Abstract

Many mental health care patients, regardless of their religious beliefs, prefer a similar outlook on life with their professional caregivers. Patients experience greater openness to discuss religion and spirituality (R/S), mutual understanding, less fear of disapproval and report a higher treatment alliance. The question is whether the core problem of a so-called ‘religiosity gap’ (RG) lies in (a) an objective difference in outlook on life, (b) a perceived difference in outlook on life or (c) in unmet R/S care needs. We explored this by matching data of 55 patients with their respective caregivers for a quantitative analysis. An actual (objective) RG, when patients were religious and caregivers not, was not associated with a lower treatment alliance but a difference in intrinsic religiosity, especially when caregivers scored higher than patients, was related to a lower treatment alliance. A subjective RG, perceived by patients, and a higher level of unmet R/S care needs were also significantly associated with a lower treatment alliance as rated by patients. These results emphasize that sensitivity, respect and openness regarding R/S and secular views are essential elements in treatment and might benefit the treatment relationship.

1. Introduction

A significant number of individuals seeking mental health care tend to value sharing a similar outlook on life with their caregivers. A comparable ‘outlook on life’ encompasses shared beliefs, values, and existential perspectives, whether rooted in religion, spirituality, or secular philosophies. This preference has been observed in various countries, such as Canada (24% of patients with various diagnoses and R/S backgrounds, Baetz et al. 2004) and the Netherlands (more than 50% of patients, van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse et al. 2020). One of the key reasons patients mention for preferring a shared outlook on life is the desire to engage in conversations about religion and spirituality (R/S) with their caregivers. When they share a similar outlook on life, they report feeling more confident in experiencing mutual respect and do not fear judgment or advice that contradicts their R/S (van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse et al. 2018). Research shows that patients who regret a gap in outlook on life with their caregiver(s) report a lower treatment alliance, being a predictor of treatment success (van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse et al. 2021).

An intriguing aspect is that studies examining the actual impact of a difference in outlook on life between caregivers and patients on treatment outcomes have not uncovered differences in outcomes. For example, Orthodox Jewish patients benefit equally from treatment regardless of whether caregivers share their faith or not (Rosmarin and Pirutinsky 2020). Similarly, another study within the Jewish community indicated that patients experienced a stronger working alliance when treatment occurred outside their religious context, suggesting that Jewish patients may benefit more from therapy detached from their religious background (Stolovy et al. 2013). Stolovy and colleagues suggested that culturally sensitive treatment, fostering a sense of respect and acknowledgment for patients, proves to be effective and valuable. Consequently, they emphasized the importance of training caregivers in the nuances of culturally sensitive treatment. A study by Liefbroer and Nagel (2021) describing patients’ appreciation of conversations with spiritual caregivers showed that an objective match does not matter for appreciation, while a subjective match was significantly associated with appreciation.

The differences in research outcomes raise various questions. For instance, one might question whether different study populations (the initial studies conducted among Christians versus the subsequent studies among Jewish populations) benefit from a ‘religiosity match’ or not. It may also be the case that in a secularized context, patients have reduced expectations regarding R/S care. Another aspect open for debate concerns the methodology of measuring treatment effectiveness. When does a treatment become beneficial and what role does the therapeutic relationship play in this? An important aspect that should not be overlooked is the fact that there is a difference in the studies between measuring preferences versus actual differences. While some studies took preferences into account, others examined ‘actual’ differences in outlook on life. The question remains open whether an actual difference in outlook on life could be problematic, or whether a perceived and regretted difference in outlook on life is the real problem. Additionally, it can be questioned what the regretted difference has to do with unanswered R/S care needs. It is plausible that caregivers without a religious outlook on life may encounter challenges in providing R/S integrated care without training. Spiritual caregivers indeed assume that holding different outlooks on life between them and patients may relate to a lower appreciation of the care that is provided to them (Liefbroer and Berghuijs 2017). At the same time, within somewhat similar but not entirely alike religious cultures, such as different Christian denominations, tensions between beliefs and practices may occur, potentially resulting in individuals preferring care outside their religious context. When religious beliefs of clients provoke feelings of aversion, anger, or disapproval—or on the other hand, for example, overenthusiasm in the caregiver—this phenomenon, identified as religious countertransference, can significantly impact therapeutic relationships (Abernethy and Lancia 1998). Furthermore, from an epistemological viewpoint, the exact nature of actual (or objective) and perceived (or subjective) differences can be discussed, as well as how these differences relate to measurement methods. Thus, from this perspective, the influence of religious or cultural factors on care can be complex and can cut both ways.

