Abstract

Holy Week, the most significant period of the Christian liturgical year, was marked by solemn and complex rituals enacted within the sacred spaces of medieval religious communities. In the case of Cistercian female monasteries, scholarly attention has largely centered on Easter dramatic representations such as the Depositio or the Visitatio Sepulchri, while the official liturgy—Hours, Masses, processions, and the official rituals of the Easter Triduum—has remained comparatively understudied. This article addresses that gap by examining the Holy Week liturgy as performed by the Cistercian nuns of Lichtenthal (Baden-Baden, Germany), on the basis of an exceptional and understudied source: the original Ecclesiastica Officia (mid-13th century, Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, 65/323). Containing comprehensive normative prescriptions for the Easter liturgy adapted for the Lichtenthal community, this manuscript enables a detailed reconstruction of the nuns’ primary collective experiences during these days. The study brings together evidence from architecture, works of art, and liturgical books, while integrating insights from sensory studies, in order to underscore the bodily and multi-sensory dimensions of the rituals. In doing so, it highlights the implications of the nuns’ active participation in Holy Week ceremonies and contributes to a deeper understanding of medieval female religious ritual experience, challenging conventional notions of enclosure and liturgical practice.

1. Introduction: Aims and Rationale

In studies dedicated to female Cistercian spirituality in the Middle Ages, research on Easter paraliturgy—the often-dramatic celebrations not provided for in the canonical liturgy, such as the Depositio and the Visitatio Sepulchri—which were often interpreted freely in individual monasteries, is predominant1. In contrast, those on the ‘official’ liturgy are virtually absent, except in exceptional cases.

This aspect must be linked to the fact that, in more general terms, we know very little about how the Cistercian way of life was applied in the female monasteries of the order. In this regard, as Emilia Jamroziak argues: “in the relatively sparse secondary literature on Cistercian customs for male communities, there is almost a total absence of any discussion of customs in female communities” (Jamroziak 2020, pp. 95–96). This gap in research, which remains significant today, likely stems from the fact that studies on the female Cistercian order in the Middle Ages have had to contend with the complexities of its structure and spread.

Generally supported by aristocratic patrons, only some of the numerous female monasteries that declared themselves “Cistercian” in Europe between the 12th and 13th centuries were recognised by the male General Chapter and thus officially incorporated into the order2. This aspect is crucial because, especially following the organisational planning undertaken by Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153), the Cistercian order became highly centralised in its regulations (Jamroziak 2020). The legacy of his spiritual leadership took the form of a series of principles that became widespread, common, and strongly characteristic of the devotional approach of all the houses officially belonging to the order. Consequently, the functioning of the monasteries and how the communities professed their spiritual life within them needed to be as consistent as possible. However, it is important to consider that the uniformity sought by the direction of the order may have encountered the diversity of individual houses, which could have preserved traces of their local customs in the adaptation of ritual performances.

From the outset, the document Carta caritatis, which established the order and was approved by Pope Calixtus II in 1119, required uniformity in liturgical texts and functions to the extent that to refine and regulate the liturgy with even greater precision, the Latin text of the Ecclesiastica officia was introduced (Choisselet and Vernet 1989, pp. 44–49). This was a service or ordinal book—i.e., a genre of book containing instructions on how to celebrate liturgical ceremonies—taken from the Cluniacs and perfected to address the specific requirements of the Cistercians, which all affiliated houses were required to use3. Now, while the use of this fundamental tool is generally well established and well defined for male foundations, the same cannot be said for female ones. This issue undoubtedly stems from the fact that, for historiography, it remains difficult to establish the differences or correspondences between the so-called incorporated and unincorporated Cistercian nunneries.

In the face of a considerable gap in the literature, David Catalunya’s contribution on the vernacular custom of the Spanish female monastery of Las Huelgas (founded in 1187) is important. It is an adaptation—mainly a synthesis in many parts—in the Castilian vernacular of the Ecclesiastica officia created by the nuns themselves for their internal use (Catalunya 2017). This case has been characterised by a certain exceptionality, just as the monastery of Las Huelgas itself was an exception, whose close and direct connection with the Crown of Castile made it substantially independent from the control of the General Chapter of the Cistercian Order (Jamroziak 2013, p. 133).

This article, however, will analyse a standard Latin copy from the mid-thirteenth century of Ecclesiastica officia (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323)4 from a Cistercian convent in Lichtenthal, Germany, which is still a functioning community in the region of Baden-Württemberg (Figure 1). As was customary, this convent was also of aristocratic origin, managed land holdings, and was connected to the Margraviate of Baden-Baden. In particular, the founder and principal patron of the nunnery was the Countess Palatine Irmengard of the Rhine (c. 1200–1260), consort of Herman V of Baden (d. 1243). Consequently, throughout the Middle Ages, the abbesses and nuns of Lichtenthal were predominantly noblewomen drawn from the most influential families of the Baden region5. Taking advantage of a privilege issued by Pope Innocent IV on 24 July 1245, in 1247 Irmengard succeeded in having the nunnery inspected by a delegation of monks from the General Chapter of Cîteaux, thereby obtaining its formal incorporation into the Cistercian Order (Schindele 1984, pp. 30–31). Following this development, in 1248 Lichtenthal was placed under the spiritual guidance of the male abbey of Neuberg in Alsace, which is believed to have provided the nuns with all the necessary books, including the copy of the Ecclesiastica Officia under examination (Schindele 1984, pp. 31, 46–48).

Figure 1.

Baden-Baden, Lichtenthal Monastery (Creative Commons License—CC0).

This manuscript, which has been largely overlooked, is of extraordinary documentary value for at least two reasons. The first is that it belonged to a female monastery that was officially recognised by the General Chapter and, therefore, constitutes a potentially revealing example of widespread practice, helping to demonstrate that nuns could formally observe Cistercian ritual regulations6. The second is that the standard text of the Ecclesiastica officia intended for monks has been feminised, with certain adjustments to the ritual dynamics that offer valuable insights into the liturgical activities of the nuns.

To provide a better understanding of the contents of the manuscript and offer a comprehensive reading of the actions carried out by the community of Lichtenthal, the main rites of Holy Week, which were the most important of the liturgical year, will be examined. This will enable us to reconstruct the collective ritual experiences of the nuns in detail. This analysis will combine and examine diverse materials, including architectural spaces, works of art, and medieval liturgical books of the monastery, whose contents are closely related to the Eccesiastica officia instructions. At the same time, this paper will incorporate insights on the sensory experiences lived by the monastic community of Lichtenthal. Through this approach, this article will emphasise the bodily and multi-sensory engagement of the nuns in the rituals, highlighting the implications of their active participation in the main liturgical ceremonies of Holy Week.

2. The Spaces of the Church and Monastery

To gain a better understanding of the liturgy of Holy Week in Lichtenthal, it is essential to describe the setting in which it took place, namely the architectural structures of the monastery and its layout. First, following the order’s regulations on the establishment of monasteries, a secluded area in the Black Forest, next to a river (the Oos), was chosen for the foundation7. This aspect is indicative of the fact that, as will be seen, apart from the priests who performed the ritual services, only a small audience of aristocrats and laywomen had access to the liturgical celebrations.

The church was consecrated in 1252 but was subsequently renovated, raised, and lengthened in the Gothic style as early as 1300, to the extent that a second consecration took place in 13228 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Lichenthal Monastery (Baden-Baden). Interior of the church (photo taken by the author in 2022).

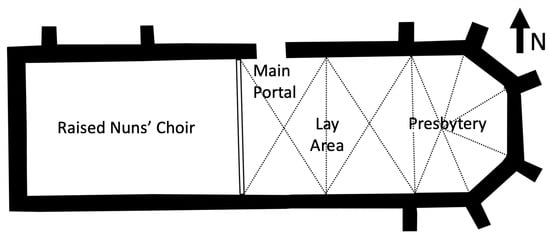

Apart from the modifications and modernisations that have taken place over the centuries9, the current division of the liturgical spaces reflects the original spatial arrangement and therefore allows for a basic reconstruction of the medieval period (Figure 3). The hall has a single nave facing east and ending in an apse 5/8 of the same width, at the back of which, in the Middle Ages, the high altar, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, was probably located, with two smaller side altars, the one on the right dedicated to John the Baptist and the one on the left to John the Evangelist (Coester 1995, pp. 88–89). In front of the presbyterial area, which was presumably well delimited at the time, was the area reserved for the laity, corresponding to the two cross-vaulted bays and directly accessible from the main portal of the church on the north side.

Figure 3.

Baden-Baden, Lichtenthal Monastery. Reconstruction of the medieval church’s plan, including its liturgical spaces (author’s plan).

