The Angel, the Demon, and the Priest: Performing the Eucharist in Late Medieval Moldavian Monastic Written and Visual Cultures

Abstract

1. Looking for Textual Sources

2. A Rare Visionary Text Copied in Late Medieval Moldavia

[…] when the priest comes to the church to sing the divine liturgy, the angel greets him at the gates of the church and cleanses him of all his sins. And when the priest enters the church, he is as bright as the morning star. And when […] he puts on the sticharion, the angel of the Lord crowns him. And when he puts on the epitrachelion, the angel pours perfumed oil on his head. When he puts on the cincture, he girds himself with the blood of God. And when he puts on his outer garment [sc. the felon], a sunny crown descends upon his head. And when he says, “In remembrance of our Lord Jesus Christ,” the angel bows down to him. And when the priest cuts the Lamb, I saw a little child sacrificed [emphasis mine, it represents an anticipation of the second section of the text]. And when he places the ribs [sic, scil. the asterisk], a bright star descends and stands above that child. And the devil distracts the people outside, so that they do not come to church. And when [the priest] places the covers, the angel covers the child with his wings. And when the priest receives the branch (the sponge?) [sic, recte the censer], the devil flees from the church. And when the deacon says, “Bless, Lord,” the angel lifts the roof of the church; and again, the angel returns to the church. And when [the priest] says, “It is good to confess to the Lord” [Ps. 91/92:1], the angel leads the people who are standing properly in prayer; and the devil flees and receives the people who do not listen to the singing, and says to them, “I am with you.” And when he says, “The Lord reigns” [Ps. 92/93:1], the Holy Spirit covers the people who stand with true faith in the church; but the devil calls those who do not listen outside the church with his arms wide open and says to them, “Come, my guests, do not listen to the songs there.” And when he says, “Come, let us rejoice in the Lord” [Ps. 94/95:1], the devil brings despair upon the people, so that they do not listen to the songs; the angel of the Lord crowns the righteous. And when the priest says, “That they may praise with us,” then the devil lets the people return to the church. And when the priest says, “Those who are called [leave],” then the angel of the Lord throws the bones of the unbelievers out of the grave; but to the righteous he says, “Rejoice with us, for with us there will be honor in heaven.” [cf. Mt. 5:12] And when the Cherubic Hymn is sung, the angels invisibly carry the gifts; and to the righteous they say, “Come, you who are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you in heaven” [Mt. 25:34]. But the devil cries out in anguish, “Do not forget me, the old comforter.” And when the priest says, “Have mercy on us, O Lord, according to your great mercy [sic], then the devil incenses the unbelievers with his censer. And when the priest says, “Perfect angel,” then the angel of the Lord drives away the devil. And when the priest says, “Let us stand well, let us stand in fear,” then the devil whispers in the ears of the unbelievers, so that they cannot hear the songs. And when the priest says, “Singing the triumphal hymn,” the angel of the Lord receives those who stand as they should. And when the priest says, “Take, eat” [Mt. 26:26], the angel of the Lord gives communion to those who stand as they should in the church.4

[…] I saw the heavens open and fire descending, with a multitude of angels. And above them were two figures of great beauty, whose glory I am not so phony as to tell, for their light was like lightning; and between the two faces [was] a little child. And the angels stood by the holy table, and the two figures on the holy table, the child [being] still between them. And when the divine books were finished [scil. at the end of the Liturgy of the Word], the deacons approached the clergy to break the bread of the offering; I saw the two figures, who were on the holy table, untying the hands and feet of the child who was on it, and they took the knife and stabbed the child, and his blood flowed into the chalice that was on the holy table. And they crushed his body and placed it on the bread, and the bread became flesh. Then I remembered the apostle who says, “For Christ, our Passover, has been sacrificed for us” [1 Cor 5:7]. And when the brothers approached to receive the holy bread, they were given the body, and because they invoked saying, “Amen,” it became bread in their hands. And I, when I went to receive it, was given the body, and I could not receive it. And I heard a voice in my ears saying to me, “Man, why do you not take communion? Is this not what you desired?” I said, “Be merciful to me, Lord, for I cannot receive the body.” And he spoke to me again, “If man could receive the body, the body itself would be revealed to him as it is revealed to you. But no one can receive the body. That is why God commanded that the offering of bread be made. For in the beginning, Adam was formed from the hands of God, and the breath of life was breathed into him from outside; and the body was formed from the earth, but the spirit was already in it. So now Christ, with the Holy Spirit, with whom he shows mercy to man. For the spirit dwells in the heart, so that if you have faith, you may partake of what you hold in your hands.” And if I said, “I believe, Lord,” when I said that, the body I held in my hands became bread. I praised God and took the holy prosphora.5

