Abstract

This paper examines the socio-political history of the discrimination suffered by the group called Burakumin (部落民) in the city of Nagasaki in early modern and modern Japan (1600–present). More specifically, it looks into, first, the emergence and evolvement of hostility and antagonism between Burakumin and Catholics in Nagasaki, and second, how discrimination against Burakumin became socially invisible in post-1945 Nagasaki when post-atomic bomb reconstruction transformed the urban landscape of Nagasaki and representations of the city came to be dominated by the Catholic imagery of prayer. The paper argues that, on the one hand, the modern nation-state, established on the principles of the freedom and equality of citizens, did not eradicate discrimination, but instead concealed it, resulting in discrimination continuing in changed forms, and on the other hand, Catholics in Nagasaki, while having themselves suffered political persecution in Japanese history, have been involved in practices of discrimination against the Burakumin. There is, however, not an innate relationship between religion and discrimination, but rather the relationship is historically contingent. Understanding its contingent nature requires us to address the historical conditions contributing to discrimination. By so doing, we can start imagining new ways to tackle and eliminate discrimination.

1. Introduction: Burakumin and Hidden Christians in Nagasaki

Mahara Tetsuo 馬原鉄男 (1930–1992) was a Japanese historian known for his pioneering research into the history of the Burakumin, a social group subjected to persistent discrimination in Japanese history for handling dead animal and human bodies as well as processing animal skins for producing drums and other leather products.1 Buraku refers to the area where the Burakumin lived. In 1960, 15 years after the atomic bombing of Nagasaki City, Mahara visited an area in Nagasaki called Urakami浦上where the Burakumin had congregated for centuries. Urakami was also the epicenter of the atomic bombing in Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. Before his visit to Urakami, Mahara had visited Hiroshima, another city with a sizable Burakumin population that was subject to atomic bombing. In post-war Hiroshima, the population in the area called Fukushima Buraku grew and the area evolved into a Buraku slum. Mahara assumed that Urakami would be similar to Hiroshima. However, it turned out that he was wrong. Most of the Buraku population had died in the atomic bombing in Nagasaki, so no “slum” had formed. According to Mahara,

Urakami Buraku, which should have been located somewhere in the new section [built after the atomic bombing] near the Urakami Cathedral, on the slopes of Mount Konpira which divides the old and new sections of the city of Nagasaki, had almost completely disappeared. [What you can find today] are just a dozen barracks hidden in a vibrant residential area…. I learned for the first time that the majority of the Buraku people have lost their lives in the atomic bombing. The core of the earlier Buraku community, which in Hiroshima had turned into a slum, was wiped out in Nagasaki.(Mahara 1960, p. 63)

As Urakami was near the hypocenter of the bombing, most of the Buraku population lost their lives, with only “a dozen barracks” remaining to scatter among a non-Buraku residential area rebuilt in the post-war period. Mahara then inquired about the Urakami Buraku people with a local Catholic resident near the barracks.

I visited a certain house, asked about a shortcut to the Cathedral, and brought up my usual discussion about the Urakami Buraku people. I was shocked, however, to find that [the Catholic resident came to speak very disparagingly about the Buraku people, and that] I had to listen to so much abusive language which is unnatural for a devout Catholic.(Mahara 1960)

Mahara’s account of his visit to Nagasaki and the conversation with a local Catholic, introduced above, raises two issues for us to consider. The first is that the Urakami Burakumin, who had existed in Nagasaki for centuries, did survive the atomic blast and continued to exist into the post-war period. Secondly, Catholics’ hostility toward the Urakami Burakumin, which originated centuries earlier, had also continued into the post-war years. Both issues at first sight defy comprehension. Did the Japanese state not abolish Buraku discrimination in the early Meiji period (1868–1912)? Why are there still Buraku people identified as such, in small number notwithstanding, decades into the post-war period? Then, why do Catholics in Nagasaki harbor such a vituperative hostility toward the Buraku people, who should supposedly have gained sympathy from the Catholics because Catholics themselves have suffered persistent discrimination historically?

This paper explores these issues by first looking into the history of the antagonistic relationship between Catholics and the Buraku community in Nagasaki in the early modern (1600–1867) and modern periods (1868–), and then examining how discrimination came to be denied by the local government even though discrimination continued in changed forms in post-atomic bomb Nagasaki. The complex intersecting issues of discrimination, religion, and governance in Nagasaki came into public awareness only recently and are largely attributable to the following works: (1) Takayama Fumihiko’s Ikinuke, sono hi no tame ni: Nagasaki no hisabetsu Buraku to kirishitan [Live on, for that day: Nagasaki’s discriminated community and Christians] (Takayama 2017); (2) the NHK ETV special documentary based on Takayama’s book, Genbaku to chinmoku: Nagasaki Urakami no junan [Atomic Bomb and Silence: The Ordeals of Urakami, Nagasaki] (12 August 2017); and (3) Genbaku to yobareta shōnen [The Boy Called Atom Bomb] (Nakamura 2018). The Boy Called Atom Bomb is a testimony to the atom bomb survivor Nakamura Yoshikazu, compiled by Watanabe Kō, the chief director of the NHK special. Engaging the problems exposed by these works, this paper conducts a socio-historical exploration of religion and discrimination in Nagasaki.

This paper is divided into two parts. Part One traces the origin and evolvement of the antagonistic relationship between Catholics and Buraku communities in early modern Nagasaki. Recent studies of Buraku history have elucidated the creation and transformation of status systems contributing to Buraku discrimination (Amos 2020, p. 17). The status system that caused discrimination against the Buraku people in the early modern period needs to be understood in its historical and regional context. This is the case with Nagasaki. Specifically, we need to explore the relationship between the Burakumin and the Catholics in Nagasaki because it can improve our understanding of the origin and the nature of the discrimination in Nagasaki. I examine how hostility between the Buraku people and Christians developed, and how these feelings of suspicion and hatred came to be directed to each other rather than to the political authorities which fostered this antagonism. Understanding discrimination in the early modern period will help us understand why and how discrimination against the Buraku people persisted into the modern period.

Part Two discusses the problem of the social engineering logic of the modern state that contributed to the denial of discrimination. This logic is embedded in the political discursive structure of the nation-state. It refers to the prescriptive principle of the modern nation-state that discrimination must be extinguished, the implementation of which nevertheless ended up concealing discrimination. The discriminated Buraku community has been rendered invisible by the government and society in Nagasaki in the post-atomic bomb period. To explain how this logic has operated to deny discrimination, I first discuss the spatial reorganization of the city of Nagasaki in the process of the city’s post-war recovery that rendered discriminated communities spatially invisible. I then look into the creation of the Catholic image of “prayer” for Nagasaki. The sacred act of prayer has functioned to render invisible the history of discrimination against discriminated communities by Catholics, as well as the existence of Buraku people in present-day Nagasaki. Finally, I examine the Dōwa assimilation movement carried out in post-war Nagasaki and show how the movement achieved a goal opposite to what it set out to achieve in the first place: the concealment of discrimination. The nation-state had to repudiate discrimination for the sake of national integration, but this political mission eventually led to the denial of discrimination rather than its actual eradication. Precisely because the nation-state is supposed to eradicate discrimination, it ended up concealing it.

