Abstract

This article delves into two Iranian Sufi women’s approaches to the Qurʾān, gender, and visual culture: (1) Parvāneh Hadāvand, a Sufi leader in Tehran, uses visual means to enhance the spiritual–aesthetic–emotional experiences of her students. She challenges gender norms within male-dominated spaces by reinterpreting visual-material objects and asserting her authority as a woman Sufi guide. (2) Mītrā Asadī, a Sufi teacher in Shiraz, problematizes the overall visual culture of gender roles by arguing that, through the spiritual transformation of the human being’s genderless essence (Arabic rūḥ; Persian jān), categories of gender become ephemeral and irrelevant. These two case studies are examined in terms of how these Sufi women utilize aesthetic experience, visual aspects, and visual-material culture in their Sufi practices and teachings. Further, it is investigated how these practices shape Hadāvand’s and Asadī’s gender performativities.

1. Introduction

In this article, I explore the complex and multidimensional field of contemporary Sufism, the Qurʾān, gender, and visual culture. The practices and teachings of two Iranian Sufi women serve as the basis for inquiry. First, Parvāneh Hadāvand, the spiritual leader of a predominantly female Sufi group in Tehran, emphasizes exporting individual and communal spiritual experience into broader sociopolitical contexts. By challenging androcentric paradigms, she reframes visual symbols of Shiite religiosity and incorporates them into her Sufi teachings while asserting her presence in spaces traditionally reserved for men. The second case study examines Mītrā Asadī, a Sufi teacher in Shiraz, who relativizes the importance of outer appearances and visual cultures of gender roles. She views gender as a reflection of an inferior spiritual state that can be transcended through the harmonization of the self with its genderless essence or “soul” (Arabic rūḥ; Persian jān1). Through these transformations, gender categories are perceived as temporary and irrelevant. This shift fosters inter-social behavior among Sufis, regardless of their gender or sex.

Both Hadāvand and Asadī derive their approaches to gender from their engagement with the Qurʾān and Sufism, realizing subversive forms of gender performativity in their discourses and social enactments. Regarding their spiritual interpretations, which inform their lived experiences and teaching methodologies, the two Iranian Sufi teachers Hadāvand and Asadī share a perspective on experiencing reality with other Sufis. Such modes of Sufi phenomenology are based on the epistemic approach that there is an inseparable relationship between subjective experience, perceived nature, the Qurʾān, and the divine truth (ḥaqīqa). Consequently, the signs of inner knowledge are related to the signs of outer phenomena. Sufis like Hadāvand and Asadī believe that all these inner and outer signs point to God. Individual experience is understood as a translation of universal existence into the inner self. Through such internalization, Sufis seek to transcend the perceived distance from God. This process transforms the Sufi’s consciousness, which can then lead to new approaches to the social context at hand. Moreover, by translating the message of the Qurʾān into their inner experience, the two Iranian Sufi teachers claim to achieve gnostic and moral qualities that elevate them above society while maintaining their social responsibility. In this understanding, the acquisition of experiential knowledge (maʿrifa) is the culmination of human existence, and the performative experience and translation of the Qurʾān are the prerequisites for this knowledge. Through a lived, experiential translation of the Qurʾān and the respective Sufi teachings into the individual’s inner life, the interpretations then embodied become means of expanded cognition, allowing the Sufi to transcend and transform her or his “self”–the nafs as the holistic interplay of the body, the emotions, the intellect, and the mind, all culminating in the human’s essence or spirit (rūḥ or jān).2

2. Methodological Approach to Visual Culture and Aesthetic Experience

Visual culture and aesthetic experiences are central to Hadāvand’s and Asadī’s teachings and practices. W. J. T. Mitchell’s concept of the “social construction of visual experience” (Mitchell 1995, p. 540) informs this analysis, particularly in directing the focus on “visual practices, the ways of seeing and being seen” (Mitchell 1995, p. 542). Similarly, Margaret Dikovitskaya’s framework is applied to examine “the visual as a place for examining the social mechanisms of differentiation” (Dikovitskaya 2021, p. 196). I utilize both approaches to analyze the interplay between visual practices, gender performativity, and spiritual identity. Consequently, I reflect on how Hadāvand and Asadī “wish to be seen by others” and how they “use visual culture to articulate and promulgate their faith” (Harvey 2011b, p. 502). This visual culture responds to a social setting with which the two Sufis interact. Pamela Karimi’s insights on contemporary Iranian visual culture, steeped in ideological-emotional narratives, contextualize how Hadāvand and Asadī create alternative visual spaces within this landscape (Karimi 2022, pp. 19–23).

In analyzing Hadāvand’s and Asadī’s approaches to societal visuality, I further refer to Jan Scholz, Max Stille, and Ines Weinrich who argue for a fundamental link between aesthetic experience and social interaction, which is often framed by an “overall staging [… to] stir emotions” (Scholz et al. 2018, pp. 2–3). Besides the overall emotionally imbibed visual cultures in Iran as referred to by Karimi, the linking and heightening of aesthetic–emotional experience and communal interaction is particularly observable in the case of Hadāvand, who skillfully leverages such correlations to communicate her Sufi teachings.3 Hadāvand intensively utilizes diverse sensory means such as visual objects, music, as well as hagiographic and personal stories and feelings to enhance the spiritual experience of the participants during the group’s internal rituals.

To better understand how Hadāvand orchestrates intersubjective activities and experiences within her Sufi community, it is helpful to apply George Hagman’s psychological model of aesthetic experience. Hagman coins aesthetic experience as an evocation “of archaic, preverbal experiences of self-in-relation” (Hagman 2011, p. 26). He posits that aesthetic experience fosters “developmentally healthy states of self-experience and relationship” and “expresses, rather than conceals, fantasy and perception” (Hagman 2011, p. 26). Part of such aesthetic experience is the “readiness to organize experience of the world according to certain patterns, colors, sounds, and rhythms” (Hagman 2011, p. 26). As will be examined, Hadāvand not only cultivates a distinctive visual culture within her group but also pro-actively presents herself as an independent social–spiritual actor and emancipated Sufi woman within male-dominated public spaces. In this, Hadāvand stresses the importance of translating the inner experience into external expression; visual markers play a crucial role in this process, as I will demonstrate.

Hagman’s approach is also applicable to the case of Asadī, who formulates her interpretations of visual culture in relation to gender norms on a more abstract and theoretical level. In her specific way, she reflects on the “changing relationship between internal and external aspects of subjectivity” (Hagman 2011, p. 4), viewing the perception of gender as a reflection of one’s spiritual development. Asadī’s understanding of the human’s essence (rūḥ or jān) intriguingly incorporates “the metasubjective (social), the intersubjective (relational), and the personal (subjective)” (Hagman 2011, p. 4). As Hagman argues, the “interrelationship between these levels” constitute “the complexity and profound depth of human aesthetic life” (Hagman 2011, p. 4). Asadī’s perspectives thus emerge as a specific Sufi discourse on aesthetic experience that interweaves the immanent with the transcendental. For her, true self-experience and self-in-relation happen when one transcends the outer appearances and perceives the essence of beings.

3. Ethnographic Self-Reflexivity and Gender Performativity

In their respective contexts, Asadī and Hadāvand embody gendered agency while challenging societal norms and, through this, continue the practice of Sufi women who “negotiate their religious and spiritual identity within particular social locations” (Xavier 2021, p. 176). Merin Shobhana Xavier argues the following in her article “Gendering the Divine. Women, femininity, and queer identities on the Sufi path”:

Sufi women have been significant to the development of Sufism historically, and continue to be in contemporary times, though their voices and experiences often have not been centralized. The lack of representation is not because they have not been present, rather it is because they have been silenced.(Xavier 2021, p. 176)

Similarly, Laury Silvers emphasizes that, despite the silencing of pious and Sufi women in the literature and the gendered norms that limited them in their social participation, they have fundamentally shaped theological and ethical teaching as well as the communal practicing of Sufism (Silvers 2015, pp. 27–30). To further challenge the marginalization of Sufi women and, therefore, to contribute to a more accurate depiction of contemporary female visions in Sufism, I focus in this article on the two Sufi women. In my analysis, I foreground the collected data (the interviews and fieldnotes) with the aim of representing the actual voices of the two interviewees. I highlight their gendered agency and further discuss the ways in which visual culture is connected to their implementation and their interpretation of the Qurʾān and Sufism.4 In this, I follow Justine Howe and apply gender as an “analytical framework” to scrutinize “how gendered norms and practices are essential to exploring the complexities of Muslim social worlds” (Howe 2021, pp. 3, 9). In presenting two women’s Sufi readings of the Qurʾān and their gender performativity, I, as a researcher who identifies as male, am particularly mindful of critically reflecting my potential gender biases to successfully address gender-sensitive issues.5

Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity frames the analysis of Hadāvand and Asadī, their sartorial choices, and subversions of male-dominated spaces as acts of rearticulation. Butler emphasizes that gender performativity does not mean that one can freely choose one’s gender and play with its social implications because one’s “existence is already decided by gender” (Butler 2011, p. ix). Accordingly, Hadāvand’s and Asadī’s gender performativities never completely break with the social expectations and norms of their contexts, but respond to these expectations, however, in refiguring and subversive forms. In their perspectives and social interactions, the two Sufis understand that gender norms are “assignments” (Butler 2011, p. 176) and that they are therefore relative. Hadāvand’s and Asadī’s interpretations of the Qurʾān and Sufism enable them to transcend gender norms while they simultaneously are performing them. They are continuing gender performativities of premodern Sufi women who operated within the patriarchal gender norms and limitations of their respective times and contexts but nevertheless lived their Sufism as women in empowered and often subversive ways (Silvers 2015, pp. 28–29, 40–44).

