Spiritual Influences on Jewish Modern Orthodox Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Definition of Terms

1.2. General Religious Scales Are Limited

1.3. Jewish Religious Scales Are Limited

1.4. JewBALE Scale and Modern Orthodox Adolescents

1.5. Current Study

1.5.1. Gender

1.5.2. Self-Esteem

1.5.3. Religious Homogeny with Parents

1.5.4. Spiritual Struggle

2. Results

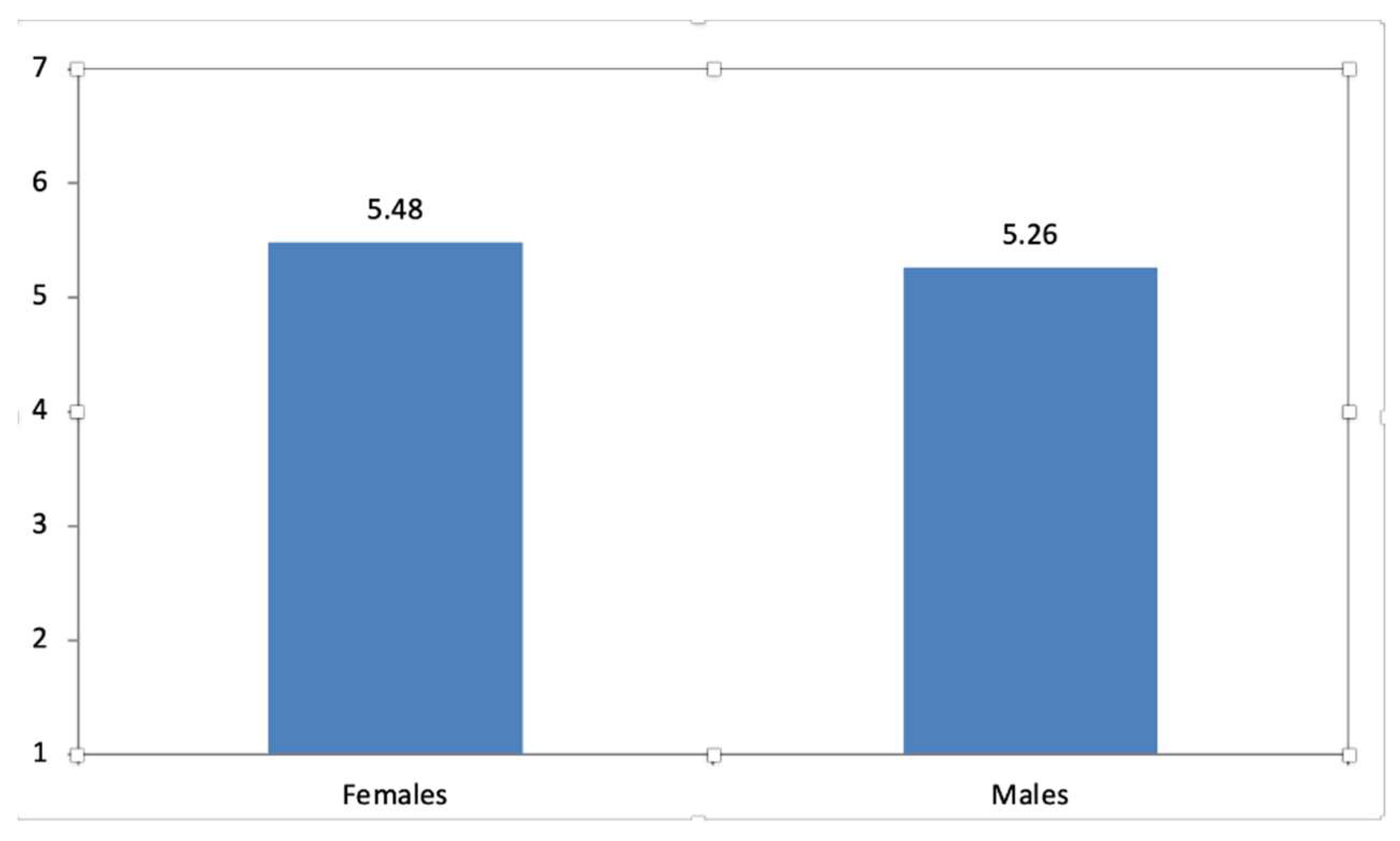

2.1. Gender

2.2. Self-Esteem

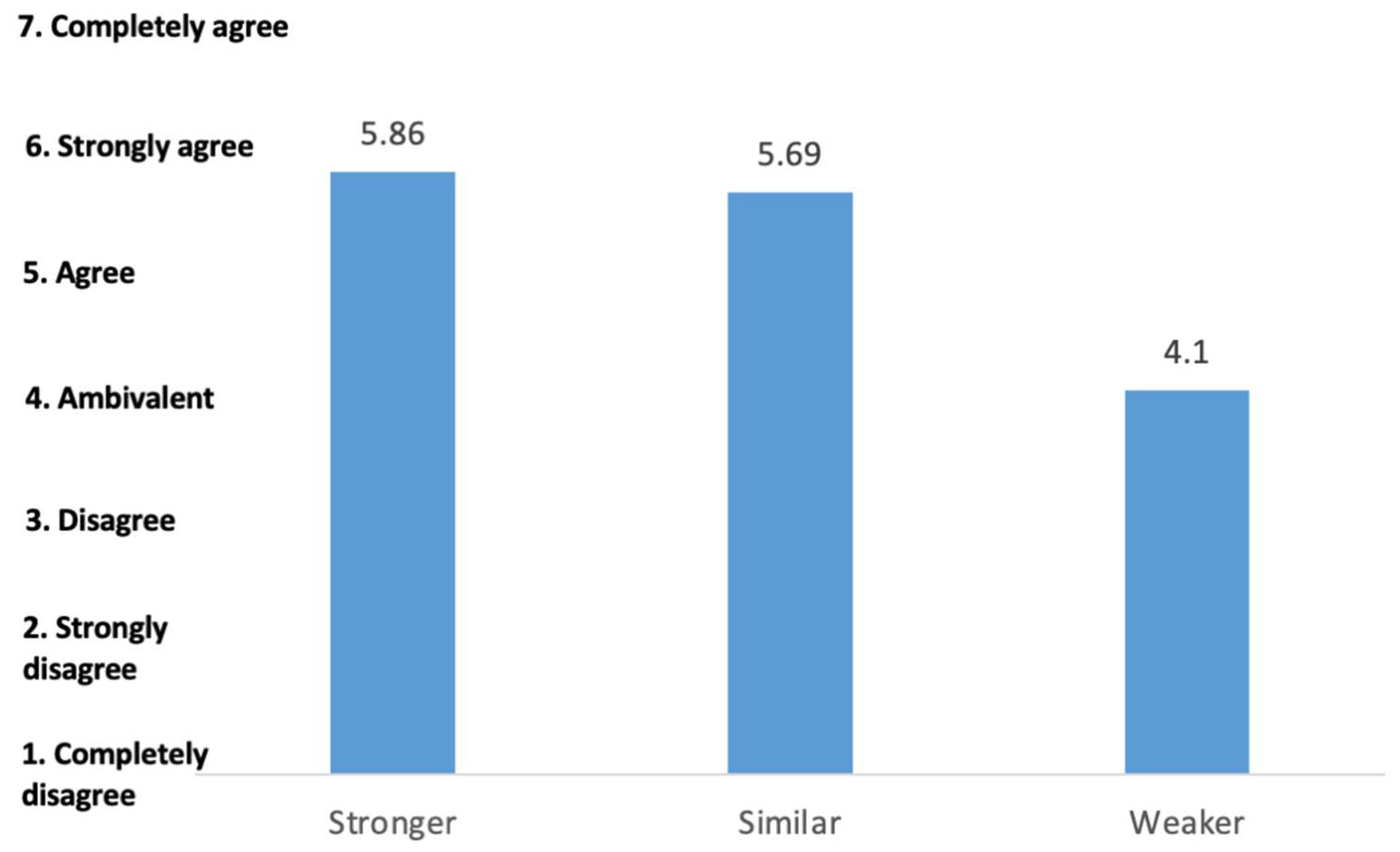

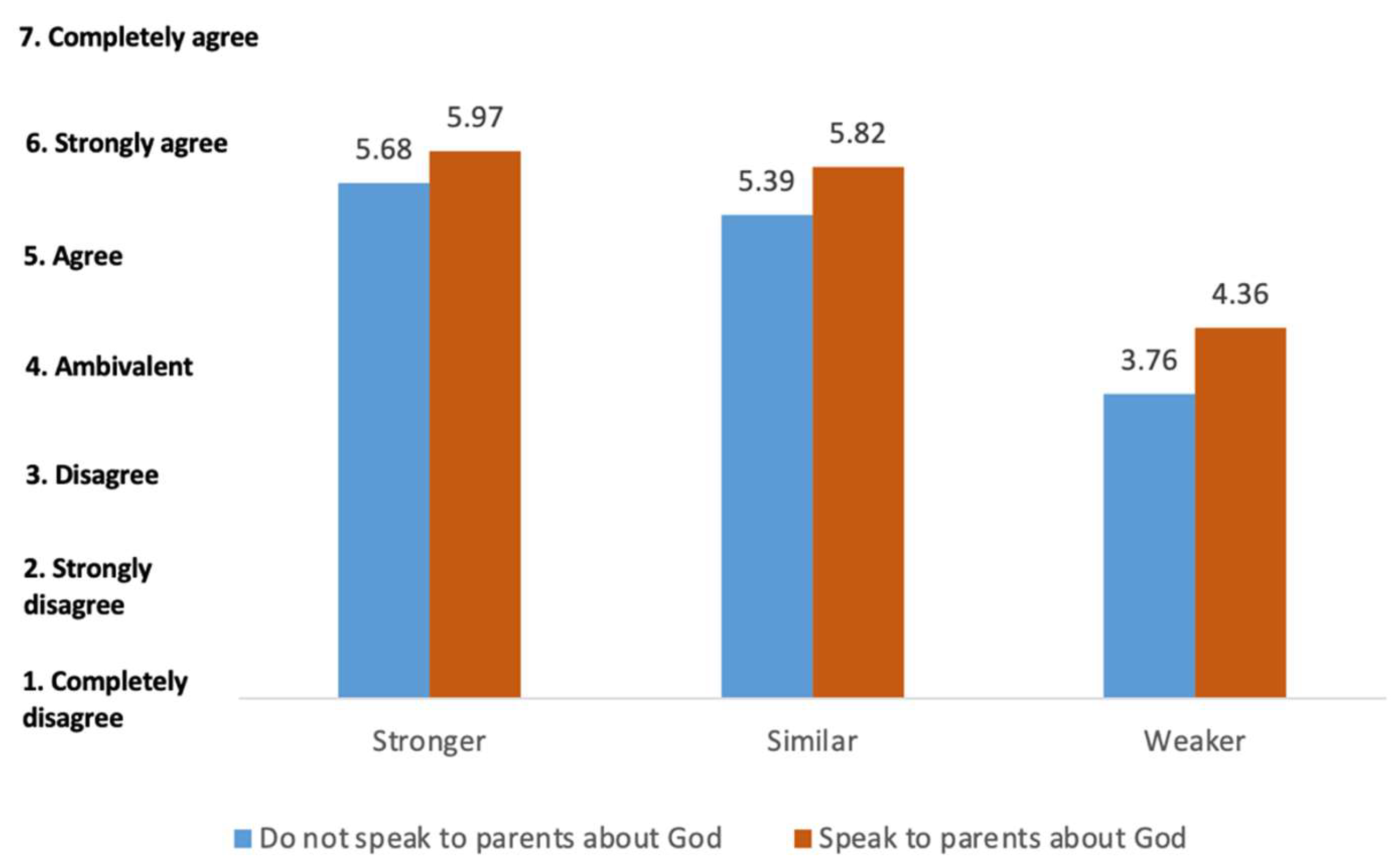

2.3. Homogeny with Parents

2.4. Spiritual Struggle

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Gender and Spirituality

4.2. Self-Esteem and Spirituality

4.3. Religious Homogeny with Parents and Spirituality

4.4. Jewish Struggle and Spirituality

5. Conclusions and Future Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Divine Providence with Relation to the World (5 items)

- Divine Providence with Relation to the Individual (4 items)

- Fear/Love/Awe of God (6 items)

- Joyful/Meaningful Life (4 items)

- Rabbinic Authority (4 items)

- Divinity/Truth of Torah (3 items)

- Relationship to Israel (4 items)

