The Animation of Nature and the Nature of Animation—The Life of Made Objects from the “Record of Tool Specters” to the “Night Parade of Hundred Demons”

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Animism as Belief-Animation as Practice

“the projection of qualities perceived as human—life, power, agency, will, personality, and so on—outside of the self, and into the sensory environment, through acts of creation, perception, and interaction. This projection, like any human expression, requires a medium, and we can take the comparative study of technēs of animation—in art, in religion, in everyday life—as the goal of an anthropology of animation.”

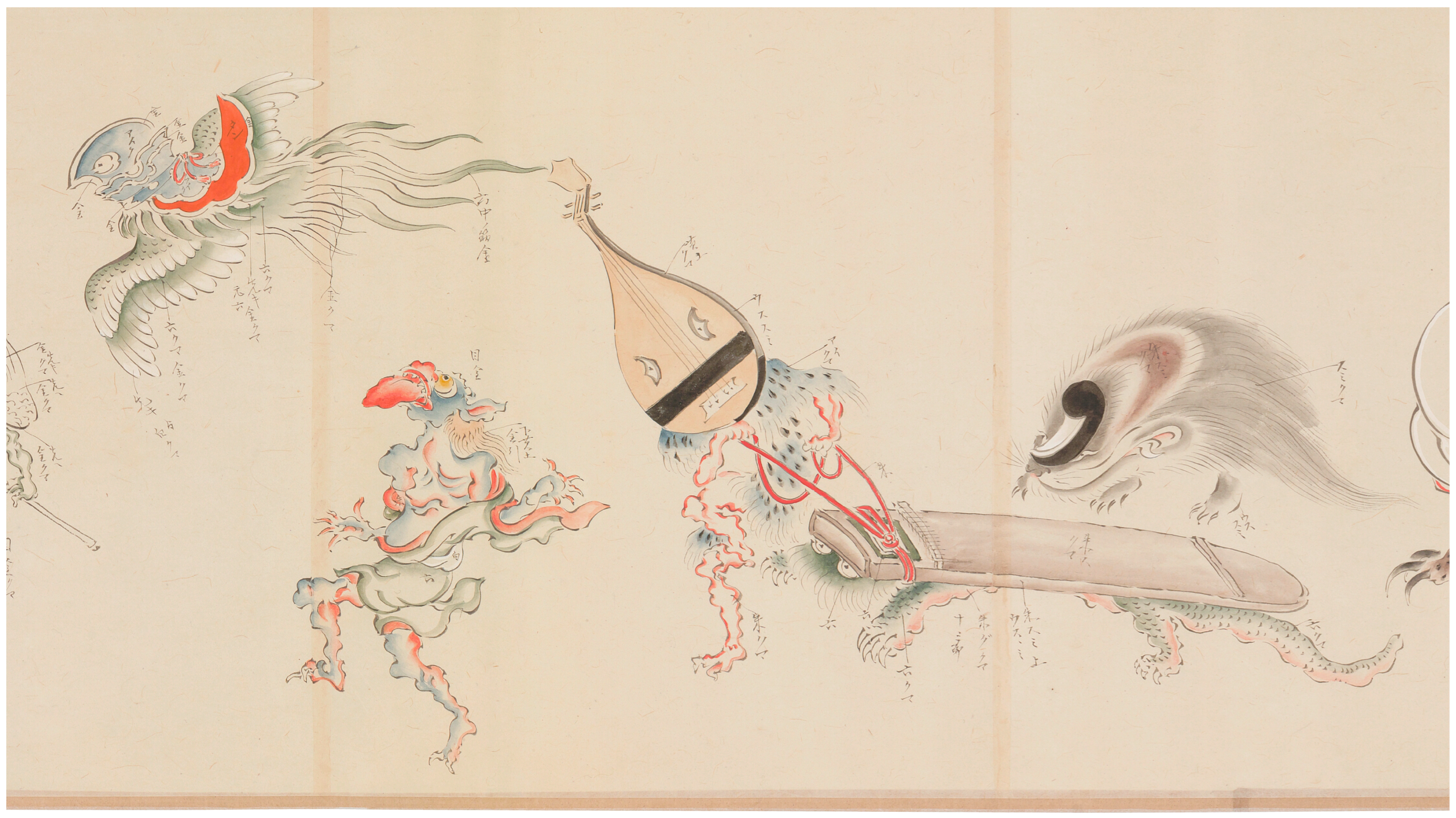

3. The Tsukumogami-Ki

“According to the Miscellaneous Records of Yin and Yang, after a span of one hundred years, utsuwamono or kibutsu 器物 (containers, tools, and instruments) receive souls and trick people. They are called Tsukumogami. In view of that, every year people bring out the old tools from their houses and discard them in the alleys before the New Year. This event, called susuharai 煤払 (lit. “sweeping soot,” year-end house cleaning), is carried out to avoid misfortune caused by tsukumogami tool specters but a year short of a hundred.

This custom of renewing the hearth fire, drawing fresh water, and renewing everything from clothing to furniture at the New Year is thought to have started from the proud extravagance of the well-to-do, but now we understand the custom is meant to prevent the calamities caused by tsukumogami.”(translated by Reider 2009b, p. 1)

“Japan is a divine country where everyone believes in Shinto. While we have already received our forms from the creation god, we have not worshipped him, and this is as if we were nonsentient beings like trees and rocks. I propose that we make the creation god our patron and worship him. That way we will be sure to have a long life with abundant posterity.”

“How then, could the tools—also inanimate objects—need to borrow the nature of others to become themselves? If you wish to know the deepest meaning, quickly escape from the net of exoteric Buddhism and enter Shingon esoteric Buddhism.”

3.1. Interpretive Dimensions

3.2. Visibility/Invisibility

“[…] Lord of Kujō (Morosuke) also met with the night-traversings of a hundred demons. I have not heard what the exact date was, but it was deep in the night when he left the Palace. Thereupon, passing in a southernly direction on Ōmiya Ōji, at the Awano four corners, he suddenly flung down the screens of his carriage, and said urgently, “Take off the ox and drop [the shafts] down! Drop [the shafts] down!” whereupon [his attendants], although they thought it was strange, did so at once. His official guards and his attendants who were clearing the way wondered what was happening and came close to the side of the carriage, whereupon they saw the inner blinds drawn tightly down, and their Lord bowing low with his flat wand grasped in his hand, as if he were paying deep obeisance to someone.

