Abstract

Southeast Asia has historically been shaped by the Indian subcontinent, China and the Middle East, due to civilizational contact. For several centuries, current-day Indonesia and the Malay world experienced extended periods of Hinduization and Indianization. The once-thriving Hinduism/Buddhism-dominated culture gradually gave way to Islam when the area became Islamized. Indonesia now is believed to have the largest number of Muslims in the world. While the Islamic aspects of Indonesia are well-documented in recent scholarship, the country’s Hindu/Buddhist past remains significantly under-explored, especially as far as the linguistic and semiotic landscape is concerned. Conceptualizing linguistic/semiotic landscape as a polyphonic site and a ‘palimpsest’ that is often historically (re)written and constantly updated, this interdisciplinary study documents and reveals the concrete material traces of Hinduism/Indianness evidenced in Jakarta’s linguistic and semiotic landscape at different levels (e.g., various Sanskrit/Hinduism-related place names, slogans and mottos, portrayals of Vishnu, Garuda, Hanuman, Ganesha and depictions of scenes from Hindu epics Ramayana and Mahabharata). Aiming to explore how elements of Hinduism/Indianness may manifest in Indonesia in such cross-region linguistic and religious (re)contextualization across time and space, this study contributes to linguistic and semiotic landscape research, sociolinguistics, Indonesia and Malay studies, Hindu studies, religious studies, Southeast Asia studies and beyond:

1. Introduction

The historical contact between the Indian subcontinent and Indonesia and the Malay world (Ardika and Bellwood 1991; Ramstedt 2011) started well over a millennium ago. For several centuries, current-day Indonesia and the Malay world in general experienced an extended period of Hinduization (van der Kroef 1951) and Indianization (Groves 2023). However, rather than a unique experience, such intense religious, linguistic and cultural contact was part of a broader picture seen not just in the Malay world but also in Southeast Asia in general (Gu 2025a). That is, present-day Southeast Asia (e.g., Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Burma), sandwiched between the Sinic and Indic civilizations (Winichakul 1994), has been significantly influenced by China and the Indian subcontinent since historical times (Gu 2025a; Noobanjong 2023). In particular, Southeast Asia in general was at the receiving end of civilizations from the Indian subcontinent. Such multifaceted and deep-rooted impact (Jones and Phillips 1995; Noobanjong 2023) manifests in important areas such as religion, philosophy, language, place names, cuisine, architecture, culture, and folk traditions (cf. later section for the deep-rooted impact of the Indian subcontinent on Southeast Asia).

More specifically, in Indonesia and much of the Malay world, Hinduism and/or Buddhism was once dominant for several centuries. Hinduism initially came to Indonesia in the 1st century CE or so, via sailors, traders, priests and scholars hailing from the Indian subcontinent. As Hinduism was introduced to the new environment, it inevitably underwent various changes. As such, the kind of Hinduism practiced in Indonesia (and the Malay world in general) was a localized and (re)contextualized one that has over time combined Hinduism from India with local folk religions and traditions and some elements of Buddhism. Despite having been a major and dominant religion for centuries, Hinduism experienced significant decline and indeed almost disappeared in many/most parts of Indonesia as Islam, currently the dominant religion, was introduced to Indonesia and the Malay world from Muslim traders and preachers through various routes. As such, the once-thriving Hinduism/Buddhism-dominated culture gradually gave way to Islam when the area became Islamized.

After centuries of Islamization, Indonesia is for some time known as the largest Muslim country in the world (with largest number of Muslims). However, a small number of Hindus can still be found. Hinduism is currently practised by approximately 1.68% of all Indonesians and most Hindus live in Bali (in many ways, Bali is the last bastion of Hinduism in the country). In addition, Indonesia was also historically shaped by European colonial powers (e.g., the Dutch) and also migration from (Southern) China. Chinatowns (Gu 2026) can be found in places such as Jakarta (e.g., Glodok) and Surabaya (Kya-Kya Chinatown/Jalan Kembang Jepun). As a result of these historical forces, Bahasa Indonesia, essentially a variety of Malay and a lingua franca in multilingual and multicultural Indonesia, bears traces of various languages. These include Indian languages (e.g., Sanskrit), Arabic (e.g., ‘astaga’, ‘insyaallah’ and other Islam-related words and expressions), Dutch (e.g., ‘wastafel’ or ‘washbasin’), Chinese and especially Southern Chinese dialects (e.g., ‘siomay’ and ‘bakso’), Javanese, etc. In addition to Bahasa Indonesia as a unifying language, various local languages are spoken across Indonesia (e.g., Javanese, Minangkabau, Baliness, Sundanese, and Acehnese). More recently, against a backdrop of globalization, English is also vital, which is used in areas such as commerce, business, foreign diplomacy, and tourism.

Despite the country’s various historical, cultural and sociolinguistic influences, Islam arguably has exerted the most noticeable impact on the nation (approximately 87.06% of all Indonesians identify themselves as being Muslims). So far, in academia, much scholarship on Indonesia has to do with Islam (Ufen 2009; Rodríguez 2022; Afrianty 2012) from various socio-political, religious and cultural perspectives. Only few have touched upon Hinduism, which have largely focused on Bali (Lesmana and Tiliopoulos 2009; Wisarja and Sudarsana 2023). Notably, Islam has significant internal diversity in Indonesia. That is, different forms of Islam are practiced in different regions of Indonesia and even in Java Islam may manifest differently in different ethnic groups and in different local cultures. Also, in Indonesia, there exists a syncretic form of Islam known as ‘kebatinan’, which is an amalgam of Islam and a few other beliefs. Nevertheless, positioned as the largest Muslim country in the world, Indonesia overall arguably possesses a predominantly Islamic image and identity. To some extent, such an Islamic image seemingly conceals the actual diversity on the ground and the fact that Indonesia and the Malay world were under significant Hindu/Buddhist influences before the region’s mass Islamization. This highlights the crucial need to engage with the under-explored topic relating to the presence and legacy of Hinduism/Buddhism in the country. To this end, drawing on authentic photographic data, this interdisciplinary study aims to document and reveal concrete and material traces of Hinduism/Buddhism in Indonesia’s linguistic and semiotic landscape, and to highlight how elements of Hinduism/Buddhism may manifest and be (re)contextualized in Indonesia. Clearly, representing a witness to the changing socio-political, cultural and religious contexts, linguistic/semiotic landscape, conceptualized as a ‘palimpsest’ in the study, constitutes a particularly useful entry point into studying traces of Hinduism/Buddhism in Indonesia and the Malay world in general. Interdisciplinary in nature, this empirical study, from a unique linguistic and semiotic landscape perspective, promises to contribute to scholarship in linguistic and semiotic landscape, Hindu studies, Indonesian and Malay studies, Southeast Asia studies, intercultural communication, linguistic anthropology and sociolinguistics in general.

2. Hinduism, Buddhism and Hindu-Buddhist Syncretism: An Overview

The word ‘Hindu’, etymologically speaking, stems from the word ‘Sindhu’. Hinduism, as a religion or dharma, is originally from the Indian subcontinent. Hindus, or believers of Hinduism, now account for approximately 15% of the entire population of the world. This makes Hinduism the third largest religion globally, after Christianity and Islam. Hinduism is often believed to be amongst the oldest religions in the world (cf. Shattuck 1999), if not the oldest. Hinduism is not a monolith. Indeed, the expression ‘unity in diversity’ captures the Hindu religion. Hinduism might be understood as an umbrella term, which is used to describe a range of interrelated religious beliefs, practices, teachings and traditions. Despite having noticeable geographic differences (South India versus North India) and different sects and denominations (e.g., Shaivism and Vaishnavism), these seemingly distinct yet interrelated religious practices and traditions collectively are called Hinduism, which is united by a few core religious components.

Ramayana and Mahabharata, for example, are two major epics essential to Hinduism (Shattuck 1999). The Ramayana (or literally ‘Rama’s journey’) from ancient India tells the epic story about Rama (an avatar or incarnation of Vishnu), who rescues his wife Sita from Ravana (the king of Lanka) with the help of Hanuman and others. The Mahabharata, India’s longest epic, narrates the Kurukshetra War, telling the story of the war between the Pandavas and Kauravas. Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva, Parvati, Ganesha and Lakshmi are some major gods and goddesses in Hinduism. In addition, there are many other deities in Hinduism, who may have different manifestations and incarnations. Please see Doniger (2014), Flood (2020), McDaniel (2013), Lahiri and Bacus (2004) and Shattuck (1999) for more details and discussions about Hinduism.

