1. Introduction

Throughout the long history of human existence on Earth, humans have expressed their desires in various ways in pursuit of safety, stability, and prosperity in life. They have recognized and further developed a transcendent being that can grant their wishes beyond human power. In this context, religion was born and developed naturally, and the religion that emerged due to human needs has been with people throughout human history. It shows how the various religions of the world today breathe and continue along with human history. Buddhism has become an inseparable element of Korean history among many religions, and the human desire to realize Buddhist religious images has been part of that history. In other words, art and visual culture have historically visualized the complex and subtle relationship between humans and Buddhism directly and profoundly. For centuries, works of art have served as essential tools for understanding religion’s changing role and significance in society. In this way, Buddhist artworks have provided a lens through which to view how religious ideas permeate everyday life and influence cultural practices. However, their aspirations are manifested in more diverse forms in today’s complex and varied society than in the past. As Buddhism was transmitted from India to East Asia around the 4th century, China, Japan, and Korea exchanged Buddhist ideas with one another, and each country adopted various forms and represented them visually. This study aims to analyze how this long history has continued to the present day, using specific examples of contemporary Korean visual art to investigate the exchange between Buddhism and art. The rich intersections between Buddhism and contemporary Korean visual culture allow us to explore how Buddhist philosophy and esthetics have influenced and coexisted in contemporary Korean artistic expression.

First, to enhance understanding, this study briefly deals with the historical background of Korean Buddhism and discusses how Buddhism has been established and coexisted with Korean culture, especially visual culture. Using the works of Kwon Jin Kyu (1922–1973) and Chang Ucchin (1917–1990), among modern and contemporary Korean artists, shows how Buddhism’s inspiration on modern art began to be interpreted in a broader sense beyond the simple religious role. After that, this paper provides insight into how Buddhist philosophy has transcended human conflict and promoted harmonious coexistence within Korean visual culture through the concept of integration, which means the integration of knowledge across various fields today. Then, it examines how the importance of Buddhist contemplation and meditation, emphasizing personal reflection and cultivation, has been fused with art, expanded into multiple media and themes, and visualized to acquire new modernity through the works of Suh Seung-Won (1941–) and Cho Inho (1978–). Finally, this study demonstrates that the inspiration and ongoing relevance of Buddhism in contemporary art is an ancient tradition that has inspired and enabled diverse exchanges in the growth of contemporary art beyond Korea and examines how the convergence of art, religion, and science can add to the richness of new, future-oriented visual culture. Paul Hedge proposes, ‘Every religious artifact we never see only one religious tradition exemplified, but instead, we witness part of a global story of interreligious encounters, sharing, and even religion as it only ever is: syncretic, blended, and interreligious’ (

Hedges 2024, p. 126). The works of Nam June Paik (1932–2006) and Michael Joo (1966–) demonstrate how the religious characteristics of Buddhism and artistic elements are combined with scientific elements to provide a new arena of convergence through media fusion. Through this process of reflection, this study aims to demonstrate that the dynamic interaction between traditional Buddhist values and contemporary visual practices creates a rich cultural synthesis that emphasizes the importance of preserving Korea’s artistic heritage and promotes the expanded development of global visual culture today. Namely, the interaction of religion and art is an essential element that allows the ongoing exchange of Buddhism to enrich contemporary visual culture today creatively and serves as a bridge between the past and the present, visualizing cultural identity and further enhancing the communication of people’s thoughts and emotions in the global art world. In this way, Buddhism, which has been passed down from the past, shows how the religion can coexist with today’s culture and offers a venue for dialog and communication that can resonate beyond Korea and around the world, thereby contributing to creating a more harmonious and inclusive society and world.

2. Historical Background of Buddhism in Korea

The Shakyamuni Buddha, who was born in India around the 5th century BC and founded Buddhism, prohibited collusion with political power, but King Ashoka, who appeared around the 3rd century BC, accepted Buddhism as a state ideology and called himself the universal king, showing an example of collusion between the state and Buddhism, and spread Buddhism to Central Asia. In this way, Central Asian Buddhism had a different character from early Indian Buddhism. It was introduced to China around the 1st century BC by merchants and monks who traveled from Central Asia along the Silk Road and gradually spread to China (

J. Kim 2020, p. 261). In China, Buddhism went through the process of Sinicization and formed Chinese Buddhist sects, including the Hwaeom sect and the Chan (Seon) sect (

J. Kim 2020, p. 262). Buddhism, which was first transmitted to Korea through China in the 4th century, accepted Sinicized forms of Buddhism, and soon after, as Buddhism flourished, Korean Buddhism received the characteristics of Indian and Central Asian Buddhism. In this way, while many parts of Korean Buddhism are strongly influenced by Sinicized Chinese Buddhism, Korean Buddhism has developed in its own way. For example, various sects of Korean Buddhism used Chinese names, but the Jogye Order is a sect that originated in Korea. Jinul of Goryeo founded the Jogye Order to continue the lineage of the sixth patriarch of Chinese Chan Buddhism, Master Huineng, and unify the Kyo and Seon sects. Thus, Buddhism, which originated in India, was introduced to Korea around the fourth century, starting with the Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla dynasties, and became Korea’s main philosophy and religion from the mid-fifth century. In particular, Buddhism became an essential means and method for strengthening the royal authority of the Korean nation and promoting unity among the Korean people by being accepted as the country’s guiding ideology. These three dynasties sought to unite their people with Buddhism and the culture created along with it. Especially, Silla developed an elite youth warrior group, Hwarang, with the idea of Maitreya Buddha, representing the future Buddha, with the position that the king is Buddha, and achieved the feat of unifying the period of the Three Kingdoms and the Unified Silla dynasty (

Feuer 2022, p. 134). The Hwarang of the Silla Dynasty was the leader of the Nangdo and was regarded as Maitreya. These armed young men defended their country and played an essential role in unifying the three kingdoms under Silla. After the Unified Silla, Buddhism developed further while being theorized and systematized academically. For example, the Hwajaeng ideology developed by Wonhyo (617–686) is a Buddhist doctrine that seeks to transform all disputes into harmony (

Buswell 2017, p. 132). Another great monk, Uisang (625–702), developed the Hwaeom ideology, which he learned while studying in the Tang Dynasty of China, into an ideology that suited Korea, stating that all things in the universe are not separate but are causes of each other and that they transcend conflict and are fused into one (