- Outlook on Secular Studies (3 items)

- General: name, grade, age, school, location, camp

- Family: background, relationship with

- School: relationship with teachers, connection to learning, grades

- Self-concept

- Technology: use of, bullying

- Aspiration to be Jewish communal leader

- Future Plans (2 items)

- Women (5 items)

- Sexuality and Family Values (4 items)

- Western Values (3 items)

- Judgment (1 item)

- Social Media (2 items)

- Influences (6 items)

- Growth Mindset (4 items)

Appendix B

- Physical Health

- Mental Health

- Social Health

- General Health

- Self-esteem

Appendix C

Appendix C.1. Sample Items of the Scales Referenced to in This Study

- It is important to find a rabbi (or group of rabbis) who will serve as my posek (a person who decides halakha for me).

- A rabbi should be consulted when you have important life decisions to make.

- I decide which religious practices to follow based on what makes sense to me.

- I respect the process that Rabbis engage in to decide halakha for their

- community.

- Women may earn Orthodox rabbinic ordination.

- Women may serve as a president of a shul (synagogue)

- Women may serve as clergy of a shul. (Clergy refers to a member of the

- Professional leadership of a shul who performs religious duties.)

- Women may lead tefilla (communal prayers)

- Women may read Torah publicly for a tzibur (community prayer service).

Appendix C.2. Definition of Terms

- Spirituality—internalization of beliefs.

- Religiosity—practice of religious actions.

- Religiousness/Religious commitment—adherence to religion in general, referring to both religious beliefs and actions.

- Socio-Religiousness/Jewish struggle—personal beliefs in contrast to conventional

- Norms in many Orthodox communities, such as the participation of women and homosexual couples in synagogues, acceptance of drug use, and acceptance of physical contact between sexes.

- Religious Homogeny—having similar religious beliefs to another.

References

- Allen, G. E. Kawika, Kenneth T. Wang, and Hannah Stokes. 2015. Examining legalism, scrupulosity, family perfectionism, and psychological adjustment among LDS individuals. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 18: 246–58. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, Scott A., and John P. Hoffmann. 2002. The dynamics of self- esteem: A growth curve analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 31: 101–3. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, Joanna, Lisa Armistead, and Barbara-Jeanne Austin. 2003. The relationship between religiosity and adjustment among African-American, female, urban adolescents. Journal of Adolescence 26: 431–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batson, Charles Daniel, Patricia Schoenrade, and W. Larry Ventis. 1993. Religion and the Individual. New York: Oxford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Meir, Yehuda, and Peri Kedem. 1979. Religiousness measure for the Jewish population in Israel. Megamot 24: 353–62. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, Peter L., Eugene C. Roehlkepartain, and Stacey P. Rude. 2003. Spiritual development in childhood and adolescence: Toward a field of inquiry. Applied Developmental Science 7: 205–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyerlein, Kraig. 2004. Specifying the impact of conservative Protestantism on educational attainment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 43: 505–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, R. 2012. Gender Differences in the Spiritual Development of Adolescent Students Attending Modern Orthodox Jewish High Schools through the Lens of Prayer. New York: Yeshiva University. [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnason, Dana. 2007. Concept Analysis of Religiosity. Home Health Care Management and Practice 19: 350–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricheno, Patricia, and Mary Thornton. 2007. Role model, hero or champion? Children’s views concerning role models. Educational Research 49: 383–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, Bruce A., Brent L. Top, and Richard J. McClendon. 2010. Shield of Faith: The Power of Religion in the Lives of LDS Youth and Young Adults. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, pp. 161–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chagas, Camila, Leonardo Breno Martins, Fatima Regina Machado, Welligton Zangari, and José Carlos Fernandes Galduróz. 2023. Religious and secular spirituality: Methodological implications of definitions for health research. EXPLORE 19: 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Charmé, Stuart Z. 2006. The gender question and the study of Jewish children. Religious Education 101: 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Charytan, Margaret. 1997. The Impact of Religious Day School Education on Modern Orthodox Judaism: A Study of Changes in Seven Modern Orthodox Day Schools and the Impact on Religious Transmission to Students and Their Families. New York: City University of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Adam B., and Paul Rozin. 2001. Religion and the morality of mentality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81: 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Malayev, Maya, Elli P. Schachter, and Yisrael Rich. 2014. Teachers and the religious socialization of adolescents: Facilitation of meaningful religious identity formation processes. Journal of Adolescence 37: 205–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Don-Yehiya, Eliezer. 2005. Orthodox Jewry in Israel and in North America. Israel Studies 10: 157–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, Steven. 2010. Spiritual and Religious Mentoring: The Role of Rabbis and Teachers as Social Supporters Amongst Jewish Modern Orthodox High School Graduates Spending a Year of Study in Israel. Doctoral dissertation, Azrieli Graduate School, Yeshiva University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Christopher G., Jason D. Boardman, David R. Williams, and James S. Jackson. 2001. Religious involvement, stress, and mental health: Findings from the 1995 Detroit Area Study. Social Forces 80: 215–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiala, William E., Jeffrey P. Bjorck, and Richard Gorsuch. 2002. The religious support scale: Construction, validation, and cross-validation. American Journal of Community Psychology 30: 761–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fischer, Kurt W., and Ellen Pruyne. 2003. Reflective thinking in adulthood: Emergence, development, and variation. In Handbook of Adult Development. Boston: Springer, pp. 169–98. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, Leslie J., and Chris J. Jackson. 2003. Eysenck’s dimensional model of personality and religion: Are religious people more neurotic? Mental Health, Religion & Culture 6: 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Scott J. 2006. Jewish Beliefs Actions and Living Evaluation (JewBALE), Unpublished manuscript. New York: Yeshiva University, Azrieli Graduate School.

