Fact, Fiction, and Legend: Writing Urban History and Identity in Medieval and Renaissance Siena

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Origin and Controversy of Siena’s Historical Legends

2.1. Historical Absence and Siena’s Identity

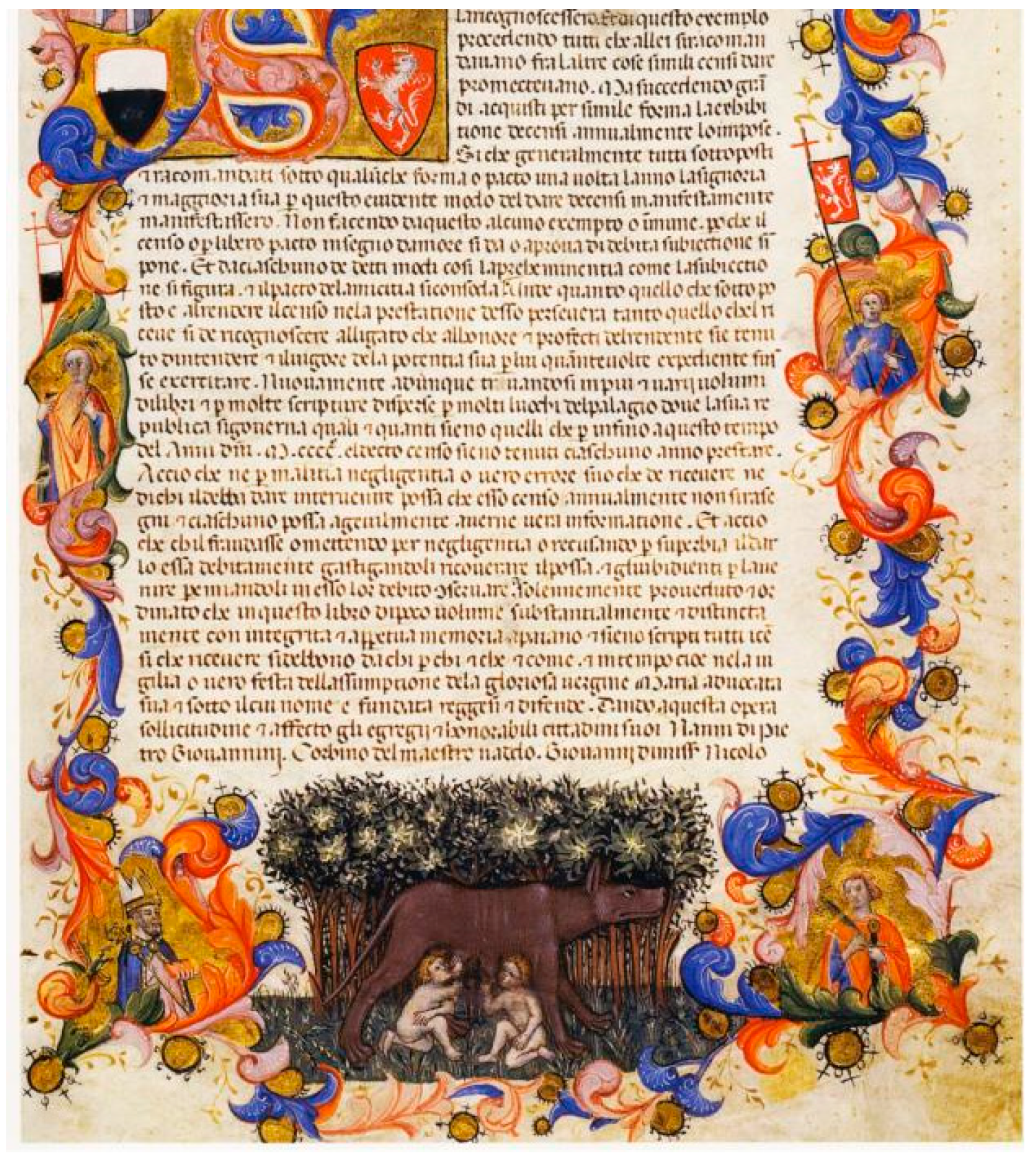

2.2. Controversy About the Origin of the ‘She-Wolf and the Twins’ Legend

2.3. ‘Secularising’ the Legend of Saint Ansanus

3. Characterisation and Construction of the Sienese Legend in Urban Historiography

3.1. Combining Fiction and Historical Biography

3.2. Art in Public Spheres

4. Immediate Impact: The Influence of Historical Writing and the Reconstruction of Siena’s Identity

4.1. Travelogues and Scholarly Works

4.2. Memory and City Spirit

5. Summary and Implications

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The “Constructivism” theory, as proposed by Hayden White, posits that the act of writing memory constitutes a form of “fiction” and “myth.” Conversely, the concept of “Material Mediators” encompasses the cultural landscape, which refers to the process by which humans reconstruct space by embedding elements such as customs, traditions, and lifestyles into the landscape. This process, therefore, results in the landscape becoming not only a material heritage but also a new cultural heritage, with the capacity to connect historical memory. See: Zhao (2021). |

| 2 | The claim that Siena originated from the Franks can be traced to the 12th-century English scholar John of Salisbury. In the sixth book of his Policraticus, he attributed the city’s founding to the Gallic leader Brennus. This account was later embraced and widely disseminated during the Renaissance by notable figures such as Giovanni Villani, Dante, and Boccaccio. Criticism of Siena’s historical narrative often highlights its alleged bloodline connection to France, contrasting it with the Roman heritage traditionally linked to Italy (John of Salisbury 1990, pp. 6, 17). |

| 3 | Ansano/Ansanus (285–304 AD) was a Roman nobleman by birth and is regarded as the first Christian to preach in Siena. He is believed to have been persecuted and martyred in Siena by the Roman Emperor Diocletian, making him the first patron saint of Siena. Ansano’s martyrdom marks a significant turning point in Siena’s transition from the Roman Empire to Christianity. His identity embodies both the universality of the Christian faith and the religious transformation of the late Roman Empire. In commemorating Ansano, Siena affirms its commitment to early Christian heritage and, through his martyrdom, situates itself within the historical context of the Christianisation of the Roman Empire. This narrative not only reinforces Siena’s religious orthodoxy but also challenges any notion of Siena’s historical absence, ‘localising’ the transformation of Rome and subtly linking the city’s origins to that of Rome. |