Given the history of Hinduism, current-day India, Nepal and other parts of South Asia might be seen as the initial heartland of Hinduism. However, the historical and current influences of Hinduism are far beyond the Indian subcontinent (cf. Gu 2025a). Hinduism is now practiced in other parts of the world due to historical and current migration as well as various kinds of economic, religious and cultural exchanges. These regions with varying degrees of Hindu influences include East Asia (e.g., Hong Kong and Macau), Southeast Asia (e.g., Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar, Malaysia, Singapore, Bali in Indonesia), the Middle East (e.g., Hindu communities in the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, Oman and Saudi Arabia), Africa (e.g., Hindus in East African countries such as Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda and Hindus in South Africa), Europe (e.g., the United Kingdom), North America (e.g., Canada and the US), the Pacific Ocean (e.g., Fiji), South America/the Caribbean (Suriname, Guyana, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago) and other places (e.g., New Zealand and Australia). The spread of Hinduism has occurred in different historical periods.

Southeast Asia in general was historically influenced by Hinduism for centuries (Gu 2025a). In addition, (British) colonialism was also responsible for the spread of Hinduism. That is, over the past 1–2 centuries, as part of the former British empire, Hindus (and also Sikhs and Muslims) from the Indian subcontinent were brought to East Africa, South Africa, current-day Singapore and Malaysia, Hong Kong, Mauritius and Fiji etc. as construction workers, indentured workers, policemen, soldiers and/or merchants (Gu 2025a). In recent decades, in a broader backdrop of globalization, increasing mobility and more frequent movement of people, many Hindus (and people from other religious groups) in the Indian subcontinent choose to live, study and work in Gulf countries (e.g., the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Oman), Southeast Asia (e.g., Singapore, Brunei, Malaysia), Europe (e.g., the UK), Australia and New Zealand, and North America (the US and Canada) on a temporary or permanent basis. Now, in a context of population growth in India and the Indian subcontinent, there is a general trend of ‘Indianization’ or ‘Desi-fication’ (Gu 2025a) in Gulf countries in the Middle East, North America and elsewhere (Sancho 2020; Vora 2013) in demographic terms. The growing size of Indian and South Asian diaspora communities inevitably will mean further spread of Indian and South Asian cultures and religions and, of course, Hinduism globally.

Similar to Hinduism, Buddhism was also born in the Indian subcontinent. Buddhism, as a religion and philosophy, is based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. Buddhism once saw rapid expansion in ancient India. However, the once-prosperous religion lost influence in India for various reasons around the 7th century CE. As a result, in India, Buddhism has considerably fewer followers compared with Hinduism. Now, in India, only around 0.70% of the population are Buddhists. In recent years, despite some signs of revival, Buddhism still remains a relatively marginalized minority religion in India. Despite this, Buddhism now remains an influential religion in countries such as Sri Lanka, Bhutan, Nepal, China, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Mongolia. Major traditions or schools of Buddhism include Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana.

For some time in history, Buddhism and Hinduism developed in tension/opposition with one another. Yet, since both Buddhism and Hinduism are products of Indian culture, both religions have some shared beliefs and concepts. Indeed, some Hindus even believe that Buddha is an incarnation of Hindu god Vishnu. Given the deep-rooted historical connections between Hinduism and Buddhism (cf. Gu 2025a), it is not uncommon to find some kind of syncretism between the two religions, for example, in places such as Nepal and Thailand. Given the relatively compatible nature of Hinduism and Buddhism and often their religious syncretism, it is not always easy to separate the two in certain contexts. This is particularly the case when we talk about their (joint) influences in Southeast Asia. This is evidenced in the existence of several Hindu-Buddhist empires (e.g., the Majapahit Empire) historically in the Southeast Asian region. More detailed discussion of Hinduism/Buddhism influences in Southeast Asia is provided as follows.

3. Hinduism/Buddhism in Indonesia, the Malay World and Southeast Asia

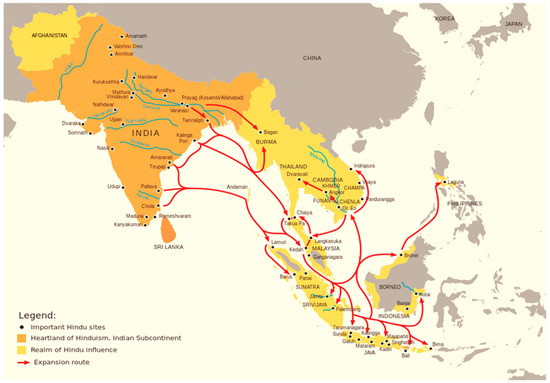

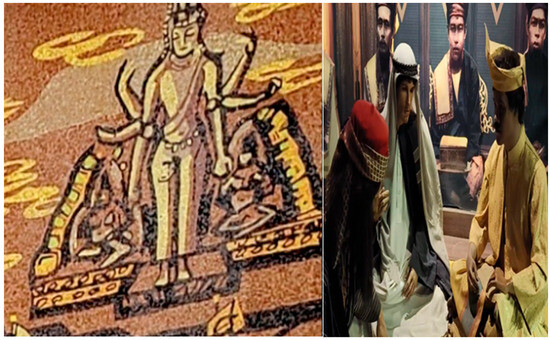

As alluded to earlier, Southeast Asia has been historically shaped by Hinduism and the Indian subcontinent in general. The broader region has seen the ebb and flow of Hinduism (cf. Figure 1 for the historical spread of Hinduism in Southeast Asia). For several centuries, current-day Southeast Asia has seen the coming and going of a few Indianized kingdoms/dynasties where Hinduism and/or Buddhism were predominantly practiced (e.g., Srivijaya and Majapahit). Majapahit, notably, was a major and powerful Hindu-Buddhist empire in the region, whose influence was felt in much of the Malay world (e.g., current-day Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei and Singapore) and Southeast Asia in general. Even now, some evidence of the historical influence of Majapahit can still be found in places like Indonesia and even Singapore (e.g., the Fort Canning Park in central Singapore). Figure 2 left, featuring a section of a mural found in the National Museum of Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur, illustrates the Hindu/Buddhist past of the Malay world in artistic form. The presence of Hinduism/Buddhism (Brown 2004) in Indonesia, the Malay world and Southeast Asia in general represents the cross-regional spread and (re)contextualization of religion and culture beyond its traditional heartland.

Figure 1.

The historical spread of Hinduism in Southeast Asia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=141850972, accessed on 10 June 2025).

Figure 2.

Left is a mural found in National Museum of Malaysia depicting the Hindu/Buddhist past of the Malay world and right is a diorama in the same museum depicting the official conversion to Islam of the Ruler of Melaka by Saiyid Abdul Aziz (a religious scholar from Jeddah).

While the Hindu elements and more visibly Buddhist elements have more or less continued to this day in places such as Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Burma, much of the Malay world (e.g., current-day Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei and arguably some parts of Thailand and the Philippines) became Islamized (Gu and Coluzzi 2024). Such Islamization, however, did not happen overnight but was a gradual process through various routes and through peaceful conversion and other means. Figure 2 right illustrates the official conversion to Islam of the Ruler of Melaka by Saiyid Abdul Aziz (a religious scholar from Jeddah). This historical event marks one of the major milestones related to the Islamization of Malaysia and much of the Malay world (e.g., Indonesia). In current-day Indonesia, many staunch Hindus who refused conversion fled to Bali, making Bali the last bastion of Hinduism in the country (alongside a few small pockets elsewhere).

