How to Grow a Buddha Body?—A Case Study of the “Bodhisattva Holding Up the True Body” (Peng zhenshen pusa 捧真身菩薩) Statue at the Famen Temple

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The “Bodhisattva Holding up the True Body” (Peng zhenshen pusa 捧真身菩薩) Statue

奉為睿文英武明德至仁大聖廣孝皇帝,敬造捧真身菩薩,永為供養。伏願聖壽萬春,聖枝萬葉,八荒來服,四海無波。鹹通十二年辛卯歲十一月十四日皇帝延慶日記

I [Chengyi] respectfully make the “Bodhisattva holding up the True Body” for the “Civilized Martial Bright Virtue Utmost Compassion Great Sage Filial Emperor” in perpetual veneration [to the śarira]. I hope that the emperor’s longevity lasts ten thousand springs, the imperial branches propagate ten thousand leaves, the barbarians from the eight corners come to show their obeisance, and in the four seas there is not a single wave.—14th day of the 11th month, 871, on the emperor’s birthday7

2.1. Previous Scholarship

2.2. Overview of the Bodhisattva Statue’s Tripartite Pedestal

Upper Siddhi 上品悉地: Ā vaṃ raṃ haṃ khaṃ 阿鍐覽唅欠

Middle Siddhi 中品悉地: Ā vi ra hūṃ khaṃ 阿尾羅吽欠

Lower Siddhi 下品悉地: Ā ra pa ca na 阿羅波遮那

2.3. Base—Visualizing Cosmology

地水火風空五輪之種子。阿鑁覽唅欠五字。有地輪。地輪之上有水輪。水輪之上有火輪。火輪之上有風輪。風輪之上有空輪…即變成妙高山王。以四寶所成…虛空中想毘盧遮那佛身毛孔。流出香乳。雨澍七金山間。以成八功德香水乳海。

The five syllables—a-vaṃ-raṃ-haṃ-khaṃ—are the seed syllables of the Five Wheels (cakra): Earth, Water, Fire, Wind, and Space. Below lies the Earth Wheel, above it rests the Water Wheel, above Water is the Fire Wheel; above Fire is the Wind Wheel, and atop Wind is the Space Wheel…Then, these transform into Mount Sumeru, the sovereign of mountains, composed of the Four Treasures…Within the vast void, one should visualize the body of Mahāvairocana Buddha, from whose pores flows fragrant nectar, raining down between the seven golden mountains and forming the eight fragrant milky oceans.(T. 906_.18.0912c22-913a02)

阿鑁覽唅欠…即是東西南北中方佛種字也, 山海大地,江河萬流,日月星辰,金玉珍寶,火珠光明,五果五榖…皆是阿鑁覽唅欠所管也。

A-vaṃ-raṃ-haṃ-khaṃ are the seed syllables (bīja) of the Buddhas of the five directions: east, west, south, north, and center. Mountains and oceans, the great earth, rivers and myriad streams, the sun, the moon, stars and constellations, gold and jade, and all precious treasures, the flaming jewel (mani) of radiant light, the five fruits and five grains—all are governed by a-vaṃ-raṃ-haṃ-khaṃ.

2.4. Base—Growth of Life

凡人汗栗馱心(此云真實心)形猶如蓮花合而未敷之像…觀此蓮花令其開敷為八葉白蓮花…從此出生阿、 鑁、囕、唅、欠五輪字…從臍至心為金剛臺(海中立莖)臍為大海。從臍已下此地居諸尊位。在海岸邊也。

The hṛdaya heart (true mind) of an ordinary person is shaped like a closed lotus bud, yet to bloom … One is to visualize this lotus bud opening into an eight-petaled white lotus flower … from which generates the five letters: a, vaṃ, raṃ, haṃ, khaṃ … The vajra platform extends from the navel to the heart (like a lotus stem rising from the ocean) while the navel itself represents the great sea. Below the navel is the domain where the various deities reside, positioned along the ocean’s shore.(T. 905_.18.0911b06-b20)

出悉地 (根莖 從足至腰 化身)

Siddhi of Exiting (the roots and stems; from feet to waist; the Response Body)

入悉地 (枝葉 從臍至心 報身)

Siddhi of Entering (the branches and leaves; from navel to heart; the Reward Body)

成就悉地 (從心至頂 法身 佛果)

Siddhi of Accomplishment (from heart to crown; the Dharma Body; the fruit of Buddhahood).(T. 906_.18.0914a01-02)27

3. Dresses—A Substitute Body

3.1. Kāṣāya—The Embryonic Robe

承茲福力於五百身中陰生陰恒服此衣。以最後身從胎倶出。身既漸長。衣亦隨廣。及阿難之度出家也。其衣變爲法服。及受具戒。更變爲九條僧伽胝。將證寂滅入邊際定。

By virtue of the auspicious merit of Śāṇavāsa’s offering to the Sangha, he constantly wore this robe in the intermediate states of five hundred existences. And his final rebirth, he emerged from the womb already clothed in the robe. As his body grew, the garment expanded accordingly. When he was ordained by Ananda, the robe transformed into a monastic robe. Upon receiving full precepts, it further changed into a nine-columned kāṣāya, preparing him for attaining Nirvana and entering the boundless concentration.(T. 2087_.51.0873b28-c08)

人之有胞,猶木實之有扶也。包裏兒身,因與俱出,若鳥卵之有殼。

Humans have the embryonic coat exactly like how the tree’s fruit has a supportive membrane: it wraps around the fetus’s body and comes out of the womb with it, just like how bird eggs have shells.

3.2. Whose Body?

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T | Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大蔵経, 85 vols. (Tokyo: Taishō issaikyō kankōkai, 1924–1932) |

| X | Xuzangjing 續藏經, 150 vols. (Taipei: Xinwenfeng, 1975) |

| 1 | Seng Che 僧澈, Datang Xiantong qisong Qiyang zhenshen zhiwen 大唐鹹通啟送岐陽真身志文 [Commemorative inscription on the translation of the True Body relic to Qiyang in the Xiantong Era of the Great Tang], dated 874 (Shanxi Sheng kaogu yanjiusuo 2007, p. 229). |

| 2 | The Tang imperial tradition of periodically translating the relic to the imperial palace started from Tang Taizong 唐太宗 (626–649). The True Body (zhenshen 真身) of the Buddha was believed to have therapeutic, state-protecting potency, ensuring the health of the ruler and the prosperity of the realm. Moreover, from Gaozong onward, the timing of the opening of the crypt and transportation of the relic to the imperial palace often coincided with the failing health of the reigning emperor. See (Wang 2005, pp. 71–120; 2014, pp. 51–71; Sen 2014, pp. 27–49). |