| 4 | The earliest recorded seal depicting the She-Wolf and the Twins is dated 1344 (Miscellanea storica senese 1895, p. 195). |

| 5 | The secular and the religious were not strictly opposed during this period, as illustrated by another of Siena’s religious symbols—the Virgin Mary. Her image was not merely a vestige of religious tradition but a political instrument deliberately employed by the government of the Nine to reinforce its authority. This is particularly evident in the Marian frescoes of Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico, where religious symbolism was not simply preserved but actively integrated into municipal governance. These frescoes ascribed to the Virgin a protective role over the city and its government, transforming religious imagery into a means of legitimising political power. Rather than discarding religious elements, the Nine strategically incorporated the figures of the Virgin Mary and Saint Ansanus into civic identity, intertwining religious devotion with secular governance to consolidate their rule (Bohn and Saslow 2013, pp. 71–72). |

| 6 | The Roman Porta, which exists today in Siena, was built in August 1328 by Agnolodi Ventura and Agostino di Giovanni to replace the destroyed Porta di San Martino. Differences in sculptural form: Roman she-wolves tend to have their heads tilted to one side, while those in Siena are in a forward position. |

| 7 | At the close of the 14th century, Milan and Florence were embroiled in conflict, with the polemics of their respective humanists expanding the battlefront to culture and public opinion. Notably, Antonio Loschi (1365–1441), secretary to the Duke of Milan at the time, published L’Invectiva in Florentinos (Reproach to the Florentines), to which Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406), secretary of state in Florence, responded with a rejoinder, thereby sparking further polemics. Loschi argued that Milan had a more ancient Roman heritage than Florence and denounced the republican myth of Florence’s supposed inheritance of Roman tradition as a later fabrication. He pointed out that Florence, despite its republican identity, was also expansionist and allied with France, demonstrating Florence’s hypocrisy and lack of a clear Italian stance. For Sarutati’s reply to Loschi, see: Coluccio Salutati (2014). |

| 8 | The official tourism website and brochures of Siena feature the city’s origins through the legend of the twin brothers Aschius and Senius. Resource: https://visitsienaofficial.it/siena-toscana/ (11 October 2024) “Una leggenda avvolge le origini di Siena: è quella di Senio e Ascanio, figli di Remo e nipoti di Romolo, che avrebbero fondato la città dopo essere fuggiti dalle intenzioni omicide del loro zio a Roma, portandosi dietro il simbolo della Lupa capitolina, che per questo motivo è divenuta il simbolo di Siena come Lupa senese”. |