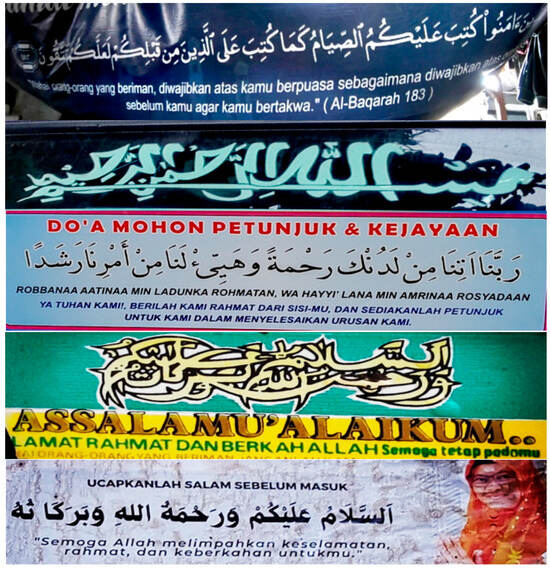

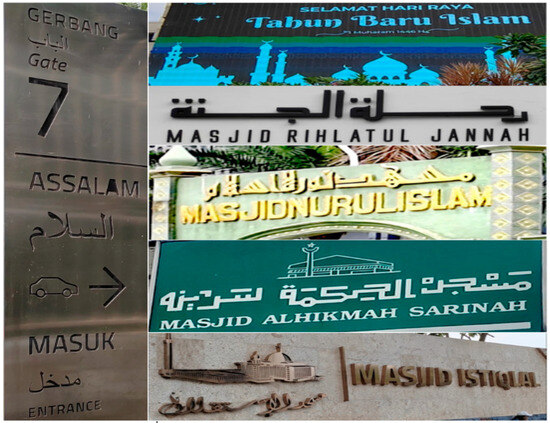

Clearly, in the transition to Islam, various Hindu/Buddhist elements were erased, removed and de-legitimized and various Islamic elements and features were foregrounded and emphasized. Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the Islam-related elements in Jakarta’s 21st century linguistic and semiotic landscape, where mosques are a pervasive sight and the Arabic script/Arabesque features enjoy visibility (e.g., religious, cultural and commercial purposes). An Arabic-based system called ‘Jawi’ (cf. Gu 2025b; Gu and Coluzzi 2024) was and to some extent is still used to write local languages in Indonesia and the Malay world. If we conceptualize our linguistic and semiotic landscape as a piece of writing, it might be understood as a ‘palimpsest’ (cf. later sections for more details). That is, in a changing historical context featuring various socio-political, cultural, religious and linguistic changes and transformations, existing (socio-political, religious and ideological) elements belonging to a former era may be erased and partially replaced with new elements. However, the old elements may still be visible and be revived. This gives rise to a dynamic negotiated process across time and space. Despite such Islamization, a number of Hindu temples can still be found in Indonesia. Most of these are in Bali (e.g., pura jagatnatha). Several others can be found elsewhere in Indonesia in general (e.g., Pura Adhitya Jaya in Jarkata). As we shall see in more details in the data analysis section, various linguistic and cultural elements related to Hinduism/Buddhism are still visible in Indonesia to some extent.

Figure 3.

Arabic and Islamic elements in Jakarta’s linguistic/semiotic landscape.

Figure 4.

Arabic and Islamic elements in Jakarta’s linguistic/semiotic landscape.

Figure 5.

Arabic and Islamic elements in Jakarta’s linguistic/semiotic landscape.

As some evidence of the multi-faceted and far-reaching influences of Hinduism/Buddhism and Indian subcontinent on Southeast Asia in general, several scripts in Southeast Asia (e.g., Thai, Balinese, Lao, Khmer, Burmese) are related to writing systems in the Indian subcontinent. In addition, a range of place names and loan words in Southeast Asia are traceable to/adapted from Sanskrit and/or various other South Asian languages. In Thailand, the Hindu/Buddhist influences are deep-rooted and visible (Gu 2025a). For instance, garuda (vehicle of lord Vishnu) appears on Thailand’s national emblem. Various Hindu shrines (Shiva, Brahma, Lakshmi, Parvati, Ganesha, Trimurti, Indra) can be found in central Bangkok and beyond. Hindu god Indra appears on Bangkok’s city emblem. Yakshas are a pervasive sight. Also, major scenes in Hinduism such as ‘Samudra Manthan’ or ‘the churning of the milk ocean’ (Gu 2025a) are depicted at Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi International Airport (the name ‘Suvarnabhumi’ itself has Sanskrit origins, meaning ‘land of gold’). The Thai name for ‘Bangkok’ is ‘Krung Thep Maha Nakhon’. ‘Maha Nakhon’ is derived from Sanskrit, meaning ‘big city’ or ‘great city’. The Hindu epic Ramayana has also been localized in Thailand as ‘Ramakien’, which is essential to Thai culture and its literary canon. The namaste-like gesture ‘wai’ is commonly used (cf. Figure 6 for the gesture in McDonalds’ in Thailand). A similar Hinduism-Buddhism-inspired gesture called sembah is commonly used in Indonesia.

Figure 6.

The ‘wai’ gesture in Thailand.

Similarly, various Hindu cultural, religious and architectural elements are visible in Angkor Wat in Cambodia. Angkor Wat is a Hindu-Buddhist temple complex and also a major tourist spot. ‘Cambodia’ itself derives from Sanskrit (Kambojadeśa), meaning the “land of Kamboja”. In Laos, elements of Hindu/Buddhist culture are also palpable. For instance, in Vientiane, various Hindu elements (e.g., depictions of Hindu gods Vishnu, Brahma, and Indra) are seen on Patuxai (also known as ‘Victory Gate’ or ‘Gate of Triumph’ in English), which serves as a war monument in the city. In Malaysia, approximately 6.3% of Malaysia’s population are Hindus (e.g., mostly of Tamil and South Indian origins) and various Hindu temples can be found in Kuala Lumpur and across the country. The Thaipusam festival is celebrated. Many street, MRT station, place and business names in Kuala Lumpur and surrounding areas have full or partial origins in Sanskrit and Indian languages (cf. Figure 7 for some examples). Featuring Sanskrit-derived elements such as ‘sri’ (a prefix or honorific title, indicating respect, reverence, elegance, wealth and prosperity), ‘jaya’ (successful and victorious), ‘surya/suria’ (sun/sun god), ‘putra’ (son; prince), ‘putri’ (daughter; princess), ‘negara’ (national), ‘naga’ (snake; dragon), ‘raja’ (king) and ‘desa’ (place, country, village), these Sanskrit-influenced station and place names include ‘Sri Petaling’, ‘Bandar Sri Damansara’, ‘Cyberjaya’, ‘Berjaya Times Square’, ‘Putrajaya Sentral’, ‘Putra Heights’, ‘Muzium Negara’, ‘Taman Desa’, ‘Raja Chulan’, ‘Maharajalela’, and ‘Suria KLCC’. In a context of globalization, now many Hindus from India and Nepal (and also other South Asians) work in Malaysia as security guards in hotels and malls and as waiters and salesmen etc. In Singapore, there is also a sizeable Hindu community. Even the city state’s name ‘Singapore’ or ‘Singapura’ in Malay is derived from Sanskrit (‘Singa’ means ‘Lion’ and ‘Pura’ means ‘city’, hence ‘Lion City’). In the Malay world or Dunia Melayu in general, ‘Laksamana’ (originated from Sanskrit and related to the figure ‘Lakshmana’ from the Hindu epic of Ramayana) is a common term, title and rank (e.g., in the navy) in Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei. More details about the influence of the Indian subcontinent on Southeast Asia can be found in Gu (2025a).

Figure 7.

Place and station names in Malaysia with full/partial Sanskrit origins.

4. The Linguistic and Semiotic Landscape as a ‘Palimpsest’

Made up of monolingual, bilingual and multilingual signs (at top-down and bottom-up levels) and various multimodal designs (e.g., certain colors, patterns and features), linguistic and semiotic landscape (Landry and Bourhis 1997; Gorter and Cenoz 2023; Scollon and Scollon 2003) represents an important aspect of our multidimensional and multi-layered world (alongside the natural landscape and architectural landscape, etc.). Linguistic and semiotic landscape is not just a theoretical framework but also provides a useful source of data and represents an important object of study (Kallen 2023; Wu et al. 2020). Holistically, various linguistic and multimodal elements (Scollon and Scollon 2003; Jaworski and Thurlow 2010) in the linguistic and semiotic landscape point to the idea of a semiotic assemblage (Pennycook 2017) or a multimodal ensemble (Kress and van Leeuwen 2001). These various multilingual, multimodal, multisemiotic, multi-layered elements together contribute to the meaning-making process, giving a place identity (Song and Gu 2025). A place’s linguistic and semiotic landscape can be seen as a narrative or discourse, which tells vivid stories about a place’s past, present and future (Gu 2026). From this perspective, a locale’s linguistic and semiotic landscape is a witness to a place’s diachronic developments in a constantly changing context, serving to document various historical, religious, cultural, ideological and linguistic changes and transformations (Gu 2026; Manan et al. 2017; Coluzzi 2009; Alomoush 2023).

