Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic produced substantial and sudden changes in the reality of everyday life and in the collective construction of meaning. Questions arose: how should events occurring within an empty reality be broadcast? And, even before that, what structure is needed to make these events transmissible and interpretable, coping with the fact that they happen within a framework of lack of relationships and absolute silence? By analysing the worldwide live recording broadcast on 27 March 2020, commonly known as “the pope alone in Saint Peter’s Square during the pandemic”, this paper identifies a series of communicative solutions adopted by television. These range from making visible what should be hidden, to variously filling the emptiness by modifying the spatial colocation of the event, to an even more extreme solution, in which the emptiness remains as it is, and a rare semantic case occurs in which the sign coincides with its meaning. The latter is what I label the “pope of the rain” solution.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken the world into a completely new context. The challenge of living confined lives at home has erased the usual world of everyday life, one in which actions and meanings are inscribed in an alphabet of comprehensibility accessible to and shared with each other (Schutz 1962).

This condition, peculiar to the stranger (Schutz 1976), is now generalized: during the pandemic, each person found himself or herself living as a stranger to each other. For everyone, social life will not continue to be what it has always been (Schutz 1976, p. 96. Italics mine). What happens out there? Does the world continue if no one is there to participate? The answer lies precisely in sharing the experience of all being strangers, in constructing the communication that a new world without people, however unexperienced so far, is possible.

The television images that will be analysed here move in this direction and find various ways of saying so. For example, by communicating a continuing ritual that recalls the myths of collectivity, upon which community is considered formed (Durkheim 1961, p. 408 ff.), or, more simply, respecting the performance of expected rituals; or perhaps by emphasizing, on the one hand, the absence of people, and transforming, on the other hand, the situation into a collective “armchair pilgrimage” (Dayan et al. 1986). These communicative solutions apply to all the images that we will be exploring here, except for the first one, in which the negative and definitive answer is made visible (collective death is present), and the last one, which contains at its root an interpretive ambivalence: perhaps a world without anybody already exists. We can perceive this precisely because we are in the condition of the stranger who “discerns, frequently with a grievous clear-sightedness, the rising of a crisis” (Schutz 1976, p. 104).

2. Materials and Methods

In a previous analysis of the media narrative on Pope John Paul II, I labelled the pope the “man of the wind” (Guizzardi 2005). In this article, I promote the label “man of the rain” to refer to Pope Francis. To support this proposal, I analyse the worldwide live recording of one hour and five minutes in length that was released on 27 March 2020, and is commonly known as “the pope alone in Saint Peter’s Square during the pandemic”.

That afternoon, some nine minutes after the beginning of the live recording, the rain started to pour harder and harder on the city of Rome, and the celebration was held outside. However, these features are not enough to support the label I am proposing. It is not only that Pope Francis delivered his blessing in the rain. The rain, probably unexpected, the planned solitude, and the shape and development of the celebration have been given a deep meaning that has become one of the most powerful images of the pandemic. My goal is to bring to light the process through which this meaning has been constructed and to uncover its impact.

3. The Context

On 27 March 2020, Italy was in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. News about an unknown and very serious pandemic affecting China had begun circulating at the end of December 2019. As a consequence, a Chinese megacity with 12 million inhabitants was closed completely and immediately. On the evening of 20 February 2020, the pandemic had arrived in Italy, with news of the first hospitalisation in Codogno, a small town in the Lodi area of the Lombardy Region. The day after, news circulated about the first patient who died in Vò Euganeo, a small municipality in the Veneto region, whose inhabitants were immediately confined and separated from their surroundings by a strict sanitary cordon.

In a few hours, the virus brought death to large Lodi areas and the province of Bergamo. On 18 March, the death count was so high that it was not possible to deal with funerals and burials. It was decided to send a column of vehicles to transport the coffins from Bergamo to secret destinations where funeral functions could take place.

On the evening of 9 March, the State decreed a national lockdown, and people were forced to remain at home. This rule, followed by other measures of the same kind, remained in place until 18 May. After hesitations and uncertainties, on 10 May, the World Health Organization officially classified the situation as a pandemic.

In this scenario of forced isolation, people discovered that the means that should and could prevent contagion were not available. Faced with the sudden saturation of places in intensive therapies, the Italian Society of Anaesthesia, Analgesia, Resuscitation and Intensive Therapy (SIAARTI) proposed—although with deep regret—to automatically choose between patients to be saved and patients to let die (Lusardi and Tomelleri 2020; Bimbi 2021).