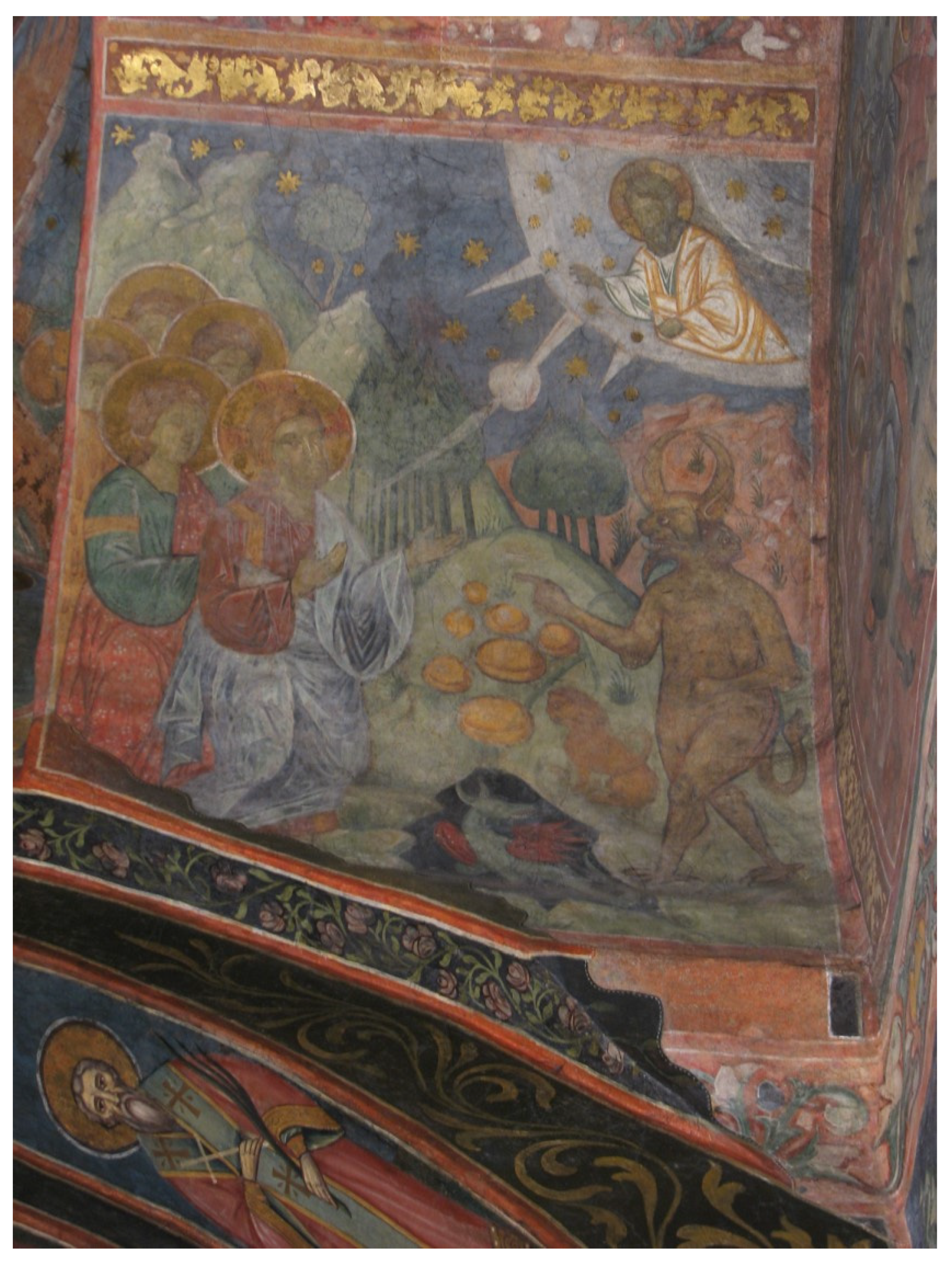

3. Visual Counterparts to the Visionary Text

4. Liturgical Information Offered by the Visionary Text

5. Performative Readings of Images Mediated by the Visionary Text

6. Visionary vs. Mystagogic Character

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| л҇з. cлѡ кaкo пoⷣбae cтoaти въ цpк҇ѡ | 37. Discourse on the appropriate manner of standing in the church (begins on the last page of fascicle 11) |

| 83v и пaкы cлышитe бpaтїa мoa възлю- блeнaa· мaлїи и вeлицїи· cлѡвo кaкo пoⷣбaeть cтoaти въ цpк҇oвь гн҇ѧ· въ вpѣмѧ пѣнїѧ пoⷣбaeть cтoaти cъ 15 cтpaxѡⷨ и cъ тpeпeтѡⷨ· ꙗкoⷤ eгдa пpи- xoдить cщ҇eнникь въ цp҇кoвь· дa пo- eть бжтвнaa лиpгїa· cpѣтaeть eгo aгг҇ль нa вpaтⷯѣ цp҇кoвнⷯѣ· и ѡчиcти eгo ѿ въcⷯѣ гpⷯѣ eгo· и eгдa вълaꙁи 20 cщ҇eнникь въ цp҇кѡ cвѣтeль e ꙗкo | Listen, therefore, my beloved brothers, small and great, to the word about how it is proper to stand in the church of God. At the time of singing, it is fitting to stand with fear and trembling. For when the priest comes to the church to sing the divine liturgy, the angel meets him at the gates of the church and cleanses him of all his sins. And when the priest enters the church, he is as bright as the morning star. |

| 84r дeницa· и eгдa пocтaвлѣeⷨ19 oдѣaнїe cвoѫ дoлнѫ· и ѡблaчить cтиxapь, тѡ- гⷣa aгг҇ль гн҇ь вѣнчaeть eгo· и eгдa пo- cтaвлѣeть питpиaxиль· тoгдa мѷ- 5 po бл҇гoѧxaннoe въꙁлївaeть нa глaвѣ eгo· eгдa пpѣпoacoyeт cѧ тoгⷣa кpъ- вїѫ бж҇їeѫ пpѣпoacoyeт cѧ· и eгдa пo- cтaвлѣeть гopнѫѧ pиꙁѫ· тoгдa cлъ- нeчнїи вѣнeць cънидe нa глaвѫ eгo· 10 и eгдa peчe въcпoминaнїe г҇a б҇a и cпc҇a нaшeгo i҇v x҇a· тoгⷣa aг҇гль клaнѣѧ cѧ eмoy· и eгдa pѧжe iepeи aгнeць· тo- гⷣa видⷯѣ ѡтpoчѧ млaдo ꙁaкaлaeмo· и eгдa пocтaвлѣeть peбpьницѫ· тo- 15 гдa cвѣтлaa sвѣꙁⷣa cънидe и cтaeть нⷣa ѡтpoчѧ тeⷨ· a дїaвѡ вънeѧдoy ꙁa- бaвлѣeть людeмь· дa нe пpиxoдѧть въ цp҇кѡ· и eгдa пoкpывaeть пoкpo- вци· тoгдa aгг҇ль кpилaмa пoкpыeть 20 ѡтpѡчѧ· и eгдa cщ҇eнни пpїeмлѧть | And when he puts on his undergarment and dresses in the sticharion, then the angel of the Lord crowns him20. And when he puts on his epitrachelion, the angel pours perfumed oil on his head21; when he puts on his belt, he girds his waist with the blood of God22. And when he puts on his outer garment, a crown of glory descends upon his head23. And when he says, “In remembrance of the Lord our God Jesus Christ,” the angel bows down to him24. And when the priest cuts the lamb, then I saw a little child sacrificed. And when he places the ribs [sic]25, a bright star descends and stands above that child26. And the devil distracts the people outside, so that they do not come to church. And when [the priest] places the coverings [for the vessels], the angel covers the child with his wings. And when the priest receives the twig (the sponge? the censer?)27 |

| 84v мeтлицѫ28· тoгⷣa дїaвѡ бѣгaeть иꙁь цpк҇ви· и eгдa peчeть дїaкѡ блви влa- дыкo· тoгдa aгг҇ль въꙁимaeть пѡ- кpѡ цpк҇oвныи· и пaкы въꙁвpaщae 5 cѧ aгг҇ль въ цpкѡ· и eгдa peчeть бл҇гo eи иcпoвѣдaти cѧ гв҇и· тoгдa aгг҇ль въ вoди людїи· ижe пpaвo cтoѫ нa мл҇и- твѣ· и дїaвoль ѿбѣгaeть· и пpїeмлѧ люди eжe нeпocлoyшaeть пѣнїa, и г҇лe 10 имь aꙁь ecмь cъ вaми· eгⷣa peть г҇ь въ/ цp҇и cѧ· тoгⷣa дx҇ь cт҇ыи пoкpывaeть лю- ди пpaвoвѣpнo cтoѫщиⷯ въ цpк҇ви· a҇ дїaвoль ꙁoвeть нeпocлoyшaѫщиⷯ иꙁь цpк҇бe, pѫцѣ pacпpocтиpaѫщe, и гл҇гo- 15 лѣщe къ нимь· гpѧдѣтe гocтїa мoꙵ нeпocлoyшaитe тaмo пѣнїa· и eгⷣa peчe пpидѣтe въꙁpaⷣvим cѧ гв҇и· тoгⷣa дїaвѡ ѿчaвaeть люⷣ дa нe чюe пѣнїa· aгг҇ль гн҇ь вѣнчaвaeть люди пpaвoвѣ- 20 pныѧ· и eгдa peть cщ҇eнникь дa и ти | the devil flees from the church. And when the deacon says, “Bless, master,”29 the angel lifts the roof of the church; and again, the angel returns to the church. And when [the priest] says, “It is good to confess to the Lord”30 [Ps. 91:1]), the angel leads the people who are standing properly in prayer; and the devil flees and receives those who do not listen to the song, and says to them, “I am with you.” And when he [scil. the priest] says, “The Lord has reigned”31 [Ps. 92:1], then the Holy Spirit covers those who stand with true faith in the church; but the devil calls those who do not listen outside the church, with his arms wide open, and says to them, “Come, my guests, do not listen to the songs there.” And when he [scil. the priest] says, “Come, let us rejoice in the Lord”32 [Ps. 94:1], then the devil brings despair upon people, so that they do not listen to the songs; the angel of the Lord crowns the righteous. And when the priest says, “So that they |

