1. Introduction

Chinese intellectuals started to engage in Buddhist psychology in the early 20th century, a time when Western culture was greatly influencing the country. Early Chinese contributors to the study of Buddhist psychology included Zhang Taiyan 章太炎 (1869–1936), Xiong Shili 熊十力 (1885–1968), Xie Wuliang 謝無量 (1884–1964), Liang Qichao 梁啓超 (1873–1929), and Taixu 太虛 (1890–1947). Zhang Taiyan and Xiong Shili focused on the correlation between Buddhist Yogācāra philosophy and Western psychology, engaging in fragmented discussions on the subject. Xie Wuliang and Liang Qichao, on the other hand, categorized specific components of Buddhist doctrine that could be utilized as foundations for psychological thought, but they did not formulate a comprehensive theoretical framework for Buddhist psychology. Taixu frequently addressed Buddhist psychology in his lectures and publications, symbolizing the initial forays into Buddhist psychology within the Chinese Buddhist community. Following Taixu, Buddhists of the Wuchang School

1 devoted themselves to further discussions on Buddhist psychology. Key figures included Fafang 法舫 (1904–1951), Tang Dayuan 唐大圓 (1885–1941), Manzhi 滿智 (n.d.), Dayu 大愚 (n.d.), Zhang Huasheng 張化聲 (1880–?), Hong Lin 洪林 (1893–1952), and Shanyin 善因 (n.d.). The Wuchang Buddhist Academy 武昌佛學院 even offered courses related to psychology. Their efforts reflected the late Qing and Republican intellectuals’ acceptance and assimilation of Western thoughts.

As early as 1915, during his stay at Mount Putuo 普陀山, Taixu authored an article titled “

Jiaoyu xinjian” 教育新見 (New Views on Education), where he first introduced his concept of psychology: “If I were to write about psychology, I would divide it into four parts: the feelings of affection (

qinggan 情感), the cognition of affection (

qingshi 情識), the habits of affection (

qingxi 情習), and the nature of affection (

qingxing 情性), with affection as the essence.”

2 In 1925, Taixu gave a lecture at the Wuchang Buddhist Academy titled “

Fojiao xinlixue zhi yanjiu” 佛教心理學之研究 (Research on Buddhist Psychology), where he proposed a psychological theory centered on affection (

qing 情), reflection (

xiang 想), and wisdom (

zhi 智). Two years later, in January 1927, Taixu published “

Xingweixue yu xinlixue” 行為學與心理學 (Behaviorism and Psychology) in the journal

Haichao Yin 海潮音 (The Sound of the Tides). In this piece, he criticized traditional Western psychology for being “shallow and narrow” and explored why behaviorism should be separated from psychology, as well as its potential to enrich psychology. Although he listed subsection titles “Behaviorism and Sense-faculties-only Theory (

weigenlun 唯根論)” and “Behaviorism and Body-only Theory (

weishenlun 唯身論)”, he did not elaborate on these topics. Subsequently, in the same year, Taixu delivered a lecture at the Minnan Buddhist Academy 閩南佛學院, titled “

Xingweixue yu weigenlun ji weishenlun” 行為學與唯根論及唯身論 (Behaviorism, Sense-faculties-only Theory, and Body-only Theory), where he expounded the previously unexplored topics. In January 1928, Taixu published two articles titled “

Zai lun xinlixue yu xingweixue” 再論心理學與行為學 (Re-discussing Psychology and Behaviorism) and “

Lun Holt yishixue yu Fojiao” 論候爾特意識學與佛學 (On Edwin Holt (1873–1946)’s Consciousness Studies and Buddhism) in

Haichao Yin. These articles discussed the distinction and relationship between psychology and behaviorism from the perspective of “the human organic group” (人的有機團) and argued for the compatibility of Holt’s consciousness studies with Sense-faculties-only Theory in

Śūraṅgama-sūtra (

Lengyan jing 楞嚴經). In December 1930, Taixu published “

Foxue zhi xinli weisheng” 佛學之心理衛生 (Mental Health from a Buddhist Point of View) in

Haichao Yin, where he cited psychological theories on mental illness and treatment and introduced Buddhism’s basic views on mental illness, prevention, and treatment, as well as fundamental methods for cultivating and enhancing mental health. Additionally, Taixu delivered a lecture titled “

Xin zhi yanjiu” 心之研究 (Research on the Mind) at Qianchuan Middle School 前川中學 in Huangpi County 黃陂縣 in 1922 and a lecture titled “

Meng” 夢 (Dreams) at Xiamen University in 1932, both of which showcased his views on Buddhist psychology. Moreover, in Taixu’s various articles discussing the Consciousness-only School, there are also scattered thoughts and propositions on Buddhist psychology. Generally speaking, Taixu not only evaluated the prevalent psychological thoughts in China at the time but also, based on the theory of the Consciousness-only School, proposed his own Buddhist psychological claims.

This paper will introduce, analyze, and evaluate Taixu’s views on Buddhist psychology, encompassing his critique of Western psychology and the rationale behind his conviction that Buddhist psychology outshines it. According to him, while both Buddhist psychology and traditional psychology may at times explore the human mind in similar manners, Buddhist theories offer an extra layer that guides people towards Buddhist practice and enlightenment.

2. Affection, Reflection, and Wisdom: The Structure and Content of Taixu’s Buddhist Psychology

Taixu’s fundamental perspectives on Buddhist psychology are outlined in his work “Fojiao xinlixue zhi yanjiu”, in which he proposed a tripartite psychology based on Buddhist doctrine: psychology of affection, psychology of reflection, and psychology of wisdom, progressing from lower to higher states in sequence.

1. The psychology of affection: This refers to the psychological states emerging from the lives of ordinary beings bound by love. This state is associated with the living beings that result from diverse karmic rewards, and it revolves around the four delusions related to the Self: ignorance about the Self (

wochi 我癡), attachment to the Self (

wozhi 我執), arrogance about the Self (

woman 我慢), and Self-love (

woai 我愛), primarily involving the deluded consciousness (

monashi 末那識). 2. The psychology of reflection: This pertains to the pursuit of excellence and truth, characterized by dissatisfaction with one’s current life and aspiration for higher and distant ideals, or a lack of trust in illusory phenomena leading to the pursuit of truth. Examples include the desire to be reborn in heaven, the aspiration to be reborn in the Pure Land, and the cultivation of concentration and wisdom for worldly or transcendental purposes. This psychological aspect is predominantly governed by the functioning of the sixth consciousness. 3. The psychology of wisdom: This represents the authentic understanding of reality, characterized by the non-discriminative wisdom (

wufenbie zhi 無分別智) that directly perceives the true nature of all phenomena. At its core, it encompasses the pure aspect of the eighth consciousness, together with the five universal (

sarvatraga) mental properties (

caitasika-dharma), five occasional or particular (

viniyata) mental properties, and eleven wholesome (

kuśala) mental properties. 一、情的心理學。隨生系愛之為情,謂隨所生異熟報之生命,系縛愛著,以末那我痴、我執、我慢、我愛四惑為中心…二、想的心理學。慕勝求真之為想,或不滿意於現前之生活而別慕高遠,或不信任於幻眾之境界而推求真實,如希生天,願生淨土及修世出世之定慧等。此種心理以第六識之作用為最強…三、智的心理學。如實現知之為智,謂現證諸法實相之無分別智,即淨分之八識與五遍行、五別境、十一善心所為體。

3

Affection, reflection, and wisdom represent different levels of consciousness. Affection is characterized by attachment, reflection by contemplative inquiry, and wisdom by the realization of truth. In the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, beings are categorized based on the varying degrees of these three consciousness states. According to this classification, ghosts, animals, humans, devas, and initial-stage Bodhisattvas have not yet transcended affection. Their differentiation lies in the varying amounts of affection they possess. Humans, heavenly beings, and bodhisattvas have not yet detached from reflection, with the distinction partly based on the quantity of their reflection. Both bodhisattvas and buddhas possess wisdom, but the wisdom attained by buddhas is of the highest order.