4. Fractures

According to De Rosa and Mannarini (2020), the topic of the “invisible other” semantically marked the pandemic. In fact, the lockdown caused by the invisible virus determined the practical invisibilisation of everyone, whereas urban contexts—buildings, spaces, and architectures—became visible. Moreover, a semantic strain emerged between contrasting elements: now empty cities versus ordinarily crowded squares, current silence versus usual din, and the present absolute lack of relationships versus the normal physical presence of others.

This was a second-level process, through which a comparison between the life before the pandemic, a time characterised by what was known, and the present time of the pandemic, unknown and uncharted, emerged. This process lay on a radical fracture of what Schutz (1962, p. 229) would call the epoch of the natural attitude: we suddenly perceived that the world and its objects may be different from how they appeared a moment before.

In fact, the situation caused by the virus (the “invisible other”) was collectively experienced as a deep trauma that made us realise that the pillars of the taken-for-granted world, which sustain the reality of everyday life, were shattered. As a consequence, life moved towards a totally new dimension, where objects, spaces and subjects remained the same, but their relationships did not.

Many things changed. The boundaries of a finite province of meaning broke, and the accent of reality shifted from one reality to another (Schutz 1962, p. 231). However, this new reality was unknown to individuals and lacked a collective codification, so it was not available to those who wanted to enter or had to face it. These changes were not just about subjects like veterans or strangers who shift from one reality to another in everyday life, both known in their constitutive features to those who inhabit them. It affected everyone at the same time, with two relevant notes. The first is that we could not assume that our taken-for-granted reality corresponded to that held by the people we were interacting with. The second and most important note is that we could expressively cultivate doubts about the correspondence between the taken-for-granted reality we were trying to construct and that of others.

5. Time, a Radical Disruption

One of the main changes was related to the perception of time and temporality. A radical disruption was introduced between before and after the appearance of the invisible enemy on the scene. It was a rupture paired with the discontinuity between the “available system of relevance” of the previous situation and an emergent new one, unexplored and therefore largely still to be built.

In the short term, we saw a possible solution in comforting each other and suggesting mutual trust in a positive outcome of the new and unprecedented process of reality building in which we happened to be placed.1 Another relief path relied on comparison with the past, that is, with the experience that, in spite of everything, was (still) available. From this comparison grew the highly emotional perception of the unnaturalness of the current condition, of the here and now in which we were located. The attempt to build a new and unprecedented present was situated precisely within the radical discontinuity between a “vivid” present and a “vividly recalled” past.

However, the “vivid present” was substantially made up of images, since face-to-face relationships in daily life evaporated. Images were communicated by the media, with television being one of the main channels. Media taught us “how the world out there was”, if and how it was still existing, and if and how it was being recomposed.

In the following analysis, I focus on images in order to interpret the one regarding the “pope alone in St. Peter’s Square”. The starting point is to understand the origin of its relevance, which is collectively attributed to its absolute non-naturalness, which goes hand in hand with the label by which it is summarised: complete solitude. I agree with these connotations, even if I intend to propose a more advanced interpretation.

6. A Gallery of Images

6.1. Bergamo, Night of 18 March 2020

The first image, in chronological order, portrays a column of military trucks carrying the coffins of those who died from COVID-19 in Bergamo and could not be buried in the city’s cemeteries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bergamo, night of 18 March 2020 (Photo Ansa.it).

The tragic nature of this image is revealed only by the information provided about the content and purpose of that “procession”. Only at that moment, given some characteristics that opposed this vision to consolidated expectations, did the image appear as unnatural: a procession of coffins in absolute solitude as opposed to a participatory funeral. No living people were accompanying the deceased, just a column of dead people accompanying other dead people. The action was conducted at night, while funerals are usually celebrated during the day. There was a lack of any rituality, which entailed the breaking of even the slightest collective convention. An empty city, filled with coffins, instead of streets crowded with the living.

To summarise the meaning of this image, even more could be said: emptiness filled by the non-living. Emptiness filled with references to signs (coffins) that indicated the presence of non-living people. Their presence was only affirmed by the objects contained in the trucks; they themselves were not visible. The virus was invisible, but entirely present. It was doubly hidden, thus multiplying its relevance.2

6.2. Liberation Day, Rome, 25 April 2020

The second image portrays the official ceremony held by the president of the Italian republic for National Liberation Day on 25 April (see Figure 2). Here, too, the non-naturalness of the situation is provided by a sense of solitude.

Figure 2.

National Liberation Day, Rome, 25 April 2020 (Photo Paolo Giandotti).