He gave the commands “Don’t rest [the yokes of the] carriage on the stand. You attendants, just stand as close as you can to the side of the yoke, to the right and left of the shafts, and clear the way in a loud voice. You and the bodyguards, keep shouting!”

He then read most solemnly the Snīsa-vijaya-dhāranī [Sonshō Darani]. As for the ox, he had it drawn up to the shady side of the carriage. Now, when an hour or so had passed, he raised the screens and commanded, “Now yoke the ox and move on!” but his attendants did not understand him at all. Although it seems that he later told secretly to those closest to him exactly what had occurred, it was such a strange happening that it naturally became known to the rest of society.”

“Mitsunobu, wishing to paint a convincing likeness of the demons, went straight to the haunted temple. But, though he sat up all night, he saw nothing unusual. In the morning, however, when Mitsunobu opened the shutters, he witnessed an amazing sight: the walls of the temple were covered with an intricate array of ghoulish images. He pulled out his sketchbook and began to copy the weird figures. As he was drawing, Mitsunobu realized that the images were caused by cracks in the damp walls filled with mildew and fungi in a variety of phosphorescent hues.”(quoted in Lillehoj 1995, p. 10)

4. Animation as Technē

4.1. Movement

4.2. Anthropomorphization

4.3. Performance

“Here we witness a radical and massive shift of focus from salon literature for reading aloud and for private reading to a new “media” literature where narratives become so closely allied to the emaki through the practice of etoki that the visual illustration of literature and its oral delivery came to equal if not surpass in importance the text itself. Painting, story, chanter, and even the sounding of musical instruments (often pure sound rather than music) combined to create a total audio-visual experience rare, if not unique, in the premodern history of world literature. The process can quite supportably be termed the cinematization of Japanese literature, and the product, “media literature.” […] Inherent in this shift was a clear separation between author-performer and audience. Literacy or the lack of it was not an issue.”