Taixu interpreted the three psychological states based on the theory of four kinds of real states (tattva) in the Yogācārabhūmi-śāstra. This posits a hierarchy of four realities: The first level is the conventional real state, universally acknowledged within the mundane world. The second level is the real state established by the wise through the observation and discernment of phenomena. The third level is the real state obtained after removing the obstacles of delusions through pure wisdom. The fourth level is the real state obtained after removing the obstructions of worldly knowledge through pure wisdom. Taixu compared the psychological state of affection to the realm of the conventional real state, signifying it as the common consensus. He believed that comprehending this psychological state necessitates a profound analysis of the four delusions about the Self: ignorance about the Self, attachment to the Self, arrogance about the Self, and Self-love. It also requires the revelation of people’s internal clinging to the storehouse consciousness (ālaya-vijñāna) and the external reliance on the six sensory consciousnesses, as well as the corresponding mental properties, the characteristic part (xiangfen 相分 Skt: nimitta-bhāga) of form dharma (sefa 色法 Skt: rūpa), and the postulated existence (jiafa 假法) of states (fenwei 分位 Skt: avasthā). Reflection, in this context, is situated within the realm of the real state established by the wise through the observation and discernment of phenomena, exemplified by the pursuit of truth in philosophical and scientific pursuits. Reflection serves as the pivot from affection to wisdom. Wisdom corresponds to the latter two kinds of real states, namely, the highest reality ascertained through pure wisdom (ibid.).

Taixu believed that secular psychologists had seldom touched the psychological states of reflection and wisdom, and their exploration of affection lacked depth. Since affection is a predominant aspect of human mental experiences, Taixu placed greater emphasis on this aspect within his framework of Buddhist psychology. As previously mentioned, in his article “

Jiaoyu xinjian”, Taixu proposed a nuanced breakdown of affection: the feelings of affection, the cognition of affection, the habits of affection, and the nature of affection. In this article, he proceeded to provide further elaboration on these concepts:

The nature of affection is neither wholesome nor unwholesome, and the same applies to the feelings of affection. Those who accumulate and manifest good and evil are the habits of affection, and those who discern and uphold good and evil are the cognition of affection. Good and evil are not absent from feelings of affection (such as suffering, joy, sorrow, and happiness), yet they are subtle within them; those who manifest them are the habits of affection, and those who discern them are the cognition of affection, which discerns only what the habits have manifested. Good and evil are not unrooted in the nature of affection, yet within this nature, they are profoundly mysterious. Those who accumulate good and evil are the habits of affection, and those who cling are the cognition of affection, which clings only to what the habits have accumulated. 人之情性無善不善,人之情感亦無善不善也。著積善惡者,其情習,辨執善惡者,其情識。善惡非不含於情感 (若苦樂憂喜等),然在情感微乎其微; 著之者情習,而辨之者情識,情識之所辨,惟情習之所著也。善惡非不根於情性,然在情性,玄乎其玄。積之者情習,而執之者情識,情識之所執,惟情習之所積也。

4

“Jiaoyu xinjian” is an article on education, wherein Taixu expounded on the cultivation of individuals. His conceptualization of the four types of affections was not merely a theoretical discourse; rather, it set out to uncover intellectual resources for nurturing character by delving into psychological studies. Therefore, his discussion on affection emphasized the moral implications of psychological phenomena, with his analysis focusing on how to eradicate malevolence and foster benevolence within the human psyche. He believed that the feelings and nature of affection are neutral, neither inherently good nor evil. Or, more precisely, the good and evil in feelings and their nature are either too insignificant to mention or too profound to comprehend. It is the habitual tendencies and discriminative cognition of affection that bear moral significance in human conduct, with the former accumulating good and evil and the latter distinguishing and adhering to them.

In light of this understanding, Taixu’s article further advances the notion of cultivating good sentiments and developing personality by regulating these psychological states. Since the nature of affection is inherently neutral, one should not be attached to either good or evil. Yet, while goodness and evil may be rooted in its inherent nature, the key lies in directing the positive and suppressing the negative. By directing the positive elements and suppressing the adverse ones within the realms of the cognitions and habits of affection, one can effectively subdue the ill tendencies within the affection yet maintain the innate nature of affection intact.

Feelings of affection are neither good nor evil; however, when accompanied by detrimental habits of affection, they may manifest as confusion, dizziness, and a lack of clarity. The cognition of affection enables one to observe deeply, discern good from evil, steadfastly adhere to the good, and strive to eliminate evil. By fostering the good and eliminating the evil in the cognition and habits of affection, the feelings of cognition would subsequently become pure and good, too (ibid.).

In addition, in Taixu’s discussions on medical science, he delved into the analysis of psychological disorders. From a Buddhist perspective, he identified six fundamental afflictions (

kleśa)—stupidity (

mūḍhi), perspectivality (

dṛṣṭi), greed (

rāga), arrogance (

māna), hatred (

dveṣa), and doubt (

vicikitsā)—and twenty consequent afflictions (

upakleśa) such as anger (

krodha) and enmity (

upanāha). He posited that psychological illnesses stem from these six fundamental and twenty consequent afflictions. To counteract them and prevent psychological ailments, he advocated cultivating eleven wholesome mental properties—faith (

śraddhā), [inner] shame (

hrī), embarrassment (

apatrāpya), lack of greed (

alobha), lack of hatred (

adveṣa), lack of misconception (

amoha), diligence (

vīrya), serenity (

praśrabdhi), carefulness (

apramāda), equanimity (

upekṣa), and non-harmfulness (

ahiṃsā)—to counter the twenty-six afflictions. A state of psychological health is achieved when all neutral minds and mental properties transform into wholesome ones, and the indetermined mental properties, namely, remorse (

kaukṛtya), torpor (

middha), initial mental application (

vitarka), and subsequent discursive thought (

vicāra), cease to exist. This leads to the manifestation of twenty-one pure wholesome mental states, which align with the four types of wisdom—the Reflective Wisdom of the Great Mirror (

mahādarśana-

jñāna), the Synthetic Wisdom of Equality (

samatā-

jñāna), the Analytical Wisdom of Distinguishing Clear Vision (

pratyavekṣaṇā-

jñāna), and the Active Wisdom that Perfects Everything (

kṛtyānuṣṭhāna-

jñāna), representing the ultimate state of psychological health.

5It is worth noting that the “ultimate state of psychological health” mentioned by Taixu actually refers to perfect enlightenment or Buddhahood in Buddhist practice. According to Taixu, the most significant advantage of Buddhist psychology lies in its ability to lead to enlightenment—this will be further addressed in the last part of this paper. In fact, within the Buddhist discourse, the Dharma is often considered an exploration of the human mind, with the ultimate goal of these explorations being enlightenment. As Weihai 惟海 mentioned in his work

Wuyun xinli xue 五蘊心理學 (Pañca-skandha Psychology), Buddhist practice is essentially about cultivating the mind, which requires psychological knowledge and a thorough understanding of the psyche. Only with correct psychological knowledge can one “attain the Way” in practice, that is, achieve enlightenment and develop a perfect personality. Therefore, Weihai views the dependent origination of the five aggregates as the systematic knowledge of psychological functions and regards Śākyamuni Buddha as a psychologist who discovered the structure of psychological functions and the laws of dependent origination, thereby establishing the paradigm of Pañca-skandha Psychology (

Weihai 2006; “Notes on the Use of the Book”, p. 1; “Preface”, p. 1). It is believed by many scholars, including Western psychologists and Eastern Buddhist scholars, that the Western psychology does not offer a thorough resolution of mental problems but a temporary suspension of them. For example, Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961), an authoritative Western psychologist, considered the psychoanalytic psychotherapy a specific “Western” way to deal with—only repress, but not eliminate—mental afflictions, and he further claimed that the practice of “concentration through meditation (

dhyāna)” is the only way to eliminate afflictions.