While conducting the interviews with Hadāvand and Asadī, I pursued to observe how these two interviewees enact their Sufism in “everyday or ceremonial life” (Harvey 2011a, p. 218) to enhance and test what was communicated verbally in the interviews. Consequently, my interpretation of the interviews was informed by what I as a “researcher experience[d] as a participant” (Harvey 2011a, p. 218) in the field (Anderson 2006, p. 384). Through this experimental and embodied participation, I was able to develop an “argument arising from the close familiarity with the living reality of religious activities” (Harvey 2011a, p. 222). Hereby, my aim was not to provide an evocative or narrative autoethnography, in which I read my own experiences as the primary text. Rather, I understand my autoethnographic approach as a reflection of my role as an interviewer and researcher who participated in the life of the interviewees (Butz and Besio 2009, p. 1670). Simultaneously, my presence had an impact on the form and the content of the interviews as well as on the ritualistic and everyday life of my interviewees. The development of a “shared experience”, meaning that I “internalized [and] embodied some local cultural proficiency and insight” (Hervik 2003, p. 167; see below for my application of his concept of “shared experience” particularly in the case of Hadāvand), however, and my subsequent interpretation of the interaction with these Sufi teachers, their students, and family members built the main corpus of these cases’ data. In asking the Sufis on their lived and performed interpretations of the Qurʾān, I focused on the “use rather than the origins of the text” (Harvey 2011a, p. 239). In the following analysis, the visual aspects of these data will stand in the center of attention. Hadāvand’s and Asadī’s performative enactments of their Sufism provided not only insights into their interpretations of the qurʾānic text in the narrower sense but also into their female agency and visions. Thereby, it is decisive not to locate their Qurʾān interpretations within the tafsīr genre but to categorize their exegetical efforts differently.

In this regard, I follow Karen Bauer’s and Sa’diyya Shaikh’s critique of the androcentric, patriarchal interpretive monopoly of conventional Qurʾān exegesis (tafsīr).6 Shaikh argues that such interpretations of the Qurʾān have fostered gender inequality and are continuously misused by men to legitimize violence against women. Feminist readings of the Qurʾān, however, challenge those discriminatory interpretations, aiming for an actualization of gender justice. Shaikh stresses that these interpretive efforts go beyond scholarly endeavors. Indeed, the embodied interpretations of the Qurʾān by Muslim women constitute a “tafsīr of praxis”, providing these women with “resources for female agency and transformation”. Shaikh argues that a stronger methodological focus on such forms of embodied praxis would shed a more nuanced light on the multifaceted modes of Muslim qurʾānic exegeses beyond the genre of tafsīr (Shaikh 2008, pp. 69, 73, 88–89).

Accordingly, I understand Hadāvand’s and Asadī’s interpretations of the Qurʾān and their enactments of these interpretations as such a “tafsīr of praxis”. To scrutinize their specific “tafsīr of praxis”, I will contextualize first Hadāvand and then Asadī and present their Sufi approaches, which correlate with their Qurʾān interpretations. In this, I discuss how they interpret, challenge, and enact visual and material culture and what this means for them in experiencing and presenting themselves as Sufi women in leadership roles.

4. Parvāneh Hadāvand and the Staging of Emotional–Spiritual Experience

Hadāvand’s background remains partly obscure.7 She does not see herself as part of any specific ṭarīqa and refuses titles like shaykha or pīr. However, she calls her practice and teachings Sufism. Her group of students, which she refers to as her “class”, has similarities with those Sufi groups in Great Britain that Pnina Werbner has described as “eclectic and hybrid” migratory networks of social–spiritual intimacy in a new setting (Werbner 2007, pp. 200–201). Hadāvand’s followers, however, come together in their home setting in Tehran and other parts of Iran. Her students are primarily women, some of them mothers and daughters. At these regular gatherings, which are also attended by men, Hadāvand uses Sufi and Shiite concepts to convey her teachings of mystical-gnostic, experiential knowledge (ʿirfān). The setting of these gatherings resembles the events, very popular in Iranian urban centers, in which the Qurʾān and the Persian poetry of Jalāl al-Dīn al-Rūmī (d. 1273) and Muḥammad Shams al-Dīn Ḥāfiẓ (d. 1389) are recited and discussed. Often, these events are built around a prayer group for women who aim to intensify their prayer practice by solidifying their intentional spiritual focus through the communal setting. Niloofar Haeri, in her anthropological study of such Iranian prayer groups, asserts that the quality of prayer for these women depends primarily on the level of emotional experience. Prayer becomes meaningful to them when they are emotionally moved and feel an intimate, communicative connection with God (Haeri 2017, pp. 139, 149, 153).

Hadāvand’s classes, too, are strongly characterized by an intensification of emotional–spiritual experiences. Such an aesthetic and religious experience, intended to convey a certain message, is mediated through an intensification of emotions. The success of such a service also depends on the quality of the interaction between the sender and the receiver. This is the case when the audience emotionally resonates with the created atmosphere and enters the mediated alternative space. This space is designed according to aesthetic rules and, at the same time, shapes them (Scholz et al. 2018, pp. 2, 12, 17). Hadāvand creates such spaces to convey her message of Sufism. In this way, she reconfigures the visual and material cultures of Shiite Islam and Sufism. For instance, for religious feast days, one of her central techniques is to invite her students to design a “table” of composed symbols associated with the holiday. It was around the time of Ashura that I conducted my research on Hadāvand and her disciples. Accordingly, the visual-material markers that constituted the table at that time were related to the persons and the circumstances of the martyrdom of al-Ḥusayn and his followers at Karbala (680) but in the personal style of Hadāvand. Her visual language resonates with, but also differs from, the Ashura visual symbolics of mainstream Iranian society, which she understands as often being too martial and ideologically charged. Subsequently, she pursues a “lighter”, more sublime “energy” (Hadāvand 2016), which she also visualizes through the choice of color. Rather than using black as the dominant decorative color, Hadāvand uses green and white, whose symbolic meanings are discussed below.

Although the students were given the task of decorating the table, this was carried out under the direction of Hadāvand; the table also had to be redecorated several times. The final table (Figure 1) featured a mirror, whose Sufi meaning is explained below, along with candles, dried clay pieces, and ceramic doves. These doves had previously been inscribed with calligraphy, such as the vocative yā Ḥusayn or shahīd (martyr or witness) or dam Allāh (blood of God). The most striking artifacts on this table, however, were several “Hands of Abū l-Faḍl”. Abū l-Faḍl (Father of Virtue) is the honorific name for al-Ḥusayn’s half-brother al-ʿAbbās b. ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib. Before the final battle of Karbala, Abū l-Faḍl is said to have broken through the enemy’s lines to fetch water for his thirsty people (the thirst and dryness are symbolized by the dried lumps of clay on the table). He was surrounded, attacked, and wounded, but, to the end, Abū l-Faḍl held the filled water jar in his hand. Ultimately, this hand too was cut off before he was killed. For Hadāvand, Abū l-Faḍl is the embodiment of utmost spiritual commitment and responsibility. By fostering an emotional–spiritual identification with him, facilitated by the display of his “hands” and banners bearing his name, Hadāvand aims to convey this central message of her interpretation of “being killed in God’s way” (qutila fi sabīl Allāh), a concept she interprets in a specific way, as discussed below. Hadāvand’s performance and creativity in creating an emotionally charged space aims to convey a central message which, in this case, builds on the tragic story of Abū l-Faḍl but expands it to include its Sufi significance.

Figure 1.

Hadāvand’s Ashura table with the hands of Abū l-Faḍl, mirror, candles, dried clay, and ceramic doves. Photo © Y. Hentschel.

