Approach to Psychic Wholeness: Psychoanalytic Theory in Daoist Supreme Deity Talismans of XuHuo

Abstract

1. Introduction

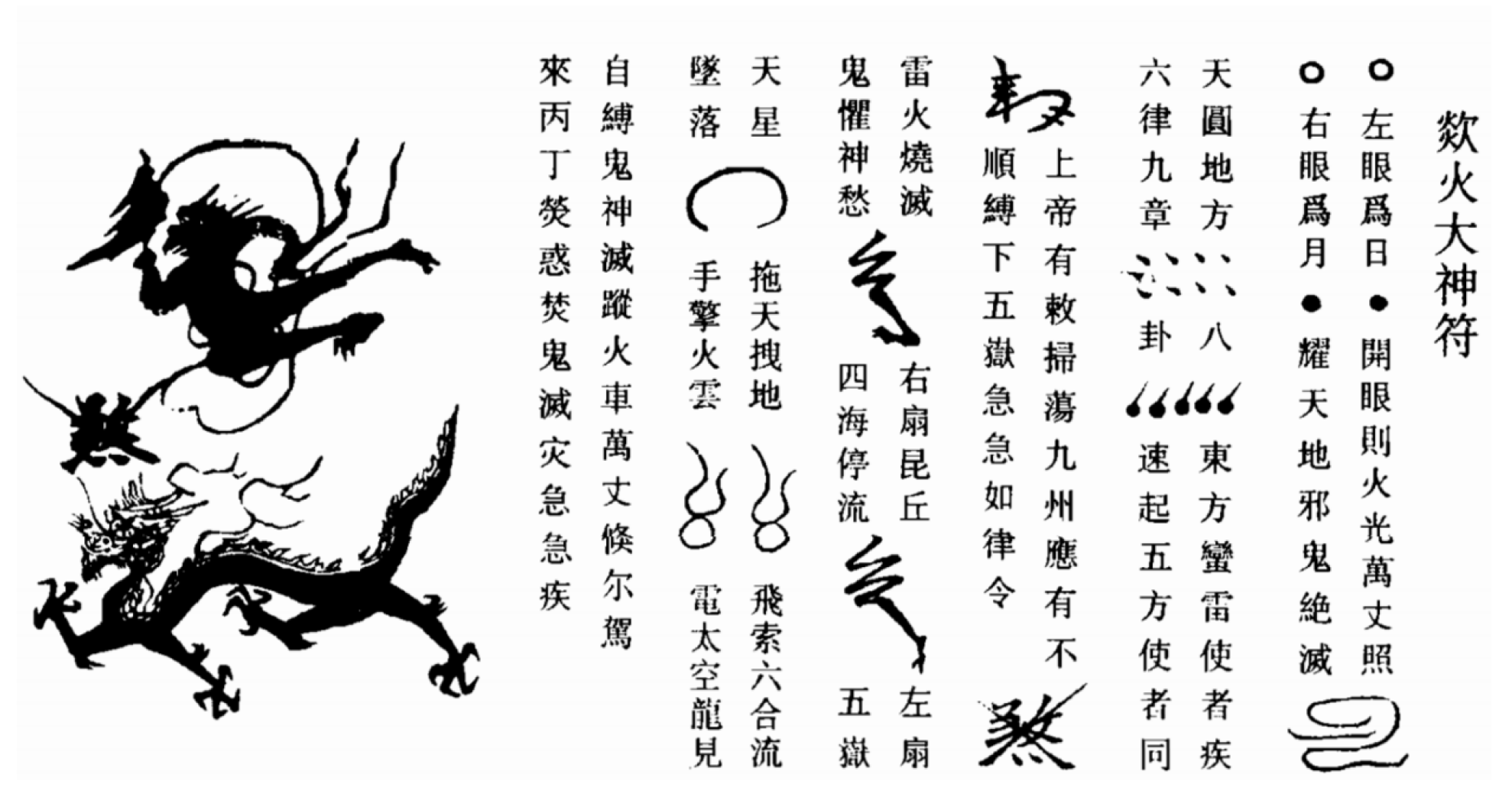

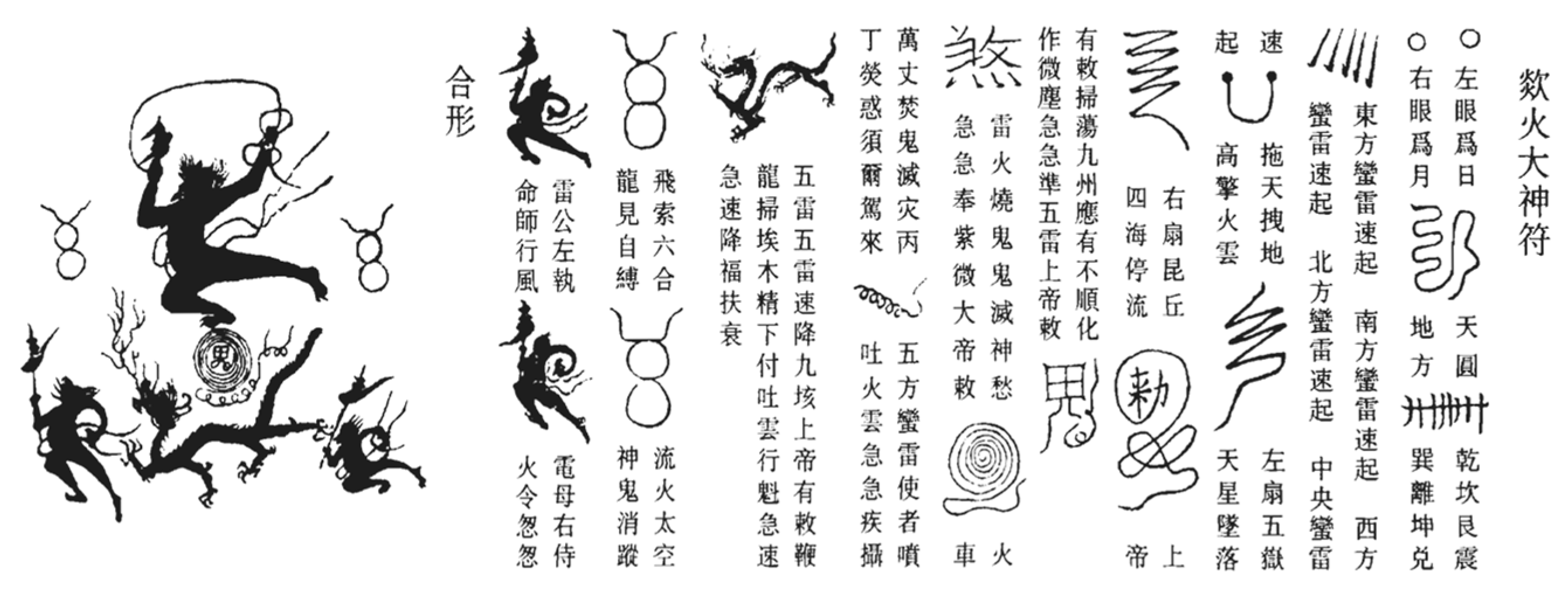

2. The Elements of the SDTXH: The Symbolic Expression of the Collective Unconscious

= the Sun and the Moon; the left eye represents the Sun, while the right eye signifies the Moon.