| 85r cъ нaми cлaвѧ· тoгⷣa дїaвѡ пoyщae люди въꙁвpaщaeть cѧ въ цp҇кѡвь· и eгⷣa peть cщeнни eлици ѡглaшeни тoгдa aгг҇ль гн҇ь кocти нeвѣpныⷨ людeⷨ 5 иꙁ гpoбa иꙁмeщae· a҇ пpaвeⷣнїимь г҇лe paⷣvитe cѧ вы пpaвeⷣнїи cъ нaми· ꙗкo бo имaтe чьcть (cъ) нaми нa нб҇ceⷯ· и eгдa въ- cпeшe xepoyвикoy· тoгⷣa aгг҇ли нeви- димo нocѧ дapы· a҇ пpaвeⷣныиⷨ гл҇eть· 10 пpїидѣтe блвeнїи ѡц҇a мoeгo· нacлѣ- дoyитe oyгoтoвaнoe вaⷨ цpтвo нбнoe· a҇ дїaвѡ ѡбыдeнь въпїe нe ꙁaбивaитe мeнe cтapoгo oyтѣшитeлѣ· и eгдa peчe cщ҇eнникь· пoмл҇oyи нa б҇e пo вeли- 15 цѣи млти твoeи· тoгдa дїaвoль cвo- eѧ кaдилницeѫ кaдить нeвѣpнїѧ люⷣ· и eгдa peчe cщe҇нникь· aггл҇a cъвpъ- шe·33тoгⷣa aгг҇ль г҇нь дїaвoлa ѿгoнить· и eгдa peчe cщe҇нникь· cтaнⷨѣ дoбpⷨѣ {sic} 20 cтaнeⷨ cъ cтpaxѡⷨ· тoгдa дїaвѡ шeтe· | may also glorify with us 34, then the devil lets the people return to the church. And when the priest says, “Those who are called,”35 the angel of the Lord throws the bones of the unbelievers out of the pit; but to the righteous he says, “Rejoice with us, for with us there will be honor in heaven” [cf. Mt. 5:12]. And when the Cherubic Hymn is sung, the angels invisibly carry the gifts; and to the righteous they say, “Come, you who are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you in heaven” [Mt. 25:34]. But the devil cries out in anger, “Do not forget me, the old comforter.” And when the priest says, “Have mercy on us, O Lord, according to your great mercy”36, then the devil incenses the unbelievers with his censer. And when the priest says, “Perfect angel” {sic}37, the angel of the Lord drives away the devil. And when the priest says, “Let us stand well, let us stand in awe”38 the devil whispers |

| 85v людeⷨ нeвѣpныиⷨ въ oyxo· дa нe нe39чюe пѣнїa· и eгдa peчeть cщe҇нникь пoбⷣѣ- нѫѧ пѣ пoѫщe· тoгⷣa aгг҇ль гн҇ь пpїe- млe люди пpaвocтoѫщeи· и eгдa peчe 5 cщe҇нникь пpїмѣтe ꙗдитe· тoгⷣa aгг҇ль гн҇ь пpичѧщaeть люди пpaвo- cтoѫщиⷯ въ цp҇кoвь. Ceгo paди бpa- тїa мoa въꙁлюблeнaa· eгдa e вpѣмѧ пѣнїaмь въ цp҇кoвь· ты дa cтoиши 10 cъ cтpaxѡⷨ бж҇їeмь и cъ вѣpoѫ· ꙁpи бpaтe ижe cтoить cъ вѣpoѫ кoликo чьcть имa ѿ б҇a и ѿ aгг҇ль· и пaкы ижe нe cъ вѣpoѫ cтoѫщe· видиши люби- мичe кaкo пopѫгaнь e ѿ дїaвoлa· и пa- 15 кы eгⷣa xoщeши пpичѧcтити cѧ· a҇ ты нe лѣниши нѫ cъ дpъꙁнoвeнїe и cъ cтpaxѡⷨ бж҇їeмь· дa пpиxoдиши къ cт҇aa пpичaщeнїa· и дa нe мни тeбѣ ꙗкo пpocтa xлѣбь и винo· нѫ въ(ни)мaи 20 cтг҇o eφpaмa40 гл҇щa· бывшoy pe cъбopь | in the ears of unbelievers, so that they may not hear the songs. And when the priest says, “Singing the triumphal hymn,”41 the angel receives those who stand as they should. And when the priest says, “Take, eat” [Mt. 26:26] the angel of the Lord gives communion to those who stand as they should in the church. Therefore, my beloved brothers, when it is time for singing in church, stand with fear of God and with faith; see, brother, how much honor those who stand with faith receive from God and from the angel, and see, dear one, how much the devil mocks those who do not stand with faith. Moreover, when you want to receive communion, do not be lazy, but approach the holy communion with boldness and fear of God. And do not think that it is only bread and wine, but listen to St. Ephram [sic] who says: There was, he tells, a liturgy |