Beyond this space, the nuns’ choir began on a raised gallery, which was considerably extended in length. The floor stretched 28 m towards the western side of the building, and the ceiling was a wooden barrel vault until the 18th century10. The choir on a tribune was entirely in line with the most common practice in Cistercian churches for women in Germany11. The present one is therefore in the same position as the original one but is shorter towards the presbytery because it was reduced in 1811 to enlarge the area below for the faithful (Stober 1995, p. 111) (Figure 4). Initially, it probably had a parapet or dividing wall at the end of the second vaulted bay on the east side and was accessible from the nave via a staircase against the south wall of the church.

Figure 4.

Baden-Baden, Lichtenthal Monastery. Interior of the church, view of today nuns’ choir towards west (photo taken by the author in 2022).

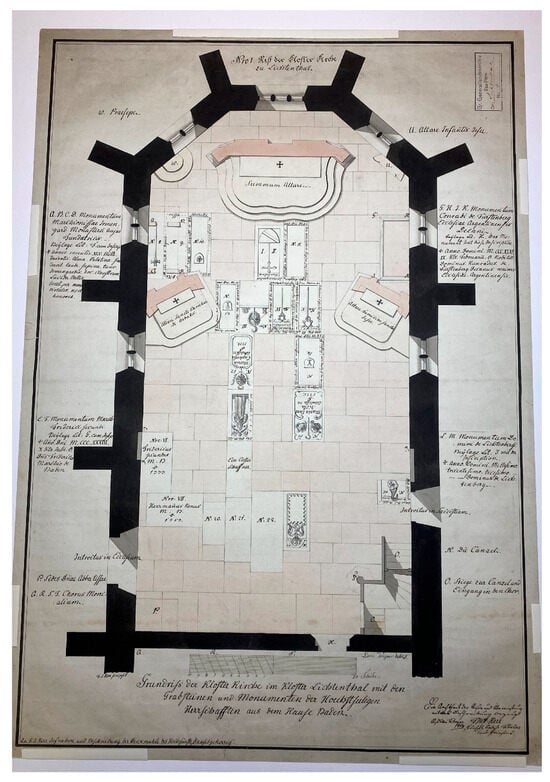

This structure, renovated over the centuries with the addition of a pulpit, must have been similar in function and position to the one shown in an 1804 plan by Franz Josef Herr (Figure 5). We cannot determine whether this drawing actually represented the medieval staircase, but it is useful for understanding how the choir was connected to the nave from the Middle Ages onwards. In fact, it still features the hexagonal pulpit, now located to the left of the presbytery, which in 1606 had been set on the medieval floor and was therefore of a height proportionate to the nuns’ choir12.

Figure 5.

Franz Josef Herr, drawing of the nave of Lichtenthal Church (1804)—Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv (General Archive of Baden-Württemberg), G Lichtenthal 1.

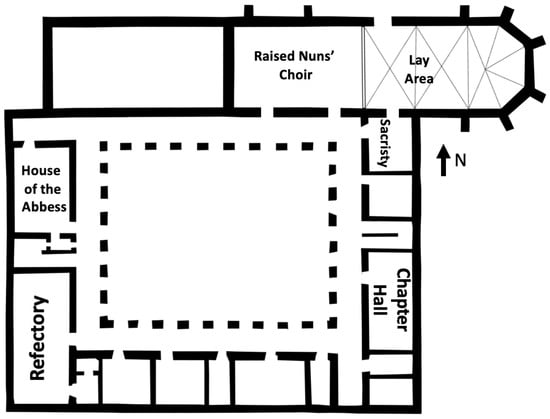

Now that the layout of the church’s liturgical spaces has been clarified, it is necessary to understand how it connected to the cloister and its rooms (Figure 6). The medieval monastery building was gradually demolished and completely renovated by architect Peter Thumb beginning in 1726 (Stober 1995, pp. 99–101). However, the new construction retained the original division of the main common areas, which in turn respected the Cistercian custom of positioning the cloistered rooms13. On the ground floor, along the east wing were the sacristy and the chapter house, along the west wing were the refectory and the abbess’s residence. The second floor, to the east, was used as an archive and dormitory, while to the west, it served as a common room and library14. Furthermore, in 1925, along the south wall of the church—that is, the one bordering the cloister—three medieval doors were identified: the sacristy door, roughly opposite the main portal, and two at the two ends of the nuns’ choir area (Coester 1995, pp. 87–88). The latter gave access to the room below the raised tribune (which was maybe reserved to the converses), where there was probably another staircase leading up to the choir.

Figure 6.

Baden-Baden, Lichtenthal Monastery. Plan (author’s ground floor plan).

To conclude this introductory section, it should be noted that Lichtenthal was the main burial and memorial site for the Margraves of Baden and members of the aristocratic elite connected to them, as can be seen from the numerous tombs—removed or relocated in the late 19th and 20th centuries—depicted in Herr’s 1804 drawing mentioned above (Figure 5). In the Middle Ages, the Countess Irmengard of the Rhine (c. 1200–1260), founder of the monastery, was buried in front of the high altar, while in 1288 her son Rudolf I had the ‘Princes’ Chapel’ built next to the north side of the church, which became the burial place of generations of margraves (Schwarzmaier 1995; Krimm 1995; Tramarin 2024, pp. 187–90) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Baden-Baden, Lichtenthal Monastery. External view of the ‘Prince Chapel’ facade connected to the north side of the church nave (photo taken by the author in 2022).

This association with the nobility had a particular impact on the representative role of the sacred spaces and the ritual and liturgical practices of the community and its members. This suggests that participation in the celebrations held at Lichtenthal was exclusive and is clearly a highly significant factor to bear in mind when seeking to understand the dynamics of the liturgical activities that took place in the spaces described above.

3. The Holy Week in Lichtenthal

The origins of the Christian cult coincided with the commemoration of Christ’s death and resurrection. Therefore, over the centuries, the liturgical year was defined around Easter as the centrepiece of the Christian faith based on the Story of Salvation (Righetti 1955, pp. 141–44; Borgehammar 2001, pp. 13–19, 31–35). Consequently, the liturgy of Holy Week assumed a crucial role in commemorating the Gospel events relating to the last days of Christ, developing over the centuries into unique celebrations, including performances.

It is difficult to identify a standard and uniform picture of the practices that characterised the rituals of those days in the medieval West, especially between the 11th and 13th centuries, because they were marked by an extraordinary and varied spiritual evolution. Within this variety, the Cistercians certainly stand out as a highly interesting and emblematic religious group. While retaining and observing the Rule of St. Benedict with absolute rigour, the order developed its own version of the Gallican rite, which over time came to be specifically considered the “Cistercian rite,” remaining unchanged until the Council of Trent15.

What distinguishes the Ecclesiastica officia from many other types of customary books is that they are essentially the same for all houses of the order (Choisselet and Vernet 1989, pp. 44–49; Jamroziak 2020, p. 88). Moreover, the liturgy is described with care and clarity. It is therefore possible to examine in detail all the actions, times, gestures, chants, and prayers, as well as the vestments, objects used, and the relationship of the religious community with the architectural spaces. In this regard, according to Bernard of Clairvaux, the synthesis between community, liturgy, and the sacred building gave rise to a unique unity that renewed the history of salvation and the historical identity of the Church (Lia 2007, p. 148). In Cistercian spirituality, therefore, the realisation of the divine mystery was relived in each instance through the performance of the rite in space, based on a disciplined definition of the acts and movements performed both by the entire monastic community as a single, coordinated body and by the bodies of the individual religious members.

In short, in the sacredness of the liturgy, the use of the body took on a totalising function for the Cistercians. This aspect had been determined by Bernard’s theological conception of the relationship between human beings and God. In fact, he reinterpreted the dogma of the incarnation, death, and resurrection of Christ in terms of an emotional relationship, placing a strong emphasis on the bodily correspondence with Christ, who died, rose again, and ascended to heaven. As a result, in addition to the spirit as a transcendent element, the body and its senses became effective instruments of expression of love for Christ and, therefore, of knowledge of God16.

The spirituality of the Cistercian order was strongly Christocentric, and this was true for both monks and nuns, who shared a powerful identification with Mary as the embodiment of the pure soul characterised by obedience, intercession, and love (Bynum 2008, pp. 179–81). As the epilogue to the Story of Salvation revealed by Christ, Holy Week was thus the period in which the liturgical experience became most intense on the physical and sensory level. The Ecclesiastica officia of Lichtenthal, therefore, allows us to gain a deeper understanding of how the Cistercian nuns might have experienced this.

