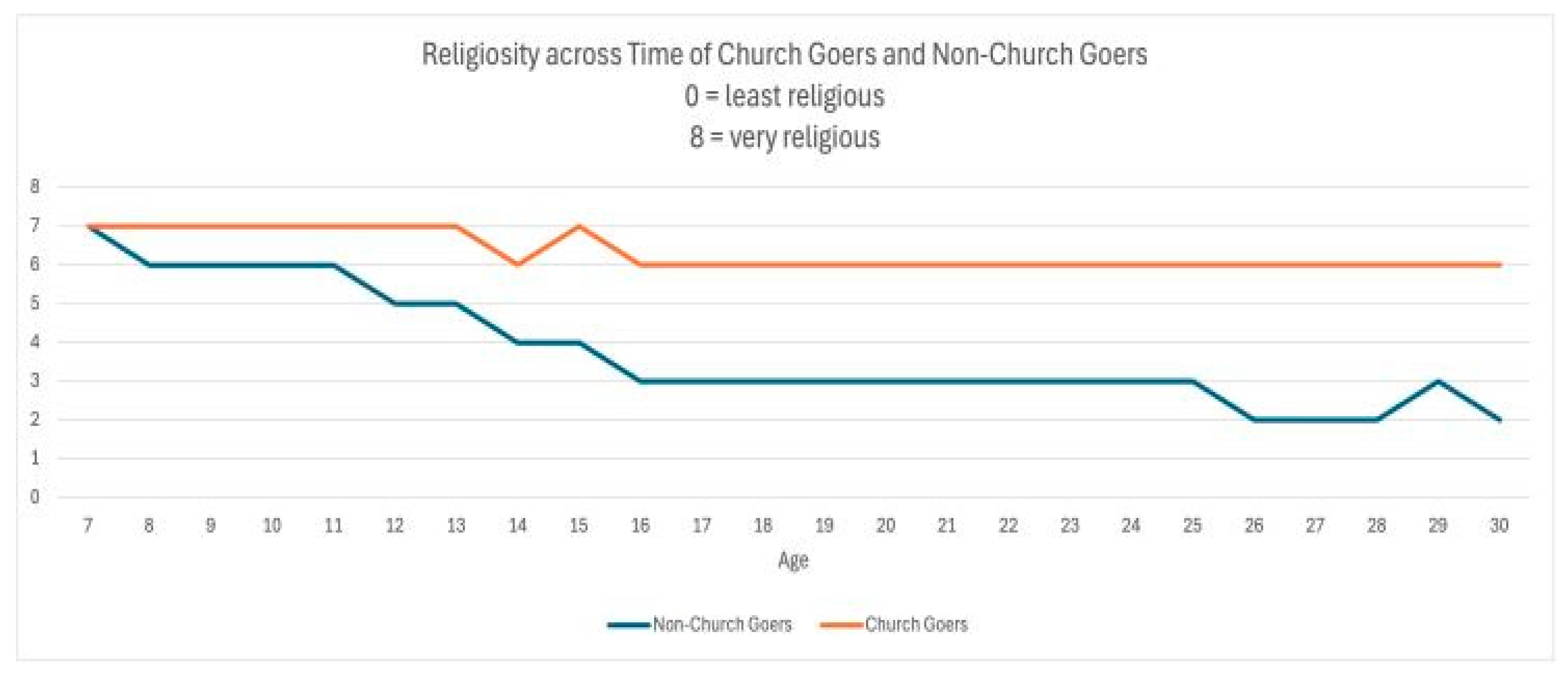

As seen in Graph 1, the religiosity lines of the two groups, the churchgoers and the non-churchgoers, follow a similar trajectory, the only difference being that the former starts on a higher level of religiosity, fluctuating around the age of 14, after which it remains stable. In the case of the non-churchgoers, religiosity starts at the same level and begins to drop in a progressive manner already from the age of 8, and further around the ages of 11/12, before then stabilizing at a low level at around the age of 16. Various interpretations are possible for such an early disinterest in religion. Perhaps the most plausible is the family, in that parents are technically still responsible for the education of their children at that age, including their religious education.

Graph 1.

Changes in Religiosity across Time of Church Goers and Non-Church Goers.

Graph 1.

Changes in Religiosity across Time of Church Goers and Non-Church Goers.