McBride 2019, p. 148). He valued theory and practice and sought a harmonious and equal world (

Yi and Jin 2024, p. 197). In addition, among the ordinary people, the Pure Land belief in Korea developed that if they diligently say and believe in ‘Namu Amitabha Buddha,’ they can go to the Pure Land, meet Amitabha Buddha, and be reborn in paradise (

McBride 2020, p. 34). The Gwaneum belief developed that if they diligently believed, people could get rid of bad luck, be cured of illness, and have their wishes come true (

P. Park 2012, p. 154). The leader of the young noble boys of the Silla Dynasty, who regarded the Hwarang as Maitreya in Maitreya Buddhism, protected the country and contributed to the unification of the three kingdoms of Silla (

McBride 1998, p. 110). However, the belief of Amitabha Buddha, the principal Buddha of the Pure Land Sect, contributed to expanding Buddhism to the ordinary people by saying that one can go to paradise after death by simply reciting the Buddhist chant (

Y. Kim 2015, p. 133). Various Buddhist beliefs and the means of maintaining the national system continued until the Goryeo Dynasty. Especially, Zen, Huayan, and Pure Land Buddhism are separate sectarian systems, with Zen Buddhism (Seon Buddhism in Korean) being the mainstream Korean Buddhism. Even during the Joseon Dynasty, when it was founded with Confucianism as its state value, Buddhism was not an official state ethic. However, it was an essential means of mental support for many people and has continued to be one of the major religions in Korea today (

Park and Kim 2024, p. 2).

In this way, Buddhism, intentionally revived at the national level, became an educational tool emphasizing harmony and ethical awareness for the people. At the same time, it naturally combined with the folk beliefs that existed in the lives of Koreans to become a vital religion that fulfills their wishes, hopes, and healing. Numerous Buddhist art pieces have been created along with Korean history, including Seokguram Grotto, Bulguksa Temple, and Goryeo Buddhist paintings, which go beyond the religious visualization of Koreans and provide profound insight into history, culture, art, and society while also helping us understand the lives of Koreans from the past to the present. Contemporary Korean art has not only been influenced by universal religious works such as the Buddha’s reliquary-pagoda, but also has been influenced by specific sects, especially Seon Buddhism and the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism. Namely, Korean artworks that are visualized while being inspired by Buddhist religious works as well as ideologies have made an essential contribution to showing how the traditional religion and ideology can be visualized in a contemporary visual language, and thereby leading today’s people to rethink the religion of Buddhism, as well as informing them of the importance of the past and tradition.

3. An Expanded Visualization of Buddhism in Modern Korean Art

Buddhism, a long-standing religion in Korea, began to change along with the various drastic changes in the country since the twentieth century. As the era of modernization approached, people who had to live under Japanese colonial rule were forced to erase their existence as Koreans under political and social pressure and in a cultural environment where they were exposed to new cultures from various parts of the world, many Koreans tried to regain their lost country, cope with the latest times, and maintain their identity as Koreans. After the 1950s, many Korean artists, such as Kwon Jin Kyu and Chang Ucchin, protected Korean sentiments with their artistic styles, and their fierce lives and passion for art, which valued human dignity and lived lives, were projected into their works. In the case of Kwon Jin Kyu, it is worth noting that rather than simply producing works that fit the iconography of Buddhist works or follow existing traditions, he created new modern sculptural works inspired by primary forms but with his interpretation and expression (

Yeol Choi 2011, p. 90). Kwon Jin Kyu grew up in a Buddhist family and was naturally exposed to the religion, which gave him a deep connection with Buddhism. He was commissioned to work for temples several times and created works inspired by Buddhism. In 1948, Kwon Jin Kyu stayed at Beopjusa Temple for six months, studying the works left behind by his teacher, sculptor Kim Bok-jin (1901–1940), and participated in the creation of the Maitreya Buddha at Beopjusa Temple. Kwon Jin Kyu said, “When the lush summer forest turned into the colorful autumn colors, I felt that I had already become Buddha, under the miraculous spell of the Maitreya Buddha.” (

Yeol Choi 2011, p. 39) His experiences of living in the temple and creating Buddhist statues several times throughout his life later became a catalyst for creating various Buddhist-related works. In particular, his older brother’s early death in 1949 made him directly experience the meaninglessness of the boundary between life and death, and he felt that there was an area in the human world that he could not interfere with, and the temple he visited whenever he felt personal anguish, which was given form in his work,

Entering the Mountain (

Figure 1). This work, which was produced in 1964–65, shows how his abstractly condensed thoughts are shaped through Buddhism. The word ‘entering the mountain (入山)’ is a Chinese character that means to enter the mountains, and in Buddhism, it is interpreted as meaning to become a monk. It is the first gate people pass through when entering a temple. It is lined with pillars and topped with a roof, as the starting point from the secular world to the world of Buddhism. It was inspired by the Iljumun (一柱門), which was created with the meaning of escaping worldly worries and pursuing Buddhist teachings with one mind (一心). Instead of directly representing the gate erected with a single pillar, Kwon Jin Kyu emphasized the horizontal flatness of the left pillar by making the part above the pedestal a single tree, but splitting it into two evenly as it goes up toward the sky. In contrast, the right pillar emphasizes verticality and goes beyond the lintel part toward the sky. The pedestal, divided into three parts and positioned in different shapes and directions, shows how Kwon Jin Kyu’s inspiration from traditional Buddhist styles can be reinterpreted to create new sculptures that bring balance and three-dimensionality to space.

