Tracing Sacred Intercession in Childbirth Across Byzantine Tradition and Its Western Reception, from the Virgin’s Girdle to Saints Julitta and Kerykos

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Mary’s Girdle and Protective Devotion in Byzantium

4. The Girdle Cult: Origins and Ritual Use

5. Sacred Textiles and Visual Motifs of Protection

6. The Girdle’s Medieval Migration

7. Saints Julitta and Kerykos as Intercessors in Childbirth

8. The Story of Saints Julitta and Kerykos

9. Some Medieval Presentations of the Saints

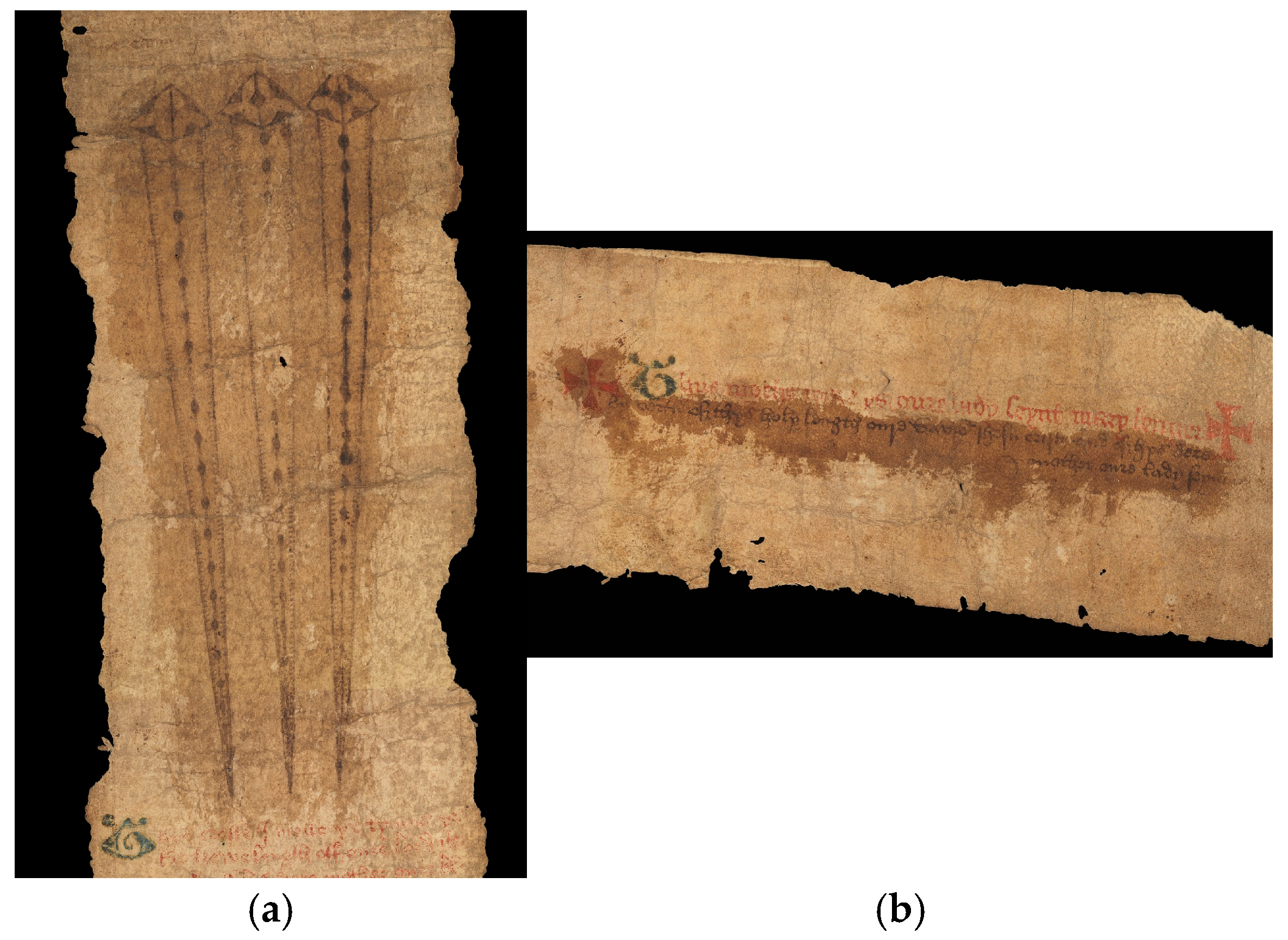

10. Vernacular Manuscripts and “Birth Girdle” Scrolls

11. Byzantine Perspectives and Theological Connections

12. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The visual corpus derives from the dataset compiled, surveying depictions of Saints Julitta and Kerykos in healing contexts across 68 medieval churches, primarily in the Byzantine world (Cappadocia, Greece, the Balkans, Cyprus), but also in Italy, Georgia, Coptic Egypt, and Ethiopia. See (Ünser 2022). |

| 2 | For a newer critical edition with scholarly apparatus, see (Laga 1992). |

| 3 | Also see the Life of Michael the Synkellos (815–843), where the saint’s mother prays persistently for a male child and her request is eventually fulfilled, though the Virgin Mary is not explicitly invoked; see (Cunningham 1991, pp. 45, 47). |

| 4 | O thou who delivered Eve from her intense suffering/And dost sympathetically watch over my birth pangs (For God <was born> of Thee without the natural pain of childbirth) (Talbot 2014, p. 267). |

