Abstract

In his book The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross (1970), John Marco Allegro claimed that an obscure, 12th century CE fresco of the Fall of Adam and Eve in the Plaincourault Chapel in Mérigny, France, provided evidence of the persistence in Christian Europe of an underground sacred mushroom sect that had survived since New Testament times. At the heart of Allegro’s claim is the mushroom-like appearance of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil in the picture. Following up on Allegro’s claim, a small group of writers, led by Boston University’s Carl A. P. Ruck, spent decades seeking to validate Allegro’s theory by seeking out other examples of psychedelic mushrooms hidden in early Christian and Medieval art. The present article centers its discussion on the claims put forward by Allegro and his followers about the Plaincourault tree, but also about other images concerning which they have made similar claims. It concludes that the claims of Allegro and his followers concerning the Plaincourault tree fail due to their tendency to overpress similarities while ignoring differences.

Keywords:

Plaincourault Chapel; John M. Allegro; Adam and Eve in early Christian and Medieval art; psychedelic mushrooms; Amanita muscaria; Genesis 1–3 in Christian art; fresco techniques; Pilzbaum (mushroom tree); Christian Iconography; Abbey Church of Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe; Saint-Martin; Nohant-Vic; Bernward treasures at Hildesheim; Volto Santo; R. Gordon Wasson; Carl A. P. Ruck; Jan Irvin; John A Rush 1. Introduction

Fifty-five years ago, John Marco Allegro wrote the following in his controversial book The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross (1970):

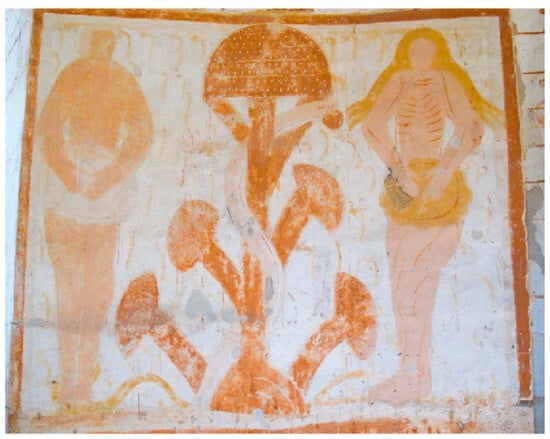

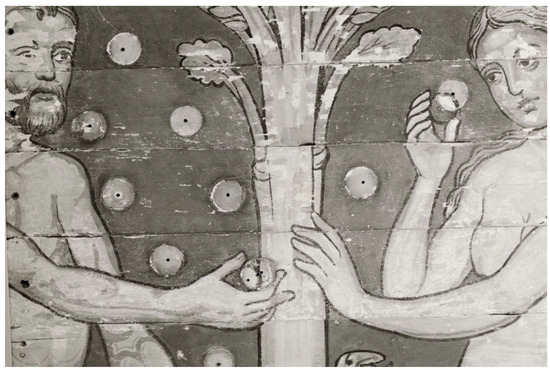

The whole Eden story is mushroom-based mythology, not least in the identity of the “tree” as the sacred fungus…Even as late as the thirteenth-century some recollection of the old tradition was known among Christians, to judge from a fresco painted on the wall of a ruined church in Plaincourault in France…There the Amanita muscaria is gloriously portrayed, entwined with a serpent, whilst Eve stands by holding her belly”.(Allegro 2009, p. 80). (See Figure 1) Figure 1. The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, Plaincourault Chapel, 12th cent. Photo: Aranthama, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 1. The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, Plaincourault Chapel, 12th cent. Photo: Aranthama, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Allegro (or his publisher) also included an image of the tree on the cover in reverse, stylized in a way that heightens the seeming similarity between it and Amanita muscaria mushrooms. In the passage above Allegro not only claims that the thirteenth- (actually twelfth-) century Plaincourault fresco presents the tree of the knowledge of good and evil as an Amanita muscaria mushroom, which is remarkable enough, but also that the fresco’s very existence provides proof that “some recollection of the old tradition was known among Christians.” Someone in thirteenth-century France, in other words, had somehow become the recipient of a tradition passed down from one mushroom-cult member to another for more than a thousand years, who were, at the same time, apparently successful in avoiding detection while living in the midst of a dominant false Christianity which, according to Allegro, had arisen as a result of a complete misunderstanding of the original coded meaning of the Bible (Allegro 2009, p. xxi). If Allegro’s claim was true, might not other such images be found in early Christian and Medieval art that likewise point to the ongoing survival of Allegro’s “old tradition”? In the years since Allegro wrote, a small coterie of writers, led primarily by Carl A. P. Ruck—a professor of classics at Boston University and the man who coined the term entheogens1—have been foraging for other images of psychedelic mushrooms hidden in Early Christian and Medieval art. In the present article I shall refer to this little group, as I have done elsewhere, as PMTs: Psychedelic Mushroom Theorists (see Huggins 2022, 2024). The PMTs represent those members of what J. Christian Greer calls “the enthogenic school,” that have advanced claims concerning hidden images of psychedelic mushrooms in art (Greer 2025, pp. 275–80).

When Allegro’s Sacred Mushroom was reprinted in 2009 it included a preface by PMT Jan Irvin, an introduction by Allegro’s daughter and biographer, Judith Anne Brown, and a concluding article by Carl A. P. Ruck. Each expressed their belief that the search for more images of psychoactive mushrooms had been a smashing success. Irvin claims that, in addition to the Plaincourault image, “hundreds of iconographic images” have been identified since the original publication of Allegro’s book (Allegro 2009, p. v.). Brown claims that such images recur in Medieval and Renaissance art “much more widely than Allegro realized at the time” (pp. x.–xi.). And Ruck claims that “a huge body of evidence” has emerged, including one piece that “should suffice to silence the arguments of the art historians” (pp. 375–76). The posture reflected in Ruck’s comment about the art historians is a common one among PMTs. Their standard view seems to be that art historians do not accept PMT claims because they are simply impervious to evidence. Art historians on the other hand might hold that the reason for their rejection of the proposals of Ruck and the PMTs lies elsewhere—especially after noticing that in Ruck’s description of the example that is supposed to “silence” them (MS. Bodl. 602, fol. 27v), the date given for the manuscript is a century off. Ruck and other PMTs who have discussed the image consistently refer to it as a 14th century manuscript. It actually dates to the 13th century. Moreover, the kind of manuscript it is has been misidentified. The PMTs call it an “alchemical text,” when it is really a bestiary. Furthermore, they misdescribe what is going on in the image. They imagine the picture shows a man in a state of entheogenic elation when in fact he is dying as a result of eating fruit poisoned by a salamander, a fact made clear by the accompanying Latin text, which none of them seem to have consulted. Parallel examples of the same theme in other bestiary manuscripts also leave no doubt as to the picture’s actual meaning. Ruck and the other PMTs even get the color of the tree wrong, calling it red when it is really a blue green. The reason I can speak of the entire group as uniformly making the same mistakes is that they are all uncritically repeating claims that can be traced to Bennett et al. 1995, and relying on the same poor-quality photo from (Gettings 1987). None of them apparently consulted the original manuscript.2

Allegro’s claim that the Plaincourault image demonstrates that “as late as the thirteenth-century some recollection of the old tradition was known among Christians,” presupposes that it had in fact been proven that such an “old tradition” ever existed. The assumption that it did served as catalyst for the PMTs’ optimistic quest for additional iconographic proof of its ongoing existence.3

But even supposing the many images the PMTs have gathered did depict mushrooms—which, as I have argued elsewhere, most of them surely do not (Huggins 2022, 2024)—without the backstory provided by Allegro’s theory, their meaning would likely remain ambiguous. To that extent the task of the PMTs was wed from the beginning to Allegro’s theory, which scholars pretty much universally reject. Why they do is a subject I would gladly pursue, but must put off to another time and for now refer the reader to Frend 1970; Cooper 1971; Jacobsen and Richardson 1971 along with the other articles in this Special Issue by Richard Ascough 2025 and Matthew Goff 2025. In the present article, I shall limit myself to examining the interpretation of the Plaincourault Fall of Eden (henceforth, for convenience, the “Plaincourault fresco”) by Allegro and the PMTs while at the same time taking advantage of the occasion to address their treatment of parallel details in other Early Christian and Medieval art.

2. Plaincourault in the Modern Era

We begin with a brief history of the discussion of the Plaincourault fresco in the modern era. The story begins with the 1 October 1909 issue of the Gazette médicale du centre where Jacques-Marie Rougé, secretary of the Congrès préhistorique de France, described an ancient, dilapidated chapel in the province of Touraine next to the Plaincourault castle, where one could see an almost completely deteriorated fresco of Adam and Eve, with forbidden fruit that looked like a mushroom, and a tree affecting “la forme phallique” (Rougé 1909, p. 214).4 He writes: “A droite de l’autel, Adam et Eve mangent le fruit défendu. ‘Ce fruit’ a l’aspect d’un champignon” (Rougé 1909, p. 126). Foreshadowing what was to come, Rougé’s description was incorrect. It was not the forbidden fruit but the tree itself that resembled a mushroom, or rather several mushrooms.

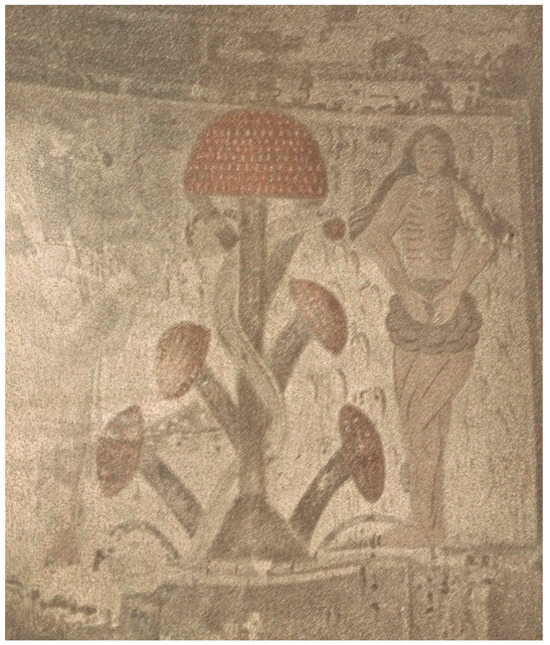

As it happened Léon Marchand, Professeur honoraire of cryptogamic botany at the University of Paris, read Rougé’s description, was intrigued by it, and arranged to have a photograph taken of the fresco. An enhanced version of that picture was published in the 1911 Bulletin trimestriel de la Société mycologique de France (Figure 2) accompanied with letters by Marchand and his colleague Émile Boudier discussing the find. In it Rougé’s description of the tree as phallic was dismissed by Marchand and identified as Amanita muscaria (fly agaric) by Boudier (Marchand and Boudier 1911, pp. 31–32). Part of this identification was based on the fact that the accompanying colorized photo had red-tinted caps, most conspicuously the uppermost one. The rest of the tree was left uncolored making it possible for the viewer to imagine it was white, as would be expected of an Amanita muscaria stipe.