- Goldberg, Scott J. 2018. Jewish Beliefs Actions and Living Evaluation 2.0 (JewBALE 2.0), Unpublished manuscript. New York: Yeshiva University, Azrieli Graduate School.

- Goldmintz, Jay. 2011. Religious Development in Adolescence: A Work in Progress. Azrieli Papers: Dimensions in Orthodox Day School Education. Edited by David J. Schnall and Moshe Sokolow. New York: Yeshiva University Press, pp. 149–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch, Richard L. 1990. Measurement in psychology of religion revisited. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 9: 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Paul L. 2012. Trusting What You’re Told: How Children Learn from Others. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heaven, Patrick C. L., and Joseph Ciarrochi. 2007. Religious values, personality, and the social and emotional well-being of adolescents. British Journal of Psychology 98: 681–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, Ralph W., Jr., Peter C. Hill, and Bernard Spilka. 2009. The Psychology of Religion: An Empirical Approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hunsberger, Bruce, Barbara McKenzie, Michael Pratt, and S. Mark Pancer. 1993. Religious doubt: A social psychological analysis. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion 5: 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hunsberger, Bruce, Michael Pratt, and S. Mark Pancer. 2002. A longitudinal study of religious doubts in high school and beyond: Relationships, stability, and searching for answers. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 255–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, John E., and Frank L. Schmidt. 1990. Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings. Newbury Park: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Yaacov J., and Mirjam Schmida. 1992. Validation of the student religiosity questionnaire. Educational and Psychological Measurement 52: 353–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G., Michael E. McCullough, and David B. Larson. 2001. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmin, Barry, and Ariela Keisar. 2000. “Four Up”: The High School Years, 1995–1999. New York: Ratner Center for the Study of Conservative Judaism, Jewish Theological Seminary. [Google Scholar]

- London, Perry, and Barry Chazan. 1990. Psychology and Jewish Identity Education. New York: American Jewish Committee. [Google Scholar]

- Luce, Megan R., Maureen A. Callanan, and Sarah Smilovic. 2013. Links between parents’ epistemological stance and children’s evidence talk. Developmental Psychology 49: 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKune, Benjamin, and John P. Hoffmann. 2009. Religion and academic achievement among adolescents. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion 5: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, Scott. 1996. An Interactive Model of Religiosity Inheritance: The Importance of Family Context. American Sociological Review 61: 858–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelsen, Hart M., and Raymond H. Potvin. 1981. Gender and regional differences in the religiosity of Protestant adolescents. Review of Religious Research 22: 268–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishma Research. 2017. The Nishma Research Profile of American Modern Orthodox Jews. Available online: http://nishmaresearch.com/assets/pdf/Report%20-%20Nishma%20Research%20Profile%20of%20American%20Modern%20Orthodox%20Jews%2009-27-17.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Prager, Dennis, and Joseph Telushkin. 1981. Nine Questions People Ask about Judaism. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, Yisrael, and Elli P. Schachter. 2012. High school identity climate and student identity development. Contemporary Educational Psychology 37: 218–28. [Google Scholar]