3.1. The Procession of Palm Sunday

The first day, Palm Sunday, is particularly indicative of how the procession before Mass is conducted. For obvious reasons, the celebration was presided over by a priest, who acted in a supporting role. He began the day by performing an exorcism of the water; thereafter, the soror hebdomadaria—i.e., the nun who presided over the offices for a week at a time—was to begin the recitation of the divine office at the third hour (corresponding to approximately 9 a.m. in modern time), followed by the rest of the community17. After the prayer, the actual preparations for the Palm Sunday procession began. Although dated 1467, a small processional book from the Lichtenthal library, now preserved in Karlsruhe (Karlsruhe, Badische Landesbibliothek, L53), contains rubrics and chants that coincide precisely with the indications in the Ecclesiastica Officia and thus allows us to clarify and confirm the analysis of the actions and logistical movements carried out by the nuns within the monastery18. At the same time, given its date, the manuscript demonstrates that the manner in which the procession was carried out remained unchanged between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries.

A detail from the famous illuminated manuscript containing La Sainte Abbaye by Pierre de Blois helps visualise how these small books were used and their ceremonial role (London, British Library, Yates Thompson 11, f. 6v) (Figure 8). Dated between 1290 and 1300, this manuscript probably comes from Maubuisson, a Cistercian nunnery under the patronage of the French crown, founded in 1236 by Blanche of Castile (Stones 2014, pp. 98–103). In the illustration, the nuns are the only ones holding open processional books. They accompany the procession with their singing, and, as we shall see, a similar dynamic can be assumed for Palm Sunday in Lichtenthal.

Figure 8.

Detail of a procession in La Sainte Abbaye—1290–1300, London, British Library, Yates Thompson 11, f. 6v (Creative Commons License—CC0).

At the beginning of the ritual, the priest would bless the branches by sprinkling them with Holy Water. Meanwhile, the antiphon Pueri Hebreorum—included in the processional—was sung twice by a nun soloist. This chant evoked the gathering of the crowd in Jerusalem who, holding olive branches in their hands, went out to meet Christ and welcome Him. It is therefore no coincidence that, at the moment, the secretary and her assistant distributed the branches inside the church to the abbess, the members of the community, to the familiares, and lay guests “if present.”19 This last detail is particularly interesting. From the last decades of the 12th century onwards, lay groups linked to individual Cistercian foundations were referred to as familia. These were generally major benefactors who were affiliated with the order, obtaining privileges of prayer for themselves and their deceased relatives on the one hand, and playing a role in the economic activities of the individual foundations on the other20. In the case of Lichtenthal, it is reasonable to assume that the familiares were the margraves and/or other aristocrats in their circle. Therefore, the distribution of the branches likely signified a moment of direct contact and interaction in the nave of the church with the nobles associated with the monastery.

Once ready, the procession would then leave the church while the soloist intoned the antiphon Occurrunt turbae. This chant emphasized the solemn beginning of the processional movement, recalling the continuous arrival of the people who came to witness and honor the coming of Christ. Two nuns would have stood at the head: one with the processional cross, the other with a bucket of holy water. They were then joined by the rest of the nuns, following the established choir order21, with the abbess positioned immediately after the novices at the rear. The community would then proceed to the cloister, and the prioress was responsible for ensuring that nothing inappropriate was inside22. Furthermore, an addition on the left margin of folio 15v prohibits female guests from entering both the processions held in the cloister and the sermons in the chapter house23.

In keeping with this, the processional indicates that the exit from the church had to be accompanied by the aforementioned antiphon. The next one, Collegerunt pontifices, was sung until the first stop in the cloister near the dormitory (since the dormitory was on the second floor, it is likely that the nuns stopped at the entrance to the stairs in the east wing or climbed them)24. The verses of this antiphon, which recalled the pivotal moment when the religious leaders of Jerusalem began to fear Christ’s growing influence upon witnessing such a large gathering of people, significantly marked the circuit around the cloister. Through their singing the community would have introduced the events of the Passion that were to unfold in the following days. Hence, the soloist would have intoned the verse Unus autem ex ipsis Caiphas nomine and the procession would have resumed towards the second stop in front of the refectory entrance. From there, repeating the verse Quid facimus, quia hic homo multa signa facit? (What are we to do? This man is performing many miraculous signs), the procession would have returned towards the church, thus completing the tour of the cloister to stop and arrange itself at its entrance25. Here began the most solemn and intense phase of the Palm Sunday rite, which deserves to be entirely presented in the main text.

Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, f. 15r: Et in unaquaque statione sorores quae ferunt aquam er crucem habeant vultus suos versos et crucem versam ad cumventum et in ambulando et in stando soror que fert aquam sit ante crucem. Porro in ultima statione incipiente cantrix antifona Ave Rex Noster inclinetur ad crucem cumvento manibus in terram postis et omnis erecte deinceps stent cum vise ad crucem usque incipiatur Gloria laus et honor. Interea dum haec antifona Ave rex noster canitur, secretaria analogium quod ipsa ante terciam in capitulo collocavit cum textu evangelium ad locum ubi evangelium legendum est hoc est ante hostium ecclesiae deferat. In circa finem itaque antedicte antifone Ave Rex noster stans contra orientem evangelium legat. Sorores que ferent f. 15v crucem et aquam ante eam stent et ad cumventum vultos suos versos habeant. Tunc etiam cunventus stet versis vultibus ad invicem. Due autem sorores que tam a cantrice premonite esse debent post evangelii lectionem ecclesiam intrent et iuxta hostium stantes visa facie ad processionem versus Gloria laus uti in libro ordinati sunt canantur. Quibus finitis ab eisdem sororibus principio eorundem versum repetito gloria laus revertantur ad processionem et stent in ordine suo. His igitur peractis imponat abbatissa responsorium Ingrediente domino ad ecclesiam omnes illud cantando intrent. Ramos quoque quos gestant mox ut in chorum venentur super scrinias deponant quos secretaria continuo auferat. Postea missa celebretur./And at each station the sisters who carry the water and the cross shall keep their faces turned toward the community, with the cross likewise turned toward it; and while walking or standing, the sister who carries the water shall stand in front of the cross. Moreover, at the final station, when the chantress begins the antiphon Ave Rex Noster, all shall bow toward the cross, with their hands placed upon the ground; and thereafter they shall remain upright, facing the cross, until Gloria laus et honor is begun. Meanwhile, while the antiphon Ave Rex Noster is being sung, the secretary shall bring the lectern, which she had previously set up in the chapter room before terce with the text of the Gospel, to the place where the Gospel is to be read, that is, before the doors of the church. And toward the end of the aforementioned antiphon Ave Rex Noster, standing and facing east, she shall read the Gospel. The sisters who carry the cross and the water shall stand before her, with their faces turned toward the community. At this moment, the whole community likewise shall stand, facing one another. Then, two sisters—who must be previously instructed by the chantress—shall, after the reading of the Gospel, enter the church and, standing by the doorway with their faces turned toward the procession, shall sing Gloria laus as it is appointed in the book. When this has been completed, and the same sisters have repeated the opening verse of Gloria laus, they shall return to the procession and take their place again in proper order. When these actions have been completed, the abbess shall begin the responsory Ingrediente Domino, and all shall enter the church while singing it. As soon as they come into the choir, the branches which they carry shall be laid in chests, which must be promptly removed by the secretary. Thereafter, the Mass shall be celebrated.”

The final station beside the church is thus characterized by an atmosphere charged with anticipation, in which gestures, attitudes, and liturgical postures are imbued with profound solemnity. At first, in particular, the focal point of collective devotion was the processional cross, symbol of the forthcoming Passion and Sacrifice of Christ. Immediately afterwards, with the singing of Gloria laus et honor, the community would thus express its praise of Christ as the King of Salvation.

The entire sequence emphasized and prepared for the decisive moment of entering the church, marked by the abbess’s intonation of the responsory Ingrediente Domino. At that moment, the nuns solemnly re-enacted Christ’s entry into Jerusalem, which was the ultimate and most imaginative goal of the celebration. The space of the church, therefore, symbolised the Holy City, glorifying the arrival of the Lord. Therefore, the nuns’ collective movement between the cloister and the church re-enacted the content of the Gospels through a dialogue with the surrounding architectural spaces, which served as sacred backdrops for the rite. At the same time, the chanting gave rhythm to the movements, gestures and solemn actions of the entire community. Everything was performed collectively by the nuns as if they were a single body, disciplined and guided by precisely described postures, as previously noted. Moreover, it is essential to emphasise that, for medieval religiosity, the union of music and bodily movement in the liturgy had a profound spiritual meaning. This conception was born from Augustine, for whom this dynamic led man to merge into divine harmony (Diehr 2000, pp. 29–35). With its reform of the Cantus firmus, the Cistercian order sought to refine the liturgy to pursue the same intent. Furthermore, Bernard of Clairvaux regarded music as fecundating—that is, a generative force capable of embodying the divine beauty and giving life to the meaning of God’s word (Lia 2007, pp. 345–49).

