1. Introduction

When reflecting today in the 21st century from a Western perspective on the triad of the words “religion” (without specifying which one), “public space” (without detailing any specific one to represent them all simultaneously), and “society” (understood in its most global sense), one considers “multifaith spaces” in general, and specifically the recent “multifaith room constructed in the main lobby of the Pediatric Cancer Center Barcelona (PCCB) at the Hospital Sant Joan de Déu (SJD)”, the first building of its kind in the world and a leading reference in international pediatric oncology.

It is necessary to explain from the outset that the authors of this article are also part of the team of designers and architects who have built this multireligious space, collaborating from the beginning in the initial phase of research and reference collection, as well as in the successive phases of design and construction of the room. We believe it is important to clarify this to place the reader in the correct context and to emphasize that academics and university researchers dedicated to design and architecture can also collaborate with private companies that value research, thus facilitating knowledge transfer and building bridges between academia and society.

1.1. Terminology

Before delving into the case study at the heart of this article, it is necessary to specify the terminology used. It must be clarified that an “ecumenical space” is not the same as a “multifaith space” (

Biddington 2013,

2021). The former, ecumenical, refers to a space shared among different Christian denominations, mainly divided among Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant. An interreligious or multifaith space, on the other hand, is much more complex, as if the ecumenical space were not complex enough already, referring to a space of coexistence among different religions. The main ones would be Christian churches in their three cited branches but also Muslim mosques, Jewish synagogues, Hindu stupas, Buddhist pagodas, and Shinto shrines. This also includes all other minor religions not mentioned. Furthermore, these spaces must also welcome those who do not profess any religion but seek a place for personal reflection and meditation. Many different terms have been used to refer to such versatile spaces, and here we cite the most used ones: Multifaith Room, Quiet Room, Prayer Room, Stiltecentrum, Raum der Stille, Room for Reflection, Meditation Room, Rest and Faith Room, Faith and Reflection Room, Contemplation Room, and Peace Room (

Crompton 2013). In this article, we will refer to this space located on the ground floor of the PCCB at the SJD hospital using any of the mentioned terms, prioritizing “Multifaith Room” whenever possible (

Figure 1), or “Silent Room” as its proper name for the architectural project.

This is important to know because, in hospitals belonging to religious orders, it is most common to find chapels dedicated solely to that particular religion. In more flexible and lenient cases, such as the Orde Hospitalari de Sant Joan de Déu (Hospitaller Order of SJD), there was an ecumenical room, meaning a space for different Christian denominations. Proposing and offering a multireligious space that accommodates different religions and also atheists is innovative and bold. This hospital, internationally renowned for treating children from around the world, has thus prioritized the needs of the children and their families.

1.2. Needs of Each Religion

As Victorino Pérez Prieto explains (

Pérez Prieto 2011), architecture, or a certain type of architecture we would add, has a sacred function. While it is true that one can speak to God from anywhere, tradition has dictated that it is easier to do so from certain spaces legitimized by the value given by the community. Therefore, understanding the spatial and architectural needs of temples from each religion is essential to design a space that accommodates all.

The Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant churches, though born from the common Christian trunk, are very different. In contrast to the austerity of Protestant temples, due to their liturgical conception based almost exclusively on the Word, the Counter-Reformation created a different type of temple: the baroque, centered on the affirmation of Eucharistic, Marian dogmas and popular piety devotions, featuring a frontal altarpiece and numerous side chapels. This type of temple is now irrecoverable, not only due to changes in architectural tastes but also because the militant ecclesiological conception has been surpassed (

Pérez Prieto 2011). Nonetheless, the theological conceptions of Catholics, Protestants, and Orthodox lead to different liturgical concepts that condition their temples: Catholic churches need a presbytery with its altar for the Eucharist, the ambo for the Word, and the presidency, the place for the Eucharistic reserve; Orthodox churches need the sanctuary (altar place for the Eucharist, separated from the people) and the iconostasis (retable with panels for icons, separating the sanctuary); Protestant churches, in contrast, only need the place of the Word (for reading and preaching) and the place of the choir.

Besides Christian churches, the fundamental characteristics of sacred spaces of the main religions are as follows. Muslim mosques have fundamental elements: large courtyards combined with a central corridor for prayer and fountains for ablutions; towers (minarets) for the call to prayer; the wall (qibla) with its niche (mihrab), indicating the direction to Mecca, and the pulpit (minbar); and iwans to separate different sections of the mosque and geometric decoration with arabesques, Arabic calligraphy, instead of paintings (prohibited in Muslim architecture). Jewish synagogues have these elements: a cabinet or tabernacle at the back, with the ark containing the Torah scrolls; in front of it hangs a small lamp that constantly burns in memory of the perpetual light that shone in the Temple of Jerusalem; and the menorah and a lectern table (bimah) or a lectern (amud) placed on a platform (tebá) that acts as an altar for reading the Torah. These elements are present in old and new synagogues. Stupas, ancient Hindu funerary mounds with relics, considered in Buddhism to contain Buddha’s relics, were later used as funerary mounds for significant figures and became important pilgrimage sites. In Southeast Asia, China, and Japan, stupas transformed into pagodas, representing the Buddhist cosmos: a series of tiered structures ordered according to specific concepts or guidelines. Buddhist sacred places seek to be particularly meditation spaces, especially Zen spaces, on which contemporary architecture has focused more. Finally, Japanese Shinto shrines are very varied but have common elements; the most notable is the large entrance gate (torii) (

Figure 2).

We conclude this brief and straightforward synthesis, which aims to contextualize the issues that multireligious spaces seek to address in general, and specifically in our case study. For further information, refer to the various volumes of

The Encyclopedia of Religion, which accurately, extensively, and systematically document the needs of each religion (

Eliade and Adams 1987).

