The Architectural Christian Spolia in Early Medieval Iberia: Reflections between Material Reuse and Cultural Appropriation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. From Reuse to Appropriation

3. Case Studies

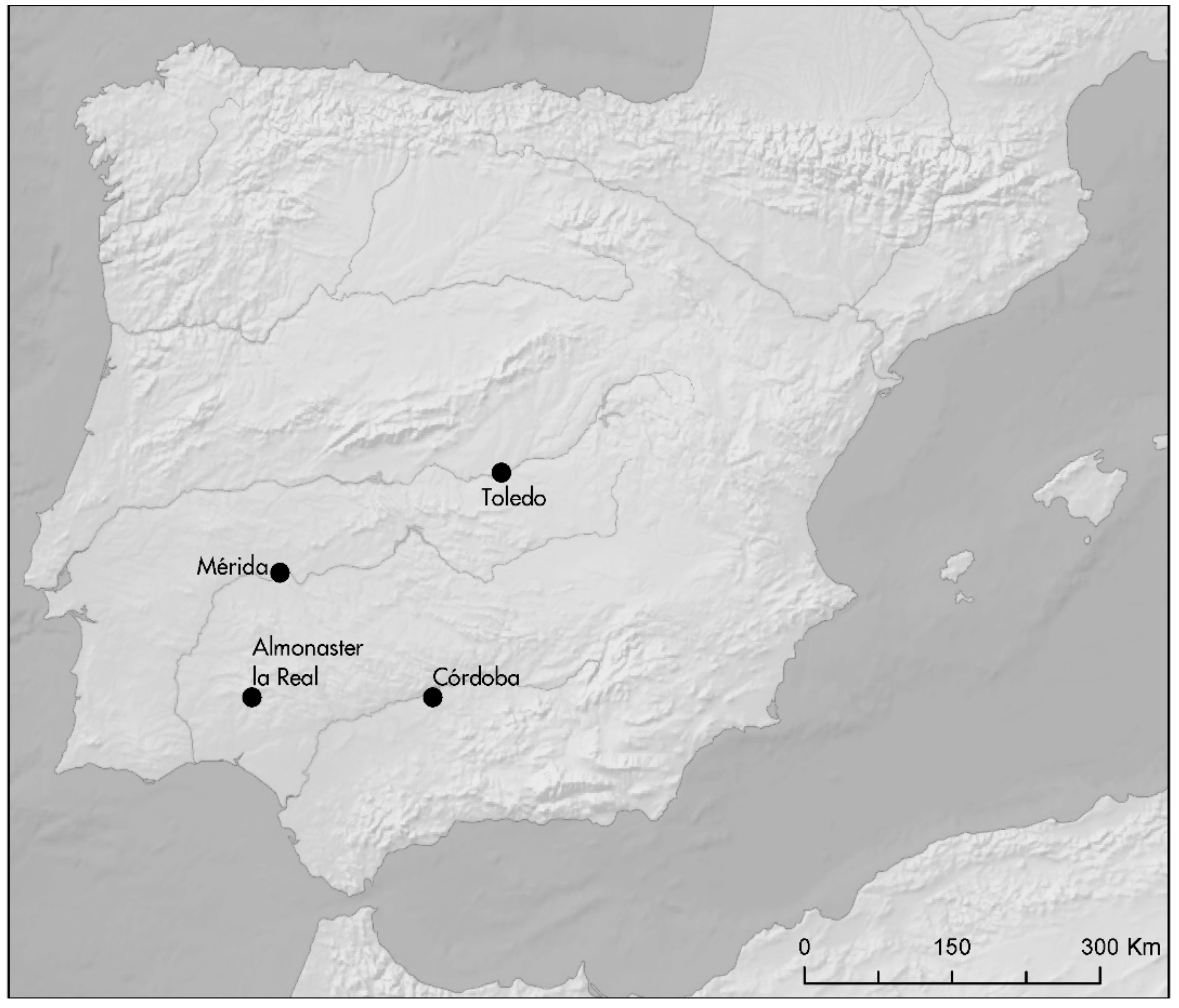

3.1. The Citadel of Mérida (Badajoz)

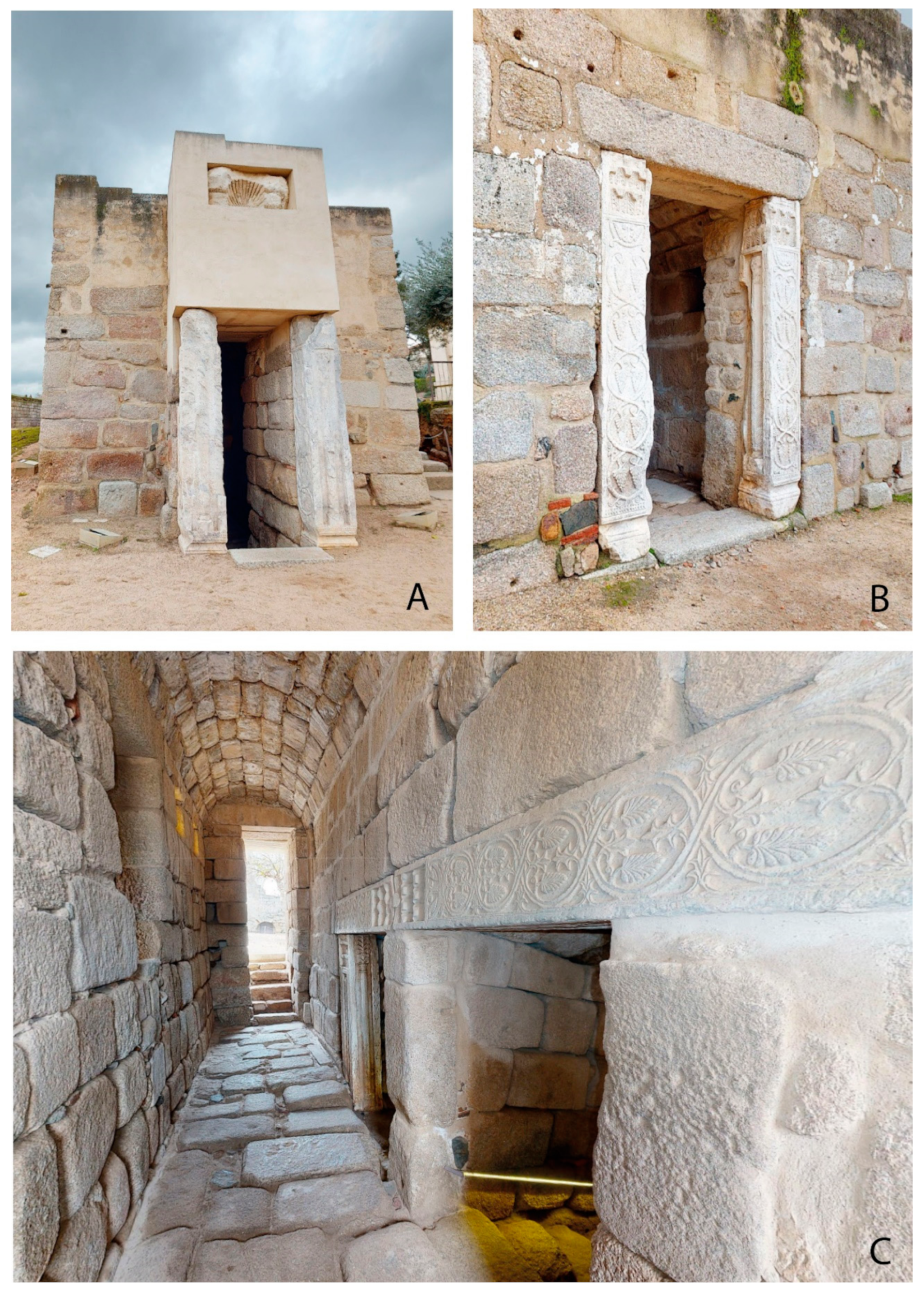

3.2. The Almonaster la Real Mosque (Huelva)

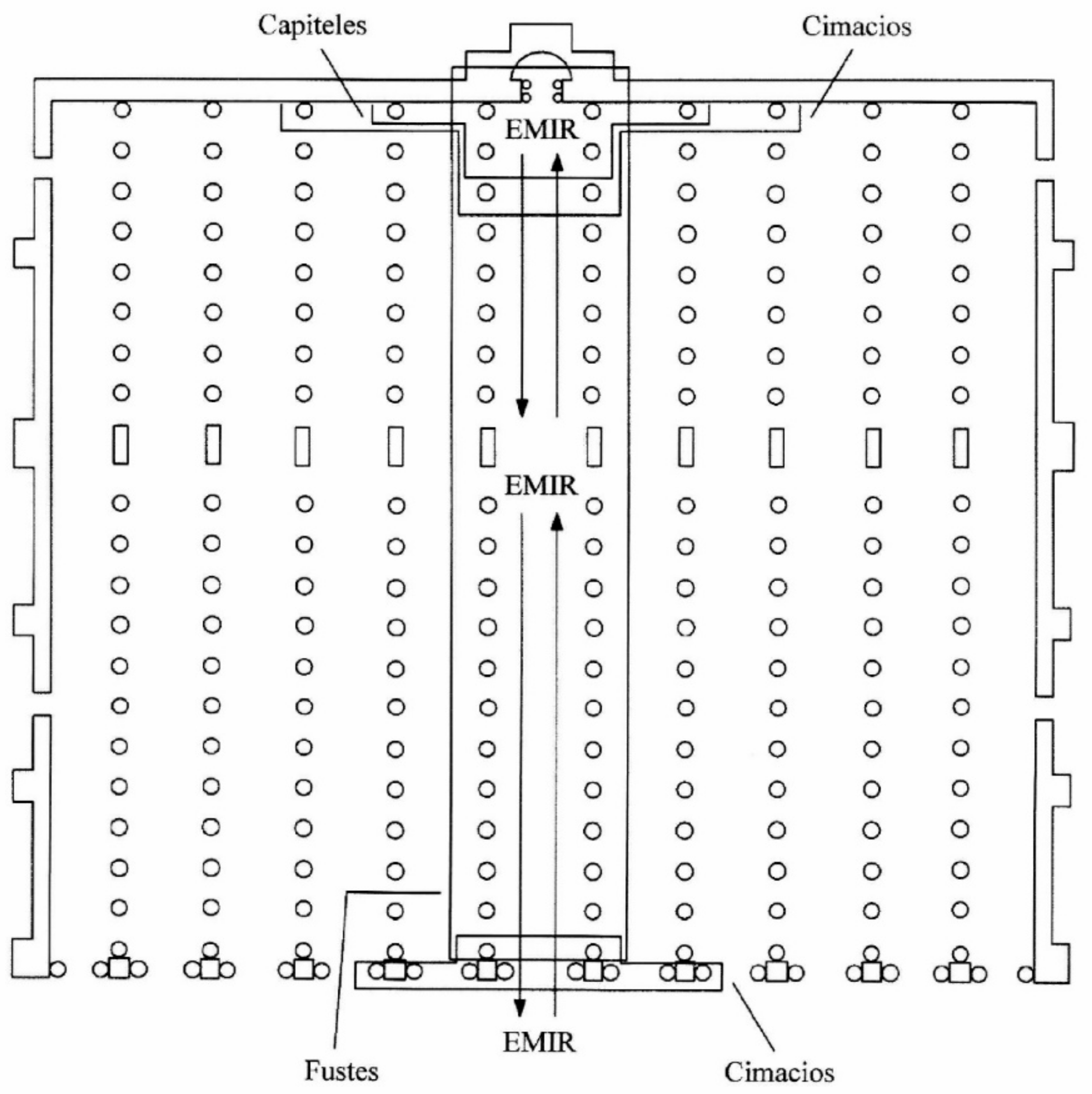

3.3. The Aljama Mosque of Córdoba

3.4. The Different Uses of Late Ancient and Visigothic Spolia in the City of Toledo

3.4.1. Sculptural Remains from the Visigothic Period in Mosques

3.4.2. The Use of Spolia from the Visigothic Period in Toledo after the Castilian Conquest (11th–12th Centuries)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | We would like to express our gratitude to the reviewers of this article for their thoughtful comments and suggestions aimed at improving this manuscript. |

| 2 | Beyond the spolia from the Great Mosque of Córdoba, the city features various examples of architectural material reuse from the Roman, Late Antique, and Visigothic periods. Relevant to the topic of this study, it is worth noting the reuse of small Visigothic monolithic columns in the decorative frieze of the southwest facade of the San Juan minaret, built during the Emirate period (González Gutiérrez 2022, pp. 92–93). |

| 3 | It has been proposed that some of the columns and capitals in the central nave of this mosque are spolia from the Visigothic period (Calvo Capilla 2014, pp. 424, 672). |

