1. Introduction

Recently, we have noticed that Arab schools have focused their educational work on students’ academic achievement, more than on the educational value aspect and the Arab virtues that characterize our Arab and Islamic civilization. This is especially true in light of the technological revolution, which is considered one of the most important factors that have led to the instability of inherited and acquired values (

Abu ‘Asba 2012). After reviewing studies of travel literature, it became clear to me that the topic of educational values through literary texts has not received significant attention, as other literary aspects have (

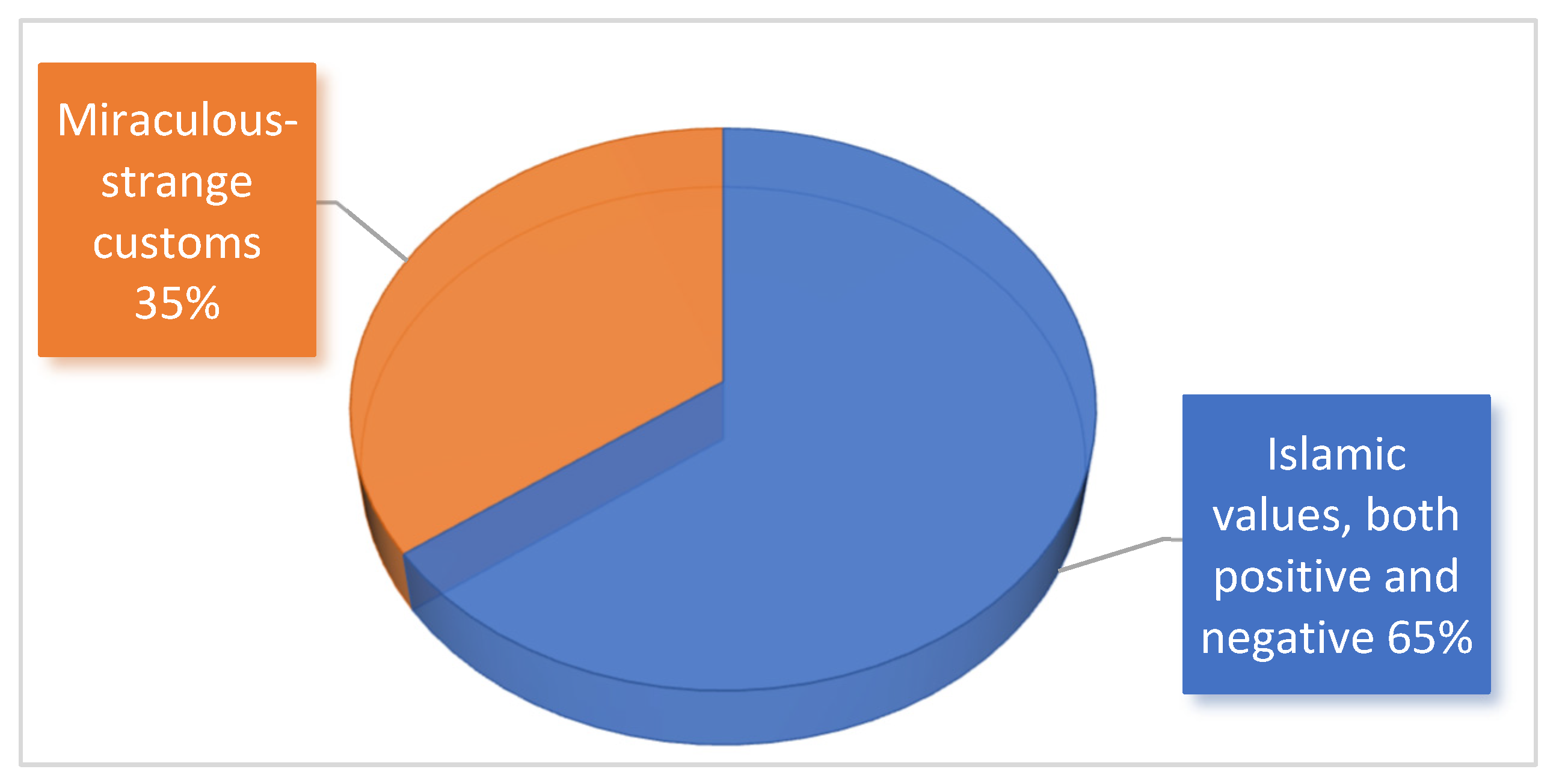

Figure 1).

This study addresses a vital topic that has not received sufficient attention from educational researchers within the researcher’s knowledge. From this standpoint, this study represents a call to instill educational values, as long as education is society’s means of preserving the beliefs, values, customs, and traditions that people cherish most dearly. Provided that they interact with the development and change that our society is going through.

This study also proposes an alternative curriculum and program in schools, focusing on humanistic–civilizational values, through analyzing literary texts, such as acceptance of others, tolerance and rejection of violence, and learning about other civilizations and cultures through travel literature.

Ibn Battuta conveyed values to us through his travels through a method of organized watching and observation. Observation means “intended and directed attention toward a specific individual or group behavior, following it up and monitoring its changes.” The advantage of watching is that it shows us the appearance of behavior without the possibility of falsifying it, especially if it is carried out without the individual watching, such as showing the scene of a woman being burned after the death of her husband in India, which was classified under the title: “Among the Oddities of the Customs of the Lands of India” (Ibn Battuta, D.T., see

Figure 2).