| 3 | The object is recorded in the Inventory stele in the following entry: Yin jinhua pusa yi qu, bing zhenzhu zhuang, gong zhong wushi liang. Bing yin leng han sheng yin suozi er ju, gong zhong yi liang, Seng Cheng yishi 銀金花菩薩一躯,並真珠裝,共重五十兩。並銀棱函盛銀鎖子二具,共重一兩,僧澄依施 [One gilded silver Bodhisattva statue, adorned with pearls, weighing a total of fifty taels. In addition, two silver chain-locks contained in a silver-edged casket, together weighing one tael. Donated by the monk Chengyi]. In Yingcong Chongzhensi suizhenshen gongyangdaoju ji enci jinyinqiwu baohan deng bing xinenci dao jinyinbaoqi yiwuzhang 應從重真寺隨真身供養道具及恩賜金銀器物寶函等並新恩賜到金銀寶器衣物帳 [Inventory of ritual implements, along with the gold and silver vessels, caskets, and other items previously offered to the Chongzhen Monastery, was to accompany the True Body relic together with the newly bestowed gold and silver treasures, garments, and textiles], dated 874 (Shanxi Sheng kaogu yanjiusuo 2007, p. 228). |

| 4 | Shang yu anfu men, jianglou mobai, liuti zhanyi 上御安福門,降樓膜拜, 流涕霑臆 [The emperor went to the Anfu Gate, descended the tower, prostrated (in front of the relic) in reverence, and wept with tears streaming down, soaking his chest]. Sima Guang 司馬光, Zizhi tongjian 資治通鑑 [Comprehensive Mirror to Aid in Government], juan 252, vol. 17 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1956, p. 8165). As art historian Eugene Wang has demonstrated, from the late 7th century onwards, there was an increasing conflation between the śarīra—the Buddha’s True Body—and the imperial body, as evident through the striking coincidence between the relic translation and the death of the emperor. (Wang 2014, p. 53). |

| 5 | In esoteric Buddhism, enlightenment is signified through the practitioner becoming and merging with the body of Mahāvairocana. In this sense, the ultimate spiritual liberation is equated with the attainment of the Dharma Body—materially signified by the physical presence of the True Body, or the relic. |

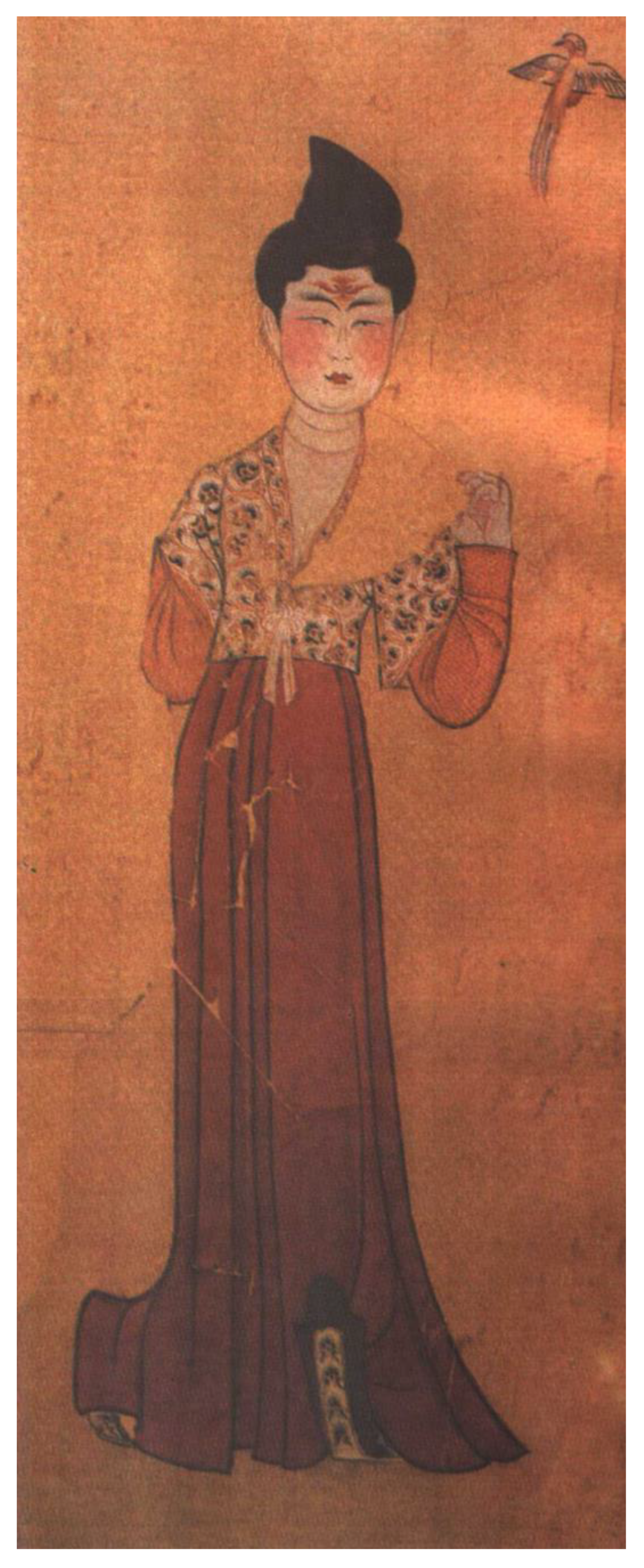

| 6 | Past scholars have proposed several hypotheses regarding the Bodhisattva’s identity. In summary, first, scholars Wu Limin and Han Jinke identified the figure as the Hindu Goddess of Fortune Lakṣmī—popularized in Tang Buddhism through the Jinguangming zuishengwang jing 金光明最勝王經 [The Sutra of Golden Light] (T. 665)—based on the effeminate appearance, rich bejeweled accessories, and heavenly garments of the figure (Wu and Han 2000, p. 66). Second, it has been suggested that the Bodhisattva essentially serves as a sculptural embodiment of the Emperor Yizong, venerating the relic and mandala in the rear chamber in eternity (Tang 1999, pp. 66–67). Third, recently, the scholar Ge Chengyong has suggested that the figure is not a goddess or Bodhisattva, but rather a representation of an esoteric Buddhist monk performing rituals on behalf of the emperor (Ge 2010, pp. 87–90). Although the exact identity of the figure is difficult to pin down, I think that it is most likely a Bodhisattva based on the Yiwuzhang 衣物賬 inventory record, also considering the figure’s crown with a seated Buddha figure inside (huafo guan 化佛冠). Moreover, the Bodhisattva is in the gesture of hugui 胡跪 (kneeling on one knee) while holding up the relic over their head, expressing the highest level of veneration towards the True Body. At the same time, hugui is a common pose assumed by practitioners in esoteric Buddhist rituals. In this way, I agree with previous scholars that the Bodhisattva simultaneously stands for a practitioner who not only worships the relic, but also activates the ritual program embodied by the statue’s pedestal. Finally, it is important to not overlook the Bodhisattva’s extremely luxurious garments and accoutrements, which could be connected to the hidden significance of the statue discussed later in this essay. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | In past studies, the garments were often overlooked or considered unrelated to the Bodhisattva statue, although some scholars propose that the miniature size of the clothing points to the possibility that they were meant to dress the Bodhisattva statue. The scholar Ge Chengyong further suggests that the existence of the miniature monastic robe reaffirms the figure’s identity as a high-ranking Buddhist monk (Ge 2010, pp. 87–90). Considering that the garments—made from the same textiles—were deposited together with the statue in the same containers, I think that it is highly likely that these objects were intended as a coherent set in their religious symbolism and ritual function, as this paper will proceed to demonstrate. However, I do not agree that the garments are for the Bodhisattva, as the sculpted figure is clearly dressed. |