All these uncertainties prompt the question: what exactly constitutes a real ‘religiosity gap’? Is it (a) primarily about an actual disparity in outlook on life between the caregiver and the patient? Or does (b) a perceived difference in outlook on life hold greater significance? Or is the matter all about (c) unmet R/S care needs, as shown earlier to be a predictor of a lower treatment alliance? This may indicate underlying factors such as a lack of space to integrate R/S aspects into treatment. It is plausible that factors like respect and sensitivity exert more influence than a direct match in outlook on life. The current study aimed to address these inquiries by examining the associations between (a) an objective difference in outlook on life, (b) a perceived difference in outlook on life and (c) unmet R/S care needs, with treatment alliance. Treatment alliance was measured from both the patient’s and the mental health professional’s perspectives. By investigating treatment alliances in these three scenarios, the goal was to compare different types of ‘gaps’ in the same population, while using treatment alliance—an established predictor of treatment success—as the outcome.

2. Materials and Methods

The current study was conducted in The Netherlands in a collaboration between two mental health care institutions, Altrecht, Utrecht and Eleos, Bosch en Duin, and two research centers, the center for research and innovation in Christian mental health care, Hoevelaken, and the University of Humanistic Studies, Utrecht. Because the Mental Health Care Institution, Eleos, is a Christian institution, the percentage of Christian patients and caregivers was relatively high. Differences in outlook on life thus revolved around being Christian or non-affiliated, with distinctions within the Christian population being made between different denominations. Since a follow-up measurement was used for the current study, during the time of measurement, not all patients recruited at Eleos still received care in a Christian context; therefore, it was not possible to distinguish between patients receiving care in a religious institution or not. In the current study, we focused on personal differences between caregivers and patients.

2.1. Research Design

In this quantitative study, we employed a matching design, pairing patients with their caregivers to assess the impact of a ‘religiosity gap’, being employed as an objective (actual) difference in outlook on life between caregivers and patients, a subjective (perceived) difference in outlook on life between caregivers and patients and unmet R/S care needs, on treatment alliance and compliance.

2.2. Procedure

Data for the current study were obtained from a larger study on R/S care needs, in which clinical mental health care patients completed a quantitative questionnaire at baseline (n = 201) and after six months (n = 136). During the second measurement, patients were asked for permission to approach their professional caregiver(s) to fill in a matching questionnaire about them. Approximately 60% of the population (i.e., 85 patients) agreed, and of those, 55 had one, two or three caregivers who could be successfully approached and also agreed to fill in a matching questionnaire. This resulted in a population of 55 patients and 63 caregivers. In order to create 55 matched cases, the first caregiver who filled in the questionnaire for each patient was included. This was a random selection because it was unknown who was the main practitioner for the 7 cases in which two or three caregivers filled in the questionnaire.

2.3. Measures

The questionnaires for both patients and caregivers encompassed demographics (sex, age, R/S background) and assessments of treatment alliance and compliance. Among the patients, we also assessed the level of depressive symptoms, by using the CESD-8, in order to adjust rates of treatment alliance for depressive symptoms.

To examine religiosity/spirituality both among patients and caregivers, we used three measures. First, we measured religious affiliation and divided this into Pietistic Reformed, Mainline Protestant, Evangelical, Roman Catholic or non-affiliated. Second, we used questions in the study “God in Nederland” (God in the Netherlands) (Bernts and Berghuijs 2016). Patients and caregivers were asked whether or not they were believers (0 = “no”, 1 = “yes” and 2 = “do not know”) and to what extent they were spiritual (0 = “no”, 1 = “not really”, 2 = “to some extent” and 3 = “very much”). Following other studies (Bernts and Berghuijs 2016; Ouwehand et al. 2019), we combined these measures into a categorical variable: (1) neither religious nor spiritual, (2) only spiritual, (3) only religious and (4) religious and spiritual. The measure of spirituality was dichotomized: a score of 0 (“not at all”) or 1 (“not really”) was considered as “not spiritual”, and a score of 2 (“to some extent”) or 3 (“very much”) as “spiritual.” The measure of religiousness was also dichotomized, with a score of 0 (“no”) and of 2 (“do not know”) considered “not religious”, and a score of 1 (“yes”) as “religious”. Third, all participants completed the Duke Religion Index (DUREL), which measures three dimensions of religiosity, having high test–retest reliability, high internal consistency, and high convergent validity with other measures of religiosity (Koenig and Büssing 2010). We used the subscale for intrinsic religiosity, consisting of three items (score 0 = “definitely not true of me” to score 4 = “definitely true of me”). In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha of the subscale of intrinsic religiosity among patients was 0.93 and among caregivers 0.96. In addition, we asked both caregivers and patients whether they estimated the patients or caregivers respectively had a similar outlook on life to themselves. The answer options were (0) No, not at all; (1) I don’t know; (2) Yes, I think so and (3) Yes, I am sure of that.