2. Who Is Ibn Battuta?

We can say that Al-Ramadi Jamal al-Din, from the People’s Encyclopedia, is the best person to convey to us information about the biography of the traveler Ibn Battuta, as follows: Ibn Battuta is a famous traveler; his name is Muhammad bin Abdullah bin Muhammad bin Ibrahim bin Abdul Rahman bin Yusuf al-Lawati al-Tanji, from the people of Tangiers; his nickname is “Abu Abdullah”, his other nickname is Shams al-Din, and he is known as Ibn Battuta. He was born in the city of Tangier, in the country of Marrakesh, on the seventeenth of the month of Rajab in the year 703 AH (24 February, 1304 AD) (

Bin al-Khatib 1977;

Barsoum 2002,

2006).

Hussein Mu’nis (

1980), the investigator of his journey, mentioned the name of his father, “Abdullah bin Muhammad bin Ibrahim Al-Lawati Al-Tanji”(

Al-Tazi 2011;

Al-Zarkali 2002).

He was known in eastern countries as Shams al-Din, and in India, he was known as “Badr al-Din,” and his nickname was “Al-Lawati” in reference to the Lawata tribe, one of the Berber tribes, whose clans spread along the coast of Africa as far as Egypt (

Krachkovsky 1957). His nickname, Al-Tanji, is in reference to his birth in the city of Tangier.

Ibn Battuta is considered the greatest of all Muslim travelers and the most renowned among them, to the extent that he was rightfully called the “Shaykh of Travelers” (

Ziyada 1992). He journeyed more extensively than any of his peers, as his travels, as we have mentioned, lasted for 27 years, during which he faced numerous hardships. His journeys were distinguished by their vast geographical and temporal scope as well as the comprehensiveness of the information they conveyed.

3. Theoretical Background

This study is preceded by numerous scholarly works; however, most have not focused on uncovering the values and peculiar customs embedded in travel literature, particularly in Ibn Battuta’s journey. Previous research has generally confined itself to describing the various civilizations Ibn Battuta encountered, highlighting the miraculous and the marvelous in his accounts, or questioning their credibility due to the interplay of factual and fantastical elements.

Regarding earlier studies on travel literature, the majority have overlooked the exploration of the moral values of nations and their unusual customs—whether virtues or vices—spanning from African societies to those of Asia, particularly India and China. Examples of such works include

The Journey in Arabic Literature until the End of the Fourth Hijri Century by Al-Nasser Abdel Razzaq

Al-Mawafi (

1995);

Geography and Travel among the Arabs by Nicholas

Ziyada (

1992);

Moroccan and Islamic Travels and Their Signs in Ancient and Contemporary Arab Literature by Muhammad

Dawawi (

1995); and

Hejaz in Arab Travel Literature by Hafez Muhammad Badishah (

Badishah 2013), which provides an analytical study of travel literature in relation to the Hijaz, alongside an introduction to the most significant travelers to the region and their journeys.

Other contributions include

The Miraculous in Travel Literature: Ibn Fadlan’s Journey as a Model by Al-Khamsa Al-Alawi (

Al-Khamsa 2005), which addresses the theme of the miraculous in travel literature as a form of ancient storytelling;

Journey Literature by Hussein Muhammad

Fahim (

1989), published in the

World of Knowledge series (vol. 138); and

The Best Divisions in the Knowledge of Regions by

Al-Maqdisi (

1906).

In contrast, the present study seeks to shed light on the significance of Ibn Battuta’s journey in identifying the values and customs of the diverse peoples he encountered in Asia. It presents his travel account as a stimulus for conducting comparative studies alongside other journeys—such as those of

Ibn Jubayr (

1968) and Marco Polo—in order to assess the credibility of Ibn Battuta’s documentation in comparison with other Arab and foreign travelers, in terms of both values and customs (

Abd al-Nabi‘ 2024).

Another study published in 2024 at Tashkent University, Tajikistan, focused on the inclusion of travel literature in Arabic prose and its role within world literature. The study demonstrated how travel literature presents the experiences, customs, traditions, and cultural diversity of others, and how it contributes to the transmission of spiritual and social values to readers (

Abd al-Nabi‘ 2024).

A recent study published in

Al-Adab Journal by

Al-shehhi (

2025) examines travel literature in Islamic history and its contribution to fostering civilizational communication among peoples and cultures. The study regards travel as a vehicle for transmitting values such as tolerance, dialogue, respect for diversity, and learning from others. In a related vein,

Abdullah (

2025), in his critical study of Arabic and English literature on Islamic education, focuses on the concept of “Islamic education” and the methods of deriving values from contemporary religious-pedagogical texts, as well as the challenges of integrating them as tools and approaches to promote value-based education for younger generations. (

Abdullah 2025)

Moreover, the experiences of non-Muslim travelers such as the British explorer Wilfred Thesiger—whose The Sands of Arabia achieved wide renown and even surpassed the writings of “Lawrence of Arabia”—demonstrate how travel accounts serve as both ethnographic records and analytical interpretations of diverse societies.

4. Definition of the Term “Values”

Most scholars agree that values are neither absolute nor fixed; rather, they are relative, dynamic, and subject to variation across individuals, environments, societies, and historical periods. Values are not considered innate to human beings but are acquired through experiences such as travel, encounters with other cultures, and the pursuit of knowledge. From an anthropological perspective, value has been defined as “the goal or criterion of judgment for a particular culture—something deemed desirable or undesirable in and of itself” (

Quraiba’ 2005).