= the Sun and the Moon; the left eye represents the Sun, while the right eye signifies the Moon.  = when the eyes are opened, the flames will radiate brilliantly, casting a luminous glow upon heaven and Earth, thereby banishing malevolent spirits.

= when the eyes are opened, the flames will radiate brilliantly, casting a luminous glow upon heaven and Earth, thereby banishing malevolent spirits.  = round sky and square Earth.

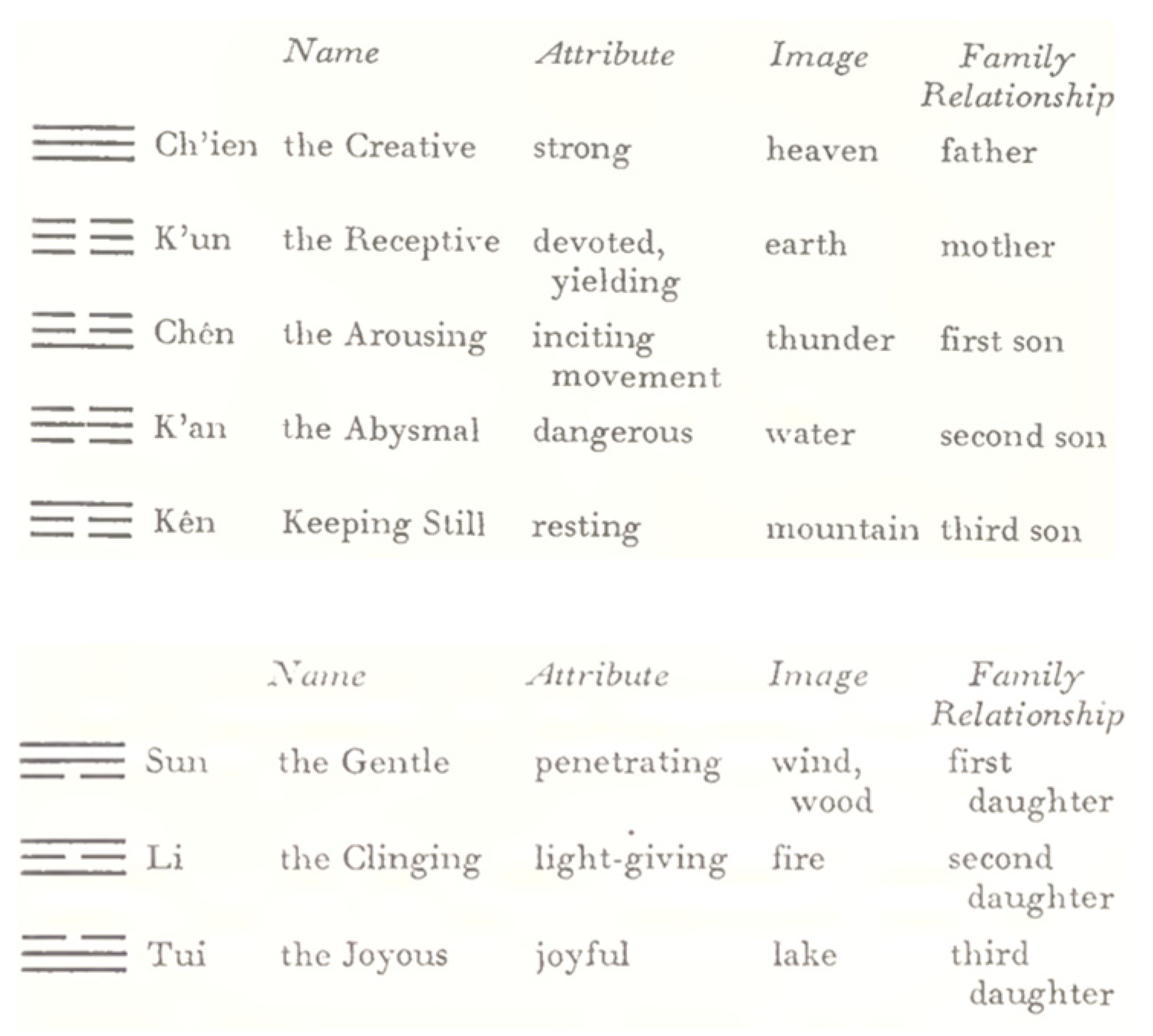

= round sky and square Earth. = the eight trigrams.