To identify unmet R/S care needs, an R/S care needs questionnaire was employed among patients (see for extended description van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse et al. 2020). Patients were asked to what extent they preferred fourteen items of R/S care, and to what extent these were present in their care. The answers were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = “not at all”, 1 = “not really”, 2 = “to some extent” and 3 = “very much”). The sum of the 14 needs appeared to be a reliable scale (Cronbach’s = 0.92). By combining needs and absence of care, unmet R/S care needs could be distinguished. The R/S care needs questionnaire contained three subscales: R/S conversations, R/S program and recovery and R/S similar outlook on life. Though unmet R/S care needs were mainly measured only from patients’ views, we had a single item question for caregivers to determine whether they considered R/S to be sufficiently addressed during treatment contacts. The statement “R/S receives enough attention in conversations with my patient” could be scored 0 = “totally not true”, 1 = “in fact not true”, 2= “uncertain”, 3 = “in fact true” and 4 = “totally true”.

Treatment alliance was measured among patients and caregivers, using the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI) (Horvath and Greenberg 1989), utilizing the Dutch translation by Vertommen and Vervaeke (1990), presented in a 12-item format (Stinckens et al. 2009). The patient version was slightly modified for multidisciplinary care. For instance, references to a single caregiver were replaced with terms encompassing all involved caregivers. Sample questions included ‘I believe most of the caregivers like me’ and ‘The caregiver(s) and I are working towards mutually agreed-upon goals’. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale: rarely or never (0), sometimes (1), often (2), very often (3) and always (4), resulting in a total score range of 0–48, with higher scores indicating a stronger alliance. The Cronbach’s alpha of the WAI for patients in the current study was 0.91 and for caregivers 0.85.

2.4. Determination of Gaps

The phenomenon of a religiosity gap was elaborated in various ways, to study an objective/actual gap, a perceived gap and unmet R/S care needs, among which also a regretted perceived gap (Table 1).

Table 1.

Types of religiosity gaps and ways in which they were defined.

An ‘objective’ or ‘actual’ religiosity gap was studied in three ways: first, by dividing matched cases into groups (0) both not Christian, (1) caregiver Christian, patient not; (2) patient Christian, caregiver not; (3) both Christian, different denominations and (4) both Christian, same denomination. This variable was both analyzed categorically and dichotomously, in the latter situation considering both Christian or both not Christian as a match and the other situations as a ‘gap’ (see also Table 2). Second, scores of intrinsic religiosity (DUREL) from caregivers and patients were compared, using a difference score (score patient minus score caregiver: intrinsic religiosity): scores < 0 indicating a gap with higher caregiver intrinsic religiosity, a score of 0 indicating no gap (either religious or secular) and scores > 0 indicating a gap with higher patient intrinsic religiosity. Third, we compared self-rated religiousness, caregivers and patients both seeing themselves as religious or both seeing themselves as non-religious being categorized as ‘no actual gap’ and when patients identified themselves as religious and caregivers not or the other way around, rated as ‘gap’.

A ‘subjective’ or ‘perceived’ religiosity gap was determined using the question whether the caregiver or patient, respectively, had a similar outlook on life to themselves. This question was used from the side of patients as well as the side of the caregivers, and also dichotomized, defining scores 0 and 1 as a subjective gap and 2 and 3 as no subjective gap.