6 Wu Rujun 吳汝鈞, a famous Chinese Buddhist scholar in our time, based on his comparative study of psychoanalysis and Yogācāra, opined that psychoanalysis is an empirical psychological science aimed at treating various psychological ailments such as depression and anxiety via technical methods. In contrast, Yogācāra is a religious practice that proposes methods to transform consciousness into wisdom, ultimately leading to enlightenment and liberation, and freeing individuals from all attachments, suffering, and afflictions (

Wu 2013, p. 114). In short, these Buddhist scholars, including Taixu, have constructed Buddhist psychology by following a path of “hermeneutics towards liberation”

7: all Buddhist interpretations of the world, with a sense of guiding cultivation, are ultimately directed towards human liberation.

Taixu’s formulation of Buddhist psychology exhibited several unique characteristics: First, it aligned with the Buddhist progressive path of cultivation, creating a hierarchical psychology where affection is at the base and wisdom is at the apex. According to Buddhist values, one should and can adjust the proportion of these three properties, reducing affection and gradually increasing wisdom, thereby achieving higher realms. Second, adhering to the Buddhist belief that mental activity holds paramount importance, Taixu’s psychological approach emphasized personal mental states over external behaviors, prioritizing introspection over behavioral study. Although affection is the lowest among the three, it dominates the psychology of the general populace as it resonates with the majority’s mental states. Lastly, Taixu’s psychological exploration was not merely an academic exercise; it is marked by a clear practical emphasis. He maintained that psychological studies serve to improve the overall psychological health of individuals, thereby promoting the nurturing of the human spirit and the development of character, with enlightenment as the ultimate goal.

3. “Sense-Faculties-Only Theory”: Taixu’s Critique and Reconstruction of Behaviorism

Taixu, in his idealized view of Buddhist psychology, critiqued the Western psychology of his time. He traced its origins to Christian studies of the Soul, followed by the Renaissance’s idealistic studies of mental phenomena, and subsequently, studies of consciousness. Initially, Western psychology emphasized the study of knowledge; later, philosophers such as Rousseau (1712–1778) emphasized studies of the sentiment, and further on, philosophers like Kant (1724–1804) and Schopenhauer (1788–1860) emphasized studies of the will. This led to the formation of a Western psychology centered on consciousness, focusing primarily on knowledge, affection, and will, which has become the traditional paradigm in Western psychology for over a century. Under this framework, Sigmund Freud (1856–1939)’s groundbreaking analysis of the subconscious took shape, elucidating intricate aspects of human behavior, including sleep patterns and certain instinctual reflexes in children and animals. His work extended to examining social consciousness, ethnic identity, and national psyche, providing insights into the collective psychological dynamics that underpin public mental states. By that time, the burgeoning of modern science and technology began to shape the methodologies of the humanities. Traditional psychological studies, which are primarily based on individual introspection, fell short of the scientific standard of objectivity, thereby paving the way for the development of various psychological experiential methods and, eventually, the emergence of behaviorist psychology. This new paradigm prioritized observation and eschewed relying on introspective materials, aligning itself with the rigorous methodologies of scientific research.

8After reviewing the history of Western psychology, Taixu labeled it as “shallow and narrow” and pointed out three major flaws:

First, in terms of the spiritual inquiry, the Soul initially researched in Western psychology mirrors the concept of

ātman (Self/Soul) in Indian philosophy, However, according to Buddhist doctrine, this entity is illusory and merely nominal. The general populace, clinging to this notion, mistakenly believes in the existence of an unchanged Self. Later explorations in Western psychology into idealism and consciousness only touched upon the sixth consciousness

9 and associated mental properties in the Yogācāra doctrine of the eight consciousnesses, leaving numerous gaps and inaccuracies.

10 The vast and profound realms of the human spirit, meticulously detailed in Yogācāra theory, are only fleetingly touched upon by Western psychology.

11Second, in terms of the subjects of study, Western psychology mainly focuses on the mental landscape of ordinary adults, neglecting the psychological realms of children and other sentient beings, as well as the mental states of sages and the wise. As previously mentioned, in the tripartite framework of psychology—affection, reflection, and wisdom—that Taixu proposed, the psychology of affection encompasses all known animals and potentially unknown ones; the psychology of reflection delves into the minds of practitioners across the three vehicles of Buddhism (śrāvaka, pratyekabuddha, and bodhisattva); and the psychology of wisdom examines the minds of arhats, pratyekabuddhas, and buddhas.

12Third, regarding research methodologies, Taixu held reservations about several prevalent Western schools, arguing that they perpetuated the inadequacies of scientific tradition by “constructing research systems based on analytical elements observed by predecessors, rather than starting from reality”,

13 and “adhering to one aspect while excluding the whole” (ibid., p. 237).

The view that Western psychology’s exploration of the human mind was far inferior to that of Buddhism was prevalent among Chinese intellectuals at the time. When attempting to argue for this point, they frequently drew on the eight-consciousness theory of Yogācāra Buddhism. A common perspective was that Western psychology only focused on the first six consciousnesses of humans, while neglecting the operations of the seventh and eighth consciousnesses, just like Taixu pointed out.

14 For instance, Liang Qichao claimed, “Those who study Western philosophy and psychology must also study the Abhidharma, for many of its discoveries have not yet been reached by Europeans and Americans” (

Liang 2001, p. 394). Tang Dayuan shared a similar view that if one wants to discuss true psychology, one ought to seek it in Eastern culture because of their intellectual achievements in exploring

ālayavijñāna (

Hammerstrom 2015, pp. 110–12). Additionally, Chinese intellectuals, including Taixu, also attempted to demonstrate that Yogācāra Buddhism could help address the challenges faced by contemporary psychology, for example, on the topic of instinct and memory.

15Aside from these general criticisms, Taixu’s critique of Western psychology was primarily focused on behaviorist psychology. In 1913, John B. Watson, a professor at Johns Hopkins University, published a paper titled “Psychology as a Behaviorist Views it” in

Psychological Review. He criticized Structuralism and Functionalism, considering their introspective methods inadequate. Watson argued that psychology should be “a purely objective experimental branch of natural science”, striving to “get a unitary scheme of animal response, recognizes no dividing line between man and brute” (

Watson 1913, p. 158). He claimed that psychological research should focus strictly on observable behaviors rather than subjective experiences such as consciousness. He declared that “The time seems to have come when psychology must discard all reference to consciousness; when it needs no longer delude itself into thinking that it is making mental states the object of observation” (

Watson 1913, p. 163).

This publication marked the emergence of the term “behaviorism”, which set itself apart from and often in opposition to traditional psychology. In 1914, Watson published his book Behavior, and in 1919, he released Psychology: from the Standpoint of a Behaviorist, garnering numerous followers and establishing behaviorism as a prominent school of thought in psychology at the time.

Behaviorists regard consciousness and introspection as subjective descriptions that cannot be objectively observed and experimented upon. Therefore, they deem these concepts as unknowable and advocate for their exclusion from psychological research. This perspective stands in contrast to Taixu’s understanding that “each has self-awareness and the ability to perceive others’ unique mental situations, which is what we call psychology”.

