Astronomy and Chen Zhixu’s Neidan Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Origins and Development of the Tradition of Taoist Internal Alchemy Cosmology

3. The Astronomical Foundation of Chen Zhixu’s Internal Alchemy Theory

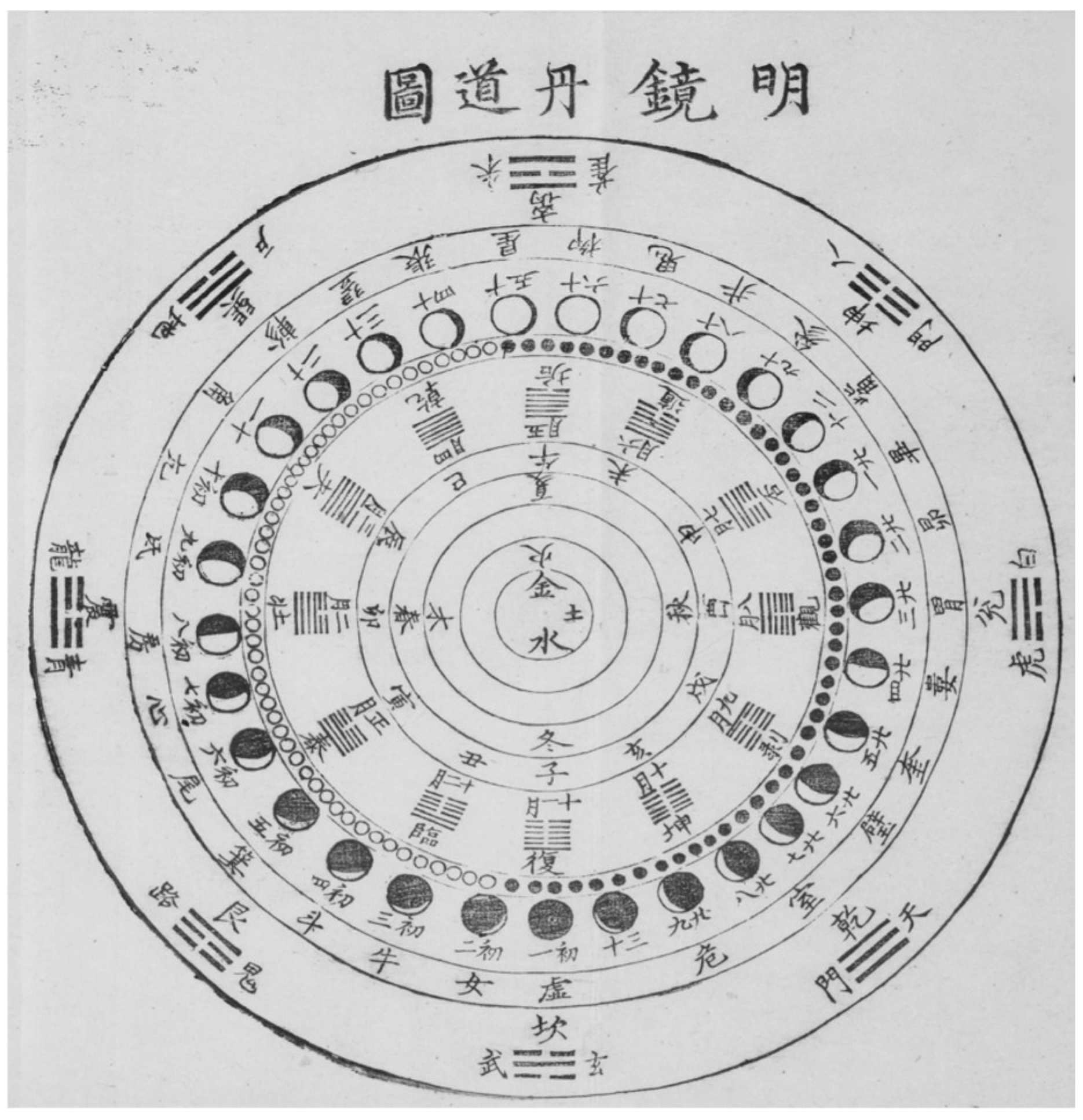

3.1. The Cosmological Symbolism in Chen Zhixu’s Internal Alchemy Theory

“In the Mao month, there are four Yang lines and two Yin lines, the dominance of Yin is about to depart (Yin’s influence is waning), and since Yin presides over destruction, although the two Yin lines in Mao are no longer capable of overcoming Yang, their destructive force has not yet dissipated—hence it is termed punishment. In the You month, there are four Yin lines and two Yang lines. The dominance of Yang is about to depart (Yang’s influence is receding), and since Yang presides over creation, although the two Yang lines in You cannot overcome Yin, their life-force persists—hence it is termed virtue.”

卯月乃四陽而二陰, 陰道將離, 而陰主殺, 是以卯之二陰, 陰已不能勝陽, 然殺氣未絕, 故為刑也. 酉乃四陰而二陽, 陽道將離, 而陽主發生, 是以酉之二陽, 陽雖不能勝陰, 然生意尚存, 故為德也.(Jindan Dayao, p. 29)

“Muyu (沐浴 Bathing, referring to a pivotal process of purification, balance, and refinement in cultivation) occurs precisely when Yin and Yang are in equal proportion, and the energies of Qian (鉛 lead, another Yang-symbolic essence) and Gong are in a state of stagnant stability… It demands that one’s body be like withered wood and one’s mind like dead ashes—this is precisely what is referred to as muyu.”

