Group Formative Processes in 2 Cor 6:14–7:1

Abstract

1. Introduction

I regard the social sciences as heuristic devices that can help interpreters pay attention to social aspects and processes of identity formation in the texts. While general social theories cannot answer specific historical questions, they can help an interpreter pay attention to social processes and raise interesting questions about the historical material under investigation.

2. State of the Research

2.1. Authenticity

2.2. The Referent of οἱ ἄπιστοι

2.2.1. Opponents

2.2.2. Outsiders in General

3. The Opponents

4. Theory

4.1. The Model of the Self-Categorical Relationship

4.2. Application of the Model

5. The Boundaries of the Corinthian Christ Community

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For bibliographies about this pericope until 2010, see (Bieringer et al. 2008, pp. 94–100; Schmeller 2010, pp. 366–67). |

| 2 | For the translation οἱ πίστοι and οἱ ἄπιστοι as “(dis)loyal” rather than the more common “(un)believer”, see (Morgan 2015, p. 240; Muraoka 2009). |

| 3 | For other proposed references of οἱ ἄπιστοι, see Section 2.2 and furthermore: (Thrall 2004, pp. 926–45; Lim 2020, p. 328). |

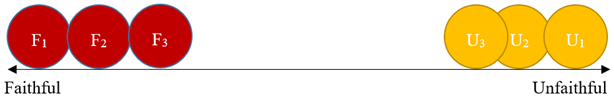

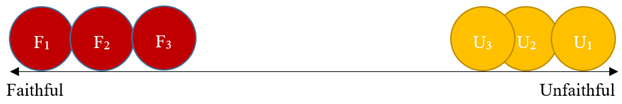

| 4 | For a fruitful use of tools from the Social Identity Approach, see (Clarke and Tucker 2016, p. 46; Kuecker 2011; Trebilco 2014b; Baker 2012; Newsom 2007). |

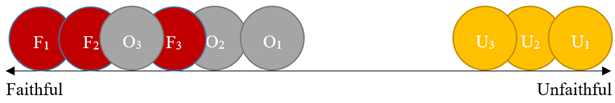

| 5 | For borrowing tools from sociolinguistics in a heuristic manner, see (Kok 2014). |

| 6 | For the Jewish background on ‘wearing the same yoke’, see Deut 22:10 and Lev 19:19 (LXX). The scholars illustrate how 2 Cor 6:14–7:1 functions almost like a Midrash on certain Old Testament Passages: (Beale 1989; Brooke 2014, p. 9; Leppä 2005, p. 374). |

| 7 | Mat 11:29–30; Acts 15:10; Gal 5:1; 1 Tim 6:1; Rev 6:5; Mishna, ʾAvot 3.5; Talmoed b. Ber. 12b, 13a–b, 14b. |

| 8 | 1. For untrustworthy persons, see (Duncan and Derrett 1978); 2. gentile Christians who do not keep the Law, see (Gunther 1973); 3. immoral people within the church community, see (Newton 1985; Wendland 1980; Lategan 1984); 4. Paul’s opponents in Corinth, see (Rensberger 1978; Barentsen 2011, p. 168); 5. all non-Christians, see (Webb 1992a, 1992b). |

| 9 | In Georgi’s view τῶν ὑπερλίαν ἀποστόλων and ψευδαπόστολοι have the same referent, namely Paul’s opponents. See also (Taylor 2005). |

| 10 | Cf. 1 Cor 7:12–15; 14:22–24; 1 Cor. 10:33; Gal 6:10; Col 4:5–6; 1 Tess 3:12,4:11–12; 5:15. |

| 11 | This opinion has recently been defended and provided with new arguments by (Lang 2018; Sierksma-Agteres 2023, pp. 550–57). |

| 12 | 2 Kgs 19:4,16; 18:33–35; 19:12,18; Isa 37:17; Jer 10:8–10; 1 Tess 1:9; Acts 14:12–15; 17:16. |

| 13 | 1 Cor 5:10–11; 6:9; 8:1, 4 (2x), 7 (2x), 10 (2x); 10:7, 14, 19 (2x), 28; 12:2. |