5. The Use of the Term “Values” in the Educational Field

The term values is widely employed in the field of education and carries multiple linguistic and conceptual connotations.

From a linguistic perspective, classical Arabic sources highlight various meanings. In Lisān al-ʿArab (vol. 12, p. 500), qīmah (value) denotes the price of an object, while qayyim conveys uprightness or rectitude. For example, the expression “How much has your she-camel stood upright” refers to her value or worth, and “Did the belongings stand upright” means to straighten or set them right. The text further explains that describing someone as “more upright than another” implies being more just, better, or more correct.

Masoud (

Mas‘ud 1986, p. 470) similarly defines

qīmah (plural:

qiyam) as denoting stature, uprightness, and rectitude, while also referring to “upright religion” and even to “the plowshare wood held by the plowman,” reflecting the semantic richness of the term in Arabic.

In English,

values is likewise closely tied to the notion of worth and evaluation. According to the

Oxford English Dictionary (

2006), the verb “to value” means to evaluate or assign a price, while the noun “value” denotes worth or importance. This semantic overlap between Arabic and English indicates a shared conceptual foundation, particularly in their association with evaluation, rectitude, and worth.

6. Values: Idiomatic Usage

In idiomatic usage, values are broadly understood as concepts widely acknowledged by educators, philosophers, and psychologists for their role in shaping morality and cultivating the individual’s spirit in harmony with the religious and cultural vision of society.

Scholars in education have offered various definitions of values.

Al-Nashif (

1981) defines values as the “meaning, position, and location of a human commitment or desire, which the individual chooses independently, in relation to both the self and the environment in which one lives, and to which one remains committed.” Similarly,

Al-‘Ajiz (

2002) describes values as “criteria by which ideas, people, things, actions, and both individual and collective attitudes are judged—whether as good, desirable, and valuable, or as bad, worthless, and objectionable.”

Shukla (

2004) expands this notion, defining values as “anything, material or immaterial, that is socially approved, satisfies human needs, and elevates life to an ideal level.”

Al-Dahawi (

2008, p. 25) offers what he considers the most comprehensive definition: “a set of ethical and behavioral systems governing a person’s inner and outer life, derived from religion, the civilization of society, personal culture, education, and belief in oneself and the world.”

7. Values in Ibn Battuta’s Journey

In his writings, Ibn Battuta highlights two distinct categories of values. The first comprises desirable values—those expressed through good and praiseworthy customs observed among the peoples of the Islamic world, particularly across the African continent and the Arab Levant. The second includes undesirable and peculiar values, which stand in contrast to the norms and traditions of the Islamic world in Africa and the Arab East, as well as to those of Asian societies, including India and China.

The educational values and customs documented in Ibn Battuta’s travels cannot be examined in isolation. The practices of the Islamic world in Africa were closely interconnected with those of the Islamic world in Asia, and both were shaped by wider networks of influence across other Islamic societies. Nonetheless, it is important to recognize that values are not uniform across communities. Each society possesses distinctive characteristics that set it apart, expressed in cultural models and behavioral patterns that crystallize into abstract principles known as “assimilated values.”

Although educational values and customs may share similar labels across societies, their meanings often differ depending on cultural, intellectual, and historical contexts. For instance, the value of respect and loyalty to one’s husband after his death is recognized in both African and Asian Islamic societies; however, the ways in which this value is expressed vary significantly. Similarly, values such as generosity, social relations, the preservation of women’s status, and the advancement of civilization differ in content and practice, even when they share common terminology.

8. The Miraculous Customs in Ibn Battuta’s Journey

Zahir (

1984) highlights a point of convergence between customs and values, noting that both function as motivations and energies for human behavior that are shaped by the cultural context of society. However, he distinguishes between them by arguing that values represent an internal, personal matter based on self-conviction, whereas social customs constitute an external phenomenon. Similarly,

Al-‘Ajiz (

2002) emphasizes that religion serves as a fundamental source of values, while customs emerge from the interaction of individuals within society and are not necessarily rooted in religion. Moreover, he explains that social customs are not inherently prohibited, as some may align with values without contradicting them.

The present researcher adopts the position that values are not exclusively tied to religion. No society is devoid of values, whether positive or negative. Even in non-religious or atheist societies, there exists a set of shared values collectively adopted and practiced by members of the community.

Alongside the Islamic values identified by both teachers and students in Ibn Battuta’s journey, his narrative provides insight into social, political, and religious realities. Yet it also intertwines these with elements of imaginative embellishment. For this reason, some scholars describe aspects of his work as miraculous. This raises an important question: what is meant by the term miraculous in this context?

9. Objectives of the Study

This study seeks to achieve the following objectives:

To enable students to recognize the role of informative texts in instilling Islamic values—such as social, religious, moral, and civilizational principles—into the hearts and minds of young people.

To acquaint students with the most significant desirable and undesirable values prevalent in the societies of the Arab East, as well as in African and Asian contexts, in order to contribute to the formation and development of the integrated Muslim personality.

To encourage students to identify and extract values as they appear in The Journey of Ibn Battuta, through guided questioning and inquiry.

