Pathways to Flourishing: The Roles of Self- and Divine Forgiveness in Mitigating the Adverse Effects of Stress and Substance Use among Adults in Trinidad and Tobago

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Flourishing and Stress

1.2. Self-Forgiveness

1.3. Divine Forgiveness

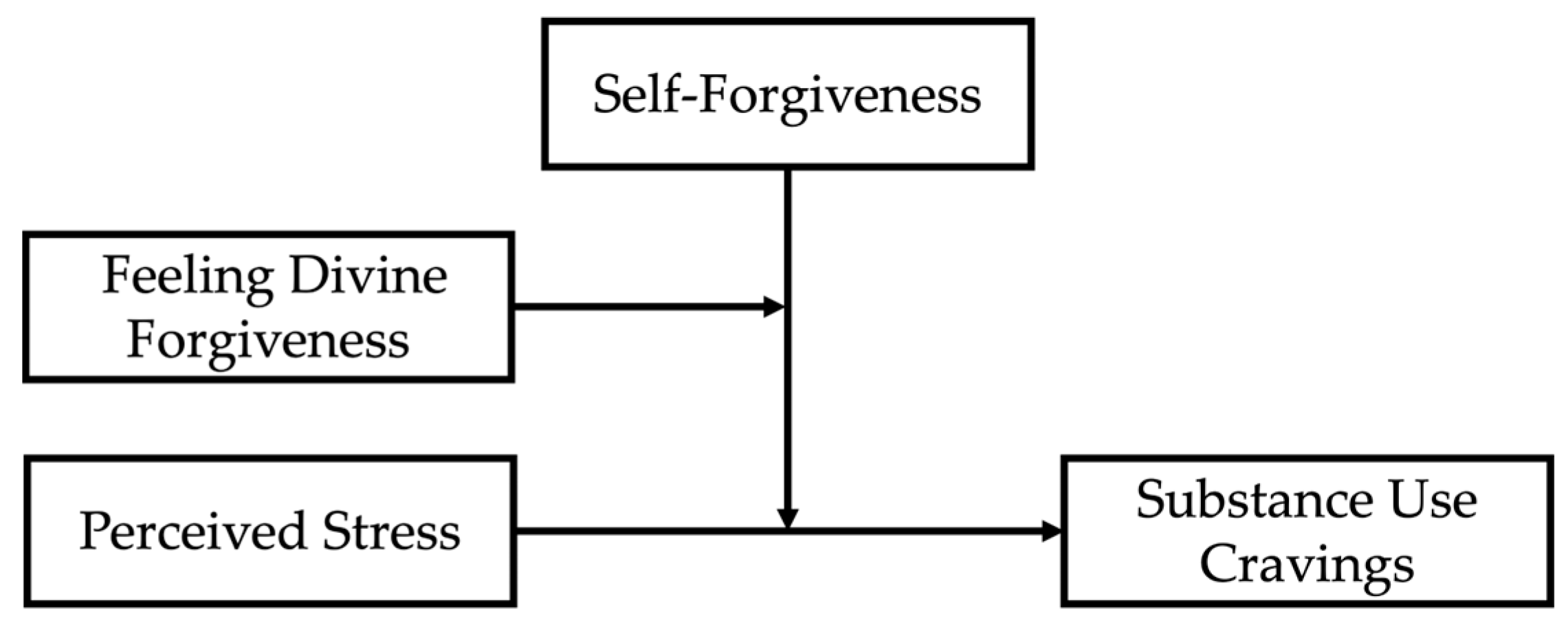

1.4. Present Study

2. Results

2.1. Demographic Variables

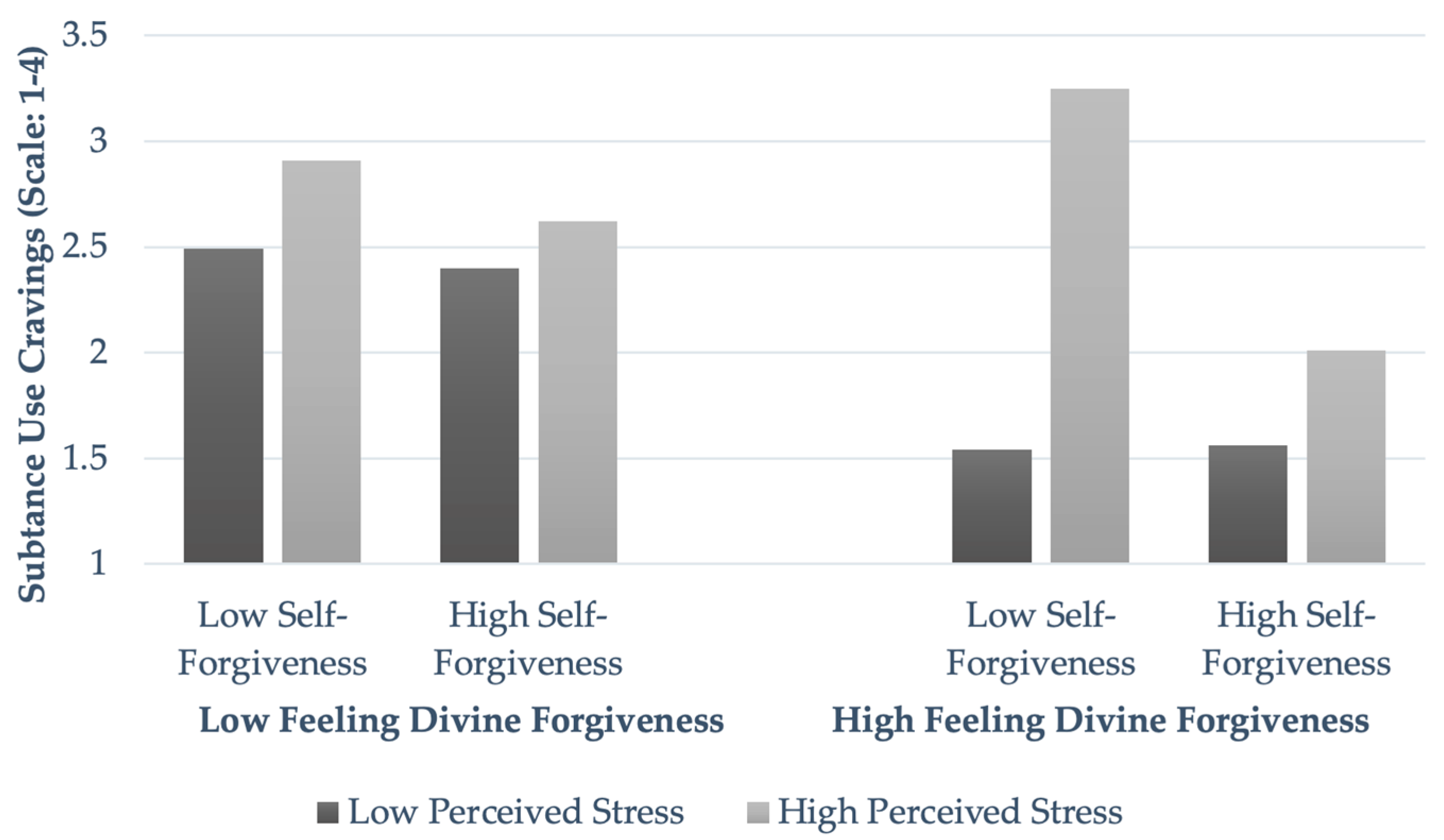

2.2. Moderated Moderation

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Perceived Stress

3.2.2. Self-Forgiveness

3.2.3. Divine Forgiveness

3.2.4. Substance Use Cravings

3.2.5. General Religiousness and Spirituality

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdollahi, Abbas, Simin Hosseinian, Hassan Sadeghi, and Tengku A. Hamid. 2018. Perceived Stress as a Mediator between Social Support, Religiosity, and Flourishing among Older Adults. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 40: 80–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenor, Christine, Norma Conner, and Karen Aroian. 2017. Flourishing: An Evolutionary Concept Analysis. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 38: 915–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akl, Marianné, and Etienne Mullet. 2010. Forgivingness: Relationships With Conceptualizations of Divine Forgiveness and Childhood Memories. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 20: 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakracheva, Margarita. 2020. The Meanings Ascribed to Happiness, Life Satisfaction and Flourishing. Psychology 11: 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, Tracy A., Tyler J. VanderWeele, Stephanie D. Doan-Soares, Katelyn N. G. Long, Betty R. Ferrell, George Fitchett, Harold G. Koenig, Paul A. Bain, Christina Puchalski, Karen E. Steinhauser, and et al. 2022. Spirituality in Serious Illness and Health. JAMA 328: 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassett, Rodney L., Evan Carrier, Katherine Charleson, Na R. Pak, Rachael Schwingel, Alexandra Majors, Meredith Pitre, Andrea Sundlof-Stoller, and Carol Bloser. 2016. Is It Really More Blessed to Give than to Receive? A Consideration of Forgiveness and Perceived Health. Journal of Psychology and Theology 44: 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Christopher M., Don E. Davis, Brandon J. Griffin, Jeffrey S. Ashby, and Kenneth G. Rice. 2017. The Promotion of Self-Forgiveness, Responsibility, and Willingness to Make Reparations through a Workbook Intervention. The Journal of Positive Psychology 12: 571–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bem, Jemima R., Peter Strelan, and Michael Proeve. 2021. Roads Less Travelled to Self-Forgiveness: Can Psychological Flexibility Overcome Chronic Guilt/Shame to Achieve Genuine Self-Forgiveness? Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 21: 203–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolier, Linda, Merel Haverman, Gerben J. Westerhof, Heleen Riper, Filip Smit, and Ernst Bohlmeijer. 