Figure 2.

Colored Photo of Plaincourault fresco in 1911 Bulletin trimestriel de la Société mycologique de France, Pl. 0, p. 527. Public domain.

In fact, the basic color used not only for the caps but for the entire tree was red ochre,5 the same color that dominated the other frescos in the chapel.

Marchand’s and Boudier’s early view of the Plaincourault fresco was later repeated in authoritative works on mushrooms, including, for example, Ramsbottom’s A Handbook of the Larger British Fungi (1923) and Frank H. Brightman’s The Oxford Book of Flowerless Plants (1966). None of the writers so-far mentioned however focused on the hallucinogenic properties of Amanita muscaria. Rather those who mentioned effects at all, merely repeated some form of Boudier’s comment that in the fresco Eve looked as though she was suffering from colic rather than shame.6

In the meantime a new interest in psychoactive substances was emerging that would eventually cast a different light on the then-standard interpretation of the Plaincourault fresco. A key figure in this shift was the New York banker and amateur mycologist R. Gordon Wasson. Wasson believed that entheogens were responsible for the emergence of both religion and the consciousness that separates humans from other animals (Wasson in Forte 1997, p. 88). For Wasson the story of the eating of the forbidden fruit in Genesis “was clearly steeped in the lore of this entheogen,” i.e., Amanita muscaria, and was all about “the gift of self-consciousness” (ibid.).7 Naturally given this interpretation Wasson was interested in the potential significance of the fresco in the Plaincourault chapel, which he visited on 8 August 1952. In 1959 he arranged to have Michelle Bory of Paris’ Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle visit the chapel and make a reproduction,8 which he published in his 1968 book Soma (Pl. XXI, between pp. 180–81). Bory’s painting is truer to the original than the earlier published picture. For one thing it correctly depicts not only the caps but the entire tree as red. It still naturally fell short as an alternative to a good photograph of the image, inevitably leaving out important details.

Already by 1952, however, Wasson had been cautious enough to seek out the advice of the prominent art historian Erwin Panofsky on the identification of the Plaincourault Eden scene. Panofsky insisted that the tree in the picture did not represent Amanita muscaria, but was rather “one example…of a conventionalized tree style, prevalent in Romanesque and Early Gothic art,” of which, he says, there were “hundreds of instances…unknown, of course, to mycologists.”9 Panofsky also explained that the name art historians gave to this particular conventionalized tree was Pilzbaum (“mushroom-tree”).

Following up on the issue, Wasson sought out the views of other art historians who convinced him that Panofsky’s opinion represented “the unanimous view of those competent in Romanesque art” (Wasson and Doniger O’Flaherty 1968, p. 180). He henceforth adopted the view that “The Plaincourault fresco does not represent a mushroom and has no place in a discussion of ethno-mycology” (Wasson and Wasson 1957, 1.81, n. 1).

Panofsky’s information was, in fact, good, and accepting it put Wasson in a better position in relation to art than many other entheogen enthusiasts. Wasson was widely respected at the time as an early student of entheogens. This made his position on the Plaincourault fresco, and its source in the opinion of Panofsky and other art historians, a point of contention between himself and other PMTs.10 In their circles, Wasson’s cautionary note was, and has continued to be, rejected as “an unreflective dismissal [that] misses the point” (Hoffman et al. 2001, p. 21). It was portrayed as a case of Wasson uncritically allowing himself to be taken in by those blinkered by the “monodisciplinary blindness and interpretive slothfulness of professional researchers” (Samorini 2001, p. 268). In the end, Wasson was blamed for the “[u]ncritical acceptance of the Wasson-Panofsky view [which] lasted, unchecked, for nearly fifty years” (Irvin 2008, p. 1).

My own view is that the images turned up by the PMTs since have done little to undermine the validity of Panofsky’s assessment of the Plaincourault fresco. A key reason for this, I believe, is a casualness among PMT writers in the manner in which they handle evidence, which often displays a tendency toward ignoring obvious explanations in favor of rather tendentious, often overly ingenious and esoteric ones garnered from sources very remote to the images they are attempting to describe.

3. Two Trees

There are two trees mentioned in the second and third chapters of the book of Genesis as being in the Garden of Eden: (1) the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and (2) the tree of life. The forbidden fruit was on the former and by eating it Adam and Eve were barred from the latter and cast out of Eden. Allegro’s daughter wrongly identifies the Plaincourault tree as the tree of life (Irvin 2008, p. 10). PMTs Jerry B. and Julie M. Brown want to include the meaning of the tree of life in their interpretation of the Plaincourault tree by suggesting that after eating the forbidden fruit Adam and Eve had also managed to eat from the tree of life as well (Brown and Brown 2016, p. 216). Allegro’s daughter’s mistake is relatively trivial but the Browns’ attempt at blending the effects of the two trees take them far afield from anything really pertinent to the interpretation of the Plaincourault fresco. Their discussion in which this argument appears is framed in the form of a dialogue between the two authors, in which Julie Brown says:

“…look at Eve,”… “She has no breasts, no skin, and her entire upper body, her arms, and chest are skeletonized, as is Adam’s if you look closely. The living Eve with her bones exposed! Could it be that what this fresco is depicting is that Adam and Eve have actually eaten of the Tree of Immortality, which is the mushroom-tree, and are skeletonized because they are awakening to eternal life?” “As I recollect Genesis,” I added, “this may not be such a novel interpretation after all. Near the end of the section on the Temptation of Adam and Eve, God observes that man has become like us, to know good and evil, but what if he also eats of the Tree of Life and lives forever?”

Jerry then goes on to explain how in shamanism, life is thought to reside in bones, which he supports with a quote from Mircea Eliade: “To reduce oneself to the skeleton condition is equivalent to re-entering the womb of this primordial life, that is, to a complete renewal, mystical rebirth” (Brown and Brown 2016, p. 102; Eliade 1964, p. 63). But here we are dealing, not with shamanism, but with an example of Romanesque art illustrating a well-known biblical scene, a scene in which the Plaincourault fresco represented an iconographical tradition that reached back nearly a thousand years.11

4. Skeletonized?

What we now see when viewing the Plaincourault fresco is only the remnants of a largely defaced original. We can get an idea of the extent of deterioration from the fact that the figures originally had faces. These are not visible on most photographs, but archaeographer Carolina Sarrade of the University of Poitiers informs me they are still slightly visible.12 In a later period the Plaincourault fresco was even covered over by a Gothic fresco of which only a few fragments are still visible (Sarrade-Cobos 2006, p. 79). In order to further understand what remains of this fresco it is helpful to be aware of the difference between true fresco, i.e., painting on plaster while it is still wet, and painting a secco in which pigments are mixed with some other binder, such as egg yolk, water, or lime, which are then added to the picture after the plaster has dried. In true fresco the pigments interact with the lime in the plaster and are thereby bound to its surface. It is therefore much more durable than painting done a secco. But true fresco must also be carried out more quickly before the plaster dries. Only certain pigments can be used in true fresco, primarily earth pigments such as the ochers. There are a number of pigments that cannot be used in true fresco at all because their color does not remain true. Painting a secco on the other hand allows for much greater flexibility in the range of pigments applied and it is better fitted for introducing details at one’s leisure. With this technique the pigments are often applied on top of the colors previously laid down while the plaster was wet. But their lack of durability inclined painters of the Renaissance to avoid a secco painting entirely (see Thompson 1956, p. 72), as can be seen in comments like Giorgio Vasari’s: “paint in fresco, like men, without retouching in secco; which, besides being a most vile practice, shortens the duration of the pictures” (Vasari qtd. in Merrifield 1952, p. 31).

Let us consider, then, the implications for what colors might actually have been like in the Plaincourault fresco to begin with and how they look now to art historically trained and untrained observers. What we are mainly looking at in the fresco is the part of it that was done while the plaster was still wet. Portions of the picture had been marked out in the plaster with a stylus, which I take to have been done in preparation for details that would afterward be added a secco, but, as in the case of the details of the faces, have now almost entirely vanished. The broad color shapes of the figures and the tree were brushed in along with quick lines to mark the basic position of Eve’s ribs, arms and muscles (Sarrade-Cobos 2006, p. 82). The pink used for her body makes it clear, contra the Browns’ statement, that the original artist intended Eve to have skin. It is also an exaggeration to say that her entire upper body is skeletonized. At most one can say it about her ribs. But as briskly as these have been dashed in along with the arms and legs with the same red strokes, it seems more likely the artist was simply setting out the broad outlines to serve as a guide for the filling in the details a secco, including such details, for example, as Eve’s breasts.13 That more detail was originally intended is probably also suggested by the incised features in the plaster marking out Adam’s limbs, his fig leaf, his eyes and his pupils. The same was done with the snake, which also retains raised white dots. Also remaining on the current picture is a small remnant of a black line on Eve’s little finger (Sarrade-Cobos 2006, pp. 82, 85). Looking at the strokes interpreted by the Browns as “skeletonization”, especially those on Eve’s legs, it seems unlikely that what survives represents what the original finished painting looked like. The best way of getting an idea of what the original might have been like, how the details on the hair, faces, hands, feet, and bodies of Adam and Eve would have been rendered, is to look at the better-preserved portions of the 11th–12th century frescos in the nearby Abbey Church of Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe, which is sometimes called the “Romanesque Sistine Chapel.” The fact that it is in walking distance of the Plaincourault chapel (c. 7 miles), and that its many frescos were produced so near in time to the Plaincourault frescos, makes it highly significant as a point of comparison. Then there is also the somewhat more distant 12th century frescos from Saint-Martin, Nohant-Vic (c. 56 miles from the chapel).14

