Bodhisattva and Daoist: A New Study of Zhunti Daoren 準提道人in the Canonization of the Gods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Zhunti Daoren as a Daoist Deity

As he lifted his sword to behead Ma Yuan, Heavenly Master heard someone shouting behind him, “Brother of the Way! Have mercy on the life under your sword”.He turned and saw a man in Daoist robes with a yellowish face, two coils of hair, and a short beard. The man greeted him politely.“Where do you come from and what can I do for you, my friend of the Way?” Heavenly Master asked as he returned his greeting.文殊廣法天尊舉劍纔待要斬馬元, 只聽得腦後有人叫曰: 道兄劍下留人! 廣法天尊回顧, 認不得此人是誰: 頭挽雙髻, 身穿道服, 面黃微須. 道人曰: 稽首了! 廣法天尊答禮, 口稱: 道友何處來? 有甚事見諭?

| Zhunti climbed up the mountain and shouted, “Kong Xuan! Would you dare to come out to see me?” |

| Kong Xuan rushed out and saw a man arriving in a peculiar way. Why? There is a poem on him: |

| Clad in Daoist robes, with a branch in hand. |

| By the Eight Virtues Pond, the Way is preached, beneath the Seven Precious Trees, the Three Vehicles are expounded. |

| Holy relics overhead, wordless scriptures by hand. |

| Elegantly drifting as a true guest of the Way, exquisite and truly extraordinary. |

| Ascending to the Western world, dwelling in the superior realm, attaining eternal life, leaving the dusty world. |

| The lotus body manifests infinite wonders, the head of the West and great immortal is coming. |

| 話說準提道人上嶺, 大呼曰: 請孔宣答話! 少時, 孔宣出營, 見一道人來得蹊蹺. 怎見得? 有偈為證, 偈曰: |

| 身披道服, 手執樹枝. |

| 八德池邊常演道, 七寶林下說三乘. |

| 頂上常懸舍利子, 掌中能寫沒文經. |

| 飄然真道客, 秀麗實奇哉. |

| 煉就西方居勝境, 修成永壽脫塵埃. |

| 蓮花成體無窮妙, 西方首領大仙來 (Z. Xu 1992, p. 203). |

The foreman of the lay workers (daoren 道人) from the temple arrived early in the morning, at the fifth watch, bearing with him the sutras that would be used in the liturgy. He prepared the consecrated space in which the ceremony would be held and hung up Buddhist effigies.道人頭五更, 就挑了經擔來, 鋪陳道場, 懸掛佛像.