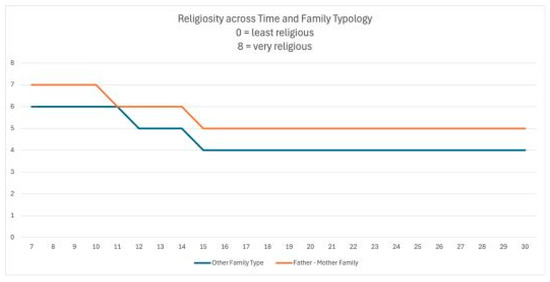

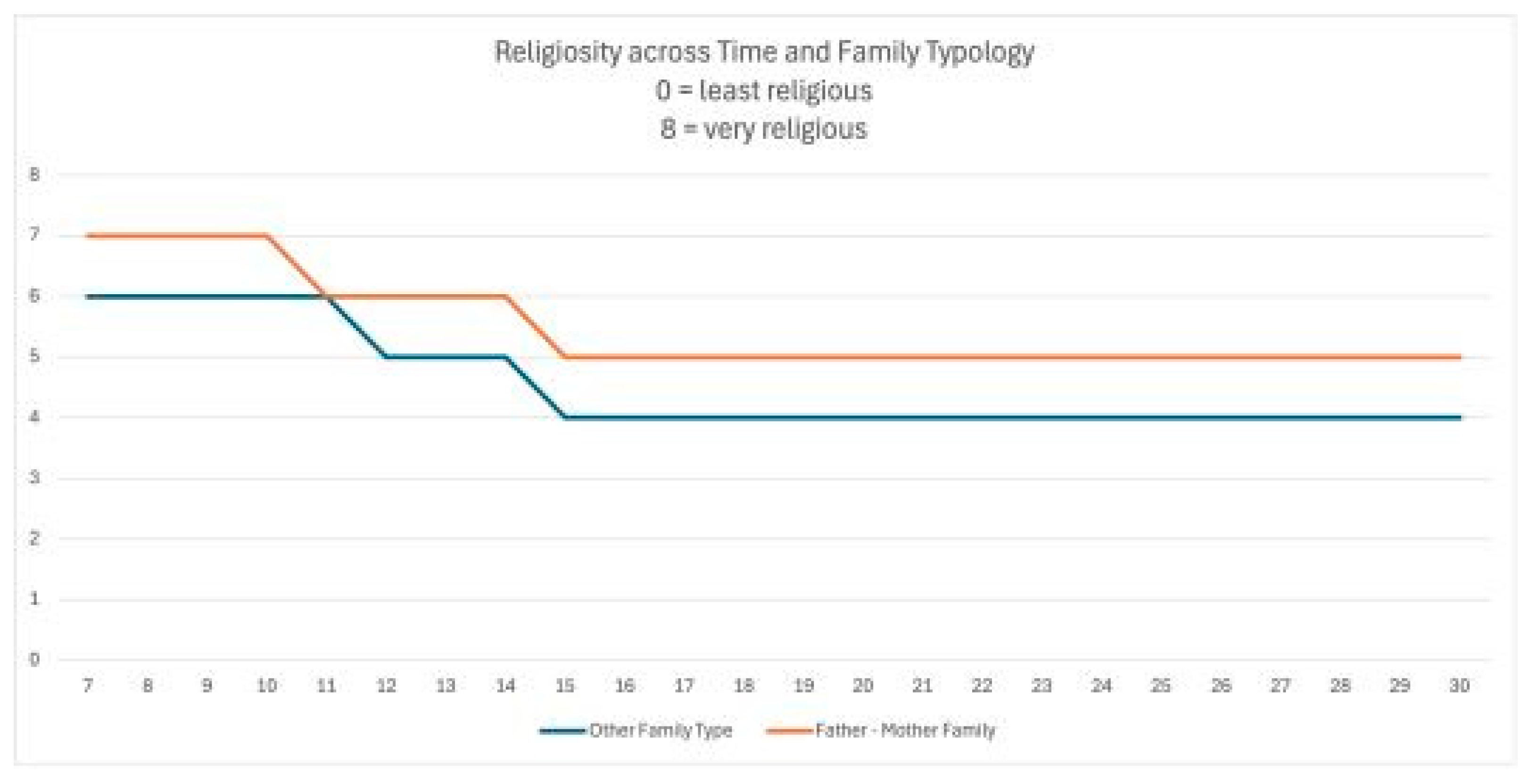

In the case of the family typology (Graph 2), the trajectories follow a similar pattern for those coming from a two-parent and from a one-parent family. The major difference is in the level of religiosity, which is higher for the former and is substantially retained throughout later years despite a decline in the “religiosity line”. In the case of two-parent families, it shifts from very religious to weakly religious. In the one-parent families, it starts as fairly religious and then faces a decline. The interpretation could be similar to the preceding one. However, given that the beginning of the decline is similar for both categories, around 14/15, one has to take into serious consideration other issues related to puberty changes, as previously explained.

