1. Introduction

Among the main changes in the global status of Christianity over recent decades, the significant growth in the proportion of Evangelicals is noteworthy. In terms of global statistics, the population of Evangelicals more than tripled between 1970 and 2020, rising from 112 to 386 million, 77% of whom live in the southern hemisphere (

Johnson and Zurlo 2020). This notable growth in Evangelical presence is clearly seen in the results of the population censuses in Brazil, a country with over 212.6 million inhabitants (

Brasil 2024). These censuses recorded an index of 15.4% Evangelicals in 2000, rising to 22.2% in 2010, and attaining 31.0% by 2020 (

Negri et al. 2023). As pointed out by

Negri et al. (

2023), studies show that this increase has been more pronounced in urban areas and is related to the migration of people to the cities where there is a larger supply of churches and religious events. On analysing factors related to this dramatic growth, besides the mass migration and the accelerated urbanization, the authors also point to other factors, which include largescale social and economic transformations in the country over recent decades, the high indices of poverty and economic inequality, the role of the media and technology in disseminating religious messages and recruiting new members, as well as the close relationship of Evangelicals with the political class in Brazil, resulting in the election of several Evangelical leaders to positions in the legislative and executive branches, which, in turn, has an impact on public policy, perceptions and social values.

Although it cannot be said that Evangelicals are a homogeneous religious group, certain more conservative characteristics are generally associated with them (

Johnson and Zurlo 2020), such as their stances on sexuality, gender diversity, the role of women, abortion rights, and the resources and treatments employed in physical/mental healthcare, e.g., blood transfusions, organ donation, the use of psychiatric medication, among others. These postures frequently enter into conflict with present-day guidelines in psychology, as a science and a profession, particularly in Brazil where the representative legal bodies, the Federal Council of Psychology (CFP) and the respective regional councils (CRPs), have defended more liberal causes that are in line with the principles of human rights. From this contentious scenario a number of symptoms have emerged: (a) many Evangelicals are deliberately shunning psychology, seeing in its professionals a real threat to their values of religious identity; (b) some students of psychology, coming from families that were Evangelical in origin, end up exercising a kind of “extirpation” of their beliefs as if seeking to safeguard their future professional competence; (c) diverse Evangelicals, who are also psychologists, frequently seek to instil their own values into psychology, whether by creating Christian psychological associations (CPPC), formulating specific therapeutical techniques (e.g., for the reversion of homosexuality) or offering psychology training courses or therapeutic community services where they can combine religious principles with specific psychological approaches (e.g., psychoanalysis); (d) for their part, CFP and CRP members have gone as far as to issue directives and documents seeking to “protect” psychology from possible “contamination” or religious adjectivization; (e) psychology colleagues have been known to make complaints about each other to the regional CRPs with the aim of safeguarding the principle of secularism in accordance with the country’s constitution, where they believe that religious values are being inculcated into or are “contaminating” the professionals’ work environment; (f) and, finally, many professionals and students continue to be conflicted in the exercise of their profession and often choose to keep quiet about the matter in clinical or hospital environments as a way to protect themselves from potential criticism and threats, both internally and externally.

Despite the fact that it is not just about Evangelicals, the symptoms referred to above, among many others, have been identified by diverse researchers in the Brazilian setting (

Ancona-Lopez 2018;

Lionço 2017;

Freitas 2020;

Egg-Serra and Holanda 2022;

Pereira and Holanda 2016,

2019), when investigating the impact of religiosity on training or working in the area of psychology. Given the importance of this subject, and the need to better understand the specifics, as well as the respective ethical and practical implications, especially in the work of psychologists in hospital and mental health contexts, this article describes the results of an extract from a larger, qualitative study

1 developed in Brazil’s capital city, Brasília, aimed at answering the following questions: (a) How does Evangelical religiosity make its presence felt in clinical practice, according to psychologists working in these settings?; (b) how do these psychologists perceive the role of Evangelical religiosity in the physical and mental health of their patients (and/or their family members) based on experience of working in these settings?; (c) how do they deal with it in their professional practice?

1.1. Evangelicals and Protestants—Connections, Distinctions and Modes of Subjectivation

It is common in today’s society, and particularly in Brazil, for the term “Evangelical” to be used by laypeople, and even by scholars, to refer to all Christians who profess to be non-Catholic or non-Spiritist. However, there are distinctions, both in the conceptualization of the terms and also in the origins and characteristics of the groups to which they refer. Historically, the origins of Evangelicalism date back to the first half of 18th century Europe, when the English-language Protestantism was renewed and religiously revived by prominent evangelists like George Whitefield and John Wesley, though also upheld by common men and women (

Johnson and Zurlo 2020). However, if, in the course of history, the term “Evangelical” became associated more with Anglican dissidents, and with Lutherans and Presbyterians, nowadays it tends to be associated far more with the Pentecostal and Neo-Pentecostal movements. Thus, the classic Pentecostal denominations, such as the Assemblies of God, are, for the most part, Evangelical, and up to a third of Evangelicals are Pentecostals.

As for Protestantism, this is a Christian movement composed of one of the four worldwide divisions of the Christian Church across the world, alongside the Roman Catholic Church, Orthodox Church and Anglican Church (

Mendonça 2012). The movement arose with the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century, led by the German Augustinian monk, Martin Luther, who challenged the doctrines of the Catholic Church, such as the authority of the Pope and his role as mediator between man and God, the selling of indulgences and the veneration of saints. Questioning the possibilities of reform in the doctrinal fundamentals of the Catholic church, the movement inaugurated a new Christian faith based on the teaching of the Gospels. As a result, the term ”Evangelical” started to be used to designate the Christian followers of this “new faith”, Lutherans and Presbyterians, at that time. However, based on the Diet of Speyer, in 1529, and the protests arising therefrom, those who accepted the faith proposed by Luther and other reformers, in disagreement with what was being taught by the Catholic Church, called themselves “Protestants”, which is the case to the present day and which, according to the Brazilian theologist and historian,

Martin Norberto Dreher (

2014), meant that the use of the term “Evangelical” to represent them was thereby abolished.