| 9 | The Buddhist scholar Robert Sharf similarly points out the lack of basis for the Garbhadhātu Maṇḍala identification of the bottom part of the pedestal and rejects Wu and Han’s proposal of the statue’s embodiment of “unity of the two worlds.” (Sharf 2011, p. 42). |

| 10 | With most extant examples surviving in Japan, the Buddhalocanī Maṇḍala derives from the ninth chapter, Vajraśri Mahā-siddhi, in the Jingangfeng louge yiqie yujia yuqi jing 金剛峯樓閣一切瑜伽瑜祇經 [Pavilion of Vajra Peak and All Its Yogas and Yogins Sutra], T. 867. Lai follows the earlier hypothesis proposed by the Chinese scholar Liang Zi, who also suggests that the statue’s base might be a Buddhalocanī Maṇḍala (Liang 1994, pp. 4–19). Scholars such as Luo Zhao also point to the connection of the iconographic program with the Buddhoṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Maṇḍala (Foding zunsheng tuoluoni mantuoluo 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼曼陀羅) (Luo 2014, p. 140). |

| 11 | As Sharf points out, the Famensi finds do not exhibit a coherent Esoteric doctrinal system, and he proposes to view the Tang esoteric Buddhist texts and liturgies as a kind of ritual technology (techné). This paper follows this call to focus more on the ritual function, religious significance, and performative aspect of the Bodhisattva statue, rather than reducing material culture to a manifestation of theology (Sharf 2011, pp. 42–43). |

| 12 | Esoteric Buddhist liturgies often prescribe the placement of karma-vajra in the four corners of the altar to designate an indestructible, sacred ritual arena. The appearance of the karma-vajra motif echoes the rear chamber, where four vases with the karma-vajra symbols were placed in the four corners of the room. |

| 13 | There is much debate in terms of the exact iconographic identification of the Eight Wisdom Kings on the bottom layer of the base: here I am following the identification of Lai, who suggests that Āryācalanātha (Budong 不動) is replaced here by Ucchuṣma (Wushushamo 烏樞沙摩). An alternative identification by Yoritomi identifies the figures as Trailokyavijaya (Jiangsanshi 降三世), Yamântaka (Daweide 大威德), Kuṇḍalī (Juntuli 軍荼利), Aparajitah (Wunengsheng 無能勝), Hayagrīva (Matou 馬頭), Mahācakra (Dalun 大輪), Padanakṣipa (Buzhi 步擲), and Āryācalanātha (Budong 不動) in clockwise sequence (Yoritomi 2000, pp. 320–24). For a comparative iconographic program of Eight Wisdom Kings on the forty-five-deity reliquary in the rear chamber of Famensi, see (Mita 2005, pp. 9–31). |

| 14 | Yoritomi has attempted to match the bīja seeds and Eight Wisdom Kings according to T. 965. |

| 15 | It should be noted that even formally, the positions of the bīja do not align with those of the vidyarāja. |

| 16 | Similar iconographies of Vaiśravaṇa as a regal, militant guardian can be seen in contemporaneous Late Tang Dunhuang Mogao Cave murals such as the west wall of Cave 107, built in 871. For the interregional iconographic influences of the Vaiśravaṇa iconography and its royal connections, see (Shim 2025). The imperial patronage and worship of Vaiśravaṇa became popular in tandem with esoteric Buddhism during the Tang dynasty. Moreover, as Eugene Wang points out, Vaiśravaṇa plays an important “symbolic border-crossing mission” in the postmortem soteriological scheme of the fourth casket of the eightfold reliquary in the Famensi rear chamber, as north is associated with death in the traditional Chinese cosmological scheme (Wang 2014, p. 61). |

| 17 | For an introduction to the Diamond Realm and Womb Realm Mandalas, see (Grotenhuis 1998, pp. 33–77). |

| 18 | Three translations exist for the scripture of the five-syllable mantra of Mañjuśrī: Amoghavajra (Bukong 不空), A Chapter of the Mañjuśrī Method from the Vajraśekhara Yoga (Jingangdingjing yuqie wenshushili pusafa yipin 金剛頂經瑜伽文殊師利菩薩法一品) (T. 1171.20.705–709); Amoghavajra, Victorious Aspect of Mañjuśrī’s Five-Syllable Mantra, from the Three Worlds Conqueror Scripture of the Vajraśekhara Yoga (Jingangding chaosheng sanjiejing shuo wenshu wuzi zhenyan shengxiang 金剛頂超勝三界經說文殊五字眞言勝相) (T. 1172.20.709–710); Vajrabodhi (Jingangzhi 金剛智), Five-syllable Essential Dhāraṇī of Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī from the Vajraśekhara Yoga (Jingangdingjing manshushīli pusa wuzi xintuoluoni pin 金剛頂經曼殊室利菩薩五字心陀羅尼品) (T. 1173.20.710). |

| 19 | Enchin 円珍, Ketsuji sanshu shijjihō 決示三種悉地法 [An Explanation of the Three Siddhi Methods]. Accessed through Kyoto University digital archive: https://rmda.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/item/rb00019033#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&r=0&xywh=-3968%2C-224%2C13950%2C4462 (accessed on 8 September 2025). For a detailed study of the Three Siddhi mantras inscribed on Bodhisattva statue, see (Lü 2008, pp. 151–67). |

| 20 | Attributed to Śubhakarasiṃha (Shanwuwei 善無畏), Sanzhong xidi podiyu zhuanyezhang chusanjie mimi tuoluoni fa 三種悉地破地獄轉業障出三界祕密陀羅尼法 [Secret Dhāraṇī Method of Three Attainments which Destroy Hell and Reverse Karmic Hindrances in the Three Worlds] (T. 905); Foding zunshengxin podiyu zhuanyezhang chusanjie mimisansehn foguo sanzhong xidi zhenyan yigui 佛頂尊勝心破地獄轉業障出三界祕密三身佛果三種悉地真言儀軌 [Manual of the Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Mantras for the Destruction of Hells, Transformation of Karmic Hindrances, and Exiting the Three Realms: The Secret Results of the Three Bodies and Three Attainments] (T. 906); Foding zunshengxin podiyu zhuanyezhang chusanjie mimi tuoluoni 佛頂尊勝心破地獄轉業障出三界祕密陀羅尼 [The Secret Dhāraṇī Method of the Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Mantras, which shatters the hells, transforms karmic obstacles, and enables escape from the Three Realms] (T. 907). Chen argues that the Japanese monk Annen 安然 (841–889?) fabricated the earliest Three Siddhi ritual manual, T. 907 to legitimize Tendai transmission (Chen 1998b). Chen’s argument was later published and supported by Charles Orzech (Chen 1998a, pp. 21–76; Orzech 2011, p. 327). |