Graph 2.

Changes in Religiosity across Time and Family Typology.

Graph 2.

Changes in Religiosity across Time and Family Typology.

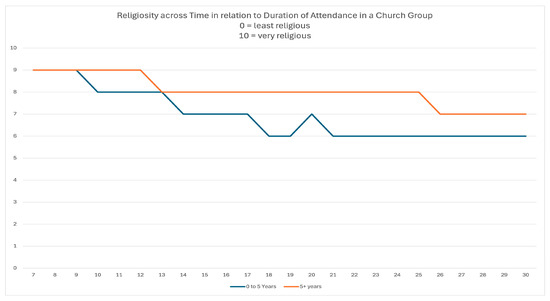

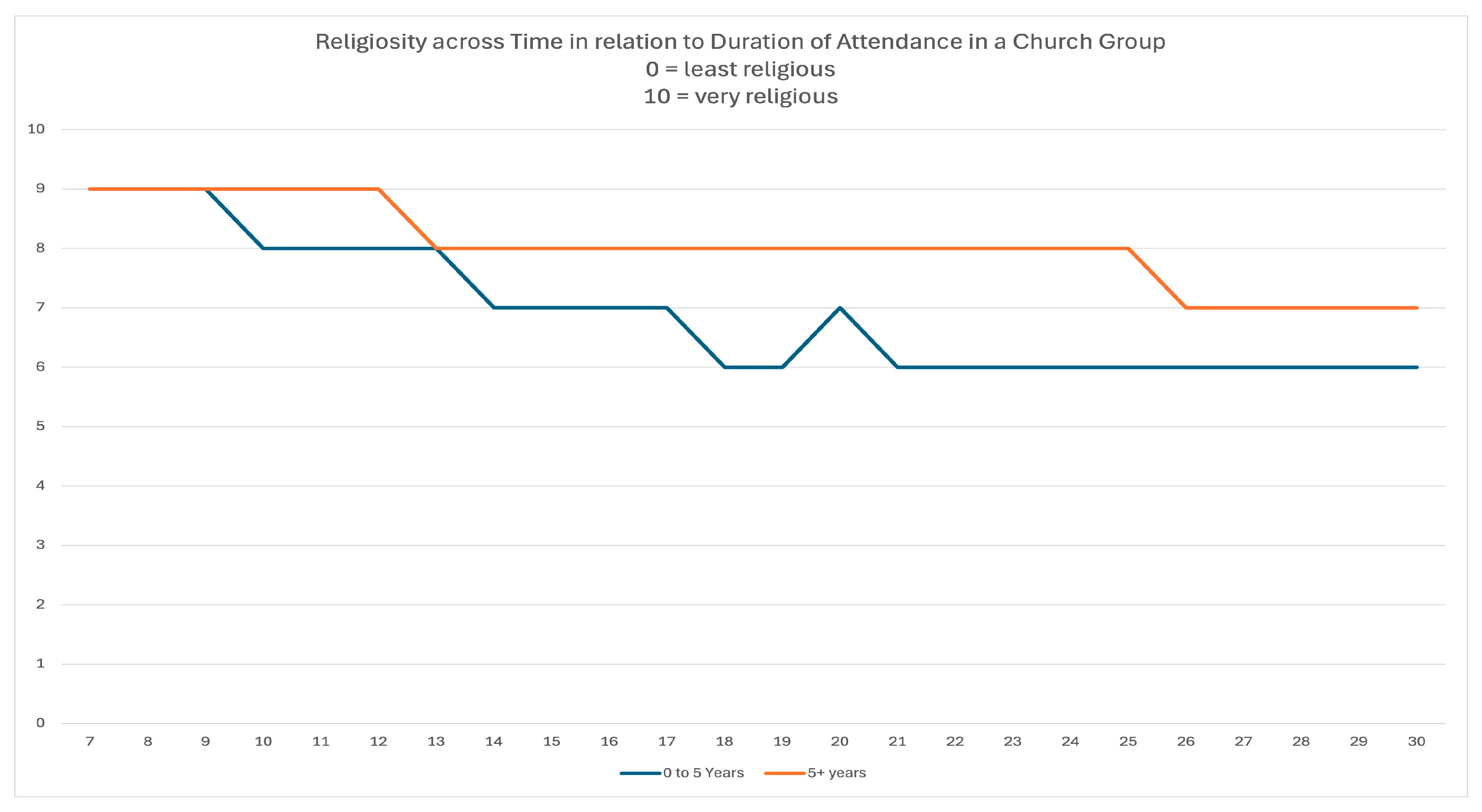

The other contrast (Graph 3) is that between those who had spent 5 years or more in a church group or organization and those who had spent fewer years or none. The decline for the latter starts earlier, around 10/11, dips around 13/14 and further around 17/18, and then stabilizes in later adult years. For the former, the decline starts later, around 13/14, followed by another decline 12 years later, around 25/26. It is probable that the 12-year interval between these two moments corresponds to the period spent in a religious organization, which could have served as a supportive environment for their faith. The second decline coincides with other major issues and decisions typical of that age, such as career and life planning. This resonates with the studies of Silverstein and Bengston (2018), who found that religion seems to vary across the life course, often declining in late adolescence and early adulthood, and then increasing as people age, form new relationships, start their own families, and mature into later adulthood.

Graph 3.

Changes in Religiosity across Time and Duration of Attendance in a Church Group.

Graph 3.

Changes in Religiosity across Time and Duration of Attendance in a Church Group.

