Nature, Place, and Ritual: Landscape Aesthetics of Jingfu Mountain “Grotto-Heavens and Blissful Lands” in South China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Overview of the Development of Mount Jingfu

4. Aesthetics of Natural Geography

5. Aesthetics of Place

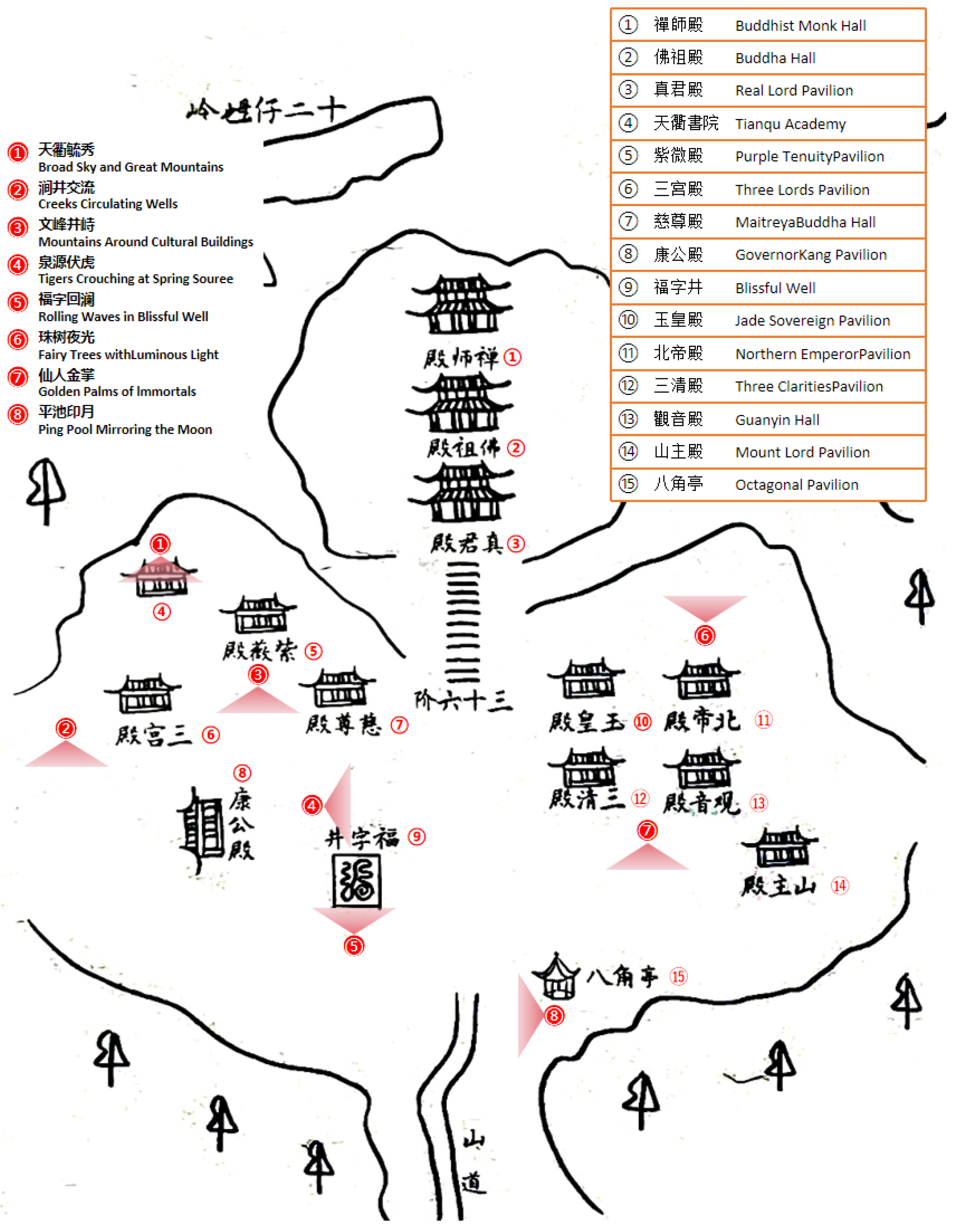

5.1. Aesthetics of Spatial Scenes

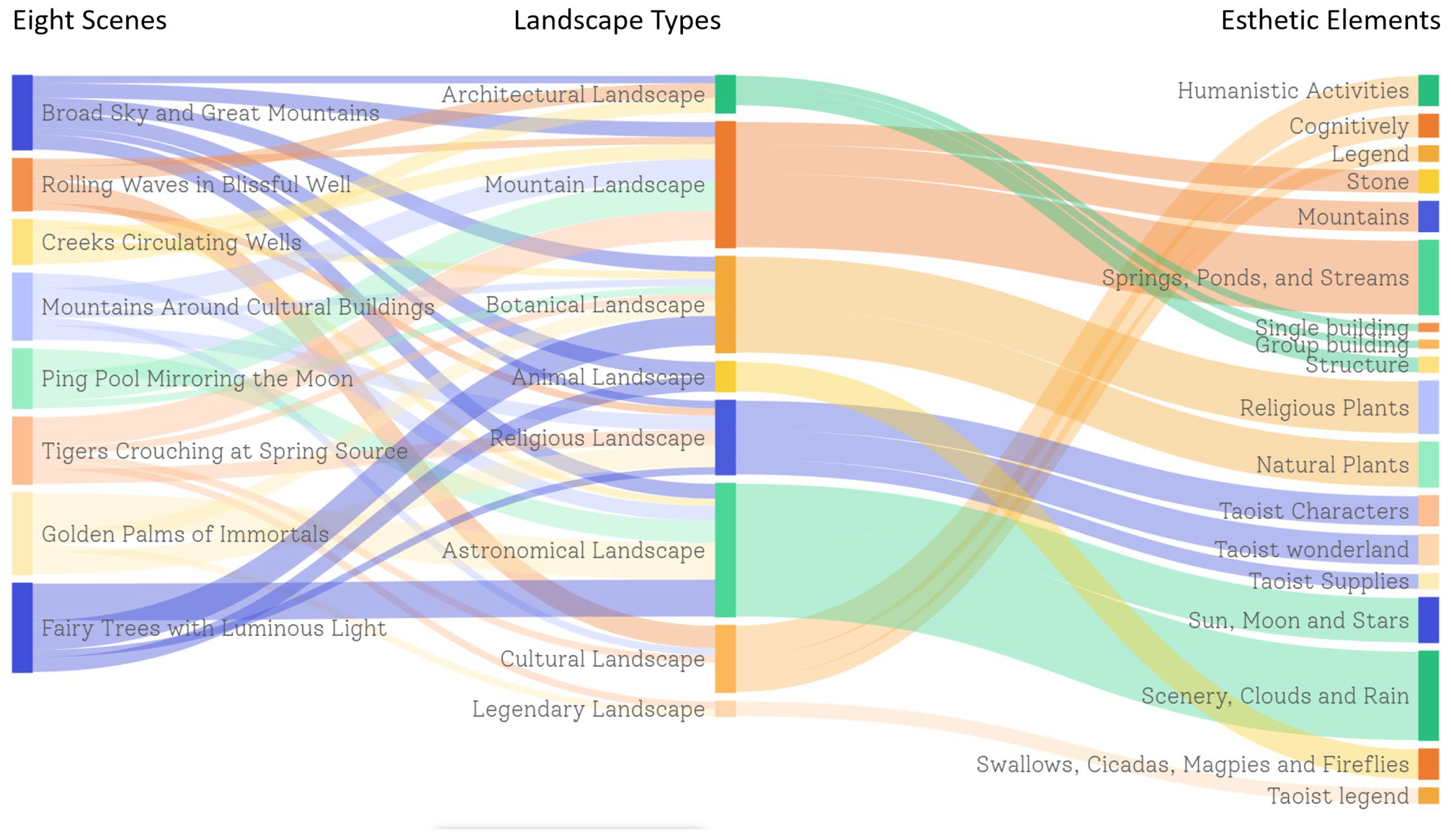

5.2. Aesthetics of the Eight Scenes (Bajing, 八景)

6. Aesthetics of Ritual Activities

6.1. Bloodline Identity Represented by Religious Rites

6.2. Geo-Spatial Identity Represented by High Gods Parade

6.3. Divine Identity Represented by Great God Parade

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

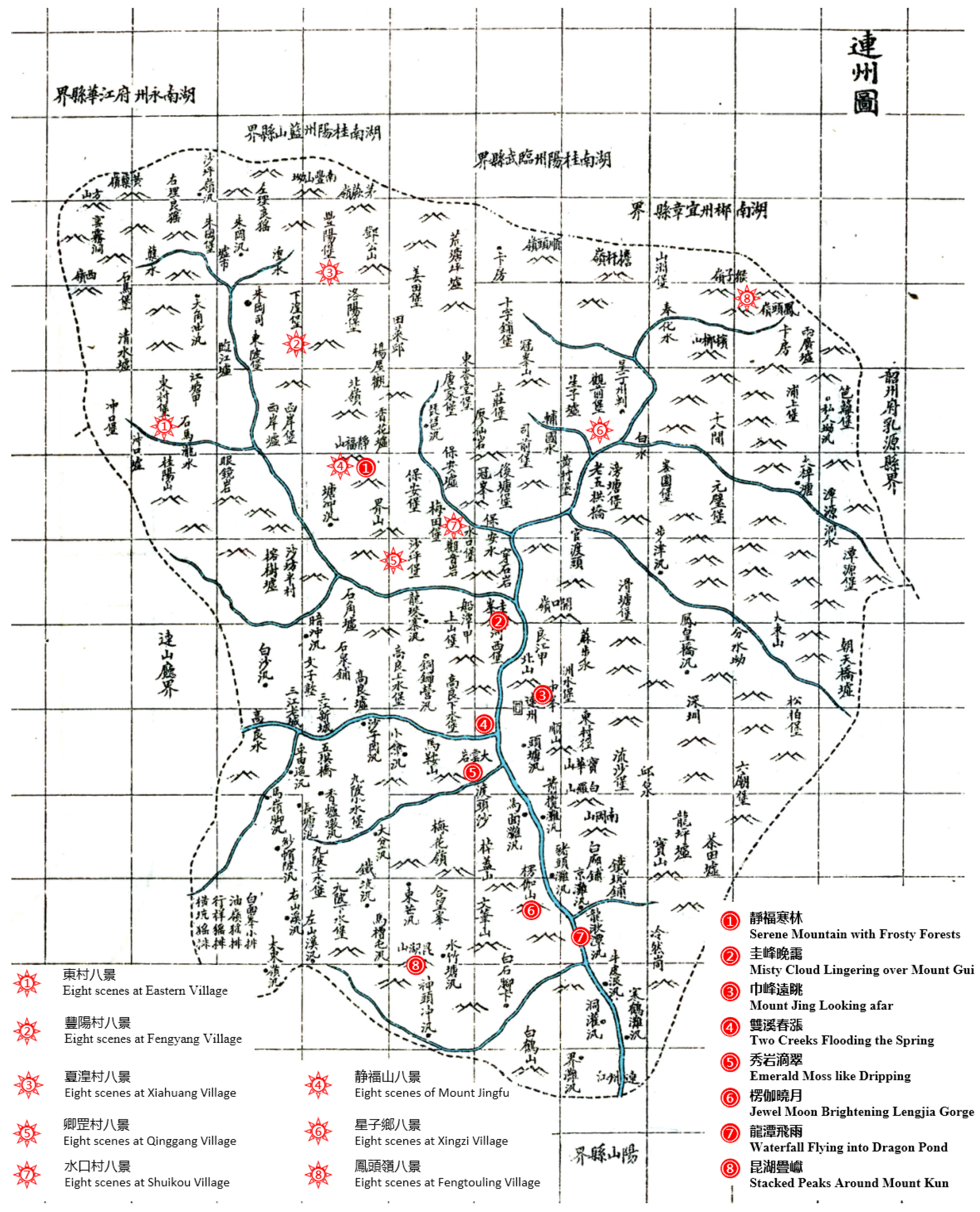

| 1 | Eight Scenes Alongside Huangchuan River: The mother river of Lianzhou City is Lianjiang River, which was known as Huangshui in ancient times, and the entire water basin was called Huangchuan River. Therefore, the eight scenes of Lianzhou City are also known as the eight scenes alongside Huangchuan River. Record of Scenic Spots Across the Country (yudi jisheng, 舆地纪胜 (Wang 2005) and Fang Yu Sheng Lan (方舆胜览) are two comprehensive geographic books of great significance, compiled during the Southern Song Dynasty. These texts specifically document two sets of landscapes, known as the “Eight Views of Xiaoxiang” and the “Eight Scenes Alongside Huangchuan River”. The latter consists of Mount Jing Looking afar (巾峰远眺), Misty Cloud Lingering over Mount Gui (圭峰晚霭), Emerald Moss like Dripping Aurora (秀岩滴翠), Two Creeks Flooding the Spring (双溪春涨), Jewel Moon Brightening Lengjia Gorge (楞伽晓月), Waterfall Flying into Dragon Pond (龙潭飞雨), Stacked Peaks Around Mount Kun (昆湖叠巘) and Serene Mountain with Frosty Forests (静福寒林). |