| 5 | It is worth recalling that in Genesis 3:16, Eve is condemned to suffer pain in childbirth as a result of original sin. Building on this, Byzantine theologians and artists later developed typological parallels between Eve and Mary. The poem reflects this tradition, as the speaker expresses her belief that, through Mary, the burden of labor is lightened. For further information about the subject see (Guldan 1966; Graef 1963). |

| 6 | The attribution of the Life of the Virgin to Maximos the Confessor has been a subject of scholarly debate. While S. Shoemaker (2016) argues for a seventh-century origin, recent scholarship by Booth (2015) and Cunningham (2022) has challenged this, providing strong arguments for a later, tenth-century dating. |

| 7 | This doctrine, directly related to the Original Sin, essentially focuses on the belief that Mary’s parents conceived her without sexual desire and that she was free from original sin from the very moment she was conceived in her mother’s womb. While this idea was accepted in the West from the beginning, it remained a matter of debate in Byzantium for some time and was later largely rejected. For a brief discussion of the topic from the Byzantine perspective, see (Panou 2018, pp. 89–90). For details of the doctrine and its development in the West, see (Nixon 2004, pp. 13–16, 72–76). |

| 8 | Germanos’ texts are important because they emphasize Mary’s role as a mediator for the faithful rather than theological teachings. It should also be noted that the belt had a general protective function for Constantinople. For his words on the girdle and its protective power, see (Cunningham 2015, p. 143). |

| 9 | This imperial veneration reflects the widespread belief that fabrics associated with Mary possessed protective properties. As Dell’Acqua notes, “the fabrics which had been in contact with the body of the Holy Virgin became contact relics” (Dell’Acqua 2019, p. 284). |

| 10 | Theodore was born and died in Sykeon, a village in Galatia, during the reign of Justinian I. His life was recorded by his disciple, Georgios of Sykeon. Three different versions of Theodore’s life exist in BHG 1748 which is the longer version and 2 shorter versions in BHG 1749b and c. These texts have all been edited by Festugière and he also provides a French translation and a commentary to the longer Life (Westberg 2012, pp. 227–28). For a short version in English translation see (Dawes and Baynes 1948). |

| 11 | In the ancient Hittite context of Anatolia, for example, girdles featured prominently in birth rituals (Chavalas 2014, p. 292). Similarly, Greek and Roman customs had expectant mothers untie their belts as labor approached, sometimes dedicating these belts to goddesses like Artemis. Narratives of binding and unbinding as metaphors for conception and parturition are found widely in antiquity and even in later Turkish folk culture (Dilling 1913–1914, pp. 406–8). In practical medical literature too, a link was drawn between girdles and pregnancy: the 2nd-century physician Soranus of Ephesus advised women to wear a loose belt during pregnancy for support, but to remove it in the final month. An ancient Chinese physician offered nearly identical counsel, reflecting a cross-cultural intuition about the physical effects of abdominal binding (Dilling 1913–1914, pp. 408–9). |

| 12 | Ball argues that the fourth century marked a turning point when “Christians began to specially mark their textiles as Christian with iconography identifying them as such,” moving beyond the earlier practice of simply using generic textiles in Christian contexts (Ball 2018, p. 235). |

| 13 | The strategic placement and repetitive use of specific depictions functioning as charms has been interpreted by several scholars as evidence of protective rather than merely didactic purposes (Maguire 1990, pp. 216, 220; Ball 2016, pp. 56, 59; Lam 2019, pp. 55, 57–58; Morgan 2018, pp. 45, 48). However, Davis offers a more nuanced view, noting that protective uses often coexisted with mimetic and Christological purposes (Davis 2005, pp. 352–53, 359). |

| 14 | Lam describes the Boston clavus as depicting “the Visitation scene twice, alternating with heavily abraded depictions of what is probably the Annunciation,” noting that while the Annunciation scenes are damaged, they almost certainly depict the Annunciation (Lam 2019, p. 57, figure 2.4). |

| 15 | After its discovery, it was transferred to the Vatican Museums in 1906. Its condition indicates it was once attached to another piece of fabric. It is believed to be part of a larger sheet of repeating medallions that includes a Nativity scene in the Vatican’s collection. While its origin is debated, with attributions to an Alexandrian or Syrian workshop (based on design) and an imperial workshop in Constantinople (based on technique), its high quality suggests a prestigious source (The Vatican Collections 1982, pp. 102–3; Thomas 2012, pp. 152–53; Cormack and Vassilaki 2008, p. 389). For a technical and iconographical study of the Vatican textile with Annunciation and Nativity scenes see (Martiniani-Reber 1986). For the image see (Thomas 2012, p. 152, pl. 101). |

| 16 | Comparable strategies can also be found in other Late Antique religious art. Crostini has shown that the synagogue murals at Dura-Europos (c. 240 CE), depicting Pharaoh’s daughter and the widow of Sarepta with exposed breasts, were designed not as scandalous details but as deliberate symbols of maternal presence, fertility, and prophetic authority (Crostini 2023, pp. 206–24). Such examples suggest that the visualization of women’s breasts in sacred narrative, though rare, could function as a powerful shorthand for motherhood and intercession. |