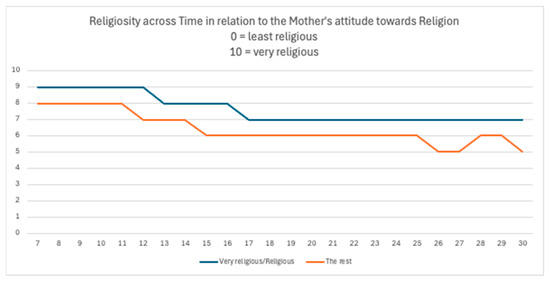

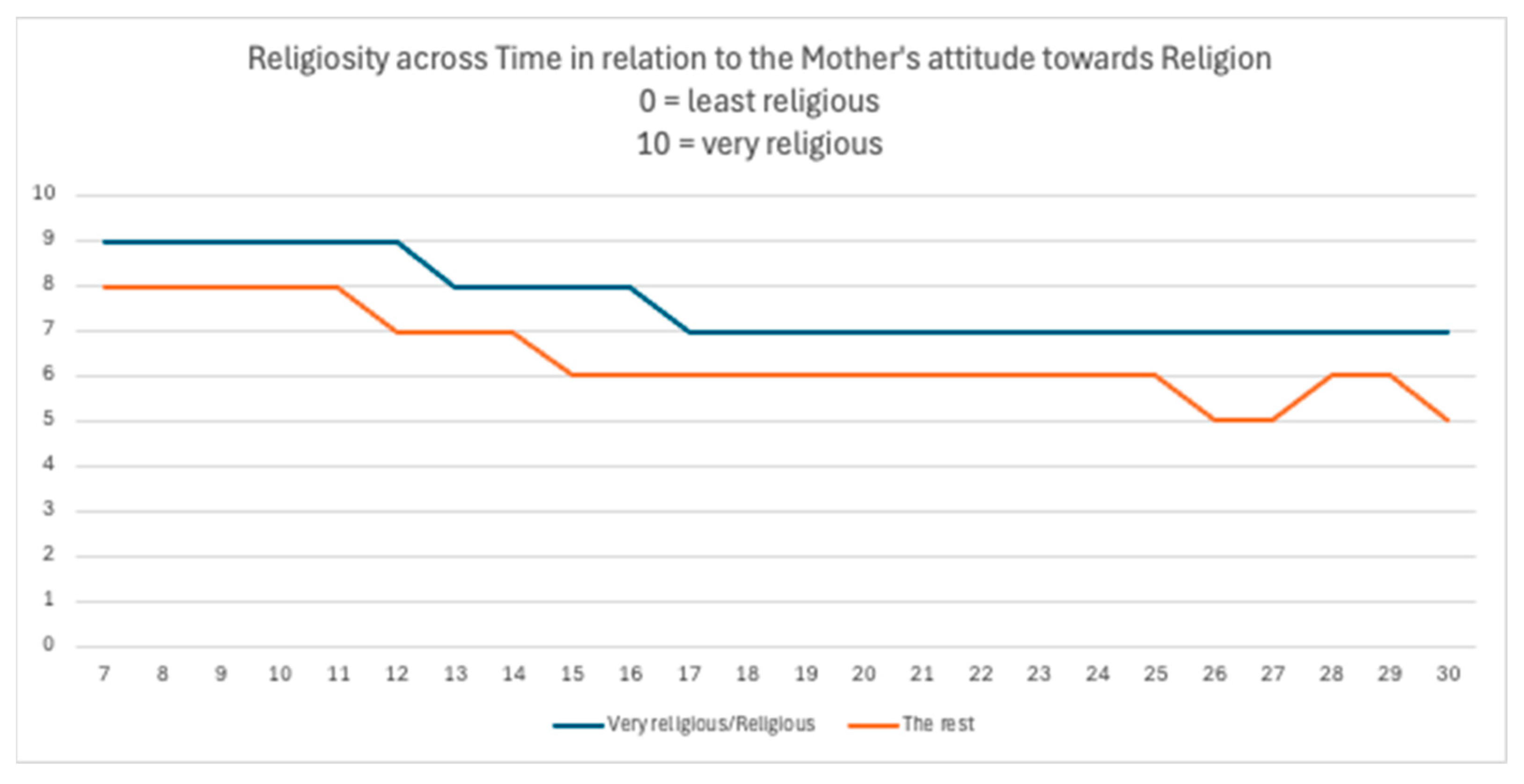

The relevance of mothers in the transmission of faith can be visualized through Graph 4. The pattern resembles that of the previous graphs, with turning points around 12/13, and later during adolescence around 15/17, even though the differences are not that marked. For those whose mothers are more religious, there seems to be a certain stability in their religion line that extends into adult life. For the rest, the trend shows a further decline that continues into adulthood.

Graph 4.

Changes in Religiosity across Time and Mother’s Attitude Towards Religion.

Graph 4.

Changes in Religiosity across Time and Mother’s Attitude Towards Religion.

