Religiosity and University Students’ Attitudes About Vaccination Against COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. COVID-19 and Vaccination

1.2. COVID-19 and Religion

1.3. Religiosity and Conspiracy Theories

1.4. Vaccination, Religiosity and Conspiracy Theories

1.5. Religion in the Republic of Serbia

- (a)

- Whether textbooks are sufficiently adjusted in its content to be understood by students from lower grades;

- (b)

- Whether it is necessary to improve the curriculum (ZUOV 2013);

- (c)

- Whether Religious Education should be kept in the existing (confessional) form or adjust it in such a way as to be designed by the combined model6 (Šuvaković et al. 2023b);

- (d)

- Unresolved work status of Religious Education teachers (Bishop Irinej of Bačka 2023), as many as 2160, out of whom 1756 are in charge of children of Orthodox Christianity, 209—of Islam, 157—of Roman Catholic, and 38—of Protestant confession (Ministry of Education 2024).

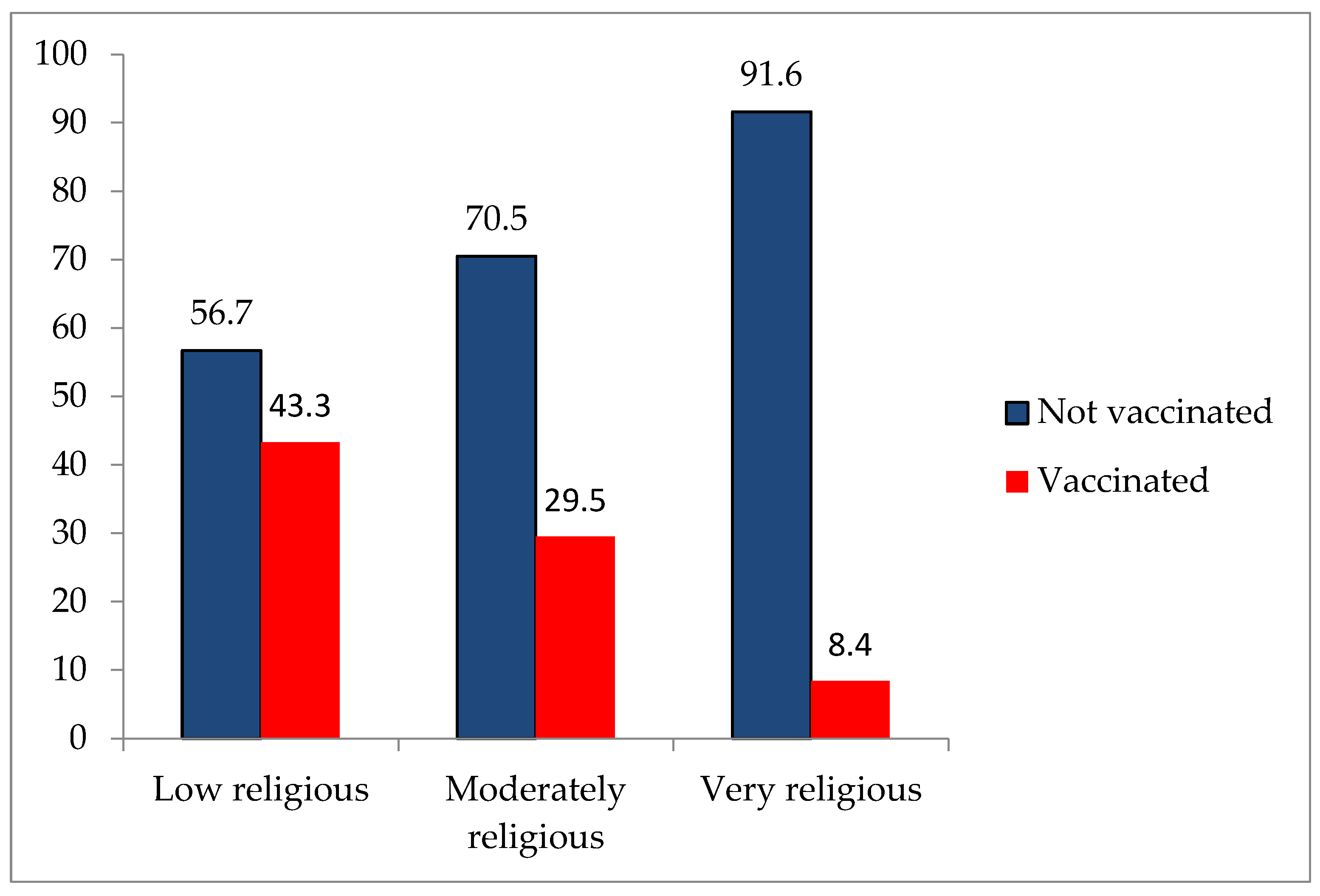

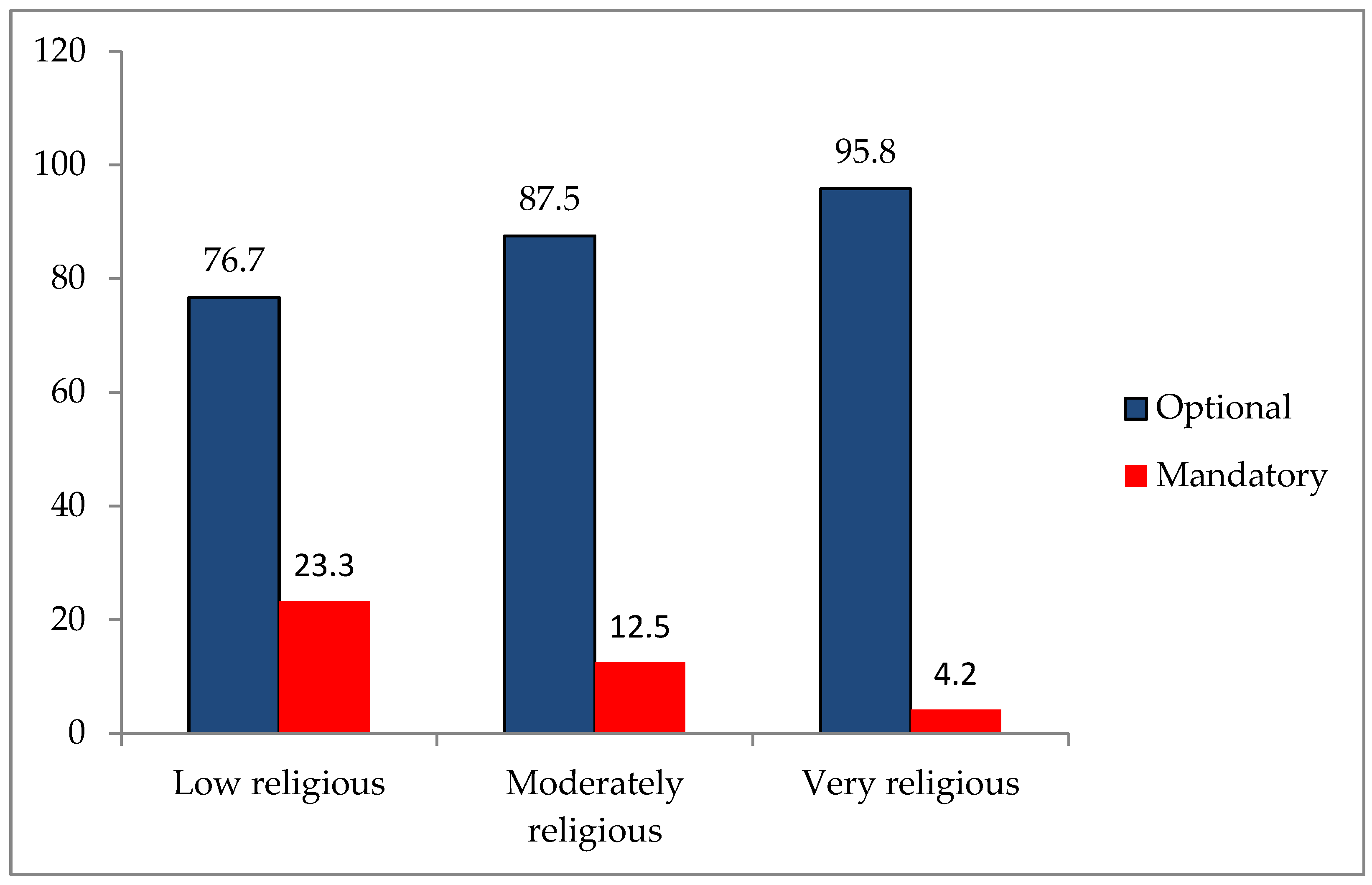

2. Results

3. Materials and Methods

- Socio-demographic features: gender, year of study, major subjects

- Religiosity scale (Ljubotina 2004—version of Stiplošek 2002). Here, it is important to note that there are different approaches in examining the concept of religiosity (Matejević and Stojanović 2020). The majority of sociological studies see religiosity as the individual’s self-assessment, meaning that, the attitude about religiosity is treated as a dichotomous variable (“Do you consider yourself a believer?”), the assessment on five-degree Likert scale (“How religious are you?” or “How often do you go to church?”) (Matejević and Stojanović 2020), with the answers ranging from “not at all” to “absolutely” or “quantified”) or it is treated as a confessional question, where the individual’s religiosity is practically made equal to religious affiliation (Lebedev 2005). However, both in sociology and in other sciences (e.g., psychology), there are also different approaches trying to quantify religiosity and determine the level of religiosity of each individual, as well as to examine in further detail the structure of the concept of religiosity itself (Matejević and Stojanović 2020), most often using the dimensions of religiosity and the multi-dimensional approach (Blagojević 2012). In our research, we opted for this approach and in determining the level of university students’ religiosity, we used the scale of religiosity assessment, which was constructed and reduced by Ljubotina, based on the theoretical concept of Glock and Stark (Ljubotina 2004; Stiplošek 2002). The religiosity scale originally had five dimensions of religiosity (belief, ritual, experience, knowledge, consequences) and contained 32 statements. Using the factor analysis, Ljubotina established the presence of three dimensions contained in 24 items. The first dimension is spirituality—which denotes