| 14 | 1 Cor 6:6; 7:12, 13, 14 (2x), 15; 10:27; 14:22 (2x), 23, 24. |

| 15 | 1 Cor 6:6; 7:12, 13, 14 (2x), 15; 10:27; 14:22 (2x), 23, 24. 2 Cor 4:6; 6:14, 15. |

| 16 | 1 Cor 6:6; 7:15; 10:27. |

| 17 | During ancient times, suffering was generally not considered honourable. However, there were some exceptions to this rule. For instance, it was considered an honourable act to suffer for one’s religion and people, see (Luckritz Marquis 2013; Van Henten and Avemarie 2002; Barton 2001). Similarly, Christ followers believed that suffering for the sake of Christ was a great honour (cf. 1 Pet 4:12–19). |

| 18 | The purpose is not to present a full description of the model, but only so far as it is helpful to the exegesis. |

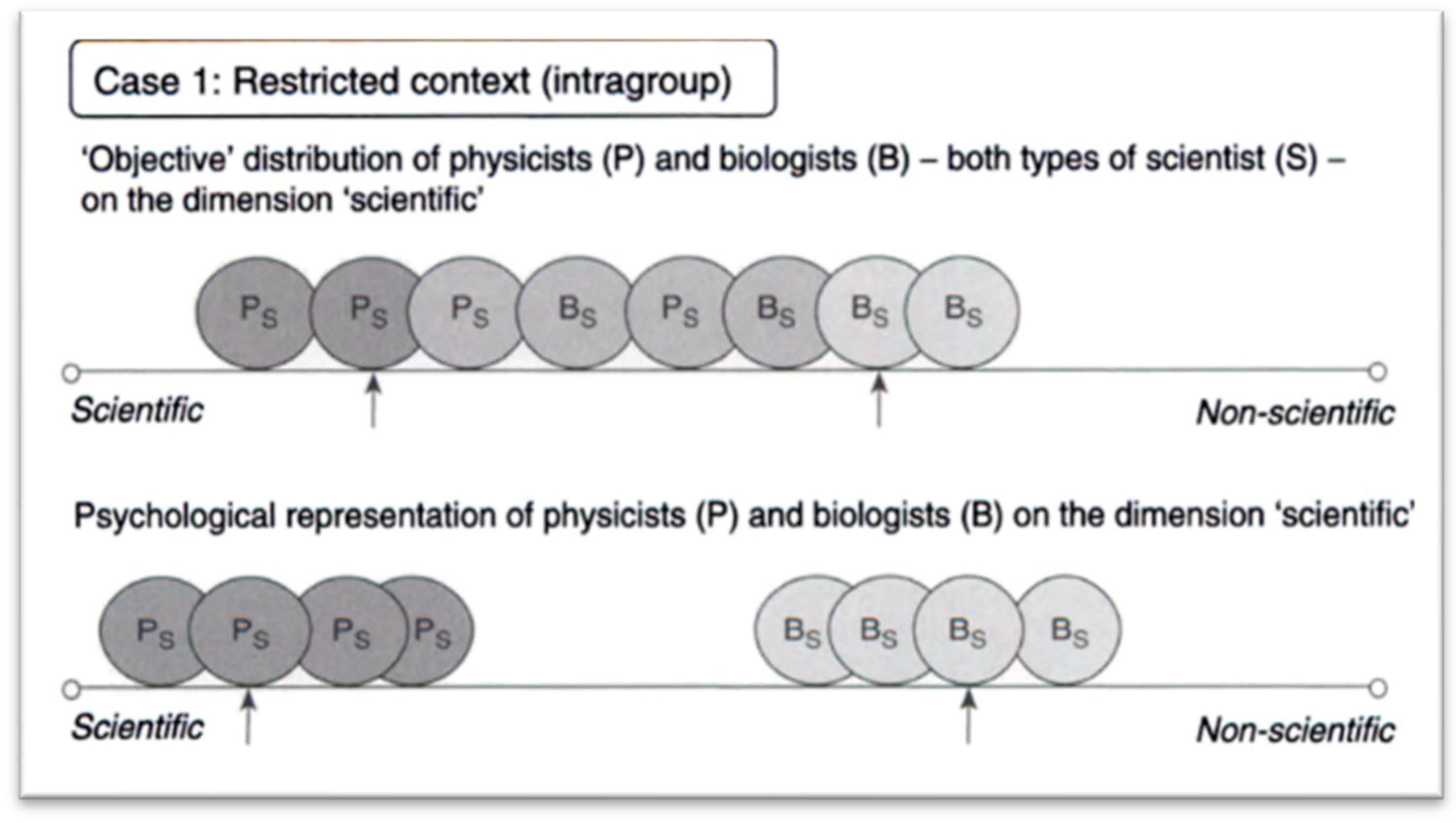

| 19 | Self-categorical relationship is the perceiving of the self in relation to others as an interchangeable member of a category that is defined at a particular level of abstraction. |