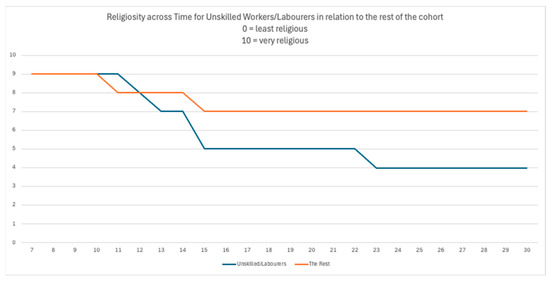

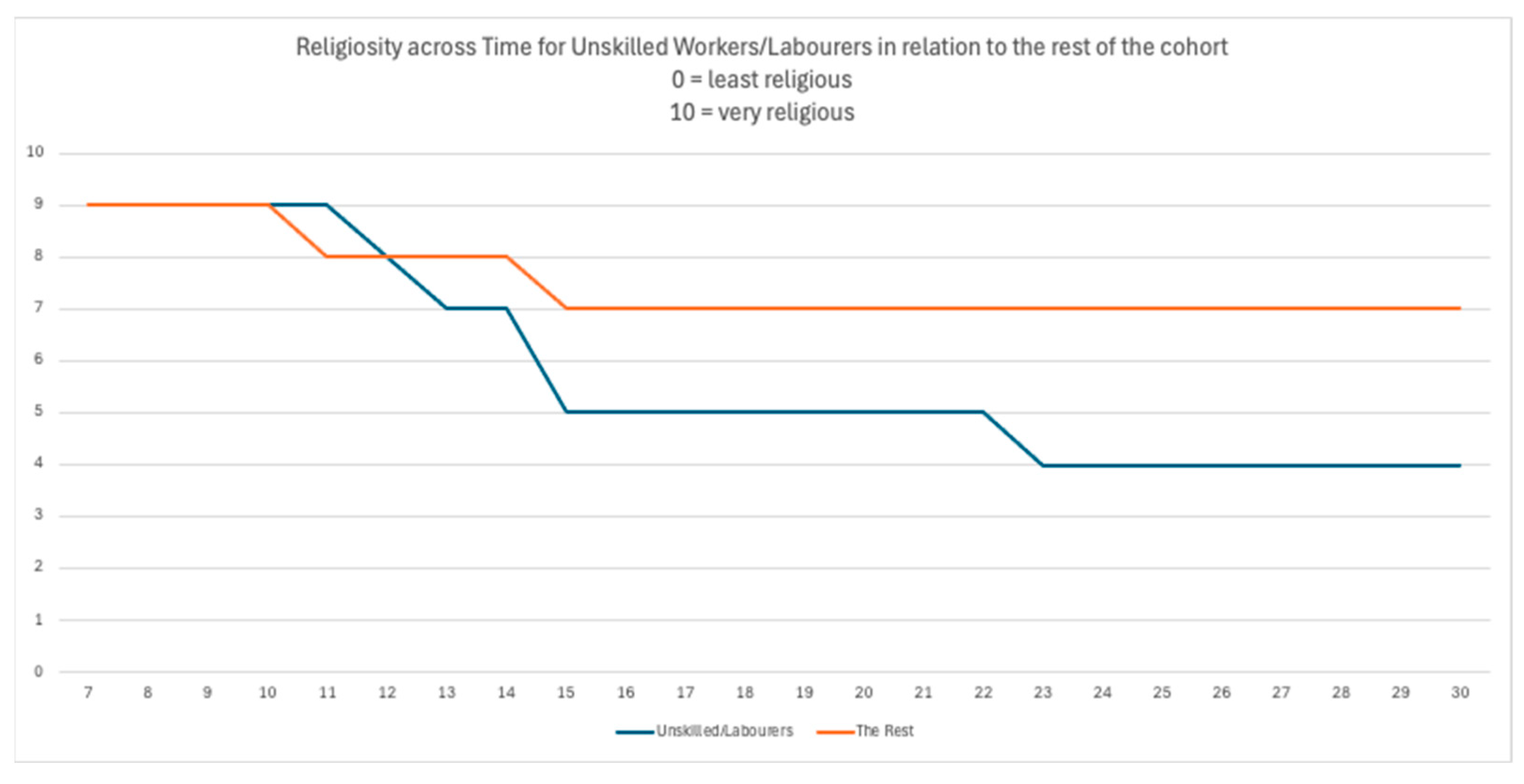

Graph 5 displays the religious journey of the unskilled workers, who emerged as a very distinct category in several contrasts. While they all started on the same level as the others, their religiosity started declining around the time of puberty and continued declining further in adult life. There could be many interpretations besides those already mentioned related to puberty and other external influences, such as that of their peers. One plausible interpretation specific to this category could be their lack of formal education, reflected in their lack of interest in religious education. Incidentally, these were also those who showed the most interest in the socio-cultural expressions of religion.

Graph 5.

Changes in Religiosity across Time for Unskilled Workers/Laborers and the Rest of the Cohort.

Graph 5.

Changes in Religiosity across Time for Unskilled Workers/Laborers and the Rest of the Cohort.

6. Discussion

Following the analysis and interpretation of the results, one could attempt to draw a synthesis of the major findings, taking the research questions into consideration again. Starting from the first question, related to the positioning of this sample on the MAPS, faith and security were originally considered to be two of the five sources of meaningfulness, as these correlated positively with meaningfulness. However, this was not the case in the present study. This contrasts with the hypothesis that religion functions as a meaning-making mode, in that the relationship between the two was very small. Rather, the two constructs seemed to be related more with other factors, mainly the family.

Moreover, in this study, it was the two-parent family that proved to be pivotal. Two-parent families represented 85% of the participants. For these, home was experienced as a secure environment, and parents were perceived as caring. Furthermore, religion and the family were so closely intertwined as to be considered as almost defining features of this society, and as major sources of meaning and security. Mothers, in particular, seemed to have a stronger bearing in the transmission of faith to their