Abstract

This study investigates how religious rhetoric and popular mobilisation contributed to the preservation and propagation of Daoist traditions at the mountain Maoshan 茅山 from late Qing to Republican China (1864–1937), focusing particularly on the corpus of religious texts related to Maoshan and its tutelary gods, the Three Mao Lords 三茅真君. Through a detailed analysis of primary sources, including editions of the Maoshan Gazetteer, liturgical manuals such as the scripture (jing 經), litany (chan 懺), and performative texts such as the precious scroll (baojuan 寶卷) of the Three Mao Lords, this study identifies six key rhetoric strategies employed by Maoshan Daoists, using the acronym IMPACT: (1) Incorporation: Appending miracle tales (lingyan ji 靈驗記) and divine medicine (xianfang 仙方) to address immediate and practical needs of contemporary society; (2) Memory: Preserving doctrinal continuity while invoking cultural nostalgia to reinforce connections to traditional values and heritage; (3) Performance: Collaborating with professional storytellers to disseminate vernacularized texts through oral performances, thereby reaching broader audiences including the illiterate. (4) Abridgment: Condensing lengthy texts into concise and accessible formats; (5) Canonization: Elevating the divine status of deities through spirit-writing, thereby enhancing their religious authority; (6) Translation: Rendering classical texts into vernacular language for broader accessibility. Building upon J.L. Austin’s speech act theory, this study reconceptualizes these textual innovations as a form of “text acts”, arguing that Maoshan texts did not merely transmit religious doctrine but actively shaped pilgrimages and devotional practices through their illocutionary and perlocutionary force. Additionally, this study also highlights the crucial role of social networks, particularly the efforts of key individuals such as Zhang Hefeng 張鶴峰 (fl. 1860–1864), Long Zehou 龍澤厚 (1860–1945), Jiang Daomin 江導岷 (1867–1939), Wang Yiting 王一亭 (1867–1938) and Teng Ruizhi 滕瑞芝 (fl. 1920–1947) who facilitated the reconstruction, reprinting and dissemination of these texts. Furthermore, this study considers pilgrimages to Maoshan as a form of popular mobilisation and resistance to anti-clerical and anti-superstition campaigns, illustrating how, against all odds, Maoshan emerged as a site where religious devotion and economic activity coalesced to sustain the local communities. Ultimately, despite the challenges identified in applying speech act theory to textual practices, the findings conclude that the survival and revival of Daoist traditions at Maoshan was not only a result of textual retention and innovation but also a testament to how religious rhetoric, when coupled with strategic social engagement, can fuel popular mobilisation, reignite collective devotion, and reshape cultural landscapes in transformative ways.

1. Introduction

The pilgrimage to the mountain Maoshan 茅山, a historical site in Daoist tradition and revered as the “Eighth Grotto-Heaven and the First Blessed Land” 第八洞天,第一福地 was subject to severe destruction and extensive prohibitions in the nineteenth century. The social and political climate of the late Qing dynasty, particularly the aftermath of the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864), heightened the government’s sensitivity towards large gatherings and the formation of alliances, which were often perceived as potential threats to state security. Particularly under the governance of Tan Junpei 譚均培 (1828–1894) (J. Wang 2012), the inspector-official of Jiangsu province since 1879, pilgrimage practices were harshly criticized and ultimately banned. Official constraints caused a significant decline in pilgrim traffic, which remained at reduced levels for over two decades.

With the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912 following the 1911 Revolution (xinhai geming 辛亥革命), the political landscape underwent a significant transformation. The social atmosphere began to shift, allowing for the gradual revival of pilgrimage practices. Despite the severe damage inflicted on many temples and monasteries during the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864) and the ensuing chaos of the Warlord Period (1917–1928), Maoshan began to experience a period of restoration and rebuilding. Innovative strategies emerged to attract pilgrims, signaling a revival of religious practices. When the Nationalist Party established a unified government in Nanjing in 1927, Maoshan saw a renewed surge of pilgrims, driven by relative stability, economic growth, and ambitious government projects that improved transportation and supported a market-led economy. This period, often referred to as the Nanjing Decade (Nanjing shinian 南京十年) or the Golden Decade (huangjin shinian 黃金十年), lasted until the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937.

This study examines how the Maoshan pilgrimage was revived between the aftermath of the Taiping Rebellion (1864) and the onset of the Sino-Japanese War (1937),1 focusing on the textual innovations, social networks and religious economy that played a crucial role in this resurgence. This research aims to examine how pilgrimages, a suppressed religious practice since 1880, managed to not only survive but also adapt and thrive in a changing socio-political context. While previous studies have documented the suppression of religious practices during the late Qing period, there have been fewer studies focusing on the subsequent revival and the mechanisms that facilitated it in Republican China. Recent scholarship on Chinese religions has increasingly focused on the genre of precious scrolls (baojuan 寶卷), a form of vernacular religious literature (Overmyer 1999). Scholars have recognized the close connection between narratives in precious scrolls and pilgrimage, noting how these texts reflect and inspire the devotional journeys of their audiences. In the study of the Maoshan pilgrimage, the work of Vincent Goossaert and Rostislav Berezkin combines historical analysis and fieldwork to explore the modern history of Maoshan cults (Goossaert and Berezkin 2012). Their research offers an in-depth understanding of the historical context by introducing a variety of texts, with the second part particularly focused on the content and performance of precious scrolls in contemporary local societies. Expanding on the analysis of precious scrolls, another recent study on Taishan Niangniang 泰山娘娘 by Ma Zhujun 馬竹君 focuses on the gender dynamics in the interaction between devotees and the deity (Ma 2023). Ma considers that prescriptive materials like precious scrolls provide limited evidence regarding the actual intentions and motivations of pilgrims in Taishan, thus inviting further exploration into the roles of these texts in shaping religious practices. Similarly, Noga Ganany’s work examines how “origin narratives” are deeply intertwined with the theme of travel since late Ming China, both literal and metaphysical (Ganany 2018, pp. 327–28). Ganany has shown how these journeys are not only central to the narrative structure but also serve as blueprints for pilgrimages, inspiring readers to follow the paths of these legendary figures. These studies thereby suggest that the larger question of “text acts” in late imperial China merits a longue durée investigation. For example, one recent work by Adam Yuet Chau 周越 applies the concept of “text acts” to analyze temple inscriptions from three temple sites in Shaanbei 陝北, north-central China, suggesting that certain texts exert influence not merely through their semantic content but through their material presence and the effects they produce on audiences, which he refers to as “textographic fetishes” (Chau 2023). Chau argues that these texts act upon their viewers by generating feelings of awe, submission, or recognition. Together, these studies demonstrate the crucial roles of religious texts, from shaping gendered interactions and inspiring pilgrimages to generating embodied responses. They highlight their centrality in understanding religious rhetoric and practice in Chinese traditions.

This study thus aims to situate Maoshan texts within broader scholarly discussions by expanding the exploration of “text acts” beyond temple inscriptions. It examines religious texts as active instruments that perform actions, evoke responses, and shape devotional practices. By focusing on the textual strategies of Maoshan Daoists during the 1920s, this study explores their performative and transformative impacts on Daoist communities, thereby contributing to a broader application of the concept of “text acts” through the lens of J.L. Austin’s seminal work on speech acts (Austin 1962) and Quentin Skinner’s discussion on “illocutionary force” (Skinner 2002, pp. 98, 108–9, 133). While the theories of Austin and Skinner primarily focus on spoken language, written texts, particularly in religious contexts, possess similar performative dimensions that deserve further exploration. Building on Webb Keane’s work on religious language (Keane 1997), which examines the interconnection between text, context, intentionality, and agency, this study extends these theories to the concept of “religious rhetoric”. Religious rhetoric, in this context, is defined as encompassing the persuasive and performative dimensions of religious communication, presenting texts as active instruments that not only convey meaning but actively inspire action, shape belief, and sustain religious communities. The concept of religious rhetoric has not been extensively explored in the context of Chinese religious traditions. However, it provides a valuable lens for analyzing the textual strategies of religious specialists. For instance, Philip Clart’s study of the Guanyin’s Lotus Sutra of the Marvellous Dao (Guanyin miaodao lianhua jing 觀音妙道蓮華經) revealed through spirit-writing at a Taiwanese phoenix hall highlights how such texts employ appropriative strategies to integrate diverse doctrinal elements into cohesive frameworks that transcend traditional sectarian boundaries (Clart 2011). In this case, the scripture re-anchors Guanyin’s devotionalism within a syncretic framework of Dao cultivation, illustrating the rhetorical potential of texts to negotiate and transform religious practice. Another study by Bony Schachter on the Scripture of the Jade Sovereign (Yuhuangjing 玉皇經) illustrates how religious rhetoric integrates diverse Daoist and Buddhist textual materials into a coherent soteriological framework (Schachter 2015). Schachter highlights the compilers’ intentionality in crafting the scripture, which embeds veiled references to the liturgy for ritual specialists while offering accessible guidance to lay audiences. This dual function exemplifies how religious rhetoric can bridge specialized ritual knowledge and broader community engagement. In a related vein, Robert Ford Campany’s recent study of Shangqing Daoist scriptures in medieval period, also from Maoshan, explores how they function as “performative texts”, enabling practitioners to adopt alternative identities as rejuvenated cosmic beings in the here-and-now (Campany 2023). Campany’s analysis emphasizes how ritual texts can serve as active blueprints for religious role-playing rather than mere repositories of doctrine, broadening our understanding of “text acts” across historical periods.