To convey such an aesthetic–emotional–spiritual understanding, visual performance is a crucial element (Scholz et al. 2018, p. 18). In religious contexts generally, it is common to use hagiographic narratives, poetry, and music to evoke emotions, with the aim of achieving aesthetic experience as a holistic, sensory, physical, “somatic experience” (Scholz et al. 2018, pp. 6, 12–13). Such emotional intensification, combined with spiritual content, is widespread in Sufism too. There, Sufis stage an atmosphere of emotional–spiritual concentration, often to reach uninitiated followers. A sense of transcendence is enacted with the aim of providing the participants with an experience or “taste” (dhawq) of the supra-real or essential truth (ḥaqīqa). Mostly, this is mediated by providing an emotional identification with spiritually elevated figures such as the Prophet Muḥammad, his family, or the so-called Sufi saints (awliyāʾ), who are said to have attained an exceptional closeness to God (Pinto 2017, pp. 95–105). Hadāvand extensively combines such intensification of emotional experience through stimuli such as music, hagiographic narratives, and poems by Rūmī and Ḥāfiẓ in combination with pro-active communicative interactions. To do this, she uses an intersubjective, metaphorical performance of mirror symbolism.

5. Mirroring and the Crossing of the Vertical and Horizontal

In Sufism, the mirror, and the endeavor to polish it, are symbols of the purification of the self. This metaphor is a very visual one. The untamed self (nafs) is both observed and reflected like a dull, distorting mirror. Through self-critical efforts to polish the mirror and purify the self, the mirror can become so clear that it is no longer perceived as an external object, but as a realization of the purified self, which is then aligned with the ultimate, divine truth (al-Ḥaqq). This is the moment of gnosis (ʿirfān) in which there is no longer an “I” that would distort the process of knowing the divine truth within oneself and in the external world. Subsequently, contemplative perception (naẓar) of divine manifestations (tajalliyyāt) may occur. In the words of the seminal Sufi scholar Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī (d. 1111), the phenomena of the material world are then viewed with the “eye of unity” (bi-ʿayn at-tawḥīd), which enables the Sufi to have a vision that allows him to witness (shahida) that there is nothing in existence that is not God (laysa fī-l-wujūd ghayruhu) (Hentschel 2023, pp. 295–99, 322; on al-Ghazālī, see his Iḥyāʾ and Mishkāt al-anwār in Griffel 2009, p. 254).

Such spiritual, supra-sensory visual imagery is prominent in both Hadāvand’s and Asadī’s discourses. Hadāvand, however, has a stronger inter-personal enactment of this mirror symbolism. In her methodology, each disciple acts as a mirror for her or his fellow disciples and, ultimately, for herself or himself. To facilitate this exchange, Hadāvand regularly calls upon her students, including myself as a participating researcher, to share their thoughts, feelings, insights, memories, imaginings, and dreams in front of everyone. This sharing of experience can lead to a better understanding of one’s own experience and, furthermore, creates resemblance with the experiences of other students, who will then gain new insights for themselves. Hadāvand formulates this process as follows: “Be the mirror for the others. Then you will be the mirror for yourself” (Hadāvand 2016).

During my research, I was a central part of this group dynamic.8 The fieldnotes with which I present most of Hadāvand’s remarks are primarily the result of these intimate communicative interactions. In arguing for his anthropological concept of “shared experience”, Peter Hervik argues that “personal relationships that grew out of our fieldwork situation were (and always are) a prerequisite for acquiring intimate knowledge of individual experiences and histories and for studying individual appropriations of traditional celebrations” (Hervik 2003, p. 175). In the case of Hadāvand, who did not grant me a taped interview, building up such a “shared experience” was critical to collecting data about her. I was willing to participate in Hadāvand’s spiritual program, to emotionally and mentally engage with her program, and “the potential to change in the process” (Hervik 2003, p. 179). Subsequently, Hadāvand had me at her side most of the time and asked me in all the group sharing sessions to express my personal insights, feelings, and interpretations of what I was experiencing when I was with them, especially how I perceived Hadāvand’s teachings, practices, and also the sharing of the other students’ insights. My prominent position in the group dynamic and the extraordinary attention of Hadāvand paid to me were appreciated by many of the group members but also led to feelings of jealousy among others, who, at some point, also made their frustration known. This, however, was again an opportunity for Hadāvand to use emotional excitement for her teachings. The Sufi teacher proactively used my presence, person, and relationship with her students for her teaching agenda. This not only enriched my personal experiential horizon but also allowed me to gain “experimental knowledge” (Harvey 2011a, p. 234) of Hadāvand’s Sufi interpretations and performances of the Qurʾān as well as their visual manifestations.

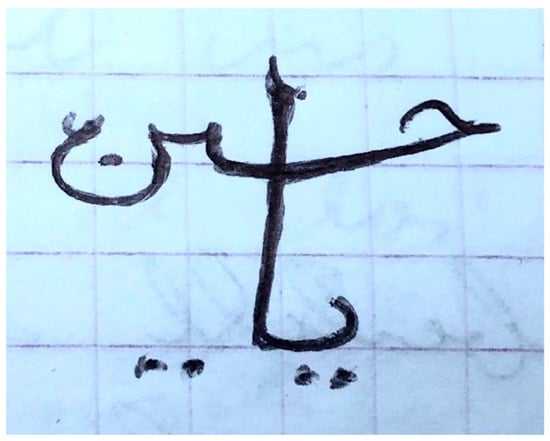

In fact, this autoethnographical approach was in line with Hadāvand’s teaching methodology. According to her, communication and interaction, informed by emotionally–spiritually intensified experience, are central to reaching the intersection of the horizontal/inner-worldly or mundane and the vertical/other-worldly or spiritual. This intersection is where “one becomes real” (Hadāvand 2016), which she explains through the visual crossing of the horizontal and vertical calligraphic writing lines of yā Ḥusayn (Figure 2). Such a calligraphic “picture” “articulate[s] abstract ideas by means of allegorical imagery” (Mitchell 1984, p. 527). Like her usage of Abū l-Faḍl, Hadāvand interprets al-Ḥusayn as a symbol of a spiritual ideal, which, for her, is the intersection of the horizontal and the vertical, visualized through the calligraphy. Calligraphy as an “abstract and ornamental” image is “expressive” of Hadāvand’s teaching and becomes a “pictorial code” (Mitchell 1984, p. 528) in her setting, recurring, for example, in the doves on the Ashura table (Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Calligraphy yā Ḥusayn; copy by Y. Hentschel. Photo © Y. Hentschel.

Hadāvand employs calligraphy and visual symbols to represent the intersection of the “horizontal” mundane and the “vertical” spiritual. Her use of the calligraphic phrase yā Ḥusayn illustrates the Sufi ideals of self-annihilation (fanāʾ) and the remaining (baqāʾ) in social responsibility. By merging spiritual insights with outward expressions, Hadāvand encourages her students to carry their transformative experiences into the broader social context, advocating for active engagement as a form of Sufi practice.

For “describing the states” of annihilating (fanāʾ) the self in God and the consequent remaining (baqāʾ) in the social world with a transformed self, Sufis “have constantly invented new symbols” (Schimmel 2011, p. 146). The calligraphical stylization of the crossing of yā Ḥusayn is not unique to Hadāvand, but she interprets and utilizes it in her specific Sufi pedagogy, which aims towards reaching the intersection of the horizontal and the vertical. This symbol serves as a prime expression of her program to transport the transformative Sufi experience—potentially an annihilation of the lower self (fanāʾ)—into society and therefore realizing baqāʾ. Hadāvand repeatedly emphasizes that “Sufism means to act” (Hadāvand 2016). Therefore, it is not enough for a Sufi to have her or his experience of gnosis (ʿirfān) for herself or himself or solely within the group. The group setting is only the starting point: “First, you practice inside the group. Then, you have to carry it [the experience and insights achieved] into the world” (Hadāvand 2016). Through the teacher’s “guiding” and the “mirroring” interaction within the group, the Sufi will “remember” her or his primordial intersection of the horizontal and the vertical. Reaching this state, the Sufi realizes her or his full potential and becomes “truly vigorous” (Hadāvand 2016). With such actualization of one’s full, mature self, the Sufi is qualified and obligated to engage within the wider society “in taking full responsibility for oneself and the others” (Hadāvand 2016).