References

Original Sources

Crónica mozárabe de 754 (Ed. 1980), edición crítica y traducción de Jose Eduardo López Pereira. Zaragoza: Anubar.Crónica abreviada de Don Juan Manuel (Ed. 1983), edición de José Manuel Blecua: Obras Completas II. El conde Lucanor. Crónica abreviada. Madrid: Gredos.Secondary Sources

- Arce Sainz, Fernando. 2015. La supuesta basílica de San Vicente en Córdoba: De mito histórico a obstinación historiográfica. Al-Qanṭara 36: 11–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce Sainz, Fernando. 2020. La reutilización de materiales cristianos en la alcazaba de Mérida ¿derrota y humillación del cristianismo local? In Exemplum et Spolia: La reutilización arquitectónica en la transformación del paisaje urbano de las ciudades históricas. Edited by Pedro Mateos Cruz and Carlos Jesús Morán Sánchez. MYTRA, Monografías y Trabajos de Arqueología, 7. Mérida: Instituto de Arqueología de Mérida, vol. 2, pp. 663–68. [Google Scholar]

- Azuar, Rafael. 2005. Las técnicas constructivas en la formación de al-Andalus. Arqueología de la Arquitectura 4: 149–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceló, Carmen. 2004. Las inscripciones omeyas de la alcazaba de Mérida. Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 11: 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, Rafael, Jesús Carrobles, and Jorge Morín, eds. 2007. Regia Sedes Toletana II. El Toledo visigodo a través de su escultura monumental. Toledo: Diputación de Toledo, Real Fundación de Toledo. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, Rafael, Jesús Carrobles, and Jorge Morín. 2009. Toledo visigodo y su memoria a través de los restos escultóricos. In Spolien im umkreis der macht/Spolia en el entorno del poder. Akten der tagung in Toledo vom 21. bis 22. september 2006/Actas del coloquio en Toledo del 21 al 22 de septiembre 2006. Edited by Thomas y Schattner and Fernando Valdés Fernández. Toledo: Diputación Provincial de Toledo, pp. 171–97. [Google Scholar]

- Brenk, Beat. 1987. Spolia from Constantine to Charlemangne: Aesthetics versus ideology. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 41: 103–9, Studies on Art and Archaeology in Honor of Ernst Kitzinger on His Seventy-Fifth Birthday. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenacasa Pérez, Carles. 1997. La decadencia y cristianización de los templos paganos a lo largo de la antigüedad tardía (313–423). Polis: Revista de ideas y formas políticas de la Antigüedad 9: 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo Capilla, Susana. 2014. Las mezquitas de al-Andalus. Almería: Fundación Ibn Tufayl. [Google Scholar]

- Cressier, Patrice. 2001. El acarreo de obras antiguas en la arquitectura islámica de primera época. Cuadernos Emeritenses 17: 309–34. [Google Scholar]

- Daza Pardo, Enrique. 2024. Fortificaciones y estructuras defensivas en el al-Andalus omeya (ss. VII–XI). Razón, materia y territorio. In Al-Andalus y la guerra. Coordinate with Javier Albarrán. Serie Guerra Medieval Ibérica 5; Madrid: La Ergástula, pp. 275–300. [Google Scholar]

- De Juan García, Antonio, and Mercedes De Paz Escribano. 1996. Iglesia de Santa Justa y Rufina. In Toledo: Arqueología en la ciudad. Toledo: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Junta de Castilla—La Mancha, pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- de los Ríos y Serrano, José Amador. 1845. Toledo Pintoresco o Descripción de sus más Célebres Monumentos. Madrid: Ignacio Boix. [Google Scholar]

- Elices Ocón, Jorge. 2021. La reutilización de antigüedades en al-Ándalus: ¿recurso o discurso? Archivo Español de Arqueología 94: e06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijoo Martínez, Santiago. 2001. El aljibe de la Alcazaba de Mérida. 1ª campaña de intervención arqueológica en la zona Norte y Oeste del aljibe. Mérida, Excavaciones Arqueológicas 5: 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- Feijoo Martínez, Santiago, and Miguel Alba Calzado. 2005. El sentido de la Alcazaba emiral de Mérida: Su aljibe, mezquita y torres de señales. Mérida, Excavaciones Arqueológicas 8: 565–86. [Google Scholar]