According to this author (

Dreher 2014), the concept “Evangelical” possesses at least two lines, one having its origins in the Reformation in Germany, and the other in England. The one originating in Germany is a normative concept, the intention of which is to characterize the doctrine according to the Gospels; for this reason, Luther accepted this designation until he realized that it might have connotations with political parties. Although he knew that the term “evangelical” could very well distinguish between followers of the Protestant Reformation and Christian Catholics, he decided against using the expression when he realized the possible political and social connotations, which would depart from the theological and spiritual proposition of the Protestant movement. Meanwhile, in the English root, the concept “Evangelical” did indeed possess this interpretation (

Dreher 2014). In 16th century England, unlike in Germany, there was no religious reformation. While Anglicanism was the official religion, a group of reformed Christians challenged this faith, accusing the Anglicans of not living up to the teachings of the Gospels. These dissenters pioneered a new movement known as “puritanism” and started identifying themselves as “Evangelicals” to set themselves apart.

In the other line, to explain the origin of the term “Evangelical”,

Cairns (

2008) characterizes Protestants and Evangelicals as distinct groups of Christians deriving from the Reformation. Opposed to the theological liberalism which emerged in the seminaries and universities in Germany and England, spreading to North America between 1865 and 1880, the movement called “Evangelicalism” emerged. Calling themselves “Evangelicals”, to distinguish them from liberal Christians, and also known as “fundamentalists” or “separatists”, they disagreed with the liberal theology that was spreading through the bosom of the Protestant church, considering it to be opposed to the orthodoxy of the Protestant Reformation. Many of these separatists ended up founding new denominations that spread to other countries and which, currently, represent a vast religious, organizational, ecclesiological and theological diversity in Protestantism all over the world. According to

Johnson and Zurlo (

2020), at the present time, across the planet, Protestantism is composed of many different churches, the main ones being: Pentecostal, Anglican, Reformed Lutheran, Baptists, United (a union of bodies from different traditions), Reformed/Presbyterian, Adventist, Methodist, Nondenominational, Holiness, Congregational, Brethren, Disciples, Mennonite, Salvationist, Friends (Quaker) and Moravian.

In Brazil, since the beginnings of the presence of Protestantism in the 19th century, the Protestants expressed a preference for the term “Evangelical”. Examples of said preference are illustrated in the name “Imprensa Evangélica” (Evangelical Press), the first Protestant journal published in Brazil, printed between 1864 and 1892, and also the Evangelical Confederation of Brazil, founded in 1934, though it ceased to operate in the early 1960s. Thus, the concept “Evangelical” took on a distinctive character in order to differentiate itself from Christians arising, either directly or indirectly, from the Protestant Reformation of the Catholic and Spiritist Christians (

Cairns 2008). However, with the emergence of Pentecostalism at the beginning of the 20th century, and the variety of denominations and sects that surfaced within the sphere of Protestantism, culminating in the Neo-Pentecostalism that emerged in the middle of the 20th century, the historical Protestant churches started to identify themselves more with the term Protestant than the term Evangelical in order to differentiate themselves from the new emerging tides. Accordingly, given the denominational differences, Protestantism should not be regarded as an undifferentiated whole, despite the fact that the faith professed by its followers remains unchanged, at least in its theological and doctrinal fundamentals (

Dunstan 1980). This distinction, however, has not been assimilated by those who do not belong to said denominations, such that, in general, Brazilians tend to employ the term “Evangelical” to refer to both followers of Evangelicalism and followers of Protestantism.

From a psychological point of view, it is important to stress that the doctrinal fundamentals of Protestant Christianity are very different from the fundamentals of Catholic Christianity, resulting in a differentiation in the mode of subjectivation between the religiosities. While Catholics tends to practice their faith mediated by a priest, as well as obedience to the sacraments, veneration of the saints as mediators of man before God, and the practice of charity or other works to secure their entry to heaven, Protestants cherish their direct relationship with God, the free interpretation of the Bible and living their faith based on the Five Solae of the Protestant Reformation. Thus, Protestant/Evangelical religiosity stresses that the Bible is the sole rule of faith and practice for the believer, becoming a handbook of Christian life (Sola Scriptura), and they understand that salvation does not happen through the merits of man but through the grace of God, or, in other words, for having given man unmerited favour, through the vicarious sacrifice of Jesus (Sola Gratia), who becomes the only “personal savior and mediator between God and man” (Solus Christus). Therefore, they believe that only through the path of faith does man attain forgiveness for his sins and his justification, not depending therefore on his works (Sola Fide), which explains the grandness that God occupies in the life and the religiosity of the Protestant Christian (Soli Deo Gloria). Protestant Christians of non-historic churches, who identify with the term “Evangelical”, as is the case with Pentecostal and Neo-Pentecostal Christians, also live these rules of faith and practice in their religious experiences, however, they also seek the involvement of the Holy Spirit and the divine cure in their lives.

1.2. Evangelical Religiosity and Physical/Mental Health: The Meeting of Culture and Clinic

To comment on the relationship between religiosity and mental health requires, as a minimum, and as neatly observed by

Aletti (

2012b), a combination of a view of the cultural psychology of religion and that of clinical psychology, bearing in mind, however, that the latter is not only restricted to psychotherapeutic practice. This is because this area is also exercised in other settings, such as hospitals and communities. This epistemological challenge reminds us of the maxim of Antoine Vergote: “every human act is psychological in nature, but nothing is purely and only psychological” (

Vergote 1999, p. 95). This understanding is essential for the avoidance of reductionism and to enable a critical interpretation of the vast literature that has been produced, from the origins of psychology (and the psychology of religion in particular!) to the present day, in respect of the role of religiosity in physical/mental wellbeing or malaise. After all, this role has been described as both problematical and empowering and, as can be seen in an article with a suggestive title by

Abu-Raiya et al. (

2016), it can also be exercised as a veritable “buffer” in the links between religious/spiritual struggles and wellbeing/mental health. If this is true for studies that focus on the role of religiosity in general, it is no less true for those that deal specifically with Evangelical religiosity.

In fact, the perspective of a cultural psychology of religion may even help us to understand its production and its variations with regard to the clinical impacts of religiosity, especially in a comparison of the trajectories of European academic and scientific production with American production in this area (

Paiva 1990). Although the production emanating from both continents has contributed in recent years to a more positive vision in terms of the impact of Christian religiosity on mental health, taking into consideration their holistic responses to physical/psychic suffering (

Lloyd 2024), the contribution of American Protestant and/or Evangelical authors in this direction is renowned, from the pioneer

William James (

[1902] 2002) through to prominent contemporary figures like

Kenneth Pargament (

1997) and

Harold Koenig (

2018). Indeed, these last two authors present their theoretical–conceptual perspectives based on an acerbic critique of the psychoanalytical concept of the defence mechanism when applied to religiosity. Despite this, however, as observed by

Lloyd (

2024), there has also been, in recent years, a growing controversy surrounding the responses of Evangelical churches or communities to mental health. According to this British author, “adopting often literalist interpretations of scripture, these church communities may conflate mental illness exclusively with sin, demons, or diminished faith, thereby inadvertently promoting shaming and voluntaristic notions of psychological suffering” (

Lloyd 2024, p. 110).