| 2 | Eight Scenes at Mount Jingfu: Zhang Weiqin is a scholar of the Daoguang era in the Qing Dynasty. He firstly discovered and nominated the eight scenes at Mount Jingfu. Rolling Waves in Blissful Well (福字回澜) (created by Weiqin ZHANG—Qing Dynasty) There’s a pavilion covered like a cap, there’s a stone flat as a grindstone (有亭覆如蓋,有石平如砥) The character “Fu” is patterned after Xiyi, who might have carved it here back then? (福字摹希夷,當年誰勒此?) Wandering leisurely like a gentle wave, trickling endlessly around the clear stream (宛轉約回瀾,涓涓繞清泚) Desiring to float wine cups down a winding stream, the joyful date is already set in Shangsi Festival (欲泛羽觴流,佳期約上巳) Ping Pool Mirroring the Moon (平池印月 (created by Weiqin ZHANG—Qing Dynasty)) The fragrant pond stores clear waves, bright and quiet from delicate dust (芳池蓄清波,皦皦纖塵靜) The bright moon graces the sky, blue waves immerse the treasure mirror (皓月麗中天,碧波沉寶鏡) The pondweed interweaves, the clear light reflects each other (荇藻自交橫,清光互輝映) On a fine night embracing the cold moon, leisurely, I see my nature (良夜抱寒暉,悠然見吾性) Creeks Circulating Wells (涧井交流) (created by Weiqin ZHANG—Qing Dynasty) The divine mechanics of the universe, shape an unusual stone into a funnelled device (造化運神機,奇石辟為筧) The mountain spring gushes forth, the square well contains the clear shallows (山泉汨汨來,方井涵清淺) In this secluded place, worldly dust is scarce, dappled moss paints a colourful scene (境僻俗塵稀,斕班暈苔蘚) Cherishing this isolated spot, a cold goodness arises when the wind blows past (愛此獨遲留,風過冷然善) Tigers Crouching at Spring Source (泉源伏虎) (created by Weiqin ZHANG—Qing Dynasty) A spring opens up with the pace of a tiger, a crimson tripod gathers the osmanthus flowers (泉逐虎蹄開,丹鼎黃芽簇) Flowing since ancient times, the lord of the mountain tamed and subdued here (終古流潺湲,山君此馴伏) Not following the rise of chickens and dogs, always resting at the source of the spring (不隨雞犬升,長踞泉源宿) There will be a moment to leap over layers of cliffs, a single laugh generates breeze in the valley (會當躍層崖,一笑風生穀) Golden Palms of Immortals (仙人金掌) (created by Bo ZHANG—Qing Dynasty) Beyond the wilderness clouds of three autumns, twice-drenched condensed into crimson hues (三秋野雲外,兩潤凝丹彩) Tangerine dawn wields the dew’s shadow, as purple peonies urge orchids to bloom (橙霞揮露影,紫芍催蘭開) Golden palm absorbs the fine essence, jade-like brilliance seals the sacred altar (金掌收氤氣,鎏玉鎮聖臺) Once again, dark greens merge with wild grass, the gleaming light seems like fairyland Penglai (蒼薈複菅莽,瑤光似蓬萊) Broad Sky and Great Mountains (天衢毓秀) (created by Bo ZHANG—Qing Dynasty) In front of the jade green mountains and purple wind, beside the fragrant stream with colourful blossoms (翠微紫風前,椎華香澗邊) Locust branches hold thousands of dews, Cassia trees reach up to the ninth heaven (槐枝承千露,桂木舉九天) Swallows cut the clouds brightly, cicadas sing lying low on the hot hill (剪燕繞雲亮,唱蟬伏丘炎) Over the long wilderness, mountain smoke rises, climbing the path to greet the high immortals (長野山煙起,攀徑謁高仙) Mountains Around Cultural Buildings (文峰并峙) (created by Bo ZHANG—Qing Dynasty), Twin peaks rise abruptly in the south, they stand soaring and leaning in the long empty sky (雙峰聳南起,飛倚長空立) Deep clouds push against the blue sky, and shallow stones wear green moss (雲深推藍影,石淺披青衣) As the poet’s chant reaches the edge of the forest, the Taoist bell echoes back from the west of the river (詩吟出林際,道鐘回河西) Shoulder-to-shoulder, we gaze at this blessed land, waiting for the first rays of the autumn morning (並肩仰福地,秋晨待先曦) Fairy Trees with Luminous Light (珠树夜光) (created by Bo ZHANG—Qing Dynasty). The fair leaves sway casting silhouettes, the night magpie returns kicking up dust (嘉葉搖暗影,夜鵲撲塵歸) The moon shines brightly with sparse stars accompanying, in the gentle wind, fireflies fly (月明稀星伴,風柔眾螢飛) Cassia blooms hide in the smoke cage, the tall camphor tree hangs jade shells (桂舒掩煙籠,樟挺懸玉貝) Summer sentiments weave into dreams, in this blessed land, we search for fragrant blossoms (夏情牽入夢,福瀛覓芳菲) |

