1. Introduction

The study of spirituality in the experiences of young people has garnered significant interest in recent years, both internationally and within Italy, highlighting the complex historical relationships between youth, religion, and spirituality. Italian research has provided valuable insights into these dynamics (

Bichi and Bignardi 2015;

Cipriani 2021;

Crespi and Ricucci 2021;

Garelli 2011,

2016;

Giordan 2010;

Giordan and Sbalchiero 2020;

Palmisano 2016). This topic is part of a larger discourse on contemporary interactions with the sacred, including diverse forms of religious affiliation both within and outside institutional church settings. Sociologically, spirituality is not a straightforward subject but, rather, a multifaceted and elusive concept (

Bainbridge 1997;

Beckford 1990;

Heelas and Woodhead 2005;

Sutcliffe and Bowman 2000). Over time, as spirituality has been integrated into the sociology of religion, it has acquired various meanings, resisting a singular definition (

Bruce 2002). This diversity is also evident in the post-secular discourse, in which secularisation modifies rather than eradicates religion (

Acquaviva and Guizzardi 1973;

Berzano 2009,

2014,

2018,

2023;

Cipriani 2017;

Giordan 2004,

2007;

Palmisano and Pannofino 2021).

This trend is also observed internationally, with a significant increase in young people identifying as non-believers (

Smith and Denton 2005). The relationship between young people and religion in Europe is multifaceted (

Vincett et al. 2015) and defies simple explanations. While some scholars point to a trend of secularisation (

Bruce 2002), particularly in terms of declining participation (

Voas 2009), others argue that religious beliefs may persist even with lower levels of practice (

Davie 2000). Studies suggest a generational gap in religious engagement in Europe, with young people showing lower levels of participation compared to older generations (

Wyn and Cahill 2015;

Palmisano and Pannofino 2017;

Molteni and Biolcati-Rinaldi 2023;

Stoltz 2020). Furthermore, there is limited evidence to suggest that these young people will become more religious later in life (

Voas and Crockett 2005;

Kay and Francis 1996). However, this decline in practice may not necessarily translate to a decline in belief.

Davie (

2002) argues that religious belief itself may remain high in Europe, even with a decrease in traditional religious activities, as evidenced by the persistence of individualised religious practices among young people (

Collins-Mayo et al. 2010).

In this context, it is important to highlight two trends identified in the literature: firstly, that religious faith can persist even as religious practices decline (

Davie 2002), and secondly, that religious faith can evolve into more personalised forms, as indicated by Denton and Smith’s research on “moralistic therapeutic deism” (

Smith and Denton 2005). These trends, as will be discussed later, are evident among our study participants who, while not identifying as non-believers, engage in personalised forms of belief expression and manifest their faith through personalised interpretations and practices. Furthermore, this aligns with the development of faith among young people (

Fowler 1981). Fowler observes that during the teenage years, individuals undergo a transition where they progressively assume greater personal responsibility for their beliefs.

Understanding this complex interplay of influences requires a multidisciplinary approach that takes into account sociological and cultural perspectives. Studies suggest that young people’s spiritual journeys are deeply influenced by their immediate social environments, including family dynamics, educational contexts, and peer relationships (

Mason et al. 2007;

Smith and Denton 2005;

Smith and Snell 2009). These factors contribute to a nuanced understanding of how spirituality is lived and experienced by young people in contemporary society.

This framework sets the stage for exploring the following question: What religious and spiritual directions do adolescents and young adults residing within familial settings navigate as they straddle the threshold between the beliefs and affiliations inherited from previous generations and the evolving future they are actively contributing to? This question is key to understanding how modern youth reconcile their inherited religious traditions with the dynamic and often secular environment they inhabit. In other words, the dichotomy between tradition and modernity plays a crucial role in shaping young people’s spiritual landscapes. On one hand, enduring religious practices are passed down through generations, and these practices are deeply embedded in cultural and familial identities. On the other hand, contemporary youth culture is marked by a shift towards individualism and a personal quest for meaning, which often leads to a less institutionalised form of spirituality.

2. Data and Methods

From a methodological point of view, our research followed a two-phase approach and involved a ‘mixed-method’ perspective, namely a sequential exploratory research design (

Creswell and Plano Clark 2011), aiming to integrate the qualitative and quantitative phases (

Bernardi 2008;

Cardano 2011). The initial exploratory phase, which was conducted through in-depth interviews, involved 63 young individuals selected from a high school in Vicenza, in the Veneto region of Italy, and students attending sociology courses at the University of Padua, Italy. During the second phase, to address the challenges posed by sampling students, 1384 questionnaires were collected from 72 classes within the same high school in Vicenza, so this can be considered a case study, as it encompasses all students from a high school. In particular, before collecting the questionnaires, together with the school principal, we sent a request to all parents explaining the research objectives and asking for consent to interview their minor children. In the end, only four families denied consent. Subsequently, we visited the school and collected the questionnaires in 72 different classes, following the ethical guidelines proposed in (

Silverman 2016;

Bernardi 2008): ensuring the voluntary participation of girls and boys, maintaining confidentiality, avoiding harm to participants, and fostering mutual trust. The data were collected anonymously and used only for research purposes in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR-2016/679) adopted by the European Union, and in compliance with Italian legislation (D.Lgs. 101/2018), which governs the processing of personal data in these areas. Therefore, the data were collected and stored anonymously, voluntary participation in the survey was ensured, and the survey was conducted in complete anonymity.

