Abstract

Between the eighth and ninth centuries, the world entered a second period of strong winter monsoons, which precipitated a series of recurrent natural disasters, including reduced summer rainfall and prolonged droughts. The various types of droughts that occurred in southeastern China are documented in historical records, which also include the official-led ritual prayers to the local deities that were conducted during these challenging periods. As evidenced in these historical records, officials implemented a series of measures to provide solace to the populace, including the restoration of shrines and temples and the offering of sacrifices and prayers to the local deities, such as the Wutang God 吳塘神 and the Chutan God 儲潭神. These actions were intended to leverage the influence of the local deities to mobilise labour and financial resources for the implementation of public works, including the reclamation of barren land and the construction of dikes and ponds. These initiatives ultimately proved instrumental in enabling the populace to withstand the adverse effects of disasters. This approach represents a distinctive strategy for coping with drought in ancient China. It may provide insights into how governments and non-governmental organisations can utilise the influence of religious beliefs to unite people in addressing the climate crisis in the present era.

1. Introduction

China is an ancient country with a long history and civilisation. Its formation and subsequent development occurred within a particular natural environment. Toynbee (1987) observed that China’s territory is exceptionally expansive, and its environmental diversity is considerable; therefore, the natural challenges that humanity must confront in this region are more significant than those in the Two River Basin and the Nile. The natural disasters faced in ancient China can be classified into two principal categories: sudden-onset disasters, including floods, droughts, and earthquakes, and gradual-onset disasters, such as environmental pollution and soil erosion (Yan 2008, p. 19). In ancient Chinese society, which was agrarian in nature, the occurrence of disasters had a significant impact on the entire social structure in all directions. Among natural disasters, drought was particularly destructive, not only causing damage to agricultural production but also leading to famines and epidemics, which in turn resulted in widespread fear and social unrest (M. Zhang 2019, pp. 64–68). Scholars have proposed a correlation between the decline in the power of the Chinese dynasties and the reduction in precipitation, which resulted in significant challenges to the livelihoods of the peasantry and led to social unrest (Zhang et al. 2008, p. 942).

The mid-to-late Tang Dynasty (700–907) coincided with a period of strong winter monsoons in East Asia, which resulted in erratic climatic changes during this period (Yancheva et al. 2004, pp. 74–77).1 As a result, the southeastern region of China was subjected to a series of droughts, which not only disrupted normal agricultural practices but also had a significant impact on the lives of the general population. In order to alleviate the suffering of the populace, local officials not only provided material assistance but also employed the local religious belief system, conducting ritual prayers to seek divine “intervention” to help the people overcome the crisis.2

The historical materials pertaining to droughts and the religious ritual prayers are particularly rich and comprehensive, offering valuable insights into the connections between local religious beliefs and drought relief. For instance, the Datang Kaiyuan Li 大唐开元礼 (The rites of the Kaiyuan reign of the Tang Dynasty), a ritual code compiled during the Tang Dynasty in China, provides a comprehensive description of ritual prayers.3 It states that in the event of a drought, the central government and local officials frequently engaged in ritualised practices, including prayers and offerings to the deities such as beef and mutton. These rituals were conducted with the objective of persuading the gods to send rain, thereby alleviating the suffering of the populace. The majority of historical records regarding official and local responses to droughts can also be found in official historical texts, such as the Jiu tang shu 舊唐書 (The old book of the Tang Dynasty), the Xin tang shu 新唐書 (The new book of the Tang Dynasty), and the Zizhi tongjian 資治通鑑 (Comprehensive mirror to aid in government). In order to facilitate a more comprehensive discussion of the ritual prayers provided to the local gods by the local officials during the Tang period, this paper also makes reference to local annals and collections of literature by renowned writers from the same period. For instance, the Bai Juyi ji 白居易集 (The essay collection of Bai Juyi) is a significant historical repository, comprising poems and writings on the ritual prayers that he composed during his tenure as a local official and were directed towards the local deities.

The aim of this paper is to elucidate the nature of the religious ritual prayers held by officials in southeastern China during this period in honour of the local deities. While Confucianism established a system of official deities to be worshipped, the local officials demonstrated a tendency to employ the local beliefs and customs, and to engage in the practice of praying to the local deities. Occasionally, itinerant “rain-makers”, such as monks and sorcerers, were employed in an effort to cope with droughts. The interactions between the state agents and the general public are explored in the context of the ritual prayers employed in response to the disaster crises. Furthermore, an investigation into the historical function of religious activities in addressing drought conditions in China may also facilitate an understanding of the potential to apply local beliefs to address contemporary environmental crises.

2. Official and Local Gods of the Tang Dynasty

In order to discuss the practices of worshipping local deities in southeastern China during the eighth and ninth centuries for purposes of drought relief, it is essential to first gain an understanding of the distinction between official and local deities of the Tang Dynasty, as well as the cultural characteristics associated with the shrines and temples.

2.1. Official Gods

Following the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE), the Chinese people generally believed in a plurality of deities, including those of heaven, mountains and rivers. Offerings and sacrifices were made to these deities, with prayers directed towards securing their favour. Evidence derived from oracle bone inscriptions suggests that during this period, the deities held in veneration were numerous and diverse, and that there was an absence of a unified sacrificial system; this has led modern scholars to term this era the “pantheon” (Eno 1990, pp. 41–45).

In the period preceding the Qin dynasty, rulers sought to both perpetuate and adapt the loose sacrificial system in an attempt to render it more systematic. Li ji禮記 (Book of Rites) provides a detailed account of the roles of the Son of Heaven, the vassals, the officials, and the scholars in sacrificial ritual prayers, as well as the objects to be sacrificed and the number of times they should be offered:

The Son of Heaven offers sacrifices to those of the heavens and earth, those situated in the four cardinal directions of his kingdom, those of the mountains and rivers, and those associated with domestic spaces such as houses, hearths, lands, gates, and paths. These sacrifices are conducted on an annual basis. The vassals offer sacrifices to the deities associated with their fiefdoms, as well as to the gods of mountains and rivers, the gods of houses, hearths, lands, gates, and paths, on an annual basis. The officials offer sacrifices to the gods of houses, hearths, lands, gates, and paths on an annual basis. The scholars offer sacrifices exclusively to their ancestors. The practice of worshiping deities is not to be undertaken at one’s discretion if the deities in question have been abolished; similarly, the abolition of certain deities is not to be enacted at one’s discretion(Liu 2016, p. 37).4

These ritual prayers were held at four specific times of the year: the spring equinox, summer solstice, autumn equinox, and winter solstice. Each of these ritual prayers was dedicated to a specific deity, thereby reflecting the hierarchical differences between these deities. The standardisation of the ritual prayer procedure indicates that these deities were considered to be officially certified gods with government-conferred legitimacy.

By the time of the Qin Dynasty (221–207 BCE), the rulers had continued to refine the sacrificial system and established a more systematic national sacrificial system.5 This assertion is supported by the Shi ji 史記 (The records of the grand historian):

Following the unification of the six kingdoms under the Qin Dynasty, specific officials were appointed to conduct sacrificial rituals to the deities such as heaven and earth, mountains and rivers, as well as ghosts and gods. This practice ultimately led to the codification of a comprehensive set of regulations… The major sacrifices to heaven and earth, major mountains and rivers, as well as ghosts and gods were performed by “Taizhu 太祝”, the officials entrusted with the responsibility of conducting sacrifices. These officials made regular offerings and sacrifices to the gods according to the time of the year representing the emperor.6 The practice of offering sacrifices to other mountains, rivers, and ghosts and gods was conducted on occasions when the emperor passed by these locations(Sima 1959, pp. 1371–77).7

The Qin Dynasty established specific guidelines for the worship of deities, encompassing both those that were honoured on a state level and those that were venerated by the local populace. As the Shi ji states, “the temples dedicated to the gods in various counties and distant locations were not administered by sacrificial officials. Rather, these temples were offered and sacrificed by the local populace on an individual basis” (Sima 1959, p. 1377).8 It was not until the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 AD) that rulers began to differentiate more clearly between official and local gods, thereby establishing the template for the sacrificial system of deities that would come to be implemented throughout China (Bujard 2011, p. 773).