5. Fig Leaves and Mushroom Caps

5.1. The Plaincourault Fig Leaves

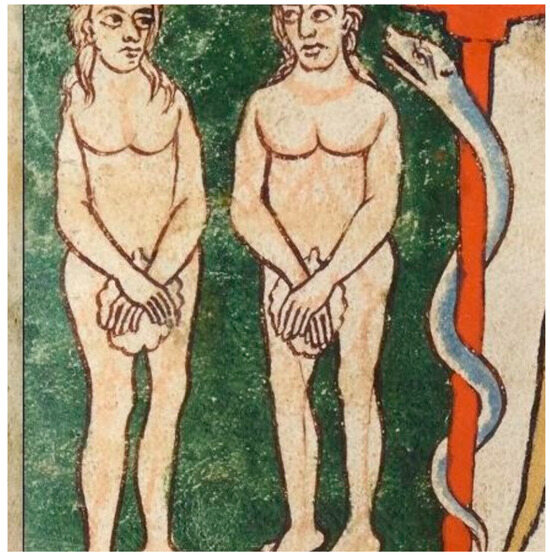

PMTs often approach Early Christian and Medieval art, including the Plaincourault fresco, with the expectation that artists of the period aimed for at a greater level of naturalism than they actually did. Noticing that what Adam and Eve cover themselves with in the Plaincourault fresco do not look like fig leaves, certain PMTs argue that they must have been intended to represent something else, namely Amanita muscaria. “Adam and Eve,” Ruck writes, “have attempted to cover their nakedness naively with the nearest object at hand—which looks like large Amanita muscaria caps” (Ruck in Allegro 2009, pp. 376–77; see also a similar claim in Brown and Brown 2016, p. 97; also already Boudier [Marchand and Boudier 1911, p. 32]). But if that were the case then why was Eve’s fig leaf colored yellow ocher15 and Adam’s white? Why were not both painted in red ocher like the tree and the forbidden fruit? And why are there no white dots of the sort we might expect to see on an Amanita muscaria cap? But more to the point, those familiar with images of the fall in Early and Medieval Christian art know not to expect the fig leaves to anachronistically adhere to later expectations of botanical verisimilitude (Figure 3). Also there is a tendency among PMTs to count almost anything that is round as a mushroom cap. Let us turn to consider an example of the latter in the Great Canterbury Psalter.

Figure 3.

Beatus super Apocalypsim, John Rylands Library—Latin MS 8, fol. 44r/Image 95 (detail) 1180. Public domain.

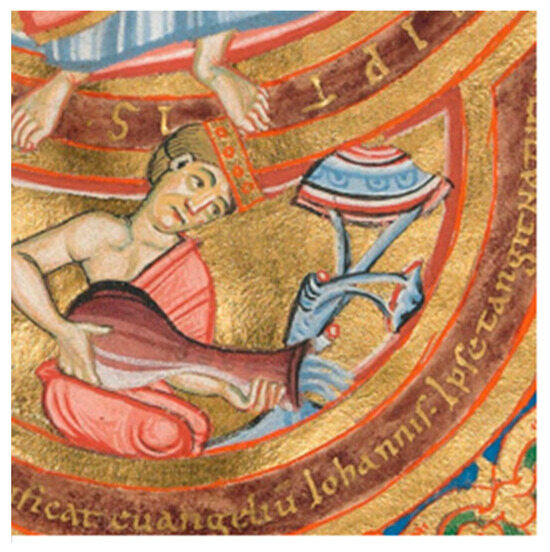

5.2. The Great Canterbury Psalter

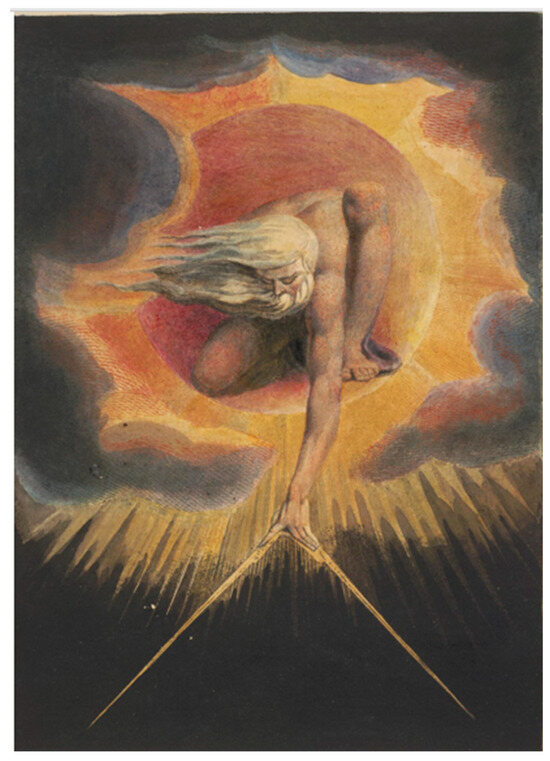

The depiction of the first day of creation in the famous 12th century Great Canterbury Psalter shows God, in the form of the pre-incarnate Jesus, dwelling in what appear to be concentric rings of fire (Figure 4). Given that the image is presented in a circular frame, as are all the creation days in the work, Hoffman, Ruck, and Staples, claim that it depicts the underside of a mushroom (Hoffman et al. 2001, pp. 32–33). This despite its lacking characteristic features like gills. PMT John Rush makes the same claim, but ventures to assert, in addition, that “in [God’s] left hand there is a variation on the alpha and omega” (Rush 2011, p. 201). What Rush was actually looking at was an architect’s compass, a detail that frequently appeared in such scenes (Figure 5 and Figure 6).16

Figure 4.

Great Canterbury Psalter, Bibliothèque nationale de France = BnF, Latin 8846, fol. 1r (detail) 12th–13th cent. Public domain.

Figure 5.

Codex Vindobonensis 2554, frontispiece (1220–1230). French. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (=ÖNB). Public domain.

Figure 6.

William Blake, frontispiece to Europe a Prophesy (1794). Copy D, plate 1. © The Trustees of the British Museum. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Deed.

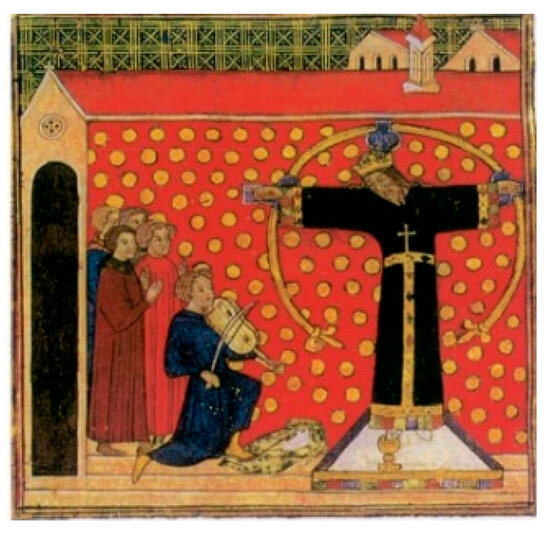

5.3. The Volto Santo of Lucca

Another example of an item wrongly identified as a mushroom cap appears on the cover of Carl A. P. Ruck’s and Mark A. Hofmann’s 2012 book The Effluents of Deity where we see an image from the Baptistery in Parma, Italy, which the authors claim represents Christ on a cross set against the backdrop of an “red-orange communion wafer, spotted with golden apples…the mature version of the [Amanita muscaria] mushroom cap” (Ruck and Hoffman 2012, p. 55). Below the cross, on the left we see a man kneeling who the authors identify as “King David…playing his fiddle” (ibid.). The image actually depicts a miracle tale about a pilgrim (not King David) playing his violin before a famous crucifix known as the Volto Santo (Holy Face) of Lucca, so called because of a story about the face of Christ on the crucifix having been completed by an angel. The golden apples which were supposedly depict a “red-orange communion wafer” were actually part of the decoration on the larger wall behind the famous crucifix, a fact confirmed by other images of the Volto Santo17 (Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Figure 7.

The Volto Santo in the Parma Baptistery (c. 1370) (Ruck/Hoffman cover).

Figure 8.

Volto Santo in the Church of St. Francis, Gualdo Tadino, Italy (1474), credit: Sailco, Wikimedia Commons, CC-3.0 Unported.

Figure 9.

The Volto Santo in Codex Rapondi, Vatican MS Pat.lat.1988, fol. 16v (c. 1400–1405). Wikimedia Commons, Public domain.

Figure 10.

Volto Santo in 2011. Wikimedia Commons, CC-3.0.

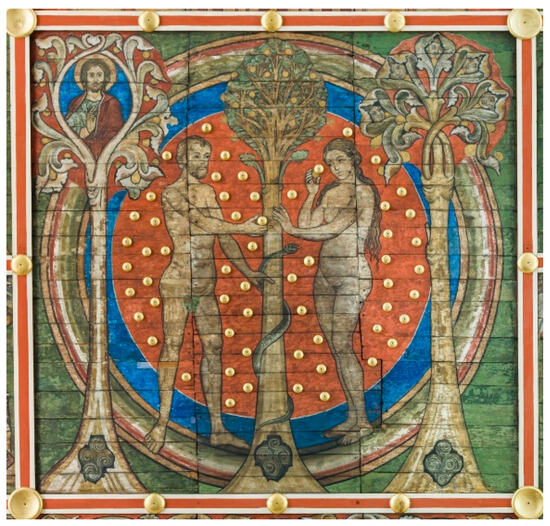

5.4. The Fall of Adam and Eve, Saint Michael’s Church Ceiling, Hildesheim, Germany (Figure 11)

On the ceiling of Saint Michael’s church in Hildesheim we find an image of the Fall in a circular frame with a red background covered with golden wooden hemispheres (Figure 11). Jan Irvin claims that the “background is the top of a red Amanita muscaria cap, complete with spots. The fruit eaten by Eve is one of the spots of the mushroom cap” (Pl. 12). Similarly Hoffman, Ruck, and Staples write:

none of these [golden discs]…are on the tree itself, only the fruits of the painted background. Two more of these bossed hemispheres are being shared by the couple in Eden. One is deliberately out of place. In Eve’s hand, the apple is slightly displaced so that the painted version underneath it gives the appearance of a stipe.

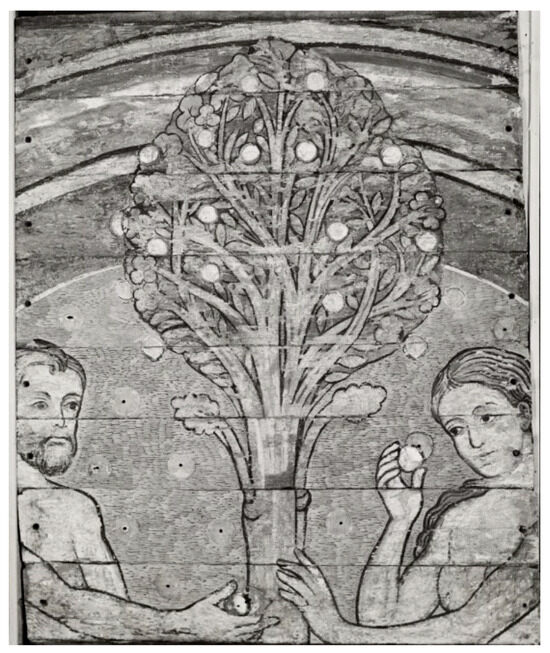

But again there are problems. The first is that the golden discs were not part of the original work. Hofmann, Ruck, and Staples ought to have been given pause when they noted that the gold disc seemingly held by Eve is “slightly displaced” revealing a “painted version underneath.” The fact that a “painted version” exists raises the question of whether there are other painted versions of the fruit under the rest of the gold discs filling the red field around Adam and Eve. And the answer is: it appears there were not. The entire painted ceiling was disassembled and hidden in a mine during World War II to protect it from allied bombers. In the course of restoring and reassembling the ceiling in the 1950s the discs were removed and the scene photographed without them (Figure 12).