President Sergio Mattarella stood alone on the scene in a deserted city, without cars or people, without his entourage, without celebrations, and without any sign of the presence of the state (such as a parade with eminent representatives of the institutions). There were no sounds or noises and no people participating on either side of the street. The monument Altare della Patria (Altar of the Homeland) stood out as a second silent actor, confirming that the invisible virus made the cities visible in their pure objectivity.

Although the president seemed completely alone—different from what we were used to seeing on similar occasions and were therefore expecting—he was not truly alone. Even in solitude, he doubled himself: on one side, his individuality; on the other, his public role. In each of his doubled presences, he embodied a symbol: one different from the other. The first was the national community, indicated by signs confirming the ritual (albeit on a smaller scale). This ritual was performed by the few attending people, who were themselves symbols (the salute, the short blaring of trumpets). Then, there was the long meditative silence and the slow walk of the president climbing the steps to access the point where the ritual took place. Second, his presence symbolised a kind of generalised individuality. The gestures of putting on the protective mask as he walked through the official path of the ceremony, of removing it later during the formal ceremony, and of putting it back on at the end revealed the novelty: the president was behaving like anyone else at that time. We were all affected by the virus, including Sergio Mattarella. We, too, were therefore present in those images by proxy, as citizens as well as subjects living in that situation.

6.3. Terrazza Martini, Milan, 1 May 2020

During the May Day celebrations, Italian rock star Gianna Nannini sang, accompanied by the piano on the Martini terrace in Milan. She was standing there alone. In the background, one could see the cathedral, the roofs, the skyscrapers and deserted squares; the only sound was her singing. There were only two alternative camera frames: one on the singer, the other on the city. The salient presence of the invisible virus manifested itself as the effect of an immediate comparison between two situations: the current and real situation, and the usual situation, recalled. The latter emerged by a cognitive association to the usual May Day celebration broadcasted on television: a large square full of people, a stage crowded with pop stars, political flags, noises, music, lights, and movement. The former—that is, the current and real situation—was strikingly different: an absolute lack of people, the only sound coming from the singer, otherwise surrounded by silence, and no movement around. The camera shots were slow and repetitive.

The audience disappeared or was transformed into an immaterial spectator playing the role of consumer of the television message—an invisible user, called into being by a pressing yet disconsolate appeal.

6.4. New Year’s Concert, Vienna, 1 January 2021

This television event was awaited and codified, and the established content was well known: the immense ballroom of the Hofburg, whose multiple flowers were often shown in the foreground, a large orchestra with an excellent conductor, camera shots of the gold-en stuccos, chandeliers and shining ceilings. But there was a difference: the hall was absolutely empty, without an audience. As maestro Uto Ughi remarked before beginning the concert, “For us it is very strange to perform the concert in this empty hall”. The camera glossed over, dedicating a few images to the empty audience while lingering on the attending actors. The joyful and playful presentation of the musical pieces was missing, as was the rhythmic clapping that usually accompanied the final march.

To convey the idea that (almost) everything was developing as usual—but highlighting at the same time that it was completely different—there was no shortage of applause; however, it was merely a previously recorded sound. It was “virtual applause” that filled a substantial void with a familiar and ritually expected noise.

As if to respond to the suspicion that it was just a television gimmick, the final camera shots showed pictures of real people living in different places who had joined the initiative to be transformed into “virtual applauders”. These pictures were collected in a sort of portrait gallery. In every part of the world, there were still “flesh and blood” people who could fill and nullify the void: on New Years’ Eve, we were allowed to express this wish.3

6.5. President Joe Biden Swearing in Ceremony, Inauguration Day, Washington, 20 January 2021

Because of the virus and for reasons of public order (on January 6, Congress had been assaulted), the large clearing of the White House was desolate, but the ritual was celebrated on a crowded platform with some guests standing on the side terraces. They were spaced out and never filmed in the foreground. The absolute lack of “normal citizens” was compensated for by the ritual itself. The camera shots largely highlighted the public dimension of it (the president being sworn in, the speech, the national hymn, the flags) and the private dimension (hugs, greetings and smiles shared by the distinguished personalities attending the event). In these images, the almost “naked” moments achieved visibility.

The audience was represented only by a sea of stars-and-stripes flags that filled the clearing of the White House (see Figure 3): 100,000 flags were placed, one for every person who died of COVID-19.

Figure 3.

President Biden swearing in ceremony, Inauguration Day, Washington, 20 January 2021 (Photo Roberto Schmidt).