In the forthcoming data exposition, the term ‘young people’ denotes individuals aged between 13 and 20 years, inclusive of adolescents and those transitioning into or already in adulthood. To facilitate statistical analyses, age groups were delineated (13–16 and 17–20), as explained below.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the data, we employed a multifaceted statistical approach that encompassed descriptive statistics, ANOVA, and principal component analysis (PCA; (

Albano and Loera 2004)). A one-way ANOVA was then utilised to determine whether statistically significant differences existed between groups based on age (13–16 versus 17–20) and place of residence (countryside versus city). This analysis allowed us to assess whether these factors exerted an influence on the observed patterns. Finally, PCA was employed to identify underlying patterns and reduce the dimensionality of the data, potentially revealing hidden relationships between variables. This multifaceted approach, encompassing both exploratory and confirmatory techniques, provided a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the data, enabling us to draw meaningful conclusions and gain novel insights.

Among its objectives is elucidating the variance in the initial data (observed variables) by extracting information from a multivariate table and expressing it as a set of new variables, which will be fewer in number than the observed variables; these new variables are known as principal components (

Albano and Molino 2011;

Bolasco 2014). In this instance, the analysis was applied to a battery of twelve items, which respondents were asked to express agreement with on a ‘scale from 1 to 10’ (

Sciolla 2004), regarding various statements concerning spirituality and its relationship with religion, as articulated in the initial qualitative phase. The aim of this process was to extract new components based on the correlation between them (

Widaman 2007). The criteria used in assessing both the number of components to extract and the goodness of fit of the solution relative to sample adequacy were as follows: first, the Kaiser–Guttman criterion, pertaining to eigenvalues > 1, identifies components with higher variance and, thus, greater importance, and this criterion led to the extraction of two principal components that explained nearly 60% of the total variance (56.7%). The second criterion, based on the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure, which ranges from 0 to 1, is useful for evaluating whether PCA is an appropriate tool given the available data. Values above 0.6 are considered acceptable, with optimal values exceeding 0.8; when applied to our dataset, the KMO index confirmed the adequacy of the solution with a value of 0.815, and the Bartlett’s test statistic was significant, with a

p-value < 0.01.

3. Results

In terms of the socio-demographic profile of our sample, seven out of ten respondents (N = 1384) identified as female (F: 72.8%; M: 27.2%). Regarding religious identification, 94% identified as Catholic, 2% as Orthodox, 2% as Muslim, 1% as Protestant, and 1% as other. In terms of the age distribution, the average age was around 17 years old. To streamline our analysis and facilitate an insightful comparison, we categorised the participants into two age groups, 13–16 (n = 625; 45.2%) and 17–20 (n = 759; 54.8%) years, allowing for a clear distinction between adolescents and young adults. This adjustment was intended to enhance the effectiveness of our comparisons and ensure a thorough examination of age-related dynamics.

Moreover, the decision to incorporate the variable related to residential location into the survey stemmed from a desire to comprehensively explore potential connections between living environments and the spiritual and religious experiences of young people. By including this factor, we intended to investigate whether variations in residential settings could influence these experiences, as well as they degree to which they could. The data revealed a nearly even split, with approximately 46% of participants residing in the ‘countryside’ (rural areas or small provincial towns with populations of up to 3000 inhabitants) and the remaining 54% identified as residing in a ‘city’ (35% lived in municipalities exceeding 15,000 in terms of population, provincial capitals, or metropolitan areas). Examining these two types of living environments enabled us to delve deeply into the potential correlations between residential context and spiritual or religious practices among our respondents.