沐浴者, 適當陰陽相半, 鉛汞氣停…直要形如槁木, 心若死灰, 是謂之沐浴也.(Jindan Dayao, p. 29)

“When the solar terms have completed a full cycle, (the practitioner) sheds the mortal frame and achieves divine transformation… When the elixir matures, the sacred embryo (聖胎 Shengtai a metaphorical symbol refined from golden elixir) is fully formed, and the sacred infant (嬰兒 Ying’er) is accomplished—thus becoming a Zhenren (真人 a transcendent being).”

節氣既周, 脫胎神化…直至丹熟胎完, 嬰兒成就而成真人.(Jindan Dayao, p. 29)

“I compiled this Jindan Dayao. Within it, defying taboos, I offers detailed elaborations—unfolding and clarifying systematic explanations that directly open doors and pave the way for later practitioners seeking immortality.”

作此《金丹大要》. 其中冒禁詳述, 開顯條說, 直與後來學仙之士, 辟門引路.(Jindan Dayao, p. 3)

“Thousands of scrolls and chapters, whether lengthy odes or short verses, are nothing but constructed illusory images and symbolic forms—using one thing to metaphorize another. What difference is there between this and “discussing emptiness within emptiness itself” or “recounting dreams while still in a dream”? If one seeks their practical effects, it is as vague and futile as chasing the wind… These works are muddled and disordered, rambling and fragmented… They mislead later practitioners, and the confusion they cause grows all the more severe.”

千篇萬卷, 長歌短句, 無非假像設形, 借彼喻此, 何異空底談空, 夢中說夢, 求其功效, 茫如捕風…顛倒錯亂, 枝蔓條折…迷誤後人, 惑也滋甚.(cited from Jindan Zhengzong (金丹正宗 Golden Elixir: The Orthodox Tradition, an internal alchemy text compiled approximately during the Song and Yuan Dynasties, which criticizes the abuse of metaphors in previous internal alchemy works. Jindan Zhengzong, p. 188)

3.2. The Empirical Astronomical Knowledge in Chen Zhixu’s Internal Alchemy Theory

“alchemy cultivation is closely tied to cosmic creation and evolution, thus making it more difficult than governing a state. Furthermore, it uses lunar mansions to analogize the human body. As for the phrase “The sun unites with the essence of the Five Elements 日合五行精”: During the Zi, Chou, and Yin months 子, 丑, 寅月, the Sun conjoins with the Five Classical Planets in the northern celestial direction… In the period of Emperor Yao 堯, the “celestial center (the celestial reference point)” was set at Zi 子 position (north); on the winter solstice of the Jiachen 甲辰 year, the Sun resided at the Xushu (虛鼠 Void Rat) Mansion; during the Taichu 太初 era of the Han Dynasty (104 BCE–88 BCE), the Sun was at Qianniu Mansion (牽牛 Ox Herd) on the winter solstice; during the Taiyan calendar (太衍历 compiled by the Buddhist monk Yi Xing 一行 and officially adopted in 727 CE) era, the Sun was at Dongdou Mansion (東鬥 Eastern Dipper); and from the Song Dynasty to the present, the Sun has been at Nanji Mansion (南箕 Southern Winnow) on the winter solstice. This is what is referred to as axial precession. Thus, when the Sun aligns with the Fire火 and the Earth 土 (two of the Five Elements 五行, corresponding to Mars and Saturn), its luminosity is enhanced; when it aligns with the Metal 金 and the Water 水 (the other two, corresponding to Venus and Mercury), its radiance becomes even more brilliant.”

修丹一事, 紧关造化, 故比御政为难. 复以星宿喻身. 日合五行精者, 子, 丑, 寅月, 日合五星於北…堯時天心建子, 甲辰冬至, 日次虛鼠;漢太初冬至, 日次牽牛; 唐太衍冬至, 日次東鬥; 宋至今冬至, 日次南箕. 此謂歲差. 故太陽得火, 土益精光; 得金, 水愈炫彩.(Zhouyi Cantong qi Fenzhang zhu, p. 229)

“In the heavens, Taiyin (太陰 the moon) has twelve celestial degrees, during which it forms a conjunction with the sun; in human physiology, Shaoyin also has twelve (corresponding) degrees, guiding practitioners to practice in secrecy while studying the scriptures (Zhouyi Cantong qi). This is the proper and fundamental order of Yin and Yang.”

天上太陰有十二度, 與太陽合壁, 人間少陰有十二度, 以隱行看經, 此陰陽之正也.(Zhouyi Cantong qi Fenzhang zhu, p. 249)

“The celestial sphere has 365.25 degrees. Each day and night, the heaven complete one full cycle, which is considered one day. The sun moves one degree per day, and when it travels 30 degrees, it constitutes one month; the moon moves slightly more than 30 degrees per day, and when it completes a full cycle around the heaven, it is called one month. The sun moving one degree is referred to as one day.”