| 86r въ нeⷣлѧ· и въcтa бpa нѣкoи· пo ѡбычaю вънити въ цp҇кoбь· пoмoлити и пpи- чaщaти cѧ· и пopѫгa cѧ eмꙋ дїaвѡ гл҇ѧ къ нeмoy въ пoмыcль· кaмo идe- 5 ши въ цp҇кoвь дa имeши xлѣбь и винo ꙗкo тѣлo и кpьвь xв҇ѫ· нe пpилъщaи cѧ бpaт жe имы вѣpѫ пoмыcлꙋ· и нe идe въ цp҇кѡ пo ѡбычaю· бpaтїи жe жⷣѫщи eгo· ꙗкo тaкo e oбычaю пoycтини 10 тoѫ· дa нe cътвopѧ cъбopa cлoyбa peкшe млт҇вы дoндeжe пpїидѫть въcи· и oжидaѫщиⷨ жe eгo пo мнosѧ· и o- нoмoy нe пpишeⷣшoy· нѣцї ижe ѿ бpa- тїa въcтaвшe и пpїидoшѫ въ кeлїѧ 15 eгo· и въпpaшaxѫ и҇ пoчтo нe пpїидe въ cъбopь бpaтe· ѡн жe cтидѧшѧ cѧ пoвѣдaти имь· ѡни жe paꙁoyмѧв жe ꙗкo дїaвoлꙋ cъвѣ e· и пaдoшѫ къ нeмⷹ бpaтїa cъ oyмилeнїeⷨ· дa ниⷨ cпoвѣ дїaвѡ- 20 лoy cъвѣ· ѡн жe иcпoвѣдa иⷨ гл҇ѧ· пpo- | on a Sunday, and a certain brother rose to enter the church, as was his custom, to pray and receive communion; and the devil mocked him, speaking to him in his mind, “Where are you going? To church, to receive bread and wine as the body and blood of Christ? Do not deceive yourself!” And the brother believed this thought and did not go to the service as usual. However, the brothers waited for him, because it was the custom of that hermitage not to begin the service, that is, the prayers, until everyone had arrived. And they waited for him for a long time, and because he did not come, some of the brothers got up and went to his cell. And they asked him, “Why did you not come to the service, brother?” He was ashamed to tell them. And they understood that it was the devil’s advice, and the brothers knelt before him in humility, so that he might confess the devil’s advice. He confessed to them, saying: |

| 86v cтитe мѧ бpaтїa мoa· ꙗкo въcтaⷯ пo ѡбичaю въ цp҇кoвь ити· pe ми пo- мыcль· нѣ тѣлo и кpьвь xв҇a· кaмo идeши пpїѧти xлѣбa пpocтa и винa 5 и aщe xoщeтe дa пpїидѫ cъ вaми· oy- твpъдитe ми пoмыcль ѡ҇ cт҇ѣи пpo- cφopѧ· ѡни жe peкoшѫ въcтaн и гpѧ- ди cъ нaми· и пoмл҇и cѧ бв҇и· дa ти пo- кaжe тaинѫ и cилѫ cъxoдимѫ· и въ- 10 cтaвь пpїидe cъ ними въ цp҇кoвь и cъ- твopишѫ мл҇твѫ къ бo҇y ѡ бpaтѧ· дa ꙗвить eмoy бжтвныⷯ тaинь cилѫ· тaкo нaчѧшѫ cъвpъшaти cъбѡpь· peкшa млт҇вѫ· пocтaвившe бpaтa 15 пo cpⷣѣ цp҇квe· и дo ѿпoyщeнїa cъбopꙋ нeпpѣcтa cъ cльꙁaми ѡмывaѫ лицa cвoeгo· пo cъбope жe peкшe пo ѿпꙋ- щeни мл҇тьвнⷨѣ· пpиꙁвaвшe жe ѡц҇и бpa- тa· въпpaшaaxѫ и҇ гл҇щe· eжe ти пoкaꙁaль 20 б҇ь пoвѣжⷣь нaⷨ· дa и мы пoлsoyeмь· | “Forgive me, brothers! When I got up to go to church as usual, a thought came to me: ‘It is not the body and blood of Christ! Where are you going? To receive only bread and wine?’ And if you want me to come with you, strengthen my faith in the holy prosphora.” They said, “Get up and come with us, and pray to God that He may reveal to you the mystery and power that has descended upon you!” And rising, he entered the church with them. And they prayed to God for the brother, that the secret power of God might be revealed to him. So they began to perform the service, that is, the prayer, and the brother was placed in the middle of the church, and until the end of the service, tears flowed unceasingly down his face. And after the service, that is, after the prayers were finished, the fathers called him and asked him, saying, “Tell us what God has shown you, so that we may also benefit.” |

| 87r oн жe cъ плaчeⷨ нaчѧ глa҇ти· и eгдa pe бы пpaвилo пѣннoe· и пpoчьтeннo бы aпльcкoe oyчeнїe· cтa дїaкoнь чѧcти cтo҇e evлїe· тoгдa видⷯѣ пoкpoвь нeбe- 5 cныи ѿвpьcть нбa ꙗвлѣѫщa cѧ· и кoeгoжⷣo cлoвo evлcкoe· ꙗкo ѡгнь бы· и ꙗвлѣaшѧ дo нбe· ꙗкo жe бы evлcкoe cкoнчaнїe· пpѣди пoидoшѫ клиpици ѿ дїaкoнa· имѧщe бжть 10 внⷯы тaинь пpичѧcтїe и видⷯѣ нб҇ca ѿвpъcтa· и ѡгнь cъxoдѧщь cъ мнo- жьcтвoⷨ aгг҇ль· и вpъxꙋ иxь инѣ двѣ ли- ци sѣлo кpacнѣишa· eѫжe нѣ лицe- мѣpcтвo иcпoвѣдaти дoбpoты· бѣ 15 бo cвѣ eю ꙗкo млънїи· и пo cpⷣѣ42лицoy мaлo ѡтpoчѧ· и aгг҇ли жe cтoaшe o кpть cт҇ыѫ тpaпeꙁы· лици жe двѣ вpъxoy cт҇ыѧ тpaпeꙁы· ѡтpoчa тиⷤ пo cpⷣѣ eю· и ꙗкⷤo бы кoнчaнїe бжтвныⷯ книгь· 20 пpиближишѧ дїaкoни ѿ клиpoca· | And he began to weep and spoke: “When it was,” he told, “the chanted service,43 and the apostolic teaching was read, the deacon stood with the holy gospel; I saw the covering of the heavens lifted up, the heavens appearing; and every word of the Gospel was like fire, and [the fire] appeared up to the sky. And when the Gospel was finished, the clergy came forward from the diaconicon [?] with the communion of the divine mysteries, and I saw the heavens opened and fire descending, with a multitude of angels. And above them were two figures of great beauty, whose glory I cannot describe, for their light was like lightning; and between (the two) faces [was] a little child. And the angels stood beside the cross of the holy table, and the two figures [stood] on the holy table, the child [being] between them. And when the divine books were finished, the deacons approached the clergy |