These images were shown with two close-up camera shots of one minute each in the context of a four-hour television event. Although briefly mentioned, they represented one of the pillars of the long narration, perhaps the most powerful and relevant. Apart from the few selected guests, there were the thousands of deaths. They were not physically present; they were evoked and brought to life by the many flags. Once again, the multitudes were lacking, but they were made present in the symbol of the common and (hopefully) shared national belonging.

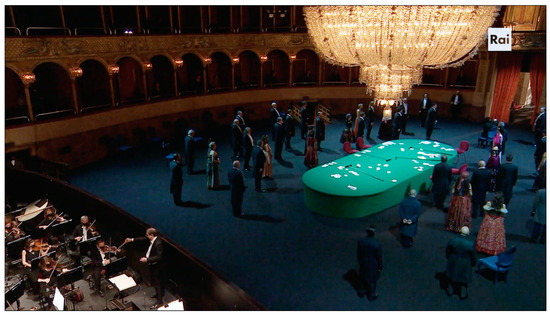

6.6. Opera Theatre, Rome, 9 April 2021

The following images can be interpreted as the final point of the process through which the absolute absence—the vacuum of people—became accepted as an event, metabolised and somehow normalised.

La Traviata was performed in Rome. The Opera Theatre lacked an audience, with no symbols aimed at representing it. The orchestra—directed by Daniele Gatti—was scattered all over the theatre, loges included. The scenic movements occupied the entire place, from the stage to the parterre and the loges. Vocalists, extras, the choir and the orchestra played in order to turn the whole theatre into a stage. The distinction between actors and audience was repealed; everything was play (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

La Traviata directed by Daniele Gatti, Opera Theatre, Rome, 9 April 2021 (Photo RAI).

The virus imposed a shortage of or reduction in interpersonal contacts, emptiness in public spaces, absence as the main feature of everyday life, and a new “taken for granted” to be constantly compared with the old and previous regime. The whole scenario of life was transformed, but nothing was cancelled. The theatre was turned into cinematographic communication, but an audience to refer to is always needed. Then, communication was established inside a television screen, and the audience existed through its implicit call: spectators were required to sit in front of a television set.

7. The Pope of the Rain

I have traced an interpretation of how TV communication managed the new absence of people in public spaces. I argued that this phenomenon, caused by the pandemic, radically changed what was taken for granted in the “reality system” of daily life.

The shocking and unnatural “presence of the void” produced a series of shifts in the accent of reality, which somehow transformed this void and made reality itself a new “possible everyday life experience”. The strength of the narration I am going to analyse is understandable only if we accept the idea that this case has a fundamental feature that distinguishes it from other narratives. What the images say is that “the void exists, but it is not filled”. To this message, I add a hypothesis: “The void may, perhaps, be transformed, but…”.

Let me restate the context. One of the immediate consequences of the pandemic was the cancellation of the direct and in-person relationship with religious rituality. The limited protests against the sudden and total closure of places of worship and the ban on religious demonstrations marked the limited collective relevance of such prohibitions. Only the ban on celebrating funerals encountered widespread disapproval, confirming that the collective management of mourning is the last collective rite of pertinence—or even of exclusivity—of the religious field. In general, the weak relevance of religion in the pandemic was mirrored by the relative silence of religious voices amid a concert of opinions given by specialists from various disciplines, by decision-makers of all kinds, and by ordinary people in a framework in which the media played an eminent role in the construction of reality.

7.1. Rome, Saint Peter’s Square, 27 March 2020

On the evening of 27 March 2020, the pope, standing alone (except for the occasional “technical presence” of the master of papal ceremonies), performed a ceremony officially named “extraordinary moment of prayer in times of epidemic” in an empty Saint Peter’s Square (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Rome, Saint Peter’s Square, 27 March 2020 (Photo Vatican Media).

The event was broadcast live worldwide, aired exclusively on Vatican Television. The images, the frames, the timing and the format itself (unusually, a unicum: an “extraordinary moment”) were fully designed and controlled by the director. There was no unexpected event apart from the rain. Its presence was both omitted from the narrative—at no time did an umbrella or an extemporaneous protection appear, and the pope continued his performance as directed—and, as I will show, smoothly incorporated into the narrative.

“With a simple but intense image, the pontiff arrived, alone and silently, on the top of the churchyard. The camera frames from above accentuated the feeling of solitude and at the same time the power of the scene” (Lomonaco 2020). This was the interpretation proposed by the Vatican broadcaster, which indicated one of the pursued aims: the pope’s solitude, summarised and transformed/transfigured by the power of the images that were devised and transmitted.