周天三百六十五度余四之一, 每昼夜, 天一周遭为一日. 太阳一日行一度, 行及三十度为一月; 太阴一日行三十度有奇, 月一周天, 谓之一月. 日行一度, 谓之一日.(Zhouyi Cantong qi Fenzhang zhu, p. 215)

“The celestial bodies of the sun and moon serve as models for Yin and Yang: Just as the sun and moon reside in heaven with their lunar phases and solar alignments, so do Yin and Yang exist in the world through alternating cycles of compliance and reversal, generation and completion (Shunni Shengcheng 順逆生成 Shun refers to the natural cycle of life, aging, sickness, and death, while Ni refers to reversing the forces of Yin and Yang to attain the Elixir). The sun embodies the pure pneuma of Yang, termed Great Yang 太陽; the moon embodies the pure essence of Yin, termed Great Yin太陰.”

法象日月以喻陰陽: 日月麗乎天而有朔望對合, 陰陽在乎世而有順逆生成. 日乃純陽之炁, 謂之太陽; 月乃純陰之精, 謂之太陰.(Zhouyi Cantong qi Fenzhang zhu, p. 215)

“Those who are ignorant may claim that when the sun and moon stand opposite each other, they are separated by the Earth. Little do they know of the vastness and height of the heavens, and the principle that the Yin and Yang pneuma can achieve subtle penetration despite obstacles.”

愚人或謂日月對望, 為地所隔. 彼豈知天之高遠, 而陰陽之炁, 有隔礙潛通之理.(Zhouyi Cantong qi Fenzhang zhu, p. 226)

“These bodies (the Yin and Yang essential pneuma) are separated by as many as tens of thousands of li; yet if Huang Po acts as a go-between to facilitate their union, even the farthest distance becomes extremely close.”

二物間隔, 動幾萬里, 若得黃婆以媒合之, 則雖至遠而至近也.(Zhouyi Cantong qi Fenzhang zhu, pp. 251–2)

“Through fasting in unison (with a shared devotion to the Dao), performing incense processions six times daily, and reciting the scripture ten times, blessings will descend immediately, dispelling all misfortunes.”

齊心修齋, 六時行香, 十遍轉經, 福德立降, 消諸不祥.(Taishang Dongxuan Lingbao Wuliang Duren Shangpin Miaojing zhu, p. 427).

“In the Shuofang (朔方 the remote northern frontier of ancient China), dawn breaks before a cooked sheep’s shoulder blade is fully done; if one goes even farther, the rising and setting of the sun occur in an instant (cited from Gexiang Xinshu. p. 243). This is what is meant by the ‘operation of heaven and earth’, which also has its periods of decline and termination… If we literally assert that the heavens and earth will truly come to an end, how many people would survive? Who would be able to perform fasting rituals and incense processions? And who would be able to recite scriptures?”

朔方最遠之地煮羊胛未熟而天曉, 又遠則去日之出沒, 只在須臾。是為天地運度, 亦有否終…若直謂天地果然運終, 則民生其有幾何? 孰得而修齋行香, 又孰得而誦經乎?(Taishang Dongxuan Lingbao Wuliang Duren Shangpin Miaojing zhu, pp. 427, 429)

“These two approaches—Daoyong and Shifa—coexist. As for Shifa, it simply adheres to the literal meaning of the scripture, which needs no further elaboration here. Regarding Daoyong, for practitioners returning of the Golden Liquor to the Cinnabar Field (Jinye Huandan 金液還丹the process of elixir completion through nine cycles), if they have not yet obtained the Primordial pneuma (Xiantian Yiqi 先天一炁 the subtle breath upon which the human body relies to revert to its primordial origin), their entire body remains in a state of Yin. The empty space within the Li hexagram—is this not what is metaphorically called the woman? … ‘all attained growth and completion’ signifies that the embryo within the Golden Cauldron (Jinding 金鼎cultivation container, a metaphorical expression of the human body, borrowed from the external alchemy term) is fully formed and its pneuma is sufficient.”

此道用與世法兩存. 世法則依經云, 不又復贅. 道用則修金液還丹之士, 未得先天一炁, 則一身皆陰. 若離中虛, 豈不謂之婦人乎?…皆得生成者, 金鼎之胎完炁足.(Taishang Dongxuan Lingbao Wuliang Duren Shangpin Miaojing zhu, pp. 396–7)