= the eight trigrams. = the Thor.

= the Thor. = the exaggerated distortion of the Chinese character 敕 (chi).

= the exaggerated distortion of the Chinese character 敕 (chi). = the exaggerated distortion of the Chinese character 煞 (sha).

= the exaggerated distortion of the Chinese character 煞 (sha). = supernatural power.

= supernatural power. = the “cloud of fire”.

= the “cloud of fire”. = the Thor spewed out a cloud of fire.

= the Thor spewed out a cloud of fire.  = using a whip to coerce the dragon (loong) into producing rain.

= using a whip to coerce the dragon (loong) into producing rain. = fire, the Thor.

= fire, the Thor. = wind, the Electric Mother.

= wind, the Electric Mother.2.1. The Heavenly Lord Deng as a Heroic Archetypal Image in the SDTXH

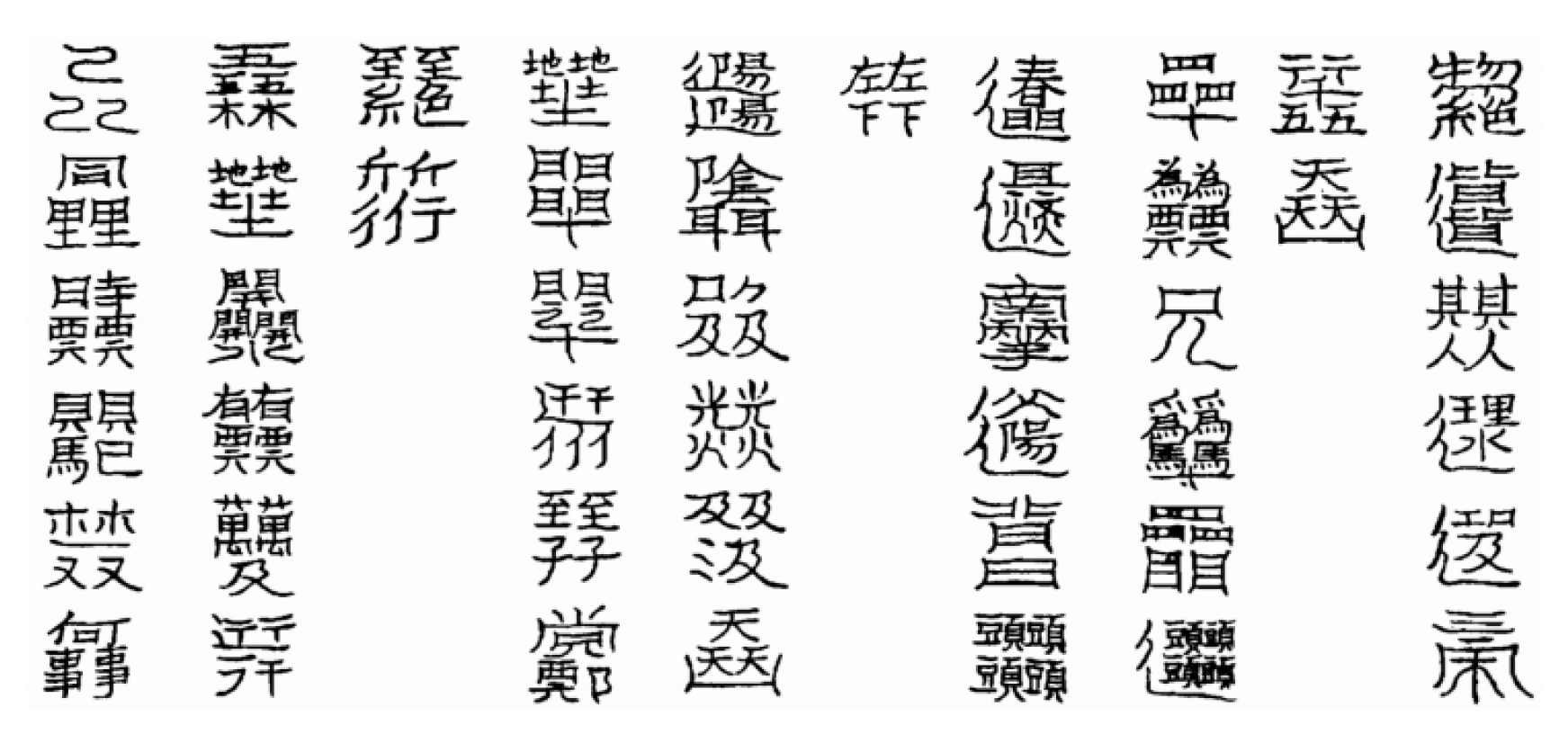

2.2. Chinese Characters as Readable Archetypal Images in the SDTXH

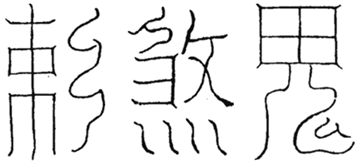

, tian (天), di (地), ren (人), and the exaggerated distortion of gui (鬼) (Wushang xuanyuan santian yutang dafa 1988, pp. 95–96), and the plague-exorcism talisman5, utilizing the exaggerated distortion of wen (瘟) (Shangqing tianxin zhengfa 1988, p. 628), among others, demonstrate this evolution. Additionally, later Daoism introduced simpler talismans consisting of a single Chinese character, such as chi, sha, and gui (鬼)6 (Shangqing tianxin zhengfa 1988, p. 617) and so forth.