| 21 | Indeed, much evidence speaks to the wide circulation and practice of the Three Siddhi mantra and ritual by the late Tang—which also explains their appearance on the Famensi Bodhisattva statue. First, the Three Siddhi are already discussed in earlier sūtras such as the Suxidi jieluo jing 蘇悉地羯囉經 [Tantra for Wondrous Achievement in All Endeavors], (T. 893) and Bodhiruci 菩提流支, Yizi foding lunwang jing 一字佛頂輪王經 [Sūtra of the One-Syllable Buddha-Crown Wheel King], (T. 951). Moreover, Japanese pilgrim monks such as Enchin and Jōgyō 常暁 (who studied in 838–839 in China) had mentioned and brought back the “Three Siddhi” mantra and ritual manual before Annen. See Jōgyō 常暁, Jōgyō oshō shōrai mokuroku 常暁和尚請来目録 [Catalogue of Documents Brought by the Reverend Jōgyō]: Dai birushana sanshu shijjihō ichikan 大毘盧遮那三種悉地法一卷 [One Fascicle on the Three Siddhi Methods of Mahāvairocana] (T. 2163_.55.1070a03). Moreover, even if T. 907 was compiled by the Japanese Tendai monk Annen as Chen claims—rather than being a late Tang work—Annen likely drew on pre-existing ideas and visualization surrounding the Three Siddhi mantras, as many overlaps could be observed in earlier scriptures. |

| 22 | In esoteric Buddhist rituals, the karma-vajra are often placed in the four corners of the altar—both to demarcate a sacred, indestructible ritual space and to suggest a cosmological realm. Based on the motif of dragons chasing the karma-vajra, Lai I-mann briefly mentions the possibility of the pedestal “constructing a self-contained microcosm, the ‘container visualization’ (Qijie guan 器界觀) in her dissertation chapter (Lai 2006, pp. 213–15). Building on Lai’s hypothesis, this paper further highlights the connection between the statue’s cosmological symbolism and the Three Siddhi mantra—and by extension, spiritual transformations. |

| 23 | Enchin 円珍, Ketsuji sanshu shijjihō 決示三種悉地法 [An Explanation of the Three Siddhi Methods]. |

| 24 | Zede shengzheng sanzhong xidi: yi, tianshang xidi; er, xukong xidi; san, dishang xidi. Cizheng sandi, sui shang, zhong, xia suo xiuchi fa defa yuancai 則得昇證三種悉地:一、天上悉地,二、虛空悉地,三、地上悉地。此證三地,隨上、中、下所修持法得法願財 [Thus one comes to realize the three kinds of siddhi: first, the heaven siddhi; second, the ākāśa siddhi; third, the earth siddhi. These three attainments correspond to the higher, middle, and lower levels of practice, through which one acquires the treasures of dharma, vows, and merit]. |

| 25 | Ershi fumu tanai juji. Zuihou jueding gechu yidi nonghou jingxue. Erdi hehe zhu mutai zhong hewei yiduan. Youru shuru ningjie zhishi. Dang yu cichu, yiqie zhongzi yishu suoshe, zhishou suoyi Alaiyeshi hehe yituo. Yunhe hehe yituo. Wei ci suochu nonghou jingxue hecheng yiduan, yu diandao yuan zhongyou jumie. Yu mie tongshi ji you yiqie zhongzi shi gongnengli gu, you yu weixigen ji dazhong hehe er sheng, ji yu yougen tongfen jingxue hehe tuansheng. Yu cishi zhong shuo shi yizhu jiesheng xiangxu, ji ciming wei jialuolan wei 爾時父母貪愛倶極。最後決定各出一滴濃厚精血。二滴和合住母胎中合爲一段。猶如熟乳凝結之時。當於此處。一切種子異熟所攝。執受所依阿頼耶識和合依託。云何和合依託。謂此所出濃厚精血合成一段。與顛倒縁中有倶滅。與滅同時即由一切種子識功能力故。有餘微細根及大種。和合而生。及餘有根同分精血和合摶生。於此時中説識已住結生相續。即此名爲羯羅藍位 [At that moment, when the father and mother, overcome with desire, each emitted a drop of dense seminal essence, the two drops united within the mother’s womb to form a single mass, like milk curdling when heated. At this point, all karmic seeds of maturation were gathered, and the ālaya-vijñāna (storehouse consciousness) that serves as the basis for appropriation—entered into conjunction and took its support. What does it mean to ‘enter into conjunction and take support’? It means that the dense essence combined into one mass, at which point the deluded intermediate being (antarābhava) ceases; simultaneously, through the power of the all-seed storehouse consciousness, subtle faculties and the great elements arose in combination, together with other related seminal elements, forming a lump. At this stage it is said that consciousness has already settled, establishing the continuity of rebirth. This is what is called the kalala stage]. |

| 26 | For a discussion of the early Buddhist sūtras translated into Chinese on conception and fetal development, see (Kritzer 2008, pp. 73–91; Li 2006, pp. 517–90). |

| 27 | It is also worth noting that chu 出 (exiting) and ru 入 (entering) as a pair often euphemistically refers to birth and death in Classical Chinese. The correlation between the Three Siddhi and three parts of the human body can be found in earlier scriptures. In the Suxidi jieluo jing 蘇悉地羯羅經 [Tantra for Wondrous Achievement in All Endeavors], different levels of the body—the navel, the heart, and the head—at which the practitioner holds the ritual vessel correspond to the Three Siddhi: Yiyong liangshou peng ejiaqi, dingdai gongyang, wei shangxidi. Zhiyu xinjian, wei zhongxidi. Zhiyu qijian, wei xiaxidi 以用兩手捧閼伽器。頂戴供養。爲上悉地。置於心間。爲中悉地。置於臍間。爲下悉地 [Taking the arghya vessel with both hands: raising it above the head in offering constitutes the Upper Siddhi; placing it before the heart constitutes the Middle Siddhi; placing it at the navel constitutes the Lower Siddhi]. In Śubhakarasiṃha (Shanwuwei 善無畏) trans., Suxidi jieluo jing 蘇悉地羯羅經 [Tantra for Wondrous Achievement in All Endeavors], T. 893_.18.0615a28-a29. A similar passage to the one found in T. 906 could be found in the Qingjing fashen piluzhena xindi famen chengjiu yique tuoluoni sanzhong xidi 清淨法身毘盧遮那心地法門成就一切陀羅尼三種悉地 [Accomplishing All Dhāraṇīs and the Three Siddhis through the Dharma-Gate of the Mental Ground of Vairocana, the Pure Dharma-Body]: Congxin zhiding weishang, congqi zhixin weizhong, congshi zhiqi weixia 從心至頂為上,從臍至心為中,從是至臍為下 [From the heart up to the crown is the Upper Siddhi; from the navel up to the heart is the Middle Siddhi; from there down to the navel is the Lower Siddhi] (T. 899_.18.0779c23-c24). |