belief and religious experiences of an individual. Religiosity is presented as a personal choice and may be perceived as a primary aspect of religion. In general, in psychological terms, we can see it as intrinsic religiosity in a narrower sense. It is represented by statements such as: “I sometimes feel the presence of God or a Divine being”. The ritual dimension of religiosity is represented by the statements such as “I know basic prayers”. It refers to the practice of different rituals and rites prescribed by the religious community. The third dimension is the influence of religion on behaviour. It is represented by the statements such as “I am not in favour of marriage with a member of other religion”. It refers to the degree of application of religious principles in everyday life. Each sub-scale has eight items, two of which are scored reversely. The result range in the original version of the scale was from 0 to 72, since the respondents answered on a scale from 0—completely false, to 3—completely true. In our research, we used five-degree Likert scale (from 1—I do not agree at all, to 5—I completely agree), on which the respondents assessed the extent to which they agreed with the listed statements. In this manner of assessment, the scores reached on the scale ranged from 24 to 120. The higher result on the scale points to the higher level of religiosity. Moreover, further modification in our research referred to the technical adjustment of the item content, since Ljubotina’s original scale was designed only for Catholic believers (e.g., “I regularly go to places of worship—church, mosque, synagogue, etc.” instead of “I regularly go to church (the temple of God”). In our research, it was done in such a manner as to suit all monotheistic confessions present in our country. However, there is no information whether the previous version used in our country (Gojković et al. 2019; Matejević and Stojanović 2020) was adapted. The reliability of the religiosity scale in our research, as well as in previous research (Matejević and Stojanović 2020) determined Cronbach’s α = 0.96 is quite high, with Cronbach’s α = 0.94. Considering the high coefficients of correlation between the sub-scales, which correlated positively (r = 0.51 to 0.78), and the fact that the sub-scales correlated highly positively with the total score on the religiosity scale (r = 0.74 to 0.94), and that it was to determine the level of religiosity and not of individual components, the further data analysis took into account only the total score in the religiosity questionnaire.

- The university students’ attitudes about various aspects of vaccination:

- (a)

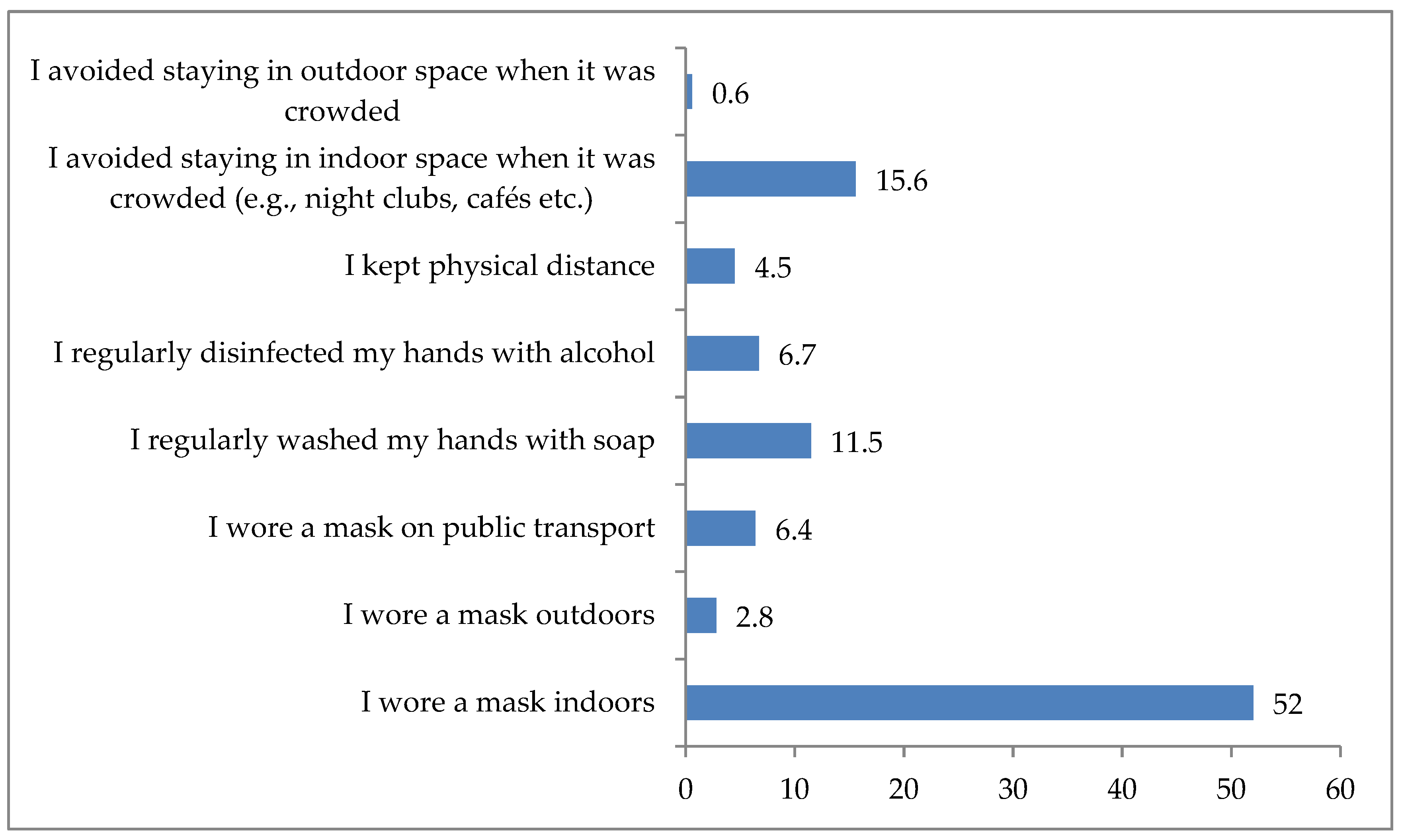

- Whether during the COVID-19 pandemic they observed the prescribed anti-pandemic measures, and if yes, which ones,

- (b)

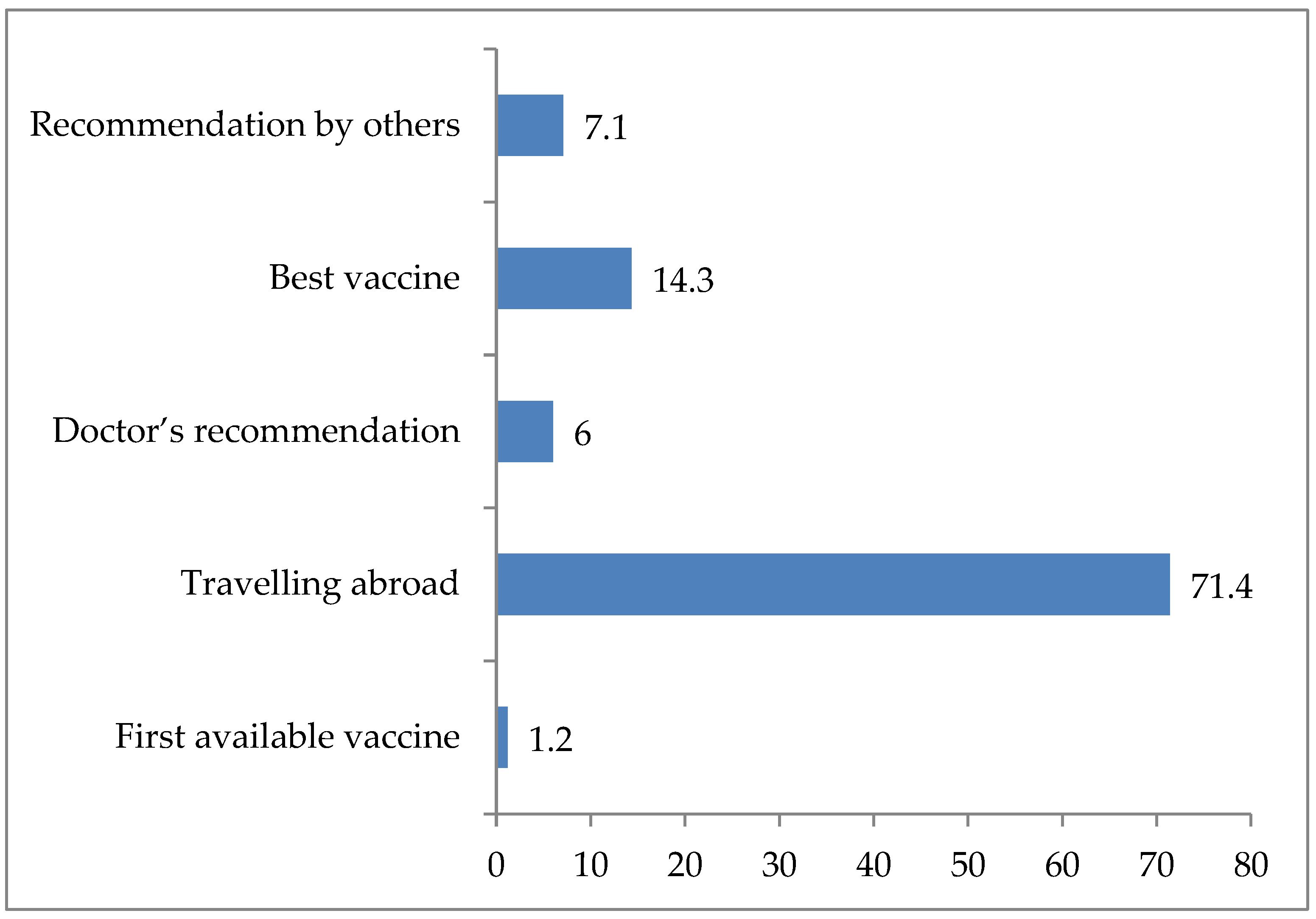

- Whether they are vaccinated, how many doses and which vaccine they had,

- (c)

