Formation Fit for Purpose: Empowering Religious Educators Working in Catholic Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To what extent do religious educators understand how to successfully implement the Religious Education curriculum?

- How successful are they at eliciting the appropriate understandings and interpretations of the Church’s mission?

- And, most importantly, to what degree do religious educators actually value the Church’s identity and mission?

2. The Catholic Religious Educator

3. A Local Perspective

- [School Leader]

- I think The Bishops’ Religious Literacy Assessment is a waste of time especially at primary level. I am a teacher at a Catholic school and have a very strong faith. I send my children to Catholic schools. However, I really hate when my children’s experience during Religious Education is given a grade. I feel since formal assessment in this area it has turned many older children off learning about God.

- [Teacher]

- Until now, RE was all about exploring one’s feelings; ‘touchy feely’ emotions, driven teaching style. Now I think we are getting more balance coming in with knowledge about the history, knowledge about events, knowledge about Scripture, parts of the Mass and all that sort of language. The BRLA gives us a framework for teaching RE.

- [Participant 1]

- I think we really need greater focus on the person of Jesus and promoting love, compassion, joy and acceptance of all. Not sure if teaching the history of the Church and the Old Testament always complements this message.

- [Participant 2]

- I often feel that many of the learnt prayers are not relevant to our students and perhaps we are better off teaching students to converse with God in their own way that brings meaning to them.

- “We know that it [RE] is [a learning area] but often it is not, as more focus is on literacy and numeracy.”

- “Absolutely not. It [RE] is generally poorly timetabled and used as a filler for people’s timetables. REC’s and those who teach RE full time understand its value as the first learning area.”

- “No, it [RE] is not. RE is not treated as an equal with other core areas. Nor is it a priority for staff. RE is generally a ‘fill in subject’ for teachers who are down a line in their timetable. Untrained staff also being put into 11 and 12 classes…”

- [Teacher]

- Students don’t value doing The Bishops’ Religious Literacy Assessment and doing well in it because many parents and families don’t value Religion in schools …. Anything that has a Catholic logo or presence to it is considered second class or of a lower grade in education because it’s not valued at home.

- [Teacher]

- Unfortunately, the motivation and engagement from students was not fantastic. This is not the fault of the test, more so that their parents and their own attitude towards RE.

- [Principal]

- Our challenge is navigating ‘two worlds’, one foot in the Tradition and one in dealing with what reality in front of us is all about. That is, the issues around secularisation and wellbeing. These issues are increasing for students and parents.

- [Teacher]

- I believe in God and I have faith, but I don’t believe in the Catholic practices. In modern society, we don’t feel comfortable because the kids challenge you on every point or practice you are trying to teach.