By the time of the Tang Dynasty, the types and number of official deities had become more clearly defined. In addition to deities associated with the heavens, such as the God of Heaven and the gods of the sun, moon, and stars, notable historical figures were also enshrined as deities, such as Confucius (551–479 BCE) and Jiang Ziya 姜子牙 (?–1015/1036 BCE). Concurrently, Buddhism and Taoism were integrated into state ritual prayers, thereby establishing a more comprehensive and elaborate official system of sacrifices. More importantly, the government not only built shrines and temples for these official deities in the capital city but also allowed local officials to build shrines and temples to support the deities and conduct regular ritual prayers, thus supplementing the national sacrificial system.

2.2. Local Deities

In addition to the official deities, a variety of local deities were present in the religious map of the Tang Dynasty (Valerie Hansen 2014, p. 3), such as the city gods, the Bailuquan God 白鹿泉神 (the god of White Deer Spring), and Chen Guoren 陳杲仁 (?–620), who is a deified legendary figure from Chinese history. Chen was a renowned military leader during the Sui Dynasty who is reputed to have exhibited remarkable courage in his endeavours to safeguard the southern expanse of the Yangtze River from the ravages of warfare. In subsequent years, the populace residing within the southern reaches of the Yangtze River in China held him in high esteem, venerating him as a local deity (Mao 2013, p. 44). In the event of adversity, the populace would petition these deities for a change in weather, the alleviation of illness, and protection from criminal activity. This form of local deity veneration was most prevalent in the southeastern region during the Tang Dynasty. Cai (2007, pp. 203–32) observed that there were hundreds of shrines and temples dedicated to these deities in major cities in the southeastern region, as well as in remote rural areas.

Local deities can be classified into two distinct categories. The initial category comprises those deities that had been endorsed by the local government. Such deities were also referred to as “semi-official” (Romen 1997, pp. 93–125). The enshrining of Magu 麻姑 (Sister Ma) is an example of establishing a semi-official deity. During the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317–420 AD), in the Fuzhou region of Jiangxi Province, an individual named Magu, distinguished by the slenderness of her hands, was said to have lived long enough to see the transformation of seawater into farmland (H. Ge 2010, p. 95).9 From then on, the local population established Magu as a deity and offered prayers seeking her blessing. During the reign of Emperor Xuanzong 唐玄宗 (r. 712–756) of the Tang Dynasty, a drought occurred in the Fuzhou region. In response, the populace went to Magu Mountain to pray for rain, and their prayers were documented to have been answered immediately. In addition, a vision of a yellow dragon manifested itself on Mount Magu. Consequently, the emperor attributed this to a manifestation of Magu’s spirit and ordered the restoration of the altar on Mount Magu (Dong 1983b, pp. 3423–24).10 This act of veneration can be interpreted as a state acknowledgement of Magu’s status.

The second category of deities comprised those that were exclusively venerated by the populace of their own volition, in the absence of any official endorsement. This category of deities included plants and animals that had cultivated themselves and become capable of transforming into fairies and spirits. As documented in the Taiping guangji 太平廣記 (Extensive records of the Taiping [Xingguo] reign period, 976–983), following the establishment of the Tang Dynasty, a considerable number of individuals in the southern regions of the country began to venerate foxes as deities (F. Li 1961, p. 3658). This was demonstrated by the erection of a multitude of shrines and temples in their honour, as well as the regular presentation of sacrifices within private residences.

The predominant belief system during this historical era was characterised by the notion that divine entities, encompassing the gods of the earth, landscape, animals and plants, along with spirits and ghosts, wielded immense power over various facets of human existence, including merits, fame, fortune, wealth, and the blessings or misfortunes a person might encounter. This profound belief was reflected in the establishment of temples and shrines by the local populace, which served as physical manifestations of their reverence for the local deities. When the government recognised the value of these local shrines and deities in defending the interests of the court, they were incorporated into their official affirmations. Conversely, when these entities were deemed superfluous to the state, they were frequently prohibited from existence. The Jiu tang shu chronicles the repeated issuance of orders by the Tang rulers, mandating the prohibition of the veneration of local deities (Z. Zhang 1975b, p. 31).11 The State regarded these local deities, which did not conform to the state ritual, as “Yaoshen 妖神 (demonic deities)”. The temples and shrines dedicated to them were called “Yinsi 淫祀 (unauthorised cults)” (Valeria Hansen 1993, p. 374). In alignment with the national sacrificial system, local officials proceeded to destroy unauthorised cults and prohibit the worship of local deities. For example, during his tour of the Jiangnan region in the Tang Dynasty, Di Renjie 狄仁傑 (630–700), a prominent official of the Tang Dynasty, observed that the ritual prayers of the Wu-Chu 吴楚 regions (part of the southeastern area of China) contravened the established rites and laws (Z. Zhang 1975a, p. 2887). Subsequently, he proceeded to demolish more than 1700 shrines and temples dedicated to local deities.

Although some local deities had been officially acknowledged, the majority of local deities were denied recognition by the government (Lei 2009, pp. 222–26) and had been marginalised by the official sacrificial system at best or were subjected to strict official control and suppression at worst (Kim 2006, pp. 1–2). Nevertheless, due to the high level of respect accorded to these local deities by the local populace, it was customary for local officials to conduct sacrificial ceremonies in their honour when natural disasters such as droughts occurred in the hope of securing the deities’ blessings and thereby appeasing the people. Consequently, during the Tang Dynasty, the unrecognised local gods also occupied a significant position in the ritual prayers of local governments. Some of these deities even exerted influence beyond the regions where they were traditionally worshipped, becoming the object of veneration among people in the entire southeastern region of China (J. Yang 2019, pp. 49–66).

2.3. The Deities and the Shrines and Temples

During the Tang Dynasty, both official and local deities were usually worshipped through the erection of shrines and temples in their honour. Shrines and temples served a similar function for gods as houses do for humans. Indeed, it was even believed that opulent shrines and temples would have a significant impact on the majesty of the gods (Hansen 2014, p. 57). When the government resolved to construct shrines and temples for official deities, considerable human and material resources were deployed to create an exterior of exceptional splendour, to cast statues, and to paint frescoes for the deities. This not only served to enhance the prestige of the deities in question but also facilitated the identification of said deities by their worshipers. Once completed, shrines and temples were sites of regular ritual prayers conducted by officials offering a variety of items, including meats and alcohol (L. Li 1992, p. 128). The populace would frequently visit the shrines and temples to pay their respects and pray to the gods for blessings of health and protection from adversity. Therefore, the shrines and temples served as crucial conduits for communication between officials, the populace, and deities.

While local deities might also be venerated through the erection of shrines and temples, their authority was contingent upon whether they could effectively answer prayers (Feuchtwang 1977, pp. 583–84). In the absence of a divine response, the practice of worship might cease, which could result in the deterioration of the shrines and temples. This scenario was quite common in Chinese historical records. On some occasions, during ritual prayers, officials would even explicitly express their expectation that the deities would reveal their spiritual power in a timely manner. If the deities failed to meet such expectations, there was a risk that the officials might take actions that could lead to temples dedicated to these deities being damaged. As scholars have pointed out, this type of ritual, in essence, constitutes an instrumental activity. It serves as a manifestation of the evolution of the cognitive perceptions and psychological attitudes of the ancient Chinese populace regarding deities (Hong et al. 2024, p. 345). Once the gods had responded to these requests, the people would duly record them and proceed to repair their shrines and temples for worship, thereby reflecting the principle of “reciprocity between humans and gods”, which was a fundamental tenet of traditional Chinese culture (L. Yang 1957, pp. 291–309). During periods of drought, government officials and the general public employed a variety of methods to request precipitation, regardless of whether they were officially recognised. If precipitation did not follow the invocation of a deity, there was frequently a readiness to seek the assistance of other deities (Hansen 2014, pp. 75–78). Shrines and temples dedicated to local deities were usually less well preserved than those dedicated to official gods. Nonetheless, they occupied a pivotal role in the social fabric of local communities.