Figure 11.

The Fall of Adam and Eve (12th cent.), Saint Michael’s Church ceiling, Hildesheim, Germany. Photo: Jens Kotlenga. (Evangelische Kirchengemeinde St. Michaelis, Hildesheim).

Figure 12.

Hildesheim Adam and Eve with the gold discs removed. Published by kind permission of Evangelische Kirchengemeinde St. Michaelis, Hildesheim.

The addition of the gold discs was part of a larger decorative embellishment that also included other, larger gold discs distributed over the rest of the ceiling painting. These likely date from centuries after the original (see Sommer 1999, pp. 64–66). In short, the red field was not originally intended to depict, to quote Irvin, “a red Amanita muscaria cap, complete with spots.”

As to Hoffman, Ruck, and Staples’s claim that the gold disc had been “deliberately out of place” to make it appear like a mushroom with a stipe, the post-World War II photographs suggest a different reason. The decorative gold discs were significantly larger than the original fruit painted in the hands of Adam and Eve, making it impossible to place them directly on top of that fruit while at the same time making it appear that the hands of the first couple are actually holding and not simply being covered over by the discs. This can be seen by the fact that in placing the gold disc over Adam’s fruit, the disks were pounded in three different times before getting it right. Once directly over the fruit, once a little beyond the edge of the fruit, and then finally on the fruit’s edge.18 It seems probable that Adam’s fruit was put in place first, and then, once the problem of making it seem that Adam’s fingers were holding it was solved, they used what they had learned to place the disc over Eve’s piece of fruit (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Hildesheim Adam and Eve with the gold discs removed prior to cleaning. Published by the kind permission of Evangelische Kirchengemeinde St. Michaelis, Hildesheim.

6. Snake or Caduceus

From the point of view of Christian Iconography during its first thousand years, the snake in the Plaincourault fresco, curled as it is around the tree, is entirely conventional,19 as is the round fruit in its mouth. The Book of Genesis does not name the fruit, so the kind of fruit depicted varied considerably before finally settling firmly on the apple, which was occurring especially in France at about the time the Plaincourault image was painted (Yadin-Israel 2022, p. 63). Other fruits depicted both earlier and later included clusters of grapes, pomegranates, figs, and even, in at least one instance, a citron.20

Jan Irvin wants to endow the Plaincourault fresco, along with other images he would like to identify as mushroom trees, with psychedelic significance by claiming that the snake curling itself around the tree represents a caduceus, which, he says, “is the symbol of medicine and drugs” (Irvin 2008, Pl. 1). However, Irvin makes the common mistake of confusing the caduceus, which has two snakes, with the Rod of Asclepius, which has one. In any case, most images of Eden’s tree from the beginning of Christian art, including those with quite non-mushroom-like foliage, showed the serpent coiling around the tree. Therefore Irvin’s proposed connection of the Plaincourault tree with a caduceus is no help in trying to single out that particular tree as a mushroom tree.

7. A Pine Tree?

“Anyone can see this [the Plaincourault tree] is obviously a mushroom and not by any stretch of the imagination a pine tree.”(Julie Brown in Brown and Brown 2016, pp. 101–2)

PMTs often stress the fact that the Plaincourault tree does not resemble a pine tree (See further, e.g., Ruck in Allegro 2009, p. 376; Irvin 2008, p. 1; Samorini 1998, pp. 30–31; Hoffman 2006). So why should anyone imagine that it would? The issue goes back to remarks made in a letter from Panofsky to R. Gordon Wasson. On 2 May 1952 Panofsky wrote:

The Plaincourault fresco is only one example…of a conventionalized tree type prevalent in Romanesque and Early Gothic art, which historians actually refer to as “mushroom tree” or in German writing Pilzbaum. It comes about by the gradual schematization of the impressionistically rendered Italian pine tree in Roman and Early Christian painting, and there are hundreds of instances exemplifying this development…What the mycologists have overlooked is that medieval artists hardly ever worked from nature but from classical prototypes which in the course of repeated copying became quite unrecognizable.21

When complaining that the Plaincourault tree does not look like a pine tree, the PMTs overlook the last part of Panofsky’s statement about their being copied and schematized until the original connection had become “quite unrecognizable.” In other words, medieval mushroom trees, Pilzbäume, do not much resemble Italian pine. At the time of the painting of the Plaincourault tree, medieval painters’ approach to depicting trees had long since become formulaic with more interest in their potential use as decorative elements than in any form of realistic depiction.22 To be sure certain standard tree forms did persist, such as the palm, the cypress, and the umbrella-shaped mushroom tree. In his letter Panofsky had recommended that Wasson read A. E. Brinckmann’s Baumstilisierungen in der mittelalterlichen Malerei (1906). Brinckmann referred to some of the trees in artistic depictions by their names but others by their dominant features, the latter of which included their basic shape. The Pilzbaum, which he described as resembling an open parasol or umbrella (aufgespannter Schirm) was one example of the latter. Others included, for example, the Lanzettbaum, or lancet tree, which he described as having an almond shape (1906, p. 11), the Pinienzapfenbaum, or pine-cone tree, i.e., one whose crown was shaped like a pine cone, and the Blätterkronbaum tree, or leaf-crown tree, whose crown of oversized leaves were generally round or in the shape of a cone (1906, p. 43, Taf. VI, 11). These names, as we said, were given to describe certain dominant features in the ways particular trees were depicted in art, without any suggestion that they represented anything other than trees. Although the term Pilzbaum was settled upon by art historians to talk about trees with semi-circular crowns (a form even children sometimes intuitively adopt when drawing the crown of trees) they might have as easily spoken instead of a Schirmbaum or Umbrella Tree. Indeed the Italian pine (Pinus pinea) Panofsky referred to is sometimes called an Italian Umbrella Pine. And just as no one would imagine an umbrella tree was an umbrella, neither should we confuse a Pilzbaum with a mushroom.

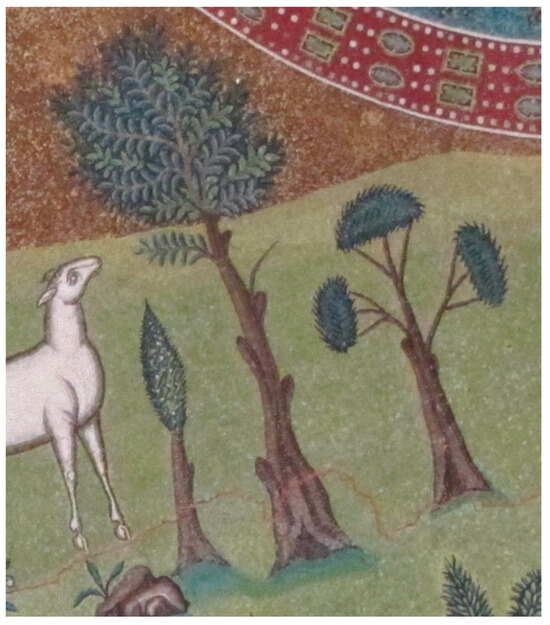

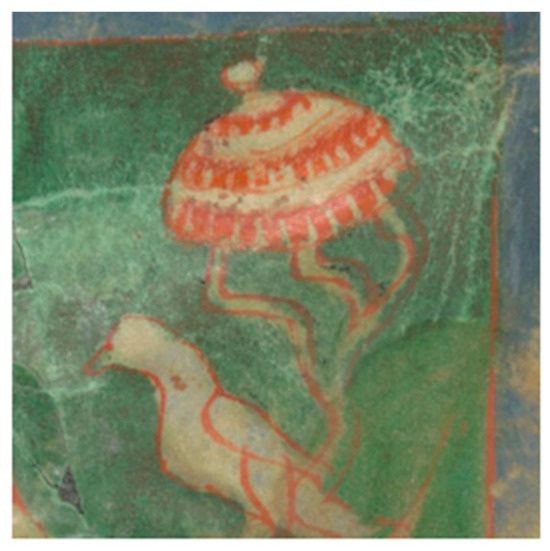

We see the beginning of the process of the development of the Pilzbaum in Early Christian art in the beautiful apse mosaic of the 6th century Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, which is about 2 1/2 miles from Ravenna. The region boasted the most ancient and famous Pinus pinea forest in Italy, mentioned by Dante (Purgatorio 28.20–21), Boccaccio (Decameron V.8), and Byron (Don Juan, Canto 3). Today the Basilica itself is surrounded by Italian pine. In our image of the fresco, what came to be known as the mushroom tree is seen on the right. Clearly intended to represent, not a mushroom, but a tree. The tree on the left similarly represents a Cypress (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Early examples of stylized trees from the apse of the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, Italy (detail) 6th cent. Photo: R.V. Huggins.

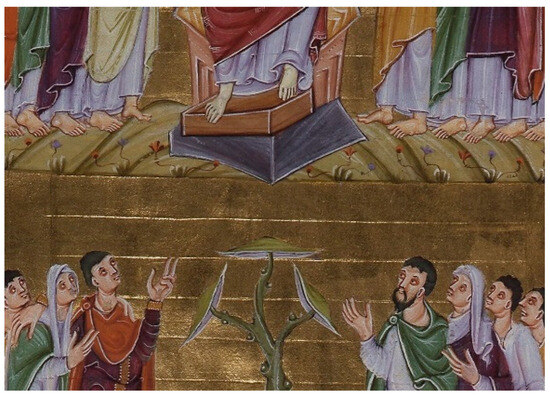

The term Pilzbaum itself might seem to give credence to the PMTs’ claims that there are many examples where medieval depictions of trees do not represent trees at all, but, as José Celdrán and Carl Ruck suggest, “hongos y nada más” (that is, “mushrooms and nothing more”) (Celdrán and Ruck 2002). But that is certainly not true. While there are indeed hundreds of Pilzbäume in medieval paintings, miniatures, and sculptures, there are only a small handful of images in which the crowns actually resemble mushrooms. The Plaincourault image is one. Another image featured by PMTs is a fresco at Saint-Martin, Nohant-Vic. That picture depicts the triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem, when, as the Gospel of Matthew reports: “a very great multitude spread their garments in the way: and others cut boughs from the trees and strewed them in the way” (28:1 = Mark 11:1–11, John 12:13).23 In the fresco the boughs being broken off to be laid on the road have crowns that resemble diamonds on the one hand and mushroom caps on the other (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Preparation for Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem, Saint-Martin, Nohant-Vic (1135–1140) from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. Original source: image donated by Jim Womack and Anne Richardson. Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0.

