Abstract

In this article, I propose a collaborative preaching model for healing collective trauma. It begins with the preaching context of a society in the grip of collective trauma after a traumatic event. Taking the May 1998 tragedy in Jakarta, Indonesia, as a case study and employing descriptive, historical, and analytical methods, this study argues that the Church is called to respond to collective trauma in its ministries as part of God’s mission. The research focuses specifically on the ministry of preaching and explores theories of trauma-aware preaching to affirm that preaching can indeed be a medium for healing collective trauma. I then present a collaborative preaching model for collective trauma healing by integrating a conversational preaching approach with the local Indonesian traditions of gotong-royong and musyawarah-mufakat.

1. Introduction

While trauma conversations have been around for a long time, the COVID-19 pandemic has turned them into a familiar language heard daily across the world. This is because the trauma of COVID-19 has left in its wake an increase in mental health problems, even though the pandemic itself has passed (Geminn 2024). The pandemic has also shown us that there are two types of trauma, individual and collective and that these are intertwined. To distinguish between the two, I cite the classic definition of trauma from Kai T. Erikson in his work on the tragedy of Buffalo Creek:

By individual trauma, I mean a blow to the psyche that breaks through one’s defenses so suddenly and with such brutal force that one cannot react to it effectively…. They [Buffalo Creek survivors] suffered deep shock as a result of their exposure to death and devastation, and as so often happens in catastrophes of this enormity, they withdrew into themselves, feeling numbed, afraid, vulnerable, and very alone.By collective trauma, on the other hand, I mean a blow to the basic tissues of social life that damages the bonds attaching people together and impairs the prevailing sense of communality. The collective trauma works its way slowly and even insidiously into the awareness of those who suffer from it, so it does not have the quality of suddenness normally associated with “trauma.” But it is a form of shock all the same, a gradual realization that the community no longer exists as an effective source of support and that an important part of the self has disappeared.(Erikson 1976a, pp. 153–54)

Still, the two are different and yet inseparable, especially in the case of mass traumatic events that affect every individual in the community and result in a loss of communality. Conversely, the loss of such bonds further aggravates the trauma of individual victims as they no longer have a strong support system.

Beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, individual and collective trauma can result from other major events, such as natural disasters, violence, and war. The trauma lingers because of the impact of those events and requires attention.

In this article, while I mostly talk in terms of collective trauma, what I say about trauma recovery applies to both. We cannot heal collective trauma without doing the same for each individual in the traumatized community. Collective trauma, however, in the case of political violence in Indonesia, focuses specifically on cultural trauma, where wounds become social identities intentionally created through cultural and political means (Alexander 2012, p. 2). Therefore, the trauma healing in this article relates to Judith Herman’s understanding of recovery from individual trauma, i.e., reconnection between survivors with a community (Herman 2015, p. 3), and Erikson’s community recovery, i.e., the community offering a safe space to share their wounds (Erikson 1995, pp. 186–87). This article also presents a cultural approach to creating a new narrative of the traumatic event as a healing process.

Some questions arise about the role of the community in trauma healing; however, how does a community become a site of healing while itself living with trauma? If we imagine the community as the Church, for example, its members and their families could be a mix of survivors and perpetrators. How, then, will they heal each other? How might the Church respond to God’s call to save the world while itself still part of a traumatized society? The answers to these questions are part of a difficult and ongoing process.

Regardless, the scholars of trauma theology remind us that the theology of grace is the foundation for trauma healing and for reconstructing the community in the aftermath of traumatic events. Serena Jones underscores that the Christian community, in this case, the congregation, needs to recognize that trauma gives birth to a rich faith tradition in which unspeakable terrors meet God’s saving grace (Jones 2009, p. 10). God’s presence with traumatized persons can be seen in the story of the road to Emmaus (Jones 2009, pp. 39–40). It is manifest also in Jesus’ crucifixion, where the cross reveals God’s solidarity with people and is a site of both sin and grace. The story of the cross and of God’s action in breaking the cycle of violence is then reconstructed and proclaimed by the witnessing community, which turns them into a redeemed community (Jones 2009, pp. 78–79).

Shelly Rambo proposes another theology of grace through a theology of Holy Saturday, which she sees as a liminal space between passion and resurrection because Jesus is in She’ol. Jesus shows the fragility of God in a situation of “the utmost darkness, forsakenness, and alienation” (Rambo 2010, p. 65), and also shows the trauma victims’ situation. When he dies and goes to the underworld, he confirms the presence of God with trauma survivors and their families (Rambo 2010, p. 68). The role of the Spirit in Holy Saturday, according to Rambo, is to transfer to survivors Jesus’s spirit of endurance against violence (Rambo 2010). She then introduces a theology of Resurrection and Pentecost for the healing of perpetrators. It is a theology that allows perpetrators to acknowledge their wounds, and it is built upon the story of Jesus inviting Thomas and the other disciples to see and touch his wounds. This is followed by their transformation from death to life through the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, in a moment when the truth is revealed after their wounds are uncovered (Rambo 2017, pp. 136–38).

The grace theologies from these two trauma theologians encourage us to believe a healing community is possible because God presents Godself to those who are traumatized through the presence of others who are hurting. Sharing traumatic stories helps the traumatized become comfortable with their past and reduces feelings of isolation (Schwartz 2016, p. 48). A mutually healing community that understands what people have been through leads to the discovery that they are not alone and that this is the way God strengthens them. Similarly, the presence of both perpetrators and victims in a healing community leads to a circle of “hurt goes to hurt”, where members are able to see, feel, and reveal the wounds of others (Rambo 2017, p. 126). The presence and participation of both groups in the community, sharing the truth without judgment, and uncovering each other’s wounds are all part of the healing process of trauma (Rambo 2017, p. 129).

The importance of community in healing raises other questions: How is a healing community created, and how does it work? This article will answer these questions through an exploration of one of the ministries of the Church, i.e., the preaching ministry. In a context such as Indonesia, where preaching follows the monologue model and where preachers are considered the height of authority, it is not easy to see how such a ministry could be restorative. Furthermore, the complexity of preaching, shaped by the preacher’s perspective, can lead to a type of “narrative fracture” in which preachers fail to react to the trauma their congregation faces and avoid preaching on the subject. How might such a “narrative fracture” be overcome?1 This research has two objectives: firstly, to argue that a preaching ministry can create a healing community, and secondly, to propose a collaborative preaching model for collective trauma healing. Therefore, the first section presents the mass traumatic event that happened in Indonesia, i.e., the May 1998 riot in Jakarta, as a case study. This case study will help us realize that collective trauma is a reality in society and a real context for a preaching ministry in Churches around the world, and Indonesia in particular. Then, in the next section, I discuss the importance of trauma homiletics in responding to the reality of collective trauma and argue for the possibility of conversational preaching as a model for recovery. Finally, I offer a collaborative preaching model for collective trauma healing that combines conversational preaching and two local Indonesian traditions, gotong-royong and musyawarah-mufakat.

2. Indonesian Collective Trauma: The Jakarta Riots

The high fences around the houses and gates in the residential areas in Jakarta, the capital city of Indonesia, conceal a dark story. Twenty-six years ago, these areas were open for anyone to enter and exit freely. No special guards were hired to protect the neighborhoods. However, now the fences and gates cover the people’s vulnerable feelings and broken trust in the aftermath of the riot that occurred on 13–15 May 1998 and is well-known as the Jakarta May 1998 tragedy. Residents overcome their fears and mistrust by making themselves safe in their own houses and neighborhoods (Hun 2002, pp. 101–4). The brokenness of relationships that shows through these fences and communal gates is one of the collective trauma symptoms identified by Erikson, i.e., disorientation and loss of connections where, after a violent event, people lose meaningful connections with and trust in others (Erikson 1976b, p. 304).