2013. Positive Psychology Interventions: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Studies. BMC Public Health 13: 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamizo-Nieto, María T., Christiane Arrivillaga, Lourdes Rey, and Natalio Extremera. 2021. The Role of Emotional Intelligence, the Teacher-Student Relationship, and Flourishing on Academic Performance in Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Study. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 695067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charzyńska, Edyta, Ewa Gruszczyńska, and Irena Heszen. 2018. Forgiveness and Gratitude Trajectories Among Persons Undergoing Alcohol Addiction Therapy. Addiction Research & Theory 26: 282–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Ying, Dorota Weziak-Bialowolska, Matthew T. Lee, Piotr Bialowolski, Eileen McNeely, and Tyler J. VanderWeele. 2022. Longitudinal Associations between Domains of Flourishing. Scientific Reports 12: 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Eunji, Lynne E. Baker-Ward, Sophia K. Smith, Raymond C. Barfield, and Sharron L. Docherty. 2021. Human Flourishing in Adolescents with Cancer: Experiences of Pediatric Oncology Health Care Professionals. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 59: 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, Steve, Cynthia English, Byron R. Johnson, Zacc Ritter, and Tyler J. VanderWeele. 2021. Global Flourishing Study Questionnaire Development Report. Washington, DC: Gallup Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Datu, Jesus A. D., Charlie E. Labarda, and Maria G. C. Salanga. 2020. Flourishing Is Associated with Achievement Goal Orientations and Academic Delay of Gratification in a Collectivist Context. Journal of Happiness Studies 21: 1171–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denovan, Andrew, and Ann Macaskill. 2017. Stress and Subjective Well-Being Among First Year UK Undergraduate Students. Journal of Happiness Studies 18: 505–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditzen, Beate, and Markus Heinrichs. 2007. Psychobiologische Mechanismen Sozialer Unterstützung. Zeitschrift Für Gesundheitspsychologie 15: 143–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreer, Benjamin. 2021. The Significance of Mentor–Mentee Relationship Quality for Student Teachers’ Well-Being and Flourishing during Practical Field Experiences: A Longitudinal Analysis. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education 10: 101–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, Shanta R., Vincent J. Felitti, Maxia Dong, Wayne H. Giles, and Robert F. Anda. 2003. The Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences on Health Problems: Evidence from Four Birth Cohorts Dating Back to 1900. Preventive Medicine 37: 268–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, Eve, and Emiliana Simon-Thomas. 