1. Introduction

Over the last decades many European cities have experienced new unexpected socio-cultural dynamics due to the coexistence of different forms of religious belongings.

Globalisation, the migration flows or, simply, the idea of a safe haven for those who dream of a new beginning, have developed new religious geographies and generated new urban spaces. Therefore, the redefinition of the urban space has become a challenging research topic for geographers of religions where “in an interconnected world, as it has never been […] religions move with the movement of people. Moving in the world, they change” (

Pace 2013, p. 65). Within this context of demographic, social and cultural heterogeneity, new urban religious landscapes have been characterised by the presence and the interaction of religious legacies, diverse traditions and emerging spirituality beliefs. This has led to a new socio-spatial configuration of contemporary cities, enhancing scholars to question the negotiation of cultural diversity and religious heritage as well as to foster a new transdisciplinary analysis of religious places (

Bossi et al. 2024).

This article originates from the hypothesis that the presence of a community of Islamic faith is fostering a social change in the Roman suburb of Centocelle.

This space is located in the Eastern quadrant of the capital and seems to fully embody the conception that “after the long persistence of the anti-space legacy of philosophies of history modelled on the primacy of time, space seems to take its revenge, placing itself as a condition of possibility and constitutive factor of our action and of our concrete being-in-the-world” (

Marramao 2013, p. 31). Centocelle is indeed a neighbourhood that, for a series of reasons related to migration and globalisation, reminds us of the thought of the philosopher Marramao when he describes the

spatial turning point as “the only key to access to the ironic challenge of globalisation: at the time that the “death of distance” is determined, geography acquires a new strategic importance which goes far beyond its traditional disciplinary boundaries” (

Marramao 2013, p. 33).

The article’s main aim is to investigate how the influence of the presence of the Muslim community has shaped the district of Centocelle and how the development of the Islamic religion has, in turn, been influenced by the social environment, as it depends on it.

Amidst the vast recent reflections dealing with urban religion and the growing interest in related evolving conceptualisations, the present article proposes research that has been enhanced by the following perspectives.

First, according to the definition of urban religion of the anthropologist Stefan Lanz (

Lanz 2014), the present article suggests an interpretation of the urban space as the result of a cultural, symbolic and social stratification generated by both secular and religious experiences, following reflections by Becci, Burchardt and Giorda on religious diversity (

Becci et al. 2017) which led them to demonstrate how religious diversity is strictly linked with the urban space and how it shapes it. Hence, the three scholars have developed a new heuristic paradigm which seeks to explain the reciprocal intersections between urban space and different religions. Namely, the authors identify three types of spatial strategies, or

place keeping, making and seeking as power embodiment of the local religious communities in response to urban geography changes.

Place keeping refers to the major religions which have been shaping the urban space for centuries: this perspective deals with the recognition of symbols, visibility as well as social significance.

Place making indicates the struggles of a new religion/new religions to claim space—aimed at material appropriation and symbolic perception—and to establish relationships with the local actors, thus revealing its own identity and communicating its values. Lastly,

place seeking is related to new forms of spiritualities looking for new configurations of space in the fields of wellness, wellbeing or meditation.

This paper identifies and analyses the significance of place keeping as a categorical link to the major religion which symbolises the neighbourhood itself—the Catholic Church—questioning whether it has survived or has been overwhelmed by the place making of a new faith that is spreading across the public place and gaining popular relevance. In this context the ethnographic research conducted in Centocelle explores the relationships between the Muslim minority and the predominant Catholic Church and other religions but does not take into consideration an inquiry into the place seeking. It would be challenging and desirable in the near future to discuss new forms of spiritualities that trigger a rethinking of new spaces and common fields of action.

Second, within the so-called

urban studies, the reference goes to the text

Urban Religion (

Rüpke 2020) by the German scholar Jörg Rüpke, who proposes a heuristic application of the concept of religion as a spatial practice. His essay moves from the identification of an

urbanising religion opposed to an

urbanised religion focusing on the conviction that changes, relationships, and conflicts analysed through a cross-cultural approach provide a keynote to identify and understand the religious dynamics within urban spaces. Influenced by Lanz’s definition of urban religion “as a specific element of urbanisation and urban everyday life … intertwined with … urban lifestyles and imaginaries, infrastructure and materialities, cultures, politics and economies, forms of living and working, community formation, festivals and celebrations” (

Lanz 2014, p. 25), Rüpke’s perspective is linked to two aspects of the

urbanising religion, or the fact that it plays, on the one hand, an active role within the promotion of new spaces, new human settlements, and new economies, and, on the other hand, it is also a passive actor which is influenced by the urban society and its challenges.

