Abstract

The first monographic exhibition dedicated to Vittore Carpaccio (ca. 1460–1525) in the US, and the first outside of Italy, was hosted at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, from 20 Nov 2022 to 23 February 2023 (from where it went to Venice). Building on the research of art historians and experts on Venice and the larger Mediterranean region in the early modern period, this paper examines Carpaccio’s depiction of various “Turks” in some of the large narrative painting cycles (teleri) commissioned by the devotional confraternities (scuole) in Renaissance Venice. While Carpaccio’s and the larger Venetian familiarity with Islam, including Turks, has been studied, this paper compares various female figures in the St. Stephen cycle with those in his St. George cycle, situating them in the larger historical context of the commissioning scuole (Scuola di Santo Stefano and Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, respectively). While attempting to uncover the significance, if not the identities, of a few individuals who stand out from the crowd, this paper urges caution when attempting to discern social history from a painting, much as we take literary texts (particularly those written well before our own times) with a grain of salt.

1. “Turks” Viewed Through the Teleri? Research Question and Methods

Vittore Scarpazze (Carpaccio; Latinized to Carpathius or Carpatio) was born shortly after the Ottoman takeover of Constantinople (1453). Living into the third decade of the 1500s (d. ca. 1525 in Koper, modern-day Slovenia), between 1490 and 1523, he was active in Venice.1 By 1513, Carpaccio was renting a property on the Grand Canal at San Maurizio, where he lived with his wife and two sons, who would also become painters (Matino et al. 2020). His signature medium was the teleri, large panel paintings that have been likened to the graphic novels of the Renaissance (Crawford 2022; cf. Holter 2023), a number of which have been lost or scattered. His art demonstrates the influence of the Bellini brothers and was commissioned by customers in Venice and provincial locations, including Istria (modern Slovenia).

Although Venice is today part of Italy, its origins lie with the eastern Roman empire, which was centered in Constantinople (now Istanbul). It was established in the 7th century as a Byzantine duchy dependent on Ravenna. Even into the Renaissance, as a commercial center sometimes at odds with the Papacy and other European powers, Venetian loyalties were occasionally questioned. In the words of Pope Pius II (d. 1464), “With their lips they favoured a crusade against the Turks but in their hearts they condemned it” (cf. Mt 15:8; Bowd 2016).

1.1. Awareness of “Turks” and Others in Renaissance Venice

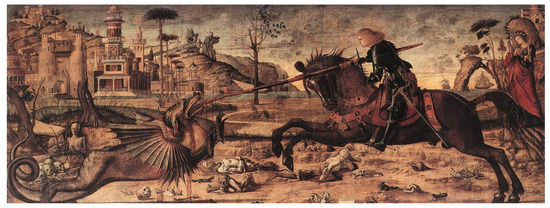

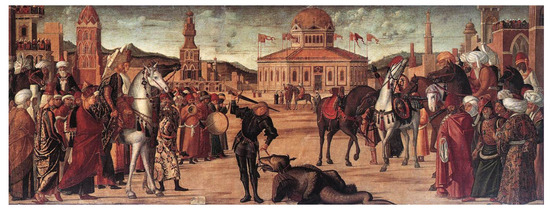

In many ways, Carpaccio’s depictions of Turks2 echo Pope Pius’ remarks. On the one hand, Turks figure as generic enemies in Carpaccio’s works: not only are the Turks represented by the dragon that St. George slays (Figure 1; Barker 2021, p. 43), they also feature—anachronistically—as those who persecute Stephen, a figure from the New Testament (Figure 2; Carboni 2007). This echoes contemporaneous depictions of the Turkish (Muslim) threat in civic and ecclesiastical realms throughout Europe3 (a threat tempered by the European victory at Lepanto in 1571, which is also widely depicted).4 To take just one literary example, a near contemporary, Martin Luther, penned On War Against the Turk within a few years of Carpaccio’s death, and two decades later wrote “Erhalt uns, Herr, bei deinem Wort”, a hymn that originally began with “Lord keep us in thy Word and work, Restrain the murderous Pope and Turk.”

Figure 1.

St. George and the Dragon (1502)5.

Figure 2.

The Stoning of St. Stephen (1520)6.

But, in art as in literature (see, e.g., Bisaha 2004), foreigners, including Turks and Muslims, are not always, or only, depicted as enemies. Indeed, Venice had diplomatic and commercial relations with the Ottomans—with Sultan Mehmed II even commissioning a portrait by Gentile Bellini around 1480 (see Rodini 2011). Carpaccio also lived during the Ottoman defeat of the Mamluks7 (of Turkic and Caucasian ethnic origins, they take their name from their former status as “slaves”),8 who, until 1517 and 1516, respectively, were the rulers of Egypt and Syria, with whom Venice conducted significant trade (Pixley 2003).

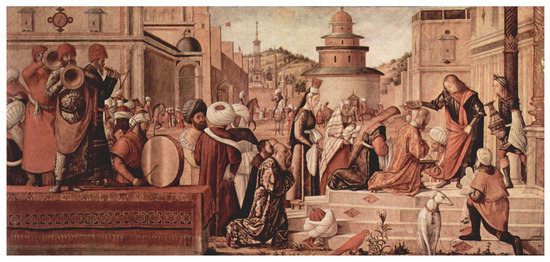

Reflecting this environment, Carpaccio’s Saint George cycle, executed between 1502 and 1507, in addition to the allegorical reference of the slain dragon (Figure 1 and Figure 3), also has eastern figures (Ottoman Turks or Mamluks or the Slavs themselves)9 as onlookers (Figure 3) and even being baptized (Figure 4).10 Even in some of the panels in the later Santo Stefano cycle (e.g., his Baptism, Preaching and the Dispute), Carpaccio has neutral, or friendly, Muslim figures; it is only in the final panel, Stephen’s martyrdom (1520), that Muslim figures appear exclusively as antagonists (Figure 2).11

Figure 3.

Triumph of St. George (1502)12.

Figure 4.

St. George Baptizing the Selenites (1507)13.

Ironically, more than the ever-present Ottoman threat, it was arguably a conflict with a fellow Christian nation, France, that colored Venetian attitudes to other faiths and peoples. Between 1509 and 1516, Venice was embroiled in the War of the League of Cambrai. And, it was in the aftermath of their defeat (by French forces) at Agnadello (1509), that the Patriarch of Venice, Antonio Contarini, appealed to the “cuore dei semplice” (Sgarbi 2015, pp. 311–13), through a stricter piety which tended to see a variety of “false” beliefs as equally problematic—be they Protestant (D’Andrea 2005), Jewish, or Islamic. Reflecting this development, scholars have noted the seeming transition from the “eastern friends” (as in the pre-Agnadello St. George cycle) to “enemies” in the Martyrdom of the 10,000 on Mt. Ararat (ca. 1515) or the stoning of St. Stephen (1520; Sgarbi 2015, p. 312).

1.2. The Venetian Ghetto

This War of the League of Cambrai saw some displaced Jewish communities taking refuge in Venice, as had some Iberian Jews when the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian peninsula (Granada) fell to Spanish Christians (1492), with the resultant expulsion of its Jewish communities. These recent arrivals contributed to the establishment of the Ghetto towards the end of Carpaccio’s life. In fact, the Santo Stefano teleri (1511–1520), the final ones that Carpaccio would execute, have been understood as an example of changing attitudes towards Jews, reflected also in the sermons of popular preachers and culminating in the segregation of the ghetto (See esp. Rusconi 2004).

Despite contemporary connotations of the word (on which, see Schwartz 2019), its establishment has a multifaceted history and lends itself to nuanced interpretation (Segre 2025). In fact, judging by the notes of a contemporary diarist, Marin Sanudo, in which the mandate to move to the ghetto in early spring 1516 is mentioned alongside discussion of the weather and foreign affairs, its establishment seems to have been a mere news item, of no greater interest than a storm (Segre 2025, pp. 118–19). Further underscoring the anticlimactic nature of its establishment (especially if contrasted to the spectacle of the Inquisition), the Health Department was the first government body to address problems arising from the relocation of Jews to a small, impoverished area (Segre 2025, p. 119).