Accordingly, Hadāvand enacts her approach of merging the inner and the outer in concrete and practical ways. For one thing, she frequently opens her classes to all kinds of people: poets, journalists, musicians, politicians, religious scholars, and others.9 Further, Hadāvand is actively engaged in a social network that she is eager to enlarge as she argues that, through the Sufi’s active or passive presence, she or he influences the horizontal, meaning the broader society. To demonstrate this agenda, Hadāvand took me to several meetings with political and religious representatives in Tehran and Mashhad.10

6. The Female Sufi Appropriation of Space

In these horizontal social interactions, Hadāvand often challenges gender norms and other conventions. For example, she always wears white and sometimes green or other bright colors, as she points out that these are the colors of the Prophet Muḥammad and the Sufis. Hadāvand’s choice of colors resonates with the color choices in the depiction of the Prophet Muḥammad in mural paintings on religious sites in Iran (as in the case of the Qajar-era Gilan). There, the colors signify “peace, purity, and honesty” (Mahmoudi 2021, p. 31). However, Hadāvand’s choice of wearing these colors also has a strong gendered and sociopolitical aspect, as she dresses this way even in settings where women are expected to wear black or dark colors as a visual gender identifier.11

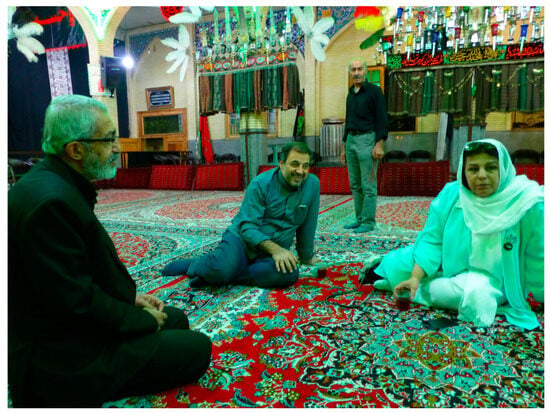

In addition, Hadāvand confidently sits in places that are reserved for men. She does this in official, governmental settings as well as in rural religious places like the Husayniyya (a gathering place for Shiite rites, especially those connected with the mourning al-Ḥusayn’s death) that we visited in the north of Tehran. There, dressed in white and light-blue clothes, she not only took a seat in the middle of the men’s section (Figure 3) but also on the honorary stool from which sermons are held, despite receiving criticism from several men who were present. She also convinced the Husayniyya’s representative to have his picture taken with her. Although this representative welcomed Hadāvand, three of her female students, me, and another male companion12 to sit in the men’s area, the representative at first refused to be photographed with women to whom he was not related. Hadāvand, however, approached him and told him bluntly, “Leave these stupid ideas behind and come into the photograph!” (Hadāvand 2016). Finally, he agreed on the condition that he stands next to a man (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Inside the Husayniyya: Hadāvand (right) sitting in the men’s section, critically observed by a standing man. The Husayniyya’s representative (left), the cousin of Hadāvand’s student (center). Photo © Y. Hentschel.

Figure 4.

Inside the Husayniyya: (from right to left:) the representative of the Husayniyya after being convinced to be in the photograph, the cousin of Hadāvand’s student, Hadāvand, Y. Hentschel, the student whose cousin accompanied us, and Arezou Hasanzādeh. Photo © Y. Hentschel.

Through such social interactions, Hadāvand’s enacts her “tafsīr of praxis” regarding her interpretations of gender equality and female agency that she derives from the Qurʾān and Sufism. She is also eager to visually document this enactment through photography, which, in this case, was not merely a way to record a memory, but rather the very medium of creating her religious identity and authority as a Sufi woman in a religious place. Her choice of clothing that both responds to and defies gender expectations, as well as her confident challenge of gendered spaces, is a fascinating example of gender performativity. Butler stresses that one is not free from gender norms in one’s behavior, even if one challenges these norms (Butler 2011, p. 176). Accordingly, Hadāvand operates within the societally expected, and enforced, gender performativity. She nevertheless acts subversively by making visible and challenging the hierarchy of these norms through her behavior. She implements what Butler formulates as the “exposure or the failure of heterosexual regimes” through the performativity of the “hyperbolic” (Butler 2011, p. 181). Hadāvand, wearing a headscarf and modest clothing, dresses according to the gender expectations in the Islamic Republic. Through her color choices and subtle yet excentric style, however, she exaggerates the sartorial imperatives and challenges the “understated, taken-for-granted quality of heterosexual performativity” (Butler 2011, p. 181). Hadāvand’s mode of dressing and confronting the gendered expectations of the men who are present challenges the patriarchal structures. Her behavior is similar to what Butler calls “The resignification of norms is thus a function of their inefficacy, and so the question of subversion, of working the weakness in the norm, becomes a matter of inhabiting the practices of its rearticulation” (Butler 2011, p. 181; emphasis in original).

Additionally, Hadāvand’s gender performativity and her insistence on documenting her resignification of norms through photographs have to be contextualized within the practice of visiting shrines and other religious sites (ziyāra), which is common in Iran. Visiting (Persian didar, lit. to see) these places is a spatial–visual manifestation of aesthetic experience. In these places, “meaning [is] embedded into the constructed aesthetic” (Honarpisheh 2013, p. 389). The visual representation of a shrine of an Imam, an Imamzadeh (a descendant of the Shiite Imams), a Sufi, of a mosque, or a Husayniyya is “calculated architecture constructed to enrich one’s experience” and to allow one to have a “transformative experience” (Honarpisheh 2013, p. 391). Hadāvand not only enacts such a constructed aesthetic in her own place that “allows people to become affected and affect other people” (Honarpisheh 2013, p. 408), but she also acts in public religious places. There, she often challenges the gender hierarchies and prejudices that have become established in these sites. With this agency, Hadāvand continues a tradition of “Sufi women [throughout history who] maintain and create leadership roles as they unfold within negotiated spaces and relationships, such as in and around Sufi shrines” (Xavier 2021, p. 169). As in the example above, Hadāvand visually negotiates her role as a Sufi woman and religious authority by wearing certain clothing and by taking photographs of such occasions.13

In taking photos at these sites, Hadāvand participates in an aspect of contemporary Iranian visual culture in which “mobile image-making has become an integrated part of Iranian Shia culture and has shaped the ritual and the spatiality of sacred places” (Taherifard 2022, p. 13). Whereas “photography was prohibited in the holy shrine” until recently, “since the emergence of mobile phone cameras, however, image-making has become a popular, integrated practice in the shrine” (Taherifard 2022, p. 9). These photographs are used to create “religious identity” (Taherifard 2022, p. 6), partly also as the “types of image-spaces [that] have been constructed by Iranian revolutionary clerics through the practice of smartphone image-making” (Taherifard 2022, p. 2). Other individuals “reconstructed the shrine’s space for the sake of” their own self-presentation, situating themselves within the conventional visual settings of these places but also challenging them, “allowing [these individuals] to deviate from the conventional gestures of ziyarat without conspicuously transgressing sensitive limits” (Taherifard 2022, p. 12). Hadāvand’s behavior in the Husayniyya (Figure 3 and Figure 4) resonates with this visual opportunity to negotiate one’s position through a religious space. She utilizes the conventional visual markers of modest dressing within a sacred space but gives them a twist according to her specific Sufi perspective and agency with which she redefines the coordinates of these spaces.

7. Transcending the Apparent and Reaching the Perspective of Ḥaqīqa

In an apparent contrast to her confident, often provocative public behavior, sometimes accepted and sometimes criticized, it was surprising at first that Hadāvand refused to give me an interview. She instead introduced me to male Sufis or ʿārifs14 (the truly knowing person; pl. ʿurafāʾ) for this purpose. One should be careful, though, not to attribute this to a possible sense of inferiority on her part due to gender hierarchies. On the contrary, Hadāvand’s religious authority was not challenged on any of the occasions that I observed.

Of greater significance in her decision not to grant me an interview, is her approach to qurʾānic exegesis and her prioritization of experience over intellectual learning. Indeed, Hadāvand does not seem to place much emphasis on being well versed in scripture. For her, it is more important to be embedded in the inner meaning of the Qurʾān, which naturally corresponds to the spiritual state of a person and a concrete situation. According to Hadāvand, when one is connected to God, one speaks in the spirit of the Qurʾān. When someone is “connected” in this way, she or he “speaks and acts in a free and inspired way” (Hadāvand 2016), meaning that her or his actions are in accordance with the Qurʾān. The concrete, audible, and also visually perceptible form of the qurʾānic wording is of secondary importance. For Hadāvand, the function of the revelation is primarily to carry a multidimensional potential of meaning that can be accessed once one has reached the intersection of the horizontal and the vertical. This approach of receiving supra-textual divine knowledge through an intimate connection with God continues prevalent Sufi teachings, exemplified here through the eminent Sufi scholar ʿĀʾisha al-Bāʿūniyya (d. 1517):15

Their hearts are flowing streams of grace; their minds are oceans filled with spiritual potential; their inner vision mirrors hidden revelation; their breasts contain volumes of inspired learning; their tongues are pens recording the eternal decree, and their ears ring with the pre-eternal message.(al-Bāʿūniyyah 2014, p. 145)

Hadāvand explains that, although she cannot quote qurʾānic passages verbatim, she does act upon them. She claims to have reached the intersection of the horizontal and the vertical, so that, in the words of ʿĀʾisha al-Bāʿūniyya, her “inner vision mirrors hidden revelation”. When Hadāvand teaches on a particular subject, often one of the more scholarly of her disciples, companions, or guests will tell her that her words would correspond to what the Qurʾān says in this or that verse. She was also not aware that she was referring to these verses but would intuitively absorb the information in accordance with the specific context (Hadāvand 2016).