It should also be noted, as Gisela Muschiol observed, that since the time of Gregory the Great, the prayer of virgins was believed to be especially effective given that, in his view, its purity allowed for a greater proximity to God (Muschiol 2008, p. 195). In this sense, with their singing, the nuns would therefore have acted as mediators for all those present at the ritual, i.e., the familiares.

3.2. Maundy Thursday

As Holy Week continued, the liturgical actions performed by the nuns on Holy Thursday took on a highly significant meaning. On that day, after the first hour—that is, after dawn—a single Mass was celebrated in commemoration of the Last Supper, the fundamental event of the Institution of the Eucharist26. During this Mass, everyone was to have access to the Exchange of Peace and Communion, with indications that the priest should prepare a sufficient number of hosts for the liturgy of Good Friday27.

It is possible to reconstruct with reasonable accuracy how the nuns participated in the rite. In the general prescriptions for Mass, the Ecclesiastica officia of Lichtenthal specifies that communion was to be administered to them after the peace through a “window”28. Clearly, this shows that, during the celebration, the community had to remain separated within the choir, in accordance with the customary cloistered practices of female monasteries29. As we have seen, this space was located on a raised platform in the nave, opposite the presbytery and the high altar. This arrangement, therefore, limited the full perception of such a crucial rite, because it resulted in a ‘distant’ presence and participation in the place and moment of the reenactment of the Last Supper and the Eucharistic consecration.

A liturgical object from Lichtenthal suggests several points for reflection regarding this last assumption. It is possible that, at least during the 14th century, the tabernacle now preserved at The Morgan Library & Museum (Figure 9) was used for these celebrations. The work, made in Speyer, is among the finest examples of goldsmithing in the Middle Rhine region in the late Middle Ages. An inscription on the lid indicates that it was commissioned by Sister Greda, who had already taken her vows as a nun in Lichtenthal by 130530.

Figure 9.

German workshop (Speyer), Lichtenthal Tabernacle (after 1305). Silver gilt, with blue, green, gold and purple basse-taille enamel (16.5 × 19.1 × 13.7 cm). New York, The Morgan Library & Museum, Inv. AZ048 (Courtesy of The Morgan & Library Museum).

Interestingly, she is depicted twice: the first time on the hinge side, shown in adoration alongside the three Magi, who are paying homage with their gifts to the Child seated on the Virgin’s lap, with St. Bernard of Clairvaux at her side; but, above all, in the second, Greda appears on the lid inside the scene of the Last Supper, kneeling to the right of the table, while Bernard appears again on the opposite side. Consequently, if the hypothesis is correct that the tabernacle donated by Greda was used at that time, the nun would have had a privileged position through her representation. As a sacred work placed in a holy space in the late Middle Ages, the proximity of the donor’s image went far beyond simple figurative boundaries. Drawing on Caroline Walker Bynum’s reflections on the material perception of sacred art in medieval Christianity (Bynum 2015a, pp. 53–58), it is plausible to argue that, on the one hand, the object had the power to manifest concretely—and not to symbolize—the presence of God, and on the other hand, that images of the Epiphany or the Last Supper were not considered illustrations of the Gospel episode but vehicles for their actual evocation. Furthermore, and more importantly, as a tabernacle, its materiality contained and was in direct contact with the body of Christ. Thus, to be effective devotionally, the image of Greda was not a simple portrait inserted into the scenes but acted as a physical connection with her person.

Therefore, well beyond the evident desire to be remembered for her commission, the nun had secured a position of closeness to the Eucharist in a strictly ‘physical’ sense, even compensating for the actual distance of her body during the liturgy. From this point of view, the portrait of Greda was a significant individual privilege, since the monastic community had to remain confined to the choir during Mass, from whose raised platform it was difficult to have a complete view of the Eucharistic consecration on the high altar31. This concept can be also aligned with the fact that, as demonstrated by Fiona Griffiths, textiles produced by women for the altar provided them with a mediated form of access to the celebration of the Eucharist (Griffiths 2011).

Moreover, in more general terms, Greda’s depictions represent an intriguing case within the broader function of medieval portraiture, which frequently served as a means of enhancing self-awareness and emphasizing a distinctive role among a community32. Lastly, it is worth emphasizing the presence of Bernard of Clairvaux in both scenes. His representation may have been motivated not only by his central role within the Cistercian Order but also by a mediating function as a male religious figure, reflecting an iconographic pattern already observed in depictions of nuns within the art of late medieval female monastic contexts33.

The nuns resumed their collective role in the reenactment of the Washing of the Feet, known in Latin as the Mandatum. As today, the ritual was an integral part of the liturgy of Holy Thursday and had been made mandatory for priests and bishops since the 17th Council of Toledo (694) (Righetti 1955, pp. 169–70). During the Middle Ages, within monasteries, it took on a two-part form: the Maundy of the Poor and the Conventual Maundy (Yardley 2012, p. 169). In this regard, the detailed prescriptions contained in the Monastic Constitutions of Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1070 to 1089, served as a model for their execution34. The actions included in this text were reproduced in a very similar manner in the Ecclesiastica officia of the Cistercians, and the Lichtenthal version shows how the female communities performed them in essentially the same way as the male ones. The rite included numerous significant details and warrants a lengthy transcription:

Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, ff. 16v-18v […] Post sextam horam portaria, nisi altera ab abbatissa iussum fuit, tot pauperculas eligat, quot sorores sunt in cenobio. Has omnes postquam suscepte fuerint a monachabus ut mos est a ceteris sequestratas in una parte manere faciat donec ad mandatum ducantur. Et interim dum nona cantatur indocta laica adiutrix monache hospitalis et cetere indocte quas celleraria advocaverit, ducant pauperculas per claustrum ibique eas sedere et discalciari faciant; incipientes ab hostio ecclesiae quo monache exire et claustrum intrare solent. Vasa et linthea seu terforia ad mandatum necessaria, aquamque calidam illuc deferant et omnia ordinate disponant, quae vasa et cetera necessaria celleraria provideat. Dicata vero hora nona exeat sorores de ecclesia incipentes a prioribus eo ordine quo vadunt in capitulum, ita ut abbatissa omnes transeat pauperculas usque ad ultimam et mandatum faciant in claustro pauperculis. […] et postquam abluerint et exterserint et osculate fuerint paupercularum pedes monachae proprias manus lavent. Hoc expleto a singulis monachabus singuli nummi dentur pauperibus, qui denarii flexis genibus sunt dandi et manus osculande pauperum. Postea vero se erigant sorores iterumque veniam ante pauparculas petentes dicant “Suscepimus Deus misericordiam in medio templi tui”. […] Deinde deducantur pauperculae ad cellam hospitium, ubi Abbadissa omnium fundat aquam in manibus ac postea reficiant. Et sciendum quod omnes supervenientes hospites hac die pro reverentia dominici mandate karitative sunt reficiendi. Vespera itaque tabula signetur lignea et ipsa hora alte cantetur uti aliis diebus. Abhinc non pulsetur campana usque ad missam in vigilia Paschae. […] Postquam servities a mensa surrexerint sorores que ipso die in capitolo ad mandatum illius diei per tabulam sunt vocate, aquam calidam quam ipsimet antea calefacere debent, in claustrum deferant. […] Deinde sacrista tabulam ad mandatum percuciat. Sororum quoque cunventu in claustro residente ac priorissa locum abbatisse tenente incipiat cantrix antiphonam “Dominus Iesus” praesentibus infirmis que adesse poterunt. Tunc abbadissa et coadiutores sui lintei praecincti, lavent, tergant, et osculentur pedes omnium, ita ut duodecim tantum, id est quatuor monacharum, quatror noviciarum, et quatror sororum laicarum pedes lavet. […] […] Ad collacionem autem lectio evangelii scilicet ante diem sestum paschae legatur sedente sicuti aliis diebus, cuius lectionis finis in providentia est abbatissae. Hinc completorium remissius mediocri voce dicatur, ita tamen ut sonus psalmodie clare et distincte resonet. Quod etiam abhinc omnibus horis in psalmodia et cantu, exceptis Vigiliis et laudibus usque ad Versperam Paschae fiat. […]/After the sixth hour, the portress—unless another has been appointed by the abbess—shall choose as many poor women as there are nuns in the convent. Once the nuns have welcomed them according to custom, they shall be separated from the others and kept in a separate place until they are led to the washing ceremony. Meanwhile, while the Ninth Hour is being sung, an uneducated lay woman, assistant to the nun in charge of the hospital, and others summoned by the cellarer, shall lead the poor women through the cloister and there make them sit down and remove their shoes, beginning at the door of the church from which the nuns usually exit to enter the cloister. The cellarer shall provide the containers, cloths, or towels necessary for washing, as well as hot water, arranging everything in order. The cellarer shall provide these necessary utensils and materials. At the ninth hour, the nuns shall leave the church, beginning with the prioress, in the same order in which they enter the chapter, so that the abbess passes in front of all the poor women until the last one and washes the poor women in the cloister. […]. After the nuns have washed, dried, and kissed the feet of the poor women, they shall wash their own hands. Once this is done, each nun shall give a coin to each poor woman, offering it on her knees and kissing their hands. Then, the nuns shall rise and, asking forgiveness before the poor women, say: “We have received, O God, your mercy in the midst of your temple.” […] Then, the poor women shall be led to the guest dormitory, where the Abbess shall pour water on their hands and then give them refreshment. It should be noted that all guests who arrive on this day must be charitably refreshed in honour of the Lord’s command. At Vespers, the wooden table shall be sounded, and at that hour, there shall be solemn singing as on other days. From this moment on, the bells shall no longer be rung until the Easter Vigil Mass. […] After the servants have risen from the table, the nuns who have been assigned to the chapter on that day shall bring hot water (which they have heated themselves) to the cloister. […] Then, the sacristan shall strike the table for the mandate. When the community is gathered in the cloister and the prioress takes the place of the abbess, the cantor shall begin the antiphon “Dominus Iesus,” with the infirm nuns present, if they are able to participate. Then the abbess, with her assistants and her hips wrapped in towels, washes, dries, and kisses the feet of all twelve: four nuns, four novices, and four lay sisters. […] For collation [evening reading, ed.], the Gospel of the day before Good Friday is read, remaining seated as on other days. The abbess determines the end of the reading. After this, the Compline is said in a softer voice, but in such a way that the sound of the psalmody resounds clearly and distinctly. From now on, this shall apply to all the Hours in psalmody and singing, except for Vigils and Lauds, until Easter Vespers. […]

