Ritual Kitchens and Communal Feasting: Excavating the Southeastern Sector of the Ataruz Temple Courtyard, Jordan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Temple Kitchen

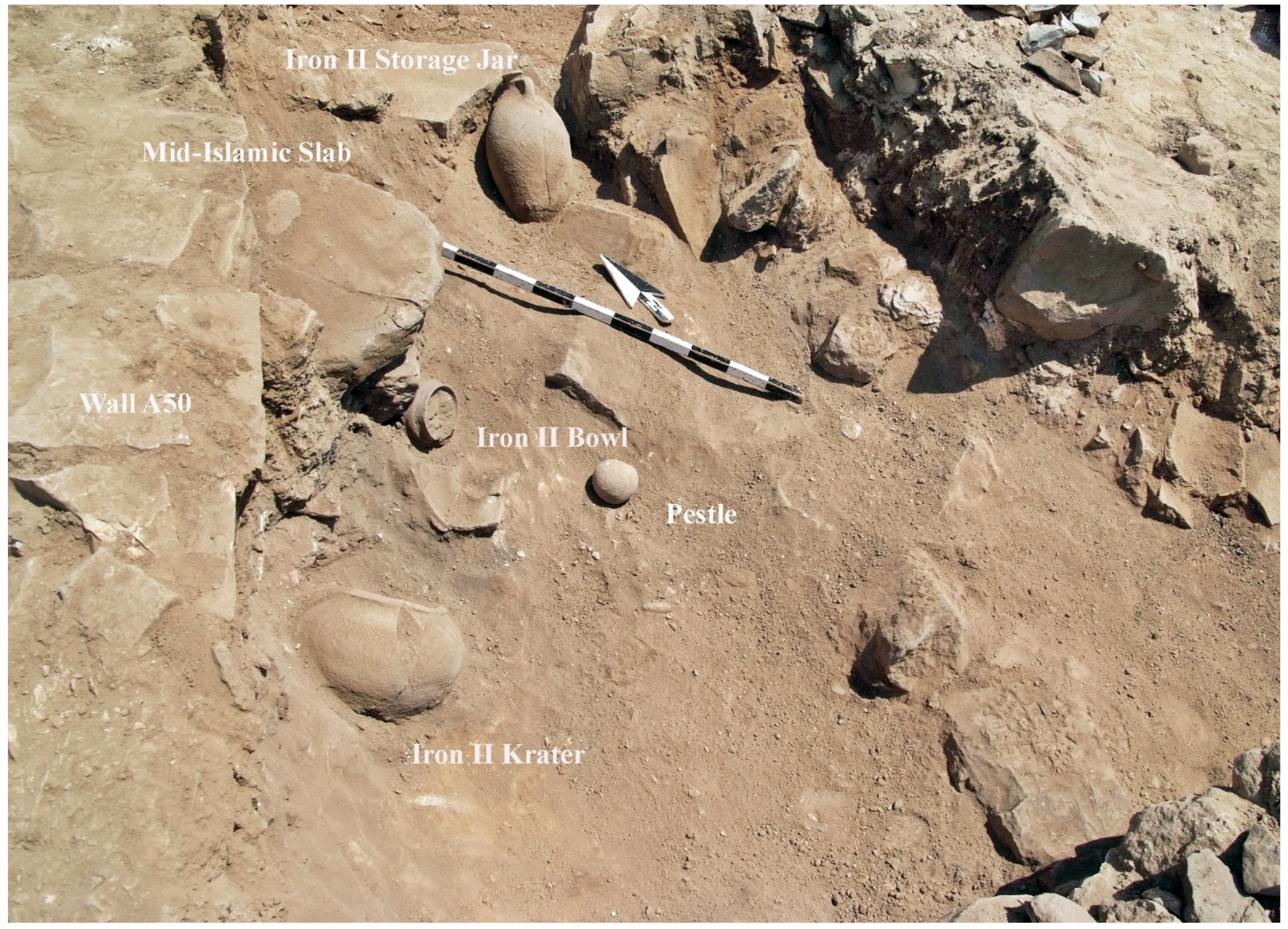

2.1. Room A16

2.2. Function of Room A16

2.3. Room A17

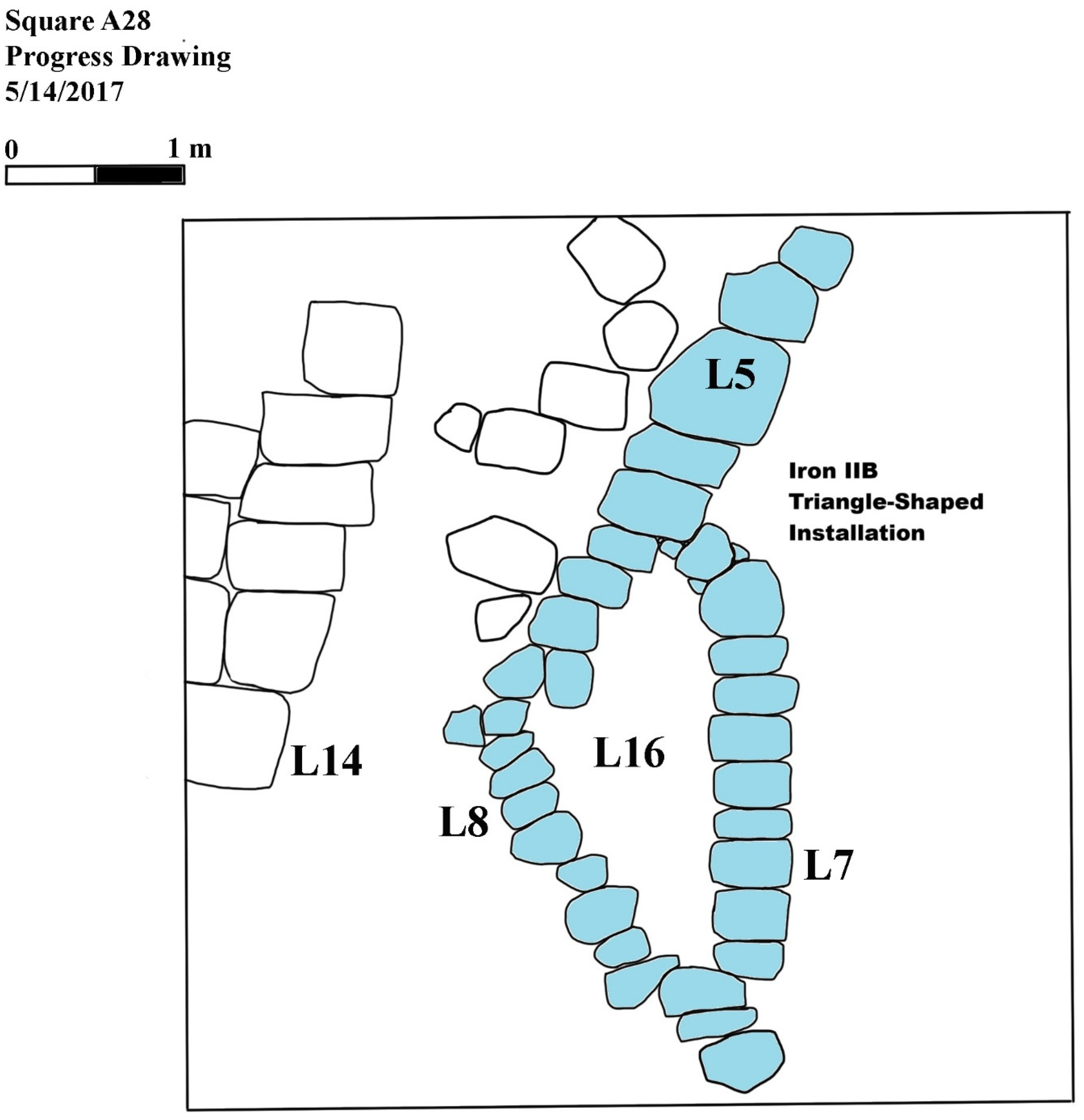

3. Libation/Animal Slaughter Area

3.1. Bedrock Outcrop

3.2. Courtyard Alley

4. Temple Dining Area

4.1. Squares E6 and E7