children. Some of the studies mentioned have also shown the family to be the most salient and proximal context for religious development, despite the fact that youths do not always follow in the religion of their parents. Inversely, there is plenty of evidence that links lower parent worship service attendance, lower parent religious importance, and fewer religious conversations in adolescence with later religious de-identification (Hardy et al. 2022, p. 5) and religious deconversion (Hardy et al. 2019).

Although religious attendance is not an exhaustive criterion for assessing religiosity, this study has shown this not only to be relevant but also to be a very important discriminating factor. Moreover, this study has shown an increase of 3% in church attendance for this age bracket. This further increases its value. Despite all predictions following the COVID-19 lockdown, religious attendance in Malta remained high, and the expected drastic decline in church attendance did not happen.

Another feature that emerged is the relevance of continuing religious education well into adolescence. Being a member of a church group and attending religious practices on a regular basis seems to make a difference in the religious life of the adolescent. This is especially put to the test around the ages of 12 and 13, when the first major changes take place, such as a waning of interest in religion, and a diminished motivation for deepening their religious education and attending church services. Moreover, other life challenges enter the picture. These findings have consistently shown a strong link between the two. This is perhaps also due to the fact that many youth groups are run by the Church.

A similar conclusion can be reached with regard to the analysis of the ADS results. An interesting feature is the absence of any significant difference between the churchgoers and the non-churchgoers in transcendental emptiness experience. One plausible interpretation is that self-transcendence is not restricted to the practice of religion but can also be experienced outside its confines. This could be another argument in support of the claim that religion and spirituality could be contending for the same territory.