With the ghetto, Venice would not expel its Jews (thereby losing their financial assets to rival powers), and Jews would neither lose their belongings nor have to choose between baptism and migration (Segre 2025, p. 122; cf. Gruber 2017, pp. 74–90). Even before the establishment of the ghetto or the defeat at Agnadello, the Venetian economy had relied heavily on Jewish money lenders—and had rejected Franciscan attempts to establish Christian financial establishments (Pullan 2004). Although the violence against Jewish individuals and families certainly argues for a precarious position of Jews in Venice on the eve of the establishment of its ghetto, crimes against Jews did not go unpunished.14 And, although Franciscans were known for fiery sermons against Jews, Venetian authorities also attempted to halt some of the incendiary preaching (Hughes 1986, pp. 3–59, n. 89). Additionally, a number of the literati were interested in Hebrew and also Jewish kabalah.15 Finally, particularly relevant to our discussion, despite sartorial laws mandating distinguishing marks for Jews, their enforcement was not uniform.16

1.3. Research Question and Methods

In surveying the literature on Carpaccio and larger Renaissance Venice, I was struck by the number and variety of Venetian interactions with its Muslim neighbors and the larger Mediterranean. I found thorough discussions of Carpaccio’s draftmanship (Whistler 2018), the reception history of his works (e.g., Del Puppo 2012), the commissioning scuole, and the current locations of many of his pieces. But, although many of the individuals in Carpaccio’s works appear portrait-like in their execution, I could find very few discussions of the identities of the individuals behind the pictures.17 I did, however, find robust discussion about the degree of verisimilitude in his works (Del Puppo 2009, pp. 137–45), his skillful depiction of topographic and natural details (Marshall 1984), as well as garments and fabrics.18

One aspect of Carpaccio’s oeuvre that has been the subject of scholarly debate is the degree of historical realism present in his paintings. The works of many Renaissance artists, including Carpaccio and his contemporaries, reflect familiarity with accounts of the Holy Land and other regions (Ross 2014; Germain-De Franceschi 2010, pp. 129–49; Marshall 1984) as told by pilgrims, scholars, and merchants. Some of these depictions, albeit with architectural or chronological inaccuracies, are our only pictorial record of certain Muslims of the time.19

Bearing in mind the challenges of separating historic reality from artistic license, this paper focuses on some women (cf. Lacouture 2012) who feature in his teleri that were commissioned by two separate schools: the San Giorgio and Santo Stefano cycles. Scholars have discussed various female figures in Carpaccio’s and other Renaissance works. My own investigation grew from an initial examination of the women listening to Santo Stefano, to a closer look at other female figures in his teleri, particularly those that depict Muslims and women. Although a comprehensive investigation into the daily lives of Early Modern women, be they Jewish, Christian or Muslim, Venetian, Ottoman or Mamluk, is beyond the scope of this discussion, as is technical art historical analysis, the following “reads” Carpaccio’s teleri as one might historical texts. Through close comparison of small details, it attempts to see these women as Carpaccio and the early viewers may have. How clearly is confessional, or ethnic, identity signaled through adornment or clothing?

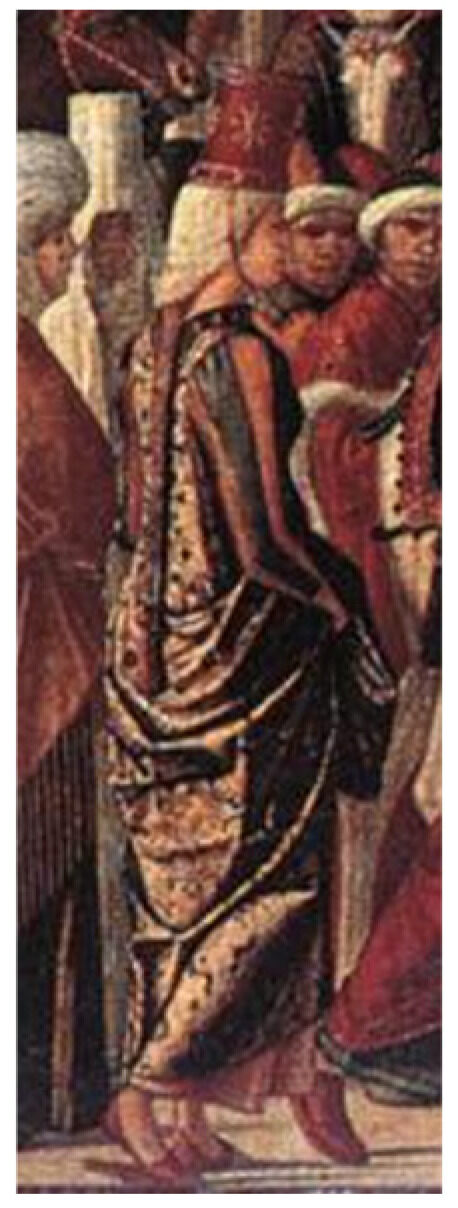

Despite some intentional misrepresentations (e.g., biblical villains ahistorically dressed in Ottoman garb, as in the stoning of St. Stephen; Figure 2), many details of the costumes of the individuals who appear in his teleri conform to descriptions found in contemporaneous written accounts, as well as to drawings or woodcuts of other artists of his day. For example, Carpaccio’s sketch of Two Standing Women, One in Mamluk Dress (n.d.), now at the Princeton Art Museum20 is strikingly similar to the women at the left-hand side of Saracenes in Damascus, a woodcut in von Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam (Figure 5; discussed in Ross 2014, p. 83; see also Ross 2007). The two figures appear at the left of the Triumph of St. George (Figure 3, detail in Figure 6), although in different positions. As discussed below, modified versions of this sketch may also appear in the Baptism of the Selenites (Figure 4, detail in Figure 7) and the Ordination of St. Stephen (1514, detail in Figure 8).

Figure 5.

Saracenes in Damascus, von Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio21.

Figure 6.

St. George Triumph, detail22.

Figure 7.

St. George Baptizing, detail23.

Figure 8.

St. Stephen Consecration, detail24.

The other grouping of women discussed here is the group of five listening to Santo Stefano (Figure 9). The color scheme is arresting: three wear red pillbox hats with veils of different colors attached; one has a blue pillbox hat with a veil; and a fifth woman is all in white, with her face half-covered, showing only her nose and mouth. In contrast to her companions, her gaze is downcast, averted from the speaker, strongly invoking Late Medieval images of blindfolded, or downcast, Synagogue (although in Christian art, Synagogue often has her head bared; see, e.g., Rubin 2014). Commonly interpreted as representing the Synagogue, her garments also resemble the taqiyya-wearing (Muslim) women in contemporaneous drawings such as Bellini’s Preaching of St. Mark in Alexandria (1504–1507).

Figure 9.

Sermon of St. Stephen, detail (1514)25.

As they have been variously identified as Jewish or Muslim, the following looks at these women together with the aforementioned women in the St. Stephen and St. George cycles, paying particular attention to three details of ornamentation: earrings, stripes, and veils. It represents a modest attempt to contribute to discussions on the depictions of Muslim and other women in Renaissance Venice—ever mindful of artistic license, donors’ whims now lost to us, as well as the possible variety of sources for his works (e.g., the Golden Legend; on which, see, e.g., Reames 1985).

2. Venice and Its Schools (Scuole, Sing. Scuola)

Notably, through the domestic and international turmoil in the Early Modern period, Venice had a flourishing artistic scene and, politically and commercially, attracted the attention of foreigners and inhabitants of other parts of Italy. Jewish communities were not the only displaced persons in this period. Some of the communities that fled the Ottoman advance found refuge in Venice, sometimes preserving their memories of Ottoman aggression (and, presumably, other prejudices)26 in public art, as illustrated by the 1530 facade of the Albanese confratelli, which features Mehmet II wearing a turban and a crown and bearing a scimitar. He stands beneath the fort of Scutari, the siege of which in the 1470s led to the exodus of many Albanians to Venice (Irena 2017).

Many of the immigrant communities, as well as merchants and artisans, gathered together in devotional confraternities, or “scuole” (sing. scuola). When they were able, these scuole might commission an artist to decorate their church or gathering place (as did the Dalmations who commissioned Carpaccio’s St. George cycle). Also among the patrons of Carpaccio’s work were some of the devotional schools in Venice that drew upon various artisan groups for their membership.27 These scuole were not confined to the inhabitants of a particular zone, or to men. They could be centered around a saint, or linked by nationality, or, eventually, based on the cult of the Eucharist. And, while over 200 were recorded in the 1500s (the historian Marin Sanudo, for example, counted the flags of 210 distinct confraternities at the funeral of Cardinal Zen in 1501; e.g., Quaranta 2018, p. 80), many were disbanded under Napoleon. As many contracts between the artist and the school have not survived (e.g., C. Brooke 2004, p. 310), the rationale for particular elements in the teleri, including the identities of individuals depicted therein, remains a matter of speculation.