In this section, I briefly explain what happened in the riot as an example of a mass traumatic event in Indonesia. I analyze the riot using collective trauma theory to demonstrate how it caused collective trauma in Jakarta society.

2.1. The Jakarta May 1998 Tragedy

Keen van Dijk describes the situation in Indonesia in 1998 in the following:

The krismon (krisis moneter—English: monetary crisis), as the current situation was called in common parlance (the term had become so current that even babies were named after it), had not only turned into a krisek (krisis ekonomi—English: an economy crisis) but now extended its titles to a krismor (krisis moral—English: a crisis of morality) and a krisper (krisis kepercayaan—English: a crisis of confidence), with growing numbers of people losing confidence in the government and representative bodies.(van Dijk 2001, p. 114)

The global currency crisis in 1997 affected most Asian countries, including Indonesia. The value of the Indonesian rupiah fell sharply from IDR 2500 per USD in November 1997 to IDR 17,000 per USD in January 1998. This led to a rapid increase in foreign debt, which the government tried to control by increasing foreign borrowing (Jusuf et al. 2005, p. 16). Many businesses, manufacturers, and private banks immediately collapsed, causing a great run on money and the layoff of many workers. Panic buying was widespread as essential goods became scarce. The government failed to revive the economy, and people lost confidence in the administration (Purdey 2006, p. 80).

There were other problems diminishing the power of President Suharto, the second president of Indonesia, who was ruling at the time. These included divisions within the military and the emergence of groups opposing the corrupt behavior aimed at benefiting the president’s family members and cronies. Suharto began to fear and suspect any group or community threatening his position. Thus, anyone who opposed the ruling regime became subject to disappearance, being taken somewhere and tortured by the military. Some were released, but others have not been heard of since (Kasenda 2015, pp. 71–72). Again, during these various political crises, people lost faith in the government. These crises triggered demonstrations throughout Indonesia, especially among university students. These protests were the starting points for riots in several cities, the largest of which was in Jakarta.

On 12 May 1998, students at Trisakti University began a demonstration in the morning, demanding reforms in Indonesia, including the resignation of President Suharto after 32 years in office, a reduction in the role of the military in the life of the nation, and an end to the corruption, collusion, and nepotism that had wrecked the Indonesian economy for years. The demonstration in the Grogol area of West Jakarta was calm and orderly. In the afternoon, however, a military unit on the flyover bridge above the demonstration fired shots after the students threw stones at police. The demonstrators immediately fled the scene, but four students were killed in the shooting (Purdey 2006, p. 122).

The next day, 13 May 1998, a large crowd gathered inside and outside the Trisakti University campus. They came to express their condolences for the deaths of the four students. They also demanded that the military and the government be held to account for the students’ deaths. As the hours passed until noon, the crowd continued to grow. After lunch, the crowd spread out in all directions around Grogol and began destroying public facilities.

It is unclear how the crowd turned to destroying and burning ethnic Chinese businesses and homes, including many of Jakarta’s major shopping malls. Television stations broadcast scenes of mobs of poor people looting the damaged shops and malls, happily carrying off whatever goods they could grab. Then, on 14 May, tragedy struck Jakarta, Tangerang, and Depok. More than ten thousand shops were broken into and looted, thousands of vehicles and houses were destroyed, and some public transportation was damaged (Jusuf et al. 2005, p. 172). Other malls in East Jakarta and Tangerang were burned on May 15. Thousands were killed because the perpetrators locked the mall doors when people were inside (Tim Relawan untuk Kemanusiaan 1998, Table 5).2 In these areas of unrest, people attempted to avoid damage to their businesses and homes by writing signs such as “this house belongs to pribumi”,3 “this house belongs to native Javanese”, and “this belongs to Muslim pribumi”, and sticking them on their fences (Jusuf et al. 2005, p. 5). Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia, was burnt down in three days.

Another drama during the May 1998 tragedy was the rape of hundreds of ethnic Chinese women. The team of Volunteers for Humanity notes that the number of victims of rape and sexual harassment reached 152 (Sumardi 2007), with victims raped and molested in front of other family members. Some victims were raped on the street, which was witnessed by many people. Some have since committed suicide, and those who became pregnant had abortions. A few developed mental problems. Their families sometimes sent them to other cities or countries to be rescued and healed, for they were traumatized (Jusuf et al. 2005, pp. 178–98).4

The State Bureau on Violence Against Women reports that victims and their families have largely chosen to remain silent about their traumatic experiences. They have accepted a “shameful and sinful feeling, obeying the family’s prescriptions, as well as a general fear and trauma related to the riot itself” (Sadli and Yentriyani 2008, p. 7). The families of the victims decided to remain silent because they feared a revenge attack if their identities were revealed to the public and the police. They felt insecure about reporting the victims’ worst experiences because there was no legal protection for witnesses and victims (Sadli and Yentriyani 2008, p. 7). In addition, victims, their families, and caregivers refused to speak to the state apparatus because of the government’s involvement in the uprising. The effect of the refusal to speak out is that the state allows the opinion that the sexual violations of the May uprising did not happen to prevail (Sadli and Yentriyani 2008, p. 15). Thus, the May tragedy became a tragic event that remains unspoken.

Subsequently, reports of the rapes have met with skepticism and have not received a response from the government. For example, the third president of Indonesia, B.J. Habibie, and several of his ministers doubted the truth of the incident because no cases had been reported. The same skepticism came from the “Badan Koordinasi Intelligen Negara” (BAKIN—The Coordinating Body for State Intelligence), which said that claims of the rape of ethnic Chinese women were only aimed at putting Indonesia in a difficult position (Pattiradjawane 2000, p. 239). However, Ariel Haryanto, an Indonesian politician, countered this by saying that the trauma of the ethnic Chinese women who were raped was so intense that they chose to remain silent: “Their suffering was unspeakable in a language of the community that has been hurt” (Haryanto 1999). Benny G. Setiono notes, “All victims and their families who were shocked and traumatized kept quiet because of the shame they had to bear” (Setiono 2003, p. 1062).

2.2. Collective Community Trauma: Analysis of the Riot

In this section, I use collective trauma theory, especially as it relates to cultural trauma, to analyze the riot. I conclude that the riot meant Indonesia became a community that lives with collective trauma. As mentioned above, this conclusion then becomes a reason to construct a homiletic framework in response.

I pointed above to the way the personal fences and communal gates in the Jakarta community reveal the collective trauma that broke people’s trust in and connection to others. Gilad Hirschberger defines collective trauma as something affecting all members of a society as part of a collective memory. The memory of the trauma goes beyond the immediate survivor and is passed on to the following generation (Hirschberger 2018, p. 1). Therefore, collective trauma has long-term effects on the second and third generations of survivors and can undermine a fundamental sense of well-being. At the social level, both generations show increased individual and collective fear, feelings of vulnerability, injured national pleasure, humiliation, a disaster-based identity, and a predisposition to react with heightened vigilance to new threats (Hirschberger 2018, p. 3).

In the case of the May 1998 riot, Rani Pramesti, a second-generation survivor, wrote in her project, Chinese Whispers, that the riot “caused a schism. A fracture in my identity”. This was the first time she asked her mother, “Are we Chinese?” and received the answer, “No”. Instead of saying “yes”, her mother claimed their family was Indonesian. However, the riot forced the family to leave Indonesia for Australia when she was thirteen. Her parents considered Indonesia unsafe for her as a Chinese person. For her project, she interviewed other Chinese women who came to Australia because of the riot. She found that members of the second generation, to whom the trauma had been passed down, were confused about their Indonesian identity, and some of them were afraid of the pribumi. They felt that the pribumi were terrible because their parents told them so (Pramesti 2014). Pramesti’s work reminds me of my D.Min. research in 2007, in which I discovered that twenty Chinese Indonesian youths, the second generation of the May 1998 riots and the third generation of the 1965 incident, felt uncomfortable among pribumi, without knowing where this fear came from (Gunawan 2008, pp. 97–98).