Kwon also produced various works, such as human figures and animals, captivated by the charm of terracotta. This material has endured and been maintained for a long time. For example, his

Self Portrait, produced from 1969 to 1970, is a representative example (

Figure 2). The self-portrait, which depicts him wearing a monk’s robe, a long neck made into a bust, and an expressionless but determined will, has his slender, oval-shaped face slightly lifted and his round eyes directed somewhat upward. Below the small face, a long neck is stretched out and gently flows down to the shoulders, forming an isosceles triangle and creating a bust. Significantly, the large eyes look into the distance, but rather than glaring or tense, they are calm and confident, not arrogant. This work shows a good harmony of Kwon Jin Kyu’s will and diligence for art as an artist. The monk’s red robe, which covers one shoulder, is divided in half, with the other shoulder in dark gray that can be seen below the neck, clearly revealing his artistic simplicity but pursuing the beauty of change and balance. This work, made using the terracotta technique of working with clay and then firing it once, has both the roughness and soft touch of the material. It shows his view of nature and his artistic philosophy, which sought to explore the essence of existence rather than technique while respecting the material’s properties. In addition, starting in the late 1960s, he stayed at temples more frequently than before and created many Buddhist statues. On 7 March 1971, while staying at Tongdosa Temple in Gyeongsangnam-do and creating Buddhist statues, he sent a letter to his nephew saying that Tongdosa Temple was a great place to study and that he was “about to finish making the first Buddha and to begin to produce the second Buddha (

Yeol Choi 2011, p. 90).” The letter shows Kwon’s continued research on Buddhist statues and his devotion to Buddhism. Like this, Kwon Jin Kyu’s work is inspired by the appearance of traditional Buddhist monks, but at the same time, he reinterprets it as the present artist. It nicely captures his ability to reinscribe the past and his attempt at recreating dialog between the past and present.

Another artist, Chang Ucchin, is an artist who, under the Buddhist tradition, has practiced Buddhist visual culture in our daily lives that can be approached by the public and the way we live today. Born into a devout Buddhist family, he met a Buddhist wife, and even without his help, his works are infused with the profound philosophical and religious thoughts and teachings of Buddhism (

Yeob Choi 2023, p. 429). Chang says, “Just because a monk has abandoned the secular world does not mean he has abandoned his life. Rather, just as he has been given another responsibility to live with the Buddha and to carry out his will, art is also a way of life (

Bae 2023, p. 23).” He visualizes nature, people, and our lives simply and warmly, making viewers happy and comfortable. Nevertheless, when people look inside his works, they can feel his countless hidden artistic efforts and passion, which seem to convey the profound truth of life beyond the understanding of art. Among his works,

Zinzinmyo (眞眞妙) is a Buddhist-related painting that Chang Ucchin drew of his wife in 1970, which has the dictionary meaning of really incredible or truly outstanding beauty (

Figure 3). He began the painting after seeing the image of his wife praying and titled the work after his wife’s Buddhist name, Zinzinmyo. For this piece, Chang spent countless hours agonizing over drawing to visualize the image, which led to his health deteriorating. Because of this, his wife worried and later donated the painting to someone else. In the work, a halo surrounds the entire body, and this oval halo is a typical background treatment seen in Buddhist sculptures. However, in Chang Ucchin’s case, the lower part is arranged in a straight line, which seems to represent a wife inside a lotus leaf, which symbolizes the purity of Buddhism. The texture of the oil painting is emphasized through matière treatment, and the figure’s flat, beige, and light brown tones, and the deep contrast of the lotus flower, reflect the balance of the entire screen well. The face is evocative of meditation or prayer, and the head is not a crown but a vertical line, the opposite of the horizontal depiction of the face and eyes, expressing his wife as a bodhisattva. However, the hand gesture, ‘Do Not Fear’ mudra, shows a Buddhist image welcoming believers, reflecting the loving appearance of a wife who always warmly welcomes him while praying. In order to emphasize the true faith and cultivation of the Bodhisattva, the upper part shows U-shaped draperies, but the lower part is drawn in the primary, free-spirited form of the body, like the style of the Buddha’s iconography that was unified in the Gupta period of India, which depicted the body with light robes. In particular, the bare feet and the omission of ornaments are also images of a frugal wife, but Chang’s art, which does not simply depict the image of a traditional Buddhist bodhisattva but modernizes and simplifies it, shows how he reinterprets and develops images from the past. In addition, this work, which uses his wife as its subject, shows us how Buddhism, a religion that is a legacy of the past, still exists in our lives today.

A Buddhist painting,

Palsangdo (八相圖), depicts essential events in the life of Shakyamuni, such as his birth, leaving home, training, enlightenment, and nirvana, in eight panels. Although Buddhism originated in India, it was visualized more diversely in East Asia according to their religious preferences.

Palsangdo began to be produced earnestly in Korea from the early Joseon Dynasty. The eight events seem to be derived from the central tenets of Buddhism, the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. Chang Ucchin’

s Palsangdo: Eight Scenes from the Life of Buddha shows the condensed expression of lines that he has developed and, at the same time, the transitional process of his later transformation into the painting style with black ink (

Figure 4). While traditional paintings are painted on eight screens each, Chang collects eight stories into one on a small screen and handles them in a simple yet innocent, childlike style (

Yeob Choi 2023, pp. 432–33). It also feels like the thick lines are drawn with black ink, not the colors of traditional Buddhist paintings. Even in terms of subject matter, it has its own variation, starting with the process of Maya, the mother of Sakyamuni, giving birth to Buddha in the upper left and progressing clockwise. Next to his mother’s scene is a baby Buddha with his hands raised to the sky, and on the upper right is a scene depicting the grown Buddha becoming a monk. This scene is transformed into a form that seems to show the traditional Korean temple style, such as the main gate, visualizing the Koreanness and popularization of Buddhism. In the middle right, clockwise, there is a Buddha who achieves true enlightenment after practicing and becomes a Buddha. In the lower middle is a Buddha entering nirvana, with the soles of his feet replaced on the pedestal. People are depicted together in a scene trying to receive the Buddha’s relics, and on the lower left is a famous Jataka story from one of the Buddha’s previous lives, where he sacrificed his body by jumping off a cliff to save starving tiger cubs, showing the Buddha’s process of nirvana. After that, a magpie, which symbolizes the people in Korean folk paintings, is placed on top of the Buddha’s cross-legged seated statue, seeming to show how Buddhism has become popular among the people and how it has been teaching them in Korea. Finally, the Buddha statue in the center of the screen is in the mudra, touching the ground. It is also shown in one of the famous Buddha statues in Korea, the Buddha of Seokguram Grotto. The legs are in the lotus position; the right hand is placed on the right knee with the fingertips touching the ground, and the left-hand palm is facing the sky and placed naturally in front of the navel. This mudra depicts Sakyamuni overcoming all obstacles and attaining the path.