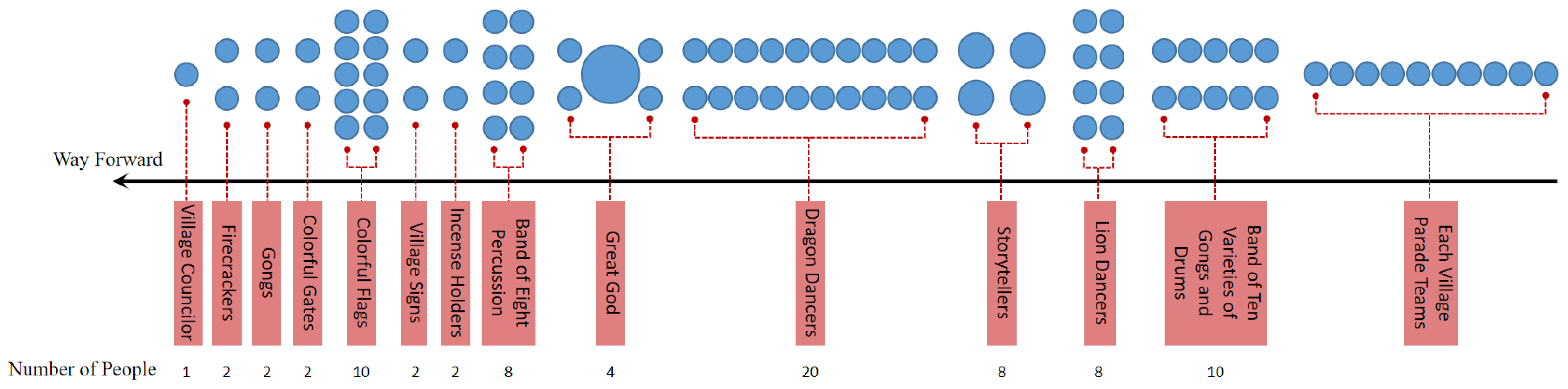

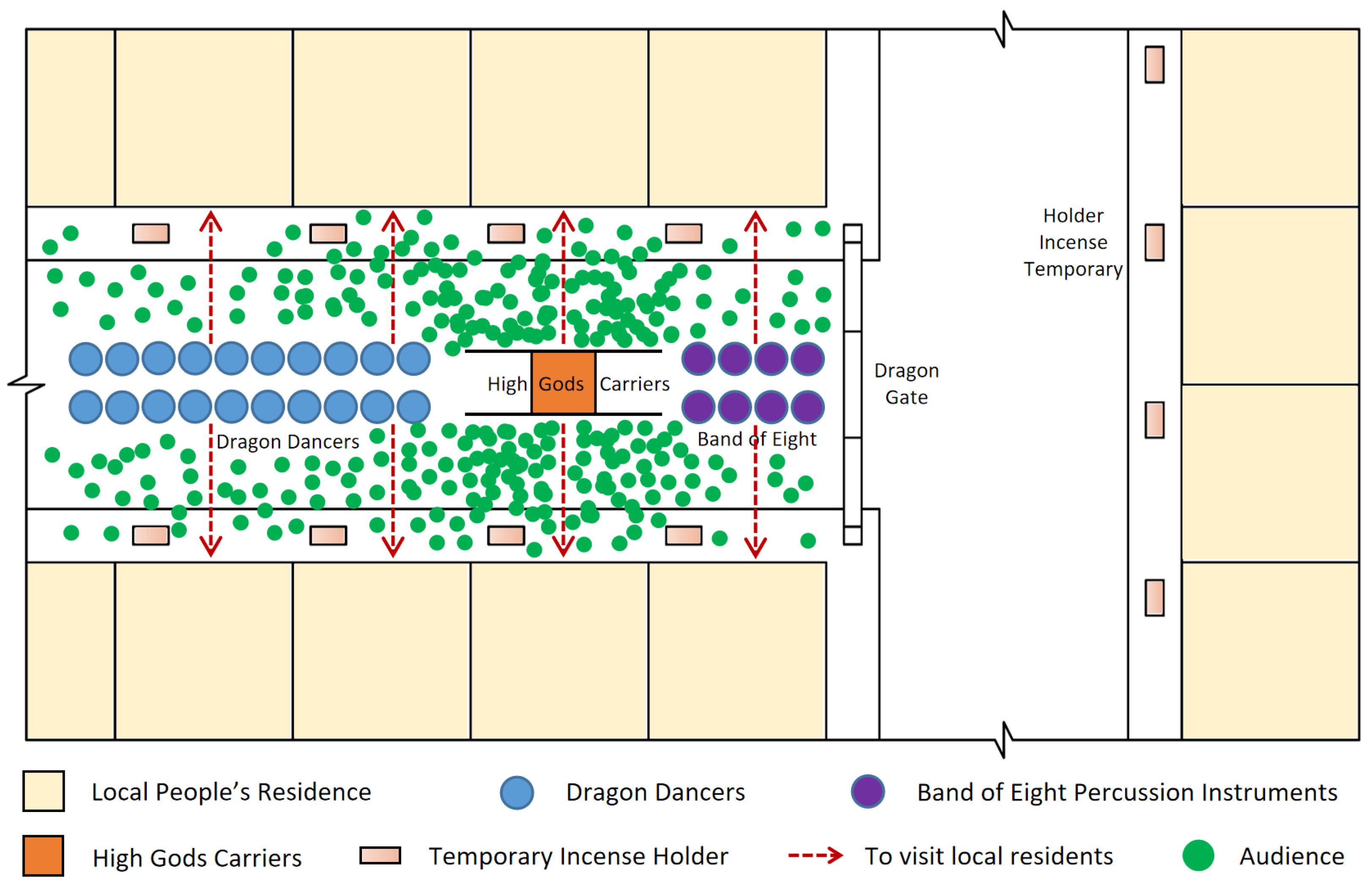

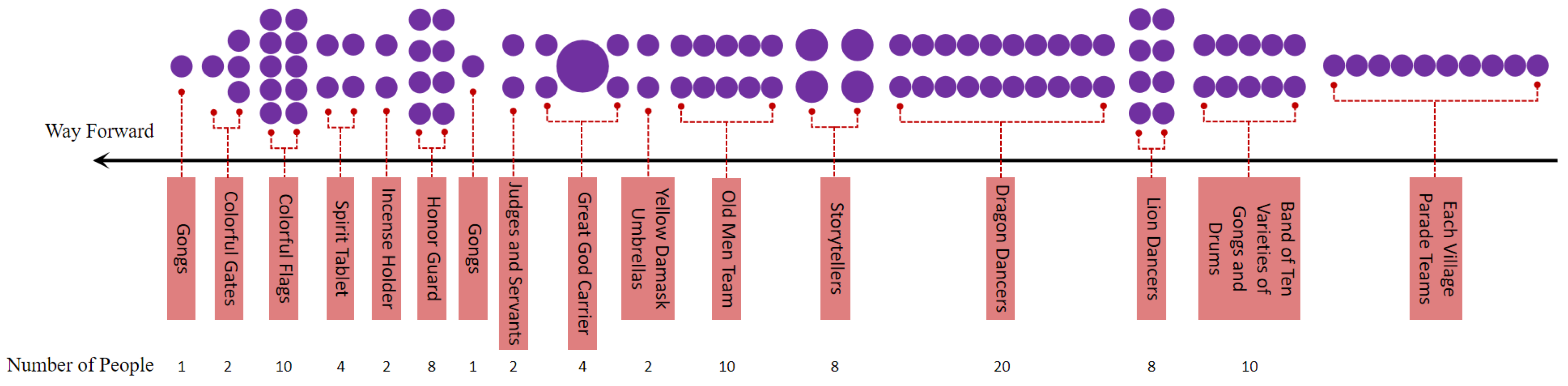

| 3 | Bao’an Great God Parade held during the Double Ninth Festival is also called the god pageant ceremony which is a custom based on local Chinese popular exorcistic religion to honor the gods and ward off disasters while bringing blessings in Bao’an Town. As per Buddhist Classics and Topography of Mount Hengshan (nanyue zongsheng ji, 南岳总胜集), the original prototype to be worshipped was Real Lord Liao Chong who was venerated by the local people. Over time, the ceremony evolved and was inherited, eventually transforming into a customary event for commemorating ancestors, seeking good fortune, and preventing disasters. It also serves as a means for the community to gather with their relatives and friends. |