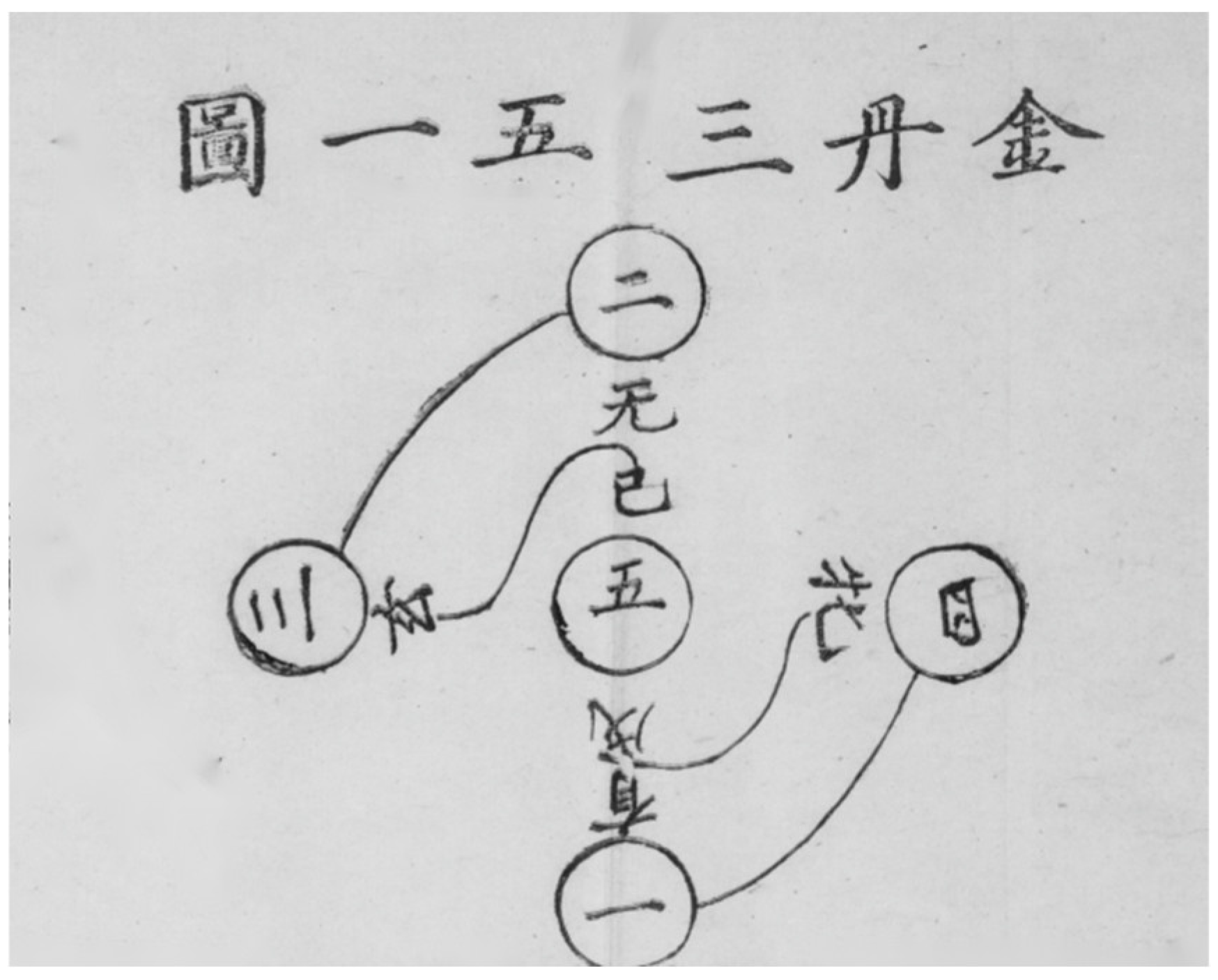

3.3. The Mathematical and Metaphysical Structure of the Universe in Chen Zhixu’s Internal Alchemy Theory

“The celestial sphere are round like pellets; the center of this spherical body is the focal point of the Liuhe (六合 literally ‘the target of the Six Directions’—referring to ‘up, down, east, west, north, south’).”

天體圓如彈丸, 圓體中心, 六合之的也.

“The Sun is close to the celestial sphere, while the Moon is far from it.”

日與天 (球) 相近, 月與天 (球) 相遠.

“The Sun’s spherical body is large, and the Moon’s is small.”日之圆体大, 月之圆体小.(Gexiang Xinshu, pp. 235, 245, 246)

“Sanwu Liji states… Numbers begin at one, take form at three, reach completion at five, flourish at seven, and attain their end at nine. Thus, the distance between Heaven and Earth is 90,000 li. From this, we know that the distance from Earth’s surface to Heaven is 90,000 li, and the distance from the Earth’s surface to the farthest point of Heaven beneath the Earth is also 90,000 li. Therefore, the total height of Heaven’s celestial sphere (i.e., from its highest point above Earth to its lowest point below Earth) is 180,000 li.”

三五曆紀曰…數起乎一, 立於三, 成於五, 盛於七, 處於九, 故天去地九萬里. 則知地上至天九萬里, 地下亦九萬里, 是天之體中高十八萬里.11(Taishang Dongxuan Lingbao Wuliang Duren Shangpin Miaojing zhu, p. 426)

“One million three hundred and fifty-eight thousand li below Zhongmin Heaven lies the Formless Realm (無色界 Wusejie), which consists of four heavens. Thirty-six thousand li below the Formless Realm lies the Form Realm (色界 Sejie), which consists of eighteen heavens—within the Form Realm, there are six Subtle Dust Heavens (輕塵天 Qingcentian), six Fine Dust Heavens (細塵天 Xicentian), and six Coarse Dust Heavens (麤塵天 Cucentian). Thirty thousand li below the Form Realm lies the Desire Realm (欲界 Yujie), which consists of six heavens. Five hundred and twenty trillion li below the Desire Realm, there are 500 million celestial heavens (五億諸天 Wuyizhutian) and Eight Directional Circular Worlds (八圜世界 Bahuanshijie) formed through transformation and generation.”