Unmet R/S care needs were defined as follows: (1) the sum score of the 14 unmet R/S care needs, (2) the sum score of unmet similar outlook on life (being referred to as a ‘regretted religiosity gap’) and (3) the sum score of unmet R/S conversations. These scales not only represented the level of needs, but the level of unmet needs, indicating a gap that was greater by a higher score. To compare the gap of R/S conversations as perceived by caregivers and by patients, the factor ‘unmet R/S conversations’ was also dichotomized, considering at least one unmet R/S care need in this field as a ‘gap’ and no unmet needs as ‘no gap’ as perceived by patients. The statement for caregivers regarding R/S conversations was dichotomized, considering scores of 0–2 as a gap and 3 and 4 as no gap.

2.5. Analysis

Descriptive statistics were employed to describe and compare the patient and caregiver populations. For all subsequent analyses, data from the first caregiver per patient who filled in the questionnaire were utilized. ANOVA analyses were performed to explore the associations between the categorical variables of a(n) (a) objective/actual and (b) subjective/perceived differences in outlook on life and alliance (WAI) scores. Correlation analyses were conducted to assess the relationships among the continuous variables: intrinsic religiosity (objective religiosity gap), the sum of unmet R/S care needs, an unmet similar outlook on life (regretted religiosity gap), unmet R/S conversations and treatment alliance. Finally, several separate regression analyses were carried out to determine which factors predicted alliance when adjusted for sex, age, and level of depressive symptoms. For these regression analyses, the independent variables were selected based on the ANOVA and correlation analyses. The relationship between intrinsic religiosity and patients’ WAI was not linear. A curve estimation analysis revealed that a quadratic model would fit best, and therefore a quadratic term was added to the model. In addition, an analysis using groups, comparing intrinsic religiosity as well as comparing high and low intrinsic religiosity of caregivers and patients, was performed (see Table 1).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Caregivers were slightly older and less religious compared with the patients. Furthermore, caregivers rated treatment alliance higher than patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the participants.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the participants.

| Determinant | Patients | Caregivers |

|---|---|---|

| N | 55 | 55 |

| Sex (% male) | 27 | 20 |

| Age (M, SD) | 40.5 (11.7) | 44.4 (11.3) |

| Defining religious/spiritual (%) | ||

| Not spiritual, not religious | 9 | 16 |

| Spiritual, not religious | 6 | 13 |

| Religious, not spiritual | 13 | 6 |

| Spiritual and religious | 73 | 66 |

| Denomination (%) | ||

| No denomination | 29 | 36 |

| Pietistic Reformed | 31 | 16 |

| Mainline Protestant | 26 | 38 |

| Evangelical | 13 | 7 |

| Roman Catholic | 2 | 2 |

| DUREL Intrinsic Rel (M, SD) | 8.6 (3.7) | 8.0 (4.6) |

| Sum unmet R/S care needs patients (M, SD) | 2.3 (2.6) | - |

| Sum unmet R/S conversations patients (M, SD) | 0.8 (1.1) | - |

| Sum unmet similar outlook patients (M, SD) | 0.5 (0.8) | - |

| Working Alliance Inventory (WAI) | 27.0 (8.2) | 30.9 (5.1) |

3.2. ANOVA Analyses Categorical Variables

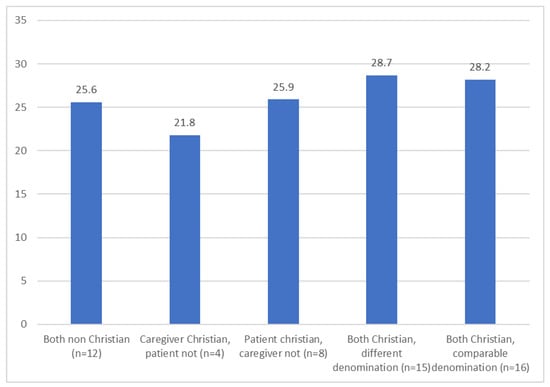

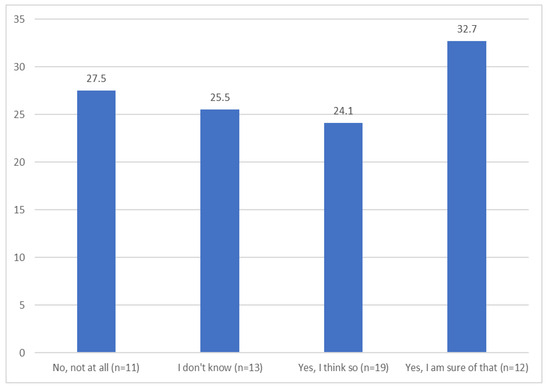

Table 3 shows that an objective difference in outlook on life, when measured by self-identification as Christian or religious, was not associated with treatment alliance, as rated by patients and caregivers. Subjective similar outlook on life was slightly related to treatment alliance as rated by patients. Objective differences in outlook on life are illustrated in Figure 1 and subjective differences as experienced by patients in Figure 2.