1.3. Paradigm Shift

Beyond the specific needs of each religion and the relationship between architecture and the sacred, a generalized trend shift is observed across continents where religion decreases and spirituality rises, leading to less use of large temples in favor of small multireligious spaces in public places (

Puttick 1997;

Crosbie 2017). Andrew Crompton of the University of Liverpool School of Architecture, one of the leading experts in this field, explains, based on statistical data from the Pew Research Center, that in the UK alone, there are estimated to be over 1500 multifaith spaces, with this number being much higher in the United States and Europe (

Crompton 2013). These spaces can be found in “non-places” (

Augé 1993), such as airports, shopping centers, and service stations, and also in public or private buildings such as hospitals, prisons, universities, schools, police stations, offices, and government buildings (

Johnson and Laurence 2012;

Díez De Velasco 2016).

Given the current state of the matter and the general topic in all its complexity, the aim of the present manuscript is to present an unpublished and exemplary case study, showcasing both the research conducted for the design of the multifaith room and the process of its construction and implementation.

2. Discussed Results

The results presented below are accompanied by the relevant discussion. Since this is not a statistical study or has data collection where it is easy, logical, and coherent to separate the raw results from the subsequent discussion, it seemed more appropriate for this study to present the discussed results to facilitate the manuscript’s readability.

2.1. General Design of a Multireligious Space

Architecturally speaking, the direct ancestors of the modern multifaith room are a few spaces shared by Christians and Jews dating from the middle of the last century, the oldest of which could be found in the United States Army before the Second World War. It is unlikely that they were created for religious reasons; making soldiers share may simply have been cheaper and better for morale than providing separate facilities (

Crompton 2013). Shared spaces in airports and schools followed in the 1950s and 1960s. Specifically, the first airport chapel dates to 1952, at The Our Lady of The Airways Chapel, at Boston Logan Airport. Initially Catholic, it became multireligious. From then until today, the number has grown exponentially. According to the

Wall Street Journal, referring to data from the International Association of Civil Aviation Chaplains, an ecumenical nonprofit organization, at least 140 airports worldwide have designated chapels, and more than 250 chaplains. The same goes for other public and private facilities cited, with hospitals having the longest tradition of housing them. However, it is also true that sometimes hospitals are precisely the most reluctant to convert it into a multireligious space, even detaching them, as in the case of our study’s hospital, from its founding religious order.

Thus, based on the conclusions of Crompton’s research team published in the cited article, and despite being a present design problem he describes as almost impossible to project, it ultimately seems that such a multireligious space functions somewhat better if it is a confined, empty, white space without symbols, enclosed, and without windows. However, we now ask ourselves: is there not a danger of falling into non-design and relegating these spaces to residual places within main spaces? Building a high-quality multireligious space has been our project objective. Presenting it here in an unprecedented way is the aim of this article.

2.2. Three Exemplary Multireligious Spaces

We have selected three relevant examples for us and for our case study. The reasons are as follows.

On a temporal level, they encompass the past, present, and future of multireligious spaces. The first example, the MIT Chapel, is the earliest successful and well-regarded space of this kind. The second example, Patriarca Abraham, represents the present in the city of Barcelona, the location of our case study. The third example, House of One, signifies the future, as it is a yet-to-be-constructed building that has sparked considerable debate about the nature of future multireligious spaces.

On a conceptual level, all three examples share common formal concepts that are worth highlighting and considering when designing such buildings. Firstly, the formalization of space using circular, elliptical, and concave shapes creates an environment that embraces and gathers the user. Secondly, the control of lighting and shadows creates an atmosphere of reflection and silence. Additionally, these buildings utilize materials in a way that the materials themselves serve as the primary ornamentation of the space, rendering additional decorative elements almost unnecessary. In relation to this point, while seemingly contradictory yet complementary, the present ornamentation is deliberately sculptural, focused, and material-based. Finally, all three examples emphasize verticality as the predominant spatial axis, which contrasts with and complements the horizontality of the ground plane.

On a vocational level, the authors of the three projects emphasize spirituality over religion when describing their work, a factor that contributes to the success of such buildings.

For all these reasons, among the many multireligious buildings constructed and unconstructed worldwide, these three have been chosen to accompany and justify the design decisions made in the case study of the Silent Space at the PCCB of SJD Hospital.

2.2.1. Paradigmatic Example from the Past: MIT Chapel

The first successful multireligious chapel of reference (because there were earlier examples that did not succeed and even failed) is the Interfaith Chapel designed by Eero Saarinen, built on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) campus in 1955 (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). According to contemporary chronicles collected in Jeanne Halgren Kilde’s latest article (

Kilde 2024), its success is due to the unique conviction that the most important aspect of “religion” was not identification with a particular tradition or engagement in a particular worship practice, but the widely shared human experience of “spirituality”.

To put the reader in context, in the 1950s, the US national ethic, heavily influenced by the Cold War and opposition to communism, prompted MIT leaders to consider building a chapel, thus reflecting a commitment to non-materialistic values. The predominantly secular and scientific institution actively participated in the war effort during World War II and became a significant defense contractor (

Leslie 1993). To counterbalance this and address incidents such as the arrest of a former student for espionage and academic controversies, they saw the need to also attend to the moral and religious development of students (

Giraud 2014;

Buckley 1951).

