1. Introduction

“When Catholics leave the church they do so by the south door, into the glare of the market-place, where their eye is at once attracted … by the fountain with its baroque Tritons blowing the spray into the air, and the children laughing and playing round it”. “Protestants, on the contrary, leave the church by the north door, into the damp solitude of a green churchyard, amid yews and weeping willows and overgrown mounds and fallen illegible gravestones”.

George Santayana, Leaving Church. Soliloquies in England, 1914–1918.

From its origins, the history of Western Christian art has been a difficult paradox to learn how to represent the invisible through the visible. It has always been a technical challenge, but it is conceptual. The fact that, according to Christianity and the Catholic faith, the eternal Word of the Father became visible through the incarnation of the Son in the Holy Spirit has raised the difficulty of the cult of images and their legitimacy. How do we represent the invisible God, which the Jewish religion had forbidden, which is an act of idolatry in Islam and has been questioned during the Reformation? (

Finney 1997;

King 1985;

Crone 2017).

However, this same art history shows that the symbolic representation of faith and the Gospel narrative has been possible, and not only possible but brilliant (

Gustafsson 2012). Brunelleschi’s discovery of geometric perspective in 1435 turned our symbolic way of looking upside down, transforming the representation space into a new place for a scientific gaze (

Kemp 1990). From the moment artistic expression imitates the workings of the human eye, Christian art gains precision but loses suspense. In the work of the Italian Quattrocento painters, sculptors, and architects, there is room for surprise, admiration, and knowledge. Still, there is no more extended room for the mystery of the unexpected. In this sense, the arts of the Middle Ages can be considered, in their symbolism of the unknown, as arts in which there is no choice but to suspend judgment (

Camille 1992). In this way, it is worthwhile to consider the notion of Chaosmos in the work of Umberto Eco, considered as the tension between cosmos and chaos, order and disorder, “a radical opposition between the medieval man, nostalgic for an ordered world of clear signs, and the modern man, seeking a new habitat but unable to find the elusive rules and thus burning continually in the nostalgia of a lost infancy”. (

Eco 1962,

1989).

The two-dimensionality of Romanesque frescoes, the chromatic atmosphere of cathedrals, and the chiaroscuro of Gothic sculpture refer to a relationship between sacred space and artistic representation that has remained unresolved (

Panofsky 1966, I, p. 236). It is up to the public to continue, with their act of faith, the various narratives that challenge them: the cycle of Jonah, Daniel in the lions’ den, the three young men in the furnace, Susanna and the elders, but also the life of Christ, his miracles, and especially his passion, death, and resurrection.

From the paintings of the catacombs of the first Christian art to the Flemish primitives, through the wonders of the vernacular art of the invading peoples, the European Romanesque and the international Gothic, there has been a serious attempt to educate the gaze and to found a culture that, unlike that of the East, is ocularcentric by definition (

Brook 2002). While hearing, smell, and taste have predominated in the East, the human eye and touch have taken the leading role in the arts in the West. The word, a fundamental vehicle of the Christian faith, poses a relational universe between God and the believer and between the community elements that believe in the bosom of a universal Church. However, this word has crystallized in the West, with greater visual force in medieval European art (

Jensen 2011).

1The invention of photography and the cinematograph have much to do with this Western ocularcentrism with Christian roots because they managed to mechanize the gaze by imprinting the lights and shadows of the actual celluloid impregnated with a metallic sensitive to light emulsion (

Rowe 2011). With the imitative possibilities of photography and cinema, the challenge of representing reality artistically would no longer be of interest (

Jay 1995). However, these new visual and auditive media (including sound cinema and TV) have increased the possibility of representing the mystery, not only of the divine but also of the human. The reason is simple: both photography and cinema have realism, but by framing reality in a kind of new Albertian window (

Grøtta 2015, pp. 54–58), they can manipulate it with new means that hide more than the things they show, that are capable of creating atmospheres and that, above all, can work with technical devices that empower the Western aesthetics dominion of the eye (

Ihde 2008, p. 386).

For the first time, photography and cinema credibly guide the viewer’s gaze without renouncing the sacral-symbolic culture of the medieval masters. The powerful spotlight projected on the cinema screen can thus be seen as the powerful rays of the sun rising from the East to filter through the central apse of the Romanesque and Gothic churches, symbolizing Christ-light and revealing the colors of the mural painting and the forests of columns inside the temple, from dawn to dusk. It can also be said that before the appearance of electric light, the medieval temple functioned as an ancient camera obscura that projected the mysteries of that invisible God and filled the space with antique suspense (

Hamilton and Spicer 2005).

These prolegomena are essential to understanding Alfred Hitchcock’s visual tradition and the sacred aftertaste of some of his best suspense scenes. On the one hand, he was visually educated in three fundamental traditions. First, Aristotle’s Poetics and Rhetoric which taught him how the structure of every act of communication works in an ascending manner, reaching a climax and then descending emotionally to end the story. Greek tragedy and the unity between space and time, or its rupture through montage, are part of his visual imagination (

Ertuna-Howison 2013). Secondly, his filmography is a way of seeing Christianity from a double point of view. The moralizing aspect that he learned in the Victorian society where he was born and the Jesuitism school provided him with a comprehensive culture and, at the same time, a strong sense of manipulation of reality (

Fyne 1995). Third, the twofold cinematic language, including Eisenstein’s idea of montage (

Belton 1980) and the handling of light in the German expressionist cinema of the 1920s (

Clark 2004, p. 40ff).

Since suspense is not only a formal filmic device but essentially an epistemological strategy that was born in the Modern period, Immanuel Kant, René Descartes, Montaigne’s, and Sigmund Freud’s works are relevant to understand it as, respectively, “a judgment suspension in the human mind” (1), a “hesitation state” in human decisions (2), “the narrative interstice” between trial and error in an essay (3), and ultimately the “Freudian uncertainty” of the sub-conscient’s invisible world (4).

This is how to explain that the philosophical idea of suspense is intrinsically derived from the Kantian notion of suspension of judgment (

Guyer 2003),

2 Descartes’ methodical doubt (

Blackwell 2010) as a manipulation of the audience in terms of argumentative bewilderment, and in Montaigne’s essays, the ambiguity (

Starobinski 1985, p. 70) and narrative fluidity of Hitchcock’s style, or, finally, Freud’s influence on the explicitness of the subconscious in his films (

Sandis 2009). These are important, but, as it were, less atavistic and more conscious or deliberate elements of Hitchcock’s discourse than his Catholic-educated perception. “I don’t think I can be labeled a Catholic artist”, Hitchcock told François Truffaut, “but it may be that one’s early upbringing influences a man’s life and guides his instinct” (

Alleva 2010, p. 14;

Forrest 2010).

He did not disclose publicly the importance of Catholicism in his adult life. He was a parishioner of the Church of the Good Shepherd in Beverly Hills, where he attended Mass with his wife, Alma Reville, who was converted before their marriage in 1926. He was reluctant to discuss his cinema in terms other than cinematic terms. To assess the Catholic outlook that French critics saw as shaping his work, one has to look at the evidence of the films. Some of those pieces of evidence will be presented to the reader in this text. When Truffaut asked Hitchcock if he considered himself a Catholic artist, the filmmaker was not so elusive as cryptic. “I am definitely not antireligious; perhaps I’m sometimes neglectful”. (

Truffaut 1984, pp. 316–17;

De las Carreras Kuntz 2002, p. 122). Hitchcock did not make “very Catholic films” as this topic was considered by (

André Bazin 2002, p. 10).

The hypothesis I want to put forward in these pages is that I find a solid visual analogy between some of the tensest moments in Hitchcock’s films and some passages of Christian tradition to which they refer. My argument, taken to the extreme, could be stated by asking to what extent the passion and death of the Christian God-made-man, as narrated in the Gospels, could be considered a perfect crime with all its elements (as in the Greek tragedy: plot, character, diction, thought, spectacle, and song),

3 especially that of the suspension of judgment. In the end, “Transcendental expression in religion and art attempts to bring man as close to the ineffable, invisible, and unknowable as words, images, and ideas can take him” (

Schrader 2018, p. 39;

Salis 2021).