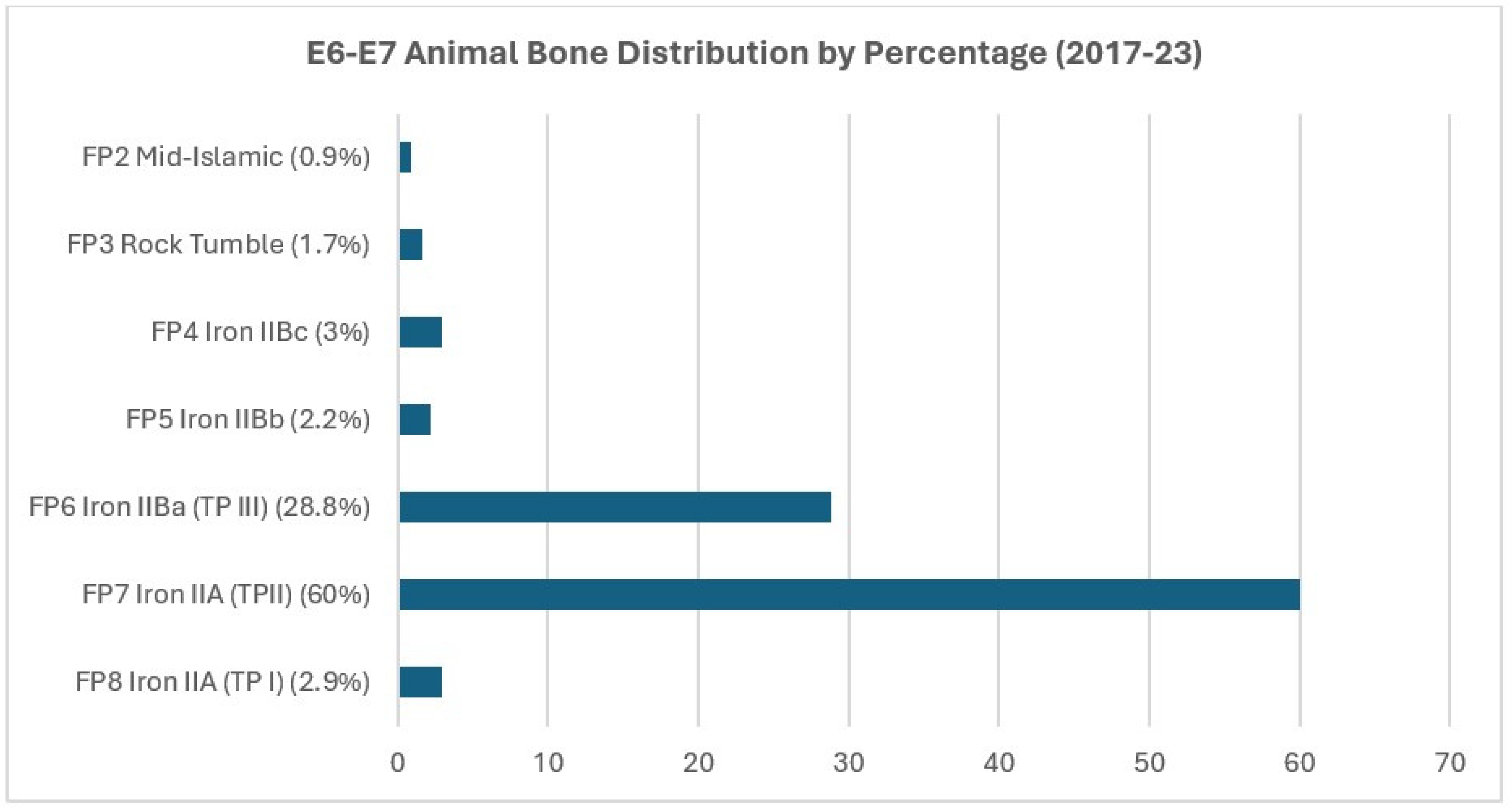

4.2. Animal Bones

5. Discussion

5.1. Temple Kitchen

5.2. Blood Libation Rock

5.3. Implications of Faunal Data

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Throughout this paper, locus numbers are cited as Square:Locus—square designation, a colon, the letter “L,” and the locus number (e.g., A29:L1). Room (R), Wall (W), and Installation (I) numbers are assigned and used in place of locus numbers only after the feature is fully excavated, its context is clearly defined, and its significance within the site is established. |

| 2 | Additionally, the sacrificial animal’s blood could be shed across the bedrock surface rather than all poured into the cup-hole, allowing it to flow directly into the central channels. Temple workers may also have poured blood by hand—using cultic vessels—directly onto the bedrock’s central section. |