In particular, the linguistic and semiotic landscape might be fruitfully conceptualized as a ‘palimpsest’. A palimpsest refers to a manuscript, document or piece of writing in which the old content has been removed and superimposed or replaced by new writing. In many ways, our (urban) space is such a palimpsest (Starks and Phan 2019), where there are always multiple layers of meaning. These different layers of meaning are dynamic and constantly negotiated in nature (Gu 2026). That is, for various socio-political, religious and ideological reasons, some new elements may replace or are superimposed on old elements. For example, in Chinese history, a new dynasty would often erase some elements of the previous dynasty. Similarly, when Islam took over, certain religious and cultural elements from the earlier era (e.g., Hinduism or Buddhism) might be destroyed and replaced. Or likewise, after the Reconquista on the Iberian Peninsula, various elements of Christianity were revived and restored, whereas certain Islamic elements were de-legitimized and removed (Said and Rohmah 2018). Yet, often, the old elements from an earlier period cannot be removed completely, which may still be visible to some extent. Certain covered/replaced elements may also re-emerge in a changing context. Given the history of Indonesia that was shaped by Hinduism/Buddhism and later Islam, the country’s linguistic and semiotic landscape is such a constantly negotiated/updated palimpsest (Starks and Phan 2019) and a site of polyphony (Bakhtin 1981), where various voices, layers and linguistic traces co-exist (Gu and Coluzzi 2024). All these dynamically combine to tell a story about the place’s past, present and possibly future.

The fact that a place’s linguistic/semiotic landscape represents a ‘palimpsest’ highlights its great potential to be examined from the lens of religion-related matters. To date, while such topics as language policy, multilingualism, the power of English, language ideology, linguistic vitality and ethnic enclaves have attracted great scholarly attention (Amos 2016; Hopkyns and van den Hoven 2022; Zhang et al. 2023; Song 2022; Sharma 2021; Lou 2016; Shang and Yao 2024), religion remains largely under-explored by linguistic and semiotic landscape researchers. Indeed, so far, only relatively few studies have explored religion-related linguistic and semiotic landscapes. These include Esteron (2021), Coluzzi and Kitade (2015), Said and Rohmah (2018), Woldemariam and Lanza (2012), Kochav (2018), Gu (2025a) and Alsaif Ali S and Starks (2020). Notably, Esteron (2021) explored the Churchscape in the Philippines and the use of English. Focusing on the Malaysian setting, Coluzzi and Kitade (2015) also dived into the country’s religious linguistic landscape in Kuala Lumpur. Furthermore, Christian proselytizing and the use of signs have been examined in an African context in Woldemariam and Lanza (2012). Attentive to the Israeli context, Kochav (2018) explored religious expressions in the linguistic landscape. In the interesting study by Alsaif Ali S and Starks (2020), the authors studied how religious meanings are conveyed based on linguistic and semiotic data collected from the Grand Mosque of Mecca. Clearly, religion and religion-related issues have remained significantly under-investigated in extant research. Hinduism-related topics have been particularly under-explored from a linguistic/semiotic landscape perspective. Gu (2025a) is a recent study that has explored manifestations of Hindu elements in Bangkok’s linguistic and semiotic landscape.

5. Methodology and Data Collection

This section sets out the methodology used for data collection before providing more details about the data included in the corpus. A general method of ‘walking ethnography’ (cf. Coluzzi and Kitade 2015; Gu 2025a; Landry and Bourhis 1997; Hopkyns and van den Hoven 2022; Song and Gu 2025) was applied in this study, which is a common methodology used in linguistic/semiotic landscape research. As mentioned earlier, while Indonesia in general has a Muslim majority, Hinduism is still practiced in Bali. Instead of choosing Bali (where various Hindu elements are evident/expected), the author carried out in-depth field trips in Jakarta in July 2024. Jakarta is a populous megacity and the dynamic capital of Indonesia (new planned capital is Nusantara). Jakarta also had significant Dutch and Western colonial influences. In Jakarta, 83.83% of its population are Muslims (Hindus constitute only 0.18%). Also, Jakarta is located on Java island, the most populous island in the world (54– 56% of Indonesians live on this island). Compared with Bali, choosing the Muslim-majority city Jakarta for data collection would help gain more representative and vivid findings regarding the traces of Hinduism left on Indonesia’s 21st century linguistic and semiotic landscape. The results are likely to be more salient, telling and reflective of the overall situation in Indonesia. Clearly, elements of Hinduism are not concentrated in certain specific areas. As such, it was not possible to collect data purposefully in certain streets. Indeed, the very purpose of the study is to establish the more ‘everyday’ presence and ‘routine’ elements/traces of Hinduism/Buddhism in the linguistic and semiotic landscape (Hinduism-related elements and practices locals might take for granted or are not even aware of). After walking around in different places in Jakarta (including both high-end shopping malls, tourist areas and relatively ‘poor’ areas inhabited by the ordinary people), the author managed to collect or chance upon 431 photos related to the city’s Hindu/Buddhist past. The author has some knowledge of Bahasa Indonesia and languages from the Indian subcontinent. Trained as a linguist, the author has great sensitiveness to and linguistic awareness of the topic under investigation. Also, having been to South Asia and places such as Southeast Asian and the Gulf region (places with significant South Asian influences), the author has some knowledge of Hinduism and is familiar with such linguistic, cultural and religious contact at different levels. As such, it was relatively easy to make out elements related to Hinduism (e.g., street/place names with elements from Sanskrit, business names featuring names of Hindu deities such as Ganesha, and symbols, emblems, sculptures, statues and paintings about Hinduism/Hindu figures such as garuda). 298 of these signs contain linguistic elements and 133 feature semiotic elements. The collected data were further processed and analysed. The main features and findings that emerged from the analysis are provided in the following section. In addition, the author had brief conversations with 10 local Indonesians in Jakarta (5 male and 5 female and all were Muslims) and asked them (1) whether they were aware of the country’s Hindu/Buddhist past and (2) whether they knew the national symbol Garuda was originally from Hinduism (Garuda is regarded as the vehicle of Hindu god Vishnu) and wayang kulit tended to portray Hindu deities/epics. Additional insights/findings from such brief conversations are provided to further complement the linguistic and semiotic landscape-oriented analysis.

6. Data Analysis

For clearer presentation, the data are discussed based on the linguistic elements and then the semiotic elements. Both components form a semiotic assemblage (Pennycook 2017) or a multimodal ensemble (Kress and van Leeuwen 2001), contributing to the city’s Hindu-scape (cf. Gu 2025a), materially and discursively.

7. Linguistic Manifestations of Hinduism

First and foremost, a salient feature in Jakarta’s LL has to do with the explicit mentioning of key Hindu deities and Hindu epics. In Jakarta and surrounding areas, for example, several official street and road names feature Hindu elements. These include ‘Jalan Jatayu’, ‘Jalan Garuda’, ‘Jalan Hanoman’, ‘Jalan Shinta’, ‘Jalan Arjuna’ and ‘Jalan Rama Raya’. Interestingly, in the high-profile Grand Indonesia mall in central Jakarta, several lobbies are named after key figures in Hindu epics such as Ramayana (Figure 8). These major Hindu figures and stories include Ramayana (major Hindu epic), Rama (a major figure in Ramayana), Ayodya (or ‘Ayodhya’, a sacred city in northern India that is believed to be the birthplace of Rama), Shinta (‘sinta’ or ‘Sita’ a major figure in Ramayana), Arjuna (a key figure in Hindu epic Mahabharata), pandawa (a group name referring to the five legendary brothers who are key figures in Mahabharata), Amarta (or ‘Amrita’, which means “immortality” and “elixir” in Hinduism). These Hinduism-inspired lobby names are full of symbolic meanings. Such high prominence of Hinduism is surprising, creating a great sense of contrast in a Muslim-majority country. Notably, the Hindu elements are (re)contextualized in Indonesia with localized spellings. For example, Shinta/Sinta is the local Indonesian way of spelling ‘Sita’, and ‘Ayodya’ is the local way of spelling ‘Ayodhya’. Similarly, various Hindu names have also been localized and recontextualized in places such as Thailand with local spellings, as a result of cross-region civilizational contact (cf. Gu 2025a). Some of the Hindu figures are commonly portrayed in wayang kulit (a traditional form of shadow puppetry found in Indonesia and the Malay world). Wayang kulit, essential to Indonesian culture, typically is based on Hindu epics such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata. In many ways, wayang kulit represents Hindu epics (re)contextualized in a Southeast Asian context (cf. Figures 24 and 25 for more details).

Figure 8.

Lobby names in Grand Indonesia mall featuring Hindu deities and epics.

In addition to this high-end mall, across Jakarta (and Indonesia in general), many businesses that explicitly feature names of Hindu deities and epics (Figure 9) can be found (e.g., hotels, restaurants, bakeries, supermarkets). These include ‘Anoman’ (the localized version of ‘hanuman’, who is the monkey-like god who plays a key role in rescuing Rama’s wife Sita from Ravana in Ramayana and who is commonly portrayed in wayang kulit), Indra (a Hindu god of weather and the king of the devas and svarga in Hinduism), Ganesha (the son of Shiva and Parvati), garuda (vehicle or mount of Vishnu), Ramayana (Hindu epic), Rama and Shinta (key figures of Ramayana) and Laxmi (or ‘Lakshmi’ who is Hindu goddess of wealth). Interestingly, despite the Hindu-sounding business names, many owners and managers of the businesses are not Hindu. These are perfect examples of ‘everyday’ traces of Hinduism recontextualized in Muslim-majority Indonesia’s linguistic landscape in a sense that elements of Hinduism are taken for granted as part of the country’s cultural heritage (which may or may not be related to religion per se). Other examples of businesses with Hindu-sounding names include ‘Kost Shinta’, ‘Ganesha Tanah Mas Tennis Park’, ‘Club de Arjuna’, ‘de Arjuna Café’ and ‘Lakshmi Massage’.