This suspension of judgment is related to a way of understanding deliberately ambiguous space. The scenic space of Hitchcock’s cinema always appears unfinished, with unexpected omissions, with closed rooms that push the imagination but never open. This incompleteness of space opens the field to a visual analogy between the sacred and the profane. Avant-garde architecture, with its closed right angles and open secularism, has already demonstrated its potential as a machine for living, a city designed for the automobile, or a notion of rationalism closed to further speculation. Rarely were masters like Mies van der Rohe or Le Corbusier, in their first period, in their search for universality (

Padovan 2013) able to confront the sacred space and solve it brilliantly. Nor did they manage to make the house or the city a space of suspense: everything is known in this shoe box architecture.

4 Hitchcock somehow connects the suspense of the cathedrals with the mystery of postmodern architecture. Thus, naturally, analogically, it is possible to analyze the relationship between the Christian culture that underlies his cinema, without him intending it, with the brilliant aesthetics of spatial suspense.

More sensibly, but no less realistically, this hypothesis can be inverted as follows: Which sequences or frames from Hitchcock’s filmography can be chosen as if, consciously or unconsciously, the director was filtering the dramatic facts of the murder of Christ in certain critical moments of his best thrillers? In Rope, is it possible to visually compare the introduction of the corpse of the unfortunate David into the chest with the burial of Jesus in the tomb at the hands of Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea? Or, in Psycho, might there be some inverted parallelism between the iconography of Pietà and the corpse of Marion Crane in the arms of Norman Bates, who is about to introduce her into the trunk of her car to be buried forever in the swamp?

These questions may seem strange to the reader, even from a methodological point of view. Still, the basis of this logic is none other than the notion of analogical thought that Michel Foucault finds in medieval authors such as Thomas Aquinas, Nicholas of Cusa, other modern ones such as Giordano Bruno or Emanuele Tesauro, to which we can add contemporaries such as James Joyce or Umberto Eco himself. It is not a question here of restricting the concept of space to its physical dimension alone but of extending it to the existential experience of the place. It is a matter of admitting that the cinema of the master of suspense is inscribed in the experience of a mental geography where cinema, architecture, arts, music, and thought meet.

This methodological hypothesis will presuppose that paradoxical thought made one of its first appearances in the Renaissance since its rejection of a rational way of understanding God demands a theology of human intuition. This mystical leap goes beyond the explanation of cause and effect (

Farronato 2003, p. 21). In other words, it is not that there will be a causal relationship between Hitchcock’s stills and the (Christian) medieval iconography of the passion and death of Christ, but it is possible to establish an intuitive connection between the two that allows us to conceive suspense as a sacred if not religious, sense of space and place.

Following Barbara M. Stafford, analogy’s proportional and participatory varieties are inherently visual. This requires perspicacity to see what adjustments must be made between uneven cases to achieve a tentative harmony. It also presupposes discernment to discover the relevant likeness in unlike things. In analogy, the resemblance is a matter of mimesis and clothing rather than veiling ideas. Since analogy and allegory are about dichotomous structures and involve binary logic, they are not easy to keep apart. At a deep level, they are the obverse and the reverse of the same coin, upholding and destroying conjunctions.

Analogy is the vision of ordered relationships articulated as similarity-in-difference. It correlates originality with continuity, what comes after what went before, ensuing parts with the evolving whole. This transport of predicates involves mutually sharing certain determinable quantitative and qualitative attributes through a

mediating image. The issue of perceptually blending or distinguishing people, objects, or ideas gets the specific visual component of analogy. At a deep level, the inherent mimetism of the method constituted its most fundamental problem, provoking intense iconoclastic or iconophilic reactions (

Stafford 2001, pp. 3, 23, 77, 109).

Other authors would agree. In 1981, the American theologian and priest David Tracy published

The Analogical Imagination, which distinguished between two master modes of religious interpretation throughout the history of Christianity: the “analogical” and the “dialectical” languages. In his work, the

analogical imagination (which emphasizes manifestation) sees, seeks, and expresses similarity-in-difference (

Tracy 1981, pp. 413–16;

Shafer 1996, p. 1515), which was not as a dead univocity but the genuine grace of emergent—and hence uncertain—possibility: the “radical mystery empowering all intelligibility”. The

dialectical imagination (which emphasizes proclamation) sees, seeks, and expresses difference-in-similarity; it is rooted in the experience of “prophetic suspicion”, the word of Jesus Christ as “disclosing the reality of the infinite, qualitative distinction between that God and this flawed, guilty, sinful, presumptuous, self-justifying self”. The dialectical imagination denies “all claims to similarity, continuity, ordered relations”. (

Tracy 1981, p. 408).

For this author, the Catholic imagination is “analogical”, and the Protestant is “dialectical”. The Catholic “classics” assume a God present in the world, disclosing himself in and through creation. The world and all its events, objects, and people tend to be somewhat like God. The Protestant classics, on the other hand, assume a God who is radically absent from the world and who discloses himself only on rare occasions (especially in Jesus Christ and Him Crucified). The world and all its events, objects, and people tend to be radically different from God (

Greeley 1989). Andrew Greeley wrote in 1989 that “The Catholic ethic is “communitarian” and the Protestant “individualistic”. (…) Catholics and Protestants “see” the world differently (or “saw” it differently)”. For him, “These preconscious “worldviews” are not totally different, but only somewhat different, different enough to produce different doctrinal and ethical codes, different church structures, and different behavior rates” (

Greeley 1989, p. 486).

Ingrid H. Shafer wrote that “the interplay of these two modes of seeing constitutes the cultural matrix of the West”. Georges Santayana also expressed something similar in interesting terms: “When Catholics leave the church, they do so by the south door”. Protestants, conversely, “leave the church by the north door”. (

Santayana 1931, p. 33;

Shafer 1996, p. 1516). Analogical imagination invites us to leave the church “by the south door” to see God as a friend in response to democratic models of human relationships and evolutionary models of ongoing creation.

Alfred Hitchcock, we postulate, had an “analogical imagination”. He is a Catholic, but his cinema is not “catholic;” he is not a Protestant, but his cinema is “Christian”. Hitchcock uses “Catholic strategies” for his movies, like communion (social sense), mediation (we need someone to resolve our conflicts), and sacramentality (to see God in material things) (

De las Carreras Kuntz 2002). Still, he offers more indeed: sublimity, guilt, disappointment, and many other mechanisms that, not being typically Catholic, they can answer to our questions.

Typically Jesuit in spirit, Hitchcock constantly challenges the boundaries of faith from the frontier, pointing beyond but never moving his feet outside Roman Catholic orthodoxy. He knows the human creature’s baser instincts and the Victorian world’s rigidity; he also knows how to dive into the subconscious. He has an “analogical imagination” but manages the tension with the “dialectical imagination”. In this text, we can explore the relationship between suspense and Christian culture from the point of view of the visual analogies it raises between miracles and heresy. Let us see how far these concepts can take us and what kind of feasibility they offer.

2. Psycho and the Holy Shroud

One of the most fascinating objects of the Christian Occident is the Shroud of Turin, a length of linen cloth that bears a faint image of the front and back of a tortured-to-death man. It has been revered for centuries, especially by members of the Catholic Church, as the actual burial shroud used to wrap the body of Jesus of Nazareth after his crucifixion, and upon which Jesus’s bodily image is miraculously imprinted at the very moment of his resurrection. It is not about its history or authenticity but its symbolism, considered a sort of Fifth Gospel of the Christian revelation (

Meacham et al. 1983).

The Gospels of Matthew (27:59–60), Mark (15:46), and Luke (23:53) state that Joseph of Arimathea wrapped the body of Jesus in a piece of linen cloth and placed it in a new tomb. The Gospel of John says he used strips of linen (19:38–40). After the resurrection, John (20:6–7) states: “Simon Peter came behind him and went straight into the tomb. He saw the strips of linen lying there and the cloth wrapped around Jesus’ head. The cloth was still in its place, separate from the linen”. Luke (24:12) states: “Peter, however, got up and ran to the tomb. Bending over, he saw the strips of linen lying by themselves”.