3. Drought in Southeastern China During the Eighth and Ninth Centuries

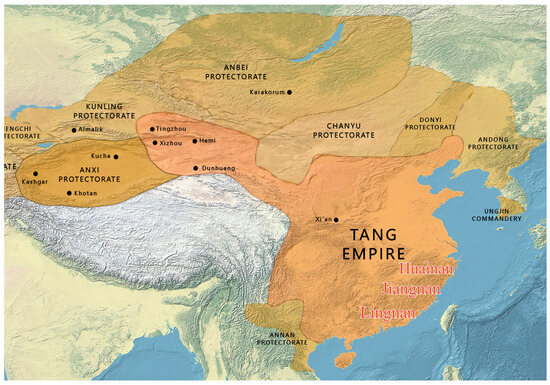

The Tang Dynasty (618–907) was the ruling dynasty of China during the eighth and ninth centuries. It was the most prosperous and open dynasty in Chinese history, with an unusually expansive territory, encompassing the Korean Peninsula in the east, the Aral Sea in Central Asia in the west, Lake Baikal in the north, and the region around Hue in Vietnam in the south. The Tang Dynasty established the line from the Qin Mountain to Huai River as the boundary between the northern and southern regions and delineated ten administrative districts. The southeastern region encompassed the Jiangnan Circuit 江南道, Lingnan Circuit 岭南道, and Huainan Circuit 淮南道, which were analogous to the modern-day provinces of Guangdong, Zhejiang, Fujian, Jiangxi, and Anhui, as well as portions of other provinces (see Figure 1).12

Figure 1.

A map of China during the Tang Dynasty.

The topography of southeastern China is characterised by elevated terrain in the west and low-lying areas in the east, predominantly comprising hills and plains. The region’s plains are traversed by a network of rivers and lakes, bisected by a complex system of waterways, and bordered by the vast expanse of the East China Sea to the east. The majority of urban settlements in the region were constructed in close proximity to waterways, including rivers, canals, and lakes. In terms of climatic characteristics, the southeastern region has a typical tropical and subtropical monsoon climate, characterised by high temperatures and precipitation during the summer monsoon season and relatively mild winters with minimal precipitation.

In the seventh century, the climate in southern China was characterised by warmer conditions, which created favourable circumstances for the advancement of the agricultural economy and the growth of the population. However, from the mid-eighth century onward, the climate in the southeast was subject to erratic changes due to the influence of the strong winter monsoon, resulting in frequent large-scale drought disasters (Lan 2001, pp. 4–15). In comparison to other natural disasters, the impact of drought disasters on agricultural societies was particularly severe. For every 100 mm decrease in precipitation, there was a 10 per cent reduction in food production across the entire region (J. Zhang 1982, pp. 9–10). The impact on food production resulted in a decline in food availability, which in turn gave rise to the emergence of secondary disasters, including famines and epidemics.

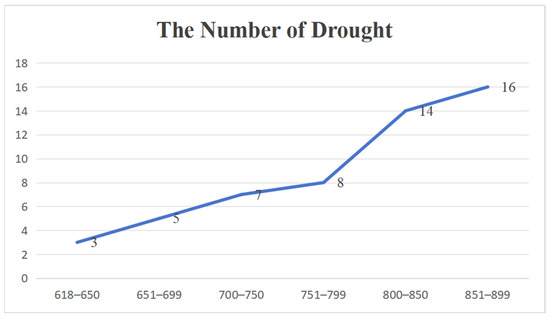

As illustrated in Figure 2, the droughts that occurred in southeastern China during the eighth and ninth centuries exhibited two notable distinctions when compared to those that took place during the seventh century. The first notable difference is that the number of droughts increased, their duration was longer, and their scope was wider. In the first year of Yongzhen 永貞 (805), a sudden drought swept through 26 Zhou 州 (prefectures), including Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Huainan, encompassing almost the entire southeastern region and causing significant losses (Ouyang 1975, p. 917). From 805 to 812, the southeastern region experienced droughts on an almost annual basis, with each episode lasting several months. This demonstrates the significant impact of monsoon climatic variations on this region.

Figure 2.

Drought outbreaks in the southeastern part of the Tang Dynasty, 7th–9th centuries.13

Secondly, the droughts that occurred during this period had a more detrimental impact on society. For example, “Dugu gong xingzhuang 獨孤公行状 (The brief biographical sketch of Dugu Ji)” records that during the sixth year of Dali 大歷 (771), a major part of southeastern China was afflicted by a severe drought, resulting in an unusually high level of crop failure on agricultural land (F. Li 1956, p. 5116). Consequently, upwards of 70 to 80 per cent of the population was compelled to flee or resorted to banditry, precipitating social unrest throughout the region. Another record states that, in the summer of the sixth year of Zhengyuan 貞元 (790), a severe drought afflicted the provinces of Huainan, Zhejiang, and Fujian (Ouyang 1975, p. 917). The severe drought not only resulted in the depletion of wells and the loss of crops, but also led to the emergence and spread of a plague that lasted for several months, causing a considerable number of deaths and extensive economic losses. These circumstances demonstrate that the destructive power of drought in the eighth and ninth centuries resulted in immense hardship for many people in southeastern China, necessitating urgent assistance from the government.

4. Ritual Prayers to the Local Deities and Drought Relief

The abnormal monsoon climate during the eighth and ninth centuries resulted in frequent droughts in the southern region and triggered various secondary disasters, including famine and large-scale plague. These events posed a significant threat to the lives of the populace and to society as a whole. Although the central government took timely measures, such as allocating funds and establishing grain reserve warehouses (Y. Li 2018, pp. 1–9), because of the distance between the southeastern region and the central government, it was difficult to mitigate severe impacts on the population and society. As a result, local officials had to devise other effective ways to provide relief to the population, both spiritually and materially.

It is important to note that in 755, a significant rebellion against the Tang Dynasty took place, which was known as the An-Shi Rebellion. This rebellion resulted in the deaths of millions of people and significantly weakened the authority of the Tang Dynasty. The aftermath of the An-Shi Rebellion was characterised by a protracted period during which the government encountered difficulties in re-establishing its authority over the entire nation (Graff 2002, p. 227). Concurrently, the Rebellion and the subsequent wars also resulted in the deterioration of the authority of traditional knowledge and ethics. This led to a breakdown in trust between officials and the public and brought the mainstream ideological order to the brink of collapse (Z. Ge 2000, p. 199). In order to restore social order during this period, the Tang Dynasty encouraged local officials to adopt flexible measures to actively respond to various types of disasters, such as wars and droughts, so as to pacify the people. One such measure was the encouragement of officials to utilise local deities in the execution of relief operations. For instance, in the “Ming zhangli qiyu zhao 命長吏祈雨詔” (An edict of ordering officials to pray for rain), the emperor commanded local officials to petition the local deities for rainfall to ameliorate the prevailing drought (Dong 1983d, p. 765).

Consequently, in order to effectively address the social crises caused by natural disasters during this period, local officials directed greater attention towards the people’s worship of local deities. They were actively engaged in conducting ritual prayers with the local populace at local shrines and temples, with the intention of securing the blessings of the local deities. Furthermore, given the significance attributed to the “sincerity” in rain prayers (Snyder-Reinke 2009, p. 5), officials were expected to demonstrate a high degree of sincerity when performing these rituals, with the aim of eliciting the gods’ intervention in bringing about rainfall. On the other hand, the Tongdian 通典 (Encyclopaedia of institutional texts), an encyclopaedia of institutional texts compiled in the Tang Dynasty, stipulates that upon the fulfilment of their prayers for rainfall, local officials were also obliged to offer sacrifices to express their gratitude to the deities (Du 1988, p. 2808). This section will examine two exemplary cases: ritual prayers led by Dugu Ji 獨孤及 (725–777) to the Wutang God 吳塘神 and ritual prayers led by Pei Xu 裴谞 (719–793) to the Chutan God 儲潭神. These cases illustrate the underlying motives behind local officials’ proactive engagement in activities related to the worship of local deities.