Chang Ucchin’s piece resembles the most well-known Buddhist statue to Koreans and, at the same time, depicts the Buddha overcoming hardships and achieving enlightenment. Buddhism, a familiar religion that has been with Korea for a long time and which coexisted closely with his life, was a visualization that is an extension of “the art of living, the art of living, the art of drawing life, discovering life, and further, the art of creating life itself with life as the center,” which Chang Ucchin had been pursuing since the late 1960s (

Shin 2023, p. 564). I believe that Chang pursued to go beyond the description of the Buddha’s process of overcoming hardships and achieving enlightenment and symbolizes his will as an artist and a human being to overcome hardships and perfect his artistic style while also containing the meaning that all people in the world should overcome the difficulties and temptations they face and obtain the authentic truth and enlightenment so that they can live together in harmony and peace in the world. In this way, his seemingly simple visual representation combines artistic techniques and styles between Western and Eastern, past and present, to create a familiar yet profound resonance for the public and show how Buddhism, a religion of the past, can contribute to the right living and thinking of today’s society and people.

4. Modern Manifestation of Buddhist Reflection and Cultivation

In the early 1960s, Suh Seung-Won formed a group called ‘Origin’ to break away from old customs and introduce young Koreans’ new ideas and thoughts to the world. Based on Korean tradition and his life experiences while growing up, he began his geometric abstract works centered on paintings and prints, and tried to build a new theoretical art form by combining his own geometric elements to convey the artist’s attention to convey to the world. After that, his artworks gradually deconstruct these former concepts and styles in reverse until offering a space for various interpretations. As a result, his visual representation provides a diffused space where people can experience and feel together through the expansion of the art medium. The elements of reflection and meditation on life that are increasingly emphasized in his later works go beyond regional Koreanness and lead to the religious meaning of Buddhism, which is to realize the truth and attain liberation through meditation. Suh Seung-Won confesses, “I think that my mind, which seeks true enlightenment by practicing and reflecting, turning myself in, not being tainted by the secular world, and trying to liberate and purify my mind, is a Buddhist believer and Buddhism itself, and I think that it is my work (

M. Kim 2024c).” In addition, Suh’s belief, “Meditation, reflection, and contemplative elements are connected to Buddhism,” is completely buried in his works (

M. Kim 2024c). His paintings calm the viewers’ minds, allow them to focus while looking at them, and enable them to reflect on their lives and contemplate deeply about the world. The extensibility of his works creates a more universal visual language, enabling international communication that transcends national borders.

Suh Seung-Won’s early works were inspired by traditional Korean culture, such as white porcelain, a Korean traditional house (Hanok) window paper, and geometric patterned door frames, and established the theme of simultaneity, which included a modern sense of design esthetics in a society that was rapidly industrializing at the time (

Yoon 2016, p. 2). Since 1963, he has taken simultaneity as a proposition and has sought to show what can be simultaneously expressed through him in the world of peace by making the invisible visible (

Chun 2010, p. 106). It allowed him to develop his artworks that utilized geometric forms earnestly, using the proposition of ‘simultaneity.’ For example, his

Simultaneity 69-H is a work with a black square tilted diagonally at the top of the screen (

Figure 5). This work was used as the cover of the first magazine published by AG (The Korean Avant-Garde Association), an art group formed in 1969 to pursue experimental and modernized new art (

M. Kim 2024a, pp. 42–44). When used as the magazine cover, a red line was attached to the front side of the black square to emphasize its three-dimensionality. At the same time, the red letters ‘AG’ at the bottom and the black letters in the rest of the area were in harmony with the overall screen, emphasizing the characteristics of AG, an art group that attempted simple but new forms. In the original

Simultaneity 69-H, the slanted rhombus shape at the top is composed of a geometric form in which the back is smaller than the front, giving a sense of space while being flat. In addition, thin black lines run vertically down the screen below the two front sides. Among them, the line closest to the viewer below the screen is drawn at the same angle as the side of the black square above, leading the viewer to imagine a space where the flat square does not look like a hexahedron. However, at the same time, all the lines are composed so that some are visible or invisible, showing how much Suh Seung-Won himself values formative order and harmony while also making the two-dimensional picture screen look three-dimensional and further providing the viewer with an opportunity to create an imaginary world within the screen in multiple dimensions. Suh Seung-Won says, “Simultaneity means making the invisible visible, allowing what happens in the world of nirvana to be expressed through me simultaneously, and it is the pursuit of identical and equal time and space. My work explores strict formative order and the space of harmony, and I try to capture physical time simultaneously with action and mindfulness” (

Suh 2011, pp. 80–81). Thus, the mindfulness Suh means Korean uniqueness and modernity that can be recognized as globalized, while at the same time emphasizing a universal world of thought that goes beyond abstraction and breaks down the boundaries obtained from simplified and organized informativeness.

The profound reflections embedded in the work are also strongly connected to Buddhist thought and have been further developed in Suh Seung-Won’s recent works. His continuous reflections on the theme of ‘simultaneity’ have continued for over fifty years under the name of simultaneity, a name for purely expressing lines, colors, and planes as geometric abstractions. In the formativeness of the form, as seen in works such as

Simultaneity 22-707, the reflections on colors and sensibility have developed in the direction of pursuing freedom (

Figure 6). Suh Seung-Won’s past simultaneity had a strong cold feel of squares and corners, but his works since the 2000s have eliminated corners and have used gentle colors, pursuing works that express soft light like the evening glow (

Yoo 2009, p. 4). This work is an expanded version of his belief that the most important thing in art is to be new in an experimental spirit. It is the result of his long-standing research in pursuing art that has filtered the physical properties of color and paint.