2021. Teaching the Science of Human Flourishing, Unlocking Connection, Positivity, and Resilience for the Greater Good. Global Advances in Health and Medicine 10: 216495612110230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekşi, Halil, İbrahim Demirci, İbrahim Albayrak, and Füsun Ekşi. 2022. The Predictive Roles of Character Strengths and Personality Traits on Flourishing. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies 9: 353–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, Frank D. 2022. Towards a Psychology of Divine Forgiveness. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 14: 451–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, Frank D., and Ross W. May. 2019. Self-Forgiveness and Well-Being: Does Divine Forgiveness Matter? The Journal of Positive Psychology 14: 854–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, Frank D., and Ross W. May. 2020. Divine, Interpersonal and Self-Forgiveness: Independently Related to Depressive Symptoms. The Journal of Positive Psychology 15: 448–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, Frank D., and Ross W. May. 2021. Divine Forgiveness Protects against Psychological Distress Following a Natural Disaster Attributed to God. The Journal of Positive Psychology 16: 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Mickie L., and Julie J. Exline. 2010. Moving Toward Self-Forgiveness: Removing Barriers Related to Shame, Guilt, and Regret. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 4: 548–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, Susan. 2008. The Case for Positive Emotions in the Stress Process. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 21: 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, Susan, and Judith T. Moskowitz. 2000. Stress, Positive Emotion, and Coping. Current Directions in Psychological Science 9: 115–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, Maarit. 2024. Trinidad and Tobago. In The Oxford Handbook of Caribbean Religions. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 258–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, Barbara L. 2004. The Broaden–and–Build Theory of Positive Emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 359: 1367–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, Barbara L., Roberta A. Mancuso, Christine Branigan, and Michele M. Tugade. 2000. The Undoing Effect of Positive Emotions. Motivation and Emotion 24: 237–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson-Larsson, Ulla, Eva Brink, Gunne Grankvist, Ingibjörg H. Jonsdottir, and Pia Alsen. 2015. The Single-Item Measure of Stress Symptoms after Myocardial Infarction and Its Association with Fatigue. Open Journal of Nursing 5: 345–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fuller-Thomson, Esme, and Keri J. West. 2019. Flourishing despite a Cancer Diagnosis: Factors Associated with Complete Mental Health in a Nationally-Representative Sample of Cancer Patients Aged 50 Years and Older. Aging & Mental Health 23: 1263–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloria, Christian T., Kathryn E. Faulk, and Mary A. Steinhardt. 