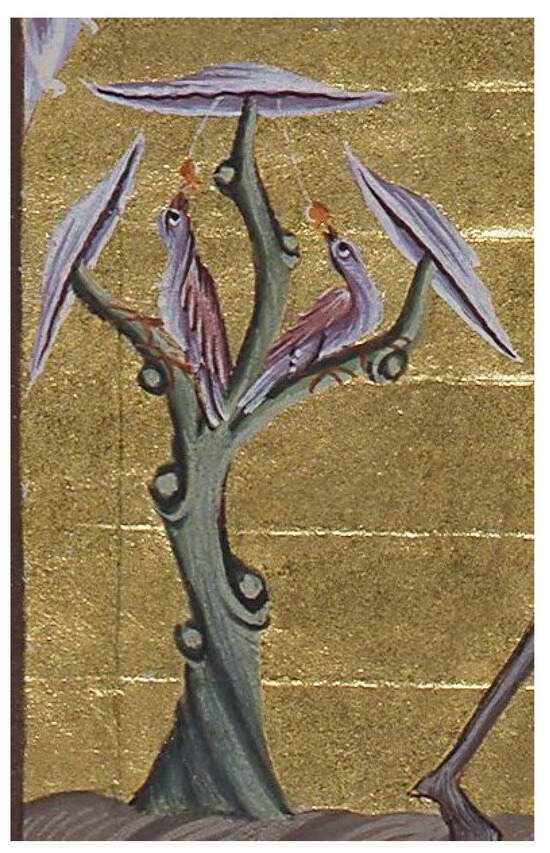

Other examples are found in several interrelated Ottonian manuscripts produced in the scriptorium at Reichenau in the years immediately flanking the turn of the first millennium.24 Irvin includes a plate showing one of these in which he says, “men are depicted worshipping a mushroom-capped tree on the mount” (Irvin 2008, Pl. 18). He offers a picture that is not sufficiently clear to see where the men’s attention is actually focused. A clearer image permits us to see that the men are not looking at the tree, but at Jesus, who is delivering the Sermon on the Mount (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Sermon on the Mount, Gospel Book of Otto III, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, München (=BSB) Clm 4453, fol. 34v.

An ongoing impediment to accepting the validity of the PMTs’ claims is their tendency to over press similarities while ignoring differences. In response to this I have elsewhere suggested three cautionary rules of thumb when considering whether a given medieval image might represent a mushroom: “(1) If it has branches, or multiple crowns, or a crown supported by multiple branches, it is a tree not a mushroom; (2) If it has indications of layers of foliage [or, for that matter, of foliage period] in the crown, it is a tree not a mushroom; and (3) If it has fruit, it is a tree not a mushroom, since mushrooms, being cryptogams, have neither fruit nor seeds” (Huggins 2024, p. 24). The Reichenau trees fail the test because they have both branches and multiple crowns, several of which display fruit. In one case we even see birds eating the fruit (Figure 17). The trees of the triumphal entry scene from Saint-Martin, Nohant-Vic, similarly would seem to fail because of the multiple branches and crowns (Figure 15) although I will say that the crowns on these trees look more like mushrooms than any I have seen elsewhere in Early or Medieval Christian art, apart from a mosaic of a basket of mushrooms in the Basilica of Aquileia in Italy (c. 330), and in medieval herbals where mushrooms along with other plants are depicted and described (see, e.g., MS M.652 fol. 316v (10th century) and BnF Latin 6823, fol. 68r (1301–1350).

Figure 17.

Gospel Book of Otto III. BSB Clm 4453, fol. 234r (detail) c. 1000.

The Plaincourault tree likewise fails the test by having branches, four of which have single crowns, with the largest crown being supported by a central trunk and two branches. Especially problematic for the PMTs’ identification is the three branches supporting the top-most crown. This would not be the case if the artist had intended to depict an Amanita muscaria mushroom and “nada mas.” The cap of Amanita muscaria is supported by one central stipe. PMT Samorini sought a way around this problem by suggesting that “these ramifications [branches] might represent the membrane enveloping mushrooms of the family of the Amanitaceae at the early stages of development. This membrane then breaks when the cap broadens out and separates from the stalk” (Samorini 1998, p. 89; 2001, p. 268). The same argument was in fact already put forward by Émile Boudier (Marchand and Boudier 1911, p. 32). Both however anachronistically project a greater interest in botanical accuracy than is justified for the artists of the period.

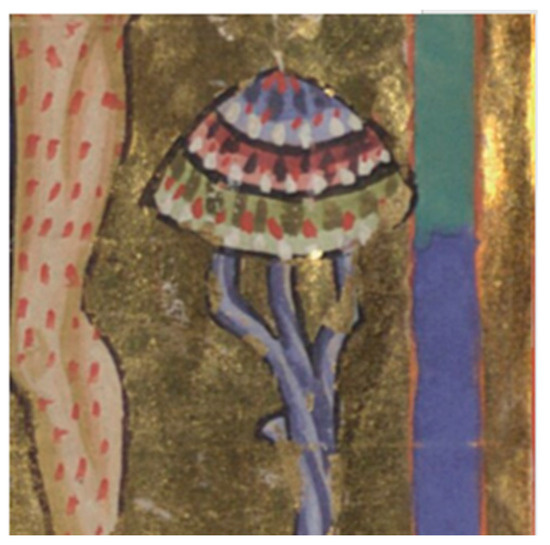

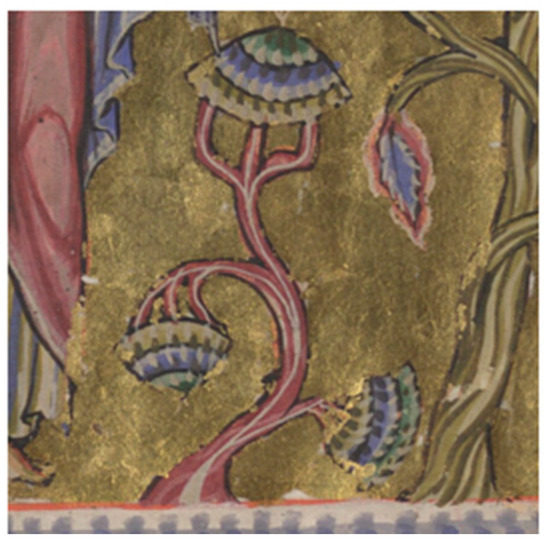

8. The Crown

The feature of the Plaincourault image that most resembles Amanita muscaria is its uppermost crown. The other crowns also can be thought to resemble other species of fungi. As noted earlier the seeming significance of the redness of the cap as evidence of its being Amanita muscaria is counterbalanced by the fact that the entire tree, rather than just its crowns, were produced using that color. No effort on the part of the artist is evident to distinguish between the red cap of the mushroom and an expected white stipe. We have already noted that whatever might have been added in secco has long since almost entirely disappeared and that nevertheless certain features visible in the painting as it stands do appear to testify to the artist’s intent to further elaborate the image. Some of these features are also found on the crowns, where we see that horizontal lines have been added to the top-most crown by sgraffito, i.e., by scratching through the red ochre to reveal the plaster underneath. The same lines have also been added to one or more other crowns. If these lines were produced, as we suspect, in preparation for what was to come later in the process of creating the image, then we can tell from numerous other images what the artist may have had in mind. For example, it was typical in the centuries leading up to and following that time for the crowns of the so-called mushroom trees to be divided up into layers of either foliage, or bands of color, or both (Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24 and Figure 25).

Figure 18.

Uta Codex, BSB Clm 13601, fol. 89r, (1st quarter of the 11th cent.). Wikimedia commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 19.

Admont Giant Bible, fol. 3v/image 18 (1140–1150). Public domain.

Figure 20.

Great Canterbury Psalter, BnF Latin 8846 fol. 6v (12th cent.). Public domain.

Figure 21.

Admont Giant Bible, ÖNB, fol. 94v/image 202 (1140–1150). Public domain.

Figure 22.

Bernward Columb, Hildesheim, Germany (1020). Photo: Jens Kotlenga (Evangelische Kirchengemeinde St. Michaelis, Hildesheim).

Figure 23.

Pericope Book of St. Erentrud, BSB Clm 15903, fol. 24r (detail), 11th–12th cent. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 24.

Fall of Adam and Eve. Bernward Doors (1015). Photo: Jens Kotlenga (Evangelische Kirchengemeinde St. Michaelis, Hildesheim).

Figure 25.

Pericope Book of St. Erentrud, BSB Clm 15903, fol. 96r (detail) 11th–12th cent. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Notice as well in these images that it was also typical for tree crowns to be decorated by lines of dots in white or other colors. Despite the PMTs’ seizing upon these as proof of their identification as mushrooms, these embellishments do not clearly establish an obvious connection between the Plaincourault tree and Amanita muscaria. This decorative convention may be, probably is, what the painter of Plaincourault image had in mind when including the white dots. The mushroom tree that most reminds me of the Plaincourault tree in terms of the shape of its crown comes from the 9th century Gospels of Francis II (Figure 26), and in terms of its pattern of dots, from the 12th century Admont Giant Bible (Figure 27).

Figure 26.

Gospel Book of Francis II, Ms. Latin 257, BnF, fol. 60v (850–875). Public domain.

Figure 27.

Admont Giant Bible, ÖNB, fol. 68v/image 150 (detail) 1140–1150. Public domain.

It should be noted that the PMTs, I believe due to the imprecision of their approach, would consider, and in some cases have considered, the images I have shown in Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24 and Figure 25, simply as further proof of hidden psychedelic mushrooms in Medieval art. A conspicuous case in point is their treatment of the tree in the scene of the fall of Adam and Eve on the 11th century Bernward Doors in Hildesheim, Germany (Figure 28, c.f. Figure 24).

Figure 28.

Bernward Doors. Hildesheim, Germany. (1015). Photo: Jens Kotlenga (Evangelische Kirchengemeinde St. Michaelis, Hildesheim).