The Dean of Students at the time, Everett Moore Baker, advocated for a personal approach to religion and the creation of a space for religious reflection, promoting an inclusive understanding of faith that aligned with science (

Baker 1951). This approach sought to offer a counterbalance to the materialistic image of MIT, adapting to the emerging religious and ethical sensibilities in a context of secularization and pluralism. The chapel proposal reflected a progressive vision of religion as a compatible and enriching element of scientific education, evidenced by an international conference at MIT highlighting interest in the social implications of scientific progress and the relationship between science and faith, attracting a large audience (

Burchard 1950). This shift towards a more inclusive understanding of religious life marked an effort by the institution to address the ethical and spiritual concerns of its community at a time when national narratives emphasized religion as an antidote to communism.

Eero Saarinen’s innovative approach to designing the MIT Chapel reflected this conceptual shift towards a universal understanding of religious experience, moving away from traditional divisions among different religious practices. This shift was articulated through the chapel’s design as a space intended for individual experience of transcendence, beyond sectarian differences, which was a novel idea at the time (

Saarinen Challenges the Rectangle 1953).

Saarinen’s description of the design reflected a deep contemplation on how the physical environment of the chapel could evoke a state of spiritual reflection, inspired by personal experiences capturing the essence of transcendence and immanence (

Smith 1962). The resulting design emphasized elements that invite introspection and contemplation, such as the dim lighting suggesting a “sacred and enclosed darkness” (

Thomas 1954) and architectural elements resonating with both life and death, symbolized by the building’s cylindrical shape and its exterior blind arches.

The chapel’s integration into campus life and its acceptance as a personal reflection space for individuals of all beliefs is as evidenced by the diversity of religious services and meditation activities it hosted after its opening. The space’s management reflected this inclusive philosophy, offering services for a wide range of religious traditions and dedicated times for private meditation, highlighting the success of Saarinen’s design in facilitating a multireligious and multifunctional space (

Killian 1985).

This focus on individual personal and spiritual experience rather than group worship practices marked a significant shift in the conception of religious spaces, allowing the MIT Chapel to serve as a model for future architectural developments in multireligious spaces, both in academic and public settings.

2.2.2. Example of the Present from Barcelona: Patriarch Abraham

Another noteworthy example, being the first of many, is the multireligious temple constructed for the first time for the celebration of the Olympic Games (

Arboix-Alió 2016). In Barcelona, in 1992, it was unprecedented for such a sporting event to decide on building a structure that allowed various religious practices for athletes from around the world participating in the Olympics (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

It is a sculptural building with a unique vocation that takes the dedication of Abraham, the common patriarch of the three major monotheistic religions of the Christian confessions (Christianity, Islam, and Judaism). After the games, it transitioned to a parish of the new neighborhood. While this might seem like a failure, this adaptability speaks to the success and flexibility of the proposal. In reality, many cited multireligious spaces start as spaces for one religion and transform into spaces for multiple religions, and vice versa: spaces initially designed to accommodate religious diversity for a specific event transition to serving the religious community that remains in that place.

The building, designed by architects Josep Benedito and Agustí Mateos, has evident and reiterated symbolism. The shape of the complex is that of a large fish, recalling the maritime memory of the area and alluding to the ancient Christian symbol representing Jesus. The temple itself is located in the “body” part, elliptically shaped, with the “tail” for parish dependencies, which today is practically empty due to its oversized dimensions. The worship space is illuminated by glassed-in accesses and the ceiling, covered by beams and wooden ribs arranged as if it were the belly of a ship. The main access is through a grand staircase and an atrium, leading to the entrance porch under the church choir. The floor plan is symmetrical, with another more frequented access on a higher street level (

Arboix-Alió 2018).

However, beyond the church itself, this is a paradigmatic case of how a church and a city are built simultaneously, with the former being the unique building marking a new neighborhood and a new urban fragment (

Arboix-Alió et al. 2023). The project on paper and the church’s construction with the urban fragment go hand in hand in this case, as a result of a special event, the celebration of the Olympic Games. This social and multitudinous celebration drives the urbanization of an entire city sector, with the sacred building as its distinguishing feature. In commemoration of the sporting event, and to host athletes, technical teams, and their families who moved to Barcelona, the Olympic Village neighborhood was constructed, and the Patriarch Abraham temple was built as a symbolic monument. The city sported a complex design and subsequent transformation into a residential neighborhood, undertaken by the team of Josep Mª Martorell, Oriol Bohigas, David Mackay, and Albert Puigdomènech, incorporating projects from architects and urban planners who have won FAD awards.

2.2.3. Future Example: First Multireligious Center in the World: House of One

As Tom Wilkinson explains, “Berlin has an unhappy history when it comes to accommodating non-Christian religions, and the rest of Europe is treating synagogues and mosques in a way that balefully echoes this past. So, what better place to set an example of a more positive interaction between adherents of different faiths than on the site of a church that was burnt by the SS and demolished following the Second World War—and which, itself, stood on the site of Berlin’s first medieval church?” (

Wilkinson 2016).

The idea of replacing it with a more inclusive facility was first conceived by the church authorities in 2008; Kühn Malvezzi won an international design competition in 2012. The projected building consists of three separate spaces grouped around a towering central volume, which permits “unity in diversity”: the Jewish element is a lozenge, the Islamic element square, and the Christian rectangular. The first two are equipped with galleries to permit gender segregation; the Islamic space has ablution facilities; and the Christian space has an organ. Rather than simply expressing a hope that proximity will breed amity, the central zone will be used to host events that encourage interaction. Funds are being raised to begin construction. Still today, then, religion has an important place in defining the image of cities (

Deibl 2020).