The main adaptation to be noted is, first of all, the fact that the entire rite was performed exclusively by women, among women, and for women. The explanation for this clear gender separation seems obvious, but it is nevertheless significant. The statutes of the General Chapter strictly prohibited women from entering the male Cistercian precincts to avoid the risk of sexual transgressions35. The prescriptions for the Mandatum of Lichtenthal clearly reflect the opposite consequence of this regulation. Still, it should be remembered that the indications relating to Palm Sunday examined above suggest the possible presence of laymen. This discrepancy can be explained by considering the spaces in which the liturgy took place. In fact, the distribution of the “remaining part” of the branches “to the lay brothers, the familiis, and guests” took place in the church, because the nave was the only space open to the public. In contrast, during the processions in the cloister, not even female guests were allowed to be present.

In its specificity, the Maundy of the Poor thus became a particular exception of its ‘openness’ during the liturgical year. To understand the spiritual value of this circumstance, it is necessary to consider the fundamental meanings attributed to the architecture of the cloister by Bernard of Clairvaux. As a dynamic element connecting the flow of monastic life between the spaces of prayer and work, its square shape became a metaphor for the constant unfolding of human existence in the world, which in turn found its eschatological fulfilment in the abbey church as a place of union with God (Lia 2007, pp. 385–429). Consequently, the opening of the cloister to poor girls became an opening of the monastic community to humanity. Again, according to Bernard of Clairvaux, Cistercian spirituality was to honour God through charity and poverty, both through the lifestyle of the monastic communities and through attention to the poor36. Having a ‘beneficial’ nature in itself, since each participant received a coin and a meal, the Maundy of the Poor thus became the highest liturgical sacralisation of this foundation each year.

It should be noted that the poor women had to be selected by the portress (i.e., the nun responsible for supervising the monastery gate). This suggests that every year, a group of people, probably from the surrounding countryside—and therefore from the lands administered by Lichtenthal—would arrive at the monastery entrance on Maundy Thursday. Once the preparations were complete, after the ninth hour (i.e., at 3 p.m.), during the orderly ceremonial entrance led by the two prioresses and the positioning of the community in the cloister, the abbess had to pass in front of all the poor women, presenting herself to them as a sign of welcome. Immediately afterwards, the Mandatum began. As was customary in every monastery, each nun would wash, dry and kiss the feet and hands of the guest assigned to her, after handing over the coin. However, unlike the overmentioned Lanfranc’s Costitutionis and other subsequent attestations, the Ecclesiastica officia does not provide for any singing for the Maundy of the Poor37.

The kisses and liturgical genuflections, which expressed veneration and humility through bodily movements38, took place in silence. This silence was interrupted—and consequently emphasised—only at the end of the foot washing, with the affirmation: “We have received, O God, your mercy in the midst of your temple”, which does not appear in Lanfranc’s text39.

The liturgical chant was performed from the beginning of the Conventual Maundy, accompanied by the intonation of the antiphon Dominus Iesus, as it evoked Christ’s act in the Gospel. In fact, after the recitation of Vespers (at sunset) and at the end of the supper, the community gathered again in the cloister and it was the abbess’s duty to wash the feet of twelve women (four nuns, four novices and four lay sisters). However, it is important to note that, once Vespers had been solemnly performed, the bells were not to ring again until the Easter Vigil, and even prayers and hymns were to be recited in a subdued manner, including Conventual Maundy.

It is possible to reconstruct the entire sequence of antiphons recited by the nuns during the ceremony, because the antiphonary provided to Lichtenthal by the monks of Neuberg in the mid-13th century after the official entry of the foundation into the Cistercian order has been preserved40. The section referring to the Mandatum appears consistently after the chants that were to be performed for Vespers, and a total of sixteen antiphons were planned, in the following order: Dominus Iesus; Postquam surrexit Dominus; Si ego Dominus; Vos vocatis me magister; Mandatum novum; In diebus illis mulier; Maria ergo; Domine tu michi lavas pedes; Caritas est summum; Ubi est caritas et dilectio; Exemplum praebuit suis discipulis; Diligamus nos; Ubi fratres; Congregavit nos Christus; Maneant in nobis spes fides; Benedicat nos deus deus41. These are all among those most frequently used for the Mandatum, except for the last one, which was used primarily on Trinity Sunday42. In addition, another antiphonary from Lichtenthal, probably produced in the monastery itself after 1318 and still in use there during the 18th century, reproduces the same sequence, suggesting that it was likely preserved over the centuries for use in the rite43.

In concluding the analysis of this rite, it should be emphasized that it is very difficult to identify studies on the Maundy ceremony in medieval female monasteries that allow for meaningful comparison. Fortunately, Anne Bagnall Yardley’s study on Barking Abbey lends itself well to this purpose. Focusing primarily on the analysis of the chants, the scholar demonstrated that in this Benedictine foundation the nuns had personalized the Maundy of the Poor in order to reenact Mary Magdalene’s washing of Jesus’s feet (Yardley 2012, in part. pp. 172–77).

This was not the case at Lichtenthal, where, as we have seen, chants were prescribed only for the Conventual Maundy, following the selection provided by the male abbey of Neuberg. More importantly, the performance of the Maundy of the Poor at Lichtenthal seems to show that the nuns acted consciously as a community to embody the Cistercian principles of charity and care for the poor.

At the end of the Conventual Maundy, the Gospel of the day was read, and Compline was celebrated (probably in the choir), maintaining a subdued tone. The moment of dismissal for repose marked the beginning of the most sombre and sorrowful phase of Holy Week.

3.3. The Adoration of the Cross of Good Friday

As is well known, for Christianity, Good Friday commemorates the passion and crucifixion of Jesus Christ: in Latin, Parasceve Dominus noster Jesus Christus crucifixus (Righetti 1955, p. 170). The first action performed by the nuns after Lauds was highly significant: the Ecclesiastica officia indicates that they had to remove their shoes in the dormitory and, henceforth, remain barefoot—as will be seen—until the end of the liturgy scheduled for the Adoration of the Cross44.

This was a highly significant act, common among monastic orders. However, in the Christocentric spirituality of the Cistercians, it went far beyond the clear expression of penance and humility45, because physical perception itself took on a specific devotional connotation for the religious of the order. It was the day of Christ’s bodily sufferings, and through this feet exposure, expressed and experienced by the nuns on the cold floor, a symbiotic dialogue with the humanity of Christ was emphasised in anticipation of the Resurrection46. The bare feet in contact with the ground revealed the mortal and earthly dimension of the body but at the same time allowed them to stand upright. Bernard often emphasised this latter aspect in his sermons to underline the natural predisposition of human beings to ascend towards God in contrast to the curvature of animals47.