Simultaneity 22-707 is a work in which pastel tones of pink, sky, and yellow coexist, with spaces where the forms become blurred (

Sim 2021,15). Through this continuous filtering process,

Simultaneity 22-707 is a space set in pastel tones of pink, sky, and yellow where the forms become blurred. These coexistences are warm, peaceful, and cozy colors that naturally overlap and mix with each other, creating a three-dimensional or multi-dimensional deep and invisible endless space within the screen rather than a two-dimensional one, creating a space for contemplation and meditation where the viewer can think in various ways. Suh Seung-Won’s reflections on his life, saying, “Before this body was born, what was this body, and after I was born into this world, who am I?” led people to reflect on their own lives (

M. Kim 2024c). Suh also explains his new painting style in

Simultaneity 22-707, saying, “I see myself immersed in a meditative world while reflecting on my life, and now, facing death, I paint while looking at myself without any noise” (

Tetto 2024). When reflecting on one’s life, the elements of the meditative world are connected to the idea that one can attain liberation and enlightenment by overcoming dualistic thinking in Buddhism and observing the oneness (一義) that goes beyond opposition and discrimination based on the idea of equal non-duality. In particular, the emptiness (空) that appears in the Buddhist scripture, the Heart Sutra, form is empty, but empty is form (色卽是空空卽是色) means that something seems to exist but in reality, does not exist, emphasizing the importance of realizing that everything in the universe is empty (

Strong 2015, p. 258). His current project displays an esthetic of contemplation and meditation with an esthetic and contemplative aftertaste influenced by his sense of restraint, self-recovery, and freedom. His combination of art and Buddhist elements provides a more universal space for contemplation and meditation (

Yoon 2016, p. 7). Thus, Suh’s art visualizes contemplation and meditation, which are widely practiced in Buddhism as a form of practice through the medium of art. It offers a place for people today to have a greater sense of peace of mind beyond religious meaning, inducing contemplation on natural life and the world and allowing today’s people to contemplate how they should embrace one another and create a harmonious society.

Cho Inho produces traditional Korean landscape paintings that contain Korea’s nature and philosophy. He says, “Buddhism has greatly influenced me because my parents are Buddhists, and a significant portion of my art is based on Buddhism. As an example, I had an exhibition called ‘Gyeonseong’ that visualized liberation in Buddhism while attempting to concretize the Buddhist teaching, ‘if you meet me and know me, you will know the world and become free,’ with the visitors (

M. Kim 2024b).” Majoring in art, he found his own artistic style when visiting Jeju Island in the middle of winter in 2006. The harsh wind and cold he experienced there made him reflect on his life, and through this, Cho began to visit Korea’s nature in person and visualize it in his paintings. Among the long history of Korean landscape paintings, true-view landscape paintings, which aimed to paint Korea’s actual nature as a background, were fully developed by Jeong Seon (1676–1759) in the 18th century. True-view landscape painting emphasized Koreanness while expressing the zeitgeist of the late Joseon Dynasty that sought to change politically and socially. Cho Inho, strongly inspired by true-view landscape painting, created works depicting today’s Korean land while incorporating people’s thoughts, philosophy, and trivialities of everyday life, thereby pioneering a new modernized genre of traditional Korean landscape painting.

What he first valued was the encounter and connection between people and nature. Just as in Buddhism, a person’s past and present lives are linked, and all of them come together to determine the next life, or people are connected with profound relationships; he established the space of Korean nature as a place where people with connections meet each other, and at the same time, a place where humans meet and reflect on themselves, and he began to produce landscape paintings that could meet and connect with people by putting these ideas into works. For example, in order to draw a mountain that people visit, he walked around the mountain himself and gathered sketches to create a single work, which is the same method as traditional landscape painting, but to understand the subject of the hill, Cho Inho began to draw his

Warped Landscape series in which all parts are visualized from multiple angles, rather than the easily recognizable shape of the mountain, by stitching and gathering parts of the hill depicted from various moving points (

Figure 7). In particular, the spatial composition that gives a sense of three-dimensionality by overlapping parts depicted from multiple angles and heights is expressed in black ink, which enhances sufficient liveliness. In addition, through the coexistence of ink lines that contain the roughness and softness seen in traditional ink paintings and detailed or abstract object descriptions, people know the picture depicted as a complex natural appearance that is different from the actual landscape at first glance and through profound observation, they feel as if they are in that place, contemplate human existence through nature, and think that each person living in the world should live with a precious heart just as a single blade of grass, which is considered insignificant, is essential. It establishes a modernized, participatory landscape painting that induces active participation. In this way, his art expresses affection for a world where we respect insignificant things and people live harmoniously. It represents the Buddhist idea of cause and effect, which states that everything is connected beyond nature and people and people to people.

Traditional East Asian and Korean landscape paintings frequently describe nature, are mostly painted on paper or silk, and are made into hanging scrolls or handscrolls. Cho Inho, who pursued the modernization of landscape painting, attempted to make landscape painting three-dimensional. For example, his work,

Enlightenment [Gyeonseong (見性

)]–Gujeongbong, is arranged as a hanging painting that naturally moves in the air, allowing the audience to freely move around the work and become one with it (

Figure 8). The screen is wrapped in eleven pieces of silk cloth and arranged to flow naturally from the wall, creating another space within the exhibition hall and providing an entrance space for visitors. Young-Taek Park explains, “Cho draws each world with a brush on a piece of cloth and captures it in ink. The mountains, which are living things, writhe with a strange power, and the painting is spread out in a circular space, heightening the feeling as if the entire mountain is being viewed in order” (

Y.-T. Park 2011, p. 1). In particular, the nearby nature was depicted with rough and spontaneous brushstrokes, giving it a sense of liveliness swaying in the wind. At the same time, the distant landscape was painted with dense and compact brushstrokes, utilizing various techniques and styles. When the viewers go inside the installation space, they see a stone filled with water in the shape of a well placed to express the scene where Cho Inho observed himself reflected in one of nine stagnant water halls on the peak of Gujeongbong in Wolchulsan (or Mt. Wolchul), Korea. Cho states, “I installed this piece with the theme of meeting nature and myself while hiking by directing a scene of meeting myself by looking at my reflection in a well at the peak of Gujeongbong (

M. Kim 2024b).” The piece’s title, Gyeonseong (見性), comes from Seon Buddhism (also known as Zen or Chan Buddhism) and says that one can achieve enlightenment and become a Buddha by facing one’s mind and seeing one’s original nature. The term ‘Gyeonseong’ was interpreted by the artist as enlightenment. Enlightenment means that the Buddha realized the truth about the cycle of life and death, became liberated entirely from that cycle, and revealed the spiritual path he had rediscovered (

Cantwell 2010, pp. 24–26). The work allows the audience to experience Cho’s wish, “if one naturally meets oneself and knows oneself, one will also know the world and be free, if not liberated (

M. Kim 2024b).” In order to reflect on himself, Cho Inho, who has become more solid and built a full-fledged art world, shows through his works how diverse an object can be beyond a simple depiction of the nature of Korea. In such a way, in nature, which is described in detail or broadly, we can see how many relationships and connections a human has without realizing it and how they live as one of nature. Contemporary Korean artists such as Suh Seung-Won and Cho Inho, who are profoundly inspired by Korean tradition and nature, show how today’s visual culture can be connected to the field of religion and integrated in a broader way to create a synergistic effect.