, tian (天), di (地), ren (人), and the exaggerated distortion of gui (鬼) (Wushang xuanyuan santian yutang dafa 1988, pp. 95–96), and the plague-exorcism talisman5, utilizing the exaggerated distortion of wen (瘟) (Shangqing tianxin zhengfa 1988, p. 628), among others, demonstrate this evolution. Additionally, later Daoism introduced simpler talismans consisting of a single Chinese character, such as chi, sha, and gui (鬼)6 (Shangqing tianxin zhengfa 1988, p. 617) and so forth. 2.3. The Hexagrams as Brilliant Archetypal Images in the SDTXH

3. Active Imagination: A Way to the Generation of the SDTXH

4. Fuqiao: The Secret of the Generation of the SDTXH

5. The Self: The Root of the Generation of the SDTXH

6. Sandplay Therapy: The Process of the Generation of the SDTXH

6.1. Both Approaches Have a Designated Safe, Free, and Protected Space

6.2. The Constituent Elements of the SDTXH Exhibit Remarkable Similarities to the Miniature Models Used by the Clients in Sandplay Therapy

6.3. Both “Speak” in Symbolic Language That Is Consistent with the Unconscious

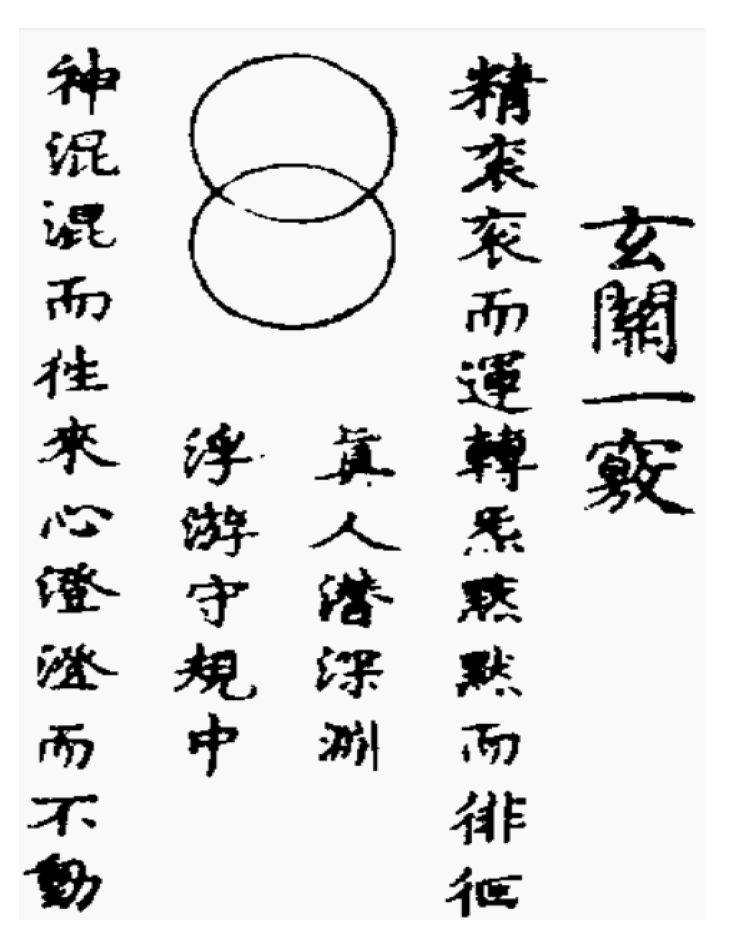

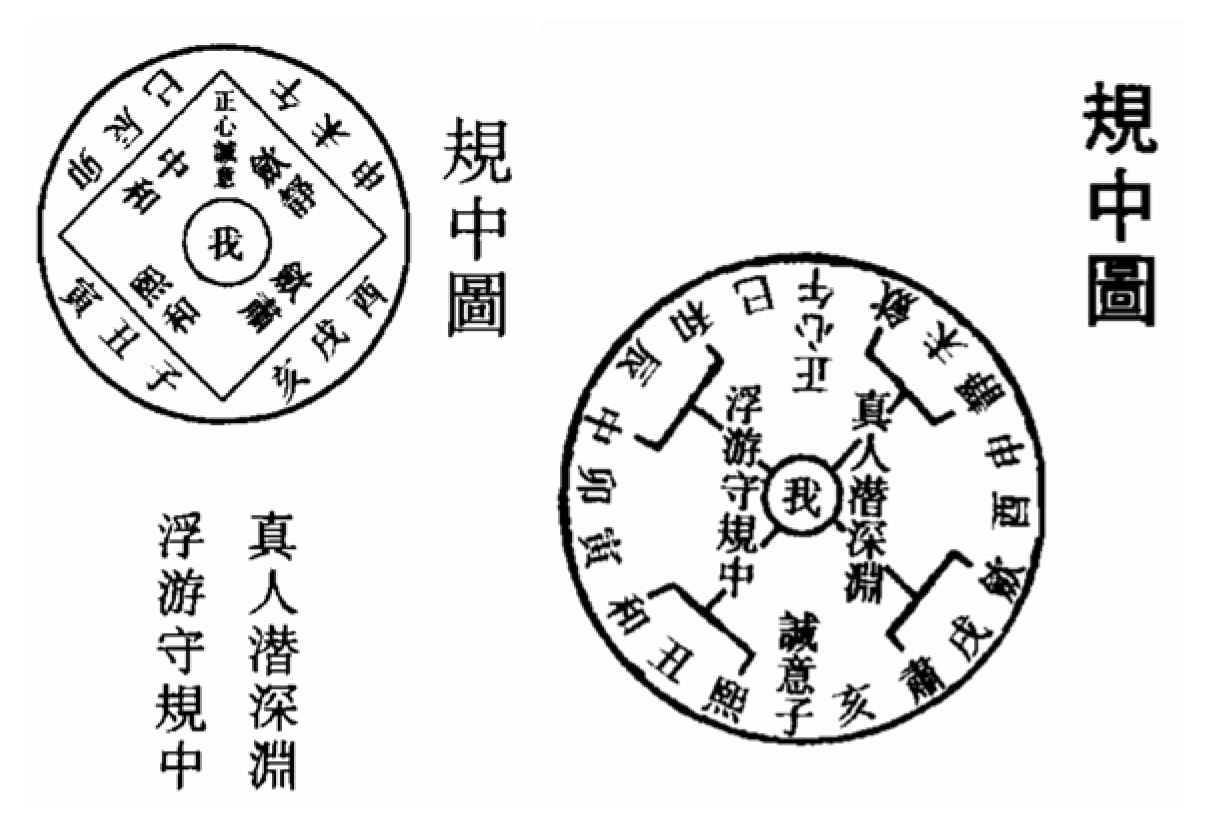

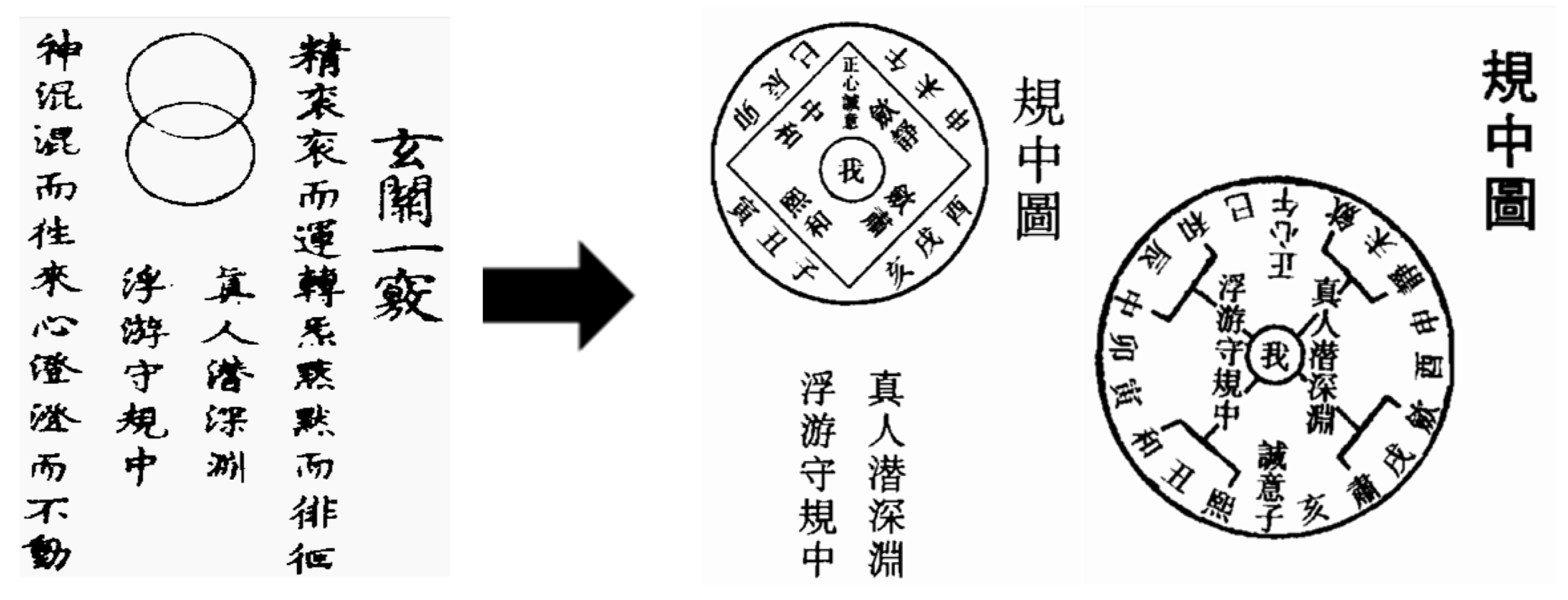

6.4. Both Believe That the Emergence of the Circle Is a Key Indicator of Achieving Psychic Wholeness