Table 3.

ANOVA analyses on outlook on life, alliance (WAI) for patients and caregivers, separately.

Figure 1.

Working Alliance Inventory by patients, following objective differences in outlook on life between caregivers and patients (F = 0.8; p = 0.548; df = 4, 50).

Figure 2.

Working Alliance Inventory by patients, following subjective differences: ‘My caregiver has a similar outlook on life to my own’ (F = 3.2; p = 0.031; df = 3, 51).

3.3. Correlation Analyses

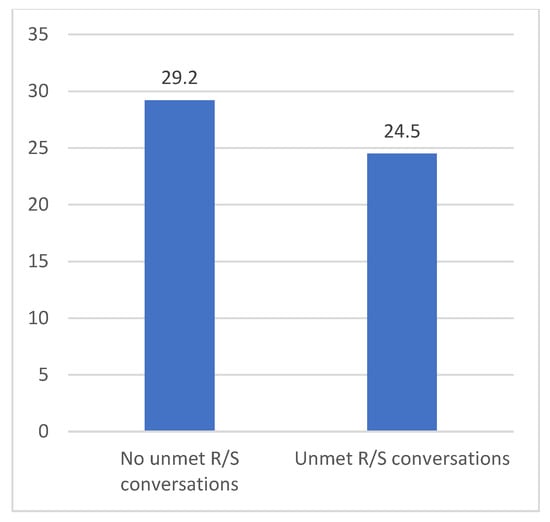

All types of unmet R/S care needs were significantly associated with the WAI as rated by patients, but not with the WAI as rated by caregivers (Table 4). The treatment alliances rated by patients and caregivers were also not associated, indicating significant differences in how patients and caregivers experienced the therapeutic relationship. The differences in scores of unmet R/S conversations (dichotomized in considering scores ≥ 1 as unmet R/S conversations) as experienced by patients are shown in Figure 3.

Table 4.

Correlations of unmet R/S care needs with treatment alliance and compliance.

Figure 3.

Working Alliance Inventory by patients, following unmet R/S conversations by patients (T = 2.2; p = 0.031; df = 53).

3.4. Regression Analyses

Table 5 shows that a subjective religiosity gap, as estimated by patients, and unmet R/S care needs, both in similar outlook on life (regretted religiosity gap) as well as R/S conversations, as experienced by patients, are significantly associated with treatment alliance, as rated by patients. The analysis of intrinsic religiosity with treatment alliance is worked out below, because of the non-linear association. All other factors were not significantly associated with treatment alliance (results on request).

Table 5.

Regression patients’ Working Alliance Inventory (WAI) in separate models ¹.

3.5. Non-Linear Regression Analysis

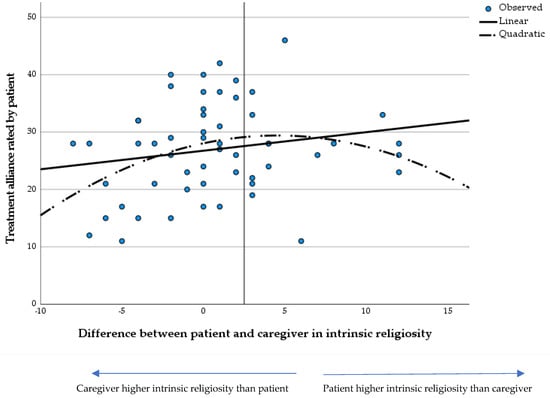

The non-linear association between intrinsic religiosity was tested by including the quadratic term of delta intrinsic religiosity in the regression analysis. This analysis revealed a significant parabolic relationship between intrinsic religiosity and treatment alliance ( intrinsic religiosity = 0.39, p = 0.018; q intrinsic religiosity = −0.38, p = 0.021). An ANOVA analysis, in which groups were divided based on a score above or below the average of 8 in intrinsic religiosity, also showed a significant relationship (Table 6). Table 1 and Figure 4 show that the difference seemed most prominent in cases in which caregivers had higher intrinsic religiosity scores than patients.

Table 6.