To realize this project, EUR 43.5 million are needed, and anyone can contribute, even by buying a single brick online for EUR 10. This type of collective sponsorship, similar to other projects funded through crowdfunding, finds its similarities precisely in expiatory temples, where believers paid money to be absolved of their sins and contribute to the temple’s construction and maintenance. It is, in reality, a unique experiment in the world. We are talking about a worship building—church, synagogue, mosque—where Christians, Jews, and Muslims can pray in Berlin. They agreed that construction would begin once the first EUR 10 million were raised. Thanks to the success of individual donations and sponsors’ support, the foundation stone ceremony could be held in 2021. It took place at Petriplatz, in the southern part of the Museum Island, where the medieval settlement of Cölln developed, eventually joined to Berlin in the 18th century. The building has been named “The House of One”, implying that it will be the house of humanity, not just those who believe in one God. The international competition was won two years ago by an architectural firm founded by Germans Wilfried and Johannes Kühn and Italian Simona Malvezzi. They designed this brick cube dominated by a tower, whose structure satisfies and certainly was not easy to reconcile the different needs of assembly and prayer of the faithful of three different religious confessions (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). It is a “peace project”, therefore, whose idea first emerged in 2009 by a Berlin evangelical pastor, Gregor Hohberg. Today, his two adventure companions are liberal rabbi Tovia Ben-Chorin from Abraham-Geiger-Kolleg, and imam Kadir Sanci, belonging to a Turkish organization in Germany, the Forum for Intercultural Dialogue, which refers to preacher Fethullah Gülen, a major opponent of Ankara’s head of government, Tayyip Erdogan. Hohberg recounted that a few years ago, while archaeological excavations at Petriplatz unearthed fragments of a distant past, including remains of five churches (one dating back to 1200), it seemed the right place to do something “visionary”, looking towards the future, inspired by brotherhood, dialogue, and mutual respect.

However, even the world’s first multireligious center ultimately proposes separating spaces according to confessions. Is it not an intelligent way to combat aseptic spaces while minimizing construction and maintenance costs?

In any case, our project goal has been to take everything that seems to work correctly in the cited three interreligious chapels and apply it to a space within the PCCB at the SJD Hospital. Thus, despite not constructing an isolated building nor exclusively a sacred building, because our Multireligious Space is placed within the interior of a hospital, we aim to demonstrate that quality design is possible. This approach could be extrapolated to any other public or private building of public concurrence that needs to offer a space for reflection linked to individual spirituality, moving away from the aseptic rooms proliferating everywhere in recent decades (

Sitte [1889] 1980). From now on, thanks to the Multifaith Room at PCCB at HSJD, hospitals, airports, shopping centers, schools, and universities have another contemporary example to inspire and hopefully improve, contributing to strengthening ties between research and applied research.

2.3. Design of the Multireligious Space at PCCB of SJD Hospital

2.3.1. What Is the PCCB?

The Pediatric Cancer Center of Barcelona is a center focused on pediatric cancer within the Sant Joan de Déu Hospital in Barcelona (SJD). AM, the center’s care director, in an unplanned conversation, defined it as a starting point for an international network of centers specializing in the cure, care, and research of cancer in children. It is a pioneering center in Europe, based on four objectives: (1) increasing cancer cure capacity by offering comprehensive and personalized care, (2) achieving new effective treatments for currently incurable cancers, (3) reducing the sequelae of surviving children, and (4) being an open-to-the-world center with a service vocation. This is defined in its strategic plan explained below. The need to create a specialized pediatric center becomes evident due to the 47% growth of new children treated between 2017 and 2022 according to the center’s data. In fact, they estimate a 40% growth rate in recent years. This rate has a higher increase due to international admissions, 35%, a key aspect for the project presented in this article. The more international patients with diverse religions we have, the greater the need for a welcoming multireligious space to support families through the difficult times of illness or the death of young children.

Regarding the city, the PCCB is located northeast of the city, bordered by the Collserola natural park, an interstice between the city and nature (

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10).

2.3.2. Functional Plan of PCCB

The functional plan of the project is structured on the generic model of user-centered design (

Mao et al. 2005) and a specific approach of the 4Ps: Play, Parents, Pain-free, Professionals. These outline the incorporation of gamification in processes, constant engagements with companions and family members, humanities as a pillar of the atmosphere, and constant involvement of professionals. It is a functional plan resulting from a co-design process, with a social impact viewpoint (

Hospitecnia 2022), in which different user groups inhabiting the hospital and its surroundings participated.

The result of this process proposes the rehabilitation of the old teaching building and the incorporation of a new building, which will allocate 70% of its space to healthcare facilities and the remaining 30% to research and development. The new center has 37 single rooms, 8 transplant rooms, 26 day hospital boxes, and 21 outpatient consultations. It also houses a Nuclear Medicine and Metabolic Therapy service; operating rooms; oncology research laboratories; and other healthcare services (

Hospitecnia 2022). There is also a set of social spaces, promoting shared knowledge among all involved in the project, such as playrooms, hospitality environments, and “Family Lounges.”

The PCCB opened its doors in June 2022 and is currently implementing its 2023–2027 strategic plan. This plan emphasizes the hospital network and internationalization. This internationalization consequently requires multiculturalism to be addressed from a humanistic and care perspective proposed by its values. From the relational knowledge of the participative context of the families, the need arose for a space for meditation and reflection for families, companions, and all those who need it, whether from the hospital community or the city, a 24/7 public access space. This space will become a multireligious space in a hospital of the Christian Order of Saint John of God, coexisting with the existing chapel in the Hospitalization building designed by Clotet Llongueras Architects.

2.3.3. Design of the Multireligious Space at PCCB

Under the title “Silent Space”, this multireligious space was proposed in the fourth month of 2023, as a result of the aforementioned precedents and on the initiative of the SJD infrastructure department, led by Albert Bota and its Managing Director Manel del Castillo.