| 17 | Evangelatou demonstrates that the purple thread in Byzantine Annunciation scenes symbolized the Incarnation, the divine Logos “clothing” himself in human flesh within Mary’s virginal womb. Byzantine theologians, particularly Proclos of Constantinople, described Mary’s womb as the “virginal workshop” where the Holy Spirit wove Christ’s human nature from her pure flesh (Evangelatou 2003, p. 265). The iconographic detail of Mary pointing her spindle toward a vessel on her lap, visible in some Byzantine images, has been interpreted as symbolizing the seedless conception within the virginal womb, the miraculous union achieved through the Holy Spirit’s descent rather than human intervention (Evangelatou 2003, pp. 266–67). This theological reading explains why early Byzantine programs like Poreč gave such prominence to textile imagery: the spinning visualized not domestic activity but the mystery of virginal conception and divine Incarnation. |

| 18 | The broader implications of this iconographic program and their varying emphasis on textile imagery, merit separate detailed study but lie beyond the scope of this article’s focus on girdle symbolism. |

| 19 | Lidova’s analysis, which is made in the broader context of Early Byzantine culture, demonstrates that this icon reflects a common religious heritage shared by the entire Christian world, rather than purely Western papal innovation (Lidova 2016, pp. 109, 122, figure 1). Significantly, the painting has been connected to the artistic program of Pope John VII (705–707), creating a direct link to the same papal patronage responsible for the San Marco panel. This connection suggests a coordinated early program of imperial Marian imagery that drew from shared Byzantine theological foundations, indicating that girdle details in such depictions similarly emerged from common devotional concepts. |

| 20 | Lidova also notes the connection of both the Trastevere and San Marco icons to miracle-working traditions (Lidova 2013, p. 171; 2016, p. 111), which suggests that their reception included protective and healing associations alongside theological and imperial meanings. Although these examples do not engage directly with fertility, they indicate that Marian imagery in imperial contexts could also acquire a broader devotional significance. |

| 21 | For rare Eastern examples of this iconography, see the Koimesis scene in the Church of the Virgin Peribleptos (St. Clement) in Ohrid, where the scene appears in the upper right corner (Salvador González 2011, pp. 252–53, figure 6). Another version, dated to the 18th century, appears in a wall painting from the katholikon of the Koimesis Monastery in Delphi, now housed in the Museum of Christian and Byzantine Art, Thessaloniki. |

| 22 | The August 31st feast established by Manuel Komnenos is documented in the Synaxarion of Constantinople, which records the translation of the girdle from Zela to Chalkoprateia (Synaxarion CP, Aug. 31, cols. 935–936). A Byzantine manuscript, dated to 1322–1340 (Oxford, Bodleian Gr. th. f. 1, fol. 53v) depicts this translation ceremony (See the relevant scene from the Digital Bodleian Website, here: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/, accessed on 20 August 2025). |

| 23 | For the cult of the Virgin’s girdle in Italy, especially in Prato, where a relic believed to be her belt is preserved, and its widespread visual representations in Western Marian art, see (Eliason 2004). Also see (Dell’Acqua 2019) for Pisa in particular. |

| 24 | There are some opinions that the fragments or possibly the entirety of the Virgin’s girdle are believed to have been transferred to the West during or after the Latin occupation of Constantinople in 1204. Among those distributing relics was Nivelon de Chérisy, a prominent cleric who served as Bishop of Soissons and later became Latin Archbishop of Thessaloniki during the Fourth Crusade. See (Lester 2017; also Klein 2004, pp. 289, 302). |

| 25 | According to a legend of uncertain origin, a strip of the Virgin’s girdle was brought to Prato, from Jerusalem in 1140 and was subsequently housed in the church of Santo Stefano in 1174 (Eliason 2004, pp. 2, 11; Cadogan 2009, p. 107; Dell’Acqua 2019, pp. 293–94). |

| 26 | Prato’s relic attracted considerable devotion and economic benefit. Public displays coincided with three-day commercial fairs, drawing pilgrims on major Marian feasts. Even after coming under Florentine control in 1351, Prato retained its precious relic, and it spurred devotional innovations in Florence itself, including depictions of the pregnant Mary with fabric marking her swollen belly in the new image of the Madonna del parto (Dell’Acqua 2019, pp. 293–94). For the institutional and political dimensions of Prato’s girdle cult, see (Cadogan 2009). |

| 27 | For the theological exaltation of Mary’s virginity in Early Byzantine art, see (Lidova 2016, p. 109). Lidova shows how the Maria Regina type expressed Marian theology through virginity and regal status. Although distinct from our discussion about the maternal symbolism attached to Mary’s girdle in devotional practice, these perspectives illustrate c in which the paradox of virginity and motherhood was negotiated. |

| 28 | The feast known in Byzantium as Koimesis, referred to in the Western tradition as the “Dormition”, was regarded as the most important Marian feast in late medieval England (Morse 2014, p. 201). For the scenes and on the later development of the girdle relic see (Mimouni 1995, pp. 617–28, in particular). |

| 29 | The frequent depiction of Mary bestowing the girdle upon Thomas in Dormition and Assumption scenes, especially in Italian Renaissance painting, attests to the relic’s visual and devotional prominence. Such imagery first appeared in the latter half of the 14th century and gained popularity throughout the 15th century. See (Eliason 2004, esp. figures 6, 12–16 and following; also Cassidy 1988). |

| 30 | This manuscript contains a Venetian translation of the Latin Vita Rhythmica Mariae atque Salvatoris, dating to the second half of the 15th century. The work represents a rich anthology of apocryphal texts interwoven with canonical narratives, including the Transitus Mariae, translated by Father Guielmo da Padoa for the religious and mercantile classes of the Veneto region. The manuscript’s nearly 300 illustrations functioned as a popular Biblia Pauperum, making complex theological narratives accessible through visual storytelling. For the critical edition and comprehensive analysis of this vernacular devotional text and its iconographic program, see (Cornagliotti and Parnigoni 2023). |