| 4 | The Great God refers to Shaohao, also known as Jin Tian (金天), who is the Lord of Mount Hua (xiyue chuanzhu, 西岳川主). In the Bao’an Great God Parade, one of the local elders will be chosen to act as the Great God who sits on a dragon-shaped chair wearing a mask with a serene expression, a dragon robe, and a divine umbrella over the head. Each village takes turns playing the role of the Great God annually. |

| 5 | High Gods are locally known as Gao Gong (高公), and in ancient times, there were 72 Gao deities, such as Liao Chong, Meng Binyu, Cai Qiji, General Bai and Aunt Liao. |

| 6 | Storytellers (gushi, 故事) are played by children dressed in little dragon robes and official hats, mainly modelled after the Beijing Opera and Qi Opera plays. These performances often feature classic plays such as The Oath of Brotherhood in the Peach Garden, Legend of the White Snake and Wu Song Fighting a Tiger. |

| 7 | Ten varieties of gongs and drums make up a form of folk music consisting of blowing and beating, popular in the Xingzi language area of Lianzhou City. The instruments comprise the high-side gong, small gong, hard gong, high-side drum, flat drum, Mandong drum, wooden fish, medium cymbal, small cymbal, and suona. Before the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, this type of folk music was exclusively performed during the god pageant ceremony. |

| 8 | Shaking the Gods is a ceremony in which people wearing masks stand on the deity carriers and act as the Great God and High Gods who are raised high by eight men. When they reach a house, the audience shouted “swing the gods”. They respond by swinging the gods from side to side, and it seems that the actors are dancing like fairies with long sleeves. |

| 9 | Treading on the Eight Diagrams is a dance of Daoist origin in which the dancers perform in the Eight Diagrams steps. |

References

- Brace, Catherine, Adrian R. Bailey, and David C. Harvey. 2006. Religion, place and space: A framework for investigating historical geographies of religious identities and communities. Progress in Human Geography 30: 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Mengyuan. 2022. Idealizing a Daoist Grotto-Heaven: The Luofu Mountains inLuofu Yesheng 羅浮野乘. Religions 13: 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Wei 陳蔚, and Rui Tan 譚睿. 2021. A Study on the Cultural Landscape of Daoist “Heaven and Earth in Caves” and the Spatial Structure of Hutian”. Architectural Journal 4: 108–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Roger A. 1990. Geographies and religious commitment in a small coastal parish. Geography of Religions and Belief Systems 12: 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, Tim. 2014. Place: An Introduction. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, Kenneth, and Zhenman Zheng 鄭振滿. 1992. A Preliminary Study of Taoism and Popular Cult Worship in Fujian and Taiwan (閩臺道教與民間諸神崇拜). Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology Academia. Taipei, Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica 73: 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Chunlan 杜春蘭, and Jing Wang 王靖. 2014. Coupling Between Literary Context and Landscape Space—A Case Study of Ancient “Eight Views” in Chongqing. Journal of Human Settlements in West China 29: 101–6. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Guangting 杜光庭 [Five Dynasties 五代]. n.d. The Records of Daoist Spiritual Experience. 道教靈驗記. In Chinese Daozang 中華道藏; Vol. 2, “The Experience of Dividing the Boundary at Jingfu Mountain 靜福山分界驗”. Beijing: HuaXia Publishing House.

- Du, Shuang 杜爽, and Feng Han 韓鋒. 2019. Study on the Origins of the Abroad Sacred Mounts from the Perspective of Cultural Landscape. Chinese Landscape Architecture 35: 122–27. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1925. Les Formes e’l’ementaires de la vie religieuse. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Feuchtwang, Stephan. 2021. Popular Religion in China: The Imperial Metaphor. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Hong 葛洪 [Eastern Jin dynasty 東晉]. 2002. The Inner Chapters of the Baopuzi 抱樸子內篇. Beijing: Hualing Publishing House 華齡出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Fei 郭棐. 1996. Wanli Guangdong Annals 萬曆廣東通志. Jinan: Shandong Qilu Book Publishing Co., Ltd., vol. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Yulin 郝玉麟 [Qing dynasty 清代]. n.d. Guangdong Tongzhi 廣東通志. In Siku Quanshu 四庫全書. Beijing: Beijing Publishing Group, vol. Temples 道觀卷, p. 180.

- Jones, Peter Blundell. 2016. Architecture and Ritual: How Buildings Shape Society. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Kai 劉凱. 2011. The Development of Taoism at Jingfu Mountain in Lianzhou from the Sixth Dynasty to the Tang and Song Dynasties: Centered on Jiang Fang’s Inscription of Mr. Liao in Jingfu Mountain of Lianzhou in the Tang Dynasty. Lingnan Culture and History 4: 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, David N., Margaret C. Keane, and Frederick W. Boal. 1998. Space for religion: A Belfast case study. Political Geography 17: 145–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Zhou 呂舟. 2018. Dongtianfudi 洞天福地--World Heritage Value and Preliminary Comparative Study. Beijing: Tsinghua University-National Heritage Center. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Shiqi 苗詩麒, Hexian Jin 金荷仙, and Xin Wang 王欣. 2017. Analysis on Landscape Layout of ‘Caverns of Heaven and Place of Blessing’ in Jiangnan. Chinese Landscape Architecture 33: 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Zhange 穆彰阿, and Xien Pan 潘锡恩 [Qing dynasty 清代]. n.d. Qing Dynasty Unification Records 大清統一志. In Siku Quanshu 四庫全書. Beijing: Beijing Publishing Group, vol. Lian Zhou 連州卷, p. 284.