3. Zhunti Daoren as a Buddhist Deity

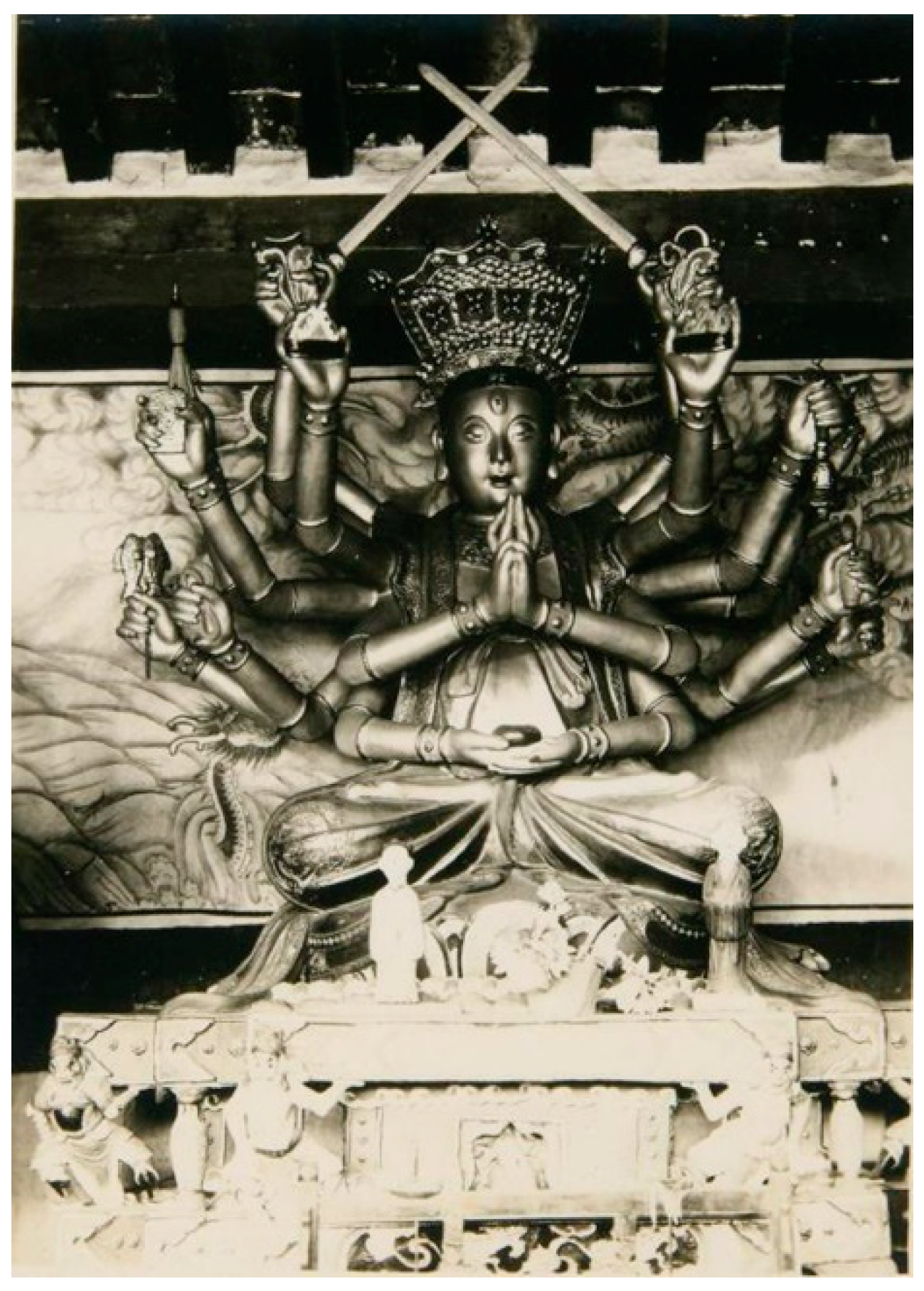

An explosion rang out from Kong Xuan’s light beams, and Zhunti Daoren appeared on his back with twenty-four heads and eighteen arms, holding a necklace of gems, a parasol, a vase, fish intestines, a precious vajra, a precious rasp, a gold bell, a gold bow, a silver spear, a pennant, and many other precious objects.只聽得孔宣五色光裡一聲雷響, 現出一尊聖像來, 十八隻手, 二十四首, 執定瓔珞, 傘蓋, 花罐, 魚腸, 加持神杵, 寶銼, 金鈴, 金弓, 銀戟, 旛旗等件.

Zhunti then transformed himself into a figure with twenty-four heads and eighteen arms, holding a necklace of gems, a parasol, a vase, fish intestines, a gold bow, a silver spear, a precious vajra, a precious rasp, a gold bottle, and many other precious objects. They all surrounded the Grand Master of Heaven in a fighting circle.準提現出法身, 有二十四首, 十八隻手, 執定了瓔珞, 傘蓋, 花貫, 魚腸, 金弓, 銀戟, 加持神杵, 寶銼, 金瓶, 把通天教主裹在當中.

She also wears goddess robes, a necklace of gems, and a crown; her arms are encircled with conch-shaped bangles; and on her little fingers are jeweled rings. The image has a face with three eyes and her arms number eighteen. Her two topmost hands make the preaching gesture. On the right, the second hand makes the fear-quelling gesture, the third holds a sword, the fourth a jeweled banner, the fifth a citron fruit, the sixth an axe, the seventh a goad, the eighth a vajra, and the ninth a rosary. On the left, the second hand holds a wish-fulfilling gem pennant, the third a red lotus blossom in full bloom, the fourth an aspergillum, the fifth a cord, the sixth a wheel, the seventh a conch, the eighth an auspicious vase, and the ninth a sūtra box.復有天衣角絡, 瓔珞, 頭冠, 臂環皆著螺釧, 檀慧著寶環. 其像面有三目, 十八臂. 上二手作說法相, 右第二手作施無畏, 第三手執劍, 第四手持寶鬘, 第五手掌俱緣果, 第六手持鉞斧, 第七手執鉤, 第八手執金剛杵, 第九手持念珠, 左第二手執如意寶幢, 第三手持開敷紅蓮花, 第四手軍持,第五手罥索, 第六手持輪, 第七手商佉, 第八手賢瓶, 第九手掌般若梵夾.(Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 1983, T20, no. 1076, p. 184c7–26. Translated by Gimello (2004, pp. 226–27))

| Cundī Bodhisattva was born in the Western Pure Land, with deep-rooted virtues and immeasurable wonders. |

| The lotus leaf turns exquisite when there is wind, while the lotus flower stands firm without any rain. |

| The golden bow and silver spear are not weapons, as the precious vajra and fish intestines have other wondrous functions. |

| Do not say that Kong Xuan can transform, while under the Bodhi tree, Cundī is known as the Wisdom King. |

| 準提菩薩產西方, 道德根深妙莫量. |

| 荷葉有風生色相, 蓮花無雨立津梁. |

| 金弓銀戟非防患, 寶杵魚腸另有方. |

| 漫道孔宣能變化, 婆娑樹下號明王 (Xinke 1994, p. 1857). |

4. Zhunti Daoren as the Panchen Lama

5. Zhunti Daoren and Pure Land Buddhism

Rulai (Tathāgata) requested that Yaoshi (Bhaiṣajyaguru), Jieyin, Zhunti, Shizhi (Mahāsthāmaprāpta), and other friends of the Way accompany them, leading them through the Western Hall, and respectfully inviting them to a banquet in the garden.如來命藥師, 接引, 准提, 勢至諸道侶相陪, 踅過西方殿, 恭邀入園筵宴.

[Jieyin’s] body is the color of gold, with an incomparably good appearance and brightness. He vows to save all sentient beings through forty-eight vows, and [in his light] there are immeasurable billions of transformed Bodhisattvas. He descends to the mortal realm on the second day after the winter solstice to enlighten the multitudes. He is the pure and tranquil Amitābha Buddha of infinite life, the welcoming Master. [Zhunti’s] heart is filled with compassion, widely extending protection. He once manifested his Dharma body, with three heads and eighteen arms, known as Susiddhi, who is the Great Cundī.身如金色, 相好光明, 度眾生以四十八願, 化菩薩以眾億無邊, 每於冬至後二日, 化度下方, 是為清靜無量壽接引大師阿彌陀佛. 心惟慈悲, 廣垂加護, 嘗變現法身, 三頭十八臂, 一名蘇悉帝, 是為大准提.