2013. Positive Affectivity Predicts Successful and Unsuccessful Adaptation to Stress. Motivation and Emotion 37: 185–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Kirsten L., Jessica L. Morse, Maeve B. O’Donnell, and Michael F. Steger. 2017. Repairing Meaning, Resolving Rumination, and Moving toward Self-Forgiveness. In Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness. Edited by Lydia Woodyatt, Everett L. Worthington, Jr., Michael Wenzel and Brandon J. Griffin. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, Brandon J. 2016. Development of a Two-Factor Self-Forgiveness Scale. Master’s dissertation, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, Brandon J., Caroline R. Lavelock, and Everett L. Worthington. 2014. On Earth as It Is in Heaven: Healing through Forgiveness. Journal of Psychology and Theology 42: 252–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Julie H., and Frank D. Fincham. 2005. Self–Forgiveness: The Stepchild of Forgiveness Research. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 24: 621–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Julie H., and Frank D. Fincham. 2008. The Temporal Course of Self–Forgiveness. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 27: 174–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2017. Partial, Conditional, and Moderated Moderated Mediation: Quantification, Inference, and Interpretation. Communication Monographs 85: 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, Jameson K., Jon R. Webb, and Elizabeth L. Jeglic. 2012. Forgiveness as a Moderator of the Association between Anger Expression and Suicidal Behaviour. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 15: 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Henry C. Y., and Ying C. Chan. 2022. Flourishing in the Workplace: A One-Year Prospective Study on the Effects of Perceived Organizational Support and Psychological Capital. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliman, Andrew J., Daniel Waldeck, Bethany Jay, Summayah Murphy, Emily Atkinson, Rebecca J. Collie, and Andrew Martin. 2021. Adaptability and Social Support: Examining Links With Psychological Wellbeing Among UK Students and Non-Students. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 636520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, Cheryl L., Eddie M. Clark, Katrina J. Debnam, and Debnam L. Roth. 2014. Religion and Health in African Americans: The Role of Religious Coping. American Journal of Health Behavior 38: 190–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, Felicia A., and Timothy T. C. So. 2013. Flourishing Across Europe: Application of a New Conceptual Framework for Defining Well-Being. Social Indicators Research 110: 837–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inagaki, Tristen K., and Naomi I. Eisenberger. 