| 20 | For New Testament studies on self-categorisation in a shifting context, see (Malina 1993). For the place of Haslam’s book within the framework of Social Identity Studies, see the foreword of his book: (Haslam 2004, pp. xvii–xx, 33). |

| 21 | Figure 1 is in an adapted form derived from (Haslam 2004, p. 33). |

| 22 | Figure 2 is in an adapted form derived from (Haslam 2004, p. 33). |

| 23 | Stereotypes are a set of simplified and rigid beliefs about the attributes of a social group: (Fisher and Kelman 2011, p. 64). For ‘stereotyping’ in the ancient world, see (Hakola 2008). |

| 24 | For this technical term, see Section 4.1. |

| 25 | The opponents (O1, O2, O3) are randomly placed between the faithful. |

| 26 | Leppä remarks: “The word ἄπιστος thus not seem here to refer to Gentiles but to Christians representing attitudes divergent from those of the writer” (Leppä 2005, p. 379). |

References

- Baker, Coleman A. 2012. Social Identity Theory and Biblical Interpretation. Biblical Theology Bulletin 42: 129–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Coleman A., and J. Brian Tucker. 2016. T&T Clark Handbook on Social Identity in the New Testament. London: T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Barentsen, Jack. 2011. Emerging Leadership in the Pauline Mission: A Social Identity Perspective on Local Leadership Development in Corinth and Ephesus. Princeton Theological Monograph Series 168; Eugene: Pickwick. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, Paul. 1997. The Second Epistle to the Corinthians. The New International Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, Carlin A. 2001. Roman Honor: The Fire in the Bones. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beale, Gregory K. 1989. The Old Testament Background of Reconciliation in 2 Corinthians 5–7 and Its Bearing on the Literary Problem of 2 Corinthians 6:14–7:1. New Testament Studies 35: 550–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, Hans Dieter. 1973. 2 Cor 6:14–7:1: An Anti-Pauline Fragment? Journal of Biblical Literature 92: 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieringer, Reimund, Emmanuel Nathan, and Dominika Kurek-Chomycz. 2008. 2 Corinthians: A Bibliography. Biblical Tools and Studies 5. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, George J. 2014. 2 Corinthians 6:14–7:1 Again: A Change in Perspective. In The Dead Sea Scrolls and Pauline Literature. Edited by Jean Rey. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chalcraft, David. 2019. Social Scientific Approaches: A. Sectarianism. In T&T Clark Companion to the Dead Sea Scrolls. Edited by George J. Brooke, M. DeVries, Charlotte Hempel and D. Longacre. T&T Clark Companions. London: T&T Clark, pp. 237–41. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Andrew D., and J. Brian Tucker. 2016. Social History and Social Theory in the Study of Social Identity. In T&T Clark Handbook on Social Identity in the New Testament. Edited by Coleman A. Baker and J. Brian Tucker. London: T&T Clark, pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Duff, Paul Brooks. 1993. The Mind of the Redactor: 2 Cor. 6:14–7:1 in Its Secondary Context. Novum Testamentum 35: 160–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J., and M. Derrett. 1978. 2 Cor 6:14: A Midrash on Dt 22:10. Biblica 59: 231–50. [Google Scholar]

- Esler, Philip F. 1994. The First Christians in Their Social Worlds: Social-Scientific Approaches to the New Testament Interpretation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Esler, Philip F. 1995. Modelling Early Christianity: Social-Scientific Studies of the New Testament in Its Context. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Esler, Philip F. 2000. Keeping It in the Family: Culture, Kinship and Identity in 1 Thessalonians and Galatians. In Families and Family Relations: As Represented in Early Judaisms and Early Christianities. Edited by Athalya Brenner and Jan Willem Van Henten. Studies in Theology and Religion 2. Leiden: Brill, pp. 145–84. [Google Scholar]