Third, referring to the reflection on the cultural and religious heritage issue (

Tsivolas 2014) related to the fieldwork which has been carried out in Centocelle, this article raises the question of the contradiction of Al Huda visibility and invisibility in the urban space, which refers to the topic of collective memory.

Therefore, it seems clear that the analytical tools provided by the geography of religions are relevant to the analysis of a reality where different religious communities coexist in order to explain and legitimise their concrete and symbolic presence through a transformation of the architectural landscape, the redefinition of pre-existing power relations, and the constitution of new ideologies and new identities.

The significance of an interdisciplinary holistic approach (

Annali di Studi Religiosi 23 2024) founded on the co-existence of a multifocal analysis which proposes the reciprocal influence of history of religions, geography of religions, sociology, anthropology and social sciences has facilitated the development of a stimulating fieldwork in Centocelle. Albeit grounded in religious dynamics, the present research has conducted a layered broader investigation within manifold relationships and interactions in the social, political, educational and cultural dimensions of development.

In this regard, the geography of religions builds bridges with a new

geography of encounters (

Burchardt and Giorda 2021) that dialogues with different sciences and rises to an active role of anthropisation of the surrounding environment, which moves across multiple categorical dimensions and seeks the answer to the following questions.

Given the undeniable fact of religious diversity in the urban space—and more specifically in the neighbourhood of Centocelle—questions arise about whether religious minorities are allowed to function within public space, and if so, how? Why has a specific urban geographical area become a meeting place between religious and cultural pluralities? What were the initial dynamics and the tangible effects of this redefinition of the shared urban space, following the clash between the Muslim religious minority and the dominant Catholic religion? Was there a key figure that favoured the integration process? What are the current outcomes of the negotiation between the hierarchies of power that have met and clashed? Have there been any social and economic effects? Are there any tangible signs of urban change?

To better understand the issue of space, which is directly related to the speed of the social, cultural and religious change that characterises our historical period, the concept of the

spatial turn over the past few decades—and its related sociological approaches (

Kong 2001,

2010;

Knott 2005,

2010a,

2010b)—together with the

visual turn (

Brighenti 2010), the

material turn (

Meyer et al. 2010) and the

infrastructural turn (

Kirby 2024) have been extremely and increasingly fruitful in distinguishing the multiple layers of influences that shape the urban space, focusing on the significance of the religious fact as a social manifestation which shapes relationships, behaviours and structures.

Accordingly, the framework of the

location of religion has also represented a methodological compass, as it is based on the conception that “space in not something other than or further to the physical, mental and social dimensions that constitute it. It is their dynamic summation” (

Knott 2010b, p. 160).

Following the above-mentioned theoretical frame of reference, this article proposes the outcome of a fieldwork study carried from February 2022 to March 2023 focusing on the multiplicity of contents that the urban space in Centocelle evokes. Conceived as a bottom-up project, it has been developed through key ideas and concepts which originate from the hypothesis that the urban religion itself reveals that “religion is not about representation, but (re)presentation. It does not speak of things, but “from things”” (

Latour 2005, p. 29).

It is worth noting that this approach focuses on a multidimensional and multilayered space, or a mixture of an anthropological space where individuals are in relation with the surrounding world, a community space where groups meet, interact, collide and merge, a sociological space made of social representations and constructions, stereotypes and prejudices. Additionally, we must also consider the historical space representing the physical, concrete and tangible spaces which undergo the passing of time and the space of memory and legacy.

The premises above have encouraged me to rely on a type of analysis that involves a contamination between the historical approach—scrutinising the diachronic evolution of events—and the synchronic analysis, which investigates and evaluates the interacting phenomena, portraying them as a screenshot. The production of a socio-religious narrative around the Islamic Cultural Association Al Huda requires, in fact, an attentive eye able to grasp the Muslim and Christian cultural identities in the shared space and, simultaneously, to identify and interpret the most relevant historical events, placing them in a timeline. “Religions are self-aware about history, constructing their identity within a series of repetitive ritual performances. On the other hand, historical perspectives can inform the study of the geographies of religion” (

Brace et al. 2006, p. 31).