| 87v пpѣлoмити xлѣбa пpⷣѣлoжeнїa· ви- дⷯѣ двѣ лици· eжe бѣcтѣ вpъxoy cт҇ыѧ тpaпeꙁы· и cвeꙁaвшe pѫцѣ и нosѣ ѡтpoчѧти eжe бѣ вpъxoy eгo· имѧ- 5 cтa нoⷤ и ꙁaклacтa ѡтpoчѧти {sic}· и иꙁлїa cѧ кpьвь eгo въ чaшѫ· ꙗжe бѣ вpьxꙋ cт҇ыѧ тpaпeꙁы· и cъдpoбившe тѣлo eгo· и пoлoжиcтe вpъxꙋ xлѣбь· и бы xлѣбь въ тѣлo· тoгⷣa пoмѣнѫⷯ aплa 10 глщ҇a· и бo пaxa нaшѫ ꙁa ни жpѣнь бы x҇c· и ꙗкoⷤ пpиближишѫ cѧ бpaтїa, пpи- ѧти cт҇ыѧ пpocφopы· дaaшѫ иⷨ тѣлo и ꙗкoⷤ пpиꙁывaaxѫ гл҇ѧщe aминь· бѫдeшe xлѣбь въ pѫкaⷯ иxь· и aꙁь ꙗкoⷤ 15 пpїидѡⷯ пpїѧти дaⷭ ми cѧ тѣлo· и нe мoжaⷯ eгo пpїѧти· и cлышaⷯ глa въ oy- шїю мoeю гл҇ѧщe ми· члч҇e, чьco paди нe пpїeмлeши· нe ли ce· eгoⷤ иcкa· и pⷯѣ млтив (м)и бѫди г҇и· ꙗкo тѣлo нe 20 мoгѫ пpїѧти· и пaкы pe ми· aщe би | to break the bread of the offering; I saw the two figures, who were on the holy table, untying the hands and feet of the child who was on it, and they took the knife and stabbed the child, and his blood flowed into the chalice that was on the holy table. And they crushed his body and placed it on the bread, and the bread became flesh. Then I remembered the apostle who says, “For our Passover, Christ, was sacrificed for us” [1 Cor 5:7]. And when the brothers approached to receive the holy bread, they were given the body, and because they invoked saying, “Amen,” it became bread in their hands. And when I went to receive it, I was given the body, and I could not receive it. And I heard a voice in my ears saying to me, “Man, why do you not take communion? Is this not what you desired?” I said, “Be merciful to me, Lord, for I am not worthy to receive you.” And again, he said to me, “If it would have been possible |

| 88r мoгль чл҇кь тѣлѡ пpїѧти· тѣлo ceбe ѡ- бpѣтaлo· ꙗкo жe ты ѡбpѣтe· нѫ ни- ктoжe мoжe тѣлa пpїимaти· ceгo pa б҇ъ пoвeлѣ быти xлѣбѡ пpѣлoжeнїa 5 ꙗкoжe бo иcпpьвa aдaмь· pѫкaмa б҇їи- мa бы плъ· и въдoyнѫ вънь дx҇a живo- тeнь· и плъ ѡлѫчи cѧ въ ꙁeмлѧ· и дx҇ь жe пpѣбы въ нe· и нн҇ѣ x҇c cъ cт҇ыи дx҇ѡмь· имжe млpдꙋeть чл҇кы· дx҇ь жe 10 cтoить въ cpци дa aщe вѣpꙋeш пpїими eжe имaши въ pѫкꙋ· и ꙗкo pⷯѣ вѣpoyѫ г҇и· cи ми peкшoy бы тѣлѡ eжe въ pѫкoy мoeю xлѣбь· пoxвaливь б҇a и пpиѧxь cт҇ѫѧ пpocφopa· и eгa жe 15 cъбopь oycпѣ· пpїидoшѫ клиpици въ- кoyпь· видⷯѣ пaкы ѡтpoчѧ пo cpѣ двoю лицꙋ· и клиpикы cътpѣблѣѫ- щa дapы· видѣxь пoкpoвь цpo҇вныи ѿвpъcть· и бжтвныѧ cилы въꙁнocѧ 20 щa cѧ нa нб҇o· и ѡтpoчѧ пo cpѣ лицoy | that man receives the flesh, the flesh itself would appear to him as it appears to you. But no one can receive the flesh. That is why God commanded the offering of bread. Just as, in the beginning, Adam was formed from the hands of God and breathed the breath of life from outside; and the body was formed from the earth, but the spirit already existed in it; So now Christ with the Holy Spirit, with whom he shows mercy to man. For the spirit dwells in the heart, so that if you have faith, you may partake of what you have in your hands.” And when I said, “I believe, Lord,” as I said this, the body that was in my hands became bread. I praised God and took the holy prosphora. And then the service came to an end. The clergy approached together. I saw the child again in the middle of the two figures. And when the clergyman consumed the gifts, I saw the roof of the church raised, and the heavenly powers rose up to heaven; and the child was between the figures. |

| 88v cы cлышaвшe бpaтїa мнoгo oyми- лeнїe пpїeмшe· и ѿидoшѫ въ кeлїѫ cвoѫ въ cвaвѫ бo҇y ѡцo҇y aми. | Hearing this, the brothers were filled with great humility, and they went to their cells, glorifying God the Father, amen. |

| 1 | The term “periphery” is not used in a pejorative sense (see Eastmond 2008), but to establish the relationship between the Byzantine cultural model and its strategic adoption, sometimes in a polemical spirit, always with identity implications, in the so-called Byzantine “Commonwealth” (Obolensky 1974; for the colonialist implication of this term, see Anderson and Ivanova 2023, pp. 8–9). The nature of Moldavia’s relations with Byzantium in the fifteenth century has been a subject of dispute among researchers, oscillating between the hypothesis of unmediated relations (Turdeanu 1942) and that of indirect relations mediated by the Balkan Slavic cultures (Elian 1964). Romanian art historiography embraced the strategy of comparing the corpus of locally produced wall paintings with late Byzantine artistic production in the Balkans and in the Russian space, usually by resorting to stylistic analyses. Emil Dragnev has recently proposed a possible role of Moldova in the transmission of iconographic models between the Balkans and the Russian world (Dragnev 2021). |

| 2 | |

| 3 | BAR Ms. Sl. 494, ff. 1r–7r (Panaitescu 2003, p. 324). |

| 4 | Translated by Mihail-George Hâncu. |

| 5 | See note 4 above. |

| 6 | Wortley (2010, p. 96): A brother was tempted by the devil not to believe in the Eucharist. The brothers prayed for him, and after the service he told them how he had seen two beings of great beauty [the first and third persons of the Holy Trinity?] together with a child, whom they cut and drew blood from, at the moment of the breaking of the bread. Part of the child’s flesh was given to the brothers as communion, and only when he confessed his faith in the Eucharist did the flesh turn into bread. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | These are the apse images in the churches of Agios Panteleimon in Velandia (last third of the 13th century), Agioi Theodoroi in Kaphiona (1263/1270), Agios Chrysostomos in Geraki (1300), Agios Andreas in Kato Kastania (1375–1400), Cheimatissa in Floka (1400), and Agios Georgios in Maleas (early 15th century). See Konstantinidi (1998, Figures 4–8). |

| 9 | The liturgical books copied in Moldova, the earliest dating from the beginning of the 16th century, are more similar to trebniks, lacking diataxic indications that describe the liturgical actions. |

| 10 | For a mystical interpretation of priestly vestments, see St. Symeon of Thessalonica, “Explanation of the Divine Temple” (in Hawkes-Teeples 2011). |

| 11 | The Angelic liturgy is painted at the base of the dome in the churches of St. Nicholas in Probota Monastery, 1532–1534 and St. George in Suceava, 1534. |