- Esler, Philip F. 2007. Prototypes, Antitypes and Social Identity in First Clement: Outlining a New Interpretative Model. Early Christian Identities, Annali di storia dell’esegesi I: 125–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fahnestock, Jeanne. 2011. Rhetorical Style: The Uses of Language in Persuasion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fee, Gordon D. 1977. II Corinthians 6:14–7:1 and Food Offered to Idols. New Testament Studies 23: 140–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fee, Gordon D. 2014. The First Epistle to the Corinthians. The New International Commentary on the New Testament 7. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Finney, Mark T. 2011. Honour and Conflict in the Ancient World: 1 Corinthians in Its Greco-Roman Social Setting. Library of New Testament Studies 460. London: T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, J. D., and H. C. Kelman. 2011. The Formation of Enemy and Self-Images. In Intergroup Conflicts and Their Resolution: A Social Psychological Perspective. Edited by Daniel Bar-Tal. Frontiers of Social Psychology. New York: Psychology Press, pp. 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Georgi, Dieter. 1986. The Opponents of Paul in Second Corinthians. Studies of the New Testament and Its World. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Gunther, John J. 1973. St. Paul’s Opponents and Their Background: A Study of Apocalyptic and Jewish Sectarian Teachings. Novum Testamentum Supplements 35. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, George H. 2015. 2 Corinthians. Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Hakola, Raimo. 2008. Social Identity and a Stereotype in the Making: The Pharisees as Hypocrites in Matt 23. In Identity Formation in the New Testament. Edited by B. Holmberg and M. Winninge. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 227. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 123–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, David R. 2003. The Unity of the Corinthian Correspondence. Journal for the Study of the New Testament Supplement Series 251; London: T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Murray J. 2005. The Second Epistle to the Corinthians: A Commentary on the Greek Text. The New International Greek Testament Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam, S. Alexander. 2004. Psychology in Organisations: The Social Identity Approach, 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Heil, Christoph. 1996. Die Sprache der Absonderung in 2 Kor 6,17 und bei Paulus. In The Corinthian Correspondence. Edited by R. Bieringer. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum theologicarum Lovaniensium 125. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 717–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, Charles. 1891. An Exposition of the Second Epistle to the Corinthians. New York: Armstrong & Son. [Google Scholar]

- Jokiranta, Jutta. 2010. Sociological Approaches to Qumran Sectarianism. In The Oxford Handbook of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Edited by John J. Collins and Timothy H. Lim. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 200–31. [Google Scholar]

- Keener, Craig S. 2005. 1–2 Corinthians. New Cambridge Bible Commentary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Verne R. 1971. Auxesis: A Concept of Rhetorical Amplification. Southern Journal of Communication 37: 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, Jacobus. 2014. Social Identity Complexity Theory as Heuristic Tool in New Testament Studies. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 70: 11–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuecker, Aaron. 2011. The Spirit and the ‘Other’: Social Identity, Ethnicity and Intergroup Reconciliation in Luke-Acts. The Library of New Testament Studies. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, T. J. 2018. Trouble with Insiders: The Social Profile of the Ἄπιστοι in Paul’s Corinthian Correspondence. Journal of Biblical Literature 137: 981–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lategan, B. C. 1984. Moenie met ongelowiges in dieselfde juk trek nie. Scriptura 12: 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Leppä, Outi. 2005. Believers and Unbelievers in 2 Corinthians 6:14,15. In Lux Humana, Lux Aeterna: Essays on Biblical and Related Themes in Honour of Lars Aejmelaeus. Edited by Antti Mustakallio, Heikki Leppä, Heikki Räisänen and Lars Aejmelaeus. Publications of the Finnish Exegetical Society 89. Helsinki: Finnish Exegetical Society, pp. 374–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lieu, Judith M. 2004. Christian Identity in the Jewish Graeco-Roman World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Kar Yong. 2020. 2 Corinthians. In T&T Clark Social Identity Commentary on the New Testament. Edited by J. Brian Tucker and Aaron Kuecker. London: T&T Clark, pp. 327–54. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Fredrick J. 2004. Ancient Rhetoric and Paul’s Apology: The Compositional Unity of 2 Corinthians. Society for New Testament Studies Monograph Series 131; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Fredrick J. 2016. The God of This Age (2. Cor. 4:4) and Paul’s Empire-Resisting Gospel at Corinth. In The First Urban Churches 2: Roman Corinth. Edited by James R. Harrison and L. L. Welborn. Writings from the Greco-Roman World Supplement Series 8; Atlanta: SBL Press, pp. 219–69. [Google Scholar]