This scene has been of particular interest to the PMTs since they became aware of it via the English translation of Jochen Gartz’s Narrenschwämme: Psychotrope Pilze in Europa (1993, Fig. 1, cf. 1996, Fig. 6). Giorgio Samorini is very definitive on the identity of the tree in the picture: “The mushroom-tree [between Adam and Eve] is realistically rendered with a precision not far short of anatomic accuracy and can be identified as one of the most common Germanic and European psilocybin mushroom, P. Semilanceata…” (Samorini 1998, p. 103). Samorini goes on to identify the tree as a “‘Saint-Savin’ type of mushroom (three striated mushrooms),” arguing that “the third mushroom has been consumed by Adam and Eve, as revealed by the broken branch springing from the lower part of the tree trunk” (ibid.). Hoffman, Ruck, and Staples follow Samorini, repeating his claim that the tree “is here represented as the ‘mushroom tree,’ usually shown with a triple branching, but in this version one branch is missing, the one that has been eaten” (Hoffman et al. 2001, p. 29).

But several missteps have been made here. It is true that the crowns of mushroom trees, as well as those of other kinds of stylized trees, often appeared in groups of three…, but this does not occur regularly enough to be in any sense normative, such that we can assume that when there are two crowns one is missing, much less that it has been eaten! Indeed a previous panel on the same door showed two mushroom trees each with five foliage heads. Furthermore, although one of the broken-off branches is prominent, more are indicated. We also know from the previous scene on the door that what Adam and Eve ate was a small, round fruit from a different tree, not a foliage head from the one shown. What does appear to be the case is that Adam and Eve are depicted covering themselves with foliage heads of the same sort as those on the tree they are standing beside.

Finally, the claim that the tree looks like the psilocybin mushroom P. Semilanceata simply isn’t true. Samorini buttresses the claim by categorizing it as a Saint-Savin type tree, which, although the Saint-Savin tree he is referring to does somewhat resemble P. Semilanceata, it is actually not that mushroom or any other, as is seen by the fact that it has hanging fruit, which is fitting given that the scene in which it appears illustrates creation days three and four where, as we read in Genesis 1:11, God said, “Let the earth bring forth the green herb, and such as may seed, and the fruit tree yielding fruit after its kind, which may have seed in itself upon the earth” (Figure 29).25

Figure 29.

Creation days 3–4 (Genesis 1:9–19). Abbey of Saint-Savin-sur Gartempe (late 11th–early 12th cent.). Photo: GO69, Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

9. Conclusions: Mandrakes into Mushrooms

We started this article talking about John Marco Allegro. Let us finish it then with him as well. Back in his day Allegro seemed able to trace at will any word in any language, even modern English, back to real or hypothetical Sumerian roots or “word plays” or allusions that invariably turned out to refer to one of three things: mushrooms, penises, or vulvas. One can scarcely read his The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross without coming away with the impression that the ancient Sumerians must have spoken of little else, an idea easily set right by perusing actual Sumerian texts in translation at, for example, Oxford University’s Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk) or in a number of other readily available older collections. One of Allegro’s most ambitious feats of etymological acrobatics was his argument that the mandrake was a mushroom (Allegro 2009, p. 41). Allegro tells us that our English word, along with its Greek predecessor mandragoras, derived its name from the hypothetical Sumerian word *NAM-TAR-AGAR,26 which, according to Allegro, meant “‘demon or fate-plant of the field”27 (ibid.). But *NAM-TAR-AGAR didn’t really sound like mandragoras. So Allegro made free to tweak things a bit by claiming that the “consonants m and n have changed places and T has shifted to the closely related sound d” (ibid.). In this way Allegro managed to wrangle MAN-DAR-AGAR out of NAM-TAR-AGAR, bringing it a little closer in appearance, if not in meaning, to mandragoras. That was only the beginning of the process by which Allegro made a mandrake into a mushroom. But we needn’t pursue the matter further here (see Jacobsen and Richardson 1971 and the contribution of Richard Ascough 2025 in this issue).

Of all the many plants Allegro might have chosen to make such a claim about, the mandrake seems a particularly unlikely choice. In addition to its many remarkable properties, which included the promotion of fertility, its most notable feature is its root, which was thought to resemble humans in their male and female forms (Figure 30). This unusual shape likely stands behind Otto Schrader’s early suggestion that the name was rooted in the Old Persian merdum gijâ (“human plant”) (Schrader 1901, pp. 35–36). Images of the mandrake with its root in the form of a human body and its leaves more or less representing its hair abound in medieval and early modern sources. These images often also include a dog based on the recommended practice of tying a rope to the root of the plant and to a hungry dog and then offering the latter meat some way off as a way of avoiding death or injury by trying to pull the mandrake out of the ground oneself. While running toward the meat, the dog also pulls up the mandrake out of the ground. Some images also show humans covering their ears based on the belief that the mandrake cries out when uprooted, which was thought to bring death or madness to those who heard it (see, e.g., BnB, Latin 9333 fol. 37r). A story told by Josephus in the later first century in connection with a plant he called baaras (Bellum judiacum 7.6) closely parallels these stories about the mandrake. Scholars often equate the two plants (e.g., Taylor 2012, p. 317) and occasionally credit Josephus directly for influencing the medieval traditions about the mandrake (Kottek 2011, p. 253).28

Figure 30.

Mandrakes, RARE RBR N-2-1 (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library), ca. 18th cent., p. 1. Public domain.

But whatever the source of the mythology surrounding the plant with its remarkable, human-like root, classical authors like Theophrastus (Enquiry into Animals 9.9.1), Pliny (Natural History 25, 147), and Dioscorides (De Materia Medica 4.76), described the mandrake as having roots, seeds, flowers, and fruit. In short, as long as we have associated the word mandrake with a particular plant, that plant has not been a cryptogam and therefore also not a mushroom.

One of the reasons Allegro was able, or thought he was, to turn mandrakes into mushrooms, was his ability to seize upon a single similarity in an item while ignoring the rest, even, as in the case of the mandrake, where that involved its most distinctive feature, namely its human-shaped root. If any part of anything was roughly the same shape as a penis, vulva, or mushroom, it was enough for Allegro to get his etymological imagination working in order to come up with a Sumerian root-word supposedly underpinning it. Where etymology failed Allegro he would turn instead, as a means to get what he wanted, to reading reality as a kind of allegory or metaphor. It was this, rather than his linguistic or historical training, that made it possible for him to assert, for example, that the “ancients saw the glowing orb [the sun] as the tip of the divine penis, rising to white heat as it approached its zenith, then turning to a deep red, characteristic of the fully distended glans penis, as it plunged into the earthly vagina” (Allegro 2009, p. 24). Or again, regarding the sons of the Old Testament Patriarch Isaac, that “Jacob is the stem of the fungus, and his ‘red-skinned’ brother Esau [see Genesis 25:25] is the scarlet canopy of the Amanita muscaria” (ibid., p. 138). Even in the passage from the Gospel of Matthew, where St. Peter is instructed to find a shekel in the mouth of a fish he catches to pay the temple tax (chap. 17), Allegro imagines that the “fish’s mouth also has a sexual connotation, being envisaged as the large lips of the woman’s genitals…To have a shekel (bolt) in the fish’s mouth’ was probably a euphemism for coitus” (ibid., p. 45). In short it was not without reason that fourteen prominent scholars of ancient Near Eastern languages, including G.R. Driver, Allegro’s own doctoral mentor at Oxford, and, as it happens, two of my former professors,29 wrote a letter to the Times (16 May 1970) damning the book as “an essay in fantasy rather than philology.” When I mentioned that I was working on this article, a colleague of mine remarked off-handedly: “I thought this stuff was long dead. Not surprising I guess given these times.” And in fact were it not for the ongoing efforts of the PMTs to revive Allegro, we should probably not be having this discussion. By grafting their own project upon his the PMTs have, to some degree at least, kept his work from sinking into obscurity under its own weight. In this way they have, in effect, provided Allego with a kind of ongoing patronage. It has been part of my hope in the present article to show that besides being Allegro’s promoters the PMTs are also his true children in the sense of being his methodological heirs. What Allegro did with words to make them refer to penises, vulvas, and mushrooms, the PMT’s have also done with images to make them depict hidden psychoactive mushrooms.

It has not been my purpose in this article to argue that psychoactive mushrooms never appear in Early Christian or Medieval art. If they do the honest historian will be eager to know. Personally I see no reason they should not appear. But claims of their presence and assertions regarding the meaning of that presence must be based upon good evidence that has been weighed and evaluated in a coherent, credible and accessible way. This is where the PMTs fall short. R. Gordon Wasson once recounted how in 1956 an archaeologist friend warned him to “beware of seeing mushrooms everywhere” (Wasson et al. 1978, p. 12). It was advice he seems to have heeded since we find him several decades latter saying: “I have always been afraid of being too inclusive in my statements—that I accept anything shaped as a mushroom as being a mushroom” (Wasson in Forte 1997, p. 88). The PMTs do not share this inhibition and tend to aim instead at being inclusive to the point of not only accepting things shaped as mushrooms as mushrooms, but a great many other things not shaped as mushrooms as mushrooms as well.

An overarching justification for doing so is provided by John A. Rush, whom Jan Irvin says, “argues convincingly for the prevalence of the historical, religious use of hallucinogenic mushrooms in Christianity” (Rush 2011, back cover). Carl Ruck, for his part, praises Rush for going “beyond the identification of putative fungal shapes in the religious art of Europe,” to provide “an eloquent and sophisticated context for their significance, a kind of grammar of symbolic forms” (ibid.). The index of Rush’s 2011 book includes a list of things he counts as “mushroom motifs”: alb, angel, blood, book, bread, breast, cape, cross, curlicues, dove, fleur-de-lis, flowers, foot stool, globe, globe-cross, golden globe, world globe, hat, hems, mushroom-tree, penis, pose, rock, sash, shape, shield, shoe, shoulder, skull, sleeve, solar plexus, sole/soul, stocking, stole, thumb-stalk, trefoil, three-mushroom, trumpet, vapors, wing. This list, in addition, fails to include a number of other “mushroom motifs” discussed in the book, including for example, gems and halos.