References

- Albertz, Raineer, and Rudiger Schmitt. 2012. Family and Household Religion in Ancient Israel and the Levant. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, Adam L., Christopher A. Rollston, P. Kyle McCarter, and Stefan J. Wimmer. 2018. An Inscribed Altar from the Khirbat Ataruz Moabite Sanctuary. Levant 50: 211–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beit-Arieh, Itzhaq. 1995. Harvat Qitmit: An Edomite Shrine in the Biblical Negev. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ami, Doron. 2006. Early Iron Age Cult Places—New Evidence from Tel Hazor. Tel Aviv 33: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Tor, Amnon. 2016. Hazor: Canaanite Metropolis, Israelite City. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Biran, Avraham. 1994. Biblical Dan. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke, Stephen J. 2004. Cult and Archaeology at Pella in Jordan: Excavating the Bronze and Iron Age Temple Precinct (1994–2001). Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales 137: 1–31. Available online: https://www.royalsoc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/137_Bourke.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Bourke, Stephen J. 2013. Pre-Classical Pella in Jordan: A Conspectus of Recent Work. ACOR Newsletter 25: 1–4. Available online: https://publications.acorjordan.org/wp-content/uploads/acor-newsletter-vol-25-1.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Daviau, P. M. Michele. 2017. A Wayside Shrine in Northern Moab: Excavations in Wadi ath-Thamad. Oxford: Oxbow. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Andrew R. 2013. Tel Dan in Its Northern Cultic Context. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. [Google Scholar]

- Dever, William G. 2014. The Middle Bronze Age ‘High Place’ at Gezer. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 371: 17–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dever, William G. 2019. Archaeology and Folk or Family Religion in Ancient Israel. Religions 10: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, Avraham. 2012. The Archaeology of Israelite Society in Iron Age II. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, Israel., David Ussishkin, and Baruch Halpern, eds. 2000. Megiddo III: The 1992–1996 Seasons. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, vols. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, Pedar W. 1994. Kitchens and Dining Rooms at Pompeii: The Spatial and Social Relationship of Cooking to Eating in the Roman Household. Ph.D. thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, Yosef, Saar Ganor, and Michael G. Hasel. 2014. Khirbet Qeiyafa Vol. 2: Excavation Report 2009–2013. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, Yosef, Saar Ganor, and Michael G. Hasel. 2018. Khirbet Qeiyafa Vol. 4: Excavation Report 2007–2013: Art, Cult, and Epigraphy. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, Jonathan S. 2013. Dinner at Dan: Biblical Interpretation and the Archaeology of Cultic Feasting. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, James W. 2010. Chapter 3: Household Archaeology in the Southern Levant. In Lahav II: Households and the Use of Domestic Space at Iron II Tell Halif: An Archaeology of Destruction. University Park: Penn State University Press, pp. 35–83. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Timothy P. 2012. West Syrian megaron or Neo-Assyrian Langraum? The Shifting Form and Function of the Tell Ta’yinat (Kunulua) Temples. In Temple Building and Temple Cult. Edited by Jens Kamlah. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, Ralph K. 2012. The Iron Age I Structure on Mt. Ebal: Excavation and Interpretation. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, Brian J. 1990. Pig Lovers and Pig Haters: Pattern of Palestine Pork Production. Journal of Ethnobiology 10: 195–225. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, Brian J., and Paula Wapnish. 1997. Can Pig Remains Be Used for Ethnic Diagnosis in the Ancient Near East? In The Archaeology of Israel: Constructing the Past, Interpreting the Present. Edited by Neil A. Silberman and David B. Small. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, vol. 237, pp. 238–70. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, Liora K. 1986–1987. Faunal Remains from the Early Iron Age Site on Mt. Ebal. Tel Aviv 13–14: 173–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, Frances W. 1966. The Iron Age at Beth Shean. Philadelphia: University Museum, University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Chang-Ho. 1997. A Note on the Iron Age Four-Room House in Palestine. Orientalia 66: 387–413. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Chang-Ho. 2012. The Early Iron II Temple at Khirbat Ataruz and Its Architectural and Selected Cultic Objects. In Temple Building and Temple Cult: Architecture and Cultic Paraphernalia of Temples in the Levant (2.–1. Mill. B.C.E.). Edited by Jens Kamlah. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 203–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Chang-Ho. 2016. One Tale, Two ‘Ataruz: Investigating Rujm ‘Ataruz and Its Association with Khirbat ‘Ataruz. Studies in History and Archaeology of Jordan 12: 211–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Chang-Ho. 2018. A Moabite Sanctuary at Khirbat Ataruz, Jordan: Stratigraphy, Findings, and Archaeological Implications. Levant 50: 173–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Chang-Ho, and Aaron Schade. 2021. Excavating a Monumental Stepped Structure at Khirbat Ataruz: The 2016–17 Season of Fieldwork in Field G. Andrews University Seminary Studies 58: 227–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Chang-Ho, and Aaron Schade. 2022. The Iron IIB–IIC Period at Khirbat ‘Ataruz. Studies in History and Archaeology of Jordan 14: 267–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Chang-Ho, Aaron Schade, Choong-Ryeol Lee, and Ellie S. Martin. Forthcoming. Khirbat Ataruz 2019–23: Further Light on the Temple’s Courtyard and Monumental Staircase. Andrews University Seminary Studies.