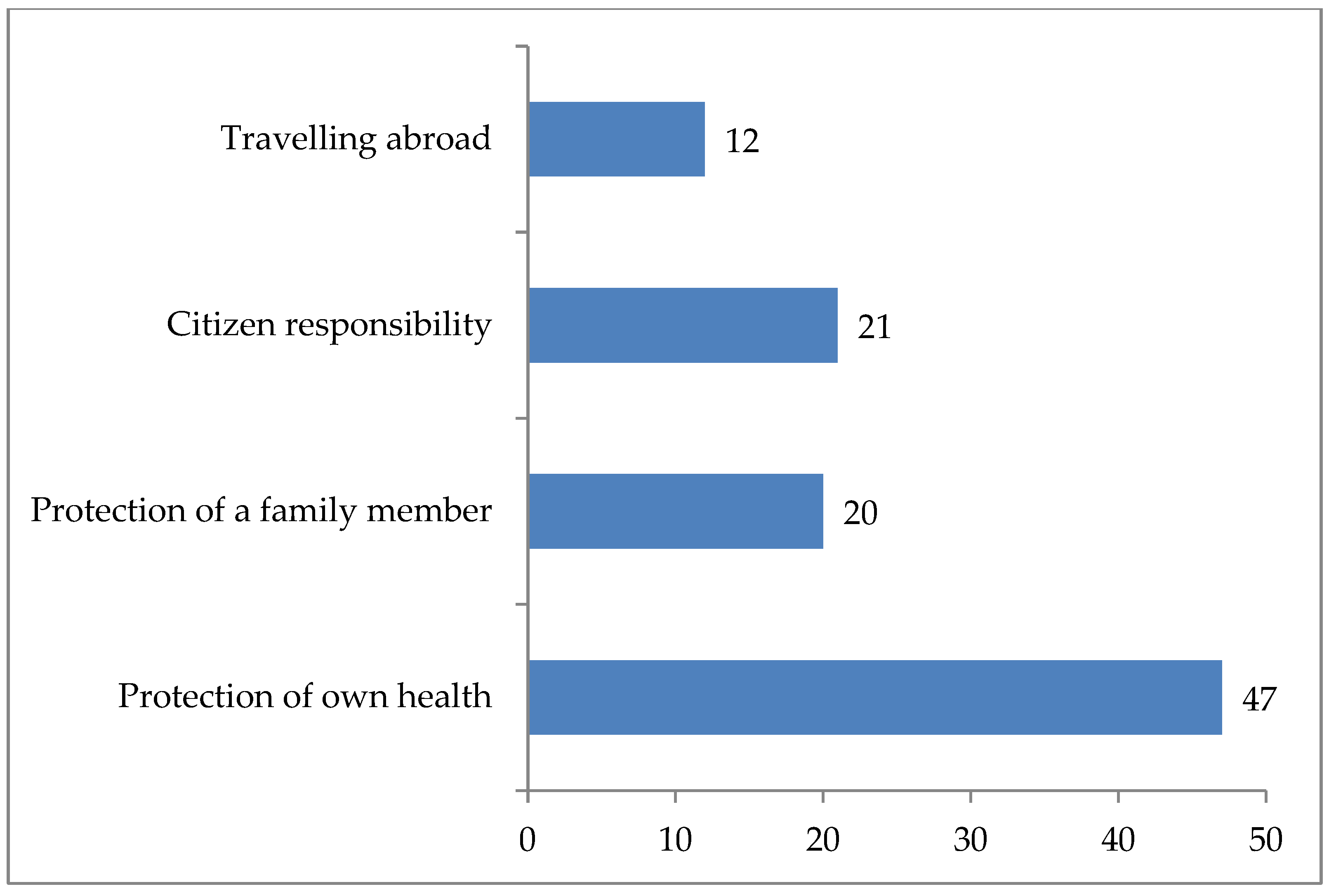

- The university students’ reasons for and vaccination,

- (d)

- The attitude about mandatory anti-COVID-19 vaccination,

- (e)

- The opinion about the way the COVID-19 virus was made,

- (f)

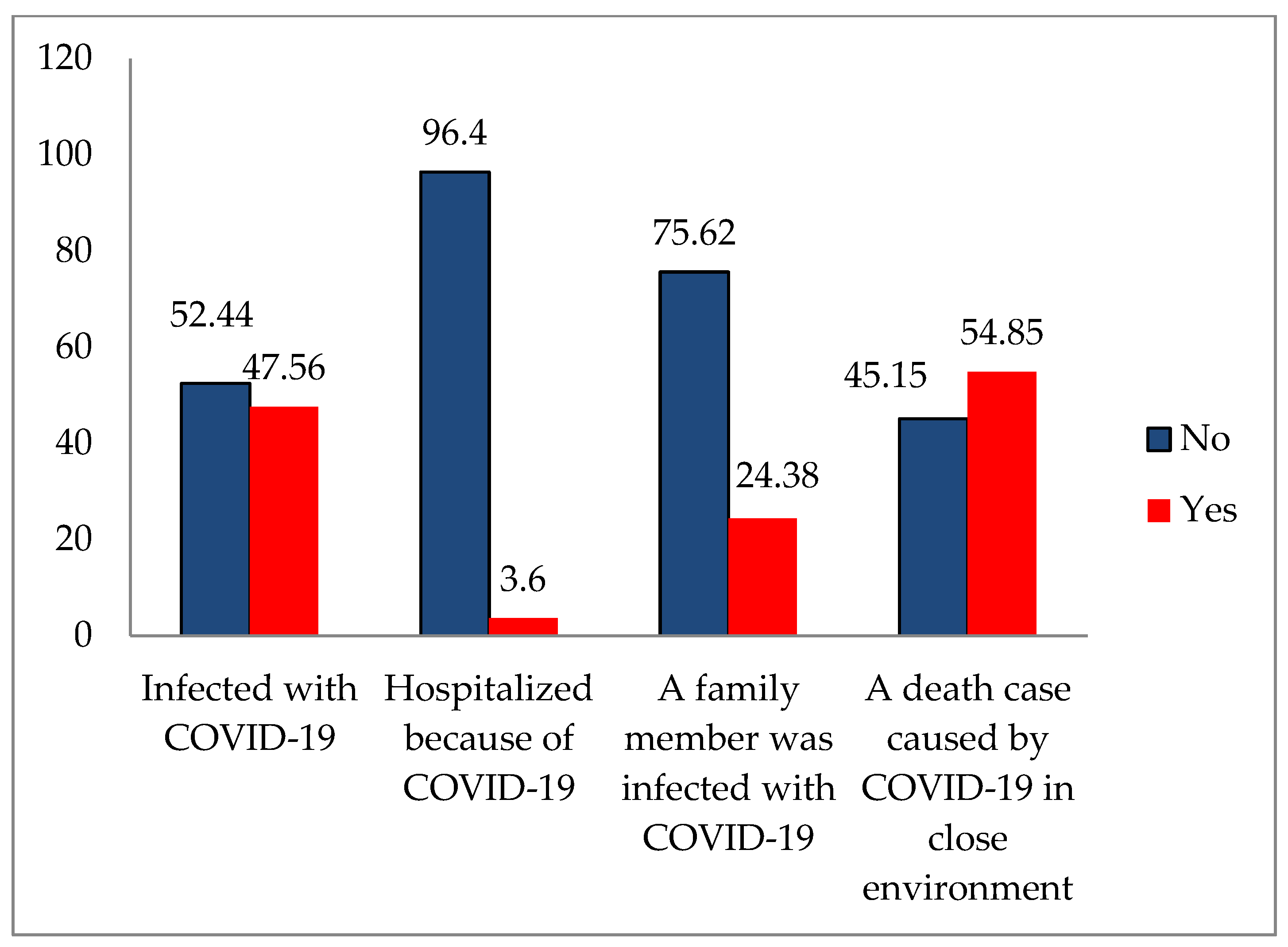

- Experiences with COVID-19 during the pandemic (whether they or some of their family members had COVID-19, whether they were hospitalized and whether there were death cases from COVID-19 in their immediate environment).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “The transmission of coronaviruses follows aviation lines […] Aviation provided the primary entry point for the virus” (Malm and Mealy 2020). |

| 2 | This does not refer only to vaccination. For example, Jehovah’s witnesses do not accept blood transfusion because of religious reasons. |

| 3 | Epidemiologically looking, these terms do not have the same meaning. Self-isolation refers to the legal obligation of a healthy person to be self-isolated during a certain period if he/she has come to our country from abroad, or if he/she was in contact with a potentially infected person, without being aware of it, or if that person belongs to a certain age group, etc. Isolation refers to placing in isolation the person with the COVID-19 symptoms, but has tested negative. Because of the mass character, isolation at home was usually applied. Finally, quarantine refers specifically to staying in hospital, i.e., hospitalization of the infected, particularly those with a more serious form of this disease. When speaking of quarantine measures, in this paper we refer to the whole spectrum of measures which are, naturally, distinguished by epidemiology. |

| 4 | This year, for the first time in the history of the Catholic Church in Serbia, Pope Francis, has appointed László Német, a Belgrade archbishop, for a cardinal. |

| 5 | This trend can also be observed in other Eastern bloc countries after the collapse of real socialism (Berger 1999; Ramet 2014; Kulska 2020; Flere and Klanjšek 2014; Blagojević 2012; Petrović 2011; Petrović and Šuvaković 2013; Vukomanović 2001; Raduški 2018). However, it should be noted that the specific nature of the return to religion in the countries founded after the breakup of Yugoslavia also lies in the fact that religious affiliation was at the same time considered an important feature of national identity (Bodrožić 2014; Mitrović 2021; Šuvaković et al. 2023a; Popić 2024; Vučković 2024; Šuvaković 2024, p. 672). |

| 6 | In one part of schooling, it may be confessional, while in higher grades it may be based on the scientific attitude towards religion as a social phenomenon. However, neither the religious communitiesin Serbia nor the big majority of our respondents would accept the combined model (8%), but would instead choose exclusively the confessional model (62%), while others think that religion should be studied as a social phenomenon (24%) or that it should be displaced from schools (6%) (Šuvaković et al. 2023b). |

| 7 | In Serbia, there are places with the local epidemic of measles due to the non-vaccination of children, although the MMR vaccine is legally prescribed as compulsory. Although the last national epidemic of measles occurred in 2017, it was followed by a substantial decrease in the share of the vaccinated people, thus contributing to local epidemics, for example in Novi Pazar and Tutin (Batut 2023). |

| 8 | The online survey is, by its type, a form of a written survey because it “implies written communication between the interviewer and the respondent”, whereas its specific feature is that it is given in electronic form, i.e., that it is distributed via the Internet (see Šuvaković 2000, pp. 110, 113). |

| 9 | All the data we give for general 18+ population refer to the period until 30 September 2021. Since vaccination continued after that date as well, with undertaking a whole spectrum of measures for its broader scope, the data we have given here should not be considered final, but only precisely processed and available. According to the assessments by some of the members of the Crisis Headquarters for the fight against COVID-19, the share of 18+ population that was vaccinated with minimum two doses until the end of 2022 was not below 60%. We consider these data valid. |