2. Part One: Burakumin and Christians in Early Modern Nagasaki

2.1. Relocation of the Buraku People, Christian Suppression, and the Emergence of Hostility

Part One traces the history of the relationship between the Buraku people and Christians in early modern Nagasaki in two sections. In the first section, I explain how political hegemons of the time relocated Burakumin in order to more effectively implement the policy of prohibiting Christianity, and how hostility ensued between Burakumin and Christians in the process. In recounting this history, I rely heavily on previous research.2

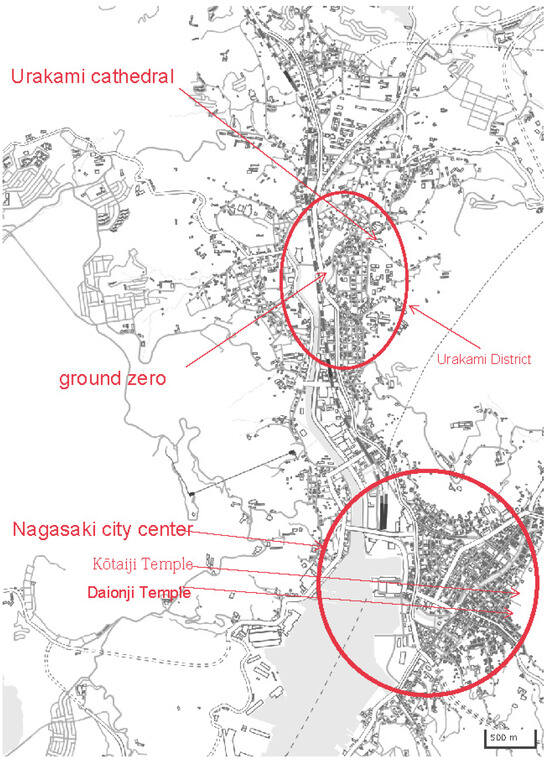

First, let us look at the suppression of Christianity in Nagasaki. Christians from across the country started to congregate around the Todos os Santos Church on the eastern outskirt of Nagasaki after its construction by the Jesuits in 1569. This was a period when more and more Japanese converted to Christianity. But only eight years later, on 24 July 1587 (Tenshō 15) exactly, Toyotomi Hideyoshi issued the Christian-banning Bateren Edict and confiscated Nagasaki and Urakami, two towns previously donated to the Jesuits by Japanese domain lords (Urakami would be incorporated into Nagasaki in the modern period, Figure 1). On 5 February 1597 (Keichō 1), 6 Franciscans, 3 Jesuits, and 17 Japanese Christians were martyred in Nishizaka in Nagasaki. Christians escaping from persecution in Nagasaki were later apprehended in Kyoto and Osaka, and were punished by having their ears sliced off and crucifixion (Fujiwara 1990).

Figure 1.

Map of Nagasaki City (adapted from a map from the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan).

Following the ban in 1587, Toyotomi Hideyoshi confiscated the Jesuits’ land property and rebuilt the town of Nagasaki. In the period up to 1598 (Keichō 3), towns named after professions were created and professional groups were relocated to match this spatial planning. Needless to say, these professional groups were never consulted about their willingness to move or not. Leatherworkers, i.e., Buraku people, were moved out of the inner town to two towns designated as “Kawata-machi 皮田(多)町” and “Kawaya-machi 革屋町” that were close to Daionji Temple of the Jōdo sect and Kōtaiji Temple of the Sōtō Zen Sect. Another Buraku group, the buckskin professionals, moved into the town named “Kegawaya-machi 毛皮屋町”, located in present-day Shinbashi-machi in Nagasaki. Both Kawata 皮田(多) and Kawaya 革屋 were explicit references to the skin-processing profession of the Buraku residents there. The Nagasaki Port Map from the Kan’ei period (1624–1644), housed in the Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture, shows the name “Kawata 皮田(多)-machi”.

In 1605 (Keichō 10), in consolidating the newly established bakufu regime, Tokugawa Ieyasu confiscated Nagasaki’s two outer towns of Shin-machi and Nagasaki-mura from the Ōmura clan and gave the clan, in return, part of Urakami. Directly after this land swap, Ōmura Yoshiaki converted from Christianity to Nichiren Buddhism, most likely to display his political submission to Tokugawa Ieyasu, who like Toyotomi Hideyoshi adopted an anti-Christian policy. Missionaries and Christian converts in the Ōmura domain, not far from Nagasaki, were banished, and it appears that many were persecuted (Fujiwara 1990). From 1612 (Keichō 17), persecution turned harsher in Kyoto and Osaka, and this wave spread to Nagasaki. In 1614 (Keichō 19), ten churches in Nagasaki were destroyed.

Buddhist temples and priests were involved in the persecution of Christians in Nagasaki. In return, Buddhists received the land previously owned by Catholic churches from magistrates and officials. Moreover, former Christian converts were transformed to temple parishioners and were incorporated into the network of Buddhist temples that served as surveillance and registration institutions for the bakufu. At the same time, relocating Buraku communities to the vicinities of Buddhist temples, as mentioned above, suggests that political powers like Toyotomi Hideyoshi may have used Buddhist institutions to monitor and regulate not only former Christians, but also other discriminated groups.

In 1648 (Keian 1), the afore-mentioned Daionji Temple and Kōtaiji Temple expressed their desire to the Nagasaki magistrate Yamazaki Gonpachirō to expand into the neighboring areas, which were inhabited by Burakumin. In response to this desire, the magistrate relocated Buraku communities to Nishizaka in northeastern Nagasaki. Nishizaka being less than one kilometer away from an execution ground, it is possible that the relocation of Buraku communities was part of Tokugawa bakufu’s strategy for the persecution of Christianity. That is, the Buraku people may have been ordered by the bakufu to conduct executions of Christians, so moving them closer to the execution ground facilitated the implementation of this task. In any case, the vacated area became the property of the Daionji and Kōtaiji Temples. The relocation process, however, was not yet over. In 1718 (Kyōhō 3), the Buraku communities were for the final time moved to Urakami, for reasons to be explained below. The area called Urakami 浦上 is the focus of this study.

The place of Urakami is of great spatial significance. It enabled a more effective segregation of former Christians and their policing by the Buraku group in Nagasaki. According to the historian Anan Shigeyuki,

Kawata-machi [i.e., the Buraku communities] was ordered to relocate twice, and ended up being settled between Urakami and Nagasaki. Nagasaki’s population was about 25,000 at the end of the Tokugawa period and Urakami had about 4000. This relocation means 800 Buraku people were now placed along the border so as to keep Nagasaki and Urakami separate. This was very important to the residents of Nagasaki because Urakami had these people who believed in some crazy religion [i.e., Christianity], and the Burakumin transferred from Kawata-machi served as a policing force patrolling the border between Nagasaki and Urakami.(Motoshima et al. 2004, pp. 25–26)

In other words, the Buraku communities, known as “Kawata-machi”, were first relocated to near two Buddhist temples and then moved to a settlement between Nagasaki, the center of the region, and Urakami, a residence area inhabited by a large number of hidden Christians who continued to secretly follow forbidden teaching at the risk of death or exile upon being discovered. On a different note, entering the modern period, Urakami would be incorporated into the city of Nagasaki in 1898 and renamed Urakami-machi in 1913.