To foster in students the ability to adopt an evaluative stance toward the values and customs presented in Ibn Battuta’s narrative.

To cultivate among students the language of dialogue, the acceptance of differing opinions, the practice of tolerance, and an openness toward others who hold different perspectives.

10. Research Questions

This study is guided by the following research questions:

What are the main values or unusual customs that can be extracted from the selected texts or stories in The Journey of Ibn Battuta?

How can the values or customs derived from Ibn Battuta’s journey be defined and contextualized?

How can these values and customs be classified, using encyclopedic or dictionary definitions, into categories such as religious, social, moral, cultural, aesthetic, positive, and negative? Furthermore, how can customs be classified into ordinary and unusual (strange) practices?

What positions do respondents adopt regarding the values presented in The Journey of Ibn Battuta?

What attitudes do respondents express toward the unusual customs highlighted in Ibn Battuta’s narrative?

What challenges do respondents face in identifying and deriving values and customs from the text?

What is Ibn Battuta’s own position concerning the values and customs described in his journey?

To what extent do Ibn Battuta’s positions align with or differ from the perspectives of respondents, as well as from those of writers and historians?

How do respondents provide a general evaluation of Ibn Battuta’s journey, whether through personal impressions, verbal feedback, or other forms of assessment?

11. Research Methodology

11.1. Research Sample

The study sample comprised 195 in-service teachers (136 females and 59 males) and 245 fourth-year female students enrolled in an Arab college of education. Participants ranged in age from 20 to 45 years. This sample was intentionally selected as it aligns with the objectives of the study: teachers and prospective teachers represent potential agents of educational and social change, capable of fostering a generation grounded in positive civilizational values and contributing to the transformation of contemporary lived realities (See

Table 1).

Accordingly, the study sample consisted of 440 participants, of whom 44.32% were in-service teachers enrolled in the completion track, while 55.68% were fourth-year students in the regular track across various specializations.

Within the student subgroup, the distribution of specializations was as follows: 32.65% in Early Childhood Education, 10.61% in Arabic language, 11.43% in science, 10.61% in mathematics and computer science, 15.92% in English, and 18.78% in special education.

11.2. Research Tools

This study employed a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative, quantitative, interpretive, and content analysis methodologies. The rationale for this integration was to generate comprehensive and reliable answers to the research questions posed to the study sample.

Creswell and Clark (

2007) note that adopting such an integrated approach enhances both the qualitative and quantitative dimensions of inquiry. It enables researchers to capture the verbal and semantic dimensions of the subject matter, while also addressing emotional and social aspects. This multidimensional analysis offers deeper insights than studies relying on a single methodological tool.

Similarly,

Green and Caracelli (

1997), in their evaluative study on the integration of qualitative and quantitative methods, emphasize that the central aim of mixed-methods research is to engage a larger number of participants, thereby achieving a more comprehensive understanding and generating richer knowledge.

Morse and Niehaus (

2009) likewise argue that this methodological integration produces findings that are both more credible and more insightful.

In addition, this study employed an analytical–interpretive approach. As explained by Obaidat, Adass, and Abdel-Haqq (

Obaidat et al. 1995), this method entails systematically monitoring and examining a phenomenon or event—whether quantitatively or qualitatively—within a defined timeframe or across multiple periods. The purpose is to identify the phenomenon in terms of both form and content, and to arrive at conclusions and generalizations that can contribute to understanding and improving reality. Within the present study, this method was specifically applied to derive, classify, and analyze the educational values and customs documented in Ibn Battuta’s journey.

11.3. Research Tasks

In order to identify both the positive and negative values, as well as the unusual customs of the peoples and countries visited by Ibn Battuta across the African and Asian continents, the following applied task was assigned to respondents in both categories (in-service teachers and fourth-year students).

Participants were instructed to select a prose passage or anecdote of at least one page in length from Ibn Battuta’s work Tuhfat al-Nuzzār fī Gharāʾib al-Amṣār wa-ʿAjāʾib al-Asfār (The Masterpiece of Contemplators in the Oddities of Regions and the Marvels of Travel). Their task was to derive the values and unusual customs represented in the text and to organize their findings according to the following steps:

Extraction: Identify the principal value or the unusual (or less unusual) custom within the selected passage.

Definition: Define the extracted value or custom using authoritative Arabic dictionaries and encyclopedias.

Classification: Categorize the values (positive and negative) and the inferred customs into relevant types, including religious, cultural–aesthetic, moral, social, desirable, and undesirable.

Authorial Position: Determine Ibn Battuta’s stance toward the recorded value or custom as expressed in his narrative.

Teachers’ Position: Reflect on the stance of in-service teachers (completion track) as prospective educators in training, regarding the values and customs derived from Ibn Battuta’s journey.

Students’ Position: Assess the perspective of fourth-year students (regular track), preparing for a first degree and teaching certification, concerning the unusual values and customs described in Ibn Battuta’s journey.

It should be emphasized that the applied task constituted an evaluative component, accounting for

30% of the final course grade for both in-service teachers in the completion track and students in the regular track. To guide participants in carrying out this task, a set of structured steps was provided. These included instructions on how to engage with the informational text or narrative passage with the aim of identifying the embedded value or the unusual (or common) custom. In addition, participants received comprehensive and detailed explanations regarding each stage of the task’s implementation (see the attached

Figure 3).