16 Taixu believed that the behaviorist approach essentially replaces psychology with behaviorism.

If one only considers those objective physical phenomena that can be perceived as knowable, while failing to recognize that psychological phenomena, which are both subjective and objective, are also knowable, and dismisses them as nonexistent; then this is akin to seeing images displayed by light but only acknowledging the existence of the images, while disregarding the light itself, failing to recognize the mutual manifestation of lights. Isn’t this madcap and foolish? 若惟以但可為客觀之色法為可知,而不知可兼為主客觀之心理亦可知,且撥之為無有;則如光中昭顯諸像謂惟有諸像而無光,不睹光光自昭互顯,非狂愚耶!

(ibid., p. 222)

He believes that the fundamental premise of behaviorist psychology, which deems behavior and the external world as “objective” and one’s own consciousness as “subjective”, categorizing it as either unknowable or even denying its existence outright, is flawed. From a Buddhist perspective, mind and mind properties—seventy-two in number—are both subjective and objective. Moreover, mind and mind properties are capable of self-cognizing; hence, they are knowable and can be treated as objective phenomena. Therefore, both mental phenomena (citta) and physical phenomena (rūpa) are knowable transient entities. Mental phenomena, as the knower, also serve as the objective objects of “knowing”. The difference lies in the fact that physical phenomena, being material in nature, are easily perceived, while mental phenomena are difficult to discern; similarly, in behavior, there are subtle and overt actions, with the former being elusive and the latter conspicuous. Individuals should pursue more advanced investigative approaches to attain knowledge, rather than settling for what is easily attainable.

Taixu classifies research methodologies into two distinct paradigms: the bottom-up approach and the top-down approach. The so-called “top” refers to metaphysical, abstract theories, while the “bottom” denotes tangible material phenomena. Taixu maintains that genuine scientists ought to confront reality directly, engaging in bottom-up research that begins with immediate sensory experiences and progressively uncovering the underlying abstract nature of material entities. He criticized the fact that many contemporary philosophers and scientists do not base their research frameworks on reality but instead merely plunder the analytical results of their predecessors as the foundation for their concepts. Behaviorist psychology has inherited this flawed approach, focusing only on the physical responses to stimuli and excluding other psychophysical phenomena, thereby overlooking the rich activities of the human mind and body.

17However, Taixu asserts that despite its various limitations, behaviorism has made significant contributions to the field of psychology in several ways. First, while previous theories on the mind–body relationship suggested that mental processes were determined by the brain or the heart, behaviorism considers that mental functions involve various reactive activities both inside and outside the body, which is closer to reality. Second, Indian Brahmanical philosophers and Western Christian philosophers often propose the existence of an eternal, unchanging Soul beyond the body and consciousness, while behaviorists reject the concept of the Soul and focus on explaining psychology through bodily activities. Third, prior to behaviorism, psychology focused only on the mind and consciousness, neglecting the first five consciousnesses associated with sensory activities, particularly bodily consciousness, as outlined in the Yogācāra doctrine of the eight consciousnesses. Behaviorist research, which interprets psychology through bodily functions such as muscle and secretion systems, has shed light on the significance of bodily consciousness. Additionally, its “stimulus-response” theory also aligns with the Yogācāra theory that the first five consciousnesses are activated through contact with sensory objects. Fourth, previous Western psychology has rarely explored the deluded consciousness (kliṣṭamāno-vijñāna) and the storehouse consciousness; although Freud’s theory of the subconscious and the Vitalism’s notion of entelechy have touched upon these, they only scratched the surface. In contrast, behaviorism, through comprehensive observation and experimentation on both the body and mind of an organism, has gradually uncovered the subtle and hidden activities of the storehouse consciousness.

In light of the merits and limitations of behaviorism, Taixu advocates for its separation from traditional psychology to create a unique academic discipline. He envisions behaviorism as a standalone discipline, on par with physics, physiology, psychology, and ethics. To this end, Taixu outlines a multifaceted approach to the study of behaviorism, encompassing the following disciplines in

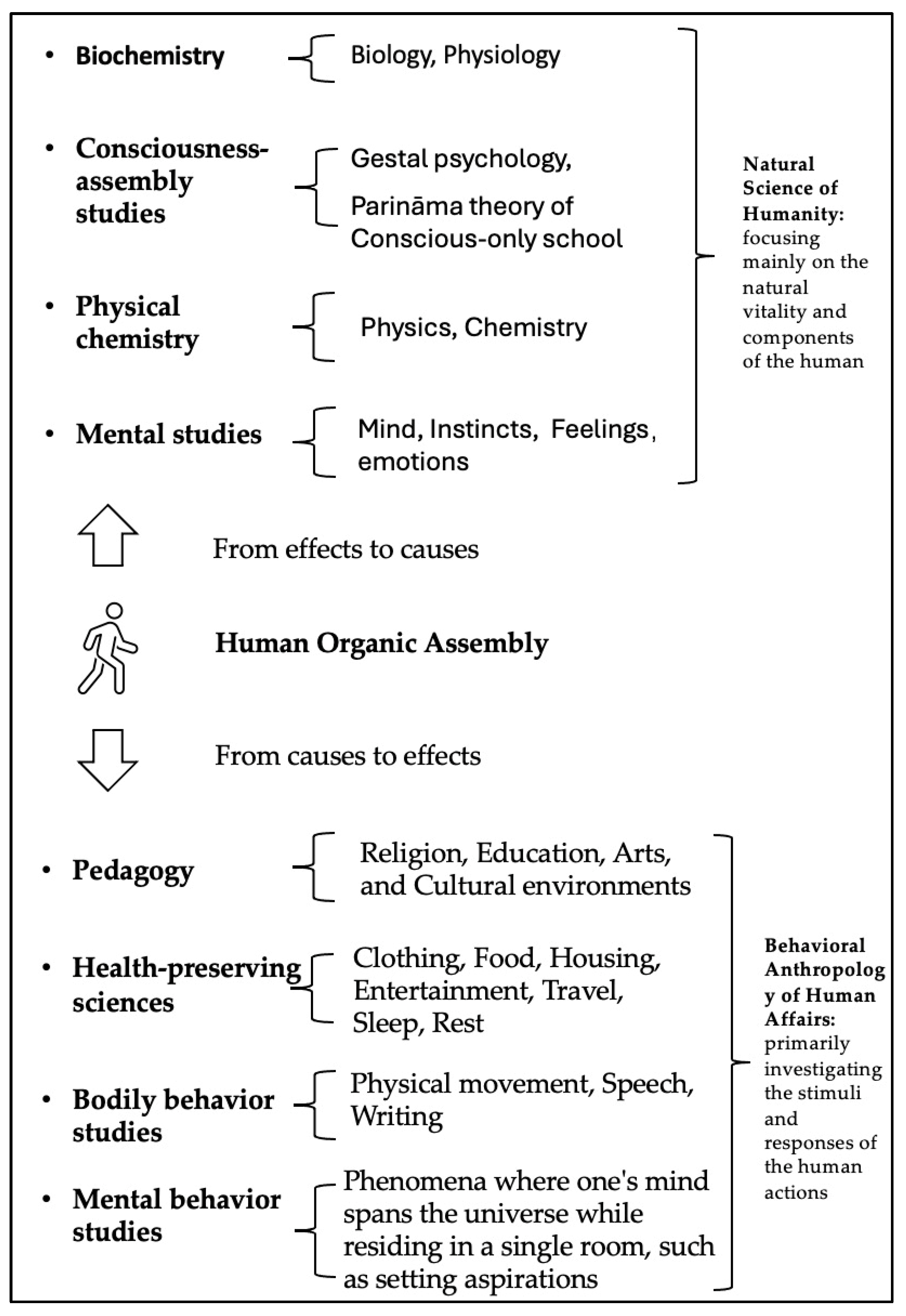

Figure 1:

The re-conceptualized behaviorism study, as proposed by Taixu in conjunction with Buddhist principles, offers a novel perspective. Initially, Taixu identified the theoretical foundation of behaviorism within Buddhism, aligning it with the idea of “Sense-faculties Being Great” (genda 根大) expounded in the Śūraṅgama-sūtra. Building on this, he proposed that Behaviorism can be considered as a “Sense-faculties-only Theory”.