2.1. Scuola Degli Schiavoni

Some scuole, like the one that commissioned the St. George cycle (Figure 1, Figure 3, and Figure 4)28, were both linked by nationality and centered around a saint (or saints): the Scuola Dàlmata dei Santi Giorgio e Trifone, also called the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni (the Dalmatian School of St. George and St. Triofonus, or the School of St. George of the Slavs).29 Between 1501 and 1509, Carpaccio executed various teleri for this school (for some examples, see Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). Although they remain in the possession of the scuola, their original placement is unknown. Additionally, no records of Carpaccio’s patrons for his San Giorgio cycles are known to survive. They were likely commissioned as part of a renovation and refurbishment project of the scuola, possibly for its Jubilee. His work for the scuola coincides with the gifting of a relic of St. George by Paolo Valaresso, a commander of Venetian fortresses that had fallen to the Turks in 1499. The relic was transferred to the scuola on 24 April 1502. This Narrative Cycle reflects Carpaccio’s methods well: in addition to the dragon, which comes from the aforementioned Golden Legend, Carpaccio includes details mirroring contemporaneous descriptions of this event, such as trumpets and pipes, colorful garments, and flags in the Triumph of St. George (Figure 2).30

Unlike the artisan guilds, which were specific to a single trade or a group of related occupations, scuole could also include members from different trades; it has been argued that this was likely the case of the scuola that commissioned the other cycle discussed here (that of St. Stephen).

2.2. Scuola di Santo Stefano

The Scuola di Santo Stefano, one of the oldest Venetian confraternities, was founded in 1298. Although sometimes termed laneri (textile workers), by Carpaccio’s day, the members likely included stone masons and stone cutters (tagliapietra e lapicidi), for whom St. Stephen is the patron saint, as, according to the biblical account (Acts 7:59), he was stoned to death. Proponents of this hypothesis point to the details of the stone work in the Santo Stefano cycle, as well as the harmony between nature and architecture, which is unparalleled in Venetian art of the early 1500s, but which evokes the highly refined Lombard classical revival style.31

This scuola was first housed in the Augustinian convent (now the home of Inland Revenue!32) in Campo di Santo Stefano, but eventually was granted its own building nearby (now a mixed commercial-residential building). It was here, on the third floor, that Carpaccio worked, until at least 1520, on the five panels of his St. Stephen cycle (I. Brooke 2024). Unlike the three parts of the St. George cycle executed between 1502 and 1507 (Figure 1, Figure 3, and Figure 4), which remain in the building, if not the exact location, of their original placement, the five paintings in the St. Stephen cycle33 were dispersed after the Napoleonic dissolution of the scuola.

As with other campi, Santo Stefano would host public theatrical displays on feast and wedding days (I. Brooke 2024, p. 22; Henry 2023, pp. 223–44). In 1515, a performance of a comedy in its refectory was attended by a large crowd, including the Doge’s son! (I. Brooke 2024, p. 22) Irene Brooke has highlighted research that hints at the involvement of the Augustinian friars themselves (perhaps most well known as the order to which the Protestant Reformer Martin Luther belonged) in these productions. On a darker note, the square of Santo Stefano had also been the scene of a brutal murder of a Jewish merchant, Aron, on 12 September 150334—a crime memorialized by the aforementioned Sanudo. Additionally, perhaps inspiring Carpaccio’s depiction of the Preaching (Figure 10), the square also served as a popular preaching podium: for example, in his Diario, the contemporary historian Marin Sanudo notes that on Christmas day in 1520, the friar Andrea da Ferrara preached to a large crowd gathered in the square, openly attacking the Pope and his court.35

The scuole as patrons of the arts, and the squares as centers of entertainment, dissent, and information reflect the vibrancy of Venetian civic life—a vibrancy that also had its critics. A late 16th century encyclopedia of professions, in fact, stigmatizes those who “spend all of their time strolling in the square, going from the taverns to the fishmongers and from the palace to the loggia, doing nothing else all day but wandering here and there, now hearing singing among the stalls...now wasting time at the barbershop telling tales, now reading the news.”36

The vibrancy of Santo Stefano as described in contemporary accounts leads to the inevitable question: would contemporary viewers have seen echoes of their own Campo in the Preaching of Santo Stefano (Figure 10)? For, as with the San Giorgio cycle commissioned for the Scuola degli Schiavoni, the Santo Stefano cycle has a particular significance for the commissioning scuola: depiction of key events of the vita of its patron saint. Both works also contain details reflecting the commissioning milieu. As noted above, the ceremonial parade in the Triumph of St George (Figure 3) reflects the parade that accompanied the translation of the relic in 1502. Such a chronological mash-up might well confuse the uninitiated viewer. (When I first saw the Preaching of St Stephen at the Louvre a decade ago, I was taken aback by the minarets towering over a New Testament figure; see Figure 10). But, as various scholars have noted, Carpaccio was a master of seemingly seamlessly intertwining a fantastic, miraculous, or historical episode with details familiar to his patrons’ quotidian routine.37

Figure 10.

The Sermon of St. Stephen (1514)38.

3. Social History in the Teleri? Parsing Social, Sectarian and Ethnic Identities Through Earrings, Stripes and Veils

Patricia Fortini Brown has noted Venetian attachment to the Chronicle, even when neighboring regions were seeing the emergence of humanist historiography. Unlike the humanist historiography, which was almost an artistic production, the Chronicle was often anonymous and, especially after 1350, filled with descriptive detail, especially of daily life, considered essential for historical authenticity (Brown 1984, pp. 263–94, esp. 277–79). She places Carpaccio’s teleri squarely in the context of this literary genre. The artist, like the chronicler, had to select the relevant information from earlier texts, update it, and add his own observations. In their attention to descriptive detail and inclusion of notes of mundane importance, both the Chronicle (like that of the aforementioned Marin Sanudo)39 and Carpaccio’s cityscapes bring to life the varied people, and activities, seen at the campi, or piazze, of Renaissance Venice.

With these observations in mind, let us examine a few of the women in Carpaccio’s teleri for indications of their social, sectarian, or ethnic identity. While their identities are (as yet) unknown, do their clothing or other adornment shed new light on the awareness of Jewish, Muslim, or other women in his milieu?

3.1. Earrings

Based on their clothing and hairstyles, the four women listening to St. Stephen’s sermon with their faces uncovered (Figure 9) are understood to be Jewish women (for example, various shades of yellow can be seen on their clothing).40 Women with similar (Levant-style?) headdresses also feature in Carpaccio’s St. George cycle (Figure 6 and Figure 7). They also appear in the Consecration of St. Stephen (Figure 8), seemingly wearing earrings, which is also considered a possible indication of Jewishness.41 By contrast, the women listening to Stephen’s Sermon all have their hair covering their ears, so any such adornment would not be visible. (A woman with a similar headdress in the Triumph of St. George, Figure 6, also has her ears covered by fabric.)

Although women in various parts of Christian Europe had worn earrings, they were gradually phased out in many areas in the 12th century; Jews, but also Slavic areas, seem to have maintained the tradition of wearing earrings. The move away from earrings was, however, short-lived—as the 16th century increasingly saw aristocratic women donning them (a trend that, like many others, did not escape the diarist Marin Sanudo) (Hughes 1986, p. 11 n. 18; 39; cf. Simons 2023)—albeit more as drop earrings than the circles that would still mark Jews and other foreigners.42 Given the variety of trends and attitudes towards such adornments in a wide range of cultural settings, earrings may not prove to be a particularly accurate sectarian or ethnic marker.

3.2. Stripes

While the red hat and the posture of the woman on the left in the details of both St. George Baptising (Figure 7) and the Consecration of St. Stephen (Figure 8, which has two additional women) are reminiscent of the left-hand figure in Carpaccio’s aforementioned sketch of Two Standing Women, the woman to the right who had been wearing a taqiyya-style headdress in Carpaccio’s sketch and in the Triumph (Figure 6) has been replaced by a woman with a striped veil. She stands in a similar pose to the woman of Carpaccio’s sketch and the Triumph of St. George, but her face is fully visible—dark-complexioned in the St. George Baptizing the Selenites (Figure 7); lighter in the Consecration of Stephen (Figure 8). Stripes, or striations, can also be seen in the woodcut in von Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio (Figure 5) (Von Breydenbach 2010).