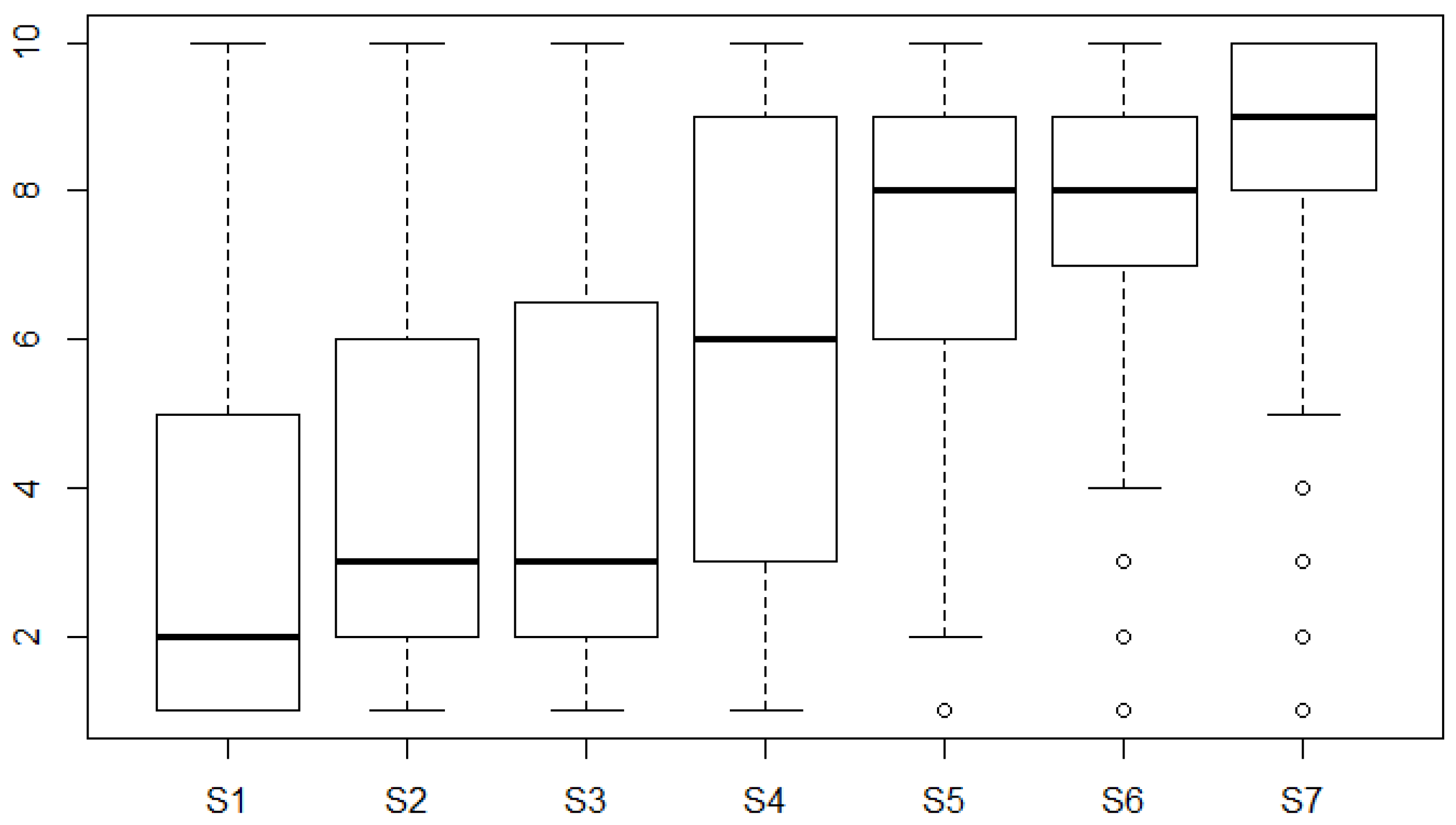

Upon an overall examination of the data, several intriguing aspects arise within the survey section pertaining to the characteristics of spirituality and its relationship with religion. Particularly noteworthy is the observation that the domain of spirituality is generally defined as distinct from that of religion (

Figure 1). This finding suggests an inherent separation between the two realms, raising intriguing questions about the nature of spirituality and its perceived autonomy from organised religious practices, which is consistent with contemporary expressions of spirituality within the framework of modernity (

Giordan and Sbalchiero 2020;

Palmisano 2016;

Plancke 2019).

Our analysis revealed how spirituality is perceived and practiced among the respondents. Notably, three-quarters (75%) of the participants disagreed that spirituality is related to the traditional confines of religious institutions, such as churches, mosques, or temples (S1). Moreover, over half of the respondents dissociate spirituality from belief in God (S2) and participation in religious rituals (S3). This perspective is further supported by a substantial majority of the participants (75%) associating spirituality with the pursuit of inner harmony (S7) and an equal proportion linking it to acts of altruism and kindness (S6). The participants expressed strong agreement with these linkages (values ranging from 7 to 10 on the scale). Additionally, three out of four respondents identify the integration of mind, body, and spirit as key components of spirituality (S5), while half of the participants believe that spirituality is closely tied to seeking meaning in one’s life (S4). These findings indicate a predominant inclination among young people towards a form of spirituality that extends beyond traditional religious frameworks. They favour a personalised approach that emphasises inner harmony, well-being, and ethical behaviour (

Giordan and Sbalchiero 2020;

Palmisano 2016;

Plancke 2019). This shift suggests that contemporary spirituality among youth is focused on individual exploration and holistic well-being rather than adherence to established religious doctrines and practices.