| 31 | After the suggestion of the editor I removed it from here. |

| 32 | The accompanying Italian vernacular text, preserved on fol. 242r and completed by modern editors, reads: “Et habiando santo Thomado conplido questa horaçione, de presente la vergene Maria, la qualle si sè fon[c. 242r]tana de tute graçie, de presente ella si se deçensse llo çençello che ella aveva intorno e ssi llo gità çusso a santo Tomado; e quello çençello si fo quello lo qualle li apostolli si lli aveva çento intorno. Et abiando reçevudo santo Thomado quello/çençello, ello con pietossa revellençia et con grandissima allegreça, ello si llo baxiava, regraçiando la dolçe vergene Maria conmesso lo sso’ benigno Fiiollo che lli aveva conçedudo tanta sollempne graçia, e con divoçione si llo allogà.” (Cornagliotti and Parnigoni 2023, p. 377). |

| 33 | I am grateful to Barbara Crostini for encouraging me to address these questions, which bring out the intersection of gender, authority, and devotion in the cult of the girdle. |

| 34 | For the original version of the image visit the Digital Bodleian from this link: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/f98ab8c9-fe36-4a36-9d73-e8fc3f382e2d/, accessed on 21 October 2025. |

| 35 | In 1538, Bishop Nicholas of Salisbury prohibited midwives from using superstitious objects such as childbirth girdles to assist women in labor (Morse 2014, p. 201). |

| 36 | There are versions and translations of the saints’ lives. As a source containing the information about saints in various versions, see AASS (Junii IV); the Greek “Epic” Martyrdom of the saints (BHG 313y–z); and the Compiled Martyrdom (BHG 314–317). For the edited second versions see (Synaxarion CP p. 821; AB, pp. 192–208). For the Syriac version see (AMS, pp. 254–83); for the Ethiopian version in English (Synaxarion Eth. pp. 497–500 and 1130–31); for the Armenian version (Synaxarion Arm. pp. 349–53. For a recent study that explores the saints’ iconographic features and, in particular, their healing cults as represented in medieval visual culture, especially in church wall paintings, see (Ünser 2022). |

| 37 | In the medieval West, Saint Anna was frequently associated with fertility and childbirth, and her cult has been the subject of several studies. See, for example (Nixon 2004). S. Gerstel has noted that depictions of Anna holding the Virgin Mary in her lap, found in numerous churches, may have appealed to women seeking aid with fertility. In her article on visual sources of female piety, Gerstel further suggests that depictions of sacred women in churches may have addressed female concerns such as fertility, childrearing, and healing. Saint Anna, as the mother of Mary, is among the key figures linked with themes of childbirth and maternity in Byzantine art (Talbot 1998, pp. 97–98). The most comprehensive study of Anna’s cult in the Byzantine world has been undertaken by Panou, who also highlights the saint’s healing associations (Panou 2018). |

| 38 | The saint depicted is Symeon Stylites the Younger, commemorated on May 24 in the Byzantine calendar. Born in Antioch, he lived between 521 and 592 and was associated with the “wondrous mountain” (Gr. θαυμαστῷ ὄρει), a reference to the site of his monastic cult. Though less renowned than the elder Stylite Symeon of Qalat Siman, he was nevertheless venerated as a renowned healer and inspired a devoted following. For a concise account of his life, see (Synaxarion CP, pp. 703–5); also see (Efthymiadis 2011, pp. 52–54; Millar 2014). |

| 39 | For discussions of saintly maternal bonds, see (Drewer 1991–1992, pp. 266–67). |

| 40 | In Byzantine monumental painting, Saints Julitta and Kerykos commonly appear as standing or medallion-framed figures, each holding martyr crosses. From the 8th century onward, Julitta is typically shown holding a cross, while Kerykos, depicted as a small child, adopts an orans posture; sometimes reversed, as in the Theodotus Chapel at Santa Maria Antiqua. Less frequently, they appear in Marian-style compositions, with Julitta holding the child or standing side by side. A notable late Byzantine and post-Byzantine development is the portrayal of Kerykos gesturing to the wound on his head (see Figure 7). Though relatively rare, narrative scenes of the saints’ martyrdom were also depicted, first appearing in the 8th century at Santa Maria Antiqua, but more commonly in Late and Post-Byzantine periods. For a discussion of various iconographic schemes about the saints in question, see (Ünser 2022, Chapter 5). |

| 41 | For the cult of saints in Svaneti region see (Schrade 2016); for their story in Georgian see (Galadza 2018, pp. 100–1; also Garitte 1958, pp. 78, 279–81). |

| 42 | The composition and spatial arrangement of the scene show notable parallels with the depiction found in the Church of Lesnovo Monastery. As for his physiognomy, it follows a broader Byzantine convention observable across multiple regional traditions. In churches throughout Greece and the Balkans, including Agioi Anargyroi in Kastoria, Archangel Gabriel in Lesnovo, and the Virgin Mary in Kučevište, Kerykos consistently appears with adult-like facial features despite his child’s stature. The Lesnovo depiction particularly emphasizes this with a balding pate, a characteristic that, as Hennessy has noted (Hennessy 2008), parallels the iconography of St. Nicholas depicted as spiritually mature from childhood. This “aged infant” convention, typically reserved for the Christ Child to signal divine wisdom, here transforms the three-year-old martyr into a figure of exceptional spiritual precocity. The composition thus creates a theological dialogue between types of sacred childhood: Christ’s divine nature and Kerykos’s premature spiritual maturity achieved through martyrdom. For a detailed discussion of this subject and comparative analysis of other examples following the same iconographic scheme, see (Ünser 2022, pp. 179–80, 206–8, 316–17). |