References

- Agley, Jon. 2020. Assessing changes. In US public trust in science amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health 183: 122–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhawari, Yasmin, Marcel A. Verhoff, Hans W. Ackermann, and Markus Parzeller. 2020. Religious denomination influencing attitudes towards brain death, organ transplantation and autopsy—A survey among people of different religions. International Journal of Legal Medicine 134: 1203–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, Sarah N., Wasim Hanif, Kiran Patel, Kamlesh Khunti, and South Asian Health Foundation UK. 2021. Ramadan and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy—A call for action. Lancet 397: 1443–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jayyousi, Ghadir Fakhri, Momamed Abdelhady Mabrouk Sherbash, Lamees Abdullah Momhammed Ali, Asmaa El Heneidy, Nour Waleed Zuhair Alhussaini, Manar Elsheikh Abledrahman Elhassan, and Maisa Ayman Nazzal. 2021. Factors influencing public attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination: A scoping review informed by the socio-ecological model. Vaccines 9: 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allington, Daniel, Siobhan McAndrew, Vivienne Moxham-Hall, and Bobby Duffy. 2023. Corona virus conspiracy suspicions, general vaccine attitudes, trust and corona virus information source as predictors of vaccine hesitancy among UK residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Medicine 53: 236–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allport, Gordon W. 1950. The Individual and His Religion: A Psychological Interpretation. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mohaithef, Mohammed, and Bijaya Kumar Padhi. 2020. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Saudi Arabia: A Web-Based National Survey. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 13: 1657–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, Gabriel. 2021. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, conspiracist beliefs, paranoid ideation and perceived ethnic discrimination in a sample of University students in Venezuela. Vaccine 39: 6837–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonić, Slobodan. 2021. COVID-19, Religion and Moral Panic: The Case of Serbia. In The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social and Psychological Processes. Edited by Vladimir Vuletić. Beograd: Univerzitet u Beogradu, Filozofski fakultet, pp. 87–99. Available online: https://isi.f.bg.ac.rs/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Uticaj-pandemije-kovida-19-na-drustvene-i-psiholoske-procese.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Asprem, Egil, and Asbjørn Dyrendal. 2015. Conspirituality reconsidered: How surprising and hownew is the confluence of spirituality and conspiracy theory? Journal of Contemporary Religion 30: 367–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramović, Sima. 2016. Religious education in public schools and religious identity in post-communist Serbia. Anali pravnog fakulteta u Beogradu 64: 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramović, Zoran, and Rajko Kuljić. 2009. Sociološki pristupi religiji [Sociological approaches to religion]. Sociološki godišnjak 4: 45–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, Afshan, Fu Qiang, Muhammad Ibrahim Abdullah, and Sayd Ali Abbas. 2011. Impact of 5-D of Religiosity on Diffusion Rate of Innovation. International Journal of Business and Social Science 2: 177–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bale, Jeffry M. 2007. Political paranoia vs. Political realism: On distinguishing between bogus conspiracy theories and genuine conspiratorial politics. Patterns of Prejudice 41: 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, David, Kevin Morgan, Tony Towell, Boris Altemeyer, and Viren Swami. 2014. Associations between schizotypy and belief in conspiracist ideation. Personality and Individual Differences 70: 156–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batut. 2022. Report on the Conducted Emergency Recommended Immunization Against COVID-19 in the Territory of the Republic of Serbia in the Period from 24th December 2020 to 30th September 2021. Beograd: Institut za Javno Zdravlje Srbije “Dr Milan Jovanović Batut”. Available online: https://www.batut.org.rs/download/izvestaji/Godisnji%20izvestaj%20o%20sprovedenoj%20imunizaciji%202021.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Batut. 2023. Report on the Immunization Conducted in the Territory of the Republic of Serbia in 2022. Beograd: Institut za Javno Zdravlje Srbije “Dr Milan Jovanović Batut”. Available online: https://www.batut.org.rs/download/izvestaji/2022izvestajOSprovedenojImunizaciji.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Bazić, Jovan. 2011. National identity in the process of political socialization. Srpska politička misao 4: 335–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazić, Jovan, and Bojana Sekulić. 2017. Ideological Objectives and Content in Programs for The First Cycle of Basic Education in Serbia. Politička revija 2: 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begović, Nedim. 2020. Restrictions on Religions due to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Responses of Religious Communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Journal of Law, Religion and State 8: 228–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendau, Antonia, Jens Plag, Moritz Bruno Petzold, and Andreas Ströhle. 2021. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and related fears and anxiety. International Immunopharmacology 97: 107724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benin, Andera L., Daryl J. Wisler-Scher, Eve Colson, Eugene D. Shapiro, and Eric S. Holmboe. 2006. Qualitative analysis of mothers’ decision-making about vaccines for infants: The importance of trust. Pediatrics 117: 1532–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzen, Sinding Jeanet. 2021. In crisis, we pray: Religiosity and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 192: 541–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter L. 1999. The Desecularization of the World: The Global Overview. In The Desecularization of the World: Resurgent Religion and World Politics. Edited by Peter L. Berger. Washington, DC: Ethics and Public Policy Center, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Betsch, Cornelia, and Katharina Sachse. 2013. Debunking vaccination myths: Strong risk negation scan increase perceived vaccination risks. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association 32: 146–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biasio, Luigi Roberto, Guglielmo Bonaccorsi, Chaira Lorini, and Sergio Pecorelli. 2021. Assessing COVID-19 vaccine literacy: A preliminary online survey. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 17: 1304–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierwiaczonek, Kinga, Jonas R. Kunst, and Olivia Pich. 2020. Belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories reduces social distancing overtime. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 12: 1270–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop Irinej of Bačka. 2023. U globalnom Gulagu živimo razapeti između straha i nade [In the global Gulag, we live torn between fear and hope]. Pečat 793: 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop of Raška and Prizren Pavle. 2013. Izveštaji sa raspetog Kosova [Reports from Torn Kosovo]. Beograd: Izdavačka Fondacija Arhiepiskopije Beogradsko-Karlovačke, Fondacija Patrijarh Pavle. [Google Scholar]

- Blagojević, Mirko. 2012. Religious and Confessional Identification and Faith in God among the Citizens of Serbia. Filozofija i društvo 23: 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagojević, Mirko, and Nataša Jovanović-Ajzenhamer. 2021. Religiosity in Serbia and other religiously homogeneous European societies: A comparative perspective. Sociologija 63: 314–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaskiewicz, Robert. 2013. The big Pharma conspiracy theory. Medical Writing 22: 259–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodrožić, Đuro. 2014. Religija i identitet na Balkanu [Religion and identity in the Balkans]. Politička revija 39: 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguszewski, Rafal, Marta Makowska, Marta Bożewicz, and Monika Podkowińska. 2020. The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Religiosity in Poland. Religions 12: 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, Alexandra, Katey Warran, Hei Wan Mak, and Daisy Fancourt D. 2021. The Role of the Arts during the COVID-19 Pandemic; London. Available online: https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/UCL_Role_of_the_Arts_during_COVID_13012022_0.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Cadeddu, Chiara, Martina Sapienza, Carolina Castagna, Luca Regazzi, Andrea Paladini, Walter Ricciardi, and Aldo Rosano. 2021. Vaccine Hesitancy and Trust in the Scientific Community in Italy: Comparative Analysis from Two Recent Surveys. Vaccines 9: 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canete, Jonathan James O. 2021. When expressions of faith in the Philippines becomes a potential COVID-19 ‘superspreader’. Journal of Public Health (Oxford) 43: e366–e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, Manuel. 2022. Ruptura: La Crisis de la Democracia Liberal. Beograd: CLIO. [Google Scholar]