So far, I have traced how political powers in early modern Japan suppressed Christianity and how Buraku communities were mobilized to implement anti-Christian policies in Urakami. Buraku people, located at the lower rungs of society, just like the hidden Christians, were mobilized by the political state for apprehending and executing Christians. Here lies the historical origin of Nagasaki Christians’ hostility to Buraku people, a hostility handed down generation after generation into the post-war period. Next, I look at how Burakumin in Kawaya-machi, the afore-mentioned town to the south of Urakami and close to two Buddhist temples, became involved in the persecution of Christians. Some of the people of Kawaya-machi were also Christians.

It appears that, at the beginning, Christians and residents of Kawaya-machi were not hostile to each other. Jesuit priests conducted missionary work in Kawaya-machi from the 1610s, and a certain number of Buraku converted to Christianity. As a result, some people from Kawaya-machi refused to participate in the apprehension or execution of fellow Christians. Records show that in 1618 (Genna 4), 1619 (Genna 5), and 1621 (Genna 7), they refused to be involved in the execution of Christians and missionaries (Fujiwara 1990). A report sent by the Dominican Jacinto Salvanez to the Manila headquarters is telling in this regard. It partially reads,

The second-greatest work that arose among the martyrs at this opportunity happened at a cuvaya (“kawaya”, leather workshop), whose workers had the occupation of skinning beasts. These people also guard the jail and bind those who are to be put to death and take them there [to the execution ground]. As when 12 holy martyrs were burned two years ago, this time as well, these people knew that it was a sin, so they resisted going out to do their jobs as executioners. …

Because these are the most scorned, poor people in Japan, the martyrs Friar Hernando San José and Friar Alonso Navarrete both gave alms to them, held mass, administered the sacraments, and aided them, and for this reason, they built a small chapel.3

Here, Salvanez describes the Buraku people as “the most scorned, poor people in Japan” who “sabotaged the work of assisting in prison affairs concerning Christians”. He also noted that they were baptized. It is clear that the relationship between Christians and the discriminated Buraku people was not antagonistic at the beginning of the early modern period.

It is also worth noting that, contrary to Salvanez’s observation that the Burakumin were “the most scorned, poor people in Japan,” some sources point to the possibility that leather workers were actually respected. Chronicle of the Kingdom of Japan, written by the Spanish trader Avila Hiron who came to Japan at the end of the 16th century and stayed in Nagasaki, describes Japanese leather workers of the time as “those who make footwear and sandals on the worst outskirts of town, who are regarded as lower than the fishermen. However, the deer-skin tanners lived with them. Moreover, the craftsmen who make tabi (socks), gloves, and hakama from deer or sealskin are held in high esteem” (Hiron 1965, p. 80). If, as Avila Hiron saw it, the tanners were a respected social group, it is possible that, at least as late as the 16th century, the social contempt for the tanners was not completely fixated. If so, we can speculate that the Christians’ disdain, if any, for the Buraku people would not have been completely fixed either.

The relationship, however, turned antagonistic in the Kyōhō era (1716–1736). The establishment of the official outcast (hinin) system may have contributed to the change (hinin refers to the Buraku people). Records show that, during this period, the “Kawaya-machi outcast overseer” in Nagasaki was in charge of apprehending criminals. The overseer or superintendent was an outcast, i.e., Burakumin. Then, court records (hankachō) show that judgments of hinin temoto (“exile to an outcast area”), specifically to Urakami, increased over time, indicating more exiles were sent here, which may have led to an increase in the population of Urakami. These exiled people were unable to settle down and wandered around as vagabonds. Some of them committed crimes. In response, the magistrate gave each resident in the outcast Buraku area three straw bags of rice a year to make this floating population settle down into a communal life. The historian Anan Shigeyuki conducted research on the crime record books of the Office of Nagasaki Magistrate and found out that residents of the outcast area came to be affiliated with police institutions of the magistrate. They performed city patrols, arrested criminals, and served as jailers. Together with these policing roles, the Buraku people of Kawaya-machi also participated in supervising and apprehending Christians.4 As Buraku people assumed the policing role that in many cases targeted Christians, it is not difficult to imagine how their relationship began to turn antagonistic.

2.2. Aggravation of Hostility during the Fourth Discovery in Urakami in 1867–1968

With the historical ground laid for the relationship between Christians and the Buraku people to deteriorate, a tragic event at the end of the Tokugawa period solidified lasting antagonism. It is the so-called Urakami Yoban Kuzure, or the “4th discovery in Urakami” in 1867–1868. “Kuzure” refers to the discovery of the hidden Christians, and “yoban” literally means “no. 4”, referring to this being the fourth discovery. The first discovery of hidden Christians in Urakami was in 1790, the second in 1842, the third in 1856, and the four between 1867 and 1868, just when the Tokugawa regime was coming to an end and the new Meiji state was being created. Hidden Christians from Urakami were apprehended in June 1867. They were tortured and in the following year exiled to different parts of the country.

The Buraku people in Kawaya-machi undertook the apprehension and jailing of these hidden Christians under the orders of the Nagasaki magistrate. It is not clear whether some Buraku people, being Christians themselves, refused to perform the duties, as they did in the early seventeenth century. The memoir of Sen’emon Takagi, a Christian in Urakami, describes how the Buraku people of Kawaya-machi performed their work in the jail where he was kept (Takaki 2013, p. 183). According to Takagi, the captured Christians were temporarily housed in the residence of Urakami officials, and serious violence broke out between Urakami Buraku wardens and imprisoned Christians. Reports submitted by the imprisoned Christians to account for the incident emphasized that they were subjected to maltreatment by “a large number of eta-hinin (outcasts)” (Urakawa 1943, p. 150). The terms eta and hinin are widely used derogatory terms to refer to Buraku people during the early modern period. These words are not used today. The Christians found it difficult in their reports to blame the magistrate office for their apprehension, so they disparaged their captors and called these Buraku people eta and hinin, or “defiled” and “inhuman” (Urakawa 1943, p. 150).

These letters show that the hostility between the two groups, having been in fermentation for a long time, had reached a climax during the political crisis confronting the Tokugawa bakufu state in 1867–1868. In this volatile political context, both the hidden Christians and the Buraku people tried to curry favor with political authority (the Nagasaki magistrate) by negating and denigrating each other (Motoshima et al. 2004). On his part, the Nagasaki magistrate mobilized the fear and aversion of the two groups toward each other to maintain governance. The magistrate undertook this by hiring Buraku people as police, persecutors, and executioners. Magnifying the legal and social differences between the two groups, the magistrate reshaped the oppressed groups’ fear of and aversion to political authority to an animosity for each other. The magistrate further used Buddhist temples to pressure Christians to convert to Buddhism. After some initial resistance, most former Christians eventually converted. On their part, Buddhist temples were successful in obtaining more parishioners.

3. Part Two: Transmogrification and Concealment of Discrimination in the Modern Period

3.1. Modern Forms of Discrimination in the Meiji Era

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 ended the rule of the Tokugawa bakufu and brought into existence the new, modern state. The Meiji government continued the Tokugawa bakufu’s prohibition of Christianity, which it saw as an ideological threat. The new Nagasaki local government, after some deliberation, decided to exile entire villages of hidden Christians uncovered in the fourth discovery. This meant banishing 3394 Christians to western Japan. The exile continued for about six years till 1873, when prohibitions against Christianity were stopped due to Western protests. During this period, more than 600 Christians died and 900 were forced to convert (Iechika 1998; Anan 2009b). The Buraku people’s participation in persecution in the fourth discovery reinforced Urakami Christians’ discrimination against them.