How is it possible that so many things can represent mushrooms? In some cases Rush’s approach is quite simple. For example, many, if not most, of his identifications have to do with “discovering” mushroom shapes in the folds of clothes in much the same way that children imagine they see shapes of animals in clouds. As he says in a section headed “The Mushroom with a Thousand Faces”: “Hiding mushrooms within clothing is the most common representation over a period of 1500 years” (Rush 2011, p. 64). He follows the same approach to finding mushrooms in cracks in the ground (Plates 2:7 and 2:16). Another prominent criteria is that anything that has spots and/or is red and/or is round = Amanita muscaria. For example, one of the standard features of the iconography of St. Jerome, the 4th century translator of the Latin Vulgate, is a large, round, red cardinal’s hat. Sometimes the saint wears it, but other times it is somewhere else in the picture, very often hanging on a wall. Being round and red, but lacking spots, Rush identifies it as a “mushroom-hat” (Plate 3:76). And, consistent with what we have seen earlier in connection with Adam and Eve’s fig leaves, round things that aren’t red and don’t have dots also count for mushrooms. One of the most striking examples of this is Rush’s claim that halos “represent the experience of the mushroom” (Rush 2011, p. 240). Elsewhere, showing that shape is not an essential when identifying an object as a mushroom, Rush shows us a picture of two angels wearing red shoes with white dots at the baptism of Jesus. These are, of course, not round, but to Rush they still count as “Amanita shoes” (Plate 3:16). He tells us that shoe-mushrooms, are “always red, and often accompanied with white dots” (Rush 2011, p. 348), implying apparently that being red is enough to identify shoes as mushrooms, even when, besides not being round, they don’t have dots. Rush also counts other non-round red things with white dots as Amanita muscaria, as for example, Salome’s dress (Plate 3:44) and a seat cushion in the 8th century Codex Aureus (Plate 2:18, cf. also 2: 26a). Rush never seems to be at a loss when providing explanations for his identifications. In the latter case he justifies it by saying that “these were hard times for the Church more so in Western than Eastern Europe. In order to hide the mystery, it must be contained within common items; few would connect a red cushion to a mushroom cap” (Rush 2011, p. 162).

The images in many of Rush’s plates are low resolution or blurry making it impossible to discern whether what he says about them is accurate. In at least some cases his claims can be tested against clearer, higher-resolution images. So, for example, Rush claims that Taddeo Crivelli’s Jerome in the Desert, depicts the saint “drinking blood—’blood is life’ (Count Dracula)” (Plate 7:36). What Jerome is actually doing in the picture is kissing the feet of Jesus on the cross, as is made clear by the fact that there is no blood where Jerome’s lips make contact. Another example is where Rush offers a hopelessly blurry image of the fountain in the Ghent Alterpiece and urges his readers to “Notice the mushroom at the base of the fountain” (3:63a). (He credits this one to Jan Irvin [Rush 2011, p. 250]). Once again, a clearer picture reveals that it is not a mushroom at all but a water-spouting mascaron. In yet another case, Rush claims that the image of the second day of creation in the Great Canterbury Psalter depicts “Cherubs, each of whom is holding a mysterious substance, probably a mushroom cap” (Rush 2011, p. 201). And again, even though the claim cannot be tested by the low-quality image provided by Rush in Plate 3:18b, a better picture reveals that the cherubs are actually holding nothing in their hands.

By adopting this kind of approach Rush and other PMTs are indeed able to vastly expand their corpus of alleged examples of psychedelic mushrooms hidden in Early Christian and Medieval art. But not without a cost in terms of their credibility. There are, for example, likely hundreds of images of Saint Jerome with his red hat and countless thousands of images of halos. Would Rush have us believe that every artist who depicted either of these was, as it were, in on the secret? And if not how does he propose we tell the halos and hats of the two different groups of artists apart so as to be able to discern which hats and halos count in support of his theory and which do not? Seemingly all that is needed from Rush’s perspective to make an item into a mushroom is to connect its name to the word mushroom with a hyphen—e.g., “book-mushroom,” “foot-mushroom,” breast-mushroom,” “rock-mushroom”—no matter how unlike a mushroom that item may appear.

Hence when comparing the approaches of Wasson and Rush it is clearly the former that holds more promise for the future of the question. Even supposing that Wasson was incorrect in rejecting the identification of the Plaincourault tree as a mushroom, surely it is better to err in a single instance due to over caution than in a thousand instances due to a near-total lack of caution.

In our discussion of Allegro’s and the PMTs’ interpretation of the Plaincourault fresco and other works of Medieval art we have noted that in the case of a handful of depictions of trees the crowns actually do look like mushrooms. The most striking example for me, as I said above, is the Triumphal Entry scene from Saint-Martin, Nohant-Vic, where the crowns of the palm trees really do resemble mushroom caps. Is it possible then that the Medieval artist(s) who made the picture actually patterned these foliage heads after mushrooms? Yes, it is possible. But if they did we have no idea at present as to their reason for doing so, any more than we know why they chose to make the caps on adjacent trees resemble diamonds. The Medieval art treasures of Hildesheim, the Bernward Column, Doors, and Gospels, along with the painted ceiling of Saint Michael’s church have regularly fallen victim to PMTs’ speculations. But as Hildesheim historian Bernard Gallistl writes:

…the question of a possible subtext with psychedelic mushrooms is primarily a methodological one. The hidden symbolism in a picture can only be proven from the available textual sources. In my more than 30 years of experience as a manuscript expert at the Hildesheim Cathedral Library and researcher of the Hildesheim Middle Ages—preferably the 10th and 11th centuries—I have yet to come across a text in which I can see evidence of symbolism of this kind.30

And so there is our problem, if hundreds of Early Christian and Medieval images really did contain hidden pictures of psychedelic mushrooms painted by adherents of Allegro’s “old tradition,” why didn’t anyone ever mention it? It hardly counts as evidence if the only answer that can ultimately be given is that the members of that tradition must have been “very good at keeping secrets.” And then finally, why are there so few clear examples of mushrooms in Early Christian and Medieval art?

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Ruck et al. (1979, pp. 145–46). In a personal communication (12 October 2017) Ruck wrote: “As the only Classical scholar in the group, I invented the neologism.” |

| 2 | I have discussed the PMTs’ treatment of this image at length in (Huggins 2022). |

| 3 | This in spite of the fact that Allegro was in no sense pro-entheogens. Allegro’s purpose in writing Sacred Mushroom, as G. Christian Greer points our, was to “delegitimize Christianity, not to glorify the fly agaric mushrooms” (Greer 2025, p. 80). Allegro in no way endorsed the cult of mushrooms he claimed he had uncovered. He says rather that it “fully deserved all the abusive epithets heaped upon its perversions by the Romans when they tried to suppress the ‘Christians’” (Allegro 2013, p. 18). Though one might ask what evidence Allegro has in mind that might indicate that the Romans ever heaped abusive epithets upon the Christians for practicing the kind of religion he describes in Sacred Mushroom. In addition, and perhaps more importantly, the religion Allegro says emerged in consequence of the use of psychedelic mushrooms, fails to resemble anything remotely similar to the widely described religious experiences of psychonauts. |

| 4 | This was not the first time Rougé mentioned the Plaincourault fresco. He did so as well, for example, in the April 1907 Revue des traditions populaires, he writes: “A droite de l’autel, Adam et Eve mangent le fruit défendu. ‘Ce fruit’ a l’aspect d’un champignon” (Rougé 1909, p. 126). |

| 5 | Information as to the color of the tree provided by Carolina Sarrade of the Centre d’études supérieures de civilisation médiévale (CESCM), Université Poitiers, who writes: “L’arbre et ses ramifications sont entièrement peinte en ocre rouge, avec des rehauts blancs sous la forme de perles et des traits horizontaux” (email to author, 9 November 2021). |

| 6 | Émile Boudier: “…l’artiste me semble avoir représenté Éve plutôt souffrant de coliques que honteuse, à la manière dont elle se tient le ventre à deux mains et serre les jambes” (in Marchand and Boudier 1911, p. 33). See, e.g., John Ramsbottom: “Eve has eaten of the tree, judging from her attitude. At this period fungi were only regarded from their good or bad gastronomic qualities” (Ramsbottom 1923, p. 26), and R. T. Rolfe and F. W. Rolfe: “Eve, having eaten of the forbidden fruit, appears from her attitide to be in some doubt as to its after effects, which it is gratifying to know caused her no serious harm” (Rolfe and Rolfe 1925, p. 291). |

| 7 | See also Wasson in (Wasson et al. 1986, pp. 76–77; Wasson and Doniger O’Flaherty 1968, pp. 220–21). |

| 8 | Which she did on 2 April 1959 (Wasson and Doniger O’Flaherty 1968, p. 179). |

| 9 | Erwin Panofsky to R. Gordon Wasson (2 May 1952). See, Panofsky, Erwin, 1950–1953. Tina and R. Gordon Wasson Ethnomycological Collection Archives, ecb00001, Series IV, drawer: W3.2, Folder: 20. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University. |

| 10 | “The influence of Wasson’s writing can be seen in the subsequent development of an entire subgenre of entheogenic literature, much of which has little to recommend it from the scholarly point of view” (Miller 2014, p. 15). |

| 11 | R. Gordon Wasson had also attempted to blend the two trees of Genesis: “They figure as two trees but they stem back to the same archetype. They are two names of one tree” (Wasson and Doniger O’Flaherty 1968, pp. 220–21). Wasson attributes the division of the two trees to a “clumsily executed” conflation of sources. Although I am not aware of what Wasson’s source for such a claim might be, the question of multiple sources in the early chapters of Genesis is a modern one that had no influence on shaping the development of Early Christian and Medieval iconography. |

| 12 | Email from Carolina Sarrade to the author (9 November 2021). |

| 13 | Although, to be sure, medieval painters often had difficulty depicting plausible breasts. See, e.g., The scene of Adam and Eve liberated from Hell in the near by Saint-Martin, Nohant Vic. Also, the First Bible of Charles the Bald (Bible de Vivien), fol. 10v and Pierpont Morgan Library, MS M.43, fol. 7v. |

| 14 | See, in addition, works that describe the painting methods used, e.g., (Taralon 1968; Kupfer 1982; Sarrade 2013). |

| 15 | Sarrade informs me that the greenish color seen along the lower edge of Eve’s fig leaf is not a remainder of green pigment, but was caused by oxidation (Sarrade to author [9 November 2021]). |

| 16 | Vindobonensis 2554 is a copy of the Bible Moralisée. See also, British Library (=BL): Add MS 18719, fol. 1r (c. 1280–c. 1295); BL, MS. Bodl. 270b fol. 1v (1226–1275); Tiberius Psalter, BL, MS Cotton, Tiberius C. VI, f. 7v (c. 1175–1250); BL, Royal MS 19, D III, fol. 3r (1411); Austrian National Library, Codex Vindobonensis 1179, fol. 1v. (late 13th cent.); Holkham Bible, BL, Add MS 47682, fol. 2r (c 1327–1335); and BL, Royal 15 D III, fol. 3v. It is this theme that stands behind William Blake’s famous frontispiece to his Europe in Prophesy (1794) titled “The Ancient of Days.” |

| 17 | For further discussion see (Huggins 2024, p. 5). |

| 18 | In this picture the areas under discs are lighter due to their lack of exposure to the elements. |