The

Śūraṅgama-sūtra records a discourse Buddha speaks to Ānanda, stating the following:

If you wish to know ignorance that pervades your life and binds you to the cycle of birth and death, no other factor to consider beyond your six sense faculties. Likewise, if you wish to understand the supreme wisdom that leads to a state of joy, liberation, and a state of marvelous, unchanging tranquility, once again, your six sense faculties remain the sole focus…The process of cognition is prompted by external objects, while the formation of the characteristic of things relies on the sense faculties. Both the characteristic and the cognition of it are interdependent and lack inherent nature, just like the intertwined reed (

jiaolu 交蘆).

18 汝欲識知俱生無明使汝輪回生死結根,惟汝六根,更無他物。汝復欲知無上菩提令汝速證安樂解脫,寂靜妙常,亦汝六根更非他物……由塵發知,因根有相,相見無性,同於交蘆.

Taixu argued that within the Yogācāra’s eight consciousnesses framework, the seventh consciousness (deluded consciousness) is fundamentally grounded on the sixth consciousness (mental consciousness). Texts such as the

Avataṃsaka-sūtra, the

Lankāvatāra-sūtra, and the

Saṃdhinirmocana-sūtra take consciousness as the core of discourse by expanding the scope of consciousness to encompass the sense faculties within consciousness. However, the

Śūraṅgama-sūtra advocates “Sense-faculties Being Great”, positing that both the reincarnation and nirvāṇa are entirely based on sense faculties, which expands the scope of sense faculties to encompass not only material aspects but also the entire spectrum of eight consciousnesses. Thus, the theory presented in the

Śūraṅgama-sūtra can be termed the Sense-faculties-only Theory. Taixu contends that the parallels between the Sense-faculties-only Theory in the

Śūraṅgama-sūtra and Behaviorism are significant, suggesting mutual compatibility. The notion of “cognition is prompted by external objects” corresponds to the behavioral idea that the reactive behavior is stimulated by environmental cues. Similarly, the concept of “the formation of the characteristic of things relies on the sense faculties” corresponds to the behavioral idea that the thoughts and knowledge are shaped by stimulus-induced responses. This coherence underscores the logic shared between the Sense-faculties-only Theory and behaviorism, positing that knowledge arises from the inherent response mechanisms of organisms to environmental stimuli.

19Building upon this foundation, Taixu proposed an Ideal Behavioral Science

20 or, precisely speaking, an anthropology centered around human behavior, as presented in

Figure 2.

21 This Ideal Behavioral Science aimed to elucidate the various responses triggered within and outside the “human organic assembly” (人的有機團), a term encompassing the body and mind. Taixu criticized existing behaviorism for its incomplete coverage of human behavior, as it overlooked both the mental phenomena and numerous physiological phenomena. He advocated that the Ideal Behavioral Science should be based on the reality of the human body and mind, delving into the origins of present conditions and examining the impacts of the current behavioral stimuli. From effects to causes, this approach encompasses a range of disciplines: biochemistry (including biology, physiology, etc.), consciousness-assembly studies (including Gestalt psychology, the Parināma theory of Consciousness-only school, etc.), as well as physical chemistry and mental studies (including mind, instincts, feelings, emotions, etc.)—this aspect can be considered the natural science of humanity, focusing mainly on the natural vitality and components of the human. Conversely, from causes to effects, it leads to pedagogy (including religion, education, arts, cultural environments, etc.), health-preserving sciences (including clothing, food, housing, entertainment, travel, sleep, rest, etc.), bodily behavior studies (including physical movement, speech, writing, etc.), and mental behavior studies (phenomena transcending physical boundaries, such as setting aspirations). This aspect can be considered as the behavioral anthropology of human affairs, primarily exploring the stimuli and responses inherent in human actions. The Ideal Behavioral Science envisioned by Taixu is essentially a comprehensive study of all aspects of life, starting from human behavior, which is why he also referred to it as “philosophy of life”. In alignment with this all-encompassing research objective, Taixu believed that the methodologies of behavioral science should not be confined to the studies of observable behaviors, despite the validity of this approach. Beyond this method, Taixu proposed a range of investigative techniques, including introspection, questionnaire surveys (conducted across social, ethnic groups), discourse analysis, the analysis of individual inner experiences, hypnosis experiments, meditative observations from Samādhi, and the development of the power of knowing others’ minds (

taxin tong 他心通) during the states of tranquility (

śamatha) and insight (

vipaśyanā). Moreover, Taixu particularly highlighted the power of knowing others’ minds—a skill that, when mastered by a sage of supreme wisdom, allows one to understand another’s intentions merely by observing their physical actions, without the necessity of verbal communication. Taixu believed that although this is not a typical psychological phenomenon; rather, it represents a more wholesome and elevated form of psychology, one that is accessible to all through dedicated practice.

In summary, starting from his unique interpretation of Buddhist psychology, Taixu critically examined Western psychological traditions. He focused on the predominant behaviorism, criticizing its adherence to the pitfalls of scientific research and acknowledging its advancement of our understanding of the mind–body relationship. Since behaviorism negates the value of introspection in psychological research and sometimes appears to dispense with psychology altogether, Taixu argued that it should be separated from psychology and established as a distinct discipline. By drawing insights from the Śūraṅgama-sūtra which emphasizes “Sense Faculties Being Great”, he envisioned an ideal type of behavioral science that, essentially centered on behavior, encompasses all aspects of human life.

During Taixu’s era, there was a call to incorporate Buddhism into science. In 1925,

Haichaoyin published an article soliciting various types of articles on Buddhicised science (

Fohua kexue 佛化科學). The disciplines included Buddhicised astronomy, Buddhicised geography, Buddhicised geology, Buddhicised political science, and Buddhicised psychology, among a total of 29 categories (

Manzhi 1925, p. 32). Although historically, most of these proposed Buddhicised scientific disciplines were not practically developed, Taixu’s aforementioned constructions in psychology and behaviorism can be considered an expansion of Buddhicised psychology.

22We may ask why Taixu, a Buddhist monk, conducted such extensive research into various Western psychological schools. To gain a comprehensive understanding of Taixu’s unique interpretation of Buddhist psychology, it is essential to examine his fundamental stance when he approached this discipline. It is necessary to point out that Western academia’s research on Buddhist psychology began much earlier than in China. During Taixu’s era, Western scholars were still continually breaking new ground in this field. For example, in 1922, at the 7th Congress of the International Psycho-analytical Association held in Berlin, Franz Alexander (1891–1964) discussed the potential psychological hazards of Buddhist meditation, considering dhyānas to cause “psychic regression.” Joseph C. Thompson (1874–1943) considered Buddha’s way of teaching as an example of “positive transference” and in his teachings “a rational scheme of libido control” (

Sgorbati, forthcoming). Jung even believed that psychology was already embedded in Buddhist teachings, and he also considered psychoanalysis as “only a beginner’s attempt compared with what is an immemorial art in the East”.

23 However, Taixu’s discussion on psychology was not a direct product of the international discourse on Buddhist psychology at the time; his engagement with Western psychology had its own historical reasons, rooted in the intellectual trends in China at the time.