The starting point is for the architecture and design team, OVICUO, and two members of the Design Research Group from the University of Barcelona—the authors of the current article—to develop a proposal for a multifaith and non-religious public space for the PCCB (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12).

This entails understanding culture as something beyond knowledge, seen as something learned, repeated, and transferred. Thus, the habit of meditation opens the service to people who may require it. If meditation becomes a habit, it can be considered a salutogenic service for the community. Habit as an element of repetition and sequence as a ritual. A set of actions repeated sequentially to achieve a result. The word Ritual etymologically comes from the Latin “ritualis”, belonging to the rite. In Roman usage, in legal and religious terms, “ritus” was the proven way of doing something, generating habit. Some authors show clear concern about their disappearance and homogenization (

Han 2020).

To carry out a ritual of habit that generates culture, a place is necessary. The space must become a non-place of the public, a space that must be appropriated by the people who use it, a neutral space that allows for adaptation by its users, and a minimal space isolated from interferences. The fewer interpretable symbolic features, the greater the possibility of adaptation. The Silent Space should be a simplified environment of connection with everything, as Harman explains in his book on the quadruple object, an ontological relationship between objects, understood here as agents (

Harman 2016).

Based on the examples and bibliographic references presented, the proposed project is based on the following guiding concepts.

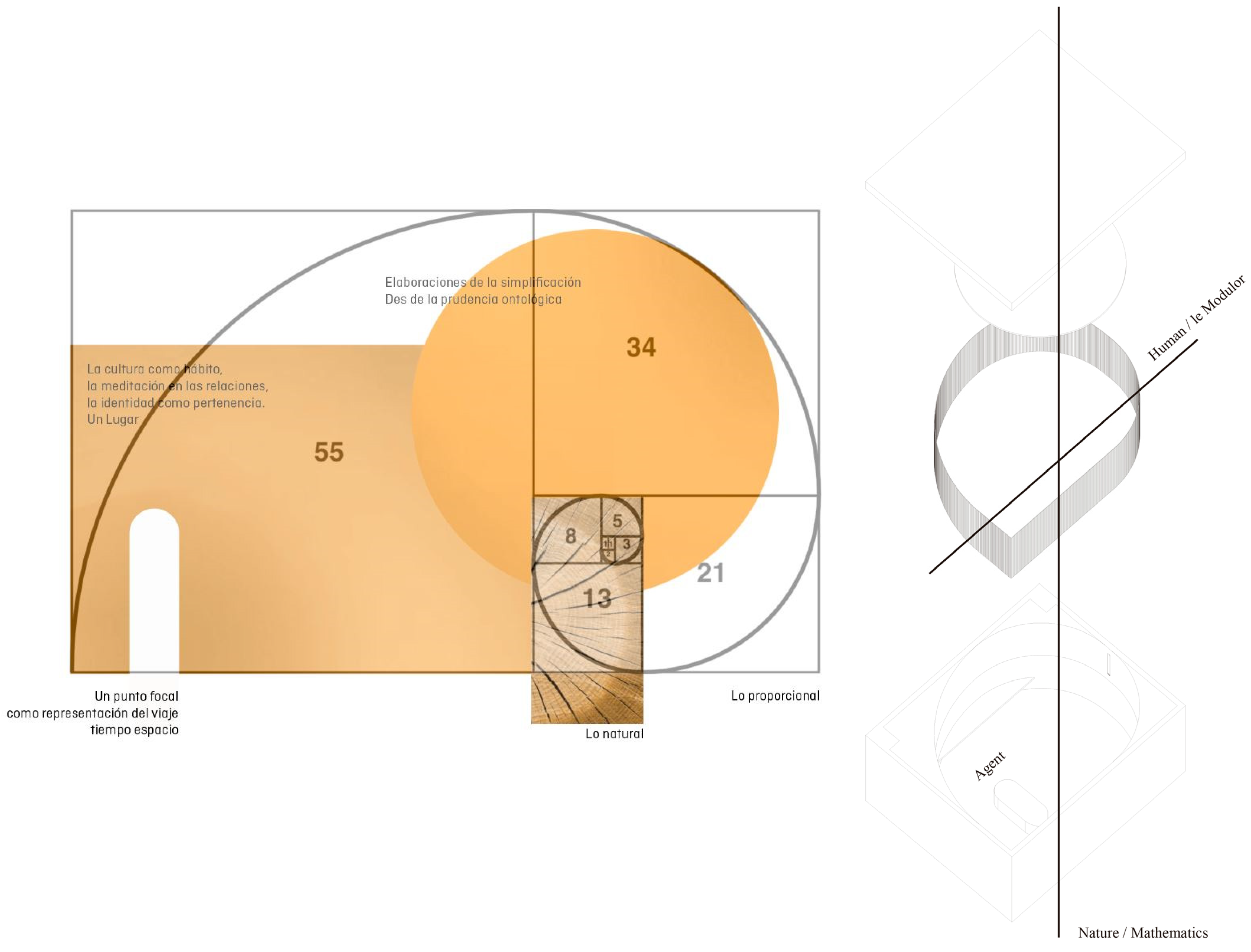

To establish this ontological connection between the physical and the non-physical, the space is based on axes (

Figure 13). The vertical axis seeks to unite the tangible and intangible, materialized by a warm circular zenithal light creating a weightless atmosphere. The horizontal axis finds its place in an architectural plan responding to a golden rectangle that the user cannot directly perceive but harmonizes the space proportions. Both axes converge as the space limits generate a spiral culminating in an empty center where the user is placed. Additionally, if the plan proportions relate to the golden number, the vertical proportions relate to those proposed by Le Corbusier in “Le Modulor”, a set of proportions related to the human. Thus, nature and human, tangible and intangible, juxtapose like a fabric. “On the basis of the size of the statistical median of human size, Le Corbusier determined a series of measurements, meant to define the proportions of building components, of entire structures, as well as of graphic layouts” (

Cohen 2014). Symbolically, it presents the constant relationship between nature and artifice, evidently being a designed and artificial space (

Aicher 1994). Nature is expressed through the natural wood perimeter and natural cut sandstone on three sides, situated in the center horizontal space.