| 43 | For the festival see (Abakelia 2018, p. 449). |

| 44 | This continuity stands in contrast to Cappadocia, where visual traces of the saints persist but living cult practices gradually diminished, especially following the process of Turkification and Islamisation of Anatolia and the 1923 Greco-Turkish population exchange. The Georgian case thus illustrates an unbroken thread of vernacular devotion that bridges the medieval and modern worlds. |

| 45 | For further information about the chapel see (Belting 1987; Rushforth 1902; Jessop 1999, pp. 236–37; Osborne 2020, pp. 95–136). |

| 46 | The trials and torments of the saints are painted on the east and west walls, while three votive panels dedicated to the saints appear on the south and west walls. In addition, the chapel includes a donor family portrait, representations of unnamed martyr saints, and a monumental Crucifixion scene of Christ. |

| 47 | For the discussion about the theme of motherhood in Santa Maria Antiqua see (Brenk 2021) and (Gianandrea 2021). |

| 48 | For detailed information on the manuscript, see (Smith 1996). |

| 49 | The original texts read by Smith are as follows, respectively: “Si vous estes en ascun anguisse ou travaille d’enfaunt… et vous serrez tost eyde” (Smith 1996, pp. 186, 216) and “Salve decus parvulorum, miles regis angelorum…” (Smith 1996, p. 217). |

| 50 | While the references to the saints in Egerton MS 2781–particularly their invocation in relation to childbirth–are noteworthy, a fuller investigation into the reasons for their inclusion, the potential connection to the female patron who commissioned the manuscript, and whether this reflects a broader devotional cult or simply an isolated instance lies beyond the scope of this study. Likewise, a more detailed examination of the miracles associated with these saints, as outlined elsewhere in the manuscript, and their relationship to the textual and visual content would require a separate, dedicated analysis. For a brief discussion see (Morse 2013, p. 192). |

| 51 | The original text as quoted by Moorat reads as follows: “ffor seynt Ciryk and seynt Julit hys mother desyryd thes gyfts of Almyghty god and owre lorde Jhesu criste graunted hyt unto them and thys ys regestred at rome at seynt John lateranence (sic) in the pryncypall churche in Rome” (Moorat 1962, p. 492). |

| 52 | On the possible influence of Norman intermediaries in this transmission, see (Morse 2013, pp. 191–92), who highlights the role of post-Conquest Anglo-Norman patrons in commissioning manuscripts referencing the saints. Wasyliw (2008, p. 45) similarly notes that the saints’ cults first appear in England after the Norman Conquest, having earlier gained a foothold in Auxerre. |

References

Primary Source

(AB) Van Hooff, Gulielmus, ed. 1882. Sanctorum Cyrici et Julittae. In Acta Graeca Sincera: Nunc Primum Edita, Analecta Bollandiana 1: 192–208.(AASS) Henschenius, G., D. Papebrochius, F. Baertius, and C. Ianningus, eds. 1867. Acta Sanctorum Junii IV. Paris and Rome: Victorem Palmé.(AMS) Bedjan, Paul, ed. 1890. Acta Martyrum et Sanctorum. Vol. 3. Paris and Leipzig: Harrassowitz.(BHG) Halkin, François, ed. 1957. Bibliotheca Hagiographica Graeca. Vols. 1–3. Brussels: Société des Bollandistes.(HSVS) Surius, Laurentius, ed. 1875. Historiae seu vitae sanctorum: Juxta optimam coloniensem editionem. Vol. 6 (Junius). Augustae Taurinorum: Ex typographia Pontificia et Archiepiscopali Eq. Petri Marietti.(PG) Migne, Jacques-Paul, ed. 1865. Patrologia Graeca. Vol. 86. Paris: Imprimérie Catholique.(Synaxarion Arm.) Bayan, George. 1910. Le Synaxaire Arménien de Ter Israël, XI: Mois de Navasard. Patrologia Orientalis 21, no. 5. Paris: Firmin-Didot; Fribourg: Herder.(Synaxarion CP) Delehaye, Hippolyte, ed. 1902. Synaxarium Ecclesiae Constantinopolitanae: Propylaeum ad Acta Sanctorum Novembris. Brussels: Société des Bollandistes.(Synaxarion Eth.) Budge, Ernest Alfred Wallis. 1928. The Book of the Saints of the Ethiopian Church: A Translation of the Ethiopic Synaxarium (መጽሐፈ፡ ስንክሳር፡) Made from the Manuscripts Oriental 660 and 661 in the British Museum. Vols. I–IV (Vol. 2). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Secondary Source