- Catić-Đorđević, Aleksandra, Nikola Stefanović, Ana Spasić, Ivana Damnjanović, Radmila Veličković Radovanović, Boris Đinđić, and Dragana Pavlović. 2021. Current overview of COVID-19 vaccination process in Serbia. Acta Medica Medianae 60: 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhunashvili, Konstantine, Eka Kvirkvelia, and Davit G. Chakhunashvili. 2024. Religious belongings and COVID-19 vaccination. BMC Public Health 24: 2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, Esther. 2018. Are the religious suspicious of science? Investigating religiosity, religious context, and orientations towards science. Public Understanding of Science 27: 967–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Musha, Yanjun Li, Jiaoshan Chen, Ziyu Wen, Fengling Feng, Huachun Zou, Chuanxi Fu, Ling Chen, Yuelong Shu, and Caijun Sun. 2021. An online survey of the attitudes and willingness of Chinese adults to receive COVID-19 vaccination. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 17: 2279–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Tianen, Minhao Dai, Shilin Xia, and Yu Zhou. 2022. Do Messages Matter? Investigating the Combined Effects of Framing, Outcome Uncertainty, and Number Formaton COVID-19 Vaccination Attitudes and Intention. Health Communication 37: 944–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomsky, Noam. 2020. Corona virus—What Is at Stake.DiEM25TV. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t-N3In2rLI4 (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Cichocka, Aleksandra, Marta Marchlewska, Angieszka Golecde Zavala, and Mateusz Olechowski. 2016. They will not control us’: Ingroup positivity and belief in intergroup conspiracies. British Journal of Psychology 107: 556–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čikić, Jovana M., and Ana Lj. Bilinović Rajačić. 2020. Family practices during the pandemic and the state of emergency: The female perspective. Sociološki pregled 54: 799–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cislak, Aleksandra, Marta Marchlewska, Adrian Dominik Wojcik, Kacper Śliwiński, Zuzzana Molenda, Dagmara Szczepańska, and Aleksandra Cichocka. 2021. National narcissism and support for voluntary vaccination policy: The mediating role of vaccination conspiracy beliefs. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 24: 701–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constitution of the Republic of Serbia (Ustav Republike Srbije). 2006. Službeni glasnik 98/2006i115/2021. [Official Gazette No. 98/2006 and 115/2021]. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/ustav_republike_srbije.html (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Čović, Ana V. 2020. Right to privacy and protection of personal data in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sociološki Pregled 54: 670–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čović, Ana, and Oliver Nikolić. 2022. Legal and Social Aspects of Vaccination During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Beograd: Institut Za Uporedno Pravo. Available online: https://iup.rs/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/2022-Pravni-i-dru%c5%a1tveni-aspekti-vakcinacije-tokom-pandemije-kovida-19-1.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Darwin, Hannah, Nick Neave, and Joni Holmes. 2011. Belief in conspiracy theories: The role of paranormal belief, paranoid ideation and schizotypy. Personality and Individual Differences 50: 1289–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deflem, Mathieu. 2022. The Continuity of the Social Sciences during COVID-19: Sociology and interdisciplinarity in Pandemic Times. Society 59: 735–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Đorđević, Katarina. 2024. Svega trećina učenika u Srbiji ide na Građansko vaspitanje [Only one third of students in Serbia attend Civic Education]. Politika. April 8. Available online: https://www.politika.rs/scc/clanak/608099/svega-trecina-ucenika-u-srbiji-ide-na-gradansko-vaspitanje (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Douglas, Karen M., Joseph E. Uscinski, Robbie M. Sutton, Aleksandra Cichocka, Turkay Nefes, Chee Siang Ang, and Farzin Deravi. 2019. Understanding conspiracy theories. Political Psychology 40 Suppl. S1: 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draškić, Marija. 2018. Compulsory vaccination of children: Rights of patients or interest of public health? Anali Pravnog Fakulteta u Beogradu 66: 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drążkowski, Dariusz, and Radoslaw Trepanowski. 2021. I do not need to wash my hands because I will go to Heaven anyway: A study on belief in God and the after life, death anxiety, and COVID-19 protective behaviors. PsyArXiv Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earnshaw, Valerie A., Lisa A. Eaton, Seth C. Kalichman, Natalie M. Brousseau, Carly E. Hill, and Annie B. Fox. 2020. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, health behaviors, and policy support. Translational Behavioral Medicine 10: 850–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecklund, Elaine Howard, and Christopher P. Scheitle. 2018. Religion vs. Science: What Religious People Really Think, 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eguia, Hans, Franco Vinciarelli, Marina Bosque-Prous, Troels Kristensen, and Francesc Saigí-Rubió. 2021. Spain’s Hesitation at the Gates of a COVID-19 Vaccine. Vaccines 9: 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erikson, Erik H. 1982. The Life Cycle Completed (Extended Version). New York: W. W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, Kimmo, and Irina Vartanova. 2022. Vaccine confidence is higher in more religious countries. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics 18: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmer, Yilmaz, and Thorleif Pettersson. 2007. The effects of religion and religiosity on voting behavior. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior. Edited by Rusell J. Dalton and Hans-Dieter Klingemann. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 481–503. [Google Scholar]

- Farias, Miguel. 2013. The psychology of atheism. In The Oxford Handbook of Atheism. Edited by Stephen Bullivant and Michael Ruse. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 468–82. [Google Scholar]

- Farkhari, Fahima, Berd Schlipphak, and Mitja D. Back. 2022. Individual- level predictors of conspiracy mentality in Germany and Poland. Politics and Governance 10: 203–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flere, Sergej, and Rudi Klanjšek. 2014. Was Tito’s Yugoslavia totalitarian? Communiste and Post-Communiste Studies 47: 237–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, Daniel, and Richard P. Bentall. 2017. The concomitants of conspiracy concerns. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 52: 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, Marius, Michał Bilewicz, and Roland Imhoff. 2023. On the relation between religiosity and the endorsement of conspiracy theories: The role of political orientation. Political Psychology 44: 139–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, Paul, and Rory Jones. 2021. The Sociology of Prayer: Dimensions and Mechanisms. Social Sciences 10: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galang, Joseph Renus F. 2021. Science and religion for COVID-19 vaccine promotion. Journal of Public Health 43: 513–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, Louiegi L., and John Frederik C. Yap. 2021. The role of religiosity in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Journal of Public Health 43: 529–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavrilović, Danijela, and Dragoljub B. Đorđević. 2018. Religionization of Public Space: Symbolic Struggles and Beyond—The Case of Ex-Yugoslav Societies. Religions 9: 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goertzel, Ted. 1994. Belief in conspiracy theories. Political Psychology 15: 731–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gojković, Vesna, Marija Plahuta, and Jelena Dostanić. 2019. Narcizam SD3 i narcizam modela NARC: Sličnosti i razlike [The SD3 measure of narcissism and the narcissism of the NARC model: Differences and similarities]. Zbornik Instituta za Kriminološka i Sociološka Istraživanja 38: 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Serbia. 2001. Uredba o organizovanju I ostvarivanju verske nastave i nastave alternativnih predmeta u osnovnoj I srednjoj školi [Regulation on the Organization and Realization of Religious Education and Alternative Subjects in Primary and Elementary Schools]. Službeni glasnik RS, 46. Available online: https://pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/eli/rep/sgrs/vlada/uredba/2001/46/1/reg (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Gowda, Charita, and Amanda F. Dempsey. 2013. The rise (and fall?) of parental vaccine hesitancy. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 9: 1755–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Martin Ejnar, and Steven David Pickering. 2024. The role of religion and COVID-19 vaccine uptake in England. Vaccine 42: 3215–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harapan, Harapan, Naoya Itoh, Amanda Yufika, Wira Winardi, Synat Keam, Haypheng Te, Dewi Megawati, Zinatul Hayati, Abram L. Wagner, and Mudatsir Mudatsir. 2020. Corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A literature review. Journal of Infection and Public Health 13: 667–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, David. 2020. Anti–capitalist politics in the time of COVID-19. Jacobin. March 20. Available online: https://jacobin.com/2020/03/david-harvey-coronavirus-political-economy-disruptions (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Hatala, Andrew, Maryjam Chloé Pervaiz, Richard Handley, and Tara Vijayan. 2022. Faith based dialogue can tackle vaccine hesitancy and build trust. British Medical Journal 376: o823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, Roland, and Martin Bruder. 2014. Speaking (un-)truth to power: Conspiracy mentality as a generalized political attitude. European Journal of Personality 28: 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanović, Stanoje. 2015. Obrazovanje između religije i sekularizacije [Education between religion and secularization.]. Inovacije u Nastavi 28: 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabkowski, Piotr, Jan Domaradzki, and Mariusz Baranowski. 2023. Exploring COVID-19 conspiracy theories: Education, religiosity, trust in scientists, and political orientation in 26 European countries. Scientific Reports 13: 18116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandrić Kočić, Marijana. 2022. Reasons and determinants of distrust in COVID19 vaccine. Medicinski Glasnik Specijalne Bolnice za Bolesti štitaste žlezde i Bolesti Metabolizma “Zlatibor” 84: 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Sung Joon, Matt Bradshaw, Charoltte V. O. Witvliet, Young-Il Kim, Byron R. Johnson, and Joseph Leman. 2023. Transcendent Accountability and Pro-Community Attitudes: Assessing the Link Between Religion and Community Engagement. Review of Religious Research 65: 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janjić, Jovan. 2018. Srpska pravoslavna crkva u komunizmu i postkomunizmu [Serbian Orthodox Church in Communism and Post-Communism]. Beograd: Novosti. [Google Scholar]