Other artists of his day incorporated striped fabrics in their works (e.g., Bellini, Giorgione, Mansueti)—with, arguably, various nuances.43 In contradistinction to Carpaccio, however, the aforementioned artists placed stripes on male, not female, subjects—at least two of which seemingly on individuals of eastern origins. (A few decades later, Titian would dress an African servant girl in stripes in Diana and Actaeon [1556–1559]). Carpaccio’s striped veils bear a marked resemblance to striped silk fabric from Mamluk Egypt (Behrens-Abouseif 2023, pp. 138–40). But, by Carpaccio’s day, striped cloth of the attabi style44 was also popular in Europe. Although originally produced in Attabiya, a quarter of Baghdad, it was also produced in al-Andalus (Rodríguez Peinado and Cabrera-Lafuente 2020) and elsewhere. Following Bethany Walker’s caution (Cited by Rodríguez Peinado and Cabrera-Lafuente 2020, p. 28), it would be difficult to discern the provenance of the fabric as European silks tried to imitate those from the east, while “weavers in China produced Islamic designs for the Mamluk market”!

An initial read is that the women with the striped veils are servants, as stripes may have negative connotations or indicate foreigners in European art.45 But, while stripes were associated with the east (sometimes also signaled by darker-complexioned figures (Stošić 2017, pp. 1033–40) or inferior social status, he dresses both a dark-skinned woman in The Baptism of the Selenites (Figure 7) in stripes,46 as well as a fair-skinned woman in the same position in the Consecration of Saint Stephen (Figure 8) in nearly identical striped shawls. That nearly identical fabric appears in teleri for two separate scuole argues against the fabric having significance for a particular scuola.

Like the black gondolier in the Miracle on the Rialto, who is dressed with the same flamboyance as the other gondoliers (Lowe 2013, pp. 412–52), do such subtle parallels in Carpaccio’s work underscore the variety—and fluidity—of race (and religion) and class present on the squares and canals of Renaissance Venice? Do the stripes signal something beyond racial otherness—possibly a class distinction?

3.3. Veils

Although veiled women are, in modern discourse, frequently associated with Islam, the veiling of women is neither exclusive to Islamic tradition nor uniformly practiced by Muslim women, past or present. In fact, while Mamluk women (exclusive of servants) were generally depicted fully covered, contemporaneous images from the Islamic east represent women generally unveiled (Rapoport 2007, p. 8). While the Mamluk style of female covering (the taqiyya) is visually striking and, as with the variety of Mamluk male headgear, caught the attention of numerous Renaissance artists (Bellini’s Preaching of St. Mark; Carpaccio’s Preaching of St. Stephen, see Figure 10; cf. also Figure 6), in Carpaccio’s day, Venetian women would also cover their hair and also their faces for various reasons. The “deserving poor” (poveri vergognosi)—frequently upstanding women who, through widowhood, had fallen on hard times—were one group of white-veiled women; a confraternity dedicated to their relief was even established in the 1500s.47 Even (young) unmarried women in Venice may have resembled their taqiyya-clad Mamluk counterparts, based on Jean Jacques Boissard’s Virgo Veneta (unmarried Venetian woman wearing a cappa, albeit slightly later than Carpaccio) (Reproduced in Burghartz 2015, p. 2, See also 31, n. 54; Cf. Jones 2009, pp. 511–44).

While taqiyya-clad women (or their retinues) were unlikely to have accompanied Muslim notables or merchants visiting the Serenissima, Mamluk merchants and scholars were known to travel with a slave girl, or to engage in temporary marriages while away from home.48 Although Mamluks reportedly prized fair-skinned Turkish concubines, servant girls could be light or dark-complexioned (Rapoport 2007, p. 14). Might the women with uncovered faces wearing distinctively striped shawls reflect Carpaccio’s awareness of the difference between Mamluk slave girls and their owners? For, unlike their owners, slave girls (except concubines) would not have had their faces uncovered.49 Could the women with the striped veils reflect an awareness of servant girls accompanying Mamluk or other foreign embassies? (In addition to its well-known ties to the Mamluks, the century beginning with the 1460s has been described as the “golden age” of Veneto-Safavid relations; cf. Rota 2009, p. 28).

Alternatively, given the diffusion of striped fabric and the mobility of populations, might the striped shawls reflect an increasing presence in the Serenissima of communities that wore such headcoverings (Slavs fleeing the Ottomans,50 or communities expelled from Spain, where Christian and Muslim women were known to wear the almalafa, a wrap that could be left hanging or drawn to cover the face)? In fact, the style of the striped shawl in Carpaccio’s teleri (a tight headband with long flowing fabric that could, if desired, be drawn around the upper body and face) is particularly reminiscent of the Andalusian almalafa- a “Moorish female clothing” (although not specified as striped, and worn by both Christian and Muslim women) seemingly prohibited by law in Granada in 1511.51 Especially as the attabi fabric was produced in al-Andalus, might the two women wearing these coverings reflect the presence of Spanish immigrants in Venice, possibly serving as domestic servants? Further research into the foreign embassies present in Venice, as well as the clothing of various people present in Venice at the time, may shed further light on the significance of the two women with striped veils.

The final adornment we discuss is a veil that partially covers the face of the central woman in the group listening to Santo Stefano (Figure 9). Instead of a traditional reading of this white-clad woman as a Synagogue, Stoichita argues for her as a representation of Islam (Stoichita 2019, pp. 40–41, 64). Indeed, the white garments that cover her head seem to have a square hat beneath the veil, resembling those of the taqiyya-clad women in the background of the telero as well as those in Bellini’s St. Mark Preaching in Alexandria, as well as von Breydenbach’s Saracenes (Figure 5)52 or Carpaccio’s Two Standing Women. But, as none of these groups appear to have veiled their eyes but not their mouths, I would agree with a reading of the half-veiled woman as Synagogue, possibly reflecting the fashion seen among some of Venice’s Jewish inhabitants, especially the relatively recent Spanish community, many of whom had come as merchants, via the Levant.53

The style of concealment (covered hair and eyes, with only her mouth and nose showing), however, defies easy classification. For Islamic face coverings often allow the eyes to be seen, but cover the hair and, sometimes, also the nose and mouth (as seen in a number of the women in Bellini’s representation, whose lower faces are more fully obscured than their eyes); generally, it is Synagogue who is blindfolded in European art—but with her hair and the rest of her face visible. The closest approximations to this style of face covering seem to come from Spain, as, for example, the (albeit later) depiction of a woman in Madrid, with a sheer black half-face veil covering her eyes but revealing her nose and mouth (Bass and Wunder 2009, p. 125). Might, then, the white-clad woman with her upper face covered reflect a Spanish, but Jewish, presence in Carpaccio’s Venice? Again, further research into the contemporaneous clothing of Venice’s Jewish communities may shed light on the significance of this figure.

4. Concluding Reflections

Assuming that the characters who “make up Stephen’s motley audience” were “not all that dissimilar from the people the painter might have seen with his own eyes, around 1500, in the squares and back alleys of Venice (Stoichita 2019, p. 39),” this study has examined Carpaccio’s use of earrings, stripes and veils for possible social, ethnic and/or confessional signifiers in teleri that were commissioned by two separate scuole.

It concludes with more questions than answers. While Jewish women may well have worn earrings (or tried to hide them), the diversity of Venice’s population and the range of attitudes towards this adornment argue against earrings alone as a particularly accurate class, sectarian, or ethnic marker. It also found further research to be needed on the composition of the Mamluk (or other) diplomatic missions to Venice, as well as the clothing trends among the recent immigrant communities, to interpret the striped veil on two women, one watching St. George Baptizing the Selenites, the other attending St. Stephen’s consecration. Does this veil indicate an awareness of Mamluk class distinctions, or reflect the distinctive clothing of recent (Spanish) immigrants in Venice? Finally, further research on the specifics of Jewish (Spanish, Levantine) clothing may inform our understanding of the ethnicity of the white-clad woman with a partial face veil, who is listening to the preaching of St. Stephen.