The Cundī Method of Developing One’s Wisdom (Zhunti huiye 準提慧業) in the Ming-Dynasty Buddhist Canon attaches special emphasis to the function of the six-syllabled Sanskrit incantation, which differs from the teachings of Amitābha, Avalokiteśvara, and Mahāsthāmaprāpta. It is likely that, based on the teachings of the Western Pure Land, the Dharma Prince Mahāsthāmaprāpta and his fellow disciples guide believers who chant the name of Amitābha Buddha to the Pure Land. There, they are joined by fifty-two Bodhisattvas, of which Cundī is one.明藏經有准提慧業以六梵字為用, 與無量壽及觀世音大勢至所說不同. 蓋西方之教, 大勢至法王子與其同門攝念佛人歸於淨土,至有五十二菩薩, 故准提亦其一耳.

| I now recite the [name of] the Great Cundī, and immediately vow to attain great enlightenment. |

| May my meditation and wisdom swiftly become perfected, and may my virtues be completely fulfilled. |

| May my merit and blessings be universally adorned, and may I together with all beings attain Buddhahood. |

| The myriad karmic misdeeds that I had committed in the past, are all resultant from my primordial attachment, aversion, and delusion. |

| They came into being from my body, speech, and mind, I now repent and penance all of them. |

| May all obstacles be removed when I approach the end of life. |

| May I behold the Buddha Amitābha, and be reborn in the peaceful and joyous Pure Land. |

| 我今持誦大准提, 即發菩提廣大願. |

| 願我定慧速圓明, 願我功德皆成就. |

| 願我勝福遍莊嚴, 願共眾生成佛道. |

| 我昔所造諸惡業, 皆由無始貪嗔癡. |

| 從身語意之所生, 一切我今皆懺悔. |

| 願我臨欲命終時, 盡除一切諸障礙. |

| 面見彼佛阿彌陀, 即得往生安樂剎 (Manji shinsan dainihon zokuzōkyō 1975–1989, X59, no. 1077, p. 229c13–19). |

A girl of the Wu family, from Taicang, was born in a meditation position. As she grew older, she embraced the Buddhist faith with unwavering devotion and demonstrated exemplary filial piety, eschewing the pursuit of a household life. When advised otherwise, she adamantly pointed to the sky as a solemn pledge. Initially engaging in the study of the meaning of characters under the tutelage of her peers, she later delved into the recitation of Buddhist scriptures, achieving a profound understanding of their essence. She devoutly worshiped day and night. She then had a dream in which a deity bestowed upon her the Sanskrit Cundī Mantrā. Utilizing the Sanskrit characters, she miraculously cured a person afflicted with malaria, who immediately recovered. In another dream, she received a revelation regarding her destiny, disclosing her past incarnation as a distinguished monk in the Song Dynasty and her return to fulfill her filial duties, with the prophecy that she would gain enlightenment at the age of twenty-three. In the fourth year of the Chongzhen period, at the age of twenty-three, she secluded herself in a chamber, dedicating herself to the Pure Land practice. Towards the end of midwinter, she exhibited signs of a minor ailment and composed a verse urging her parents to persevere in their practice. At noon, she requested to wear a jade ring and then passed away while lying on her right side.吳氏女, 太倉人. 生時趺坐而下. 稍長, 皈心佛乘, 事親孝, 不願有家, 人或勸之, 輒指天為誓. 初從昆弟析諸字義, 已而誦佛經, 悉通曉大意. 朝夕禮拜甚䖍. 俄夢神授以梵書準提呪, 有病瘧者, 以梵字治之, 立愈. 嘗於夢中得通宿命, 自言曾為宋高僧, 此來專為父母, 年二十三當成道果. 崇禎四年, 年二十三矣, 閉關一室, 專修淨土. 仲冬之末, 示微疾, 作偈辭世, 勉親堅修勿懈. 日方午, 索玉戒指佩之, 右脅而逝.(Manji shinsan dainihon zokuzōkyō 1975–1989, X78, no. 1549, p. 312c9–16)

Liu Chongqing, a Provincial Graduate of Yongfeng, had a fondness for the philosophy of Chan Buddhism and recited the Great Cundī Mantrā every morning regardless of the weather, without interruption for over twenty years. In his later years, he became an Instructor in the Confucian School of Lushan. One day, while bedridden, he saw a radiating white light in the room, within which the image of Great Cundī appeared for several days. As he neared the end of his life, he vividly saw the Bodhisattva present a white object resembling a full moon, seemingly with the intention of welcoming him. Liu promptly sat up, recited the Great Compassion Mantrā, and passed away.永豐孝廉劉崇慶, 雅好禪理, 每晨起持大準提咒, 寒暑不輟, 垂二十餘年. 晚授魯山學博. 一日臥病, 見室中放白毫光, 現大準提相者數日. 將逝, 惺然見菩薩出一白物如滿月, 恍示以接引之意. 劉遽起趺坐, 誦大悲咒訖而逝.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Based on the edition published by Shu Zaiyang 舒載陽 (n.d.), Zhunti Daoren appears in Chapter 61, Chapter 65, Chapter 70, Chapter 71, Chapter 78, Chapter 79, Chapter 82, Chapter 83, and Chapter 84. |

| 2 | However, Europeans first encountered the goddess Zhunti much earlier. China Illustrata, a book compiled by the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680) and published in 1667, demonstrates seventeenth-century European knowledge regarding the Chinese Empire and its neighboring countries. It includes an illustration of Zhunti seated on a lotus, supported by two dragon kings (Kircher 1987, p. 128). |

| 3 | Interestingly, on his personal website, Barend ter Haar warns his students not to consult Henri Doré’s work because, in his view, it is a “plagiarized version of Chinese research by a fellow Jesuit priest (Pierre Hoang 黃伯祿 (1830–1909), so to speak), with horrible westernized illustrations”. Nonetheless, Henri Doré was the first scholar to record the legend of Zhunti Daoren. Moreover, the so-called “westernized illustrations” are actually not so much “westernized” but rather greatly influenced by the style of traditional Chinese “new year paintings” (Nianhua 年畫) and “paper horses” (Zhima 紙馬) (Shen 2011; Tao 2011). See Barend ter Haar’s personal website, accessed 17 October 2022, https://bjterhaa.home.xs4all.nl/chinrelbibl.htm. |