種民天之下一百三十五萬八千里, 生無色界四天; 無色界之下三十六萬里, 生色界一十八天; 色界之內, 有輕塵六天, 細塵六天, 麤塵六天. 色界之下三十萬里, 生欲界六天, 欲界之下五百二十億萬里, 化生五億諸天, 八圜世界.(Taishang Dongxuan Lingbao Wuliang Duren Shangpin Miaojing zhu, p. 410)

3.4. The Adaptation and Integration of Astronomical Research in Chen Zhixu’s Internal Alchemy Theoretical System

“The sage is one who is skilled at seizing and utilizing the creative and transformative powers of the cosmos… The cosmos lies within their grasp, and the transformation and generation of all things originate from their very being. The sage is one who is skilled at abiding in the Mean to regulate the external; they understand the pitch-pipes and the calendar and comprehend numerical principles.”

聖人者, 善奪造化也…宇宙在乎手, 萬化生乎身也. 聖人者, 善處中以制外也, 明律曆而知數也.(Zhouyi Cantong qi Fenzhang zhu, p. 222)

“When a sage descends into the world, they observe the heavens above and examine the earth below, carefully discerns between Yin and Yang—taking Yin as the symbolic token and Yang as the vital essence… Heaven begets sages, who infer and examine the measures and calculations of the cosmos, taking actual effects as verification and symbolic signs as evidence. They observe the phenomena of the sun and moon, and imitate their forms and patterns… They set up a gnomon to measure shadows, taking this as a standard and model; they ascertain temporal rhythms (seasons and hours) through such observations, and discern good and ill fortune.”

聖人之降世也, 仰觀俯察, 精審陰陽, 以陰為符, 以陽為命…天生聖人, 推考度量, 以效為驗, 以符為證. 觀日月之象, 擬諸其形容… 立表測影, 以為格範, 占知時候, 察定吉凶.(Zhouyi Cantong qi Fenzhang zhu, pp. 227, 228)

“Beyond Heaven and Earth (Intermediate Cosmos) lies the Great Cosmos… The present Heaven and Earth is but one entity within this Great Cosmos—just as humans are one entity within this present Heaven and Earth, and just as the Dao is one entity within the human body. Therefore, the human body is yet another Small Cosmos.”

天地之外有大天地焉… 今之天地, 屬大天地之中之一物耳, 即如人是今天地中之一物也, 即如道乃人身中之一物也. 是故人身又一小天地也.(Taishang Dongxuan Lingbao Wuliang Duren Shangpin Miaojing zhu, pp. 50, 51)

“Those with fixed numerical determinism will inevitably face decline; those with fixed manifestations will inevitably perish… in contrast, only the Golden Elixir is the primordial pneuma: it transforms without form or appearance, transcending the realm of the Five Elements, exceeding the limits of image-number, and abides in the realm of cosmic creation and transformation.”

有成數者必有否, 有定象者必有終…唯金丹乃元始一炁, 變化無形無象, 超五行之外, 出象數之限, 立乎造化之象也.(Taishang Dongxuan Lingbao Wuliang Duren Shangpin Miaojing zhu, p. 427)

“To unite with them, when the moon is born in Geng, metal is at its peak and water is clear, signifying the gathering of metal on the third day (in a lunar month). Hence, it is said to unite with the brilliance of the sun and moon.”

合之者, 月生於庚, 則金旺水清, 乃採金於三日, 故云與日月合其明.(Jindao Dayao, p. 46)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Although Chen claimed that his spiritual lineage originated from Ma Yu 馬鈺 (1123–1183), one of the Seven Perfect Ones of Quanzhen (全真七子 Quanzhen Qizi), in fact he came from a special transmission branch of the Jindanpai Nanzong (金丹派南宗 the Southern Lineage of the Golden Elixir). For more research on Chen Zhixu’s life and key deeds, see Zhou (2007). The Southern Lineage of the Golden Elixir Branch was a Taoist internal alchemy school active in Southern China during the Southern Song Dynasty. It is generally believed that, regarding the specific cultivation sequence, the Southern Lineage of the Golden Elixir Branch advocated “prioritizing Ming (命 vitality the physical and physiological life-energy) before Xing (性 nature the spiritual and mental essence of a person) 先命後性”, while the Northern Quanzhen School in the same period advocated “prioritizing Xing before Ming 先性後命”. For more research on this school, see Gai (2013). |

| 2 | Among these, Zhouyi Cantong qi Fenzhang zhu stands out as a particularly influential contribution to Yuan Dynasty Cantong studies (参同学 studies on Zhouyi Cantong qi). Specifically, this work serves as an annotation and elaboration on Zhouyi Cantong qi 周易參同契, the most significant Dandao (丹道 Taoist alchemy) text in Taoism, and reorganizes as well as systematizes the structure of the original scripture. Jindan Dayao, which is noted for its straightforward and accessible writing style, as well as its well-structured and logically coherent content, is a valuable introductory text on internal alchemy for Taoist practitioners. Taishang Dongxuan Lingbao Wuliang Duren Shangpin Miaojing zhu, also known as Durenjing zhu 度人经注, and the Wuzhen Pian Sanzhu are respectively annotations on Lingbao Duren Jing (靈寶度人經 The Lingbao Scripture on Salvation), one of the foundational texts of Taoist cosmology, and Wuzhen Pian (悟真篇 Folios on Awakening to Perfection), an important core text on Taoist internal alchemy. For more research on Chen Zhixu’s Taoist work, see (Zhou 2007, pp. 83–97); Zeng (2004); (Kong and Han 2011, p. 271). |