- Samson, Maxim G., Robert M. Vanderbeck, and Nichola Wood. 2018. Fixity and flux: A critique of competing approaches to researching contemporary Jewish identities. Social Compass 65: 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, Constantine, and Jochen E. Gebauer. 2010. Religiosity as self-enhancement: A meta-analysis of the relation between socially desirable responding and religiosity. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sloane, Douglas M., and Raymond H. Potvin. 1983. Age differences in adolescent religiousness. Review of Religious Research 25: 142–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Christian, Robert Faris, Melinda Lundquist Denton, and Mark D. Regnerus. 2003. Mapping American adolescent subjective religiosity and attitudes of alienation toward religion: A research report. Sociology of Religion 64: 111–33. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Rodney. 2002. Physiology and faith: Addressing the “universal” gender difference in religious commitment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 495–507. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Suzanne, and A. Jordan Wright. 2018. Discrete effects of religiosity and spirituality on gay identity and self-esteem. Journal of Homosexuality 65: 1071–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sullins, D. Paul. 2006. Gender and religion: Deconstructing universality, constructing complexity. American Journal of Sociology 112: 838–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, Chana G. 2009. Gender Differences in the Perceived Religious Influence of Yeshiva Programs. New York: Yeshiva University. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenbaum, Harriet R., and Jill M. Hohenstein. 2016. Parent–child talk about the origins of living things. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 150: 314–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Kenneth T., G. E. Kawika Allen, Hannah I. Stokes, and Han Na Suh. 2018. Perceived perfectionism from God scale: Development and initial evidence. Journal of Religion and Health 57: 2207–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, Emyr, Leslie J. Francis, and Mandy Robbins. 2006. Rejection of Christianity and self-esteem. North American Journal Of Psychology 8: 193–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zelkowicz, Tali E. 2013. Beyond a Humpty-Dumpty narrative: In search of new rhymes and reasons in the research of contemporary American Jewish identity formation. International Journal of Jewish Education Research 2013: 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer, Brian J., and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2005. Religiousness and spirituality. Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 54: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

| Subscale | Gender | Mean | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Divine Providence with Relation to the World ** | Male | 5.58 | 1.57 | 394 |

| Divine Providence with Relation to the World ** | Female | 5.88 | 1.19 | 586 |

| Divine Providence with Relation to the Individual * | Male | 5.44 | 1.66 | 394 |

| Divine Providence with Relation to the Individual * | Female | 5.75 | 1.28 | 583 |

| Fear/Love/Awe of God * | Male | 5.10 | 1.52 | 395 |

| Fear/Love/Awe of God * | Female | 5.34 | 1.24 | 584 |

| Joyful/Meaningful Life ** | Male | 5.33 | 1.20 | 394 |

| Joyful/Meaningful Life ** | Female | 5.62 | 1.03 | 583 |

| Rabbinic Authority | Male | 4.60 | 1.35 | 392 |

| Rabbinic Authority | Female | 4.62 | 1.24 | 584 |

| Divinity/Truth of Torah | Male | 5.47 | 1.59 | 392 |

| Divinity/Truth of Torah | Female | 5.60 | 1.29 | 583 |

| Relationship to Israel ** | Male | 5.26 | 1.23 | 390 |

| Relationship to Israel ** | Female | 5.54 | 1.03 | 582 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weinstein, S.E.; Goldberg, S.J. Spiritual Influences on Jewish Modern Orthodox Adolescents. Religions 2024, 15, 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040509

Weinstein SE, Goldberg SJ. Spiritual Influences on Jewish Modern Orthodox Adolescents. Religions. 2024; 15(4):509. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040509

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeinstein, Sharon Elsant, and Scott J. Goldberg. 2024. "Spiritual Influences on Jewish Modern Orthodox Adolescents" Religions 15, no. 4: 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040509

APA StyleWeinstein, S. E., & Goldberg, S. J. (2024). Spiritual Influences on Jewish Modern Orthodox Adolescents. Religions, 15(4), 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040509