Another significant finding was the relationship between unskilled workers and religiosity. These individuals scored consistently lower than their counterparts not only on faith in the MAPS but also on withdrawal from the community in the ADS. This was the category that differed most from the rest with regards to religiosity. It would be interesting to explore the reasons why, but that goes beyond the purpose of this study. At the same time, their higher interest in the socio-cultural expressions of religion could be indicative of their level of engagement with religion, and possibly a compensation for their lack of involvement in other practices This also seems to be the case with those who are experiencing a dissatisfaction with the religious institution and those who are still grappling with personal existential issues.

With regards to the exiters or deconverts, who amount to about one-third of this sample, it does not appear that these have migrated to another religion or sect. This could perhaps be indicative of a secularization process. However, it could also mark a shift towards a personal or private spirituality. On the other hand, those who left because of a dissatisfaction with the institution seem to continue to grapple with personal existential issues. One significant feature that came from the personal quest construct was that 16% of those who left their religion did so because they found no relief in their suffering. Suffering can be a make-or-break factor when it comes to belief. Another 46% said that they left under the influence of their peers. This corresponds to a very important juncture in the adolescents’ life, where the influence of the family of origin starts to wane and that of their peers increases, alongside an increased sense of autonomy, as explained by various studies (Melissa et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2017; Bengston et al. 2015; Rydz 2014; Arnett Jensen and Arnett Jensen 2002). All of these factors have a strong bearing on faith and religiosity.

Finally, what might appear paradoxical is that one-third of those who left did not exclude the possibility of coming back some day. This suggests that, for these, the religious journey is not over yet.

7. Conclusions

This study was intended to gauge the religiosity of adolescents and young adults with the help of validated questionnaires. While the validity of the instruments was retained, notable differences were evidenced, most probably due to the peculiarities of this population and other cultural differences. Most important among these are the religious traditions, the strength of the two-parent family, and the sense of community fostered by participation in religiously oriented groups, which reinforce and deepen their religious commitment. These factors seem to mitigate that exodus drive, which usually takes place at around puberty and under the influence of biological, cognitive, and social changes. Paradoxically, all of these coincide with Confirmation, which is supposed to be an important step in affirming one’s faith and religion.

At the same time, for a sizeable number who continue with their religious education, their religiosity is kept alive. For these, the religious groups or the faith communities act as intermediaries in the transition process from the family to the other social relationships. The findings suggest that the effects of this intermediary phase continue to be felt well into adult life. For those who stay in religion, and thanks to the faith groups, religion not only serves as a source of meaning but also provides them with an important opportunity to meet their other needs, such as belonging and socialization. This resonates with Saroglou’s (2011) integrating concept of religiousness, which holds that a person who is religious in the complete sense is involved in the processes of believing, bonding, behaving, and belonging. All of these processes come with their own cultural variations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G. and C.-M.S.; Methodology, P.G. and C.-M.S.; Software, P.G.; Validation, P.G.; Formal Analysis, P.G.; Resources, C.-M.S.; Writing—Original Draft, P.G.; Writing—Review and Editing, C.-M.S.; Visualization, C.-M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the University of Malta’s Research Ethics Review Procedures. The Research Ethics and Data Protection form code is THEO-2024-00022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study through the same anonymous online questionnaire that they filled out, and where they were informed of the procedures and that, upon submitting the questionnaire, they were agreeing to take part in the research.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Liberato Camilleri of the Department of Statistics and Operations Research of the University of Malta, who assisted this project in the elaboration of the statistical data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | With acknowledgment to Prof. Liberato Camilleri of the Department of Statistics and Operations Research of the University of Malta, who assisted this project in the elaboration of the statistical data. |

| 2 | Some of the 10 questions in this section were adopted from the studies of Nowosielski and Bartczuk (2023). |

