Historical Traceability, Diverse Development, and Spatial Construction of Religious Culture in Macau

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Problem Statement and Research Method

2. Historical Origin: The Formation and Spread of Religious Belief in Macau

2.1. Before Portuguese Colonization: Religious Pluralism of Origin and Restricted Syncretism

2.2. Period of Portuguese Colonial Influence: Localization and Cultural Adaptation of Catholicism

2.3. Period of Integration and Interaction between Eastern and Western Religions: The Complexity of Cultural Symbiosis and Identity

2.4. Modern Transformation and Protection Period: The Double-Edged Sword of Cultural Heritage and Tourism

3. Diversified Development in Humanistic Landscapes: Churches, Temples, and Monasteries

3.1. Churches in Macau

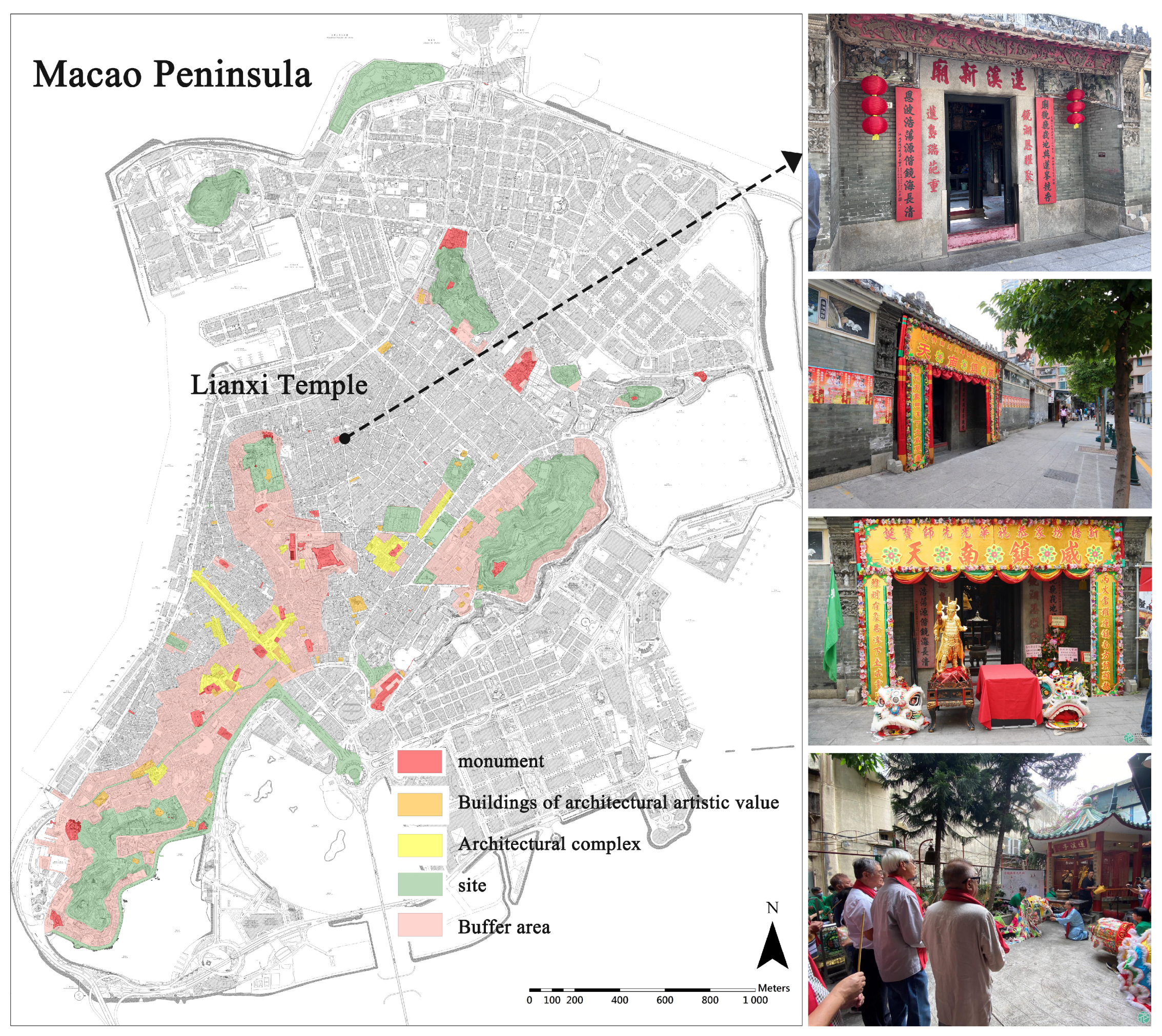

3.2. Temples in Macau

3.3. Monasteries in Macau

4. Spatial Construction: Religious Culture Becomes the Link of Social Development

4.1. Cultural Capital Accumulation and Spatial Symbolization

4.2. Social Integration and Spatial Cohesion

4.3. Space Production and Consumption Guidance

5. Conclusions

- The emergence and transformation of religious culture in Macau represents a vibrant historical-geographical process, serving as a compelling instance of multicultural intersection and amalgamation. Macau’s pivotal location along the East–West maritime trade routes enabled it to historically embrace merchants and missionaries from Europe, Southeast Asia, and various corners of the globe, thereby facilitating the dissemination and entrenchment of diverse religions. Notably, between the 16th and 19th centuries, Catholicism gained a foothold in Macau through the Portuguese, laying a firm foundation in the region. Concurrently, traditional Chinese religions, including Buddhism and Taoism, thrived locally, alongside later arrivals such as Islam and Protestantism. It is worth mentioning that Western missionaries not only introduced Catholicism to Macau but also actively engaged in profound dialogues and integrations with Chinese Confucian ethics. This fostered cross-cultural exchanges and religious adaptations, giving rise to a Sino-Western religious architectural aesthetic and a myriad of religious festivals. These elements facilitated mutual influence and learning amongst diverse religions, collectively shaping Macau’s rich and distinctive religious landscape. This landscape serves