As a Chinese Indonesian woman who struggles with her identity, Pramesti forces herself to make sense of why her mother concealed her Chinese identity and why her Chinese Indonesian relatives retain hatred for pribumi. Her journey to find answers brings her together with scholars who explain the position of Chinese Indonesians as scapegoats for political-economic problems in Indonesia since the colonial era (Pramesti 2014). Her findings recall Neil J. Smelser’s opinion that one of the ways to create cultural trauma is to ensure there is a “moral panic” in society. This is done by scapegoating some groups for the various ills of that society. The effect of creating scapegoats in this way becomes even more complex when it is the political authorities who are doing so (Smelser 2004, pp. 52–53).

The framing of Chinese Indonesians as scapegoats has recurred constantly during various social, political, and economic crises. The Dutch colonialists, for example, placed ethnic Chinese in the second social strata, where they were used as intermediaries between the government and the pribumi. If the pribumi revolted against the Dutch policy, the first victims would be the Chinese (Sindhunata 2006, p. 387; Setiono 2003, pp. 203–4).5 The Suharto regime then continued using a scapegoat identity for ethnic Chinese. Some government regulations, especially economic policies, strengthened the Chinese Indonesians in the best financial position but placed them in the worst in terms of political power. Hence, not surprisingly, ethnic Chinese were scapegoated when the regime accused them of financial fraud (Winarnita 2008, pp. 2–3) and were considered less patriotic because they were rarely seen in political affairs. Furthermore, James T. Siegel observes that the riots in May 1998 served as confirmation that the violence against Chinese Indonesians had become normalized in the national culture under the Suharto regime. This presents a significant danger to the future bonds of Indonesian society because a violent culture can always return (Siegel 2001, p. 121).

Another social construction for intentionally creating cultural trauma through state terrorism has been the use of Chinese Indonesian women as a target of violence (Smelser 2004, p. 18; Alexander 2012, pp. 6, 13, 15–25).6 There are three elements to state terrorism, with only one goal: spreading fear to a broad audience. All three elements appeared in the May 1998 riot (Haryanto 1999, pp. 124–25).7 The first and second elements of such terrorism—violence against a minority group by a majority, and conducted in a public space so that the message of the incident will spread quickly–occurred with the mass public rape of Chinese Indonesian women. These women were then reluctant to testify because they believed certain military personnel were complicit in these events (Purdey 2006, p. 145). The third characteristic of state terrorism, fear of violence by state officials, came from criminalizing the community, the normalization of anti-Chinese violence, and the use of Chinese Indonesian women’s bodies as the target (Hikmawati 2017, p. 351). As I mentioned above, the normalization of anti-Chinese violence was achieved through official policies, including the standardization of the myth of women as objects of male power. Moreover, Chinese Indonesian women are still victimized by the media through fake and negative news about rape victims, which means the reality of mass rape remains in doubt (Hikmawati 2017, pp. 355–56).

Although in this case analysis, I focus on the study of violence against Chinese Indonesians, the impact of this incident—and previous tragedies—has severed the bonds of kinship in society. The second group—Chinese Indonesians and indigenous people—admitted to not feeling comfortable when they were in different ethnic groups. Negative stigmatization of ethnic Chinese or pribumi due to post-incident trauma resulted in the emergence of suspicion between the two in their relationship as members of Indonesian society (Gunawan 2008, pp. 99–101). Moreover, violence that targets women or other minority groups as victims is a pattern that has repeatedly been used as terror in several conflicts in Indonesia. In the anti-communist party tragedy in 1965, the military under Suharto successfully spread false propaganda about the evil of the Indonesian Communist Party. The army and its allies conducted propaganda, for example, about the Gerwani—the Indonesian Women’s Movement, a non-governmental organization affiliated with the Indonesian Communist Party. They depicted the Gerwani as cruel women who castrated and killed six military generals and a lieutenant while dancing and singing. The hate campaign toward them spread very fast in Indonesia (Roosa 2006, p. 5; Wieringa and Katjasungkana 2019, p. 14).8

3. Trauma-Aware Preaching: A Response to Collective Trauma

Kimberley Wagner notes there are two modes of preaching about trauma: trauma-responsive preaching and trauma-aware preaching. Trauma-responsive preaching is preaching after and in response to a traumatic event, while trauma-aware preaching is preaching that seriously considers and is sensitive to the traumatic realities that may be unknowingly present in congregations daily (Wagner 2022, p. 224). In this paper, I focus on trauma-aware preaching because the lack of response to trauma after tragedy is often due to a lack of awareness about its impact on the congregation. My research with four preachers who witnessed the May 1998 riot revealed just such a lack of response to the trauma in their sermons. There are at least three reasons for this silence: a lack of understanding of trauma and its effect on life in the community, a limited understanding of preaching in the context of violence, and the fact that the preachers themselves experienced trauma from the riot (Gunawan 2023, p. 128).

I thus agree with Joni S. Sancken’s argument about the urgent need for trauma-aware preaching. She argues that preachers must realize their own traumatized condition, an awareness that then becomes the journey companion for congregations who are also experiencing trauma. Trauma-aware preaching creates the opportunity to speak about the pain of traumatic experiences and to legitimize its effects. (Sancken 2019, p. 3).

Trauma-aware preaching builds upon the “middle space” trauma theology of Rambo. She calls this “middle space” the space “in-between”. It is a space where witnesses in the “death” position embrace the disruption of the trauma event, and are then in a position to move forward (Rambo 2010, p. 60). Preaching in-between means preaching the reality of hopelessness through the death of God, while at the same time, the existence of a new beginning through the resurrection of God. Such preaching admits there is a rupture between death and life, yet there is a Spirit who bridges the two and makes it possible to cross between them (Rambo 2010, pp. 72–73).

Hence, such preaching invites preachers and listeners to dwell in a liminal space between trouble and grace, despair, death, and resurrection (Travis 2021, chap. 2, p. 1341, Kindle). It offers stories of life and death at the same time. The sermon does not always follow an organized and coherent flow and end with a clear conclusion (Travis 2021, chap. 2, p. 1350, Kindle). “Preaching in-between”, as Travis describes preaching in the middle space, makes room for irregularity caused by narrative fractures. Wagner makes this definition clear:

Such preaching takes seriously the experience of narrative fracture, acknowledging and even welcoming the fragments of people’s experience. It welcomes the hurt, pain, questions, unknowability, confusion, and frustration. Such preaching does not shy away from hard emotions, grief, or lament but embraces and even models these hard truths in the preaching event. At the same time, this preaching does not resist the longing for hope or the promises of God that, though not always sensed in the moment, are already present and coming toward us. Such preaching lives in the tension between brokenness and hope, between death and resurrection, between loss and redemption.(Wagner 2023, p. 96, Kindle)

The definition of preaching in-between presents its vulnerability and, at the same time, challenges the tension between private and public spaces. Trauma is a private matter and speaking about it from the pulpit is a delicate matter. However, preaching also provides an opportunity to speak about the wounds of trauma in a public space to effect healing. It is my opinion that there are three aspects to preaching in-between as an opportunity: preaching as public theology, as public witness, and as an act of reconciliation.

First, as a public theology, preaching in-between is inseparably linked to both private and public spaces. Even though preaching emanates from a preacher’s private space of sermon preparation, it occurs in a public space because “the preacher voices the message of the community of faith, articulating it to that community, and from that community to the world” (Craddock 2010, p 18). In other words, preaching invites the congregation to become members of the world community. As a form of community in the world, preaching is public theology with the function of negotiating Christian traditional claims with public life claims and thus helping Christians create a public testimony (Bond 2010, p. 79).