4. Addressing the Research Problem

4.1. Considerations

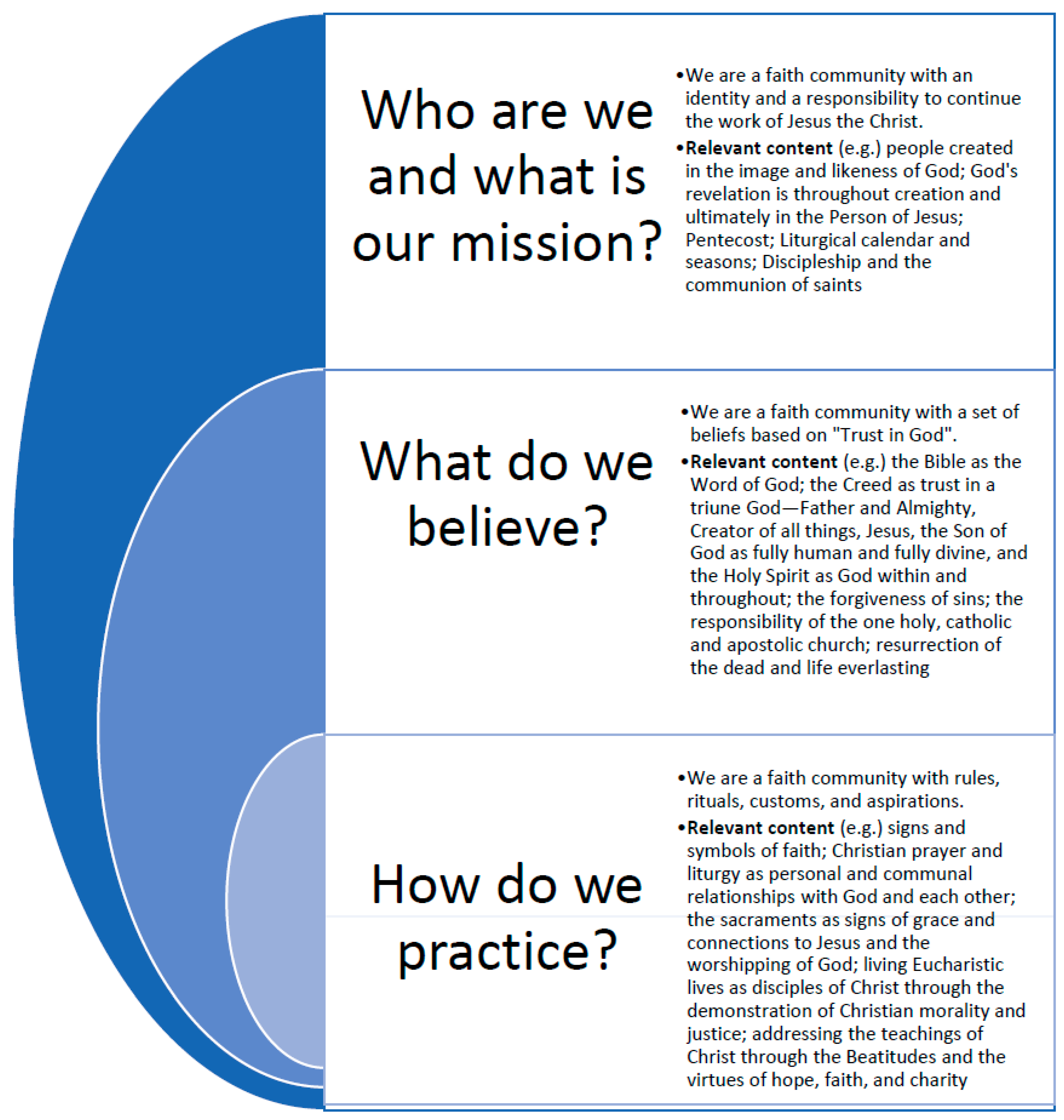

4.1.1. The Re-Assessment of Perceived Identity and Mission

4.1.2. The Re-Assessment of Faith Formation

4.1.3. The Re-Assessment of Family and Parish Engagements

4.1.4. The Re-Assessment of Planning Documents

4.2. The Application of the Approach

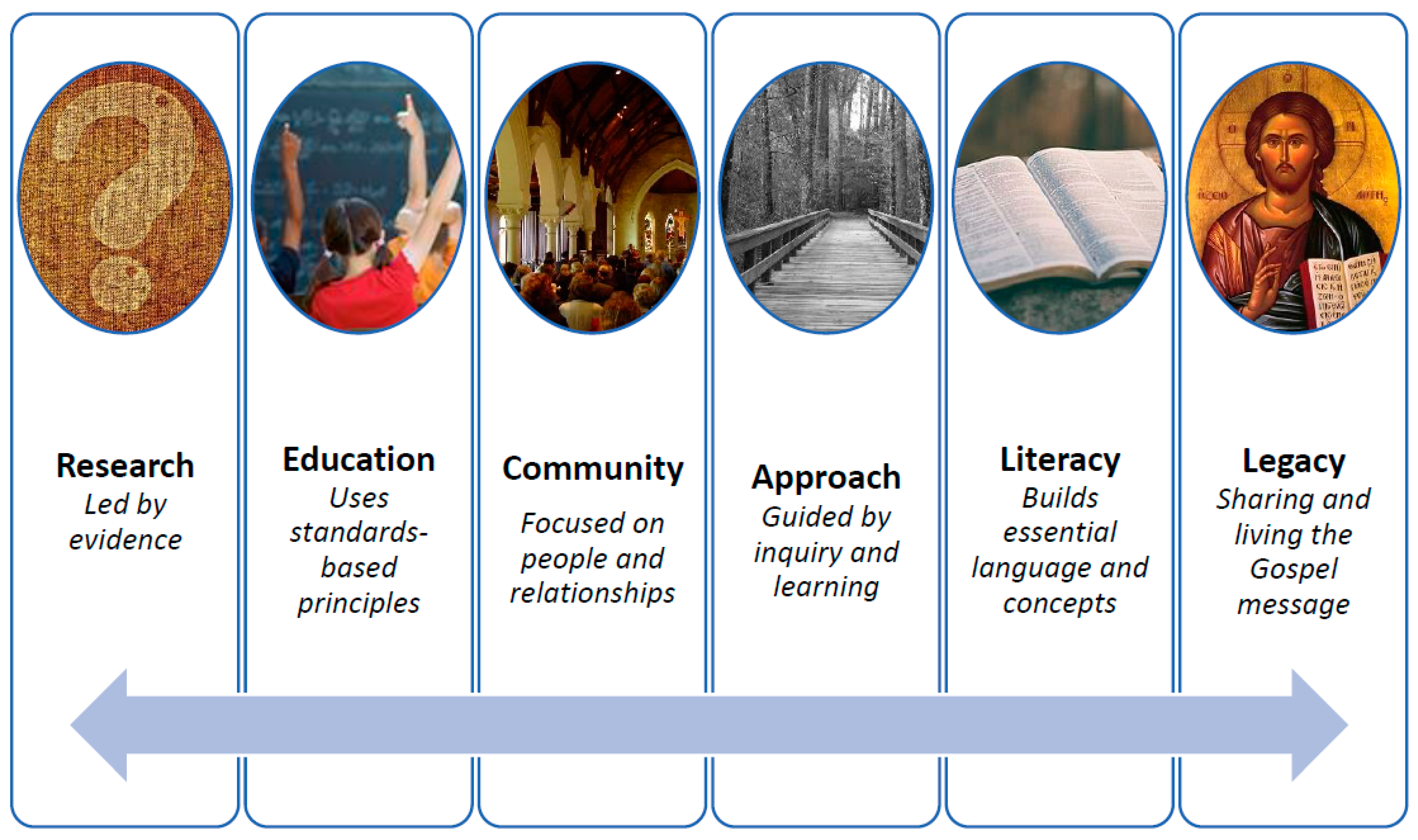

4.2.1. The Approach Is Research-Led

- How can religious educators be supported to engage with the identity and mission of the Catholic Church?

- How can religious educators be supported to develop a deeper understanding of the Catholic Church?

- How can religious educators be supported to engage with the beliefs of the Catholic Church?

- How can religious educators be supported to live and give witness to the beliefs and devotional practices of the Catholic Church?

- How can religious educators be supported to implement the Religious Education Curriculum and engage students with the identity and mission of the Catholic Church?

- How can engagement with the identity and mission of the Catholic Church be validly and reliably measured?