Lighting plays a fundamental role in this project, as seen in the project image. There are three types of lights perfectly designed to give the atmosphere the space needs: the focal point, the horizon, and the zenith. The focal point is an illuminated vertical shaft allowing for an infinite focal point. The horizon appears as a continuous line embracing the user. Finally, on the zenith plane, a soft light appears as if an oculus were in the upper plane. The scenic solutions are adaptable to each user and combinable with each other.

The space provides isolation for the person to focus on their meditation. Once inside, the space’s continuity is constant, integrating the exit to some extent. The lighting adapts in terms of intensity and acoustics with different melodies specifically composed by SJD under the title “Sons del Silenci” (in Catalan meaning Sounds of Silence). Temperature, light, smell, and acoustics relate to generating the particular weightless atmosphere of the Silent Space. Additionally, without detailing further, as it is not the study’s objective to delve more into the project process, some parameters worked by Zumthor (

Zumthor 2006) were used in creating the atmosphere.

The construction of the multireligious space began on 13 December 2023, with the conditioning of a pre-existing office and the use of part of the common area in the building’s access lobby (

Figure 14). The construction period took three months, with the faculty team conducting weekly site visits alongside the working teams and the property. The Silent Space organically opened to the public on 1 March 2024, becoming a community service space that is open and accessible to the public, a “non-place” for community connection and a public space. It aims to provide a warm and welcoming environment, contrasting with the minimalist white room previously offered and currently maintained.

At this point in the article, we advocate for designing new multireligious spaces in hospitals, airports, schools, universities, and shopping centers with this sensitivity, drawing from the best examples. The recently inaugurated multireligious chapel at PCCB of SJD serves as an example of this approach and helps us avoid cold, white, and impersonal rooms. These rooms, under the argument of not wanting to symbolize any particular religion to include all of them, actually fail to address the design of a space that should offer retreat, peace, and reflection to any user in need (

Figure 15).

2.4. Limitations and Future Perspectives

SJD Hospital now has two multireligious spaces: the recently inaugurated study object room designed following the explained parameters and the cold minimalist white room. A future research direction would be to conduct a statistical study to quantitatively measure the time and intensity of use of each space, as well as a sociological and ethnographic study to qualitatively assess user satisfaction and comfort in each space.

Another limitation of this study would be the need to visit the reference examples to broaden the theoretical knowledge of these spaces beyond paper consultation and bibliographic search, incorporating a lived experience of the projected atmospheres.

3. Materials and Methods: Methodology

The methodology undertaken for the research is primarily based on three pillars: a literature review, an analysis of architectural design projects structured along a temporal axis, and a series of in-depth interviews. These processes are complemented by the project methodology inherent to design, which is based on a systematic structure proposed by Professor Bruce Archer (

Archer 1963–1964).

This methodology adapts to the particular context of spatial design, understanding space as an object of interaction with people. Archer’s sequential scheme has been carried out in the form of a black box (

Jones 1978). Jones differentiates between a transparent box and a black box in relation to the uncertainty present in design decision-making, where context and time play a modifying role. Consequently, the same project will undoubtedly yield different results over time. Archer advocates for a structured follow-up of the project without the necessity of presenting results in a fragmented manner.

Archer proposes the following systematic structure and its iterations:

Problem definition.

Data collection.

Analysis and synthesis of the data to prepare design proposals.

Prototype development.

Preparation of studies and experiments to validate the design.

Preparation of production documents.

In this case, due to budgetary and scale constraints, it was not possible to develop physical prototypes, but five visual prototypes were created. Experimental studies based on these prototypes were conducted to validate the model to be implemented. An example of this is the iteration in the decision-making process for the bench, initially proposed in wood and later incorporating natural cut stone.

Regarding the research methods, the literature review consulted is shared in this article and serves to develop an analysis of the contextual and theoretical framework. The analysis of architectural projects structured along a temporal axis (past–present–future: (a) the first documented multi-religious hall project, (b) a contemporary and notable project in the city of Barcelona, and (c) a proposed project for the near future) allowed for the extraction of essential typological characteristics (

Moneo 1978) of multi-religious spaces: natural lighting, vertical focal point, horizontal focal point, nature, and artifice. Therefore, the set of essential characteristics and their combination are applied to the project (

Martí i Font 1999). The typological grouping and combination of types is one of the introductory methodologies to design research (

Figure 16).

To determine the exact needs of the multi-religious space, data were collected through conversations, also considered knowledge generators (

Mengis and Eppler 2008). Social conversations with families, companions, and professionals were facilitated by the General Director of Infrastructure, a consistent relational profile in the development of the research. Additionally, scheduled interviews were conducted with JBC, a brother of the Order of Sant Joan de Déu and representative of the Curia, and the chaplain of SJD responsible for organizing Christian ceremonies, Brother MM. These interviews emphasized the value of inclusion and respect for multiculturalism, a principle that the future Silent Space in the PCCB must undoubtedly uphold. These interviews also suggested the possibility of adding a focal point in the form of a shelf to place various symbolic objects, such as a cross for Christian users. In phase 5 (preparation of studies and experiments to validate the design) of the sequential method proposed by

Archer (

1963–1964), the project is shared with the Medical Director and the General Director of SJD.