There is no need to believe in the historical authenticity of this visual document, even though the iconographic tradition of Christianity has taken it up on countless occasions. What is of interest here is what has remained in Alfred Hitchcock’s retina about this well-known story. Specifically, the scene in Psycho in which Norman Bates, after the murder of Marion Cane at the hands of Mrs. Bates (another personality), picks up Marion’s corpse and wraps it in a sheet (the shower curtain of the number one at the Bates Motel).

The scene is a long take in which Norman has come down from his mother’s house to clean the blood from the walls and remove all traces of the murder committed under the persona of his mother. Christian tradition refers to three pieces of cloth: the image of Christ’s face legendary imprinted on Veronica’s towel; the Holy Shroud of Turin, in which he was wrapped and his body miraculously imprinted on it; and The Sudarium (from Latin, “sweat cloth”) of Oviedo, a bloodstained piece kept in the Cámara Santa of the Cathedral of San Salvador, which does not show any image (

Fernández Sánchez 2010).

Two interesting Hitchcock images refer, by visual analogy, to such type of iconographies, and they are successive frames of the scene in which Norman is in charge of burying Marion’s body in the coffin of his automobile, destined for the swamp on the Bates’ estate. First, the mandylion (from Greek μανδύλιον “cloth, towel”) of Veronica, a woman who, in the middle of the ascent to Calvary, washes his face with a linen cloth and, in exchange for this favor, Christ leaves his face imprinted on the fabric (

Kessler and Wolf 1998). Second, the sheet in which He was wrapped in an improvised way on the evening of Good Friday, when, upon his resurrection, tradition says that He left the image of his martyred body imprinted on it. The Christian tradition has recorded this countless times in the tradition of the Holy Shroud of Turin (

Nicolotti 2014). However, Hitchcock’s filmic iconography uses the same theme in a skillful visual analogy that appears to spring from his unconscious.

On the one hand, Norman picks up the corpse thoroughly as if it were a sacred body: he places the shower curtain on the floor, drags Marion’s corpse, wraps it carefully, and lifts it into the trunk of the car. In this movement, several frames are significant in the visual analogy with the burial of Jesus at the hands of Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea, in the presence of John, Mary, and the holy women. The burial of Jesus refers to the interment of his body after crucifixion, before the eve of the Sabbath, described in the New Testament. According to the canonical gospel narratives, He was placed in a tomb by a councilor of the Sanhedrin named Joseph of Arimathea; according to Acts 13:28–29, He was laid in a tomb by “the council as a whole” (

Ehrman 2014). In art, it is often called the Entombment of Christ (

Forsyth 1970). This is the classic iconography of the entombment (

Sadler 2015). Everything is the infinite white flat surface of a blank canvas: the pure geometrical abstract space. This will be turned into different

places: the image of the body of Christ (Turin), the icon of Christ’s face (Veronica), and the sudarium of Marion Crane at the hands of a scared Norman Bates.

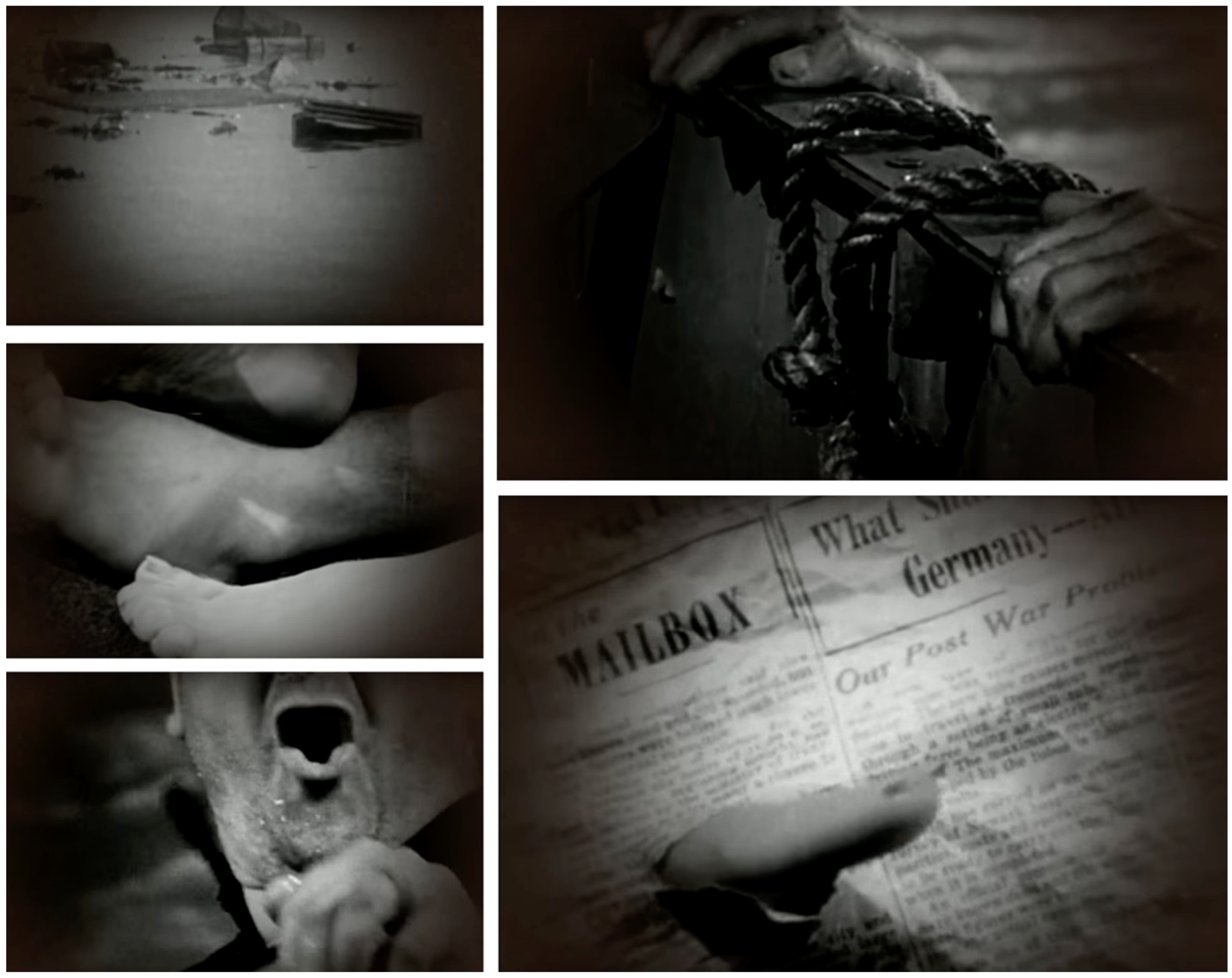

What is important here is the visual analogy between Hitchcock’s stills and the works of art that correspond to the tradition in which the same scene appears with all its drama and revealing intention. On the one hand, Norman picks up Marion’s corpse (

Figure 1a); on the other, in the miniature of The Taymouth Hours (

Figure 1b), where the apostles Peter and John find the empty Christ’s tomb because the Lord has raised. The artist of this painting knows the importance of the shroud as proof of the resurrection. From now on, this shroud will have the halo of the Master disappeared and re-appeared in the scenes of his apparitions to Mother Mary, the apostles, the holy women, and other saints.

From the relationship between sacred space and art, it is worth commenting on the visual analogy between Hitchcock’s image and others, such as The Taymouth Hours, both documents for the aesthetics of suspense in the context of the sacred. The point common to both is the presence of a corpse wrapped in white cloth, a custom from the ancient burial ritual in the Jewish religion. In line with Jewish law, the body is washed (Tahara) but not embalmed before being dressed in a plain burial shroud. This is overseen by a group of Jewish men and women, known as the Chevra Kadisha, who remain with the body until burial to ensure it is protected and prepared according to Jewish funeral traditions. During this time, the men often wear a prayer shawl (“tallit”) (

Evans 2005).