4.1. Dugu Ji’s Ritual Prayer to the Wutang God

In 772, the region located to the south of the Huai River in China experienced a once-in-a-century drought. This resulted in the absence of precipitation for several months, leading to an inadequate harvest and an elevated mortality rate among the population. Some of the population fled their homes in search of food, while others resorted to banditry (Dong 1983a, pp. 4195–97). At that time, an official named Dugu Ji was responsible for administering Hezhou 和州, a region that was also significantly impacted by the drought. A significant proportion of the population was forced to seek refuge in neighbouring regions, with a considerable number perishing en route. This led to a distressing situation where skeletal remains were visible throughout the landscape. In response to this calamitous event, Dugu Ji not only complied with the central government’s directive to suspend or reduce taxes but also spearheaded a collective act of devotion to the deities (Dong 1983c, p. 4245).

The three surviving sacrificial texts, namely, “Ying tulong wen 塋土龍文 (Sacrificial text of the Tulong God)”, “Ji wanshan wen 祭岏山文 (Sacrificial text of the Wanshan God)”, and “Ji wutang shen wen 祭吳塘神文 (Sacrificial text of the Wutang God)”, reveal that Dugu Ji conducted a series of ritual prayers to the Tulong God, the Wanshan God, and the Wutang God. The sacrificial rites observed in the worship of the Tulong God and the Wanshan God were in accordance with those prescribed by the state, and their veneration was endorsed by the Confucian Classics. They are regarded as official deities.

However, the Wutang God was a local deity worshipped by the people of Shuzhou 舒州, whose abilities were associated with water irrigation and agricultural cultivation in this region. Therefore, Dugu Ji’s ritual prayer to the Wutang God was supposedly not in accordance with the state sacrificial rites that were in practice at the time. The reason for this was that the offerings made by Dugu Ji to the Tulong God and the Wanshan God failed to elicit the desired rainfall. He thus resolved to conduct a prayer ceremony to the Wutang God in conjunction with the local populace at the shrine of the Wanshan God. The litany was recorded in the following manner:

I, Dugu Ji, have the honour to offer wine as a sacrifice to the Wutang God…This summer has been scorching and parched, and the grains and crops are on the brink of withering. The farmers have cried: who can know their plight! Oh, wouldn’t it be wonderful if the god looked down on us and filled the sky with clouds and rain! So that we can all live in happiness and health, and our crops will flourish and thrive! Let our fields be irrigated and our granaries filled to the brim with grain! The god needs our offerings to sustain its power, and we need its power to bless us with rain and bountiful harvests. We offer our sacrifices to ensure a bountiful future for us all(Dugu 2007, p. 409)!14

The worship aimed to petition the Wutang God to send rain, thereby alleviating the suffering of the people in the drought-stricken region. Subsequent historical records indicate that Dugu Ji employed a series of ritual prayers utilising the prestige of the Wutang God to pacify the people, who were in a desperate situation. The Wutang God responded to the petition and sent rain, which led to an increase in the veneration of the Wutang God by the people of Shuzhou as the deity responsible for protecting the region. In 840 A.D., Dugu Ji took the initiative to ascertain the significance of the people’s admiration for the Wutang God by arranging the construction of a new shrine for the Wutang God, which was called the Wubei Shrine 吳陂祠 (Yue 2007, pp. 2476–77).

4.2. Pei Xu’s Ritual Prayer to the Chutan God

In the third year of Dali (768), the Qianyang 愆陽 region of the Qianzhou 虔州 suburb experienced a drought of exceptional severity, resulting in crop failure and a significant deterioration of the local population’s living conditions (Dong 1983e, p. 4674). Pei Xu, the recently appointed governor of Qianzhou, was confronted with a challenging situation and sought divine assistance. However, lacking familiarity with the local religious practices, he consulted with the community and decided to conduct a prayer ceremony at the shrine of the Chutan God.

The worship of the Chutan God dates back to the Jin Dynasty (266–420). The “Chongxiu guangji miao ji 重修廣濟廟記 (Record of rebuilding the Guangji temple)” states that during the period of Xianhe 咸和 (326–334) of the Jin Dynasty, Zhu Wei, an official of Qianzhou, erected the Guangji Temple. When a drought occurred, he summoned the township to offer sacrifices, and heavy rain fell before the ceremony was concluded (Wei and Zhong 1970, p. 468). The deity worshipped by Zhu Wei and the local populace was the Chutan God, renowned for his capacity to summon clouds and precipitation. Given the numerous instances of the Chutan God’s manifestation before the people of Qianzhou, the latter came to regard him as a local deity, worthy of veneration through the building of a shrine for him.

The location of the shrine was selected with great consideration, being situated on the eastern bank of the Gan River and at the western side of Chutan Mountain, approximately twenty miles north of the city of Qianzhou (where the Zhang River and the Gong River converge in the Zhanggong District of Ganzhou City, Jiangxi Province, China) (Wei 1973, p. 880). This particular stretch of waterway is hazardous, posing a significant risk to navigation. Hence, the erection of the Chutan Shrine at this location was intended to harness the protective power of the god for the benefit of both river traffic and the local population.

The ritual prayer conducted by Pei Xu in honour of the Chutan God was observed to have an unusually high number of attendees (Peng 1960, p. 10022). Furthermore, the ritual prayer included a considerable number of offerings and a noteworthy group of female ritual dancers.15 The surviving ritual texts document the outcome of the prayer ritual.

When Pei led the populace into the shrine to engage in prayer, the weather was still bright and sunny. As the sacrificial ceremony commenced, the atmosphere suddenly became overcast, accompanied by thunder and lightning, and was followed by a downpour of rain. The precipitation resulted in the growth of crops on the previously arid farmland, and the people, who had been experiencing food scarcity for an extended period, were finally able to regain hope for their survival(Dong 1983e, p. 4674).16

As a consequence of the favourable outcome of his petitions, Pei composed a poem in which he extolled the virtues of the Chutan God, expressing gratitude for its role in ensuring the safety of the population of Qianzhou. Additionally, Pei facilitated the renovation of the shrine dedicated to the Chutan God, thereby enhancing the shrine’s grandeur and splendour in alignment with the identity of the local protection deity. Subsequently, he composed an article entitled “Qiyu ganying song bing xu 祈雨感應頌並序 (Ode to praying for rain and receiving the god’s blessing)”, which provided a comprehensive account of the ritual prayer and served to disseminate awareness of the Chutan God’s merits and elicit gratitude, and the text was inscribed on a stone tablet (Xie and Tao 1989, p. 2767). The erection of the stone tablet in the newly constructed shrine served two purposes. Primarily, it expressed gratitude on behalf of the officials and people of Qianzhou to the Chutan God for saving them from drought by sending rain. Secondly, it guaranteed that future generations of the local population would continue to honour and venerate the Chutan God.

5. Discussion

As previously stated, the southeastern region of China experienced prolonged droughts as a result of climate change in the eighth and ninth centuries. These conditions significantly impacted the lives of the local population, rendering their circumstances extremely challenging and causing extensive damage to the region’s social structures. In such circumstances, the local officials, represented by Dugu Ji and Pei Xu, joined with the local population and held sacrificial ceremonies for the local deities they worshipped. This ultimately resulted in the deities bestowing their blessing upon the officials, thereby enabling them to successfully assist the people in overcoming the challenging circumstances. Such occurrences were not uncommon during this period.

As Durkheim (2008, p. 517) observed, rituals facilitate the maintenance and enhancement of social cohesion. In this regard, the ritual prayers performed by officials represented a crucial measure for disaster relief, as they enabled the officials to calm the people. Nevertheless, as written by Bai (1979, pp. 1307–309), a celebrated poet of the Tang Dynasty, “while ritual prayers may offer certain advantages in dealing with minor issues, they are not a comprehensive solution to more significant challenges, such as social unrest and food shortages”.17 Bai was aware that if the populace and the government were to rely solely on entreaties to the gods for assistance, they would be unable to alleviate the full extent of the suffering caused by disasters such as droughts. The impact of droughts on both individuals and society as a whole could only be addressed if the basic survival needs of the population were met.