2016. Giving Support to Others Reduces Sympathetic Nervous System-related Responses to Stress. Psychophysiology 53: 427–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Kathryn A., Jordan W. Moon, Tyler J. VanderWeele, Sarah Schnitker, and Byron R. Johnson. 2023. Assessing Religion and Spirituality in a Cross-Cultural Sample: Development of Religion and Spirituality Items for the Global Flourishing Study. Religion, Brain & Behavior, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, Rupa, Elizabeth J. D’Amico, David J. Klein, Anthony Rodriguez, Eric R. Pedersen, and Joan S. Tucker. 2024. In Flux: Associations of Substance Use with Instability in Housing, Employment, and Income among Young Adults Experiencing Homelessness. PLoS ONE 19: e0303439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, Corey L. M. 2002. The Mental Health Continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing in Life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 43: 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, Corey L. M. 2009. The Black–White Paradox in Health: Flourishing in the Face of Social Inequality and Discrimination. Journal of Personality 77: 1677–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, Corey L. M., and Eduardo J. Simoes. 2012. To Flourish or Not: Positive Mental Health and All-Cause Mortality. American Journal of Public Health 102: 2164–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal. 2017. Religious Involvement and Self-Forgiveness. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 20: 128–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal, and Christopher G. Ellison. 2003. Forgiveness by God, Forgiveness of Others, and Psychological Well-Being in Late Life. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42: 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Xinxin, Kazuma Ishimatsu, Midori Sotoyama, and Kazuyuki Iwakiri. 2016. Positive Emotion Inducement Modulates Cardiovascular Responses Caused by Mental Work. Journal of Physiological Anthropology 35: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, John M., and David N. Dixon. 2012. Perceived Forgiveness from God and Self-Forgiveness. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 31: 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, Michael E., and Everett L. Worthington, Jr. 1999. “Religion and the Forgiving Personality. Journal of Personality 67: 1141–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Carol, Frank P. Deane, Geoffrey C. B. Lyons, and Peter J. Kelly. 2013. Factor Analysis and Validity of a Short Six-Item Version of the Desires for Alcohol Questionnaire. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 44: 557–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research. 1999. Kalamazoo: Fetzer Institute.