Judith Herman argues that the social context created by political movements for human rights determines whether recovery or destruction will result from trauma. A strong political movement is an active process of giving voice to victims and preventing the active forgetting of the history of violence (Herman 2015, p. 9). As I observed above, the May 1998 tragedy was an intentionally created cultural trauma, and it is now a social context for preaching as a public theology. This reminds me of Septemmy Lakawa’s statement that the site of trauma for Chinese Indonesians is concealed through the rupture of public space because the violence occurred in various places. This rupture means the history of violence has no identifiable space and no visibility. She asserts that the reimagining of public space, which explains public suffering with a plausible narrative aimed at reclaiming everything that has been lost, is a theological task and must be carried out by the church in its ministry spaces, including the worship space. For Indonesian Protestantism, the worship space generally refers to the pulpit site. The voices from the pulpit have God’s authority to carry out the reclamation process, and the Church is involved in this process. Therefore, she concludes that preaching as public theology is both private and public: “The listeners are individuals, but at the same time, the church becomes public when these individuals cannot work alone; they are a collective body” (Gunawan 2023, p. 136).

Second, preaching in-between is a public witness. Witness and testimony are two important elements in preaching and trauma recovery. Preachers are witnesses of the truth from Scripture and life, which they then share as a testimony to listeners. Listeners testify this truth to the world in their daily lives. Meanwhile, in trauma recovery, the persons who experienced trauma articulate the truth of violence as a testimony. The process of articulating the truth requires others to create a safe space for them to speak and to accept them honestly and fully. The witnesses and the testifier then re-narrate the traumatizing events in order to break the cycle of repetitive violence (Jones 2009, p. 32). The pulpit is then an in-between where preachers make room for the victims to talk about their trauma and injuries. When preachers testify about the trauma, they create a healing community because those who are traumatized are no longer alienated and alone (Travis 2021, chap. 3, p. 1623, Kindle).

However, preaching in-between places the preacher in tension between victims and perpetrators. A preacher must stand beside the victims and be the very opposite of the perpetrators. At the same time, they must preach to the perpetrators of hope and grace with pastoral sensitivity (Travis 2021, chap. 3, p. 1668, Kindle). Another tension arises when preaching in-between is required to call out traumatizing events and situations. According to Wagner, this sort of preaching involves bold truth-telling, “Preachers need to be honest about what has happened and what has been lost and broken” (Wagner 2022, pp. 97–98, Kindle). An honest way of preaching is risky for both preachers and listeners. When bearing witness in preaching means showing that the events are real in the community’s life, the risk for preachers is that they must re-experience their own pain. And for the listeners, such sermons can re-trigger their trauma.

Concerning the reality of preaching in-between as outlined above, Joni Sancken suggests that we need a “compassionate witness”, i.e., a witness who refers to humanity’s values and has wisdom when reacting and responding to traumatic events (Sancken 2019). There are three steps to becoming a “compassionate witness” in preaching in-between. Inviting members of the preaching community to share and discuss stories of trauma is the first step of the process. The goal of this step is for the community to admit and witness to the trauma that exists in the pews and society (Travis 2021, chap 3, p. 1713, Kindle). The second step is to give the community the opportunity to acknowledge that trauma is caused by complex catastrophes and not to simplify the problem with a quick solution (Wagner 2023, p. 99, Kindle). Preachers thus have the challenge of addressing unanswerable questions about the events, such as the connection between suffering and theodicy. In the final step, Sancken proposes “symbolic action”, which takes place in the context of worship (Sancken 2019, p. 13). Here, preachers invite the community to remember the events by pointing to the sites of traumatic events.

Third, preaching in-between as an act of reconciliation delivers hope. It is a healing process that goes beyond naming wounds to having the courage to admit mistakes, to forgive, and to repair relationships. Rambo recalls the stories of the risen Christ from the Gospel of John, who appears to the disciples in just such an act of restoration. In the first story, Jesus visits the disciples in the upper room, a place where they hide their wounds and live in fear, guilt, and helplessness. When Jesus asks them to go out and breathes upon them with the Holy Spirit, the step of restoration occurs. Jesus delivers them from holding on to the past so that they might move forward with forgiveness through the Holy Spirit. The second story is when Jesus invites Thomas Didymus to touch his wounds. This is part of the recovery process of bringing the wounds to the surface, which means the wounds are no longer hidden but accepted. The transformation occurs when the wounds are registered and have surfaced. Rambo concludes that the healing process in the traumatized community is the courage to re-enter wounds, experience forgiveness, and restore relationships (Rambo 2017, pp. 81–84).

Wagner goes deeper into preaching in-between as an act of reconciliation with the concept of the preaching of eschatological hope. Such preaching demonstrates God’s character, who promises redemption and a new life without ignoring or erasing pain and suffering. It “takes such suffering and transforms it” (Wagner 2023, p. 106, Kindle). The transformation is God’s invitation to the traumatized community to partner in God’s restoration and be faithful agents in building justice (Wagner 2023, p. 109, Kindle). The aim of eschatological preaching is to move the congregation from witnessing to acts of reconciliation. Congregations acknowledge their wounds, admit their pains, recognize that their wounds have produced systemic evil, and defeat them as the work of God. Therefore, such sermons invite the congregation to experience God’s redemption through repentance, mutual forgiveness, and reconciliation of the broken community.

4. Conversational Sermons as Collaborative Preaching Model

Based on my research into traumatized communities and the trauma-awareness preaching above, I acknowledge that collective trauma healing should focus on creating a healing community amidst the fractured bonds of the community. Preaching in-between challenges us to find a preaching model for collective trauma healing. Hence, in this section, I discuss the collaborative preaching model that I believe offers a fit, although not a perfect one, because of its values, characteristics, and elements. In my opinion, this model aligns with the need to create a safe space for speaking about trauma as part of the trauma-healing process in the community. The collaborative preaching model is the foundation of my proposal for an Indonesian-influenced model in the next section.

Collaborative preaching, in the form of conversational preaching, was introduced by several homiletics scholars in the late 1990s. Two of the prominent scholars here are John S. McClure and Lucy Atkinson Rose, who use the image of a roundtable for conversational preaching. McClure roots his proposal in leadership authority in the community, while Rose approaches her version of the model from a feminist perspective. Both find inequality in prevailing preaching practices. Rose, for example, recognizes the reality of giving too much power to preachers in pulpit ministry. Such a practice always ignores the voices of marginalized groups and destroys the meaning of preaching as sharing the Word for all (Rose 1997, pp. 2–3). By contrast, roundtable preaching possesses a nonhierarchical leadership style in that the preacher has equal authority with the congregation. As a form of conversational preaching, the roundtable model accepts and respects personal experiences that intertwine with Scripture, tradition, and heritage. This preaching style shapes the proclamation of the gospel, which in turn has implications for the life of the congregation. Mutuality, solidarity, equality, and inclusivity are the values of roundtable preaching (McClure 1995, pp. 51–52; Rose 1997, pp. 121–31). As his bottom line, McClure emphasizes that the model brings about justice and love. There is equality in shared interpretations and spiritual experiences as God’s children welcome others in compassionate solidarity (McClure 1995, p. 53).