| 12 | |

| 13 | It is noteworthy that the Czech priest Peter (13th century) was recognized for his skepticism regarding the transubstantiation, which was subsequently dispelled by the miracle of the bleeding Host in Bolsena. A parallel to the Moldavian text can be found in Revelations of Saint Bridget of Sweden (Book 4, Chapters 61, 117, 121), which includes the vision of Christ as a child and the presence of demons and angels at the altar. |

| 14 | |

| 15 | Ibid., W434, p. 172: Mark remained in his cell for thirty years. A priest came to celebrate the liturgy for him. One day, the devil came to Mark in the form of a possessed man who wanted to be exorcised, and shouted, “Your priest smells of sin!” But Mark drove the spirit away. When the priest came again to officiate, Mark saw an angel descend and lay his hand on the priest’s head, turning him into a pillar of fire. He heard a voice saying, “If an earthly king does not allow his nobles to stand before him in dirty clothes, how much more does divine power cleanse the servants who stand before heavenly glory?” |

| 16 | Ibid.,W965: A priest with the gift of vision saw a being with a splendid appearance who came out of the altar at the moment the psalms were sung. He had a vessel with holy water and a spoon with which he marked those who participated by making the sign of the cross, but he also marked some empty places. He did the same thing at the end of the service. He asked for an explanation of the vision. The being was an angel who marked those who remained until the end, but also those who were spiritually present, although, for valid reasons, they were not physically present. |

| 17 | Ibid., W829: The patrician Valerian, prince of Porto (i.e., Pontus?), was very dissolute and died unrepentant. His wife, however, managed to bribe the bishop, and so Valerian was buried in the church of St. Faustinus. The saint appeared to the church administrator, asking him to tell the bishop to remove the body from the church, otherwise he would die within thirty days. The administrator was afraid to tell the bishop, even though the vision was repeated three times. The bishop died suddenly within the announced time. The administrator then heard a cry from the tomb: “I am burning!” They opened the tomb but found only the shrouds inside. The body was found outside the church, naked. The shrouds were hung in the church as a warning against burying other sinners there. Ibid, W040: A bishop excommunicated a priest, and this priest was martyred while still under the curse. His relics were bought by a Christian, who built a church over them. But at the consecration of the church, when the priest proclaimed “The peace be with you”, the coffin came out of the church. This happened three times. During the night, the martyr appeared to the bishop and explained the reason. The narrative continues in two slightly different versions of the text: in the first, the local bishop obtains a written pardon from the bishop who had stopped the priest, which he reads over the tomb; in the other, the local bishop sends for the bishop of this priest to come and personally lift the ban he had imposed, thus absolving the dead man. In both versions, the action results in the martyr’s remains remaining in place. |

| 18 | Ibid., W122 = no. 56 in Nau (2009): Isidore the Scholastic [i.e., scholar or lawyer] recounts how a man in Alexandria had a tumor on his head the size of an apple; he made the sign of the cross over it with the Eucharist every time he received communion. One day, he saw through a crack in the door how the sacristan of the church was making love to a woman; but he did not blame the priest, because communion is received from the hands of angels, not of men. He received the Eucharist and his tumor was healed. |

| 19 | Sic, recte пocтaвлѣeть (that is, ‘he puts on’). |

| 20 | This corresponds to the prayer for vesting the sticharion: “My soul shall rejoice in the Lord, for He has clothed me with the garment of salvation and adorned me with the robe of joy; He has set a crown on my head and adorned me as a bride” (cf. Is 61:10). |

| 21 | This corresponds to the prayer for vesting the epitrachelion: “Blessed is God, who pours out His grace upon His priests, like the oil upon the head, which runs down upon the beard, even upon the beard of Aaron, which runs down upon the edge of his garments” (cf. Ps 132/133:2). |

| 22 | This does not correspond to the prayer for vesting the belt: “Blessed is God, who girded me with strength, and makes my way perfect. He makes my feet like the feet of a deer; He causes me to stand on the heights” (cf. Ps 17/18:35–36). |

| 23 | This has no correspondence with the prayer for vesting the felon: “Your priests, O Lord, will put on righteousness, and Your saints will rejoice in joy forever, now and forever and ever” (cf. Ps 131/132:9). |

| 24 | Acclamation of the priest at the proskomede, before the excision of the amnos. |

| 25 | The identification of the asterisk as “ribs,” obviously prompted by the object’s shape, shows the affinity of this text to the tradition of mystagogic texts from the Russian milieu, where the asterisk is interpreted symbolically as the ribs of God (Afanasyeva 2012, p. 148). In all contemporary liturgical written evidence from Moldavia, the asterisk is called “the star” (звѣздa), literal translation of the Greek asteriskos. |

| 26 | Cf. St. Symeon of Thessalonica, “On the Sacred Liturgy”, sect. 32: “What is called ‘asterisk’ represents the stars, especially the one at the birth of Christ.” (Hawkes-Teeples 2011, p. 185). |

| 27 | An obscure passage in the text, the proposed translation is based on the version published by K. Ivanova in which the lines that correspond to this part of the text from Putna explicitly indicates as liturgical action the reception of the censer by the priest (Ivanova 2002, p. 14). In the Moldavian Slavonic text, the object is called мeтлицѫ, which can be translated as “twig” or, in the terminology specific to the Russian environment, the sponge for cleaning liturgical vessels. |

| 28 | Sic, compare to the text edited by K. Ivanova, in which the corresponding passage describes the receiving of the censer (кaдилнцѫ). The shift could have been prompted by the formal similitude of the liturgical knife (кoпиe/λογχή—the spear) with a rod (мeтлицѫ). |

| 29 | The deacon’s acclamation that opens the Eucharistic liturgy. |

| 30 | Antiphon I of the Eucharistic liturgy. |

| 31 | Antiphon II of the Eucharistic liturgy. |

| 32 | Antiphon III of the Eucharistic liturgy. |

| 33 | Sic, recte днe въceгo cъвpъшeнa… aггелa миpнa… |

| 34 | Acclamation of the priest before dismissing the catechumens. |

| 35 | Dismissal of the catechumens. |

| 36 | Not found in the liturgical text. Cf. Ps. 50/51:1–2. |

| 37 | Not found in the liturgical text, recte “That the whole day may be perfect… an angel of peace…” |

| 38 | Acclamation of the priest at the beginning of the Eucharistic anaphora. |

| 39 | Sic (нe is written twice). |

| 40 | Sic. |

| 41 | Acclamation of the priest before the hymn “Holy, holy, holy.” |

| 42 | Superscript: двoю. To reflect this emendation parentheses were used in the translation, i.e. “(the two)”. |

| 43 | Despite its similitude to “sung service” (the asmatike akolouthia characteristic for the cathedral rite), the term should be understood within the obvious monastic context in which the narrative takes place. |