By emphasizing the persuasive and performative dimensions of Maoshan texts in Republican China, including mountain gazetteers, liturgical manuals, and precious scrolls as a coherent whole, this approach reveals how rhetorical strategies were employed not only to preserve religious knowledge but also to innovate devotional practices and sustain religious communities amidst the socio-political transformations of the Republican era. This analysis integrates these materials with various contemporary newspaper and magazine articles, seeking to move beyond surface narratives to reveal the deeper logic and motivations driving pilgrimage practices. As a result, this study has identified six rhetorical strategies presented through the acronym IMPACT: Incorporation, Memory, Performance, Abridgment, Canonization, and Translation. These strategies offer a structured framework for analyzing how textual transformations at Maoshan contributed to its religious and social vitality. By understanding these strategies, we can better situate the Maoshan pilgrimage within the broader historical and cultural shifts of its time, beginning with the late Qing prohibition on pilgrimage practices and culminating in their resurgence during the Republican period.

2. Historical Context: Ban on Pilgrimage to Maoshan in Late Imperial China

To understand the resurgence of the Maoshan pilgrimage from around 1920 to 1937, it is crucial to first examine the severe suppression it faced in the late nineteenth century. The ban on pilgrimage, particularly under the governance of Tan Junpei 譚均培 (1828–1894), not only reflects the sociopolitical climate of the time but also sets the stage for understanding the subsequent revival. The harsh restrictions and negative perceptions surrounding the pilgrimage form a necessary backdrop to appreciate how Maoshan Daoists later innovated their textual practices to attract and retain pilgrims.

Beyond the devastation caused by the Taiping Rebellion, the pilgrimage faced continuous suppression. The Yiwen Lu 益聞錄, a Catholic newspaper published by Shanghai Xujiahui Catholic Church (Shanghai Xujiahui tianzhutang 上海徐家匯天主堂) since 1879, frequently criticized the cult of the Three Mao Lords and its associated pilgrimages (Yiwenlu, 1880; 1883; 1896). Notably, during the tenure of Tan Junpei as Inspector-Official (xunfu 巡撫) of Jiangsu province in 1879, the pilgrimage was heavily suppressed (J. Wang 2012). Tan, influenced by the anti-clerical views of Han Yu 韓愈 (768–824),2 issued an order in 1880 prohibiting pilgrimages to Maoshan (Shenbao, 1880b),3 citing issues such as promiscuity, theft, rebellion, and tax evasion. Additional objections included the presence of spirit-mediums and the disorder caused by the influx of pilgrims.

The Qing government, particularly sensitive to the formation of groups and alliances after the Taiping Rebellion, supported Tan’s actions. Even after stepping down as acting governor in 1882, Tan’s influence persisted, with the popular Shanghai press Shenbao 申報 reporting that his orders were still being followed, leading to continued hesitancy among pilgrims (Shenbao, 1881). Reports indicate that local officials sealed off Maoshan’s mountain gate (shanmen 山門), warning that any defiance by the Daoists would result in the destruction of their temples as “illicit shrines” (yinsi 淫祠) (Shenbao, 1880a). This ban was enforced multiple times, citing the disruption caused by pilgrimage boats blocking passages under the bridge in Jintan 金壇, at the foot of Maoshan (Yiwenlu, 1880).

For over two decades, mentions of the Maoshan pilgrimage in the press were scarce, except for negative reports about Daoists soliciting or even coercing donations. The term “Maoshan Daoists” (Maoshan daoshi 茅山道士) often carried negative connotations, associating them with black magic and spirit-mediums. The newspaper tends to report incidents where people donning a Daoist robe and claiming to be a “Maoshan Daoist” asking for donations (Shenbao, 1893a), or worse, “forcing donations”(qiangmu 強募) (Shenbao, 1893b; 1898). Despite these challenges, Maoshan Daoists were occasionally called upon for their rituals, especially during epidemics (Shenbao, 1902) or to conduct rain prayers during periods of severe drought (Shenbao, 1904). Local branches of the cult of Three Mao Lords in Shanghai likely provided crucial income for the Maoshan Daoists. One report described a ritual called guoguan mingmu 過關名目 in Shanghai, intended to raise funds. This included contributions from the Maoshan shrine (Maoshan dian 茅山殿) in Gaochang temple (Gaochang miao 高昌廟), known for continuously disregarding the official prohibition (Shenbao, 1905).

Ultimately, regulating the pilgrimage over long term proved difficult. By 1908, articles confirmed that villagers from Changzhou 常州 continued their annual pilgrimage to Maoshan (Shenbao, 1908). Innovative methods to attract pilgrims emerged, such as distributing seals in incense bags designating pilgrims as “laureates among the pilgrims” (xiang zhuangyuan 香狀元), which usually led to local celebrations (Shenbao, 1908). The social atmosphere relaxed in the following decades, as evidenced by reports of a Sanmaohui 三茅会 procession during a sports competition in Nanjing in 1921 (She, 1921; Dagongbao, 1921), followed by the Dutianhui 都天会 honoring the ”Marshal [Who Patrols] All of Heaven” (Dutian yuanshuai 都天元帥, i.e. the local god Zhang Xun 張巡) (Katz and Goossaert 2021, p. 43), a large citywide festival previously prohibited but revived in Yangzhou and other Jiangnan urban centers during this period.4

To sum up, the persistence of the Maoshan pilgrimage under suppression highlights the resilience of popular religious practices during this period. The subsequent analysis of textual innovations will demonstrate how Daoist texts functioned strategically in the 1920s, not merely as religious documents but as instruments to revive and sustain the pilgrimage tradition, ensuring the survival and growth of Maoshan Daoism in a period of significant transformation.

3. Daoist Textual Innovations

The acronym IMPACT (Incorporation, Memory, Performance, Abridgment, Canonization, and Translation) introduces the six rhetorical strategies, whereas the main body of this article presents the primary sources in chronological order. This approach allows us to contextualize each rhetorical strategy within the unfolding social, political, and religious developments from late imperial periods to the early twentieth century. The chronological organization better demonstrates how these strategies emerged, evolved, and overlapped over time. Throughout the discussion, the key themes remain interconnected, which highlight how Maoshan Daoists alternated or combined these textual strategies to adapt to new circumstances, thereby leading to the revival of Maoshan pilgrimage.

3.1. Memory: Textual Retention and Reconstruction in Gazetteers and Liturgies

As a first step, textual innovation depends on textual retention. Without the preservation of earlier texts, textual innovation cannot take place. Jacopo Scarin conceptualizes the history of a sacred site as composed of multiple “strata of meaning”, which are layers of religious significance formed by stories, historical events, and religious knowledge associated with the site. These layers evolve as people transmit, reinterpret, and prioritize them over time, revealing a dynamic exchange between the past and present (Scarin 2023, p. 10). That being said, historically, events like fire and war have posed the greatest threats to textual retention and innovation. This is evidently manifested in the paratexts of various editions of the Maoshan gazetteer, which serve as repositories of ancient texts about Maoshan. These texts preserved valuable historical and religious content and provided the foundation upon which later textual innovations were built, ensuring the continuity of Maoshan’s textual heritage.

The history of various editions of Maoshan gazetteer has been thoroughly examined by Chen Guofu 陳國符 (Chen [1949] 2014, pp. 197–200) and Richard G. Wang (G. Wang 2014, Wang et al. 2016). The earliest known references date back to the Tang and Song dynasties, with works such as Maoshan ji 茅山記 and Maoshan xin xiaoji 茅山新小記, though these are now lost. The Northern Song saw the revision of Juqu shan zongji 句曲山總記 by Chen Qian 陳倩 (d.u.), and the Southern Song era saw a four-volume revision of Maoshan ji 茅山記 by Zeng Xun 曾恂 (d.u.) and Fu Xiao 傅霄 (?–1159), which also no longer survive.

The first important surviving edition is the Yuan dynasty’s Maoshan gazetteer (Maoshan zhi 茅山志), which dates back to 1330 and was compiled by Liu Dabin 劉大彬 (fl. 1317–1328) and Zhang Yu 張雨 (1277–1348). The original edition consisted of 15 fascicles, though only portions are currently extant. The Ming dynasty produced four notable editions: the 1423 Yongle 永樂 edition, the 1445 Zhengtong Daozang 正統道藏 edition with 33 fascicles (MSZ, 1445), the 1470 Chenghua 成化 edition, and the 1551 Yuchen Temple 玉晨觀 edition (Wang et al. 2016). These were followed by a Qing dynasty edition, the Complete Gazetteer of Maoshan (Maoshan quanzhi 茅山全志, preface 1669), compiled by Da Changuang 笪蟾光(1623–1692). In contemporary periods, the twenty-first century has seen the continued emergence of various recensions of Maoshan gazetteers, reflecting ongoing scholarly interest and the enduring significance of these texts (Li 2005; Yang and Pan 2007; Pan 2013; Z. Yuan 2021).

By studying the paratexts of these editions (Wang et al. 2016), we learned about the precarious conditions in which the woodblocks are preserved and, thus, the importance of regularly reproducing these woodblocks and texts. This forms a positive cycle to ensure textual retention and the role played by some individuals outside of the Daoist institution who, nevertheless, asserted an influential impact in this process.

For example, in the 1423 preface written by Hu Yan 胡儼 (1361–1443), he states:

“Yao Guangxiao,5 the Grand Preceptor for the prince, Duke of Rongguo 榮國公, with posthumous name Gongjing 恭靖, once serving at the Historiography Office, commissioned me to write a preface for the reprinting of the Maoshan gazetteer. […] According to records, there were earlier accounts of Maoshan, but the gazetteer was first compiled by the successor patriarch of the order, Liu Dabin during the Yuan dynasty. The woodblocks were destroyed amidst warfare at the end of the Yuan. The original engraving, inscribed by the recluse historian Zhang Boyu, was exceptionally refined and elegant. In the guimao year of the Yongle reign of our current dynasty [1403], Lord Yao obtained a surviving good edition of the old engraving from Chen Dexun, the Numinous Officer of this mountain [Maoshan]. Deeply moved by the thought that the literary records of this mountain had ample evidence, he gathered like-minded individuals to contribute funds and commissioned craftsmen to re-engrave the woodblocks for dissemination. This was indeed a most earnest endeavor”.