12. Results of the Study

After the applied tasks were collected from both the in-service teachers in the completion track and the fourth-year female students in the regular track, representing various specializations, each task was examined individually. The evaluation focused on identifying the text or narrative selected by the respondent, the value or custom derived from it, and the corresponding classification. Following this, each respondent gave a presentation in which they explained the chosen text with the aim of fostering discussion among peers in the lecture hall and encouraging a dialogic exchange of perspectives.

During the process of preparing and presenting their applied tasks, the participants highlighted three main difficulties they encountered (See

Table 2):

Confusion in selecting an appropriate text or story relevant to the task requirements.

Challenges in understanding linguistic and cultural references, including unfamiliar terms and names such as Zawaqa, Badia, Tuhfa, Amsar, Caftor, Mali, and others.

Difficulty comprehending Ibn Battuta’s style, which is characterized by documentary-like description and the frequent use of complex or archaic vocabulary.

Upon re-examining and analyzing the participants’ responses, the findings were organized under the following three levels:

Level A: Evaluation of respondents’ tasks (quantitative distribution in percentages).

Level B: Classification of values, including religious, moral, social, cultural, and aesthetic dimensions, and distinguishing between positive and negative Islamic values.

Level C: Classification of customs, differentiating between unusual or remarkable customs and those considered relatively familiar or common.

Let us discuss each heading in detail:

Level A: Evaluating the tasks of the respondents (%):

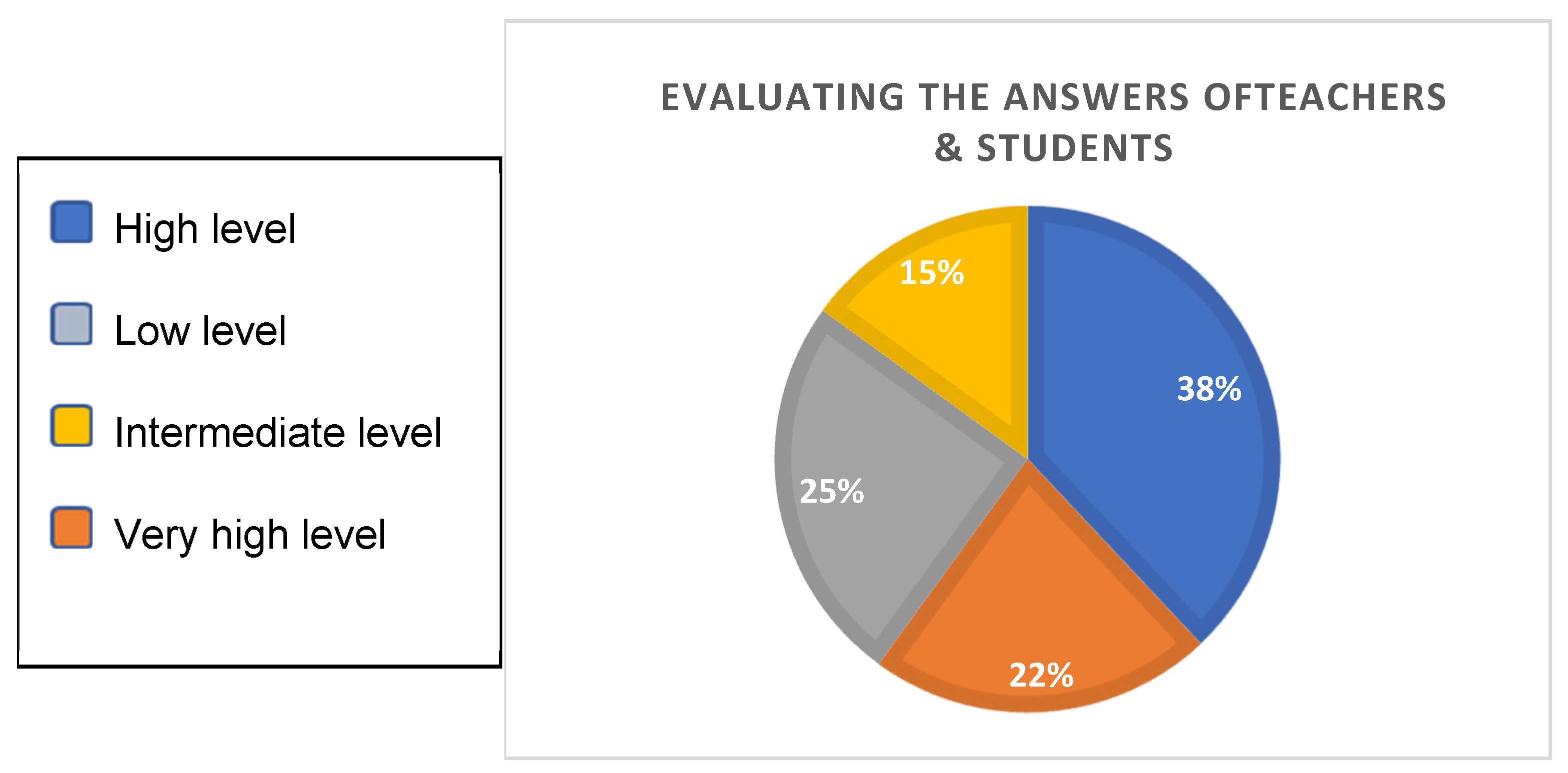

Evaluating the answers to teachers’ work in their applied tasks showed the following results (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5):

- Ninety-five percent of the two categories of respondents carried out the task assigned to them completely, as they were asked (418 of the respondents).