The methodology of ethnographic conversation will help the researchers to follow up on the project and the users’ perception of the space. This methodology also helps plan the future monitoring of the project. In this regard, once the silent room was inaugurated, feedback was collected from the purchasing director of SJD and some of the suppliers who visited the space privately and individually after the work was completed. As an observation, the researchers will visit the space periodically during the first year of use to detect possible implementable iterations. It is expected that in the future, interactions with a diverse range of users will be possible, allowing for a detailed study of the evolution of the proposal.

The combination of the literature review, temporal analysis, in-depth interviews, and systematic design methodology provides a robust framework for researching and designing multi-religious spaces. This approach ensures that the design is informed by historical context, contemporary practices, stakeholder needs, and validated through experimental studies, ultimately leading to a well-rounded and inclusive design solution

4. Conclusions

The integration of a multifaith room within the Pediatric Cancer Center Barcelona (PCCB) at Sant Joan de Déu Hospital represents a significant advancement in the design and utilization of hospital spaces. This initiative aligns with contemporary trends emphasizing the importance of creating inclusive, spiritually accommodating environments in healthcare settings. Through this study, we have detailed the research, design process, and implementation of this pioneering space, highlighting its innovative approach and relevance.

The PCCB serves a diverse international patient population, underscoring the necessity for a space that accommodates various religious and spiritual needs. Traditional hospital chapels often cater to a single religious denomination or, at most, multiple Christian denominations. By contrast, the multifaith room at PCCB breaks new ground by welcoming individuals of all faiths and those without religious affiliation, offering a sanctuary for meditation and reflection. This inclusivity not only meets the spiritual needs of a diverse patient base but also aligns with broader societal shifts towards greater acceptance and understanding of multiculturalism.

The design of the multifaith room draws from historical and contemporary examples, such as the MIT Chapel, Patriarca Abraham, and the House of One. These spaces share common design elements, including the use of circular, elliptical, and concave forms that foster an embracing and contemplative environment. The careful manipulation of light and shadow enhances the room’s atmosphere, creating a tranquil and introspective space. Material choices serve as inherent ornamentation, reducing the need for additional decorative elements and emphasizing the space’s simplicity and purity.

The design incorporates philosophical insights from thinkers like Heidegger and Harman, too. By considering both the ontological relationships between objects and the holistic interconnectivity of all elements, the multifaith room embodies a space where the tangible and intangible, nature and human artifice, converge harmoniously. This approach not only respects the diverse spiritual practices of its users but also elevates the space beyond mere functionality to a profound expression of universal spirituality.

It also represents Heidegger’s fourfold: earth, sky, gods, mortals (

Harman 2016, p. 89). This is almost literally true with the stone, skylight, place to sit, and the spiritual atmosphere. In the spirit of Object-Oriented Ontology, objects such as this space do not just respond to a brief in a passive way but interact with users in ways that are quite unpredictable, as if the space possesses a life and intentions of its own.

The construction of the multifaith room within a hospital setting, particularly one managed by a religious order, demonstrates a progressive commitment to meeting contemporary spiritual needs. The collaborative efforts between the design team and hospital administration ensured that the space would be both functional and welcoming. This project exemplifies how thoughtful design can transform hospital environments, contributing to the overall well-being of patients and their families during challenging times.

Moreover, the inclusion of this space in the PCCB highlights the hospital’s dedication to holistic care. By addressing not only the physical but also the emotional and spiritual needs of patients and their families, the hospital reinforces its role as a leader in pediatric healthcare. This approach aligns with current healthcare trends that emphasize patient-centered care, recognizing the importance of supporting all aspects of a patient’s experience.

The establishment of the multifaith room sets a precedent for future developments in hospital design. It serves as a model for other institutions seeking to create inclusive and spiritually supportive environments. Future research could involve longitudinal studies to assess the impact of such spaces on patient and family well-being, providing empirical evidence to support the continued evolution of hospital design.

In conclusion, the multifaith room at the Pediatric Cancer Center Barcelona represents a forward-thinking approach to hospital design. It addresses the spiritual needs of a diverse patient population, integrates philosophical and architectural insights, and exemplifies the potential for healthcare spaces to contribute positively to patient care. This project not only enhances the PCCB’s reputation as a leading medical institution but also offers valuable lessons for the broader field of healthcare design. The triad of “religion”, “public space”, and “society” makes more sense here than ever before.

Author Contributions

Both authors, A.A.-A. and O.V.R., have participated in all phases: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

This project would not have been possible without the collaboration of the SJD work teams. We would like to express our special thanks to Albert Bota, Antonio Reche, Salvador Casablancas, and Andrea Navarro for their trust, effort, and dedication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aicher, Otl. 1994. El Mundo Como Proyecto. Barcelona: GG. [Google Scholar]

- Arboix-Alió, Alba. 2016. Church and City. The Role of Parish Temples in the Construction of Barcelona. Ph.D. thesis, UPCCommons, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Arboix-Alió, Alba. 2018. Barcelona, Esglésies i Construcció de la ciutat. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Arboix-Alió, Alba, Josep Maria Pons-Poblet, Adrià Arboix, and Jordi Arboix-Alió. 2023. Relevance of Catholic Parish Churches in Public Space in Barcelona: Historical Analysis and Future Perspectives. Buildings 13: 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, L. Bruce. Systematic method for designers: Part one: Aesthetics and logic (Design 172. April 1963. 46–49); Part two: Design and system (Design 174. June 1963. 70–74); Part three: Getting the brief (Design 176. August 1963. 52–57); Part four: Examining the evidence (Design 179. November 1963. 68–72); Part five: The creative leap (Design 181. January 1964. 50–52); Part six: The donkey work (Design 185. May 1964. 60–63); Part seven: The final steps (Design 188. August1964. 56–59). All These Issues of the Magazine were Edited by John E. Blake. 1963–1964.