Figure 9.

Grass-roots business names featuring Hindu deities and epics.

Beyond such more explicit or obvious traces of Hinduism, significantly more street names, place names and business names feature elements from Sanskrit and Indian languages in general. Sanskrit and languages from the Indian subcontinent have had an enduring legacy in Indonesia and much of Southeast Asia (Gu 2025a). The presence of Sanskrit elements is often inextricably connected with Hinduism and/or Buddhism and the country’s dharmic past over centuries. Indeed, many common place names in Indonesia and the Malay world can be traced to Sanskrit and languages in the Indian subcontinent (Jones and Phillips 1995). These names with Sanskrit/South Asian origins include ‘negara’ (country), ‘raja’ (king), ‘putra’ (son or prince), ‘putri’ (daughter or princess), ‘jaya’ (success), ‘surya’ (sun), and ‘sempurna’ (perfect or whole). These, more implicit/hidden in nature, are powerful testament to Indonesia’s Hindu/Buddhist past as etched on the country’s LL.

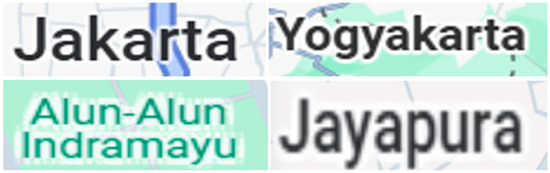

Notably, even the name of the Indonesian capital city ‘Jakarta’ can be traced to Sanskrit (cf. Figure 10). Jakarta is derived from Sanskrit जयकर्ता (Jayakartā), which means “victory accomplished”. Other city/place names (Figure 10) with full or partial Sanskrit/Indian origins include Yogyakarta/Ngayogyakarta (believed to be related to the Indian city of Ayodhya, which is the birthplace of Hindu deity Rama), Indramayu (‘Indra’ is Hindu god), Jayapura (‘jaya’ means ‘victory’ and ‘pura’ means ‘city’). In addition to Sanskrit/Indian elements ‘fossilized’ in place names, in more common everyday business names, elements of Sanskrit are also widely visible. This is illustrated in Figure 11. Such names include ‘surya’ (sun), ‘jaya’ (victory; success), ‘surya raya’ (‘Great Sun’), and ‘sampoerna’/‘sempurna’ (both words mean ‘perfect’ and are derived from Sanskrit). ‘Sampoerna’ featuring ‘oe’ is the old spelling following Dutch-era conventions. Also, ‘Bumiputera’ or ‘bumiputra’ is derived from Sanskrit, meaning ‘son of the soil’ or ‘son of the land’. This term is often used to refer to groups that are considered to be ‘native’ or ‘indigenous’ in Indonesia or the Malay world, which can have political and ideological implications. Since these words are commonly used in Indonesia for a long time, the businesses may simply take these for granted and believe that these are just Indonesian (without necessarily considering their Sanskrit/Indian origins).

Figure 10.

Indonesian city names featuring Sanskrit-derived components.

Figure 11.

Business names featuring Sanskrit elements (e.g., sempurna, surya, jaya, bumi, putra).

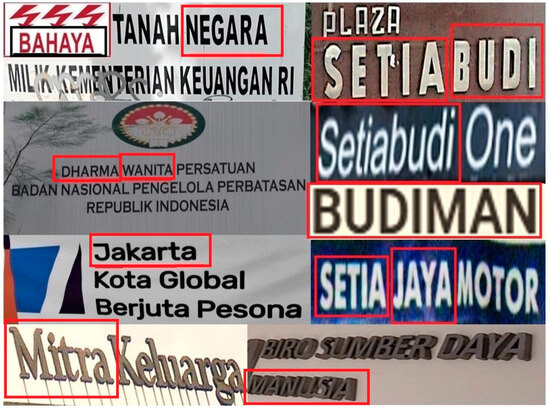

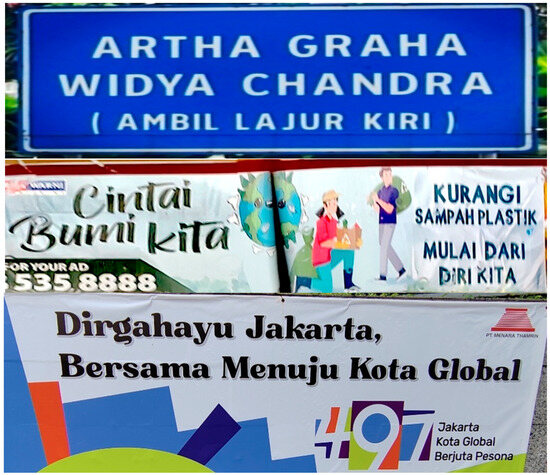

More examples of Sanskrit having a ‘second’ life in Jakarta’s LL can be found in Figure 12 and Figure 13. Figure 12 shows several commonly seen words in Indonesian that are of Sanskrit origins. These include ‘Bahaya’ (danger), ‘negara’ (national), ‘dharma’ (duty, good deeds, truth, righteous path etc.), ‘wanita’ (girl or woman), setiabudi (loyal, faithful and kind), budiman (wise person; intelligent), ‘mitra’ (friend or partner) and ‘manusia’ (human being; human). For example, the common warning sign ‘bahaya’ (danger) is derived from Sanskrit ‘bhaya’ (fear). However, there has been some shift in meaning. Also, ‘setiabudi’ is a common name in Jakarta/Indonesia, made up of ‘setia’ and ‘budi’. These two elements correspond to ‘satya’ (truth) and ‘buddhi’ (wisdom and intellect) in Sanskrit respectively. This Indonesian word ‘setiabudi’, combined from Sanskrit, indicates a positive meaning of faithful, trustworthy, reliable, kind and wise. Other examples of this include ‘mitra terrace’ and ‘mitra keluarga’. Notably, Figure 13 top (direction sign) features a few words from Sanskrit such as ‘graha’ (house; office, building, planet), ‘widya’ (knowledge) and ‘chandra’ (moon). In Figure 13 middle, the message in Indonesian says ‘cintai bumi kita’ (love our earth/planet). ‘Bumi’, meaning ‘earth’ or ‘land’, is derived from Sanskrit. The sign in Figure 13 bottom says “Dirgahayu Jakarta, Bersama Menuju Kota Global’ (which means ‘happy birthday/long live Jakarta, together towards a global city’). This slogan is commonly found in Jakarta, which contains words from different origins (e.g., Indonesian, Western languages and also Sanskrit). Notably, ‘dirgahayu’ is derived from Sanskrit, which means ‘longevity’ or ‘long life’. This slogan indicates good wish for Jakarta’s longevity and continued success towards becoming a prosperous and global city. This slogan (featuring Sanskrit partially) is yet another salient example that shows Sanskrit’s enduring legacy in Indonesia’s linguistic landscape. Such linguistic evidence reminds us of the LL study by Said and Rohmah (2018), which examined the remaining traces of Arabic and Islam-related elements in the ‘Andalusian’ linguistic landscape in current-day Spain (Spain was partially under Islamic rule for centuries before the ‘Reconquista’). They similarly found that Arabic is hidden in Spanish toponyms and has morphed into Spain’s LL in various ways.

Figure 12.

Business names featuring Sanskrit elements (e.g., negara, setia, wanita, mitra, budiman and manusia).

Figure 13.

Street-level signs featuring Sanskrit elements (e.g., widya, chandra, bumi and dirgahayu).

In Jakarta’s linguistic landscape, various mottos and slogans with partial/complete Sanskrit origins are also widely visible (Figure 14). Appearing alongside the bird-like Hindu deity Garuda (cf. Figure 15 and elsewhere for more details), these mottos and slogans often are found in emblems and symbols related to the Indonesian government and related ministries and bodies and the army, etc. These mottos and slogans with full or partial Sanskrit elements include ‘Bhinneka Tunggal Ika’ (Indonesia’s official and national motto meaning ‘unity in diversity’) and ‘Kartika Eka Paksi’ (motto of the Indonesian army meaning ‘Unmatchable Bird with One Noble Goal’). It is fascinating to see these Sanskrit-derived words originally from ancient India being (re)contextualized on a far-away land that is Muslim majority for specific purposes. More examples of such Sanskrit-derived slogans and mottos are listed in Table 1. From this perspective, Sanskrit has been an integral part of Indonesia in the political and official spheres. Some of the slogans and mottos in Indonesia related to Sanskrit are also discussed in https://dharmorakshtirakshitah.wordpress.com/2020/03/09/tryst-with-indonesia-hindu-heritage-overview/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

Figure 14.