- Feijoo Martínez, Santiago, and Miguel Alba Calzado. 2006. Nueva lectura arqueológica del Aljibe y la Alcazaba de Mérida. In Al-Ândalus: Espaço de mudança, balanço de 25 anos de historia: Seminário internacional, Mértola, 16, 17 e 18 de maio de 2005, homenagem a Juan Zozaya Stabel-Hansen. Edited by Susana Gómez-Martínez. Mértola: Campo Arqueológico de Mértola, pp. 161–70. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, Bruno. 2020. Historiografía islámica sobre reutilización de elementos arquitectónicos en la Mérida andalusí. In Exemplum et Spolia: La reutilización arquitectónica en la transformación del paisaje urbano de las ciudades históricas. Edited by Pedro Mateos Cruz and Carlos Jesús Morán Sánchez. MYTRA, Monografías y Trabajos de Arqueología, 7. Mérida: Instituto de Arqueología de Mérida, vol. 1, pp. 653–62. [Google Scholar]

- Franco Moreno, Bruno, Juana Márquez Pérez, and Pedro Mateos Cruz. 2020. La alcazaba de Mérida. La reutilización de materiales romanos y de época visigoda. In Exemplum et Spolia: La Reutilización Arquitectónica en la Transformación del Paisaje urbano de las Ciudades Históricas. Edited by Pedro Mateos Cruz and Carlos J. Morán Sánchez. MYTRA, Monografías y Trabajos de Arqueología, 7. Mérida: Instituto de Arqueología de Mérida, vol. 1, pp. 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Sánchez, Francisco. 2015. Almonastires y rábitas: Espiritualidad islámica individual y defensa colectiva de la comunidad. Espiritualidad y geopolítica en los orígenes de Almonaster la Real. In Culturas de al-Andalus. Edited by Fátima Roldán Castro. Colección Estudios Árabo-Islámicos de Almonaster la Real, n.º 302. Sevilla: Editorial Universidad de Sevilla, pp. 39–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Gutierrez, Carmen. 2022. Spolia and Umayyad Mosques: Examples and Meanings in Córdoba and Madinat al-Zahrāʾ. Journal of Islamic Archaeology 9: 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo Benito, Ricardo. 2006. Alminares y torres. Herencia y presencia del Toledo medieval. In Alminares y torres. Herencia y Presencia del Toledo Medieval. Coordinate with Soledad Sánchez-Chiquito de La Rosa. Los Monográficos del Consorcio, 4. Toledo: Consorcio de la Ciudad de Toledo, pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo Benito, Ricardo. 2010. Las mozárabes de Toledo y sus iglesias. In Homenaje al profesor Eloy Benito Ruano. Murcia: Sociedad Española de Estudios Medievales/Universidad de Murcia/Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, vol. 2, pp. 401–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Martín, Alfonso. 1975. La mezquita de Almonaster. Huelva: Instituto de Estudios Onubenses, Diputación Provincial de Huelva. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Martín, Alfonso. 2005. Mezquitas, castillos e iglesias: Notas sobre la arquitectura del siglo XIII en la Sierra de Huelva. In La banda gallega: Conquista y fortificación de un espacio de frontera (siglos XIII–XVIII)/I Curso de Historia y Arqueología Medieval. Coordinate with José Aurelio Pérez Macías and Juan Luis Carriazo Rubio. Santa Olalla del Cala: Universidad de Huelva, Servicio de Publicaciones, pp. 121–201. [Google Scholar]

- León Muñoz, Alberto, and Raimundo Ortiz Urbano. 2022. El complejo episcopal de Córdoba: Nuevos datos arqueológicos. In Cambio de era. Córdoba y el mediterráneo cristiano. Edited by Alexandra Chavarría Arnau. Catálogo de la exposición (Córdoba, 16.12.2022–15.03.2023). Córdoba: Ayuntamiento de Córdoba, pp. 169–72. [Google Scholar]