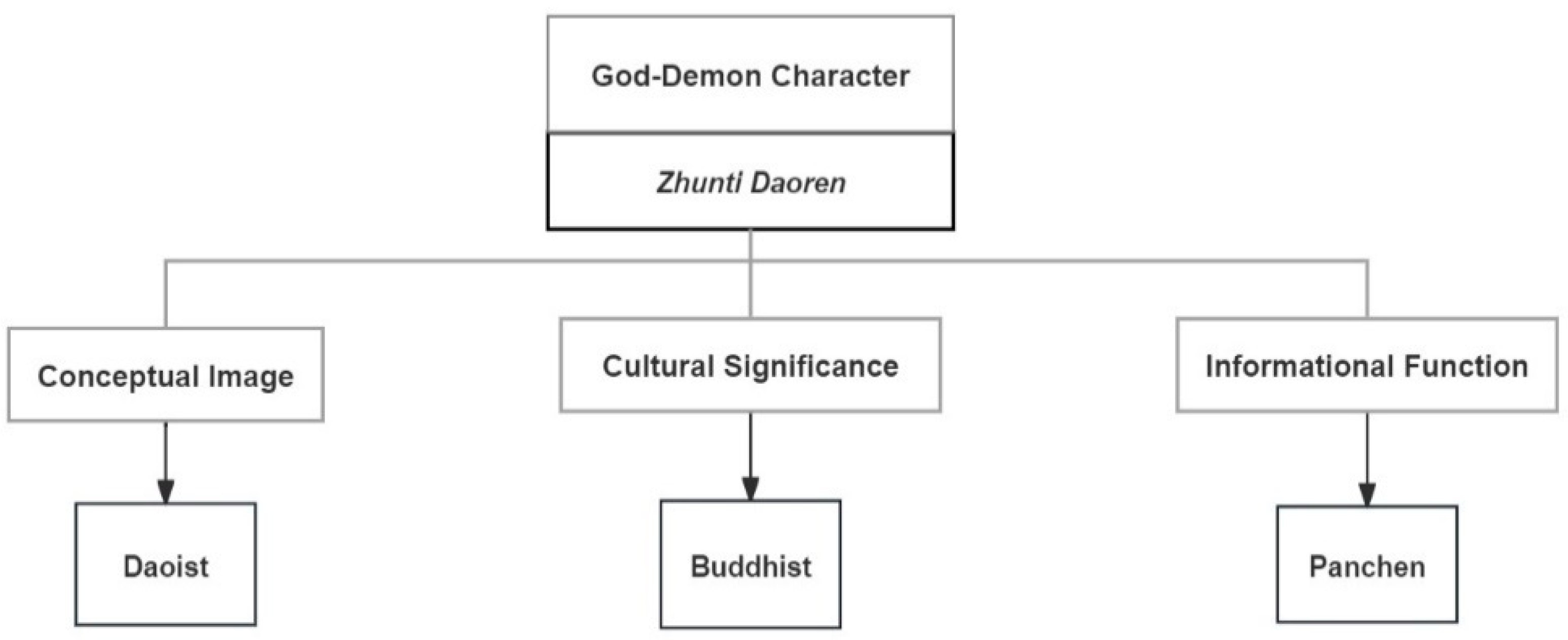

| 4 | Feng Ruchang’s A Stylistic Study of Chinese Novels of Gods and Demons is a pivotal work that adeptly amalgamates Western stylistic theories with the distinct characteristics inherent in Chinese God-Demon novels. Feng delineates three evolutionary stages in the development of these novels—original works, imitations, and sequels—each characterized by unique stylistic nuances. Moreover, Feng proposes an innovative theoretical framework for the interpretation of the God-Demon figure. Despite the profound depth and originality of this approach, it has yet to receive adequate recognition within the sphere of contemporary scholarship. Consequently, the application of Feng’s analytical framework to the character, Zhunti Daoren, fulfills a dual purpose: it not only exemplifies the practicality of Feng’s model in the analysis of intricate characters but also emphasizes the pressing necessity for a more robust scholarly engagement with Feng’s work. |

| 5 | The discourse surrounding the origins of characters in Canonization is tantamount to exploring the interplay between the novel’s mythological universe and its contemporary religio-cultural context. There is a divergence in scholarly perspectives on these aspects. One faction of scholars, exemplified by the likes of Liu (1962, p. Ⅶ), accentuates the author’s innovative use of mythology. Conversely, another faction, with Mark Meulenbeld (2015, pp. 208–9) as a notable representative, places emphasis on the influences of contemporaneous religio-cultural realities, with particular attention to the impacts of local pantheons. An important distinction lies in the latter faction’s focus on the portrayal of martial deities within the novel. This study, however, espouses a more centrist position, advocating for a nuanced, case-by-case examination of these elements. |

| 6 | Notwithstanding the absence of additional elucidation from Feng, drawing upon Hirsch’s (1967, p. 8) differentiation between significance and meaning, I presume that there are two types of “conceptual images”—the conceptual image of the author vis-à-vis the reader. |

| 7 | This study employs Gu Zhizhong’s 顧執中translation of "Tianzun" as "Heavenly Master" from his version of Canonization. This departs from the usual academic convention—using "Heavenly Worthy" for "Tianzun"—to maintain consistency and avoid confusion due to the extensive use of Gu’s translations in this paper. |