| 28 | The idea of growing a Buddha body—or the use of the embryogenetic process as a metaphor for the path to enlightenment—can be found in both exoteric and esoteric Buddhist traditions. In particular, as Kevin Buckelew points out, the concept of “the embryo of sagehood” or “growing the embryo” as a parallel to the Bodhisattva path originated in the Ren Wang Jing 仁王經 [Sūtra for Humane Kings]—an important text that gained new currency in Tang esoteric Buddhism with the new translation by Amoghavajra (Buckelew 2018, pp. 371–82). Buckelew’s article also delves into Medieval Chinese exegetic discourse on the embryo of sagehood by thinkers such as Zhiyi 智顗 and Guifeng Zongmi 圭峰宗密. For example, Zongmi’s commentary on the Yuanjue Jing 圆觉经 [Sūtra of Perfect Enlightenment] includes a passage that explains how upon the instantaneous thought of awakening causes the storehouse consciousness to be impregnated with the seed of sagehood—just like the beginning of pregnancy: Dan yinian juewu ci yuanmiaoxin, ji zangshi zhong yi xun cheng shengzhong, yuan wei zhangxian yuwai, gu ru shitai ye 但一念覺悟此圓妙心,即藏識中已熏成聖種,緣未彰現於外,故如始胎也 [With but a single moment of awakening to this perfect, wondrous mind, the storehouse consciousness is already perfumed with the seed of sagehood; yet because the conditions have not outwardly appeared, it is likened to the earliest stage of the embryo], in Zongmi 宗密, Yuanjue jing daochang xiuzhengyi 圓覺經道場修證儀 [Manual of Procedures for the Cultivation of Realization of Ritual Practice According to the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment], X. 74, no.1475_p.398b7-8. As Buckelew illuminates, “all these medieval exegetes sought to explain how buddhahood is born” (Buckelew 2018, p. 391). Moreover, as Michael Radich explains, the important soteriological concept of tathāgatagarbha (Buddha nature) from the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra also contains the meaning of the “matrix, or womb (garbha) for the production of new buddhahood”—located in the very body of the practitioner (Radich 2015, p. 167). Esoteric Buddhism further foregrounds the matrix of Buddhahood in the Garbhadhātu (Womb World) Mandala, the working of which is “often likened to the manner in which the lotus seed grows and brings forth its flowers”(Grotenhuis 1998, p. 59). Later in Japanese Shingon Buddhism, the idea of embryonic or fetal Buddhahood became further fleshed out and systemized into a five-stage gestational process whereby the practitioner gradually attains the enlightened body of Mahāvairocana. This embryogenetic vision of liberation was first formulated in Kakuban’s Gorin kujimyō himitsushaku 五輪九字明秘密釋 [Commentary on the Secrets of the Five Cakras and Nine Syllables], which as many scholars have demonstrated, were much inspired by the Three Siddhi sūtras. See for example, (Dolce 2016). |

| 29 | Yingcong Chongzhensi suizhenshen gongyangdaoju ji enci jinyinqiwu baohan deng bing xinenci dao jinyinbaoqi yiwuzhang 應從重真寺隨真身供養道具及恩賜金銀器物寶函等並新恩賜到金銀寶器衣物帳 [Inventory of ritual implements, along with the gold and silver vessels, caskets, and other items previosuly offered to the Chongzhen Monastery, was to accompany the True Body relic together with the newly bestowed gold and silver treasures, garments, and textiles], dated 874 (Shanxi Sheng kaogu yanjiusuo 2007, pp. 227–31). |

| 30 | Liu Xu 劉昫 and Zhang Zhaoyuan 張昭遠, Jiu tangshu 舊唐書 [Old Book of the Tang], juan 51, vol. 31 (Shanghai: Shangwu yinshu guan, 1930–1937), pp. 6–7. |

| 31 | The soul-summoning ritual is an ancient mortuary rite to recall the wandering hun 魂 spirit of the deceased, and a sartorial item is often used as a material medium to host the returned spirit. At the same time, there was much anxiety around the ritual propriety of the “soul-summoning burial” (zhaohun zang 招魂葬)—namely burying the deceased’s garments used in a soul-summoning ceremony, as it was believed that the heaven-bound hun spirit attached to the clothing could be trapped in the underground coffins. Du You 杜佑, Zhaohun zangyi 招魂葬議 [Treatise on the soul-summoning burial]. Tongdian 通典 [Comprehensive statutes], juan 113, vol. 3 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1988), pp. 2701–4. |

| 32 | Kongzi yue: “Zhi si er zhi si zhi, bu ren er bu ke wei ye; zhi si er zhi sheng zhi, bu zhi er bu ke wei ye. Shi gu, zhu bu cheng yong, wa bu cheng wei, mu bu cheng zhuo, qinse zhang er bu ping, yusheng bei er bu he, you zhongqing er wu sunju, qi yue mingqi, shenming zhi ye.” 孔子曰:「之死而致死之,不仁而不可為也;之死而致生之,不知而不可為也。是故,竹不成用,瓦不成味,木不成斲,琴瑟張而不平,竽笙備而不和,有鐘磬而無簨虡,其曰明器,神明之也。」 [Confucius said: “To regard the dead simply as dead is unbenevolent and should not be done; to regard the dead as if still alive is unwise and should not be done. Therefore, bamboo (implements) are fashioned but not for use; pottery is made but not for eating; wood is shaped but not fit for carving; zithers and lutes are strung but not tuned; flutes and reed-pipes are set but not in harmony; there are bells and chimes, but without their stands. These are called spirit articles—they are made for the spirits.” Tangong 檀弓 [Sandalwood Bows], Liji 禮記 [Book of Rites]. In Sun Xidan 孫希旦, Liji jijie 禮記集解 [Collected Explanations to the Book of Rites], juan 9, vol.1 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1989), p. 216. By “spiritual article,” I am borrowing Jeehee Hong’s interpretation of mingqi as funerary articles that were “believed to carry a spiritual aspect (as implied in ming 明 or ming 冥) embodying the basic quality of otherworldliness (Hong 2015, p. 162). |

| 33 | Zhi ru Shangna biqiu, taiyi beiti 至如商那比丘,胎衣被體 [In the case of the monk Śāṇavāsa, his body is covered in the embryonic coat], in Dao Xuan 道宣, Shimen zhangfu yi 釋門章服儀 [Protocols of monastic robes in the Buddhist Tradition], T. 1894_.45.0837a01. This passage not only mentions Śāṇa’s “embryonic coat,” but also highlights the inextricable connections between one’s clothing, body, and mind, as all transformations—including one’s garments and body—all stem from the one single mind. In this way, Śāṇa’s “embryonic coat” is a karmic reward that sartorially and corporeally manifest his spiritual cultivation and virtue (T. 1894_.45.0836c29-T. 1894_.45.0837a08). |

| 34 | Bao tai (shang “bujiao fan”, guwen zuo “bao”, xiangxing zi ye, wei shi taiyi. Cai Yong “Shijing” jia “rou” zuo “bao”. “Shuowen” yun: “er sheng yi ye.” Kong zhu “Shangshu” yun: “guo ye.” “Zhuangzi” yun: “bao zhe, furu yi ye.” Su yin “pubao fan”, fei ye. Xia “talai fan”. “Guangya”: “furen yun er yue wei tai.” “Shuowen” yun: “fu yun er yue ye.” “Cangjie pian” yun: “nüren huairen wei sheng yue tai.” Cong “rou”, “tai” sheng ye.) 胞胎(上「補交反」,古文作「包」,象形字也,為是胎衣。蔡邕《石經》加「肉」作「胞」。《說文》云:「兒生衣也。」孔注《尚書》云:「裹也。」《莊子》云:「胞者,腹肉衣也。」俗音「普包反」,非也。下「他來反」。《廣雅》:「婦人孕二月為胎。」《說文》云:「婦孕二月也。」《蒼頡篇》云:「女人懷妊未生曰胎。」從「肉」,「台」聲也) [Bao 胞: Fanqie spelling bu-jiao bao. In ancient script it is written as bao 包, a pictograph meaning “fetal membrane.” In Cai Yong’s Stone Classics, the graph is written with the “flesh” radical added, forming bao 胞. The Shuowen explains: “Bao is the garment in which a child is born.” Kong’s annotated version of the Shangshu glosses it as “to wrap.” The Zhuangzi says: “The bao is the fleshy covering of the belly.” The common reading pu-bao is incorrect. Tai 胎: Fanqie spelling ta-lai tai. The Guangya says: “When a woman is two months pregnant, the embryo is called tai.” The Shuowen says: “(The embryo is) when a woman is two months pregnant.” The Cangjie pian says: “When a woman is pregnant but has not yet given birth it is called tai.” Written with the “flesh” radical and the phonetic element “tai.” Huilin 慧琳, Yiqiejing yinyi 一切經音義 [The Sounds and Meanings of all the words in the Scriptures], T. 2128_.54.0322a25-b02. |