Iconographically, in the preparation of Marion’s cadaver, Hitchcock uses the visual language of corpse preparation from the Judeo-Christian tradition (

Bodel 2008): an opaque plastic curtain that, on the black and white tape, appears as a simple white sheet. Marion’s body is wrapped in silence while Bernard Herrmann’s score plays in the background, with only stringed instruments, giving it the air of a clandestine funeral (

Brown 2023, p. 26). Norman treats the body with care, almost with studied affection. In his mind, the murderer has been his mother, and he must cover up the crime by making the corpse and the blood disappear. The shower curtain serves here as a funeral shroud, and the car, also white, as a coffin for the burial. The white sheet without a body in the medieval miniature symbolizes life; in

Psycho, it signifies death. But in both cases, it is a wrapping that enhances what it has already enveloped: the body of the crime.

The work of Christo and Jeanne-Claude shows, since the 1960s, the symbolic power of wrapping objects, buildings, or landscapes. The wrapping of a phone draws attention to the object’s formal qualities, especially its spatial dimensions (

Figure 2a). But attention is also drawn to no longer visible qualities; we meditate about what is wrapped that we cannot see. Also, this wrapping involves negating the object’s function, displacing it, or diminishing it while it is being wrapped. However, by doing so, the object’s function is conceptually highlighted by being visually interfered with. The artistic treatment (or use) of the corpse (in our case) for wrapping contrasts with the usual functional use of it (or, in the case of a cadaver, with one’s normal relationship to it) (

Crawford 1983, p. 58). It will also happen similar to the wrapped chest that supposedly contains the body of the murdered Mrs Thornwald in

Rear Window (

Figure 2b).

Moreover, the iconography of Veronica is also present in Hitchcock’s work. Apparently, on the way to Calvary, a woman named Veronica came out and washed his face with a towel. In return, Jesus miraculously left the actual image of his face imprinted on her. One of the frames of Norman’s murder reflects something similar. When he prepares the shroud (shower curtain) for Marion’s corpse, he gives the impression of being that woman, called Veronica by tradition. This is a legendary figure who was said to have lived in Jerusalem at the time of Jesus, and He imprinted his face on her kerchief. In written texts, her first appearance is in the 4th-century Gospel of Nicodemus (Acts of Pilate) (

Izydorczyk 1997), where she testifies before Pilate that she was the woman whom Jesus cured of a persistent flow of blood (Matthew 9:20–22, Mark 5:25–29, and Luke 8:43–44). The first text associating her with the imprinted cloth was

The Avenging of the Savior (possibly of the 7th or 8th century), where she explains to an envoy from Rome that during his ministry, Jesus had put his face onto a cloth for her. The envoy takes Veronica and the cloth to Rome, where it cures Emperor Tiberius of leprosy (

Gounelle and Urlacher-Becht 2017). It is surprising to find, in the scene of Marion’s murder, the image of Norman Bates in a visual analogy with Veronica (

Figure 3b). In her original iconography, this woman appears with a white canvas unfolded in her hands, showing the image of Christ’s face, which gives the character a name: Veronica or “true image”. This is shown in the miniatures of The Hours of Yolande of Flanders (

Figure 3a) and the Huth Manuscript, where Veronica appears with Vespasian, revealing the sacred veil to Joseph of Arimathea, who is released from prison (

Figure 3c). In wrapping the corpse, Norman gestures like Veronica’s, showing the white canvas without an image. It is not the actual image, but the image of the true death that has no face, as also happens in

Rear Window with the sheet being prepared by Stella (Thelma Ritter) (

Figure 3d) as a prefiguration of the murder of Thorwald.

Psycho is a strongly iconographic film. The basis of the analogical imagination has two complementary parts. On the one hand, the analogy provides an ontological basis for comparing the problem terms: the literalness of the film stills and, on the other hand, the Christian term to which it refers. In this case, the recollection and burial of Marion’s corpse with respect to the Holy Burial of Jesus and the comparison between the Veronica holding the canvas printed with the face of the master and Norman Bates holding part of the shower curtain in the manner of the iconic washcloth. The ontological basis of this analogy is to consider the death of Jesus Christ as a perfect crime. Therefore, the complement of imagination is added to the analogy: to consider the visual aspects of the murder of Marion Crane in its dimension of Christological analogy.

3. Rope and the Ritual of Sacrifice

Another critical theme in Hitchcock’s work that will unite sacred space with art is the idea of sacrifice in

Rope (1948). The whole thing is posed as a brilliant idea of Brandon (John Dall) and Phillip (Farley Granger), who, feeling intellectually superior under the Nietzschean concept of Superman, are going to commit a perfect crime in the person of David (Dick Hogan), under the omnipotent gaze of their high school teacher Rupert Cadell (James Stewart) (

Stellino 2017, p. 470).

For his first color film, Hitchcock chose the play Patrick Hamilton wrote in 1929 as the basis of his screenplay (

Hamilton 2019). From the formal point of view, it is a comedy with a dramatic structure in three acts that adheres to the classical theatrical sense. Its action is continuous, punctuated only by the curtain’s fall at the end of each act. This is an extravagant starting point, at least from a cinematographic perspective. In classical theater, the dramatic or Aristotelian units, not explicit but deduced from the

Poetics in 1570 by the Italian critic Lodovico Castelvetro, refer to action, time, and place (

Castelvetro 1984).

Hamilton’s play is staged on the second floor of a house in Mayfair, London. This story, based on the 1924 Leopold and Loeb murder case (

Fass 1993), concerns two college students, Wyndham Brandon and Charles Granillo, who have murdered fellow student Ronald Kentley as an expression of their supposed intellectual superiority. At the beginning of the play, they hide Kentley’s body in a chest and then throw a party for his friends and family, at which the chest containing the corpse is used to serve a buffet dinner (

Higdon 1999, pp. 34–38;

McKernan 1924, p. 2;

Chicago Daily Tribune 1924, p. 2).

Murderers feel intellectually superior because they make a crime as if it could constitute a work of art with artisticity (aesthetic sense), artificiality (productive sense), authenticity (it is truthful, it is produced), and communicability (it comes to light). We do not know if they had read

On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts by Thomas de Quincey, who had written in 1827: “We begin to realize that the composition of a good murder requires something more than a couple of idiots who kill or die, a knife, a bag, and a dark alley. Design, gentlemen, group arrangement, light and shade, poetry, sentiment are now considered indispensable in attempts of this nature”. (

De Quincey 2012).

Brandon’s apartment functions as a coffin; in it are condensed the horrors of humanity: there is a temple (the lounge), a priest (Brandon himself), and a victim (David). In reality, a savior is required whose role is engendered by Professor Rupert: a man, a messenger of God, who bursts from outside into history. Without forcing any parallels, it is quite possible to “compare” the fundamental plot of

Rope (the story of a hero who destroys evil) with an eventual story of salvation that follows the whole narrative scheme of the best of American Westerns: the hero who arrives confronts evil and disappears (

Devlin 2010, pp. 222–23).

This liturgy of space sets the scene theatrically as Brandon prepares the food to be served on the chest where David’s corpse rests. All those present participate in this banquet, creating a community (an agreement) of new values. The champagne drinking, Phillip playing the piano, and the books tied with the same rope of the crime are only scenic resources that seek to fill the scene with symbolic meaning. The house where Brandon and Philip commit the murder has everything necessary to be a cathedral: an altar of worship (the chest with David’s corpse, which is already a relic), a sanctuary (the area next to the altar where the ministers wander and protect it), a nave with stained glass windows (the continuous bench where the attendees sit and, in the background, the large glass window overlooking the Manhattan diorama), a priest (Brandon and Philip, who represent the sacrament of death) and a victim (David who lies inert).