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The oldest extant version of the scroll, the A type, is kept at the Sōfuku temple 崇福寺 in Gifu prefecture. A version of the more widespread B type is available through the Kyoto University Digital archive https://rmda.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp (accessed on 15 May 2016). |

| 2 | |

| 3 | The title in itself is a complex homonym that can be written as either 九十九髪 (‘ninety-nine hairs’) or as 付喪神 (‘becoming attached and loosing a deity’). The former first appears in the Ise-monogatari to describe old age: ninety-nine is hundred minus one, and if one takes one stroke away from the kanji for ‘hundred’, 百 turns into ’white’ 白, hence ‘white hair’, a sign of old age (Hanada 1973, p. 63). The title cleverly layers both meanings and can therefore be read as ‘becoming possessed by a deity when one reaches old age’. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | This position bears surprising similarities to Tim Ingold’s critique of materiality, in which he argues that because matter has been rendered lifeless by science, it has to be re-animated through what he polemically calls “mind dust”. Instead, anthropology should focus on the “active properties of materials”. Animism therefore would be “a matter not of adding to [things] a sprinkling of agency but of restoring them to the generative fluxes of the world of materials in which they came into being and continue to subsist.” (Ingold 2007, p. 12). |

| 6 | This does not only apply to Japanese art. The Austrian master pianist Alfred Brendel, when asked why he insists on test-playing the piano before a concert, famously said “Some pianist take the local piano as a challenge to show off their ability to master any instrument, but I need to know precisely what the piano does when I play it. If I don’t, the piano plays me.” |

| 7 | This chapter was originally written as a companion piece to “Robot companions: The animation of technology and the technology of animation in Japan” (Gygi 2018). They both share the same critical approach to the notion of animism, but the latter deals with the animation of technology rather than the animation of nature. |

| 8 | Commoners rarely get caught up in otherworldly business, but it occasionally happens, like it did to the hapless man who encounters the parade of demons by accident. He only hears what is happening, but the Oni see him and spit on him, which turns him invisible to others. Shinpen Nihon Koten Bungaku zenshū (1994–2002, vol. 36, pp. 271–76). |

| 9 | The attribution to Tosa Mitsunobu is contested nowadays and this myth of origin was probably added at a later date. |

| 10 | All translations from the Japanese except for those of the Tsukumogami-ki are my own. |

| 11 | “It should be noted that despite the label, women’s pictures were not by any means limited to female artists or to an exclusively female audience. Much like their corresponding designations (‘women’s hand’ and ‘men’s hand’) in calligraphy, the terms ‘women’s picture’ and ‘men’s picture’ (otoko-e) weren’t based on a simplistic gender dimorphism or practiced exclusively by one or the other sex. Rather, then gender adjectives were meant to invoke modes of representation that were deemed appropriate for different spaces of social life at court and consequently elicited different kinds of viewer interaction. Men’s pictures were better suited to illustrate satiric, miraculous, or historical narratives, whereas women’s pictures accompanied poetry-driven texts of courtly fiction.” (Lippit 2008, p. 64). |

| 12 | It is worth adding here that in the yōkai museum in Kyoto (百鬼夜行資料館) the five virtues are rendered in a Japanized fashion as gentleness (odayakasa), obedience (sunaosa), humility (tsutsumashisa), respect (uyauyashisa) and self-deprecation (herikudari). |

| 13 | In Aomori prefecture, this implement was called shitoku (four virtues). When the Buddhist Saint Kōbō Daishi was wandering through Northern Japan he encountered a dog who has lost one leg. Out of compassion he tore off the iron leg of a shitoku and gave it to the dog. Since that time, the iron stove has only three legs, but one virtue more and is thus called gotoku (Nichibunken yōkai database entry C0220096-000). |

References

- Akita, Yūki. 2002. Geta—Kami no Hakimono [Geta: The Footwear of the Deities]. Tokyo: Hōsei-daigaku Shuppan-kyoku. [Google Scholar]