In 1871, the Meiji government promulgated the Emancipation Order (kaihōrei), abolishing discrimination against the Buraku people. The socio-cultural bases justifying discrimination, such as place names like “Kawaya-machi” that revealed the profession and identity of residents, were abolished. In addition, freedom of movement and choice of profession and marriage were also legally stipulated. Nevertheless, this did not mean that prejudices and discrimination against the Buraku groups immediately went away. The Emancipation Order was unable to eradicate discriminatory attitudes that had existed for centuries. Moreover, modern knowledge such as racial theories that were allegedly based on science was introduced to explain and justify discrimination against the Buraku people (Kurokawa 2023).

Continued discrimination gave rise to a Buraku Improvement Movement (Buraku kaizen undō) in the 1880s. While this started out as a voluntary movement by Buraku people themselves, local governments gradually played an increasingly important role in managing it (Buraku Kakihō Kenkyujo 2001). The movement evolved into a public–private joint effort to improve the physical and mental conditions of the Buraku people and eventually overcome discrimination. It was meant for the Buraku people to make efforts to improve living conditions such as cleanliness, receive education, and reform social customs, behavior, and manner so as to construct a life base and become independent. In Urakami-machi in Nagasaki, thirty-four young people formed a youth organization, which became the center of cultural exchange with other Buraku communities as well as a center for vocational education in 1895–1896. Other Buraku improvement development included the construction of the Shinshū Youth Hall as a community facility (Nagasaki Institute for Human Rights Studies (NPO) n.d.).

However, the improvement movement operated on the assumption that the cause of discrimination lied in the Buraku people themselves, rather than in the society. There was a deep-rooted thinking that the Burakumin were the ones who should change, not society (Kurokawa 2023). No one went on to identify problems in the consciousness of the discriminating social majority as being in need of change or improvement. When Buraku people themselves realized this problematic lack of self-consciousness on the part of society, they created in 1922 the Marxist-inspired National Levelers Association (Zenkoku Suiheisha). The Nagasaki Prefecture Levelers Association was formed in the Shinshū Youth Hall in 1928. As such, the formation of the Suiheisha was not an attempt by the government to improve the Burakumin’s situation, but resulted from the awakening of the Buraku people to the problematic nature of the society that considered them deserving of discrimination.

Suiheisha then represented an initiative on the part of the Burakumin themselves in fighting against discrimination. They presented themselves as Burakumin and aspired to transform discrimination into pride. The national Suiheisha Declaration states: “The time has come for us to be proud of being Burakumin”. It is not we Burakumin who should change but rather it is the society that should change. From Suiheisha originated the Buraku Movement in modern Japan (Kurokawa 2023). But an internal division into the right and the left ensued and seriously compromised the association’s goal to eradicate discrimination.

Discriminatory views against the Buraku people were reinforced by former hidden Christians’ descendants. The hostility was passed down in both oral and textual transmission. The influential Christian writer and historian Urakawa Kazaburo (1876–1955) exemplifies the process of transmission of that hostility and antagonism. Urakawa was born in Nagasaki and worked as a priest and bishop there. He was also known as a scholar of Christian history. Urakawa’s mother was exiled to Kagoshima during the fourth discovery in 1867. In his works such as The History of Urakami Christians (Urakami kirishitan shi), published by Zenkoku Shobō in 1943, Urakawa had much to say about the nature of the violence between the Burakumin and Christians during the fourth discovery from the Christian perspective. His work contains valuable materials, but it also contains prejudice and discrimination against the Burakumin. The following statement is an example,

The Cathedral was smashed. The relics were looted. The vestments were put on their heads by ignorant Burakumin as rain gear and they went home with pride.(Urakawa 1943, p. 145)

Urakawa’s portrayal of the Buraku people was meant to create a rhetorical effect that served the author’s goal of constructing a narrative of the Christian ideal by foregrounding suffering. The historical narrative of ideals and suffering helped generate legitimacy for Christianity in Japan. In doing so, however, Urakawa ended up confirming and spreading bias and discrimination against the Buraku people. It must be understood that the church’s need for legitimacy unfortunately not only condoned, but reproduced bias and discrimination that went beyond Urakawa’s original intention.

Then, was the discrimination held by Urakami Christians toward the Burakumin stronger than that held by non-Christian Japanese? I have no evidence proving this to be the case. Mabara’s recollections introduced at the beginning of this paper do show that post-war Christians harbored intense hostility toward the Buraku people, but this was an isolated example. It is, however, safe to say that prejudice and discrimination against the Buraku people were reproduced within Christian communities.

As we have seen so far, Buraku people continued to suffer discrimination in the modern period, even though discrimination had been legally abolished. Traditional views against Buraku people retained their power in Meiji Japan. Christians who were persecuted by Buraku people in the early modern period maintained their hostility and negative views and transmitted these views to their children. The continued discrimination against Buraku people in the pre-1945 period can also be partially explained by the fact that despite the Japanese nation-state being a monarchical constitutional state in which individual Japanese people were provided rights and liberties, these West-originating values were not really assimilated into Japanese society, helping the sustainment of the discrimination against the Burakumin. Pre-modern traditional ideas and ways of thinking were still influential. In particular, Christians’ sense of animosity toward the Burakumin played a significant role in elongating discrimination against them.

Does this then mean that in the post-1945 period Buraku discrimination disappeared? Unfortunately, the answer is no. It did not disappear, but rather came to be concealed. How did discrimination become hidden?

3.2. Concealment of Discrimination in Post-Atomic Bomb Nagasaki: Land Right, Urban Planning, and the Imagery of Prayer

The atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. A few days later, Japan announced its surrender, bringing an end to the war. After the war ended, the atomic bombing came to be recognized and remembered as a tragic event of unprecedented historical significance. Christians in Nagasaki contributed majorly to shaping the memory of the atomic bombing as the city came together and the whole country embarked on reconstruction as a demilitarized, democratic nation. In this context, the discriminated Buraku people in immediate post-war Nagasaki came to be overshadowed by the Christian imagery of Nagasaki as a site of divine punishment and prayer. The Buraku people eventually ended up being concealed in the process of the post-war reconstruction of Nagasaki.

Here, let us return to Mahara’s recollection of his visit to Nagasaki in 1960. He had confirmed for us that the Urakami Burakumin, who had existed in Nagasaki for centuries, did survive the atomic blast and continued to exist into the post-war period. According to Genbaku hisai fukugen chōsa jigyō hōkokusho (Survey Report on Atomic Bombing Damage Restoration) (Nagasaki City 1975), 243 families in 229 houses in Urakami-machi, i.e., the town of Buraku people, were completely incinerated by the atomic bomb. Of the total 909 residents there, excluding people who had been away for military service, etc., 155 people died immediately, 141 died before the end of the year, 293 were of unknown fate, 159 were seriously ill, and 129 suffered minor injuries. In other words, 261 may have survived if all former local soldiers returned to Nagasaki. While the extensive damage is obvious, the Buraku group did by no means go extinct. Nevertheless, in the immediate post-atomic bomb years, there was no public representation or discussion of Buraku people in Nagasaki. It seemed they had disappeared entirely from the consciousness of society. What caused the so-called “Urakami tribe” to lose their social existence in Nagasaki many years after the atomic bombing? What are the social and historical forces that rendered them invisible? To understand this loss of social existence, I will explore three contributing factors: first, changes in land rights; second, urban planning for recovery; and third, the Christian imagery of prayer.