References

- Afanasyeva, Tatyana. 2012. Дpeвнecлaвянcкиe тoлкoвaния нa литypгию в pyкoпиcнoй тpaдиции XII–XVI вв.: Иccлeдoвaниe и тeкcты [Old Slavonic Interpretations of the Liturgy in the Manuscript Tradition of the XII–XVI Centuries: Studies and Texts]. Moskow: Унивepcитeт Дмитpия Пoжapcкoгo. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Benjamin, and Mirela Ivanova, eds. 2023. Is Byzantine Studies a Colonialist Discipline? Toward a Critical Historiography. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baschet, Jérôme. 1996. Inventivité et sérialité des images médiévales. Pour une approche iconographique élargie. Annales 51: 93–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedros, Vlad. 2012. The Cosmic Liturgy and its Iconographic Reflections in Moldavian Late Medieval Images. In Matérialité et immatérialité dans l’Eglise au Moyen Age. Actes du colloque tenu à Bucarest le 22 et 23 octobre 2010. Edited by Stéphanie Diane Daussy, Cătălina Gârbea, Brîndușa Grigoriu, Anca Oroveanu and Mihaela Voicu. Bucharest: Bucharest University, pp. 467–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bedros, Vlad, and Elisabetta Scirocco. 2019. Liturgical Screens, East and West. Liminality and Spiritual Experience. In The Notion of Liminality and the Medieval Sacred Space. Convivium: Exchanges and Interactions in the Arts of Medieval Europe, Byzantium, and the Mediterranean. Supplementum. Edited by Ivan Foletti and Klára Doležalová. Brno: Masarykova univerzita, vol. 3, pp. 68–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bornert, René. 1966. Les commentaires byzantins de la divine liturgie du VIIe au XVe siècle. Paris: Institut Français d’études Byzantines. [Google Scholar]

- Ciobanu, Constantin I. 2007. Stihia profeticului. Sursele literare ale imaginii „Asediul Constantinopolului” şi ale „Profeţiilor” înţelepţilor Antichităţii din pictura medievală moldavă [The Stoicheon of Prophetic. Literary Sources of the Image “The Siege of Constantinople” and of the “Prophecies” of the Wise Men of Antiquity in Medieval Moldavian Painting]. Chişinău: Institutul Patrimoniului Cultural. [Google Scholar]

- Dragnev, Emil. 2021. Ohrida, Moldova și Rusia Moscovită, noul context al legăturilor artistice după căderea Constantinopolului [Ohrid, Moldavia, and Muscovite Russia, the new context of artistic ties after the fall of Constantinople]. In Românii și creștinătatea răsăriteană (secolele XIV–XX) [Romanians and Eastern Christianity (14th–20th Centuries)]. Edited by Petronel Zahariuc. Iași: Doxologia, pp. 113–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu, Andrei. 2021. Între o retorică a puterii și intercesiune: Câteva observații cu privire la selecția figurilor iconice din naosul bisericii Sf. Nicolae din Rădăuți (c. 1480–1500) [Between a rhetoric of power and intercession: Some observations on the selection of iconic figures in the nave of St. Nicholas Church in Rădăuți (c. 1480–1500)]. Analele Putnei 17: 67–96. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu, Andrei. 2022a. The Visionary Emperor: Constantine the Great and the Archangel Michael in Late Fifteenth-Century Moldavian Representations. Master’s thesis, Central European University, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu, Andrei. 2022b. Visions of the Incarnation: King David, the “Royal Deesis,” and Associated Iconographic Contexts in Late 15th-century Moldavia. In Byzantine Heritages in South-Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period. Études byzantines et post-byzantines, Nouvelle série 4 (XI). Edited by Andrei Timotin, Srđan Pirivatrić and Oana Iacubovschi. Bucharest: Romanian Academy, pp. 225–68. [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond, Anthony. 2008. Art and the Periphery. In The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies. Edited by Robin Cormack, John F. Haldon and Elizabeth Jeffreys. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 770–76. [Google Scholar]

- Elian, Alexandru. 1964. Moldova și Bizanțul în secolul al XV-lea [Moldova and Byzantium in the 15th Century]. In Cultura moldovenească în timpul lui Ștefan cel Mare [Moldavian Culture under Stephen the Great]. Edited by Mihai Berza. Bucharest: Academy of the Romanian People Republic, pp. 97–179. [Google Scholar]

- Garidis, Miltiados-Milton. 1989. Les Balkans et la Moldavie à la fin du XVe siècle. In La peinture murale dans le monde orthodoxe après la chute de Byzance (1450–1600) et dans les pays sous domination étrangère. Athens: C. Spanos, pp. 117–23. [Google Scholar]

- Georgitsoyanni, Evangelia N. 1993. Les rapports de l’atelier avec les peintures de Moldavie. In Les peintures murales du vieux catholicon du monastère de la Transfiguration aux Météores. Athens: Εθνικό και Καποδιστριακό Πανεπιστήμιο Aθηνών, pp. 416–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstel, Sharon. 1999. Beholding the Sacred Mysteries: Programs of the Byzantine Sanctuary. Seattle and London: College Art Association. [Google Scholar]

- Glibetic, Nina. 2014. The Byzantine enarxis psalmody on the Balkans (thirteenth–fourteenth century). In Rites and Rituals of the Christian East. Edited by Bert Groen, Daniel Galadza, Nina Glibeticand and Gabriel Radle. Louvain: Peeters, pp. 329–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes-Teeples, Steven. 2011. St. Symeon of Thessalonika. The Liturgical Commentaries. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs Strickland, Debra. 2003. Saracens, Demons, and Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iacubovschi, Oana. 2015. Christ Pantocrator Surrounded by the Symbols of the Evangelists: The Place and the Meaning of the Image in Post-Byzantine Mural Painting. The case of Moldavian Cupolas (15th–16th centuries). Revue des Études Sud-Est Européennes 53: 131–53. [Google Scholar]

- Iufu, Ioan, and Victor Brătulescu. 2012. Manuscrise slavo-române din Moldova. Fondul Mănăstirii Dragomirna [Slavic-Romanian manuscripts from Moldova. The Dragomirna Monastery Collection]. Edited by Olimpia Mitric. Iași: A.I. Cuza University. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, Klimentina. 2002. Cлoвo нa cв. Bacилий Beлики и нa oтeц Eφpeм зa cвeтaтa Литypгия, кaк пoдoбaвa дa ce cтoи в цъpквaтa cъc cтpax и тpeпeт [Discourse of St. Basil the Great and Father Ephrem on the Holy Liturgy, how one should stand in church with fear and trembling]. Palaeobulgarica 26: 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidi, Chara. 1998. Τό δογματικό ὑπόβαθρο στήν ἀψίδα τοῦ Ἁγίου Παντελεήμονα Βελανιδιῶν [The Doctrinal Background of the Apse Decoration of the Church of Agios Panteleimon, Velanidia]. Δελτίον τῆς Χριστιανικῆς Ἀρχαιολογικῆς Ἑταιρείας 20: 165–75. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidi, Chara. 2008. O Μελισμός. Oι συλλειτουργούντες ιεράρχες και οι άγγελοι-διάκονοι μπροστά στην Aγία Τράπεζα με τα Τίμια Δώρα ή τον Ευχαριστιακό Χριστό [The Melismos. The Co-Officiating Hierarchs and the Angel-Deacons Flanking the Altar with Holy Bread and Wine or the Eucharist Christ]. Thessaloniki: Κέντρο Βυζαντινών Ερευνών. [Google Scholar]