Brandon uses the chest containing the body as a buffet table for the food just before their housekeeper, Mrs. Wilson (Edith Evanson), arrives to help with the party. Mrs. Wilson complains to Rupert, puzzled, that the boys have moved the dinner buffet around (

Figure 4a). But the act gets underway without further change. The epicenter of the film’s emotional energy has shifted to the chest where David lies. Above, the elements typically necessary for the celebration of a Eucharist are the altar, the tablecloths, the candlesticks, and the matter of the sacrament (the food, symbolically bread, and wine) (

Figure 4b). The parallel with the miniature of The Taymouth Hours is clear. Hitchcock, once again, establishes a visual analogy between the space of the crime and the area of the sacred rite as depicted in a 14th-century Book of Hours (

Figure 4c). Incidentally, he uses one of the strongest mise-en-scènes in history: the sacrifice of the Christian altar as the setting for the crime. However, they are not as far apart as they seem. In the Christian faith, the holy mass (like the Last Supper) is the bloodless realization of the sacrifice of the cross without bloodshed. Nor is there blood in Brandon and Philip’s crime. The beauty of the liturgy, of the rite, meets the beauty of the crime, which is considered a work of art (

Burwick 2001).

In this case, the sacramental dimension of the Eucharist lends a strengthening of the analogical imagination insofar as every Eucharist, every sacrifice, signifies a metamorphosis. The matter, the bread and wine, victim for the sacrifice, through the burning fire or the words of consecration, cease to be what they were to become something new. In this sense, in Rope, the symbolism oscillates between the visual imagination and the dialectical imagination that pushes to consider the murder of David as if it were a blasphemous Eucharist.

4. The Box as an Essential Sacred Space

From the point of view of the suspense space, the box is one of its privileged objects. Also, Christianity has traditionally used the box concerning mystery and surprise. The space of the church is a box facing east, through which the Christ-light dawns (

Figure 5c); the triptych is usually a seemingly harmless box that, when opened, shows the surprise and wonder of liturgical art (

Figure 5a); the reliquary as a liturgical object is a box containing organic materials from the body of the saints; the tabernacle is a box that holds the sacramental species (

Figure 5c); the coffin is a closed geometric space where the deceased are bid farewell to the afterlife.

Hitchcock knows the magical potential of the suspense of the box, understood as a privileged place to hide evil and, in fact, an essential part of the narrative of the perfect crime. The car’s trunk where Marion’s corpse is deposited is a box (

Figure 5d); the crate containing the pieces of Mrs. Thorwall’s corpse is a box (

Figure 2b); and the chest where David lies is also a box (

Figure 6b). A box captures everything: the slide viewer of L. B. Jefferies (James Stewart) and his way of discovering the difference in the level of the garden. Jeff finds that Thorwald has buried something under the flowers in the garden. He compares, with that little box, a photograph of the same spot, taken the previous week, with the new height of the flowers. A little box helps him to discover the crime. Maybe Thorwald’s wife’s corpse is lying there, or better, his instruments for dismembering her corpse.

But the medieval tradition provides, based on the Gospel, that around the sepulcher of Christ, there is a group of people who have introduced him, mourn for him, and send him away: Nicodemus, Joseph of Arimathea, St. John, Mary, and the holy women. Before the Italian Renaissance, the pictorial tradition used this group of people to generate atmospheric space around the corpse of Jesus.

5 This is demonstrated by many images such as the King’s MS 5 (

Figure 6d), The Taymouth Hours (

Figure 6c), the Yates Thompson MS 13 (

Figure 6a), or the Metropolitan of New York’s sculpture of the burial of Christ (

Figure 6e), compared to David Kintley’s “burial” in Rope (

Figure 6b).

Hitchcock easily achieves this same Christological flavor in the group he forms around the melodramatic corpse in

The Trouble with Harry and in the scene where David is Buried in the chest by Brandon and Philip (

Figure 7b). In this respect, he has two ways of organizing the scene’s content. The first is to arrange the four main characters around Harry’s body, disposing of his burial and disinterment. Here, Captain Wiles, Miss Gravely, Jennifer, and Sam Marlowe (

Figure 7a) are protagonists and seem to correspond to Joseph of Arimathea, Mary Magdalene, Mary Mother of Jesus, and the young John the Apostle. Very pedagogical medieval scenes in this regard are, for example, the Entombment of Jesus of the British Library Kings MS 5 (

Figure 7c), another entombment of the Yates Thompson MS 13 (

Figure 6d), and the sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (

Figure 6e). A group of figures creates all the space in a circular “human wall” that marks the compositional center in a suspensive vacuum that allows the visual analogy between the space of suspense in religious paintings and the sacralized space in Hitckcock’s suspense films.

Another spatial effect is seen in the bodily proximity between protagonists in the scene. It is easy to observe in medieval Christian art that, during the descent from the cross, one of the characters climbing up the ladder to hold it, either Joseph of Arimathea or Nicodemus, approaches intimately to the top of the body to secure it, in the Huth Manuscript (

Figure 8a) and the Taymouth Hours (

Figure 8c). The same occurs when Norman Bates grabs Marion to wrap her in the shower curtain. This physical proximity seeks the extracorporeal, sculptural space to achieve the necessary suspense in which the silhouettes are superimposed. The ritual tension grows at times (

Figure 8b). In contrast, in medieval paintings, Nicodemus’ face is flattened against Jesus’ body because the miniaturist treats the superimposed figures like a unique two-dimensional diorama (

Figure 8a,c).

In the West, from the discovery of Brunelleschi’s perspective, the box is self-constituted as the space of visual representation par excellence. Giotto had intuitively sensed this need to emulate the third pictorial dimension from the two-dimensional plane, suggesting the depth of space through the so-called doll’s boxes. This is why Brunelleschi is important: because he transforms an intuition into a true scientific apparatus. With this, the Florentine architect establishes a new visual analogy between the human eye as a pinhole perforated sphere and the mathematical perspective in painting as a perfect analogy between the second and the third dimension. From this point of view, photography and cinema are essential to penetrate the sense of analogical imagination. Finally, everything will happen in a box that, in reality, is a visual pyramid doubly truncated in the first and in the last plane, where the corporeal is suspended. Therefore, in Christian art and Hitchcock’s cinema, there is a common language: considering every box as a sacred space.

5. Rear Window, Lifeboat, and the Image of Fragmentation

We have already seen that the Shroud that wraps the corpse of Jesus and the curtain in which Marion is bound in Psycho have something in common that links them. Specifically, they share the whiteness of the shroud and the act of wrapping a corpse and preparing it for burial. Thanks to a particular logic, they are measurable phenomena connected through a tiered Aristotelian predicament system. The same happened between Rope’s sacrificial murder on the chest and the Eucharistic unbloody renewal of Christ’s death on the altar. Likewise, between the mysterious box (sometimes camera obscura, trunk, photo camera, or slide viewer) that acts as a death-dealing device in reality and the sacred box of the shrine, the tabernacle, and the basilica temple shoe box.

There is yet another notion of analogy, which is less studied and complex to keep separate from proportionality. It is the typical strategy of the Neoplatonic and Gnostic Christian thinkers who submerged the analogy in an (apparent) mystical incoherence. It is a system of qualitative rather than quantitative or mathematical proportionality based on a participation theorem that uses the vocabulary of similarity and dissimilarity.

The participation or proportionality type of analogy is inherently visual. They require some insight to establish and adjust the most convenient mutual harmonies. Comparing the holy shroud to

Psycho’s shower curtain poses a particular challenge to one’s discernment. This is why the visual arts are beneficial in establishing analogy: they achieve sufficient explanatory power for the nature and function of the analogical procedure. However, similarity or dissimilarity involves both the visual and the mental, more based on a kind of Romantic disanalogy or irrepresentable contradiction that points to negative hermeneutics. In other words, an analogy is also explained in terms of a disproportional comparison between the two terms (

Stafford 2001, pp. 2–23 and 57–96).

The case of Mrs. Thorwald’s murder in

Rear Window is not only literary or visual. Perhaps therein lies its ambivalent position between romanticism and postmodernity. Although we do not see the crime, nor do we know what it consists of a priori, we are sure that it will be the murder and subsequent dismemberment of a human body. The mental bridge, more than the visual, is set up, and this is the type of Kantian suspension of judgment that imposes its philosophical rules (

Makkreel 1998).