Following McClure and Rose, Wesley O. Allen, Jr. enlarges the understanding of conversational preaching. He bases his theory on a concept of conversational ecclesiology as the theological proclamation of the whole congregation. He argues that conversations within and between the church and the world can contribute greatly to congregations and their members, even creating meaning for their lives and communities (Allen 2005, pp. 17–21). There are three features to his conversational preaching. First, the relationship between preacher and listener is one of conversation. Second, this conversation is based on an egalitarian, reciprocal relationship. Preacher and listener practice “reciprocal listening” in a conversation that uses the language of Christian faith as its primary resource (Allen 2005, p. 41). Third, in structuring conversational preaching, preachers address the relationship between different contexts, namely, personal faith (the personal context), the experience of the listeners (the congregational context), the theological position of the Church (the theological context), and the stories of the world outside the Church (the sociohistorical context). In this way, preachers achieve the goal of this model, which is to show God’s presence to people and the world and to draw out the implications of that presence (Allen 2005, pp. 46–49).

One important thing to note about the conversational preaching model is Rose’s reminder that it requires a trusted and safe place for all members to speak and share their thoughts (Rose 1997, p. 121). This model thus requires ethics and etiquette. I borrow from Rebecca Chopp’s poetics of testimony to talk about the ethical features of conversation. There are three characteristics to such conversational ethics: the phronesis of empathy, solidarity in difference, and transcendence as possibility and practice (Chopp 1999, p. 44). In the first characteristic, the phronesis of empathy, participants in the conversation have the ability to recognize and understand that they are different from others (Chopp 1999, p. 45). The second characteristic, the solidarity of difference, means that we learn to live together in difference in ways that generate transformation and redeem common suffering (Chopp 1999, p. 46). The third characteristic, transcendence as possibility and practice, is the ethos of living together in a community that imagines a new public space representing hope for a better future (Chopp 1999, p. 47). With these three ethical features of conversation, the collaborative preaching model presents a form of faith community that respects and embraces difference and moves forward in God’s mission of transformation for this world.

Meanwhile, Allen helps us with the etiquette of conversation. He identifies three rules of etiquette in conversational preaching. First, the rule of reciprocity is that all participants show respect and concern for other discussions and then share their own experiences and interpretations of the presence of God (Allen 2005, p. 29). Second, the rule of participation is that all participants must be active and able and willing to offer their thoughts, questions, and points of view, and to challenge others to participate fully in the conversation (Allen 2005, p. 30). Third, the rule of commitment is that to foster trust, participants must be committed to the possibility of new discussions and complex issues as part of the ongoing conversation (Allen 2005, p. 30).

If conversational preaching is collaborative preaching, then we need to recognize several forms of collaboration in this model. I note there are three collaborations: collaboration between people and God, between people themselves, and between people and sermon resources. Collaborative preaching claims God is the divine partner of human beings: even God, through the Holy Spirit, participates in human–human discussion (Rose 1997, p. 97). The conversational sermon facilitates people encountering Jesus through dialogue among themselves and with God (Hannan 2021, p. 36). These theological claims impact the purposes of this model, which is to invite all worshipers to make meaning of their lives and the world with all their diverse encounters with God (Allen 2005, p. 45); to present the congregation with a biblical message that will impact the formation of their own life and mission (McClure 1995, p. 50); and to nurture the essential conversation of God’s people by setting and interpreting the texts of Scripture as the speaking Word in their lives (Rose 1997, p. 98).

Collaboration between people is the principle of this model, and it is a ministry for the entire congregation. This means that collaboration occurs between preachers and listeners who are regular churchgoers or who occasionally join the worship and even with strangers who participate in virtual services. The other form of collaboration in this model is with church staff members, the volunteers who work in ministries, and with people or communities outside the congregation. McClure even suggests that this model should include people who are not members of the church and non-Christian but who have some connection with the church (McClure 1995, p. 62). Diverse identities of race, ethnicity, color, language, belief, and various social, educational, economic, and political backgrounds all facilitate diverse perspectives on Scripture interpretation, context, and ways of seeing life and world events. Everyone has life-related stories that can deepen the congregation’s conversation about God, life, and the world. In the matter of collective trauma, the model brings survivors, perpetrators, and witnesses to the conversation table. Some may come with guilt, shame, and anger; some may express feelings and memories of the events, while others may cover them. Some may produce defensive arguments, and some may be silent. The conversational sermon gives everyone space to share their memories, experiences, and voices.

Preachers generally use a range of resources to prepare, perform, and assess their sermons. Thus, collaborative preaching invites participants to collaborate with biblical interpretation resources. The diverse backgrounds of the participants open the possibility of using many hermeneutical approaches—historical-critical and contemporary social context interpretation, for example. For their part, Elizabeth Boase and Christopher G. Frechette introduce a type of trauma hermeneutics that intertwines historical-critical approaches with the psychological, cultural, and sociological impact of traumatic events in a way that respects traumatized individuals and communities (Frechette and Boase 2016, p. 13). They affirm that by creating narratives that process past trauma and foster resilience, trauma hermeneutics can restore healthy identity and solidarity (Frechette and Boase 2016, p. 15).

The next collaboration is with the forms of preaching. Ronald Allen points out that conversational preaching can employ various sermon forms as long as these forms emphasize ethos, passion, or purpose, as this model emphasizes the quality of dialogue (Allen 2004, p. 19). However, Rose proposes that the best sermon form of this model is a combination of inductive narrative and storytelling. This combination, she argues, involves the congregation in shaping more meanings from the stories of their own experiences than preachers can generate (Rose 1997, pp. 113–15). Some trauma-preaching scholars suggest using the storytelling form for trauma healing. Storytelling gives traumatized individuals or communities what they need most: a voice. Voice is God’s way of showing solidarity with those who cry out against injustice. It also connects victims and communities to the God who liberates and transforms them (Hudson and Turner 1999, p. 38). Sancken also asserts that storytelling is a way of healing because it helps the traumatized find ways to make sense of a traumatic event. She explains, “Stories remind us of what is important, what we deeply cherish, and what we want to preserve. In the aftermath of trauma, when so much is up in the air, storytelling can be a grounding and orienting practice” (Sancken 2022, p. 107).

The last collaboration between people and resources is the employment of technology. We live in a digital culture in which technology plays an important role. Technology facilitates a new way of being oneself, of living with others, even with God. Moreover, we cannot avoid technological progress—the preaching ministry benefits from technology. Technology gives the Church the opportunity to walk in faith with a new direction: continuously learning, creating the widest possible networks, organizing collaborations with people and communities inside and outside the church, and maximizing creativity to create meaning (Panzer 2020, pp. 3–5). Technology can help the preaching ministry access voices from inside and outside the church through social media. In fact, Hannan remarks that the preacher can engage with people during the sermon using video calls, chat, breakout rooms, or the screen-sharing feature (Hannan 2021, p. 127).

I conclude from the collaborative preaching model outlined above that it can be a vehicle for collective trauma healing. This model is more than a group preparing a sermon; it becomes a safe place for bringing together voices, thoughts, and life experiences of God, self, and the world. Such preaching provides space for traumatized individuals and communities to voice their grief and be restored by sharing stories. All participants are equal in the partner–partner relationship model between preachers and congregation.

5. Indonesian Collaborative Preaching with the Concepts of Gotong-Royong and Musyawarah-Mufakat

In previous sections, I shared the reason for proposing a preaching model for collective trauma healing. As an Indonesian citizen who is living with intergenerational and collective trauma, I experience how trauma affects me, individually and collectively. I understand why similar patterns of violence have occurred in Indonesia and are likely to continue to occur in the future. This is because Indonesia has never resolved its conflicts by paying attention to the traumas that result from them. Trauma is never dealt with and healed; the deeper result is the breakdown of strong bonds in Indonesian society. Therefore, I build the argument that, as a Christian community, the Church is called to deal with trauma as part of God’s mission to the world. In the multicultural context of Indonesia, the Church’s members and churchgoers are diverse in terms of ethnicity, culture, and theological thinking. Similarly, as I mentioned above, in the context of trauma, the witnesses, the survivors, and the perpetrators of the tragedy could be members or churchgoers of the church. They sit together in the pew in the same church. In this case, the Church’s calling is to be a healing community—a place to convey truth, forgiveness, and reconciliation—through its ministries, specifically the preaching ministry. The conversational homiletics approach offers the church the possibility of a collaborative preaching model for collective trauma healing.