| 35 | Wang Chong 王充, Lunheng 論衡 [Discussive Weighing], juan 23, vol. 4 (Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1934), p. 23. |

| 36 | Another miniature kāṣāya, the hinagata gojō kesa 雛形五条袈裟 [miniature five-columned kāṣāya] (catalog no. 49), also dated to the 9–10th century, is found in Enryakuji kanji 延暦寺. An accompanying label records that the kesa to belong to Soō Oshō 相応和尚 (831–918), a Japanese Tendai Buddhist monk (Kyōto Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan 2005, p. 316). The Enryakuji kesa points to a connection to the Famensi miniature kāṣāya and Tang esoteric Buddhist practice and might have born similar symbolic associations. The embryological significance could perhaps also explain the practice of depositing miniature kesa inside Buddhist statues as tainai nōnyūhin 胎内納入品 (inner deposit) in later surviving Japanese examples from the 13th–14th centuries. |

| 37 | The lotus motif on the “meditation mat” likely represents the setting for huasheng 化生 (born miraculously in a reward body), as these newborn babes from lotuses are frequently seen in Medieval Buddhist art such as in the Mogao Grottoes murals, especially in Amitâbha’s Western Pure Land transformation tableaux. |

| 38 | It would not be surprising if the statue was made with the anticipatory postmortem salvation of the emperor in mind, especially considering how the timing of the translations of the relic to the imperial palace often coincided with the imminent death of the Tang emperors. |

| 39 | The famous historical account can be found in: Li Keji jin Tan Bainian qu, shengci yuangan, ting zhi mo bu lei xia. You jiao shuqianren zuo Tan Bainian dui. Qu neiku zhenbao diaocheng shoushi. Hua babai pi guanxi zuo yulong bolan wen, yi wei diyi. Meiyiwu er zhucui mandi 李可及進《歎百年》曲,聲詞怨感,聽之莫不淚下。又教數千人作嘆百年隊。取內庫珍寶雕成首飾。畫八百疋官絁作魚龍波浪文,以為地衣。每一舞而珠翠滿地 [Li Keji presented the song Elegy of the Century, whose melodies and verses were so charged with sorrow and emotion that none who heard it failed to weep. He then trained several thousand performers to form a Elegy of the Century troupe. Precious jewels were take from the imperial treasury and carved into accessories, while eight hundred bolts of official silk were painted with designs of makara and wave patterns to serve as floor carpets. At every dance, jeweled ornaments scattered to cover the entire ground]. In Su E 蘇鶚, Duyang Zabian 杜陽雜編 [Miscellaneous compilation of Duyang], juan 3 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1958), p. 57; Tongchang Gongzhu chusang hou, di yu Shufei sinian buyi. Keji nai wei Tan Bainian Wuqu. Wuren zhucui shengshi zhe shubai ren, hua yulong diyi, yong guanxi wuqian pi. Quzhong yueque, zhuji fudi, ciyu qice, wenzhe tiliu 同昌公主除喪後,帝與淑妃思念不已。可及乃為《歎百年舞曲》。舞人珠翠盛飾者數百人,畫魚龍地衣,用官絁五千匹。曲終樂闋,珠璣覆地,詞語淒惻,聞者涕流 [After the mourning for Princess Tongchang was completed, the emperor and Consort Shu could not cease their grief. Li Keji thereupon created the Elegy of the Century Dance. Hundreds of dancers, lavishly adorned with pearl-and-kingfisher ornaments, performed upon floor cloths painted with makara motifs, fashioned from five thousand bolts of official silk. When the music concluded, pearls and jewels lay scattered across the ground; the verses were mournful and full of pathos, and all who heard them were moved to tears]. In Liu and Zhang, Jiu tangshu 舊唐書 [Old Book of the Tang], vol. 31, juan 181 (Shanghai: Shangwu yinshu ban, 1930–1937), pp. 18–19. |

| 40 | The connection between the legendary funerary performance and the Bodhisattva statue’s figuration—differing from conventional depictions of offering bodhisattvas in Medieval Buddhist art—is most evident in the overwhelming presence of luminescent pearls that adorn the figure’s entire body. The pearls not only correspond well with the description of the dancers bedecked in jewels at Princess Tongchang’s funeral, but also evoke the poetic image of “pearls and jewels covering the ground” (zhuji fudi 珠璣覆地) at the close of the performance—a metaphor for the audience’s sorrowful tears. Moreover, it is difficult to overlook the goddess-like aspect of the figure’s coiffure, sartorial representation, and appearance, as previous scholars have pointed out. I think that the statue’s prominent femininity could also be a visual reference to the ethereal performers at the funeral. |