Figure 4.

Results of Evaluating Participants’ Work in Their Applied Tasks.

Figure 4.

Results of Evaluating Participants’ Work in Their Applied Tasks.

- Sixty-five percent of the two categories of both groups chose texts that talk about Islamic values, both positive and negative. (i.e., 272 respondents).

- The remaining 35% chose texts that talked about the wondrous customs of the country that Ibn Battuta visited on the two continents: African and Asian (i.e., 146 respondents).

Figure 5.

Evaluation of Teachers’ and Students’ Work According to the Levels Listed in the Framework.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of Teachers’ and Students’ Work According to the Levels Listed in the Framework.

- Thirty-eight percent of the respondents achieved a very high level: their scores ranged from 86 to 100.

- Twenty-two percent of the respondents were classified at the high level: their scores ranged from 76 to 85.

- Twenty-five percent of the respondents were classified at the intermediate level: their scores ranged from 58 to 75.

The remaining 15% of respondents were classified as low: their scores ranged from 40 to 57.

Level B: Values and their types:

The study reached many results, including:

Ibn Battuta’s journey carries within it a set of Islamic values: literary, faith, religious, moral, social, scientific, cultural and aesthetic. It is considered one of the most important educational sources full of values of all kinds:

Ibn Battuta’s book is full of faith values, as teachers and students extracted values from them, such as belief in predestination, trust in God, relying on God, glorifying God, thanking God, remembrance of God, the inevitability of death, supplication, asceticism in this world, and justice.

It is also full of moral educational values, as teachers and students have extracted values from it: loyalty to covenants, modesty, altruism, mercy, pardon, forgiveness, and advice.

It is also full of social educational values, as male and female teachers have derived values, including visiting, exchanging affection, giving thanks for kindness, helping the poor and needy, raising children, bearing responsibility, cooperation, obedience, benevolence, sincerity, and the company of good people.

Ibn Battuta’s journey included another set of scientific and educational values, as well as cultural and aesthetic values, such as “Seek knowledge even in China”, wonderful things, and virtues.

One of the important things that caught my attention in this research is the interaction of the research sample (respondents) with the topic, as it coincides with the aggravation of the phenomenon of violence and the exacerbation of the crisis of values in our living reality, in our Arab society in particular, and in the Arab and Western world alike. This interaction appeared through the questions posed by the respondents, their interaction, and their participation in dialogue and discussion about the value or custom extracted from Ibn Battuta’s journey.

For this reason, what Ibn Battuta documented in his book relied on the religious foundation. Religious education, from his perspective, is the basis of the well-being and the good of society.

Religious devotional values abounded in his book, and the most important things that the respondents pointed out in their practical tasks were mercy, reward, honor, pardon when able, and forgiveness. As for the devotional values that the research participants derived and that are related to the various religious obligations, they are prayer, fasting, zakat, Hajj, etc.

Positive Islamic values are also essentially recognized moral values, such as forgiveness, tolerance, speech etiquette, and giving. If they exist and are strengthened among people, then society will be reconciled. As for negative values, their impact on society is extremely negative, contributing to its dissolution and destruction.