Mottos and slogans with full/partial Sanskrit elements.

Table 1.

Mottos and Slogans with full/partial Sanskrit origins.

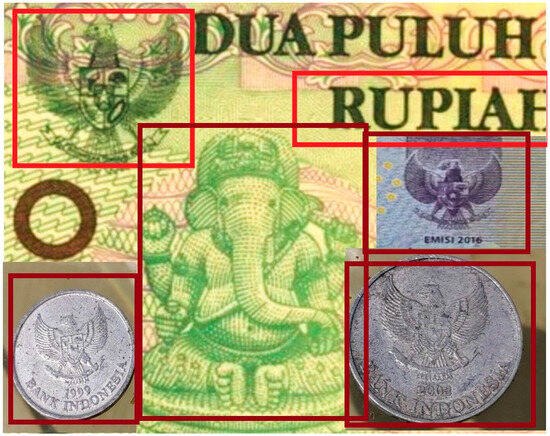

There are many more Sanskrit/Indian-origin words that have morphed into Indonesian and the Indonesian nation, where traces of Hinduism and South Asian influences are palpable. Notably, the name of Indonesian language is called ‘Bahasa Indonesia’. ‘Bahasa’ (language) is derived from Sanskrit (bhasha). Also, the name of Indonesia’s official currency ‘rupiah’ (cf. Figure 18) is derived from ‘rupyakam’ (रूप्यकम्), which means ‘silver’ in Sanskrit (a few currencies in South Asia now are also called ‘Rupee’). In addition, ‘Garuda Pancasila’ is the national emblem of Indonesia. Garuda, according to Hinduism, is a bird-like deity and divine creature. Garuda is known as the mount (vahana) of the Hindu god Vishnu (the God of Preservation). There is a famous airline in Indonesia called ‘Garuda Indonesia’. Garuda (locally known as ‘krut’ or ‘khrut’ in Thailand) is also an important part of Thai culture. ‘Pancasila’ (Jones 2005) is of great symbolic, cultural and political meanings in Indonesia. The name ‘pancasila’ etymologically is made up of two words originally derived from Sanskrit: ‘pañca’ (‘five’) and ‘śīla’ (‘principles’, ‘moral conduct’ or ‘precepts’). As a political and philosophical theory, ‘Pancasila’, or ‘Five Principles’, is of foundational importance to modern-day Indonesian nation.

As another kind of linguistic landscape, many Indonesians (even Muslims) tend to use names related to Hinduism and/or Sanskrit in general. These names include Krisna, Indra, Laksamana, Sarasvati, Rama, Laksmi, Dewi, Cakra, Wijaya, Putri, Putra, Satya, Wisnu, Surya, Aditya, Ganesha. For example, an Indonesian Muslim politician is named ‘Giring Ganesha’. Some more details about Indonesian names can be found here https://www.awazthevoice.in/world-news/indonesian-muslims-celebrate-their-hindu-buddhist-past-hamid-naseem-shares-experiences-22421.html (accessed on 20 June 2025).

8. Semiotic Manifestations of Hinduism

In addition to the linguistic elements, traces of Hinduism in Jakarta also manifest in the form of various semiotic elements (e.g., depictions and portrayals of Hindu epics and statues and sculptures of Hindu gods and goddesses).

Garuda is perhaps the most visible Hindu deity found in Jakarta and Indonesia’s semiotic landscape. The bird-like Hindu deity is the mount of Hindu god Vishnu. Garuda is a national symbol of Indonesia and is in many ways central to the very psyche of the nation. Garuda notably appears on emblems and logos of various ministries and government bodies and organizations (cf. Figure 15). It also appears on the jerseys of the Indonesian football team (cf. Figure 16). Interestingly, the country’s national team is colloquially known as ‘Tim Garuda’ (or ‘Garuda Team’). A rallying cry of the football team (Figure 16) is #KITAGARUDA (which is Indonesian for ‘We are Garuda’). This morale-boosting slogan shows how Hinduism is deep-rooted in the nation. However, the ‘Hindu’ connection does not stop here. As illustrated in Figure 17, the image of Garuda can be found from food packages to aircraft (Garuda Indonesia) and from large paintings to the cart of street vendor (selling cilok). Various Hindu elements have also appeared on Indonesian money (earlier currencies and/or current ones). Figure 18 shows the images of the elephant-like Hindu god Ganesha and the bird-like deity Garuda on coins and banknotes. Given the nature of the currencies, they point to a kind of mobile linguistic landscape (Gu 2025a). Hindu deities/elements are also a great source of inspiration for statues, sculptures, buildings and infrastructure in the architectural landscape or semiotic landscape in general. Figure 19 left presumably is a statue of garuda or maybe jatayu (who is related to Garuda), found outside the Soekarno–Hatta International Airport. Figure 19 right is a relatively large street painting found on Jalan Pintu Besar Selatan in Jakarta’s old town (Kota Tua). This is an artistic representation of Vishnu riding on Garuda. Beyond Jakarta, Garuda has inspired many buildings and projects. Figure 20 top illustrates ‘Istana Garuda’ or ‘Garuda Palace’ in Indonesia’s new planned capital Nusantara. The design resembles the wings of Garuda. Figure 20 bottom is Garuda Wisnu Kencana statue (or GWK statue), a large Hinduism-related statue found in Bali. Clearly, the Hindu deity Garuda, as a symbol, evokes great patriotic sentiments in Indonesia, which is an important part of the very psyche and cultural and national spirit of the Southeast Asian nation.

Figure 15.

Garuda in Jakarta’s linguistic and semiotic landscape.

Figure 16.

Garuda appearing on football jerseys.

Figure 17.

Other examples of Garuda on the semiotic landscape.

Figure 18.

Ganesha and Garuda appearing on Indonesian money.

Figure 19.

Statues and portrayals featuring Hinduism-derived elements (left features a statue of garuda or maybe jatayu found in the airport and right features a depiction of Vishnu mounted on garuda).

Figure 20.

Istana Garuda or Garuda Palace in Indonesia’s new planned capital Nusantara (photo from https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/world/2024/06/05/indonesia-replaces-new-capital-chief-weeks-before-opening/) (accessed on 20 June 2025) and Patung Garuda Wisnu Kencana (photo from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Patung_Garuda_Wisnu_Kencana_pada_tahun_2024.jpg) (accessed on 20 June 2025).

At the center of the political heart of Jakarta and Indonesia, the Arjuna Wijaya Statue (‘chariot of the victorious Arjuna’) can be found (just outside the MONAS or The National Monument). ‘Arjuna wijaya’ is derived from Sanskrit/Indian languages and it means ‘the victory of Arjuna’. This statue (Figure 21) is officially known as ‘Monumen Untukmu Indonesia’ or ‘For You Indonesia Monument’. This statue depicts Krishna, who is riding the chariot with Arjuna. This represents a vivid depiction of a major scene in the Hindu epic Mahabharata. Commissioned by President Soeharto, the statue symbolises the freedom of the country and represents a strong sense of Indonesian cultural heritage and national pride. In 2018, the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited the Arjuna Wijaya Chariot Statue, accompanied by the Indonesian President Joko Widodo. The statue itself is a witness to the cross-region transmission of civilization and religion, representing a vibrant testimony of the deep-rooted historical and cultural ties between India and Indonesia. Such high-profile portrayal of Hindu figures is fascinating and somewhat surprising (especially from the perspective of outsiders), given the fact that Indonesia is the world’s largest Muslim country (Islam often does not allow idols). Figure 22 shows some examples where Hindu/Buddhist-related figures (e.g., Hindu god Ganesha) are depicted. Figure 23 shows paintings related to the country’s Hindu/Buddhist past. The existence of these Hindu elements in a predominantly Muslim country’s linguistic and semiotic landscape may have a religious, cultural, visual, artistic and at the same time political dimension. It calls for nuanced, critical and contextualized analysis, for instance, in a context of ‘adat’ and ‘agam’ and in a context of the recent (20th and 21st century) influence of Indic Hindu religious movements, and the state’s efforts to make Hinduism monotheistic (cf. McDaniel 2013). Notably, the sculpture of Arjuna and Krishna mentioned above is fascinating when considered in relation to the recent attempts to recreate Indonesian Hinduism in a more Indic form, as one reviewer of the article has pointed out.