The first factor is land rights. During the Shōwa depression of 1930–1931, which plunged the Japanese economy into a crisis, some Buraku people in Urakami-machi had to sell their land to landowners outside the town. All that was left to them was their house. When they lost this during the atomic bombing, they lost everything and were forced to leave the town (Isomoto 1998, p. 69). According to Anan Shigeyuki, only 21 households remained; 88 households were reported to have moved elsewhere within the city of Nagasaki, 18 elsewhere within the prefecture of Nagasaki, 18 to Fukuoka prefecture, and 49 to Osaka (Anan 1995, p. 30). Land right losses resulting from the economic crisis contributed to the decrease in the Buraku population in Urakami.

In addition to land right loss, the post-bomb urban reconstruction of Nagasaki occurred, which involved a change of town name. In September 1946, Nagasaki City decided to implement a land readjustment project for post-war reconstruction, mainly in the Urakami area (Nagasaki City History Compilation Committee 2013, p. 64). As part of the urban redevelopment under the Nagasaki International Cultural City Construction Act of 1949, roads were built that passed through the Urakami Buraku town. The new roads changed the landscape of the town, making it difficult to see the Urakami Buraku community spatially. Moreover, the town’s name was changed from Urakami-machi to Midori-machi. With this change of name and the spatial transformation of the town, it became almost impossible to find Urakami Burakumin.

Together with these changes came the formation of the imagery of prayer. Largely thanks to the Catholic medical doctor Nagai Takashi 永井隆 (1908–1951), who wrote influentially about the atomic bombing, war, and peace in Nagasaki during the U.S. occupation of Japan (1946–1952), the name “Urakami” became strongly associated with Catholicism rather than the Buraku people.5 This association was through the imagery of “the Nagasaki of prayer”. Nagai, an expert in radiation medicine, was a victim of the atomic bomb and was severely injured. Losing his wife in the bombing, Nagai devoted himself to helping atomic bomb survivors. A good writer, Nagai published the memoirs Kono ko o nokoshite (Leaving My Beloved Children Behind) (1948) and Nagasaki no kane (The Bells of Nagasaki) (1949). Leaving My Beloved Children Behind was the best seller of 1949 and The Bells of Nagasaki ranked number four. The latter work was made into a movie. In July 1949, the record song “The Bells of Nagasaki,” composed by Yuji Koseki, one of Japan’s leading composers of the time, and sung by singer Ichiro Fujiyama, was released and became a national hit. The film The Bells of Nagasaki earned JPY 5.092 million in distribution, ranking seventh among all films of the year (Fukuma 2011, p. 253).

A devout Catholic, Nagai developed a significant interpretation of the atomic bombing. He asserted in his works that the dropping of the atomic bomb was a “divine providence” and the dead in the bombing were “offerings to God” and “sacred sacrifices for peace”. Nagai read the following eulogy at a memorial ceremony held in front of the ruins of the Urakami Cathedral (Tenshudo) on 23 November 1945.

At midnight on 9 August, Urakami Tenshudo went ablaze, and at this very same time, the Emperor decided to end the war. On 15 August, the great Imperial Rescript on the end of war was issued and peace was ushered in. This day was also the day of the great feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin. Is this strange overlapping of events a mere coincidence? Or is it the Providence of the Heavenly Father?(Fukuma 2011, pp. 250–51)

Then, in The Bells of Nagasaki, Nagai writes the following: “The moment Urakami started being slaughtered, God accepted the slaughter, heard the apologies of mankind, and immediately sent a decree to the Emperor to end the war” (Nagai 1949, pp. 178–79). Nagai continues, “the Urakami Church, which suffered from 400 years of persecution but sustained its faith covered with the blood of martyrdom, and never ceased to pray morning and evening for eternal peace during the war, is the only innocent sacrificial sheep that can be offered to God” (Nagai 1949, pp. 178–79).

These comments may seem quite extreme, but in his time, Nagai was not criticized but praised as a person of character. Rather than resenting the drop of the atomic bomb, he reflected on Japan’s own barbarous acts in the war and cherished the fact that Japan had become a peaceful nation. He urged people to pray for a world without atomic bombs and for eternal peace. Here, “prayer” emerged to become a keyword in the engagement with the past and the envisioning of the future. People looked at Nagai and his views as virtuous. The reason why many people in Japan, not just Catholics in Urakami, sought out Nagai’s words was probably due to the historical transition, resulting from the war defeat, from an emperor-based state to a Western-style democratic society. For Catholics in Urakami in particular, the collapse of the imperial state completely removed the barrier to their religious freedom. For non-Catholics as well, Nagai represented the prominent social presence of Western religion in Japan. They looked at this presence as a welcoming sign of “freedom through democracy” (a phrase used at that time) in post-war Japan. For these reasons, Nagai’s words and the image of prayer gained influence. The imagery of prayer created the illusion of equality for the people of Japan, including the Urakami Burakumin. The imagery of prayer also generated an image of peace, which made people forget about the discrimination against the Burakumin.

Because The Bells of Nagasaki graphically depicted Nagasaki directly after it was bombed, its publication was initially banned by the GHQ/SCAP, but they later permitted its publication on the condition that the work be accompanied by a work titled Manira no higeki (The tragedy of Manila), which recorded the Japanese army’s atrocious acts in wartime Philippines. By so doing, the SCAP wanted readers to understand that although the atomic bombing was an awful event, as portrayed in The Bells of Nagasaki, it was intended to end the atrocity and violence committed by Japanese military soldiers outside of Japan as soon as possible.

The historic association of the city of Nagasaki with Christianity helped solidify the imagery of prayer. The Urakami district of Nagasaki, which suffered significant damage, being the ground zero site of the atomic bombing, was where Christians had congregated since the beginning of the early modern period. The Urakami Cathedral, destroyed in the bombing, became a famous symbol of destruction, suffering, and hope through prayer for peace. With Urakami’s historical geography and Nagai’s impactful writings, the imagery of the Nagasaki of Prayer was consolidated during the period of U.S. occupation.

Once the geographical space of Urakami was recognized by society as being associated with the Christian imagery of prayer, contestations and contradictions inside the space of Urakami, such as those between the Buraku people and Christians, came to be reduced to the background and became invisible. When they did appear, they tended to be seen as merely individual problems. The imagery of prayer functioned to magnify the expectation that all the misfortune and injustice “here and now” will be resolved somewhere in the future, further reducing the desire to raise social issues and problems, particularly in relation to the Buraku community. In the case of Nagasaki, the persecution of Christians and the atomic bomb were categorized as “misfortune and injustice”, and came to be recognized by society as an impetus for continuing to pray. The issue of Buraku discrimination lost its social significance and fell through the cracks of social consciousness.

In other words, the disappearance of the Urakami Buraku from public view in the process of immediate post-war recovery was not due solely to the shrinking of resident population; spatial transformation, place renaming, and the resignification of prayer for the city all contributed to its exile from public consciousness. Nevertheless, when it did come back into social consciousness and became a political issue, the Buraku community continued to be a target for bias and discrimination. Eventually, their very existence not only disappeared from public consciousness, but also was exiled from political governance. How did this happen in post-war Japan, where the economy was growing with high speed, social welfare was being enhanced, and a society of affluence and equity was coming into being? In the final section, I look at the assimilation policies of the Japanese government to examine the inner logic of the modern nation-state that ended up hiding the Buraku discrimination problem rather than solving it, betraying the very intension that gave rise to the assimilation policies.