“太子少師,榮國恭靖姚公廣孝嘗在史館,以重刻《茅山志》,屬儼為序。[…] 按茅山舊有記,而志則始於嗣宗師劉大彬,故元時所編集也。元末板燬于兵。其故刻則外史張伯雨所書,極精潔。至天朝永樂癸末[1403],姚公得遺刻善本於本山靈官陳得旬,慨然念茲山之文獻有足徵者,乃合同志之士出貲,命工重鋟梓以傳,甚盛心也。”6

In the preface of 1470, written by Chen Jian 陳鑒 (1415-?, jinshi 1418), Chen states:

“In the guimao years of Yongle reign in our dynasty [1403], Master Yao the Junior Preceptor, renewed the work. In the year bingxu of Chenghua reign [1466], the woodblocks were destroyed once again. The Daoist Master Ding Yuming, who held the titles of Right Profound Justice of the Daoist Register and abbot of Chaotian Palace, had previously studied in these mountains. Deeply concerned that this book, was becoming increasingly scarce among people and might soon vanish entirely without any transmission, he feared that the flourishing legacy of this mountain would come to an abrupt end. The sacred traces and miraculous sites, divine ruins and blessed realms, imperial decrees, essays of great literary brilliance, the mystical patriarchs and Daoist lineages, celestial immortals assigned to heavenly offices, dedicated scholars and esteemed individuals, magnificent terraces and outstanding temples, cinnabar-inscribed stone steles, golden scripts on jade slips, as well as divine flowers and spiritual plants—how would these be documented? Would this not nearly result in the great loss of our heritage? Would this not a matter of profound concern for us? Thus, he sought out old woodblocks and good editions, collected the rewards from the court and the donations from benefactors, and commisionned skilled craftsmen to re-engrave the texts onto woodblocks, creating an imperishable record. He then requested me to compose a preface for it”.

“我朝永樂癸末[1403],少師姚公亦既新之,成化丙戌[1466],板復燬。道錄右玄義兼朝天宮主持丁法師與明,嘗受業山中,深慮是書在人間者日少日無,遂至於湮泯無傳,則茲山之盛事中歇,而其靈蹤異跡,神墟福境,奎文帝命,瓊編瑞檢,玄宗道派,仙屬天曹,志士高人,穹臺傑觀,丹書石刻,金薤瑤章,與夫神葩靈植,將何所稽,不幾乎大墜厥緒,豈非吾徒之憤事耶。乃求舊刻善本,裒朝廷之賞賚檀越之施予,命良于工者重鍥諸木,以為不朽之圖,問蘄予為之序。”7

Again, in the 1550 preface for the re-carving of the woodblocks for the Maoshan gazetteer, written by Xu Jiusi 徐九思 (1495–1580):

“At that time, the mountain gazetteer was again destroyed. Daoist Zhang Quan’en of Yuchen Temple raised funds and re-engraved it, and the work was completed. Since the mountain belongs to Jurong county, and I have held office here for nine years, he requested me to write the preface. Thus, someone informed me and presented it to me. The detailed records of the journeys of the Mao Lords, the majestic scenery of this mountain, and the traces of past visitors are all thoroughly documented in this gazetteer. What more is there to say! I have been ordered to transfer to another internal position, and as I pack my belongings to head north, I have no time to say more”.

“時山志復燬,玉晨觀道人張全恩募工重刻既成,以山屬句容,余令茲九載,謁余為序。遂以告或人者授之。茅君履歷之詳,茲山景物之勝,昔人寓玩之蹟,志盡之矣。復何言哉!余方奉命內遷,束裝北上,亦不暇他言云。”8

In the 1551 preface for the re-compilation of the gazetteer, written by Jiang Yongnian 江永年 (fl. 1506–1531):

“The previous gazetteer was compiled by the former Yuan Patriarch Liu Dabin, biography written by the Hanlin Scholar-in-Attendance Zhao Mengfu, praises written by Grand Academician Yu Ji, and with calligraphy by the Recluse Historian Zhang Boyu of Huayang—an accomplishment known as the ‘Four Wonders.’ At the end of the Yuan dynasty, the woodblocks were destroyed by war. In our dynasty, the woodblocks were re-engraved three times, only to be destroyed three times, leaving no records. Now, Daoist Zhang Quanen of the Transcendents’ Mansion and Yuchen Temple has obtained an old edition and raised funds to re-engrave it. The temple’s Numinous Officers Dai Shaozi, Ren Shaoji and Jin Xuanli, along with Chen Yingfu, promoter of the teachings from the Yuanfu Palace, requested me to arrange and compile the new edition. I also included at the beginning the esteemed imperial rituals of our imperial court, construction records, and at the end the poems written by various officials after their visits. I consider it essential to include these, so I compiled them into the opening chapter, simplified the charts and maps, and completed the gazetteer. Thus, I have no more to add. On the day of Duanyang in the Xinhai year of Jiajing [1551], recorded respectfully by Jiang Yongnian, Sacrificial Officer of Liuqian, a native of this county”.

“舊志編自前元宗師劉大彬,傳於翰林承旨趙孟頫,贊於大學士虞集,書於華華陽外史張伯雨,世稱四絕。元季板罹兵焚,我朝三刻三燬,漫無紀載,今真人府贊教玉晨張全恩得舊本,募工重刻,本山靈官戴紹資任紹績金玄禮,贊教元符宮陳應符請餘詮次,並書國朝懿典於前,修建諸文,及羣公登覽詩作於後,計不可無述,偕著其葉於首,簡門圖改證以成全志,茲弗贅雲。嘉靖辛亥[1551]端陽日,柳汧祭史,邑人江永年謹識。”(MSQZ, [1669] 1898, 10a–11a)

As demonstrated by the above-mentioned paratexts of various Maoshan gazetteers, historical events such as accidental fire or wars posed significant threats to these texts, prompting efforts to re-engrave and reprint them. The prefaces of the 1423, 1470, 1550, and 1551 editions of the Maoshan gazetteer illustrate how figures like Yao Guangxiao and Zhang Quanen mobilized resources and rallied support to restore these texts after their destruction. Every step of the production and circulation of these gazetteers is the result of concerted efforts by skilled religious specialists, dedicated locals, and various “intermediaries of religious culture”,9 who often transcend local, cultural, or confessional confines and play a crucial role in these preservation efforts. Beginning in the late imperial period, when these gazetteers were produced in large numbers, the production of gazetteers increasingly attracted broader patronage and readership beyond their immediate locality, with consequential outcomes. The construction of local historiography is thus often of a trans-local nature, contributing to an expanded network of branch sites and pilgrimage associations from afar, thus creating a shared regional religious culture. Thus, the dedication of these “intermediaries of religious culture” to preserve Maoshan’s textual heritage emphasizes the multi-directional nature of textual retention and innovation. Without the foundational preservation of these ancient texts, the later innovations that made Maoshan’s teachings more accessible to broader audiences in the 1920s would not have been possible.

Additionally, lists of signatories, often as funders and contributors to collaborative projects, highlight the communal efforts behind the publication. These contributors, often simultaneously also distributors and promoters, play an important part in the circulation of such texts. They thus serve as proselytizers and promoters of moral discourse, religious practices, or sacred sites, depending on the nature of the texts. On the other hand, we should highlight that the authors of prefaces of religious texts play crucial roles in framing and contextualizing these texts. Not only do their prefaces give authority and prestige to the texts, but they also provide readers with the necessary background to engage with them.10 Therefore, the prefaces can significantly influence the reception and understanding of religious texts, facilitate the transmission of religious knowledge, and provide social contexts for these publications.

Textual innovation also relies on the reconstruction of fragmented or lost texts and their republication, particularly when those texts face threats of complete textual loss or destruction due to war or other calamities. The significance of these efforts becomes apparent when we examine cases where the entire corpus of texts was lost, necessitating their meticulous reconstruction from memory by dedicated Daoists. This practice ensured that even in the face of adversity, the religious and cultural heritage of Maoshan could be preserved and perpetuated. For instance, Zhang Hefeng 張鶴峰 (fl. 1860–1864), a Daoist at Yuanfu Temple 元符宮 on Great Mao Peak 大茅山 during the Tongzhi 同治 era (1862–1874), recounted in the postface how he painstakingly reconstructed the Precious Litany of the Three Mao Lords after it had been lost during the Taiping Rebellion:

“The Precious Litany of the Three Mao Lords is the source from which the Transcendent Lords attained the Dao, and it is the foremost fundamental teaching in Daoism. It must be recited with devotion, day and night. I have memorized this diligently and have not forgotten the text. During the many years I spent on the mountain, there was not a day when I did not cleanse my hands, burn incense, and quietly recite it. […] In the tenth year of the Gengshen cycle [1860], during the intercalary third month, the rebel bandits ascended the mountain and set fire to the Daoist temple and the courtyard. Not a single tile remained intact. At that time, I paid no attention to any of my worldly possessions, but only took care to bury the scripture and litany of the Transcendent Lords in a secluded place, hoping to protect them from destruction. By the sixth month of the third year of Tongzhi [1864], by the grace of the mighty armies of the government, the entire region of Jiangnan was reclaimed. The Daoists gradually returned to the mountain. I then went back to the original place to search for the scriptures, but they were lost. Although prosperity and decline are determined by fate, no calamity was as severe as the devastation of war. Reflecting on the fact that it is just like with houses burned, there would be no place to rest one’s feet temporarily. The lost scriptures meant the loss of the foundation of self-cultivation. Fortunately, I had studied them thoroughly from a young age, and I transcribed several volumes as a temporary measure to continue the chanting and recitations. However, I fear that over time they might deteriorate, which would not only betray the teachings of my master but also make it difficult to face others”.