- Malina, Bruce J. 1993. Windows on the World of Jesus: Time Travel to Ancient Judea. Time Travel Series; Westminster: John Knox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marquis, Timothy Luckritz. 2013. Transient Apostle: Paul, Travel, and the Rhetoric of Empire. Synkrisis: Comparative Approaches to Early Christianity in Greco-Roman Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Ralph P. 2014. 2 Corinthians. Word Biblical Commentary 40. Waco: Word Books. [Google Scholar]

- Minor, Mitzi. 2009. 2 Corinthians. Smyth & Helwys Bible Commentary 25b. Macon: Smyth & Helwys. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Teresa. 2015. Roman Faith and Christian Faith: Pistis and Fides in the Early Roman Empire and Early Churches. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muraoka, Takamitsu. 2009. A Greek-English Lexicon of the Septuagint. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan, Emmanuel. 2013. Fragmented Theology in 2 Corinthians: The Unsolved Puzzle of 6:14–7:1. In Theologizing in the Corinthian Conflict: Studies in the Exegesis and Theology of 2 Corinthians. Edited by Reimund Bieringer, Ma Marilou S. Ibita, Dominika Kurek-Chomycz and Thomas A. Vollmer. Biblical Tools and Studies 16. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 211–28. [Google Scholar]

- Neusner, Jacob. 1988. The Mishnah: A New Translation. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom, Carol A. 2007. Construction “We, You and the Others”. In Defining Identities: We, You, and the Other in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Edited by Florentino García Martínez and Mladen Popović. Leiden: Brill, pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, Michael. 1985. The Concept of Purity at Qumran and in the Letters of Paul. Society for New Testament Studies 53. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V. Henry T. 2008. Christian Identity in Corinth, 1st ed. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, Penelope J., S. Alexander Haslam, and John C. Turner. 1994. Stereotyping and Social Reality. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Omerzu, Heike. 2014. Exploring the Dynamic Relationship between Mission and Ethics in Luke-Acts. In Sensitivity towards Outsiders: Exploring the Dynamic Relationship between Mission and Ethics in the New Testament and in Early Christianity. Edited by Jacobus Kok, Tobias Nicklas, Dieter T. Roth and Christopher M Hays. WUNT 364. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 151–70. [Google Scholar]

- Oropeza, B. J. 2012. Jews, Gentiles, and the Opponents of Paul: The Pauline Letters. Apostasy in the New Testament Communities 2. Eugene: Cascade Books. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Roh Sik. 2010. The Background and Function of Pauline Temple Imagery in 2 Cor 6:14–7:1. 신약연구 9: 735–61. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Stanley E. 2005. Paul and His Opponents. Pauline Studies. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Rabens, Volker. 2014. Inclusion of and Demarcation from “Outsiders”: Mission and Ethics in Paul’s Second Letter to the Corinthians. In Sensitivity towards Outsiders: Exploring the Dynamic Relationship between Mission and Ethics in the New Testament and in Early Christianity. Edited by Jacobus Kok, Tobias Nicklas, Dieter T. Roth and Christopher M. Hays. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 364. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 290–323. [Google Scholar]

- Rensberger, David. 1978. 2 Corinthians 6: 14–7: 1- A Fresh Examination. Studia Biblica et Theologica 8: 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeller, Thomas. 2006. Der ursprüngliche Kontext von 2 Kor 6.14–7.1: Zur Frage der Einheitlichkeit des 2. Korintherbriefes. New Testament Studies 52: 219–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeller, Thomas. 2010. Der zweite Brief an die Korinther. Evangelisch-katholischer Kommentar zum Neuen Testament 8. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Theologie. [Google Scholar]