- King, Philip J., and Lawrence E. Stager. 2001. Life in Biblical Israel. London: Westminster John Knox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kisilevitz, Shua. 2015. The Iron IIA Judahite Temple at Moza. Tel Aviv 42: 147–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kletter, Raz, Irit Ziffer, and Wolfgang Zwickel. 2010. Yavneh I: The Excavation of the ‘Temple Hill’ Repository Pit and the Cultic Stands. Fribourg: Academic Press Fribourg. [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin, John C. H. 1981. The Remarkable Discoveries at Tel Dan. Biblical Archaeology Review 7: 20–37. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Baruch A. 1989. Leviticus. JPS Torah Commentary. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. [Google Scholar]

- Loud, Gordon. 1948. Megiddo II: Seasons of 1935–39: Text and Plates. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lyman, R. Lee. 1994. Vertebrate Taphonomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Macalister, Robert A. S. 1912. The Excavation of Gezer, 1902–1905 and 1907–1909. London: Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom, Jacob. 1991. Leviticus 1–16. Anchor Bible Commentary. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, Robert A. 2012. The Late Bronze and Iron Age Temples at Beth-Shean. In Temple Building and Temple Cult. Edited by Jens Kamlah. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 127–58. [Google Scholar]

- Netzer, Ehud. 1992. Domestic Architecture in the Iron Age. In The Architecture of Ancient Israel. Edited by Aharoni Kempinski and Ronny Reich. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, pp. 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, Mirko. 2012. The Temple of ‘Ain Dara in the Context of Imperial and Neo-Hittite Architecture and Art. In Temple Building and Temple Cult. Edited by Jens Kamlah. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Oren, Eliezer D. 1992. Palaces and Patrician Houses in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages. In The Architecture of Ancient Israel. Edited by Aharoni Kempinski and Ronny Reich. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, pp. 105–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pardee, Dennis. 2002. Ritual and Cult at Ugarit. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. [Google Scholar]