3.3. “Assimilation” (Dōwa) Policy and the Refusal to Recognize Discrimination

In the prewar and post-war years, the Nagasaki prefectural chapter of the non-governmental Buraku Liberation League (Buraku kaihō dōmei) conducted regular surveys of households and the population of discriminated Buraku communities. According to the survey results, the population decreased over time, and by 1972 the number had become zero (Isomoto 1998, p. 58; Takayama 2017, p. 114). Back in 1930, the survey showed that there were 547 houses and 2594 people in the Nagasaki prefecture (including Nagasaki City). In 1964, the number had decreased to 80 houses and 349 people. Then, in 1972, there were no more Burakumin in Nagasaki. The committee chair at the time, Isomoto Tsunenobu, reported this survey result to the prime minister’s Cabinet Office. A significant fact, however, hid behind the chair’s report of zero population: Isomoto knew himself there actually were 928 Buraku households in the prefecture (Isomoto 1998, p. 58; Takayama 2017, p. 114).

The Cabinet Office asked the Nagasaki prefecture to conduct the survey again. In responding to the request, the Nagasaki prefectural government wrote that it was aware of the existence of discriminated communities in Nagasaki, but inquired if it could report on that item as “not applicable”. It explained that “we understand [the problem of Buraku communities] and are actively working to improve social welfare for residents in these communities. It is, however, inappropriate for the prefecture to raise the issue of these communities as Dōwa districts as it will hurt the feelings of the citizens of our prefecture”. As is often the case with the writing style of Japanese administrative documents when it comes to issues considered sensitive, such as discrimination, the Nagasaki prefecture’s response was vague in its logic and weak in its reasoning. Nevertheless, the Nagasaki prefecture did manage to report that discriminated Buraku communities no longer existed.

This blatant ignoring of the actual situation on the ground seems outrageous, but it actually manifests an inner logic of social engineering in the Japanese state for achieving political governance. Let us explore this logic by examining the Japanese government’s policy of Dōwa 同和, or “assimilation” or “social integration”. The Dōwa policy, in providing support to the Buraku, took the form of designating Dōwa districts and providing support to the people living in these areas. The goal of course was to eventually eradicate discrimination and realize a society of equality. Certainly, the lives of Buraku people in districts designated as Dōwa would improve. However, the designation of Dōwa districts simply generated a spatial marker for these areas, regardless of the life conditions of the people living there. These areas remained geographically identified as Buraku areas, now accentuated by the new name of Dōwa, and people’s perception of the areas as Buraku districts did not easily go away.

However, for the government, the nominal linguistic distinction between a Burakumin area and a Dōwa district was significant. They could now say what existed was a Dōwa district, which brought up an image of an administrative unit working on eradicating discrimination; since discrimination was being eradicated there, it was not appropriate to call it a Buraku, or a Burakumin, district. The political relationship between reality and representation (language) reveals the limits of the Dōwa policy. The policy was meant to erase discrimination, but it ended up concealing the existence of the Burakumin.

There may be another reason for the Nagasaki prefecture to have reported a Buraku population of zerio. It is likely that Nagasaki City felt hesitant in using taxpayers’ money in Dōwa assimilation projects. Dōwa assimilation projects involve building apartments, libraries, community centers, and other facilities for discriminated Buraku communities. Because these projects were outsourced to the Buraku Liberation League, which allegedly had connections with gangster groups, paying the league would mean a possible flow of funds to gangster groups, which could put the funds to illegal use. To prevent this from happening, the Nagasaki government chose to report that no Burakumin were left in the city. But to what extent was the Buraku Liberation League linked to gangster groups? If they were indeed linked, should it be considered a reason for the Nagasaki City government to deny the existence of Burakumin?

J. Mark Ramseyer and Eric B. Rasmusen conducted research on the connection between Burakumin and gangster groups (Ramseyer and Rasmusen 2018). They argue that the massive subsidies provided by the 1969 Dōwa assimilation projects attracted not just Burakumin, but also many gangster groups, resulting in Burakumin joining gangster groups. Based on several testimonies, they estimate that “half to 70%” of the gangster members were Burakumin. Consequently, Ramseyer and Rasmusen conclude, Japanese society has essentially come to identify Burakumin with gangster groups.

There is no denial of the fact that some Burakumin joined gangster groups. Kunihiko Konishi, who served as the Osaka branch chief of the Buraku Liberation League from 1969 for about 40 years, was a gangster member (Kadooka 2012). Japanese scholars have also shown connections between Burakumin and gangster groups in Kyoto (Yamamoto 2012). Their research, however, draws conclusions opposite to that of Ramseyer and Rasmusen. They disagree with the latter’s estimate that up to 70% of gangsters were Burakumin and believe this number is seriously exaggerated. What is more important, however, is the fact of Burakumin joining gangster groups is a result of persistent discrimination against Burakumin in the post-war period. Joining gangster groups was not the cause for the discrimination against them, as suggested by Ramseyer and Rasmusen. It was the deep-rooted discrimination in Japanese society that led to the reduction in resources and life chances for Burakumin, who in turn were pushed to join gangster groups as one of the few life options available to them. In this sense, Burakumin gangsters, even if large in number, cannot be used to explain the Nagasaki City government’s zero-number report. The act of the Nagasaki City government was motivated by contradictory administrative logic, rather than by the fact that Burakumin and gangster groups were linked, the link itself being the result of unending discrimination.

Now, let us conduct a historical survey of official engagement with the eradication of Burakumin discrimination. The Japanese government started to tackle the Buraku discrimination problem in 1961. In that year, it launched the Council for Dōwa Measures (Dōwa taisaku shingikai) under the leadership of the prime minister. The council conducted nationwide surveys and held discussion meetings before submitting a report to then-prime minister Satō Eisaku on 11 August 1965. The report found that “to resolve the Dōwa problem, it is central to completely guarantee residents of Dōwa districts equality in employment and education opportunity and transfer the surplus population in Dōwa districts to industrial production centers so as to improve the stability and status of their lifestyles” (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology 2012). In response to this report, the Act on Special Measures for Dōwa Projects was enacted in July 1969. It was, however, a temporary legislation, effective only for ten years. Yet, the Act created the context for the Cabinet Office to inquire about the Buraku population in Nagasaki’s Dōwa district in 1972, as introduced above. It was part of the government’s effort to gain an understanding of the current state of discriminated communities throughout the country. However, it brought about the obviously incorrect survey result from the Nagasaki prefecture.

The survey result in Nagasaki is a regrettable example of the phenomenon by which the government’s attempts to achieve social equality and inclusion contrarily led to social exclusion. The explanation provided by Nagasaki, that it was inappropriate for the prefecture to raise the issue of these communities as Dōwa districts as it would hurt the feelings of the citizens of the prefecture, is not convincing and does not make sense. It is, however, necessary to realize that Nagasaki prefecture’s response was hardly a problem at the time. Why? There were multiple contributing factors. First, in terms of administrative cost, if the discriminated Buraku did not exist, there would be no need to guarantee equal opportunities in employment and education, resulting in a reduction in administrative labor and costs, as well as the human and financial resources that would be allotted to develop support programs for the Dōwa district. Second, from the perspective of Nagasaki residents, the existence of the Buraku was not only a disgrace, but also a costly one, because their taxes needed to be spent on supporting the Buraku people, something they loathed. Third, for the Buraku people, being designated as a Dōwa district meant revealing their identity, and exposing their identity would incur the discrimination they feared. For these reasons, it was in Nagasaki prefecture’s best interest to officially declare that there were no more Burakumin in the prefecture.