Solitude in places and the actors’ solitude; actions performed and speeches pronounced; and long silences and the interminable fixity of images: this is the key to understanding the “extraordinary moment”, which summarises and resolves its extraordinary nature in communication (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Rome, Saint Peter’s Square, 27 March 2020 (Photo Vatican Media).

But what constituted the exceptional nature of the event? More than one interpretation is viable. The first interpretation draws on the observation of the empty square. The exceptional nature of the event was not due to the pope standing there alone, but to the lack of any “we, there” in that moment. What counted was the desolation of a situation of solitude in which, however, the agents would still exist—even if they were not visible. In actual fact, there was a “we”, not in the flesh, but in front of the television. Though forced to miss out on the normal practices of daily life, to give up occupying public spaces, and unable to interact through essential face-to-face relationships, everyone might still have been present in the sphere of communication.

The emptiness of Saint Peter’s Square was similar to that of all the squares at that time, such as Piazza Duomo in Milan or St. Mark’s Square in Venice. Indeed, we could have perceived our solitude, but the pope could fill it because he brought us together in front of the television; the square was (desolately) empty, but we were all present in the communication.

According to this interpretation, which favours the media function, the pope played the role of a televangelist, in front of an empty physical square, but in an exceptionally crowded communicative square. This was a rare type of media event, even without the physical presence of interlocutors or witnesses; an “armchair pilgrimage” happening in an absolute and completely generalised form (Dayan et al. 1986; on the role of images in this type of mediated religious ceremonies, see also Dayan and Katz 1992, p. 146).

The pope, for his part, would have undertaken a widely tested action, albeit with some formal innovations: he issued a sort of radio message in a TV format, which—like any radio message—included content (Nardella 2019; Scardigno et al. 2021): “Have faith because Christ saves us in every misfortune” (the supporting source is the Gospel of Mark, 4, 35–41). The image recalled was one of a sea storm, and the ceremony finished with the ritual blessing.

This interpretation—which follows a frequented path in literature, detectable both in communication science and in the field of sciences addressing religious phenomena—can be paired with another one that combines the hypothesis of the “absent but present audience” with that of the “pope standing alone, but followed by an extremely wide audience”. Compared to the previous one, this interpretation is based on the incontrovertible observation of the pope’s complete solitude—a fact which constitutes the necessary interpretive pivot—but it is given a meaning and a qualification with respect to the recipients/users of the narrative.

Francis standing alone, embodying in a plastic way the essence of the “pontiff” role, that of being the bridge between the earth, which needs answers, and the sky, to whom questions are posed.(Lomonaco 2020)

The above details the Vatican comment regarding the event, expressing very probably the intention of the director, designer, and communicator of the event. The reference was to the priest role, which included in itself the multitudes of the faithful represented, and epitomised the investment of the multitudes in the singularity of the priest/intermediary as their representative. Indeed, the more the priest is intrinsically alone, to the point of appearing unique, the more his function is compressed and powerful. The pope must be alone to represent/have everyone with him.

An exhausted humankind but leaning on God has experienced this extraordinary event broadcast worldwide by Vatican Media. In an empty Saint Peter’s Square, gleaming in the rain, in a silence that echoed millions of prayers and a universal need for hope.(Lomonaco 2020)

Everyone, therefore, was present there precisely because the pope was completely alone, without any other celebrant of his religion and his church, without the splendour, the colours, the sounds, the ceremonial solemnity of an ancient and well-established ritual. Everyone was connected in the inner disposition, as everyone was represented/compressed in the uniqueness of the Catholic priest who, due to his institutional position, contains and expresses them all.

(Francis in an) empty square but followed by Catholics from all over the world. Francis’ meditation has flew over and overwhelmed the empty, thousand-year-old spaces of a city whose people are entirely locked up in their homes, which are transformed into domestic churches by prayer.(Lomonaco 2020)

It is quite clear that this interpretation is Catholic-biased. It is also very likely that it reflects, quite faithfully, the intentions of the Vatican broadcaster. An indication can be detected in the techniques adopted with a certain frequency: the alternation of long shots, sometimes taken from the perspective of the basilica, or from the pope’s point of view, in which the naked vastness of the empty square appears. Sometimes the shots are taken from the square, from the point of view of a faithful (if they could be present), from where a white dot, faraway and alone, celebrating the pope, was visible. The alternation of viewpoints indicated a dialogue, even if immaterial.