It is evident that, from a practical standpoint, during periods of drought, the most pressing need of the populace was access to sufficient water for the irrigation of agricultural land and the fulfilment of daily necessities. It is therefore pertinent to inquire how ritual prayers might be employed to address the needs of the people and assist them in overcoming the difficulties they face.

5.1. The Offering of Sacrifices to the Gods and the Maintenance of Public Waterworks

As previously stated, Dugu Ji initiated a prayer ceremony at the shrine of Wutang Bei 吳塘陂 in order to pay homage to the Wutang God. A review of historical records indicates that since the East Han Dynasty (25–220), the people of Shuzhou had already constructed a range of water conservancy infrastructure at Wutang Bei to intercept the Wan River 皖水 that flowed through the area, with the objective of ensuring a reliable water source for irrigation. However, the soil of Wutang Bei had such a loose composition that the dike frequently succumbed to degradation, thereby failing to fulfil its function of irrigating farmland (K. Zhang 2009, p. 1284). Consequently, prior to Dugu Ji, officials had already collaborated with the local population to initiate ritual prayers in honour of the Wutang God while simultaneously undertaking repairs and enhancements to the waterworks infrastructure.

As documented in the Taiping huanyu ji 太平寰宇記 (Universal geography of the Taiping [Xingguo] reign period, 976–983), Liu Fu 劉馥, the governor of Yangzhou 揚州, constructed the Wutang Bei irrigation system to facilitate the cultivation of rice. In addition, a renowned figure of the Three Kingdoms period, Lü Meng 呂蒙 (178–220), had excavated stones to construct a water channel, which irrigated over 300 hectares of rice paddies and significantly benefited the local population (Yue 2007, pp. 2476–77). Prior to this construction, no shrines or temples had been established in the area. Given the proximity of the Qianshan Temple 潛山廟 to Wutang Bei, the local populace offered sacrifices there to seek blessings.18 The rise of the belief in the Wutang God was associated with the construction of irrigation facilities.

From this perspective, it seems plausible to suggest that Dugu Ji’s prayers to the local deity served a purpose beyond simply seeking assistance from the gods. In the context of prolonged drought, Dugu Ji came to recognise the limitations of relying on divine intervention alone, particularly given the imminent threat to the local water infrastructure. Consequently, when Dugu Ji conducted a sacrificial ceremony for the Wutang God, he could also readily assemble a considerable number of people and resources, which were promptly used to repair the waterworks. The allocation of resources to public works, such as the reinforcement of dikes and the reclamation of lands, not only enabled the revitalisation of the pivotal role of water conservancy projects in the regulation of water sources but also resulted in a significant reduction in the impact of drought on agricultural production and the lives of the populace. It could be argued that the maintenance and preservation of public waterworks were conducted in parallel with the ritual prayers.

Similarly, in the case of Pei Xu, we can observe that, in the name of offering sacrifices to the local deity, the local official assembled a workforce of labourers to undertake public works. As previously stated, the shrine of the Chutan God was situated in an area characterised by rapid water flow, which constituted a significant hazard for navigation. In periods of drought, the utilisation of water transportation for the conveyance of foodstuffs and provisions represented a highly efficacious strategy for mitigating famine. The performance of the ritual prayer for rain at the shrine of the Chutan God was not only an act of supplication to the deity but also a means of mobilising a considerable amount of capital and labourers in a relatively brief period of time. Capital and labourers could be dedicated to maintaining and improving the waterway management projects. It had the dual benefit of improving irrigation and guaranteeing the safe passage of ships, thereby ensuring the delivery of sufficient supplies to cope with the drought and thus assisting the population in overcoming the difficulties they were facing.

During the eighth and ninth centuries, when the official sacrificial system temporarily failed, the local officials deliberately organised ritual prayers to the local deities for rainfall, which not only satisfied the local people’s preference for the blessing of a particular deity but also alleviated their suffering. More importantly, it became customary for officials in southeastern China to borrow the local deities’ influence to attract considerable human and financial resources to advance the construction of public waterworks. Using the sanctity and appeal of the local gods to rally the people to conduct water conservation projects, such as reinforcing dikes, helped to ensure agricultural production and effectively reduced the damage and impact of drought on the people.

5.2. Sacred Spaces for Local Deities and the Preservation of Waterworks

Officials regarded the performance of ritual prayers to the local deities worshipped by the local population as a source of spiritual solace. The ritual prayers also facilitated the stabilisation of a considerable workforce for the construction of water conservancy projects, thereby ensuring the protection of the populace’s daily sustenance and agricultural output. Moreover, the officials perceived the long-term functionality of water conservancy projects as a guarantee of the resilience of the local population in the face of natural disasters.

As previously stated, shrines and temples served a dual purpose: they were locations for the worship of deities and for the expression of sentiments by the government and the populace. Moreover, in order to demonstrate gratitude to the gods for their benevolence and to ensure their longevity, local officials would collaborate with the local populace to construct a more magnificent shrine and erect larger statues for the deities. Once the ritual prayer and water conservancy projects were completed, the local governors would organise the people to renovate the shrines and temples. Additionally, commemorative articles would be written to record the gods’ manifestations, which would then be engraved as stone monuments. In this manner, restored shrines and temples and recently erected monuments served to reinforce one another, collectively constituting a sacred spatial order: natural space–conceptual space–superimposed social space.

Given the interdependent relationship between shrines and temples and waterworks, the construction of sacred spaces was a crucial instrument for the safeguarding of waterworks. Local officials strategically utilised the strong connection between shrine beliefs and the local community to enhance the effectiveness of public works construction and protection. For example, during Bai Juyi’s tenure as the Governor of Hangzhou, the construction of the stone bridge on West Lake and the reinforcement of the lake embankment were successfully implemented through rituals for worshipping the local shrines and deities (Xia 2023, p. 31). The newly constructed shrines were lavishly embellished, and inscriptions on the stone tablets recounted the manifestations of the deities, enabling people to imagine their power. Local officials conducted periodic ceremonies at the shrines and temples with the objective of disseminating knowledge regarding the divine power and fostering greater reverence for the deities among the populace. Consequently, the populace would transfer their veneration of the deities to the construction and preservation of public works.

Sustained engagement with the local deities provided the local populace with a source of assurance and resilience in the face of natural disasters. The local population’s strong belief in the blessings of the gods and the necessity of maintaining their goodwill also led them to comply with the instructions of local officials and actively contribute to the maintenance and protection of water conservancy projects. This enabled the projects to function properly and ensured the provision of water for agricultural irrigation and domestic use in accordance with local conditions.

From an anthropological standpoint, rituals served as a conduit for the sustenance and growth of social structures, fostering a sense of collective identity and solidarity among its members. Durkheim (2008, p. 517) posits that the emotional states experienced by ritual participants diverge significantly from those typically experienced in non-ritualistic contexts. Following the implementation of the ritual prayers in accordance with the cultural requirements of the local population, it was determined that these prayers could not only effectively mobilise individuals to generate strong emotions, but also promote the extensive dissemination of these emotions. In the field of psychology, this phenomenon is termed “cultural fitness”.19 In addition to bathing and changing their clothes, local officials recited litany with the local people in order to pray for the gods’ blessings during the course of the ritual prayer. This sacred process served not only to further stimulate the people’s worship of the gods but also to unite their hearts. Furthermore, the holding of ritual prayers for the local gods enabled officials to rapidly amass considerable financial and human resources. The resources were subsequently allocated to the maintenance of water conservancy projects, such as Wubei Yan 吳陂堰, with the objective of reinstating the role of water conservancy projects in meeting the needs of farmland irrigation and people’s daily water usage. In essence, in a society maintained by local religious beliefs, in which individuals frequently sought the protection of the local deities, the local government was unlikely to ignore the potential influence of the local shrines and gods on social stability. Consequently, the regular performance of ritual prayers dedicated to these deities was established by the shared intention of local officials and the populace. This reinforced the bond between the government and the people and facilitated the stable development of society (Xia 2023, p. 31).