The preparation for the collective Adoration of the Cross—the liturgical climax of the day—was likely preceded by several hours devoted to retreat and individual meditation. In fact, after the recitation of the hymn Iam surgit at the third hour, the nuns were left free until the ninth hour, when the liturgical office began, culminating in the Adoratio crucis48.

The silence was broken by the sounding of wooden boards calling the community to gather in the choir of the church for the start of the rite. A priest, also barefoot, made his entrance at the high altar, covered with clean tablecloths and flanked by two candles (the only ones that could be lit)49. At the end of the liturgy of the word (the euchological service), a large linen cloth was spread out where the adoration was to take place, and two priests or clerics dressed in white, without stoles or maniple, carried the covered cross in front of the steps of the high altar, not holding it but resting it on the steps50.

This marked the beginning of the most dramatic part of the liturgy, culminating in the unveiling and display of the crucifix. After a moment of reflection, the two officiants knelt in reverence, on the right and left sides of the cross, to intone the Improperia, or the reproaches that Christ was imagined to have addressed to the Jewish people, the first verse of which was: Popule meus, quid feci tibi? Aut in quo contristavi te? Responde michi! Quia eduxi de terra egipti parasti crucem salvatori tuo (My people, what have I done to you? In what way have I wronged you? Answer me. I brought you out of Egypt and you prepare the cross for your saviour?). From within the choir, two nuns responded to each verse by singing in Greek and kneeling, Hagios o Theos, Hagios Ischyros, Hagios Athanatos, eleison hymas (Holy God, Holy Mighty One, Holy Immortal One, have mercy on us), followed by the entire community, which recited the exact words in Latin, Sanctus Deus, Sanctus Fortis, Sanctus Immortalis, miserere nobis51.

The provisions of the Ecclesiastica officia are found to be precisely adopted in the rubrics and text of a liturgical manuscript used for the celebration of the Adoratio crucis at Lichtenthal, namely a gradual dating from the mid-fourteenth century52.

Once again, the knowledge of the layout of the church’s interior spaces facilitates the reconstruction of the liturgical experience. The actions performed within the presbyterial area were completed by an intense liturgical dialogue, consisting of an exchange of physical and sound gestures, but performed at a distance and only audible, while the voices of the nuns spread from the raised choir loft. The rite thus created an emphatic atmosphere that reached its climax with the conclusion of the Improperia and the singing of the antiphon Ecce lignum, during which the two officiants unveiled the cross on the presbytery and the sacristan unveiled other crosses53.

At this point, the Ecclesiastica officia of Lichtenthal stipulates that what was performed by clerics or priests must be done in the same way by two nuns inside the choir in front of the altar step.54 This clarification is the main and most significant adaptation made to the rite compared to the male version, in which the monks worshipped the cross unveiled in the presbytery. The text appears to allude, in fact, to the distinction between the external church and the internal church, specifically the choir of the nuns55. The latter, therefore, would have performed their Adoratio separately, prostrating themselves in turn completely on the ground in front of the altar and then briefly kissing the cross, first the abbess alone, followed two-by-two by the nuns and novices56. It is interesting to note, however, that it was the prioress, accompanied by the sacristan or another sister, who presented the guests with another cross outside the choir for adoration, probably in the nave57. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the ritual separation just highlighted was not due to a strict gender distinction but rather to the fact that the nuns were not allowed to enter the presbytery area.

After the Adoratio crucis, the priest proceeded with the consecration of the Eucharist, without the exchange of peace and the recitation of the Agnus Dei. Access to communion was reserved only for the celebrants, and the liturgy concluded. In the meantime, the monastic community had to turn towards the altar and, at the end, could go out into the cloister to wash their feet and put their shoes back on58. The interruption of the penitential posture assumed at the beginning of the day also concluded the most dramatic and intense phase of the Holy Week liturgy, leaving room for the reassuring expectation of the Resurrection.

4. Resurrection and Conclusions

The Ecclesiastica officia summarises the liturgy for the Easter Vigil, specifying the main instructions for the preparation and performance of the rite of blessing of the new fire, the blessing of the Easter candle, the liturgy of the word and the celebration of Mass. In Lichtenthal’s account, these actions are entrusted to the celebrating priest, assisted by a deacon59. The monastic community participated in the liturgy by singing specific texts, led exclusively by the cantrix in the choir, except for the recitation of the litanies, which was to be performed by two nuns in front of the steps of the presbytery60. The hymns were naturally the most solemn and triumphal of the year, above all the hymn Gloria in excelsis deo (Glory to God in the highest) in the newly illuminated church, accompanied by the thunderous return of the bells to emphasise the Resurrection of Christ in contrast to the subdued and mournful atmosphere of Good Friday61. Thus ended the collective liturgical journey of Holy Week for the nuns of Lichtenthal, who enlivened the most important feast of the year with their voices.

The analysis of the thirteenth-century copy of the Ecclesiastica officia of Lichtenthal fills, at least in part, the critical gap regarding the official liturgy in Cistercian convents. It documents not only the substantial adherence of the nuns of Lichtenthal to the Cistercian ritual prescriptions followed by the male branch of the Order but also how these rules were concretely adapted to the reality of cloistered life, its spatial specificities, and the spiritual sensibility of the nuns. At the moment, this analysis can only suggest that similar cases may have occurred elsewhere, a hypothesis that could be further tested or substantiated through the discovery of additional manuscripts.

The study of Holy Week in Lichtenthal shows how the architectural space, the ritual sequence, the use of liturgical books, and the disciplined physicality of the nuns were inseparable elements in the realisation of the liturgical mystery. The Palm Sunday procession and the Mandatum on Holy Thursday, while observing Cistercian regulations, reveal nuances specific to a female context: from the strict exclusion of outsiders at certain moments, to the use of gestures and routes that emphasised the community experience, to individual specificities—such as the commissioning of the tabernacle box by Sister Greda—which show a personal interaction with the sacred beyond physical and spatial limitations, thanks to artistic patronage.

In all the rites, the role of singing and gestures as instruments of mediation between the community and the divine clearly emerges, in a perspective that combines Bernardine affective theology and the tradition of spiritual harmony typical of the Benedictine order.

Far from being a mere container, the architecture was an integral and significant part of the liturgical action, shaping the sensory and devotional experience of the nuns.

Finally, Lichtenthal’s aristocratic identity, linked to the Margraves of Baden, added a dimension of representation and social interaction that was also reflected in the celebrations: moments of selective openness to the outside world, such as the distribution of palms to the familiares or the Maundy of the Poor, punctuated rituals imbued with a strong sense of community intimacy.

This manuscript, therefore, when considered in the context in which it was used, is not only a textual testimony to the functioning of the Cistercian liturgy for women but also a living source for reconstructing the practice, perception and experience of the sacred by religious women in the Middle Ages.

Funding

This scientific publication is part of a project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant agreement No. 950248). The project, entitled “The Sensuous Appeal of the Holy. Sensory Agency of Sacred Art and Somatised Spiritual Experiences in Medieval Europe (12th–15th century)—SenSArt” (PI Prof. Zuleika Murat) is being carried out at the Department of Cultural Heritage of the University of Padua in 2021–2026.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Among the studies on this topic see: (Kroesen 2000; Mecham 2014; Mattern 2014; Bynum 2015b; Dauven-van Knippenberg 2015; Bino 2016). |

| 2 | On the incorporation of female monasteries into the Cistercian Order, see: (Jamroziak 2013, pp. 127–36; Freeman 2020). |

| 3 | So much so that the interpretation of the Gallican rite officiated in the mother abbey of Citeaux and then propagated by the order was eventually accepted as the “Cistercian rite”. See: (Lekai 1975, pp. 1065–66). |

| 4 | A volume edited by me is scheduled for publication in 2026. It will offer a complete reproduction of the codex, together with its paleographic transcription and translation, as well as a series of in-depth essays. In view of the purpose of this article, abbreviations and contractions in my transcriptions of the manuscript have been expanded to facilitate ease of reading. A brief descriptive note on the manuscript can be found in (Heinzer 1995). |

| 5 | For an overview of the events concerning the foundation of Lichtenthal and its relationship with the Margraves of Baden, see: (Schindele 1984, pp. 25–33; Schwarzmaier 1995; Krimm 1995). |