Hence, this section is my proposal for a collaborative preaching model for collective trauma in the Indonesian context. I acknowledge that Indonesia has many traditional virtuous practices for living in the community. Since collective trauma has damaged the commonality in society, I have chosen two local traditions with high community values. These two local traditions interact with the collaborative preaching theory discussed above to create a uniquely Indonesian model. I discuss the two concepts of local traditions that I use, namely gotong-royong and musyawarah-mufakat, and then propose the structure and elements of the collaborative preaching model that I offer for collective trauma healing. As an additional note, although I present a sermon model in this article, in the Indonesian worship tradition, my proposal cannot be separated from the series of Christian worship liturgies that integrate all elements of its worship.

5.1. Indonesian Communal Local Traditions: Gotong-Royong and Musyawarah-Mufakat

5.1.1. Concept of Gotong-Royong

The term gotong-royong is rooted in the Javanese words “ngotong” and “royong,” which mean “lift or work” and “together” (Simarmata et al. 2020a, p. 6). Literally, the term means “several people carrying something together” (Bowen 1986, p. 546). In simple terms, John R. Bowen defines gotong-royong as harmonious social relations in a Javanese village manifested through communal work done in mutual exchange. This tradition demonstrates the community’s ethos of selflessness and concern for the common good (Bowen 1986, p. 546).9 He explains that, as collective work, gotong-royong occurs in three distinct ways: a labor exchange, generalized reciprocal assistance, and labor mobilized on the basis of political status. A labor exchange between individuals or groups operates for specific common social projects, such as major agricultural tasks like hoeing, plowing, planting, and harvesting. The second type of gotong-royong is mutual aid, based on the idea of generalized reciprocity. Community members are obligated to help others with special events. An example of this was when I witnessed my mother and sisters cooking for our neighbors when someone married or died. The third type of gotong-royong is when people are mobilized for community services, such as building or repairing an irrigation system, or a district road, or where community members take turns keeping their neighborhoods safe at night (Bowen 1986, pp. 547–48).

Some scholars argue that gotong-royong is not only a system of social governance but also a virtue of life that reflects the noble values of humanity, such as togetherness, tolerance, care, and high respect for each other (Simarmata et al. 2020a, p. 3). It demonstrates a positive attitude toward spontaneous and sincere solidarity and equality and is aimed at helping those who are weak in order to achieve collective welfare (Simarmata et al. 2020b, p. 2). In post-colonial Indonesia, gotong-royong was used to fight imperialism and capitalism at the national level. Sukarno, the first Indonesian president, declared, “Gotong-royong is necessary in the fight against imperialism and capitalism in the present, just as in the past. Without bringing together all our revolutionary forces to be thrown against imperialism and capitalism, we cannot hope to win!”(Bowen 1986, p. 551). Moreover, the spirit of the tradition encourages the community to build resilience in the event of tragedies. In his research on Lombok Island in the aftermath of the earthquake in 2018, Jop Koopman concludes that the victims survived because of the gotong-royong spirit. They shared everything they had during a liminal period, the period before the arrival of relief supplies from the government and the NGOs. He also finds that the stories of victims’ resilience through gotong-royong create the interfaith collaboration needed in Indonesian society, which has a history of interreligious conflicts (Koopman 2021, pp. 285–86).

Unfortunately, gotong-royong loses meaning when certain parties use it for their own benefit. Koentjaraningrat mentions that in Indonesian history, this concept was misused and turned into rodi (forced labor for communal purposes) during the Dutch and Japanese colonial periods (Koopman 2021, p. 283). Similarly, the state intervened in rural Indonesia during the Suharto regime, and gotong-royong was used to obtain free local labor for development and state interests. The government thus manipulated gotong-royong to mobilize workers and control villages (Koopman 2021, p. 284).

5.1.2. Concept of Musyawarah-Mufakat

The term musyawarah-mufakat occurs as the fourth of five principles of Indonesian state ideology, which is a form of democracy led by the collective wisdom and the unanimity that arises out of deliberations amongst representatives. The concept of musyawarah-mufakat refers to the practice of general agreement and consensus to achieve unanimity in village assemblies, i.e., the Javanese village tradition of making community decisions. The term itself comes from Arabic: “syawara” means to deliberate; “muwaafaqotun” means unanimous. Koentjaraningrat calls this model a manifestation of the ethos of gotong-royong because of its commitment to maintaining harmony in community life (Koentjaraningrat 2007, p. 397). He explains:

This unanimous decision can be reached by a process in which the majority and minorities approach each other by making the necessary readjustments in their respective viewpoints or by an integration of the contrasting standpoints into a new conceptual synthesis. Musjawarah and mupakat thus exclude the possibility that the majority will impose its views on the minorities. Musjawarah and mupakat, however, imply the existence of personalities who, by virtue of their leadership, are able to bring together the contrasting viewpoints or who have enough imagination to arrive at a synthesis integrating the contrasting viewpoints into a new conception.(Koentjaraningrat 2007, p. 397)10

This definition demonstrates that musyawarah-mufakat is a form of egalitarian leadership that provides space for both majority and minority groups to express their points of view. In order to reach a joint decision, the two sides will engage in a dialog and integrate the different points of view in a new concept.

The musyawarah-mufakat system is influenced by Islamic teachings that emphasize a peaceful approach to resolving conflicts. In my research, I discovered the effectiveness of the musyawarah-mufakat model of conflict resolution through my interview with a woman leader involved in the reconciliation movement following the Muslim–Christian communal violence in North Maluku. As a survivor of this violence, pastor and theologian Margaretha Ririmasse testifies that she and her friends gathered groups of Muslim and Christian women for meetings. She affirms that through these conversational meetings, musyawarah-mufakat created a transforming spirit among the groups:

In those meetings, we shared our stories a lot. Before we encountered each other, we blamed each other, and after sitting together and sharing our stories, we realized that we were victims of the conflict. From those conversations arose the desire to fight together [against division]. We showed all the men who were still angry [because of the conflict], rather than retaliating against each other, it was better if we sat together and talked! From our conversational meetings, the peace conversation has developed until now.(Gunawan 2023, p. 233)

She adds that the peace talks started by this group of women gave rise to two groups involved in peacebuilding and reconciliation: the Moluccan Ambassadors of Peace, whose members are both men and women and the Youth Ambassadors of Peace, a Muslim–Christian youth group in Maluku that engages in peacebuilding activities.

5.2. Aims of the Indonesian Collaborative Preaching Model

Exposure to the two local traditions above reveals their values of cooperation for overcoming common problems, fostering kinship, sincerity in sharing, and maintaining harmony in social communities. Those values are important for restoring the broken communal bonding caused by trauma. A benefit of using local traditions as the basis of my homiletical framework for a collaborative preaching model is that both traditions are retained in the lives of Indonesian people. This model is quite familiar to Indonesian culture, but, at the same time, it has its struggles because the deductive preaching approach is still a dominant preaching tradition in Indonesia.

The first part of my proposal concerns the purpose of the Indonesian collaborative model. Knowing this model’s goals will help us see its shape. From the purpose of this model, we recognize the role of preaching in collective trauma healing. Just as the scholars of conversational preaching have aims for their models, I offer three purposes for the Indonesian context of a community living with collective trauma. These are to generate a safe community for traumatized individuals and communities, to name the collective trauma, and to rewrite the history of violence.