The production of knowledge of this research project is based on a methodological approach that draws on ethnography, or its reflexive postmodern interpretation (

Colombo 2001) and relies on qualitative techniques. The research has been developed in two phases consisting of a first exploratory phase made of document analysis (statistical resources and evaluations, field surveys published on the institutional websites of the Municipality of Rome Metropolitan City, ISTAT (Italian Nationale Institute of Statistics), the ISMU (Initiatives and Studies on Multiethicity) Foundation, CESNUR (Center for Studies on New Religions), association’s bylaws and articles of the local press, social media, press releases, leaflets, statutes). Then a second phase follows, characterised by in-depth investigation through 30 semi-structured interviews with religious leaders, worshippers, schoolteachers and representatives of the local administrations (municipal policemen and medical workers) and several informal conversations with residents and shopkeepers.

The interviews sought to involve the widest possible range of participants in terms of age, cultural background and gender balance. With the support of the religious authorities of the Al Huda prayer centre, Muslim adults from diverse countries of origin and migratory trajectories were selected, in order to capture a plurality of perspectives and experiences. The questions addressed their family background, challenges faced, current living conditions (housing, employment and children’s education), and relations within the Muslim community connected to the centre. Particular attention was also given to the interactions between Muslims and various actors in Centocelle, spanning from formal settings (schools, public administration, teachers and law enforcement) to informal encounters in everyday public life (neighbours, shopkeepers and property owners).

This study seeks to illuminate a distinctive feature of ethnographic inquiry: its attentiveness to otherness and cultural difference. At the same time, it aims to underscore the potential of dialogue and encounters as avenues for appreciating diversity and constructing an authentic representation of social reality—one that embraces complexity and asymmetry, and is shaped by a multiplicity of perspectives, voices, emotions and lived experiences.

2. The Neighbourhood of Centocelle

According to the evaluations from the Statistical Office of Rome Capital published in the Statistical Yearbook 2023, the urban area 7a called Centocelle is an area with a very high population density of 16,941.6 inhabitants per square kilometre, with a total of 52,073 inhabitants—18.2% of which are registered as foreign citizens—across an area of 3.07 square kilometres.

The data concerning the number of children born to a foreign mother—equal to 426 units—and the fertility rate of foreign mothers recorded in 2021, the Fifth-Town Hall, or Centocelle, is in second place after the adjacent Sixth Town Hall. Equally significant are the geographical origins of the foreign population of Centocelle: the statistical surveys show the highest number of men and women (21,069 and 8481) of Asian origin (mostly from Bangladesh) compared to all the other municipalities of the capital, followed by a very high concentration of citizens arriving from the African states of the Maghreb (especially Egypt and Morocco) and from countries, both EU and non-EU, of Eastern Europe (especially Romania, Ukraine and Albania).

In Via dei Frassini 4, a white gate leads to the premises, below the street level of a brick-faced building, of the Islamic Cultural Association Al Huda (See

Figure 1).