4.2.2. The Approach Adopts Educational Principles

4.2.3. The Approach Is Relational and Community-Minded

4.2.4. The Approach Is Guided by Three Overarching Questions

4.2.5. The Approach Builds Religious Literacy

4.2.6. The Approach Aims to Continue the Legacy

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2024. Religious Affiliation in Australia. 2021 Census. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/religious-affiliation-australia (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Australian Catholic Bishops’ Conference. 2022. About the National Themes for Discernment. Australia’s Plenary Council. Available online: https://plenarycouncil.catholic.org.au/themes/about-the-themes/ (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Australian Catholic Bishops’ Conference. 2024. National Centre for Pastoral Research—Social Profile of the Catholic Community in Australia Based on the 2021 Australian Census and the Australian Catholic Mass Attendance Report 2016. Available online: https://ncpr.catholic.org.au/ (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership Limited. 2022. Australian Teacher Performance and Development Framework. Available online: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/tools-resources/resource/australian-teacher-performance-and-development-framework (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Caldwell, Brian J. 2018. The Alignment Premium: Benchmarking Australia’s Student Achievement, Professional Autonomy and System Adaptability. Victoria: Australian Council for Educational Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Catholic Education Commission of Western Australia. 2009. Mandate: Catholic Education Commission of Western Australia 2009–2015. Available online: https://www.cewa.edu.au/publication/bishops-mandate-2009-2015/ (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Catholic Education Commission of Western Australia. 2019. Strategic Directions 2019–2023. Available online: https://www.cewa.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/2020.02_Strategic-Directions_Pages.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Catholic Education Western Australia. 2019. Secondary Religious Education Review Survey Links. Internal Prime Memo. Available online: https://cewaedu.sharepoint.com/sites/prime/CEWA%20Notice%20Board/Forms/Newest%20Modified%20First.aspx?id=%2Fsites%2Fprime%2FCEWA%20Notice%20Board%2FSecondary%20Religious%20Education%20Review%20Survey%20Links%2Epdf&parent=%2Fsites%2Fprime%2FCEWA%20Notice%20Board (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Catholic Education Western Australia. 2023a. Painted Dog Research—Faith Survey 2023. Internal Prime Memo. Available online: https://cewaedu.sharepoint.com/sites/prime/CEWA%20Notice%20Board/Memo%20Painted%20Dog%20Reserach%20Survey%20Link%20Faith%20Survey%202023.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Catholic Education Western Australia. 2023b. Professional Development Opportunities. Internal Prime Memo. Available online: https://cewaedu.sharepoint.com/sites/prime/CEWA%20Notice%20Board/All%20Principals%20PRIME%20Memo%20-%20Professional%20Development%20Opportunities.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Catholic Education Western Australia. 2023c. The Religious Education Assessment: School Assessment Coordinators’ User Guide. Perth: Perth Catholic Education Office: Religious Education Directorate. [Google Scholar]

- Congregation for Catholic Education. 1977. The Catholic School. Homebush: St Pauls Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Congregation for Catholic Education. 1982. Lay Catholics in Schools: Witness to Faith. Homebush: St Pauls Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Congregation for Catholic Education. 1988. The Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School. Homebush: St Pauls Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Congregation for Catholic Education. 1997. The Catholic School on the Threshold of the Third Millennium. The Holy See. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/ccatheduc/documents/rc_con_ccatheduc_doc_27041998_school2000_en.html (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Congregation for Catholic Education. 2022. The Identity of the Catholic School for a Culture of Dialogue. The Holy See. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/ccatheduc/documents/rc_con_ccatheduc_doc_20220125_istruzione-identita-scuola-cattolica_en.html (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Convery, Ronnie, Leonardo Franchi, and Jack Valero, eds. 2021. Reclaiming the Piazza III: Communicating Catholic Culture. Leominster: Gracewing. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, Sandra. 2017. Interpreting ‘between privacies’: Religious education as a conversational activity. In Does Religious Education Matter? 1st ed. Edited by M. Shanahan. New York: Routledge, pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, Sandra. 2019. The religious education of the religion teacher in Catholic schools. In Global Perspectives on Catholic Religious Education in Schools, Volume II: Learning and Leading in a Pluralist World. Edited by M. T. Buchanan and A. Gellel. Singapore: Springer, pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- D’Orsa, Jim, and Therese D’Orsa. 2013. Catholic Curriculum: A Mission to the Heart of Young People. Victoria: Vaughan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- D’Orsa, Jim, and Therese D’Orsa. 2020. Pedagogy and the Catholic Educator: Nurturing Hearts, Transforming Possibilities. Victoria: Vaughan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Robert, and Leonardo Franchi. 2021. Catholic Education and the Idea of Curriculum. Journal of Catholic Education 24: 104–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. 2018. Through Growth to Achievement: Report of the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools; Canberra: Australian Government. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/quality-schools-package/resources/through-growth-achievement-report-review-achieve-educational-excellence-australian-schools (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Franchi, Leonardo, and Richard Rymarz. 2022. Formation of Teachers for Catholic Schools: Challenges and Opportunities in a New Era, 1st ed. Singapore: Springer, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Francis. 2013. Apostolic Exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium. The Holy See. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_exhortations/documents/papa-francesco_esortazione-ap_20131124_evangelii-gaudium.html (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Francis. 2015. Meeting with the Participants in the Fifth Convention of the Italian Church, Address of the Holy Father. c. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2015/november/documents/papa-francesco_20151110_firenze-convegno-chiesa-italiana.html (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Francis. 2018. Apostolic Exhortation, Gaudete et Exsultate of the Holy Father Francis on a Call to Holiness in Today’s World. The Holy See. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_exhortations/documents/papa-francesco_esortazione-ap_20180319_gaudete-et-exsultate.html (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Fullan, Michael, and Joanne Quinn. 2016. Coherence: The Right Drivers in Action for Schools, Districts, and Systems. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press. Toronto: Ontario Principals’ Council. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, Chris. 2009. What is best and most special about teaching religious education? Journal of Religious Education 57: 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, Chris. 2010. The role of experiential content knowledge in the formation of beginning RE teachers. Journal of Religious Education 58: 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, Chris, Debra Sayce, and Diana Alteri. 2017. Curriculum overview “The truth will set you free”: Religious education in Western Australia. In Religious Education in Australian Catholic Schools, Exploring the Landscape. Edited by R. Rymarz and A. Belmonte. Mulgrave: Vaughan Publishing, pp. 264–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie, John. 2023. Visible Learning, the Sequel: A Synthesis of Over 2100 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Holohan, Gerard J. 1999. Australian Religious Education: Facing the Challenge. Canberra: National Catholic Education Commission. [Google Scholar]