5.3. Reflection on the Function of Religion in Addressing the Contemporary Climate Crisis

With the mounting challenges of global warming and environmental degradation, which are profoundly affecting our planet, scholars have proposed that the influence of religious beliefs should be fully leveraged (Kimura 2015, pp. 129–48). The global climate crisis can only be addressed effectively through the collective action of the international community. However, the disparate natural environments and historical development of different countries make it challenging to harness the collective strength of global populations through a singular religious affiliation.

During the Tang Dynasty in China, officials in the southeastern region successfully protected the lives of the populace by organising and guiding them in coping with climatic disasters through ritual prayers to the local gods. Drawing parallels with this historical experience, we can identify valuable lessons and implement effective strategies to address the challenges posed by global warming and environmental degradation in the present context. It can be argued that ritual prayers can serve as an effective method of enhancing awareness of the crisis and increasing our determination to combat natural disasters.

However, when drawing lessons from the past, adopting a nuanced perspective can offer valuable insights. On the one hand, different countries may draw upon the religious beliefs that are characteristic of their own cultures to organise and guide their people to act collectively. Religion can play a role in redirecting societal activities that are harmful to the natural environment while fostering harmonious coexistence between humans and nature, and the establishment of a sustainable development state. It is therefore essential for governments worldwide to acknowledge the potential ability of diverse local religions to influence individuals to address the climate crisis and improve the environment for future generations.

On the other hand, in view of the significant decline in religious ritual knowledge in certain countries and the growing disbelief in such rituals among younger generations, it may prove challenging to mobilise large numbers of individuals using the influence of religion for large-scale public works initiatives. It is therefore recommended that the state make full use of the power of religion while also investing more financial resources to provide adequate benefits to people participating in public works. This would serve to further inspire them to participate in disaster relief and environmental protection.

6. Conclusions

Traditional Chinese rain-making rituals have always been understood as an instrumental activity for the induction of rain, serving as an important medium for connecting the officials, the commoners, and the gods, as strongly evidenced by the large number of historical records and existing studies on rain-making rituals in China. The traditional custom of officials praying to the gods for rain in ancient China provides an invaluable lens through which to examine how local governments employed religious beliefs to respond to climate crises. The ritual prayers performed by officials in honour of such deities were able to make a powerful call to arms, gathering a large number of people to pray together within a short period of time. The majority of people considered these ritual prayers to be of great spiritual significance.

Throughout the entirety of the ceremony, local officials were obliged to recite the sacrificial text in public, thereby imploring the gods for divine blessing. This served to reinforce the ceremony’s sacred nature. The highly performative nature of the ceremony enabled residents to perceive the officials’ determination in combating the drought while simultaneously creating an atmosphere in which the gods were perceived as about to bestow their blessing upon them in the face of disaster. It can be argued that, in the face of disaster, the ritual prayer itself constitutes a social self-help activity (Sun 2009, pp. 120–22), which acts as a calming agent and can pacify the populace in the initial stages of a disaster.

Nevertheless, it is not possible to respond effectively to climatic disasters by relying on prayer alone. Consequently, following the conclusion of the prayer ceremony, the officials would also utilise the calling power of the local gods to gather the people and complete public works, such as reclaiming lands and constructing dikes and ponds. The purpose of this was to ensure the recovery of agricultural production and, ultimately, to enable the population to survive the year of disaster. Once the ritual prayers and public works had been completed, the officials would also draft commemorative articles for the local deities, which would then be inscribed on monuments. This would result in the formation of a sacred space that would serve to emotionally inspire and perpetuate the efforts of the officials and the people in their ongoing battle against all forms of natural disasters.

More importantly, the Tang Dynasty’s utilisation of the local deities to address climate crises offers a valuable precedent for contemporary efforts to mitigate the intensifying climate crisis. By focusing on religious beliefs with national characteristics, governments worldwide could encourage collective action to reduce damage to the natural environment and to create public works that counteract all kinds of natural disasters. This would help to achieve a harmonious coexistence between human beings and nature, as well as sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L. and Y.X.; funding acquisition, Z.L. and Y.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Postdoctoral Fellowship Program [GZC20230597]. And The APC was funded by Guangdong Philosophy and Social Science Foundation Regular Program [GD24YWL01].

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 | The Tang Dynasty was a flourishing, open feudal empire. It is regarded as one of the most prominent and powerful states in world history, exhibiting a robust and flourishing state apparatus, a thriving economy, an active foreign policy, and significant institutional advancements. |

| 2 | Whether or not the worship of gods in ancient China was a religion is of major importance to anyone studying the history of religion, or Sinology. Some religious studies scholars deny that the Chinese are religious or believe in God(s). In fact, since the Shang Dynasty in China, the Chinese have constructed a world of belief centred on their ancestors, water, fire, and so forth. These entities were designated as possessing mystical capabilities, venerated as deities, and the subject of offerings and pilgrimages. It can be posited that the worship of deities constituted a significant aspect of the daily lives of the ancient Chinese. There is abundant research on this topic: see (Puett 2002; Clark and Winslett 2023; Lagerwey and Kalinowski 2009). |

| 3 | The Datang Kaiyuan Li states that “in the event of a drought in the capital area after the fourth month of the lunar calendar, ritual prayers were made in the northern suburbs to the gods of the mountains, seas, and rivers. These deities were considered capable of producing clouds and rain, and people would look in their direction and pray to them. Meanwhile, ritual prayers were also made to the gods of earth and grain, and the ancestral deities. In the event of a protracted drought, additional ritual prayers were made to the gods of mountains, rivers and seas, in the same manner as the initial prayers. The ritual of praying for rain was held in the event of a major drought, but not after the autumn equinox. In the event of persistent drought, the marketplace was relocated, the slaughter of livestock was prohibited, the production of umbrellas and fans was suspended, and earthen dragons were employed as a means of petitioning for rain. Once sufficient rainfall had been achieved, a ritual was conducted to express gratitude to the deities. Offerings of wine, dried meat, and minced meat were integral to these prayers, and regular sacrifices were held to express gratitude to the gods for their benevolence. These rituals were meticulously orchestrated and executed by the designated authorities. If it rained before the end of the fast, then sacrifices were held in each rainfall area to show gratitude to the gods. Whenever drought occurred in prefectures and counties, people must first pray for rain to the gods of the soil and grain, and then to the gods of mountains and rivers within the territory that could bring clouds and rain. All other rituals should follow the precedents set in the capital”. The original text is written as 凡京都孟夏已后,旱则祈岳镇海渎及诸山川能兴雨者,于北郊望而告之。又祈社稷,又祈宗庙,每七日皆一祈。不雨,还从岳渎如初。旱甚则修雩,秋分以后不雩。初祈一旬不雨,即徙市,禁屠杀,断繖扇,造土龙。雨足则报祀。祈用酒脯醢,报用常祀,皆有司行事。已斋及未祈而雨,及所经祈者皆报祀。凡州县旱则祈雨,先社稷,又祈界内山川能兴云雨者,馀准京都例. See (Xu 2000, p. 32). |

| 4 | The original text is written as 天子祭天地,祭四方,祭山川,祭五祀,歲偏。諸侯方祀,祭山川,祭五祀,歲偏。大夫祭五祀,歲偏。士祭其先。凡祭,有其廢之,莫敢舉也;有其舉之,莫敢廢也, see (Liu 2016, p. 37). |

| 5 | The Qin Dynasty is notable for its establishment of the first unified empire in ancient China. It is widely regarded as having laid the foundation for China’s imperial system, which would persist for a period of more than 2000 years. |

| 6 | Taizhu 太祝, also known as Dazhu 大祝, was an official in charge of rituals and prayers in ancient China, as recorded in the Zhou li. See (Ruan 2009, p. 1746). |

| 7 | The original text is written as 及秦並天下,令祠官所常奉天地名山大川鬼神可得而序也……諸此祠皆太祝常主,以歲時奉祠之。至如他名山川諸鬼及八神之屬,上過則祠,去則已, see (Sima 1959, pp. 1371–77). |

| 8 | The original text is written as 郡縣遠方神祠者,民各自奉祠,不領於天子之祝官, see (Sima 1959, p. 1377). |