| 3 | Additionally, according to the research of Livia Kohn, the traditional Zhonglü internal alchemy system (钟吕道 Zhonglü Dao, an early Taoist internal alchemy cultivation school of the Sui and Tang Dynasties) deeply integrated the Gai Tian (蓋天 an early Chinese astronomical theory about the open universe) cosmological model with the logic of “celestial–terrestrial correspondence” in internal alchemy practice, forming a resonant system of “cosmic rhythms—the human body as a microcosm” (Kohn 2020, pp. 37–9). Meanwhile, Chen Zhixu adopted the more mainstream Hun Tian cosmological model in ancient Chinese astronomy. Therefore, Livia Kohn’s work also provides methodological inspiration for this study. Finally, the research by scholars such as Nathan Sivin on the relationship between Taoism and science also serves as an important contextual reference (Sivin 1978). |

| 4 | Qirang refers to a method of religious practice conducted through rituals such as prayer, fasting, and religious assemblies. Cunsi, on the other hand, is a meditative practice that involves visualizing the internal processes of the body and their connection with cosmic phenomena. |

| 5 | |

| 6 | In the corresponding relationship between astronomical phenomena and alchemical fire times in the human body, the principles and images of Yijing play a special role. Serving as an abstract mathematical and symbolic tool, Yijing hexagrams systematically and conceptually extract, correlate, and represent the changes in astronomical phenomena and those of the human body—thus constructing a theoretical system that connects Heaven, Earth, and humanity (W. Zhang 2017, p. 193). |

| 7 | Axial precession refers to the phenomenon in which the long-term precession of Earth’s rotational axis causes the westward shift in the vernal equinox point along the ecliptic, thus resulting in the tropical year being shorter than the sidereal year. |

| 8 | Chen Jiujin notes that distinguishing the orbits of the Sun from those of the Moon is a notable contribution made by Zhao Youqin to the development of ancient Chinese astronomy (J. Chen 2013, p. 439). |

| 9 | Shao Yong’s theory of “Yuan-Hui-Yun-Shi” is also a form of kalpic thought. It holds that the universe will periodically perish and be reborn in a calendrical cycle of 126,000 years (referred to as “Yiyuan 一元”), and all social rise and fall also follow this calendrical cycle. “Rather than observing nature and explaining natural principles through social scientific thinking, the theory instead like uses certain natural scientific methods to frame social history Z. Chen 2019, p. 615).” This reasoning deviates from the fundamental spirit of empirical science and thus was criticized by Zhao Youqin. |

| 10 | For more research on “the numbers of Heaven and Earth”, see Chen and Guo (1998). |

| 11 | The original text of Sanwu Liji can be found in Yiwenleiju (1965, pp. 2–3). |

| 12 | Zhao Youqin’s original statement reads: “This mountain (the Kunlun Mountains 昆侖山 a mountain range in the northern part of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau) is more than 30,000 li away from the Western Sea and less than 20,000 li away from the Eastern Sea 其山距西海三萬餘里, 距東海不及二萬里 (Genxiang Xinshu, pp. 242–3)”. This, which implies a diameter of 50,000 li for the Earth—is a rough estimate he made of the radius of the Eurasian continent. Additionally, Chen Zhixu assumed that the east–west length of the oceans beyond the continent was another 100,000 li; thus, the total east–west length of the earth was 150,000 li. |

| 13 | According to Ramanujan’s approximation formula L ≈ π[3(a + b) − (3a + b)(a + 3b)], a = 9 and b = 7.5 yields a circumference of the ellipse of 51.95. |

| 14 | According to the values calculated that Wang Fan 王蕃 (228–266 an astronomer and mathematician of the Wu Kingdom during the Three Kingdoms period) calculated using the Gougu method (勾股法 a method based on the Pythagorean theorem), “the value of the celestial diameter 天徑之數” was 162,788 li, 61 bu, 4 chi, 7 cun, 2 fen 十六萬二千七百八十八里六十一步四尺七寸二分, while the circumference of the celestial sphere was approximately 512,000 li (Jinshu, p. 287). These computational results have been influential for a long time. |

| 15 | Based on the diameters of the Sun and the Moon provided by Chen Zhixu, the cross-sectional area of the Sun is approximately 5.94 × 105 square li, while that of the Moon is approximately 3.17 × 105 square li, with a ratio of 1.88:1 between the two. This ratio is close to the value provided by Zhao Youqin. |

| 16 | Sun Weijie notes that “Under the influence of the Buddhist concept of celestial realms, Lingbao Duren Jing is currently recognized as the earliest Lingbao School scripture that explicitly integrates the ‘Three Realms Heavens 三界天’ and the ‘Thirty-Two Heavens of the Four Directions 四方三十二天’—two key components of the ‘Thirty-Six Heavens Theory’ 三十六天說—though the integration is still relatively crude.” (Sun 2022, p. 37). |

| 17 | The sage is an ancient Chinese conception in Daoism. Sages are those who align with the Dao and live in harmony with nature. |