“三茅寶懺乃應化真君得道之源,道教中第一要宗也。須朝夕虔誦。余謹記不忘。在山十數年,無日不沐手焚香。息心寧卷。[…]迨庚申十年[1860]。閏三月。逆匪上山放火。殿宇道院。片瓦無存。時余身外之物。概不顧問。獨將真君經懺。埋藏偏僻。希冀免劫保全。至同治三年[1864]六月。蒙各大憲軍威丕著。克復江南全省。道等漸次回山。余即往原處跟尋。迷失所在。然雖盛衰有數。而兵燹之災。莫此為甚。竊思房屋燒燬。暫無拖足之區。經懺遺忘。遂失修心之本。余幸從幼熟讀。抄寫數卷。權應宣誦。但恐將來日久殘缺。不特有負師訓亦且難對。”(SMBC, 1924, 34a–36a)

Indeed, the successful reconstruction of the Maoshan scripture and litany in 1924 ensures they were recited by younger Daoists in the decades to come. For example, a travelogue from Li Tongxian recounted his visit after the peak of the pilgrimage season in May 1935 (Li, 1935), when he found that only a few novice Daoists 道童were reading a certain Scripture of Three Mao Lords 三茅經 in Maoshan.11 This leads us to explore the broader implications of such efforts, particularly how they align with the strategies of textual innovation and the dissemination of Maoshan lore.

3.2. Abridgment: The Essentials of the Maoshan Gazetteer, Maoshanzhi Jiyao 茅山志輯要

The 1920 edition of the Essentials of the Maoshan Gazetteer (Maoshanzhi jiyao 茅山志輯要) (MSZJY, 1920), compiled by Jiang Daomin 江導岷 (1867–1939)12 and Teng Ruizhi 滕瑞芝 (fl. 1920–1947), printed by the Shanghai Hongda Shanshu Ju 上海宏大善書局,13 represents a significant textual innovation aimed at making Maoshan’s rich religious and cultural heritage more accessible. This abridged gazetteer was intentionally reduced to 65 folio (double) pages, in contrast to the much lengthier earlier versions, greatly improved accessibility to a broader audience and a wider dissemination of Maoshan’s rich textual heritage.

Why was an abridged gazetteer valuable in 1920? Traditionally, like local gazetteers (difangzhi 地方誌), mountain gazetteers served as guidebooks for visitors to mountains in late imperial China, offering essential information about the history, geography, and cultural significance of numerous mountains in China. As early as 1503, Du Mu 都穆 (1458–1525, jinshi 1499) of Suzhou consulted the Maoshan gazetteer to familiarize himself with Maoshan’s history and lore (Du, 1992). This function persisted into the Republican era, with the Maoshan gazetteer continuing to be a key text for pilgrims visiting Maoshan. However, in early twentieth-century China, there was a shift towards making religious texts more popular, mirroring broader social and literary trends that sought to democratize knowledge and religious practice through a more widely accessible format14 that uses a more understandable vernacular language. This movement aimed to bridge the gap between elite literary culture and popular religious devotion. Educated individuals like Long Zehou 龍澤厚 (1860–1945) also recognized that traditional texts, such as the Maoshan gazetteer, were overly literary and therefore inaccessible to the common folk. Despite the admiration for the aesthetic qualities of Maoshan zhi, its refined language limited its reach. One clear reflection of this sentiment can be found in Long Zehou’s 1924 preface to the Precious Scroll of the Three Mao Lords, where he lamented the limited audience of the ancient edition of the Maoshan gazetteer due to its overly sophisticated style. The preface indicates that Maoshan Daoist Teng Ruizhi played a crucial role in this process by publishing a superior lithographic edition of the precious scroll. The canonization of the Three Mao Lords through spirit-writing as “Imperial Lords” further reinforced the spiritual authority of Maoshan (will be discussed further in Section 3.3 and Section 3.4). This preface illustrates the shift towards textual abridgment and vernacularization, fueling hopes of Maoshan’s revival amidst the broader sociopolitical challenges the Maoshan Daoists faced. The preface reads:

“I have visited Maoshan several times. I read the Maoshan gazetteer and admired its inscriptions and poetry. I once harbored the intention of revising and republishing it, but lamented that its language is too refined and therefore not easily understood by the common folk. This so-called beauty is also its shortcoming, leaving some regret. In the third month of the Jiazi year (1924), I visited the mountain again and came across the Precious Scroll of the Three Mao Lords. Even women and children could understand them. Initially, I obtained a woodblock-printed copy, and later I acquired a lithographic edition from Shanghai, which was of superior quality compared to the woodblock edition. The lithographic edition included a map of the mountains. It was published and distributed by the Daoist Teng Ruizhi of Yiyun Courtyard. Its preface was written by Ge Peiwen, a recluse from Huayang, who mentioned that he and Teng had studied Daoist teachings together. Alas, the Daoist tradition has long been in decline, and yet, there is truly a person like Teng! How can I not feel fortunate for our Daoist tradition? The revival of Maoshan is only a matter of time! I leave a message for Teng: strive to deepen your Daoist practices. The affinity to achieve the path of immortals depends on you. A recently inscribed secret text with a divine edict was published, and I was gifted a copy. I came to know that the Three Mao Lords had been elevated to the title of “Imperial Lords”. Written in the spring of Jiazi year of the Republic of China [1924] by Long Zehou of Guilin”.

“予遊茅山數矣。讀茅山志愛其金石詩文。曾有重修之意。惜其文皆雅。故不能通俗。所謂美尤不足。有遺憾也。甲子三月如山。見有三茅寶卷。婦孺盡曉。初得木板一冊。又得上海石印一冊。較木板精良。前有山圖。則怡雲院道士滕瑞芝所刊送也。其序為華陽小隱葛佩文。謂與瑞芝相研道學。噫。道門衰落久矣。而竟有滕子其人耶。吾不能不為吾道幸矣。茅山復興有日矣。寄語滕子。勉加玄功。仙緣之有分。其在子矣。近刻秘笈誥命。贈以一本。俾知三茅君已晉帝君尋號云。民國十三年甲子春桂林龍澤厚贈言。”(SMBJ, 1924, 3a)

The Essentials includes illustrations and several prefaces taken from the 1669 Qing Gazetteer Maoshan quanzhi 茅山全志 compiled by Da Changuang, including those by Da Changuang and Xu Zishen 徐子慎 (preface 1824), along with iconography of the Three Mao Lords, topographical illustrations, divine genealogies, descriptions of temples, monasteries, springs, and caves, as well as a collection of poems and a postface by Jiang Daomin. It also contains a table of contents of the original gazetteer 原志總目. The postface to the Essentials, written by Jiang Daomin, reflects his motivation and process behind the compilation and abridgment of this important text. Jiang’s account details his experiences visiting Maoshan, his interactions with earlier editions of the gazetteer, and his goal of preserving its rich content while making it available to a broader audience.

“Postface. Mount Juqu [Maoshan] reflects the natural topography of mountains and rivers. Its name dates back to the Han dynasty, gaining greater renown during the Qi and Liang dynasties, when it became prominent among Daoist practitioners. It was acclaimed as the “Eighth Grotto-Heaven”, a term rooted in Daoist terminology. I, Daomin, have long admired it but never had the opportunity to visit. In the autumn of the gengshen year [1920], in the ninth month, I was ordered by Master Zhang Nantong [Zhang Qian 張謇 (1853–1926)] to handle some matters at the Golden Ox Cave of Maoshan. Tao Shouzhi of Jiangdu accepted the task and acted as my guide. We crossed the Yangtze River to Jingkou, then traveled overland to reach the Golden Ox Cave. From the southern ridge of the mountain, we ascended to Great Mao Peak, reaching an elevation of almost a thousand ren. From its heights, one overlooks the surrounding mountains, which coil like crouching dragons below. Looking back at the Three Mao Peaks, they rise and fall in winding patterns, connecting to Great Mao Peak in the shape of the character “已” (yi). It became clear to me that the name “Juqu” is indeed well deserved. As known to all, all famed mountains must have a gazetteer. Upon inquiring about the gazetteer of this mountain, I was informed by Pan Haoyuan, the abbot of Yiyun Temple, that only one old gazetteer from the early Qing period survives, awaiting republication. I borrowed this gazetteer and promised to print one hundred copies as a gesture of gratitude. While reading the gazetteer on my return journey, I came to understand the mountain’s history and renowned landmarks. However, as the original text was overly voluminous, I took the liberty of compiling an abridged version. The revised version includes the following sections: First, a map of the mountain, showing the grandeur of its three peaks; Second, the preface by Da Changuang, preserving the content of the original gazetteer; Third, a preface by Xu, which outlines theoretical discussions; Fourth, a genealogical record of the Three Mao Lords, tracing their divine origins; Fifth, descriptions of various springs and caves, providing historical anecdotes; Sixth, poems from famous figures since the Liang and Tang dynasties, exalting the cultural and aesthetic significance of the mountain, intended to inspire visitors. I retained only the essential headings, omitting other unnecessary details for the remaining contents. This work is titled the Essentials of the Maoshan Gazetteer (Maoshan zhi jiyao 茅山志輯要). For those who seek truth and beauty, or wish to explore Juqu mountain, it will suffice to have this volume as a guide. Written on the sixteenth day of the twelfth lunar month, gengshen year [1920], by Jiang Daomin of Wuyuan”.