References

- Achilli, Alessandro, Anna Olivieria, Maria Palaa, Ene Metspalub, Simona Fornarinoa, Vincenza Battagliaa, Matteo Accetturoa, Ildus Kutuevb, Elsa Khusnutdinovac, Erwan Pennarunb, and et al. 2007. Mitochondrial DNA Variation of Modern Tuscans Supports the Near Eastern Origin of Etruscans. American Journal of Human Genetics 80: 766–67. [Google Scholar]

- Alighieri, Dante. 1991. Commedia: Inferno. In Letteratura italiana Einaudi. Edizione di riferimento: I Meridiani, I edizione. Milano: Mondadori, p. 699. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Carol A. 2019. Sacred Histories: Remembering the Christian Past in Medieval Tuscany (1100–1500). Washington, DC: The Catholic University, pp. 249–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ascheri, Mario, and Bradley Franco. 2020. A History of Siena: From Its Origins to the Present Day. New York: Routledge, pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, Aleida. 2002. The History in Memory: From Personal Experience to Public Presentation. Translated by Siqiao Yuan. Nanjing: Nanjing University Press, p. 171. [Google Scholar]

- Bargagli Petrucci, Fabio. 1906. Notizie di un Arco Romano in Siena. Rassegna D’arte Senese, vol. 2, It was not until the 19th century that archaeological techniques, through the analysis of fragments in the columns, established that these columns were in fact 15th century works and not the remains of the so-called Roman colonial period.

- Bartfield, Herbert. 2012. The Whig Interpretation of History. Translated by Yueming Zhang, and Beicheng Liu. Beijing: The Commercial Press, pp. 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Baluze, Etienne, and Giovan Domenico Mansi, eds. 1764. Stephani Balugii Tutelensis Miscellanea: Noro ordine digesta et non paucis ineditis monumentis opportunisque animadversionibus aucta. Sancti Ansani, trans. Lucae: Junctinium, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Beneš, Carrie E. 2011. Urban Legends: Civic Identity & the Classical Past, 1250–1350. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bezzini, Mario. 2015. Controversia territoriale tra i vescovi di Siena ed Arezzo dal VII al XIII secolo. Florence: Il Leccio. Available online: https://www.unilibro.it/libro/bezzini-mario/controversia-territoriale-vescovi-siena-ed-arezzo-vii-xiii-secolo/9788898217380?srsltid=AfmBOopf-Ab_0u5c7mTJ6nE6zQPxL94IrRlwWJ_6lrfH5Raw6dhKBRfN (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Biccherna. 1344. Tavole di Biccherna. Siena: Archivio di Stato di Siena, No. 215, c. 148. December 20. [Google Scholar]

- Biondo, Flavio. 2005. Italy Illuminated. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Boccaccio, Giovanni. 1846. Chiose sopra Dante. Firenze: Tipografia all’Insegna di Dante, pp. 241–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bohn, Babette, and James M. Saslow, eds. 2013. A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bowsky, William M. 1981. A Medieval Italian Commune: Siena Under the Nine, 1287–1355. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Peter. 2019. History and Social Theory. Translated by Li Kang. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, p. 182. [Google Scholar]

- Caferro, William. 1998. Mercenary Companies and the Decline of Siena. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cantucci, Giuliana. 1961. Considerazioni sulle trasformazioni urbanistiche nel centro di Siena. BSSP 68: 251–62. [Google Scholar]