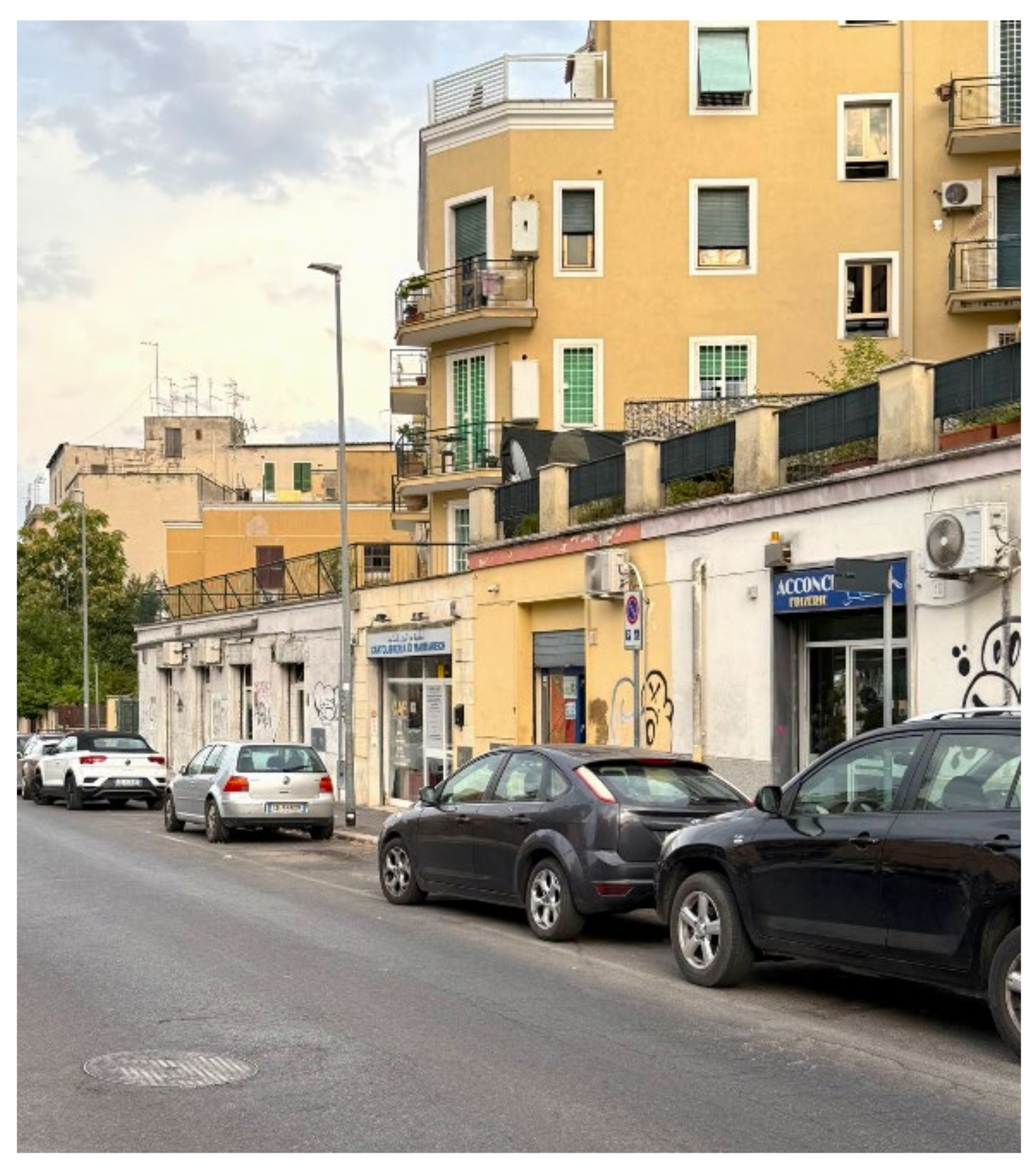

The long Via dei Frassini, which starts from Via dei Pioppi and leads to Piazzale delle Gardenie, seems to represent all the particularities of Centocelle heterogeneity, from the socio-cultural point of view to the architectural heritage. Walking along Via dei Frassini one can see the remains of the ancient Alexandrian aqueduct (See

Figure 2)—which today serves as a traffic divider, then an area where there are many Muslim traders, mostly of Arab and Bengali origin, who run grocery stores, barbershops, markets and bookshops; until one reaches a square, Piazzale delle Gardenie, a new major subway hub and a popular meeting point of Eastern’s Rome’s nightlife—which attracts young people and teenagers in particular. Until a few decades ago this large square (Piazzale delle Gardenie) was just a large unused space in front of the Catholic Church of the Holy Family of Nazareth. There are also recreational activities here, with its oratory, its playgrounds and its Centocelle squares, inhabited mostly by middle-class Roman clerks and shopkeepers.

Today’s Centocelle public space is a kaleidoscope of ethnicities, languages, dialects and cultures. Therefore, this study will trace the key historical moments that have shaped Centocelle into a diverse community. Accordingly, the analysis will focus on the principal historical junctures that have contributed to the community’s formation, with particular attention to the sociocultural processes that have facilitated its ongoing transformation.

The urban development of Centocelle began in the post First World War period, along the axis of the Casilina consular road, starting from a nucleus of houses near the intersection of Via Tor de’ Schiavi and Via Casilina (now known as “Old Centocelle”) where families of workers, farmers, craftsmen and tram drivers had been living in modest dwellings, while small traders inhabited more comfortable houses. Following the Second World War, Centocelle underwent significant urban expansion. Approximately half of the residential units constructed between 1946 and 1970 were occupied by Italian households originating from the surrounding Roman countryside and southern regions of Italy. Therefore, a new popular—but also distinctive— neighbourhood has developed: between the Seventies and Nineties, many shops and craft businesses flourished—starting with the well-known local market of Piazza dei Mirti—and new educational institutions and social services for citizens opened. Today, Centocelle’s uniqueness lies in its urban architectural structure: far from being a commuter area made of dormitory blocks of flats, it is more like a village where smaller buildings stand along the narrow city streets (See

Figure 3).