- Petit, Lucas, and Zeidan Kafafi. 2016. Beyond the River Jordan: A Late Iron Age Sanctuary at Tell Damiyah. Near Eastern Archaeology 79: 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, James B. 1985. Tell es-Sa’idiyeh: Excavations on the Tell, 1964–1966. Philadelphia: University Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, Ronny. 1992. Palaces and Residences in the Iron Age. In The Architecture of Ancient Israel. Edited by Aharoni Kempinski and Ronny Reich. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, pp. 202–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Steven A. 1991. Cupmarks and Rock-Cut Installations in the Negev. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 284: 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Sapir-Hen, Lidar, Guy Bar-Oz, Yuval Gadot, and Israel Finkelstein. 2013. Pig Husbandry in Iron Age Israel and Judah: New Insights Regarding the Origin of the ‘Taboo’. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 129: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer-Elliott, Cynthia. 2016. Food in Ancient Judah: Domestic Cooking in the Time of the Hebrew Bible. Sheffield: Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Shiloh, Yigal. 1970. The Four-Room House: Its Situation and Function in the Israelite City. Israel Exploration Journal 20: 180–90. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Mark S., and Wayne T. Pitard. 2009. The Ugaritic Baal Cycle. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, Margreet L., and P. M. Michele Daviau. 2024. Field A: Domestic Complex and Temple Building. In The Iron Age Town of Mudayna Thamad, Jordan: Excavations of the Fortifications and Northern Sector (1995–2012). Edited by Robert Chadwick, P. M. Michele Daviau, Margreet L. Steiner and Margaret A. Judd. Oxford: BAR Publishing, pp. 109–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ussishkin, David. 2004. The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973–1994). Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 22. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wapnish, Paula, and Brian J. Hesse. 1991. Faunal Remains from Tel Dan: Perspectives on Animal Production at a Village, Urban, and Ritual Center. Archaeozoologia 4: 9–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wapnish, Paula, Brian J. Hesse, and Anne Ogilvy. 1977. The 1974 Collection of Faunal Remains from Tell Dan. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 227: 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willet, Elizabeth A. R. 1999. Women and Household Shrines in Ancient Israel. Ph.D. thesis, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Zertal, Adam. 2018. A Nation Is Born: The Altar on Mount Ebal and the Birth of Ancient Israel. Haifa: The Samaria & Jordan Rift Valley Survey Association. [Google Scholar]

- Zorn, J. R. 2023. Domestic Architecture, the Household, and Daily Life in Iron Age Israel. In The Ancient Israelite World. Edited by K. H. Keimer and G. A. Pierce. London: Routledge, pp. 119–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zukerman, A. 2012. A Re-Analysis of the Iron Age IIA Cult Place at Lachish. Ancient Near Eastern Studies 49: 24–60. [Google Scholar]

| Phase | Chronology | Date | S/G | Deer | Cattle | Bird | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Surface | 20 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 21 | |

| 2 | Mid-Islamic | 13th–15th CE | 32 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 33 |

| 3 | Rock Tumble | Iron II or Post Iron II | 64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 64 |

| 4 | Iron IIBc | L8th–E7th BCE | 112 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 116 |

| 5 | Iron IIBb | 8th BCE | 80 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 84 |

| 6 | Iron IIBa (TP III) | L9th–E8th BCE | 1052 | 38 | 13 | 0 | 1103 |

| 7 | Late Iron IIA (TP II) | E–M9th BCE | 2139 | 118 | 38 | 1 | 2296 |

| 8 | Late Iron IIA (TP I) | E9th BCE | 105 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 111 |

| Total | 3604 | 171 | 52 | 1 | 3828 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ji, C.-H.; Lee, C.-R.; Cao, V. Ritual Kitchens and Communal Feasting: Excavating the Southeastern Sector of the Ataruz Temple Courtyard, Jordan. Religions 2025, 16, 1272. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101272

Ji C-H, Lee C-R, Cao V. Ritual Kitchens and Communal Feasting: Excavating the Southeastern Sector of the Ataruz Temple Courtyard, Jordan. Religions. 2025; 16(10):1272. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101272

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Chang-Ho, Choong-Ryeol Lee, and Vy Cao. 2025. "Ritual Kitchens and Communal Feasting: Excavating the Southeastern Sector of the Ataruz Temple Courtyard, Jordan" Religions 16, no. 10: 1272. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101272

APA StyleJi, C.-H., Lee, C.-R., & Cao, V. (2025). Ritual Kitchens and Communal Feasting: Excavating the Southeastern Sector of the Ataruz Temple Courtyard, Jordan. Religions, 16(10), 1272. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101272