Another image that I believe is specific to the broadcaster culture is the one trans-mitted at the end, as a definitive confirmation of this narrative. The same image seems to represent an indication of how the message transmitted should be interpreted. In the last minute, once the rain had stopped and the night had fallen, the camera showed the illuminated façade of Saint Peter’s for admiration. Its silent beauty was there to impress. The camera slowly alternated close-ups and long shots, with no more sounds; the performance was over. What remained was an outstanding monument, all in itself, without human beings.

How should this be interpreted? Does beauty persist, and do work and human genius resist the passage of time? Will the structure that has produced all of it not decay and continue to over time (as it has done so far)? More specifically, will the church overcome and remain intact and shining, despite adversity, rain, and solitude?

Here, what resonates is the parable of Dostoevsky’s The Grand Inquisitor: the Catholic Church endures, its power cannot be undermined, human events pass by, but the structure remains; it is still intact and shining. So too do people pass by; this pope, too, once his action is over, withdraws and disappears from the scene, but the construction, the marvellous building, is there to stay. Indeed, it is the only thing to remain.

The third interpretation, and the one I am supporting, approaches the same images with a disenchanted posture. There is no hypothesis that goes beyond what appears. What we saw was the pope completely alone in a huge square with not a soul around. The fact that Pope Francis took his path through the square in solitude and that he climbed, with difficulty, the steps before Saint Peter’s—the place from which he would celebrate the “extraordinary moment of prayer”—underlined even more the complete absence of people.

“The pope is really alone, there is really no one around him”: What if this was the real message? What if the images only referred to themselves? What if, because of the pandemic, a veil had fallen and we were suddenly, in the short space of an hour, faced with the reality as it was? What if the “extraordinary moment” was not that of prayer (which still involves a dialogue, an otherness), but that of a revelation in which we simply saw what we are and where we were placed?

Obviously, this interpretation is different from the previous ones, as it forces us to follow a complex path, despite its apparent linearity. Schutz (1962, p. 229) recalled that in the epoch of the natural attitude, “What one puts in brackets is the doubt that the world and its objects might be otherwise than it appears to her/him”. In the “natural situation”, that is, in the world of pre-pandemic daily life, the doubt that could be put aside regarded the idea that the crowds surrounding the pope may signify a different phenomenon from what it appeared to us. At that moment of the pandemic, which turned the world of “normal” daily life upside down and emptied public spaces, the lack of people around the pope was considered obvious, and the usual “suspension of doubt” turned into its opposite, giving rise to certainty that “the situation is certainly different from what it appears to us”. This is what the first two interpretations assume: “The people are definitely there, even if we don’t see them; they are in front of a television, just as we are”.

The third interpretation deviates from this path and proposes an alternative: “the external world is as it appears to us now”. It was the doubt that it could be different that was suspended.

This is why these images remain in the archive of memory: they overturned the reality of the world in which we place ourselves, although without modifying the way we relate to it. We saw openly what we thought was not possible to see, not because it is hidden—the images indeed lingered for a long time on making things visible—but because it was so different from the everyday life reality to which we were anchored. At the same time, however, in the flash of a vision, we perceived that the “true” reality in which we were placed was exactly what the images indicated: the pope was truly alone in an empty desert.

One can adopt the hypothesis that this situation is completely transitory, exceptional, and abnormal. However, the new meaning of our experiences has placed us in front of a very different reality, perhaps a more “real” one. We must deal with it.

One might think that normality will return; once the rain is over and the pandemic is over, we will return to the usual “reality” of everyday life. We will adopt the usual epoch of the natural attitude. However, doubt crept in: the suspicion that the outside world may be exactly as it appeared to us on the evening of 27 March 2020. The revelation took place. It could be removed, opposed, or countered, but it might remain. And it might remain with the question, “Is Pope Francis the last priest of an extinct religion?” Buildings, temples, palaces, and squares were still there, but there was no longer a trace of their occupants or of their intended use. Sometimes, even memory can vanish. Archaeology is grounded in this. Did we maybe witness a vision that made us experience the configuration of a (near) future?