. This represents the supreme Dao, the primal qi of the universe. It encompasses heaven and earth, embracing all spirits. This is the essence of the gathered golden light, commanding the presence of divine spirits. When inscribing talismans onto paper, one begins with the symbol of qian (乾), reverses its direction, and ultimately returns to qian (乾) to complete the cycle. Subsequently, within this circular image, a single dot is inscribed, embodying the profound essence. The single dot represents Yangjing, one’s primordial spirit. Its radiance is boundless, filling the vastness of the universe. Subsequently, based on one’s personal intention, the talismans are inscribed onto it freely. 凡書符篆之先, 必聚精會神, 於杳冥恍惚之際, 運先天一點明靈, 隨念而昇, 結三花於頂上, 攢兩曜於眉間, 注睛迸光, 作一圓象:

. This represents the supreme Dao, the primal qi of the universe. It encompasses heaven and earth, embracing all spirits. This is the essence of the gathered golden light, commanding the presence of divine spirits. When inscribing talismans onto paper, one begins with the symbol of qian (乾), reverses its direction, and ultimately returns to qian (乾) to complete the cycle. Subsequently, within this circular image, a single dot is inscribed, embodying the profound essence. The single dot represents Yangjing, one’s primordial spirit. Its radiance is boundless, filling the vastness of the universe. Subsequently, based on one’s personal intention, the talismans are inscribed onto it freely. 凡書符篆之先, 必聚精會神, 於杳冥恍惚之際, 運先天一點明靈, 隨念而昇, 結三花於頂上, 攢兩曜於眉間, 注睛迸光, 作一圓象: 此大道也, 先天一炁也。包羅天地, 總括萬靈。所謂金光四集, 曷敢不臨之義也。或書符於紙上, 則起乾, 逆轉復歸乾而止, 然後於圓象中復作一點, 妙在其中矣。此陽精也, 自己元辰也。晃曜無邊, 充塞宇宙。然後隨意書符於其上 (Daofa huiyuan 1988b, p. 211).