Viewers at a chronological, cultural, and geographic remove must be particularly careful not to ascribe undue significance to aspects of the teleri that resonate with their own worldview. While Patriarch Contarini may have warned against a Jewish, Muslim, or Protestant danger, he did not restrict his admonitions for repentance to external threats. After the earthquake of 1511, he called for three days of fasting, attributing the earthquake to the sins of the Venetians!54 In addition to turbaned antagonists, St. Paul (also as Saul) appears in both of Carpaccio’s depictions of the stoning of St. Stephen. Could this reference the Christian need for repentance, in addition to Jewish/Muslim culpability?55 As Nirenberg cautioned with assigning predictive value to medieval Holy Week riots (Nirenberg 2015, p. 229), there is the danger of ascribing ahistorical significance to a work of art—or a literary text.

To conclude on a cautionary note. The inclusion of details intended to create a sense of verisimilitude could also serve to cast a realistic appearance on a fictional, or fantastic, situation—to invent a history, often for didactic or polemical purposes. Sidney Griffith has noted this tendency in Christian debate texts from the early Islamic period, in which a Christian monk is frequently portrayed in a socially realistic (and subservient) position vis-a-vis his Muslim interlocutors. Subtle allusions to difference in status, or language, emphasize both the social inequalities, as well as underscore the strength of the Christian’s faith (and intellect)—not to mention his ability to best his Muslim opponent(s)! (Griffith 2010, pp. 29–54). As with early Christian-Muslim debate texts, the social verisimilitude of Carpaccio’s oeuvre raises the question of its historicity, while encouraging reflection on the message behind the painting (Griffith 2010, p. 52). Especially given the multi-ethnic (and sectarian) makeup of Venetian society, as well as the contacts with other regions that many Venetians enjoyed—e.g., as recent immigrants, merchants, etc.—details such as clothing (veil), fabric (striped, embroidered), adornment (earrings), even how a garment is draped, may further nuance our appreciation of Carpaccio’s work, and the Venice of his day.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Carpaccio’s images are available in the public domain, as indicated in the references.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For discussion of his possible familial ties to Istria, see (e.g., Knez 2021). |

| 2 | The complexity and nuances of contemporaneous European nomenclature for, and approaches to, Islam are beyond the scope of this discussion. See (e.g., Tolan 2002; Brann 2009). See (Barker 2021) for a cautionary note about the designation of “Ottoman Turk.” |

| 3 | Arjana (2015). In addition to innumerable paintings held in various galleries, see the Landplagenbild on the Cathedral Wall in Graz, Austria (1480). https://squamcreativeservices.com/2015/07/landplagenbild-dom-graz-austria/, accessed on 20 September 2025. |

| 4 | To give just a few examples of the place this battle holds in the collective memory of Europe, churches from Belgium (Sint Salvator, Bruges) to Malta (Mosta) depict the Victory. The former has a series of Miracle paintings attributed to Hendrik van Minderhout (bet. 1627–1654), which, according to their descriptions in the church, were made to be “situated in the devotion to Our Lady during the Counter Reformation in Europe, following in the victory of the catholic fleet against Turkey [los Turcos/die Turken] in the battle of Lepanto (1571).” In the Mosta Basilica in Malta, the altar dedicated to Our Lady of the Rosary has a silver frontal depicting the battle. Inaugurated on 10 August 1980, they were designed by Joseph Galea (Rabat, Malta) and executed by silversmith Tarcisio Cassar of Zejtun. They also depict Pope Pius V and Blessed Alan de la Roche on either end of the frontal. (Personal correspondence with George Cassar, 4 May 2023). To commemorate the 450th anniversary of the battle, Spain issued silver commemorative coins. https://tienda.fnmt.es/fnmttv/fnmt/en/Products/Coins/BATTLE-OF-LEPANTO-%282021%29-10-EURO-SILVER-COIN/p/92917006, accessed on 20 September 2025. See (e.g., Strunck 2011). |

| 5 | https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1c/Vittore_carpaccio%2C_san_giorgio_e_il_drago_01.jpg, accessed on 20 September 2025. |

| 6 | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vittore_Carpaccio_084.jpg, accessed on 20 September 2025, Now in the Staatsgallerie, Stuttgart. |

| 7 | Rateb (2023) provides a detailed discussion of the different Renaissance depictions of Ottomans and Mamluks. |

| 8 | A brief overview is found at Yalman (2001). For the Turkification of peoples under Mamluk rule, see (e.g., Mazor 2024). |

| 9 | On the possible influences of Carpaccio in these depictions, see (Brown 1988; cf. Barker 2021). |

| 10 | (Barker 2021, p. 41; For discussion of these “‘amici’ orientali”; see Sgarbi 2015, p. 311) on https://itunes.apple.com/WebObjects/MZStore.woa/wa/viewBook?id=0, accessed on 20 September 2025. |

| 11 | Carpaccio personifies the Ottomans as the true enemy by showing figures wearing the Ottoman style of turban wound around a red cap stoning the saint to death. In Carpaccio’s late works, which were contemporary to the fall of the Mamluk Sultanate to the Ottoman Turks, Muslims started being represented as evil and dangerous characters and were personified as Ottomans. Carboni (2007, p. 26). |

| 12 | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vittore_carpaccio,_trionfo_di_san_giorgio_01.jpg, accessed on 20 September 2025. |

| 13 | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vittore_Carpaccio_019.jpg, accessed on 20 September 2025. |

| 14 | See (Okey 1907, pp. 147–48) for a description of the punishment of a Franciscan priest who had murdered a Jewish family. |

| 15 | To name only a few: Egidio of Viterbo, Dardi Francesco Giorgio (Zorzi), of a noble family but ordained a Franciscan at San Francesco della Vigna. |

| 16 | For example, although legislation prohibited Jews from wearing yellow, black headgear could be worn by some, as in the case of the convert Fra Felice da Prato, who sought exemptions for some of his employees working on his Hebrew printing project, cited by (Ravid 2023, p. 243). |

| 17 | Cf. https://cavallinitoveronese.co.uk/general/view_artist/58, accessed on 20 September 2025, in which the men in black and red in the Disputation of St. Stephen are described as “presumably members of the confraternity”; the other figures are even less clearly identified: cf. the citation of their identification as a “group of wise Orientals,” in Tomasella (2020, pp. 165–87). |

| 18 | Behrens-Abouseif (2023, p. 181), commends the display of Mamluk turbans from different perspectives in Carpaccio’s ‘Stoning of St Stephen’, but also interprets the detached elaborate turban in his ‘Baptism of the Selenites’, next to his signature, as “a scene of devotion to display Orientalist fantasy.”; notably, Europeans were not the only ones struck by the variety of Mamluk headdresses. Even the Ottomans remarked upon it (Behrens-Abouseif 2023, p. 120). |

| 19 | For example, Behrens-Abouseif (2023, p. 181) notes that “We have no Mamluk manuscripts or artifacts to document women’s costume in the Circassian period. This is partly compensated for by European illustrations of the late 15th and early 16th centuries.” |

| 20 | Two Standing Women, One in Mamluk Dress (n.d.), compare with image from note 21. |

| 21 | Public Domain image (64 verso) available from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (although labeled as Jews): https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/338300, accessed on 20 September 2025. |

| 22 | See note 12, detail. |

| 23 | See note 13, detail. |

| 24 | Detail taken from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vittore_Carpaccio_%28um_1460-65_-_1525-26%29_-_The_Ordination_of_St._Stephen_-_23_-_Gemäldegalerie.jpg, accessed on 20 September 2025. |

| 25 | Detail taken from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sermon_of_St._Stephen_(Carpaccio)#/media/File:La_Pr%C3%A9dication_de_saint_Etienne_%C3%A0_J%C3%A9rusalem_de_Carpaccio.jpg, accessed on 20 September 2025, Now in the Louvre, Paris. |

| 26 | For example, the Albanians were the only group that the Mariegola of S. Giorgio degli Schiavoni excludes from its membership; I. Brooke (2024, n. 36). |

| 27 | (Humfrey 1988, pp. 401–23; Mackenney 1994, pp. 388–403). For an accessible overview of these scuole, see (The Churches of Venice n.d.). |

| 28 | On the significance of St. George for this school, and for a brief overview of its history, see (Barker 2021, pp. 26–54; more recently, Barker 2025, esp. 132–52). |

| 29 | I. Brooke (2024, p. 303; see p. 310) for a discussion of its history, including discord between the Knights of Rhodes and the Scuola. |

| 30 | I. Brooke (2024, p. 310) mentions trumpets and pipes, as well as the overall processional format of the Triumph, including colorful costumes and flags. |