as a reflection of religious cultural exchange, collision, and dissemination in the era of globalization. In this process, while cultural exchange and integration positively contribute to promoting the coexistence of diversity, they also serve as a reminder to exercise caution regarding the potential risks of cultural homogenization and inequality that may arise. It is imperative to safeguard the coexistence and flourishing of diverse cultural characteristics founded on mutual respect, preventing them from being obscured or marginalized.

- The spatial arrangement of various religious sites in Macau mirrors the cultural heterogeneity of the city, particularly evident in the dispersal of Catholic churches alongside Buddhist and Taoist temples. This layout not only visually represents cultural diversity but also stands as a tangible testament to historical and religious interchange and amalgamation. The centrally located church, with its amalgamation of Chinese and Western architectural motifs, underscores not just the influence of Catholicism but also showcases cultural accommodation and ingenuity. Buddhist and Taoist temples, especially the iconic A-Ma Temple, embody the maritime culture and indigenous beliefs, thereby reinforcing the locale’s distinctiveness and highlighting Macau’s unique position in the interplay between local and foreign cultures within the globalized framework. Nonetheless, this configuration prompts contemplation on whether religious spaces could potentially exacerbate community segregation and whether interfaith dialogues are adequately profound. Religious institutions foster societal connections and cultural identity primarily through festive observances and educational endeavors, encompassing celebrations like Christmas, Buddha’s Birthday, and Mazu’s Birthday, alongside secular exhibitions, and educational initiatives. These endeavors effectively bolster community cohesion and cultural identity, serving as vessels of collective recollection and experience. They reinforce residents’ sense of identity and belongingness while fostering cross-cultural comprehension and respect. However, it has emerged as a pivotal consideration whether the endeavors undertaken by religious institutions are adequately inclusive, averting exclusivity. Furthermore, maintaining cultural openness and dynamic progression while bolstering cultural identity to prevent cultural stagnancy has become a pertinent challenge.