此大道也, 先天一炁也。包羅天地, 總括萬靈。所謂金光四集, 曷敢不臨之義也。或書符於紙上, 則起乾, 逆轉復歸乾而止, 然後於圓象中復作一點, 妙在其中矣。此陽精也, 自己元辰也。晃曜無邊, 充塞宇宙。然後隨意書符於其上 (Daofa huiyuan 1988b, p. 211).7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In the eyes of ancient Chinese people, talismans were believed to possess inherent magical powers. The earliest evidence of this belief can be traced to the mawangdui (馬王堆) texts, specifically the “Recipes for Fifty-Two Ailments” (wushier bingfang, 五十二病方). The text recommends, for instance, that “when someone ails from gu, incinerate a north-facing paired talisman. Then steam sheep buttock, drop (the buttock) into hot bath water, and toss in the talisman ash. Then, the ailing person, and wash the hair and body to treat the gu” (Harper 1997, p. 301). The religious organization of Daoism emerged during the Eastern Han dynasty (25AD–220AD). Strickmann noted that “Disease and its cure are a paramount focus in the earliest accounts of Daoism” (Strickmann 2002, p. 1). The ritual of curing illnesses with talismans, grounded in Daoist beliefs, became the primary method for early Daoism to attract followers, indicating that the talismans’ inherent magical powers were still widely believed in during that time. During the Wei, Jin, Southern, and Northern dynasties (220AD–589AD), Daoists further proposed that talismans were formed by the condensation of Congenital Energy (xiantian qi, 先天炁). Consequently, talismans were viewed as another manifestation of the Dao, possessing supernatural powers, and were further sanctified within Daoism. This laid the foundation for the integration of Inner Alchemy and talismans. Since the Tang dynasty (618AD–960AD), Daoists have discovered an effective path to breach the barrier between heaven and man—the cultivation of Inner Alchemy. It was in this context that talismans were regarded as products of Inner Alchemy cultivation. |

| 2 | Qi (energy, 炁) refers to the ontological form of the Dao. In Daoist thought, there is indeed a close relationship between Dao and qi. Specifically, Dao signifies the origin and fundamental laws of nature in the universe, representing an intangible force and existence. Qi represents the energy that exists throughout the universe. In Daoist philosophy, qi is the manifestation and dynamic flow of Dao in the material world. Consequently, qi can be viewed as embodiment of Dao, representing its concrete manifestation and implementation. In Daoist practices, individuals aim to achieve harmony with the Dao through the regulation and cultivation of their own qi. |

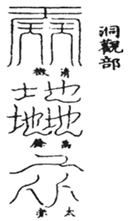

| 3 | The following figure is the talisman named Dongguanbu (洞觀部) (Gaoshang shenxiao yuqing zhenwang zishu dafa 1988, p. 580).  |

| 4 | The following figure is the talisman named curing children’s fright (治小兒驚符) (Wushang xuanyuan santian yutang dafa 1988, pp. 95–96).  |

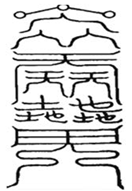

| 5 | The following figure is the talisman named plague-exorcism (退瘟符) (Shangqing tianxin zhengfa 1988, p. 628).  |

| 6 | The following figure includes some simpler talismans consisting of single Chinese characters (Shangqing tianxin zhengfa 1988, p. 617).  |

| 7 | When writing talismans, one must maintain a pure and tranquil mindset, devoid of any distracting thoughts. 凡書符時, 須心地清靜, 無有雜念 (Qingwei yuanjiang dafa 1988, p. 278). |

| 8 | For those who engage in writing talismans, the sole requirement is to have a settled mind, unperturbed by external affairs… In this way, when the brush touches the paper, the spirit remains unwavering and the energy remains undisturbed. 書符者, 惟要心定, 不思外事… 庶幾下筆時, 神不走炁不亂。 (Tianhuang zhidao taiqing yuce 1988, p. 379). |

| 9 | When engaging in the writing of talismans and inscriptions, one must first concentrate the mind and stabilize the thoughts, attaining a state of forgetfulness of both the self and the world. 凡書符篆, 先凝神定慮, 物我兩忘。 (Daofa huiyuan 1988a, p. 689). |

| 10 | In the context provided, “this tendency” should refer to Jung’s belief “that, in the overdevelopment of the conscious intellect—the ‘monotheism of consciousness’, as he called it—modern Western culture has allowed itself to be cut off from its instinctual roots in the unconscious” (Clarke 2000, p. 126). |