For Hadāvand, the concrete practice in a particular moment and the resulting transformative experience are more important than theoretical knowledge. Accordingly, instead of giving me an interview, she invited me to complete her “program” in an “express course” (Hadāvand 2016). Again, she prioritizes experience over the spoken or written word. At the same time, she acknowledged my academic goal of collecting textual data. Therefore, Hadāvand not only let me participate in her Sufi “tafsīr of praxis” but also put me into touch with scholarly experts for the interviews. These happened to be men. In all these interviews, however, Hadāvand was not only present, but she also contributed to the conversations and at times corrected the speakers. And, while she had male Sufis/ʿārifs represent her in these “official interviews”, she always encouraged her English-speaking female student Arezou Hasanzādeh (d. 2019) and others to take ownership of the content of the interviews and translate them to me in their own words.

Before presenting an excerpt from one such an interview, I will first discuss Hadāvand’s central spiritual vision and her search for “true meanings”, in which, again, intersubjective dynamics play a crucial role. For Hadāvand, beyond the pragmatic necessity of translation between languages, words and external appearances are only steps in a continuous overall ongoing process of translating the inner meaning of divine reality into the outer. At the same time, she uses concrete visual markers to make her interpretations and practices visible. These visible markers are intended to contribute, at times also in provocative ways, encouragement for people to change towards a more spiritual way of knowing and perceiving. The intimate interaction between people “who want to understand” (Hadāvand 2016) is paramount to this process and its goal. Ultimately, Hadāvand urges her students to act “in the way of God” (Hadāvand 2016), with full responsibility for themselves and for others. For her, this is the core and the ultimate goal of Sufism. Hadāvand describes such responsibility as the realization of walāya (concord), a state of closeness and intimacy with the divine that allows the Sufi to realize her or his “absolute” self (Hadāvand 2016).

To reach this state, one must be patient and aware of the things she or he wants. According to Hadāvand, the devil (shayṭān) is the nafs la-ammāra bi-sūʾ (Q 12:53), the human lower self that incites negativity. She emphasizes “The devil is in the things we want” (Hadāvand 2016). The Sufi should become aware of this inherent human predisposition and must then avoid being dominated by it. Rather, she or he must immerse her- or himself in a responsibility that transcends her or his personal needs and desires. With the “perspective of ḥaqīqa” (Hadāvand 2016), the Sufi should only receive and pass on God’s provisions. Accordingly, for Hadāvand, the trajectory of the qurʾānic revelation ultimately leads to selfless action. By dedicating oneself to this “path”, the true Sufi attains what the Qurʾān calls qutila fi sabīl Allāh (lit. to be killed in God’s way) (Hadāvand 2016).

Since God grants life and existence (here, Hadāvand uses Persian jān), the most valuable act a human being can commit is to give back jān; meaning that, rather than following her or his individual desires and needs, the sincere Sufi must commit to contributing to a spiritually elevated and more socially just society with her or his whole being and essence (jān), which is connected to God (Hadāvand uses Arabic hū or Persian khodā). Hadāvand explains that this means realizing the central qurʾānic injunction to “take full responsibility for oneself and for others up to the last consequence. Sabīl Allāh is therefore not the path with the goal of reaching God, but the path in God with every step” (Hadāvand 2016; compare with Q 4:94–95, 5:35, 8:74–75, and others). To be “killed” (qutila), for such a Sufi, means to be purified of one’s own negative and self-centered inclinations for the benefit of others. Moreover, the “self-less” Sufi becomes a channel, a mirror in which others can recognize the essential truth (ḥaqīqa) (Hadāvand 2016).

According to Hadāvand, however, ḥaqīqa is something beyond external, visual appearance, beyond male or female, beyond Sunni or Shiite, beyond the words of religious scholars or even Sufis. Acting from the perspective of ḥaqīqa, the committed Sufi develops a different way of seeing that goes beyond the seemingly visual and even beyond categories such as good and evil (Hadāvand 2016), which brings us back to Hadāvand’s call for identification with the characters of Ashura. For Hadāvand and her female students, Zaynab bt. ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib, the Prophet’s granddaughter and al-Ḥusayn’s sister,16 uniquely expresses the spiritual state of a heightened vision and understanding that is not distorted by the “I”. Prompted by Hadāvand to explain the Sufi meaning of Ashura to me, her disciple Hasanzādeh told me that, when Zaynab was brought before the Umayyad Caliph Yazīd after the Karbala massacre, he tried to humiliate and re-traumatize her by asking her what it was like to witness the slaughter of her family. Despite this attempt at emotional abuse, however, Zaynab rebutted Yazīd’s attack and replied, mā raʾaytu illa jamīlan–“I saw nothing but beauty”.17

8. The Perspective of Oneness

In recounting such vignettes of purported spiritual ancestors, especially the descendants of the Prophet, Hadāvand and her circle further explain that they follow the Sufi current known as the Oneness of Existence (waḥdat al-wujūd). This famous Sufi teaching is attributed to Ibn al-ʿArabī (d. 1240) and his followers who understand the plurality of existence as manifestations of divine Oneness (Chittick 2008). Heshmat-Allāh Riāzī is one of the Sufis/ʿārifs introduced to me by Hadāvand to represent her teachings in an interview. According to him, it is the perspective of waḥdat al-wujūd that allows the spiritually sincere ʿārif to realize the Oneness of God, which is manifested in the plurality of inner-worldly phenomena. Riāzī further explains that, according to the Qurʾān, to conduct oneself properly within the diversity of creation, including its gender implications, one must always choose the “best meaning” of a verse or any other situation one experiences (compare with Q 5:93, 25:33, 39:18, and others). To find the “best meaning”, as Riāzī states, one must develop a specific perspective towards existence, in accordance with Hadāvand’s spiritual ideal of the intersection of the vertical and horizontal:

We have to make it clear: do we believe in waḥdat al-wujūd (the Oneness of Existence), or do we believe in qiṣrat al-wujūd (the limitation of Existence) […] Because, if you look at it through the lens of waḥdat al-wujūd, which the Sufis (ʿurafāʾ) believe in, everything is in peace and harmony […]. In this sense, the horizontal level is already vertical as well, because in that sense, although you are on a horizontal level you look at the things from an upper stance, which is again vertical. […] The truly knowing Sufi (ʿārif) looks at things from the waḥdat al-wujūd lens, so she/he sees everything in peace and harmony; so, there is no contradiction between them [men and women and other apparent dualities in existence]. When you look at it from this lens, there is no man or woman, or how you treat your man or how to treat them; it is all one. So, there is no conflict and war between them. All the universe is basically one, and they all are unified in existence. So, the whole of existents is coming from the Existence itself. […] Although there are differences [… in appearance and manifestation], they are all one in Existence. This is waḥdat al-wujūd. And when you have the lens of waḥdat al-wujūd, you can look at the qiṣra [the limited, outer appearance] with peace. But if you look at the things through the lens of qiṣra, then you might be stuck in it, and you might never end up having the view of waḥdat.18

Hadāvand and her spiritual companions like Riāzī may have been influenced by Ibn al-ʿArabī and his gender-transgressing cosmology of the Perfect Human Being (al-insān al-kāmil), as interpreted by scholars such as Shaikh and Xavier (Shaikh 2009, pp. 798–816; Xavier 2021, pp. 165–67). In any case, Hadāvand and Riāzī interpret gender as an ephemeral attribute of the ultimately genderless human being rather than an essential quality. At the same time, Hadāvand underscores her femaleness in challenging androcentric interpretations of the Qurʾān and patriarchal social systems. In doing so, she reconfigures visual-material gender markers such as her clothing to demonstrate her female Sufi agency.

In a similar yet different way, Asadī, the second Sufi interviewee in this study, on whom I direct the focus below, challenges the structures of gender biases as an application of her spiritual experience. This Sufi teacher in Shiraz questions the conventional tendency to categorize the other as being of a different gender and sex and reflects on what constitutes the human being’s essence.