References

Primary Sources

Daodejing Zhushi 道德经注释 [Commentary on the Tao Te Ching]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局, 2012.Daozang. 1988. Daozang 道藏 [Daoist Canon]. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press 文物出版社; Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House 上海書店出版社; Tianjin: Ancient Books Publishing House 天津古籍出版社.Gexiangxinshu 革象新書 [New Book on Reforming Observations of Celestial Phenomena]. In Siku Quanshu四庫全書 [Photographic Reprint of the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries]. Taipei: Taiwan Commercial Press 臺灣商務印書館. vol. 786.Jindan Dayao 金丹大要 [Great Essentials of the Golden Elixir]. In Daozang道藏 [Daoist Canon]. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press 文物出版社; Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House 上海書店出版社; Tianjin: Ancient Books Publishing House 天津古籍出版社. vol. 24.Jindan Zhengzong 金丹正宗 [Golden Elixir: The Orthodox Tradition]. In Daozang道藏 [Daoist Canon]. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press 文物出版社; Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House 上海書店出版社; Tianjin: Ancient Books Publishing House 天津古籍出版社. vol. 24.Jinshu 晉書 [History of Jin]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局, 1973, vol. 11.Siku Quanshu. 1986. Siku Quanshu 四庫全書 [Photographic Reprint of the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries]. Taipei: Taiwan Commercial Press 臺灣商務印書館.Taishang Dongxuan Lingbao Wuliang Duren Shangpin Miaojing zhu 太上洞玄靈寶無量度人上品妙經注 [Commentary to the Wondrous Scripture of tthe Upper Chapters of the Numinous Treasure on Limitless Salvation]. In Daozang道藏 [Daoist Canon]. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press 文物出版社; Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House 上海書店出版社; Tianjin: Ancient Books Publishing House 天津古籍出版社. vol. 2.Wuzhenpian Qianjie 悟真篇淺解 [A Simple Explanation of the Wuzhenpian]. Edited by Mu Wang 王沐. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局, 1990.Yiwenleiju 藝文類聚 [Literary and Artistic Works: A Categorized Compilation]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局, 1965, vol. 1.Zhouyi Cantongqi Fenzhangzhu. 周易參同契分章注 [Chaptered Commentary on the Seal of the Unity of the Three from Book of Changes]. In Zangwai Daoshu 藏外道書 [Taoist Texts Outside the Daozang]. Chengdu: Bashu Publishing House 巴蜀書社, vol. 9, 1994.Zhouyi Cantongqi Tongzhenyi 周易參同契通真義 [True Meaning of the Zhouyi Cantong qi]. In Siku Quanshu四庫全書 [Photographic Reprint of the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries]. Taipei: Taiwan Commercial Press 臺灣商務印書館. vol. 1058.Second Sources

- Chen, Enlin 陳恩林, and Shouxin Guo 郭守信. 1998. Guanyu Zhouyi “Dayan zhi Shu” de Wenti 關於《周易》 “大衍之數”的問題 [On the Issue of the “Dayan Zhi Shu” (Great Expansion Number) in The Zhouyi]. Zhongguo Zhexueshi 中國哲學史 3: 42–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jiujin 陈久金. 2013. Zhonguo Gudai Tianwenxuejia 中國古代天文學家 [Ancient Chinese Astronomers]. Beijing: China Science and Technology Press 中國科學技術出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Zhie 陳植鍔. 2019. Beisong Wenhuashi Shulun 北宋文化史述論 [A Critical Survey of the Cultural History of the Northern Song Dynasty]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Dawei 傅大为. 1988. Lun Zhoubi Yanjiuchuantong de Lishifazhan yu Zhuanzhe 論《周髀》研究傳統的歷史發展與轉折 [On the Historical Development and Turning Points of the Scholarly Research Tradition of the Zhoubi Suanjing]. Qinghua Xuebao 清華學報 1: 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gai, Jianmin 盖建民. 2013. Daojiao Jindanpai Nanzong Kaolun——Daopai, Lishi, Wenxian yu Sixiang Zonghe Yanjiu 道教金丹派南宗考論——道派、歷史、文獻與思想綜合研究 [A Study on the Southern Lineage of the Golden Elixir: Its Schools, History, Documents and Thoughts]. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press 社會科學文獻出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Zhaoguang 葛兆光. 2008. Zhongguo Jingdian Shizhong 中國經典十種 [Ten Chinese Classics]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- He, Jianming 何建明. 2011. Chen Zhixu Xue’an 陳致虛學案 [Scholarly Record of Chen Zhixu]. Jinan: Qilu Publishing House 齊魯書社. [Google Scholar]