| 9 | The original text is written as 麻姑手爪不如人爪,形皆似鳥爪……麻姑神人也, see (H. Ge 2010, p. 95). |

| 10 | The original text is written as 麻源第三谷,恐其處也。源口有神,祈雨輒應……天寶五載,投龍於瀑布,石池中有黃龍見。元宗感焉,乃命增修仙宇真儀侍從雲鶴之類, see (Dong 1983b, p. 3424). |

| 11 | For instance, an order of banning the local shrines was issued during the reign of the Emperor Taizong (599–649) of the Tang Dynasty. The original text is written as 詔私家不得輒立妖神,妄設淫祀,非禮祠禱,一皆禁絕, see (Z. Zhang 1975b, p. 31). |

| 12 | Following the establishment of the Tang Dynasty, the government divided administrative districts with Dao 道 or circuit. From the eighth century onwards, circuit became the local administrative organ of the major prefectures. |

| 13 | This chart is principally derived from the Jiu tang shu, the Compilation of Tombstones of the Tang Dynasty, and the Cefu yuangui 册府元龟 (Prime Tortoise of the Record Bureau). The data retrieval was mainly conducted using keywords such as “buyu 不雨 lack of rain”, “ganhan 干旱 drought”, and “dahan 大旱 severe drought”. Subsequently, the drought situations that occurred in the Lingnan Circuit, Huainan Circuit, and Jiangnan Circuit were selected and analyzed statistically in order to create this chart. |

| 14 | The original text is written as 獨孤及,謹以清酌之奠,敢昭告於吳塘神之靈今盛夏旱蒸,五稼將枯。田畯訴號,靡知其辜。神明豈不降鑑下土,油然爲雲,沛然作雨。使萬人歡康,百穀阜滋。灑我公田,遂及我私。我京我庾,維萬維億。豈伊人粒,神亦血食。衆心顒顒,非歲曷望。望之濟否,惟神所相。尚饗, see (Dugu 2007, p. 409). |

| 15 | The original text is written as 質明齋服躬往奠,牢醴豐潔精誠舉。女巫紛紛堂下舞,色似授兮意似與, see (Peng 1960, p. 10022). |

| 16 | The original text is written as 入廟而驕陽猶赫,陳祠而元(玄)冥召陰。我信既孚,伊神降祉。乾坤合德,風雨應期。表以隨車,雲不待族。昭其福善,雷無假震。越翼日而滂沱, see, (Dong 1983e, p. 4674). |

| 17 | The original text is written as 至若祈禱之術……但可以濟小災小弊,未足以救大危大荒, see (Bai 1979, pp. 1307–9). |

| 18 | The original text is written as揚州刺史劉馥開吳陂以溉稻田。又云“呂蒙鑿石通水,注稻田三百餘頃,功利及人”。先未立廟,里人以潛山廟在吳陂之側,因指名以祀焉, see (Yue 2007, pp. 2476–77). |

| 19 | “Cultural fitness” of a mental representation can be inferred from its successful transmission through the population. See (Henrich et al. 2008). |

References

- Bai, Juyi 白居易. 1979. Celin, yi 策林一 (Political proposals, first). In Bai Juyi ji 白居易集 (The Essay Collection of Bai Juyi). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 62, pp. 1307–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bujard, Marianne. 2011. State and local cults in Han religion. In Early Chinese Religion, Part One: Shang Through Han (1250BCE to 22AD). Edited by John Lagerwey and Marc Kalinowski. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Zongxian 蔡宗憲. 2007. Yinsi, yingci yu sidian: Hantang jian Jige cisi gainian de lishi kaocha 淫祀、淫祠與祀典:漢唐間幾個祠祀概念的歷史考察 (Immoral ritual prayers, immoral temples and prayer scriptures: A historical study of concepts of ritual prayers and temples during the Han-Tang period). Tang yanjiu 唐研究 (The Study of the Tang Dynasty) 13: 203–32. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Kelly James, and Justin Winslett. 2023. A Spiritual Geography of Early Chinese Thought: Gods, Ancestors, and Afterlife. London: Bloomsbury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Gao 董誥, ed. 1983a. Dugu Ji shendao beiming 故常州刺史獨孤公神道碑銘 (Inscription of Dugu Ji’s mausoleum). In Quan tang wen 全唐文 (Complete Collection of All Preserved Prose Literature of the Tang Dynasty). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 409, pp. 4195–97. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Gao 董誥, ed. 1983b. Fuzhou nancheng xian magu shan xiantan ji 撫州南城縣麻故山仙壇記 (The note of the shrine of Magu Mountain at Nancheng County, Fuzhou). In Quan tang wen 全唐文 (Complete Collection of All Preserved Prose Literature of the Tang Dynasty). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 338, pp. 3423–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Gao 董誥, ed. 1983c. Jian huainan zuyong dishui zhi 減淮南租庸地稅制 (The rule of reducing tax of Huainan Region). In Quan tang wen 全唐文 (Complete Collection of All Preserved Prose Literature of the Tang Dynasty). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 414, p. 4245. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Gao 董誥, ed. 1983d. Ming zhangli qiyu zhao 命長吏祈雨詔 (An edict of ordering officials to pray for rain). In Quan tang wen 全唐文 (Complete Collection of All Preserved Prose Literature of the Tang Dynasty). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 73, p. 765. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Gao 董誥, ed. 1983e. Qiyu ganying song bing xu 祈雨感應頌並序 (Ode to praying for rain and receiving the god’s blessing). In Quan tang wen 全唐文 (Complete Collection of All Preserved Prose Literature of the Tang Dynasty). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 457, p. 4674. [Google Scholar]

- Du, You 杜佑. 1988. Tongdian 通典 (Encyclopaedia of Institutional Texts). Qidao 祈祷 (Ritual Prayers). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 108. [Google Scholar]

- Dugu, Ji 獨孤及. 2007. Ji wutang shen wen 祭吳塘神文 (Sacrificial text of the Wutang God). In Kunling ji jiaozhu 毘陵集校註 (Annotation of the Kunling Anthology). Shenyang: Liaohai Press, vol. 19, p. 409. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Emile. 2008. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eno, Robert. 1990. The Confucian Creation of Heaven: Philosophy and the Defense of Ritual Mastery. New York: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feuchtwang, Stephan. 1977. School-Temple and City God. In The City in Late Imperial China. Edited by George William Skinner. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 584–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Hong 葛洪. 2010. Shenxian zhuan 神仙傳 (The Legend of the Immortals). Beijing: China Bookstore. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Zhaoguang 葛兆光. 2000. Zhongguo sixiang shi 中國思想史 (History of Chinese Thought). Shanghai: Fudan University Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Graff, David A. 2002. Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300–900. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Valerie. 1993. Review of Barend J. Ter Haar: The White Lotus Teachings in Chinese Religions History. T’oung Pao 79: 374. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Valerie. 2014. Changing Gods in Medieval China, 1127–1276. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, Joseph, Robert Boyd, and Peter J. Richerson. 2008. Five misunderstandings about cultural evolution. Human Nature 19: 119–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Ze, Edward Slingerland, and Joseph Henrich. 2024. Magic and empiricism in early Chinese rainmaking—A cultural evolutionary analysis. Current Anthropology 65: 343–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sang-Bum 긴상범. 2006. Tangdai cimiao zhengce de bianhua: Yi cihao cie de yunyong wei zhongxin 唐代祠廟政策的變化—以賜號賜額的運用為中心 (Changes in policies of shrines and temples in the Tang Dynasty: With the focus on the acts of conferring titles and bestowing tablets). Songshi yanjiu luncong 宋史研究論叢 (The Song History Research Series) 7: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, Takeshi 木村武史. 2015. A Reflection on a Study of “Religion and Environment”. Jakarta Studies in Philosophy 3: 152–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lagerwey, John, and Marc Kalinowski. 2009. Early Chinese Religion. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Yong 藍勇. 2001. Tangdai qihiu bianhua yu tangdai lishi xingshuai 唐代氣候變化與唐代歷史興衰 (Climate change and the rise and fall of the Tang Dynasty). Zhongguo lishi dili luncong 中國歷史地理論叢 (Journal of Chinese Historical Geography) 1: 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Wen 雷聞. 2009. Jiaomiao zhi wai: Suitang guojia jisi yu zongjiao 郊廟之外:隋唐國家祭祀與宗教 (Beyond the Suburbs’ Temples: The State Ritual Prayers and Religion of the Sui-Tang Period). Shanghai: Sanlian Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fang 李昉, ed. 1956. Dugu gong xingzhuang 獨孤公行狀 (The brief biographical sketch of Dugu Ji). In Wenyuan yinghua 文苑英華 (Finest Blossoms in the Garden of Literature). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 972, pp. 5115b–5117b. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fang 李昉. 1961. Taiping guangji 太平廣記 (Extensive Records of the Taiping [Xingguo] Reign Period, 976–983). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Store, vol. 447. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Linfu 李林甫, ed. 1992. Tang liudian 唐六典 (The Six Rules of the Tang Dynasty). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yin 李殷. 2018. Tang houqi yingzai zhengce de yanbian ji qi shijian tanxi: Yi jianghuai diqu wei zhongxin 唐後期應災政策的演變及其實踐探析—以江淮地區為中心 (The evolution and practice of disaster preparedness in the late Tang Dynasty: With a focus on the Jianghuai region). Zhongguo shehui jingjishi yanjiu 中國社會經濟史研究 (Chinese Social and Economic History Review) 2: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yuan 劉沅. 2016. Shisanjing hengjie: Zhanjie ben, liji heng jie 十三經恒解 (The Standard Explanation of the Thirteen Classics). Quli, xia 曲禮下 (The Rites of Music, Part 2). Sichuan: Bashu Bookstore, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Xian 毛憲, ed. 2013. Piling renpin ji 毗陵人品記 (The Note of the People of Piling). Nanjing: Fenghuang Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Xiu 歐陽修. 1975. Wuxingzhi, er 五行誌二 (Annals of five element, second). In Xin tang shu 新唐書 (The New Book of the Tang Dynasty). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 35, pp. 897–925. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Dingqiu 彭定求, ed. 1960. Quan tang shi 全唐詩 (The Complete Collection of Poems of the Tang Dynasty). Chutan miao 儲譚廟 (Chutan Temple). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 887. [Google Scholar]