- Mango, Cyril. 1992. Diabolus Byzantinus. In Homo Byzantinus: Papers in Honor of Alexander Kazhdan. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks, vol. 46, pp. 215–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mariev, Sergei. 2013. Introduction. In Aesthetics and Theurgy in Byzantium. Edited by Sergei Mariev and Wiebke-Marie Stock. Boston and Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Marinis, Vasileios. 2014. Architecture and Ritual in the Churches of Constantinople: Ninth to Fifteenth Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Mircea, Ion Radu. 2005. Répertoire des manuscrits Slaves en Roumanie. Auteurs Byzantins et Slaves. Edited by Pavlina Bojčeva and Svetlana Todorova. Sofia: Institut d’Études balkaniques. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Mirkovich, Lazar. 1931. Aнђeли и дeмoни нa кaпитeлимa y цpкви cв. Димитpиja Mapкoвa мaнacтиpa кoд Cкoпљa [Angels and Demons on the capitals in the church of St. Demetrius od the Markov Manastir near Skopje]. Cтapинap 6: 3–13. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Nau, François, ed. 2009. Le texte grec des récits utiles à l’âme d’Anastase (le Sinaite). Piscataway: Gorgias Press. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Obolensky, Dimitri. 1974. The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe. London: Cardinal. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Panaitescu, Petre P. 1959. Manuscrise slave din Biblioteca Academiei R. P. R. [Slavonic Manuscripts in the Library of the Romanian Academy]. Bucharest: Academy of the Romanian People Republic, vol. 1. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Panaitescu, Petre P. 2003. Catalogul manuscriselor slavo-române și slave din Biblioteca Academiei Române [Catalogue of Slavonic and Slavo-Romanian Manuscripts in the Library of the Romanian Academy]. Edited by Dalila-L. Aramă and Gheorghe Mihăilă. Bucharest: Romanian Academy, vol. 2. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Peers, Glenn. 2001. Subtle Bodies: Representing Angels in Byzantium. Berkley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Picchio, Riccardo. 1959. Storia della letteratura russa antica. Milan: Nuova Accademia. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Popescu, Paulin. 1962. Manuscrise slavone din Mănăstirea Putna [Slavonic Manuscripts at Putna Monastery]. Bucharest: Biserica Ortodoxă Română, vol. 80, pp. 105–45, 688–711. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Rigo, Antonio. 2012. Principes et canons pour le choix des livres et la lecture dans la littérature spirituelle byzantine (XIIIe–XVe siècle). Bulgaria Mediaevalis 3: 171–85. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Russell, Norman. 2017. The Hesychast Controversy. In The Cambridge Intellectual History of Byzantium. Edited by Antony Kaldellis and Niketas Sinissoglou. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 494–508. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Schultz, Hans Joachim. 1986. The Byzantine Liturgy: Symbolic Structure and Faith Expression. New York: Pueblo Publishing. [First published as Die byzantinische Liturgie. Vom Werden ihrer Symbolgestalt. Trier: Paulinus, 1964]. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Sinigalia, Tereza. 2007. Relația dintre spațiu și decorul pictat al naosurilor unor biserici de secol XV–XVI din Moldova [The Relationship between Space and the Painted Decoration of the Naves of 15th–16th Century Churches in Moldova]. Revista Monumentelor Istorice 76: 46–62. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Sinigalia, Tereza. 2015. La Liturgie Céleste dans la peinture murale de Moldavie. Anastasis: Research in Medieval Culture and Art 2: 28–50. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Ștefănescu, Ioan D. 1936. L’illustration des liturgies dans l’art de Byzance et de l’Orient. Brussels: Institut de Philologie et d’Histoire Orientales. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Taft, Robert S. J. 1996. Ecumenical scholarship and the Catholic–Orthodox epiclesis dispute. Östkirchliche Studien 45: 201–26. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Taft, Robert S. J. 2000. The Frequency of the Eucharist in Byzantine Usage: History and Practice. Studi sullo’Oriente cristiano 4: 103–32. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Turdeanu, Emil. 1942. Miniatura bulgară și începuturile miniaturii românești [Bulgarian Miniature and the Beginnings of Romanian Miniature]. Buletinul Institutului Român din Sofia 2: 395–452. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Vasiliu, Anca. 1994. Observații și ipoteze de lucru privind picturile murale aflate în curs de restaurare [Observations and working hypotheses regarding the murals undergoing restoration]. Studii și Cercetări de Istoria Artei 41: 60–81. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Walter, Christopher. 1982. Art and Liturgy of the Byzantine Church. London: Variorum Publications. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Walter, Christopher. 2000. The Christ Child on the Altar in the Radoslav Narthex: A Learned or Popular Theme? In Pictures as Language. How the Byzantines Exploited Them. London: Pindar Press, pp. 229–42. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Woodfin, Warren T. 2012. Liturgical Mystagogy and the Embroidered Image. In The Embodied Icon: Liturgical Vestments and Sacramental Power in Byzantium. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 103–30. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Wortley, John. 2010. The Repertoire of Byzantine “Spiritually Beneficial Tales”. Scripta & E-scripta 8–9: 93–306. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Zheltov, Michael. 2011. The Moment of Eucharistic Consecration in Byzantine Thought, in Issues in Eucharistic Praying in East and West. In Essays in Liturgical and Theological Analysis. Edited by Maxwell E. Johnson. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, pp. 263–306. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Zheltov, Michael. 2015. The “Disclosure of the Divine Liturgy” by Pseudo-Gregory of Nazianzus: Edition of the Text and Commentary. Bollettino della Badia Greca di Grottaferrata III: 215–35. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bedros, V.; Hâncu, M.-G. The Angel, the Demon, and the Priest: Performing the Eucharist in Late Medieval Moldavian Monastic Written and Visual Cultures. Religions 2025, 16, 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101259

Bedros V, Hâncu M-G. The Angel, the Demon, and the Priest: Performing the Eucharist in Late Medieval Moldavian Monastic Written and Visual Cultures. Religions. 2025; 16(10):1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101259

Chicago/Turabian StyleBedros, Vlad, and Mihail-George Hâncu. 2025. "The Angel, the Demon, and the Priest: Performing the Eucharist in Late Medieval Moldavian Monastic Written and Visual Cultures" Religions 16, no. 10: 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101259

APA StyleBedros, V., & Hâncu, M.-G. (2025). The Angel, the Demon, and the Priest: Performing the Eucharist in Late Medieval Moldavian Monastic Written and Visual Cultures. Religions, 16(10), 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101259