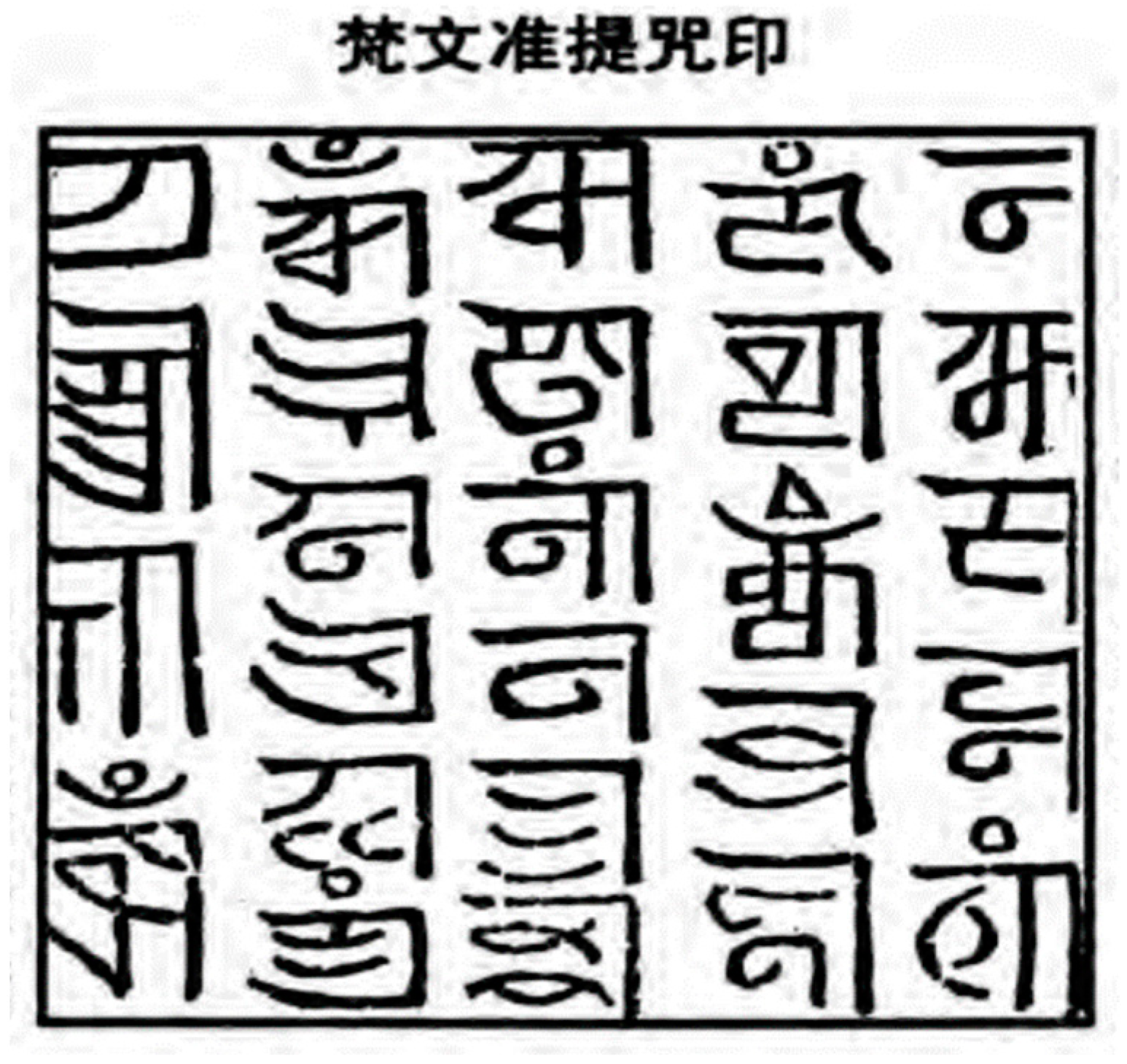

| 8 | It should be noted, however, that the incantation on the seal is carved in the Lantsha script, indicating that it is highly unlikely that this seal has been passed down from the Tang Dynasty. |

| 9 | On Xianmi’s significant influence on the later Zhunti cult, see Gimello (2004, pp. 231–39), Lü Jianfu 呂建福 (Lü 2011, pp. 547–48), and Hsieh Shu-wei 谢世维 (Hsieh 2018, pp. 203–22). |

| 10 | Based on the “Inscription on the Great Singing Spring Temple” (Damingquanmiao ji 大鳴泉廟記) written by Guo Mian 郭勉 (n.d.), a prefect of Zhending 真定 Prefecture during the Ming Dynasty, the Great Singing Spring Temple was established in 1374 by Manager of Affairs Li (zhongshu pingzhang ligong 中書平章李公, 1339–1384) to express gratitude to the God of the Great Singing Spring for nourishing the nearby population. Nonetheless, the identity of this "God of the Great Singing Spring" remains ambiguous. Another inscription (carved in 1572) celebrating the reconstruction of the temple indicates that the only deity worshiped in the Great Singing Spring Temple was a dragon king, who had a lifelike statue and was famous for great efficacy.Yet, in 1702, some 130 years later, when Zhou Bushi 周卜世 (?–1705) assumed the position of prefect, the Peacock Buddha Pavilion (Kongque foge 孔雀佛閣), housing the statue of Zhunti Daoren astride a peacock, was already established. This suggests that the statue was very likely sculpted during the period from 1572 to 1702 (W. Zhao 2006, pp. 166, 171–72). |