- Norberg-Schulz, Christian. 1980. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture. Milano: Mondadori Electa Spa. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, Marwyn S. 1979. Biographies of Landscape. The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes, Geographical Essays. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, Hall, ed. 1997. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Verschuuren, Bas. 2007. Believing Is Seeing: Integrating Cultural and Spiritual Values in Conservation Management. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/45804 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Wang, Xiangzhi 王象之 [Song dynasty 宋代]. 2005. The Record of Scenic Spots Across the Country (Yu Di Ji Sheng 輿地紀勝), Volume 92, Xian Shi 仙釋. Chengdu: Sichuan University Press, p. 3199. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yifan, Jie Zhang, Yingjun Li, Xiaolei Ma, and Wentai Cui. 2022. An Architectural Ethnography of the Historic Neighborhood of Pujing in Quanzhou and the ‘Spirit of Place’. Architectural Journal 3: 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Zhong 吳中 [Ming dynasty 明代]. n.d. Temple 寺觀. In Chenghua Guangzhou Zhi 成化廣州志. Beijing: Nationat iibrary of China Publishing House, pp. 1465–87.

- Xie, Yuhan 謝雨含. 2021. A Study on “Cave Paradise” from the Perspective of Landscape Prototype. Master’s thesis, Hainan University, Haikou, China. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Xiaodan 楊曉丹, Shusheng Wang 王樹聲, Xiaolong Li 李小龍, and Qirui Zhang 張琪瑞. 2022. Eight Scenes: A Native Model of Urban and Rural Residential Landscape Creation. City Planning Review 46: 125–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Junfang 張君房 [Song dynasty 宋代]. 2003. The Seven Dances of Yunji 雲笈七籖. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, vol. 27, p. 627. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Qingqing 鄭青青, Hexian Jin 金荷仙, and Chuwen Chen 陳楚文. 2020. Taoism in the Mountain, Thoughts Penetrate the Universe—A Study on the Evolution of Mountain Landscape and Cultural Image of “Cavern of Heaven and Place of Blessing” in Tiantai Mountain, Zhejiang. Chinese Landscape Architecture 36: 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Xia 鄭俠 [Song dynasty]. n.d. Xitang Collection 西塘集. In Siku Quanshu 四庫全書; Volume The Records of the True Lord Lingxi of Lianzhou 連州靈禧真君記. Beijing: Beijing Publishing Group, p. 395.

- Zheng, Zhenman 郑振满, and Chunsheng Chen 陈春生. 2003. Folk Beliefs and Social Space. Fuzhou: Fujian People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

| Major Years | Sources | Scale and Organisational Changes |

|---|---|---|

| 3rd year of Datong era of the Southern Liang Dynasty (529 A.D.) | Monument to Liao Chong at Mount Jingfu of Lianzhou City | Liao Chong lived here. |

| 2nd year of Guangda era of the Southern Chen Dynasty (568 A.D.) | Records of Lianzhou Real Lord of Overflowing Happiness | People worshiped Liao’s residence as a Daoist temple. They named the temple “Qingxv” (Liao’s courtesy name). |

| Xiantian and Tianbao eras of Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang Dynasty (712–742) | Chart of the Palaces and Bureaus of the Grotto-Heavens and Blissful Lands | Mount Baofu (the old name of Mount Jingfu) was ranked 49th among the Seventy-two Daoist Grotto-Heavens and Blissful Lands. |

| Five Dynasties (581–907) | Boundary Separation Experience on Mount Jingfu | Some monks occupied Mount Jingfu. |

| Five Dynasties (581–907) | Da Qing Yi Tong Zhi (the previous version) | Tianqu Academy where a native named Huang Sun read was built. |

| Qianxing era of the Song Dynasty (1022) | Da Qing Yi Tong Zhi | Emperor Zhenzong ennobled Liao Chong as the Real Lord of Numinous Support. |

| 1st year of Yuanfeng era of the Song Dynasty (1078) | Records of Lianzhou Real Lord of Overflowing Happiness | Emperor Shenzong ennobled Liao Chong as the Real Lord of Overflowing Happiness. |

| 1st year of Longxing era of the Song Dynasty (1163) | Local Chronicles of Guangdong in Qing Dynasty | Emperor Xiaozong granted the title of Abbey of the Real Lord of Overflowing Happiness. |

| 3rd year of Baoqing era in the Song Dynasty (1227) | Record of Scenic Spots Across the Country | Mount Jingfu, also known as Serene Mountain with Frosty Forests, is one of the eight scenes alongside Huangchuan River. |

| 2nd year of Duanping era in the Song Dynasty (1235) | Guangzhou Chronicles | The government and citizens raised funds to reconstruct the temples. |

| 7th year of Tianshun era in the Ming Dynasty (1463) | The governor Zhu Yun reconstructed the place. | |

| 39th year of Wanli era in the Ming Dynasty (1601) | The place was reconstructed. | |

| 7th year of Tianqi era in the Ming Dynasty (1626) | ||

| 47th year of Emperor Kangxi in the Qing Dynasty (1708) | The governor Wang Jimin and others advocated for the restoration. | |

| Early years of the Qing Dynasty | The stable spatial layout of 12 palaces. | |

| Lianzhou Chronicles (in the Tongzhi era) | The scholar Zhang Weiqin discovered and nominated the eight scenes at Mount Jingfu. | |