- The functions of religious sites have undergone significant adaptations and transformations in response to social changes. This evolution is evident in their functional expansion and adaptive transformations. Specifically, religious sites have progressed from being exclusively devoted to worship activities to serving as multifaceted hubs for cultural education, event exhibitions, and an array of community services. This shift illustrates a proactive adaptation to societal shifts and a willingness to embrace a broader role in the community. However, while the spatial practices associated with Macau’s religious culture are driving urban renewal and shaping economic models, they also reveal the potential downsides of tourism on the cultural exploitation of these religious spaces. In pursuit of economic gains and enhancement of the city’s image, it is imperative to explore sustainable methods for balancing the protection of religious cultural heritage, preserving the purity of religious practices, safeguarding community rights, and promoting tourism. By doing so, religious spaces can not only maintain their inherent roles of spiritual guidance and social integration in the face of social changes but can also evolve to meet diverse societal needs, ultimately achieving a harmonious coexistence of cultural and economic values.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agyekum, Boadi, and Bruce K. Newbold. 2016. Religion/spirituality, therapeutic landscape and immigrant mental well-being amongst African immigrants to Canada. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 19: 674–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, Divinah. 2023. The Impact of Globalization on the Traditional Religious Practices and Cultural Values: A Case Study of Kenya. International Journal of Culture and Religious Studies 4: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudon, Raymond. 1999. Les formes élémentaires de la vie religieuse: Une théorie toujours vivante. L’Année Sociologique (1940/1948-) 49: 149–98. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Prado Sonia. 2019. Macau’s bridging role between China and Latin America. Megatrend Revija 16: 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Christina Miu Bing. 1999. Macau: A Cultural Janus. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Hon-Fai. 2017. Catholics and Everyday Life in Macau: Changing Meanings of Religiosity, Morality and Civility. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chivallon, Christine. 2001. Religion as Space for the Expression of Caribbean Identity in the United Kingdom. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 19: 461–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, Keith, Hilary du Cros, and Wenmei Li. 2012. The search for World Heritage brand awareness beyond the iconic heritage: A case study of the Historic Centre of Macao. Journal of Heritage Tourism 7: 323–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eh, Edmond. 2017. Chinese Religious Syncretism in Macau. Orientis Aura: Macau Perspectives in Religious Studies 2: 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Fu. 1999. Religious Culture in Macau. World Religions and Cultures, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, Jonathan, Jerry Israel, and Hilary Conroy, eds. 1991. America Views China: American Images of China Then and Now. Bethlehem: Lehigh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Zhidong. 2011. Macau History and Society. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Linsheng, Yashan Chen, and Yile Chen. 2023. Origin, development and evolution: The space construction and cultural motivations of Shi Gandang temple in Macau. Open House International 49: 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyeonjeong, Kim. 2008. The Importance of Communities being able to Provide Venues for Folk Performances and the Effect: A Japanese Case Study. International Journal of Intangible Heritage 3: 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Jinhua. 2018. Gender, Power, and Talent: The Journey of Daoist Priestesses in Tang China. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaymaz, Isil. 2013. Urban landscapes and identity. In Advances in Landscape Architecture. Rijeka: IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Muhammad Imran. 2014. Cultural Identities in Macau. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268507945 (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Knott, Kim. 2015. The Location of Religion: A Spatial Analysis. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, Kim. 2016. How to study religion in the modern world. In Religion in the Modern World: Traditions and Transformations, 3rd ed. Edited by Linda Woodhead, Christopher Partridge and Hiroko Kawanami. London: Routledge, pp. 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, Kim. 2017. The tactics of (in) visibility among religious communities in contemporary Europe. In Dynamics of Religion: Past and Present. Proceedings of the XXI World Congress of the International Association for the History of Religions. Berlin: De Gryter, pp. 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, Neil. 2001. New ways of experiencing culture: The role of museums and marketing implications. Museum Management and Curatorship 19: 417–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laliberté, André. 2022. Welfare and Chinese Religions in Post-colonial Contexts. In Chinese Religions and Welfare Regimes Beyond the PRC: Legacies of Empire and Multiple Secularities. Singapore: Springer, pp. 159–83. [Google Scholar]