| 6 | Further comparisons, albeit at a later chronological stage, can be made with the study by (Schlotheuber 2004). |

| 7 | On the selection of sites for Cistercian monastic foundations, see: (Vongrey 1975, p. 1034). |

| 8 | On these architectural developments, see: (Coester 1995; Stober 1995). |

| 9 | In addition to the plastering of the walls and certain updates to the furnishings and altars—carried out particularly from the Baroque period onward—the main structural alterations took place during the nineteenth century. For instance, in 1811 the nuns’ choir was shortened by one bay toward the high altar. Nevertheless, these transformations have not precluded an understanding of the medieval organization of the church’s liturgical spaces. On these changes, see: (Stober 1995). |

| 10 | The documentary evidence concerning these details is provided by (Stober 1995, pp. 95–100). |

| 11 | This aspect is noted by (Jäggi and Lobbedey 2008, p. 121) and in the Baden region it was also applied in female churches of other orders, as evidenced by (Coester 1995, pp. 88–94). |

| 12 | On the pulpit see: (Stober 1995, pp. 98–99). |

| 13 | On the regulations adopted by the Cistercians regarding the organization of monastic spaces see: (Vongrey 1975, pp. 1037–40). |

| 14 | With the renovations in the 18th century, a new residence was built for the abbess, which was no longer located in the cloister but in a completely new addition on the west side of the monastery. On the monastic spaces organization of Lichtenthal in the Middle-Ages see: (Stober 1995, p. 97). |

| 15 | For an overview of the Cistercian liturgy see: (Lekai 1975, pp. 1065–66; Dubois 1992, 2005; Choisselet and Vernet 1989, pp. 32–51). Gallican refers to a liturgical practice different from that of Rome and adopted mainly in France and Spain. For an overview of its origins, see: (Righetti 1950, pp. 123–39). |

| 16 | (Lia 2007, pp. 3–22, 87–106, 203–226). On Bernard of Clairvaux’s spiritual conception of the senses is also a reference work (McGuire 2014). |

| 17 | “Dominica in palmis a sacerdote exorcismus aquae agatur, deinde terciam hebdomadaria soror incipiat./On Palm Sunday a priest has to perform the exorcism of the water, thereafter the sister ebdomadaria begins the third hour.” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, f. 14v). |

| 18 | The procession of Palm Sunday is contained between fols. 10r and 23r. For information on the history of the manuscript, see: (Heinzer and Stamm 1987, p. 153—L. 53). |

| 19 | “[…] sacerdos arborum ramos benedicat et postea aqua benedicta aspergat. Quibus peractis cantrix postquam ramum abbatisse obtulerit incipiat antifonam Pueri haebreorum mox quis secrataria cum suffraganea sua ramos benedictos sororibus ac noviciis distribuat reliquam partem fratribus laicis et familie ac hospitibus si affuerint porrigat. […]/[…] the priest shall bless the branches of the trees and sprinkle them with holy water. Once these actions have been completed, the chantress, after presenting a branch to the abbess, has to begin the antiphon Pueri Hebraeorum. The secretary, with an assistant, shall distribute the blessed branches to the sisters and the novices, and the remaining ones to the lay brothers, the familiares, and the guests, if present.” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, f. 14v). |

| 20 | On the relationship between the Cistercians and the familia, see: (Cariboni 2019). |

| 21 | It may be hypothesized that the procession was arranged in two rows: on the right, the line of nuns who occupied the choir stalls on the abbess’s side, and on the left, those from the prioress’s side. This arrangement appears to be inferred from the following instructions concerning the entry into the chapter room for the recitation of the Psalter on Good Friday. As follows: “[…] Priorissa sequentibus ceteris capitulum intrent et iuxta ipsius domina introitum abbadissa ad dexteram et chorum eius […] priorissaque ad sinistram similiter cum suo choro sedeat ac psalterium ex integro persolvant./The prioress, followed by the others, enters the chapter room first; beside her, the lady abbess takes her place on the right with her choir, while the prioress sits on the left with her own choir, and the Psalter is recited in its entirety.” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, ff. 18v-19r). |

| 22 | “[…] His ergo ordinatis. Incipiente cantrice antifona Occurrunt turbe exeat una soror cum aqua benedicta praemoita a cantrice subsequente cum cruce discoperta. Qua subsequitur cumventu eo ordine quo stat in choro […] abbatissa eat posterior et prius ipsam novicie et fiat processio tantum per claustrum. Priorissa autem provideat nequid inconveniens in claustro inveniatur […]/[…] When these things have been arranged, as the chantress begins the antiphon Occurrunt turbae, a sister shall go forth with holy water, preceded by the chantress, followed by an uncovered cross. Thereafter the community follows in the order in which they stand in the choir […] the abbess shall go last, and before her the novices; and thus the procession is to take place only through the cloister. The prioress, moreover, shall ensure that nothing unsuitable is found in the cloister […].” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, ff. 14v-15r). |

| 23 | “Et notandum quod ad processiones quae fiunt per claustrum non hospitas mulieribus interesse nec ad sermones in capitulum intrare/It should be noted that female guests are not permitted to take part in the processions held in the cloister, nor to enter the chapter house for the sermons.” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, f. 15v). |

| 24 | “[…] Finita antifona Occurunt turbe incipiat antifona Collegerunt et dum haec canitur fiat prima stacio in parte que est iuxta dormitorium./After the antiphon Occurrunt turbae has concluded, the antiphon Collegerunt is to be begun; during its singing, the first station takes place at the area next to the dormitory.” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, f. 15r). |

| 25 | “Qua finita et sequente mox versu Unus antifona moveant se sorores ab illo loco et agatur iuxta refectorium statio secunda. Ad repeticione vero huius antifone scilicet Quid Facimus procedatur ad ultima stacione iuxta ecclesiam./When this has been completed, and immediately following with the verse of the antiphon Unus, the sisters shall move from that place, and the second station is to be held beside the refectory. At the repetition of this antiphon, namely Quid facimus, they shall proceed to the final station beside the church.” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, f. 15r). |

| 26 | An exception could be made for one dedicated to the deceased: “[…] Et sciendum quod hac die missa non sit cantanda praeter predictam, nisi cottidiana pro defunctis./[…] It should be noted that on this day no other Mass is to be sung, except for the one described above, unless perhaps the daily Mass for the dead.” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, f. 16v). |

| 27 | “Feria V ante Pascha missa celebretur post primam sollempniter […]. Omnesque ad pacem et ad communionem accedant. Sacerdos autem tot hostias consecrandas apponat ut et ipsa die fratribus et sororibus omnibus sancta comunio sufficiat et ad opus sequentis diei sacra comunionis reservari possit. […] Missa autem celebrata partem sacrae communionis in crastinum servanda Sacerdos in vasculo ante notato honorifice recondat. […]/On Thursday before Easter, Mass is to be celebrated solemnly after Prime […]. All shall then receive the Kiss of Peace and Communion. The priest, moreover, shall place upon the altar as many hosts to be consecrated as will suffice for the Holy Communion of all the brothers and sisters on that day, and so that a portion of the sacrament may be reserved for use on the following day. […] When the Mass has been celebrated, the priest shall reverently place in the aforesaid vessel the part of the Holy Communion to be kept for the morrow. […]” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, f. 16v). |

| 28 | “[…] Diebus dominicis et festis quibus solent ire sorores ad communionem, prior illarum que communicare voluerint, venient ad fenestram […]/On Sundays and feast days when the nuns usually receive communion, they shall go to the window, with precedence over those who wish to receive communion […]” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, f. 43r). This is a substantial change from the version of the text intended for monks, who were to receive communion at the main altar. (Choisselet and Vernet 1989, pp. 180–81). This applied both to Holy Thursday and to all other Masses on which the nuns were obliged to receive communion, namely Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost. However, they could voluntarily receive communion on the feasts of the Virgin Mary, St. John the Baptist, Sts. Peter and Paul, St. Bernard, All Saints’ Day, and on the dedication of the church. (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, ff. 44v-45r). |

| 29 | For an overview on this aspect see: (Muschiol 2001; 2008, p. 199). |

| 30 | Greda was the daughter of an nobleman from Speyer whose name was Albert Pfrumbom. The inscription enunciates: “Hanc archam conperavit [sic] soror Greda dicta Pfrumbomin de Spira in honorem Dominini [sic]/This casket was purchased by Sister Greda Prufmbom of Speyer in honor of God”. For the history and stylistic analysis of the work, see: (Wipfler 2020, pp. 570–76). |

| 31 | Although all the churches analyzed belong to the Poor Clares, a fundamental study regarding the relationship between the spatial arrangement of the nuns’ choirs and the perception of the Eucharistic consecration is: (Bruzelius 1992). |