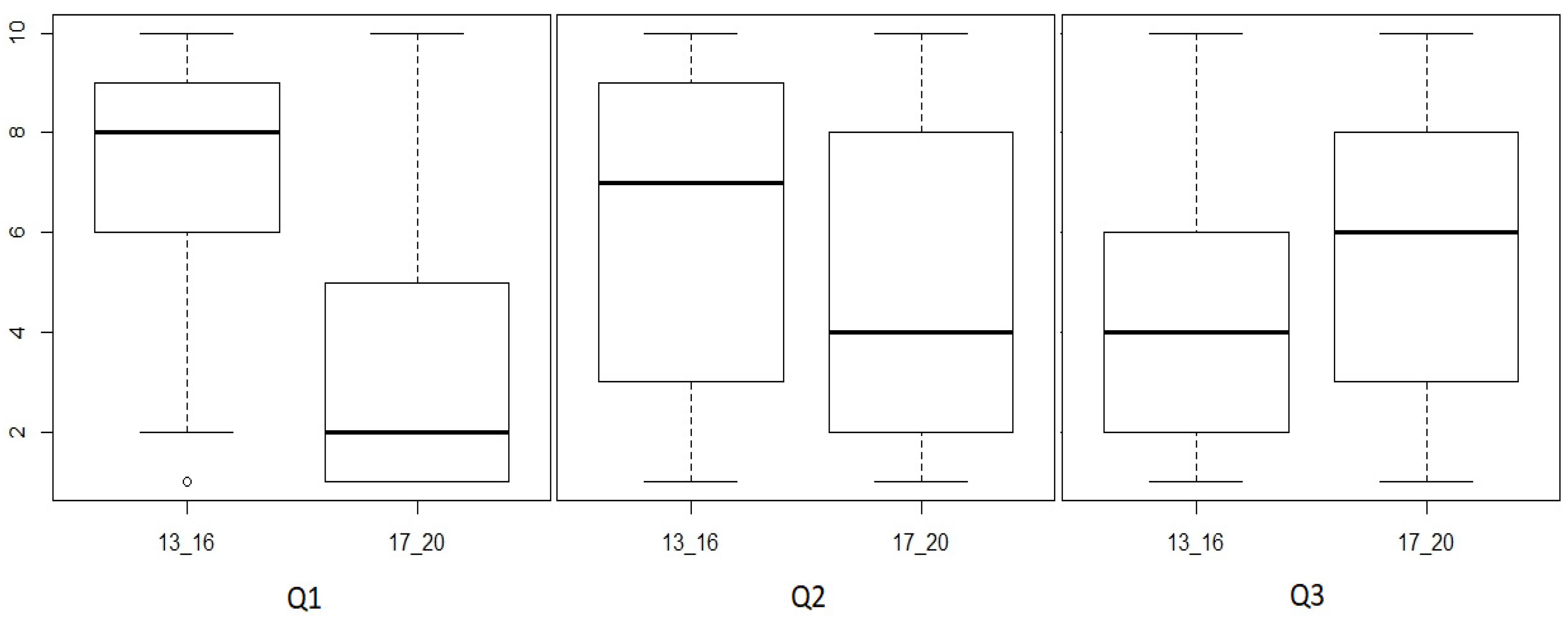

While no significant gender differences were observed, disaggregating the data by age group revealed two distinct patterns of engagement with religious and spiritual practices. A one-way ANOVA unveiled statistically significant evidence (

p < 0.05) suggesting an intricate interplay between spiritual practices and the two chosen age groups (

Figure 2).

These data reveal a fascinating contrast between the religious attitudes and practices of the youngest (13–16 years old) and oldest (17–20) respondents. While the oldest group overwhelmingly disengages from traditional religious activities, the youngest group demonstrates a high level of engagement with and adherence to religious beliefs. This divergence suggests a potential generational shift in religious attitudes, with the older group embracing a more personal and individualised approach to religion and spirituality.

The significant difference in agreement with statement Q1 (I engage in religious activities) between the age groups highlights a substantial gap in the practice of and participation in religious activities. The oldest respondents (17–20) were the most likely to report not participating in religious activities: seventy-five percent disagreed with statement Q1, and conversely, the youngest respondents (13–16) reported the highest rate of participation in religious activities. Moreover, the younger group’s higher level of agreement with statement Q2 (I conduct my spiritual life in accordance with my religion) suggests a stronger connection between spirituality and religious beliefs for them: three out of four respondents aged 13–16 agreed with statement Q2, while those aged 17–20 mostly disagreed. Similarly, the oldest respondents reported practicing religion and/or spirituality only when they need it (Q3: I practice religion and/or spirituality only when I need it), while three-quarters of the youngest respondents disagreed with this statement.

Although 94% of the respondents, as indicated earlier, identify as Catholic, there are differences between the two groups when asked if they ‘consider themselves Catholic and actively practicing’. Younger individuals are more likely to identify as convinced and actively practicing Catholics: about half (53%) of those in the 13–16 age group, compared to less than 28% of the 17–20 age group. Further supporting these findings, there are also significant differences (ANOVA,