Underpinned by an interpretative, comprehensive perspective,

Lloyd (

2021) starts from the principle that beliefs—so common amongst Evangelicals—that mental suffering may be caused by demons, sin or generational curses, may have both positive or negative effects for individuals and groups. The author states that the phenomenological descriptions of these experiences, and the subjective meanings associated with them, remain somewhat neglected in the literature. Thus, employing semi-structured interviews in an idiographic attempt to explore the experiences of the mental distress of Evangelical Christians in relation to their faith, in the context of Great Britain, we come to the production of two superordinated topics: (a) a kind of negative spiritualization, when their mental suffering was rejected and demonized, making them feel ashamed and stigmatized, but at the same time motivating the quest for otherness: (b) the negotiation of a nuanced personal synthesis of faith, theology and distress, which included the adoption of etiological accounts which contextualized personal distress in terms of their lives and relationships as a whole.

The subject is of extreme importance to clinical psychology, whether practised in hospital settings in general or in specific mental health services. After all, the tendency towards perhaps excessive secularization of the so-called psychological “illnesses” has ended up leading to a disregard for the potential of faith in terms of physical/mental health. In this process, religions that are characterized as “fundamentalist”—as Evangelicals are often painted—tend to be even more stigmatized, running the risk of being annulled in their possibly propulsive role as providers of hope, direction, meaning or tangible strategies for coping with physical or mental suffering. Hence the importance of studying the perceptions of clinical psychologists in respect of Evangelic religiosity in their work environments.

1.3. Spirituality, Religiosity and Religion: A Phenomenological Interpretation

From a phenomenological point of view, the coming together of the cultural psychology of religion and clinical psychology requires an understanding of the notions of spirituality, religiosity and religion that goes beyond polarization and dichotomies. After all, the mere counterposition between institutional and personal religiosity does not take into account the psychological fact that spirituality is lived by a subject inserted in a culture and a social organization (

Aletti 2012a). On the other hand, religious institutions in general, including Evangelical ones, advocate a spiritual adherence from their followers which, in turn, implies experiencing emotions and developing specific attitudes and behaviours.

Inspired by the reflexions described above, as well as others described by

Aletti (

2012a,

2012b),

Freitas (

2025) has developed a conceptual model, founded on Husserlian phenomenology, that is capable of engaging with authors in comprehensive sociology and with clinical psychology and religion and, at the same time, establishing connections with and distinctions between the three terms—spirituality, religiosity and religion—in a more organic way, avoiding the reproduction of polarization and dichotomies, such as those that believe that spirituality is healthy while religion can be detrimental to mental health.

The aforementioned model, illustrated in

Figure 1, aims to retrieve and qualify the etymological meaning of the term spiritus, referring to pneuma, “the breath of life”, and therefore associate it with the very movement of the conscious towards the world. As happens with the phenomenological rotation of the look (

Husserl [1927] 1990), this movement seeks to explore the world and endow it with meaning. At the same time that this flux comes from the individual and his/her own life, and their personal actions, it is essentially a reference to “living in community, as I and we, within a communal horizon […], such as family, nation and supernation”. After all, the father of phenomenology even reiterated that the word “life” transcends its physiological meaning, taken to be “creator of culture, in its broadest meaning, in a historical unit” and teleological. Thus, spirituality is situated at the heart of the big questions about life, about existence, which acquire much more emphasis at times of great human crises. At the bedrock of these questions are those generally formulated by the common man, but also by philosophers and scientists: “where do we come from?”; “where are we and what are we doing here?”; and “where are we going?”

However, spirituality does not just encase itself in questions or in impulsion and in the search for meaning, but rather it seeks to realize itself in the meeting of answers that realize it. Accordingly, the belief in a dimension that is transcendent, sacred, creative, infinite, final or beyond human, has constituted itself in one of the forms (though not the only one!) of response that accompany humanity, historically and geographically, in all known cultures. The concept of religiosity has been attributed to this subjective experience of finding responses in this transcendent dimension, as illustrated in

Figure 1. In this figure, a notion of religion can be glimpsed that is characterized by the sharing of specific forms of religiosity—such as Evangelical Christians, for example—while collective organizations espouse shared beliefs, values, myths and rites—in the form of dogma and institutionalized doctrine within a communal horizon—in a communal setting, in society and in culture, and which can either embrace or confront science, politics, economy, ideology, and even psychology. This communal horizon, in turn, makes up the context in which people are inserted, in which they develop and interact such that, throughout their existence, and by means of intersubjectivity, the experiences of others are seen to be available and, by way of identifications and mutual consent, are also assimilated, providing foundations for the answers to the demands for meaning that sprout from spirituality.

This conceptual model will orientate the discussion of the results obtained in the qualitative study described below, while also respecting and reflecting critically on the conceptual notions supplied by the clinical psychologists interviewed, by sharing their perceptions and experiences with Evangelical patients/users in their professional practice.

2. Materials and Methods

This qualitative, phenomenological study originated from excerpts from three separate, larger studies,

2 from which a database was developed in the Laboratory of Religion, Mental Health and Culture (

RESMCULT), coordinated by the second-named author of this paper. The database consists of semi-structured interviews with professionals in the areas of physical and mental health, addressing the following topics (core themes): (a) demographic data; (b) work environment; (c) ways in which the religiosity of the users/patients manifests itself in the aforementioned settings; (d) perceptions regarding these manifestations and their relationship with (physical or mental) health; (e) managing religiosity and its manifestations in the work environment, and what they consider good or bad practices to deal with them; (f) connections/distinctions between religious/spiritual experience and psychopathology; (g) experience of their own R/E; (h) whether or not the topic was addressed during training; and (i) how skillsets were developed for the management of religiosity in the work environment.

The aforementioned interviews were conducted by psychologists with prior training in the phenomenological approach. Each core theme was introduced based on trigger questions that served as facilitators for a spontaneous dialogue between interviewer and participant, allowing the responses to come naturally such that the lived experience would constitute a spontaneous recollection (

Amatuzzi 2011), or to put it another way, their shared, (re)lived and (re)signified experiences in the moment of the interview. With the due consent of each interviewee and interviewer, all the interviews were recorded, transcribed and subsequently revised, prior to upload to the

RESMCULT database.