“跋。句曲狀山川之形勢也。其得名始漢,至齊梁而名益,著顯道家者流,名山為第八洞天。洞天云者,亦道家語。導岷心夙慕之,而無緣一陟其地。庚申[1920]秋九月奉張南通師命,有事于茅山之金牛洞。江都陶君受之爲之導,渡江至京口陸行,抵金牛洞。由山南小嶺攀登大茅峯。高殆千仞,俯覽眾山,如伏龍盤旋于其下。回顧三茅,三茅峯起伏曲折,連貫大峰成已字形。恍然于句曲之爲名,不誣夫。世所稱名山必有志。詢茲山之志,怡雲院住持潘浩元云:清初舊志僅存一部,方待重刊。余乃借之,許印百部為報。歸途讀志,知山之歷史名勝矣。顧篇什夥繁,因重為訂輯。首山圖,具三峯之形勝也。先笪序,重原書也;次徐序,著理論也;次三茅眞君紀系,知靈蹟所自也;次各泉洞記,取備掌故也;次梁唐以來名人詩,擷揚風雅以助遊與也。餘存其目,而文不備錄。名之為《茅山志輯要》,云爾。世有求眞攬勝,為句曲之遊者乎,手此編亦足為導矣。庚申臘月既望婺源江導岷跋。”(MSZJY, 1920, 65a)

Press articles from the 1930s confirm that the gazetteers continued to be preserved at Maoshan and in private collections. For instance, Yi Junzuo 易君左 (1899–1972), author of Idle Talk on Yangzhou 閒話揚州 (1934) and serving as an official at the Ministry of Education, recorded in 1934 that he was led by Abbot Teng Ruizhi to read the gazetteers at Yiyun daoyuan (Yi, 1934). Another testimony comes from Sheng Cheng 盛成 (1899–1996), an activist, intellectual and author,15 who published a series of ten articles about the Maoshan pilgrimage in Dagongbao 大公報 between 5 April and 20 April 1936 (Sheng, 1936a). Sheng stayed in the sixth lodging六房, which is called Yiyun Daoist Courtyard (Yiyun daoyuan 怡雲道院) during his visit in 1936, where Teng Ruizhi was the abbot of the temple on Maoshan. On his visit, he was welcomed by a young deputy abbot named Xu Jinbo 徐晉伯, aged under 30 years old. Sheng Cheng particularly remarked on his hospitality and socializing skills (shan tantu 善談吐), from whom he learned many more details about the pilgrimages to Maoshan, which is central to our study. In particular, he mentioned that Wang Yiting 王一亭 (1867–1938) (Katz and Goossaert 2021, Chapter 6) has agreed to print the gazetteers for them:

“There are two types of pilgrims: those who burn incense and those who perform jiao offerings. The largest number of pilgrims come to burn incense, two-tenths of them come to perform jiao. After the opening of the mountain gate in the first month, pilgrims from the north of the Yangtze River come to burn incense, they don’t linger on the mountain [for too long] and descend after spending one night on the mountain only. This year, the incense burning in the first month was not as popular as the last year, because last year was a drought year. In Jiangnan, there are people who burn incense and perform jiao offerings. The majority of pilgrims who asked for the jiao offerings are mostly from the four provinces: Suzhou, Songjiang, Changzhou, and Zhenjiang, with the most of them from Danyang and Wujin. Among those pilgrims to Maoshan, they have one leader (xiangtou 香頭) for every hundred pilgrims and one deputy leader (xiao xiangtou 小香頭) for every ten people. Every autumn, the Daoist priests go down from the mountain to deliver the talisman to the pilgrims, and at the same time, they negotiate with the leaders of pilgrims’ associations for the rituals to be performed next year. Before each pilgrim goes to the mountain to participate the jiao offerings, they make a lot of efforts at home, and their family gives them one more bucket of rice and one more bucket of wheat each year to reward them for their efforts, and they hand over the reward to the leaders for profit. In this way, for three years, there are six harvests, there are three buckets of rice and three buckets of wheat as the principal and profits, and the leaders organize the pilgrims to come to Maoshan. The boat fare, food, candles, and fees for the jiao are all included, so for each ritual, the mountain only gets two or three yuan.16 If the pilgrims for the jiao offerings are from Shanghai, it was much better, and each ritual could net twenty to thirty yuan. Mr. Wang Yiting and Mr. Du Yuesheng often come to Maoshan for the jiao offering! Mr. Wang also promised to print the gazetteers [Maoshan zhi] for Maoshan”.

“香客分燒清香和打醮的兩種。燒清香的最多,打醮的占十分之二。正月開山門以後,江北的香客就來燒清香了,他們不駐腳的,在山上過了一夜就下去了。今年正月香火,不如晚年,這是因為去年是荒年。江南的人,燒清香的打醮的都有。上山打醮的香客,以蘇松常鎮四府屬的人居多,尤以武進丹陽為最多。他們上山的香客,一百個人有一個香頭,十個人有一個小香頭,每年秋季,道士下山與香客送符,同時和香頭接洽來年道場。每個香客要上山打醮之前,自己在家中,多多出力,家裏人酬勞他的出力每年多給他一斗稻一斗麥,他將報酬交把香頭生利,如此三年六熟,共有三斗稻三斗麥的本利,由香頭組織香會到茅山來。船費吃用香燭醮費,一切在內,所以每場法事,山上只落得二三元。上海來的打醮香客,那就好了,每場可淨得三二十元。王一亭杜月笙諸先生常上山來打醮呢!王先生還答應代本山印志書呢。”(Sheng, 1936c)

This 1920 abridged edition of the Maoshan Gazetteer and the attempts of Maoshan Daoists to continue reprinting it exemplify the strategy of textual innovation through simplification and dissemination. This ensures that Maoshan’s rich traditions can reach a wider audience while maintaining the integrity and continuity of its textual heritage. The strategic abridgment of the Maoshan Gazetteer serves as a precursor to further textual innovations that sought to adapt Maoshan’s religious texts to the changing socio-political landscape of the early twentieth century.

Moving on to the next section, we will look at the role precious scrolls played in promoting the Maoshan cult in Republican China. The vernacularization of sacred texts through performances of precious scrolls by mediums and storytellers served as a vital channel for propagating the cult of the Three Mao Lords, further reinforcing their newly canonized status among broader audiences.

3.3. Translation and Performance: Religious Literature of Precious Scrolls (Baojuan 寶卷)

Maoshan Daoists strategically employed vernacularization in adapting precious scroll literature to expand their religious influence and attract larger number of pilgrims. Precious scrolls (baojuan 寶卷) are vernacular religious texts that recount the hagiographies of deities, often performed orally by storytellers to communicate religious narratives to a broad audience (Overmyer 1999; Che 2009). By simplifying complex doctrinal ideas and presenting them in accessible language in local dialects, these texts allowed the teachings and miracles associated with Maoshan gods to reach, and resonate beyond the temple halls and literate elites. The performances of precious scrolls, which were both educational and devotional, conveyed the stories and miracles of the Three Mao Lords, making them relatable to laypeople. This strategy reflects a conscious decision to shift the communicative register from a highly formalized “code” to a more fluid and inclusive mode of expression.

When we compare the language, contents, and performances of the three types of ritual texts related to the Maoshan: scriptures (jing 經), litanies of repentance (chan 懺), and precious scrolls, these texts demonstrate two diverging textual approaches based on their targeted audiences and objectives. Scriptures and litanies of repentance are relatively shorter, tightly structured, and often formulated in a learned and sometimes esoteric language, requiring literal memorization by their literate audience, including religious specialists. These texts, usually written in classical Chinese, employ a ritual register with abundant archaic elements, making them opaque even to modern readers. These texts resemble the “formalized” modes of communication discussed by scholars of ritual language, such as Maurice Bloch (Bloch 1974). According to Bloch, such heightened formality can limit the potential for open-ended interpretation, directing attention away from propositional meaning and toward illocutionary force—reinforcing the authoritative, timeless quality of the sacred tradition. Like the phenomenon observed in intensely formalized political or religious oratory, the classical register used in scriptures and litanies curtails the spontaneity and adaptability of speech, engendering an aura of unchallengeable authority rather than inviting debate or logical contradiction. Comparing these liturgical texts with other genres, such as gazetteers discussed previously, can often reveal their textual genealogies and the deep temporal layering of their vocabularies, thereby situating their authority within a long-established lineage.

In contrast, precious scrolls, narrated in vernacular language and often performed orally, present a more flexible and less formalized medium. They are lengthier, more complex and dramatized, maximizing their appeal to audiences more receptive to oral performances. Precious scrolls are thus not merely “popular” versions of religious texts, rather, they represent a communicative strategy that does not rely on dense, archaic registers. As Bloch’s studies of ritual speech suggest, when the communicative mode becomes less rigid and more accessible, the emphasis shifts from strictly maintaining continuity and hierarchical authority to fostering engagement, relatability, and communal participation. While scriptures and litanies aim to promote self-cultivation for transcendence and salvation among the literate, the aim of precious scrolls is to proselytize by retelling gods’ stories to the local population in a public setting. This objective determines that these precious scrolls strategically incorporate local elements and entertaining narratives, expanding the boundaries of religious influence by appealing to a sense of shared religious culture rather than doctrinal authority. Whereas the archaic language of scriptures and litanies aligns with the immutability and hierarchical authority of tradition, precious scrolls open a space for communal involvement and adaptive interpretation. While scriptures and litanies adhere to a timeless, invariant “code” that accentuates their transcendent authority, the precious scrolls’ adaptability and performative dynamics highlight the relational and affective power of religious storytelling.