- Seifrid, Mark A. 2014. The Second Letter to the Corinthians. The Pillar New Testament Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Sierksma-Agteres, Suzan. 2023. Paul and the Philosophers’ Faith: Discourses of Pistis in the Graeco-Roman World. Ph.D. dissertation, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, January 12. [Google Scholar]

- Starling, David. 2013. The Άπιστοι of 2 Cor 6:14: Beyond the Impasse. Novum Testamentum 55: 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumney, Jerry L. 1990. Identifying Paul’s Opponents: The Question of Method in 2 Corinthians. Journal for the Study of the New Testament 40. Sheffield: JSOT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Nicholas H. 2005. Apostolic Identity and the Conflicts in Corinth and Galatia. In Paul and His Opponents. Edited by Stanley E. Porter. Pauline Studies. Leiden: Brill, pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Tellbe, Mikael. 2009. Christ-Believers in Ephesus: A Textual Analysis of Early Christian Identity Formation in a Local Perspective. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 242. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Thrall, Margaret E. 2004. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Second Epistle to the Corinthians. The International Critical Commentary on the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments 34. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Tomson, Peter J. 2014. Christ, Belial, and Women: 2 Cor 6:14–7:1 Compared with Ancient Judaism and with the Pauline Corpus. In Second Corinthians in the Perspective of Late Second Temple Judaism. Edited by Reimund Bieringer, Emmanuel Nathan, Didier Pollefeyt and Peter J. Tomson. Compendia Rerum Iudaicarum Ad Novum Testamentum 14. Leiden: Brill, pp. 79–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebilco, Paul R. 2014a. Creativity at the Boundary: Features of the Linguistic and Conceptual Construction of Outsiders in the Pauline Corpus. New Testament Studies, 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Trebilco, Paul R. 2014b. Self-Designations and Group Identity in the New Testament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trebilco, Paul R. 2017. Outsider Designations and Boundary Construction in the New Testament: Early Christian Communities and the Formation of Group Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, J. Brian, and Aaron Kuecker. 2020. T&T Clark Social Identity Commentary on the New Testament. Londen: T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Van Henten, Jan Willem, and Friedrich Avemarie. 2002. Martyrdom and Noble Death: Selected Texts from Graeco-Roman, Jewish, and Christian Antiquity. Context of Early Christianity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- van Spanje, Teunis Erik. 2009. 2 Korintiërs: Profiel van een evangeliedienaar. Commentaar op het Nieuwe Testament. Kampen: Kok. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, William O. 2002. 2 Corinthians 6.14–7.1 and the Chiastic Structure of 6.11–13; 7.2–3. New Testament Studies 48: 142–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, William J. 1992a. What Is the Unequal Yoke (Ἑτεροζυγοῦντες) in 2 Corinthians 6:14? Bibliotheca Sacra, June. 162–79. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, William J. 1992b. Who Are the Unbelievers (Ἀπίστοι) in 2 Corinthians 6:14. Bibliotheca Sacra, March. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, William J. 1993. Returning Home: New Covenant and Second Exodus as the Context for 2 Corinthians 6.14–7.1. Journal for the Study of the New Testament 85. Sheffield: JSOT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Welborn, Laurence L. 2011. An End to Enmity: Paul and the ‘Wrongdoer’ of Second Corinthians. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der älteren Kirche 185. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Wendland, Heinz-Dietrich. 1980. Die Briefe an die Korinther. 15. Aufl. Das Neue Testament Deutsch, neues Göttinger Bibelwerk 7. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, Bruce W. 2001. After Paul Left Corinth: The Influence of Secular Ethics and Social Change. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Appeldoorn, G.v. Group Formative Processes in 2 Cor 6:14–7:1. Religions 2024, 15, 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050538

Appeldoorn Gv. Group Formative Processes in 2 Cor 6:14–7:1. Religions. 2024; 15(5):538. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050538

Chicago/Turabian StyleAppeldoorn, Gijsbert van. 2024. "Group Formative Processes in 2 Cor 6:14–7:1" Religions 15, no. 5: 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050538

APA StyleAppeldoorn, G. v. (2024). Group Formative Processes in 2 Cor 6:14–7:1. Religions, 15(5), 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050538