- Casciani, Santa, and Heather Richardson Hayton, eds. 2021. A Companion to Late Medieval and Early Modern Siena. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, Keith, Laurence B. Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke, eds. 1988. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art: Distributed by H.N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Coluccio Salutati, Rolf Bagemihl, trans. 2014. Political Writings. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connerton, Paul. 2000. How Societies Remember. Translated by Nari Bilige. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- D’Accone, Frank A. 2007. The Civic Muse: Music and Musicians in Siena During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Montaigne, Michel. 2017. The Complete Essays of Montaigne. Translated by Ma Zhencheng. Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- de Roover, Raymond. 1942. The Commercial Revolution of the Thirteenth Century. Bulletin of the Business Historical Society 16: 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Langton. 1902. A Story of Siena. New York: E.P. Dutton Company. [Google Scholar]

- Frugoni, Chiara. 2019. Paradiso vista Inferno: Buon governo e tirannide nel Medioevo di Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Funari, Rodolfo. 2002. Un ciclo di tradizione repubblicana nel Palazzo Pubblico di Siena. Le iscrizioni degli affreschi di Taddeo di Bartolo (1413–1414). Siena: Accademia Senese Degli Intronati. [Google Scholar]

- Geary, Patrick J. 2018. History, Memory, and Writing. Translated by Xin Luo. Beijing: Peking University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gori, Giovanni Battista. 1576. Vita del gloriosissimo S. Ansano: Uno de li quattro Avvocati e Battezzatore de la città di Siena. Siena: Luca Bonetti, p. 2. Available online: https://edit16.iccu.sbn.it/resultset-titoli/-/titoli/detail/CNCE21468 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Gigli, Girolamo. 1732. Diario Senese, vol. 2. Bologna: Arnoldo Forni. [Google Scholar]

- Gigli, Girolamo. 1854. Diario Senese (1723). Bologna: Arnoldo Forni. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, Max Elijah. 2006. Pro Honore Comunis Senensis Et Pulchritudine Civitatis: Civic Architecture and Political Ideology in the Republic of Siena, 1270–1420. New York: Columbia University, p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini, Roberto. 2000. Dulci pro libertate. Taddeo di Bartolo: Il ciclo di eroi antichi nel Palazzo Pubblico di Siena (1413–1414). Tradizione classica ed iconografia politica. Rivista Storica Italiana 112: 510–68. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood, William. 1924. Guide to Siena, History and Art, 4th ed. Siena: Libreria. [Google Scholar]

- Hoare, Sir Richard Colt. 1819. A Classical Tour through Italy and Sicily, 2nd ed. London: J. Mawman, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- John of Salisbury. 1990. Policraticus. Edited by Cary J. Nederman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 6, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Geraldine A. 2015. Art of the Renaissance. Translated by Li Jianqun. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Philip. 1997. The Italian City-State: From Commune to Signoria. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lassels, Richard. 1670. The Voyage of Italy. Paris: John Starkey. [Google Scholar]

- Lisini, Alessandro, and Fabio Iacometti, eds. 1931–1939. Rerum Italicarum Scriptores. Bologna: Forni Editore, vol. 15, Part 6. [Google Scholar]

- Magdalino, Paul. 2002. The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 1143–1180. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Malavolti, Orlando. 1968. Dell’Historia di Siena (1594). Bologna: Forni. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1948. Magic, Science, and Religion and Other Essays. Beacon: Beacon Press, pp. 125–26. [Google Scholar]

- Miscellanea storica senese, vol. 1. 1893. Siena: Stab. Tip. Carlo Nava.

- Miscellanea storica senese, vol. 3. 1895. Siena: Stab. Tip. Carlo Nava.

- Milanesi, Gaetano. 1873. Sulla Storia Dell’Arte Toscana: Scritti varj. Siena: Davaco Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, Lewis. 2004. The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects. Translated by Junling Song, and Wenyi Ni. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press, p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- Nevola, Fabrizio. 2000. Revival or Renewal: Defining Civic Identity in Fifteenth-Century Siena. In Shaping Urban Identity in Late Medieval Europe. Edited by Marc Boone and Peter Stabel. Leuven: Garant Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Nevola, Fabrizio. 2008. Siena: Constructing the Renaissance City. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 157–73. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Gerald. 2004. Siena, Civil Religion and the Sienese. Derbyshire: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Gerald. 2006. Civil Religion and the Invention of Tradition: The Festival of Saint Ansano in Siena. Journal of Contemporary Religion 21: 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, Samantha. 2023. Popular Participation in Renaissance Siena’s Romanitas Program. Explorations in Renaissance Culture 49: 175–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondoni, Giuseppe. 1886. Tradizioni popolari e leggende di un comune medioevale e del suo contado: Siena e l’antico contado senese. Firenze: Uffizio della Rassegna nazionale. [Google Scholar]