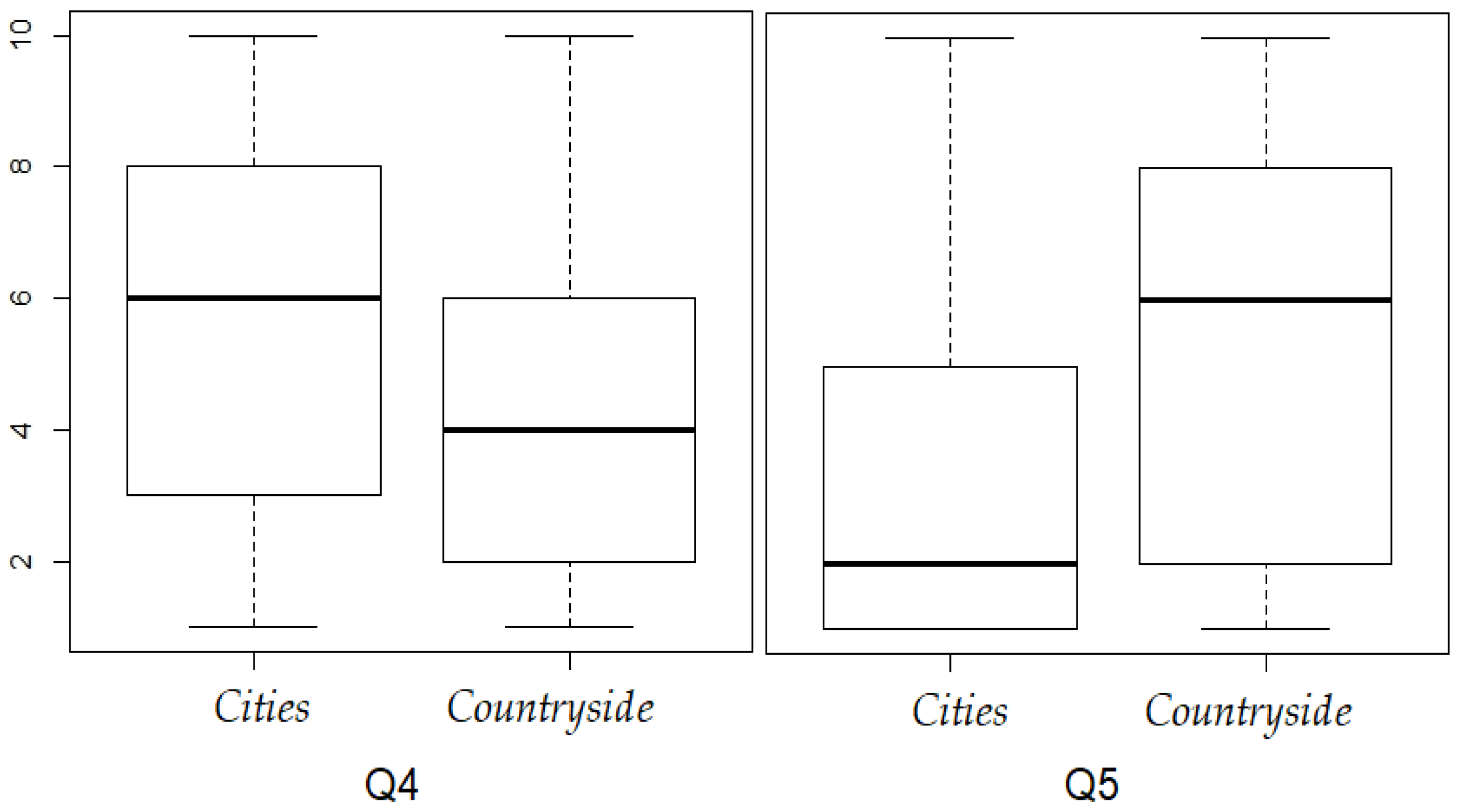

p < 0.05) in terms of place of residence (

Figure 3) between the respondents who reside in the countryside and those who reside in cities.

The data unveiled a compelling connection between the place of residence and religious attitudes, which appeared to be influenced by the local context. Young people in small communities tend to gravitate more towards religious spirituality, potentially due to the stronger presence of local religious institutions (Q5: I participate in religious services every week). This exposure to the Catholic religion’s message and values likely shapes their cultural identity and spiritual development. Moreover, educational agencies and parish-based services may also play a role in these socialisation processes, further reinforcing these religious influences; the enduring ties with religious contexts and practices, such as participating in sacraments and parish activities, further support the argument that young people, especially those in small communities, are still connected to organised religion, and this highlights the potential influence of local environments on young people’s religious outlooks (

Beaman and Tomlins 2015;

Collins-Mayo et al. 2010;

Crespi and Ricucci 2021;

Genova 2018). However, in large cities, our data suggested a contrasting trend. Respondents residing in these areas may be more likely than others to agree with the following statement: ‘My spiritual life is personal, and I do not accept the mediation of religious institutions’ (Q4). This suggests a potential preference for a more individualised and personal approach to spirituality, with less reliance on traditional religious structures. In urban contexts, as compared to smaller towns, respondents seem to be more oriented towards a form of spirituality that, on one hand, does not include religious practice and, on the other hand, values a personalised spiritual experience in line with contemporary spiritual trends (

Giordan and Sbalchiero 2020;

Palmisano 2016;

Plancke 2019).