- López Quiroga, Jorge, and Artemio Manuel Martínez Tejera. 2006. El destino de los templos paganos en Hispania durante la Antigüedad Tardía. Archivo Español de Arqueología 79: 125–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, Pedro. 1995. Identificación del xenodochium fundado por Masona en Mérida. In Actes IV Reunio d’Arqueologia Cristiana Hispanica (Lisboa 28–30 setembro, 1–2 outubro 1992). Barcelona: Universidad de Barcelona, Institut d’Estudis Catalans, pp. 309–16. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Torrero, Rodrigo. 2021. Spolia y legitimación. El problema epigráfico y la datación de las iglesias hispanovisigodas toledanas. Antesteria: Debates de Historia Antigua 9–10: 269–94. [Google Scholar]

- Murga, José Luis. 1979. El expolio y deterioro de los edificios públicos en la legislación post-constantiniana. In Atti III convegno internazionale. Accademia Romanistica Costantiniana (Perugia, 1977). Perugia: Librería Universitaria, Universitá degli Studi di Perugia, Facoltà di Giurisprudenza, pp. 239–63. [Google Scholar]

- Passini, Jean. 2002. La antigua iglesia de San Ginés en Toledo. Tulaytula: Revista de la Asociación de Amigos del Toledo Islámico 10: 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pavón Maldonado, Basilio. 1988. Arte toledano: Islámico y mudejar. Madrid: Instituto Hispano-Árabe de Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Pavón Maldonado, Basilio. 1990. Arte islámico y mudéjar en Toledo: La supuesta mezquita de las Santas Justa y Rufina y la Puerta del Sol. Al-Qanṭara 11: 509–26. [Google Scholar]

- Peña Jurado, Antonio. 2009. Análisis del reaprovechamiento de material en la mezquita Aljama de Córdoba. In Spolien im umkreis der macht/Spolia en el entorno del poder. Akten der tagung in Toledo vom 21. bis 22. september 2006/Actas del coloquio en Toledo del 21 al 22 de septiembre 2006. Edited by Thomas Schattner and Fernando Valdés Fernández. Toledo: Diputación Provincial de Toledo, pp. 247–72. [Google Scholar]

- Peña Jurado, Antonio. 2010. Estudio de la decoración arquitectónica romana y análisis del reaprovechamiento de material en la Mezquita Aljama de Córdoba. Córdoba: Universidad de Córdoba. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez de Arellano, Rafael. 1921. Las parroquias de Toledo. Nuevos datos referentes a estos Templos sacados de sus archivos. Facsímil IPIET de 1997. Toledo: Talleres Tipográficos de Sebastián Rodríguez. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Estévez, Juan Clemente. 1998. El Alminar de Isbiliya. La Giralda en sus orígenes (1184–1198). Sevilla: Ayuntamiento de Sevilla. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas Rodríguez-Malo, Juan Manuel. 2006. El alminar en Tulaytula. In Alminares y torres. Herencia y presencia del Toledo medieval. Coordinate with Soledad Sánchez-Chiquito de La Rosa. Los Monográficos del Consorcio, 4. Toledo: Consorcio de la Ciudad de Toledo, pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Morote Tramblin, Laura. 2018. Mezquitas Toledanas: Origen, Evolución, Implantación. Trabajo de Fin de Grado: Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. [Google Scholar]

- Rütenik, Tobias. 2009. Transformación de mezquitas a iglesias en Toledo desde la perspectiva de la arqueología arquitectónica. Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa 20: 291–316. [Google Scholar]

- Schlunk, Helmut. 1971. La pilastra de San Salvador de Toledo. Anales toledanos 3: 235–54. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Balbás, Leopoldo. 1957. Arte califal. In Historia de España, dirigida por Ramón Menéndez Pidal. Tomo V. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiolis, Vasilis. 2009. La mezquita de la Cueva de Hércules y la iglesia de San Ginés. In Mezquitas en Toledo, a la luz de los nuevos Descubrimientos. Coordinate with Soledad Sánchez-Chiquito de La Rosa. Los Monográficos del Consorcio, 5. Toledo: Consorcio de la Ciudad de Toledo, pp. 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Utrero Aguado, María de los Ángeles, and Isaac Sastre de Diego. 2012. Reutilizando materiales en las construcciones de los siglos VII–X. ¿Una posibilidad o una necesidad? Anales de Historia del Arte 22: 309–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés Fernández, Fernando. 1995. El aljibe de la Alcazaba de Mérida y la política omeya en el Occidente de al-Andalus. Extremadura Arqueológica V: 279–99. [Google Scholar]