- Schevill, Ferdinand. 1909. Siena: The History of a Medieval Commune. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Sozzini, Alessandro, ed. 1842. Diario delle cose avvenute in Siena dal 20 luglio 1550 al 28 giugno 1555. Firenze: Gio. Piero Vieusseux. [Google Scholar]

- Starn, Randolph, and Loren Partridge. 1992. Arts of Power: Three Halls of State in Italy, 1300–1600. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff, Judith B. 2000. Sienese Painting After the Black Death: Artistic Pluralism, Politics, and The New Art Market. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart, Simon K. F. 2009. Historical Dictionary of the Etruscans. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press. [Google Scholar]

- Toynbee, Paget, ed. 1903. The Letters of Horace Walpole. Fourth Earl of Orford, vol. 1, Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trombelli, Joanne Chrysostomo, ed. 1766. Ordo Officiorum Ecclesiae Senensis ab Oderico ejusdem ecclesiae canonico anno MCCXIII compositus. Bologna: Ex typographia Longhi, pp. 304, 273. [Google Scholar]

- Villani, Giovanni. 1991. Nuova Cronica. Edited by Pietro Bembo. Parma: Guanda, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, Diana. 1996. Patrons and Defenders: The Saints in the Italian City-States. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Ming. 2023. Carnival in Rome: The Tension of Pope Paul II’s Dual Role Revisited. Religions 14: 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdekauer, Lodovico. 1897. Constituto del commune di Siena dell’anno 1262. Milano: U. Hoepli. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Zhengyuan. 2021. Cultural Landscape and Urban Memory: The Memory Reconstruction of Pukou Railway Station in Nanjing. Historical Review 6: 91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Jingwen, ed. 2010. Introduction to Folklore, 2nd ed. Beijing: Higher Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Ming. 2011. From Cathedral to City Hall: The Spatial Transformation of Siena in the Late Middle Ages. Historical Research 5: 113–25. [Google Scholar]

| No | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Siena Cathedral (Duomo di Siena) Interior | She-wolf sculpture: the oldest existing she-wolf sculpture in Siena, initially preserved in the museum. |

| 2 | Siena City Hall (Palazzo Pubblico) | Gilded bronze she-wolf sculpture: created by Giovanni di Turino around 1430. |

| 3 | Siena Cathedral Square | She-wolf sculpture in black-and-white marble: made in 1373 and restored in the 19th century. (Figure 1) |

| 4 | Terzo di San Maurizio | She-wolf: located near the ancient Porta San Maurizio. |

| 5 | Terzo di Camollia | She-wolf: situated in the centre of Piazza Tolomei. |

| 6 | Terzo di Città | She-wolf: located at Quattro Cantoni (“Four Corners”), a central crossroads. |

| 7 | Fonte Gaia | A significant city emblem: a fountain flanked by a she-wolf on each side. |

| 8 | Porta Camollia | A she-wolf sculpture stands at the entrance to Porta Romana, one of Siena’s southern gates. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yin, M. Fact, Fiction, and Legend: Writing Urban History and Identity in Medieval and Renaissance Siena. Religions 2025, 16, 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030337

Yin M. Fact, Fiction, and Legend: Writing Urban History and Identity in Medieval and Renaissance Siena. Religions. 2025; 16(3):337. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030337

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Ming. 2025. "Fact, Fiction, and Legend: Writing Urban History and Identity in Medieval and Renaissance Siena" Religions 16, no. 3: 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030337

APA StyleYin, M. (2025). Fact, Fiction, and Legend: Writing Urban History and Identity in Medieval and Renaissance Siena. Religions, 16(3), 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030337