- Okely, Judith A., Alexander Weiss, and Catharine R. Gale. 2017. The Interaction between Stress and Positive Affect in Predicting Mortality. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 100: 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, Anthony D., C. S. Bergeman, Toni L. Bisconti, and Kimberly A. Wallace. 2006. Psychological Resilience, Positive Emotions, and Successful Adaptation to Stress in Later Life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 91: 730–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrok, Barbara G. 1989. Alcoholics Anonymous: The Story of How Many Thousands of Men and Women Have Recovered from Alcoholism. JAMA 261: 3315–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L. 2010. Making Sense of the Meaning Literature: An Integrative Review of Meaning Making and Its Effects on Adjustment to Stressful Life Events. Psychological Bulletin 136: 257–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Zachary R., Robert L. Gabrys, Rebecca K. Prowse, Alfonso B. Abizaid, Kim G. C. Hellemans, and Robyn J. McQuaid. 2021. The Influence of COVID-19 on Stress, Substance Use, and Mental Health Among Postsecondary Students. Emerging Adulthood 9: 516–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peifer, Corinna, André Schulz, Hartmut Schächinger, Nicola Baumann, and Conny H. Antoni. 2014. The Relation of Flow-Experience and Physiological Arousal under Stress—Can u Shape It? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 53: 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicane, Michael J., Madison E. Quinn, and Jeffrey A. Ciesla. 2023. Transgender and Gender-Diverse Minority Stress and Substance Use Frequency and Problems: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transgender Health. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2024. Religion and Public Life. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Prati, Gabriele, Luca Pietrantoni, and Elvira Cicognani. 2010. Self-Efficacy Moderates the Relationship between Stress Appraisal and Quality of Life among Rescue Workers. Anxiety, Stress & Coping 23: 463–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rule, Andrew, Cody Abbey, Huan Wang, Scott Rozelle, and Manpreet K. Singh. 2024. Measurement of Flourishing: A Scoping Review. Frontiers in Psychology 15: 1293943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, Michael, Everett L. Worthington, Jr., Joshua N. Hook, and Kathryn L. Campana. 2011. Forgiveness and the Bottle: Promoting Self-Forgiveness in Individuals Who Abuse Alcohol. Journal of Addictive Diseases 30: 382–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, Norbert, Willi Neumann, and Roman Oppermann. 2000. Stress, Burnout and Locus of Control in German Nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies 37: 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer, Ralf, and Suhair Hallum. 2008. Perceived Teacher Self-Efficacy as a Predictor of Job Stress and Burnout: Mediation Analyses. Applied Psychology 57: 152–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, Martin E. P. 2011. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, Jacqueline, and Samuel Shafe. 2016. Mental Health in the Caribbean. In Aribbean Psychology: Indigenous Contributions to a Global Discipline. Edited by Jaipaul L. Roopnarine and Deborah Chadee. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 305–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, Rajita. 2008. Chronic Stress, Drug Use, and Vulnerability to Addiction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1141: 105–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalski-Bednarz, Sebastian B., and Loren L. Toussaint. 2024. A Relational Model of State of Forgiveness and Spirituality and Their Influence on Well-Being: A Two-Wave Longitudinal Study of Women with a Sexual Assault History. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalski-Bednarz, Sebastian B., Loren L. Toussaint, Karol Konaszewski, and Janusz Surzykiewicz. 2024a. Beyond HIV Shame: The Role of Self-Forgiveness and Acceptance in Living with HIV. AIDS Care, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalski-Bednarz, Sebastian B., Loren L. Toussaint, Karol Konaszewski, and Janusz Surzykiewicz. 2024b. Forgiveness in Young American Adults and Its Pathways to Distress by Health, Outlook, Spirituality, Aggression, and Social Support. Health Psychology Report, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, Erinn C., Travis Sztainert, Nathalie R. Gillen, Julie Caouette, and Michael J. A. Wohl. 2012. The Problem with Self-Forgiveness: Forgiving the Self Deters Readiness to Change Among Gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies 28: 337–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steps, Twelve. 1981. Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services. [Google Scholar]