| 7th year of Emperor Qianlong in the Qing Dynasty (1742) | Liao Mulu, Liao Chong’s descendants, and others advocated for the restoration. | |

| 11th year of Emperor Guangxv in the Qing Dynasty (1806) | Liao Chong’s descendants advocated for the restoration. | |

| 22nd year of Emperor Guangxv in the Qing Dynasty (1896) | Liao Yuankai, Liao Chong’s descendants, and others advocated for the restoration. | |

| 28th year of the Republic of China (1939) | Lianzhou County Chronicles | The Guangdong provincial government established a correctional institution at Mount Jingfu. |

| 37th year of the Republic of China (1948) | Buddhist Monk Hall was destroyed and a new platform for Bao’an Village was constructed using demolished brick and wood materials. | |

| 1950 | The first district government demolished the palaces on Mount Jingfu and used the brick and wood materials to strengthen Bao’an Gospel of Grace Church as its office building. | |

| 1951 | Bao’an Grain Management Agency demolished the palaces on Mount Jingfu and used brick and wood materials to build a grain storehouse on the west side of the Jielongmen Gate of Wenming Fang. | |

| 1955 | Bao’an Supply and Marketing Agency demolished the palaces on Mount Jingfu and used brick and wood materials to strengthen the Ouyang’s Great Water Shrine and to construct its office building. |

| Landscape Elements | Architectural | Mountain | Botanical | Animal | Religious | Astronomical | Cultural | Legendary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rolling Waves in Blissful Well | pavilion | Stone\clear stream | —— | —— | Xiyi | —— | float wine cups\character “Fu”\Shangsi festival | grindstone |

| Ping Pool Mirroring the Moon | —— | ping pool\fragrant pond\clear waves\blue waves | pondweed | —— | —— | Moon\bright moon\cold moon | —— | —— |

| Creeks Circulating Wells | funnelled device\square well | unusual stone\mountain spring | dappled moss | —— | secluded place | cold wind | —— | —— |

| Tigers Crouching at Spring Source | —— | Spring\stream\cliffs\valley | osmanthus flowers | tiger | crimson tripod\lord of the mountain | —— | tamed and subdued the tiger | the rise of chickens and dogs |

| Golden Palms of Immortals | —— | —— | purple peonies\wild grass | —— | Immortals\sacred altar | Clouds\dawn\dew\rain\gleaming light | —— | golden palms\Penglai |

| Broad Sky and Great Mountains | Tianqu academy | green mountains\fragrant stream | locust trees\cassia trees | Swallows\cicadas | high immortals | purple wind | —— | —— |

| Mountains Around Cultural Buildings | —— | Mountains\twin peaks\stones\river | green moss | —— | Taoist bell\blessed land | Clouds\blue sky\morning rays | chant poet | —— |

| Fairy Trees with Luminous Light | —— | —— | fairy trees\fair\cassia blooms\fragrant blossoms\camphor tree | night magpie\fireflies | —— | luminous light\brightly moon\sparse stars\ wind | —— | blessed land |

| a Village Rotation Year during the Republic of China | b Village Rotation Year after 1985 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Rotation Village | High God | Year | Rotation Village | High God |

| 1940 | Wanquan Fang | Meng Binyu | 1985 | Yuxiu Fang | General Bai |

| 1941 | Dongxing Fang | Lord Wang | 1986 | Dongxing Fang | Lord Wang |

| 1942 | Wanquan Fang | Meng Binyu | 1987 | Wanquan Fang | Meng Binyu |

| 1943 | Wenming Fang | Grand Guardian Cai | 1988 | Wenming Fang | Grand Guardian Cai |

| 1944 | Wanquan Fang | Meng Binyu | 1989 | Yuxiu Fang | General Bai |

| 1945 | Yuxiu Fang | General Bai | 1990 | Dongxing Fang | Lord Wang |

| 1946 | Wanquan Fang | Meng Binyu | 1991 | Wanquan Fang | Meng Binyu |

| 1947 | Dongxing Fang | Lord Wang | 1992 | Wenming Fang | Grand Guardian Cai |

| 1948 | Wanquan Fang | Meng Binyu | 1993 | Yuxiu Fang | General Bai |

| 1949 | Wenming Fang | Grand Guardian Cai | |||

| Type | Content |

|---|---|

| Familial Representation |

|

| Geographic Representation |

|

| Divine Representation |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Zeng, C.; Tang, X.; Bai, Y.; Wang, X. Nature, Place, and Ritual: Landscape Aesthetics of Jingfu Mountain “Grotto-Heavens and Blissful Lands” in South China. Religions 2024, 15, 643. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060643

Xu Y, Zeng C, Tang X, Bai Y, Wang X. Nature, Place, and Ritual: Landscape Aesthetics of Jingfu Mountain “Grotto-Heavens and Blissful Lands” in South China. Religions. 2024; 15(6):643. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060643

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Yingjin, Canxu Zeng, Xiaoxiang Tang, Ying Bai, and Xin Wang. 2024. "Nature, Place, and Ritual: Landscape Aesthetics of Jingfu Mountain “Grotto-Heavens and Blissful Lands” in South China" Religions 15, no. 6: 643. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060643

APA StyleXu, Y., Zeng, C., Tang, X., Bai, Y., & Wang, X. (2024). Nature, Place, and Ritual: Landscape Aesthetics of Jingfu Mountain “Grotto-Heavens and Blissful Lands” in South China. Religions, 15(6), 643. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060643