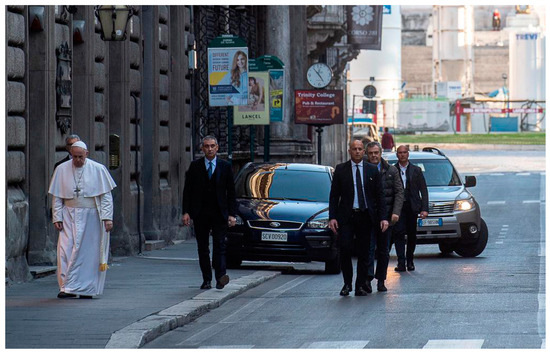

7.2. Rome, Via del Corso, 15 March 2020

The questions I ask are similar to those that Pope Francis himself asked. In his Christmas greetings to the Roman Curia (21 December 2019), the pope empathically declared:

And he went on, adding details:Brothers and sisters, Christendom no longer exists! Today we are no longer the only ones who create culture, nor are we in the forefront or those most listened to.(Pope Francis 2019)

We are no longer living in a Christian world, because faith—especially in Europe, but also in a large part of the West—is no longer an evident presupposition of social life: indeed, faith is often rejected, derided, marginalized and ridiculed. (…) There are countries where churches with an ancient foundation exist but are experiencing the progressive secularization of society and a sort of ‘eclipse of the sense of God’.(Pope Francis 2019)

The lockdown made the situation of solitude and emptiness obvious, although it was extraordinary. From the perspective of the pope, then, what happened on March 27 could represent an overturning of the situation of secularisation (Garelli 2020): he took on the secularisation itself and tried to reverse it, with the risk of failing. The path he traced in his speech to the Roman Curia was as follows:

We need to initiate processes and not just occupy spaces. (…) It is no longer merely a question of ‘using’ instruments of communication, but of living in a highly digitalized culture. In an approach to reality that privileges images over listening and reading.(Pope Francis 2019)

In fact, the “extraordinary ritual” was the second act of the narration. The first (on 15 March) was the silent and lonely pilgrimage to the crucifix in Saint Marcello al Corso, which is believed to have already rescued Rome from a pandemic, in a deserted and silent city of Rome. That same crucifix—a powerful and silent presence—would be placed in Saint Peter’s Square on 27 March (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Rome, via del Corso, 15 March 2020 (Photo Vatican Media).

Images and actions are consistent in the shots of the two extraordinary events: the solitude of a man, the unnatural silence, the lack of people. Slow shots filming the strenuous walk of Pope Francis, restrained movements, hints of a silent dialogue between the man and the symbols of his faith: the crucifix in Saint Marcello and the golden monstrance in Saint Peter. There was an alternate symmetry of the two points of view that suggested personal conversation and perhaps an agreement (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Rome, Saint Peter’s Square, 27 March 2020 (Photo Vatican Media).

In this (fragment of a) process of overturned secularisation, taking into account the radical fragility of the religious phenomenon, a message is being proposed: a path exists to draw on the tie between health and salvation. This path—indicated in a clear and whispered way for those who want to follow—is personal and lonely.

In this way, the (eventual) last of the believers, the (probable) representative of an extinguished religion, suggest a sort of “light enchantment”, based on the surrender to splendour, to power, to lavish rituals, to the multitude of priests; an enchantment basically reduced to its essential features (Aldridge 2013; Colliot-Thélène 1995). However, a question remains: in a situation of extreme danger, what is the attractiveness of salvation for those seeking to remain in good health?

8. Conclusions

To conclude, I suggest a research path regarding the images filmed in Saint Peter’s Square on 27 March 2020. If we ask ourselves why they are so vivid and powerful, we could answer by taking into account the extraordinary nature of the moment, when the pandemic radically eliminated any physical presence in public spaces. In this way, the phenomenon would be reduced to its context, a context that—very probably—will never be repeated, and that surely had never appeared before. In this case, the meaning coincides with the shared code (Eco 1976, p. 48 ff.; Hall 1980, pp. 119–20; 1997, pp. 21–22): “all of us are in that loneliness, we see ourselves as in a mirror and we appear, terrified, as we really are”. Then, another answer can emerge of a structural kind. In fact, we can follow the hypothesis that the signifier (that is, the images) has immediately melted with its meaning, that the connotative component coincides with the denotative component (Barthes 1972, pp. 114–15). This hypothesis would lead to an extraordinary short-circuit that reveals—in an unreproducible moment—a hidden reality: the pope is alone. In Foucauldian terms (Foucault 1980, p. 109 ff.), the power component would fall away without residue: the pope no longer manages for us, through his person, the salvific relationship with the sacred. The images said, “the pope is alone”, and the interpretation confirmed that “yes, the pope is alone”. The images said, “no one is with him”, and immediately the interpretation confirmed “yes, exactly; no one is with him”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | I refer to the “everything will be fine” of the early days, expressed in an immaterial way (sound) and in a joyful tone (singing and music). People were singing on balconies, that is, from a place where one can be visible without breaking the restriction posed to social encounters in the collective space (streets, squares, etc.). The same message, as we will see, was contained in the passage from the Gospel commented on by Pope Francis in the ritual of 27 March. |