- Strelan, Peter. 2017. The Measurement of Dispositional Self-Forgiveness. In Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness. Edited by Lydia Woodyatt, Everett L. Worthington, Jr., Michael Wenzel and Brandon J. Griffin. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons, Xavier, and Tyler VanderWeele. 2024. Aristotelian Flourishing and Contemporary Philosophical Theories of Wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies 25: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Laura Y., C. R. Snyder, Lesa Hoffman, Scott T. Michael, Heather N. Rasmussen, Laura S. Billings, Laura Heinze, Jason E. Neufeld, Hal S. Shorey, Jessica C. Roberts, and et al. 2005. Dispositional Forgiveness of Self, Others, and Situations. Journal of Personality 73: 313–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, Loren. 2022. Forgiveness and Flourishing. Spiritual Care 11: 313–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, Loren L., David R. Williams, Marc A. Musick, and Susan A. Everson. 2001. Forgiveness and Health: Age Differences in a U.S. Probability Sample. Journal of Adult Development 8: 249–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, Loren L., Jon R. Webb, and Jameson K. Hirsch. 2017. Self-Forgiveness and Health: A Stress-and-Coping Model. In Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness. Edited by Lydia Woodyatt, Everett L. Worthington, Jr., Michael Wenzel and Brandon J. Griffin. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugade, Michele M., and Barbara L. Fredrickson. 2004. Resilient Individuals Use Positive Emotions to Bounce Back From Negative Emotional Experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 86: 320–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twenge, Jean M., Ryne A. Sherman, Julie J. Exline, and Joshua B. Grubbs. 2016. Declines in American Adults’ Religious Participation and Beliefs, 1972–2014. SAGE Open 6: 215824401663813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, Tyler J. 2017a. On the Promotion of Human Flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114: 8148–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanderWeele, Tyler J. 2017b. Religious Communities and Human Flourishing. Current Directions in Psychological Science 26: 476–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, Christian E. 2014. The Regulatory Power of Positive Emotions in Stress: A Temporal-Functional Approach. In The Resilience Handbook: Approaches to Stress and Trauma. Edited by Martha Kent, Mary C. C. Davis and John W. Reich. New York: Routledge, pp. 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, Jon R. 2021. Understanding Forgiveness and Addiction: Theory, Research, and Clinical Application. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, Jon R., and Bridget R. Jeter. 2015. Forgiveness and Health: Scientific Evidence and Theories Relating Forgiveness to Better Health. In Forgiveness and Problematic Substance. Edited by Loren L. Toussaint, Everett L. Worthington, Jr. and David R. Williams. New York: Springer, pp. 139–54. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, Jon R., and Loren L. Toussaint. 2018. Self-Forgiveness as a Critical Factor in Addiction and Recovery: A 12-Step Model Perspective. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 36: 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, Jon R., David Bumgarner, Elizabeth Conway-Williams, Trever Dangel, and Benjamin B. Hall. 2017a. A Consensus Definition of Self-Forgiveness: Implications for assessment and treatment. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 4: 216–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, Jon R., Elizabeth A. R. Robinson, and Kirk J. Brower. 2009. Forgiveness and Mental Health Among People Entering Outpatient Treatment With Alcohol Problems. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 27: 368–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, Jon R., Elizabeth A. R. Robinson, and Kirk J. Brower. 2011. Mental Health, Not Social Support, Mediates the Forgiveness-Alcohol Outcome Relationship. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 25: 462–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, Jon R., Elizabeth A. R. Robinson, Kirk J. Brower, and Robert A. Zucker. 2006. Forgiveness and Alcohol Problems Among People Entering Substance Abuse Treatment. Journal of Addictive Diseases 25: 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, Jon R., Jameson K. Hirsch, and Loren L. Toussaint. 2017b. Self-Forgiveness and Pursuit of the Sacred: The Role of Pastoral-Related Care. In Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness. Edited by Edited by Lydia Woodyatt, Everett L. Worthington, Jr., Michael Wenzel and Brandon J. Griffin. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weziak-Bialowolska, Dorota, Piotr Bialowolski, Matthew T. Lee, Ying Chen, Tyler J. VanderWeele, and Eileen McNeely. 2021. Psychometric Properties of Flourishing Scales From a Comprehensive Well-Being Assessment. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 652209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, Aaron. 2020. Gender Differences in the Epidemiology of Alcohol Use and Related Harms in the United States. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews 40: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohl, Michael J. A., Melissa M. Salmon, Samantha J. Hollingshead, Sara K. Lidstone, and Nassim Tabri. 2017. The Dark Side of Self-Forgiveness: Forgiving the Self Can Impede Change for Ongoing, Harmful Behavior. In Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness. Edited by Edited by Lydia Woodyatt, Everett L. Worthington, Jr., Michael Wenzel and Brandon J. Griffin. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 147–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodyatt, Lydia, and Michael Wenzel. 2013. Self-Forgiveness and Restoration of an Offender Following an Interpersonal Transgression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 32: 225–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, Everett L., Jr. 2006. Forgiveness and Reconciliation: Theory and Application. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | M (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived Stress | 4.54 (1.95) | −0.6 | −0.93 | -- | |||