5.2.1. Generating Safe Community

The collaborative community and ministry—in this case, church and preaching—are inspired by Jesus, who creates a community with his disciples that has the values of equality, solidarity, trust, welcome, and love. Those values echo the meaning of gotong-royong in Indonesian society: working together to solve community problems and mobilizing people to help their neighbors. Such values emerge from collaborative preaching that involves congregations and communities sharing their life experiences as part of the conversation of proclamation. This model places each participant in a dialogue that honors their own voice, the voices of others, and the voices of Scripture in a reciprocal relationship. Therefore, I am convinced that this model can truly be a medium for collective trauma healing. I offer the following arguments for that statement.

First, the definition of “conversation” shows us that individuals and communities are transformed when the community intentionally initiates reconciliation and healing processes in their dialogue Allen (2005, pp. 22–23).11 Second, collaborative preaching intentionally focuses on creating space for participants to share their stories, which are born from their encounters with God, others, and the world.12 Third, trauma recovery occurs when victims have a positive support system (Herman 2015, pp. 162–72). The collaborative preaching model is concerned with creating a safe community for victims in the process of conversation. Through its ethics and etiquette, we understand that this model guarantees a sense of safety in the conversational community.

5.2.2. Naming the Trauma

Preaching in-between as a public testimony encourages survivors, perpetrators, and witnesses to testify about their wounded experiences so that they might recover from the trauma. Through witnessing, they share what has been hidden and thus open the way for change and transformation. Witnessing in preaching recognizes our experiences as gifts from God that can be a source of hope for traumatized people or communities. Therefore, the collaborative preaching model incorporates people’s testimonies into the narrative, providing tentative and challenging words to those struggling with their trauma as part of their journey of questioning, correcting, and interpreting God, others, and the world. During sermon conversations, participants are invited to name, acknowledge, and discuss their traumas.

5.2.3. Rewriting the History of Violence

In his cultural trauma theory, Jeffrey C. Alexander suggests “cultural clarification” as a trauma-healing process. This is achieved by creating a new master narrative that clearly represents the nature of the pain, the nature of the victims, the relationship of the trauma victims to the broader community, and the attribution of responsibility (Jeffrey C. Alexander 2012, pp. 17–19). As part of my study of the Jakarta May 1998 tragedy, I listened to a similar proposal for the healing process from the witness to and mentor of the victims. She asserted that the healing resolution for the victims and their families is historical clarification because this is a way of giving people truth and justice and teaching the next generation about collective trauma (Gunawan 2023, pp. 240–41). From these suggestions, in my opinion, collaborative preaching in the Indonesian context needs to focus on the goal of rewriting the history of the riots as part of a process of historical clarification. This clarification is the Church’s attempt to seek the truth from the May 1998 tragedy in accordance with the gospel spirit of proclaiming God’s truth.

5.3. Elements of the Indonesian Collaborative Preaching Model

5.3.1. Participants of the Collaborative Preaching Group

Scholars of conversational preaching agree that the participants in this group model are congregation members. However, this model is also open to participants from outside the congregation, such as neighbors who live near the congregation or experts on special topics (McClure 1995, p. 62; Hannan 2021, p. 100). In the case of trauma, the experts might be psychologists and psychiatrists, accompanying witnesses from victims and families, or other religious leaders willing to discuss violent conflicts. I add that another group that can participate is the generation that did not experience the events firsthand but inherited the trauma from the previous generation. In collective trauma healing, the presence of transgenerational groups—the first generation and the generations that experience the traumatic events only indirectly—reconstruct collective meaning by dispensing with their individual trauma for the sake of group resilience (Hirschberger 2018, p. 3; Eyerman 2004, pp. 74–75).13

5.3.2. Gathering the Participants

McClure suggests using church bulletins to invite congregation members and handing out flyers inviting neighbors around the church to participate in the model group (McClure 1995, pp. 63–64). Inviting people in this way does not always work in the context of trauma, however, because not everyone feels comfortable talking openly about these issues. There are at least two ways to overcome this. The leader can invite members with direct and indirect experiences with the traumatic event. Alternatively, the preacher can select small groups already formed within the congregation, such as choir, Bible study, and sports groups. Both of these methods will make it easier to create a trusting environment because there are already good relationships. To maintain trust, participants must agree on the conversational etiquette, such as maintaining confidentiality. A common agreement that needs to be considered is the willingness to hear, appreciate, and not judge stories from all participants. This is the spirit of gotong-royong and musyawarah-mufakat that operates in reaching mutual agreements.

5.3.3. Choosing the Text for a Sermon

Trauma-aware preaching experts believe that the lament genre of the Bible provides appropriate texts for sermons in this model. The genre encompasses the aim of trauma healing: giving voice to silent individuals and communities and liberating them by sharing their grievances and petitions to God as part of their faith journey (Wagner 2018, p. 11; 2023, p. 181). The lament genre can create a language of solidarity between society members who have experienced oppression and injustice (Sancken 2022, p. 79). Last but not least, the genre opens up space for mutual conversations so that wounded communities might hear voices other than their own.

5.3.4. Biblical Interpretation

The process of finding the message and purpose of the sermon, the good news, comes from the process of interpreting the text. In the case of trauma, Sancken suggests six interpretive tools: (1) preachers use Scripture, especially stories and poetry, as the source of the faith language of trauma victims and survivors; (2) preachers dig deeply into the text to create space for traumatized listeners to recognize and accept the reality of the trauma they have experienced; (3) preachers connect the reality of a painful trauma to God’s grace by focusing the interpretation on God’s restorative power; (4) preachers use typology to focus the interpretation on God’s restorative power; (5) preachers use typology from the Bible, such as biblical figures-as-types, to help listeners name their wounds and make sense of the trauma; and (6) preachers use a theological hermeneutic of the cross and resurrection for interpreting the text as part of a healing process that moves from the experience of suffering to the hope that God is working in people’s lives (Sancken 2019, pp. 26–36).

Because the participants in the collaborative preaching group are lay people, several methods of interpretation involve experience, knowledge, skills, and emotions. Sarah Travis, for example, suggests the Bibliodrama model, in which all participants act out the story of the text used for the sermon. In her view, this method connects all participants emotionally and psychologically to the text and becomes an educational and therapeutic process as they role-play a traumatic biblical story (Travis 2021, chap. 5, pp. 2760–87, Kindle). In addition, it is very important to consider interpretations that prioritize the participants’ feelings as they read the text. Allen suggests that in text interpretation conversations, the question should be: “What emotions are expressed in this text? What feelings does this text evoke?” This approach, he argues, can reveal hidden meanings. In the context of trauma, it can provide another language for participants when they are experiencing a “fractured narrative” due to trauma (Allen 1984, pp. 105–9). The bottom line of all these proposals for interpreting texts is to reflect the values of gotong-royong and musyawarah-mufakat, where all participants have an equal opportunity to interpret without being judged right or wrong.

5.3.5. Location and Seating Arrangements for Sermonic Conversation Meetings

The whole process of the collaborative preaching model is focused on collective trauma recovery. Therefore, the meeting location and seating arrangement are important. The sites of the original events might thus play an important role in reconstructing a new narrative from the collective memory (Jeffrey C. Alexander 2012; Lakawa 2011, p. 233). Another option is for the group to set up a room in the church and decorate it with objects, such as photos, books, or artwork related to the topic of the sermon and the traumatic event. The musyawarah-mufakat tradition of making communal decisions in an informal way might also be reflected in the location and seating arrangements. Meetings in that tradition are usually held in the community or in one of the residents’ homes, where participants sit on the floor and share food. Such a tradition reflects the values of equality and simplicity.