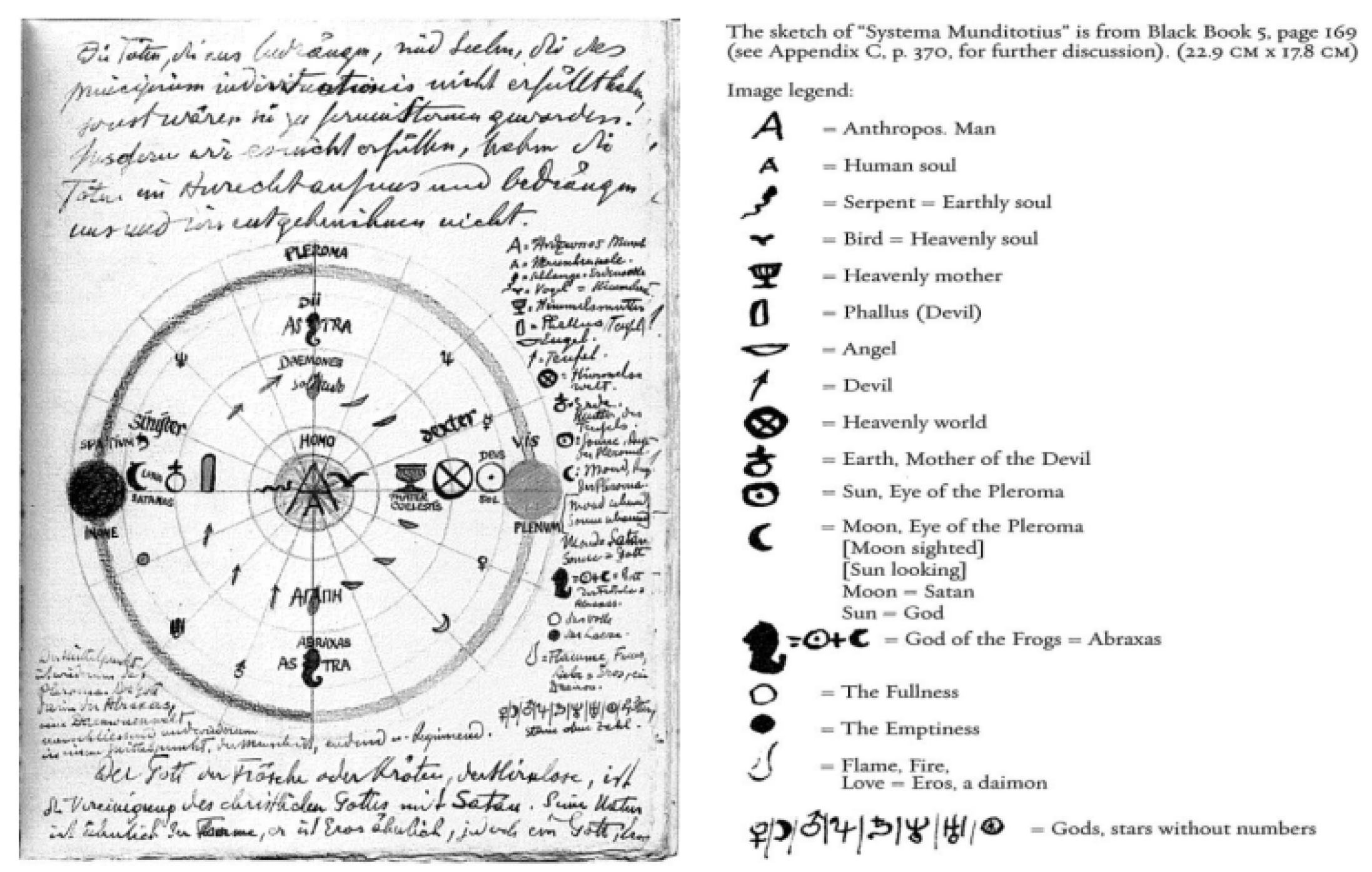

| 11 | The sketch of “Systema Munditotius” can be considered as a combination of the aforementioned “The Supreme Deity Talismans of XuHuo” (Figure 1 and Figure 2), Fuqiao (Figure 5), and Guizhong charts (Figure 6). The constituent elements of the sketch of “Systema Munditotius” are listed in the “image legend” and primarily include Anthropos Man, Human Soul, Serpent (Earthly Soul), Bird (Heavenly Soul), Heavenly Mother, Phallus (Devil), Angel, Devil, Heavenly World, Earth (Mother of the Devil), Sun (Eye of the Pleroma), (Sun, Eye of the Pleroma), God of the Frogs (Abraxas), the Fullness, the Emptiness, Flames, Fire, Love, and Gods (stars without numbers). |

References

- Chen, Lin 陳林. 2002. “Book from Heaven” or “paint from Ghost “—Talk about the Daoist talismans “天書” 還是“鬼畫符”—道教符籙漫談. The World Religious Cultures 世界宗教文化 1: 43–44. [Google Scholar]