Historically well-connected through major tram lines, located in close proximity to Rome’s historic city centre, and characterised by a supply of affordable rental housing, Centocelle emerged between the late 1990s and early 2000s as a significant destination for migrant populations—particularly from Maghreb countries and Southeast Asia. Data collected in 2006 on foreign residents in Rome underscore this trend. Within a single year, the neighbourhood—then part of the Seventh Town Hall—registered the highest increase in foreign presence across the capital between 1997 and 2006, reaching 7.2% and marking a growth rate of +244% (

Mosaico Statistico 3 2007). Obviously, the foreign presence in Rome is linked to the labour supply, as shown by the greater proportion of the population that falls precisely in the workforce age. In fact, those aged between 30 and 49 represent 38.4% of the total, while the total foreign population of working age people (15–64) represents 79.6% of the total number of non-Italian citizens. Also significant is the number of children up to 9 years: about 10% of the total (

Mosaico Statistico 3 2007).

These data and numbers have been confirmed by the authentic feedback of the people interviewed whose experiences and stories reveal the real upheaval of the social, cultural and economic sphere in Centocelle.

The activity of the Islamic Cultural Association Al Huda began in 1994, and its work is not only linked to a specifically religious function. Thus, the so-called mosque offers a precious support for all Muslims who need help: from Italian language courses to assistance for administrative procedures, from an emergency shelter to a “placement agency”. Within this context, during those years in the local market of Piazza dei Mirti one could find spices and fruits of other latitudes and other cuisines—much more easily than in other districts of the capital; pizza makers of Egyptian origin imposed themselves on Italian ones; the first kebabs and falafel shops opened. Kindergartens and primary schools welcomed, with many difficulties, Muslim boys and girls—as one of the major consequences of the phenomenon of family reunification—who, in a short time, would become the point of reference of their parents, supporting them and providing valuable help especially in the linguistic sphere.

It follows, therefore, that the community of Centocelle has coped with a series of challenges, from school integration to religious recognition, from global citizenship to social visibility. Within this framework the presence of the Islamic Cultural Association Al Huda has played a relevant role towards the promotion of an effective interreligious, intracultural and intercultural dialogue.

The imam Mohamed Ben Mohamed, who has been holding this office since 1998—but has been an active collaborator since the Islamic Cultural Association Al Huda settled in Centocelle—is firmly convinced that “the biggest success of the Association lies in the fact that the community in Centocelle really trusts us”. It is conceivable that thanks to his openness to others and his disposition to dialogue, the imam paved the way to all other Muslims, teaching them to adopt a positive attitude and to show empathy from the very beginning. Endowed with a kind spontaneity, he amazes people with his simplicity and harmony and, little by little, his reputation spread in the social sphere in Centocelle, sometimes as a promoter of religious and cultural initiatives, other times as facilitator of administrative or political relations.

3. Centocelle Urban Space: Between Space Keeping and Space Making

The above premises have without a doubt allowed Centocelle’s people to welcome and accept the Muslim community with respect, subsequently becoming an essential part of the society: “I can’t imagine my class without Munia and Asif. They give an added value to the group…that is difficult to express in words” a teacher says.

The neighbourhood of Centocelle is undoubtedly a place that, according to the latest historical and demographic alterations and related to prominent socio-cultural changes, has been experiencing a complex process of redefinition of the urban and the human space. A spatial reshape caused by a new morphology within the economic life (from markets to home rentals), a new scenario of the public life in shared spaces (from schools to administrative offices, from religious places to public parks) and new social relationships among Muslims and Centocelle’s citizens.

This contribution argues that a pivotal time in Centocelle’s historical narrative has started since the Eighties and the Nineties.

A lukewarm attempt at gentrification—far different from those undergone in more bourgeois Roman areas—began in the Eighties and went through a radical upheaval in the Nineties. Having first become a convenient destination for first-generation foreign immigrants—mostly from countries of Islamic faith—and then having been chosen as a place for family reunifications, Centocelle’s public space has changed in a substantial way.

The previously homogeneous demographic composition of Centocelle—characterised by a predominantly Christian population, linguistic uniformity, and cultural homogeneity—has transformed into a vibrant and heterogeneous social landscape. This new configuration encompasses a multiplicity of religious affiliations, as well as diverse ethnic, cultural, and linguistic groups, marking a level of pluralism unprecedented in the neighbourhood’s history.

Therefore, I argue that the Islamic Cultural Association Al Huda has fostered the knowledge and the encounter between Centocelle’s community and the Islamic otherness, in a way that the image of the Muslims has been transmitted without frills, clear and true, through an effective network of relationships built in several fields.

From this perspective, Al Huda centre prayer represents an example of place making as an urban space for religious aims (being first a prayer place) and the hub for bottom-up evidence of a new shared religious place where new social identities have been moulding.