- Laven, Mary. 2011. Mission to China: Matteo Ricci and the Jesuit Encounter with the East. London: Faber & Faber. [Google Scholar]

- Law, Kam-Yee. 2012. Chinese Nationalism in Harmony with European Imperialism: Historical Representation at the Macau Museum. In China’s Rise to Power: Conceptions of State Governance. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 165–79. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Kangying. 2010. The Ming Maritime Trade Policy in Transition, 1368 to 1567. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yu. 2011. The True Pioneer of the Jesuit China Mission: Michele Ruggieri. History of Religions 50: 362–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungstedt, Anders. 1832. Contribution to an Historical Sketch of the Portuguese Settlements in China: Principally of Macao, of the Portuguese Envoys & Ambassadors to China, of the Roman Catholic Mission in China and of the Papal Legates to China. Hague: National Library of the Netherlands, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ly, Tuan Phong, and Xiuchang Tan. 2023. Temple keepers in religious tourism development: A case in Macao. Journal of Heritage Tourism 18: 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons-Padilla, Sarah, Michele J. Gelfand, Hedieh Mirahmadi, Mehreen Farooq, and Marieke Van Egmond. 2015. Belonging nowhere: Marginalization & radicalization risk among Muslim immigrants. Behavioral Science & Policy 1: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Yiping, and Yutong Chen. 2023. The Inspiration of the Fusion of Chinese and Western Cultures for the Development of Macau City. Journal of Sociology and Ethnology 5: 162–66. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Meredith. 2007. Sacred place and sacred power: Conceptual boundaries and the marginalization of religious practices. In Religion, Globalization, and Culture. Leiden: Brill, pp. 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, Marcelo. 2001. A study of the church of St. Paul in Macao and the transformation of Portuguese architecture. In Historical Constructions. Guimaraes: University of Minho, pp. 237–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pacione, Michael. 2009. Urban Geography: A Global Perspective. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Perdue, Peter C. 2015. 1557: A Year of Some Significance. In Asia Inside Out: Changing Times. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 90–111. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, Francisco Vizeu, Koji Yagi, and Miki Korenaga. 2005. St. Paul College Historical Role and Influence in the Development of Macao. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 4: 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Po, Tam Sai, and Vu Vai Meng. 2013. Temples and their gods in Macao before the 1990s 1. In Macao-Cultural Interaction and Literary Representations. London: Routledge, pp. 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Satasut, Prakirati. 2015. Dharma on the Rise: Lay Buddhist Associations and the Traffic in Meditation in Contemporary Thailand. Rian Thai International Journal of Thai Studies 8: 173–207. [Google Scholar]

- Torri, Davide. 2019. Religious Identities and the Struggle for Secularism: The Revival of Buddhism and Religions of Marginalized Groups in Nepal. Entangled Religions 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, Anh Thuan. 2024. The Attitude of The Chinese and Vietnamese Ruling Class towards Western Astronomy from the 16th to the 18th Centuries. Asian Studies 12: 307–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Liuting. 1999. Macao’s return: Issues and concerns. The Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review 22: 175. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Weijia. 2024. Making older urban neighborhoods smart: Digital placemaking of everyday life. Cities 147: 104814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C. X. George, ed. 2014. Macao: The Formation of a Global City. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Ernest P. 2013. Ecclesiastical Colony: China’s Catholic Church and the French Religious Protectorate. Cary: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yin, J.; Jia, M. Historical Traceability, Diverse Development, and Spatial Construction of Religious Culture in Macau. Religions 2024, 15, 656. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060656

Yin J, Jia M. Historical Traceability, Diverse Development, and Spatial Construction of Religious Culture in Macau. Religions. 2024; 15(6):656. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060656

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Jianqiang, and Mengyan Jia. 2024. "Historical Traceability, Diverse Development, and Spatial Construction of Religious Culture in Macau" Religions 15, no. 6: 656. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060656

APA StyleYin, J., & Jia, M. (2024). Historical Traceability, Diverse Development, and Spatial Construction of Religious Culture in Macau. Religions, 15(6), 656. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060656