5. A Place of Art Beyond Time and Space by Integration and Consilience

This section is not intended to discuss the influence of American culture on Korean culture, nor to discuss Americanized forms of Buddhism. Instead, it aims to provide concrete examples of how Buddhism as a religion can be interpreted comprehensively and multidimensionally for Korean American artists, through the works of Nam June Paik and Michael Joo. For example, Nam June Paik was influenced by Buddhism in Korea before coming to the United States. Michael Joo was influenced by his Korean parents, who believed in Buddhism, and thus did not accept Americanized Buddhism. Furthermore, this study focuses on how the two artists tried to show how Buddhism was an important medium to inform their artistic beliefs, convey the importance of traditional religion and philosophy, and connect the world. Nowadays, due to the diversification and universalization of media, people can simultaneously share what they think, like, and feel about their lives. The United States was one of the places where many people inevitably encountered these trends. Like numerous immigrants, two Korean American artists, Nam June Paik and Michael Joo, address the values of multicultural exchange, academic consilience between various disciplines, and communication with people and the world in a wide range of regions worldwide. Koreans who immigrated and settled in the United States were exposed to diverse cultural situations and witnessed a relatively new interest in Buddhism, especially Seon/Zen Buddhism, which had spread in the United States since the 1950s and 1960s. After Japanese immigrants began to build the first American Zen temples in 1913 in Hawaii and more Zen temples were erected in 1922 in the mainland United States, the ‘Zen Boom’ appeared during the 1950s and 1960s (

Williams and Queen 2013, p. 20). Its environment may perhaps have provided an opportunity for Korean American artists to combine Buddhism and art. Their specification between art and religion to cultural exchanges through various modulations, reinterpretations, transformations, and creations represents how art and religion combine other genres, such as science, music, and technology.

Nam June Paik, known as the founder of video art, worked during a time when various cutting-edge machines, including color televisions, were readily available at the time. After moving to the United States, he produced a work,

Robot Opera (1964), featuring a human-sized robot that moves, talks, and defecates using remote devices. Paik also used the first consumer portable video camcorder, the Sony Portpak, released in 1965, which was first used to pioneer the early media in the video camera field. While mainly introducing artworks created purely by technical means, as seen on video and television, Paik created new forms of abstraction in

Magnet TV (1965) and

TV Crown (1965), illustrating pattern images by manipulating the television’s internal circuitry. These pieces exemplify how art can be integrated with technology and science. Beyond continuing the fusion of technology and science in art, his installation art deals with the concept of Buddhism. An art group called Fluxus, which he joined in Europe in the early 1960s in Europe, heavily covered this religion. Gradually, Paik expanded his artistic boundaries while combining Seon Buddhism. In addition, TV, a technological and popular cultural item, was used to demonstrate how much the medium can inspire people to think, meditate, and empathize. A Korean-born, Nam June Paik grew up in a Buddhist family and was able to expand his knowledge and experience of Buddhism when he studied abroad in Japan. After arriving in the United States in 1964, he visualized the consilience of religion and science using technological media, including TV. His

TV Buddha was made from an 18th-century wooden Buddhist sculpture and a television that he purchased at an antique market in New York with an inheritance from his family living in Japan in the United States. Sitting cross-legged and meditating, Buddha is seated in front of a monitor that broadcasts his image. A camera installed in front of the Buddha records the Buddha, and the recording is broadcast on a monitor screen in real time. A Buddhist statue created in the past is recorded and shown in its present form, capturing a moment of coexistence between the past and the present. In addition, the technological medium TV shows the front view of the Buddha to visitors looking at the back of the Buddha while appreciating this work, allowing people to enjoy the three-dimensional sculpture fully. In this way, Nam June Paik’s media art provides a space where the audience can feel materiality and religiosity simultaneously by combining TV, made of metal and plastic, which emphasizes physicality, and Buddhist sculpture, which promotes meditation. Meditation is a significant part of Buddhist practices. According to Ronald Green, Seon Buddhism gets its name from the Sanskrit word dhyāna, which means ‘meditation,’ and modern Korean Buddhism focuses on doctrinal and meditative wisdom, respectively (

Green 2014, p. 57). Since 1974, Paik’s

TV Buddha has been continuously produced in various versions with Buddha statues from multiple regions. It conveys the teaching and message of Buddhism that anyone can become a Buddha through practice and the use of different Buddha statues.

In addition, Paik has introduced works that express his view that combining science/technology and art is inevitable and how to deal with this inevitability specifically. For example,

Good Morning, Mr. Orwell was inspired by George Orwell’s novel, ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four,’ published in 1949, which tells the story of a human being whose freedom of expression is suppressed due to the advancement of science. However, in his work,

Good Morning, Mr. Orwell, Nam June Paik conveys a positive message that although the development of technology and communication can be a means of surveillance, it can also sometimes be a means for people worldwide to communicate. These embracing gestures of objects and living creatures seem to be inspired by compassion in Buddhism. Compassion (

Karuṇā) is one of the two virtues in Buddhist doctrine that is defined as ‘the wish that others be free of suffering, in contradistinction to love/benevolence (

Maitrī), which is the wish that others be happy. Compassion is a quality that a Buddha is believed to possess to the greatest possible degree and that Buddhists still on the path strive to cultivate (

Jackson 2004, p. 419).’ Nam June Paik visualizes in his video piece the message that overcoming jealousy and anger among people and society is essential, as well as breaking free from selfish greed and having a broad and compassionate heart. This video,

Good Morning, Mr. Orwell, simultaneously screened to various parts of the world via satellite for 38 min, allowing many people to view it in real-time, making art no longer a medium for the few but a medium for the many. As it merged with science, Paik’s art further enriches the world and shows that it can contribute to communication.

Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii is a work that visualizes his idea that electronic highways will connect the whole world. It shows how the world can be quickly connected through media and communication through a map of the United States. In particular, 50 DVDs are located inside 336 television sets that project total images within 575 feet of multicolored neon tubing shaped like each state. The projected images were created using motifs and colors that symbolize each state’s identity, characteristics, and culture in the United States, as seen on the map. These images are connected like blood vessels with 3750 feet of cable, which seems to symbolize cause and effect’ and ‘karma’ in Buddhism, as if the TVs are connected as if they are one person (

Burton 2017, p. 34). During the 1990s, when the Internet was not widespread worldwide, we can see his foresight that predicted an era in which people would live connected. Nam June Paik’s thoughts are already well expressed in his writings written in 1974, where he sought to connect the past, present, and future and visualize the expanded role of media for the present and future world through works of art. In his 1974 report, Paik argued that the forthcoming information superhighway would become widespread in American society and even worldwide, addressing urgent social problems such as racism, economic inequality, and environmental pollution while claiming the necessity of preparation for the future network (

Paik [1974] 2019a, pp. 154–65). That is why Paik’s artworks contain the messages to find ways to humanize rapidly evolving technology and electronic media rather than avoid them. He says, “The real issue implied in ‘Art and Technology’ is not to make another scientific toy but to humanize the technology and the electronic medium” (

Paik [1969] 2019b, p. 33). The primary Paik’s belief is that the newly emerging cutting-edge society will create an invisible but inconceivable and close connection between human life and the world. If people cannot disregard the future situation, he attempted to visualize a better solution through his work: That is, the coexistence of technology and humans. At the same time, the Buddhist idea of causality is deeply rooted in his art, which visualizes how people and the world are interconnected. The Buddhist concept of karma is that our past and present appearances can determine our future, and the belief that this has created is one of the essential elements. Like this, Nam June Paik’s visual representation goes beyond the integration relationship in which science and art can collaborate to create a work of art. It shows how the genre of art can be connected to people’s lives and society, and how this role can be infinitely expanded through collaboration with other fields today. Thus, Nam June Paik was one of the pioneering artists who studied science and technology and converted them into tools that could enrich human life and imagination and provide humane alternatives.

Michael Joo, born to Korean parents who settled in the United States to study science, was influenced by his parents; he majored in science in college before changing his major to art. His interest in academic and natural phenomena expanded into various academic fields, such as civilization, nature, history, and religion, and was reflected in his works. His art initially began with a consideration of people’s cultural identity and gradually diversified into intersections between science and art, nature and humans, and past and future times. He uses scientific thought processes and physical experiment results to produce his works, making fluid and persuasive representations more tangibly and existentially. His pieces break away from the framework of typical ideas and customs about existing objects and people, leading viewers to question the nature of identity and the environment and visualize how consilience between disciplines is possible through art.

Since the 1990s, Michael Joo has been asking people questions through influential works that expose the meaninglessness of dichotomous perception between the East and the West and promote change in people’s prejudices. While visiting the transpacific regions, he primarily collects various materials and creates them into artworks with multilayered meanings and messages. His works also show the infinitely expanded scope and role of the field of art today through the consilience of various scientific fields such as chemistry, geography, ecology, and the humanities, including philosophy, religion, and anthropology. For example, Michael Joo’s

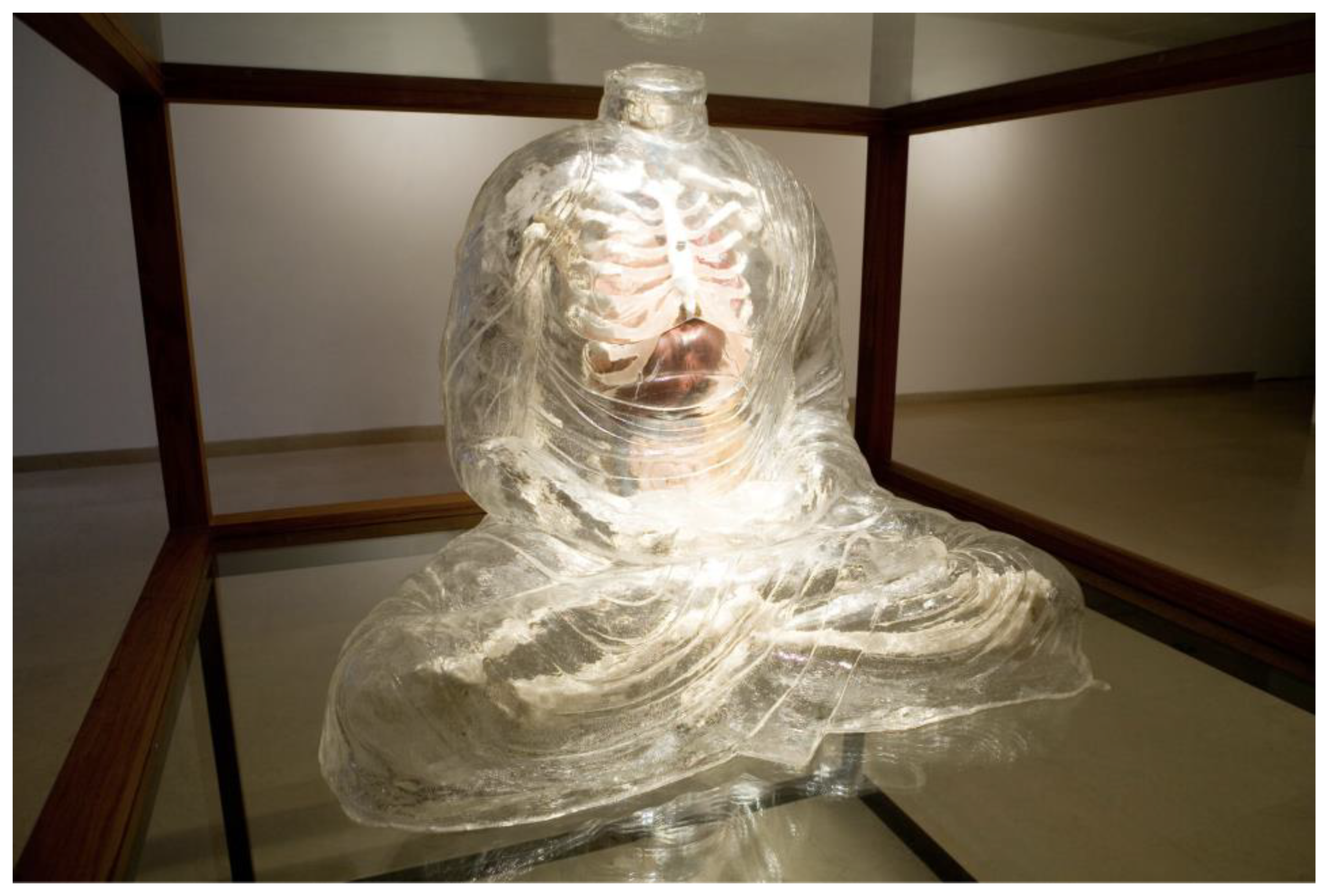

Visible is a headless urethane cast piece depicting a Buddha meditating in a lotus position (