Figure 21.

The Arjuna Wijaya Statue (scene from the Hindu epic Mahabharata).

Figure 22.

Ganesha (left) and other Hinduism/Buddhism-related figures and deities (right).

Figure 23.

Paintings related to Indonesia’s Hindu/Buddhist past.

Perhaps the most salient example of Hindu elements in Jakarta and Indonesia in general is Wayang kulit (a traditional kind of shadow puppetry found in Java and Bali and some other parts of Indonesia). Wayang kulit is heavily influenced by Hinduism and Buddhism and many scenes are based on the Hindu epics Mahabharata and Ramayana (many often follow the storyline of the good succeeding over the evil and certain love stories). In the old town of Jakarta (Kota Tua), there is notably even a Wayang Museum, where many Hinduism-related elements are displayed (Figure 24 and Figure 25). Figure 24 top illustrates a scene from Ramayana. Figure 24 bottom right illustrates the ten-headed Ravana (who ruled Lanka). Figure 25 bottom left portrays Rama and Laksmana. In several other photos in Figure 24 and Figure 25, Rama, Hanuman and other deities and figures can also be found. This kind of traditional art form still has some relevance now, which can be seen as Hinduism/Buddhism culture (re)contextualized in Indonesia and the Malay world, with the mixture of some local historical and cultural components. Despite the fact that much of Indonesia is now Islamic, Wayang kulit (with significant Hindu elements) is still celebrated by both Hindus and Muslims as part of Indonesia’s cultural heritage. Interestingly, at some point, Wayang was even adapted and used as a propaganda medium to help spread Islam in places such as Java in Indonesia’s Islamization process (Suhardjono 2016).

Figure 24.

Hinduism-related figures displayed in Wayang Museum (e.g., scene from Ramayana and the ten-headed Ravana).

Figure 25.

Hinduism-related figures displayed in Wayang Museum (e.g., depiction of hanuman).

During the interviews/short conversations with the 10 local Muslims of varied ages, I asked them (1) whether they were aware of the country’s Hindu/Buddhist past and (2) whether they knew that the national symbol Garuda was originally from Hinduism and the key artistic form wayang kulit tended to depict Hindu deities/epics. Only two were clearly aware of the Hindu history of the nation (they said they learned it from school/learned that from watching YouTube videos). One person said that he was not quite clear about this. Seven others tended to believe that elements such as Garuda and wayang kulit were simply traditional Indonesian culture (budaya indonesia). While this is by no means systematic and the sample size is rather small, this at least shows the fact that some/many Indonesians simply take the various Hindu elements for granted and do not have a clear awareness of the nation’s Hindu/Buddhist past spanning several centuries. In predominantly Islamic Indonesia, there is seemingly some kind of de-coupling from Hinduism as a religion yet it is very much interwoven into local and national cultural identity. While everyday Indonesians may not immediately identify such elements as being Hindu/Buddhist or from South Asia, they may ascribe these to their local culture. In other words, the various Hinduism/Buddhism-related linguistic and semiotic elements evidenced in the urban landscape may be recognized as local in origin, that is, part of local (e.g., Javanese) and/or Indonesian culture (cf. Beatty 1999; Mulder 1983). From this perspective, these various Hindu elements have been absorbed into the idea of ‘Nusantara’ as an overarching cultural and linguistic identity of the broader region. This highlights the idea of ‘palimpsest’ discussed in this study. That is, when a new religion comes (e.g., Islam), it may replace some traces of the earlier religion (e.g., Hinduism/Buddhism). Yet, elements of the earlier religion(s) might not be completely erased. Some elements of it might be re-interpreted, adopt new social meanings, morph into new forms in a new context and, to some extent, appear alongside the new religion. This results in hybridity and multi-layeredness in a place’s religious, cultural, artistic and linguistic landscape.

9. Conclusions

Indonesia is a predominantly Muslim country with a dharmic heritage. Over the centuries, the nation has drawn inspirations and wisdoms from both Hinduism/Buddhism and Islamic traditions. Indonesia’s linguistic and semiotic landscape has been fruitfully conceptualized as a ‘palimpsest’, where different linguistic, religious and ideological elements have been historically (re)written and constantly updated. While the newer elements may be superimposed onto the earlier elements, the linguistic and semiotic landscape as a palimpsest may still bear visible traces of its earlier form. That is, the once-dominant linguistic and semiotic elements related to Hinduism/Buddhism in Indonesia gave way to Islam as the broader region became Islamized several centuries ago. However, in Muslim-majority Indonesia, the various elements of Hinduism/Buddhism did not disappear completely. Indeed, as demonstrated in this article, traces of Hinduism/Buddhism are still to some extent visible in Jakarta’s linguistic and semiotic landscape at different levels (both on fixed and on moving/mobile objects). These traces of Hinduism/Buddhism manifest themselves in street and business names (e.g., Anoman Studio, Indra Bakery, Rama & Shinta, Bank Ganesha, Laxmi Tailors) and Sanskrit-origin slogans and mottos, etc. Also, Hindu deities, epics and symbols (e.g., Garuda, Mahabharata, Ramayana) are visible in the semiotic landscape (e.g., statues, sculptures and the traditional wayang kulit). These linguistic and multimodal elements illustrate a degree of Hindu-ness, pointing to the nation’s Hindu-scape (cf. Gu 2025a).

From this perspective, the linguistic and semiotic landscape serves as a library, museum or historical record, where various historical elements are preserved. These elements attest to the nation’s Hindu/Buddhist past. These also indicate a kind of hybridity and historical complexity, giving rise to different layers of social, cultural and religious meanings. In many ways, the Hindu elements seemingly have been de-coupled with Hinduism as a religion. Instead, the various Hindu elements have been (re)contextualized, absorbed into and become part of Indonesian culture (that is also jointly shaped by various cultures and civilizations from the Arab world, China, the Netherlands and the Malay world and Southeast Asia in general). This is also confirmed by my conversations with ten local Indonesians in Jakarta (many tended to simply equate the Hindu elements with local Indonesian culture/national symbols). This to some extent shows the somewhat malleable nature of religious elements, which can be adapted and morph into new forms after rounds of (re)contextualization. That is, religious elements can appear in softer manifestations/versions, morphing into more routine and ‘everyday’ culture in a changing socio-political, religious and ideological context (e.g., the Islamization of Indonesia and the Malay world).

Overall, interdisciplinary in nature, this empirical study, from a unique linguistic and semiotic landscape perspective, promises to contribute to scholarship in sociolinguistics, Hindu and Buddhist studies, religious studies, Indonesian and Malay studies, Southeast Asia studies, urban studies, intercultural communication, linguistic anthropology and visual ethnography in general. It adds to a growing body of linguistic and semiotic landscape research exploring Indonesia and the Malay world (Gu 2026; Gu and Coluzzi 2024; Zhang et al. 2023) and Southeast Asia in general (Gu 2025a; Gu and Bhatt 2024; Phanthaphoommee and Gu 2024; Starks and Phan 2019; Wu et al. 2020). This study also paves the way for further research into other religious, linguistic and civilizational contact points and the linguistic and semiotic landscape of (religion) change. Like Indonesia and the Malay world, notably, Afghanistan, the Uyghur-speaking Xinjiang province in Western China, parts of the Indian subcontinent (e.g., current-day Pakistan and Bangladesh) and current-day Turkey etc. used to be under the religious and civilizational influences of Buddhism, Hinduism or Christianity yet became Islamized several centuries ago. In addition, parts of the Iberian Peninsula (current-day Spain and Portugal) and parts of the Balkans were once Islamized/under significant Islamic influences and then became (fully or partially) ‘de-Islamized’. These places that have witnessed significant religious shifts and changes provide fertile ground for research from a linguistic and semiotic landscape perspective. These places can be examined as ‘palimpsests’ to highlight how (linguistic/semiotic) traces of the previous ideology, religion and civilization may still be visible or replaced by the new religion/ideology. Said and Rohmah (2018), for example, have made some effort in this direction, who explored Arabic and Islam-related elements in the ‘Andalusian’ linguistic landscape in current-day Spain that was under Islamic rule for centuries. The current study is linguistic and semiotic landscape-oriented. Admittedly, the brief conversations/interviews are far from being in-depth and systematic, which are only the icing on the cake to help provide some additional information and ethnographic context. Going forward, given the important nature of the topic, more systematic and in-depth interviews with more rigorous design can be carried out to shed further light on this line of research.