| 32 | On this aspect, the reflections proposed in (Sand 2014, pp. 84–148) are particularly insightful. |

| 33 | See in particular the section on late Middle Ages in (Hamburger and Suckale 2008, pp. 91–108). |

| 34 | For the transcription and translation of the Maundy celebrations from Lanfranc’s Monastic Constitutions see: (Knowles 1951, pp. 31–36). |

| 35 | Some visitation records even attest to warnings or punishments against abbots for allowing high-ranking women to participate in funerals or other solemn rites (Jamroziak 2013, p. 131). |

| 36 | On this concept see: (Rudolph 1990, pp. 38–42, 102–103, 194–195). |

| 37 | Lanfranc requires that the antiphon “Dominus Iesus and others suitable” were to be sung (Knowles 1951, p. 32), as was generally prescribed and attested for the Washing of the Poor in the ordinals of other medieval monastic communities (Yardley 2012, pp. 169–70). |

| 38 | On the meaning of the liturgical kiss and of genuflection, see: (Righetti 1950, pp. 315–19). |

| 39 | Lanfranc, by contrast, calls for a symbolic identification of Christ with the poor: “[…] et inclinantes se flexis ad terram genibus adorent Christum in pauperibus […]/[…] and genuflecting and bowing down they shall adore Christ in the poor […]” (Knowles 1951, p 32). |

| 40 | For information on the history of the manuscript, see: (Heinzer and Stamm 1987, p. 314—Kl. L. 19). |

| 41 | (Karlsruhe, Badische Landesbibliothek, ms. Kl. L. 19, ff. 86r-88r). |

| 42 | For confirmation, see the website: https://cantusdatabase.org/feast/1475 and https://cantusdatabase.org/feast/1578 (accessed 10 august 2025). |

| 43 | (Karlsruhe, Badische Landesbibliothek, ms. Kl. L. 14, ff. 142v–146v). For information on the history of the manuscript, see: (Heinzer and Stamm 1987, pp. 311–12—Kl. L. 14). |

| 44 | “In parasceve parvo post laudes intervallo facto. Discalcient se sorores in dormitorio, deinde pulsentur tabula et aventer veniat in chorum oratioque fiat brevis […], sollempnis vero oratio ante tertiam persolvatur ex more./On Good Friday, after a brief interval following Lauds, the sisters removed their shoes in the dormitory. At the striking of the wooden boards they proceeded to the choir, where a short prayer was recited […], while the more solemn prayer, as customary, was performed before Terce.” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, ff. 18v-19r). |

| 45 | On the symbology of the bare feet in the Middle Ages, see: (Wirth 2012). |

| 46 | On the devotional meaning associated with the sensation of cold, a forthcoming essay by Vittorio Frighetto (member of the ERC-SenSArt research team), “Chilling with Fear: Emotions, Cognition, and Thermoception in Christ on the Cold Stone Representations”, will be published in 2026. For the opposite meaning, related to the sensation of heat, see (Murat 2024). |

| 47 | On the contrast between righteousness and curvature in Bernardo, see: (Lia 2007, pp. 163–69). |

| 48 | “[…] hymnus iam surgit hora tercia dicat et per totam diem vacent sorores lectioni. Post IX preparet se sacerdos ad officium celebrandum et al.taris superficiem mundis cooperiat pallis et duo luminaria circa altare accendantur, ut mos est festivis diebus./When the hymn Iam surgit at the Third Hour has been performed, the sisters will spend the whole day reading. After the Ninth Hour, the priest shall prepare himself to celebrate the office, and he shall cover the surface of the altar with clean cloths, while two lights are to be kindled at the altar, as is customary on feast days.” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, f. 19r). It is interesting to note that in the same passage of another copy of the Ecclesiastica officia belonging to the Lichtenthal collection, but written for monks and copied in Strasbourg in 1378, it is specified that at that time religious could devote themselves to individual penance: “[…] Expleto psalterio per totam diem vacent fratres lectioni. Qui autem voluerint accipiant ad privata altaria disciplinas quotquot voluerint unsque ad nonam […]/Once the psalter has been recited, the monks will spend the whole day reading. Those who wish to do so may perform all the penitential practices they desire at private altars until the ninth hour. […]” (Karlsruhe, Badische Landesbibliothek, L16, f. 48r). |

| 49 | “Deinde pulsata tabula veniant omnes monache in chorum et sacerdos ingrediatur ad altarem nudis pedibus oratione preaemittentes ante altare et legat sine titulo lectione in tribulatione sua qua finita dicatur Tractus Domine audiui. […]/Then, at the sounding of the wooden boards, all the nuns shall come into the choir, and the priest shall enter the altar barefoot, having first offered a prayer before the altar. He shall then read, without title, the lesson In tribulatione sua; when this has been completed, the Tract Domine, audivi is to be sung. […]” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, f. 19r). |

| 50 | “[…] Et circa finem earundem orationum aliquod grossum linteum in presbiterio sui altaris ab aliquo ferre interim, ubi crux est adoranda. […] Duo vero presbiteri sive clerici albis absque stolis et manipulis crucem cooperta retro altare iam antea ibi collocatam ad gradum altaris portent. Eamque re aliqua ad hoc convenienti subnixam./And toward the end of those prayers, some large linen cloth is meanwhile to be brought into the presbytery of the altar by someone, to the place where the cross is to be venerated. […] Then two priests or clerics, vested in albs but without stoles or maniples, shall carry the cross—already placed behind the altar and covered—to the step of the altar. There it shall be set upon an appropriate support […].” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, ff. 19r-v). |

| 51 | “Presbiteri adorent breviter postea se erigant unus ad dexteram et al.ter ad levam tenentes flexis poplitibus cantent Popule meus et due sorores a cantrice praemonite interius ante gradum sui altaris ter dicant Agyos semel in primo flectentes genua finito O Theos et erecte coetera prosequantur. Et chorus Sanctus ter repetat. Similiter ad primum flectentes genua. Dicto Sancto Deus et hoc tam a choro quam a sororibus tercio fiat similiter./The priests shall venerate briefly and then rise; one standing to the right and the other to the left, they shall sing Popule meus while kneeling. And two sisters, previously instructed by the chantress, shall advance inside [the choir], before the step of the altar, and recite three times Agyos: at the first they shall bend the knee, and, once O Theos has been completed, they shall continue the rest standing upright. The choir shall repeat Sanctus three times, likewise bending the knee at the first. When Sanctus Deus has been said, both by the choir and by the sisters, the same action shall be repeated a third time.” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, ff. 19v). |

| 52 | Karlsruhe, Badische Landesbibliothek, L46, ff. 92v-93r. For information on the history of the manuscript, see: (Heinzer and Stamm 1987, pp. 140–42—L46). |

| 53 | “Et dum ultimum Sanctus Deus incipit qui crucem tenent eam breviter adorent. Quo cantu finite detegentes eam imponant antiphonam Ecce lignum crucis moxque omnes veniam petant econtra et eandem antiphonam totius convenietur percantet et cruces alie a sacrista discooperantur./And when the final Sanctus Deus begins, those who hold the cross shall briefly venerate it. When the chant is ended, uncovering the cross, they shall intone the antiphon Ecce lignum crucis. Immediately thereafter, all shall bow in reverence, and the same antiphon shall be sung together by the whole community, while the other crosses are uncovered by the sacristan.” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, ff. 19v). |

| 54 | “Et sciendum quod eundem ordinem quem predicti presbieri sive clerici exterius de cruce faciunt et interius due sorores a cantrice praemonite ante gradum sui altaris faciant excerpto quod popule meus non cantent/Note that the same task of the cross performed outside by the aforementioned presbyters or clerics is performed inside by two nuns, previously warned by the cantrix, in front of the step of their altar, with the exception that they do not sing Popule meus”. (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, ff. 19v-20r). |

| 55 | Since the manuscript does not clearly specify that this action was to be performed in the choir, in a previous study I had assumed that the nuns descended the choir in order to venerate the cross (Tramarin 2024, pp. 184–85). Following this more detailed analysis, however, I believe it is appropriate to revise that interpretation. |

| 56 | “[…] Abbatissa vero sola et post illam due et due monache ac novicie indoctes sorores toto corpore prostrate ante gradum altaris crucem adorent et osculentur tantummodo et breviter. […]/[…] The abbess alone, and after her the nuns and novices in pairs, shall venerate the cross, lying prostrate with the whole body before the step of the altar, and kiss it only, and briefly. […]” (Karlsruhe, Badisches Generallandesarchiv, Hs. 65/323, f. 20r). |