| 11 | For a brief history of the cult of Zhunti in China, see Gimello (2004, pp. 225–39) and Lei (2016, 2023). |

| 12 | In South, Southeast, and Central Asia, and in the Tibetan cultural realm, Cundī has taken multiple forms. There are images of her with only two arms as well as others with four, six, eight, twelve, sixteen, eighteen, and twenty-four arms (Gimello 2004, pp. 227–28). |

| 13 | The intricate relationship between Zhunti and Guanyin presents a captivating subject that invites deeper examination. Gimello posits that Kāraṇḍavyūha might be the origin of the tradition that identifies Zhunti with Guanyin, a perspective countered by Alexander Studholme who asserts that there is no explicit evidence in this scripture, suggesting Zhunti as an incarnation of Guanyin. Studholme’s viewpoint is seemingly endorsed by others who concur that while an undeniable link exists, it would be overly simplistic and essentialist to equate Zhunti and Guanyin directly. Additionally, the concept of the “Six Avalokiteśvaras” (Roku Kannon 六観音), which includes Cundī Avalokiteśvara (Juntei Kannon 准胝観音), is worth noting. Two facets deserve special focus: initially, the origin of the Six Avalokiteśvaras concept can be traced back to China, but it didn’t develop into as prominent a cult as it did in Japan, perhaps due to the waning influence of Esoteric Buddhism in China. Secondly, in the Tendai School’s representations of the Six Avalokiteśvaras group, Juntei is replaced by Amoghapāśa (Fukū kenjaku 不空絹索), indicating a significant shift in the assembly composition. For further references, see Gimello (2004, p. 250), Studholme (2002, p. 59), Fowler (2017, p. 24), and Zhang Wenliang 張文良 (W. Zhang 2015, pp. 191–93). |

| 14 | In the same vein, Meulenbeld (2015, pp. 208–9) rejects the notion of Canonization as an entirely original creation and argues that many of the seemingly fictional characters are taken directly from the existing pantheons. |

References

- Anonymous. 2013. The Plum in the Golden Vase; or, Chin P’ing Mei. Translated by David Tod Roy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, Gu 班固. 1962. Hanshu 漢書 [History of the Former Han Dynasty]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, Samuel. 1871. A Catena of Buddhist Scriptures from the Chinese. London: Trübner & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Liao 陳遼. 1987. “Daojiao he fengshenyanyi” 道教和封神演義 [Daoism and the Canonization of the Gods]. Jilin daxue shehui kexue xuebao 吉林大學社會科學學報 [Jilin University Journal Social Sciences Edition] 5: 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Xingyu 陈星宇. 2012. “Fengshenyanyi zhong zhuntidaoren xingxiang yu zhuntixinyang” 封神演义中准提道人形象与准提信仰 [The Image of the Zhunti Daoist in the Canonization of the Gods and the Cult of Zhunti]. Zongjiaoxue yanjiu 宗教学研究 [Religious Studies] 1: 167–72. [Google Scholar]

- Doré, Henri. 1915. Researches into the Superstitions of the Chinese. Translated by Martin Kennelly. Shanghai: Tusewei, vol. VII. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Baoshan 馮保善. 2008. Qingfeng zhebuzhu de jimo yu paihuai: Mingqing shanren shiren qunluo de wenhua jiedu 青峰遮不住的寂寞與徘徊: 明清山人詩人群落的文化解讀 [The Unconcealed Loneliness and Wandering of the Azure Peaks: A Cultural Interpretation of the Poet Communities among the Hermit Scholars of the Ming and Qing Dynasties]. Shanghai: Shanghai yinyue xueyuan chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Ruchang 馮汝常. 2009. Zhongguo shenmo xiaoshuo wenti yanjiu中國神魔小說文體研究 [A Stylistic Study of Chinese Novels of Gods and Demons]. Shanghai: Sanlian shudian. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, Sherry. 2017. Accounts and Images of Six Kannon in Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gimello, Robert. 2004. Icon and Incantation: The Goddess Zhunti and the Role of Images in the Occult Buddhism of China. In Images in Asian Religions: Texts and Contexts. Edited by Phyllis Granoff and Koichi Shinohara. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, pp. 225–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Lansheng 顧蘭生, ed. 1975. Guangfeng xianzhi 廣豐縣志 [Gazetteer of Guangfeng]. In Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 中國方志叢書 [Collection of Chinese Local Gazetteers]. Taipei: Chengwen chubanshe, vol. 265. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Xuyang 郭旭陽. 2011. “Yanyonghe chongkan zhangsanfengji kaoshu” 閻永和重刊張三丰全集考述 [A Study of Yan Yonghe’s Reprint of the Complete Works of Zhang Sanfeng]. Wudang xuekan 武當學刊 [Journal of Wudang Studies] 1: 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, Eric Donald. 1967. Validity in Interpretation. London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hodous, Lewis, and William Edward Soothill. 2014. A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Xiongguan 侯雄覌, and Musheng Zhang 張木生, eds. 2008. Shaanxi yaoxian daxiangshan zhi 陝西耀縣大香山志 [The Gazetteer of the Great Fragrant Hills in Yao County, Shaanxi]. Tongchuan: Yaozhou quwei shizhiban. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Shu-wei 谢世维. 2018. Daomifayuan—daojiao yu mijiao zhi wenhua yanjiu道密法圓—道教與密教之文化研究 [Syncretic Traditions of Daoism and Esoteric Buddhism: A Study on Daoist and Esoteric Buddhist Cultures]. Taipei: Xinwenfeng chuban gongsi. [Google Scholar]