- Asquith, Pamela J., and Arne Kalland. 1997. Japanese Perceptions of Nature: Ideals and Illusions. In Japanese Images of Nature: Cultural Perspectives. Edited by Pamela J. Asquith and Arne Kalland. Richmond: Curzon, pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, John, and Mark Teeuwen. 2010. A New History of Shinto. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Cholodenko, Alan. 2007. The Illusion of Life II: More Essays on Animation. Sydney and London: Power Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Michael Dylan. 2009. Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, Nicole. 2008. Yôkai und das Spiel mit Fiktion in der edozeitlichen Bildheftliteratur [Yōkai and the Play with Fiction in Edo-Period Illustrated Popular Literature]. NOAG 183–184: 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, Fernando G. 1967. Emakimono Depicting the Pains of the Damned. Monumenta Nipponica 22: 278–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gygi, Fabio. 2018. Robot Companions: The Animation of technology and the Technology of Animation in Japan. In Rethinking Relations and Animism: Personhood and Materiality. Edited by Graham Harvey and Miguel Astor-Aguilera. London: Routledge, pp. 94–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hanada, Kiyoteru. 1973. Gajinden. In Muromachi Shōsetsu-Shū. Collection of Novellas from the Muromachi Period. Tokyo: Kōdansha, pp. 35–115. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Graham. 2006. Animism: Respecting the Living World. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1962. Being and Time. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Hendry, Joy, and Massimo Raveri, eds. 2002. Japan at Play. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Holbraad, Martin. 2012. Truth in Motion: The Recursive Anthropology of Cuban Divination. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, Sarah. 2004. The Influence of the Ōjōyōshū in Late Tenth- and Early Eleventh-Century Japan. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 31: 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, Tim. 2007. Materials against Materiality. Archeological Dialogues 14: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Enryō. 2000. Meishin to Shūkyō [Supersptition and Religion]. Tokyo: Kashiwa Shobō. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, Enryō. 2001. Yōkaigaku [Monsterology]. Tokyo: Kashiwa Shobō. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata, Keiji. 1993. Animizumu no Jidai [The Age of Animism]. Kyoto: Hōzōkan. [Google Scholar]

- Kakehi, Mariko. 1989. Tsukumogami Emaki no Shohon ni tsuite. Hakubutsukan Dayori 15: 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminishi, Ikumi. 2006. Explaining Pictures: Buddhist Propaganda and Etoki Storytelling in Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, John J. 2016. Cultural and Theological Reflections on the Japanese Quest for Divinity. Leiden and Boston: BRILL. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, Kazuhiko. 2008. Hyakki-yagyō no Nazo [Mysteries of the Night Parade of Hundred Demons Scrolls]. Tokyo: Shūeisha. [Google Scholar]

- Komine, Kazuaki. 2007. Hyakki-yagyō to Parodi [Night Parade of Hundred Demons Scrolls and Parody]. Ajia Bunka-kenkyū Bessatsu 16: 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kyburz, Josef A. 1997. Magical Thought at the Interface of Nature and Culture. In Japanese Images of Nature: Cultural Perspectives. Edited by Pamela J. Asquith and Arne Kalland. Richmond and Surrey: Curzon, pp. 257–79. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 2010. On the Modern Cult of the Factish Gods. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lillehoj, Elizabeth. 1995. Transfiguration: Man-Made Objects as Demons in Japanese Scrolls. Asian Folklore Studies 54: 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippit, Yukio. 2008. Figure and Facture in the Genji Scrolls: Text, Calligraphy, Paper, and Painting. In Envisioning the Tale of Genji: Media, Gender, and Cultural Production. Edited by Haruo Shirane. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 49–80. [Google Scholar]

- Malafouris, Lambros, and Colin Renfrew. 2013. How Things Shape the Mind: A Theory of Material Engagement. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, Dolores P. 2005. On the ‘Nature’ of Japanese Culture, or, Is There a Japanese Sense of Nature? In A Companion to the Anthropology of Japan. Edited by Jennifer Robertson. London: Blackwell, pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Miyata, Noboru. 1985. Yōkai No Minzokugaku: Nihon No Mienai Kūkan [The Folklore of Yōkai: Japan’s Invisible Space]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Masato. 1984. Serifu to Etoki to Monogatari: Dōjōji Engi Emaki O Megutte [Lines of Speech, the Explanation of Pictures and Narrative: Concerning the Dōjōji Engi Illustrated Scroll]. Bungaku 52: 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Victoria. 2003. The Secret Life of Puppets. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Okudaira, Hideo. 1973. Narrative Picture Scrolls. Tokyo: Kenkyūsha. [Google Scholar]

- Pietz, William. 1987. The Problem of the Fetish II: The Origin of the Fetish. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 13: 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinney, Christopher. 2004. Photos of the Gods: The Printed Image and Political Struggle in India. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rambelli, Fabio. 2001. Vegetal Buddhas: Ideological Effects of Japanese Buddhist Doctrines on The Salvation of Inanimate Beings. Kyoto: Cheng & Tsui. [Google Scholar]