- Janković, Stefan S. 2020. Social after pandemic distortion: Towards thinking in planetary terms. Sociološki Pregled 54: 1008–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinskaja-Lahti, Inga, and Jolanda Jetten. 2019. Unpacking the relationship between religiosity and conspiracy beliefs in Australia. The British Journal of Social Psychology 58: 938–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jedinger, Alexander, and Pascal Siegers. 2024. Religion, spirituality, and susceptibility to conspiracy theories: Examining the role of analytic thinking and post-critical beliefs. Politics and Religion 17: 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevtović, Zoran B., and Predrag Đ. Bajić. 2020. The image of COVID-19 in the Serbian daily newspapers. Sociološki Pregled 54: 534–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Shihui, Alex R. Cook, Robert Kanwagi, Heidi J. Larson, and Leesa Lin. 2024. Comparing role of religion in perception of the COVID-19 vaccines in Africa and Asia Pacific. Communications Medicine 4: 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolley, Daniel, and Karen M. Douglas. 2014. The social consequences of conspiracism: Exposure to conspiracy theories decreases intentions to engage in politics and to reduce one’s carbon footprint. British Journal of Psychology 105: 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanović, Aleksa, Jovana Maričić, Gorica Marić, and Tatjana Pekmezović. 2023. Are the final– year medical students competent enough to tackle the immunization challenges in their practice? Vojnosanitetski Pregled 80: 208–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jović, Dejan. 2020. Pandemic crisis and its challenges to security studies. Sociološki Pregled 54: 471–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat, Geoffrey C. 2017. Taking distrust of science seriously. EMBO Report 18: 1052–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, Aaron C., Danielle Gaucher, Ian McGregor, and Kyle Nash. 2010. Religious belief as compensatory control. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khankeh, Hamid Reza, Mehrdad Farrokhi, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, Yadollah Abolfathi Momtaz, Ameneh Setareh Forouzan, Mehdu Norouzi, Shokoufeh Ahmadi, Gholamreza Ghaedamini Harouni, Juliet Roudini, Elham Ghanaatpisheh, and et al. 2021. The Barriers, Challenges, and Strategies of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) Vaccine Acceptance: A Concurrent Mixed-Method Study in Tehran City, Iran. Vaccines 9: 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilic, Mahmut, Nursel Ocal Ustundag, and Gullu Uslukilic. 2021. The COVID ship of COVID-19 vaccine attitude with life satisfaction, religious attitude and COVID-19 avoidance in Turkey. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 17: 3384–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kljakić, Ljubomir. 2022. Velika polarizacija: Sociologija Sars 2 COVID19 kapitalizma [The Great Polarization. Sociology of Sars 2 Covid19 Capitalism]. Nacionalni Interes 41: 9–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, Joachim, Marta Marchlewska, Zuzanna Molenda, Paulina Górska, and Łukasz Gawęda. 2020. Adherence to safety and self-isolation guidelines, conspiracy and paranoia-like beliefs during COVID-19 pandemic in Poland-associations and moderators. Psychiatry Research 294: 113540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuburić, Zorica, and Nenad Stojković. 2004. Religijski self u transformaciji: Društvene promene i religioznost građana Vojvodine [Religious self in transformation, social changes and religiosity of citizens in Vojvodina]. Sociološki Pregled 38: 321–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulska, Joanna. 2020. Bridging the Nation and the State: Catholic Church in Poland As Political Actor. Politics and Religion 14: 263–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladini, Riccardo. 2022. Religious and conspiracist? Ananalysis of the relationship between the dimensions of individual religiosity and belief in a big Pharma conspiracy theory. Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica 52: 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahav, Eyal, Shosh Shahrabani, Mosi Rosenboim, and Yoshiro Tsutsui. 2022. Is stronger religious faith associated with a greater willingness to take the COVID-19 vaccine? Evidence from Israel and Japan. The European Journal of Health Economics: HEPAC: Health Economics in Prevention and Care 23: 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, Heidi J., Emmanuela Gakidou, and Christopher J.L. Murray. 2022. The Vaccine-Hesitant Moment. The New England Journal of Medicine 387: 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law on Churches and Religious Communities [Zakon o crkvama i verskim zajednicama]. 2006. Službeni glasnik RS, 36. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_crkvama_i_verskim_zajednicama.html (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Lazarus, Jeffrey V., Katarzyna Wyka, Trenton M. White, Camila A. Picchio, Kenneth Rabin, Scott C. Ratzan, Jeanna Parsons Leigh, Jia Hu, and Ayman El-Mohandes. 2022. Revisiting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy around the world using data from 23 countries in 2021. Nature Communications 13: 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, Jeffrey V., Scott C. Ratzan, Adam Palayew, Lawrence O. Gostin, Heidi J. Larson, Kenneth Rabin, Spencer Kimball, and Ayman El-Mohandes. 2021. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nature Medicine 27: 225–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebedev, Sergey Dmitrievič. 2005. Religioznost’: V poiskakh “Rubikona” [Religiosity: In Search of the Rubicon]. Sotsiologicheskiy Zhurnal 3: 153–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Mikyung, Heejun Lim, Merin Shobhana Xavier, and Eun-Young Lee. 2022. “A Divine Infection”: A Systematic Review on the Roles of Religious Communities During the Early Stage of COVID-19. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 866–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, Magdalena, and Konrad S. Jankowski. 2022. Religiosity and the Spread of COVID-19: A Multinational Comparison. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 1641–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljubotina, Damir. 2004. Razvoj novog instrumenta za mjerenje religioznosti. [Development of the new instrument for religiosity measurement]. In Dani psihologije u Zadru [Days of Psychology in Zadar]. Edited by Vera Ćubela Adorić, Ilija Manenica and Zvjezdan Penezić. Zadar: Sveučilište u Zadru, pp. 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- López-Cepero, Andera, McClaren Rodríguez, Veronica Joseph, Shakira F. Suglia, Vivian Colón-López, Yiana G. Toro-Garay, Maria D. Archevald-Cansobre, Emma Fernández-Repollet, and Cynthia M. Pérez. 2022. Religiosity and Beliefs toward COVID-19 Vaccination among Adults in Puerto Rico. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 11729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loveland, Matthew T., David Sikkink, Daniel J. Myers, and Benajmin Radcliff. 2005. Private Prayer and Civic Involvement. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 44: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łowicki, Paweł, Marta Marchlewska, Zuzanna Molenda, Adam Karakula, and Dagmara Szczepańska. 2022. Does religion predict corona virus conspiracy beliefs? Centrality of religiosity, religious fundamentalism, and COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences 187: 111413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukić, Aleksandar. 2023. Pandemization and the New Normal. Politička revija 58: 139–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, Aleksandar R., and Valentina S. Arsić Arsenijević. 2023. Logic and the scientific method: Virus and tobacco mosaic disease: What we know about infectious agents. Sociološki pregled 57: 297–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleva, Tatiana M., Marina A. Kartseva, and Sophia V. Korzhuk. 2021. Socio-demographic determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake in Russia in the context of mandatory vaccination of employees. Population and Economics 5: 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malm, Andreas, and Dominic D. Mealy. 2020. An Interview with Andreas Malm. To Halt Climate Change, We Needan Ecological Leninism. Jacobin. June 15. Available online: https://jacobin.com/2020/06/andreas-malm-coronavirus-covid-climate-change (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Mancosu, Moreno, Salvatore Vassallo, and Cristiano Vezzoni. 2017. Believing in conspiracy theories: Evidence from an exploratory analysis of Italian survey data. South European Society and Politics 22: 327–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Zhe-Fei, Qui-Wei Li, Yi-Ming Wang, and Jie Zhou. 2024. Pro-religion attitude predicts lower vaccination coverage at country level. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11: 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchlewska, Marta, Aleksandra Cichocka, Filip Łozowski, Paulina Górska, and Mikołaj Winiewski. 2019. In search of an imaginary enemy: Catholic collective narcissism and the endorsement of gender conspiracy beliefs. The Journal of Social Psychology 159: 766–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, Anđela. 2018. Uticaj porodice na opredeljivanje učenika za Versku nastavu ili Građansko vaspitanje [The Family Influence on the Pupils Selection Between Religious Education or Civic Education]. Master’s thesis, Filozofski fakultet, Novi Sad, Serbia. Available online: https://remaster.ff.uns.ac.rs/materijal/punirad/Master_rad_20180125_soc_360008_2015.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Marshall, Katherine. 2022. COVID-19 and Religion: Pandemic Lessons and Legacies. The Review of Faith & International Affairs 20: 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, Katherine, Olivia Wilkinson, and Dave Robinson. 2020. Religion and COVID-19: Four Lessons from the Ebola Experience. From Poverty to Power. Available online: https://oxfamapps.org/fp2p/religion-and-covid-19-four-lessons-from-the-ebola-experience (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Martens, Jason P., and Bastiaan T. Rutjens. 2022. Spirituality and religiosity contribute to ongoing COVID-19 vaccination rates: Comparing 195 regions around the world. Vaccine: X 12: 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashuri, Ali, and Esti Zaduqisti. 2014. The role of social identification, intergroup threat, and out-group derogation in explaining belief in conspiracy theory about terrorism in Indonesia. International Journal of Research Studies in Psychology 3: 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matejević, Marina, and Svetlana Stojanović. 2020. Vaspitni stil roditelja i religioznost studenata [Parenting style and students’ religiosity]. Godšnjak za Pedagogiju 5: 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthewman, Steve. 2021. Social Science in the Time of COVID-19. Sites: New Series 18: 80–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević, Zoran. 2011. Religion and National Identity: From Proselytism to Modern Social Technologies. Srpska Politička Misao 4: 355–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. 2024. Lista nastavnika verske nastave za školsku 2024/25. godinu na predlog tradicionalnih crkava i verskih zajednica. [List of Religious Education teachers for the 2024/25 School Year. Year at the Suggestion of Traditional Churches and Religious Communities]. Available online: https://prosveta.gov.rs/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Lista-nastavnika-verske-nastave-2024-2025.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Ministry of Justice. 2024. Spisak crkava i verskih zajednica [List of Churches and Religious Communities]. Available online: https://www.mpravde.gov.rs/registar/1138/spisak-crkava-i-verskih-zajednica-.php (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Mirović, Dejan M. 2020. Violation of universal human rights and persecution of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Montenegro during the COVID-19 epidemic. Sociološki Pregled 54: 720–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrović, Jelena, Sandra Knežević, Jelena Žugić, Milica Kostić-Stanković, Marija Jović, and Radmila Janičić. 2019. Creating social marketing strategy on the internet with in preventive healthcare— Human papilloma virus vaccination campaign. Srpski Arhiv za Celokupno Lekarstvo 147: 355–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrović, Milovan. 2021. Phenomenology and Dialectics of the Serbian Identity. In Nation and Education. Edited by Srđan Šljukić and Slobodan Vladušić. Novi Sad: Matica srpska, pp. 189–220. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, Nurul Azmawati, Hana Maizuliana Solehan, Mohd Dzulkhairi Mohd Rani, Muslimah Ithnin, and Che Ilina Che Isahak. 2021. Knowledge, acceptance and perception on COVID-19 vaccine among Malaysians: A web-based survey. PLoS ONE 16: e0256110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, Mark, Roderick Duncan, and Kevin Parton. 2015. Religion Does Matter for Climate Change Attitudes and Behavior. PLoS ONE 10: e0134868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscovici, Serge. 1987. The conspiracy mentality. In Changing Conceptions of Conspiracy. Edited by Carl F. Graumann and Serge Moscovici. New York: Springer, pp. 151–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mugano, Gift. 2020. The economy nexus of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sociološki Pregled 54: 737–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newheiser, Anna-Kaisa, Miguel Farias, and Nicole Tausch. 2011. The functional nature of conspiracy beliefs: Examining the underpinnings of belief in the Da Vinci Code conspiracy. Personality and Individual Differences 51: 1007–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, Ivko A., and Jelena R. Petrović. 2024. The Relationship of Religious Confession and Attitudes Towards Vaccination Against COVID-19 with Attendance of Civic Education and Religious Teaching During Previous Educational Levels of Students of Teacher-Training Faculties. In Education Through the COVID-19 Pandemic Vol. 1: Pedagogical, Didactic and Methodological Aspects. Edited by Danimir P. Mandić, Sanja R. Blagdanić and Ivko A. Nikolić. Belgrade: University of Belgrade—Faculty of Education, pp. 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2004. Sacred and secular. In Religion and Politics Worldwide, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ofri, Danielle. 2009. The emotional epidemiology of H1N1 influenza vaccination. The New England Journal of Medicine 361: 2594–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, Eric J., and Thomas J. Wood. 2014. Conspiracy theories and the paranoid style(s) of mass opinion. American Journal of Political Science 58: 952–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opel, Douglas J., James A. Taylor, Rita Mangione- Smith, Cam Solomon, Chuan Zhao, Sheryl Catz, and Diane Martin. 2011. Validity and reliability of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents. Vaccine 29: 6598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantić, Dragomir J. 1993. Promene religioznosti građana Srbije [The changes of religiousness in Serbia]. Sociološki pregled 27: 177–204. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Charlie, Sam Scott, and Alastair Geddes. 2019. Snowball Sampling. In Research Methods Foundation. Edited by Paul Atkinson, Sara Delamont, Alexandru Cernat, Joseph W. Sakshaug and Richard A. Williams. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publication Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlović, Nina M., and Jasmina S. Petrović. 2020. Trust and subjective well-being in Serbia during the pandemic: Research results. Sociološki Pregled 54: 560–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, Ed, Clarissa Simas, and Heidi J. Larson. 2022. An epidemic of uncertainty: Rumors, conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy. Natural Medicine 28: 456–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, Jasmina. 2011. Vrednosni stavovi studenata: Religioznost, prosocijalni stavovi i odnos prema budućnosti [Value attitudes of Belgrade university students: Religiosity, prosocial attitudes, the attitudes towards future]. In Godišnjak Srpske akademije obrazovanja za 2010. Beograd: Srpska akademija obrazovanja, pp. 881–96. Available online: http://www.sao.org.rs/documents/G2010_2x.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2024)).