- Iser, Wolfgang. 1993. The Fictive and the Imaginary: Charting Literary Anthropology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Dinghan 金鼎漢. 1993. “Fengshenyanyi zhong jige yu yindu youguan de renwu” 封神演義中幾個與印度有關的人物 [Several Characters in the Canonization of the Gods Related to India]. Nanya yanjiu 南亞研究 [South Asia Studies] 3: 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Reginal. 1913. Buddhist China. London: Soul Care Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kircher, Athanasius. 1987. China Illustrata. Translated by Charles Don Vantuyl. Muskogee: Indian University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Jifu 藍吉富. 2013. Zhunti fa hui 準提法彙 [The Collection of Cundī Dharma]. Xinpei: Quanfo chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Tianyu. 2016. A Study of the Cult of Zhunti in the Ming–Qing Literature. Master’s dissertation, National University of Singapore, Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Tianyu. 2023. Always Being with Her Practitioners: A Study of the Diversified Devotional Practices of the Cult of Zhunti 準提 in Late Imperial China (1368–1911). Journal of Chinese Religions 51: 207–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jianwu 李建武, and Guixiang Yin 尹桂香. 2007. “Bainian fengshenyanyi yanjiu pinglun” 百年封神演義研究評論 [Commentary on the Past Century of Research on the Canonization of the Gods]. Zhongnan minzu daxue xuebao 中南民族大學學報 [Journal of South-Central Minzu University (Humanities and Social Sciences)] 4: 159–63. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Li’an, Zikai Zhang, Zong Zhang, and Haibo Li. 2011. Sida pusa yu minjian xinyang 四大菩薩與民間信仰 [The Four Great Bodhisattvas and Popular Religions]. Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Shuhui 李樹輝. 2006. “Shilun hanchuanfojiao de xijian” 試論漢傳佛教的西漸 [An Examination of the Westward Spread of Chinese Buddhism]. Xinjiang shifan daxue xuebao 新疆師範大學學報 [Journal of Xinjiang Normal University (Edition of Philosophy and Social Sciences)] 4: 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xiaorong 李小榮. 2003. Dunhuang mijiao wenxian lungao 敦煌密教文獻論稿 [On Dunhuang Esoteric Buddhism Manuscripts: A Collection of Essays]. Beijing: Renmin wenxue chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Ts’un-yan. 1962. Buddhist and Taoist Influences on Chinese Novels. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Jianfu 呂建福. 2011. Zhongguo mijiao shi 中國密教史 [The History of Esoteric Buddhism in China]. Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Meulenbeld, Mark. 2015. Demonic Warfare: Daoism, Territorial Networks, and the History of a Ming Novel. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Osabe, Kazuo 長部和雄. 1975. “Sokuten Bukō jidai no Mikkyō” 則天武后時代の密教 [Esoteric Buddhism in the Era of Empress Wu Zetian]. Mikkyō bunka 密教文化 [Esoteric Buddhism Culture] 111: 45. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Baiqi 潘百齊. 2000. “Lun fengshenyanyi de daojiao wenhua hanyun” 論封神演義的道教文化涵蘊 [The Daoist Cultural Implications in the Canonization of the Gods]. Mingqing xiaoshuo yanjiu 明清小說研究 [Journal of Ming-Qing Fiction Studies] 2: 182–90. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Hong 沈泓. 2011. Neihuang nianhua zhilü內黃年畫之旅 [The Journey of Neihuang New Year Paintings]. Beijing: Zhongguo shidai jingji chubanhe. [Google Scholar]

- Shimasaki, Ekiji 島崎役治. 1932. Ajia taikan 亞細亞大觀 [Panorama of Asia]. Dairen: Ajia shashin taikansha, vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Studholme, Alexander. 2002. The Origins of Oṃ Manipadme Hūṃ: A Study of Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- T. Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新修大蔵経 [Taishō Tripitaka]. 1983. Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎, Watanabe Kaigyoku 渡辺海旭, et al. 100 vols. Reprint. Taipei: Xinwenfeng chuban gongsi.

- Tada, Kōshō 多田孝正. 2014. Tendai Bukkyō to Higashi Ajia no Bukkyō girei 天台仏教と東アジアの仏教儀礼 [Tendai Buddhism and Buddhist Rituals in East Asia]. Tokyo: Shunjūsha. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Siyan 陶思炎. 2011. Jiangsu zhima 江蘇紙馬 [Jiangsu Paper Horses]. Nanjing: Dongnan daxue chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Chang 王昶. 2000. Jinshi cuibian 金石萃編 [Anthology of the Essence of Bronze and Stone]. In Zhongguo lidai shike ziliao huibian 中國歷代石刻資料彙編 [Compilation of Chinese Stone Inscriptions Across Historical Periods]. Beijing: Beijing tushuguan chubanshe, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Fuzhi 王夫之. 1964. Zhuangzi jie 莊子解 [Interpretation of Zhuangzi]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Guiyuan 王貴元, and Guigang Ye 葉桂剛. 1993. Shi ci qu xiaoshuo yuci dadian 詩詞曲小說語辭大典 [The Comprehensive Dictionary of Terms in Poetry, Lyrics, Drama, and Novels]. Beijing: Qunyan chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Pinpin. 1987. Investiture of the Gods (‘Fengshen yanyi’): Sources, Narrative Structure, and Mythical Significance. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Juxian 衛聚賢. 1982. Fengshenbang gushi tanyuan 封神榜故事探源 [Exploring the Origins of the Stories in the Canonization of the Gods]. In Zhongguo gudian xiaoshuo yanjiuziliao huibian 中國古典小說研究資料彙編 [Compilation of Research Materials on Chinese Classical Novels]. Edited by Chuanyu Zhu 朱傳譽. Taipei: Tianyi chubanshe, vol. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Weishan yizu huizu zizhixian xianzhi bianweihui bangongshi 巍山彝族回族自治县县志编委会办公室. 1989. Weibaoshan zhi 巍寶山志 [The Gazetteer of the Weibao Mountain]. Kunming: Yunnan renmin chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Cheng’en. 2012. The Journey to the West. Translated by Anthony C. Yu. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- X. Manji shinsan dainihon zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本続蔵経 [Manji Newly Compiled Continuation of the Japanese Tripitaka]. 1975–1989. Edited by Kawamura Kōshō 河村孝照. 90 vols. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai.