The Judeo-Christian iconography is the opposite of this type of action on the corpse when it protects bodily integrity. The Old Testament, referring to the body of the Passover lamb, interpreted in the Christian tradition as the Messiah and personified in Jesus to be sacrificed (the lamb of God), says “It must be eaten inside the house; take none of the meat outside the house. Do not break any of the bones” (Exodus 12:46), “They must not leave any of it till morning or break any of its bones” (Num. 9:12), and “He protects all his bones, not one of them will be broken” (Psalm 34:20). The Gospel of John explains how they broke the legs of the other two crucified together with the Lord: “The soldiers therefore came and broke the legs of the first man who had been crucified with Jesus, and then those of the other. But when they came to Jesus and found that He was already dead, they did not break his legs”. (19:32–33) “These things happened so that the scripture would be fulfilled: “Not one of his bones will be broken”” (19:36).

In this context, the body fragmentation corresponds to the idols of Israel in the a posteriori context of Christianity. In a

Biblia pauperum of the British Library, we see how Moses destroys the consecrated image of the calf (

Figure 9a), the infant Christ causes the idols to fall (

Figure 9b), and the Ark of the Covenant cause Dagon to fall (

Figure 9c). Everything here is expressed in terms of the bodies’ fragmentation. The ontological principle of the unity of substance is lost after breaking someone or something (

Bolton 2004). To break it is synonymous with dying. Following this semi-platonic mood, and with his characteristic jocularity, Thomas de Quincey offered his body to medical science with the proviso that it not take immediate possession (

Youngquist 1999, p. 347).

Sparagmos (from σπαράσσω,

sparasso) means rending, tearing apart, or mangling in a Dionysian context (

Lincoln 1991, p. 186). In the Dionysian rite, as represented in myth and literature, sometimes a human is sacrificed by being dismembered (

Storm 1998, pp. 6, 9).

Sparagmos was often followed by omophagia (the eating of the raw flesh of the one dismembered). It is associated with the Bacchantes, followers of Dionysus, and the Dionysian Mysteries. In this way, when Thorwald dismembers the corpse of his wife, he is acting dramatically (

Figure 9d). A Dionysian flavor also has the fact that Raymond Chandler, who did not succeed with the adaptation of Hitchcock’s

Strangers on a Train (1951),

6 inspired the nickname “Black Dahlia” for the famous Elizabeth Short’s murder and mutilation in 1947 (

Figure 9e). The year before, he had written the screenplay of

The Blue Dahlia, the American film directed by George Marshall (

Phillips 2000).

In his article on Hitchcock’s

Lifeboat, the cinema critique Manny Farber formulated a theory of film space starting from a metaphor coined in a first review: “The lifeboat gives less the illusion of a lifeboat… than of an expansive, well-protected stage”. Presented by him as a destructive trend in Hitchcock’s work, this is nonetheless a brilliant description of

Lifeboat’s visual style: those magnificent frescoes that enable the master of suspense to sell “solid talk in rather close quarters” by creating “a certain realism on a theatrical level”. (

Krohn 2020, p. 92).

From the compositional point of view, the whole film poses a dislocation between the parts and the whole. Hitchcock makes some general and intermediate shots and, at the same time, inserts close-ups of his passengers’ body parts. In the beginning, the sea landscape scene shows the failure of an American merchant marine ship to fight against a German U-boat. A fragmented seascape is the result, and passing by are playing cards, a chessboard, boxes, flags, and other elements that, in isolation, no longer make narrative sense. During the film, as if dissecting a single human body, hands, feet, and faces, are captured by the camera as if the final fragmentation typical of the

sparagmos of a Greek tragedy had already occurred (

Figure 10).

Moreover, the idea that during the voyage, the passengers must amputate a leg of Gus Smith (William Bendix) already explains the collision between the whole and the parts that will continue to take place. The master of suspense swings, in this type of film iconography, between the tradition of Greek tragedy and the drama of the sacrifice of the image typical of Christianity. It is a struggle between iconoclasm (fragmentation) and iconodulia (sometimes idolatry, sometimes Christological incarnation) that he resolves in a combination of visual analogy (asceticism) and mental analogy (mysticism).

Hitchcock’s little theaters are populated by all kinds of characters, similar to carnival scenes, a public square where ancient rites were enacted on the steps of the town cathedral in medieval Europe. At the end of the carnival period, the king might be killed and ritually dismembered. Following Farber, this is what we see enacted on the “stage” of

Lifeboat, whose properties are designed to display just a dismemberment or

sparagmos. The inversion happens when Willie, a prisoner, becomes the captain of the lifeboat (the king), and the passengers become his prisoners. This can only be resolved with the last great composition of figures who conceal their deed from our sight, as it would have been hidden in Euripides (

Krohn 2020, pp. 92–93).

There are other interesting cases of dismembered bodies that raise more paradoxes in the relationship between the parts of the human body and the whole. The case of relics is a particular contradiction, apparently close to the objectification of sanctity in organic remains and its association with mass attraction (

Ortega Jiménez 2023). There are important relics, such as that of St. Teresa of Avila, which are preserved as a result of dismemberment due to popular fervor and her reputation for holiness. The body of Mother Teresa was dismembered: the right foot and a piece of the upper jaw are in Rome; the left hand in Lisbon; the right hand, the left eye, fingers and pieces of flesh scattered throughout Spain and Christendom; the right arm and heart, in reliquaries exposed in Alba de Tormes (

Auclair 2008), such as the Arm Reliquary of the Metropolitan Museum of New York (

Figure 11a). This dissemination of the remains of the Saint reminds of the myths linked to fertility rituals (

Vinatea Recoba 2016, p. 90). An analogous phenomenon derives from the Second World War, when, due to the dismemberment of human bodies by the effect of bombs, hundreds of prosthetic limbs were manufactured to cover that need (

Figure 11b,c). In the

sparagmos that derives from sanctity transformed into relics and in the horror of mechanized warfare, the myth of the dismemberment of Orpheus is resurrected.

When, at the end of this section, we wonder about the tragic background (in the Greek sense of the word) of Mrs. Thorwald’s murder in

Rear Window, a few conclusions can be drawn. First, Hitchcock is always aware of the dramatic sense of Greek tragedy: he is always aware that suspense is a consensual pain that combines a positive (Apollonian) and a negative (Dionysian) hermeneutics. Second, this Greco-Roman pathos overlaps with the Christian tradition to the extent that “the Christus Patiens… recycles lines from Euripides’

Bacchae, Medea and Hippolytus (and other sources) to retell, in three sections, the passion and crucifixion; the burial; and the resurrection of Christ”. “By virtue of specific parallels between the myth of Pentheus and the passion narrative, it echoes

Bacchae… not only textually but also, in fact, conceptually; Christ is associated with both Pentheus and Dionysus”. “By a process of bi-directional influence, Bacchae was Christianized and Christianity, in its way, mystified”. (

Perris and Mac Góráin 2020, pp. 64–65). Third, the metaphorical

sparagmos, virtually present in

Lifeboat and

Rear Window, is a commonplace of Western culture that allows the case of a new mental and visual analogy between Hitchcock’s filmography, Christian tradition, and Contemporary world history.

The spatial equivalent of dismemberment is always partitioning. The difference is that the dismembered parts of a body acquire an extracorporeal space that they did not have before, whereas, before being partitioned, space is air. The suspense of Rear Window and Lifeboat consists in creating a spatial composition using a specific visual construction: in Rear Window, this “air that becomes visible” is explained in the compartments of the house in front of it as if they were a doll’s house. In Lifeboat, the dismemberment is created through a confined space that is partitioned by the disagreement between the minds of the crew members. Dismembering, in short, leads to a new visual analogy between the extra-corporeal and the inner-corporeal space.

6. Psycho Again: The Bathroom as a Holy Sepulcher

The Bates Motel room number one bathtub can be retroactively interpreted as Christianized. Mrs. Bates has killed Marion Crane, and Norman has to clean the blood from the bathroom. The camera points to the bathtub where Marion took her sinister shower. The mixed water blood is slowly removed from the walls, floor, and bath. Bernard Herrmann’s chord music accompanies the ominous scene. In the meantime, the visual analogy between past historical coffins like the Roman marble sarcophagus with the Triumph of Dionysos (

Figure 12a), the Mausoleum of King Peter III the Great with a re-used Roman bathtub (

Figure 12d), the bathtub of the room number one at the Bates Motel (

Figure 12b), and the bathtub drain that fuse with the inert eye of Marion (

Figure 12c) create novel concomitance.