Such a method does not undermine the sacred character of Maoshan’s lore but rather situates it within the lived experiences and emotional frameworks of common devotees, thereby mobilizing a broader spectrum of religious participation. In doing so, precious scrolls exemplify how religious communication can function as “weak illocutionary acts”—not necessarily aimed at imposing doctrines, but rather at inspiring emotional resonance, strengthening social networks, and reinforcing communal devotion (Ahern 1979). Spirit-mediums, known as xiangtou 香頭 in emic terms, thus played a crucial role in disseminating religious narratives in precious scrolls and organizing and leading the Maoshan pilgrimages.

Maoshan Daoist Teng Ruizhi also actively promoted the precious scrolls as a means to spread Maoshan lore. By encouraging devotees to distribute multiple copies and recite them regularly, Teng sought to broaden the text’s reach and impact. His emphasis on the text’s protective and beneficial properties highlights its practical value, appealing to a wider audience and reinforcing Maoshan’s religious significance, as shown in the foreword for the precious scroll of Three Mao Lords:

“This precious scroll, with every word written with sincerity, painstakingly providing guidance and enlightenment, is a book that benefits the world. All incense-burning devotees should acquire multiple copies to distribute among their relatives and friends far and wide. Reciting it regularly will greatly multiply the merits of burning incense. Those who invite this precious scroll home must treat it with utmost respect, wrapping it in new cloth and offering it with fragrant incense. This can exorcise evil, protect the home, bring fortune, and ward off calamities. Reprinted in the winter month of the twelfth year of the Republic. Respectfully distributed by Daoist Teng Ruizhi of Yiyun Daoist Courtyard on the Great Mao Peak”.

“此卷字字樸實,苦心點化,乃有益世道之書。凡燒香信士務要多請幾本回去,傳送四方親友,時時宣誦,則燒香功德格外加倍矣。請此卷去者,必須十分敬重,將新布包好,清香供奉,可以驅邪鎮宅發福消災。民國十二年冬月重刊 大茅山頂山怡雲道院道末滕瑞芝謹送”(SMBJ, 1924, Foreword)

By encouraging devotees to distribute and frequently recite the precious scrolls, Teng extended the domain of religious authority of Maoshan into more intimate and dynamic social contexts. His emphasis on the practical, protective, and morally beneficial aspects of these texts resonates with the anthropological insight that, in religious contexts, formal constraints and performative freedoms interact to shape not just meaning but also communal bonds and religious efficacy. The circulation of these precious scrolls and the involvement of spirit-mediums in their oral transmission further underline the ongoing negotiation between formality and flexibility, tradition and adaptation, authority and accessibility. Taken together, these strategies reinforce Maoshan’s religious significance not solely by invoking ancient precedents but by reconfiguring the communicative landscape of ritual practice in ways that invite personal engagement, collective fervor, and the continual reshaping of cultural values.

Indeed, there are strong correlations between the places where various editions of precious scrolls were published and the regions from which pilgrims to Maoshan originated, as attested in newspaper articles. The most authoritative scholarly catalog of precious scrolls by Che Xilun records a total of 15 versions of precious scrolls on Three Mao Lords, published in Jingjiang (Jiangsu province) 江蘇靖江, Shanghai 上海, Suzhou 蘇州, Zhenjiang 鎮江, Nanjing 南京, and Changzhou 常州 (Che 2000, pp. 222–23). Based on Che’s work, Chen Peixuan 陳姵瑄 compiled a list of 13 extant precious scrolls about the Three Mao Lords (Chen 2021a). Through her analysis, these precious scrolls could be distinguished into two systems based on the name of the protagonists: the precious scrolls of the Mao family system 茅氏系統—which were published in Suzhou 蘇州, Huzhou 湖州 and Shanghai 上海—and those of the Jin family system 金氏系統—which were published in Nanjing 南京, Zhenjiang 镇江, and Jinjiang 靖江. Meanwhile, the origins of the pilgrims, as indicated by sources, especially the press articles, are mostly from around Nanjing and Shanghai and various towns in Jiangsu province, such as Wujin 武進, Wuxi 無錫, and Wuxian 吳縣 (current Suzhou) (Xi, 1920). Some are from Haimen 海門 and Jinsha 金沙 (current Nantong in Jiangsu province). If the pilgrims arrived by boat, they usually came from Suzhou 蘇州 and Wujiang 吳江. The geographic overlap between the publications’ locations and the pilgrims’ origins suggests that the distribution of precious scrolls effectively spread Maoshan lore, drawing pilgrims from these areas.

In the early twentieth century, most pilgrims to Maoshan were common folk from the local county, Dantu 丹徒, who were said to be predominantly engaged in farming and other labor work (Zhang, 1934). One of Sheng Cheng’s press articles pointed out the specialties of religious practices in Jiangnan at the time in comparison with traditions in the North (Sheng, 1936a). Several reports also indicate that the pilgrimage to Maoshan appealed to both genders and all ages. Pilgrims included men, women, elders, children, and they came in couples or old grandmas travelling with grandchildren. That being said, proportionally, several articles pointed out that there were more women than men. This observation is corroborated by reports with observations of pilgrims who traveled by boat, ascended Maoshan, and worshipped in the monasteries. The reason could be that the obligation of a continuous three-year mandate of conducting the Maoshan pilgrimage applies to women only. The author of a press article, Di Zhan, asserts that as long as the pilgrims could spare the costs, they will almost certainly go as an annual tradition (Di, 1934). As explained in Yü Chün-fang’s study, “It was desirable for a pilgrim to come to Hangchow for either three years or five years in a row—the first year for the benefit of her father, the second year for her mother, the third year for her husband, the fourth year for herself, and the fifth year for her children” (Yü 2001, p. 367). This explains the phenomenon that women seem to constitute a higher proportion of pilgrims across the available sources.

The temple fairs at Maoshan during the spring pilgrimage season were the most popular in the Jiangnan region. At the height of the pilgrimage season, tens of thousands of pilgrims could be coming to Maoshan daily. The pilgrimage to Maoshan is known for its “pilgrims [gathering] like clouds” (xiangke ru yun 香客如雲) (Li, 1935). During the apex of the pilgrimage season, many pilgrims walked shoulder-by-shoulder, such that the crowds blocked the path leading to the top of Maoshan. A popular saying illustrates this abundance of pilgrims on Maoshan as “tens of thousands ascending while tens of thousands descending” (shiwan chaoshagn shiwan xiangxia 十萬朝上十萬向下). Shen Jiezhou estimated that in 1935, approximately 300,000 to 400,000 pilgrims arrived at Maoshan during each pilgrimage season. The queue of pilgrim ferries extended across several li 里 (Di, 1934).

In the early twentieth century, the vernacularization through precious scrolls significantly promoted the Maoshan pilgrimage by making religious narratives accessible to a broader audience. For example, the prominence of women among pilgrims points to specific social practices and obligations associated with the Maoshan pilgrimage, as well as the possible appeals of precious scrolls to female devotees in particular. Moving forward, the analysis will focus on the canonization of deities through spirit-writing. This canonization process not only elevated the divine status of the Three Mao Lords but also played a pivotal role in revitalizing pilgrimage practices by enhancing the perceived authority and efficacy of these tutelary deities of Maoshan.

3.4. Canonization of Deities Through Spirit-Writing

Although there is not yet a dedicated study specifically analyzing the impact on pilgrimage following the canonization of tutelary gods at sacred sites through spirit-writing, recent burgeoning scholarship on the history of spirit-writing, in the Sinophone world (Goossaert 2022; Schumann and Valussi 2023) and its neighboring countries, such as Japan (Broy 2023), Korea (J. Kim 2020; Y. Kim 2024) and Vietnam (Hüwelmeier 2019), has opened avenues for examining this particular aspect. This growing body of research provides a foundation for understanding how such textual practices have shaped the religious landscape, influencing both the perception and practice of pilgrimage across different regions. For example, the study by Shiga Ichiko 志賀市子 on Song Dafeng 宋大峰, or Master Dafeng’s 大峰祖師 cult, explores how spirit-writing played a crucial role in transforming this local Chaozhou cult into a broader religious movement (Shiga 2022). Initially, Song Dafeng was a revered Chan Buddhist monk remembered for his contributions to the local community. However, only in the Qing period did he become deified as a god through spirit-writing, which allowed him to be invoked anywhere, not just at a specific sacred site. This practice expanded his cult beyond its territorial roots, contributing to its spread throughout Southeast Asia, particularly among Chaozhou migrants.

The case study of Song Dafeng’s cult illustrates how spirit-writing transformed local devotional practices and elevated the status of deities, a phenomenon similarly reflected in the case of the Precious Litany of the Three Mao Lords 三茅帝君寶懺. There are currently two known editions, one conserved in the Shanghai municipal library and the other at Maoshan (Goossaert and Berezkin 2012). The edition conserved in the Shanghai municipal library is dated 1924, the earliest known lithographic edition of the litany. It is published by Xie Wenyi 謝文益 on Wangping Street 望平街 in Shanghai and sponsored (kansong 刊送) by Wanshan Hongji She in Hangzhou 杭州萬善宏濟社 and Xuyuan Tan in Shanghai 上海恤緣壇. The words “Scripture and Litany of the Three Mao Lords” 三茅經懺 and “Lingshu mifu” 靈樞密府 are written in the center of the page 版心. As already pointed out in a study by Chen Peixuan (Chen 2021b), the entire volume is akin to a “collected edition” of the rituals of the Three Mao Lords, as in addition to the litany, the volume also includes the Litany Recitation Ritual of the Three Mao Lords 三茅真君經誦儀, the Nine Heavens Lingbao Golden Flower Scripture to Save Lives by the Mao Lord 九天靈寶金華沖慧度人保命茅君真經, the Precious Pronouncement of the Three Mao Lords 三茅真君寶誥, the Instructions from the Three Mao Lords 三茅真君垂訓文, and the Precious Litany of the Patriarch Mao Lord of the Nine Heavens to Eradicate Sins 祖師九天司命三茅真君滅罪寶懺, thereafter referred to as the Precious Litany of the Three Mao Lords. Chen has also noticed the fact of Three Mao Lords being granted Daoist titles through spirit-writing as indicated in this text,17 where the text writes:

“On the 14th day of the second month in the year of Jiazi during the Republic period [1912], Lingbao Tianzun decreed through spirit-writing at the Qingliang Wanshou Temple in Piling and pronounced [the title of] Three Mao Imperial Lords. There afterwards, all references to the Transcendent Lords should be read as the Three Mao Imperial Lords”.