The so-called mosque in Via dei Frassini, which calls and gathers Muslims from Centocelle and all over Lazio, has demonstrated its power in two ways. First, it has the ability to establish relations with other religious actors within the area—from those consolidated that embody the place keeping, or the Catholic parishes of Saint Bernardo from Chiaravalle, Saint Felice from Cantalice and Saint Ireneo, to the newer communities around the Pentecostal Evangelical Christian Church in Via del Grano and Via della Bellavilla—and, second, it manages its authoritativeness in leading a minor community, forging it and changing it according to the local needs—and those of its inhabitants.

What began in the mid-1990s as a small grocery store near the Islamic prayer centre—offering food and spices from the Maghreb and Asia—has gradually evolved into a dynamic commercial micro-enclave. Over time, the area witnessed the emergence of additional migrant-owned businesses, including a butcher shop, a bookstore, and a barbershop. Today, the streets surrounding Via dei Frassini are marked by a strong ethnic commercial presence, evoking the sensory and spatial characteristics of a Muslim medina. The original grocery store has become a key site of social interaction and cultural visibility, commonly referred to as the ‘Arabic Market.’ This transformation reflects broader processes of spatial appropriation and commercial multiculturalism, wherein migrant communities reshape the urban landscape through place-making and the consolidation of ethnic economies. Today most of the businesses settled along Via dei Frassini, Via dei Pioppi and Via degli Aceri are run by Muslim traders, mostly Arabic and Bengali, who exploited the presence of the so-called mosque of Centocelle to invest economically, to consolidate their identity presence, to make their businesses flourish and to show their social power. At the same time many reunited families began to rent flats, generating a massive settlement of the Muslim community in humble buildings of that area, while the more elegant ones have remained in the ownership of families of Italian origin.

Another important signfier of place shaping as place making is undoubtedly the prayer centre’s activities and relationships within the educational sphere. The Arabic language school (which provides an educational programme divided into 6 levels) organised by the Islamic Cultural Association Al Huda in collaboration with the public school Istituto Comprensivo San Benedetto in via dei Sesami 20 welcomes students aged between 5 and 15 and represents a milestone for the young Muslims brought up in Centocelle. In addition to this, Al Huda prayer centre has been cooperating for years with the above-mentioned school institute: it has been supporting many proposals of activities, exhibitions and projects also within the curricular timetable, focusing on integration challenges and issues. It has also joined the Project “Scuole Aperte il Pomeriggio” (Open schools in the Afternoon), in collaboration with Roma Scuola Aperta of the Municipality of Rome, an educational workshop which proposes cultural events (concerts, film screenings and meetings) for the educational community and the pupils’ families. These activities generally take place outside school hours, thus representing a sociologically relevant opportunity for meetings and exchanges. Therefore, it is more than an important welcome point for Muslim families but rather an authentic example of social integration and reciprocal interaction through effective strategies and activities that foster a challenging intercultural and interreligious dialogue. Moreover, the prayer centre is often a destination visited by university student who, guided by their professors, are invited to listen to the imam explanations and to stroll around via dei Frassini.

Other important initiatives which saw the imam and his collaborators come to the forefront of civil society are worth mentioning. First, the open day of 21 April that celebrates the “Day of interreligious dialogue”, open to evangelical friends, Catholics and Buddhists, sought to gather them to discuss the religious issues of the time. Second, the celebration of the “Brotherhood Iftar” which marks the end of the daily fast of Ramadan through the sharing of food in a community of Catholic and Muslim diners, heterogeneous in ethnicity, age, eating habits and religious faith but cohesive in the sharing of a physical, spiritual and social space. Third, the participation to ceremonies, festivities, inaugurations and national conferences which involve representatives of the political and administrative life within the local sphere, the municipality area or the national context.

Despite certain instances of perceived inconvenience—most notably related to Friday prayers prior to 2010, when Imam Mohamed Ben Mohamed introduced a double prayer shift to accommodate worshippers—large numbers of Muslims who were unable to access the prayer space at Via dei Frassini 4 would pray outside, laying their carpets near the entrance. While this practice occasionally caused discomfort among passers-by and local residents, the broader Centocelle community has not exhibited significant hostility or resentment toward the Islamic community. Rather, on a few occasions, they pointed to the lack of an adequate space for the prayer and the need to claim one, demonstrating a sense of community coexistence, mutual respect and peaceful sharing of the urban space.