9. Mītrā Asadī and the Universal Human Urge to Find God

Asadī teaches Sufism through the Qurʾān and the works of Ḥāfiẓ and Rūmī. She lives in Shiraz with her family, all of whom are Sufi practitioners.19 They are associated with a specific branch of the Niʿmatullāhiyya ṭarīqa, which is known as Munawwar-Alī-Shāhī or Dhul-Riyāsatayn. This branch operates primarily transnationally and is directed from London by Alireza Nūrbakhsh (name as pīr: Reza Alī Shāh) (Nimatullahi Sufi Order 2025, available online: https://www.nimatullahi.org accessed on 14 January 2025). In Iran, the Niʿmatullāhī Sufis, or dervishes as they prefer to call themselves, were forced into hiding after the Islamic Revolution in 1979 due to repression and institutional bans (Bos 2007, pp. 61, 67, 70). The Munawwar-Alī-Shāhī branch, in particular, had already been persecuted under the Safavids. By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, despite lingering anti-Sufi resentments, this Sufi network succeeded in reviving not only the Niʿmatullāhiyya but also Iranian Sufism in general, with Shiraz as the center of this new Sufi popularity. While, at times resisting state authorities, the Niʿmatullāhī dervishes were also involved in the modernizing and secularizing policies of the Qajars and later of the Pahlevis. In the 1950s, the then newly appointed Shaykh Javād Nūrbakhsh largely unified the Niʿmatullāhiyya sub-branches and established new centers globally. In Iran, the Niʿmatullāhiyya continues to operate but with less public visibility than internationally (Lewisohn 1998, pp. 439–52, 456–61).

Even if Asadī does not consider herself to be closely affiliated with the Niʿmatullāhiyya ṭarīqa, she attends the gatherings of its local branch in Shiraz and is contextualized within the ṭarīqa’s history. For Asadī, the gatherings of the ṭarīqa offer a spiritual infrastructure that she experiences as necessary, especially in the earlier stages of her Sufi development. She has continued to attend the gatherings, using them primarily as an opportunity to practice the spiritually uplifting and meditative performance of dhikr (lit. remembrance). Asadī stresses the high importance of dhikr in the pursuit of experiential knowledge (maʿrifa) and inner vision or transcendental witnessing (mushāhada). Based on the frequent spiritual liminal experiences of practicing dhikr, she studied the Qurʾān and the works of Rūmī and Ḥāfiẓ to expand her Sufi practice. Rūmī and Ḥāfiẓ, through their poetry closely related to the Qurʾān, have had a strong influence on Sufi religious meaning throughout much of the Islamic world for centuries. Ḥāfiẓ’s poetic-mystical expression has been called the “tongue of the unseen” (lisān al-ghayb); his verses, when read in conjunction with the Qurʾān, are widely understood as providing unique insights and access points to the divine, essential truth (ḥaqīqa) (Ahmed 2016, pp. 32–40, 98–99, 235). For Asadī, likewise, the intensive and continuous study of the Qurʾān and the works of the great Sufi masters helped her to answer the essential questions of human existence and ultimately to come to know God.

According to Asadī’s understanding, the Islamic confession of faith, lā ilāha illa llāh, means that “there is nothing (Persian hīč) but God”, therefore, everything is “God: love, light, beauty, joy, sadness, darkness, death, life, you, I, and all other beings” (Asadī 2016). Asadī’s saying resonates with the manifold Sufi traditions who, in their spiritual epistemology, transcend the perceived duality of existence. Here, again, I cite ʿĀʾisha al-Bāʿūniyya to represent this Sufi understanding from a premodern stance:

The lover’s heart is the place of vision. If God makes it worthy to receive the gift of realization, He removes from it the filth of otherness, sweeping away from it the desolation of difference. Then He fills the heart with the light of love and reveals to it the true essence.(al-Bāʿūniyyah 2014, p. 151)

Likewise, and similar to Hadāvand and Riāzī, Asadī stresses that there is a holistic Sufi way of perceiving existence: When the Sufi views existence from the perspective of essential truth (ḥaqīqa), which can be attained through the annihilation of the “I” (fanāʾ), then one realizes that “all human beings manifest God within themselves” and further that “all human beings worship God’s essence (wujūd) in different forms” (Asadī 2016; cf. Q 17:44, 22:18). In the eyes of Asadī, every human being has this “need” to worship God within her or him, whether she or he is aware of it or not. In fact, it would even be a basic need equivalent to “having to breath” (Asadī 2016). The forms of worship, however, can vary and have evolved into different religions and forms of devotion “depending on the society, times, or country” (Asadī 2016). For Asadī, Sufism is the pursuit of “aligning the self with the central point (nuqṭa) of this need” (Asadī 2016) to be in true worship and being aware of it as well; engagement with the Qurʾān is an important means of achieving this goal. In further explaining this endeavor, Asadī alludes to and expresses the metaphor of the mirror through the visual symbolism of the divine light that is reflected in the human being’s inner self and consequently in her or his actions:

If you read the Qurʾān, the Qurʾān’s light will manifest (tajallī) inside you. But what does this mean? [It means that] you transcended your I and are illuminated by God’s light. Everything you are doing now, is no longer what you are doing. Actually, there is no you anymore. Rather, it is what God makes through you. […] If you are on the path of Truth (ḥaqq), everything which you are doing is from God because you are on God’s path (fī sabīl Allāh).(Asadī 2016)

Asadī describes her Sufi understanding of the Qurʾān as a specific, experiential approach to establishing an individual relationship with God; the religious or cultural manifestation and subsequent visual culture of this relationship is of secondary importance, if any. Rather, it is crucial to intimately experience the divine–human connection and to develop the capacity for inner vision. With this inner vision, one is able to transcend outer forms and appearances. Although Asadī found her spiritual path in Sufi Islam, she maintains that there is an unlimited number of paths to God, all based on a unique connection between the individual and the divine truth (ḥaqiqa ilāhiyya). Indeed, one does not necessarily have to study the Qurʾān or be a Sufi or a Muslim to reach this divine truth. Rather, every human being can be absorbed by and in God (majdhūb), even without being aware of it. Asadī further explains that to be absorbed by God is to be chosen by God and to act, perhaps involuntary, according to God’s will. For her, ḥaqiqa ilāhiyya is the all-encompassing driving force and, expressed in her visual language, the divine light that illuminates the human being “by virtue of her or his specific quality”. In this, the Sufi, who has purified her- or his self (nafs) so that the divine light manifests in an unfiltered way in her or him, acts as a mirror of God’s will (Asadī 2016).

According to Asadī, the attainment of the state majdhūb is granted only by God. However, human beings can follow a spiritual path in order to transmute their selves and come closer to God. She explains that the Sufi practices and teachings of a given ṭarīqa, as well as the social-legal rulings of the sharīʿa, support the process of harmonizing the inner self with God’s will; they are the means of polishing the inner mirror and subsequently facilitating the capacity of inner vision. Although Asadī states that some people do not have to “walk the long way of sharīʿa and ṭarīqa” in order to “reach the station of ḥaqīqa and perfection” (Asadī 2016) neither ṭarīqa nor sharīʿa is something outdated for her. For the Shirazi Sufi teacher, sharīʿa is the Islamic ethical-social regulation of organized and harmonious coexistence. It is a system of orientation and correct behavior that is necessary, but only to be observed if one has not transcended her or his limited and biased “human self” (nafs). If one does indeed become “empty of one’s self”, however, then the rules of sharīʿa, such as gender segregation in communal settings, are no longer necessary (Asadī 2016).

10. The Ephemeral Quality of Gender

For Asadī, gender is a relative category that correlates with a person’s level of spiritual development. As long as someone identifies oneself or another as a particular gender, mentally, physically, emotionally, or in any other way, sharīʿa-rulings are necessary. To expand on her argument, she cites the beginning of Q 33:35 inna l-muslimīna wa-l-muslimāt wa-l-muʾminīna wa-l-muʾmināt and explains the following:

In the Qurʾān, we read about the believing men and the believing women. They are mentioned alongside each other, but also independent of each other. On one level this means that they are distinctive. From the perspective of God, however, there is no difference. So, if you have the feeling that the person who is sitting next to you is of a different gender than you, then this means that you are still in yourself and are not yet in the presence of God. As long as this is true, you have to obey sharīʿa because there is still a you.(Asadī 2016)

According to the Qurʾān, Asadī argues, there is ultimately no difference between male and female for God; human beings, however, perceive each other as gendered, because they are created that way on a physical level as well. For Asad, the sharīʿa is meant to help human beings build and maintain society. Since human beings have gendered perceptions, it is necessary to differentiate between the sexes according to different gender-specific qualities and responsibilities.