The funerary monument of King Peter III the Great uses a Roman bathtub to echo an imperial pretension and to create a rhetorical amplification of the king’s ancestral roots. The tomb of Gallienus with Dionysus with the four seasons and the bathtub of Bates have a point in common: the hole of the water drainage and the horrific idea of the corporal liquids of the corpse. There is a strange association between death in Rome as the end point of life and Christian death as the beginning of an authentic life full of transcendent meaning. But they all go through the same thing: a bathtub-shaped receptacle from which they will never emerge. In both cases, the breath of life slips through the hole of a sarcophagus or a bathtub. This is the visual analogy Hitchcock uses for Psycho: a sarcophagus-bathtub that, for some, is the beginning of life and, for others, is the end of power. Both have the same spatial dimensions; both are made, as we will see, for the same purpose. A new spatial analogy will unexpectedly emerge.

There are two literary classical reasons for the bathtub murder. First, Aeschylus, remembering the well-known Homeric custom according to which the women of the household bathed the newly arrived hero, may have seen an excellent opportunity to catch Agamemnon unarmed and facilitate his murder by a woman.

7 Secondly, Aeschylus may have remembered a theme from Greek mythology, one such as we see in two examples. First, Medea procured the death of King Pelias of Iolcus by inducing the king’s daughters to boil their father in a cauldron or bath, together with certain poisonous herbs that were intended to renew his youth. Second, the daughters of King Cocalus of Sicania drowned in the bath of Minos of Crete, who had come to Camicus in pursuit of the fugitive Daedalus.

8In these stories of the death of a king in a vessel of water and at the hands of women, there is a definite ritual (

Duke 1954, p. 326). Sacrifice among the Canaanites was associated with the ritual killing of the king, in which he and the deity were identified. There was a later substitution of a human or animal victim for the king. In Christ, the efficacy of the substitute victim was recognized with the dying–rising god in delivering the community from the influences of the demon world. Such priestly theology bases the concept of sacrifice on the Christian tradition, which accompanies (with the Church) the covenant relation between God and man. The rite of circumcision in the Old Testament looks forward to the Christian rite of baptism and the incorporation of the believer in Christ; sacrifice in the Old Testament reaches out towards that perfect understanding of sacrifice and atonement in the Person of Christ (

Beecher 1964, p. 124).

We may not expect the water of the Paleo-Christian baptisteries to be a symbol of death. “Scholars speculate that the octagonal form of baptistery derived from the classic Roman mausoleum, suggesting an association of baptism with death and Christian martyrdom”. (

Rutherford 2019). Mausolea also shared significant functional and architectural similarities with early Christian baptisteries. The centrality of death and resurrection in the theology of baptism (cf. Rom 6.4) may have made a mausoleum a natural design prototype for a baptistery. Furthermore, the building centralized saints’ tomb shrines (martyria) in the 5th century, and the association of baptism with martyrdom further reinforced these parallels (

Jensen 2011, p. 238). Although André Grabar’s research generally focused on the development of the martyrium, he drew parallels between those buildings and baptisteries (

Grabar 1946, pp. 446–47, for example). Krautheimer additionally identified the features that (some) baptisteries share with

mausolea that they do not share with other Roman monuments (

Krautheimer 1942).

Does Marion Crane participate in a kind of Christian roots ritual of death in the bathtub of the number one room of the Motel Bates? Has Norman a sort of priesthood awareness of producing a sacrificial death when he kills his victim on (a paranoic) behalf of his mother, Mrs. Bates? Has Alfred Hitchcock an explicit will of Christianizing the origins of Roman funerary architecture with a deliberate symbolic parallelism between the bathtub murder and the eschatological sense of the Christian baptism in pointing to the tragedy of Christ’s passion? How far is the visual analogy going in this case?

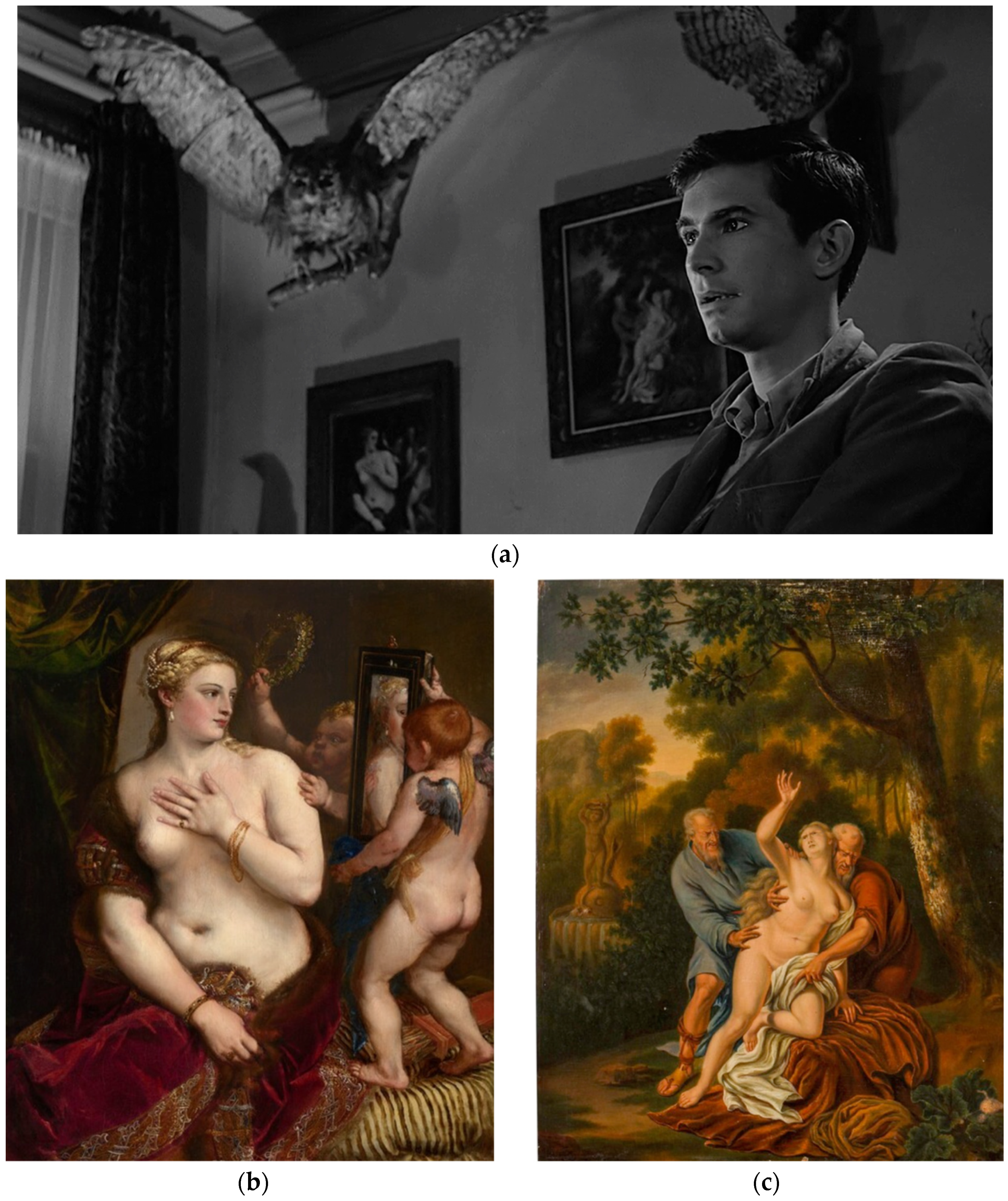

After Marion arrives at the Bates Motel, Norman brings her sandwiches and milk and invites her into the parlor behind the motel’s office. The paintings in the parlor do not capture her or the camera’s prolonged attention. Still, they remain in the background in this scene and others (

Figure 13a). The picture behind Norman, next to Marion, is a copy of Titian’s Venus with a Mirror, now in the National Gallery in Washington, DC, USA (

Figure 13b). After eating, Marion holds her left arm diagonally across her chest, as the woman in the painting is doing. Titian’s image of Venus is reflected again in the painting hanging on the wall next to it, which the film’s viewer can see. This can be identified as a 1731 canvas by Willem van Mieris (1662–1747) (

Figure 13c).