The Islamic Cultural Association Al Huda has arguably enhanced the process of getting to know each other—the people living and working in Centocelle and the Muslim community; progress has been made in many fields even though there have been hard times. Every one of us remembers the Twin Towers’ attack and the following years. The Muslims in Centocelle got through those challenging times thanks to the fact that they are not just a known local minority community but also part of a broader one within the boundaries of Centocelle. During those years the imam had accepted to be interviewed by many journalists, and he had never ceased to emphasise their distance from the Islamic radicalism. And the community of Centocelle knew that.

Today, twenty-year-old Muslims claim that for them—as for their peers of other religious faiths—September 11th represents “the beginning of the Islamophobic society they have to cope with…it’s different from our parents or grandparents’ experience, for them there is an Islamic society before the Twin Towers’ attack and another one after it…”. It is not difficult to imagine the psychological burden that could also be associated with fear, shame, anger or anxiety. Thanks to the support of educational institutions and the Islamic Cultural Association, young Muslims now feel accepted and well-integrated, to confirm that something good has been done in the eastern outskirts of Rome. And the activity of the so-called mosque of Centocelle continues on this path: in recent years, the imam and his collaborators have focussed their attention on young Muslims—who in many cases were born and raised in Italy and entangled with a noteworthy challenge or according to the words of the sociologist Roberta Ricucci “a difficult balancing act: respect the expectations of the Muslims and not disappoint those of the Italian society” (

Ricucci 2021, p. 35).

Referring to the spatial analysis and considering Becci, Burchardt and Giorda’s heuristic paradigm, the latest evidence seems to be as follows.

While the place making category, which stands out for its dynamism, its openness and its conviviality, is moving forward, its counterpart, or the place keeping category is holding on. Through a deep analysis, each initiative or opportunity for sharing, dialogue and charity can be read as an example of place making—from the Islamic angle view—for they establish relationships within the urban space to show its presence and identity, or to create new spaces of interaction and representation. On the other hand, these same initiatives represent, through the category of place keeping, the perspective of the ancestral symbolic essence of the Catholic Church which has understood that it must backtrack from the new and, consequently, open to the other by conveying a message of tolerance and modernity.

4. The Muslims in Centocelle

Regarding the fieldwork carried out in Centocelle, this article draws attention to the importance and role of collective memory (

Halbwachs 1941) that has been a red thread of many interviews and has characterised its explicit relevance, both in public and private spaces. It is a memory that brings the Muslims, the residents and the workers in Centocelle back to the migratory phenomenon during the Nineties, which is made up of noteworthy microstories (

Trivellato 2023) and testimonies. Each microstory assumes an intimate connotation as a private re-collection, thus becoming a story of public remembrance as a shared experience. Within this frame the collective memory, we witnesses the dynamic flow of a cultural heritage that has its roots in religious issues and pervades the everyday life of an urban space that has been shaping new identities and new representations, thus revealing its social dimension. Accordingly, what has emerged from the emic and the ethic perspective of the ethnographic research is the identification of a double force within the collective memory: when it turns to the past, it is synonymous for a sense of belonging, roots, origin, motherland, tradition and transmission, and when it focuses on the present it shows the relevance of affective ties and community shared issues. Concurrently, a new type of memory is called to attention, or the collective oral memory (

Halbwachs 1992). It is inextricably intertwined with communication and social interaction and is characterised by institutional awareness, common values and identity formation. Moreover, it draws its energy to manifest an active spirit demanding for assistance, civic participation and social engagement.

It is worth noting that the role of religion has been a relevant role in the shaping of a cultural heritage. For the Muslim community around the Al Huda Islamic prayer centre, religion is, hence, to be seen as an adaptive and resilient force that emerges from a bottom-up perspective, thus revealing its power in fostering a vibrant socio-cultural innovation and a responsive active participation, contributing to the shaping of a new Muslim identity made up currently of many Italian-born Muslims.

The interviews conducted during the fieldwork revealed the presence of an immigrant community that has developed self-help networks to navigate the initial challenges of integration into a new country. Upon their arrival in Rome and subsequent settlement in the Centocelle neighbourhood, these individuals sought a place to pray—within a national context where Islam has yet to be formally recognised at the institutional level—and a space where they could feel a sense of belonging.

The Al Huda Islamic prayer centre emerged as the first associational structure to bring together early immigrants, playing a crucial role in responding to their spiritual and social needs. Commonly referred to as the “mosque” of Centocelle, it has served as a focal point for a self-organised community, facilitating mutual support in confronting the early difficulties of integration.

Within this context the Muslim community has been struggling to activate new negotiations of social belonging, thus fostering new narratives of religious heritage. Even though they have not been able to build their own mosque (following the architectural criteria of a traditional one due to the normative Italian framework), they have been enhancing their social recognition through an activation of social cross-generational practices that have been precisely promoted by the Islamic Cultural Association Al Huda.