| 19 | Later, not long after our period, the serpent would come to be depicted with a woman’s face, often mirroring that of Eve herself. One explanation was that the devil did this so as to approach Eve in a form she would be more inclined to listen to, i.e., one like herself (see Petrus Comestor, Historia Libri Genesis, in Migne, Patrologia Latina CXCVIII, 1072). The most remarkable example of this female-faced serpent that I have seen is that of Giovanni della Robbia (1515), now in the Walters Gallery in Baltimore. When viewed from the proper angle—the picture in the link comes nowhere near to capturing it—the tempter’s face seems filled with confidential compassion and sisterly concern. |

| 20 | In Eve’s hand in Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece, 1432. PMT John A. Rush identifies it instead as a “fiery bush” and as “the fruiting body of a recently resurrected Amanita muscaria” (Pl. 3.63b). |

| 21 | Erwin Panofsky to R. Gordon Wasson (2 May 1952), 1, in the Tina and R. Gordon Wasson Ethnomycological Collection Archives, ecb00001, Series IV, drawer, W3.2, Folder: 20. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University. |

| 22 | I have discussed this at length elsewhere. See (Huggins 2024, pp. 14–19). |

| 23 | The Latin Vulgate edition of John informs us that the boughs were palm branches (ramos palmarum). Neither Matthew nor Mark identify a particular species of tree. |

| 24 | See Reichenau Gospel Book (BSB Clm 23338), fol. 184v; The Pericopes Book of Henry II (Clm. 4452) fols. 131v, 200r (1007–1012); The Bamberg Apocalypse (Staatsbibliothek Bamberg Msc. Bibl. 140) fol. 57r (c. 1010); Gospel Book of Otto III (BSB Clm 4453) fol. 34v (c. 1010 AD). The similarity in style could point to one miniature artist or group of artists. See, for example, the nearly identical depictions of Zachaeus in a multi-branched tree with a mushroom-like top in the Reichenau Gospel Book fol. 184v and the Pericopies Book of Henry II, fol. 200r. |

| 25 | Here we may see the same tree depicted on the right (3rd day) in a more deteriorated form than on the left (4th day). |

| 26 | “Namtar” means “fate, destiny” in Sumerian and is also the name of a deity associated with the realm of the dead. Sacrifices are said to be offered to Namtar in the Sumerian The Death of Gilgameš (l. 10, another version from Nibru) and The Death of Ur-Namma (l. 108, a version from Nibru). The latter work also includes an offering to Namtar’s wife Ḫušbisag (l. 112). In the Akkadian stories, Namtar appears as the vizier of Ereshkigal, queen of the underworld (see esp. the story Nergal and Ereshkigal. See, further, Frayne and Stuckey 2021, pp. 223–24). “Agar” means “field” (Cohen 2023, p. 44). |

| 27 | In the book, words marked with an asterisk are hypothetical. |

| 28 | Curiously Aelius in the 2nd–3rd century CE tells the same story of the Paeony (De natura animalium 3.191). |

| 29 | D.J. Wiseman and Geza Vermes. Judith Butler Brown, described the latter as her father’s “most searching critic” (Brown 2005, p. 180). |

| 30 | From a statement kindly prepared at the author’s request, 27 November 2023. For a general treatment of the Bernward Doors and Column see (Gallistl 1990, 1993). |

References

- Allegro, John Marco. 2009. The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross: A Study of the Nature and Origins of Christianity within the Fertility Cults of the Ancient Near East. N.p.: Gnostic Media. Originally published as 1970. London: Hodder and Stoughton. [Google Scholar]

- Allegro, John Marco. 2013. End of the Road, 2nd ed. Edited by John Bolender. Introduction Judith Anne Brown. Additional Articles by Franco Fabbro and John Bolender. Piketon: Rousseau. Originally published as 1970. London: MacGibbin and Kee. [Google Scholar]

- Ascough, Richard S. 2025. John Allegro and the Psychedelic Mysteries Hypothesis. Religions 16: 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Chris, Lynn Osburn, and Judy Osburn. 1995. Green Gold the Tree of Life. Marijuana in Magic and Religion. Frazier Park: Access Unlimited. [Google Scholar]

- Brightman, Frank. 1966. The Oxford Book of Flowerless Plants. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brinckman, Albert E. 1906. Baumstilisierungen in der mittelalterlichen malerei. Strassburg: J. H. E. Heitz. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Jerry B., and Julie M. Brown. 2016. Psychedelic Gospels: The Secret History of Hallucinogens in Christianity. Rochester: Park Street Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Judith Anne. 2005. John Marco Allegro: The Maverick of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Celdrán, José, and Carl A. P. Ruck. 2002. Daturas for the Virgin. Entheos 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Mark E. 2023. An Annotated Sumerian Dictionary. University Park: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Jerrold S. 1971. Allegrissimo. The New York Review of Books, April 22. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 1964. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Translated by Willard R. Trask. Princeton: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, Robert. 1997. A Conversation with R. Gordon Wasson. In Entheogens and the Future of Religion. Edited by Robert Forte. San Francisco: Council for Spiritual Practice, pp. 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Frayne, Douglas R., and Johanna H. Stuckey. 2021. A Handbook of Gods and Goddesses of the Ancient Near East. Illust. Stéphane Beaulieu. University Park: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Frend, W. H. C. 1970. Worshipping the Red Mushroom. The New York Review of Books, December 17, pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gallistl, Bernhard. 1990. Die Bronzetüren Bischof Bernwards im Dom zu Hildesheim. Frieburg: Vienna: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Gallistl, Bernhard. 1993. Die Bernwardsäule und die Michaeliskirche zu Hildesheim. Hildesheim, Zurich and New York: Georg Olms. [Google Scholar]

- Gartz, Jochen. 1993. Narrenschwämme: Psychotrope Pilze in Europa. Basel: Editions Heuwinkel. [Google Scholar]

- Gartz, Jochen. 1996. Magic Mushrooms Around the World. Los Angeles: LIS. [Google Scholar]

- Gettings, Fred. 1987. Secret Symbolism in Occult Art. New York: Harmony Books. [Google Scholar]

- Goff, Matthew James. 2025. Odd Conspiracies: John Allegro, Sacred Mushrooms, and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Religions 16: 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, J. Christian. 2025. Historians on Drugs: Toward an Empirical Historiography of Global Psychedelic Cultures. The South Atlantic Quarterly 124: 263–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, Mark, Carl A. P. Ruck, and Blaise D. Staples. 2001. Conjuring Eden: Art and the Entheogenic Vision of Paradise. Entheos 1: 13–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, Michael. 2006. Wasson and Allegro on the Tree of Knowledge as Amanita. Hoffman indicates that this article appeared in the Journal of Higher Criticism dating it 2006, not to be confused apparently with the journal of that name edited by Robert M. Price from 1994–2003 which was then revived in 2018. Hoffman’s article does not appear in the index of the earlier volumes.

- Huggins, Ronald V. 2022. Dizzy, Dancing or Dying? The Misappropriation of MS. Bodl. 602, fol. 27v, as “Evidence” for Psychedelic Mushrooms in Christian Art. Fragments 1.1: 1–25, (Fragments is my personal journal for odds and ends available only on academia.edu). [Google Scholar]

- Huggins, Ronald V. 2024. Foraging for Psychedelic Mushrooms in the Wrong Forest: The Great Canterbury Psalter as a Medieval Test Case. Die Bibel in der Kunst/Bible in the Arts 8: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Irvin, Jan R. 2008. The Holy Mushroom: Evidence of Mushrooms in Judeo-Christianity. Kindle ed. with Jack Herer. Gnostic Media. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, Thorkild, and Cyril Charles Richardson. 1971. Mr. Allegro Among the Mushrooms: Two Reviews of John M. Allegro’s The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross. Union Seminary Quarterly Review 26: 235–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kottek, Samuel S. 2011. Josephus on Poisoning and Magic Cures Or, on the Meaning of Pharmakon. In Flavius Josephus: Interpretation and History. Edited by Menahem Mor, Pnina Stern and Jack Pastor. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 247–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer, Marcia Ann. 1982. The Romanesque Frescoes in the Church of Saint-Martin at Nohant-Vicq. Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, Nestor Léon, and Jean Louis Émile Boudier. 1911. La fresque de Plaincourault (Indre). Bulletin trimestriel de la Société mycologique de France 27. (pp. 31–32, Pl. 0, p. 527).

- Merrifield, Mary P. 1952. The Art of Fresco Painting in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Introduction by A. C. Sewter. London: Tiranti. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Richard J. 2014. Drugged: The Science and Culture Behind Psychotropic Drugs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsbottom, John. 1923. A Handbook of the Larger British Fungi. London: Trustees of the British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe, Robert Thatcher, and F. W. Rolfe. 1925. The Romance of the Fungus World. Foreword by J. Ramsbottom. London: Chapman and Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Rougé, Jacques M. 1907. Un miracle de Saint Martin sur une fresque berrichonne. Revue des Traditions Populaires 22: 126–28, Repr. from the January 1907 Revue du Berry. [Google Scholar]

- Rougé, Jacques M. 1909. Folk-lore de la Touraine, Nouvelle Contribution. Gazette Médicale du Centre, 213–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ruck, Carl A. P., and Mark A. Hoffman. 2012. The Effluents of Deity: Alchemy and Psychoactive Sacraments in Medieval and Renaissance Art. Durham: Carolina Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruck, Carl A. P., Jeremy Bigwood, Danny Staples, Jonathan Ott, and R. Gordon Wasson. 1979. Entheogens. Journal of Psychedelic Drugs 11: 145–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rush, John A. 2011. The Mushroom in Christian Art: The Identity of Jesus in the Development of Christianity. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Samorini, Giorgio. 1998. “Mushroom Trees” in Christian Art. Eleusis n.s. 1: 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Samorini, Giorgio. 2001. New Data from the Ethnomycology of Psychoactive Mushrooms. International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms 3: 257–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrade, Carolina. 2013. Comprendre la technique des peintures romanes par le relevé stratigraphique. In Situ 22.

- Sarrade-Cobos, Carolina. 2006. La Chapelle de Plaincourault (Indre), technique et iconographie des peintures romanes de l’abside. Master’s thesis, Université de Poitiers, Poitiers, France. [Google Scholar]

- Schrader, Otto. 1901. Reallexikon der indogermanischen altertumskunde, 1. Band. Strassburg: Trübner. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, Johannes. 1999. Das Deckenbild der Michaeliskirche zu Hildesheim. Königsteim im Taunus: K. R. Langewiesche. [Google Scholar]

- Taralon, Jean. 1968. Observations techniques sur la voûte de la nef de St.-Savin. In Bulletin de la Société nationale des Antiquaires de France. pp. 247–57. (accessed on 16 September 2025). [Google Scholar]