- Abakelia, Nino. 2018. The Change of Meanings of Christian Terms Over Time and Their Interpretation in the Popular Religion of the Georgians. Études Interdisciplinaires en Sciences Humaines (EISH) 5: 445–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, Jennifer L. 2016. Charms: Protective and Auspicious Motifs. In Designing Identity: The Power of Textiles in Late Antiquity. Edited by Thelma K. Thomas. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, pp. 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, Jennifer L. 2018. Textiles: The Emergence of a Christian Identity in Cloth. In The Routledge Handbook to Early Christian Art. Edited by Robin M. Jensen and Mark D. Ellison. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 221–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ballardini, Antonella, and Paola Pogliani. 2013. A Reconstruction of the Oratory of John VII (705–7). In Old Saint Peter’s, Rome. Edited by Rosamond McKitterick, John Osborne, Carol M. Richardson and Joanna Story. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 190–213. [Google Scholar]

- Belting, Hans. 1987. Eine Privatkapelle im frühmittelalterlichen Rom. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 41: 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, Phil. 2015. On The “Life of the Virgin” Attributed to Maximus Confessor. The Journal of Theological Studies 66: 149–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenk, Beat. 2021. A New Chronology for the Worship of Images in Santa Maria Antiqua. In Santa Maria Antiqua: The Sistine Chapel of Early Rome. Edited by Eileen Rubery, Giulia Bordi and John Osborne. London and Turnhout: Harvey Miller Publishers, pp. 461–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cadogan, Jean K. 2009. The Chapel of the Holy Belt in Prato: Piety and Politics in Fourteenth-Century Tuscany. Artibus et Historiae 30: 107–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, Brendan. 1988. The Assumption of the Virgin on the Tabernacle of Orsanmichele. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 51: 174–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavalas, Mark. 2014. Women in the Ancient Near East. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cormack, Robin, and Maria Vassilaki. 2008. Byzantium: 330–1453. London: Royal Academy of Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Cornagliotti, Anna, and Laura Parnigoni, eds. 2023. Il volgarizzamento veneto della Vita rhythmica Mariae atque Salvatoris secondo il ms. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Canon. It. 280: Edizione con note critiche. Illustrations and Iconographic Commentary by Maria Luisa Vicentini. Milano: Ledizioni LediPublishing. [Google Scholar]

- Crostini, Barbara. 2023. Empowering Breasts Women, Widows, and Prophetesses-with-Child at Dura-Europos. In Breastfeeding and Mothering in Antiquity and Early Byzantium. Edited by Stavroula Constantinou and Aspasia Skouroumouni-Stavrinou. London: Routledge, pp. 206–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, Mary B. 1991. trans. and comm. The Life of Michael the Synkellos. Belfast: Byzantine Enterprises. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, Mary B. 2015. Mary as Intercessor in Constantinople during the Iconoclast Period: The Textual Evidence. In Presbeia Theotokou: The Intercessory Role of Mary Across Times and Places in Byzantium, 4th–9th Century. Edited by Leena Mari Peltomaa, Andreas Külzer and Pauline Allen. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences, pp. 139–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, Mary B. 2022. The Virgin Mary in Byzantium, c. 400–1000. Hymns, Homilies and Hagiography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Stephen J. 2005. Fashioning a Divine Body: Coptic Christology and Ritualized Dress. The Harvard Theological Review 98: 335–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, Elizabeth Anna Sophia, and Norman Hepburn Baynes, trans. 1948. Three Byzantine Saints: Contemporary Biographies of St. Daniel the Stylite, St. Theodore of Sykeon and St. John the Almsgiver. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Acqua, Francesca. 2019. The Cintola (Girdle) of Pisa Cathedral, and Mary as Ecclesia. In Le rideau, le voile et le dévoilement du Proche-Orient ancien à l’Occident mèdièval. Edited by Lucien-Jean Bord, Vincent Debiais and Éric Palazzo. Paris: Geuthner, pp. 283–311. [Google Scholar]

- Dilling, Walter J. 1913–1914. Girdles: Their Origin and Development, Particularly with Regard to their Use as Charms in Medicine, Marriage, and Midwifery. Caledonian Medical Journal 9: 337–57, 403–25. [Google Scholar]

- Drewer, Lois. 1991–1992. Saints and their Families in Byzantine Art. Deltion tes Christianikes Archaeologikes Etaireias 16: 259–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiadis, Stephanos, ed. 2011. Greek Hagiography in Late Antiquity (Fourth–Seventh Centuries). In The Ashgate Research Companion to Byzantine Hagiography. Volume 1: Periods and Places. London: Routledge, pp. 35–94. [Google Scholar]

- Efthymiadis, Stephanos, ed. 2014. The Ashgate Research Companion to Byzantine Hagiography. Volume II: Genres and Context. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Eliason, Lois Munemitsu. 2004. The Virgin’s Sacred Belt and the Fifteenth-Century Artistic Commissions at Santo Stefano, Prato. Ph.D. Dissertation, The State University of New Jersey, Rutgers, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Evangelatou, Maria. 2003. The Purple Thread of the Flesh: The Theological Connotations of a Narrative Iconographic Element in Byzantine Images of the Annunciation. In Icon and Word: The Power of Images in Byzantium. Studies Presented to Robin Cormack. Edited by Antony Eastmond and Liz James. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, pp. 261–79. [Google Scholar]

- Fiddyment, Sarah, Natalie J. Goodison, Elma Brenner, Stefania Signorello, Kierri Price, and Matthew J. Collins. 2021. Girding the Loins? Direct Evidence of the Use of a Medieval English Parchment Birthing Girdle from Biomolecular Analysis. Royal Society Open Science 8: 202055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankfurter, David. 2017. Christianizing Egypt: Syncretism and local worlds in Late Antiquity. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galadza, Daniel. 2018. Liturgy and Byzantinization in Jerusalem. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garitte, Gérard. 1958. Le calendrier palestino-géorgien du Sinaiticus 34 (Xe siècle). Subsidia hagiographica, 30. Brussels: Société des Bollandistes. [Google Scholar]