- Petrović, Jasmina S., and Vesna D. Miltojević. 2023. Life in the Time of Corona virus: Contribution to the Study of Specific Socio-Ecological Attitudes and Practices During the COVID-19 Pandemic. In In Honor of Professor Đorđe Tasić: Life, Works and Echoes. Edited by Slobodan Miladinović and Ana Vuković. Belgrade: Serbian Sociological Association, pp. 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, Jasmina, and Uroš Šuvaković. 2013. Religioznost, konfesionalna distance i mesto verske pripadnosti u strukturi identiteta studenata u Kosovskoj Mitrovici [Religiosity, confessional distance and the place of religious affiliation in the identity structure of the students in Kosovska Mitrovica]. In Nacionalni identitet i religija [National Identity and Religion]. Edited by Zoran Milošević and Živojin Đurić. Beograd: Institut za političke studije, pp. 245–64. [Google Scholar]

- Petrović, Jelena, Srđan Dimić, and Srđan Ljubojević. 2021. Attitudes of defence and security sector member’s towards urban public transport service during COVID-19 state of emergency. Teme 45: 1311–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pipes, Dainel. 1997. Conspiracy: How the Paranoid Style Flourishes and Where It Comes From. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Pirutinsky, Steven, Aaron D. Cherniak, and David H. Rosmarin. 2020. COVID-19, Mental Health, and Religious Coping Among American Orthodox Jews. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogue, Kendall, Jamie L. Jensen, Carter K. Stancil, Daniel G. Ferguson, Savannah J. Hughes, Emilly J. Mello, Ryan Burgess, Bradford K. Berges, Abraham Quaye, and Brian D. Poole. 2020. Influences on Attitudes Regarding Potential COVID-19 Vaccination in the United States. Vaccines 8: 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popić, Snežana S. 2024. The sustainability of ethno-religious identity as the dominant form of collective identification in Kosovo and Metohija. Sociološki Pregled 58: 324–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, Karl. 1962. Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Radovanović, Zoran. 2017. Anti-vaccinationists and their arguments in the Balkan countries that share the same language. Srpski Arhiv za Celokupno Lekarstvo 145: 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulović, Srđan. 2022. Non-promulgation of mandatory COVID-19 vaccination in the Republic of Serbia. Zbornik Radova Pravnog Fakulteta u Nišu 61: 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raduški, Nada. 2018. Jezička i religijska komponenta nacionalnog identiteta stanovništva Srbije [Language and Religious component of the national identity of the population in Serbia]. In Nacionalni identitet i etnički odnosi. Edited by Nada Raduški. Beograd: Institut za političke studije, pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ramet, Sabrina P., ed. 2014. Religion and Politics in Post-Socialist Central and Southeastern Europe: Chalanges Since 1989. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Republički Zavod za Statistiku (RZS). 2021. Visoko Obrazovanje 2020/2021. [Higher Education 2020/2021]; Belgrade: Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Available online: https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G2021/pdf/G20216006.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Republički Zavod za Statistiku (RZS). 2022. CENSUS 2022—EXCEL TABLE: Population by Religion, by Municipalities and Cities. Available online: https://popis2022.stat.gov.rs/en-US/popisni-podaci-eksel-tabele (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Ristivojević, Branislav R., and Stefan S. Samardžić. 2018. When Health care becomes Criminal Policy: Vaccination before the Constitutional Court of Serbia (II Part). Zbornik Radova Pravnog Fakulteta u Novom Sadu 52: 547–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, David George. 2017. The hidden hand: Why religious studies need to take conspiracy theories seriously. Religion Compass 11: e12233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, David George, Egil Asprem, and Asbjørn Dyrendal. 2018. Introducing the field: Conspiracy theory in, about, and as religion. In Handbook of Conspiracy Theory and Contemporary Religion. Edited by Asbjørn Dyrendal, David George Robertson and Egil Asprem. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Romer, Daniel, and Kathleen Hall Jamieson. 2020. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the US. Social Science & Medicine 263: 113356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutjens, Bastiaan T., and Aaron C. Kay. 2017. Compensatory control theory and the psychological importance of perceiving order. In Coping with Lack of Control in a Social World. Edited by Marcin Bukowski, Immo Fritsche, Ana Guinote and Mirosław Kofta. London: Routledge, pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rutjens, Bastiaan T., Sander van der Linden, and Romy van der Lee. 2021. Science skepticism in times of COVID-19. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 24: 276–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, Malik, Deema Dababseh, Huda Eid, Kholoud Al-Mahzoum, Ayat Al-Haidar, Duaa Taim, Alaa Yaseen, Nidaa A. Ababneh, Faris G. Bakri, and Mahafzah Azmi. 2021. High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries. Vaccines 9: 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, Sonia. 2020. Religious discrimination is hindering the COVID-19 response. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 369: m2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savić Marković, Olivera S. 2020. Crisis and organised control: The COVID-19 pandemic and power of surveillance. Sociološki Pregled 54: 647–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Shalom H., and Sipke Huismans. 1995. Value priorities and religiosity in four Western religions. Social Psychology Quarterly 58: 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisti, Leuconoe Grazia, Danilo Buonsenso, Umberto Moscato, and Walter Malorni. 2022. COVID-19 and religion: Evidence and implications for future public health challenges. European Journal of Public Health 32 Suppl. S3: ckac130.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisti, Leuconoe Grazia, Danilo Buonsenso, Umberto Moscato, Gianfranco Costanzo, and Walter Malorni. 2023. The Role of Religions in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slijepčević Bjelivuk, Svetlana, and Marina Nikolić. 2022. COVID-19 Dictionary. Beograd: Institut za srpski jezik SANU. Novi Sad: Prometej. [Google Scholar]

- Stanojević, Dragana Z., Miljana S. Pavićević, Tijana Lj. Živković, Olivera B. Radović, and Biljana N. Jaredić. 2022. Health beliefs and health anxiety as predictors of COVID-19 health behavior: Data from Serbia. Zbornik Radova Filozofskog Fakulteta u Prištini 52: 301–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasielowicz, Lukasz. 2022. Who believes in conspiracy theories? A meta-analysis on personality correlates. Journal of Research in Personality 98: 104229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, Monica. 2020. A geospatial infodemic: Mapping Twitter conspiracy theories of COVID-19. Dialogues in Human Geography 10: 276–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilhoff, Sörensen Jens. 2020. Terror in utopia: Crisis (mis-)management during the COVID-19 pandemic in Sweden. Sociološki Pregled 54: 961–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiplošek, Danijela. 2002. Povezanost religioznosti, samopoštovanja i lokusa kontrole [Connection of Religiosity, Self-Respect and Locus Control]. Graduation paper. Zagreb: Filozofski Fakultet. [Google Scholar]

- Sturgis, Patrick, Ian Brunton-Smith, and Jonathan Jackson. 2021. Trust in science, social consensus and vaccine confidence. Nature Human Behavior 5: 1528–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulkowski, Lukasz, and Grzegorz Ignatowski. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Organization of Religious Behaviour in Different Christian Denominations in Poland. Religions 5: 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuvaković, Uroš V. 2000. Ispitivanje političkih stavova. [Examination of Political Attitudes]. Beograd: Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva. [Google Scholar]

- Šuvaković, Uroš V. 2020a. On the methodological issue of uncritical adoption of concepts using the example of the concept of “social distance” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sociološki Pregled 54: 445–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuvaković, Uroš V. 2020b. Reflections on the pandemic: A view from Serbia. In Reflections During the Pandemic. Edited by Chetty Dassarath. Durban: Durban University of Technology (South Africa): International Sociological Association (ISA, RC10), Madrid: Faculty of Political Sciences and Sociology, University Complutense, pp. 21–22. Available online: https://www.isa-sociology.org/frontend/web/uploads/files/rc10-Reflections%20during%20the%20Pandemic.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Šuvaković, Uroš V. 2022. Pandemija COVID-19 i globalni kapitalizam [COVID-19 Pandemic and Global Capitalism]. Srpska Politička Misao 76: 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuvaković, Uroš V. 2024. Anti-fascism as a determinant of Serbian national identity. Sociološki Pregled 58: 645–76. [Google Scholar]