| 31 | Particularly if the Scuola’s members had worked on some of the Venetian public monuments, might the disrepair into which some of the stone work in the Santo Stefano cycle (such as the podium from which Santo Stefano is preaching) has fallen recall the destruction of Venetian lions in Ravenna and Vicenza following the French defeat of the Serenissima at Agnadello in 1509? For the symbolic destructive acts in Lombard cities that characterized the defeat of Venice in 1509, see (Rospocher and Valseriati 2025, pp. 38–61, 44f.; Finocchi Ghersi 2017, pp. 23–40; cf. Gentili 1988, pp. 79–108). |

| 32 | For more details, see (Andrea Contarini’s Tomb in the Cloister of the Church of Santo Stefano in Venice n.d.) |

| 33 | The Consecration of Saint Stephen (and six companions) by St Peter (1514) is now in Berlin, Staatliche Museen—Gemäldegalerie; the Preaching of St Stephen (1514), is in the Louvre, Paris; the Dispute of St Stephen (1514), is in Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera; the Trial of St Stephen is lost, but a charcoal sketch survives in Florence, in the Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe no. 1687F; the Stoning of St Stephen (1520) is in Stuttgart, Staatsgalerie. In addition to the various art historical monographs (e.g., that of Sgarbi and others), this cycle is discussed in Stoichita (2019, p. 35f). |

| 34 | Segre (2025, pp. 113, 114) also discusses the possible circumstances of the murder. |

| 35 | Tassini (1879, pp. 20–21) reproduces Sanudo’s entries about Andrea da Ferrara (also 5 February 1520 and 23 March 1521). Even earlier, in 1505, Egidio (Giles in English) of Viterbo, who, like Martin Luther, was an Augustinian friar, preached not only at Santo Stefano but also, from the pulpit of San Marco itself, condemning the sins of blasphemy, to which he called on the Senate to put an end. |

| 36 | Rospocher and Valseriati (2025, pp. 54–55), quoting Tomaso Garzoni. |

| 37 | For a cautionary reading, see (Gudelj and Trška 2018, pp. 103–21). |

| 38 | See note 25. |

| 39 | Gaetano Cozzi, cited in Sanudo (2008, p. xx) |

| 40 | Ravid (1992, pp. 179–210); Katz (2008, esp. 180–81); for a thoughtful discussion of the multifaceted significance of the use of yellow, see (Yarmo 2016, pp. 19–31). |

| 41 | The resolution on the images available to me makes it difficult to distinguish a lock of hair from an earring. But see Hughes (1986, p. 40): “Carpaccio infused it with an eastern exoticism in his rendering of the St. Stephen cycle (1506–11), where the Jewish women who watch the confirmation of the Seven Deacons have elaborate ear-rings in their ears; and it is difficult to determine how Jewish he meant the sign to be.” (Cassen 2017; Cassen 2013, pp. 29–48; Lipton 2014). |

| 42 | Hughes (1986, p. 42); even into the 21st century, earrings are worn by the Zwarte Pieten who accompany Sint in the Netherlands: see (e.g., Brienen 2014, pp. 179–200). |

| 43 | Two men behind the group of veiled women in the foreground of the Bellini brothers’ St. Mark Preaching in Alexandria (1504–1507); Giorgione’s youth, discussed above: Cited by (Földes et al. 2024, p. 25, n. 93); the figure in the lower left of Mansueti, St. Mark Heals Anianus ca. 1507 appearing to be tending a small camel. |

| 44 | A taffeta fabric with silk warp and cotton woof, variously described as interwoven with gold, or as black and white, like a zebra. (Jacoby 2017, pp. 145, 150, no. 59). |

| 45 | In European art, stripes have had negative connotations or been associated with foreigners. Pastoureau (2001)—although Marin Sanudo also associates it with the prerogative of youth, perhaps along the lines of entertainment groups such as the Compagnia della Calza. Cited by (Földes et al. 2024, pp. 1–33, n. 9). |

| 46 | Similarity with Titian’s African servant in Diana and Acteon has been discussed: (Simons 2023, pp. 223–46), online at https://asu.pressbooks.pub/race-in-the-european-renaissance-classroom-guide/chapter/teaching-race-in-renaissance-italy/, accessed on 20 September 2025. |

| 47 | See (Nichols 2007, pp. 139–69) for depictions of these—dignified—poor. For female pious charitable orders (mantellate, bizzocale, pizzochere), see McFarland (2021, pp. 241–67); St. Stephen was also associated with caring for widows, noted by the compiler of the Golden Legend, Jacobus Voragine https://www.christianiconography.info/goldenLegend/stephen.htm, accessed on 20 September 2025. |

| 48 | (Rapoport 2007, pp. 1–47, 1; cf. Stillman 1976, pp. 579–89; Hoffman-Ladd 1987, pp. 23–50; Fuess 2008, pp. 71–94; Chatty 2014, pp. 127–48). Although see Behrens-Abouseif (2023, p. 157) for a brief note that Mamluk female slaves did cover their faces. Rapoport (2007, p. 29). |

| 49 | (Rapoport 2007, pp. 1–47, 1; cf. Stillman 1976, pp. 579–89; Hoffman-Ladd 1987, pp. 23–50; Fuess 2008, pp. 71–94; Chatty 2014, pp. 127–48). Although see Behrens-Abouseif (2023, p. 157) for a brief note that Mamluk female slaves did cover their faces. |

| 50 | The style resembles later examples of female headcoverings in the region (cf. Blass-Simmen 1991; cf. the thesis of Mladjan 2005). |

| 51 | Cf. (e.g., Weller 2019, pp. 58–59). Although not of this style, Rateb (2023, pp. 89–90) also discusses Venetian adoption of Mamluk styles. |

| 52 | For a recent edition, see (Von Breydenbach 2010); on Breydenbach’s views of Saracens, see (e.g., Boyle 2021). |

| 53 | The numbers are not well known; see (Ravid 2001, pp. 3–30). |

| 54 | Cf. Gilbert (1980, p. 38). See also Humfrey (1993, pp. 78, 259). For Patriarch Contarini’s commissioning of Carpaccio, see (Matino et al. 2020, p. 18). |

| 55 | He also brought together iconic details of the lives of the two saints in “St. George and the Dragon” (1516), commissioned by the Benedictine monastery and housed in the church of San Giorgio Maggiore. The 1520 Stoning of Saint Stephen (now in Stuttgart), which was commissioned for Santo Stefano, depicts the younger, Jewish Saul amid the crowd that is stoning the Christian saint. The 1516 work commissioned for the Benedictines featuring George slaying the dragon has, in the background, the older, Christian, Paul among the men in “eastern” garb who are stoning Stephen (Acts 22:20; cf. Acts 8:1–2). Following Sgarbi, the appearance of Stephen and George together might remind a Christian viewer to be vigilant—and steadfast in the true faith, which was under attack—from within (Jews now living in Venice) and without (encroaching Islam). For further discussion, see (Gentili 2023). See also (Morris 2015). |

References

- Andrea Contarini’s Tomb in the Cloister of the Church of Santo Stefano in Venice. n.d.Available online: https://www.venetoinside.com/en/news-and-curiosities/the-tomb-of-the-doge-andrea-contarini-church-of-santo-stefano-in-venice (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Arjana, Sophie. 2015. Muslims in the Western Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, Alison. 2021. Saint George as Cultural Unifier: Visual Clues in Carpaccio’s Cycle at the Scuola Dalmata in Venice. Confraternitas 32: 26–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, Alison. 2025. The Dissemination of Saint George in Early Modern Art. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, Laura, and Amanda Wunder. 2009. The Veiled Ladies of the Early Modern Spanish World: Seduction and Scandal in Seville, Madrid, and Lima. Hispanic Review 77: 97–144. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40541416 (accessed on 20 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. 2023. Dress and Dress Code in Medieval Cairo: A Mamluk Obsession. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Bisaha, Nancy. 2004. Creating East and West: Renaissance Humanists and the Ottoman Turks. Philadelphia: UPenn Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blass-Simmen, Brigit. 1991. Sankt Georg, Drachenkampf in der Renaissance: Carpaccio-Raffael-Leonardo. Berlin: Gebr. Mann-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Bowd, Stephen. 2016. Civic Piety and Patriotism: Patrician Humanists and Jews in Venice and its Empire. Renaissance Quarterly 69: 1257–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, Mary. 2021. Writing the Jerusalem Pilgrimage in the Late Middle Ages. Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer. [Google Scholar]