- Augé, Marc. 1993. Los No-Lugares, Espacios del Anonimato: Una Antropología de la Sobremodernidad. Barcelona: Gedisa. ISBN 8474324599. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Everett Moore. 1951. Baccalaureate Address. Dartmouth College, June 12, 1949. In Everett Moore Baker, August 28, 1901–August 31, 1950. Edited by Corliss Lamont. New York: Privately Printed, pp. 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Biddington, Terry. 2013. Towards a Theological Reading of Multifaith Spaces. International Journal of Public Theology 7: 315–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddington, Terry. 2021. Multyfaith Spaces. History, Development, Design and Practice. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, William F., Jr. 1951. God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom”. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company. [Google Scholar]

- Burchard, John Ely, ed. 1950. Mid-Century: The Social Implications of Scientific Progress. Cambridge, MA: The Technology Press of MIT and John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jean-Louis. 2014. Le Corbusier’s Modulor and the Debate on Proportion in France. Architectural Histories 2: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Crompton, Andrew. 2013. The architecture of multifaith spaces: God leaves the building. The Journal of Architecture 18: 474–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, Michael J. 2017. Defining the Sacred. Actas del Congreso Internacional de Arquitectura Religiosa Contemporánea 5: 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deibl, Jakob Helmut. 2020. Sacred Architecture and Public Space under the Conditions of a New Visibility of Religion. Religions 11: 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez De Velasco, Francisco. 2016. Multi-belief/Multi-faith spaces: Theoretical proposals for a neutral and operational design. In Multireligious Society. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea, and Charles J. Adams, eds. 1987. The Encyclopedia of Religion. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Giraud, Yann. 2014. Negotiating the ‘Middle-of-the-Road’ Position: Paul Samuelson, MIT, and the Politics of Textbook Writing, 1945–1955. History of Political Economy 46: 134–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Byung-Chul. 2020. La desaparición de los rituales: Una topología del presente. Barcelona: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, Graham. 2016. El objeto cuádruple. Una metafísica de las cosas. Barcelona: Antrophos. [Google Scholar]

- Hic et Nunc. 2023. Eero Saarinen MIT Chapel. Available online: https://hicarquitectura.com/2023/08/eero-saarinen-mit-chapel/ (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Hospitecnia. 2022. SJD Pediatric Cancer Center Barcelona. HOSPITECNIA. Arquitectura, ingeniería y gestión hospitalaria y sanitaria. Revista online. Available online: https://hospitecnia.com/proyectos/sjd-pediatric-cancer-center-barcelona/ (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Johnson, Karla, and Peter Laurence. 2012. Multi-Faith Religious Spaces on College and University Campuses. Religion & Education 39: 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Christoipher. 1978. Métodos de Diseño. Barcelona: Costa Llibreter. [Google Scholar]

- Kilde, Jeanne Halgren. 2024. Creating the Multifaith Chapel, 1938–1955: Architecture and the Changing Understanding of “Religion”. Religions 15: 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killian, James R., Jr. 1985. The Education of a College President: A Memoir. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, Stuart W. 1993. The Cold War and American Science: The Military-Industrial-Academic Complex at MIT and Stanford. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Ji-Ye, Karel Vredenburg, Paul W. Smith, and Tom Carey. 2005. The state of User-Centered Design Practice. Communications of the ACM 48: 105–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí i Font, J. M. 1999. Introducció a la Metodologia del Disseny. Barcelona: Edicions Universitat de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Mengis, Jeanne, and Martin J. Eppler. 2008. Understanding and Managing Conversations from a Knowledge Perspective: An Analysis of the Roles and Rules of Face-to-face Conversations in Organizations. Organization Studies 29: 1287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneo, Rafael. 1978. On Typology. Oppositions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press: The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Prieto, Victorino. 2011. Espacios sagrados en el cristianismo y otras religiones. El necesario espacio sagrado interreligioso. Actas del Congreso Internacional de Arquitectura Religiosa Contemporánea 2: 92–97. Available online: https://doarch152spring2015.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/moneo_on-typology_oppositions.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- PINEARQ. 2023. SJD Pediatric Cancer Center Barcelona, un referente en la atención oncológica pediátrica. Available online: https://pinearq.es/blog-es/sjd-pediatric-cancer-center-barcelona-un-referente-en-la-atencion-oncologica-pediatrica/ (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Puttick, Elizabeth. 1997. A New Typology of Religion Based on Needs and Values. Journal of Beliefs & Values 18: 133–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1953. Saarinen Challenges the Rectangle. Architectural Forum 98: 126–33.

- Sitte, Camillo. 1980. Construcción de Ciudades Según Principios Artísticos. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili. First Published 1889: Der Städte-Bau nach seinen künstlerischen Grundsätzen. Wien, Köln and Weimar: Böhlaum. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Wilfred Cantwell. 1962. The Meaning and End of Religion: A New Approach to the Religious Traditions of Mankind. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Dylan. 1954. A Child’s Christmas in Wales. Norfolk: New Directions. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Tom. 2016. Typology: Multifaith. The Architectural Review. Available online: https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/typology/typology-multifaith (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Zumthor, Peter. 2006. Atmospheres: Architectural Environments. Surrounding Objects. Basel: Birkhäuser. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).