| 2. Self-Forgiveness | 4.46 (0.89) | 0.36 | 0.6 | −0.31 *** | -- | ||

| 3. Feeling Divine Forgiveness | 2.62 (0.61) | −1.43 | 1.26 | −0.02 | 0.2 *** | -- | |

| 4. Substance Use Cravings | 2.41 (1.66) | 0.97 | −0.38 | 0.37 *** | −0.3 *** | −0.12 *** | -- |

| Religiousness | 3.31 (0.97) | −0.25 | −0.2 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.31 *** | 0.02 |

| Spirituality | 3.37 (0.95) | −0.16 | −0.31 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.24 *** | 0.04 |

| Variable | B | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 13.67 *** | 2.79 | 4.9 | 8.2 | 19.15 |

| Perceived Stress (X) | −1.86 *** | 0.52 | −3.59 | −2.88 | −0.84 |

| Self-Forgiveness (W) | −2.33 *** | 0.62 | −3.77 | −3.54 | −1.11 |

| X × W | 0.42 *** | 0.12 | 3.51 | 0.18 | 0.65 |

| Feeling Divine Forgiveness (Z) | −4.51 *** | 1.01 | −4.48 | −6.49 | −2.54 |

| X × Z | 0.9 *** | 0.19 | 4.71 | 0.53 | 1.28 |

| W × Z | 0.84 *** | 0.22 | 3.79 | 0.4 | 1.27 |

| X × W × Z | −0.18 *** | 0.04 | −4.14 | −0.26 | −0.09 |

| Gender | −0.54 *** | 0.10 | −5.48 | −0.74 | −0.35 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.32 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Race | 0.11 ** | 0.04 | 2.99 | 0.04 | 0.18 |

| Education | 0.22 *** | 0.05 | 4.83 | 0.13 | 0.31 |

| Income | −0.13 *** | 0.03 | −4.60 | −0.19 | −0.08 |

| Religiousness | −0.05 | 0.08 | −0.70 | −0.20 | 0.10 |

| Spirituality | 0.12 | 0.07 | 1.57 | −0.03 | 0.26 |

| Self-Forgiveness | Feeling Divine Forgiveness | B | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Low | 0.16 *** | 0.05 | 3.39 | 0.07 | 0.25 |

| Low | High | 0.4 *** | 0.04 | 9.06 | 0.32 | 0.49 |

| High | Low | 0.26 *** | 0.06 | 4.58 | 0.15 | 0.36 |

| High | High | 0.2 *** | 0.04 | 5.58 | 0.13 | 0.28 |

| Variable | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Men | 36% |

| Women | 62% |

| Other | 2% |

| Race | |

| Afro-Trinidadian | 46% |

| Chinese-Trinidadian | 1% |

| Mixed | 34% |

| Indian-Trinidadian | 6% |

| Caucasian-Trinidadian | 8% |

| Other | 5% |

| Education | |

| Less than High School | 5% |

| High School | 41% |

| Two-Year Degree | 12% |

| College/University | 32% |

| Beyond Four Years | 10% |

| Annual Income (USD) | |

| Less than USD 30,000 | 41% |

| USD 30,001 to USD 60,000 | 20% |

| USD 60,001 to USD 90,000 | 13% |

| USD 90,001 to USD 120,000 | 9% |

| USD 120,001 to USD 150,000 | 5% |

| USD 150,001 to USD 180,000 | 5% |

| More than USD 180,000 | 7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skalski-Bednarz, S.B.; Webb, J.R.; Wilson, C.M.; Toussaint, L.L.; Surzykiewicz, J.; Reid, S.D.; Williams, D.R.; Worthington, E.L., Jr. Pathways to Flourishing: The Roles of Self- and Divine Forgiveness in Mitigating the Adverse Effects of Stress and Substance Use among Adults in Trinidad and Tobago. Religions 2024, 15, 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091060

Skalski-Bednarz SB, Webb JR, Wilson CM, Toussaint LL, Surzykiewicz J, Reid SD, Williams DR, Worthington EL Jr. Pathways to Flourishing: The Roles of Self- and Divine Forgiveness in Mitigating the Adverse Effects of Stress and Substance Use among Adults in Trinidad and Tobago. Religions. 2024; 15(9):1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091060

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkalski-Bednarz, Sebastian Binyamin, Jon R. Webb, Colwick M. Wilson, Loren L. Toussaint, Janusz Surzykiewicz, Sandra D. Reid, David R. Williams, and Everett L. Worthington, Jr. 2024. "Pathways to Flourishing: The Roles of Self- and Divine Forgiveness in Mitigating the Adverse Effects of Stress and Substance Use among Adults in Trinidad and Tobago" Religions 15, no. 9: 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091060

APA StyleSkalski-Bednarz, S. B., Webb, J. R., Wilson, C. M., Toussaint, L. L., Surzykiewicz, J., Reid, S. D., Williams, D. R., & Worthington, E. L., Jr. (2024). Pathways to Flourishing: The Roles of Self- and Divine Forgiveness in Mitigating the Adverse Effects of Stress and Substance Use among Adults in Trinidad and Tobago. Religions, 15(9), 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091060