- Brann, Ross. 2009. The Moors? Medieval Encounters 15: 307–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brienen, Rebecca. 2014. Types and Stereotypes: Zwarte Piet and his Early Modern Sources. In Dutch Racism. Thamyris/Intersecting: Place, Sex & Race. Edited by Philomena Essed and Isabel Hoving. Leiden: Brill, Chapter 9. vol. 27, pp. 179–200. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, Caroline. 2004. Vittore Carpaccio’s Method of Composition in His Drawings for the Scuola Di S. Giorgio Teleri. Master Drawings 42: 303–14. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, Irene. 2024. Carpaccio and the Cultural Environment of Santo Stefano. In Vittore Carpaccio: Contesto, Iconografia, Fortuna (Atti di Convegno Internazionale di studi Venezia, Fondazione Giorgio Cini). Edited by Peter Humfrey and Gabriele Martino. Venice: Lineadacqua, pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Patricia Fortini. 1984. Painting and History in Renaissance Venice. Art History 7: 263–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Patricia Fortini. 1988. Venetian Narrative Painting in the Age of Carpaccio. New Haven: Yale U.P. [Google Scholar]

- Burghartz, Susanna. 2015. Covered Women? Veiling in Early Modern Europe. History Workshop Journal 80: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, Stefano. 2007. Moments of Vision: Venice and the Islamic world, 828–1797. Introduction to Brahim Alaoui et al. In Venice and the Islamic World, 828–1797. New Haven: Yale U.P., pp. 12–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cassen, Flora. 2013. From Iconic O to Yellow Hat: Anti-Jewish Distinctive Signs in Renaissance Italy. In Fashioning Jews: Clothing, Culture, and Commerce. Edited by Leonard Greenspoon. West Lafayette: Purdue U.P., Chapter 2. pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cassen, Flora. 2017. Marking the Jews in Renaissance Italy: Politics, Religion, and the Power of Symbols. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P. [Google Scholar]

- Chatty, Dawn. 2014. The Burqa Face Cover: An Aspect of Dress in Southeastern Arabia. In Languages of Dress in the Middle East. Edited by Bruce Ingham and Nancy Lindisfarne-Tapper. London: Routledge, pp. 127–48. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, Amy. 2022. Carpaccio Created the Graphic Novels of the Renaissance. Smithsonian Magazine. November/December. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/carpaccio-graphic-novels-renaissance-180981027/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- D’Andrea, David. 2005. The Power of Perception: Venice, the Early Reformation, and the Diarii of Marino Sanuto (1518–33). Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte-Archive for Reformation History 96: 6–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Puppo, Alessandro. 2009. Old Masters, New Stereotypes: Carpaccio as Pathway to Prendergast’s Venetian Scenes. In Prendergast in Italy. Edited by Nancy Mathews and Elizabeth Kennedy. London: Merrell, pp. 137–45. [Google Scholar]

- Del Puppo, Alessandro. 2012. Vittore Carpaccio. The Invention of a Painter in XIXth Century Europe. Paper presented at Annual Meeting of the Renaissance Society of America. The Long Shadow of the Venetian Cinquecento, Washington, DC, USA, March 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Finocchi Ghersi, Lorenzo. 2017. Vittore Carpaccio tra narrazione e devozione. Arte in Friuli, Arte a Trieste 36: 23–40, 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Földes, Anneliese, Johanna Pawis, Heike Stege, Eva Ortner, Andreas Schumacher, Jan Schmidt, Jens Wagner, and Andrea Obermeier. 2024. One Canvas, Four Ideas: A Double Portrait Attributed to Giorgione with Different Compositions Underneath. Artmatters International Journal of Technical Art History 9: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuess, Albrecht. 2008. Sultans with Horns: The Political Significance of Headgear in the Mamluk Empire. Mamlūk Studies Review 12: 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gentili, Augusto. 1988. Nuovi documenti e contesti per l’ultimo Carpaccio. II. I teleri per la scuola di San Stefano in Venezia. Artibus et Historiae 9: 79–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentili, Augusto. 2023. Convegno Internazionale di Studi “Vittore Carpaccio: Contesto, Iconografia, Fortuna, 14 June, at 8:40:00–8:43:34. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jQfCAEvoRZo (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Germain-De Franceschi, Anne-Sophie. 2010. Images de Terre sainte de Reuwich à Carpaccio: Évolution et lectures d’un stéréotype iconographique oriental entre 1486 et 1517. Seizième Siècle 6: 129–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Felix. 1980. The Pope, His Banker, and Venice. Boston: Harvard U.P., p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, Sidney. 2010. Disputing with Islam in Syriac: The Case of the Monk of Bêt Ḥālê and a Muslim Emir. Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 3: 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, Samuel. 2017. Venice: A Culture of Enclosure, a Culture of Control: The Creation of the Ghetto in the Context of the Early Cinquecento Ciiy. In The Ghetto in Global History. Edited by Wendy Goldman and Joe Trotter, Jr. Abingdon: Routledge, Chapter 4. pp. 74–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gudelj, Jusenka, and Tanja Trška. 2018. The Artistic Patronage of the Confraternities of Schiavoni/Illyrians in Venice and Rome. Proto-National Identity and the Visual Arts. Acta Historiae Artis Slovenica 23: 103–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, Chriscinda. 2023. The Convergence of Sacred and Secular in Vittore Carpaccio’s British Museum Concert. In Music and Visual Culture in Renaissance Italy. Edited by Chriscinda Henry and Tim Shephard. New York and London: Routledge, Chapter 11. pp. 223–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman-Ladd, Valerie. 1987. Polemics on the Modesty and Segregation of Women in Contemporary Egypt. International Journal of Middle East Studies 19: 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holter, Emma. 2023. Vittore Carpaccio: Master Storyteller of Renaissance Venice (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, November 20, 2022–February 23, 2023). Renaissance Studies 37: 583–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Diane. 1986. Distinguishing Signs: Ear–Rings, Jews and Franciscan Rhetoric in the Italian Renaissance City. Past & Present 112: 3–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humfrey, Peter. 1988. Competitive Devotions: The Venetian Scuole Piccole as Donors of Altarpieces in the Years around 1500. The Art Bulletin 70: 401–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humfrey, Peter. 1993. The Altarpiece in Renaissance Venice. New Haven: Yale U.P., pp. 78, 259. [Google Scholar]

- Irena, Ndreu. 2017. Albanian Cultural Representation in The City of Venice Through Albanian Painters in Italy. International Journal of Social and Educational Innovation (IJSEIro) 4: 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, David. 2017. The Production and Diffusion of Andalusi Silk and Silk Textiles, Mid-Eighth to Mid-Thirteenth Century. In The Chasuble of Thomas Becket: A Biography. Edited by Avinoam Shalem. Munich: Hirmer, pp. 142–51. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Ann. 2009. “Worn in Venice and throughout Italy”: The Impossible Present in Cesare Vecellio’s Costume Books. Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 39: 511–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Dana. 2008. The Jew in the Art of the Italian Renaissance. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knez, Kristjan. 2021. La Questione della Patria di Carpaccio: L’Origine Del Pittore tra Ipotesi, Polemiche e Discussioni Storiografiche. Santo: Rivista Francescana di Storia Dottrina Arte 61: 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lacouture, Fabien. 2012. Espace urbain et espace domestique: La Représentation des femmes dans la peinture vénitienne du XVIe siècle. Clio. Femmes, Genre, Histoire 36: 235–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landplagenbild on the Cathedral wall in Graz, Austria. 1480. Available online: https://squamcreativeservices.com/2015/07/landplagenbild-dom-graz-austria/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Lipton, Sara. 2014. Dark Mirror: The Medieval Origins of Anti-Jewish Iconography. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, Kate. 2013. Visible Lives: Black Gondoliers and Other Black Africans in Renaissance Venice. Renaissance Quarterly 66: 412–52, 444–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenney, Richard. 1994. Continuity and Change in the Scuole Piccole of Venice, c. 1250–c. 1600. Renaissance Studies 8: 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, David. 1984. Carpaccio, Saint Stephen, and the Topography of Jerusalem. The Art Bulletin 66: 610–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matino, Gabriele, Peter Humfrey, Paul Joannides, Catheline Périer-D’ieteren, Piers Baker-Bates, Diane Wolfthal, Barbara Pezzini, Cecilia Riva, and Will Elliott. 2020. ‘Et de presente habita ser Vetor Scarpaza depentor’: New Documents on Carpaccio’s House and Workshop at San Maurizio. Colnaghi Studies Journal 6: 8–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mazor, Amir. 2024. Social Mobility and Political Power: Turkification Processes in the Mamluk Sultanate. Mamlūk Studies Review 27: 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland, Jennifer. 2021. Ties That Unbind: Proximities, Pizzochere, and Women’s Social Options in Early Modern Venice. I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance 24: 241–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladjan, Milijana. 2005. Soldiers of Christ in the Schiavoni Confraternity: Towards a Visualization of the Dalmatian Diaspora in Renaissance Venice. Ottawa: National Library of Canada = Bibliothèque Nationale du Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Roderick Conway. 2015. Puncturing the myth of Carpaccio’s waning powers. The New York Times. June 17. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/18/arts/international/puncturing-the-myth-of-carpaccios-waning-powers.html (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Nichols, Tom. 2007. Secular Charity, Sacred Poverty: Picturing the Poor in Renaissance Venice. Art History 30: 139–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirenberg, David. 2015. Communities of Violence: Persecution of Minorities in the Middle Ages, updated ed. Princeton: Princeton U.P. [Google Scholar]