Building on this evidence, it is worth highlighting the discussion regarding classic spiritual orientations and their relationship with the religious sphere. In a section of the interview guide, the participants were asked to interpret the main orientations related to spirituality, namely ‘spiritual and religious’, ‘spiritual but not religious’, ‘religious but not spiritual’, or ‘neither of the two’ (

Ammerman 2013,

2014), and, subsequently, to position themselves within the orientation closest to their own experience. Considering these types in the Weberian sense (

Sbalchiero 2021), which is traditionally done to define and understand the relationship with the sacred through the potential meanings it may assume, there was an opportunity to intercept additional nuances that emerged during the initial interviews. Immediately, these young individuals encountered difficulty in aligning themselves with these orientations, prompting the addition, as suggested by the interviewees themselves, of the ‘spiritual but not entirely religious’ profile. This profile was more frequently chosen not only during this initial exploratory phase (in-depth interviews) but also during the subsequent phase with the questionnaire. In the survey section on existential orientations, the respondents were asked to place themselves within the orientation they felt closest to their own experience, following the typology illustrated previously, with the addition of the ‘spiritual but not entirely religious’ profile, which emerged during the first phase of in-depth interviews (

Table 1).

While the ‘neither religious nor spiritual’ type was independent of age group (an average of 13% in rural areas, with a slight increase to 16% in cities), just as the ‘religious and spiritual’ type had a low preference percentage, in terms of age group and place of residence, some differences emerged regarding the continuity or discontinuity between the spiritual and religious spheres. Meanwhile, overall, the ‘spiritual and religious’ type was preferred by 16% of respondents; this is particularly true among the youngest (23.5% residing in the countryside and 21.8% residing in cities), with about double the number compared to those who choose it in the 17–20 age group (12.6% countryside; 11.3% city). Conversely, the ‘spiritual but not religious’ type was chosen mainly by the older respondents (30.1% countryside; 30.1% city), with about, in percentage terms, double compared to those who choose it among the youngest respondents (15.8% countryside; 15.9% city). Finally, for both age groups, the ‘spiritual but not entirely religious’ type was the most frequently chosen, with an average of about 40% in both cities and the countryside. Considering these orientations, together with what was discussed above, among the youngest respondents, spirituality and religion appear the most connected, while their older colleagues emphasise the spiritual sphere to the detriment of the religious one. However, this profile is present across both age groups and places of residence, and it is intriguing because it is positioned between ‘religious’ and ‘non-religious’. While it diverges from the ‘spiritual and religious’ type, as it is characterised by a position in opposition, with varying degrees of intensity, to religion and church mediation, it also distinguishes itself from the ‘spiritual non-religious’ type, as these young individuals reject being labelled ‘non-religious’ and prefer to be deemed ‘not entirely’ religious. This point is particularly intriguing from a methodological standpoint because it embodies what