- Vedovetto, Paolo. 2022. Escultura litúrgica y decorativa tardoantigua en Córdoba. In Cambio de era. Córdoba y el mediterráneo cristiano. Edited by Alexandra Chavarría Arnau. Catálogo de la exposición (Córdoba, 16.12.2022–15.03.2023). Córdoba: Ayuntamiento de Córdoba, pp. 117–24. [Google Scholar]

| Chronicle of 754 (Latin) | Chronicle of 754 (Trans. Ed. 1980) | Crónica Abreviada (Ed. 1983) |

|---|---|---|

| Qui iam in supra fatam eram anni tertii sceptra regia meditans ciuitatem Toleti mire et eleganti labore renobat, quem et opere sculptprio uersiuicando pertitulans hoc in portarum epigrammata stilo ferreo in nitida lucidaque marmora patrat: “Erexit factore Deo rex inclitus urbem Uuamba sue celebrem protendens gentis honorem” In memoriis quoque martirum, quas super easdem portarum turriculas titulauit, hec similiter exarauit: “Uos, sancti domini, quorum hic presentia fulget. Hanc urbem et plebem solito saluate fabore”. | During the aforementioned era, in his third year of exercising royal power, Wamba undertook the admirable and meticulous task of restoring the city of Toledo. As part of this endeavor, he crafted a dedication in verse which he inscribed on its doors: “With the help of God, Wamba, a distinguished king, restored this city, Spreading the illustrious glory of his people.” Likewise, he composed the following inscription in honor of the martyrs, which he placed on the same door turrets where the previous dedication had been inscribed: “You saints of the Lord, whose presence shines here, In this city and among this people, Protect them with your customary guardianship.” | En el LXXIII capitulo, que fue En el III anno de su regnado, dize que entro el rey Banba en Toledo mucho onrrada mente. E fizo labrar los muros dela cerca de muy buena obra e pusso estos versos en vnos marmoles blancos encima dela puerta dela villa: [Erexit factore Deo rex inclitus urbem Vamba, sue celebrem protendens gentis honorem.] Que quier dezir: «El nonbre del rey Banba alço e mejoro la cibdat de Toledo con ayuda de Dios e por acrecentar la onrra e la nonbradia de su gente» Otrossi dize que fizo escrevir estos versos enlas torres delas iglesias: [Vos Domini sancti quorum hinc presencia fulget, hanc urbem et plebem solito saluate fauore.] Que quier dezir: «Vos, santos de nuestro Sennor, que ssodes onrrados en este logar, saluat e onrrat este pueblo e esta cibdat por el poder que avedes.» |

| Functional reuse | It would be one in which only material values prevail as simple masonry resource. |

| Aesthetic reuse | Reuse of sculptural elements without purposes of appropriation or political significance, stressing just a decorative sense. |

| Ideological reuse | Continuative: Continuity of a sacred place. No traces of Christian symbols are detected. |

| Apotropaic: Transfer of pieces and exhibition with a prophylactic sense. | |

| Appropriative: Transfer of legitimacy or sacredness. Occasionally, it displays the destruction of previous sacred motifs. | |

| “Destructive/disruptive”: The intentional use of large pieces imbued with Christian religious meaning, always deliberately erased, serves to ideologically destroy their significance. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daza-Pardo, E.; Catalán-Ramos, R. The Architectural Christian Spolia in Early Medieval Iberia: Reflections between Material Reuse and Cultural Appropriation. Religions 2024, 15, 663. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060663

Daza-Pardo E, Catalán-Ramos R. The Architectural Christian Spolia in Early Medieval Iberia: Reflections between Material Reuse and Cultural Appropriation. Religions. 2024; 15(6):663. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060663

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaza-Pardo, Enrique, and Raúl Catalán-Ramos. 2024. "The Architectural Christian Spolia in Early Medieval Iberia: Reflections between Material Reuse and Cultural Appropriation" Religions 15, no. 6: 663. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060663

APA StyleDaza-Pardo, E., & Catalán-Ramos, R. (2024). The Architectural Christian Spolia in Early Medieval Iberia: Reflections between Material Reuse and Cultural Appropriation. Religions, 15(6), 663. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060663