4. Guiding Practice: The Position of Buddhist Psychology in Taixu’s Conceptual Framework

Taixu once articulated the motivations behind his study of Buddhist psychology:

Buddhist dharma is vast and profound, fully equipped and meticulously organized, with its scriptures and treatises being complete and exquisite, leaving little room for subsequent generations to tamper with. However, in response to the demands of our era, it is our duty to conduct a systematic study using scientific methodologies! Psychology, as a vital component of modern science, is still in the process of maturation. Despite the breadth of Buddhist teachings, their focus ultimately lies in the mind, delving deeply into the human psyche. Therefore, it is the responsibility of Buddhists to utilize this profound elucidation to fill the gaps where modern psychological science has yet to reach. Today, in undertaking this brief study, I aim to shed light on the foundational principles of the discipline. 佛法廣博幽深,無乎不備,無乎不精,經論組織亦盡善美,無待後人弄斧。但應時世要求,以科學之方法為分類之研究,亦吾人之責! 心理學者,為近世科學之要部,以後進之故,未至大成。佛法雖廣,要歸一心,故於心理闡之特詳。以此特詳補彼未成,佛教徒之義務有在,今略研究以立斯學張本.

24

This statement clearly underscores that Taixu’s exploration of Buddhist psychology transcended mere academic interest or abstract theoretical inquiry; it was a timely response to the worldly needs of his era. During the late Qing and early Republican period, under the influence of Western knowledge, the concept of “science” in the modern sense gradually gained popularity in China. The New Culture Movement in the 1910s and 1920s elevated science as a beacon of enlightenment, a path to truth, and a defining spirit of the era, serving as a benchmark against which the value of humanities and academic disciplines were measured. Intellectuals like Chen Duxiu 陳獨秀 (1879–1942), Hu Shi 胡適 (1891–1962), and Lu Xun 魯迅 (1881–1936) conducted a thorough reassessment of various religions and superstitious practices under the banner of science. Chen Duxiu declared that “the true faith, understanding, practice, and realization of humanity will ultimately be based on science, and all religions are to be abandoned”, advocating for “science to replace religion” (

Chen 2014, p. 278). Hu Shi regarded Buddhism as a superstition imported from India, stating that “95%, or perhaps even 97% of Chan Buddhism is nonsense, fabrication, fraud, pretension, and posturing” (

Hu 1992, pp. 280–81).

Prominent Buddhist intellectuals, including monks and laymen such as Tang Dayuan, Wang Jitong 王季同 (1875–1948), and Taixu, delved extensively into the interplay between Buddhism and science. On one hand, they compared the doctrine of Buddhism with modern science, in an attempt to demonstrate the Buddhist teachings’ compatibility with modern science and highlight its inherent truth and superiority. For example, Tang Dayuan believed that the Consciousness-only school (

Vijñānavāda) of Buddhism aligned with the analytical and empirical spirit of science, positing that its philosophical concepts could be visually represented using scientific diagrams (

Tang 1929, p. 6). Taixu cited Buddhist statements like “Buddha see 84,000 insects when observing a drop of water” (佛觀一滴水,八萬四千蟲) and “viewing the body as a congregation of insects” (觀身如蟲聚), suggesting that they aligned with scientific theories of microbiology and cell theory.

25 On the other hand, these scholars also sought to use Buddhism’s spiritual dimensions to address the limitations of science. For instance, Taixu, while appreciating science’s methodical experimentation, relentless pursuit of knowledge, and openness to falsification, criticized its exclusive focus on empirical methods for uncovering truth. He believed that science, overly relying on experimental methods for discovering truth, overlooked the transcendent nature of reality beyond empirical observation.

26 Essentially, these discussions on the relationship between Buddhism and science were responding to the backdrop of Western thought and the prevailing scientific trends of their era.

From this, we can understand why Taixu repeatedly stated in his writings on psychology that while certain psychological theories bear resemblance to Buddhist theories in some respects, they remain incomplete, and Buddhism provides more profound insights into certain problems. This perspective reflects a common mindset within the Chinese cultural sphere of the time, acknowledging the value of Eastern culture amidst its encounter with Western culture and endeavoring to verify its merits.

27 Just like his contemporaries, in the comparative study between Buddhism and Western psychology, Yogācāra theory is the main intellectual resource for Taixu. He believed that the exploration of the mind, mental properties, and mind-unassociated dharmas were far more exhaustive than Western psychology.

The Buddhist teachings on mind and mental properties, namely, the eight-consciousness theory about mind and the fifty-one mental properties arising in conjunction with the mind, exhibits a level of depth and intricacy that surpasses that of psychology. Furthermore, the profound mysteries within the mind-unassociated dharmas (

bu xiangying xing fa 不相應行法) such as the cessation of mental activity and sense of existence (

miejin ding 滅盡定) and the attainment of non-perception (

wuxiang ding 無想定), are beyond the scope of what Western psychology can perceive. 佛學之心心所法,實較心理學為詳盡。如八識心法及與心相應而起用之五十一心所法;又不相應行法中之無想定、滅盡定等奧義,遠非心理學所能窺見.

28

The five categories of the hundred dharmas are revealed in both the Mahāyāna-śatadharma-prakāśamukha-śāstra and the Pañcaskandhaprakaraṇa, dividing worldly dharmas into five categories: mind (citta), mental properties (caitasika), form (rūpa), mind-unassociated dharmas (citta-viprayukta-saṃskāra), and unconditioned dharmas (asaṃskṛta). Among these, “mind” and “mental properties” specifically address cognitive abilities and various consciousness phenomena associated with cognition. The mind is further divided into eight types: eye consciousness (cakṣur-vijñāna), ear consciousness (śrotra-vijñāna), nose consciousness (ghrāṇa-vijñāna), tongue consciousness (jihvā-vijñāna), body consciousness (kaya-vijñāna), mental consciousness (mano-vijñāna), deluded consciousness (kliṣṭamano-vijñāna), and storehouse consciousness (ālaya-vijñāna).

The first five consciousnesses arise dependent on sense faculties (material organs) and correspond to the five cognitive objects: color, sound, scent, taste, and touch. The sixth consciousness arises dependent on the mental faculty, which is the seventh consciousness, the deluded consciousness. This consciousness perceives all dharmas spanning the past, present, and future. The deluded consciousness arises dependent on the eighth consciousness, the storehouse consciousness. Since the storehouse consciousness has been in operation continuously since beginningless time, it appears as a constantly existing independent entity, similar to the commonly understood concept of the Self. Therefore, the deluded consciousness apprehends the storehouse consciousness as the Self. It is termed “deluded” because this consciousness constantly engages in analysis, deliberation, and false assumption. The eighth consciousness, referred to as the storehouse consciousness or the fundamental consciousness, harbors the seeds of habitual tendencies that have existed since beginningless time. It relies on the deluded consciousness as its foundation and perceives seeds, body, and the physical world as its cognitive objects. Mental properties include universal mental properties such as attention (manasikāra) and contact (sparśa); particular mental properties such as mindfulness (smṛti) and concentration (samādhi); wholesome mental properties such as faith (śraddhā) and diligence (vīrya); unwholesome mental properties such as greed (lobha) and hatred (dveṣa); the indeterminate mental properties such as remorse (kaukṛtya) and torpor (middha); the mind-unassociated dharmas (citta-viprayukta-saṃskāra) such as the cessation of mental activity and sense of existence (nirodha-samāpatti) and the attainment of non-perception (asaṃjñi-samāpatti).