- Gianandrea, Manuela. 2021. The Fresco with the Three Mothers and the Paintings of the Right Aisle in the Church of Santa Maria Antiqua. In Santa Maria Antiqua: The Sistine Chapel of Early Rome. Edited by Eileen Rubery, Giulia Bordi and John Osborne. London and Turnhout: Harvey Miller Publishers, pp. 335–55. [Google Scholar]

- Graef, Hilda. 1963. Mary: A History of Doctrine and Devotion. London: Sheed and Ward, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Guldan, Ernst. 1966. Eva und Maria. Eine Antithese als Bildmotiv. Graz: Hermann Böhlaus. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy, Cecily. 2008. Images of Children in Byzantium. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Herrin, Judith. 1992. “Femina Byzantina”: The Council in Trullo on Women. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 46: 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrin, Judith. 2000. The Imperial Feminine in Byzantium. Past & Present 169: 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrin, Judith. 2013. Unrivalled Influence: Women and Empire in Byzantium. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hindley, Katherine Storm. 2020. ‘Yf A Woman Travell Wyth Chylde Gyrdes Thys Mesure Abowte Hyr Wombe’: Reconsidering the English Birth Girdle Traditions. In Continuous Page: Scrolls and Scrolling from Papyrus to Hypertext. Edited by Jack Hartnell. London: Courtauld Books Online, pp. 160–74. [Google Scholar]

- Jessop, Leslie. 1999. Pictorial Cycles of Non-Biblical Saints: The Seventh- and Eighth-Century Mural Cycles in Rome and Contexts for Their Use. Papers of the British School at Rome 67: 233–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kälviäinen, Nikolaos. 2018. ‘Not a Few of the Martyr Accounts Have Been Falsified from the Beginning’. Some Preliminary Remarks on the Censorship and Fortunes of the Demonic Episode in the Greek Passion of St. Marina (BHG 1165–1167c). In Translation and Transmission. Collection of Articles. Edited by Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila and Ilkka Lindstedt. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, pp. 107–37. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Holger A. 2004. Eastern Objects and Western Desires: Relics and Reliquaries between Byzantium and the West. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 58: 283–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsis, Kriszta. 2012. Mothers of the Empire: Empresses Zoe and Theodora on a Byzantine Medallion Cycle. Medieval Feminist Forum 48: 5–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laga, Carl, ed. 1992. Eustratii presbyteri Vita Eutychii patriarchae Constantinopolitani. Corpus Christianorum, Series Graeca 25. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, Andrea Olsen. 2019. Female Devotion and Mary’s Motherhood before Iconoclasm. In The Reception of the Virgin in Byzantium. Marian Narratives in Texts and Images. Edited by Thomas Arentzen and Mary B. Cunningham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, Anne E. 2017. Translation and Appropriation: Greek Relics in the Latin West in the Aftermath of the Fourth Crusade. Studies in Church History 53: 88–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Estrange, Elizabeth A. 2003. En/Gendering Representations of Childbirth in Fifteenth-Century Franco-Flemish Devotional Manuscripts. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Leeds, Leeds, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Lidova, Maria. 2013. Sulla più antica immagine mariana nella diocesi di Firenze: Maria Regina nella Basilica di San Marco. In Giorgio La Pira. L’Assunzione di Maria. Edited by Giulio Conticelli, Stefano De Fiores and Maria Lidova. Florence: Edizioni Polistampa, pp. 163–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lidova, Maria. 2016. Empress, Virgin, Ecclesia The Icon of Santa Maria in Trastevere in the Early Byzantine Context. IKON 9: 109–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, Henry. 1990. Garments Pleasing to God: The Significance of Domestic Textile Designs in the Early Byzantine Period. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 44: 215–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniani-Reber, Marielle. 1986. Nouveau regard sur les soieries de l’Annonciation et de la Nativité du Sancta Sanctorum. Bulletin de liaison du Centre international d’études des textiles anciens 63–64: 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Millar, Fergus. 2014. The Image of a Christian Monk in Northern Syria: Symeon Stylites the Younger. In Being Christian in Late Antiquity: A Festschrift for Gillian Clark. Edited by Carol Harrison, Caroline Humfress and Isabella Sandwell. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 278–96. [Google Scholar]

- Mimouni, Simon Claude. 1995. Dormition et Assomption de Marie: Histoire des traditions anciennes. Paris: Beauchesne. [Google Scholar]

- Moorat, Samuel A. J. 1962. Catalogue of Western Manuscripts on Medicine and Science in the Wellcome Historical Medical Library. London: The Wellcome Historical Medical Library, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Faith Pennick. 2018. Dress and Personal Appearance in Late Antiquity: The Clothing of The Middle and Lower Classes. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, Mary. 2013. Alongside St Margaret: The Childbirth Cult of Saints Quiricus and Julitta in Late Medieval English Manuscripts. In Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe 1350–1550: Packaging, Presentation and Consumption. Edited by Emma Cayley and Susan Powell. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. 187–206. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, Mary. 2014. ‘Thys moche more ys oure lady mary longe’: Takamiya MS 56 and the English Birth Girdle Tradition. In Middle English Texts in Transition. Edited by Simon Horobin and Linne Mooney. York: York Medieval Press, pp. 199–219. [Google Scholar]