Groups of intrinsic religiosity and WAI.

Figure 4.

Parabolic association between the difference in intrinsic religiosity between caregivers and patients.

4. Discussion

A subjectively experienced and a regretted difference in outlook on life between patients and caregivers were significantly associated with a lower treatment alliance, as rated by patients. Objective or actual differences in outlook on life between caregivers and patients did not significantly correlate with treatment alliance, except when it concerned the comparison of scores on intrinsic religiosity. Especially when caregivers scored high on intrinsic religiosity whereas patients scored low, treatment alliance as rated by patients was significantly lower. The same association among patients with higher intrinsic religiosity than caregivers was, however, not evident. This finding may seem coincidental but aligns to some extent with findings from Rosmarin and colleagues, who observed that patients who received a religious/spiritual intervention from clinicians without religious affiliation exhibited better responses than those who received the same intervention from a religious therapist (Rosmarin et al. 2021). At the same time the current finding is the other way around and raises some questions. It may be possible that caregivers with high intrinsic religiosity overestimate their competences in spiritual care. It is also possible that they incline on their own perceptions, which could be constraining for patients.

The fact that objective differences in outlook on life did not matter when measured rather roughly (Christian or not, religious or not), but did matter when measured with intrinsic religiosity is interesting. Previous studies have suggested that the religiosity gap is bridgeable (Mayers et al. 2007; Stolovy et al. 2013). On a superficial level, this certainly seems to be the case, but apparently, deeper ways in which one views life can indeed affect the therapeutic relationship. Results hinge on how determinants are measured, and we can question whether an ‘actual’ religiosity gap indeed reflects objective differences in religiosity. A scale of intrinsic religiosity in some ways can be considered to be more subjective than religious background: the way one person interprets and completes such a questionnaire may differ from how another person does. In any case, the measure determined deeper facets of R/S, which seems important in a treatment relationship.

Subjective experiences matter most: patients’ perceptions of a religiosity gap with their caregivers were quite strongly related to the treatment alliance they experienced, which is consistent with earlier findings (van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse et al. 2021). So, a perceived religiosity gap may negatively influence treatment success, which is in line with the study by Liefbroer and Nagel (2021), who showed that the satisfaction with a conversation depended on a perceived gap and not on an actual gap, when determined by religious background. The experience of alignment of outlooks on life between patients and caregivers appears to matter. This may be a matter of underlying factors such as feeling understood, heard, seen, and respected, which can enhance a sense of connectedness, and apparently also the idea of a shared outlook on life. An aspect that may play a role in these results is the fact that in light of the changing landscape of religion within society, where individuals increasingly shape their own religious or existential frameworks, distinctions between religious and secular identities have become less rigid. As Nancy Ammerman (2014) aptly describes, there is a ‘blurring of boundaries’ between religious and secular realms. From this perspective, whether one objectively identifies as Christian or secular matters less than how individuals subjectively engage with others and approach life.

5. Implications

As shown in the same (larger) population, (un)met R/S care needs, such as the need for R/S conversations, prove to be related to treatment alliance, suggesting that integrating R/S care may be beneficial for treatment success. This has been described earlier (van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse et al. 2021), but the current study adds that the unmet R/S care needs seem to be far more important than an actual difference in outlook on life. This offers opportunities for caregivers: their own outlook on life does not matter, but finetuning the needs of patients does more. Though an actual difference in outlook on life does not seem to matter, the results of the current study do underscore the relevance of attention to religious/spiritual (R/S) aspects in treatment. However, the current study also shows that caregivers may not automatically estimate possible unmet R/S care needs adequately, since their estimation of sufficient R/S conversations was not related to any of the outcomes. In addition, caregiver-rated treatment alliance was not significantly related to any of the ‘gaps’ measured. Furthermore, caregivers consistently rated the treatment alliance higher than patients did. This finding raises several questions: do caregivers have a professional bias, valuing their own care higher than patients do? Or do these differences stem from varying expectations and perceptions of what constitutes good care and a strong treatment alliance? The discrepancy in ratings, along with the fact that caregivers’ assessments did not align with patient satisfaction, suggests a potential lack of awareness among professionals about patients’ experiences and their unmet R/S care needs. Caregivers could benefit from training to enhance their understanding of patients’ R/S care needs, which may improve the treatment alliance and overall care.