- He, Xin 何欣. 2025. Visual Alchemy: Alchemical Yijing Diagrams 丹道易圖 in the Illustrated Commentary on the Wuzhen Pian Based on the Zhouyi 周易悟真篇圖注. Religions 16: 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, Wm Clarke. 2008. Spreading the Dao, Managing Mastership, and Performing Salvation: The Life and Alchemical Teachings of Chen Zhixu. Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Sheng 姜生, and Weixia Tang 湯偉俠, eds. 2002. Zhongguo Daojiao Kexue Jishu Shi: Hanwei Liangjin Juan 中國道教科學技術史: 漢魏兩晉卷 [History of Science and Technology in Chinese Taoism: Volume on the Han, Wei, and Two Jin Dynasties]. Beijing: Science Press 科學出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, Livia. 2020. The Zhong-Lü System of Internal Alchemy. St. Petersburg: Three Pines Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Linghong 孔令宏, and Songtao Han 韓松濤. 2011. Jiangxi Daojiao Shi 江西道教史 [History of Taoism in Jiangxi]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Pregadio, Fabrizio. 2009. Awakening to Reality: The Regulated Verses of the Wuzhen Pian, a Taoist Classic of Internal Alchemy. Mountain View: Golden Elixir Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pregadio, Fabrizio. 2012. The Seal of the Unity of the Three: A Study and Translation of the Cantong qi, the Source of the Taoist Way of the Golden Elixir. Mountain View: Golden Elixir Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sivin, Nathan. 1978. On the Word “Taoist” as a Source of Perplexity. With Special Reference to the Relations of Science and Religion in Traditional China. History of Religions 17: 303–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Zhan 苏湛. 2016. Shiyi Shiji Zhongguo de Kexue, Jishu yu Shehui 十一世紀中國的科學, 技術與社會 [Science, Technology, and Society in China in the 11th Century]. Beijing: Science Press 科學出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Weijie 孫偉傑. 2022. Dongjin zhi Songyuan Daojiao “Sanshiliutian Shuo” de Chansheng yu Cenglei 東晉至宋元道教 ”三十六天說” 的產生與層累 [The Emergence and Stratified Accumulation of the “Thirty-Six Heavens Theory” in Taoism from the Eastern Jin to the Song and Yuan Dynasties]. Zongjiaoxue Yanjiu 宗教学研究 2: 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Volkov, Alexci. 2004. Scientijfic Knowledge in Taoist Context: Chen Zhixu’s Commentary on the Scripture of Salvation. In Religion and Chinese Society; Vol. 2: Taoism and Local Religion in Modern China. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, pp. 519–52. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Zilu 楊子路, and Yuhui Yang 楊玉輝. 2014. Nansong zhi Yuandai Nanfang Daojiao yu Zhongguo Chuantong Shuxe Guanxi Yanjiu 南宋至元代南方道教與中國傳統數學關係研究 [Research on the Relationship of Daoism and Chinese Traditional Mathematics from Southern Song to Yuan Dynasty]. Ziran Bianzhengfa Tongxun 自然辯證法通訊 8: 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Chuanhui 曾传辉. 2004. Yuandai Cantonxue: Yi Yu Yan, Chen Zhixu Weili 元代參同學:以俞琰、陳致虛為例 [Cantong Studies in the Yuan Dynasty: Taking Yu Yan and Chen Zhixu as Examples]. Beijing: Religious Culture Press 宗教文化出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Hongbin 張洪彬. 2021. Qumei: Tianrenganying, Jingdaikexue yu Wanqing Yuzhouguannian de Shanbian 祛魅: 天人感應, 近代科學與晚清宇宙觀念的嬗變 [Disenchantment: Heaven-Mankind Interaction, Modern Science and the Transmutation of Cosmology in Late Qing Dynasty]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House 上海古籍出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Weiwen 章偉文. 2007. Hetu Luoshu de Daojiao Wenhua Neihan 河圖洛書的道教文化內涵 [The Taoist Cultural Connotations of Hetu and Luoshu]. Zhongguo Zongjiao 中國宗教, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Weiwen 章偉文. 2017. Zhouyi Cantong qi “Tianwen” Jiqi yu Dandaolilun zhi Guanshe 《周易參同契》 “天文”及其與丹道理論之關涉 [Astronomical Phenomena in the Zhouyi Cantong qi and Its Connection with the Theory of Alchemy]. Zhouyi Wenhua Yanjiu 周易文化研究. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press 社會科學文獻出版社, vol. 9, pp. 165–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Zehong 張澤洪. 2015. Yuanmingqing Shiqi Quanzhendao zai Xinan Diqu de Chuanbo 元明清時期全真道在西南地區的傳播 [The Spread of Quanzhen Taoism in Southwestern China in the Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties]. Wenshizhe 文史哲 5: 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Ye 周冶. 2007. Shangyangzi Chenzhixu Shengping ji Sixiang Yanjiu 上陽子陳致虛生平及思想研究 [Study on the Life and Thoughts of Shangyangzi (Chen Zhixu)]. Ph.D. dissertation, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mao, J.; Han, J.; Zhang, L. Astronomy and Chen Zhixu’s Neidan Theory. Religions 2025, 16, 1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121499

Mao J, Han J, Zhang L. Astronomy and Chen Zhixu’s Neidan Theory. Religions. 2025; 16(12):1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121499

Chicago/Turabian StyleMao, Junxin, Jishao Han, and Lujun Zhang. 2025. "Astronomy and Chen Zhixu’s Neidan Theory" Religions 16, no. 12: 1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121499

APA StyleMao, J., Han, J., & Zhang, L. (2025). Astronomy and Chen Zhixu’s Neidan Theory. Religions, 16(12), 1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121499