Asadī, at first, perpetuates conservative gender roles, suggesting that men are physically stronger than women and therefore have “different responsibilities in society” and that women are “gentle and have more empathy [than men] and therefore are in their roles of mothers, wives, or sisters” (Asadī 2016).20 However, Asadī argues that these gender roles and the “big differences between [men and women]” are only relevant in the societal dimension (Asadī 2016). She quickly contrasts her account of essentialized and hierarchical gender roles in human society with her Sufi perspective, in which there are no such attributions of difference. Rather, the essence, spirit, or soul (she uses both Arabic rūḥ and Persian jān) is genderless and seeks an intimate dialogue with God. When the rūḥ has achieved this dialogue, gender norms and regulations are no longer applicable. Asadī sees this mode of gender neutrality reflected in the “many Sufi stories of men and women sitting together, conversing, practicing dhikr together, and so on” (Asadī 2016).21

One of these stories may be that of the two ninth-century Sufis, Umm ʿAlī Fāṭima and her disciple Bāyazīd Bisṭāmī, as narrated by influential Sufis like Abū l-Ḥasan Hujwīrī (d. 1077) (Nicholson 1936, p. 120) and Farīd al-Dīn ʿAṭṭār (d. 1220–1): Fāṭima sits with her male disciple in spiritual communion without any separation, veiling, or the like, until Bāyazīd recognizes the henna drawing on Fāṭima’s hands. Suddenly, he perceives his teacher not any longer as a spiritual guide and companion but as a woman whom he is attracted to. As a result, Fāṭima had to end this free form of conversation (Salamah-Qudsi 2011, pp. 205–6). In their article “An Inquiry into the Nature of the Female Mystic and the Divine Feminine in Sufi Experience”, Milani Milad and Zahra Taheri also refer to this story and conclude, “she has to stop talking to him because he notices her” (Milad and Taheri 2022, p. 9, emphasis in the original). Then, however, without providing any evidence, Milad and Taheri judge the story in a biased way, framing it as Fāṭima had to end the interaction, which had no gender-segregating-rulings between her and Bāyazīd, because “her womanhood is a problem and that her being a woman is a problem […]. The twist in the paradox is that whilst he noticed her, because of his manhood, it is she that is at fault because of her womanhood” (Milad and Taheri 2022, p. 9).

Applying Asadī’s perspective on gender perception in the spiritual process, though, leads to a contrary conclusion: the communion between two spiritually elevated, genderless essences had to end because Bāyazīd, letting himself be distracted by the visual markers of his teacher’s henna drawings, fell back into his mundane “I” as a man and therefore perceived Fāṭima as a woman he felt sexually attracted to. Here, it is not Fāṭima’s womanhood that is a problem but rather Bāyazīd’s diminished spiritual self-awareness, experiencing himself again as a man with a carnal sexual drive, which, in this circumstance prevents him from further experiencing the pure quality of his essence. Fāṭima was aware of her disciple’s state and responded in such a way that their spiritual communion would not be tainted by his longings, especially since she was a married woman. In analogy to Asadī’s view, Fāṭima, who is the teacher and therefore in a more advanced spiritual stage, knew that Bāyazīd, at this moment, was no longer free of his “human I” and therefore had to uphold the sharīʿa rules of good conduct between the sexes.

It is noteworthy and strengthens my argument that, according to Hujwīrī, Fāṭima corrected her jealous husband Aḥmad b. Khaḍrūya al-Balkhī, who was likewise a renowned Sufi. Fāṭima tells him that he does not have to worry about Bāyazīd as he is her “religious consort” who “has no need of [her] society”. This companionship beyond gender implications ended, however, when Bāyazīd noticed her henna and Fāṭima had to tell him, “Now that your eye has fallen on me our companionship is unlawful” (Nicholson 1936, 120). Again, it is not Fāṭima who is at fault but, first, her jealous husband and, then, Bāyazīd, who fell back into their male gendered limitations of seeing the other, even though they were advanced Sufis.

11. Asadī’s Three Stages of (Un)Gendered Being and the Witnessing of the Genderless Essence

Leaving the story of Umm ʿAlī Fāṭima and coming back to Asadī’s discourse, there are three angles from which the question of gender can be approached in relation to her reading of the Qurʾān and Sufism:

- Reading the Qurʾān as a reflection of the perspective of the divine creator: the creator loves men and women equally and created them from a single essence that is beyond any gender difference (Asadī 2016; cf. Q 4:1).

- Reading the Qurʾān as a guide to proper social conduct: In the conventional experience of human interaction, there are differences in sex and gender that require specific forms of behavior. Such behavior should be regulated by the sharīʿa through legal rulings derived from Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh). For Asadī, such rulings are rational and, accordingly, must be followed as long as one experiences the existence of genders and gender differences (Asadī 2016).

- The Sufi perspective, in the words of Asadī:

This is when you are one step beyond sharīʿa, when you are on the path of ṭarīqa [here not in the sense of a specific institutionalized Sufi path, but rather in the sense of a spiritual way of intensified religious practice and liminal experience]: Again, there is no difference between the genders and sexes, because there is no I, or a self. There is only a very intimate, deep, and close relationship between the rūḥ and its Creator. Those who take this path towards ḥaqīqa are able to experience an epiphany that cannot be described in words. They are inspired and provided with direct information. This is the dimension of mushāhada [Arabic lit. witnessing]: there, revelation can also happen for non-prophets, to anyone who is in a pure connection with God. These moments of revelation are beyond time and space. There, the seeker can see higher realities.(Asadī 2016)

By transcending phenomenological, “worldly” appearances, a Sufi can reach a state where she or he can develop a different kind of visual culture in which the divine realities are seen with utmost certainty; Asadī claims to have had such a spiritual visual experience (mushāhada) and put emphasis on her witnessing: “I saw, with my eyes:–God is. I did not read it. I did not hear; I saw”! (Asadī 2016).22

In claiming to have directly and visually witnessed God’s existence, Asadī integrates classical Sufi epistemology and pedagogy aimed at the holistic transformation and development of the human faculties. When the human self (nafs) is trained, developed, and transformed, an immediate realization of the essential truths of ḥaqīqa is sought through an unveiling (kashf) (Ahmed 2016, p. 19; Shihadeh 2007, p. 1). Asadī’s claim of transformative witnessing aligns with Abū l-Qāsim ʿAbd al-Karīm al-Qushayrī’s (d. 1072) description of spiritual unveiling through the transformation of the nafs into its purified state. Striving (mujāhada) for purifying the nafs ultimately encompasses all dense and subtle dimensions and enables the human being to supra-sensual witnessing (mushāhada). Al-Qushayrī emphasizes this transformative epistemological concept in his influential treatise on Sufism al-Risāla al-qushayriyya fī ʿilm al-taṣawwuf in reference to his teacher Abū ʿAlī al-Daqqāq (d. 1015): “I heard the master […] say: ‘If someone adorns his externals with striving, God will beautify his internal self with the vision of Him’” (al-Qushayri 2007, p. 118). This vision leads to enhanced knowledge and certainty. Al-Quahyrī explains this process towards the condition of mushāhada in the following words:

Presence is the presence of the heart [with God]. It can be achieved through a continuous manifestation of the [divine] proof, during which a person finds himself in [God’s] presence through the power of recollection [of God]. This [state] is followed by unveiling, which is presence through clear evidence. In this state one need not see the [divine] proof or seek the path. One is neither subject to the promptings of doubt, nor veiled from the realm of the Unseen. This [state] is followed by witnessing. This means to be in the presence of the Absolute Truth, where there is no room for doubt.(al-Qushayri 2007, pp. 97–98; insertions in the original)

Corresponding to this classical Sufi understanding, Asadī claims to have experienced the states of presence (muḥāḍara) and witnessing (mushāhada). From this transcendental perspective of certainty, there is also no longer any difference between the genders and sexes for Asadī. The Shirāzi Sufi teacher highlights the intention of and the striving for becoming a perfect human being, in the sense of realizing one’s essence (rūḥ). Then, the rūḥ is on “its journey of searching for God”. Asadī emphasizes that, on this journey, “there is no sex, no gender, no man, or woman. All of this is irrelevant because there is God, nothing else” (Asadī 2016).

While claiming such a spiritual vision of unity, Asadī also applies relevance to social settings and their rules of gender performativity. On one of the nights of my stay, Asadī, who, like Hadāvand, preferred to wear white clothes, took me to the dhikr gathering of the local branch of the Niʿmatullāhiyya. There, gender segregation was practiced, and Asadī went to the women’s section, which was partially separated by a curtain during the dhikr. After the dhikr, I talked with the Niʿmatullāhī shaykh about my research question. He gave me only a brief answer. Upon hearing this and returning to her home, Asadī said that she would give me an interview instead. While she kept a low profile for most of the time of my visit as well as within the communal setting of the Niʿmatullāhiyya gathering, she, then, after saying that she now had an idea about my intentions, took her position as a Sufi teacher, demonstrating her own perspectives as presented above.