Figure 9). The exposed body has a dissected shape with all bones and internal organs visible under transparent skin that combines Buddhism, one of the representative Asian religions that originated in India, and anatomy, a field of science that values accuracy and reality. Hyunsun Tae notes that ‘the viewers’ gaze can freely move in and out of an engagement with Buddha, which turns the visible and invisible boundaries into two-way flows (

Tae 2007, p. 39). The two-way flow overlaps the sacred Buddha’s existence and the physical human body. The traditional religious Buddha’s body has been created to be constantly viewed with reverence, but Joo’s Buddha allows visitors to take a close look at the Buddha’s invisible inside of body. The Buddha’s body is also trapped in a metal frame, pointing out humans’ narrow vision and perspective. It suggests how we need to break away from the typical frame of human assumption. The Buddha’s face, which conveys many religious meanings and symbols, is intentionally omitted, and the transparent shape of the body is emphasized, disturbing the viewer’s straightforward interpretation. Michael Joo’s interest in Buddhism began during childhood in an environment where Christianity and traditional Korean Buddhist practices coexisted with his household—Christian mother and Buddhist father. In addition, growing up with his parents, who were scientists, he was also a science student who went to college to major in biology before majoring in art, which allowed him to naturally incorporate science into his art. Young Paik Chun’s evaluation highlights Joo’s artistic ambition to merge cultural discourse with scientific rationality and cultivate a sense of creative originality that transcends conventional boundaries by incorporating reality, authenticity, and veracity themes into his artworks (

Chun 2009, p. 301). The absence of a face can obliterate individuality, but the meditating posture of the body still brings up the image of Buddha. The visual fluidity, displaying the body without a face, that Michael Joo intentionally provided with places of reversal conveys the profound possibility and Buddhist teaching for any living being to become a good teacher, Buddha, if they attain enlightenment. Moreover, the Buddha’s hand gesture, called mudra, in Joo’s statue, illustrates the meditation mudra that helped Buddha obtain enlightenment. The thumbs of both sides are placed together, and the back of the hand is naturally placed on the foot in the lotus position. Ronald Jones says, “Joo has metaphorically uncovered the corporeality of the man called Buddha from beneath the cultural mock-up that has subsumed Buddha’s original identity over the centuries, and this is where his irony sings. He has made his individuality transparent in order to sacrifice it to a universalizing form of cultural artifact (

Jones 1999).” Joo’s

Visible illustrates that anyone or anything can become a Buddha, and his art goes beyond simply dealing with race and dichotomous East–West concepts. Michael Joo confesses, “I think people are exaggerating my identity, but I am more concerned about racial ambivalence than that. I explore complex issues of ambivalence, such as the relationship between nature and civilization, my inner self, and the outside world (

Lee 2006).” The same year, Michael Joo presented an expanded version of

Visible in Headless. This work combines the Buddhist sculptures seen in the former piece,

Visible, with the faces of various characters and dolls to create a fusion of diverse forms.

After that, Joo expanded his art world with works such as

Bodhi Obfuscatus, combining Buddhism and science. His

Bodhi Obfuscatus was first introduced in 2005 using Gandhara Buddhist statues and cameras. He was granted permission to work with the Rockefeller Collection of the Asia Society, allowing him to see many collections. In the process, Michael Joo saw many of the collections that were not on display and ‘thought that one way to instinctively get closer to them as objects was to have insects crawl all over the face of the sculptures (

Gluibizzi 2020)

.’ In the process, he changed perspective as he questioned ‘what and how insects see,’ the solution was to point the eyes at the face like cameras. He imagined that the cameras surrounding the Buddha’s face were like a space helmet to him, and he hoped that the artificial elements he installed would create a ‘theatrical work in which the entire image is absorbed at once as the eyes adapt to the light (

Gluibizzi 2020)

.’ It goes beyond the process of observing existing parts, and through careful observation or training of each part, which reminds us of the Buddhist process of sudden enlightenment. The 2006 Gwangju Biennale, held in Korea, was reproduced as a Pensive Bodhisattva statue from Daewonsa Temple in Boseong, Korea. Instead of sitting cross-legged with both legs crossed during Buddhist practice, the Pensive Bodhisattva statue has the left leg on a lotus-patterned pedestal and the right leg crossed so that the soles of the feet are visible, combining the postures of meditation. The Pensive Bodhisattva was actively produced as another form of the Maitreya Bodhisattva statue along with the development of the Maitreya belief that represented the future Buddha, which was popular during the Three Kingdoms period of Korea. As it is the form of the future Buddha, Maitreya’s installed cameras capture various forms and angles, such as a face with an old look, a slight smile, a chin gently resting on a finger, meditating, and looking at sentient beings. In particular, the depiction of the less musculature upper body shows the style of the Gupta period in the 5th century, when the Buddhist style was unified in India. On the other hand, the drapery and robe lines decorated on the lower half are inspired by the famous Chinese style at the time and have a restrained and developed appearance in the Korean style. Moreover, installed cameras in a circular shape around the statue, especially around the head and shoulders, provide various perspectives to the viewers and encourage them to appreciate the Buddha statue as seen with their eyes and the images of parts of the Buddha statue captured according to the angle of each camera. Simultaneously, the live surveillance of cameras surrounding the Buddha statue in a circular shape is shaped like a halo, maximizing the synergy created by combining religious art from the past with current science and technology. This work visualizes an example of possible collaboration in Korea, time, and geography by combining cameras representing Buddhism, a religion with a long history, and modern science and technology to create a new type of art.