For the purposes of the excerpt described herein, a total of fifteen interviews were selected from the databases referred to above, carried out with psychologists who practised in the Federal District of Brasília, of whom eight worked in hospital settings and seven in the area of mental health, more specifically in Psychosocial Care Centres (

CAPS3). The selection was based on the following criteria: (a) having been rigorously carried out in accordance with the phenomenological approach; (b) having considered all the previously listed thematic axes; and (c) having contained, throughout the course of the interview, frequent and significant references to either the Protestant or Evangelical religion in order to furnish elements for analysis in accord with the intended scope of the study.

Based on repeated readings regarding the fifteen selected interviews, contextualized snippets were obtained from the interviewees’ spontaneous remarks where they referred, either directly or indirectly, to the Evangelical religion or to adherent patients/family members, as per the interviewee’s understanding. This material, consisting of 82 passages (41 for each work environment mentioned), constituted the corpus-based discourse upon which the descriptive, phenomenological analysis was performed, inspired by

Amedeo Giorgi (

2011,

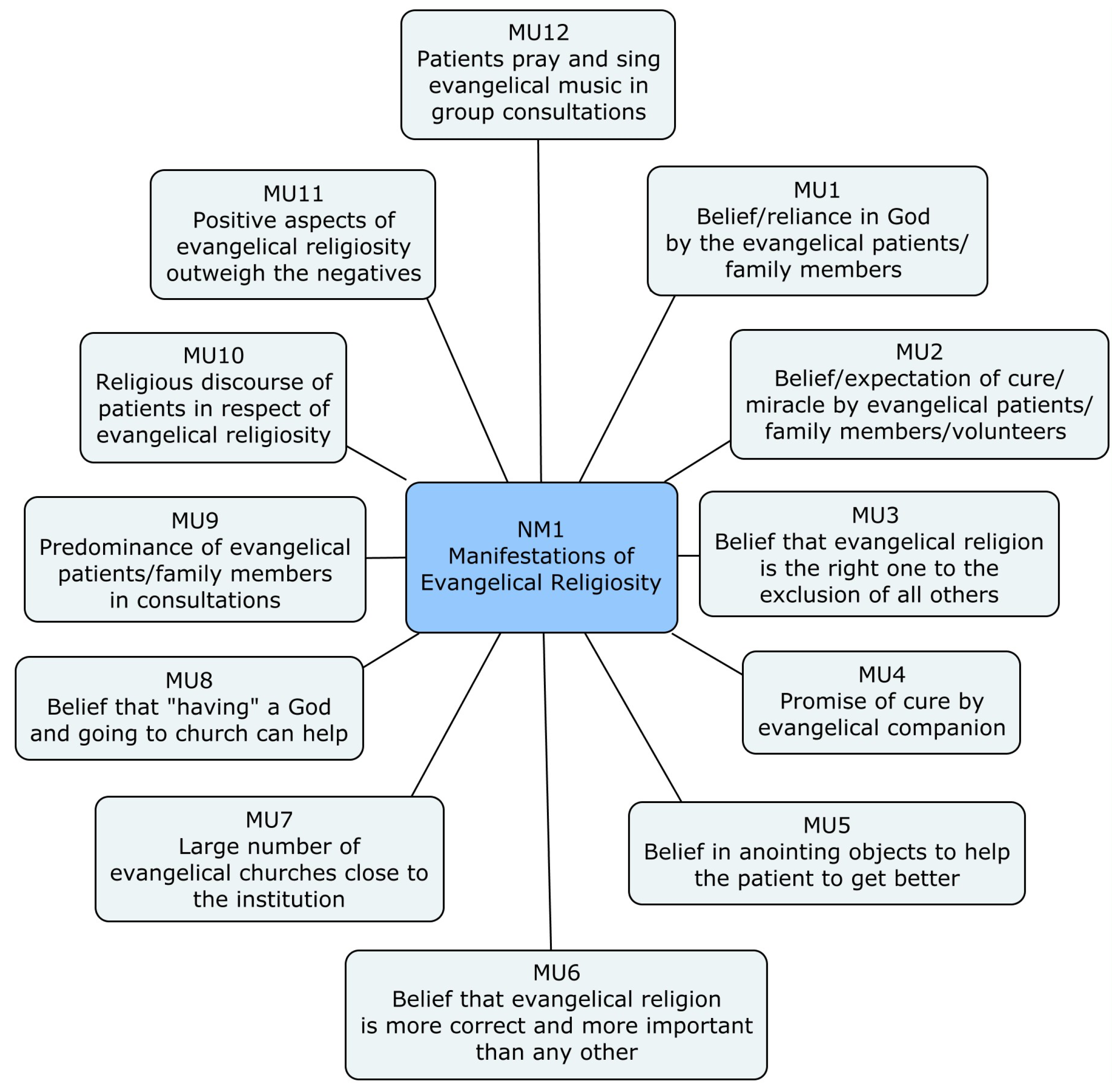

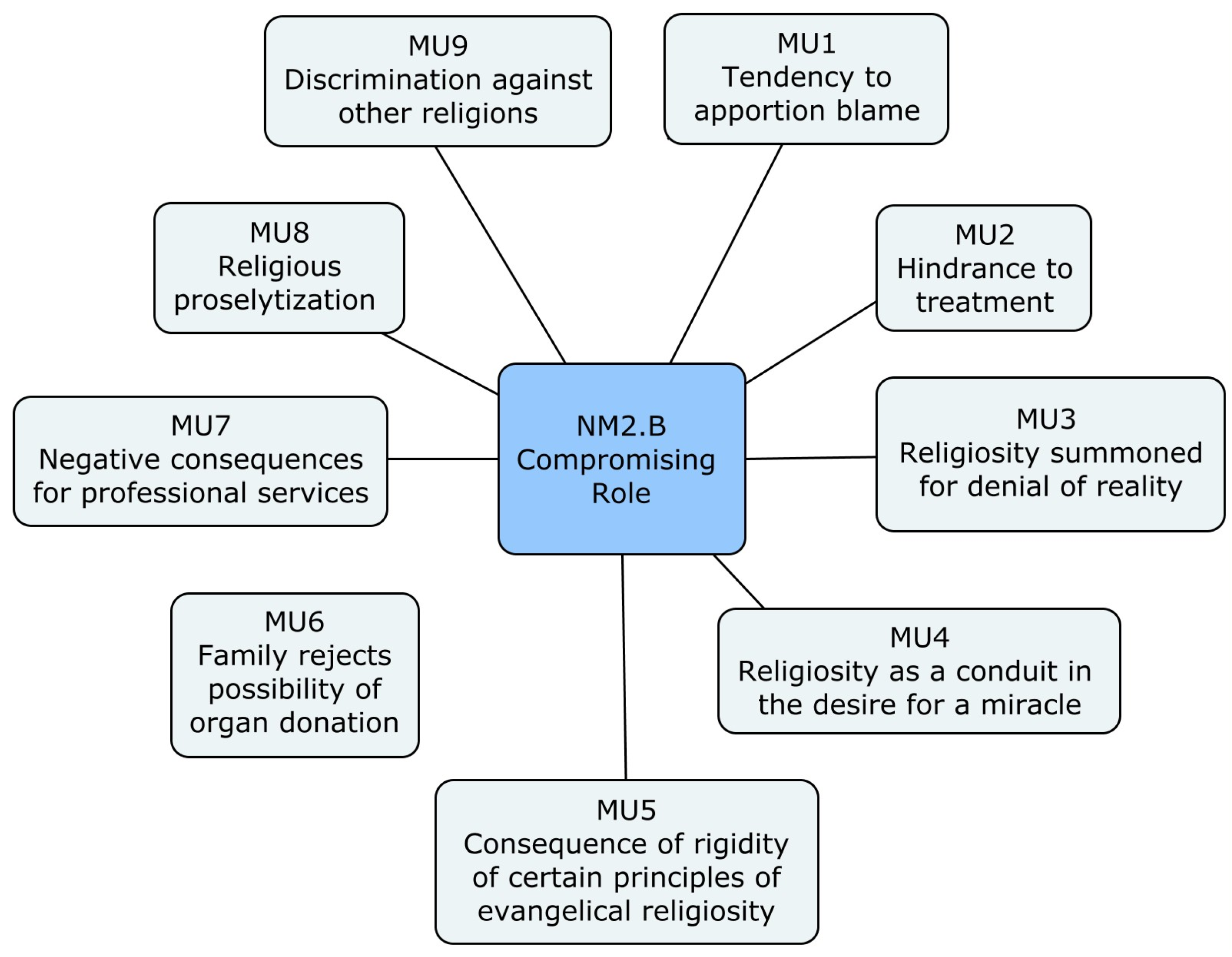