This painting is the story of Susanna and the Elders, from Chapter 13 of the Book of Daniel in the Bible,

9 and tells of a beautiful, married woman who was in the habit of walking in her garden as two community elders would watch her in secret. One hot day, she decided to take a bath and sent her maids inside to get oil and ointment. Seeing that she was alone, the two elders came out of their hiding places and threatened to blackmail her if she did not give in to their sexual demands. Susanna cried out for help, and her servants came running, only to hear the elders claim that they had caught her committing adultery with a young man who had escaped. Susanna was convicted of this crime and sentenced to death by stoning, but young Daniel stood up at her trial and proved that the elders were lying. Her death sentence was then transferred to them.

The paintings in the parlor scene in

Psycho reconnect Venus and Susanna, positioning Marion Crane as the third vertex in a triangle. Like Venus, Marion holds her arm diagonally across her chest; like Susanna, Marion is spied on and attacked as she washes herself. Although other meanings have been suggested (

Bach 1997;

Durgnat 2002;

Gunning 2007;

Hurley 1993;

Lunde and Noverr 1993;

Toles 2004). Hitchcock’s most direct intention is to draw a parallel between the voyeurism of the elderly and that of Norman. However, from the point of view of the visual analogy we have been pursuing, it is easy to maintain the idea of the water bath as a tomb where one is buried and from which, by baptism, one is resurrected. As Catherine Brown Tkacz has amply shown, Susanna is, within the Christian context, nothing less than a prefiguration of Christ.

10This typology is discussed and depicted as early as the 4th century and as late as the 17th century. The parallelism is seen in sermons, letters, and commentaries by influential theologians such as Ambrose, Jerome, and Augustin, Latin and vernacular commentaries, 5th- and 14th-century autobiographies, medieval religious plays, and 17th-century narrative poems. But also in sculpture, ivory, gold glass, incised glass, fresco, stained glass, embroidery, and manuscripts. The Sarcophagus of the Chaste Susanna at Aries, the marble of the Two Brothers sarcophagus at the Vatican, and a related fragment of a sarcophagus lid at Cahors are very explicit about the fact of death. Marion Crane’s car is in Psycho, her sarcophagus is the bathtub, and the risk of the pre-Christological death of Susanna is in the Bible.

Again, it is easy to see everything in space. Norman spies on Marion through the shutter of a makeshift camera obscura; Susanna’s corrupt old men look at her concerning an enclosure and a bathtub; the medieval sepulchral space is associated with the imperial Roman bathtub, the drain of Marion’s bathtub is standard to that of any other tomb, and the Christian baptistery is a sacramental prefiguration of death. Everything is sustained through visual analogy and the difference between physical space and the place of existence.

7. Conclusions

It is indisputable that when Alfred Hitchcock was asked about his status as a Catholic and how this had influenced his films, he answered with an evasive answer. He was a rather reserved man about his personal life, but he did not shy away from questions of any kind. However, he preferred to talk about cinema rather than reveal his private life. From his answers, it could be deduced that he was culturally Catholic and rather lax in his practice. Answering “Catholic Hitchcock” about his cinema is a wrong reply to this problem because it answers a lousy question: are you a Catholic film director?

With that kind of (wrong) question, the interviewer wants to know something significant to understand better the filmography of the master of suspense: What are the motivations of your cinema, given that you are a Catholic? What constraints have you encountered in making your films about a doctrine that is not ambiguous? How have you faced, with those conditioning factors, the problems you talk about in your movies, such as love, death, envy, hatred, human sexuality, paternity, guilt, the conscience of sin, the role of women in the world, the sense of humor, and so many other crucial problems to explain reality from the big screen? Sometimes, it is possible to ask the wrong question and accidentally get some answers to other good questions that have yet to be answered. That’s the cinema.

For these reasons, which are, in fact, epistemological, the visual analogy has resorted to explaining spatially the problem of the relationship between Hitchcock’s cinema and Christian culture. In this way, the initial lousy question of these conclusions has broadened its horizon. An attempt has been made to show whether there was any relationship between Christian iconography, especially coined and developed throughout the Western Middle Ages, and some of his most significant films. The examples naturally led us to a mysteriously Christological selection. The result, in filmographic terms, has allowed us to make an anachronistic analysis, that is, focused on problems rather than the chronology of the films. Thus, we have been able to think kaleidoscopically concerning concepts projected forward or backward in time about the movie emerging in our analysis’s imagination.

The theme of the Holy Shroud about the death of Marion Crane in Psycho and the management of the corpse by Norman Bates in the manner of a holy burial allowed us to reflect on the sacred (and Christological) dimension of carefully wrapping a corpse in a white cloth and placing it in a car trunk-coffin. The visual efficacy of this analogy has been explained, partly thanks to black and white. The case of Veronica is especially photo-cinematic from the moment Christ “imprints” his face on a towel, as celluloid is impressed with light and shadow. The centralism of the corpse in The Trouble with Harry has helped to understand the problem of the extracorporeal space generated by any corpse that must be buried and its spatial dimensions.

The banquet in Rope’s sacrificial and Eucharistic angle is a beautiful visual analogy because of its sacramental dimension. All the sacrificial elements of ancient cultures are reflected in a sinister way: the altar, the temple, the victim, and the priests. The aspect of communion at the banquet in the murderers’ house gives this iconography of ancient pre-Christian origins a mainly Catholic air.

Both Psycho and Rope’s visual analogies already announced the theme: the box as an essentially sacred space. A triple analogy helped to advance the investigation: the trunk of Marion’s car, the chest of David’s house, and the crate where Thorwald transported his wife’s dismembered corpse were the essential spaces of death reminiscent of Christian iconography. However, in the Rear Window, the camera, the slide viewer, and the film’s architecture of the built studio backyard were added.

Again, the analogy between the dismemberment of Mrs. Thorwald, the sparagmos of Greek tragedy (which also appears in Lifeboat), and the bodily fragmentation typical of Christian relic discourse was a surprise and a paradox. The Christian culture of bodily integrity after death, the Judeo-Christian destruction of idols (because they are images of false gods), and the cult of relics, fragments of saints’ corpses, represent a kind of unthinkable iconographic clash. Finally, the bathtub as the existential site of death in Psycho and the painting of Susanna and the elders at Norman’s parlor helped to extend the parallel between Hitchcock’s cinema and Christian culture.

Indeed, these visual analogies are executed in space, either to self-contain it in the confinement of the tomb, the bathtub, or the trunk or to explode it outward, as in the case of the ritual dismemberment of the human body. In his filming, everything happens spatially because Hitchcock is like an architect god, like a divine eye that organizes the chaos of the abyss. However, the visual analogies occur in the places of suspense, in the mental geography of existentialism, which does not distinguish the literal Christian experience from the fimic analogy. This place of existence is meant to be resolved in the tension between the imagination and the dialectic of analogy, where the Catholic impulse that leads to optimism coexists with the Protestant one that, from individualism, despairs and becomes sinister. That place for suspense is understood as a hanging emotion that arrived in the 20th century, having drawn a long bridge with the world of medieval ambiguity.

The idea of visual analogy might suggest a mere visual resemblance, in this case, between specific frames of Hitchcock’s cinema and scenes from Christian iconography. However, in these comparisons, a solid ontology of suspense emerged to demonstrate that what is important is not whether Hitchcock is a Catholic film director but whether the clash between the analogical imagination (the beautiful) and the dialectical imagination (the sublime), Christian culture and Hitchcock’s cinema can help to define the suspenseful essence of our Western culture.