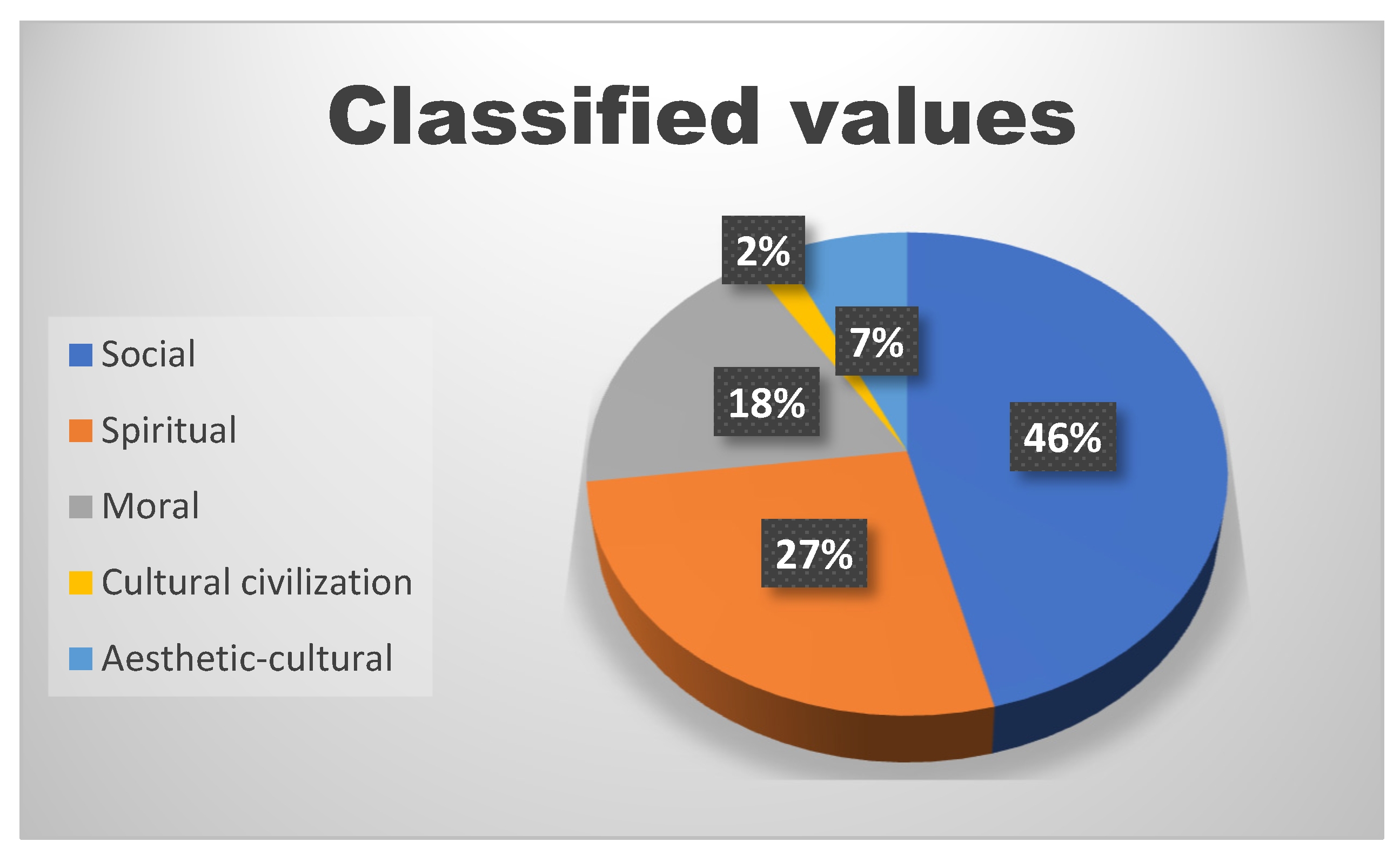

It also appears in

Table 3 that the grading of social values received the largest number according to the classification of the respondents, numbering 31, while the rest of the values came in the second and third levels, as shown in the following figure (

Figure 6):

The attention of the research participants was also drawn to the fact that Ibn Battuta focused in his book on the virtues of women, their generosity, and their achievements. He also praised their social awareness, intellectual and political maturity, their customs and traditions, their behavior, their dress, their morals, their beauty, their roles, their relationship with their husbands, etc.

On the other hand, the researchers extracted the prominent customs of the peoples of Al-Amsaar, which Ibn Battuta integrated into during his three travels (

Table 4).

What are the respondents’ attitudes towards strange customs?

As for the positions of the respondents regarding the strange customs mentioned in Ibn Battuta’s journey, we see them divided between a believer, a skeptic, and those who deny it. This position was consistent with the criticisms of his contemporaries, such as Ibn Khaldun, Al-Balfiqi and Ibn Al-Khatib, accusing him of lying, because of the strange events and matters contained in his journey. Teachers and college students alike were surprised by these unnatural customs and considered them blasphemous, infidelious, incompatible with Islamic law, close to fantasy, and out of touch with reality and the natural afterlife.

What sparked the revolt of female academic students was the custom among Hindus, which is women burning themselves. The vast majority of them chose the text, which talks about this custom that is foreign to their world and their religious reality.

What is surprising is the multiplicity of the positions of the respondents. We mention Ibn Battuta’s position on the issue of marrying multiple women, especially his admission of leaving them, while they were under his responsibility, and his pride in leaving their children without a breadwinner. What angered them was that Ibn Battuta grew up in a religious environment and was raised in accordance with the provisions of Islamic Sharia, and this position contradicts the provisions of Islamic Sharia.

The image of the enchanting woman, which contributed to confirming the miraculous character of Ibn Battuta’s journey after she underwent the river test. This confirms the miraculous nature of this character.

Among the events that caught the attention of the respondents, and which Ibn Battuta mentioned in his journey when he assumed the judiciary in India, were “The woman who eats human hearts, and that was a time of drought, and the woman who did that was called Kaftar, who ate the heart of a boy who was next to her, and they brought the boy dead. The Sultan’s deputy summoned her and ordered her to be burned with fire.”

This story aroused the interest of the respondents and gained their admiration for Ibn Battuta for writing this story down on his journey because of its life lesson. But they were also amazed at the transfer of this wonder to the world of the supernatural and marvels. It is a supernatural event that contains confusion, astonishment, doubt, hesitation, and doubt, and raises questions about its realism and unreality.

To illustrate the participants’ perspectives, some of their direct remarks are worth citing:

The conclusion drawn from these responses is that Ibn Battuta employed a narrative strategy that initially led recipients to believe that what he described was both accurate and realistic. Some participants remarked,

“We enjoyed reading about these strange events. We became even more impressed by Ibn Battuta’s ability and ingenuity to convey them in a distinctive manner full of wonder.” In other words, the respondents were divided into two groups. The first group defended him: they supported his accounts, agreed with his descriptions, and admired the way he documented the unusual customs and events of Asia, particularly in China and India. The second group, however, did not defend him: they expressed astonishment and accused him of fabrication, echoing the criticism of Ibn Khaldun and others who had similarly questioned his credibility (

Ibn Khaldun 1956).