A dilemma may arise regarding caregivers’ R/S self-disclosure when paying attention to R/S. It is debatable whether the current study supports the idea that caregivers should keep their own outlook on life undisclosed. Various studies suggest that self-disclosure can benefit the treatment relationship, as shown in a meta-synthesis (Hill et al. 2018). It is important to notice that the results of the current study do not imply that self-disclosure may hinder the treatment alliance. Regarding subjective similarities in outlook, the groups ‘I don’t know’, ‘No, not at all’ and ‘Yes, I think so’ scored equally in treatment alliance, whereas only the group ‘I am sure of a religiosity match’ scored significantly higher than others. An important aspect of self-disclosure by health care providers is its ethical dimension and the questions in what way and how much personal information could be shared with patients, and in what ways self-disclosure can contribute to a healthy therapeutic relationship without crossing professional boundaries. According to the clear advice in the Position Statement on Religion, Spirituality and Psychiatry by the World Psychiatric Association, caregivers are expected not to proselytize (Moreira-Almeida et al. 2016). Regardless, objective differences did not seem to matter, but subjective experiences and regretted differences did. In this regard, it is unknown in which cases caregivers had disclosed their own views—influencing the answering rates concerning subjective similar outlook (which patients may have disliked). It is, however, also possible that different mechanisms are at stake here: outlook on life is broader than specific religious background, and caregivers may share specific norms and values, for example, that align with those of patients, enhancing the impression of a shared outlook on life for them.

6. Limitations and Recommendations

Results of the current study underscore the importance of habituating R/S integration in mental health care. Some limitations, however, need to be discussed. Whereas many patients in the current study were satisfied with R/S care, the population may not be fully representative, as they might have been more satisfied than average, agreeing to be matched with their caregiver in research. In addition, the sample was small, which made options for analyses limited. Future studies might study more representative and extended populations. Moreover, the role of self-disclosure by caregivers could be further studied, as well as the role of R/S matching in different religious and cultural populations. The effect of an institutional gap of match would also be worth studying. While the current study suggests that a match in religiosity between patient and caregiver may not be necessary for treatment success, further research could delve into the specific impact of religiosity on different facets of treatment success, such as satisfaction with care, symptom reduction, quality of life, (existential) recovery and relapse prevention. Long-term studies would be meaningful in this regard. Researchers might also investigate what happens in R/S conversations between caregivers and patients. Understanding how religiosity and spiritual beliefs influence the treatment of mental disorders is crucial for providing personalized care that meets the needs of diverse patient populations. Broadening the scope of patients’ psychosocial issues to include core values of life, such as meaning, values and ultimate importance may offer new insights into their lives. The finding that the gap lies not in a different outlook on life but in approaches to care presents opportunities for caregivers of all outlooks on life to deliver appropriate R/S care to different types of patients.