Ammerman (

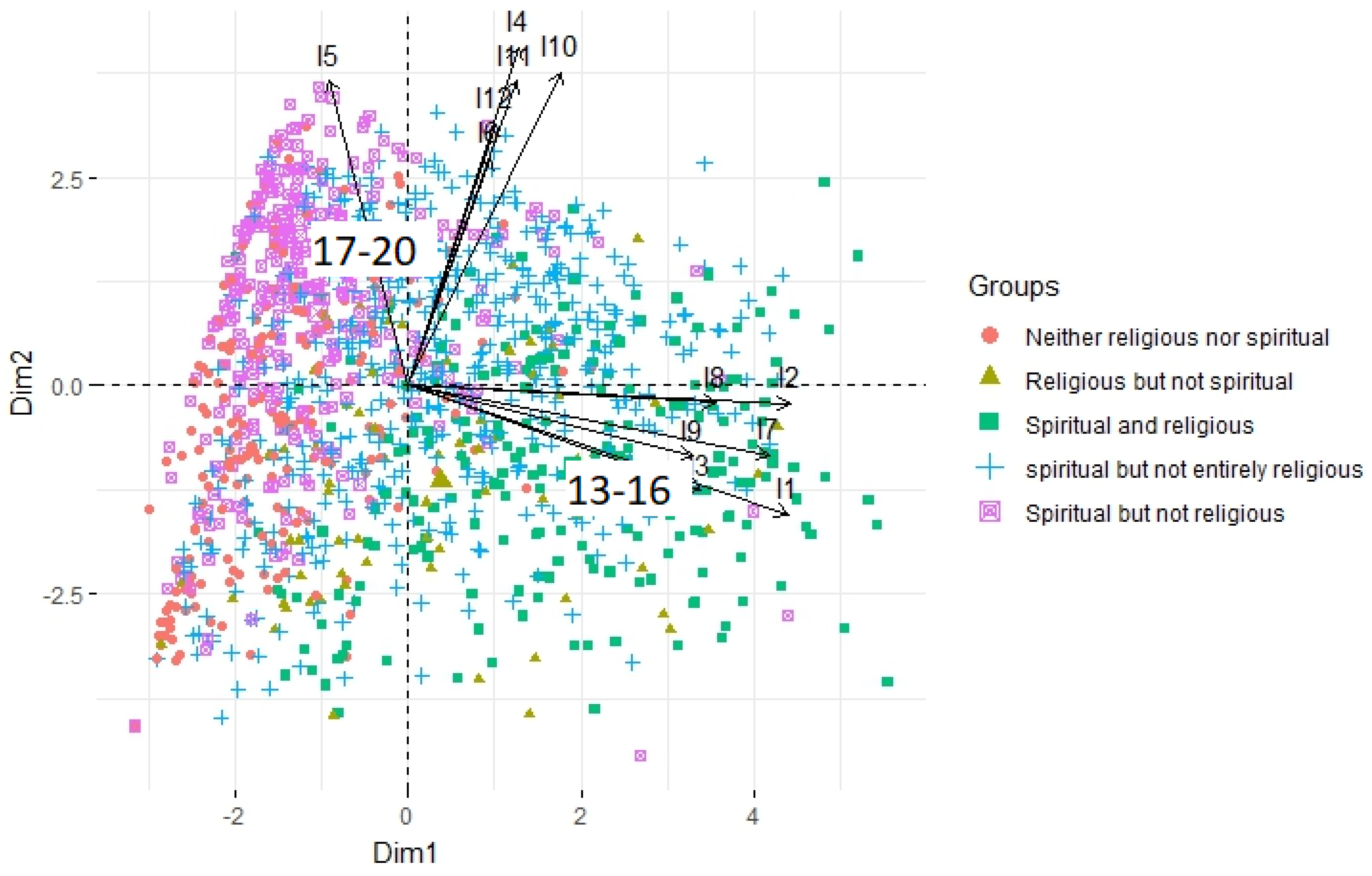

2013) has termed going beyond dichotomies. It introduces an intermediate category that could not have emerged if we had strictly adhered to the classic profiles of spiritual and religious identification. Additional elements useful for the discussion regarding age and orientation can be obtained via the results of the PCA (

Table 2).

The two extracted components can be interpreted as two orientations that involve conceiving and experiencing spirituality in its relationship with religion. In line with what has been seen previously, the first dimension informs us about a form of spirituality connected to religion. It includes the following survey items: I2 (I cultivate a spiritual life in connection with the religion I identify with), I1 (I participate in religious rites), I7 (I participate in religious services weekly), I8 (spirituality is the search for personal harmony and well-being), I3 (I pray also in solitude), and I9 (spirituality is an ethical orientation that influences behaviour). Those with orientation, which is rooted in rituals, religion, and personal growth, view spirituality as deeply intertwined with the religion they identify with. In fact, they actively participate in religious rites and services (I1, I7), finding that these practices provide a structured framework for connecting with something greater than themselves. However, their spirituality extends beyond these public rituals (I7). They cultivate a personal spiritual life (I2) that includes solitary practices such as prayer (I3). This allows them to explore their inner world and seek personal harmony and well-being (I8) and to live ethically (I9). Their spirituality is a tapestry woven from both communal practices (religious services and rites) and individual exploration (prayer and reflection).

The second dimension captures an orientation towards spirituality and religion characterised by independence and personal exploration and includes the following survey items: I4 (I turn to God only in times of need), I10 (I cultivate my spirituality in my own way), I5 (spirituality does not derive from sacred scriptures), I11 (I maintain my freedom from religion), I12 (my spiritual life is personal; I do not accept the mediation of the religious institution), and I6 (I am open to participating in rites that represent alternatives to those of traditional religious services). While respondents with this orientation may not entirely reject religion, they maintain a distance from it, prioritising personal interpretations over established doctrines and seeking God only when needed (I4, I11, I5). Furthermore, they value their freedom from religious institutions (I12), potentially finding traditional practices irrelevant and seeking alternative ways to connect with the spiritual (I6, I11). Their spirituality is self-defined, and they draw inspiration from various sources or forge their own unique path (I5, I10). They focus on personal autonomy to explore and define their own spiritual beliefs, independent of established religious structures and texts (

Giordan 2010), and this represents an idea of spirituality that can be defined as horizontal (

Palmisano 2016), meaning that it involves less religious practice (

Blasi et al. 2020;

Cipriani 2021) and is more closely based on a personalised experience. By considering the variables within the correlation circle (

Figure 4), it is possible to analyse how the two dimensions are associated (

Abdi and Williams 2010) with the categorical variables (

Husson et al. 2017), namely orientations and age.

On one hand, the youngest people we met were those who most strongly associate with Dimension 1 (right side of the figure, with items I2, I1, I7, I3, I8, and I9), which encompasses a spirituality connected to their religion of belonging, in line with what has been discussed above. These data suggest that the youngest are still grappling with the message and values of the Catholic religion, which evidently represents a cultural and identity reference point present in the socialisation processes implemented by the complex of educational agencies. In addition, Dimension 1 was more strongly associated with the ‘spiritual and religious’ and ‘religious but not spiritual’ orientations: religious experiences are evidently still present for this age group to varying degrees based on experiences of growth in a religious context, with reference to the sacraments and educational and cultural services offered by parishes.

On the other hand (top side of the figure, Dimension 2, with items I4, I0, I5, I11, I12, and I6) the oldest of the young people we met were those most strongly associated with a spirituality that has already taken a step away from the contexts of religious traditions, aligning with a horizontal spirituality that takes forms of personalisation beyond the boundaries of religion (

Palmisano et al. 2021). This dimension is more critical of institutionalised religion than Dimension 1 and does not contemplate either participation in or a call to religion, as was the case among the youngest (

Wallis 2014). In confirmation of this trend, this dimension was strongly associated with those who declared themselves to be ‘spiritual but not religious’ or ‘neither spiritual nor religious’.