Taixu believed that while the various schools of Western psychology prevalent during the time possessed their own specializations, they all fell short in terms of depth and breadth when compared to the Yogācāra analysis of the human psychological states. For example, Hans Driesch (1867–1941), a representative of the vitalism

29, posited the concept of

entelechy—a non-material, non-spatial, teleological, order-giving metaphysical element absent in non-living creatures. Taixu considered the notion of

entelechy essentially a variant of soul theory. Although it might bear some resemblance to the Buddhist concept of storehouse consciousness, it is deemed vague and lacking precise and thorough observation.

Similarly, Gestalt psychology, represented by Max Wertheimer (1880–1943), Wolfgang Köhler (1887–1967), and Kurt Koffka (1886–1941), opposed reducing psychology to basic elements and behavior to stimulus–response connections. They viewed thinking as more than just a simple collection of associated representations. They argued that learning involves forming and transforming Gestalt patterns. This perspective aligns with the Buddhist principle that psychological states arise from multiple conditions, as acknowledged by Taixu. However, Gestalt psychology’s focus on perception only reveals the phenomena of the sixth consciousness and fails to address the psychological aspects of the first five consciousnesses, deluded consciousness, and storehouse consciousness, thus leaving it incomplete.

Furthermore, Connectionism—a theoretical framework in cognitive science—employs artificial neural networks to simulate brain functions and mental phenomena. The core premise of Connectionism is that psychological and mental phenomena can be described through networks of simple and consistently interacting units. These units and connections represent neurons and synapses, mimicking how the brain operates. Taixu believed that Connectionism, by starting its analysis from sensation to explain perception, memory, and other psychological functions, essentially integrates mechanistic views from the time of Francis Bacon (1561–1626) and John Locke (1632–1704). However, it only involves the first six consciousnesses and fails to reveal that the stimulus–response interactions of sense faculties and objects are mutually constituted by multiple conditions. As a result, it does not achieve ultimate understanding.

Taixu’s critique of the aforementioned schools was brief and not exhaustive; his intent was not to analyze each school in detail but rather to highlight the depth and breadth of Buddhist teachings in psychological research, so as to illustrate the enduring relevance of Buddhism even in an era marked by the flourishing of science. However, this was merely the starting point of Taixu’s exploration into psychology. As he delved deeper, he recognized the contemporary value of psychology itself: as a prominent secular study of the time, it held the potential to purify the human mind. Therefore, it found a place within his overarching vision of “Buddhism for Human Life” (rensheng fojiao 人生佛教).

In Taixu’s conceptual framework, Buddhist psychology signifies the practical application of his “Buddhism for Human Life.” As outlined by Taixu and compiled by his disciple Yinshun 印順,

Taixu dashi quanshu 太虚大师全书 (Completed Works of Master Taixu) is divided into four collections: the Dharma Collection (

Fazang 法藏), Regulations Collection (

Zhizang 制藏), Treatise Collection (

Lunzang 论藏), and Miscellaneous Collection (

Zazang 杂藏). Each collection is further divided into fascicles, totaling seven fascicles in the Dharma Collection, three in the Regulations Collection, four in the Treatise Collection, and six in the Miscellaneous Collection—twenty fascicles in all. The Dharma Collection mainly includes Taixu’s theoretical achievements in the study of Buddhist history and doctrines. The Regulations Collection delves into topics related to monastic discipline, monastic management, monastic education, and practice methods. The Miscellaneous Collection includes lectures, commentary on current-affairs, book reviews, prefaces, autobiographies, diaries, essays, interviews, poetries, and so on. The Treatise Collection is subdivided into four fascicles: Base of the Principle (

zongyi 宗依), Essentials of the Principle (

zongti 宗體), and Applications of the Principle (

zongyong 宗用), along with some supplementary articles. The first three parts are combined into the book

Zhen Xianshilun 真現實論 (Treatise on True Reality), an important work that lays the theoretical foundation for Taixu’s “Buddhism for Human Life”. Taixu elucidated the title of this book by stating that

Xianshi 現實 (Reality) refers to the universe, which is also the entirety of all realities within time and space.

Xianshi is the Dharma realm, the sum of all dharmas.

Xianshi can also refer to present facts, and statements or claims based on these present facts are referred to as realism.

Zhen Xianshilun is an exposition of the real nature of phenomena as they are perceived, offering an authentic portrayal of the reality of the world.

30The fascicles on “Base of the Principle” were written in 1927 and were independently published by Chung Hwa Book Company in 1940. This fascicle starts from different aspects of cognition to elaborate on the reality of existence, addressing methodologies for cognizing reality, the objects cognized within reality, the constituent components cognized within reality (based on the Buddhist concept of the Five Aggregates), and the relationships among these cognized components. The fascicles on “Essentials of the Principle” originated from Taixu’s lectures at the Han-Tibetan Institute of the World Buddhist Studies Center (世界佛學苑漢藏教理院) in 1938, which were originally planned to include five parts—doctrine of reality, practice of reality, reward of reality, teaching of reality, and the combination reality of doctrine, practice, reward, and teaching—this series was not completed due to Taixu’s death in 1947, with only the part on the “doctrine of reality” being recorded and compiled. When planning the book

Zhen xianshi lun, Taixu had designed a fascicle on the “Application of the Principle”, but he passed away before he could write it. His disciple Yinshun categorized Taixu’s discussions on worldly knowledge into sections like culture, religion, Chinese traditional culture, philosophy, morality, psychology, science, views on human life, society, education, health, and arts, compiling them into the fascicle on the “Application of the Principle” to form a complete

Zhen xianshi lun. These articles responded to the prevalent ideological trends of his time and represented Taixu’s integration of Buddhism with secular knowledge. Yinshun described

Zhen xianshi lun as “grand in scale and extensive in scope, capable of coherently encompassing all of Buddhism and critically covering all secular studies” (

Yinshun 2009, p. 157). Generally speaking, Taixu’s main purpose in composing

Zhen xianshi lun is to comprehensively construct a modern integration system that bridges Buddhism and secular knowledge.

In the articles related to psychology, Taixu critically integrates modern psychological ideas from the perspective of Buddhist teachings. Thus, they were included in the “Fascicles on Application of the Principle” by Yinshun, aligning with Taixu’s fundamental concept of integrating world culture with Buddhism. In the book

Renshengguan de kexue 人生觀的科學 (Science of the View of Human Life), Taixu discusses the appropriate use of contemporary human culture at the outset of one’s life journey, advocating that the fundamental principle of human existence lies in understanding and seeking refuge in the three true aspects of life—including faith in the law of karma and rewards. Based on the psychology described at our time, individuals should regulate and moderate their own mentality, cultivating virtuous mindset and behaviors. While contemporary psychology has not yet fully fulfilled this requirement, people are encouraged to diligently study texts such as the

Yogācārabhūmi-śāstra and strive to make progress.

31 In summary, in Taixu’s conceptual framework, though not the ultimate truth, psychology is also a valuable tool for individuals to understand themselves and thus embark on the path of enlightenment. It complements Buddhist teachings, aiding humanity in overcoming afflictions and advancing toward liberation. Taixu once discussed the advantages of Buddhist psychology over secular psychology as follows:

Secular psychology focuses on observing the psychological functions of living beings and ordinary people, restricting itself to recording and describing these observations. Buddhist psychology, in contrast, transcends this scope by categorizing, inferring, and making moral judgments about good and evil—ultimately offering practical guidance for self-cultivation and realization of truth. Thus, this study is applicable in practice, avoiding empty theoretical discussions. 世俗心理學,就生物及常人心理作用觀察,但為敘列述明之記錄而已…佛教心理學不然,集類推論而外,又必抉擇善惡,指示修證,而後此學有所應用,不至空談學理.