5.3.6. Sermonic Conversation

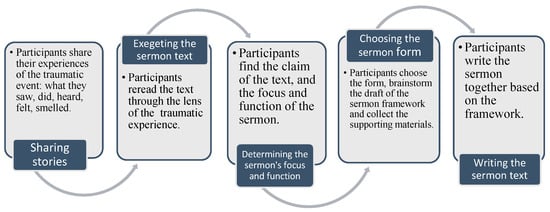

Sermonic conversation is one of the important processes in this model. Here, conversations about traumatic experiences intertwined with Scripture aim to produce a sermon script for delivery and facilitate recovery as participants talk about their wounds and hear how the Bible speaks about their experiences. There are five steps in this process: sharing stories, exegeting the sermon text, determining the focus and function of the sermon, choosing the form of the sermon, and writing the sermon text. The activities that the participants perform in each step are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sermonic Conversation Discussion.

5.3.7. Design of Feedback

Feedback after collaborative preaching has several important functions (McClure 1995, pp. 65–66). It ensures listeners are hearing the gospel for the purpose and with the impact the preacher expects. Feedback makes the preacher aware of possible communication breakdowns and resulting misunderstandings from listeners. Participating in feedback also encourages the laity to enter the process of learning Scripture and thinking theologically, and finally, feedback increases mutual trust and solidarity between preachers and listeners (Hannan 2021, pp. 136–44). In the case of trauma, I add three more functions. First, feedback helps the listeners and participants of a collaborative sermon identify the stages of their trauma-healing process, whether naming trauma or meaning-making after a traumatic event. Second, feedback invites the congregation to achieve the very purpose of preaching in-between: community care and healing of collective trauma. Third, feedback allows the congregation to participate in the larger conversation about collective trauma and the fight for justice (Gunawan 2023, pp. 216–17).

In the case of feedback on the proposed model of collaborative preaching for collective trauma healing, I suggest that feedback be divided into two types: feedback from listeners and feedback from participants in the conversational preaching group. Listeners’ feedback focuses on the sermon’s content and form, the sermon’s flow or sequence, and the sermon’s connection to the worship liturgy. Feedback focused on the content and form of the sermon has two purposes: to ensure the impact of the gospel and to generate new insights for future topics that will support the trauma-healing process. Feedback related to the flow of the sermon and the connection of the sermon to the worship liturgy serves three functions: it helps preachers see if the sermon meets their expectations; it allows them to assess if the entire worship liturgy has fulfilled its role in communicating the gospel for healing; and it makes it possible to see if the spirit of gotong-royong and musyawarah-mufakat has been integrated into the entire worship service. Feedback can be given through written forms or in roundtable conversations after the worship.

Feedback from the preaching group members focuses on how conversational preaching assists participants from the beginning to the end of the process. In addition to determining where participants are in the trauma-healing process, the function of this feedback is to reveal the next steps in the collaborative conversation process. In addition, participant feedback reveals this model’s strengths and weaknesses as participants can express their views about its efficacy for achieving a safe and healing church community (Gunawan 2023, pp. 263–64).

6. Conclusions

James Nieman and Thomas Rogers address the issue of displacement in cross-cultural preaching. They challenge the preacher in the North American context to recognize the needs of the listener, especially those of immigrants who long for home or people living with trauma. Feelings of powerlessness, meaninglessness, normlessness, social isolation, rejection, and grief are the feelings of displacement that may be present in the hearts of the listeners in the pews. Perhaps there are people who long to return home to a place where they feel they belong and where they are accepted for who they are. Therefore, preaching is a place for them to travel through the journey of hardship to reach their destination (Nieman and Rogers 2001, pp. 90–91). Nieman and Rogers advocate that preachers build a community that connects congregants to others through special occasions (Nieman and Rogers 2001, p. 97).

Collaborative preaching can model the missional challenge identified by Nieman and Rogers: it can become a place for displaced people longing for home. This model is not just a group of people preparing sermons; it is about creating a safe place to unite God, self, and the world’s voices, thoughts, and life experiences. As a collective trauma community, Indonesia has a wealth of local traditions—gotong-royong and musyawarah-mufakat, for example—which reflect the sort of community values that align with collaborative preaching: mutuality, solidarity, trust, and ownership. With these values, the collaborative preaching model provides a space for expressing grief and recovery through sharing stories and even rediscovering the bonds of communality that were once destroyed by collective trauma.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The term “narrative fracture” comes from Kimberly Wagner, an assistant professor of preaching at Princeton Theological Seminary. In her book Fractured Ground: Preaching in the Wake of Mass Trauma, she indicates that trauma causes people to lose the coherence of a logically fitting and meaningful narrative. Narratives become bits and pieces of stories that do not make sense. However, she believes that even if narratives are fragmented, they can still be parts ready to be reconstructed. Such a narrative has the potential to bring about transformation in the trauma-healing process. See (Wagner 2023, pp. 51–53, Kindle). |

| 2 | There were 1217 victims killed, 91 people injured, and 31 people who disappeared when riots occurred in Jakarta from 12 May –20 June 1998. |

| 3 | The term “pribumi” refers to native or indigenous Indonesians. A problem arises when translating native or indigenous Indonesians to indicate the original Indonesian inhabitants. According to historical records, the remains of prehistoric human beings named Homo Modjokertoensis, Homo Soloensis, and Homo Wajakensis were unearthed in the region of Java. However, historians have deduced that Indonesian history did not begin with these pre-historical humans. The inhabitants, named pribumi, were migrants from Asia thousands of years ago (Suryadinata 2005). The first migrants were a dark-colored race of slight build. Around 3000 BCE, the second drive of migrants originated from the Polynesian–Malay category, perhaps setting out from South China. They entered Indonesian territory and drove the people who came before them into the woods. Then, about 300–200 BCE, the secondcomers were driven away by migrants from the Northern part of Indochina. These were of the Deutero-Malayan race (Darmaputera 1988). This historical account shows that pribumi Indonesians were also immigrants, just like the ethnic Chinese, but only at different times and in various waves of immigration. I prefer to use “pribumi” to refer to the native/indigenous Indonesian. The sociological and political term is used to distinguish them from the ethnic Chinese in Indonesia. |

| 4 | Ester Indahyani Jusuf et al. point to the report from the Joint Teams for Fact-Finders (Tim Gabungan Pencari Fakta) that shows the victims of mass rapes with the ages of the victims, the type of sexual violence experienced by the victims, the chronology, the place of the events, and the information sources. |

| 5 | Setiono explains how the Dutch colonists targeted the Chinese as scapegoats for economic–political advantage. From the beginning of the Dutch colonization of Indonesia, they classified the population into three groups: the first group of European/Westerners included Indo-Europeans (descendants of mixed marriages between Europeans and Asians); the second was the “Foreign Orientals”, comprising ethnic Chinese, Arabs, and other Asians: the third was the “Inlanders” (the native people) also named Bumiputera. Laws and regulations for these groups were written in several different books, and various court proceedings and judgments were followed in other courts. Only in matters of commerce were the ethnic Chinese ruled under Dutch Commercial Law. However, if crimes occurred in trade matters, the ethnic Chinese were treated as having Inlander status. If there were problems with competition with Chinese traders, the Dutch would drive the pribumi to fight the ethnic Chinese and spread negative views among the pribumi group. |

| 6 | Jeffry Alexander and Neil Smelser believe that cultural trauma is intentionally created. Both of them argue that the traumatic event experienced by an individual or collective is not necessarily cultural trauma, and the process of transforming the event into cultural trauma is artistic work. The process causes the collective members to feel victimized by the event, which leaves painful memories and changes their collective identity. Alexander identifies various social processes, claiming that an event is traumatic through performative actions, which establishes trauma as a new master narrative. The narrative should present the nature of the pain, the relationship of trauma victims to the broader audience, and the attribution of responsibility. |

| 7 | Ariel Haryanto suggests that there are three elements involved in state terrorism: (1) fear of violence by state officials; (2) violence against a minority group by those who consider themselves to be a majority; and (3) violence in a public space so that the message of the incident can spread quickly. |