In reference to the Dōwa policy, the phrase “don’t wake a sleeping baby” (neta ko ha okosuna) is sometimes used. This phrase is indicative of the governance logic that led to the concealment of discrimination. The phrase means if something is not problematized as an issue, then just let it be. The Nagasaki prefecture report is a typical example of “don’t wake a sleeping baby”. The “sleeping baby” here refers to the Buraku issue, which appeared to have calmed down because of social forgetfulness. This depicts the mentality of the prefecture, which chose not to see problems where things did not appear problematic. The logic of “don’t wake a sleeping baby” was to keep Buraku discrimination from becoming socially apparent. People there know that the Buraku exist, but they pretend not to know. They act as if they do not exist, even though they do. As a result, discrimination became not only invisible, but more entrenched. This is superficially compatible with the ideology of the nation-state, which aims to realize the complete equality of the whole population.

By pretending not to see discrimination against the Buraku people, the prefecture was then able to declare that the Buraku people did not exist, so there was no discrimination. Both the government and citizens of Nagasaki were thereby able to maintain the public façade of a modern, egalitarian society. This pretension in political governance exposes the social engineering logic of the modern state: it is compelled by the imperative to abolish discrimination because discrimination should not and must not exist. On the other hand, discrimination is by no means easy to eradicate. A conflict between “should be” and “be” emerged, constantly delegitimizing modern political governance in Nagasaki and Japan. The expedient option was then to make it disappear. As a result, Dōwa policies became the pitfall that not only concealed, but also preserved present and past discriminations against Buraku people.

The tendency to refuse to recognize Buraku discrimination, as evident in official stances and statements, was shared by religious groups, including Buddhism. One possible reason for this is their desire to deny the existence of Buraku discrimination. Why do Buddhists want to deny it? Because they themselves have discriminated against the Burakumin. One example is the issue of kaimyo 戒名, or “posthumous Buddhist name”, a name given to a person upon their death by a Buddhist priest. Names given to Burakumin during the early modern period and up to 1945 are known as “discrimination names” (sabetsu kaimyo), because discriminatory terms such as “cattle (畜)”, “slavery (隷)”, and “defilement (穢)” were used in these names. Buddhists wanted to believe that by claiming that the discriminated Burakumin no longer existed, they could avoid reflecting upon history and did not have to be held accountable for their past wrong-doings (Motofumi 2021, pp. 78–81).At the Third Assembly of the World Conference of Religions for Peace, held in Princeton, in 1979, the board chairperson of the Japan Buddhist Federation stated that there was no more Buraku discrimination in Japan. That was an old tale from about 100 years ago, and it no longer happens now.

The chairperson’s efforts sent a shockwave back to Japan. People began to realize the problem of discrimination by religious organizations. More and more people, in and beyond religious circles, started to make efforts to engage with the Buraku discrimination issue in order to arouse social awareness and eliminate discrimination. In Nagasaki, the Nagasaki Council of Solidarity Between Religions and Religious Groups to Engage with Buraku Liberation was formed. This Council of Solidarity consists of 11 religious groups, including the Honganji division of the Jōdo Shinshū sect, the divisions of the Shingon sect, the Ōtani division of the Shinshū sect, other divisions of the Shinshū sect, the Sōtō sect, the Tendai sect, the Catholic church, and the United Church of Christ in Japan. Later, in June 1981, a national organization, the Council of Solidarity Between Religions and Religious Groups to Engage with the “Dōwa Issue”, was formed and remains in existence today. It is commonsense among religious groups in Japan that Burakumin discrimination is a problem in need of resolution. Deeply reflecting upon their past history of discrimination, religious organizations and people have been making persistent efforts to eliminate Burakumin discrimination.

4. Conclusions

This paper examined the complex history of the discrimination suffered by the group called Burakumin in Nagasaki in the context of early modern political changes, the religious policy of the state, modern nation-state building, and urban reconstruction and historical memory in post-atomic bomb Nagasaki. The first part of the paper examined the emergence of hostility between Burakumin and Catholics in early modern Nagasaki. Burakumin in the early modern period helped the state in prohibiting Catholicism, incurring the latter’s hostility and hatred. This hostility reached a climax during the fourth discovery of hidden Christians in 1867–1868. The second part explored how Burakumin, despite being legally emancipated from discrimination in the early Meiji period, continued to suffer unequal treatment, and how, to make things worse, Burakumin were rendered socially invisible in the midst of post-1945 Nagasaki urban reconstruction and social development. To explore the problem of concealment, I looked into three factors within the post-war political framework of the nation-state that was compelled to prohibit and eradicate discrimination: first, the urban reconstruction of post-war Nagasaki; second, the emergence of the Catholic imagery of prayer as the dominant representation of Nagasaki; and third, the local government of Nagasaki’s assimilation (Dōwa) policy to eradicate Burakumin discrimination. While aiming for the goal of the eradication of discrimination, the Dōwa policy ended up concealing the very existence of Burakumin in Nagasaki, thereby resulting in invisible discrimination against this social group.

Based on the above historical investigation, the paper developed two arguments. First, the modern nation-state, established on the principles of the freedom and equality of citizens, did not eradicate discrimination, but rather concealed it so that discrimination continued in changed forms. Second, Catholicism, despite itself suffering political persecution in Japanese history, is intertwined with Burakumin discrimination. There is, however, not an innate relationship between religion and discrimination, but rather the relationship is always historically contingent. It is necessary to disentangle the complex historical relations that have resulted in Burakumin discrimination, as well as the multifaceted historical experience of Catholicism in Japan. It is only after understanding the contingent nature of the formation of discrimination that we can start to imagine new ways to put an end to it.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The word Buraku in Japanese has two meanings: first, an area of private residences and homes; and second, an abbreviation of the term “discriminated community” (Hisabetu-Buraku 被差別部落, or Buraku outcasts). It is the second meaning that is used in this paper. Buraku refers to an area inhabited by people who, in the feudal era, engaged in the production of leather goods and in securing communal safety under the order of political authority. People living there were called eta or hinin, and were subjected to severe restrictions and discrimination in all aspects of their lives, including residence, work, marriage, and socialization. Urakami is an area in the northern part of Nagasaki City, known for the Urakami Cathedral located there. Urakami was also the site of the atomic bombing on 9 August 1945. Therefore, the word Urakami evokes images of both Catholicism and the atomic bombing. |

| 2 | Previous studies to which this paper has referred include Masuda and Fujiwara’s work (Masuda 1981; Fujiwara 1990). In addition, the series of studies by Shigeyuki Anan, secretary general of the Nagasaki Human Rights Institute, is of particular importance to the current research (Anan 2004, 2009a, 2009b). I would like to thank Mr. Anan Shigeyuki for providing valuable information regarding Burakumin in Nagasaki via interview and emails. |

| 3 | Cited in Anan (2004). Anan’s description is based on Garcia (1976). Anan notes that several cases where people from Kawaya-machi refused their duties can be confirmed between 1618 and 1622. |

| 4 | Anan (2004) points out that the Burakumin routinely worked for the police force. |

| 5 | There is much research on Nagai Takashi, but the current study relied on Nishimura (2002), Fukuma (2006) and Shijyou (2012). |