32

In Taixu’s view, secular psychology primarily serves as a descriptive and archival discipline, often engaging in empty theoretical discussions. However, Buddhist psychology not only observes and organizes human psychological phenomena but also make value judgements about our mental states. Then, the Buddhist psychological theories are used to guide human behavior, showing a practical significance. Taixu’s positioning of Buddhist psychology aligns with the fundamental intent of all Buddhist doctrines: Buddhism’s interpretation and exploration of the world serve its ultimate pursuit of enlightenment or liberation.

In addition to Taixu, other scholars have also made elaborations regarding the enlightenment-oriented aspects of Buddhist psychology. For example, Zhang Huasheng’s interpretation can be seen as a supplementary note on how Buddhist psychology leads one to enlightenment. Zhang identified three key elements in Buddhist psychology: the method of “cessation” (止法), which involves stopping all arising and ceasing phenomena; the method of “observation” (觀法), which involves broadly observing all mental states and their causes; and the method of “realization” (證法), which involves realizing the full nature and functions of the human mind. These methods are used for spiritual practice, essentially guiding individuals to explore their own minds and to comprehend a series of Buddhist truths such as karma, suffering, emptiness, impermanence, and non-self, ultimately achieving liberation and enlightenment. In terms of ultimate purpose, he argued that Western psychology, which aims at practical application, belongs to the realm of cyclic existence (流轉門). It utilizes the psychology of deluded, reckless activity, fostering attachment to self and possessions, and perpetuating the three poisons of greed, hatred, and ignorance, as well as the five desires of wealth and sensual pleasure, leading to endless suffering. From the Buddhist perspective, this is pitiable. In contrast, Buddhist psychology aims at liberation, belonging to the realm of cessation (還滅門), and posits that the most crucial issue in human life is to liberate oneself from the realm of cyclic existence. The key to breaking the cycle of rebirth lies in the liberation of the mind, because the cyclical existence of sentient beings is, in essence, the cyclical existence of the mind.

33 5. Conclusions

Taixu utilized affection, reflection, and wisdom as key terms in constructing a Buddhist psychology. These three psychological states are hierarchically arranged, with affection being the lowest and wisdom the highest. Taixu advocated for the cultivation of wisdom through personal endeavor, aiming to foster the most balanced and enriched psychological well-being. Starting from this ideal psychology, Taixu critiqued the Western psychological tradition, perceiving it as lacking in both theoretical depth and breadth. He specifically criticized behaviorism, arguing that its basic assumptions were incorrect—behaviorists deemed behavior and the external world as “objective” and knowable, while classifying one’s own conscious world as “subjective” and unknowable, thus treating it as nonexistent.

Taixu acknowledged that behaviorism made valuable contributions to psychological inquiry, such as delving deeper into the mind–body relationship, challenging the soul theory, and broadening the scope of traditional psychological examinations. Therefore, Taixu integrated the Sense-faculties-only Theory revealed by Śūraṅgama-sūtra, thereby reconstructing an Ideal Behavioral Science. He argued that the Ideal Behavioral Science should be separated from psychology. By tracing the actions concerning the physical and mental phenomena of human beings, it should develop a natural science of humanity that concentrates on the natural vitality and components of the human existence. Moreover, this Ideal Behavioral Science should also analyze the functions of behavior, developing into a study of human actions and reactions. Essentially, Taixu envisioned that Ideal Behavioral Science is centered on behavior, encompassing all aspects of human life, and positioning psychology not merely as a description of mental states but as a guide of practice towards liberation.

In the intellectual sphere of China, both Liang Qichao and Taixu were pioneers in studying Buddhist psychology. However, although Taixu proposed very interesting and profound insights and raised many important questions in Buddhist psychology—including, but not limited to, the detailed content of the psychology of affection, reflection, and wisdom; the construction of the discipline of Buddhist psychology; and the practical path of how Buddhist psychology leads to enlightenment—his discussions on these issues did not develop into a systematic theoretical framework. After Taixu, more Chinese intellectuals participated in the writing of Buddhist psychology. The Wuchang School’s exploration of the relationship between Yogācāra and psychology also became important early achievements. Over time, the development of Buddhist psychology gradually merged with Western psychology, addressing the grand issue of how Buddhist philosophical resources could contribute to modern psychological exploration. Today, there are many specialized works on Buddhist psychology within both Eastern and Western philosophical traditions, for example, D.T. Suzuki, Erich S. Fromm, and De Martino’s

Zen Buddhism and Psychoanalysis (

Suzuki et al. 1960); Rune E.A. Johansson’s

The Psychology of Nirvana (

Johansson 1969); Edwina Pio’s

Buddhist Psychology: A Modern Perspective (1988); etc. In China, besides professional psychology works written by scholars such as Weihai’s

Wuyun xinlixue (2005) and Chen Bing’s

Fojiao xinlixue 佛教心理學 [Buddhist Psychology] (2007), there are also many Buddhist psychology-related leisure books or self-help books.

34 Furthermore, contemporary research in Buddhist psychology in China still follows, in some aspects, the tradition left by Liang Qichao and Master Taixu. First, in terms of research methodology, there is an emphasis on philosophical and theoretical discussions and the extraction of the Buddha’s wisdom from the scriptures, but there has been little progress in empirical studies. Second, there is an emphasis on the superiority of Buddhist psychology over Western psychology, with the theories primarily stressing the extensive exploration of human consciousness by the Yogācāra school and the ultimate goal of liberation in Buddhism, just like Taixu did.

Of course, the value of Taixu’s research on Buddhist psychology is not only reflected in the theoretical advancement of psychology but also holds deeper cultural significance. His groundbreaking work in integrating Western knowledge and Buddhist dharma can also be regarded as a significant dialogue between Eastern and Western civilizations. In the era of Taixu, Western culture held an absolute dominance in the world, sweeping across the East with overwhelming power. At the beginning of the 20th century, amidst the opposition between Eastern and Western cultures and the existential crisis of the Chinese nation, Chinese intellectuals sparked an “East–West Culture Debate (東西文化論戰)”. The central questions of this debate revolved around the distinct characteristics of Eastern and Western cultures, their fundamental differences, and the comparative merits and drawbacks of each. The debate also raised questions about the inherent value of Eastern culture, its future trajectory, and whether Western culture was superior. These were significant questions that deeply troubled Chinese intellectuals. Participants in the debate could generally be divided into three groups: the “Conservative Faction”, represented by Gu Hongming 辜鴻銘 (1857–1928), who advocated for adhering to Chinese traditions and rejecting Western culture; the “Moderate Faction”, represented by figures such as Liang Qichao 梁啟超 (1873–1929), Liang Shuming 梁漱溟 (1893–1988), Zhang Junmai 張君勱 (1886–1969), Zhang Shizhao 章士釗 (1881–1973), and Taixu, who advocated for a blending of Eastern and Western cultures; and the “Westernization Faction”, represented by Chen Xujing 陳序經 (1906–1989), who advocated for complete Westernization. The discussions not only reflected the confusion and bewilderment of intellectuals brought about by the national crisis but also demonstrated their sense of responsibility and mission to seek rejuvenation amidst national difficulties.

The intellectuals of the “Moderate Faction”, including Taixu, actively engaged in the study of Western science, technology, and advanced cultural theories. Simultaneously, they endeavored to recognize and validate the value of Eastern culture. By integrating new Western knowledge, they re-examined and re-interpreted the intellectual resources within Eastern cultural traditions. This approach allowed ancient Eastern wisdom to revive and thrive in a new context. From a modern perspective, the discussions on Eastern culture during this period left a precious legacy. On one hand, the value of Eastern culture was substantiated, fostering an atmosphere that preserves and defends it. On the other hand, stimulated by new Western knowledge, the classical intellectual resources of the East were highlighted anew under fresh methodologies and perspectives.