- Puett, Michael J. 2002. To Become a God. Boston: Harvard University Asia Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Romen, Taylor. 1997. Office Altars, Temple and shrine Mandated for All Countries in Ming and Qing. T’oung Pao 89: 93–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Yuan 阮元. 2009. Shisan jing zhushu 十三经注疏 (Commentaries and Explanations to the Thirteen Classics). Zhouli zhushu 周礼注疏 (Commentaries and Explanations to the Rites of the Zhou Dynasty). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, Qian 司馬遷. 1959. Shi ji 史記 (The Records of the Grand Historian). Beijing: China Bookstore. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder-Reinke, Jeffrey. 2009. Dry Spells: State Rainmaking and Local Governance in Late Imperial China. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Junhui 孫軍輝. 2009. Tangdai shehui qiyu huodong tanxi唐代社會祈雨活動探析 (A study of praying for rain in the society of the Tang Dynasty). Hubei shehui kexue 湖北社會科學 (Hubei Social Science) 10: 120–22. [Google Scholar]

- Toynbee, Arnold J. 1987. A Study of History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Ying 魏瀛, and Yinhong Zhong 鍾音鴻, eds. 1970. [Tongzhi] ganzhou fuzhi (同治) 贛州府誌 ([Tongzhi Reign (1862–1874)] Annals of Ganzhou Fu). Vol. 12. Songren Huang Qingji chongxiu guangji miao ji 宋人黃慶基重修廣濟廟記 (Record of the Reconstruction of Guangji Temple by Huang Qingji from the Song Dynasty). Taibei: Chengwen Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Zheng 魏征, ed. 1973. Dilizhi, xia 地理誌下 (Annals of geography, part 2). In Sui shui 隋書 (The Book of the Sui Dynasty). Beijing: China Bookstore, p. 880. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Yan 夏炎. 2023. Bai Juyi jilong yiyu yu tanghouqi jiangnan difang zhili 白居易祭龍祈雨與唐後期江南地方治理 (Bai Juyi’s ritual prayers to the Long for rain and the local governance of Jiangnan region during the late Tang Dynasty). Journal of Shanxi University 4: 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Min 謝旻, and Cheng Tao 陶成. 1989. [Yongzheng] jiangxi tongzhi (雍正) 江西通志 ([Yongzheng Emperor’s Reign (1678–1735)] Annals of Jiangxi Province). Taibei: Chengwen Press, vol. 142. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Jian 徐坚. 2000. Datang kaiyuan li 大唐开元礼 (The Rites of the Kaiyuan Reign of the Tang Dynasty). Beijing: Nationality Press, vol. 3, p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Shoucheng 閻守誠. 2008. Weiji yu yingdui: Ziran zaihai yu tangdai shehui 危機與應對:自然災害與唐代社會 (Crises and Response: Nature Disasters and the Tang Dynasty Society). Beijing: Renmin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yancheva, Gergana, Norbert R. Nowaczyk, Jens Mingram, Peter Dulski, Georg Schettler, Jörg F. W. Negendank, Jiaqi Liu, Daniel M. Sigman, Larry C. Peterson, Gerald H. Haug, and et al. 2004. Influence of the intertropical convergence zone on the East Asian monsoon. Nature 445: 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Junfeng 楊俊峰. 2019. Tangsong zhijian de guojia yu cisi: Yi guojia he nanfang sishen zhifeng hudong wei jiaodian 唐宋之間的國家與祠祀:以國家和南方祀神之風互動為焦點 (State, Shrine and Ritual Prayer Between the Tang and Song Periods: The Interaction Between the State and the Southern Style of Sacrificing the Gods). Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Liangsheng. 1957. The Concept of “Pao” as a Basis for Social Relations in China. In Chinese Thought and Instituions. Edited by John K. Fairbank. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 291–309. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Shi 樂史. 2007. Huainan Dao, san, Shuzhou, Huaining Xian 淮南道三·舒州·懷寧縣 (Huainan circuit, third, Shuzhou, Huaining county). In Taiping huanyu ji 太平寰宇記 (Universal Geography of the Taiping [Xingguo] Reign Period, 976–983). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 125, pp. 2476–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Jiacheng 張家誠. 1982. Qihou bianhua dui zhongguo nongye shengchan yingxiang chutan 氣候變化對中國農業生產影響的初探 (Possible impacts of climate variation on agriculture in China). Dili xuebao 地理學報 (Geography Journal) 1: 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Kai 張楷, ed. 2009. [Kangxi] anqing fuzhi (康熙) 安慶府誌 ([Kangxi Reign (1662–1722)] Annals of Anqing Fu). Vol. 26, Qianshan xinkai wutang shiju ji 潛山新開吳塘石渠記 (Record of the Newly Opened Wutang Stone Canal in Qingshan). Beijing: China Bookstore. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Min 張敏. 2019. Tangdai jiangnan diqu de qiuyu fengsu 唐代江南地區的求雨風俗研究 (A study of the customs of rain-praying in the Jiangnan region during the Tang Dynasty). Shehui kexue dongtai 社會科學動態 (Dynamics of Social Science) 4: 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Pingzhong, Hai Cheng, R. Lawrence Edwards, Fahu Chen, Yongjin Wang, Xunlin Yang, Jian Liu, Ming Tan, Xianfeng Wang, Jinghua Liu, and et al. 2008. A Test of Climate, Sun, and Culture Relationships from an 1810-year Chinese Cave Record. Science 322: 940–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Zhao 張昭, ed. 1975a. Di renjie zhuan 狄仁傑傳 (Biography of Di Renjie). In Jiu tang shu 舊唐書 (The Old Book of the Tang Dynasty). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Zhao 張昭, ed. 1975b. Taizong, shang 太宗上 (The emperor of Taizong of the Tang Dynasty, first). In Jiu tang shu 舊唐書 (The Old Book of the Tang Dynasty). Beijing: China Bookstore, vol. 89. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).