Thanks to a far-sighted vision of the imam Mohammed Ben Mohammed who has been supporting the younger generations of Muslims for decades, the so-called mosque of Centocelle has been representing a landmark in their life. It has been, namely, the first meeting point of the Roman branch of the Islamic Association “Giovani Musulmani d’Italia” (GMI) and the starting point for an exploration of the public space. Educational institutions have opened their doors to their weekly meetings; the Fifth Municipality of Rome and the police headquarters have granted permission to open-air prayer sessions; Iftar celebrations and religious services have being hold since 2015 in the urban space in Centocelle (See

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

The neighbourhood, for its part, has encompassed new community relationships and welcomed proper intercultural projects, thus fostering the path toward interreligious dialogue.

5. Discussion

In the field of the religious heritage, the case of the neighbourhood of Centocelle allows me to draw the following reflections.

First, viewing the shared public space, my considerations deal within the community narrative of Muslim empowerment. The narration of the clash—or the encounter—between a Catholic legacy and a community of Muslim newcomers is an authentic example of how a combination of community leadership and empowerment has played an effective social role: on the one hand, the presence of a shared leadership (the Islamic Cultural Association Al Huda) has stimulated a system of mutual support and a positive culture of growth and, on the other hand, an exemplary bond of community cohesion has fostered “the ability to negotiate one’s rights in the public space” (

Ambrosini et al. 2022).

Second, my thoughts go to the near future and new questions arise, as follows.

If today we can speak of a peaceful religious coexistence in Centocelle, the Islamic Cultural Association being its hallmark in the process of acceptance and integration within the cultural religious and linguistic diversity, what will be the social scenario of Centocelle over the next few years? Will next generations mix? Will young Catholics convert to Islam or young Muslims convert to Catholicism? Will the current new generation Catholics re-discover their religiosity, or will the new generation Muslims gradually reduce their religious practice?

If this article’s main objective is to highlight—through the paradigm of the space strategies developed by Becci, Burchardt and Giorda—how the presence of the Islamic faith community has shaped the neighbourhood of Centocelle and how, on the other hand, the development of the Muslim community has been in turn influenced by the surrounding urban space, it is evident that the above-described narrative talks about incontrovertible facts and experiences.

In the near future, it would be valuable to undertake top-down research aimed at examining whether a forum for dialogue exists within institutional agendas, or at the very least, to encourage the initiation of such a debate. Equally important would be an analytical focus on the presence of diverse religious expressions within the urban fabric of Centocelle. Notably, emerging forms of intimate and spiritualistic practices are gaining traction among residents. This phenomenon could be critically assessed through the conceptual framework of ‘place-seeking strategies,’ offering insights into how individuals and groups negotiate spiritual belonging in contemporary urban contexts.

If at an architectural level there is not a minaret in the sky above Centocelle as an exogenous and visible sign of Islam, at an identity level the presence of the community is thriving, it is part of the social context, and it is working towards an ever more fervent and active involvement in the community life of the neighbourhood with the support of the Islamic Cultural Association Al Huda.

Currently Al Huda prayer centre

is a “multifunctional reality” (

Mezzetti 2022) not recognised at the institutional level and ambiguous from the semantic point of view. Focusing on the role of religious minorities in shaping cultural memories and heritage within urban contexts, the dichotomy that Al Huda carries with it is clear. On the one hand there is an invisible, informal prayer centre that is not recognised from a regulatory point of view; on the other hand, it is evident how all the surrounding space evokes Islam in the public sphere. Even though there is not a tangible presence of a mosque as a sign of an artistic heritage, Al Huda represents a cultural and religious example of intangible heritage for two reasons. First, this prayer centre is a social gathering place of Muslims, which reveals a special transnational legacy with the countries of origin and recalls a shared collective memory. Second, the clash, or the encounter, with the Catholic church and other religious faiths witnesses a process of plural interconnection that highlights an interreligious dialogue whilst fostering an in-depth reflection on the recognition of minority religions.

The social space of Centocelle is shaped by the presence of a dominant religious majority and an Islamic minority, two distinct groups that coexist and are interconnected through local forms of community organisation.

Centocelle constitutes a shared social space where relationships are forged, social bonds are cultivated, identities are expressed, and ongoing processes of negotiation take place. At the same time, it is a geographically situated space that redefines both internal and external boundaries—boundaries that are deeply intertwined with the passage of time.