13. Discussion

After the respondents presented their models and reflected on their answers, it was found that 80% of the teachers—both male and female—appreciated this practical task, considering it an effective means of learning about the values and customs of others. They noted that it encourages dialogue among students while simultaneously exposing both teachers and students to the positive and negative dimensions of Islamic values, thereby reinforcing the positive aspects. Respondents further observed that the activity helped to foster empathy toward others and to strengthen mutual respect among male and female teachers of different religions and sects. Some expressed their interest in transferring these texts from travel literature into broader social subjects in schools, such as general culture and social education, to be presented and discussed with students. In their view, such integration would deepen and consolidate positive values, thereby contributing to the development of a promising generation that respects the values and customs of other peoples.

The respondents also expressed satisfaction with the implementation of this task, which focused on analyzing the content of Ibn Battuta’s journey. They emphasized that it enhanced dialogue and participation in public debate. Among their remarks were statements such as “This task has strengthened our feeling of closeness with other students, and our participation in preparing and planning practical lessons has contributed to improving our vision and behavior toward others.”

After analyzing the data, it became evident that 86% of the respondents in the evaluation process indicated that the mission activities were highly meaningful to them, primarily due to their contribution to the development of their future professional performance. The data also revealed the extent to which these activities fostered rapprochement and cooperation between students and teachers within the same group, as they engaged in discussions about the values of the countries Ibn Battuta visited across both continents—Africa and Asia alike.

When asked about the objective of their participation in planning and preparing the activities of the applied mission, the respondents replied “The goal was to unveil the values and strange customs of the peoples of the countries that Ibn Battuta visited on his journey, which lasted nearly 29 years.”

Moreover, 63% of teachers and students reported that they had involved teacher colleagues and other students from different specializations in the activities and analysis of the texts. In addition, 40% of the participating teachers stated that they encouraged their peers to incorporate the selected texts into social education lessons as well as into other subjects, including general culture, homeland, society, religion, and Arab civilization.

In short, the responses of both teachers and students reflected positive and deeply satisfying feelings as a result of being exposed to the values and customs—both familiar and unfamiliar—of different peoples and countries through Ibn Battuta’s journey, A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travel. Despite the criticism directed at Ibn Battuta, his work remains the foremost reference for students of literature, geography, history, education, and Islamic civilization, due to the wealth of information it provides about various countries during the eighth century AH (fourteenth century CE). Indeed, his fame has only grown, to the extent that his name has become proverbial in discussions of travel literature.

14. Summary

The central conclusion of this study is the alignment between what writers, researchers, and Orientalists have observed about Ibn Battuta’s journey and what the surveyed participants—comprising teachers and fourth-year college students—expressed in their evaluations of his travel account. One group affirmed the authenticity of his reports, supporting and defending his narratives, while another expressed skepticism regarding their credibility.

Overall, Ibn Battuta’s journey reflects both positive and negative Islamic values across the Arab East, the African continent, and the Asian continent, including Turkey and Persia. This study therefore calls for the integration of positive educational values and the virtues of the peoples of the Islamic world into the education of students and teachers alike. Education, as the principal means by which society preserves its most cherished beliefs, values, customs, and traditions, should remain responsive to the social transformations and developments of each era.

Ibn Battuta’s journey is recognized as an invaluable reference filled with information about Islamic civilization. It has long been regarded as a vital document in the history of Islamic culture, serving as a primary source for those seeking insights into Islamic values, as well as the marvels and curiosities of diverse lands. For this reason, it rightfully bears the title “The Masterpiece of the Beholders”—a true “gift to the beholders.”

15. Conclusions

Ibn Battuta’s journey, entitled “The Masterpiece of the Beholders of the Curiosities of the Lands and the Wonders of Travel”, abounds with both positive and negative Islamic values, along with wondrous behaviors, morals, traditions, and customs that he conveyed from the lands he visited across the African and Asian continents.

The texts of Ibn Battuta’s journey are marked by a distinctly religious character. His first travels were directed toward Mecca and Medina, motivated by his desire to perform the Hajj and to study with, and learn from, Muslim scholars representing diverse regions of the Islamic world.

Among the most prominent values emphasized in his writings are hospitality, generosity, and the protection of the wayfarer. These values allowed Ibn Battuta, for example, to spend many years traveling throughout the Islamic world without experiencing alienation or threat. The religious dimension is thus evident in his accounts; however, what is even more striking in his narrative structure is his remarkable ability to envelop the allure of strangeness within a sacred framework, thereby granting his accounts an air of truthfulness and credibility—at least to the average recipient.

16. Recommendations

We recommend that educators and teachers integrate selected texts from Ibn Battuta’s journey into the curricula of higher stages of education (preparatory and secondary), particularly in subjects such as Arabic language, history, geography, social education, Islamic civilization, and Islamic art. These texts can serve as valuable references and sources that enrich current debates on systems of values proposed for instilling in students. Such values may be extracted from the texts through applied model lessons that can be addressed via individual reflection, small-group discussions, or general classroom dialogue.

We also recommend that lecturers in colleges and universities employ travel literature in their teaching—most notably The Journey of Ibn Jubayr and Ibn Battuta’s “The Masterpiece of the Beholders”. These works may be integrated into courses in Islamic civilization, sociology, education for values, and Arabic language. The objective is to facilitate broad academic discussions framed within the educational-values perspective, particularly in light of the crises brought about by profound societal and cultural transformations.

Finally, we recommend conducting further detailed studies and research on educational values and their various types as derived from the travel literature of other travelers who lived during or prior to Ibn Battuta’s time.