References

- Arnett Jensen, Jeffrey, and Lene Arnett Jensen. 2002. A congregation of one: Individualized religious beliefs among emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research 17: 451–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson, Vern L., Merril Silverstein, Norella M. Putney, and Susan C. Harris. 2015. Does religiousness increase with age? Age changes and generational differences over 35 years. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 363–79. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA). 2024. Nineteen Sixty-Four. World Values Survey Wave 7 (2017–2022). Available online: https://nineteensixty-four.blogspot.com/2024/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Galea, Paul, Pauline Dimech, Adrian-Mario Gellel, Kevin Schembri, and Carl-Mario Sultana. 2023. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic: Religion and spirituality during these challenging times. Melita Theologica 73: 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, Sam A., and Emily M. Taylor. 2014. Religious deconversion in adolescence and young adulthood: A literature review. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 46: 180–203. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, Sam A., and Emily M. Taylor. 2024. The past, present, and future of research on religious and spiritual development in adolescence, young adulthood, and beyond. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 46: 109–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, Sam A., and Gregory S. Longo. 2021. Developmental perspectives on youth religious non-affiliation. In Empty Churches: Non-Affiliation in America. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 135–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, Sam A., Dorian Hatch, Jenae M. Nelson, and Philip Schwadel. 2022. Family religiousness, peer religiousness, and religious community supportiveness as developmental contexts of adolescent and young adult religiousness deidentification. Research in Human Development 19: 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, Sam A., Jenae M. Nelson, Joseph P. Moore, and Pamela Ebstyne King. 2019. Processes of religious and spiritual influence in adolescence: A systematic review of 30 years of research. Journal of Research on Adolescence 29: 254–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapsley, Daniel K, and Darcia Narvez. 2013. Moral Development, Self, and Identity. Mahwah: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Bo Hyeong Jane, Lisa D. Pearce, and Kristen M. Schorpp. 2017. Religious pathways from adolescence to adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 678–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luckmann, Thomas. 2022. The Invisible Religion: The Problem of Religion in Modern Society. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Łysiak, Małgorzata, Beata Zarzycka, and Małgorzata Puchalska-Wasyl. 2020. Deconversion processes in adolescence—The role of parental and peer factors. Religions 11: 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisner Hertz, Joachin. 2024. Germany: Study Shows That Young Muslims Believe More in God Than Catholics. October 18. Available online: https://zenit.org/2024/10/18/germany-study-shows-that-young-muslims-believe-more-in-god-than-catholics/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Melissa, Chan, Kim M. Tsai, and Andrew J. Fuligni. 2015. Changes in religiosity across the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 44: 1555–66. [Google Scholar]

- Nowosielski, Mirosław, and Rafał P. Bartczuk. 2019. Psychometric validation of the adolescent deconversion scale. Przegląd Psychologiczny 62: 355–99. [Google Scholar]

- Nowosielski, Mirosław, and Rafał P. Bartczuk. 2023. ADS v. 20230310, Unpublished manuscript.

- Paloutzian, Raymond F. 2017. Invitation to the Psychology of Religion. New York and London: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Paloutzian, Raymond F., and Crystal L. Park. 2013. Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. New York and London: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Centre. 2020. Pew Research Centre. September 10. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2020/09/10/u-s-teens-take-after-their-parents-religiously-attend-services-together-and-enjoy-family-rituals/ (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Płużek, Zenomena. 2002. Psychologia Pastoralna [Pastoral Psychology]. Cracow: Instytut Teologiczny Księży Misjonarzy. [Google Scholar]

- Rydz, Elżbieta. 2014. Development of religiousness in young adults. In Functioning of Young Adults in a Changing World. Edited by Katarzyna Adamczyk and Monika Wysota. Krakow: Wydawnictwo LIBRON—Filip Lohner, pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Saroglou, Vassilis. 2011. Believing, bonding, behaving, and belonging: The big four religious dimensions and cultural variation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42: 1329–40. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, Tatjana. 2009. The sources of meaning and meaning in life questionnaire (SoMe): Relations to demographics and well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology 4: 483–99. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, Tatjana, and Lars Johan Danbolt. 2023. The meaning and purpose scales (MAPS): Development and multi-study validation of short measures of meaningfulness, crisis of meaning, and sources of purpose. BMC Psychology 11: 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, Rüdiger J., and Hans-Ferdinand Angel. 2015. Psychology of religion and spirituality: Meaning-making and processes of believing. Religion, Brain and Behavior 5: 139–47. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, Merril, and Vern L. Bengston. 2018. Return to religion? Predictors of religious change among babyboomers in their transition to later life. Journal of Population Ageing 11: 7–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Streib, Heinz, Christopher F. Silver, Rosina-Martha Csöff, Barbara Keller, and Ralph W. Hood. 2009. Deconversion: Qualitative and Quantitative Results from Cross-Cultural Research in Germany and the United States of America. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Uecker, Jeremy, Mark D. Regnerus, and Margaret L. Vaaler. 2007. Losing my religion: The social sources of religious decline in early adulthood. Social Forces 85: 1667–92. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tongeren, Daryl R. 2024. Done: How Much to Flourish After Leaving Religion. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).