- Xiao, Zixian 蕭子顯. 1972. Nanqi shu 南齊書 [History of the Southern Qi]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Xinke zhongbojing xiansheng piping fengshenyanyi 新刻鐘伯敬先生批評封神演義 [New Edition of Mr. Zhong Bojing’s Critique on the Canonization of the Gods]. 1994, In Guben xiaoshuo jicheng 古本小說集成 [Compilation of Classical Novels]. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, no. 4. vol. 78.

- Xu, Dao 徐道. 1995. Lidai shenxian yanyi 歷代神仙演義 [Comprehensive Mirror of Successive Divine Immortals]. Shenyang: Liaoning guji chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Zhonglin 許仲琳. 1992. Creation of the Gods. Translated by Zhizhong Gu 顧執中. Beijing: New World Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Keqiao 薛克翹. 2016. Shenmo xiaoshuo yu yindu mijiao 神魔小說與印度密教 [The Novels of Gods and Demons and Indian Tantric Buddhism]. Beijing: Zhongguo dabaikequanshu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, Kazuo 山下一夫. 1999. “Fengshenyanyi xifangjiaozhu kao” 《封神演義》西方教主考 [A Study of the Hierarch of Xifang jiao in the Canonization of the Gods]. Yuanguang xuebao圓光學報 [Yuan Kuang Journal of Buddhist Studies] 3: 242–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagita, Kunio 柳田國男. 1985. Chuanshuo lun 傳說論 [On Legends]. Translated by Xiang Lian 連湘. Beijing: Zhongguo minjian wenyi chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Sen 楊森. 2009. “Lüetan fojiaotu cheng daoren he daojiaotu cheng daoren” 略談佛教徒稱道人和道教徒稱道人 [Brief Discussion on Daoren in Buddhism and Daoism]. In Fojiao yishu yu wenhua guoji xueshu yantaohui lunwenji 佛教藝術與文化國際學術研討會論文集 [Proceedings of the International Academic Symposium on Buddhist Art and Culture]. Edited by Binglin Zheng 鄭炳林. Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe, pp. 282–311. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Qinliang 曾勤良. 1984. Taiwan minjianxinyang yu fengshenyanyi zhi bijiaoyanjiu 台灣民間信仰與封神演義之比較研究 [A Comparative Study of the Popular Religions in Taiwan and the Canonization of the Gods]. Taipei: Huazheng shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Jian 張箭. 2013. “Fengshenyanyi renwu zhi qiyi zuoqi quankao” 封神演義人物之奇異坐騎全考 [A Comprehensive Study of the Unique Mounts of the Characters in the Canonization of the Gods]. Changjiang wenming 長江文明 [Yangtze River Civilization] 2: 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Wenliang 張文良. 2015. Riben dangdai fojiao 日本當代佛教 [Contemporary Japanese Buddhism]. Beijing: Zongjiao wenhua chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Er’xun 趙爾巽. 1977. Qingshi gao 清史稿 [Draft Qing History]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, vol. 474. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Wenlian 趙文濂. 2006. Guangxu zhengding xianzhi (光緒)正定縣志 [The Gazetteer of Zhengding County in the Guangxu Period]. Nanjing: Jiangsu guji chubenshe. [Google Scholar]

| Name | Place of Enlightenment (Daochang 道場) | Ride |

|---|---|---|

| Heavenly Master of Outstanding Culture | Yunxiao Cave (yunxiao dong 雲霄洞) in the Wulong Mountain (wulong shan 五龍山) | Green lion (qingshi 青獅) |

| Immortal of Universal Virtue (puxian zhenren 普賢真人) | Baihe Cave (baihe dong 白鶴洞) in the Jiugong Mountain (jiugong shan 九宮山) | White elephant (baixiang 白象) |

| Immortal of Merciful Navigation (cihang daoren 慈航道人) | Luojia Cave (luojia dong 落伽洞) in the Putuo Mountain (putuo shan 普陀山) | Golden Hou (jinmao hou 金毛犼) |

| Zhunti Daoren | None | None |

| Name | Place of Enlightenment | Ride |

|---|---|---|

| Mañjuśrī | Mount Wutai | Green lion |

| Samantabhadra | Mount E’mei | White elephant |

| Avalokiteśvara | Mount Putuo | Golden Hou |

| Cundī | None | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lei, T. Bodhisattva and Daoist: A New Study of Zhunti Daoren 準提道人in the Canonization of the Gods. Religions 2024, 15, 680. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060680

Lei T. Bodhisattva and Daoist: A New Study of Zhunti Daoren 準提道人in the Canonization of the Gods. Religions. 2024; 15(6):680. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060680

Chicago/Turabian StyleLei, Tianyu. 2024. "Bodhisattva and Daoist: A New Study of Zhunti Daoren 準提道人in the Canonization of the Gods" Religions 15, no. 6: 680. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060680

APA StyleLei, T. (2024). Bodhisattva and Daoist: A New Study of Zhunti Daoren 準提道人in the Canonization of the Gods. Religions, 15(6), 680. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060680