- John Paul II. 2003. Encyclical Letter, Ecclesia de Eucharistia, The Holy See. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_20030417_eccl-de-euch.html (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Jones, Alexander. 1974. The Jerusalem Bible. London: Darton, Longman and Todd. [Google Scholar]

- Masters, Geoff. 2018. A Commitment to Growth: Essays on Education. Camberwell: Australian Council for Educational Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, Stephen J. 2021. A Catholic understanding of education. In Reclaiming the Piazza III: Communicating Catholic Culture. Edited by R. Convery, L. Franchi and J. Valero. Leominster: Gracewing. [Google Scholar]

- Montessori, Maria. 1949. Montessori: On Religious Education. The Montessori-Pierson Company CV 1949 (Reprinted by permission, 2020). Lake Ariel: Hillside Education. [Google Scholar]

- National Catholic Education Commission. 2018. Framing Paper: Religious Education in Australian Catholic Schools. Available online: https://www.ncec.catholic.edu.au/images/NCEC_Framing_Paper_Religious_Education.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- National Catholic Education Commission. 2022. A Framework for Student Faith Formation in Catholic Schools. Available online: https://ncec.catholic.edu.au/resource-centre/framework-for-student-faith-formation-in-catholic-schools/ (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Nelson, James M. 2010. Psychology, Religion and Spirituality. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, Gerard. 2018. Educating in Christ: A Practical Handbook for Developing the Catholic Faith from Childhood to Adolescence, for Parents, Teachers, Catechists and School Administrators. Brooklyn: Angelico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, Craig, ed. 2016. The Mission of the Church: Five Views in Conversation. Grand Rapids: Baker Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Paul VI. 1975. Apostolic Exhortation, Evangelii Nuntiandi. The Holy See. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/paul-vi/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_p-vi_exh_19751208_evangelii-nuntiandi.html (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Petersen, Jacinta E., and Antonella Poncini. 2020. Investigating Teaching and Assessment Practices in Religious Education: Perceptions of Teachers and Leaders in Catholic Schools in Western Australia. Fremantle: The University of Notre Dame Australia, Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Pollefeyt, Didier. 2020. Hermeneutical learning in religious education. Journal of Religious Education 68: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poncini, Antonella. 2018. Perceptions of Large-Scale, Standardised Testing in Religious Education: How do Religious Educators Perceive the Bishops’ Religious Literacy Assessment? Doctoral thesis, The University of Notre Dame Australia, Fremantle, Australia. Available online: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/210 (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Poncini, Antonella. 2021. Research insights: Perceived differences about teaching and assessment practices in religious education. Journal of Religious Education 69: 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poncini, Antonella. 2023. Standards Setting in Religious Education: Addressing the Quality of Teaching and Assessment Practices. Religions 14: 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratzinger, Jonathan. 1970. Faith and the Future. Pope Benedict XVI. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Christine, and Chris Hackett. 2022. Spiritual and Religious Capabilities: A Possibility for How Early Childhood Catholic Religious Educators Can Address the Spirituality Needs of Children. In The Routledge International Handbook of the Place of Religion in Early Childhood Education and Care, 1st ed. Edited by A. Kuusisto. London: Routledge, pp. 444–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, Louis. 2016. Engaging the Thought of Bernard Lonergan. London: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rymarz, Richard, and Anthony Cleary. 2018. Examining some aspects of the worldview of students in Australian Catholic schools: Some implications for religious education. British Journal of Religious Education 40: 327–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymarz, Richard, and Leonardo Franchi. 2019. Catholic Teacher Preparation: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Preparing for Mission. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymarz, Richard, and Paul Sharkey, eds. 2019. Moving from Theory to Practice, Religious Educators in the Classroom. Mulgrave: Vaughan and Garratt Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rymarz, Richard, Kathleen Engebretson, and Brendan Hyde. 2021. Teaching Religious Education in Catholic Schools, Embracing a New Era. Mulgrave: Garratt Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- School Curriculum and Standards Authority. 2024. The Authority. Available online: https://www.scsa.wa.edu.au/about-us/about-scsa (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Scott, Kieran. 2015. Problem or paradox: Teaching the Catholic religion in Catholic schools. In Global Perspectives on Catholic Religious Education in Schools. Edited by M. T. Buchanan and A. Gellel. Melbourne: Springer, pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Kieran. 2019. The teacher of religion: Choosing between professions in Catholic schools. In Global Perspectives on Catholic Religious Education in Schools, Volume II: Learning and Leading in a Pluralist World. Edited by M. T. Buchanan and A. Gellel. Singapore: Springer, pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart-Buttle, Ros. 2017. Does religious education matter? What do teachers say? In Does Religious Education Matter? 1st ed. Edited by Mary Shanahan. London: Routledge, pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, John. 2017. A space like no other. In Does Religious Education Matter? 1st ed. Edited by Mary Shanahan. London: Routledge, pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, John. 2018. Diversity and differentiation in Catholic education. In Researching Catholic Education, Contemporary Perspectives. Edited by Sean Whittle. Singapore: Springer, pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sultmann, William, and David Hall. 2022. Beyond the school gates. Journal of Religious Education 70: 229–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, Horace Standish, ed. 1982. Pragmatism, the Classic Writings. Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- The Holy See. 1993. Catechism of the Catholic Church. Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/_INDEX.HTM (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- The Holy See. 2020. Directory for Catechesis. Pontifical Council for Promoting New Evangelisation. Strathfield: St Pauls Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Timperley, Helen, Fiona Ell, and Deidre Le Fevre. 2020. Leading Professional Learning, Practical Strategies for Impact in Schools. Victoria: ACER Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vatican Council II. 1965a. Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, Dei Verbum. The Holy See. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19651118_dei-verbum_en.html (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Vatican Council II. 1965b. Declaration on Christian education, Gravissimum Educationis. The Holy See. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_decl_19651028_gravissimum-educationis_en.html (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Vatican Council II. 1965c. Decree Ad Gentes on the Mission Activity of the Church. The Holy See. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_decree_19651207_ad-gentes_en.html (accessed on 1 April 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poncini, A. Formation Fit for Purpose: Empowering Religious Educators Working in Catholic Schools. Religions 2024, 15, 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060665

Poncini A. Formation Fit for Purpose: Empowering Religious Educators Working in Catholic Schools. Religions. 2024; 15(6):665. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060665

Chicago/Turabian StylePoncini, Antonella. 2024. "Formation Fit for Purpose: Empowering Religious Educators Working in Catholic Schools" Religions 15, no. 6: 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060665

APA StylePoncini, A. (2024). Formation Fit for Purpose: Empowering Religious Educators Working in Catholic Schools. Religions, 15(6), 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060665