7. Conclusions

The current study results suggested that the religiosity gap—embodied as subjective experiences and regretted differences in outlook on life, as well as in unmet R/S care needs—partly can be bridged. Differences in intrinsic religiosity, however, cannot be neglected, and require openness and respect to others with a different outlook on life. As we explore the intersection of mental health care and R/S care needs, one may question whether the disparity can be bridged at all. It is vital to remember that while mental health care aims to provide support and understanding, R/S often seeks to imbue life with profound significance and purpose. In studying this gap, we must remain aware of the different aspects of care and R/S and the potential implications for the individuals seeking assistance. Ultimately, perhaps the most crucial question is not whether a religiosity gap can be bridged—in terms of fully meeting someone’s R/S care needs—but rather, whether providing appropriate assistance and acknowledging, respecting and accommodating patients’ R/S backgrounds can lead to optimal chances for treatment success.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.v.N.A.-M., A.I.L., H.S.-J. and A.W.B.; methodology, J.C.v.N.A.-M.; validation, A.I.L.; formal analysis, J.C.v.N.A.-M.; investigation, J.C.v.N.A.-M.; resources, J.C.v.N.A.-M. and A.W.B.; data curation, J.C.v.N.A.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.v.N.A.-M.; writing—review and editing, J.C.v.N.A.-M., A.I.L., H.S.-J. and A.W.B.; visualization, J.C.v.N.A.-M.; supervision, H.S.-J. and A.W.B.; project administration, J.C.v.N.A.-M.; funding acquisition, J.C.v.N.A.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Stichting tot Steun VCVGZ, no grant number available, and by the John Templeton Foundation, grant number 60667.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Altrecht Mental Health Care (CWO number 1525, 7 June 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are stored at the Center of Research and Innovation in Christian Mental Health Care.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Abernethy, Alexis D., and Joseph J. Lancia. 1998. Religion and the psychotherapeutic relationship. Transferential and countertransferential dimensions. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 7: 281–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2014. Finding Religion in Everyday Life. Sociology of Religion 75: 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetz, Marilyn, Ronald Griffin, Rudy Bowen, Harold G. Koenig, and Eugene Marcoux. 2004. The association between spiritual and religious involvement and depressive symptoms in a Canadian population. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 192: 818–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernts, Ton, and Joantine Berghuijs. 2016. God in Nederland 1966–2015. Utrecht: Ten Have. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Clara E., Sarah Knox, and Kristen G. Pinto-Coelho. 2018. Therapist self-disclosure and immediacy: A qualitative meta-analysis. Psychotherapy 55: 445–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, Adam O., and Leslie S. Greenberg. 1989. Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology 36: 223–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G., and Arndt Büssing. 2010. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): A Five-Item Measure for Use in Epidemological Studies. Religions 1: 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefbroer, Anke I., and Ineke Nagel. 2021. Does faith concordance matter? A comparison of clients’ perceptions in same versus interfaith spiritual care encounters with chaplains in hospitals. Pastoral Psychology 70: 349–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefbroer, Anke I., and Joantine Berghuijs. 2017. Religieuze en levensbeschouwelijke diversiteit in het werk van geestelijk verzorgers. Tijdschrift Geestelijke Verzorging 20: 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mayers, Claire, Gerard Leavey, Christina Vallianatou, and Chris Barker. 2007. How clients with religious or spiritual beliefs experience psychological help-seeking and therapy: A qualitative study. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice 14: 317–27. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira-Almeida, Alexander, Avdesh Sharma, Bernard Janse van Rensburg, Peter J. Verhagen, and Christopher C. H. Cook. 2016. WPA Position Statement on Spirituality and Religion in Psychiatry. World Psychiatry 15: 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouwehand, Eva, Arjan W. Braam, Janwillem Renes, Hanneke J. K. Muthert, Hanne A. Stolp, Heike H. Garritsen, and Hetty T. H. Zock. 2019. Prevalence of Religious and Spiritual Experiences and the Perceived Influence Thereof in Patients with Bipolar Disorder in a Dutch Specialist Outpatient Center. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 207: 291–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosmarin, David H., and Steven Pirutinsky. 2020. Do religious patients need religious psychotherapists? A naturalistic treatment matching study among orthodox Jews. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 69: 102170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosmarin, David H., Sarah Salcone, David G. Harper, and Brent Forester. 2021. Predictors of Patients’ Responses to Spiritual Psychotherapy for Inpatient, Residential, and Intensive Treatment (SPIRIT). Psychiatric Services 72: 507–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinckens, Nele, Annick Ulburghs, and Laurence Claes. 2009. De werkalliantie als sleutelelement in het therapiegebeuren. Tijschrift Voor Klinische Psychologie 39: 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Stolovy, Tail, Yvan Moses Levy, Adiel Doron, and Yuval Melamed. 2013. Culturally sensitive mental health care: A study of contemporary psychiatric treatment for ultra-orthodox Jews in Israel. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry 59: 819–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, Joke C., Hanneke Schaap-Jonker, Carmen Schuhmann, Christa Anbeek, and Arjan W. Braam. 2018. The ‘religiosity gap’ in a clinical setting: Experiences of mental health care consumers and professionals. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 21: 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, Joke C., Hanneke Schaap-Jonker, Christa Anbeek, and Arjan W. Braam. 2021. Religious/spiritual care needs and treatment alliance among clinical mental health patients. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 28: 370–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, Joke C., Hanneke Schaap-Jonker, Gerlise Westerbroek, Christa Anbeek, and Arjan W. Braam. 2020. Conversations and Beyond: Religious/Spiritual Care Needs Among Clinical Mental Health Patients in the Netherlands. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 208: 524–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vertommen, Hans, and Geert A. C. Vervaeke. 1990. Werkalliantievragenlijst (WAV). Vertaling Voor Experimenteel Gebruik van de WAI (Dutch Translation of the Working Alliance Inventory for Experimental Use). Leuven: De partement Psychologie, K.U. Leuven. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).