In relation to the previously experienced gender segregation at the Niʿmatullāhiyya gathering, Asadī’s advocacy for an interview with me can be seen as a self-determined act by which she positioned herself as a woman in a male-dominated context while respecting societal regulations. With this behavior, she performatively supported her teaching that a person who has gone through the Sufi experience realizes that it does not matter what gender a person is and that, in essence, there is no gender, only the “rūḥ meeting God” (Asadī 2016). Such an actualized human being would be able to apply this awareness in her or his daily social life according to the respective setting. It can be deduced that, for Asadī, not all Sufis in the Niʿmatullāhī community, although being “Sufis” by name and practice, are at this level, and therefore, rules must be applied. She concludes the following:

The [advanced] Sufis and all those who have a [true] yearning for truth, all those who are connected deep in their hearts and are able to encounter God within themselves, do realize that everything is right as it currently is. Because everything is in a perpetual cycle of creation. In order to change something, each individual must change herself or himself and their habits.(Asadī 2016)

While acting in accordance with societal gender norms and hierarchies, Asadī advocates an internalized spiritual approach that transcends gender. Noting that the perception and the performativity of gender is a situational and ephemeral mode of experiencing existence, her Sufi perspective has striking parallels with Butler’s seminal arguments regarding the social construction of gender and sex (in Gugutzer 2015, pp. 84–91). Butler’s concept of the body as the “locus of possibilities” (in Gugutzer 2015, p. 88) can be analogized to Asadī’s, and also Hadāvand’s, perception of the human body as the manifestation of the diverse emanations of God’s essential oneness. These manifestations differ in attributes like gender and sex. In their perspective and behavior, the body is real and therefore not superficial. But the individual and social perspectives and judgments of the body, its sex and gender, are mental pictures derived from a culturally constructed vision, “a product of experience and acculturation” (Mitchell 1984, p. 525). In analyzing Asadī’s perspective, she seems to understand gender as such a concept that is primarily relevant in and through social interaction and is constituted by social norms. She juxtaposes these norms with her specific Sufi vision that claims to see realities beyond their constructedness. Asadī does not negate the relevance to adhere to the cultural and societal gendered modes of seeing and being seen but expands them with a vision that transcends the material and socially constructed and regulated.

12. Comparative Discussion: Sufi Corporeality and Transformed Gender Performativity

To highlight Hadāvand’s and Asadī’s positions on the relationship between the Sufi experience of the divine and one’s gender, I again juxtapose their approaches with Milad and Taheri’s judgment. Milad and Taheri argue that “the mystic is feminised in being taken over by the sacred as feminine” (Milad and Taheri 2022, p. 14). In neither Asadī’s nor Hadāvand’s discourse is the concept of God or the human essence gendered though. In contrast, the two Sufis interviewed emphasize that any perspective that ascribes a gendered quality to the Divine—even if referred to as hū (Arabic for “he” and therefore grammatically masculine)—or the human spirit (rūḥ which in Arabic is grammatically feminine) is an expression of not having reached the ultimate “mystical” state of being aware of the true essence (ḥaqīqa). At the same time, both Asadī and Hadāvand, confidently stage their Sufism as women who have a positive approach to their corporeality. Thus, without being convinced by Milad and Taheri’s line of argument that, in Sufism, God “as the ground of the sacred, is, in essence, a creative force, and thus feminine” (Milad and Taheri 2022, p. 16), my findings are in line with their criticism that studies of Sufism often adhere to the misconception that

corporeality, in being reduced to mere superficiality, is thus taken as having lesser significance in comparison to the non-corporeal aspect of the self as spirit or soul. However, this does not always and perfectly align with what is observable about the experiential nature of Sufism. We give consideration to the alternative, where mystical experience constitutes the embodiment of the sacred in human experience–without recourse to the redundancy of corporeality in mystical experience.(Milad and Taheri 2022, p. 2)

Despite existing patriarchal and gender-biased hierarchies in qurʾānic interpretation and religious knowledge production, including Sufism, Sufis like Hadāvand and Asadī share an understanding that the Qurʾān as a call for human beings to self-reflectively accept the corporeal and spiritual diversity of creation as a reflection of divine wholeness and completeness. With a caring, responsible, and inclusive attitude, the Sufi acts as a body while transcending the corporeal manifestations of existence. Consequently, the Sufi can experience the pure relationship between one’s own genderless essence and God. In this regard, Sufis do not understand the body, and especially social perspectives on the body, as the ultimate reality, but they still acknowledge human experience as bodily and therefore gendered. Through the purification of the self (nafs) and the consequent overcoming of gender binaries or other demarcations attributed to the body, Sufis like Asadī and Hadāvand seek to experience an annihilation (fanāʾ) of the duality between the self and God and consequently also between the dualities within creation. The result of this endeavor is the cultivation of a specific Sufi visual culture and perception in which the diversity of the material world is perceived as a kaleidoscopic manifestation of God’s essence and oneness.

In these core teachings, Asadī and Hadāvand align with each other. Likewise, both Sufis interact with society and respond, sometimes subversively, to its gender expectations and performativities. As far as I could observe, Hadāvand challenges gender norms more actively or more publicly than Asadī. It must be kept in mind that my time with Asadī was significantly shorter than with Hadāvand, which limited my observations. Asadī and the people around her make their Sufism visible too, as I could observe when one of Asadī’s sons and other family members showed me around the religious sights in Shiraz, singing Sufi songs, playing the nay flute. However, Asadī did not challenge the gender segregation in the Niʿmatullāhī setting. How she acts in other contexts is beyond my knowledge. From the interaction I had with her, I got the feeling that she acts less overtly than Hadāvand though. In contrast to Hadāvand, who confronts gendered expectations and performativities publicly, Asadī seeks to sensitize to the relativity and temporality of gender more privately through her teaching.

There are many reasons for this difference in public behavior. It is possible that the regional, social, and political context,23 Hādavand’s extensive network, and Asadī’s loose affiliation with the more clandestine Niʿmatullāhiyya influenced the two women’s public display of their Sufism and modes of gender refiguration. Also, the distinctions in their personalities can be an explanation, as Hadāvand acted more extrovertedly than Asadī, who showed a more introverted character. Nevertheless, both Sufis challenge socio-religious and particularly gender norms in direct and indirect ways. Hadāvand, more boldly, and Asadī, in more subtle ways, defy gender imperatives, while they still operate within the normative gender performativity of their social contexts. This behavior is consistent with Butler’s argumentation that gender “performativity is neither free play nor theatrical self-presentation” (Butler 2011, p. 59) and that its “constraint is […] that which impels and sustains performativity” (Butler 2011, p. 60). Therefore, even if Hadāvand and Asadī diverge from some of the gendered norms—for example, by wearing white or bright-colored clothes instead of black—they still adhere to the social imperatives of modest dress. The two Sufis enact the performativity of gender in response to the normative constraints of their social context.

Within these constraints, Hadāvand and Asadī consciously reflect on gender and gender regimes. However, they do not view gender as a subject of absolute interest. They take societal gender norms seriously while, at the same time, oscillating between reiterating and defying these norms. For them, hierarchical gender implications and dynamics are an inner-worldly struggle that can be transcended in the process of achieving spiritual progress. Such transcendence does not mean that a person becomes genderless in her or his social interaction. Rather, a person who has gone through such a liminal process of transformation would and should be able to influence society in subtle ways, especially its constructions and hierarchies of gender.

Consequently, and with different expressions in their performativities, the two Iranian Sufis call for and strive for the realization of gender equality and justice in their respective environments relying on two key arguments: The first is the exegetical perspective that the Qurʾān mandates uncompromising and holistically just social conduct and therefore calls for justice, harmony, and equality between the sexes. Second, the two Sufis claim that spiritual experiential knowledge enables them to have a specific Sufi vision. This vision allows them to recognize that gender is only an affect or attribute of the genderless human essence (rūḥ or jān). In their discourses and symbolic visualizations, Hadāvand and Asadī present a nuanced understanding of gender that again resonates with Butler, who states that “gender is neither a purely psychic truth, conceived as ‘internal’ and ‘hidden,’ nor is it reducible to a surface appearance; on the contrary, its undecidability is to be traced as the play between psyche and appearance” (Butler 2011, p. 178, emphasis in the original). Accordingly, when Hadāvand and Asadī speak of a genderless essence of the human being, they do not negate that the human being experiences gender in internal and external ways.