- Murat, Zuleika. 2016. Medieval English Alabaster Sculptures: Trade and Diffusion in the Italian Peninsula. Hortus Artium Mediaevalium 22: 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najork, Daniel. 2018. The Middle English Translation of the Transitus Mariae Attributed to Joseph of Arimathea: An Edition of Oxford, All Souls College, MS 26. The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 117: 478–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, Virginia. 2004. Mary’s Mother: Saint Anne in Late Medieval Europe. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, John. 2020. Rome in the Eighth Century: A History in Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Panou, Eirini. 2018. The Cult of St Anna in Byzantium. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pitarakis, Brigette. 2016. Female Piety in Context: Understanding Developments in Private Practices. In Images of Mother of God: Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium. Edited by Maria Vassilaki. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, pp. 153–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pitarakis, Brigitte. 2009. The Material Culture of Childhood in Byzantium. In Becoming Byzantine: Children and Childhood in Byzantium. Edited by Arietta Papaconstantiou and Alice-Mary Talbot. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, pp. 167–251. [Google Scholar]

- Rushforth, Gordon McNeil. 1902. The Church of S. Maria Antiqua. Papers of the British School at Rome 1: 1–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador González, José María. 2011. The Death of the Virgin Mary (1295) in the Macedonian church of the Panagia Peribleptos in Ohrid. Iconographic Interpretation from the Perspective of Three Apocryphal Writings. Mirabilia. Revista eletrónica de história antiga e medieval 12: 237–68. [Google Scholar]

- Schrade, Brigitta. 2016. Byzantium and Its Eastern Barbarians: The Cult of Saints in Svanet’i. In Eastern Approaches to Byzantium: Papers from the Thirty-Third Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, University of Warwick, Coventry, March 1999. Edited by Antony Eastmond. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 169–97. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, Stephen J. 2002. Ancient Traditions of the Virgin Mary’s Dormition and Assumption. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, Stephen J. 2008. The Cult of Fashion: The Earliest Life of the Virgin and Constantinople’s Marian Relics. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 62: 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, Stephen J. 2016. The (Pseudo?-) Maximus Life of the Virgin and the Byzantine Marian Tradition. The Journal of Theological Studies 67: 115–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simic, Kosta. 2017. Liturgical Poetry in the Middle Byzantine Period: Hymns Attributed to Germanos I, Patriarch of Constantinople (715–730). Ph.D. Dissertation, Australian Catholic University, Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Skemer, Don C. 2006. Binding Words: Textual Amulets in the Middle Ages. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Kathryn A. 1996. Canonizing the Apocryphal: London, British Library MS Egerton 2781 and Its Visual, Devotional and Social Context. Ph.D. Dissertation, New York University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Talbot, Alice-Mary, ed. 1998. Byzantine Defenders of Images: Eight Saints’ Lives in English Translation. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. [Google Scholar]

- Talbot, Alice-Mary. 2014. Female Patronage in the Palaiologan Era: Icons, Minor Arts and Manuscripts. In Female Founders in Byzantium and Beyond. Edited by Lioba Theis, Margaret Mullett and Michael Grünbart. Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, pp. 259–74. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, Ann, and Henry Maguire. 2007. Dynamic Splendor: The Wall Mosaics in the Cathedral of Eufrasius at Poreč. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- The Vatican Collections. 1982. The Vatican Collections: The Papacy and Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Thelma K. 2012. Silk. In Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 7th–9th Century. Edited by Helen C. Evans and Brandie Ratliff. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 148–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ünser, Şükran. 2022. Ortaçağ Duvar Resimlerinde Aziz İoulitta ve Kerykos Örneklemi Eşliğinde Şifa Teması (The Theme of Healing in Medieval Wall Paintings Accompanied by the Saints Ioulitta and Kerykos Samplings). Ph.D. Thesis, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Wasyliw, Patricia Healy. 2008. Martyrdom, Murder, and Magic: Child Saints and Their Cults in Medieval Europe. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Westberg, David. 2012. A Rose-Bearing Bough of Piety: Literary Perspectives on the Life of Theodore of Sykeon. In Dōron Rodopoikilon: Studies in Honour of Jan Olof Rosenqvist. Edited by Denis Searby, Ewa Balicka-Witakowska and Johan Heldt. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, pp. 227–38. [Google Scholar]

- Woodfin, Warren. 2004. Liturgical Textiles. In Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557). Edited by Helen C. Evans. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 295–323. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ünser, Ş. Tracing Sacred Intercession in Childbirth Across Byzantine Tradition and Its Western Reception, from the Virgin’s Girdle to Saints Julitta and Kerykos. Religions 2025, 16, 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111346

Ünser Ş. Tracing Sacred Intercession in Childbirth Across Byzantine Tradition and Its Western Reception, from the Virgin’s Girdle to Saints Julitta and Kerykos. Religions. 2025; 16(11):1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111346

Chicago/Turabian StyleÜnser, Şükran. 2025. "Tracing Sacred Intercession in Childbirth Across Byzantine Tradition and Its Western Reception, from the Virgin’s Girdle to Saints Julitta and Kerykos" Religions 16, no. 11: 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111346

APA StyleÜnser, Ş. (2025). Tracing Sacred Intercession in Childbirth Across Byzantine Tradition and Its Western Reception, from the Virgin’s Girdle to Saints Julitta and Kerykos. Religions, 16(11), 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111346