References

- Amos, Timothy D. 2020. Caste In Early Modern Japan: Danzaemon and the Edo Outcaste Order. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Anan, Shigeyuki. 1995. Nagasaki genbaku to hisabetsu Buraku [The Nagasaki atomic bomb and discriminated communities]. In Furusato wa isshun ni kieta: Nagasaki, Urakami-machi no hibaku to ima [Our Hometown Disappeared in an Instant: The Atom Bombing of Urakami-Machi, Nagasaki and Today]. Edited by Nagasaki Prefecture Buraku History Institute. Osaka: Kakihō shuppan, p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Anan, Shigeyuki. 2004. Kirishitan hakugai to hisabetsu Buraku [Christian Persecution and Discriminated Communities]. Osaka: Kakihō shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Anan, Shigeyuki. 2009a. Nagasaki no hisabetsu Buraku (The discriminated community of Nagasaki). In Nagasaki kara heiwagaku suru! [Study Peace from Nagasaki!]. Edited by Takahashi Shinji and Funakoe Kōichi. Kyoto: Horitsu Bunka Sha. [Google Scholar]

- Anan, Shigeyuki, ed. 2009b. Hisabetsumin no Nagasaki gaku: Bōeki to kirishitan to hisabetsu Buraku [Nagasaki Studies of Discriminated People: Trade and Christians and Discriminated Community]. Nagasaki: Nagasaki Human Rights Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Buraku Kakihō Kenkyujo. 2001. Buraku Mondai, Hanrei Jiten [Dictionary of Buraku Issues and Human Rights]. Osaka: Kakihō shuppan, p. 904. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara, Arikazu. 1990. Nagasaki ni okeru kirishitan dan’atsu to hisabetsu Buraku [Christian oppression and discriminated communities in Nagasaki]. Legal History Review 1990: 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fukuma, Yoshiaki. 2006. “Hansen” no media shi: Sengo Nihon ni okeru yoron to yoron no kikkō [The History of “Anti-War” in the Media: The Rivalry between Public Consensus and Public Opinion in Postwar Japan]. Kyoto: Sekaishisosha, pp. 202–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuma, Yoshiaki. 2011. Shōdo no kioku [Memories of the Scorched Land]. Tokyo: Shinyosha. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, José Delgado, ed. 1976. Fukusha Hose San Hashinto Sarubanesu OP shokan, hōkoku [Blessed José San Jacinto Salvanez OP letters and reports]. Translated by Sakuma Tadashi. Tokyo: Kirishitan Bunka Kenkyūkai. [Google Scholar]

- Hiron, Avila. 1965. Chronicle of the Kingdom of Japan [Nihon ōkoku-ki]. Translated and annotated by Tadashi Sakuma, Yoshi Aida and Iwaki Seichi. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Iechika, Yoshiki. 1998. Urakami kirishitan ruhai jiken: Kirisuto-kyō kaikin e no michi [The Urakami Christian Exile Case: The Path to the Lifting of the Ban on Christianity]. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. [Google Scholar]

- Isomoto, Tsunenobu. 1998. Nagasaki-ken no hisabetsu Buraku shi to genkyō [History and current state of the discriminated communities of Nagasaki Prefecture]. In Ronshū: Nagasaki no Buraku shi to Buraku mondai [Collected papers: History of Buraku and the Buraku issue in Nagasaki]. Nagasaki: Nagasaki Prefecture Buraku History Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Kadooka, Nobuhiko. 2012. Pisutoru to keikan: ‘hisabetsu’ to ‘bōryoku’ de Osaka wo seotta otoko Konishi Kunihiko. Tokyo: Kodansha. [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa, Midori. 2023. Zouho Kindai Buraku-shi [Enlarged Edition: Modern Buraku History]. Tokyo: Heibonsha. [Google Scholar]

- Mahara, Tetsuo. 1960. Mikaihō Buraku to kirishitan Buraku [Unliberated Buraku and Christian Buraku]. Journal of Japanese History 48: 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda, Shirōsuke. 1981. Nagasaki ni okeru hisabetsu Buraku kyōsei ijū no shojōkyō: Buraku kyōiku shi kiso ron no tame ni, Sono ichi [Compulsory Removal of the Lowest Class People, Etta at Nagasaki—A Fundamental Study of the History of Dowa Education—(1)]. Bulletin of Faculty of Education, Nagasaki University. Educational Science 28: 31–38. Available online: https://nagasaki-u.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/9784/files/kyoikuKyK00_28_02.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. 2012. Dōwa taisaku shingikai tōshin (‘Jinken kyōiku no shidō hōhō tō no arikata ni tsuite [Dai-san-ji torimatome]’ kara bassui). Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/jinken/sankosiryo/1322788.htm (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Motofumi, Sasaki. 2021. What We Religious People Have Done. Osaka: Buraku Liberation, Liberation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Motoshima, Hitoshi, Tani Daiji, Anan Shigeyuki, and Uesugi Satoshi. 2004. Zadankai: Katorikku to hisabetsu Buraku no deai-naoshi [Symposium: Re-Encounter of Catholics and Discriminated Communities]. Osaka: Buraku Kaihō, no. 540. [Google Scholar]

- Nagai, Takashi. 1949. Nagasaki no kane [The Bell of Nagasaki]. Tokyo: Hibiya shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaki City. 1975. Genbaku hisai fukugen chōsa jigyō hōkokusho [Survey Report on Atomic Bombing Damage Restoration]. Nagasaki: Nagasaki International Cultural Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaki City History Compilation Committee. 2013. Shin-Nagasaki City History. Nagasaki: Nagasaki City, vol. 4, p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaki Institute for Human Rights Studies (NPO). n.d. A Walk through Nagasaki’s Buraku History, p. 30. Available online: http://naga-jinken.c.ooco.jp/shiryo/naga_A.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Nakamura, Yoshikazu. 2018. Genbaku to yobareta shōnen [The Boy Called Atom Bomb]. Tokyo: Kodansha. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura, Akira. 2002. Nagasaki, the Praying City: Nagai Takashi and the Atomic Bomb Dead. Annual Review of Religious Studies 19: 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ramseyer, John. Mark, and Eric B. Rasmusen. 2018. Outcaste Politics and Organized Crime in Japan: The Effect of Terminating Ethnic Subsidies. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 15: 192–238. [Google Scholar]

- Shijyou, Chie. 2012. Narratives of the A-bomb at Nagasaki Junshin Educational Corporation: From Nagai Takashi to Pope John Paul II. Religion and Society 18: 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Takaki, Yoshiko. 2013. Takaki Sen’emon ni kansuru kenkyu [A Research on Sen’emon Takagi]. Kyoto: Shibunkaku shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Takayama, Fumihiko. 2017. Ikinuke, sono hi no tame ni: Nagasaki no hisabetsu Buraku to kirishitan [Live on, for That Day: Nagasaki’s Discriminated Community and Christians]. Tokyo: Buraku Liberation Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Urakawa, Wasaburo. 1943. Urakami Kirishitan shi [History of Christians in Urakami]. Tokyo: Zenkoku shobō. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Takanori. 2012. Yakuza shūdan no keisei to sabetsu: Burakumin/Chōsenjin to iu toi to no kankei kara. In Sai no keisōten gendai no sabetsu wo yomitoku. Edited by Amada Jōsuke, Murakami Kiyoshi and Yamamoto Takanori. Tokyo: Hābesutosha. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).