Funding

This research was funded by Hong Kong Polytechnic University Start-up Fund (P0043805).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (Project identification P0043805) in December 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data is part of a larger ongoing project and is therefore not available.

Conflicts of Interest

The research does not have any conflict of interest.

References

- Afrianty, Dina. 2012. Islamic Education and Youth Extremism in Indonesia. Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism 7: 134–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomoush, Omar I. S. 2023. Multilingualism in the Linguistic Landscape of the Ancient City of Jerash. Asian Englishes 25: 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaif Ali S, Reema, and Donna Starks. 2020. The sacred and the banal: Linguistic landscapes inside the Grand Mosque of Mecca. International Journal of Multilingualism 18: 153–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, H. William. 2016. Chinatown by Numbers: Defining an Ethnic Space by Empirical Linguistic Landscape. Linguistic Landscape 2: 127–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardika, I. Wayan, and Peter Bellwood. 1991. Sembiran: The Beginnings of Indian Contact with Bali. Antiquity 65: 221–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtin, Mikhail Mikhailovich. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Edited by Michael Holquist. Translated by Caryl Emerson, and Michael Holquist. Austin: London: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, Andrew. 1999. Varieties of Javanese Religion: An Anthropological Account. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Iem. 2004. The Revival of Buddhism in Modern Indonesia. In Hinduism in Modern Indonesia: A Minority Religion Between Local, National, and Global Interests. Edited by Martin Ramstedt. London: New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Coluzzi, Paolo. 2009. The Italian Linguistic Landscape: The Cases of Milan and Udine. International Journal of Multilingualism 6: 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coluzzi, Paolo, and Riku Kitade. 2015. The languages of places of worship in the Kuala Lumpur area: A study on the “religious” linguistic landscape in Malaysia. Linguistic Landscape 1: 243–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doniger, Wendy. 2014. On Hinduism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Esteron, John Joseph. 2021. English in the Churchscape: Exploring a religious linguistic landscape in the Philippines. Discourse and Interaction 14: 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, Gavin Dennis. 2020. Hindu Monotheism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gorter, Durk, and Jasone Cenoz. 2023. A Panorama of Linguistic Landscape Studies. Bristol: Multilingual Matter. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, J. Randall. 2023. Indianization in Indonesia. Journal of Indian Philosophy and Religion 28: 32–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Chonglong. 2025a. Hindu-scape on Buddhist land: Hinduism represented, recontextualised, and commodified in Bangkok’s linguistic and semiotic landscape. Cogent Arts & Humanities 12: 2559882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Chonglong. 2025b. Scripting English in Jawi: English disguised in Arabic-based ‘Tulisan Jawi’ in Brunei’s linguistic landscape. Asian Englishes 27: 591–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Chonglong. 2026. Visualizing entrenched historical trauma and inherited fear: A linguistic and semiotic landscape account of Jakarta’s traditional Chinatown Glodok. Visual Studies, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Chonglong, and Ibrar Bhatt. 2024. ‘Little Arabia’ on Buddhist land: Exploring the linguistic landscape of Bangkok’s ‘Soi Arab’ enclave. Open Linguistics 10: 20240018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Chonglong, and Paolo Coluzzi. 2024. Presence of ‘ARABIC’ in Kuala Lumpur’s multilingual linguistic landscape: Heritage, religion, identity, business and mobility. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkyns, Sarah, and Monique van den Hoven. 2022. Linguistic Diversity and Inclusion in Abu Dhabi’s Linguistic Landscape during the COVID-19 Period. Multilingua 41: 201–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, Adam, and Crispin Thurlow. 2010. Semiotic Landscapes: Language, Image, Space. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Nathan. 2005. Rediscovering Pancasila: Religion in Indonesia’s Public Square. The Brandywine Review of Faith & International Affairs 3: 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Russell, and Nigel G. Phillips. 1995. Place Names in Malaysia and Indonesia. In Halbband: Ein internationales Handbuch zur Onomastik. Edited by Ernst Eichler, Gerold Hilty, Heinrich Löffler, Hugo Steger and Ladislav Zgusta. Berlin: New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 904–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kallen, Jeffrey L. 2023. Linguistic Landscapes: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kochav, Shlomit. 2018. The linguistic landscape of religious expression in Israel. International Journal Linguistic Landscape 4: 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. 2001. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London: Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri, Nayanjot, and Elisabeth A. Bacus. 2004. Exploring the archaeology of Hinduism. World Archaeology 36: 313–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, Rodrigue, and Richard Y. Bourhis. 1997. Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality: An Empirical Study. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16: 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesmana, Cokorda Bagus J., and Niko Tiliopoulos. 2009. Schizotypal personality traits and attitudes towards Hinduism among Balinese Hindus. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 12: 773–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Jackie Jia. 2016. The Linguistic Landscape of Chinatown: A Sociolinguistic Ethnography. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Manan, Syed Abdul, Maya Khemlani David, Francisco Perlas Dumanig, and Liaquat Ali Channa. 2017. The Glocalization of English in the Pakistan Linguistic Landscape. World Englishes 36: 645–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, June. 2013. A Modern Hindu Monotheism: Indonesian Hindus as ‘People of the Book’. The Journal of Hindu Studies 6: 333–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, Niels. 1983. Abangan Javanese religious thought and practice. Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land-En Volkenkunde 139: 260–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noobanjong, Koompong. 2023. Stylistic Hybridity in Palatial Architecture during the Reign of King Rama V: A Postcolonial Reinterpretation on Modern Siam. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 23: 542–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, Alastair. 2017. Translanguaging and Semiotic Assemblages. International Journal of Multilingualism 14: 269–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanthaphoommee, Narongdej, and Chonglong Gu. 2024. English passing off as Thai in twenty-first century Thai linguistic landscape. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramstedt, Martin. 2011. Colonial encounters between India and Indonesia. South Asian History and Culture 2: 522–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Diego García. 2022. Who are the allies of queer Muslims? Situating pro-queer religious activism in Indonesia. Indonesia and the Malay World 50: 96–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, Iman G., and Zuliati Rohmah. 2018. Contesting linguistic repression and endurance: Arabic in the Andalusian linguistic landscape. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 26: 1865–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sancho, David. 2020. Exposed to Dubai: Education and Belonging among Young Indian Residents in the Gulf. Globalisation, Societies and Education 18: 277–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scollon, Ron, and Suzie Wong Scollon. 2003. Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Guowen, and Xiaofang Yao. 2024. Stylization of history and heritage commodification: The linguistic landscape of refabricated historical streets in Chinese cities. Language & Communication 98: 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Bal Krishna. 2021. The Scarf, Language, and Other Semiotic Assemblages in the Formation of a New Chinatown. Applied Linguistics Review 12: 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shattuck, Cybelle. 1999. Hinduism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Ge. 2022. The Linguistic Landscape of Chinatowns in Canada and the United States: A Translational Perspective. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 45: 3505–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Ge, and Chonglong Gu. 2025. Deciphering Translation Practices in Macao’s Casino Wonderland of Cotai. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starks, Donna, and Nhan Phan. 2019. An Exploration of Stasis and Change: A Park in the Old Quarter Hanoi as a Palimpsest. Social Semiotics 31: 550–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhardjono, Liliek Adelina. 2016. Wayang Kulit and The Growth of Islam in Java. Humaniora 7: 231–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ufen, Andreas. 2009. Mobilising Political Islam: Indonesia and Malaysia Compared. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 47: 308–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kroef, Justus M. 1951. The Hinduization of Indonesia Reconsidered. The Far Eastern Quarterly 11: 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vora, Neha. 2013. Impossible Citizens: Dubai’s Indian Diaspora. Durham: London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Winichakul, Thongchai. 1994. Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of a Nation. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wisarja, I. Ketut, and I. Ketut Sudarsana. 2023. Tracking the factors causing harmonious Hindu-Islamic relations in Bali. Cogent Social Sciences 9: 2259470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldemariam, Hirut, and Elizabeth Lanza. 2012. Religious wars in the linguistic landscape of an African capital. In Linguistic Landscapes, Multi-Lingualism and Social Change. Edited by Christine Hélot, Monica Barni, Rudi Janssens and Carla Bagna. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, pp. 169–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hsin-Min, Saisunee Techasan, and Thom Huebner. 2020. A new Chinatown? Authenticity and conflicting discourses on Pracha Rat Bamphen Road. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 41: 794–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Hong, Michael F. Seilhamer, and Yi Lin Cheung. 2023. Identity Construction on Shop Signs in Singapore’s Chinatown: A Study of Linguistic Choices by Chinese Singaporeans and New Chinese Immigrants. International Multilingual Research Journal 17: 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).