References

Primary Source

Amoghavajra (Bukong 不空). Jingangdingjing yujia wenshu shili pusafa yipin 金剛頂經瑜伽文殊師利菩薩法一品 [A Chapter of the Mañjuśrī Method from the Vajraśekhara Yoga], T. 1171.Amoghavajra (Bukong 不空). Jingangding chaosheng sanjie jingshuo wenshu wuzi zhenyan shengxiang 金剛頂超勝三界經說文殊五字眞言勝相 [Victorious Aspect of Mañjuśrīʼs Five-Syllable Mantra, from the Three Worlds Conqueror Scripture of the Vajraśekhara Yoga], T. 1172.Bodhiruci (Putiliuzhi 菩提流支). Yizi foding lunwang jing 一字佛頂輪王經 [Sūtra of the One-Syllable Buddha-Crown Wheel King], T. 951.Daoshi 道示. Fayuan zhulin 法苑珠林 [Grove of Jewels in the Garden of the Dharma], T. 2122.Dao Xuan 道宣. Shimen zhangfu yi 釋門章服儀 [Protocols of Monastic Robes in the Buddhist Tradition], T. 1894.Du You 杜佑. Tongdian 通典 [Comprehensive Statutes], 5 vols. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1988.Dharmasena (Damoqinuo 達磨栖那). Damiao jingang da ganlu junnali yanman chisheng foding jing 大妙金剛大甘露軍拏利焰鬘熾盛佛頂經 [The Sutra of the (Yiqie) Foding (zhuanlun wang), Who Enters the Violently Blazing [samādhi] of the Great Wonderful King of Wisdom Amṛta Kuṇḍalī], T. 965.Enchin 円珍. Ketsuji sanshu shijjihō 決示三種悉地法. [An Explanation of the Three Siddhi Methods] Accessed through Kyoto University digital archive: https://rmda.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/item/rb00019033#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&r=0&xywh=-3968%2C-224%2C13950%2C4462 (accessed on 8 September 2025).Huilin 慧琳. Yiqiejing yinyi 一切經音義 [The Sounds and Meanings of All the Words in the Scriptures], T. 2128.Liu, Xu 劉昫 and Zhang Zhaoyuan 張昭遠. Jiu tangshu 舊唐書 [Old Book of the Tang], 36 vols. Shanghai: Shangwu yinshu ban, 1930–1937.Jōgyo 常暁. Jōgyō oshō shōrai mokuroku 常暁和尚請来目録 [Catalogue of Documents Brought by the Reverend Jōgyō], T. 2163.Qingjing fashen piluzhena xindi famen chengjiu yique tuoluoni sanzhong xidi 清淨法身毘盧遮那心地法門成就一切陀羅尼三種悉地 [Accomplishing All Dhāraṇīs and the Three Siddhis through the Dharma-Gate of the Mental Ground of Vairocana, the Pure Dharma-Body], T. 899.Sima Guang 司馬光. Zizhi tongjian 資治通鑑 [Comprehensive Mirror to Aid in Government], 20 vols. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1956.Su E 蘇鶚. Duyang zabian 杜陽雜編 [Miscellaneous Compilation of Duyang]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1958.Sun Xidan 孫希旦. Liji jijie 禮記集解 [Collected Explanations to the Book of Rites], 3 vols. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1989.Śubhakarasiṃha (Shanwuwei 善無畏). Suxidi jieluo jing 蘇悉地羯囉經 [Tantra for Wondrous Achievement in All Endeavors], T. 893.Śubhakarasiṃha (Shanwuwei 善無畏). Sanzhong xidi podiyu zhuanyezhang chusanjie mimi tuoluoni fa 三種悉地破地獄轉業障出三界祕密陀羅尼法 [Secret Dhāraṇī Method of Three Attainments which Destroy Hell and Reverse Karmic Hindrances in the Three Worlds], T. 905.Śubhakarasiṃha (Shanwuwei 善無畏). Foding zunshengxin podiyu zhuanyezhang chusanjie mimisanshen foguo sanzhong xidi zhenyan yigui 佛頂尊勝心破地獄轉業障出三界祕密三身佛果三種悉地真言儀軌 [Manual of the Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Mantras for the Destruction of Hells, Transformation of Karmic Hindrances, and Exiting the Three Realms: The Secret Results of the Three Bodies and Three Attainments], T. 906.Śubhakarasiṃha (Shanwuwei 善無畏). Foding zunshengxin podiyu zhuanyezhang chusanjie mimi tuoluoni 佛頂尊勝心破地獄轉業障出三界祕密陀羅尼 [The Secret Dhāraṇī Method of the Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Mantras, Which Shatters the Hells, Transforms Karmic Obstacles, and Enables Escape from the Three Realms], T. 907.Vajrabodhi (Jingangzhi 金剛智). Jingangfeng louge yiqie yujia yuqi jing 金剛峯樓閣一切瑜伽瑜祇經 [Pavilion of Vajra Peak and all its Yogas and Yogins Sūtra], T. 867Vajrabodhi (Jingangzhi 金剛智). Jingangdingjing manshu shili pusa wuzi xin tuoluoni pin 金剛頂經曼殊室利菩薩五字心陀羅尼品 [Five-Syllable Essential Dhāraṇī of Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī from the Vajraśekhara Yoga], T. 1173.Wang Chong 王充. Lunheng 論衡 [Discussive Weighing], 4 vols. Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1934.Xuanzang 玄奘. Yujia shidi lun 瑜伽師地論 [Discourse on the Stages of Concentration Practice], T. 1579.Xuanzang 玄奘. Datang xiyu Ji 大唐西域記 [Record of Travels to Western Lands], T. 2087.Zongmi 宗密. Yuanjue jing daochang xiuzhengyi 圓覺經道場修證儀 [Manual of Procedures for the Cultivation of Realization of Ritual Practice According to the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment], X. 1475.Secondary Sources