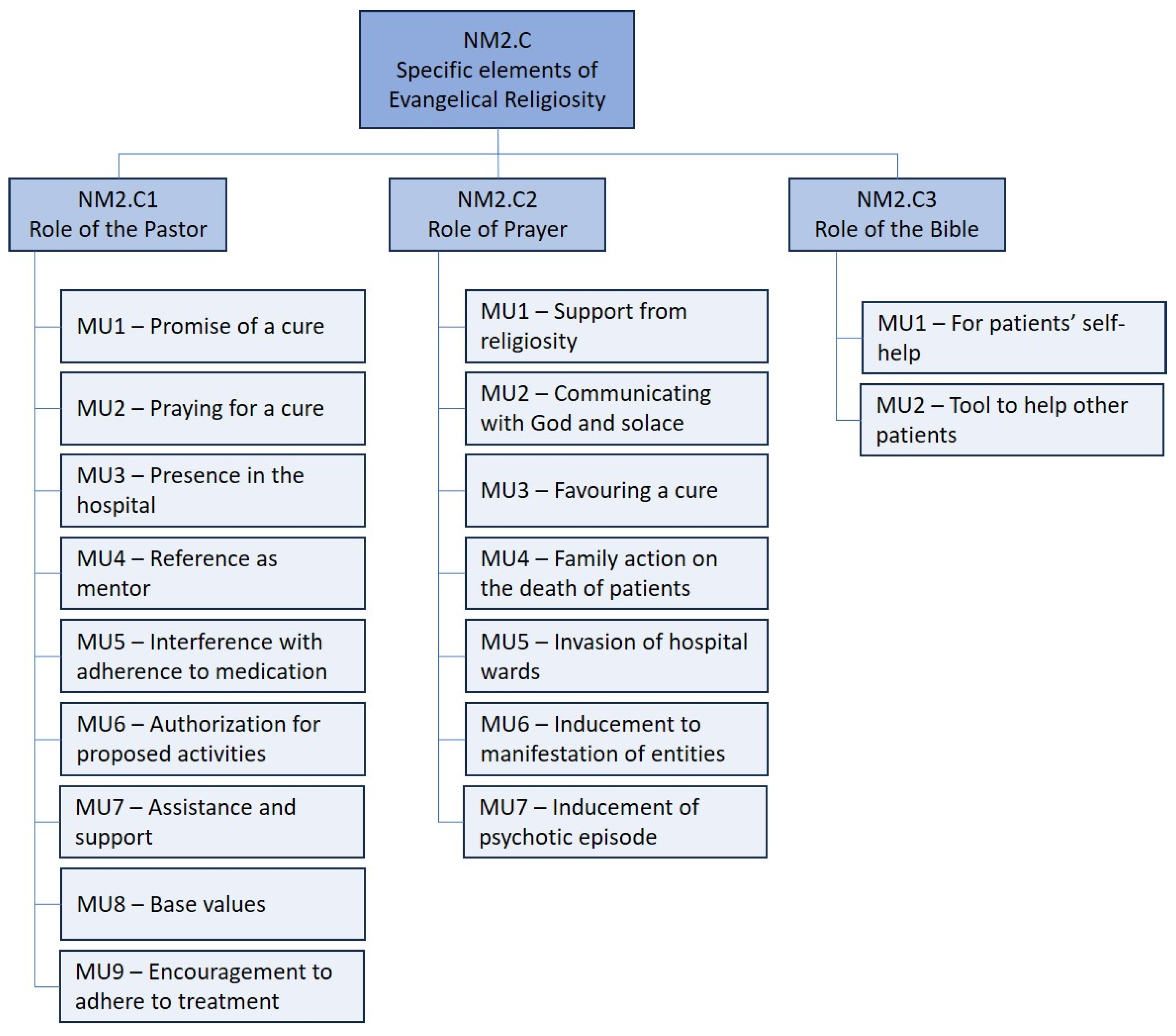

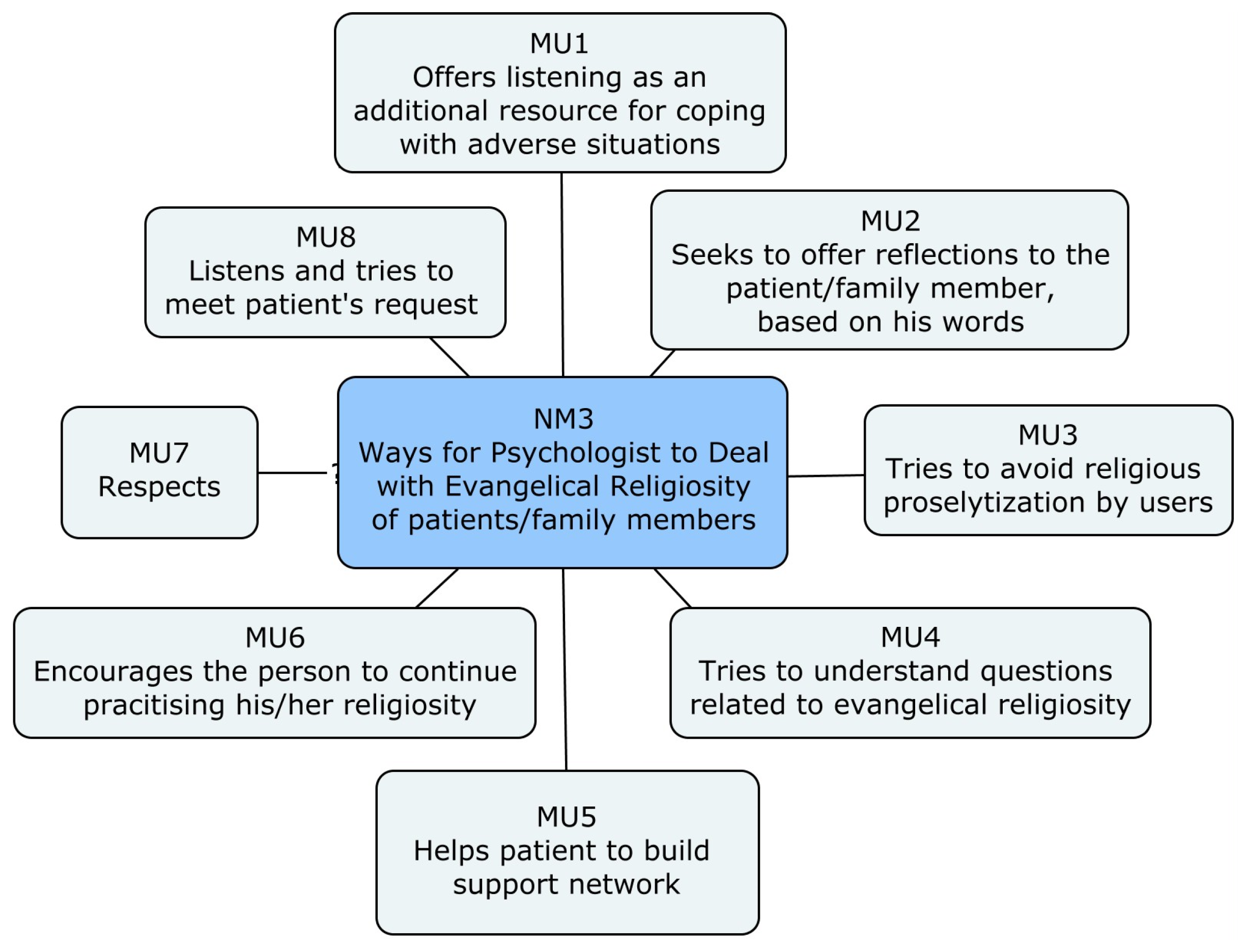

2012) and unfolding in four stages: 1. Apprehension of the meaning of everything, 2. identification of meaning units, 3. transformation of the expression of the natural attitude of the participant in psychologically and phenomenologically sensitive expressions, and 4. obtaining the overall structure of the experience. This process consisted of performing a detailed reading of the selected verbal corpus, that is to say, of the 82 extracts of significant phrases in the interviews, to identify the meaning units emerging therefrom, as well as the respective modes they were appropriated, and, subsequently, string together these units around nuclei of meaning. This nucleation system, in turn, enables the production of flow diagrams which, in combination, permit a glimpse of the overall structure of the lived experience, or, in other words, the experience of the interviewed psychologists when dealing with evangelical religiosity and its manifestations in hospital and mental health settings.

For the purpose of this article, the description of the results focused on three large nuclei of meaning: the way in which the interviewees experience and describe the manifestation of evangelical religiosity in their working environment; the way they perceive and describe their roles or the impact on mental health; and the way they claim they deal with it (management) in their hospital routines or in the mental health services.

4. Discussion

The first aspect that merits discussion with regard to the description of the results, above, is the fact that, though there was no question focusing specifically on Evangelical religiosity in the semi-structured interview script employed in this study, many direct and indirect references emerged in the spontaneous spoken words of the clinical psychologists with regard to this specific religiosity. In other words, by sharing their experiences and perceptions of religiosity in their respective work environments, and by describing the way it manifests itself and is perceived in its relationship to health, as well as the way they manage it, the care provided by clinical psychologists working in hospitals or in mental health services focuses significantly on this specific form of religiosity, underlining how much it mobilizes them. This merits discussion from at least two perspectives. On the one hand, this great mobilization seems to reflect questions linked to the subjective/social elaboration/representation affecting the specific context of contemporary Brazil. On the other hand, however, it also reflects the potential impacts, on the experiences and perceptions of clinical psychologists, of a broader reality linked to the specific characteristics of the Evangelical religion in today’s world and its respective status and psychosocial repercussions.