- Rambelli, Fabio. 2007. Buddhist Materiality: A Cultural History of Objects in Japanese Buddhism. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reider, Noriko T. 2009a. Animating Objects: Tsukumogami Ki and the Medieval Illustration of Shingon Truth. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36: 231–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reider, Noriko T., trans. 2009b. The Record of Tool Specters (Tsukumogami-Ki). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, Jennifer. 2014. Human Rights vs. Robot Rights: Forecasts from Japan. Critical Asian Studies 46: 571–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruch, Barbara. 2001. Medieval Jongleurs and the Making of a National Literature. In Japan in the Muromachi Age. Edited by John Whitney Hall and Toyoda Takeshi. Ithaca: Cornell University East Asia Program, pp. 279–309. [Google Scholar]

- Shibuzawa, Tatsuhiko. 1977. Tsukumogami. In Shikō No Monshōgaku [The Heraldry of Thought]. Tokyo: Kawade Shōbōshinsha, pp. 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, James Mark. 2010. Beyond Belief: Japanese Approaches to the Meaning of Religion. Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses 39: 133–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Yoshiaki. 1985. The Shigisan-Engi Scrolls, C. 1175. In Pictorial Narrative in Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Edited by Herbert L. Kessler and Marianna Shreve Simpson. Hanover and London: University Press of New England, pp. 115–29. [Google Scholar]

- Shinpen Nihon Koten Bungaku zenshū. 1994–2002. 88 vols. Tokyo: Shōgakukan.

- Silvio, Teri. 2010. Animation: The New Performance? Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 20: 422–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skord Waters, Virginia. 1997. Sex, Lies, and the Illustrated Scroll: The Dōjōji Engi Emaki. Monumenta Nipponica 52: 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahata, Isao. 1999. Jūniseiki no Animēshon: Kokuhō Emakimono ni miru eigateki/animetekinaru mono [Animation from the 12th Century: Film and Anime Aspects in National Treasure Illustrated Scrolls]. Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Takako. 2002. Hyakki-yagyō no mieru Toshi [Seeing the Capital through the Night Parade of Hundred Demons]. Tokyo: Chikuma Gakugei Bunko. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Jolyon Baraka. 2019. Spirit/Medium: Critically Examining the Relationship between Animism and Animation. In Spirits and Animism in Contemporary Japan. Edited by Fabio Rambelli. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 157–70. [Google Scholar]

- Tōno, Yoshiaki. 1973. Gurotta No Gaka [The Painter in the Grotto]. Tokyo: Bijiutsu Shuppansha. [Google Scholar]

- Tylor, Edward Burnett. 1871. Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Language, Art and Custom, Volume 1, 2nd ed. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Darryl. 2017. Is There Such a Thing as Animism? Journal of the American Academy of Religion 85: 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willerslev, Rane. 2013. Taking Animism Seriously, bu Perhaps Not Too Seriously? Religion and Society 4: 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagiwa, Joseph K., trans. 1977. The Okagami: A Japanese Historical Tale. North Clarendon and Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, Masao. 1991. The Poetics of Exhibition in Japanese Culture. In Exhibiting Cultures. Edited by Ivan Karp and Steven D. Lavine. Washington, DC and London: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 56–67. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gygi, F. The Animation of Nature and the Nature of Animation—The Life of Made Objects from the “Record of Tool Specters” to the “Night Parade of Hundred Demons”. Religions 2025, 16, 1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121534

Gygi F. The Animation of Nature and the Nature of Animation—The Life of Made Objects from the “Record of Tool Specters” to the “Night Parade of Hundred Demons”. Religions. 2025; 16(12):1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121534

Chicago/Turabian StyleGygi, Fabio. 2025. "The Animation of Nature and the Nature of Animation—The Life of Made Objects from the “Record of Tool Specters” to the “Night Parade of Hundred Demons”" Religions 16, no. 12: 1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121534

APA StyleGygi, F. (2025). The Animation of Nature and the Nature of Animation—The Life of Made Objects from the “Record of Tool Specters” to the “Night Parade of Hundred Demons”. Religions, 16(12), 1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121534