“民國始甲子二月十四日奉(降鸞於毘陵清涼萬壽寺)靈寶天尊諭曰,三茅帝君。以下,凡見真君均應讀為三茅帝君。”

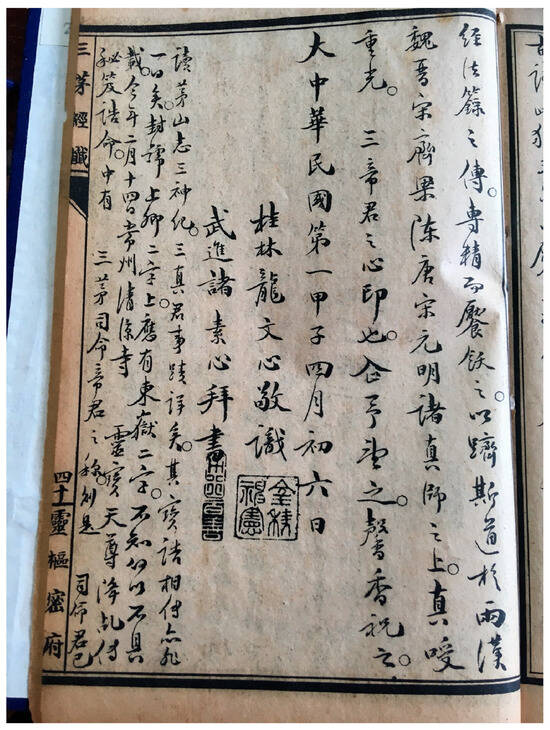

In the same year, Long Zehou wrote another postface, stating more explicitly, as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Canonization of Three Mao Lords through spirit-writing. Sanmao dijun baochan, 40a. Image reproduced by author in 2024, courtesy of Shanghai Municipal Library 上海圖書館.

“On the fourteenth day of the second month of this year [1924], at the Qingliang Temple in Changzhou, the Supreme Lord of Numinous Treasure descended and transmitted a secret edict through spirit-writing. It contained the title ‘Controllers of Fate, Imperial Lords of Three Mao,’ thus conferring upon him the title of ‘Imperial Lords.’ Readers should accordingly change the word ‘zhen’ to ‘di’ when reciting the titles in the proclaimation. I hereby make the announcement to you all of this”.

“今年[1924]二月十四日。常州清涼寺靈寶天尊降乩傳秘笈誥命。中有三茅司命帝君之稱。則是司命君已加封帝君矣。讀者自應於誦誥稱號之時。改誦真字為帝字。謹此奉告。”(SMBC, 1924, 40a-b)

The Qingliang Wanshou temple 清涼萬壽寺 in Changzhou is a branch monastery associated with the famed Buddhist mountain Wutai五台山. As pointed out in a study by Zhang Hua (Zhang 2016), during the first half of the twentieth century, Shanghai emerged as a dynamic hub for Buddhist activity despite lacking historical prominence in Chinese Buddhism. Changzhou’s Qingliang Temple, together with Tianning Temple 天寧寺, Hangzhou’s Haichao Temple 海潮寺, Ningbo’s Ayuwang Temple 阿育王寺, Fenghua’s Xuedou Temple 雪竇寺, and the Baoben Hall 報本堂 of Mount Putuo were branches temples established in Shanghai. These efforts aimed to attract pilgrims and raise funds, thereby strengthening connections between Shanghai and these prominent sites and increasing the number of temples in the city, significantly enriching its Buddhist landscape. This context also sheds light on the relative scarcity of studies on Buddhism and spirit-writing, a practice largely opposed by the Buddhist clergy yet widely embraced by lay Buddhist communities in Republican China (Zheng 2024). In fact, not only were the Three Mao Lords canonized through spirit-writing in a Buddhist monastery in Shanghai, but they were also granted additional divine titles within the daoyuan 道院, institutions closely associated with spirit-writing practices. This canonization went far beyond the traditional Three Mao Lords. In fact, each Mao family member received a specific title, further solidifying their divine status, as all daoyuans established altars to worship them:

“The Daoyuan of Shanghai, in reverence to the Supreme Patriarch of the Infinite, conferred titles upon Mao Meng, who was named ‘God of Primordial Creation and Transformation,’ Mao Yan was named ‘God of Original Transformation of the Manifestation of Mysterious,’ Mao Xi was named ‘God of Initial Transformation of the Mysterious Radiance,’ Mao Zuo was named ‘God of Efficacy and Mysterious on Conception and Transformation,’ Mao Ying was named ‘God of Supreme Transcendent of Management of Fates,’ Mao Gu was named ‘God of Upper Transcendent of Recording Fate,’ and Mao Zhong was named ‘God of Ultimate Protection of Life.’ All Daoyuans have established altars to worship them, thus they are also now proclaimed as Divine Lords”.

“上海道院奉無極老祖加封茅濛爲肇化通玄神。茅偃爲元化顯玄神。茅憙爲初化光玄神。茅祚爲孕化靈玄神。茅盈爲司命太真神。茅固爲定錄上真神。茅衷爲保命至真神。各道院均設位奉祀。是則又宜稱爲神君矣。”(SMBC, 1924, 40b)

Chen Peixuan’s study attributed this to the enthusiasm of the population to promote the cult of the Three Mao Lords (Chen 2021b). Chen sees this as a continuation of the tradition of receiving revelations in Maoshan, which has already produced the famous text Zhen’gao 真誥in the fifth century (Tao 499). However, Chen’s study has overlooked the abundant revelatory texts throughout late imperial China, with the background of spirit-written texts of Three Mao Lords more closely modeled on the canonization movements of Wenchang, Lüzu, and Guandi in the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries (Goossaert 2015), instead of the fifth-century Zhen’gao.

According to Vincent Goossaert, canonization “refers to processes of establishing sacred texts and divine personae as authoritative and conducive to salvation. […] The canonization process involves compiling textual canons for certain gods, but also granting authority to them by promoting them to higher status, both in the heavenly bureaucracy and in this-worldly pantheons. It is a multifaceted process that involves textual production and diffusion; doctrinal innovation; the building of social networks dedicated to these gods; and political legitimization” (Goossaert 2015). This theory of canonization offers a framework for understanding the canonization of the Three Mao Lords and its implications for pilgrimage practices. By elevating these deities within both the celestial bureaucracy and the divine pantheon, the process of canonization legitimizes their worship and integrates them into broader religious networks. The dissemination of these canonized titles and elevation of divine status through established networks in Shanghai would have bolstered the Three Mao Lords’ reputation of higher authority and efficacy, encouraging devotees to undertake pilgrimages to Maoshan to seek their blessings, thus leading to an upsurge in pilgrimage traffic.

Furthermore, the alignment of these canonized deities with the broader socio-religious landscape in Shanghai, an urban center with a growing religious and commercial infrastructure, would have facilitated a more widespread diffusion of their cult, likely among the lay Buddhists in Shanghai, such as Wang Yiting. This not only increased the number of pilgrims but also reinforced Maoshan’s status as a vital religious center, appealing to both Daoist and Buddhist communities. The canonization process thus played an important role in both the religious and practical dimensions of pilgrimage, ensuring the survival and expansion of the influence of the tutelary gods of Maoshan in the early twentieth century.

3.5. Incorporation: Miracle Tales and Divine Prescriptions

The textual strategies adopted by the Maoshan Daoists were not limited to shortening existing texts. They also included adding new content tailored to meet their readers’ evolving needs and tastes. which I refer to as “Incorporation”.18 This approach aimed to make the texts more engaging and suitable for practical usage in daily life, enhancing their appeal. For example, the inclusion of miracle tales and “divine prescriptions”19 attracted a broader audience by highlighting the religious efficacy and practical benefits of Maoshan’s religious practices.

In the lithographic edition of the Precious Scroll of Three Mao Lords (Sanmao dijun baojuan 三茅帝君寶卷), commissioned by Teng Ruizhi and published by Hongda shanshuju 宏大善書局 in 1925, there includes two sections of appendices: “Records of miraculous responses in Maoshan” 茅山靈驗記 with 16 miracle tales (SMBJ, 1924, 28b–33a), followed by 139 “Medicinal recipes of miraculous responses” 靈驗良方. In the introduction of the series of miracle tales, Ge Peiwen 葛佩文, with the style name “the Small Hermit of Huayang” (Huayang Xiaoyin 華陽小隱), attested to the efficacy of various sacred sites of Maoshan in healing and his purpose of compiling these miracle tales.