Considering the first of these perspectives, in terms of the reality of Brazil, it should be taken into consideration that, as observed in the last demographic censuses conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) (

IBGE 2012;

Brasil 2024), the proportional growth of Evangelicals in the country over the last 30 years is five times higher than the growth of the Brazilian population as a whole, namely 61.4% versus 12.3%. Moreover, at the same time that the number of churches, denominations and followers of the Evangelical religion is growing, as observed by

Mariano (

2013), so do the controversies and cases of discrimination, violence and religious intolerance involving Evangelicals (e.g., attacks on temples of the Afro-Brazilian religions), as transmitted by the various media outlets in the country. Indeed, in this regard, both the Brazilian media and the CFP have continually come out against any form of discrimination against specific religions, arguing for religious diversity (

Freitas and Piasson 2016). On the other hand, both the CFP and the Brazilian media are critically and publicly protesting against religious fundamentalism and against the Evangelical caucus in Brazil (

Lionço 2017), a country with a constitutional commitment to secularism. This debate simmers on a daily basis in the public arena while, in addition, there are the initiatives of certain Evangelical groups in the country who seek to create adjectivated training courses such as “Christian Psychology”, stirring intense debate, reaction and questioning within the professional rank and file and the respective representative bodies in Brazil. In some form, all of these questions certainly penetrate the subjectivity and experiences of clinical psychologists, particularly those who work in the public sector in the area of physical/mental health, contributing to the great mobilization surrounding Evangelical religiosity in the aforesaid contexts, not only those who are sympathetic to the cause or followers of the religion, but also those who are yet to adopt a posture or who have positioned themselves as clearly critical thereof.

With regard to the second perspective indicated above, relating to the specific characteristics of the Evangelical religion and its repercussions for physical and mental health and, consequently, for those who work in this area, one of the aspects that stands out most is the direct relationship with God. Through faith, this relationship is deemed to be sufficiently powerful to do anything, even things that seem impossible for man and medicine, such as miracles or cures for illnesses with a negative prognosis. The Protestant and Evangelical faiths are based on the Bible and its teachings, appearing in many biblical references in which the possibility of a cure from God, through faith, is mentioned (e.g., “I know that thou can do everything; no purpose of yours can be thwarted” Job 42.2.; “He sent his word, and healed them, and delivered them from their destructions”. Psalms 107.20.; “Heal the sick, cleanse the lepers, raise the dead, and cast out devils. Freely ye have received, freely give”. Matthew 10.)

4. Thus, it is very common for Evangelicals to believe in a cure and immerse themselves in this belief as one way to cope with falling sick and/or when facing imminent death by virtue of this sickness. Here one may seek to understand how this mode of Evangelical subjectivation, in relation to the belief in God and the divine cure, reverberates through the training, experiences and profession of psychologists and the extent to which it mobilizes them in relation to religiosity in their day-to-day clinical practice.

To put it another way, if, on the one hand, at certain moments, the posture of a faith that is so fundamental for Evangelicals can be experienced by the psychology clinic, as a propulsive force for their own work in their commitment to the promotion of health, then, on the other hand, it may also be regarded as something of a hindrance, particularly when it disempowers them as professionals, permeating their actions and orientations, and leaving them at the mercy of possible risks and harm that they would seek to avoid for the mental health of the users (and/or their families) of the services that they practise. This is evident from the results presented above. At certain moments and in certain situations, a psychologist perceives and describes Evangelical religiosity as something which really acts as a support to cope with the stressful situation of illness, hospitalization or death of the family member. At other times, however, it describes and accentuates the negative relationship between Evangelical religiosity and health, either because it interferes in a negative way with the treatment that the patient should be adhering to, or by promoting situations, conflicts or reactions/attitudes that can give rise to mental illness or that compromise the promotion of psychological wellbeing.

A third factor which certainly accentuates the intense mobilization of professionals with regard to religiosity in general, and Evangelic religiosity in particular, is the fact that the topic tends to be silenced, avoided or marginalized throughout their training (

Pereira and Holanda 2016,

2019) instead of being addressed with due propriety (

Freitas 2020;

Ancona-Lopez 2018;

Paiva 2020). In fact, in Brazil, it is possible for a psychology student to conclude his/her graduation course without ever having studied the topic, or sometimes even understanding that content of a religious and spiritual nature should not be accommodated and addressed within the context of psychological healthcare (

Pereira and Holanda 2016,

2019). This reality is in contradiction to the sociocultural reality of the country as, although constitutionally governed by the principle of secularism, it has a very religious population that is predominantly Christian and, as already mentioned, has witnessed a significant and striking growth in the Evangelical community in recent decades. Indeed, this ties in with the fact that some of the psychologists interviewed claimed that the majority of people they care for, in the two settings of professional activity, are Evangelical. This is also not consistent with the reality of a country which possesses an Evangelical caucus in its parliament, one which counts on the existence of an institution which brings together and welcomes Christian psychologists and psychiatrists and their religiosity and which discusses topics in areas of health that have, as a backdrop, religiosity and spirituality and their relationship with health in general, namely the Christian Psychologists and Psychiatrists Association (CPPC). It is also in contradiction with the reality that many students of psychology find themselves profoundly conflicted by the topic throughout their training (

Egg-Serra and Holanda 2022;

Pereira and Holanda 2016,

2019), with Evangelicals complaining that they are victims of bullying and religious discrimination within the academic context itself. Should we then be asking ourselves if, in addition to a certain stigma in relation to the topic of religiosity in the sphere of psychology training, the stigma relating to Evangelical religiosity is even greater and more serious? In other words, though numerous studies and approaches in contemporary psychology may be attempting to overcome the division it once implanted, between science and religion (

Carrette 2013), the topic of religiosity does not appear to merit due attention in the formal training of professionals so as to deal with it in a clinical context. This silencing and even marginalization surrounding the topic certainly accentuates the mobilization, the doubts, the conflicts and the insecurities in dealing with the topic in a variety of settings, including hospitals and mental healthcare services.

Another aspect attracting our attention in the results is the tendency for the interviewees to employ both direct, explicit references to Evangelical religiosity and also, in similar proportions, indirect remarks that identify the modes of expression of this religiosity in clinical contexts. This may also be a reflection of the paradox exposited previously, as the indirect remarks allow us to glimpse, simultaneously, a certain discomfort with Evangelical religiosity and its manifestations, but also a certain care not to be seen as prejudiced or disrespectful to it. Curiously, the difference in the frequency of these indirect remarks between those who work in mental health settings (CAPS) and those who work in hospital settings is extremely significant: in the former, they appear four times more often than the direct references, while in the latter they are proportionately similar.