Finally, it is worth noting that the ‘spiritual but not entirely religious’ orientation was present across the two identified dimensions and both age groups. In other words, it is an orientation that is contemplated in a transverse way, and in addition to being the most often chosen, it is interesting from a methodological point of view because it introduces an intermediate category that could not have emerged if we had strictly adhered to the classic profiles of spiritual and religious identification. This orientation suggests that the relationship between spirituality and religion is more complex and nuanced than traditional categories suggest (

Ammerman 2013) and it is possible that individuals who identify as ‘spiritual but not entirely religious’ are drawing on both religious and non-religious sources of meaning and identity. This finding highlights the need for more nuanced and inclusive approaches to measuring spirituality and religion.

4. Conclusions

The main findings of the present paper can be summarised by beginning with the two previously identified dimensions, which as we have seen, delineate two profiles that, if not opposed to one another, certainly present some peculiarities. On one hand, we have the youngest participants and those who carry out their main activities in small provincial contexts, for whom spirituality has to do with the religious sphere, characterised by participation in rites, mass, and parish activities. For these young people, faith paths, even when lukewarm, are undoubtedly influenced by a strong sense of belonging to local Catholic contexts. It is indeed undeniable that the Catholic context variable, especially in Italy, where the research was carried out, is not only prevalent but also a part of the culture, conditioning attitudes, even among those who distance themselves from it or do not fully embrace the doctrinal and value complex that characterises it. In this sense, spirituality, for the youngest we met, is still connected with religion and represents the subjective side of the personalised re-elaboration of the official faith, which is still frequent.

On the other hand, the profile of the older individuals among young people we met appears different because of their search for greater autonomy of choice and personalised experiences, in line with the trends highlighted in the international debate (

Tusting and Woodhead 2018). This is, in this case, a spirituality that goes beyond the religious context and emphasises the ‘spiritual but not religious’ sphere (

Huss 2014;

Mercande 2014;

Parsons 2018). Between these tendencies lies the ‘spiritual but not entirely religious’ orientation, which as illustrated above, represents the passage from adolescence to adulthood, when the ties with religion, on one hand, give way to new experiences and processes of maturational transformation, which makes the relationship with religion more problematic; on the other hand, they remain and can still be useful in the attempt to place one’s own experience.

Further complicating the matter is the age variable (

Smith and Snell 2009). Despite the fact that the segment considered is rather restricted and does not refer to different generations, the 13–16 and 17–20 age groups prefigure two ways of relating to the spiritual and religious sphere that are in some ways opposites. Whether spirituality is conceived of as strictly linked to religious experience or whether called upon only when one feels oneself in difficulty turns out to be a central element for understanding the transition in progress, as expressed by the ‘spiritual not entirely religious’ orientation. Interestingly, the study also revealed a transitional phase represented by the ‘spiritual but not entirely religious’ orientation. This group, primarily composed of adolescents, reflects the struggle to reconcile their evolving independence with lingering ties to their religious background. Even within a limited age range (13–20), there was a noticeable difference in how young people perceive spirituality, and this highlights the nature of this concept during adolescence and early adulthood.

The findings of this study have important implications for our understanding of the role of spirituality in the lives of young people and developing more inclusive and nuanced approaches to measuring and understanding spirituality in contemporary society. This study highlights the complex and multifaceted nature of spirituality among young people, particularly in relation to religion, and the identification of a transverse orientation between spirituality and religion suggests that the relationship between these two is more complex and nuanced than previously thought. In fact, the intermediate ‘spiritual but not entirely religious’ orientation represent a spectrum of possibilities that extends beyond the traditional dichotomy between the religious and non-religious, and this complexity is further enriched by the role of age and the evolving concept of spirituality itself. At the same time, this category cannot be viewed as another binary or as a highly exclusive category compared to other orientations. Rather, it should be seen as one of the entry points into the multiple nuances in people’s responses regarding the relationship between religion and spirituality. Overall, the study challenges the traditional views of religious decline among young people. While there may be a decrease in conventional religious engagement, a shift towards a more personalised and independent approach to spirituality is evident. This complex interplay between age, religiosity, and personal experiences necessitates further research, which the specific mechanisms via which local religious realities and educational agencies impact young people’s spiritual development could be explored, particularly within the context of small communities. Additionally, investigating how these dynamics differ across diverse geographical and religious contexts would provide a comprehensive understanding of this complex relationship and raise intriguing questions about the evolving nature of religious attitudes and practices across generations. By examining the diverse ways in which youth engage with spirituality, researchers can gain insights into the future trajectories of religious belief and practice because the study of young people’s spirituality is a vibrant field that reflects broader societal changes and the ongoing evolution of religious and spiritual landscapes. This exploration not only enhances our understanding of youth culture but also provides a window into the broader processes of cultural and religious transformation in the modern world.