| 2 | These images were “stolen”, recorded by chance when they were intended to remain secret. This feature revealed their radical relevance even more: they made clear that the world and its objects were certainly different from the way they appeared until a moment before. They produced a radical fracture in the epoch of the natural attitude and an immediate emergence of “fundamental anxiety”, precisely because they directly and openly confronted the origin of this epoch, always present but usually removed: “I know that I shall die and I fear to die” (Schutz 1962, p. 228). |

| 3 | A similar solution was adopted in various TV programmes, in which the presence of the audience in the studio was recalled through silhouettes of people sitting in the spaces usually dedicated to them. The fact that they depicted images of people who could not be there (for example, the president of the republic, the German chancellor, etc.) provided those cardboard silhouettes with the function of being recognisable as pure signs, referring to a desired presence, not as surreptitious means to hide the real absence, and indeed served as a reminder. |

References

- Aldridge, Alan. 2013. Religion in the Contemporary World: A Sociological Introduction, 3rd ed. Cambridge and Malden: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1972. Mythologies. New York: Hill and Wang. [Google Scholar]

- Bimbi, Franca. 2021. L’ageismo: Vita quotidiana e discorsi pubblici all’inizio della pandemia Sars Covid-19. In L’impatto sociale del Covid-19. Edited by Anna Rosa Favretto, Antonio Maturo and Stefano Tomelleri. Milano: FrancoAngeli, pp. 145–56. [Google Scholar]

- Colliot-Thélène, Catherine. 1995. Rationalisation et désenchantement du monde: Problèmes d’interprétation de la sociologie des religions de Max Weber. Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions 89: 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, Daniel, and Elihu Katz. 1992. Media Events: The Live Broadcasting of History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dayan, Daniel, Elihu Katz, and Paul Kerns. 1986. Il pellegrinaggio in poltrona. In La Narrazione del Carisma: I Viaggi di Giovanni Paolo II in Televisione. Edited by Gustavo Guizzardi. Torino: Eri-Rai, pp. 171–86. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa, Annamaria Silvana, and Terri Mannarini. 2020. The “Invisible Other”: Social Representations of Covid-19 Pandemic in Media and Institutional Discourse. Papers on Social Representations 29: 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1961. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. New York: Collier Books. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, Umberto. 1976. A Theory of Semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977. New York: Pantheon. [Google Scholar]

- Garelli, Franco. 2020. Gente di poca fede: Il sentimento religioso nell’Italia incerta di Dio. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Guizzardi, Gustavo. 2005. L’agonia mediatica: Malattia, passione e morte di Giovanni Paolo II. Religioni e Società 53: 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Stuart. 1980. Encoding/Decoding. In Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972–1979. Edited by Stuart Hall, Dorothy Hobson, Andrew Lowe and Paul Willis. London: Hutchinson, pp. 128–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Stuart. 1997. The Work of Representation. In Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. Edited by Stuart Hall. London: Sage, pp. 13–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lomonaco, Amedeo. 2020. Il Papa Prega per la Fine Della Pandemia: Dio, Non Lasciarci Soli in Balia Della Tempesta. March 23. Available online: https://www.vaticannews.va/it/papa/news/2020-03/preghiera-papa-francesco-coronavirus-adorazione-indulgenza.html (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Lusardi, Roberto, and Stefano Tomelleri. 2020. Bergamo, March 2020: The Heart of the Italian Outbreak. European Sociologist. Available online: https://europeansociology.org/european-sociologist/issue/45/from-esa/378066e7-f5e2-4c9e-a64b-cc5d24cc7a08 (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Nardella, Carlo. 2019. La strategia del quotidiano: Nuove forme della ristrutturazione cattolica. Problemi Dell’informazione 44: 491–513. [Google Scholar]

- Pope Francis. 2019. Address of His Holiness Pope Francis to the Roman Curia for the Exchange of Christmas Greetings. December 21. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2023/december/documents/20231221-curia-romana.html (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Scardigno, Rosa, Concetta Papapicco, Valentina Luccarelli, Altomare Enza Zagaria, Giuseppe Mininni, and Francesca D’Errico. 2021. The Humble Charisma of a White-Dressed Man in a Desert Place: Pope Francis’ Communicative Style in the Covid-19 Pandemic. Frontiers Psychology 12: 683259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schutz, Alfred. 1962. Collected Papers I: The Problem of Social Reality. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Schutz, Alfred. 1976. Collected Papers II: Studies in Social Theory. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).