In fact, in hospital settings, the focus is geared more to physical health and hence the clearer tendency to accentuate the aspects of support, assistance and hope offered by Evangelic religiosity, which appear to favour direct references to religiosity. Moreover, psychologists are called to intervene in situations where religiosity interferes directly with the treatment, and in a medical context, where the language also tends to be more direct, they stimulate direct references, though these direct references appear in the same proportion as the indirect references. As far as the mental health services context (CAPS) is concerned, the predominance of indirect remarks shows that the discomfort and care are even greater, as if they were “treading on eggs”, when talking about the topic. This is where the subjective and intersubjective conflicts of the clinical psychologists, with respect to religiosity, seem more evident, even as they simultaneously allow a glimpse of some of the elements observed by

Lloyd (

2021,

2024). These elements describe the controversy surrounding the responses provided by Evangelical churches or communities when referring to the problems of mental health and their impact on Evangelical followers and on the professionals who monitor them. This is where the terms used in the indirect remarks, such as “Bible”, “Pastor”, “Prayer”, “Church”, “Salvation”, “Sin”, etc., take centre stage. These terms relate to some of the following controversies mentioned by the author: literal interpretation of the scriptures; non-orthodox attitudes and behaviour—and which reflect or produce psychic suffering—interpreted as sins or the interference of the devil; fundamentalist values in terms of sexuality and gender issues; and postures that are opposed to psychiatric treatment, among others.

Thus, this very significant predominance of indirect remarks from the professionals working in mental healthcare allows a glimpse of the crisscrossing between criticism of the abovementioned postures and the respective controversies—which have been so pronounced throughout the training of professionals and in the orientation of the councils which regulate the profession in the country—but also of a certain caution or reluctance not to explicitly condemn one of the forms of religiosity that has been growing most quickly in the country in recent decades. The nature of these crosscurrents is even more evident when considering the fact that so many professionals have shown themselves to be so mobilized during the interviews—in particular the Evangelicals or ex-Evangelicals—to the point that they would burst into fits of tears; or claim to be talking for the first time about the issue without the impression that they were being judged; or even only opening up about their conflicts regarding the subject after the recorder has been switched off.

Despite this intense mobilization, it may also be said, curiously, that the way in which the overall structure of the experience of the professionals, and even non-Evangelicals, is organized demonstrates something similar to that which was observed by

Lloyd (

2021,

2024) when conducting qualitative studies with Evangelicals in a British setting:

- (a)

On the one hand, if there is a tendency toward negativizing Evangelical spirituality, there is also, by the same token, a movement to avoid judging patients that makes them feel discriminated against or stigmatized. In addition, healthcare professionals look to recognize, as can be seen in the flow diagrams represented earlier in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, not just the negative or compromising role of Evangelical religiosity in physical/mental health, but also its positive and propulsive aspect;

- (b)

On the other hand, this kind of negotiation and personal synthesis that they aim to realize, between the scepticism of psychology, the faith that moves Brazilians and psychic suffering (primarily of users they attend to in their respective clinical, hospital or CAPS settings), includes an etiological perspective that contextualizes personal suffering in terms of the personal lives of their patients and the relationships with the whole, including therein not only aspects that can compromise mental health (e.g., rigidity, denial of reality, excessive blaming, proselytism, etc.), but also the propulsive aspects (e.g., resilience, support, hope, sense and meaning, etc.).

Note, therefore, that the overall structure of what is experienced by the professionals that the clinical psychologists interviewed shows a movement to seek to balance what is propulsive in the modes of personal elaboration of Evangelical religiosity, seizing on the what and the how that it satisfies a thirst/demand for existential meaning when faced with physical or mental distress, and with that which it may be carrying that is compromising—especially as a system of a shared doctrine of dogma which can take away from the subject (users or family members) their own autonomy to conduct their personal lives and relationships, with themselves and with others. This is very evident from a close look at

Figure 4, which exhibits the configuration of the overall structure of what is lived insofar as it refers to the ways by which to deal with the Evangelical religiosity of patients/family members. At the same time that they seek to balance these two aspects and their complex intricacies and controversies, it can be seen that they lack words or terms to express more clearly the relationships they are learning, almost intuitively (as a formal study of the topic was lacking during their training) between spirituality (as a demand for meaning), religiosity (as modes of subjective elaboration rooted in the belief of the transcendent) and religion (a shared system which includes dogma and doctrinal orientation). This is clear, for example, in the extracts of the verbal remarks that illustrate their ways to manage situations: at the same time that they seek to encourage the expression of meaning borne by the directions given to spirituality, manifested by their patients, they seek a way to limit the impact of religion as dogma, stimulating a reflexivity capable of assuring greater autonomy, flexibility, criticality and liberty in their judgments and evaluations involving their own process of suffering and their destinies.

5. Conclusions

Throughout this article, the aim was to respond to questions still poorly explored in the literature with respect to the way that Evangelical religiosity presents itself to clinical psychologists working in hospital settings and in the area of mental health services. These questions include those asking about how these clinical psychologists perceive their potential compromising or propulsive role in mental health, and also about how they would describe the ways they deal with Evangelical religiosity in the day-to-day routines of their professional practice. The responses encountered in the extract of the study described herein show the controversy, in the area of physical/mental healthcare, which accompanies the implications of this specific mode of cultivating the Christian religion and, in this specific case, how they are viewed by clinical psychologists in Brazil. These controversies, though heavily explored in the media and in some psychology of religion papers, have not been adequately problematized and studied over the course of the psychologists’ training in a way that would really qualify them to work or express themselves on the subject with greater assuredness. However, it was clear that they made an effort to manage the subject in an ethical and responsible fashion, despite their own conflicts and difficulties.

The methodology employed was found to be largely adequate for addressing the proposed themes, albeit with a number of interviews that was still too small to be able to make generalizations about other cultural contexts. Even so, what was observed in the study may be situated in dialogue with other studies involving not only clinical psychologists but also followers of Evangelic religiosity who are seeking the services of psychologists, or who receive them in the health institutions in which they are being cared for. Cross-referencing the results of studies conducted with both populations would be very interesting in order to acquire a deeper understanding of the controversies referred to throughout this paper.

Lastly, but no less importantly, the paper has also shown itself to be propulsive in the sense of testing a theoretical model inspired by phenomenology. Such a model could be better developed based on this experience, promoting a better appropriation and understanding of the relationship between spirituality, religiosity and religion on the part of the psychology professionals working or intending to work in clinical settings. In these settings, especially in countries with such accentuated religiosity, as is evident in the case of the Brazilian population, they will certainly need to deal in their daily routines not only with Evangelical religiosity, but also other diverse ways to confront and realize existential meaning, where an intersection with the system of shared responses, in the community and in the culture, is inevitable.