- Okey, Thomas. 1907. The Old Venetian Palaces and Old Venetian Folk. New York and London: Dent/Dutton. [Google Scholar]

- Pastoureau, Michel. 2001. The Devil’s Cloth: A History of Stripes and Striped Fabric. New York: Columbia U.P. [Google Scholar]

- Pixley, Mary. 2003. Islamic Artifacts and Cultural Currents in the Art of Carpaccio. Apollo 158: 9p. Available online: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A110735910/AONE?u=learn&sid=googleScholar&xid=0f3e21fc (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Pullan, Brian. 2004. Charity and Usury: Jewish and Christian Lending in Renaissance and Early Modern Italy. Proceedings of the British Academy 125: 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta, Elena. 2018. Parish and Monastic. Churches: Civic Custom and the Quotidian in the System of International Patronage. In A Companion to Music in Sixteenth-Century Venice. Vol. 2 of Brill’s Companions to the Musical Culture of Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Edited by Katelijne Schiltz. Leiden: Brill, Chapter 3. pp. 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, Yossef. 2007. Women and Gender in Mamluk Society: An Overview. Mamlūk Studies Review 11: 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rateb, Nevine. 2023. Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria: A New Perspective. Mamlūk Studies Review 26: 71–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ravid, Benjamin. 1992. From Yellow to Red: On the Distinguishing Head-Covering of the Jews of Venice. Jewish History 6: 179–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravid, Benjamin. 2001. The Venetian Government and the Jews. In The Jews of Early Modern Venice. Edited by Robert Davis and Benjamin Ravid. Baltimore: John Hopkins U.P., Chapter 1. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ravid, Benjamin. 2023. Studies on the Jews of Venice, 1382–1797. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Reames, Sherry. 1985. The Legenda Aurea: A Reexamination of Its Paradoxical History. Madison: U. of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodini, Elizabeth. 2011. The Sultan’s True Face? Gentile Bellini, Mehmet II, and the Values of Verisimilitude. In The Turk and Islam in the Western Eye, 1450–1750: Visual Imagery before Orientalism. Edited by James Harper. London: Ashgate Publishing, Chapter Two. pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Peinado, Laura, and Ana Cabrera-Lafuente. 2020. New Approaches in Mediterranean Textile Studies: Andalusí Textiles as Case Study. In The Hidden Life of Textiles in the Medieval and Early Modern Mediterranean: Contexts and Cross-Cultural Encounters in the Islamic, Latinate and Eastern Christian Worlds. Edited by Nikolaos Vryzidis. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rospocher, Massimo, and Enrico Valseriati. 2025. Politics in the Street: The Materiality of Urban Public Spaces in Renaissance Italy. Urban History 52: 38–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Elizabeth. 2007. Mainz at the Crossroads of Utrecht and Venice: Erhard Reuwich and the Peregrinatio in terram sanctam (1486). In Cultural Exchange between the Low Countries and Italy (1400–1600). Edited by Ingrid Alexander-Skipnes. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 123–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Elizabeth. 2014. Picturing Experience in the Early Printed Book: Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio from Venice to Jerusalem. University Park: Penn State Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rota, Giorgio. 2009. Under Two Lions. On the Knowledge of Persia in the Republic of Venice (ca. 1450–1797). Vienna: Verlag der Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaft, p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, Miri. 2014. Ecclesia and Synagoga: The Changing Meanings of a Powerful Pairing. In Conflict and Religious Conversation in Latin Christendom: Studies in Honour of Ora Limor. Edited by Israel Yuval and Ram Ben-Shalom. Turnhout: Brepols, Chapter 3. pp. 55–86. [Google Scholar]

- Rusconi, Roberto. 2004. Anti-Jewish Preaching in the Fifteenth Century and Images of Preachers in italian Renaissance Art. In The Friars and Jews in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Edited by Susan Myers and Steven MacMichael. Leiden: Brill, Chapter 12. pp. 225–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sanudo, Marin. 2008. Cita Excellentissima: Selections from the Renaissance Diaries of Marin Sanudo. Edited by Patricia Labalme and Laura Sanguineti White. Translated by Linda Carroll. Baltimore: JHU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Daniel. 2019. Ghetto: The History of a Word. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Segre, Renata. 2025. Prelude to the Ghetto: Did Venice Favor the “Italian Way”? In Jews and State Building: Early Modern Italy and Beyond. Edited by Bernard Cooperman, Serena Di Nepi and Germano Maifreda. Leiden: Brill, Chapter 6. pp. 112–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sgarbi, Vittorio. 2015. Carpaccio. Milan: RCS Libri. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, Patricia. 2023. The Black Female Attendant in Titian’s Diana and Actaeon (c. 1559), and in Modern Oblivion. In Teaching Race in the European Renaissance: A Classroom Guide. Montreal: Pressbooks, pp. 223–46. Available online: https://asu.pressbooks.pub/race-in-the-european-renaissance-classroom-guide/chapter/the-black-female-attendant-in-titians-diana-and-actaeon-and-in-modern-oblivion/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Stillman, Yedida. 1976. The Importance of the Cairo Geniza Manuscripts for the History of Medieval Female Attire. International Journal of Middle East Studies 7: 579–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoichita, Victor I. 2019. Darker Shades: The Racial Other in Early Modern Art. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Stošić, Ljiljana. 2017. Stripes Between the Sacred and the Profane. Sociology and Anthropology 5: 1033–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Strunck, Christina. 2011. The Barbarous and Noble Enemy: Pictorial Representations of the Battle of Lepanto. In The Turk and Islam in the Western Eye 1450–1750: Visual Imagery Before Orientalism. Edited by James Harper. Surrey: Ashgate, Chapter 9. pp. 217–40. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Tassini, Giuseppe. 1879. Alcuni palazzi Ed Antichi Edificii di Venezia: Storicamente illustrati. Venice: Tipografia M. Fontana. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- The Churches of Venice. n.d.Available online: http://churchesofvenice.com/scuole.htm#calegheri (accessed on 20 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Tolan, John. 2002. Saracens: Islam in the Medieval European Imagination. New York: Columbia U.P. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Tomasella, Giuliana. 2020. Art and Colonialism: The ‘Overseas Lands’ in the History of Italian Painting (1934–1940). Predella. Journal of Visual Arts 48: 165–87. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Two Standing Women, One in Mamluk Dress. n.d.Available online: https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/4802 (accessed on 20 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Von Breydenbach, Bernhard. 2010. Peregrinatio in terram sanctam: Eine Pilgerreise ins Heilige Land. Frühneuhochdeutscher Text und Übersetzung. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/338300 (accessed on 20 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Weller, Thomas. 2019. He Knows Them by their Dress: Dress and Otherness in Early Modern Spain. In Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe. Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein and Thomas Weller. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 52–72. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Whistler, Catherine. 2018. Vittore Carpaccio (1460/1466?–1525/1526), an Innovative Draughtsman. Colnaghi Studies 3: 80–87. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Yalman, Suzan. 2001. The Art of the Mamluk Period (1250–1517). Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. October 1. Available online: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/maml/hd_maml.htm (accessed on 24 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Yarmo, Leslie. 2016. From Dye to Identity: Linking Saffron to Stigmatizing Jewish Dress Codes and the Paradox of a Yellow-Robed Moses in the Sistine Chapel. International Journal of Arts Theory & History 11: 19–31. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).