- Chongxu tongmiao shichen wangxiansheng jiahua 冲虚通妙侍宸王先生家話. 1988. Daozang 道藏. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press, Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House, vol. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, John James. 2000. The Tao of the West: Western Transformations of Taoist Thought. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Daofa huiyuan 道法會元. 1988a. Daozang 道藏. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press, Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House, vol. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Daofa huiyuan 道法會元. 1988b. Daozang 道藏. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press, Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House, vol. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Lan 高嵐, and Heyong Shen 申荷永. 2000. Chinese characters and psychological archetypes 漢字與心理原型. Journal of Psychological Science 心理科學 3: 377–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gaoshang shenxiao yuqing zhenwang zishu dafa 高上神霄玉清真王紫書大法. 1988. Daozang 道藏. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press, Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House, vol. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, Donald J. 1997. Early Chinese Medical Literature: The Mawangdui Medical Manuscripts. London and New York: Kegan Paul International. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl Gustav. 1956. Symbols of transformation. In The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Edited by Herbert Read, Michael Fordham and Gerhard Adler. Translated by Richard Francis Carrington Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl Gustav. 1961. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl Gustav. 1966. Spirit in man, art, and litefrature. In The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Edited by Herbert Read, Michael Fordham and Gerhard Adler. Translated by Richard Francis Carrington Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, vol. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl Gustav. 1969a. Archetype and collective unconscious. In The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Edited by Herbert Read, Michael Fordham and Gerhard Adler. Translated by Richard Francis Carrington Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl Gustav. 1969b. Psychology and Religion: West and East. In The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Edited by Herbert Read, Michael Fordham and Gerhard Adler. Translated by Richard Francis Carrington Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl Gustav. 1969c. Structure & dynamics of the psyche. In The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Edited by Herbert Read, Michael Fordham and Gerhard Adler. Translated by Richard Francis Carrington Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl Gustav. 1970. Civilization in transition. In The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Edited by Herbert Read, Michael Fordham and Gerhard Adler. Translated by Richard Francis Carrington Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl Gustav. 1971. Psychological Types. In The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Edited by Herbert Read, Michael Fordham and Gerhard Adler. Translated by Richard Francis Carrington Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl Gustav. 1976. The Symbolic Life: Miscellaneous Writings. In The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Edited by Herbert Read, Michael Fordham and Gerhard Adler. Translated by Richard Francis Carrington Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, vol. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl Gustav. 2009. The Red Book. Edited by Sonu Shamdasani. Translated by Mark Kyburz, John Peck, and Sonu Shamdasani. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Kalff, Dora M. 2003. Sandplay: A Psychotherapeutic Approach to the Psyche. Cloverdale: Temenos Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sujung. 2022. A Star God Is Born: Chintaku Reifujin Talismans in Japanese Religions. Religions 13: 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yuanguo 李遠國. 1998. On the structure and brushwork of Daoist talismans 論道符的結構與筆法. Religious Studies 宗教學研究 2: 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Jing 林靜. 2020. The changes in shape and structure of Daoist talismans and their historical turn in the Song dynasty 宋代道符形制的變化及其歷史轉向. Religious Studies 宗教學研究 2: 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lingbao wuliang duren shangpin miaojing 靈寶无量度人上品妙經. 1988. Daozang 道藏. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press, Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Zhongyu 劉仲宇. 2013. The Discussion on Fu and Lu 符籙平話. Beijing: China Religious Culture Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Rie Rogers, and Harriet S. Friedman. 1994. Sandplay: Past, Present and Future. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, Xitai 卿希泰. 1995. On the problems of Qingwei School and Quanzhen Dao in Wudang Mountain 武當清微派與武當全真道的問題. Social Science Research 社會科學研究 6: 31–34+70. [Google Scholar]

- Qingwei yuanjiang dafa 清微元降大法. 1988. Daozang 道藏. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press, Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter, Florian C. 2007. Basic Conditions of Taoist Thunder Magic. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Zongquan 任宗權. 2012. Research on Daoist “zhang” 章, “biao” 表, symbol, seal, and other culture 道教章表符印文化研究. Beijing: China Religious Culture Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Shangqing tianxin zhengfa 上清天心正法. 1988. Daozang 道藏. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press, Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House, vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Heyong 申荷永, and Lan Gao 高嵐. 2019. Jung and Chinese Culture 榮格與中國文化. Beijing: Capital Normal University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shweder, Richard A., Jacqueline J. Goodnow, Giyoo Hatano, Robert A. LeVine, Hazel R. Markus, and Peggy J. Miller. 1998. The cultural psychology of development: One mind, many mentalities. In Handbook of Child Psychology. Theoretical Models of Human Development. Edited by William Damon and Richard M. Lerner. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., vol. 1, p. 779. [Google Scholar]

- Strickmann, Michel. 2002. Chinese Magical Medicine. Edited by Bernard Faure. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taiping jing 太平經. 1988. Daozang 道藏. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press, Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House, vol. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Taishang chiwen dongshen sanlu 太上赤文洞神三籙. 1988. Daozang 道藏. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press, Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House, vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Tianhuang zhidao taiqing yuce 天皇至道太清玉册. 1988. Daozang 道藏. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press, Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House, vol. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhendong, and Fengyan Wang. 2020. The Taiji Model of Self II: Developing Self Models and Self-Cultivation Theories Based on the Chinese Cultural Traditions of Taoism and Buddhism. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 540074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, Burton. 2013. The Complete Works of Zhuangzi. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, Richard. 1962. The Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book of Life. With a Foreword and Commentary by C. G. Jung. Translated by Cary F. Baynes. New York: Harcourt Brace and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, Richard. 1967. The I Ching or the Book of Changes. With a Foreword by C. G. Jung. Translated by Cary F. Baynes. Bollingen Series XIX. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Adelina Wei-Kwan. 2018. Ancient Chinese Hieroglyphs: Archetypes of Transformation. Jung Journal 12: 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wushang xuanyuan santian yutang dafa 无上玄元三天玉堂大法. 1988. Daozang 道藏. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press, Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Jiyu 張繼禹. 2004a. Daozang of China 中華道藏. Beijing: Huaxia Publishing House, vol. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Jiyu 張繼禹. 2004b. Daozang of China 中華道藏. Beijing: Huaxia Publishing House, vol. 36. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, F. Approach to Psychic Wholeness: Psychoanalytic Theory in Daoist Supreme Deity Talismans of XuHuo. Religions 2024, 15, 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060683

Liu F. Approach to Psychic Wholeness: Psychoanalytic Theory in Daoist Supreme Deity Talismans of XuHuo. Religions. 2024; 15(6):683. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060683

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Fang. 2024. "Approach to Psychic Wholeness: Psychoanalytic Theory in Daoist Supreme Deity Talismans of XuHuo" Religions 15, no. 6: 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060683

APA StyleLiu, F. (2024). Approach to Psychic Wholeness: Psychoanalytic Theory in Daoist Supreme Deity Talismans of XuHuo. Religions, 15(6), 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060683