- Šuvaković, Uroš V., Ivko A. Nikolić, and Jelena R. Petrović. 2022. University classes during the state of emergency in Serbia introduced after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: Students’ attitudes. Zbornik Instituta za Pedagoška Istrazivanja 54: 241–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuvković, Uroš V., Ivko A. Nikolić, and Jelena R. Petrović. 2023a. Verska nastava u Srbiji dve decenije posle uvođenja u školski sistem: Mišljenja studenata i njihovi stavovi po srodnim pitanjima [Religious education in Serbia two decades after its introduction in the school system: Opinions of students and their attitudes on related issues]. Nacionalni Interes 46: 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuvaković, Uroš V., Jelena R. Petrović, and Ivko A. Nikolić. 2023b. Confessional Instruction or Religious Education: Attitudes of Female Students at the Teacher Education Faculties in Serbia. Religions 14: 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, Viren, Rebecca Coles, Stefan Stieger, Jakob Pietschnig, Adrian Furnham, Sherry Rehim, and Martin Voracek. 2011. Conspiracist ideation in Britain and Austria: Evidence of a monological belief system and associations between individual psychological differences and real-world and fictitious conspiracy theories. British Journal of Psychology 102: 443–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, Stipe, Erik Brezovec, and Iva Tadić. 2022. Društvo (COVID-19) rizika—između instrumentalne i aksiološke racionalnosti [The Risk (COVID-19) Society—Between Instrumental and Axiological Rationality]. Obnovljeni Život: Časopis za Filozofiju i Religijske Znanosti 77: 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Min Min, Ahmad Farouk Musa, and Tin Tin Su. 2022. The role of religion in mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic: The Malaysian multi-faith perspectives. Health Promotion International 37: daab041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teličák, Peter, and Peter Halama. 2021. Maladaptive personality traits, religiosity and spirituality as predictors of epistemically unfounded beliefs. Studia Psychologica 63: 175–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorović, Dragan. 2013. Religious Education in Schools: Contribution or Not to Dialogue and Tolerance? In On Religion in the Balkans. Edited by Dragoljub B. Đorđević. Niš: Yugoslav Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, Sofia: “Ivan Hadzijski”, pp. 181–89. Available online: https://npao.ni.ac.rs/files/584/18_Dragan_Todorovic_01c33.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Todorović, Dragan M., Dragoljub B. Đorđević, and Zorica S. Kuburić. 2024. Religious catechism in Serbian schools since 1990 until today: Reasons for implementation, actual situation and perspectives. Sociološki pregled 58: 402–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepanowski, Radoslaw, and Dariusz Drążkowski. 2022. Cross-National Comparison of Religion as a Predictor of COVID-19 Vaccination Rates. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 2198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifunović, Vesna S. 2014. Education, Religion and Identity. In Science—Religion—Education. Edited by Vladeta Jerotić, Mirko Dejić and Miodrag Vuković. Beograd: Učiteljski fakultet Univerziteta u Beogradu, pp. 192–206. [Google Scholar]

- Tsekeris, Charalambos, and Persefoni Zeri. 2020. The corona virus crisis as a world-historic event in the digital era. Sociološki Pregled 54: 498–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukropina, Snežana, Mioljub Ristić, Vesna Mijatović-Jovanović, Sonja Šušnjević, Vladimir Vuković, and Miloš Marković. 2022. Predictors of vaccination against Corona virus disease 2019 in Serbia. Medicinski Pregled 75: 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upenieks, Laura, Joanne Ford Robertson, and James E. Robertson. 2022. Trust in God and/or Science? Sociodemographic Differences in the Effects of Beliefs in an Engaged God and Mistrust of the COVID-19 Vaccine. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 657–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uscinski, Joseph E., and Joseph M. Parent. 2014. American Conspiracy Theories. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Prooijen, Jan-Willem. 2017. Why education predicts decreased belief in conspiracy theories. Applied Cognitive Psychology 31: 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Prooijen, Jan-Willem, and Karen M. Douglas. 2018. Belief in conspiracy theories: Basic principles of an emerging research domain. European Journal of Social Psychology 48: 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Prooijen, Jan-Willem, and Paul A.M. van Lange. 2014. The social dimension of belief in conspiracy theories. In Power, Politics, and Paranoia. Why People Are Suspicious of Their Leaders. Edited by Jan-Wilem van Prooijen and Paul A.M. Lange. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 237–53. [Google Scholar]

- van Prooijen, Jan-Willem, André P.M. Krouwel, and Thomas V. Pollet. 2015. Political extremism predicts belief in conspiracy theories. Social Psychological and Personality Science 6: 570–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasojević, Nena A., Ivana Vučetić, and Snežana Kirin. 2021. The Serbian primary school teachers’ profiles regarding the preference for a teaching model during the COVID-19 pandemics. Norma 26: 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vučetić, Ivana, Nena A. Vasojević, and Snežana Kirin. 2020. Opinions of high school students in Serbia on the advantages of on-line learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nastava i Vaspitanje 69: 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vučković, Branislava B. 2024. Forms of Coerced Forgetting as a Function of Identity Change in Kosovo and Metohija. Sociološki Pregled 58: 778–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukomanović, Milan. 2001. Sveto i mnoštvo: Izazovi religijskog pluralizma. [The Sacred and the Multitude: The Challenges of Religious Pluralism]. Beograd: Čigoja Štampa. [Google Scholar]

- Vuletić, Vladimir. 2021. Sociological views on the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Serbia. In The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social and Psychological Processes. Edited by Vladimir Vuletić. Beograd: Univerzitet u Beogradu, Filozofski fakultet, pp. 115–26. Available online: https://nauka.f.bg.ac.rs/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Uticaj-pandemije-kovida-19-na-drustvene-i-psiholoske-procese-NBS.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Walker, Brooklin, and Abigail Vegter. 2023. Christ, country, and conspiracies? Christian nationalism, biblical literalism, and belief in conspiracy theories. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 62: 278–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Eileen, Yelena Baras, and Alison Buttenheim. 2015. Everybody Just Want to Do What is Best for Their Children: Understanding How Pro-Vaccine Parents Can Support a Culture of Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine 33: 6703–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, Charlotte, and David Voas. 2011. The emergence of conspirituality. Journal of Contemporary Religion 26: 103–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. 2019a. Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP); Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/329448/9789289054492-eng.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- WHO. 2019b. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Williams, Joshua T.B., Michael P. Fisher, Elisabeth A. Bayliss, Megan A. Morris, and Sean T. O’Leary. 2020. Clergy attitudes toward vaccines and vaccine advocacy: A qualitative study. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 16: 2800–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, Taylor, Benjamin C. Riordan, Damian Scarf, and Paul E. Jose. 2022. Conspiracy beliefs and distrust of science predicts reluctance of vaccine uptake of politically right-wing citizens. Vaccine 40: 1896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, Michael J., and Karen M. Douglas. 2018. Are conspiracy theories a surrogate for God? In Handbook of Conspiracy Theory and Contemporary Religion. Edited by Asbjørn Dyrendal, David George Robertson and Egil Asprem. Leiden: Brill, pp. 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Michale J., Karen M. Douglas, and Robbie M. Sutton. 2012. Dead and alive: Beliefs in conspiracy theories. Social Psychological and Personality Science 3: 767–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Fan, Su Zhao, Bin Yu, Yan-Mei Chen, Wen Wang, Zhi-Gang Song, Yi Hu, Zhao-Wu Tao, Jun-Hua Tian, Yuan-Yuan Pei, and et al. 2020. A new corona virus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 579: 265–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, Ming Jui. 2022. Solidarity in Pandemics, Mandatory Vaccination, and Public Health Ethics. American Journal of Public Health 112: 255–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yendell, Alexander, and David Herbert. 2022. Religion, conspiracy thinking, and the rejection of democracy: Evidence from the UK. Politics and Governance 10: 229–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yezli, Saber, and Anas Khan. 2021. COVID-19 pandemic: It is time to temporarily close places of worship and to suspend religious gatherings. Journal of Travel Medicine 28: taaa065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavod za vrednovanje kvaliteta obrazovanja i vaspitanja (ZUOV). 2013. Pravoslavni kahitizis kao obavezni predmet u osnovnoj i srednjoj školi: Evaluacija programa i kompetencija nastavnika. [Orthodox Catechesis as a Compulsory Subject in Primary and Secondary School: Evaluation of the Curriculum and Teachers’ Competences]. Available online: https://prosveta.gov.rs/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/EVALUACIJA_IZBORNOG_PREDMETA_PRAVOSLAVNI_KATIHIZIS.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Zhou, Peng, Xing-Lou Yang, Xian-Guang Wang, Ben Hu, Lei Zhang, Wei Zhang, Hao-Rui Si, Yan Zhu, Bei Li, Chao-Lin Huang, and et al. 2020. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new corona virus of probable bat origin. Nature 579: 270–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Religion | Number of Believers | Number of Religious Education Teachers | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthodox | 5,387,426 | 1756 | 3068 |

| Muslim | 278,212 | 209 | 1331 |

| Catholic | 257,269 | 157 | 1639 |

| Protestant | 54,678 | 38 | 1438 |

| Total | 5,977,585 | 2160 | 2767 |

| Sex | Department | Year of Study (Mean Age) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| male | female | teacher | educator | first | second | third | fourth | fifth |

| 15 | 336 | 203 | 158 | 82 | 67 | 87 | 74 | 51 |

| Low Religious (Result in Category 0–25%) | Moderately Religious (Result in Category 25–75%) | Highly Religious (Result in Category 25% of the Highest 75–100%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M | 1.00–3.06 | 3.07–4.19 | 4.20–5.00 |

| N | 90 | 176 | 95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrović, J.R.; Šuvaković, U.V.; Nikolić, I.A. Religiosity and University Students’ Attitudes About Vaccination Against COVID-19. Religions 2025, 16, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16010058

Petrović JR, Šuvaković UV, Nikolić IA. Religiosity and University Students’ Attitudes About Vaccination Against COVID-19. Religions. 2025; 16(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16010058

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrović, Jelena R., Uroš V. Šuvaković, and Ivko A. Nikolić. 2025. "Religiosity and University Students’ Attitudes About Vaccination Against COVID-19" Religions 16, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16010058

APA StylePetrović, J. R., Šuvaković, U. V., & Nikolić, I. A. (2025). Religiosity and University Students’ Attitudes About Vaccination Against COVID-19. Religions, 16(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16010058