- Buckelew, Kevin. 2018. Pregnant Metaphor: Embryology, Embodiment, and the Ends of Figurative Imagery in Chinese Buddhism. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 78: 371–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jinhua. 1998a. The Construction of Early Tendai Esoteric Buddhism: The Japanese Provenance of Saichō’s Transmission Documents and Three Esoteric Buddhist Apocrypha Attributed to Śubhākarasiṁha. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 21/1: 21–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jinhua. 1998b. The Formation of Early Esoteric Buddhism in Japan: A Study of the Three Japanese Esoteric Apocrypha. Ph.D. dissertation, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Dolce, Lucia. 2016. The Embryonic Generation of the Perfect Body: Ritual Embryology from Japanese Tantric Sources. In Transforming the Void: Embryological Discourse and Reproductive Imagery in East Asian Religions. Edited by Anna Andreeva and Dominic Steavu. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 253–310. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Chengyong 葛承雍. 2010. Famensi tang ‘peng zhenshen pusa’ yishu yuanxing zaitan 法門寺唐 ‘捧真身菩薩’ 藝術原型再探 [A Reexamination of the Artistic Prototype of the Tang ‘Bodhisattva Holding the True Body’ at the Famen Monastery]. Kaogu yu wenwu 考古與文物 [Archaeology and Cultural Relics] 1: 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Grotenhuis, Elizabeth Ten. 1998. Japanese Mandalas: Representations of Sacred Geography. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Jeehee. 2015. Mechanism of Life for the Netherworld: Transformations of Mingqi in Middle-Period China. Journal of Chinese Religions 43: 161–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritzer, Robert. 2008. Life in the Womb: Conception and Gestation in Buddhist Scripture and Classical Indian Medical Literature. In Imagining the Fetus. Edited by Vanessa R. Sasson and Jane Marie Law. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kyōto Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan 京都国立博物館 [Kyoto National Museum]. 2005. Saichō to Tendai no kokuhō: Tendaishū kaishū 1200-nen kinen 最澄と天台の国宝: 天台宗開宗一二〇〇記念 [Saichō and the National Treasures of Tendai: Commemorating the 1200th Anniversary of the Founding of the Tendai Schoo]. Tokyo: Yomiuri Shinbunsha. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, I-mann. 2006. The Famensi Reliquary Deposit: Icons of Esoteric Buddhism in Ninth-Century China. Ph.D. dissertation, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- La Vallée Poussin, Louis de. 1988. Abhidharmakośabhāṣyam. Berkeley: Asian Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Qinpu 李勤璞. 2006. Yindu qiri zhutailun jiqi zai hanyi de yige biaoxian (shangpian) 印度七日住胎論及其在漢醫的一個表現 (上篇) [The Indian Theory of Embryonic Development and Its Expression in Chinese Medicine (Part I)]. Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi yuyanyanjiusuo jikan 中央研究院歷史語言研究所集刊 [Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica] 77: 517–90. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Zi 梁子. 1994. Famensi chutu pengzhenshen pusa mantuoluo zaoxiang kao 法門寺出土捧真身菩薩曼茶羅造像考 [A Study of the Mandala Imagery in the Bodhisattva Holding up the True Body Statue Excavated at Famen Temple]. Gugong wenwu yuekan 故宮文物月刊 [National Palace Museum Monthly of Chinese Art] 134: 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Weicheng. 2010. Bei shentihua de sheli fozhi: Cong famensi digong de zhenshen sheli tan zhongguo sheli yizang yu muzang 被身體化的舍利佛指:從法門寺地宮的真身舍利談中國舍利瘞藏與墓葬 [The Corporealization of the Buddha’s Relic Finger: The True-Body Relic in the Famen Temple Crypt and the Practice of Relic Interment in China]. Diancang 典藏 [Collection] 218: 162–69. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Zhao 羅炤. 2014. Famensita digong jiqi cangpin de jige wenti 法門寺塔地宮及其藏品的幾個問題 [Several Issues Concerning the Crypt of the Famen Temple Pagoda and Its Collections]. Shi ku si yan jiu 石窟寺研究 [Research on Cave Temples] 1: 121–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Jianfu 呂建福. 2008. Mijiao lunkao 密教論考 [Essays on Esoteric Buddhism]. Zongjiao wenhua chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Mita, Takaaki 見田隆鑑. 2005. Hōmonji chikyū shutsudo shinshin hōkan ni arawasareru hachidai myōō ni tsuite 法門寺地宮出土の真身宝函に表される八大明王について [An Iconographical Study of Eight Myo’o Carved on the Reliquary, Discovered from the Underground Crypt in the Famen Temple]. Nagoyadaigaku hakubutsukan hōkoku 名古屋大学博物館報告 [Nagoya University Museum Bulletin] 21: 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Orzech, Charles D. 2011. After Amoghavajra: Esoteric Buddhism in the Late Tang. In Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia. Edited by Charles D. Orzech, Henrik Hjort Sorensen and Richard Karl Payne. Leiden and Boston: Brill, p. 327. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Changhwan. 2007. The Sautrāntika Theory of Seeds (bīja) Revisited: With Special Reference to the Ideological Continuity Between Vasubandhu’s Theory of Seeds and Its Sárīlāta /Dārstāntika Precedents. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Radich, Michael. 2015. The Mahaparinirvana-Mahasutra and the Emergence of Tathagatagarbha Doctrine. Hamburg: Hamburg University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Tansen. 2014. Relic Worship at the Famen Temple and the Buddhist World of the Tang Dynasty. In Secrets of the Fallen Pagoda. Edited by Eugene Yuejin Wang, Tansen Sen, Shen Chong, Alan Kan, Shuyi Carvalho, Pedro de Moura Chan, Lai-Pik Cheong and Conan Cheong. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Shanxi Sheng kaogu yanjiusuo 山西省考古研究所 [Shanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology]. 2007. Famensi kaogu fajue baogao 法門寺考古發掘報告 [Archaeological Excavation Report of the Famen Temple], 1st ed. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Sharf, Robert H. 2011. The Buddha’s Finger Bones at Famensi and the Art of Chinese Esoteric Buddhism. The Art Bulletin 93: 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, Yeoung Shin. 2025. The Origins and Symbolism of Vaiśravana Iconography and the Impact of the Royal Image as Donor and Protector. Religions 16: 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Pushi 唐普式. 1999. Renqing Famensi ta digong de tangmi mantuoluo 認清法門寺塔地宮的唐密曼陀羅 [Recognizing the Tang Esoteric Mandalas in the Underground Crypt of the Famen Temple Pagoda]. In Famensi wenhua yanjiu (fojiaojuan) 法門寺文化研究(佛教卷) [Famen Temple Cultural Studies (Buddhism)]. Beijing: Zhongguo sanxia chubanshe, pp. 66–67. [Google Scholar]

- Twitchett, Denis Crispin, and John King Fairbank. 1978. The Cambridge History of China. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Eugene. 2005. Of the True Body: The Famen Monastery Relics and Corporeal Transformation in Tang Imperial Culture. In Body and Face in Chinese Visual Culture. Edited by Wu Hung and Katherine R. Tsiang. Boston: Harvard University Asia Center, pp. 71–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Eugene. 2014. The Emperor’s New Body. In Secrets of the Fallen Pagoda: The Famen Temple and Tang Court Culture. Edited by Eugene Yuejin Wang, Tansen Sen, Shen Chong, Alan Kan, Shuyi Carvalho, Pedro de Moura Chan, Lai-Pik Cheong and Conan Cheong. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Limin 吳立民, and Jinke Han 韓金科. 1998. Famensi digong Tangmi mantuoluo zhi yanjiu 法門寺地宮唐密曼荼羅之硏究 [A Study of Tang Esoteric Mandalas from the Underground Crypt of Famen Temple], 1st ed. Xianggang: Zhongguo fojiao wenhua chuban youxian gongsi. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Limin 吳立民, and Jinke Han 韓金科. 2000. Famensi tangdai digong pengzhenshen pusa mantuoluo 法門寺唐代地宮捧真身菩薩曼荼羅 [The Tang-Dynasty Bodhisattva Holding up the True Body Mandala from the Famen Temple Underground Crypt]. Dongnan wenhua 東南文化 [Southeast Culture] 134: 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Yoritomi, Motohiro 頼富本宏. 2000. Chūgoku hōmonji shutsudo no mikkyōkei ihin 中国・法門寺出土の密教系遺品 [Esoteric Buddhist Relics Excavated from Famen Temple, China]. In Bukkyo bunka no shosō: Takagi Shingen Hakushi koki kinen ronshū 仏教文化の諸相: 高木訷元博士古稀記念論集 [Aspects of Buddhist Culture: Commemorative Volume for Dr. Takagi Shingen’s Seventieth Birthday]. Edited by Department of Buddhist Studies, Koyasan University 高野山大学仏教学研究室. Tokyō: Sankibō Busshorin, pp. 305–328. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Chao 趙超. 2004. Yun xiang yi shang: Zhongguo fu shi de kao gu wen wu yan jiu 雲想衣裳: 中國服飾的考古文物硏究 [Clothes Like Clouds: Archaeological and Art Historical Studies of Chinese Dress], 1st ed. Chengdu: Sichuan chu ban ji tuan. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, X. How to Grow a Buddha Body?—A Case Study of the “Bodhisattva Holding Up the True Body” (Peng zhenshen pusa 捧真身菩薩) Statue at the Famen Temple. Religions 2025, 16, 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101235

Wu X. How to Grow a Buddha Body?—A Case Study of the “Bodhisattva Holding Up the True Body” (Peng zhenshen pusa 捧真身菩薩) Statue at the Famen Temple. Religions. 2025; 16(10):1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101235

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Xiaolu. 2025. "How to Grow a Buddha Body?—A Case Study of the “Bodhisattva Holding Up the True Body” (Peng zhenshen pusa 捧真身菩薩) Statue at the Famen Temple" Religions 16, no. 10: 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101235

APA StyleWu, X. (2025). How to Grow a Buddha Body?—A Case Study of the “Bodhisattva Holding Up the True Body” (Peng zhenshen pusa 捧真身菩薩) Statue at the Famen Temple. Religions, 16(10), 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101235