“Foreword to the ‘Records of Miraculous Responses at Maoshan’Maoshan is revered in Daoist texts as the Eighth Grotto-Heaven and the First Blessed Land, a sacred realm where the spiritual power is evident and beyond doubt. At Yuanfu Palace, the jade seal of nine immortals from the Han dynasty can ward off evil spirits, and the elixir well of Ge Hong from the Jin dynasty, when consumed, can cure chronic illnesses. The book of materia medica compiled by Tao Hongjing during the Liang dynasty mentions the Taiyi Yellow Essence, which can grant immortality when ingested. Beneath the Great Mao Peak, the spring from the purification pond can heal madness, leprosy, and wind sores, while the tea from the peak can improve eyesight and remove cataracts. Other miraculous substances, such as the divine mushrooms that prolong life and the green poria that cures hunger, are so extensively recorded in ancient texts that they cannot be exhaustively enumerated. I have spent the last three years in seclusion at Huayang, contemplating on these worldly events, which causing one only headaches and heartaches. In a time of great societal distress and moral decline, divine power stands out with overwhelming authority. What I have heard and witnessed confirms the extraordinary efficacy of these miracles. Thus, in my free time after practising inner alchemy, I have compiled several miracle tales into the ‘Records of Miraculous Responses at Maoshan’, organized in clear sections. This is offered to both those who have visited this sacred mountain and those who have not, so that they may solidify their faith more deeply. The records are respectfully compiled by Ge Peiwen”.

“茅山靈驗記敘言茅山道書稱為第八洞天第一福地,靈區聖域,徵信顯然。若元符宮漢代九老仙都玉印可驅邪伏魅,晉葛洪煉丹井之泉飲之可癒痼疾,梁陶弘景著本草有太乙黃精,服之可長生不老。大茅峯下,淨身塘之水,浴可癒瘋癩颷輪,峯茶可明目退翳,其餘神芝益壽,蒼朮療飢,種種靈驗,稽之古籍不堪枚舉。余小隱華陽於茲三載,靜觀時世,疾首痛心,人道非非,神權赫赫。耳聞目睹,靈驗非常,丹鉛餘晷,編輯茅山靈驗記數帙,分則眉列,餉諸來遊茲山與未遊者一目了然,以深信仰云。佩文諸誌。”(SMBJ, 1924, 28b)

A careful analysis of these 16 miracle tales uncovers valuable historical information on the pilgrimage practices of the time, with details that are not available in other sources. For example, one story suggests that pilgrimages to Maoshan in the 1920s were deeply connected to acts of devotion and seeking divine intervention during times of crisis. One story mentions “Offering incense by substitutes” (daixiang 代香), a practice in which those unable to travel entrust others to undertake the pilgrimage on their behalf. This practice ensured that individuals hindered by illness or conflict could still fulfill their vows through proxies. In this story, unable to visit personally due to a regional war in 1924, a man surnamed Liu from Shanghai entrusts another individual to offer incense on his behalf. When his son falls ill, Liu vows to make further offerings, after which his son recovers miraculously.20 In another story, strict dietary rules are highlighted; not only pilgrims but also local porters are expected to observe vegetarian diets before ascending Maoshan, reflecting broader ritual purity requirements.21 A porter eats eggs against vegetarian requirements and is punished by gods, leading to repentance and commitment to filial piety.22 The third story reveals the established contractual relationships between pilgrimage associations and local accommodations at Maoshan, with multi-year agreements ensuring annual lodging arrangements for pilgrims.23 In this story, a pilgrimage leader misappropriates funds from the pilgrimage association, prompting the gods to intervene by possessing a pilgrim from Jiangbei and exposing the wrongdoing. The leader eventually confesses and makes restitution with a significant donation to the temple, showing both the financial stakes involved and the perceived direct intervention of divine forces in ensuring divine justice and moral behaviors among pilgrims.24

A closer examination of these tales also reveals several recurring themes. First, on divine intervention, several stories emphasize the direct involvement of the Three Mao Lords in the reconstruction of temples and in the lives of their devotees, protecting them from harm and ensuring the success of their pilgrimage to Maoshan. Second, several narratives focus on miraculous healing, such as sacred springs and medicinal herbs available at Maoshan to pilgrims, often in response to sincere prayers or acts of generosity toward the Maoshan temples. One story involves Yao Jingzhi 姚靜之, a Daoist suffering from a severe illness who, after ineffective treatments, dreams of a deity instructing him to seek medicine at Maoshan. Upon his return and prayer, he finds a local spring’s water that miraculously heals him.25 The second story was provided by Ge Peiwen, compiler of the collection of 16 miracle tales as he signed off in the foreword, who prays for his ailing mother at Maoshan. He obtains a sacred talisman stamped by the legendary Maoshan jade seal of Lord of Nine Immortals 九老仙都君玉印 that, when placed on his mother’s head, promptly cures her of a debilitating illness.26 Third, Maoshan is portrayed as a sacred refuge, both from physical threats like war and from moral corruption. Fourth, the tales often include elements of divine justice, where unethical behavior is punished, and sincere devotion is rewarded. Fifth, Maoshan is depicted as a sacred space where strict dietary prohibitions are under constant surveillance and reinforced by dwelling gods. Sixth, several tales particularly mentioned the names of certain individuals who were devoted to the gods of Maoshan. It includes, in particular, a miracle tale-cum-biography of Long Zehou himself, which portrays Long as a highly dedicated devotee who abandoned his secular career to devote himself to spiritual pursuits at Maoshan:

“Long Zehou, a native of Guilin in Guangxi, was a distinguished disciple of Master Zhu Jiujiang along with his fellow student Kang Nanhai [Kang Youwei]. He abandoned his official position and retreat to the mountains, aspiring to transcend the mundane world. He held a deep admiration for Maoshan and had petitioned the authorities in Jurong county to protect its forests. At the Yuanfu Temple, he founded the “Society for the study of the numinous”. He conducted spirit-writing to spread teachings. He frequented the celestial realms of Huayang in search of the elixir of immortality. His primary goal was to revitalize the Daoist tradition. He wrote a postface for the ‘Scripture and Litany of Three Mao Lords’. His spiritual efforts and concrete deeds, earned him the recognition as a major contributor to the work of the Mao Lords. Without the miraculous efficacy, how could one touch and move the “living dragon” of Guilin?”

“龍澤厚廣西桂林人。同康南海為朱九江先生門下高足。棄官入山。有出世志。對於茅山頗為忻慕。曾請句容縣示。保護該山森林。在元符宮創設靈學會。開乩宣化。往來華陽仙境。欲求長生不死藥。振興道門為宗旨。作三茅君經懺跋。精神作用。事實昭彰。茅君之功臣也。不有靈驗。何其感動桂林之生龍。”27

The miracle tales of famous figures also include eminent names such as Kang Youwei and other social elites.28 In one story, a government official named Wang Jingchang 王景常, known for his skepticism of religious practices, was also portrayed as an eventual devotee after surviving a disastrous war.29 These miracle tales collectively reinforce the sanctity of Maoshan and the powerful, benevolent influence of the Three Mao Lords on those who honor and revere them.

To summarize, we can provide a typology of the 16 miracle tales into five categories, as shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

Typology of the 16 miracle tales in Sanmao dijun baojuan.

The typology of the 16 miracle tales in Sanmao dijun baojuan reveals the compiler’s intention to appeal to a broad audience by emphasizing various themes. A significant portion of the tales (9 out of 16) focus on divine intervention or healing, highlighting the efficacy of gods in Maoshan and attracting pilgrims seeking miracles or relief. Additionally, other themes, such as providing refuge, promoting dietary prohibitions, and the beef taboo (Goossaert 2005, 2025b), aim to reinforce morality, filial piety, and other virtues. Maoshan was also presented as a refuge from disasters, thereby reinforcing the sacredness of Maoshan and the authority of its tutelary gods. Moreover, the repeated mention of key figures such as Long Zehou and Kang Youwei in these tales suggests a significant role played by non-clerical social networks. This invites further exploration of how these individuals influenced Maoshan’s religious and textual developments.

4. Social Networks for the Publication, Circulation, and Promotion of Daoist Texts

As mentioned earlier, one of the most important patrons supporting the publication of texts at Maoshan was Long Zehou 龍澤厚 (1860–1945), courtesy name Jizhi 積之, a native of Guilin, Guangxi. As a fellow student of Kang Youwei 康有為 (1858–1927), Long had frequent opportunities to interact with the Daoists of Maoshan. Kang may first have visited Maoshan during his youth. After all his revolutionary activities failed, he returned to China after having revisited Maoshan with occasional prolonged retreats in Qianyuan guan 亁元觀. According to the Chronological Record of Kang Nanhai’s Self-Compiled Yearbook (Nanhai Kang Xiansheng Nianpu Xubian 南海康先生年譜續編), after experiencing setbacks in his reforms, Kang Youwei visited Maoshan in 1914 and 1916 (Kang, 1966, pp. 107–24). Kang’s visits were possibly on the invitation of a Daoist from Qianyuan guan named Yang Tongxiao 楊童孝 (d.u.). Kang eventually moved the remains of his mother and his younger brother to Qinglong Mountain beneath Jijing Peak 積金峰 of Maoshan for burial. Two extant stele inscriptions survive, one from 1917, which Kang composed for his mother’s tomb.30 In 1922, he also interred his wife at Maoshan.31 Kang’s capacity to establish and publicly commemorate family graves at Maoshan, an unusual privilege, appears less surprising when considered in light of his substantial patronage and contributions to Maoshan during his stays.32 Kang’s special affection for Maoshan subsequently influenced Long Zehou, who was closely associated with Kang’s political endeavors. Long Zehou played a crucial role in supporting the printing and dissemination of Daoist texts linked to Maoshan. His patronage facilitated the preservation and propagation of key scriptures, as demonstrated in his postfaces, which reveal both the historical and doctrinal significance of these texts, as well as the urgent need to secure them against loss (SMBC, 1924, 37a–40b).